Holsey v. Armour & Company Judgment

Public Court Documents

August 20, 1984

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Holsey v. Armour & Company Judgment, 1984. a22b9b55-b89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/bd500148-fee4-46c1-bc30-31187db089f3/holsey-v-armour-company-judgment. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

V

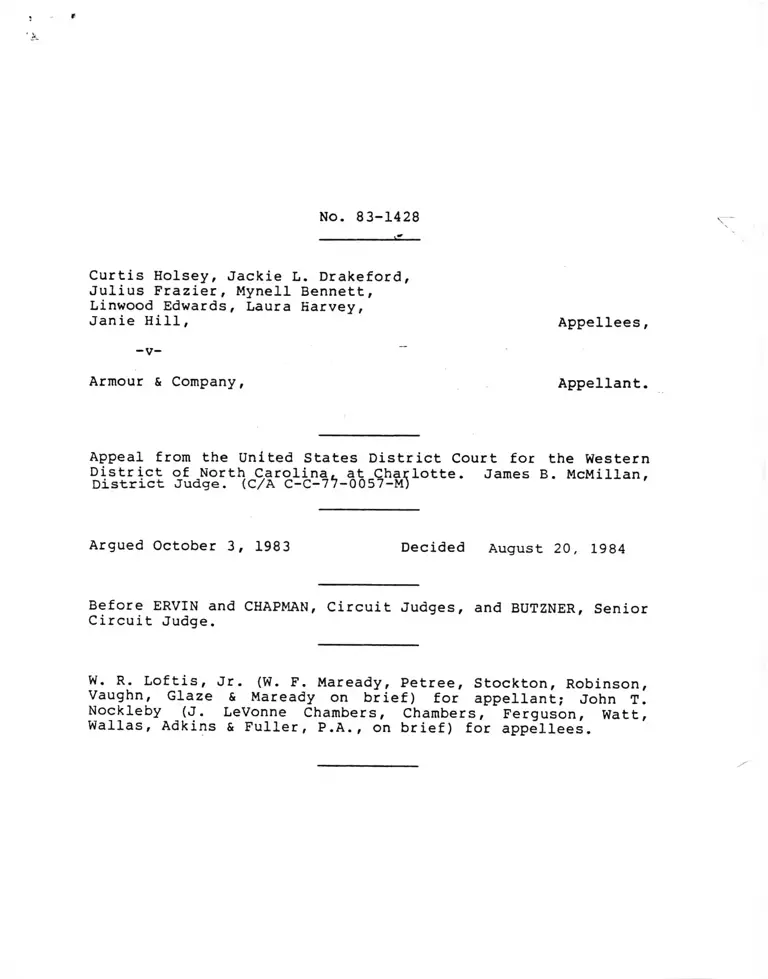

No. 83-1428

Curtis Holsey, Jackie L. Drakeford,

Julius Frazier, Mynell Bennett,

Linwood Edwards, Laura Karvey,

Janie Hill, Appellees,

- v-

Armour & Company, Appellant.

Appeal from the United States District Court for the Western

District of North Carolina, at Charlotte. District Judge. (C/A C-C-77-0057-M) James B. McMillan,

Argued October 3, 1983 Decided August 20, 1984

Before ERVIN and CHAPMAN, Circuit Judges, and BUTZNER, Senior Circuit Judge.

W. R. Loftis, Jr. (W. F. Maready, Petree, Stockton, Robinson,

Vaughn, Glaze & Maready on brief) for appellant; John T.

Nockleby (J . LeVonne Chambers, Chambers, Ferguson, Watt, Wallas, Adkins & Fuller, P.A., on brief) for appellees.

BUTZNER, Senior Circuit Judge:

Armour & Company appeals from a judgment of the district

court entered upon findings that the company had discriminated

against black persons in violation of 42 U.S.C. § 1981 and

Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e

et seq.

Armour's 20 assignments of error encompass virtually

every provision of the court's judgment, which afforded both

individual and class relief.

This case is before us for the second time, and we now

decide:

1) The district court complied with our mandate on re

mand.

2) The district court did not err in allowing certain

class members to intervene and in adjudicating their

claims in the first stage of the bifurcated trial.

3) The provisions of the judgment pertaining to dis

crimination and retaliation in violation of

§§ 703(a) and 704(a) of Title VII, 42 U.S.C.

§ 2000e-2(a) and § 2000e-3(a) against the individ

ual complainants are affirmed with the exception of

those concerning Laura E. Harvey's claims about

overtime work and switchboard training.

4) The class certification is vacated to the extent

that it includes applicants affected by Armour's

hiring practices and employees who sought promotion

to office and management positions other than sales

representatives and supervisors. In all other re

spects, the class certification is affirmed.

5) The findings of a pattern and practice of discrimination because of race with regard to promotions

into sales and supervisory positions, and of retali

ation in violation of § 704(a) are not clearly erro

neous .

2

)

6) Relief granted Curtis Holsey and Julius Frazier must

be modified to allow them retroactive departmental

seniority based on their transfer date and not their

date of hire. Injunctive relief granted incumbent

employees who applied for positions other than sales

or supervisory jobs is vacated. Relief granted job

applicants is vacated. All other relief granted in

dividual complainants and the class is affirmed.

7) The award of attorneys' fees is vacated and remanded

to the district court for reconsideration.

I

Curtis Holsey, Jackie L. Drakeford, and Julius Frazier

filed charges with the Equal Employment Opportunity Commis

sion, received right-to-sue letters, and timely commenced this

class action against Armour, the Meat Cutters Union, and its

Local 525. They alleged that the defendants' policies and

practices had discriminated against them and the class members

in hiring, promotions, layoffs, recalls, and other terms of

employment because of their race.

The district court allowed Mynell Bennett to intervene as

a plaintiff before trial. Bennett had filed a charge with the

commission alleging discriminatory discharge and maintenance

of racially separate jobs. She received a right-to-sue letter

and timely moved for leave to intervene.

The district court certified a class. It held that

Armour had discriminated against the complainants and the

class because of their race in violation of § 703(a) and that

it had retaliated against them in violation of § 704(a). It

granted individual and class relief and awarded counsel fees.

The court dismissed the claims against the union. Before

3

entry of judgment, three class members who had presented

claims at the trial moved to intervene as plaintiffs, and

their motions were granted.

Armour appealed. We vacated the judgment with instruc

tions to reconsider the findings of fact and conclusions of

law and to clarify the allocation of evidentiary burdens in

light of the Supreme Court's intervening decision in Texas De

partment of Community Affairs v. Burdine, 450 U.S. 248

(1981). Holsey v. Armour & Co., 683 F.2d 864 (4th Cir. 1982).

After conducting proceedings on remand, the district court

entered an amended judgment from which Armour now appeals.

II

Before turning to the merits of this appeal, we address

Armour's contention that the district court did not follow our

mandate.

On remand, the district court conducted a hearing at

which the plaintiffs proposed changes and responded to factual

contentions that Armour had made on appeal. Armour had no

specific proposals at the time, except a request that all ad

verse findings be reversed as error. The district court then

directed both parties to file specific proposals for changes

in the findings of fact, conclusions of law, and the judgment.

The parties submitted lengthy responses which the court con

sidered before it entered its amended judgment. After re-ex

amining its findings of fact and conclusions of law, the court

adopted suggestions from both parties where it found the

4

changes were consistent with its opinion and accurate with

respect to the evidence.

We conclude that the district court has complied with our

mandate and its findings are demonstratively the result of the

court's independent judgment. Also, the record establishes

that the district court placed the burden of proof on the com

plainants in accordance with United States Postal Service v.

Aikens, 103 S. Ct. 1478 (1983), and Texas Department of Commu

nity Affairs v. Burdine, 450 U.S. 248 (1981).

H I

The district court found the following background facts

about the company's business. Armour has operated a meat

processing facility in Charlotte, North Carolina, since 1958.

There are four production departments at the plant: a beef

department, responsible for fabrication of beef; a sausage de

partment, responsible for production of processed meats; a

maintenance department, responsible for vehicle repairs and

maintenance of equipment; and, an operations department,

responsible for the distribution of products. In addition,

the facility has office employees, including sales representa

tives.

Employees in the four production departments are repre

sented by a union, which entered into collective bargaining

agreements that establish seniority rights. Seniority governs

5

job progression, daily replacement work, temporary and perma

nent layoff, and recall rights.1

Armour increased its production work force between 1969

and 1973 from approximately 90 to over 200 employees. Since

1974, however, sales have declined and the production work

force has been cut back. In March 1980, when this case was

tried, there were 133 production workers, of whom 50 worked

regularly.

Armour filled sales and supervisory positions by trans

ferring or promoting incumbent employees or by hiring new em

ployees. Armour does not post vacancies or publish selection

criteria for these jobs. The personnel are selected by a

white managerial staff, applying subjective standards. Al

though a number of experienced black employees sought sales or

supervisory positions, Armour managers had never compared the

qualifications of these black employees with the white employ

ees who were hired.

No black employee worked as a supervisor before Holsey,

Frazier, and Drakeford filed charges with the commission in

1974. No black employee worked as a sales representative

until August 1977, more than three years after plaintiffs

filed charges with the commission. A company official ex

plained to an employee that Armour did not hire black persons

in the sales department because customers would not buy from

them.

1. The agreements do not cover office employees (in

cluding sales), supervisors, or probationary employees.

6

IV

Contrary to Armour's contention, we conclude that the

district court did not abuse its discretion in allowing class

members Janie Hill, Linwood L. Edwards, and Laura E. Harvey to

intervene after trial and before the entry of judgment.

Because Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 24 is silent as to

what constitutes a timely application for intervention, the

determination is left to the court's discretion. The court

must consider all the circumstances in each case, not just to

what point the suit has progressed. NAACP v. New York, 413

U.S. 345, 364-69 (1973). The most important consideration in

reviewing the decision is whether the delay prejudiced the

parties. See Hill v. Western Electric Co., 672 F.2d 381, 385-

87 (4th Cir. 1982).

Intervenors Hill, Edwards, and Harvey were witnesses at

trial as well as class members. They suffered from the same

practices challenged by the plaintiffs. Armour has not demon

strated any prejudice resulting from the intervenors' metamor

phosis from class member witnesses into plaintiffs. See Brown

v. Eckerd Drugs, Inc., 663 F.2d 1268, 1278 (4th Cir. 1981),

vacated on other grounds, 457 U.S. 1128 (1982). Whether they

were allowed or denied intervention, their testimony was rele

vant and the court would be justified in making factual find

ings and stating conclusions pertaining to the discrimination

they depicted.

Armour's second contention regarding the intervenors is

that the district court erred in ajudicating their individual

<

7

claims at the liability stage of the bifurcated trial. The

company claims it should be allowed to rebut the individual

claims at the second stage of the proceedings, relying on this

court's decision in Sledge v. J.P. Stevens & Co., Inc., 585

F.2d 625 (4th Cir. 1978) .

Armour had a full opportunity to defend against the in

terveners' claims, and it introduced evidence in opposition to

them. Moreover, at the first stage of the trial, the inter-

venors met a more rigorous burden of proof than would have

been required had they waited until the second stage when they

would receive the benefit of a finding of class-wide discrimi

nation. See Sledge, 585 F.2d at 637.

Adjudicating the intervenors' claims at the first stage

of the proceedings is not forbidden by Sledge. On the

contrary, that case deals with the consequences of class

members who did not litigate their individual claims at the

first stage. In Sledge, we held that class members cannot be

dismissed for omitting to prove their individual claims at the

first stage when they had been led to believe that this would

be the subject of the second stage. 585 F.2d at 637-38 .

Moreover, in Cooper v. Federal Reserve Bank, 52 U.S.L.W. 4853,

4857 (U.S. June 25, 1984), the Supreme Court held that

"[w]hether the issues framed by the named plaintiffs before

the court should be expanded to encompass the individual

claims of additional class members is a matter of judicial

administration that should be decided in the first instance by

the district court."

8

V

Seven employees allege disparate treatment. Their claims

are discussed separately.

Curtis Holsey

The district court found that because of Holsey's race

and his efforts to challenge Armour's racial practices, Armour

denied him the opportunity to exercise his bumping privileges

in the sausage department to avoid lay-offs in the beef

department.

The court found the following facts. Holsey was hired by

Armour on December 1, 1969, and assigned to the operations de

partment. At the time, black employees were concentrated in

operations, and there were no black males in sausage and but

one or two black employees in beef. After three weeks, Holsey

was transferred to a clean-up job in beef, and subsequently he

bid on better jobs in beef. His supervisor discouraged him

from bidding on these promotions, but he was awarded the jobs

because of his seniority. He was harassed in his new posi

tions by being assigned duties that were not part of his job,

was denied assistance in training and in the performance of

his job, and was improperly disciplined. Holsey filed numer

ous grievances about the harassment, some of which were ad

justed by Armour. In 1974, after Armour refused to let him

grieve discrimination because of his race, Holsey filed a

charge with the commission.

Permanent layoffs occurred in the beef department on

three occasions: September 2, 1974; February 26, 1975; and

9

February 24, 1976. The collective bargaining contract allowed

employees who were permanently laid off and had five years'

company seniority to bump junior employees permanently as

signed to other departments, but they could not bump temporary

employees. The bumping employee would then have recall rights

established in the new department. Holsey had established

five years' seniority on December 1, 1974, and he attempted to

bump into the sausage department, establish recall rights

there, and avoid further layoff. Armour officials told Holsey

that no junior employees were working full time in sausage and

that he could bump only junior employees in operations.

There was conflicting evidence as to whether three white

and one black employee in sausage, all junior to Holsey, con

tinued to work during the 219 days Holsey was on layoff. The

court determined that Armour's explanation was unreliable and

inconsistent with the documentary evidence. It found that the

four junior employees were not working as "temporary replace

ments" in sausage. They had, in fact, worked during much of

their "layoff." Even if they had been working on a day-to-day

basis, Appendix I of the collective bargaining agreement pro

vides that they are to be "laid off in preference to employees

who have bumped into this department when the need for tempo

rary replacement no longer exists." The black employee in

sausage who continued to work while Holsey was laid off was

not active in challenging Armour's discriminatory practices.

This is consistent with Armour's pattern of retaliation

against Holsey for his efforts. The court found Armour's

10

explanation for denying Holsey's request to bump into sausage

to be pretextual.

Armour contends that a comparison of Holsey's timecards

and those of the junior sausage employees dispute Holsey's

testimony that these employees worked while he was laid off.

The company also offered evidence that he had refused work on

occasions and was under medical disability during layoff peri

ods .

The timecards introduced by Armour indicate some of the

junior white employees were not working when Holsey was laid

off, but these timecards did not cover the entire period

Holsey was on layoff. The district court noted in its find

ings that Holsey was out 219 days during layoffs in 1974,

1975, and 1976, while the four junior employees were laid off

from 82 to 132 days. The district court could infer that at

least some junior employees were working part of the time

Holsey was on layoff. Similarly, the 53 days Holsey was out

on medical disability between July 1975 and January 1976 do

not explain why he was disqualified from bumping into sausage

when he was available for work. Armour's testimony that

Holsey refused work during this period was in dispute. Holsey

denied that he had refused. The court weighed the credibility

of the witnesses and believed Holsey.

The district court properly considered evidence of

Armour's harassment of Holsey before he filed his charge with

the commission as probative of the company's racial attitudes.

In United Airlines v. Evans, 431 U.S. 553 , 558 (1977), the

11

Supreme Court stated that such time-barred acts "may consti

tute relevant background evidence in a proceeding in which the

status of a current practice is at issue . . .

Also, the district court correctly treated Holsey's claim

that he was denied the opportunity to bump junior employees in

sausage as disparate treatment. The court's decision does not

rest on disparagement of the seniority system. Holsey proved

by a preponderance of the evidence that Armour manipulated

bumping to deny him and other black employees the privileges

accorded by the seniority system in retaliation for their com

plaints about the company's discriminatory practices.

Julius Frazier

Frazier was hired by Armour on July 21, 1969, and as

signed to the operations department. He soon signed a job

posting and was transferred to the beef department, where he

worked continuously until the 1973 and 1974 layoffs. In

August 1973, he was denied the opportunity to avoid layoff by

bumping into sausage. In March 1974, he filed a charge with

the commission complaining that he was discriminatorily denied

his bumping rights. Frazier was laid off again for two weeks

in December 1974 because he was not allowed to bump into sau

sage, although junior white employees in sausage continued to

work. The district court found that Frazier was denied his

contractual right to bump into sausage during the two-week

12

period in 1974 because of his race and his efforts to exercise

2rights under Title VII.

Frazier testified that two junior white employees, main

tenance employee Kyle and sausage employee Newman, were

allowed to work while he was on layoff. In rebuttal, an

Armour official offered the same explanation that was given

for denying Holsey an opportunity to bump into sausage— there

were no vacancies.

The district court, noting numerous inconsistencies and

conflicting documentary evidence, found Armour's explanations

unreliable. Additionally, the district court properly con

sidered evidence that Armour had historically limited opportu

nities for black males to work in sausage and that it harassed

black employees who challenged the company's racial practices.

Evidence of a general atmosphere of discrimination may be con

sidered with other evidence bearing on motive in deciding

whether the plaintiff has met his burden of showing the de

fendant's articulated reasons are pretexts. Sweeney v. Bd.

of Trustees of Keene State College, 604 F.2d 106, 112-13 (1st

Cir. 1979). See Furnco Construction Corp. v. Waters, 438

U.S. 567, 580 (1978) .

2. The district court ruled that Frazier was not dis

criminator ily denied bumping rights in 1973 because he

had not yet established sufficient seniority. Frazier

also failed to prove his claim that Armour discriminator- ily denied him a promotion into sales.

13

Jackie L. Drakeford

The district court found that Armour denied Drakeford

supervisory and sales positions because of his race. The

court also found that after Drakeford was promoted to super

visor, the company denied him equal status with white super

visors and harassed him in other ways, forcing him to termi

nate his employment in violation of § 704(a) of Title VII.

The court found that Drakeford was hired by Armour on

June 17, 1969. Although he told his supervisor and department

manager that he was interested in a foreman position in 1973,

he was passed over on more than eight occasions between July

1973 and February 28, 1977, by junior white employees. The

court noted that Armour had no black supervisor during this

period. Indeed, no black had been made a supervisor until

Drakeford's promotion in 1977. The court found that Drakeford

was more qualified than the junior white employees because of

his seniority, past work performance, and overall experience

with Armour.

Armour officials testified that no production employees,

black or white, were considered for foreman positions after

1971 when the company instituted a trainee program limited to

college graduates. This program was instituted in order to

bring in persons who would stay with the company. Of the

eight trainees hired between 1971 and 1974, all but two left

the company after a short time, including four who were

3. The parties and the court used the terms

and supervisor" interchangeably. "foreman"

14

discharged. The remaining two transferred to other jobs at

Armour. None of the trainees selected was black.

The court found that the company never validated the cri

teria for selecting program candidates and terminated the pro

gram in 1975 when it became clear that the criteria and pro

gram didn't produce the desired results. Moreover, the record

discloses that Armour in 1972 hired a white foreman who was

not in the program. Between 1975, when the program was termi

nated, and 1977, when Drakeford was appointed, there was a

foreman vacancy which Armour filled with a white appointee.

The district court also found that Drakeford was denied a

sales position in 1975 and thereafter because of his race.

The court found that Drakeford had expressed his interest in a

sales position to the sales manager in 1975 and was told he

would be considered for the next vacancy. Sales jobs are not

posted, and an Armour official testified that one way a labor

er could move into a salaried job was to talk to a supervisor.

Drakeford was never asked to complete an application and did

not do so.

Armour had no written standards for hiring sales repre

sentatives. An all-white staff selected new sales representa

tives, applying subjective standards. The district court

found that Drakeford was available and qualified for a sales

position, but sales vacancies were filled with white employees

with no greater qualifications than Drakeford. Furthermore,

no black employee or applicant had been hired as a sales rep

resentative until after this action was filed.

15

Armour s contention that Drakeford's testimony is insuf

ficient to establish a prima facie case because he made only a

casual inquiry" regarding a sales position is refuted by

Teamsters v. United States, 431 U.S. 324, 365-67 (1977).

There the Supreme Court held that a person who is interested

in seeking a position but has not formally applied may be en

titled to relief under Title VII. The Court reasoned that an

employer's policy of discrimination "can be communicated to

potential applicants more subtly but just as clearly by an em

ployer's actual practices— by his consistent discriminatory

treatment of actual applicants, by the manner in which he pub

licizes vacancies, his recruitment techniques, his response to

casual or tentative inquiries, and even by the racial or eth

nic composition of that part of his work force from which he

has discriminatorily excluded members of minority groups."

431 U.S. at 365.

In view of the district court's findings that Armour had

no black employees in sales at the time of Drakeford's inquiry

and had actively discouraged them from applying for sales

jobs, Drakeford's claim is clearly within the Teamsters'

standard for nonapplicants.

The district court made the following findings in support

of its conclusion that Drakeford was constructively discharged

by Armour in violation of § 704(a). Drakeford was promoted to

supervisor on February 22, 1977, after filing a charge with

the commission and several days before this action was filed.

He was put on a night shift so that a white supervisor could

16

get the day shift, although Drakeford was hired to replace a

day-shift supervisor. The shift was adjusted a second time to

accommodate another white supervisor. The general foreman at

Armour granted leave to employees supervised by Drakeford

without advising him. Despite complaints to his superiors,

the problem continued. His request for a transfer was re

jected by the company. As a result of the degrading treat

ment, he left Armour on November 28, 1978. The district court

found that the company knew Drakeford was denied equal status

as a supervisor and was subjected to harassment but failed to

correct these practices. It held that "the employment condi

tions imposed by the company forced Drakeford to terminate his

employment in violation of section 704(a)."

Armour argues that it must be shown that the employer

acted with the intent to force the employee to resign in order

to establish constructive discharge. The company claims that

there is no evidence that it sought to make Drakeford quit his

job.

The elements of a constructive discharge are stated in

J.P. Stevens & Co., Inc. v. NLRB, 461 F.2d 490, 494 (4th Cir.

1972), as follows: "Where an employer deliberately makes an

employee's working conditions intolerable and thereby forces

him to quit his job . . . the employer has constructively dis

charged the employee . . . ." A constructive discharge vio

lates § 704(a) when the record discloses that it was in retal

iation for the employee's exercise of rights protected by the

Act.

17

To act deliberately, of course, requires intent. But

direct evidence of intent is unnecessary. Circumstantial

proof suffices. United States Postal Service v. Aikens, 103

S. Ct. 1478, 1481 n.3 (1983). The fact that higher officials

knew of Drakeford's untenable position and took no action to

correct it supports the district court's finding that the em

ployment conditions were "imposed by the company." This find

ing satisfies the requirement of deliberateness.

The district court's findings also satisfy the other re

quirements of a constructive discharge in violation of

§ 704(a). The company refused to appoint Drakeford a super

visor until after he filed a charge with the commission. He

was then systematically harassed and denied equal status with

white supervisors. The court's finding that these conditions

forced him to resign is not clearly erroneous.

Linwood L. Edwards

The district court held that Linwood Edwards was denied a

supervisory position because of his race.

The court made the following findings. Edwards was hired

by Armour in 1949 at its Asheville facility and subsequently

promoted to supervisor. When the plant closed in 1969,

Edwards was transferred to the Charlotte plant and assigned as

a laborer. Armour's practice had been, and continued to be

throughout this litigation, to transfer employees from closed

facilities to other facilities in basically the same job posi

tion. For example, three white supervisors from closed plants

18

transferred into the Charlotte facility and were brought in as

supervisors. Edwards requested a supervisory assignment after

his transfer but was passed over for junior white employees

who were hired as, or promoted to, supervisors. Armour had no

black supervisor until 1977, when Drakeford was promoted after

filing his charge with the commission. Edwards had the exper

ience and knowledge of Armour's operation to qualify him for a

supervisory position at the time he was transferred to

Charlotte and when job vacancies occurred between 1971 and the

trial.

Armour contends that the court ignored the legitimate

nondiscriminatory reasons it offered and that the finding of

pretext is clearly erroneous.

On the contrary, the court's findings of fact specifical

ly addressed the testimony of Armour officials and found that

the explanations were not credible. One reason offered by an

official for not promoting Edwards was that his supervisory

experience in Asheville occurred in a nonunion plant and the

Charlotte plant was unionized. The company, however, con

tinued to bypass him in favor of junior white employees with

little or no union experience even after Edwards had accumu

lated several years union experience at Charlotte. The offi

cial also testified that Edwards wasn't offered a supervisory

position because he didn't think he would have taken it.

Finally, he testified that Edwards was not selected because of

his "interaction within the plant, his ability to communicate,

take instructions," and because he lacked aggressiveness. The

19

district court found that Edward's satisfactory performance as

a supervisor in Asheville showed that this "after-the-fact"

explanation was false.

Mynell Bennett

The district court found that Armour prevented Bennett

from acquiring seniority because of her race and that Armour

discharged her in violation of § 704 (a). Armour contends that

these conclusions are clearly erroneous and that Bennett's

claim is barred by laches.

The court made the following findings of fact. According

to the collective bargaining agreement in effect in 1971, a

new employee was classified as a probationary employee until

he or she worked 30 days during a consecutive 60-day period.

At that time the employee acquired a permanent status, with

seniority and its concomitant rights. Probationary employees

were called in to work on a daily or weekly basis when needed

by a supervisor. Although no standards governed the super

visors' discretion in calling probationers to work, the prac

tice was to call in the most senior employee.

Bennett started working in Armour's sausage department as

a probationary employee in July 1971. In August, Armour hired

three white women from the closed Swift & Company plant.

These women, although junior to Bennett, were called in over

her. Armour also employed white students to work during the

summer, at the same time Bennett was trying to establish sen

iority. As a result, Bennett was unable to acquire permanent

status after six months of probationary employment.

20

In January 1972, Bennett asked her supervisor if the com

pany had refused to call her to work because of her race or her

performance. The supervisor assured her that her performance

was acceptable, but after the conversation she was not called

to work. Two weeks later, upon inquiry, she was told she had

been discharged.

The court found that Bennett was qualified to perform the

work and that the junior white employees were called in over

her because of her race. It also found that she was dis

charged in retaliation for complaining about Armour's discrim

inatory refusal to call her to work and because of her race.

Armour claims that the probationary employees from Swift

were called in over Bennett because their experience at Swift

and their familiarity with the machines in the sausage depart

ment was of value to the company. The court specifically

found this explanation not credible. According to an Armour

official, an employee hired into the company from Swift would

not be given any preference over employees already working at

Armour. The official also testified that probationary employ

ees were evaluated during the probationary period by a subjec

tive determination on the part of their supervisor. No writ

ten or objective comparison between the Swift employees and

incumbent Armour employees was made.

The court's finding that Armour discharged Bennett in re

taliation for her inquiry as to whether she was not called to

work because of her race is supported by testimony and docu

mentary evidence. When Bennett made the inquiry in January

21

1972, she was assured by her supervisor that her work was

satisfactory. Documents in her personnel file support this

evaluation. After Bennett made her complaint, she was never

called in again and was fired with no explanation. In a North

Carolina Employment Security Commission form completed by

Armour, the company indicated that she was discharged in

January 1972 for unsatisfactory performance. The court cor

rectly concluded that the discharge was a violation of the

§ 704(a) "opposition clause." Bennett's inquiry as to whether

she had been prevented from acquiring seniority because of her

race constitutes opposition under the statute. See Berg v.

La Crosse Cooler Co., 612 F.2d 1041 (7th Cir. 1980).

Finally, Armour contends that Bennett's claims are barred

by laches because she waited four and a half years before

bringing suit, and the company was prejudiced because

Bennett's supervisor had died before trial. Bennett filed a

charge with the commission on January 27, 1972. The

commission investigated the charge and on August 25, 1976,

issued a determination of reasonable cause. When conciliation

efforts failed, Bennett received a right-to-sue letter on

May 17, 1977. Bennett then moved to intervene in this

proceeding on June 2, 1977.

In order to apply laches, there must be a finding that

the plaintiff delayed inexcusably in filing suit and that the

delay resulted in undue prejudice to the defendants. We hold

that Bennett's decision to rely on the commission's adminis

trative process before initiating a private suit is not

22

inexcusable delay. See Bernard v. Gulf Oil Co. , 596 F . 2d

1249 , 1256-58 (1979) , adopted, 619 F.2d 459, 463 (5th Cir.

1980) (en banc).

Janie Hill

The district court found that Hill was denied the oppor

tunity to establish seniority because of race.

In addition to the findings described under Bennett's

claims, the court made the following findings of fact. Hill

was hired by Armour in 1971 as a probationary employee in the

sausage department. She was passed over for work in favor of

junior white employees, including the three women who had been

hired from Swift. As a result, Hill was unable to acquire

permanent status and seniority until March 1972, after the

junior white employees from Swift had established seniority.

Armour's assertion that the Swift employees were more effi

cient than Hill was not credible, given the company's lack of

objective measures of efficiency, its official's testimony

that the Swift employees wouldn't be given preference over in

cumbent employees, and Hill's satisfactory performance at

Armour. The district court credited Hill's testimony and

found that the company intentionally discriminated against her

because of her race.

Armour contends that the court's conclusion is clearly

erroneous because the evidence demonstrates that no racial mo

tive was involved in its decision to call certain junior white

employees over Hill. The existence of discriminatory intent,

23

\

according to Armour, is belied by the fact that black employ

ees sometimes acquired seniority immediately and white employ

ees sometimes took a year to acquire seniority.

Armour's argument does not expose any error in the dis

trict court's judgment. The district court's findings of in

tentional discrimination were not based on a comparison of the

length of time black and white employees remained probation

ers. The findings were based on the fact that the probation-

ary periods of Bennett and Hill were unlawfully extended be

cause when Armour assigned work, it favored junior white em

ployees with no superior qualifications.

Laura E. Harvey

The district court held that Armour discriminated against

Harvey in violation of § 703 (a) by depriving her of equal

status in her supervisory position. The company also denied

her a sales position because of her race, and, when she com

plained about Armour's racial practices, she was harassed in

violation of § 704(a).

The court made the following findings of fact. Harvey

was hired by Armour as a keypunch operator in January 1973.

She was the first black employee in data processing and only

the second ever employed in the administrative office. In

1979, she was promoted to a supervisory position, replacing a

white employee as lead key operator. Despite the fact that

her predecessor had supervised both black and white employees,

Harvey was told that the white employees would be supervised

24

by the data processing manager because they would not take

instructions from her. In March 1979, Harvey resigned because

this arrangement created problems with work assignments among

the employees. In May 1979, she returned to work as lead key

punch operator but without supervisory duties.

*The district court properly concluded that Armour vio

lated Title VII by preventing Harvey from supervising white

employees because they did not wish to take orders from a

black person. Section 703(a)(2) provides that it shall be an

unlawful employment practice for an employer "to limit, segre

gate, or classify his employees . . . in any way which would

deprive or tend to deprive any individual of employment oppor

tunities or otherwise adversely affect his status as an em

ployee, because of such individual's race . . . ." Racial

segregation of the employees Harvey supervised because of her

race limited her employment opportunities as a supervisor and

adversely affected her status. Cf. Rogers v. EEOC, 454 F.2d

234, 237-38 (5th Cir. 1971); Allen v. City of Mobile, 331 F.

Supp. 1134, 1144 (S.D. Ala. 1971).

In regard to the claim pertaining to a sales position,

the district court found that Harvey applied for sales jobs in

1976, 1977, and 1978. The court found that Harvey was quali

fied to work in sales. She was highly recommended by her

supervisor for her attitude, motivation, and performance. In

a 1977 performance evaluation, her supervisor noted that her

sales knowledge was underutilized. The court found that

Armour had rejected Harvey for sales because of her race.

25

Despite Armour's explanation that there were few sales open

ings from 1976 to 1978 and, in most cases, jobs were awarded

to persons with significant prior sales experience, the court

found convincing Harvey's evidence that the company had a

practice of excluding blacks from sales jobs. Harvey's super

visor told her the company didn't hire black salespersons be

cause the customers wouldn't buy from them. An Armour offi

cial who participated in hiring sales employees between 1975

and 1978 testified that a high school education was the only

established criterion for hiring sales persons. Harvey had a

high school diploma as well as the sales knowledge and other

attributes noted in her performance evaluation. In the face

of evidence that the company did not hire black sales repre

sentatives, Armour's rebuttal on the basis of relative quali

fications does not demonstrate that the district court's find

ings are clearly erroneous. See EEOC v. Ford Motor Co., 645

F. 2d 183 , 188 n.3 (4th Cir. 1981), rev' d in par t on other

grounds, 458 U.S. 219 (1982).

There is one aspect of Harvey's claim that is not sup

ported by the record. The evidence does not disclose that

Armour violated § 704(a) by retaliating against her because of

any complaint. She was not assigned overtime work or denied

switchboard training in retaliation or because of her race.

There is no evidence that any white employee requested the

switchboard training and received it. There was only one

switchboard position at Armour, and it was occupied by a white

woman who was hired the same year as Harvey and remained in

the position at the time of trial.

26

Consequently, we vacate that portion of the district

court's judgment dealing with Harvey's complaint about over

time work and switchboard training. Because the findings

about these claims were not necessary to the findings that

Armour discriminatorily denied Harvey equal supervisory

status and a sales position because of her race, affirmance of

those claims is not affected.

Summary

With respect to a disparate treatment claim, United

States Postal Service v. Aikens, 103 S. Ct. 1478, 1482 (1983),

reiterates:

The "factual inquiry" in a Title VII case is

"whether the defendant intentionally discriminated against the plaintiff." . . . In other words, is

"the employer . . . treating 'some people less fa

vorably than others because of their race, color, religion, sex, or national origin.'"

Thus, when the evidence introduced by both the employee and

the employer has been admitted, the ultimate question is

"whether the [employer] intentionally discriminated against

the [employee]." 103 S. Ct. at 1482. The burden of proving

intentional discrimination is on the employee. As in any

other case, intent, a state of mind, is a fact that can be

proved by indirect or circumstantial evidence. 103 S. Ct. at

1482-83. A distric£_caurt's finding of intentional discrimi-

nation on account of rj :his discrimination, is

encompassed by Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 52(a). A court

of appeals is obliged to accept the finding unless it is

clearly erroneous. Pullman-Standard v. Swint, 456 U.S. 273,

27

287 (1982). "A finding is 'clearly erroneous' when although

there is evidence to support it, the reviewing court on the

entire evidence is left with the definite and firm conviction

that a mistake has been committed.'' United States v. United

States Gypsum Co., 333 U.S. 364, 395 (1948).

These precepts have governed our review of the district

court's findings about the seven individual claimants. With

the exception of Harvey's overtime and switchboard claims, we

conclude that the district court's findings that Armour inten

tionally discriminated against the complainants because of

their race are not clearly erroneous. We also conclude that

the court's findings of retaliation in violation of § 704(a)

are not clearly erroneous. The provisions of the judgment

pertaining to the individual claims, except as noted above,

are affirmed. VI

VI

Armour assigns error to the district court's judgment

pertaining to the class on both substantive and procedural

grounds.

As amended on remand, the court's certification of the

class included:

All black applicants for employment and black

employees of the Company's Mecklenburg County,

North Carolina facility who have been adversely af

fected, at any time since July 27, 1971 (six months

prior to Bennett's charge filed with the EEOC), by the Company's racially discriminatory employment

practices involving promotions or hiring into Of

fice and management positions, including Sales and

foreman positions, and retaliation for having op

posed discriminatory practices or having exercised

rights protected under Title VII.

28

The district court found a pattern and practice of retal

iation in violation of § 704 (a) . It also found that the com

plainants had demonstrated a pattern and practice of limiting

black candidates to certain jobs, totally excluding them from

supervisory and sales jobs, and treating them differently from

white applicants and employees because of their race. It

found that although black candidates were available and quali

fied for sales and supervisory positions, and vacancies ex

isted, Armour did not select them because of their race.

The findings with respect to class discrimination wer,e

based on evidence of specific instances of intentional dis

crimination and statistical evidence. The district court ac

cepted plaintiffs' expert testimony that between 1965 and

Drakeford's promotion in 1977 Armour brought in 37 supervi

sors. Twenty-seven were promoted from within and ten were new

hires. Black persons constituted 25.11% of the outside avail

able workforce, yet none was hired. As for sales, between

1965 and Ennis Graves's employment in August 1977, Armour pro

moted or hired 64 sales representatives. Plaintiffs' expert

used the data on these employees to determine the qualifica

tions expected of sales representatives. Between 1971 and the

trial date, qualified black persons constituted 8.69% of the

external and 20.71% of the internal available workforce. Only

29

one black person was hired as a sales representative despite

23 sales vacancies between 1971 and trial.^

Armour offered several explanations for these hiring pat

terns through one of its witnesses. The district court, how

ever, refused to credit his testimony, finding that his ad

mitted misrepresentations, decorum, and the conflicting docu

mentary evidence made his testimony unreliable. The court

also noted nine instances in the record where Armour officials

admitted the company had no explanation for its actions. Con

sequently, the district court held that plaintiffs had estab

lished a pattern and practice of discriminatory treatment

towards members of the class.

Armour claims that the finding of classwide discrimina

tion was unsupported. It asserts that the plaintiffs' statis

tical evidence was flawed and, without any statistical showing

of underutilization, there remained only "evidence of isolated

instances" of discrimination.

First, we note that the complainants' testimony as to in

stances of discrimination establish more than isolated or "ac

cidental" discriminatory acts. See Teamsters, 431 U.S. at

336. The testimony of both employees and company officials

that the district court relied upon in concluding classwide

The district court rejected Armour's contention

that Virginia Davis, a black female employee who worked

in the sales office as a telephone clerk between December

1976 and February 1977, was the first black employee with

sales duties. Relying on the testimony of an Armour of

ficial that the first black sales representative was

hired in August 1977, the district court found that Davis had only clerical duties.

30

and individual liability clearly established a pattern of in

tentional discrimination. For example, Harvey testified,

without rebuttal from Armour, that she was informed by her

manager that black people were not hired in sales because cus

tomers wouldn't buy from them. Also, Armour's practice of not

posting sales or supervisory vacancies, and its practice of

using a white managerial staff who relied on unwritten sub

jective criteria for making promotion decisions, support a

finding of a pattern and practice of classwide discrimination.

Such evidence provides a substantial basis upon which a dis

trict court may infer that discrimination was the regular

practice.

The district court rejected Armour's expert testimony

that the sample of supervisors and sales representatives be

tween 1971 and 1977 indicates no discrimination in the promot

ing or hiring of black employees.^ It found that (1) the

sample for the period was too small to establish a reliable

statistical pattern; (2) Armour's availability data was based

on a static work force of employees as of December 31, 1977,

with no consideration of the qualifications or work experience

Armour's expert testified that the underrepresenta

tion of black employees in sales and supervisory posi

tions came within one standard deviation, an acceptable

margin of disparity. This is only true, however, if pro

motions and hires made after commencement of this action

are included. We find no error in the fact that the dis

trict court minimized the significance of evidence of Armour's postcomplaint hiring and promotion of black em

ployees. See EEOC v. Ford Motor Co., 645 F.2d 183, 197

(4th Cir. 1981) , rev1d in par t on other grounds, 458 U.S.

219 (1982); Rich v. Martin Marietta Corp., 522 F.2d 333,

346 (10th Cir. 1975).

31

of employees actually hired; and, (3) after evaluating the

manner and decorum of both parties' expert witnesses, the

plaintiffs' availability and utilization data was more

reliable.

We find no error in the district court's decision to re

ject Armour's statistical analysis and accept plaintiffs' ex

pert testimony. Armour's argument that the district court im

properly considered hiring data between 1965 and 1977— well

before June 27, 1971, when the - company's potential liability

began to run--might be persuasive if the company had virtually

no vacancies in sales or supervisory positions between

June 27, 1971, and March 4 , 1977, when this suit was filed.

It might then be argued that low turnover and a decrease in

hiring account for the statistical disparities after 1971,

rather than post-charge discrimination. The record shows,

however, that there were 15 new vacancies in sales and 18 in

supervisory positions during this period. The practices ap

parent before 1971 are consistent with the pattern during the

relevant period.^ No black persons were hired to fill these

positions except for Drakeford, who was promoted four days be

fore the suit was filed and one month after the commission

issued him his right to sue letter. Job offers made after

learning of a charge "are entitled to little weight." EEOC v.

6. Moreover, because the evidence shows there waslittle change in Armour's employment practices being

challenged, the precharge statistical evidence is rele

vant. See Hazelwood School Dist. v. United States, 433

U.S. 299 , 309 n . 15 (1977) .

32

Ford Motor Co 1981) , rev1d in645 F.2d 183, 197 (4th Cir.

part on other grounds, 458 U.S. 219 (1982)P

Statistical proof in Title VII cases must be evaluated in

light of "the surrounding facts and circumstances." Teamsters

v. United States, 431 U.S. 324, 340 (1977). As Justice

Rehnquist made clear in a separate concurring opinion in

Dothard v. Rawlinson, 433 U.S. 321, 338 (1977): "It is for

the District Court, in the first instance, to determine

whether these statistics appear sufficiently probative of the

ultimate fact in issue . . . . In making this determination,

such statistics are to be considered in light of all other

relevant facts and circumstances." In view of Armour's method

of making promotion decisions during the relevant period and

the evidence of specific discriminatory acts, we cannot say

that the district court was clearly erroneous in finding a

pattern and practice of intentional discrimination against the

class.

Similarly, because of Armour's pervasive harassment and

retaliation against black employees who sought or achieved ad

vancement or exercised rights protected by Title VII, we con

clude that the district court's finding of a pattern and prac

tice of retaliation is not clearly erroneous.

VII

In order to maintain a class action, the requirements of

Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 23 must be met. General

7. After this action was filed, Armour promoted a black

employee to supervisor and hired a black person as a

salesman.

33

Telephone Co. v. Falcon, 457 U.S. 147, 156 (1982); Stastny v.

Southern Bell Tel. & Tel. Co., 628 F. 2d 267 , 273 (4th Cir.

1980). In reviewing the final class certification, the appel

late court views the entire record to determine if the trial

court erred in its certification. Stastny, 628 F.2d at 276.

Armour claims that the class as certified fails to meet

the prerequisites of commonality, typicality, numerosity, and

adequacy of representation. The company further contends that

the district court erred in including victims of retaliation

and applicants, because they are inappropriate for class

treatment.

Preliminarily, we note that inclusion of "office and man

agement positions" in the certification comprises more jobs

than are justified by the evidence. While it is true that

sales jobs are included in office positions and supervisory

jobs may be considered management positions, the broad refer

ence to office and management positions encompasses jobs for

which no plaintiff or intervenor presented evidence of racial

ly discriminatory practices. To clarify the certification, it

must be amended to include only promotions into sales and su

pervisory positions.

Armour's contention that the district court erred in

certifying outside applicants for sales and supervisory posi

tions when the class representatives were employees who sought

promotions into these jobs presents a more difficult question.

In General Telephone Co. v. Falcon, 457 U.S. 147 , 157-58

(1982), the Supreme Court rejected the practice of across the

34

claims must beboard certification and held that the class

fairly encompassed within the representatives' claims. Falcon

noted that the commonality and typicality requirements of rule

23(a) might be satisfied if there were "[s]ignificant proof

that an employer operated under a general policy of discrimi

nation" and "the discrimination manifested itself in hiring

and promotion in the same general fashion, such as through en

tirely subjective decisionmaking processes." 457 U.S. at 159

n. 15.

Applying Falcon, the district court found that the stand

ards for selection to these positions are the same for incum

bent employees and outside applicants. At trial, Armour offi

cials testified that employees and outside applicants were re

quired to complete an application for employment and that em

ployees were given no preference over others. Also, entirely

subjective criteria were applied to employees and outside ap

plicants seeking sales or supervisory jobs.

The plaintiffs' claims regarding the promotion of black

employees into sales and supervisory jobs and class claims re

garding the hiring of black applicants into these jobs overlap

on many important issues of proof. We believe, however, that

there is a significant omission in the district court's find

ings. Applying Falcon, we are unable to affirm single class

treatment for both promotions and hiring claims because the

district court made no finding that the supervisors who made

the challenged promotions decisions were the same persons who

made hiring decisions. Consequently, there is no evidence

35

that the officials who selected outside applicants for the

sale and supervisory jobs were motivated by racial prejudice.

See Falcon, 457 U.S. 147 , 162 (Burger, C.J., concurring in

part, dissenting in part). ̂ Although the certification ques

tion is a close one, we conclude that the significant proof

for single class treatment required by Falcon is lacking in

this case, and thus the plaintiffs cannot adequately represent

the outside applicants for sales and supervisory positions.

Additionally, we note that the lack of identity of officials

who were responsible for hiring undercuts a finding that the

company engaged in a pattern and practice of racial discrimi

nation against outside applicants. See Lilly v. Harris-Teeter

Supermarket, 720 F.2d 326, 338 (4th Cir. 1983). This observa

tion, however, in no way affects the proof of a pattern and

practice of discrimination against incumbent employees who

sought a promotion into sales and supervisory positions.

In all other respects, we conclude that the record sup

ports the district court's determination of class action

status. The plaintiffs' pleadings and evidence are consistent

with a finding of commonality. Both class claims and individ

ual claims were established by a showing of intentional dis

crimination in promotions, bolstered by statistical evidence.

We cannot accept Armour's contention that harassment and

retaliation claims are not susceptible of class treatment be

cause they are too individualized. The plaintiffs established

a general practice of retaliation against employees who op

posed discriminatory practices or exercised rights protected

36

under Title VII, in violation of § 704(a). Despite the pres

ence of individual factual questions, the commonality criteri

on of rule 23 (a) is satisfied by the common questions of law

presented. In this case, the utility of the class action de

vice would be destroyed by requiring the plaintiffs to bring

separate claims of retaliation. See Int'l Woodworkers v.

Chesapeake Bay Plywood, 659 F.2d 1259, 1269-70 (4th Cir.

1981); 7 Wright and Miller, Federal Practice and Procedure

§ 1763 (1972 and Supp. 1983).

The complainants' claims are typical of the plant-wide

discriminatory practices they challenge. Drakeford and Harvey

were discriminatorily denied sales positions. Drakeford and

Edwards were discriminatorily denied supervisory positions.

gFinally, Holsey, Frazier, Drakeford, and Bennett were found

to have been victims of retaliation for exercising their

rights under Title VII. Thus, at least one representative is

a qualified member of the class of employees denied promotions

in sales and supervisory positions and subjected to

retaliation. See 7 Wright and. Miller, Federal

Practice and Procedure § 1761 at 586-87 (1972) . The

complainants alleged and established that they personally were

8. Armour asserts that. .Bennetts is not an adequate rep

resentative of the class because she had limited exposure

to Armour as a probationary employee for six months and

then was discharged. This reasoning would create the

anomalous result that an employer could eliminate a po

tential representative of employees merely by discharg

ing a complaining employee. We therefore reject this ar gument.

37

harmed by these practices. They meet the typicality criterion

of rule 23 (a) and the requirement for fair and adequate

9representation.

The final requirement for certification, numerosity, was

satisfied by the plaintiffs. The district court found that

Armour employed between 46 and 60 black employees annually

since 1971, and this large number of employees potentially af

fected by Armour's challenged practices made joinder imprac

ticable. Armour contests the figures used by the district

court, claiming that the relevant number is the total of all

supervisory and sales vacancies during the time period, which

is 34. Armour further contends that the more realistic figure

is 6 or 7, because of the 34 vacancies only 6 or 7 positions

might have been awarded to blacks if the availability data

used at trial applied.

We cannot accept this method of estimating the size of a

class for purposes of rule 23(a) (1). Contrary to Armour's as

sertion, this court's opinion in Kelley v. Norfolk & Western

Ry. , 584 F. 2d 34 (4th Cir. 1978), does not mandate Armour's

computation. Kelley involved complaints of a promotion system

at a facility where there were 67 black employees, all lived

in the same area, and the plaintiffs identified only 8 black

employees who qualified for promotion. In the instant case,

there were considerably more black employees who could have

been injured by the challenged practices, and their identity

9. Armour does not contend that plaintiffs' counsel

were inadequate representatives. Thus, this aspect of

rule 23(a)(4) is not at issue.

38

could not be established at the liability stage. Moreover,

Kelley establishes that there is no mechanical test for numer-

osity and the determination "turns on the nature of the claim

of discrimination asserted by the plaintiffs and the number of

persons who could have been injured by such discrimination."

584 F. 2d at 35. See generally 7 Wright & Miller, Federal

Practice and Procedure § 1762 at 602-03 (1972). The determi

nation of numerosity is a discretionary matter, and, finding

no abuse, we affirm the district court's decision. See

Cypress v. Newport News General & “Nonsectarian Hosp. Ass'n,

375 F.2d 648, 653 (4th Cir. 1967).

VIII

Armour objects to allowing Holsey and Frazier to estab

lish permanent seniority in the sausage department, and using

their date of hire as their departmental seniority date. It

also protests that the judgment contains unreasonably vague

injunctive relief, contrary to the requirements of Federal

Rule of Civil Procedure 65(a).

We conclude that retroactive seniority is the appropriate

remedy to be awarded to Holsey and Frazier. See Franks v.

Bowman Transp. Co., Inc., 424 U.S. 747, 762-70 (1976). The

record, however, does not support using their date of hire as

their departmental seniority date. Under the terms of the

collective bargaining contract, if Armour had allowed them to

bump into sausage, they would have had departmental seniority

dating from their transfer. The relief accorded Holsey and

Frazier should be modified to this extent.

39

The court has the duty to render a decree which will

eliminate racially discriminatory effects of the past and bar

such discrimination in the future. Albemarle Paper Co. v.

Moody, 422 U.S. 405, 418 (1975); Sledge v. J.P. Stevens & Co.,

Inc., 585 F. 2d 625, 643-44 (4tn Cir. 1978). The district

court properly fashioned injunctive relief to protect the

plaintiffs and class members from future discriminatory and

retaliatory acts like those established at trial. It drafted

the decree with sufficient specificity to give Armour fair

notice of the conduct that is being prohibited. We note, how

ever, that because the court's finding of classwide discrimi

nation against outside applicants lacks evidentiary support,

that portion of the judgment enjoining Armour from discrimi

nating in hiring is vacated.

IX

Because we have vacated part of the judgment, the dis

trict court must reconsider the award of attorneys' fees. We

therefore vacate the award and remand this issue for a deter

mination of the proper amount in accordance with Hensley v.

Eckerhart, 103 S. Ct. 1933 (1983), and Blum v. Stenson, 104

S. Ct. 1541 (1984) . The award should include a reasonable fee

for the appellants' attorneys on appeal with respect to those

issues on which the judgment has been affirmed. Because ap

pellants have substantially prevailed on appeal, they shall

recover their costs.

40