Greenberg Keynote Speech at Boston Convo. "New Challenges for Civil Rights Lawyers"

Press Release

May 12, 1965

Cite this item

-

Press Releases, Volume 2. Greenberg Keynote Speech at Boston Convo. "New Challenges for Civil Rights Lawyers", 1965. d54da3ec-b592-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/bd1a7709-8ca3-4d97-9417-75c4a8ebc42d/greenberg-keynote-speech-at-boston-convo-new-challenges-for-civil-rights-lawyers. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

sty

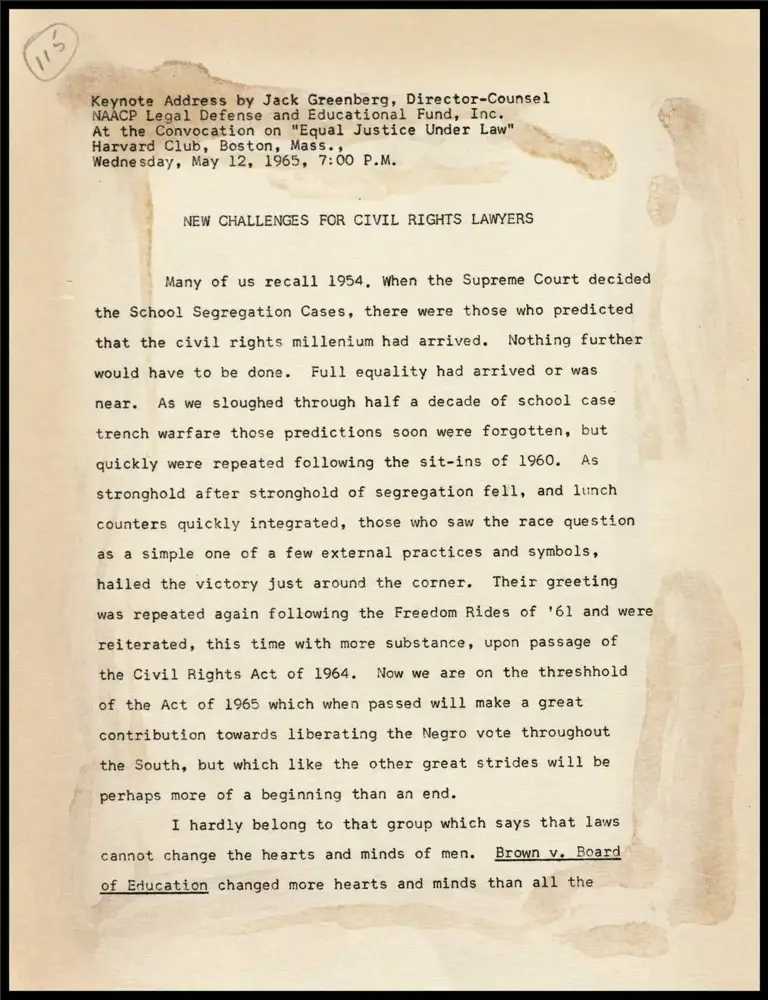

Keynote Address by Jack Greenberg, Director-Counsel

NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.

At the Convocation on “Equal Justice Under Law"

Harvard Club, Boston, Mass.,

Wednesday, May 12, 1965, 7:00 P.M. % oe *

NEW CHALLENGES FOR CIVIL RIGHTS LAWYERS

Many of us recall 1954, When the Supreme Court decided

the School Segregation Cases, there were those who predicted

that the civil rights millenium had arrived. Nothing further

would have to be done. Full equality had arrived or was

near. As we sloughed through half a decade of school case

trench warfare those predictions soon were forgotten, but

quickly were repeated following the sit-ins of 1960. As

stronghold after stronghold of segregation fell, and lunch

counters quickly integrated, those who saw the race question

as a simple one of a few external practices and symbols,

hailed the victory just around the corner. Their greeting

was repeated again following the Freedom Rides of '61 and were

reiterated, this time with more substance, upon passage of

the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Now we are on the threshhold

of the Act of 1965 which when passed will make a great

contribution towards liberating the Negro vote throughout

the South, but which like the other great strides will be

perhaps more of a beginning than an end.

I hardly belong to that group which says that laws

cannot change the hearts and minds of men. Brown v. Board

of Education changed more hearts and minds than all the

=o = Ge)

sermons preached between 1954 and 1964. Indeed, it changed

a good many sermons. Nor, as one who has for the past five

years defended thousands of demonstrators do I deprecate the

power of protest, which has worked such enormous progress.

What I am trying to say, and what perhaps does not

need saying to a group like this, is that to progress

effectively we should look ahead at what needs to be done and

prepare to do it, not congratulate ourselves on what has been

accomplished. And it is that job of appraising the civil

rights future to which I plan to address myself tonight.

The kinds of problems are no mystery. They all have

been encountered in one place or another in the past. There

is a fairly natural progression in which hard core areas like

Mississippi, Alabama, Northern Louisiana, and Southwest

Georgia, are giving up inflexible segregation barriers and

becoming like tokenist North Carolina, or like major urban

centers in Georgia, Virginia and Tennessee. They have

retreated under the pressure of litigation, protest, and

vast social forces. As the tokenist areas come more into

the economic, social, and educational mainstream of America,

they are taking on qualities of northern urban centers, which

is not to say that they will have shed their race problems.

Rather, they will become deeply involved in issues of

employment, housing, educational quality, all parts of that

complex which today is called "poverty" which both is and is

not part of "civil rights." They will begin passing their

al

~~ own antidiscrimination laws and the fight will be to enlorce

them and to extricate victims of urban blight from the decay

hae has afflicted much of our cities.

This means, for example, in the South, deep and middle,

that there will be more cases like the Greenville, South

Carolina park case concluded not long ago. There, after a

prolonged litigation in which park authorities postponed but

did not prevent integration they faced the ultimate issue,

what to do about the swimming pool. As you may know,

integration in swimming is resisted most vigorously, for it

is supposed to have certain sexual connotations. They had

no way of preventing the integration so they did the next

best thing. They barred people from the pool, and instead,

imported five sea lions from California and gave them the

pool as their home. The case then became messy. Two of the

sea lions died, The play equipment, sliding boards and so

forth, placed in the pool for the seals' pleasure, cracked

the bottom, causing hundreds of thousands of gallons of

water to be lost. The three surviving seals were huddled

into showers during expensive, laborious repairs. Then they

were returned to the pool to be observed by children. I

have received numerous inquiries and can report that all

the seals are black. Children, however, are permitted to

view them without regard to race.

That is a funny story, and it is true. But the point

is that there are going to be many seals in pools and schools

é oe A Seat at od

pe be ae fig nr em

and other insti tétions of America before this thing is over.

einer “ates, there will be resistance, and foot dragging,

and dilatory procedures, which will be overcome only by

action.

And this type of evasion is hardly confined to the

deep South. In fact, it is characteristic of a change from

the hard line defense of a Governor Wallace and Governor

Barnett to the way segregation and discrimination are main-

tained in New York and Massachusetts.

Farther North we will have such legal battles as that

on Proposition Fourteen in California and its counterparts

that are springing up across the country. In the name of

private property efforts are being made to strike fair housing

laws from the books, and courts, legislatures and public are

engaged. And the race question provokes debate over wee

urban renewal should be continued and what its role shoul™

be.

As a legal organization and as lawyers, we, of course,

have been putting our minds to what we can do as our

contribution to the problems that remain. The area of our

operation is limited to the courtroom and similar forums

though what happens there often causes chain reaction. Today,

while we must keep on doing many of the same old things,

we don't want to keep on merely responding, we would like

to where we can, take initiatives.

Pet

t

i 7 A good place to begin is withthe civil@erane: nceqe

1968,) Some of its enforcement problems are obvious. The

public accommodations section has been widely obeyed in

urban centers. Litigation of a fairly simple nature, usually,

is required on a moderately large scale in small towns and

rural areas and to some extent in poorer sections of large

cities. Some borderline cases in which coverage may be

“debated as with some bowling alleys or swimming pools will

_ bring on a few complicated cases. Evasion in the form of

fake private clubs and two sets of menus by which whites may

be charged $0.45 for scrambled eggs while Negroes are charged

$5.00, will take some effort. We already have such cases.

But enforcing the public accommodations section will be far

from our major problem.

On the other hand, Title VI of the Act, popularly

known as the federal fund cutoff section, already promises

major problems. It was enacted, of course, out of moral

outrage against paying federal funds to schools, hospitals,

and other programs which maintain racial discrimination. Its

great efficacy was supposed to be that it would furnish a

a | administrative way to integrate where expensive,

time consuming litigation would take infinitely longer. But

almost a year's experience with Title VI, despite a great

barrage of press releases from the Department of Health,

Education and Welfare, has not been promising.

Sa

Take hospitals, for example. Hospitals that received

funds under the federal Hill-Burton hospital construction

act are forbidden to segregate by the United States Constitu-

tion. When Title VI was enacted hospital administrators who

were segregating were already in violation of the United

States Constitution, but were defying it. We have sent more

than seventy-five complaints of discrimination in federally 5

aided health care facilities to HEW. So far as we know, only

one has ever been investigated. The investigators filed a

report stating that there was segregation in the hospital,

but that the administrator promised he would end the practice

by this coming summer, HEW sent us a copy of that report

with a cheerful letter stating that the matter had been closed

ina satisfactory manner. And so far as we know, that is the

only enfocement of Title VI that has occurred with respect

to hospitals. Hundreds of hospitals are violating the

Constitution and Title VI. But HEW has virtually no staff

to enforce. There appear to be no plans to engage staff of

adequate strength.

The situation with respect to schools and Title VI is

worse. Regulations now being promulgated, even if enforced,

will fall far short of the promise of what Title VI is

"

supposed to be. First, Title VI authorities will approve ee

so-called "freedom of choice" plans. That is, where

segregated systems have been maintained for a century, and

for a decade beyond Brown v. Board of Education, HEW will agree

vy

(-

Pyek

that the Const tutta ts Satigéiodit school officials tell

Negroes that they are now free to attend any school they

desire, and abolish their zone systems for assigning children

to schools. Ninety-eight percent of America's school systems,

or more, always have assigned according to zones. The reason

for the sudden switch to free choice is obvious, even to HEW.

Anyone with knowledge of how segregation has worked, can

predict that community pressure and the momentum of segregation

will keep things entirely or almost entirely as they have

been. Freedom of choice is an illusory freedom. Title VI

authorities would be within their power and can fulfill their

duty only by insisting that segregation can be disestablished

by a fair, traditional system of zones, drawn according to

normal school districting practices, whereby children are

assigned without regard to race.

: But, where zones will be maintained, HEW, ignoring the

clear mandate of Brown v. Board of Education that the burden

is on school authorities to justify delay, have allowed

systems to start by desegregating only four grades without

having to offer any reason for delay. In what are called

"exceptional" cases only two grades need be desegregated.

Imagine the school system which will not call itself

"exceptional":

Beyond this, where a school system is under a court

order, no matter how restrictive a view the judge may take

of a Negro child's constitutional rights, HEW will require

oe

Me

as)

—— cp reser

hs ore than the court requires if the order is final. And

HEW'\s “definition of final, while not yet clear, appears to be

erely that the order is appealable. But virtually every

order to do any desegregating at all is appealable. Taig

Means that districts in litigation which have been orderel

by a court to integrate only a single grade have bought

exemption from Title VI and will be in interminable litigation.

And it further means that if Title VI authorities go too

slowly, or evade requirements even of Title VI, school

districts will arque in court, as they have, that their

desegregation plans have been approved by the federal government.

But the most alarming feature of Title VI is that

there appears to be no staff at all to enforce it. Educators

are members of an esteemed profession, but they and their

boards have for a decade been violating their oaths to uphold

the Constitution of the United States.

In a northern Florida county we have a school segre-

gation case. As any one could see the schools were racially

separate, but the defendants insisted that we prove it. And

they were not going to make it easy for us. The Superintendent

was asked whether a particular school was Negro. "It is

preponderantly Negro," he replied. "Do you mean," he was

asked, "that there are white children in the school?" "No,"

he answered, "they are all Negro, but most of the Negroes

are preponderantly Negro."

v ge lee

= oe

Why should this man’take an assurance’to the Departmen

of HEW more seriously than he takes the Constitution? Thi

are thousands like him. Assurances will be meaningful o

if policed. Otherwise Title VI will be worse than unenforeed.

It will be a delusion. HEW will issue annual releases +d

the nation that so many thousands of districts have signed”

assurances and now are integrated. And nothing in fact

will be happening. ‘

The lesson of recent years ought not be lost. Us the

law is ineffective protest will take to the streets. Fine

government should take advantage of the powers it now has

rather than be forced to it in crisis. Some day, Martin

Luther King, Roy Wilkins or James Farmer will march down the

streets demanding change, and incredulous souls will ask

why they did not turn to the courts.

The civil rights movement, however, is united in

determination that Title VI shall not become meaninglesge

words. In litigasit, in administrative proceedings, in

public investigations that we plan to commence, its

deficiencies and the failure to enforce will be exposed.

Turning to another part of the '64 Act, the FEPC

provision, it is far too complex and cumbersome to be

effective. Without action from the community it will be

only words on paper. The members of the Commission were

appointed only this week after more than a ten month wait.

¢

~a

e

nieve no staff. The Comltls ion will be empowered to act

only on July 2 a-year Géxe? the Act was passed. But its

effectiveness will depend largely on complaints filed before

it. Experience with state FEPC’s shows that this is an

ineffective way to operate. The proceedings which the act

contemplates are lengthy and complex. They may have to end

up in court action to be really effective.

We have hired a staff, soon to take the field, which

will have the job of informing members of the community of

their rights under the FEPC law. We are prepared to pursue

cases arising out of violation into and up through the

courts. As the act is written we realistically expect no

astounding progress. But if some little progress comes

and we have exposed the need for fresh legislation, promptly,

a purpose will be served.

eile

aS, But pexond the '64 Act there are areas in which we are

©) create new remedies or use old” ones in dirrerdne: “ways.

In hous 9g, some progress has been made in recent years by

enactment of fair housing laws. Real estate boards have struck

back by ome renums and initiatives, as with California's propo-

sition XIV, which have wiped these laws from the books. These

boards hh ed spread racially restrictive covenants throughout

P ie

the na Lor ntil the courts held then uneforceable. They have

seemed to *" obstacles to free trade erected by real

estate men

not abandoned efforts to segregate communities. But it has

counter to the traditional American idea of the

free market. “And so we have filed one suit, and within a few

days will be Biting several more under the antitrust laws, to

enjoin agreements among broken to carve up a community accord-

ing to their racial notions. ‘Where Negro real estate brokers

have been excluded from the market the financial losses may be

substantial, and the treble damage provision of the Sherman Act

may be a useful deterrent. fie

In the area of criminge law, where overt racial bias i

is difficult to find nowadays, and where the effects of race £

and poverty mix, we are about to make new efforts. Discrimi- é

nation in sentencing long has been recognized, but rarely, if

ever, has been established in fact. Yet, in one particular

area of the law, that of the crime of rape, discriminatory

sentencing in the southern states means that Negroes regularly

are sentenced to death when the victim is a white woman, while

“instances oF sine are not so punished. We are embark-

a massive fact-finding operation in every courthouse in

which such a case has been tried, to put the facts on the record.

We have already done so in Florida. We have such a case pending

in Arkansas. The campaign over the next year will become south- z

wide. If, in fact, we show that the death penalty is applied

in a discriminatory way, we hope to be able to persuade courts

that this violates the equal protection clause of the Constitu-

tion. The death penalty, of course, falls with unequal severity

Ge Negroes and the poor in cases other than rape. Our court- P

room campaign may provide an impetus for legislative repeal with

Bespacé to the other applications,

'These are only a few of the areas into which we must

move if we are to keep up the pace set in the past decade. 4

There is not time to discuss in detail but I would like to i

mention several others. The entire question of protection of ©

the criminal defendant, an issue which touches poor people in

Court decisions. There is as yet, however, very little law

on the question of the rights of defendants between arrest and

trial. There is almost nothing on the practice of prosecutors

of coercing pleas of guilty by raising and multiplying unfounded

charges. There is very little on the law of juveniles who,

under the guise of being protected in juvenile court proceedings,

have been denied fundamental constitutional protections afforded

Aegan ae

sees

older persons, such as the right to a public trial, the right

to bail, the right to the protection of regular rules of evi-

dence.

= Law in this area as in others cannot be declared in

the abstract. It must be forged in actual proceedings. Con-

crete situations are also the impetus which usually encourages

legislatures to take up problems.

Another problem totally untouched by the law so far as

we know is the entire question of who runs our boards of educa-

tion, This is intimately related to questions of segregation,

de facto segregation, and quality education. We are planning

efforts to question the representativeness of some boards under

principles established by the Supreme Court in the reapportion-

ment decisions. We hope to establish reforms but know that at

least we will stimulate debate which may be fruitful.

We are encouraging all our cooperating lawyers to

become involved in the legal aspects of the poverty program,

While the poverty program is not merely a civil rights program,

the civil rights question will not be solved unless its goal

is achieved.

z For PP hast year and a half we have been conducting

civil rights law institutes for our cooperating lawyers in the

South. Members of faculties from leading law schools, includ-

ing several professors from Cambridge, have talked at these

institutes. We feel that this has upgraded the competence of

civil rights lawyers. Ye plato. expand these institutes and

SI ns

AO,

, Ais

to ‘prepare text materials on the new legal areas which we

“will ‘be entering, both North and South.

ea The pwor siaaging we could do, however, would be to

think that ous! efforts as lawyers, no matter how important, ~~

ceppeaive the whole problem. We should recognize,’ however, ©

that our efforts_as lawyers also bring results for society as

a whole beyond our particular interest in civil rights. Ps

Recognition of poverty was forced upon the country in”

part because the civil rights struggle finally made plain

that without other reforms the elimination of racial barriers =: “

ik. We all know what Sputnik meant. But Brown also

sharp awakening because in many places to abolish

ion, required by law or, as is said, de facto, would

ending that special subsidy which white students enjoyed

because Negro education has been financed by appropriation per

Negro student lower than that for whites. To merely average

things out in an integrated system would mean raising the

appropriation for Negroes and lowering that for whites. This

is what is meant when people say that to integrate will lower

educational standards. This, the white majority, of course,

would not tolerate. And so we have found that quite apart from

= Y5%=

integration in ordinary tangible and measurable terms, there

has been a drive to improve education generally.

If we are successful in our efforts to protect criminal

defendants who happen in large measure to be Negro, we will at

the same time expand these protections to whites. If we are

* 5

able to abolish capital punishment for Negroes in rape cases,

“we will make a contribution towards ending that barbarism gener-

“ally. If we start a fruitful dialogue on how boards of educa-

tion are selected, although our eye will be on the civil rights

problem, the community as a whole may become more deeply involved

in its educational system. If we point up the failure of the

bar as a whole to become involved in controversial matters,

we may encourage it to recognize its ancient responsibility.

By an accident of history, it is the must of solving

the race problem that is forcing the country to grapple with

the problems of all.

Many of us are here today because we agree with John

Donne that no man is an island, We seek to live by the

principle of our heritage that we are our brothers' keepers.

But we can only rejoice when virtue is not merely its own

reward, but the reward for each and every one of us, and the

country as a whole,

$

C

O