Johnson v Trucking Employers, Inc. Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1976

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Johnson v Trucking Employers, Inc. Brief for Appellants, 1976. c37d7220-b69a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/bd81aece-32f8-4422-9a00-3dcd09132611/johnson-v-trucking-employers-inc-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

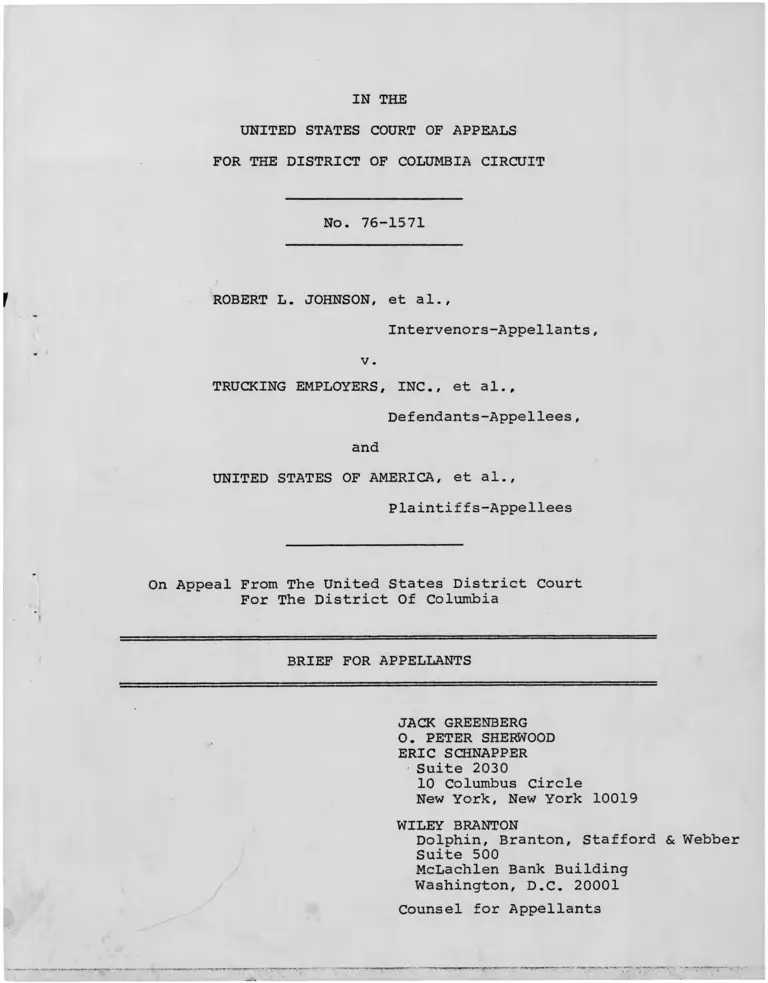

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT

No. 76-1571

ROBERT L. JOHNSON, et al.,

Intervenors-Appellants,

v .

TRUCKING EMPLOYERS, INC., et al.,

Defendants-Appellees,

and

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellees

On Appeal From The United States District Court

For The District Of Columbia

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

JACK GREENBERG

0. PETER SHERWOOD

ERIC SCHNAPPER

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

WILEY BRANTON

Dolphin, Branton, Stafford & Webber

Suite 500

McLachlen Bank Building

Washington, D.C. 20001

Counsel for Appellants

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT

No. 76-1571

ROBERT L. JOHNSON, et al.,

Intervenors-Appellants,

v .

TRUCKING EMPLOYERS, INC., et al.,

Defendants-Appellees,

and

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellees

Certificate Required By Rule 8(c)

of The General Rules of the United States Court of Appeals

For The District of Columbia Circuit

The undersigned, counsel of record for appellants,

certifies that the following listed parties have an interest

in the outcome of this case. These representations are made

in order that judges of this court may evaluate possible dis

qualification or recusal.

1. The Plaintiffs: United States of America;

Equal Employment Opportunity Commission.

2. The Defendant Unions: International Brotherhood

of Teamsters, Chauffeurs, Warehousemen and

Helpers of America; International Association

of Machinists and Aerospace Workers, AFL-CIO.

3. The Named Defendant Companies: Trucking Employers

Inc; Arkansas-Best Freight System, Inc;

Consolidated Freightways Corporation of

Delaware; I. H. L. Freight, Inc.; The Mason

and Dixon Lines, Inc.; Pacific Inter-Mountain

Express Co.; Smith's Transfer and Storage.

4. The Class of Defendant Companies: All common

carriers of general commodity freight by motor

vehicle which employ over-the-road drivers,

and which are parties to or are bound by the

National Master Freight Agreement and area

supplements thereto, !which, as of December 21,

1972, employed at least 100 persons and which

had annual gross revenues of at least $1,000,000.

This class includes over 300 companies.

5. The named intervenors: Robert L. Johnson, Patrick

Hairston, George Scott, Johnny Lee, Naran Buchanan,

Clifton Wiggins, Oscar Newsome and Richard Sagers.

6. All black and Spanish-surnamed workers who on March 20,

1974, were employed by, or on layoff from, a de

fendant employer, and who were hired prior to

December 31, 1972.

-2-

Eric Schnapper

Attorney of Record for Appellants

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT

No. 76-1571

ROBERT L. JOHNSON, et al.,

Intervenors-Appellants,

v .

TRUCKING EMPLOYERS, INC., et al.,

Defendants-Appellees,

and

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellees

On Appeal From The United States District Court

For The District Of Columbia

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

QUESTION PRESENTED

Did the District Court err in authorizing the

defendant trucking companies to solicit from minority

employees waivers of certain rights under Title VII of

the 1964 Civil Rights Act?

This case was not previously before this Court.

There is now pending before the Court a related

appeal arising out of the same proceedings in the District

Court. Jones v. Trucking Employers, Inc., No. 76-1577.

REFERENCES TO PARTIES AND RULINGS

There are four orders below involving approval of

use of the disputed waivers, all entered by the Hon. William

L. Bryant. The first, on March 20, 1974, approved the Consent

Decree proposed by the original parties. The second, on

February 14, 1975, permitted intervention, and held that the

proposed waivers were not per se illegal. The third, on

January 19, 1976, clarified the basis of the two earlier orders.

The fourth, on March 18, 1976, approved, subject to certain

modifications, the form of the proposed notice and waiver.

In addition to the plaintiff named in the caption,

the Equal Employment Opportunity Commission is a plaintiff.

In addition to the named defendant, there are two defendant

1/

unions, and a class of over 300 defendant companies, seven

J jof whom are specifically named as class representatives.

1 / International Brotherhood of Teamsters, Chauffeurs,

Warehousemen and Helpers of America and the International

Association of Machinists and Aerospace Workers, AFL-CIO.

2/ Arkansas-Best Freight System, Inc.; Consolidated

Freightways Corporation of Delaware I„ H. L. Freight, Inc.;

The Mason and Dixon Lines, Inc.; Pacific Inter-Mountain

Express Co.; Smith's Transfer and Storage.

-2-

The named intervenors, other than Robert L. Johnson, are

Patrick Hairston, George Scott, Johnny Lee, Naran Buchanan,

Clifton Wiggins, Oscar Newsome and Richard Sagers.

STATUTES INVOLVED

Section 706(f)(1) of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(f)(1) provides in pertinent part:

If within thirty days after a charge

is filed with the Commission or within

thirty days after expiration of any period

of reference under subsection (c) or (d),

the Commission has been unable to secure

from the respondent a conciliation agree

ment acceptable to the Commission, the

Commission may bring a civil action against

any respondent not a government, governmental

agency, or political subdivision named in

the charge. In the case of a respondent

which is a government, governmental agency,

or political subdivision, the the Commission

has been unable to secure from the respondent

a conciliation agreement acceptable to the

Commission, the Commission shall take no

further action and shall refer the case to

the Attorney General who may bring a civil

action against such respondent in the appro

priate United States district court. The

person or persons aggrieved shall have the

right to intervene in a civil action brought

by the Commission or the Attorney General in

a case involving a government, governmental

agency, or political subdivision. If a

charge filed with the Commission pursuant to

subsection (b) is dismissed by the Commission,

or if within one hundred and eighty days from

the filing of such charge or the expiration of

any period of reference under subsection (e)

or (d), whichever is later, the Commission

has not filed a civil action under this section

or the Attorney General has not notified a

civil action in a case involving a government,

governmental agency, or political subdivision,

or the Commission has not entered into a con

ciliation agreement to which the person ag

grieved is a party, the Commission, or the

Attorney General in a case involving a govern

ment, governmental agency, or political sub

division, shall so notify the person aggrieved

and within ninety days after the giving of such

-3-

notice a civil action may be brought against

the respondent named in the charge (A) by

the person claiming to be aggrieved, or (B)

if such charge was filed by a member of the

Commission, by any person whom the charge

alleges was aggrieved by the alleged unlawful

employment practice.

Section 707(a) of the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-6(a), provides:

Whenever the Attorney General has reasonable

cause to believe that any person or group

of persons is engaged in a pattern or prac

tice of resistance to the full enjoyment of

any of the rights secured by this title, and

that the pattern or practice is of such a

nature and is intended to deny the full exercise

of the rights herein described, the Attorney

General may bring a civil action in the appro

priate district court of the United States by

filing with it a complaint (1) signed by him

(or in his absence the Acting Attorney

General), (2) setting forth facts pertaining

to such pattern or practice, and (3) requesting

such relief, including an application for a

permanent or temporary injunction, restraining

order or other order against the person or

persons responsible for such pattern or prac

tice, as he deems necessary to insure the full

enjoyment of the rights herein described.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

_2/

On March 20, 1974, the United States of America

commenced this action under Title VII of the 1964 Civil Act

against two unions and a class of over 300 defendant trucking

companies. The 20 page complaint alleged that the defendants

had engaged in systematic discrimination against black and

Spanish-surnamed employees and applicants. Seven of the

companies were named as class representatives. Trucking Employers

Inc. represents most of the companies for collective bargaining

4.Jpurposes. Simultaneous with the filing of the government s

3_/ The authority of the Department of Justice to commence such

an action under Title VII expired 4 days later. The E.E.O.C.

was subsequently added as a plaintiff.

d / Complaint, App.

complaint, each of the named defendant companies filed

answers, and the government and named companies filed a

45 page "Partial Consent Decree With Respect to Defendant

Employees.” On the same day that all these documents

were filed the District Judge to whom the case was assigned

summarily approved the "partial" consent decree. The

decree contemplated that the defendant companies would

thereafter solicit from their minority employees a waiver

of certain rights under Title VII in return for a cash

J.Jpayment ranging from $150 to $1500. It is this proposed

solicitation of waivers which gave rise to the instant

round of litigation.

Though not disclosed by any of the papers then

filed with the District Court, there were already pending

on March 20, 1974, in other federal courts, more than a

dozen private class actions against the defendant companies.

On August 26, 1974, counsel for the plaintiffs in several

of those actions wrote to the District Judge in this case

expressing concern that, pursuant to the consent decree,

"some of the defendants will attempt to contact directly,

AJ

2J

App.

Consent Decree, p. 45; App.

pp. 32-37; App.Consent Decree,

-5-

and without prior permission from us, any of the clients

whom we represent in pending litigation." Counsel expressed

the view that the proposed waivers were unlawful, and sought

a conference to clarify whether intervention might be neces-

sary to protect the rights of his clients. On September 10,

1974, the government and six of the named companies filed

a lengthy "Stipulation" setting forth the procedures they

intended to follow, and the contents of the notices and

release to be used, in soliciting the waivers. Apparently

the signatories did not contemplate that the District Court

had any role to play with regard to the proposals since

they neither submitted nor requested an order approving

9_/them. Shortly thereafter counsel for the private plaintiffs

advised the District Court and original parties that inter

vention would be sought; on or about September 26, 1974,

the companies assured the Court that no attempt would be

made to solicit the waivers pending further order of the

Court.

On September 30, 1974, appellant Robert Johnson

and 8 other individuals moved to intervene in the instant

case. Each cf the named intervenors was also the named

a

plaintiff in/pending separate private Title VII action

10/

before another federal court. The request for intervention

was accompanied by a motion for disapproval of the notices,

8 / Letter of April 26, 1974, from Eric Schnapper to the

Hon. William Bryant; App.

_9/ App.

10/ App. While this case was still pending in the

District Court the intervention of Willie Johnson was dis

missed by agreement of the parties because the action in

which he was the plaintiff had been settled.

- 6-

forms and release which were the subject of the September 10,

11/

1974, stipulation. The intervenors urged that the waivers

were unlawful per se, and that the proposed notices did not

contain sufficient information to enable an employee to

make a knowing and intelligent decision whether to waive

his or her rights. Shortly thereafter a second motion to

intervene, and to disapprove, was filed by another group

of private plaintiffs including Leon Jones; that interven

tion is the subject of another appeal now before this Court,

No. 76-1577. The motions of both groups of intervenors

were argued at a hearing on October 10, 1974.

On February 14, 1975, the District Court granted

12/appellants'motion to intervene. The Court also held that

the proposed waivers were not unlawful per se, but invited

the intervenors to make specific suggestions as to changes

in the proposed notices, etc., that would assist employees

in making a knowing and intelligent decision whether to

13/

execute the waivers. On March 28, 1975, intervenors

moved to modify the proposed notices, etc., in seven specified

_14/

ways. A hearing on this motion was held on August 8, 1975.

On January 21, 1976, the District Court approved most of

the modifications sought by intervenors. With the agreement

11/ App.

12/ App.

13J App.

14 / App.

-7-

of all parties that order was modified on March 18, 1976,

15/to avoid certain technical problems.

On September 17, 1975, intervenors moved for an

order clarifying the decision of February 14, 1975, to

delineate the extent, if any, to which the District Court

had ruled on the adequacy of the money being offered in

lfi/return for the proposed waiver. On January 19, 1976, the

District Court resolved this motion by explaining that it

had not decided any questions regarding the amount of

the money offer other than that it was not "a mere pittance".

A timely notice of appeal was filed on May 8,

_LS/

1976.

11/

STATEMENT OF THE FACTS

Although the complaint alleges, and the partial

consent decree proscribes, a variety of forms of discrimina

tion, the central concern of both and of this appeal is

the exclusion of black and Spanish-surnamed employees from

jobs as "road drivers." Road drivers drive trucks that

travel between major cities or depots; the pick-up and

delivery of goods within a given local area is done by

"city drivers." The two types of driver jobs differ in

the hours and distance involved, and, most importantly,

the rate of pay.

15/ App.

16/ App.

17/ App.

18/ See 28 U.S.C. § 2107.

-8-

Blacks and other minorities have traditionally

been excluded from jobs as road drivers, and confined

instead to less well paid jobs within a given city, includ

ing city driver. In 1971 blacks were only 1 to 2.7% of

the road drivers at major trucking companies, but accounted

for 6.9% of the city drivers. Spanish-surnamed workers

were only 0.8% of the road drivers, but 3.4% of the city

19/

drivers. The complaint in this action alleged that the

named defendants had a similarly low portion of minority

road drivers, though there were large numbers of non-whites

in other less lucrative positions.

2 0/

Employment Patterns

Total Minority Minority Minority

Road Road City Shop

Company

Arkansas Best-

Drivers Drivers Workers Workers

Freight

Branch Motor

676 2 7 (4%) 190 21

Exp.

Consolidated

683 13 (2%) 106

Freightways 2,767 92(3.3%) 364 74

I.M.L. Freight

Mason & Dixon

343 8(2.3%) 97 13

Lines 997 28(2.8%) 94 10

Pacific I.M.E. 1,747 54(3.0%) 222 41

Smiths Transfer 931 43(4.6%) 140 2

of these companies hired

21/

no minority road drivers at

prior to 1968. Nationally blacks and Spanish- surnamed

22/

Americans are 16.6% of all truck drivers and deliverymen.

19/ Nelson, Equal Employment Opportunity In Trucking: An Industry

at the Crossroads, E.E.O.C. Contract EE072001, App.

20/ Complaint, pp. 2-6; App.

21/ Id.

22/ united States Census, 1970, Detailed Characteristics,

V. 1, Table 227. App. There were 2,026,088 truck drivers

and deliverymen, of whom 245,966 were black and 90,766 Spanish-

surnamed .

-9-

The exclusion of minorities from road driver

jobs is of critical importance because they are among the

best paid in the industry. As the United States Commission

on Civil Rights reported earlier this year,

Road driving is one of the highest-

paying, blue-collar occupations in the

trucking industry. The average annual

earnings of road drivers employed by

large common carriers of general freight

were estimated to be $15,800 in 1972.

There is also a high degree of discrimina

tion against minorities in road driving. 23/

The difference in the annual wages paid to city and road

drivers is very substantial.

Average Compensation: 24 /

Road and City Drivers: 1966-1972

Year Road Drivers City Drivers Difference

1972 $15,913 $12,883 $3,030

1970 12,686 9,923 2,763

1961 12,123 9,412 2,711

1968 11,548 9,027 2,521

1967 10,610 8,444 2,166

1966 10,401 8,157 2,244

Blacks confined to other positions, such as mechanic or

platform worker, earn even less than city drivers.

Under the procedure proposed by the signatories

to the partial consent decree minority employees are to be

offered a specified sum of money if they will execute a

23/ The Challenge Ahead, Equal Opportunity In Referral

Unions, p. 95 (1976).

24/ Interstate Commerce Commission, Transportation Statistics

in the United States, 1966-1972; App. . This covers all

Class I common carriers of general freight engaged in intercity

service, a group roughly co-extensive with the defendant class.

-10-

these rights will receive at once $150 if he was hired

between January 1, 1971 and December 31, 1972, $300 if

hired between January 1, 1969 and December 31, 1970,

_25/

and $500 if hired before January 1, 1969. In addition,

if the employee later succeeds in transferring into a

road driver job, he will receive an additional $300, $600,

and $1,000 respectively. Because there are relatively few

road driver vacancies at this time, and because, as will

be seen, the government is still in the process of litigat

ing injunctive relief necessary to permit such transfer,

it is not now possible for most minority employees to

transfer to road driver jobs. A black driver hired as a

city driver in 1971 who transfers to a road driver job in

1978 will thus have lost $20,000; in return for waiving

this claim the employee would receive a total of $450.

In addition,minority workers who have already transferred

to road driver jobs will be asked to sign waivers in return

for a cash payment. The payment will be $150 for persons

hired between January 1, 1971 and December 31, 1972, $450

for persons hired between January 1, 1969 and December 31,

26/

1970, and $750 if hired before January 1, 1969.

waiver of their Title VII rights. An employee who waives

Partial Consent Decree, pp. 34-35; App.

Partial Consent Decree, pp. 37-38; App.

2 57

26/

-11-

In fully litigated Title VII cases against trucking

companies who have engaged in such discriminatory exclusion

of non-whites from road driver jobs, the injunctive relief

required by the federal courts has traditionally included

(a) invalidating any rules forbidding employees in other

positions to transfer to road driver jobs, and (b) directing

that minority employees who transfer to road driver jobs not

lose all the seniority rights they enjoyed before the transfer.

See Bing v. Roadway Express, 444 F.2d 686 (5th Cir. 1971).

An employee's seniority date is of great importance in trucking,

as other industries, controlling his or her liability to lay

offs and, in some jobs, his or her annual income. An employee

with 5 or 10 years seniority as a city driver would in most

cases be foolhardy to give up that job to work as a road

driver with no seniority; an inability to carry over seniority

tends to lock a black employee into a city driver job as

effectively as ana/ert no transfer rule. The consent decree

in this case is avowedly "partial" because it only resolves

the first problem. Although the companies were willing to

abandon their no transfer rules, the government was unable

to reach agreement with the union as to the seniority rights

for transferees. The seniority issue must thus be resolved

by a trial on the merits in this case. Pending the resolution

of that trial it is unknowable whether blacks hired into city

driver and other jobs in past years will, as a practical matter,

be able to transfer to road driver jobs.

-12-

ARGUMENT

The waiver which minority employees must execute

as a condition of receiving the compensation described

above releases the company

its officers, directors, agents, servants,

employees, successors or assigns, from any

and all claims for monetary compensation

on account of or arising out of any alleged

discrimination based on race or national

origin in violation of any federal equal

employment opportunity laws, ordinances,

regulations, or orders, including, but not

limited to Title VII of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964, as amended, 42 U.S.C. §2000 (e),

et seq., the Civil Rights Act of 1866, 42

U.S.C. § 1981, et seq., or the United States

Constitution, which may have occurred prior

to March 20, 1974.

It is important to note at the outset what this waiver does

not include. An employee who executes the release retains

unimpaired his or her rights to sue for (a) monetary or

injunctive relief for violations of law occurring after

March 20, 1974, (b) monetary or injunctive relief to remedy

violations of the partial consent decree or any other order

entered in this action, (c) injunctive relief for violations

of law occurring before March 20, 1974, (d) monetary relief

against the company for losses sustained after March 20,

1974 because of its continued use of practices or procedures

which have the effect of perpetuating the effect of earlier

27/

discrimination, and (e) monetary relief against his or her

union for violations of law occurring prior to March 20,

1974. It is clear, though not dispositive if this particular

case, that a waiver which included a release of (a)-(d)would

be prospective in nature and thus void as contrary to public

policy. Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co.. 415 U.S. 36 (1974).

Also undisputed is that the consent decree does not bind

any employee as a matter of res judicata. Williamson v.

Bethlehem Steel Corp.. 468 F.2d 1201 (2d Cir. 1972), cert,

denied 411 U.S. 911 (1973), that the rights and remedies of

an employee who does not execute a release are in no way

impaired or affected by thr release, and that the rights

of an employee who does execute the release are affected

only to the extent specified in the release itself.

Appellants maintain that the District Court applied

the wrong standard in approving the use of this waiver, and

that the waiver is invalid per se.

I. THE DISTRICT COURT APPLIED THE WRONG

STANDARD IN APPROVING THE DISPUTED

WAIVERS_______________________________

This case presents a novel and important question

regarding the role of federal courts in approving and administer

ing consent decrees. For over half a century, particularly

in the area of anti-trust, the United States has been entering

into, and seeking judicial approval of, consent decrees. In

the last two decades it has become increasingly common for

the government to settle a case before it is ever filed,

formally commencing the action for the sole purpose of embody

ing the settlement in a consent decree. The judicial role in

approving these decrees has long been nominal at best; con

fronted by legal documents of great length and complexity,

and without any significant knowledge of the underlying facts,

27/ cont'd

waiver. Motion for Disapproval of Proposed Notices, etc., p. 2.

The government subsequently made clear that the release did not

"waive monetary claims accruing subsequent to entry of the decree.

Response of Plaintiffs To Motion For Leave To intervene and to

Set Aside The Decree and Notices, p. 27.

-14-

the courts have routinely lent their authority to the decrees.

Commonly the decree is approved on the same day it is submitted

with no proceedings other than a brief conference in chambers

with counsel for the parties. The procedure, measured by

normal standard, is neither adversary in nature nor informed;

from the perspective of any interested person other than a

signatory it is also ex parte. We are unaware of any instance

in which a federal judge refused to approve, or modify sub

stantially, a consent decree submitted in this matter.

Judicial acquiescence in this nominal role is

based in large measure on the fact that the consent decree

binds no one but the parties thereto. Interested private

parties enjoy whatever benefits the government decree

contained, and are free to sue for more. If the government

makes a poor, counter-productive, or eve sweetheart deal, it

normally has no effect on any other party — except, of course,

in the sense that the defendant may continue to break the law.

In the last two years, however, the government in settling

cases under Title VII of the 1964 Civil Rights Act has used a device

which sets those consent decrees apart from those with which

the courts have heretofore been familiar. The government

decrees, as in this case, have begun to require that minority

employees, as a condition of receiving some or all of the

relief provided by those decrees, must waive to a substantial

degree their rights under Title VII and other statutes.

The government has justified this device by urging

that it does no more than give minority employees an option

to accept the government negotiated relief in return for a

-15-

waiver, without impairing their option to sue individually.

While legally correct, this contention is somewhat unrealistic.

The average employee, without the aid of counsel, unable to

hire an attorney to commence an action, and hard pressed

for funds, is unlikely to turn down a check or job offer

that comes to him or her under the imprimatur of the United

States government and a United States District Judge. Actual

experience under the two major national consent decrees con

taining such conditional offers cf relief makes clear that all

but a handful of affected employees can be expected to accept

these offers and execute the proffered releases.

Because of this a District Court asked to approve

a consent decree procedure involving such a waiver has a

fiduciary responsibility to scrutinize the adequacy of the

relief for which the waiver is exchanged prior to giving such

approval. That responsibility is closely analogous to the

duty of a court under Rule 23 (e) , Federal Rules of Civil

Procedure, in scrutinizing a proposed settlement of a class

action. In passing on a Rule 23(e) settlement a court is

obligated to consider a variety of factual questions, particu

larly "the range of reasonableness of the settlement fund to

a possible recovery in light of all the attendant risks of

litigation." City of Detroit v. Grinnell Corp., 495 F.2d 448,

463 (2d Cir. 1974). This resolution will normally require

the presentation of substantial evidence regarding the nature

and magnitude of the underlying claim, unearthed in appropriate

-16-

cases by discovery. Girsh v. Jepson, 521 F.2d 153, 157 (3d

Cir. 1975). A similar approach should be taken by a court

which is asked to approve the solicitation of waivers from

large numbers of victims of discrimination.

The initial procedure followed by the District

Court in this case, however, was the pro forma role properly

restricted to traditional consent decrees not entailing a

solicitation of waivers. On the same day that the parties

filed a lengthy complaint, 7 answers, and a lengthy consent

decree, the District Judge approved the decree. There was

in the few hours involved barely time to read the documents,

no time to study them in detail, and no opportunity to learn

anything about the underlying facts. The District Court,when

it approved the decree, necessarily knew nothing about the

average wage differential between city and road drivers, the

likelihood of road driver vacancies in the proximate future,

or the importance, not to mention the outcome, of the still

outstanding dispute as to seniority relief. Some 22 months

later the District Court explained that it had approved the

use of the waivers because the amount of money involved was

not "a mere pittance." Regrettably the phrase "mere pittance"

is not one of established legal significance; there is, however,

no reason to believe that these words denote the outcome of the

careful factual inquiry which is appropriate in a case such as

this and which admittedly did not occur.

28/ Historically a pittance was a gift or bequest to a religious

house or order to provide anniversary masses for one deceased,

and extra allowances of food or drink for the occasion. It later

-17-

Regardless of the standard applied, theDistrict

Court could not properly have approved the waiver procedure

on the present record. The evidence before the District

Judge revealed that a black assigned because of his race as

a city driver rather than a road driver, received an average

of $3,000 a year less inv\ages. See p. 10, supra. The com

pensation procedure offered roughly $50 a year now, and an

additional $100 a year when and if the employee was able to

transfer into a road driver job. This is approximately 1.6/

on the dollar now, and another 3.3/ on the dollar in the

event of a transfer. Because of the seniority problem

minority employees do not yetbave a realistic chance of

transferring; whether, because of that issue, and the rate

of vacancies, many employees would ever receive more than

the initial 1.6/ was unknown to the District Court. Whatever

the standard of reasonableness by which government sponsored

settlements are to be measured, surely the amount involved

in this case is so small as to approach in significance the

proverbial peppercorn.

In approving the waiver, the District Court compared

this case to United States v. Allegheny-Ludlum Industries, 517

F.2d 826 (5th Cir. 1975), asserting that it had considered "the

average compensation to which each employee will become entitled

28/ cont'd.

came to mean the individual portion of food or drink so allowed.

The secondary meaning of the term, now more common, is a charity

gift or dole especially if food. Webster's Unabridged Inter

national Dictionary offers as a tertiary meaning "a portion or

dole," specifically "a. A small allowance of food. b. A very

small amount of money." The District Court presumably used the

phrase "mere pittance" in this last sense, but how much money

is more than "a mere very small amount of money" is not abundantly

clear.

-18-

. . . in the context of the overall provisions of the

Consent Decree". This case is clearly distinguishable

from Allegheny-Ludlum. First, the District Court had no

way of knowing what the "average award would be, since it

could not foresee whether employees would ever get more

than the initial 1.6/ on the dollar, or the number of

workers hired after 1969 and 1971. Second, the Court

could not assess the money in the context of the injunctive

relief, assuming arguendo that would be relevant, because

the most important element of the ultimate injunctive

relief — seniority reform — was and is unknown. Third,

the District Judge in appraising the reasonableness of the

offer could not rely on any particular expertise in the

problems of discrimination in the trucking industry, whereas

the judge in Allegheny-Ludlum had just such expertise re

garding the steel industry.

While disapproval of the waiver procedure would

be required on the present record, we think the original

parties are entitled to an opportunity to offer evidence

in support thereof. The signatories to the decree offered

no evidence whatever when they first sought judicial ap

proval of the decree, or later in response to the motion

to disapprove the waiver. Inasmuch as that failure may

have been grounded in a mistaken belief that the District

Court was required to approve the waiver procedure regardless

of the facts, the original parties should be allowed on remand to

present testimony or documentary evidence in support of a re

newal request for such approval.

29/ Memorandum of January 19, 1976.

-19-

II. THE WAIVERS ARE INVALID PER SE

Even if these waivers could be signed by minority

workers under circumstances rendering them knowing and

voluntary, that would be 'insufficient to assure their validity.

A waiver, like any contract, must be invalidated despite

the consent of the parties if it contravenes public policy.

As the Supreme Court pointed out in Brooklyn Savings Bank v.

O'Neil, 324 U.S. 697 (1945),

It has been held in this and other courts

that a statutory right conferred on a private

party, but affecting the public interest, may

not be waived or released if such waiver or

release contravenes the statutory policy.

Mid-State Horticultural Co. v. Pennsylvania R .

Co., 320 U.S. 356, 361; A.J. Phillips Co. v.

Grant Truck Western R. Co., 236 U.S. 662, 667,

Cf. Young v. Higbee Co., 324 U.S. 204, ante,

890. Where a private right is granted in the

public interest to effectuate legislative policy

waivers of a right so charged or colored with

the public interest will not be allowed where

it would thwart the legislative policy it was

designed to effectuate.

324 U.S. 704-706.

The federal courts have repeatedly invalidated

waivers which purported to limit the rights or remedies

under Title VII. In Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Company,

415 U.S. 36 (1974), the minority employee, claiming

that he had been fired because of his race, voluntarily

submitted his claim for arbitration under the collective

bargaining agreement in force at his plant. The agreement

provided that, where arbitration was sought, the decision

-20-

of the arbitrator would be binding on the employee. After

the arbitrator ruled against him, the employee filed a

complaint with the E.E.O.C. and thereafter brought suit in -

federal court. The Supreme Court held invalid any agreement

by an employee establishing arbitration, rather than the

federal courts, as the forum in which his claims would be

finally adjudicated. 39 L.Ed. 2d at 147. In Chastang v. Flynn

and Emrich Company, 365 F.Supp. 957 (D.Md. 1973),the plaintiff

employees had on several occasions execuited releases waiving

any right to sue arising in connection with their employment.

The District Court held the releases invalid

F & E argues that the re-execution of the

documents after the effective date of

Title VII prevents plaintiffs from relying

upon Title VII to sue the company since they

were aware of the Act at the time they re-

executed the releases. The simple answer to

this is that the parties cannot agree to per

form an illegal act. United Mine Workers v.

Pennington, 381 U.S. 657 . . . (1965); United

Brotherhood of Carpenters and Joiners of

America v. United States, 330 U.S. 395,

(1947) A statutory right conferred upon a

private party, but affecting the public

interest may not be waived or released, if

such waiver or release contravenes public

policy. Brooklyn Savings Bank v. O'Neil,

324 U.S. 697, 704 ... (1945).

365 F. Supp. at 968. In Rosen v. Public Service Electrical

and Gas Company, 328 F.Supp. 454 (D.N.J. 1970), the employer

argued that any discrimination in its pension plans had been

waived when the employees, through their union, agreed to

that plan through collective bargaining. The court held that

any such contractual agreement to the plan was unenforceable.

-21-

328 F.Supp. at 464. The Fourth Circuit rejected a similar

argument in Robinson v. Lorillard Corporation, 444 F.2d 791,

799 (4th Cir. 1971): "The rights assured by Title VII are

not rights which can be bargained away — either by union, by

an employer, or by both acting in concert." In Moss v. Lane

Company, 50 F.R.D. 122 (W.D. Va. 1970), the plaintiff sued

on behalf of himself and his fellow minority employees. The

employer thereafter served affidavits from all other minority

employees disclaiming any authority from them to commence the

suit. The court refused to dismiss the class action aspect

of the case despite these waivers.

By such dismissal, I would be saying that

either there is no racial discrimination

practiced by the defendant against the other

members of the class or that the other Negro

employees want to be racially discriminated

against. Clearly the latter is unacceptable,

and, certainly, the former would be an improper

determination at this stage of the suit.

50 F.R.D. at 126.

(1) In enacting the Civil Rights Act of 1964 Congress

indicated a general intent to accord parallel or overlapping

remedies against discrimination. Alexander v. Gardner-

Denver Company, 415 U.S. 36, 47-49 (1964). Among

the multiplicity of independent remedies established by

law are (1) private litigation under Title VII, 42 U.S.C.

§2000e-5(f); (2) investigation by the EEOC, followed by

conciliation efforts if the agency finds there is probable

cause to conclude there is discrimination, 42 U.S.C. §2000e-5(b)

(3) "pattern or practice" suits by the United States, originally

-22-

prosecuted by the Department of Justice and now handled

by the EEOC; (4) enforcement of Executive Order 11246 and

42 C.F.R. Chapter 60 by the Office of Federal Contract

Compliance and the Secretary of Labor. In enacting Title

VII in 1964 Congress expressly rejected an amendment which

would have made Title VII the exclusive federal remedy for

most employment discrimination. 110 Cong. Rec. 13650-52 (1964)

Senator Clark, one of the sponsors of the 1964 Act, stressed

that Title VII "is not intended to and does not deny to any

individual rights and remedies which he may pursue under other

federal and state statutes" 110 Cong. Rec. 7207 (1964).

Despite this clear legislative history, employers urged

repeatedly but unsuccessfully in the years after the enactment

of Title VII that the consideration of a charge of discrimina

tion in one forum precluded consideration of the same charges

in another. See United States v. Operating Engineers, Local 3,

4 EPD 57944 (N.D. Cal. 1972); Williamson v. Bethlehem Steel

Corporation, 468 F.2d 1201 (2d Cir. 1972), cert. denied 411

U.S. 911 (1973); Leisner v. New York Telephone Company, 358

F.Supp. 359 (S.D.N.Y. 1973). The federal courts have rejected

a variety of other attempts to curtail the independence of these

overlapping remedies. In Boles v. Union Camp Corp., 5 EPD

58051 (S.D. Ga. 1972), the company unsuccessfully contended

that it was not subject to suit under Title VII because its

seniority practices had been developed under the supervision

and with the approval of the Office of Federal Contract

Compliance. The Fifth Circuit rejected a similar defense

-23-

of O.F.C.C. approval in Pettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe

Company, 494 F.2d 211, 221, n.21 (5th Cir. 1974). In

E.E.O.C. v. Eagle Iron Works, 367 F.Supp 817, (S.D. Iowa

1973), the court held that the Commission could maintain a suit

regarding charges which had already been the subject of an

unsuccessful private Title VTI action. 367 F.Supp. at 821.

Three circuits have rejected the contention that adjudication

of a charge of discrimination under the national labor laws

precludes litigation regarding the same alleged discrimination

under Title VII. Taylor v. Armo Steel Corporation, 429 F.2d

498 (5th Cir. 1970); Tipler v. E.I. du Pont Co., 432 F.2d 125

(6th Cir. 1971); Norman v. Missouri Pacific Railroad, 414 F.2

73 (8th Cir. 1969). The Supreme Court has repeatedly rejected

the argument that a finding by the EEOC of no probable cause

precludes an employee from litigating the merits of the same

charge in federal court. McDonald Douglas Corp. v. Green,

411 U.S. 792, 798 (1973); Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Company,

39 L.Ed. 2d 147, 157 (1954); see also Robinson v. Lorillard

Corp., 444 F .2d 791 (4th Cir. 1971); Beverly v. Lone Star

Lead Const. Corp., 437 F.2d 1136 (5th Cir. 1971). As the

Supreme Court indicated in Alexander, the general rule in

employment discrimination litigation is that "submission of

a claim to one forum does not preclude a later submission to

another," 39 L.Ed. at 158. Within the last several years

Congress has rejected repeated efforts to limit this structure

-24-

of independent remedies.

Although Congress clearly intended to afford

minority employees relief in both private and government

litigation, the intent and effect of the proposed waiver

is to force each employee afforded back pay to choose

between those remedies. If an employee wants back pay

relief under the government action , he must relinquish in part

his statutory right to bring a private action. If an

employee wants to preserve the right to pursue private litiga

tion, he must relinquish his right to back pay relief under

the government action. The result is essentially that

rejected by Congress in 1970-72, to make either government

litigation or private litigation the exclusive remedy available.

In Hutchins v. United States Industries, Inc., 428 F.2d 303

(5th Cir. 1970), the employer argued that an aggrieved employee

was or could be required to chose between his remedy under

Title VII and his union grievance procedure. The Fifth

Circuit rejected that argument:

If the doctrine of election or remedies is

applicable to all Title VII cases, it applies

only to the extent that the plaintiff is not

entitled to duplicate relief in the private

and public forums which would result in an

unjust enrichment or windfall to him.

428 F .2d at 314. In Alexander v. Gardner-Denver, the Supreme

Court noted that the doctrine of election of remedies was

30/

30/ Hearings before a Subcommittee of the House Committee

on Education and Labor, 91st Cong., 2d Sess., pp. 36-37

(1969-70); Hearings before a Subcommittee of the Senate

Committee on Labor and Public Welfare, 92nd Cong., 1st Sess.,

p.63 (1971).

-25-

inapplicable to suits under Title VII, since it "refers to

situations where an individual pursues remedies that are

legally or factually inconsistent." At least 4 other circuits

have refused to apply the doctrine of election of remedies

to Title VII actions. See Bowe v. Colgate-Palmolive Co.,

416 F.2d 711, 714-715 (7th Cir. 1969); Voutsis v. Union

Carbide Corp., 452 F.2d 889, 893-894 (2d Cir. 1971), cert.

denied 406 U.S. 918; Newman v. Avco Corp., 451 F.2d 743, 746,

n.l (6th Cir. 1971) ; Qubichon v. North American Rockwell

Corp., 482 F .2d 569, 572-573 (9th Cir. 1973).

(2) The rights waived by a release must be the same

rights which were the subject of the compromise resulting

in the offer of compensation. Thus, if in an ordinary

Title VII race case the parties agreed to a monetary settle

ment based on the probable or alleged size of the class mem

bers claims for racial discrimination, the release employed

could not also include waivers of the employees' rights for

violation of the minimum wage laws, for physical injuries

giving rise to workmen's compensation, or for discrimination

on the basis of sex or age. The inclusion of such an extran

eous element in the release would be unlawful both because

there would be no consideration for this additional forfeiture,

and because the agreed upon amount would no longer bear a

reasonable relationship to the rights being waived.

The instant waiver suffers from such a defect.

The underlying monetary compromise is obviously of claims

of minority employees who were unlawfully prevented from

becoming road drivers. The notice to employees begins

-26-

"The purpose of this notice is to

inform you of your opportunity to trans

fer to an over-the-road job and, in addition,

to offer you an opportunity to receive mone

tary compensation . . . . 31/

The money is offered to employees who work at locations

32/

where road drivers were or are domiciled, and to minority

road drivers. To get one-third of the total applicable

amount the employees must state an interest in transferring

to a road driver job by placing their names on the Road

Driver Transfer List and meet the road driver qualifications

required by DOT regulations. To obtain the remaining two-

thirds the employee must actually transfer to a road driver

33/

job. The amount of the offer is a function of the number

of years when the employee was unable to transfer to a road

driver job, approximately $150 a year for subsequent trans

ferees. Minority employees who already hold road driver

jobs get between 1/3 and h of the sum paid to employees who

were only able to transfer after entry of the partial consent

decree.

While the underlying proposal is thus a compromise

negotiated by the government of claims based on discriminatory

denial of road driver jobs, the release is far more broad.

34/

The employee is required to waive all his accrued monetary

31/ Notice of Monetary Compensation Procedure, p. 1* App.

32/ Id.

33/ Id., p. 2.

34/ As of March 20, 1974.

-27-

claims for unlawful discrimination on the basis of race or

national origin. The complaint itself alleges that the

defendants have engaged in other forms of discrimination

unlawfully exclusing blacks and Spanish-surnamed Americans

from jobs as "apprentice mechanic and mechanic, office and

clerical and supervisor." The partial consent decree is

directed at yet other types of illegal conduct, including

discrimination in promotion, demotion, training and dismissal,

and use of discriminatory standards which are not job-related.

Not only is the compromise underlying the waiver totally

unrelated to these types of discrimination, but the procedures

for obtaining the full amount tendered are obviously unrea

sonable as applied to the victim of other forms of discrimina

tion. The scope of the waiver must be restricted to release

of the rights which are the subject of the compromise at issue

— i.e. the right to be free from discrimination in trans

ferring to road driver jobs.

-28-

CONCLUSION

For the above reasons the orders of the District

Court of February 14 1975, January 19, 1976 and March 18

1976, insofar as they approve the use or solicitation of

waivers of Title VII or other rights, should be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

JACK GREENBERG

0, PETER SHERWOOD

ERIC SCHNAPPER

Suite 2030

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

WILEY BRANTON

Dolphin, Branton, Stafford & Webber

Suite 500

McLachlen Bank Building

Washington D.C. 20001

Counsel for Appellants

-29-