Sims v GA Brief for Respondent

Public Court Documents

October 1, 1967

48 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Sims v GA Brief for Respondent, 1967. 5659e97e-c49a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/bd86e70d-4251-4d66-a779-29da90146af8/sims-v-ga-brief-for-respondent. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

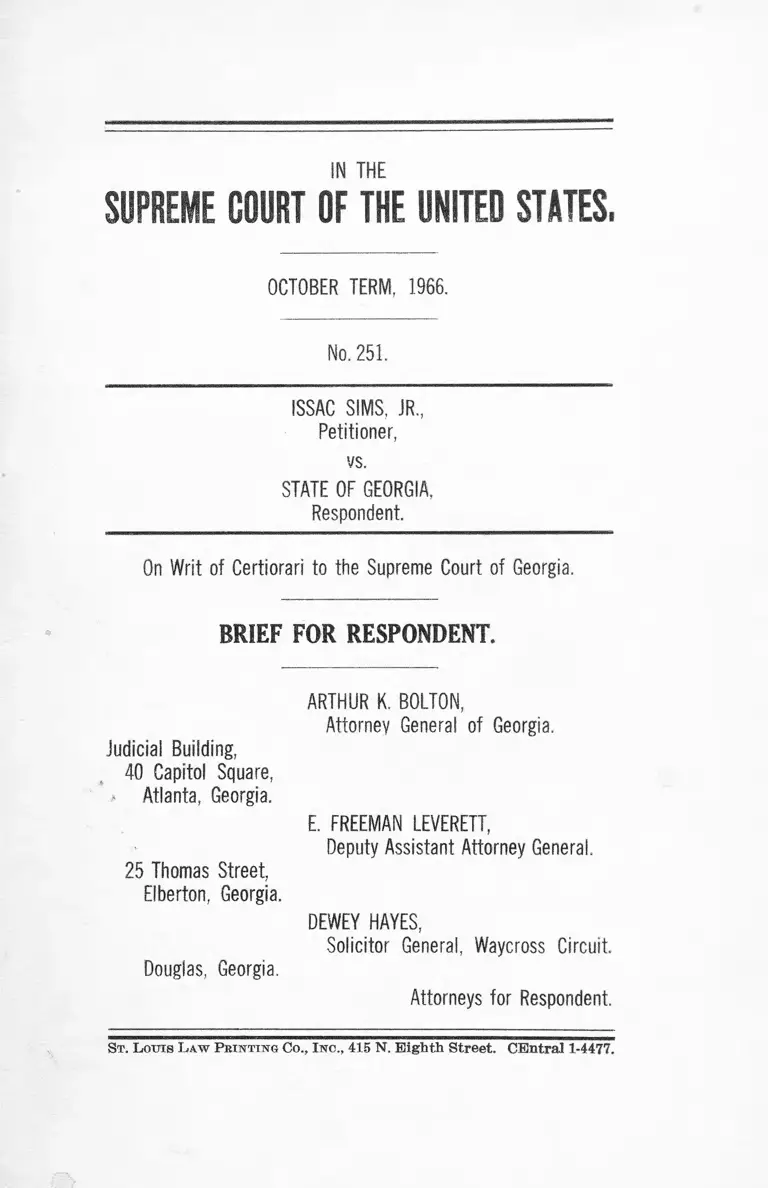

IN T H E

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES,

OCTOBER TER M , 1966.

No. 251.

ISSAC SIMS, JR.,

Petitioner,

vs.

STATE O F GEORGIA,

Respondent.

On Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Georgia,

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENT.

ARTHUR K. B O LTO N,

Attorney General of Georgia.

Judicial Building,

40 Capitol Square,

Atlanta, Georgia.

E. FR EEM A N LEV ER ET T ,

Deputy Assistant Attorney General.

25 Thomas Street,

Elberton, Georgia.

DEW EY HAYES,

Solicitor General, Waycross Circuit

Douglas, Georgia.

Attorneys for Respondent.

St. Loots L aw Printing Co., Inc., 41.5 N. Eighth Street. CEntral 1-4477.

INDEX.

Page

Opinions below ...................................................................... 1

Jurisdiction ........................................................................ 2

Questions presented ............................ 2

Statement ............................... 4

Summary of argument....................................................... 9

Argument ............................................................................... 12

I. No rights of petitioner were violated by admis

sion in evidence of the confessions .......................... 12

A. The decision below is not in conflict with

Jackson v. D enno............................................... 12

B. The standards applied below to determine

voluntariness were not insufficient...................... 17

C. The confession was not obtained under in

herently coercive circumstances ........................ 18

D. The decision below does not violate peti

tioner’s Sixth Amendment right to counsel

under Escobedo v. Illin o is ............................... 25

II. There was no denial of equal protection by the

rulings below relating to the challenges to the

grand and petit ju r ie s ............................. 27

A. No error results from the action of the Geor

gia Courts in restricting proof to the current

jury l is ts ............................................................... 28

B. The use by the jury commissioners of the Tax

Digest, required by law to list Negro taxpay

ers separately, shows no violation of the con

stitution .......................................................... 31

C. There was no prima facie showing of discrimi

nation from the statistics................................. 39

Conclusion .................................................................. 40

11

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES.

Gases.

Akins v. Texas, 325 U. S. 398, 89 L. Ed. 1692 (1945). .28,

Anderson v. Martin, 375 U. S. 833, 11 L. Ed, 2d 439

(1964)

Ashcraft v. Tennessee, 322 U. S. 143, 88 L. Ed. 1192

(1944) ..............................................................................

Avery v. Georgia, 345 U. S. 559, 97 L. Ed. 1244

(1953) ...................................................................... 11,32,

Billingsley v. Clayton, 359 F. 2d 13 (C. A. 5th, 1966). .30,

Blackburn v. Alabama, 361 U. S. 199, 4 L. Ed. 2d

242 (1960) ............................................. ........................

Boles v. Stevensou, 379 U. S. 43, 13 L. Ed. 2d 109

(1964) ............................................................................ 9,

Brookins v. State, 221 Ga. 181, 144 S. E. 2d 83 (1965)

Brooks v. Beto, . . . F. 2d . . . , 35 L. W. 2077 (July

29, 1966) ........................................................................

Brown v. Allen 344 U. S. 443, 97 L. Ed. 469 (1953) . .11,

Bush v. Kentucky, 107 U. S. 110, 117, 27 L. Ed. 354

(1883) ..............................................................................

Cassell v. Texas, 339 U. S. 282, 291, 94 L. Ed. 839

(1950) ....................................................... ............ 29,31,

Chambers v. Florida, 309 U. S. 227, 84 L. Ed. 716

(1940)

Claybourn v. State, 190 Ga. 861, 869, 11 S. E. 2d 23

(1940) ..............................................................................

Culcombe v. Connecticut, 367 U. S. 568, 6 L. Ed. 2d

1037 (1961) .................................................................. 18-

Downs v. State, 208 Ga. 619, 621, 68 S. E. 2d 568

(1952) .............................................................................

Escobedo v. Illinois, 378 U. S. 478, 12 L. Ed. 2d 977

(1964) .......................................................................2,10,

, 31

32

19

33

31

19

14

32

34

29

31

34

18

13

-19

13

25

Ill

Fay v. New York, 332 U. S. 261, 285, 91 L. Ed. 2043

(1947) ............................................................................. 28,

Fay v. Noia, 372 U. S. 391, 438, 9 L. Ed. 2d 837

(1963) ............................................................................... 3,

Fikes v. Alabama, 352 U. S. 191, 197, 2 L. Ed. 2d 246

(1957) ................................................... 2,17,19,

Gallegos v. Nebraska, 342 U. S. 55, 65, 96 L. Ed. 86

(1957) ............................................................ ............... 17,

Hall v. State, 65 Ga. 36 (1880) .......................................

Haley v. Ohio, 338 U. S. at 52.......................................

Hamm v. Virginia State Board of Elections, 230 F.

Snpp. 156 (D. C. Va. 1964), aff’d sub nom. Tancil v.

Woolls, 379 U. S. 19, 13 L. Ed. 2d 91 (1964) ..........

Harris v. South Carolina, 338 U. S. 68, 93 L. Ed. 1815

(1949) ..............................................................................

Harris v. Stephens, 361 F. 2d 888, 892 (C. A. 8th, 1966)

Haynes v. Washington, 373 U. S. 503, 513, 10 L. Ed.

2d 513 (1963) ..................................... ................... 17,19,

Hill v. Texas, 316 U. S. 400, 404, 86 L. Ed. 1559 (1942)

Hoyt v. Florida, 368 U. S. 57, 7 L. Ed. 2d (1961) . . . .

Jackson v. Denno, 378 U. S. 368, 12 L. Ed. 2d 908

(1964) ................................................................... 2,9,12,

Jackson v. United States, 337 F. 2d 136, 140-141 (C. A.

D. C. 1964), cert. den. 380 U. S. 935, 13 L. Ed. 2d

822 (1965) .............................................. ......................

Johnson v. New Jersey, 384 U. S. 719, 16 L. Ed. 2d

882 (1966) ......................................................................

Johnson v. Pennsylvania, 340 U. S. 881, 95 L. Ed. 640

(1950) ..............................................................................

Jugiro v. Brush, 140 U. S. 291, 297, 35 L. Ed. 510

(1891) .............................................................................

Lisenba v. California, 314 U. S. 219, 235, 86 L. Ed. 166

(1941) ................................................... 21,24,

Long v. United States, 338 F. 2d 549 (C. A. D. C. 1964)

31

15

20

20

13

20

32

18

32

25

34

31

14

26

25

18

31

25

26

XV

Lyons v. Oklahoma, 322 U. S. 596, 601, 88 L. Ed. 1481

(1944) .............................................................9,18,21,22,23

Malinski v. New York, 324 U. S. 401, 89 L. Ed. 1029

(1945) .............................................................................. 19

Martin v. Texas, 200 U. S. 316, 320, 50 L. Ed. 497

(1906) ....................................... ..................... ................ 3i

Massiah v. United States, 377 U. S. 201, 12 L. Ed.

2d 246 (1964) .............................................................. 26

Maxwell v. Stevens, 348 F. 2d 325 (C. A. 8th, 1965) 32

McNabb v. United States, 318 U. S. 332, 346, 87 L. Ed.

819 (1943) ....................................................................... 25

Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U. S. 436, 16 L. Ed. 2d 694

(1966) .............................................................................. 25

Neal v. Delaware, 103 U. S. 370, 26 L. Ed. 567 (1881) 31

Pollard v. State, 148 Ga. 447 (3), 96 S. E. 997 (1918).. 27

Reck v. Pate, 367 U. S. 433, 6 L. Ed. 2d 948 (1961).. 19

Rogers v. Richmond, 365 U. S. 534, 5 L. Ed. 2d 760

(1961) .............................................................................. 18

Scott v. Walker, 358 F. 2d 56 (C. A. 5th, 1966) ........... 31

Sims v. Balkcom, Warden, 220 Ga. 7, 136 S. E. 2d 766

(1964) ................................................................................ 1)4

Sims v. State, 221 Ga. 190, 144 S. E. 2d 103 (1965),

cert, granted, 384 U. S. 998, 16 L. Ed. 2d 1013

(I960) ................... 1,4

Smith v. Texas, 311 U. S. 128, 130, 85 L. Ed 84

(1940) .............................................................................31,34

Spano v. New York, 360 U. S. 315, 3 L. Ed. 2d 1265

(1959) .............................................................................. 19

Stein v. New York, 346 U. S. 156, 182, 185, 97 L. Ed

1522 (1953) ............................... 17,21

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U. S. 303, 305, 25

L. Ed. 664 (1880) ......................................................... 31

Stroble v. California, 343 U. S. 181, 191, 96 L. Ed. 872

(1952) ....................................................................... 17,21,22

V

Swain v. Alabama, 380 U. S. 202, 13 L. Ed. 2d 759

(1965) ................................................................. 11,28,30,31

Thomas v. Arizona, 356 U. S. 390, 2 L. Ed. 2d 863

(1958) ....................................................................... 20,21,22

Thomas v. Texas, 212 U. S. 278, 53 L. Ed. 512 (1909) 31

United States ex rel. Goldsby v. Harpole, 263 F. 2d

71 (C. A. 5th, 1959), cert. den. 361 U. S. 838 .......... 31

United States ex rel. Goldsby v. Harpole, 263 F. 2d 71

(C. A. 5th 1964) ............................................................ 39

United States ex rel. Seals v. Wiman, 304 F. 2d 53

(C. A. 4th, 1962), cert. den. 372 U. S. 924 ................ 31,34

United States v. Carnignan, 342 U. S. 36, 38, 96 L. Ed.

48 (1951) ................................................................ 13

Virginia v. Rives, 100 U. S. 313, 25 L. Ed. 667 (1880) 31

Watts v. Indiana, 338 U. S. 49, 93 L. Ed. 1801 (1949) .18, 29

White v. Texas, 310 U. S. 530, 84 L. Ed. 1342 (1940) 18

Whitus v. Balkeom, 333 F. 2d 496 (C. A. 5th, 1964),

cert. den. 379 U. S. 931, 13 L. Ed. 2d 343 (1965).. 15

Williams v. Georgia, 349 U. S. 375, 99 L. Ed. 1161

(1955) ................................... 32

Wood v. Brush, 140 U. S. 278, 285, 35 L. Ed. 505

(1891) ........................................................ 31

Statutes.

Code of Georgia of 1882, § 3910 (b) ............................... 35

Constitution of 1877, Art. II, par. I I ............................. 38

Constitution of Georgia, Art. I, Sec. I, Par. V (Code

Ann., § 2-105) ................................................................ 13

Constitution of Georgia, Art. VI, Sec. XVI, Par. I

(Code Ann., §2-5101) ................................................... 13

Ga. Code, § 27-210 ............................................................. 20

Ga. Code, § 27-212 ............................................................ 20

Ga. Code, § 27-901 ............................................................. 20

Ga. Code, § 38-411 ............................................................. 17

Ga. Code, § 59-106 ...........................................................31,

Ga. Code, § 59-109 ................................. ...........................

Ga. Code, § 59-201 .............................................................

Ga. Code, § 59-203 ................................... .........................

Ga. Code, § 59-701 .............................................................

Ga. Code, § 92-108 .............................................................

Ga. Code, § 92-6302 ...........................................................

v i

Ga. Code, § 92-6307 ....................................... 27, 32, 35, 38,

Georgia Laws 1894, pp. 31, 115 ................................... 36,

Georgia Laws 1908, p. 2 7 ...................................................

Georgia Laws 1927, p. 5 7 .................................................

Georgia Laws 1966, Vol. I, p. 393 ................................. 32,

28 USCA, Sec. 1257 (3) .....................................................

Miscellaneous.

Alex Mathews Arnett, “ The Populist Movement in

Georgia,” 7 Ga. Hist. Quart. 313, 332 (1923) ..........

Atlanta Constitution, November 8, 9, 15, 1894 ..........37,

Coulter, Georgia, A Short History, p. 393 (1 9 4 7 )........

50 Iowa L. R. 909, 917 (1965) .......................................

49 Minn. L. R. 360, 363 (1964) .......................................

Georgia House Jour., 1894, pp. 42, 230 ........................37,

Leverett, “ Confessions and the Privilege Against Self-

Incrimination” , 1 Ga. St. B. J. 433, 441 (May, 1965)

McElreath on the Constitution of Georgia, § 854..........

Siegel, “ The Fallacies of Jackson v. Denno,” 31 Brook-

lin L. R. 50, 58 (1964) ...................................................

United States Census of Population 1960, Georgia

General Social and Economic Characteristics, PC(1)

12c Ga., p. 334 ................................. ............................

35

27

35

27

27

38

32

39

37

38

38

39

2

37

38

36

14

13

38

13

38

13

29

IN T H E

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES.

OCTOBER TER M , 1966.

No. 251.

ISSAC SIMS, JR .,

Petitioner,

vs.

STATE O F GEORGIA,

Respondent.

On Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Georgia.

BRIEF FOR RESPONDENT.

OPINIONS BELOW.

The opinion of the Supreme Court of Georgia under

review (R. 328) is reported as Sims v. State, 221 Ga.

190, 144 S. E. 2d 103 (1965), cert, granted, 384 U. S. 998,

16 L. Ed. 2d 1013 (1966). Prior decision of the Supreme

Court of Georgia setting aside the first conviction on

habeas corpus, is reported as Sims v. Balkcom, Warden,

220 Ga. 7, 136 S. E. 2d 766 (1964).

JURISDICTION.

Jurisdiction is invoked under 28 USCA, Sec. 1257 (3).

QUESTIONS PRESENTED.

In granting certiorari, the order of this Court declared

that the writ was granted, limited to five questions as

stated by the petition, as follows:

“ 1. Whether petitioner’s Fourteenth Amendment rights

were violated by a conviction and sentence to death ob

tained on the basis of a confession made under inherently

coercive circumstances within the doctrine of Fikes v.

Alabama, 352 U. S. 191.

“ 2. Whether petitioner’s Fourteenth Amendment rights

were violated by the failure of the Georgia courts to

afford a fair and reliable procedure for determining the

voluntariness of his alleged coerced confession in dis

regard of the principle of Jackson v. Denno, 378 U. S.

368.

“ 3. Whether petitioner’s Fourteenth Amendment right

to counsel as declared in Escobedo v. Illinois, 378 U. S.

478, was violated by the use of his confession obtained

during police interrogation in the absence of counsel, or

whether petitioner’s right to counsel was effectively

waived.

“ 4. Is a conviction constitutional where:

(a) local practice pursuant to state statute re

quires racially segregated tax books and county

jurors are selected from such books;

(b) the number of Negroes chosen is only 5% of

the jurors but they comprise about 20% of xthe tax

payers; and

— 2 —

3

(c) a Negro criminal defendant’s offer to prove a

practice of arbitrary and systematic Negro inclusion

or exclusion based on jury lists of the prior ten years

is disallowed.

“ 5. Where a Negro defendant sentenced to death in

Georgia for the rape of a white woman offers to prove

that nineteen times as many Negroes as whites have been

executed for rape in Georgia in an effort to show that

racial discrimination violating the equal protection clause

of the Fourteenth Amendment produced such a result,

may this offer of proof be disallowed?” 1 (R. 356).

Respondent obviously does not concur in the form in

which the questions are stated. The contentions of Re

spondent are fully set out in the “ Summary of Argu

ment,” infra.

1 Petitioner has expressly abandoned this point in his brief

(p. 3). Respondent does not agree with the assertion, how

ever, that this question can be raised at a later date. This

Court granted certiorari to hear it, and the abandonment of

it here constitutes a waiver and “ deliberate by-passing” of an

existing remedy. See Fay v. Noia, 372 U. S. 391, 438, 9 L. Ed.

2d 837 (1963).

4

STATEMENT.

Issac Sims, a 29 year old Negro, was convicted at the

1963 October Term of the Superior Court of Charlton

County, of the rape of a white woman and sentenced to

death (R. 251). His Court-appointed attorney declined to

file an appeal to the Supreme Court of Georgia, and while

awaiting execution at the Georgia State Prison, habeas

corpus was instituted in the City Court of Reidsville, as

serting as grounds therefor, denial of counsel, racial dis

crimination in the selection of the grand and petit juries,

and the claim that imposition of the death penalty for

rape was violative of the Fourteenth Amendment for sev

eral reasons. The trial court remanded the prisoner, hut

on appeal, the Supreme Court of Georgia held that jury

discrimination could not be raised by habeas corpus; re

jected the contention that imposition of the death penalty

was unconstitutional for any reason; but set aside the con

viction on the grounds that the failure of counsel to ap

peal, and the failure of the trial court to appoint other

counsel, constituted a denial of counsel under both the

state and federal constitutions. Sims v. Balkcom, Warden,

220 Ga. 7, 136 S. E. 2d 766 (1964).

Following remand, the jury boxes were revised (R. 76),

petitioner was reindicted at the 1964 October Term (R. 1),

tried and again sentenced to death (R. 316). Motion for

new trial was filed (R. 22), later amended (R. 24), over

ruled (R. 317), and appeal was then taken to the Su

preme Court of Georgia (R. 318). The conviction was

affirmed by that Court. Sims v. State, 221 Ga. 190, 144

S. E. 2d 103 (1965) (R. 328). This Court granted cer

tiorari on June 20, 1966 (R. 356), limited to 5 questions.2

Sims v. Georgia, 384 U. S. 998, 16 L. Ed. 2d 1013 (1966).

2 See “ Questions Presented” , supra.

5

The facts material to an understanding of the issues

are as follows: On April 13, 1963, at approximately 10

o ’clock A. M., the victim, a 29 year old white woman

(R. 157), was proceeding toward her home on a dirt road

approximately 3 miles from St. George, Georgia, when

petitioner in a following vehicle suddenly rammed her car

from the rear, knocking it in the ditch and turning it

completely around (R. 151). Petitioner emerged from

his vehicle, forced the victim into the woods where she

was choked, struck in the face, and forcibly raped (R.

152). When first seen following the crime, her face was

streaming blood (R. 159) and her eyes, nose, and mouth

were bleeding (R. 161, 187). As also stated by the ex

amining physician,

“ When I saw her she was lying on the emergency

room table, very emotionally upset and almost in a

state of shock from the experience that she said she

had just gone through. Her clothes were dirty that

she had on; her face was dirty; there was mud about

her legs; and her face had blood stains, had bruise

marks, and there was clotted blood about, particu

larly her nose, and the eyes were bloodshot. There

were marks on her neck, chest, and breast, and there

were marks on her lower abdomen, and her female

parts showed evidence of fresh trauma. There was

a bleeding area and a small torn area in the lower

part” (R. 153).

Petitioner left the scene on foot in the direction of the

Toledo community (R. 153) and while police officers were

tracking with bloodhounds at the scene (R. 180) a local

citizen contacted his Negro employees at Toledo and in

structed them to be on the lookout for any strange man

(R. 163). Around 2:30 P. M. that afternoon, two of these

Negro employees, T. W. Walker and Arthur Lee Walker,

spotted petitioner at the Toledo community with mud on

his clothes (R. 170). Upon approaching petitioner,

6

Arthur advised petitioner that the “ law” was looking-

for him, after which the following ensued:

. and I asked him did he really attack that white

woman.

Q. You asked him what?

A. Did he attack that white woman.

Q. And what did he say?

A. He said he did.

Q. Did anybody tell him to make a statement?

A. No, sir.

Q. And you asked him what, now?

A. I asked him did he attack that white woman,

and he said ‘ yes’. And at that time he took off and

took a little trot towards the swamp down there, and

I backed up to the window and asked Boy Roberson

for his gun, and I called him, and he turned and

come back to me, and he got just about to me and

I throwed the gun on him and told him to go and

sit on T. W .’s porch . . . ” (R. 176-7).

This admission, it should be noted, was admitted with

out objection.

Petitioner was picked up by the Walkers’ employer

around 3:30 P. M. (R. 164), and turned over to two state

patrolmen (R. 184) who took him to Dr. Jackson’s office

in Folkston where his clothes were removed for evidence

(R. 185). Following this, petitioner was removed to the

Ware County jail in Waycross, Georgia (R. 185), around

5 or 6 o ’clock (R. 133). Around 6:30 that same after

noon, petitioner recognized Deputy Dudley Jones at the

jail whom he had known as a deputy sheriff in Charlton

County, and called to him. A conversation ensued in

which petitioner stated that he had “ got in trouble with

a white woman” and wished to make a statement to the

sheriff (R. 209-210). Deputy Jones contacted Sheriff Lee,

and around 10:30 that same night, Sims was brought

7

downstairs to the interview room where his statement

(E. 226) was written out, read to him and signed by him,

the entire proceeding taking only 20 to 30 minutes (E.

104, 119, 212). Sheriff Lee testified that he advised Sims

that he was entitled to an attorney and that any state

ment could be used against him in Court (E. 97, 99, 224).

Petitioner stated that he did not desire an attorney (E.

100, 120, 224). Petitioner Sims testified under oath that

he remembers the statement being read to him (E. 136);

that all the officers talked “ nice” to him in the interview

room (E. 139); that nobody threatened him (E. 140); that

he recalls the sheriff telling him that anything he said

could be used against him (E. 140); that Deputy Jones

was “ friendly” to him and he wasn’t scared (E. 141-2);

that nobody beat or threatened him (E. 142); that he con

sidered Deputy Jones his friend (E. 143); that he signed

the statement after it was read to him (E. 141); and that

he signed it because it was “ right” (E. 141).

At his second trial, petitioner was represented by a

Negro attorney active in civil rights litigation who filed

plea in abatement to the indictment based upon a claim

of jury discrimination (E. 3); a challenge to the array of

petit jurors for like reason (E. 6); motion for change of

venue (E. 9); motion to suppress the confession made in

the Ware County jail (E. 13); a plea in abatement attack

ing the Georgia rape statute, Code Sec. 26-1302, facially

and as applied (E. 17); and an oral motion to quash.

All of these motions were denied (E. 5, 8, 12, 16, 18, 146).

As it will be necessary to refer at length to the evidence

relative to several of these motions in the Argument,

further reference will not be made here. The trial com

menced on October 7, and was concluded on October 8,

resulting in a verdict of guilty without recommendation

of mercy (E. 2). Motion for new trial was filed in the

usual “ skeleton” form (E. 22). In due course, it was

amended so as to assign error on the admission of the

8

confession and call in question the Georgia procedure of

submitting the issue to the jury (E. 24). The motion was

overruled (E. 317). Appeal was thereupon taken to the

Supreme Court of Georgia by bill of exceptions which

additionally assigned error on the orders overruling the

several pleas and motions previously referred to (E. 318).

The Supreme Court of Georgia affirmed (E. 328). This

Court granted certiorari (E. 356).

9

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT.

L

Admission in evidence of the confessions obtained from

petitioner while in custody violated none of his rights.

(A) Prior to trial, a full scale hearing was held by the

Court on Petitioner’s motion to suppress the confessions,

which complied with the requirements of Jackson v. Denno,

378 U. S. 368, 12 L. Ed. 2d 908 (1964). The only thing

which the trial court did not do that it might have done,

was to read into the record explicit findings of fact. Cf.

Boles v. Stevenson, 379 U. S. 43, 13 L. Ed. 2d 109 (1964).

However, any failure in the respect, even assuming it other

wise deficient, is immaterial here, since (1) Counsel for

petitioner expressly waived any further effort on the part

of the Court to comply with Jackson v. Denno, and (2) Pe

titioner himself having testified under oath at the trial

that he signed the confession, that he was not afraid, and

that it was “ right” , demanded a finding that the confes

sions were voluntary, as the Supreme Court of Georgia

so held (R. 329).

(B) The standards applied by the trial court in its

charge to determine voluntariness (in effect, Code, § 38-411)

do not fall short of that required by decisions of this

Court. The sufficiency of instructions in this regard is

not a matter of federal concern. Lyons v. Oklahoma, 322

U. S. 596, 601, 88 L. Ed. 1481 (1944).

(C) The confession was not obtained under inherently

coercive circumstances. Petitioner was taken into custody

around 3 o ’clock on (Saturday afternoon. Just prior

thereto, before being arrested, he had spontaneously ex

claimed to Negro turpentine workers that he had “ at

tacked that white woman” (R. 176). He was placed in

10

jail between 5 and 6 o ’clock P. M., and around 6:30, upon

seeing a deputy sheriff whom he had known for many

years, called to the deputy and in the course of a casual

conversation, stated that he had raped a white woman,

and that he wished to make a statement to the sheriff (R.

210). Around 10:30 that same evening he was brought

downstairs in the jail where the statement was made, after

being advised fully of his rights, the entire conversation

taking 15 to 30 minutes. Petitioner’s claim that he was

earlier subjected to physical abuse while being examined

in a doctor’s office prior to being put in jail are disputed

by the evidence, and in any event, no causal relation is

shown between what took place in the doctor’s office that

afternoon and the confessions made later that night in

the jail, in the presence of entirely different persons.

(D) Since petitioner expressly stated that he did not

desire counsel after being fully advised of his rights, use

of the confessions later obtained does not violate the rule

of Escobedo v. Illinois, 378 U. S. 478, 12 L. Ed. 2d 977

(1964).

II.

Discrimination in jury selection does not appear from

the record.

(A) No error is shown from the action of the Georgia

Courts in restricting proof to the current jury lists, since it

appears that the lists had just been revised, and Negroes

were then serving on juries in Charlton County. In any

event, (1) The offer of proof was not sufficient; (2) The

evidence was sufficient to overcome any prima facie case

which such evidence otherwise might have established.

(B) Use of the county tax digest in making up the jury

lists is not unconstitutional because of the fact that the

digest is required by law to be separated according to

race. The digest is used in making up the jury boxes,

— 11

not the panels. As to the former, the decisions of this

Court require that jury commissioners apprise themselves

of the racial identity of those eligible for service, in order

to insure that discrimination does not result. This process

is deliberative. Avery v. Georgia, 345 U. S. 559, 97 L. Ed.

1244 (1953), on the other hand, involves the making up

of the panels for each term of court, and the selection

process at this stage is designed to be by chance, without

regard to the identity of individual jurors. The legisla

tive history of the state law attacked here (repealed in

1966) shows that it was not designed as an instrument of

discrimination, but was motivated by a desire to facilitate

identification in registration made difficult by previous

practice whereby Negroes were entered on the tax digest

under the names of their employers.

(C) There was no prima facie showing of discrimina

tion from the fact that Negroes constitute 20% of the tax

payers, and a lesser percentage of jurors. Swain v. Ala

bama, 380 U. S. 202, 13 L. Ed. 2d 759 (1965); Brown v.

Allen, 344 U. S. 443, 97 L. Ed. 469 (1953).

ARGUMENT.

I.

No Rights of Petitioner Were Violated by Admission

in Evidence of the Confessions.

Petitioner contends that admission of the confessions

in evidence at the trial were violative of his rights for

four reasons. Respondent will consider these contentions

in the same order urged by petitioner.

A. The Decision Below Is Not in Conflict With Jackson

v. Denno.

It is the position of Respondent that the rule of Jack-

son v. Denno, 378 U. S. 368, 12 L. Ed. 2d 908 (1964), was

not violated by the state courts because (1) The pro

cedure followed below complied with the requirements

of that decision, (2) Counsel for petitioner during trial

expressly waived any further proceedings by the court to

comply with the rule, and (3) Under the undisputed

facts, there was no issue for determination, petitioner’s

own testimony demanding a finding of voluntariness.

First, as to the procedure employed by the Court, it is

to be observed that prior to trial, counsel for petitioner

filed a “ motion to suppress illegally obtained evidence”

(R. 13-16) which sought to suppress the written confes

sion. A full scale hearing was had on this motion before

the trial began outside the presence of the jurors (R. 47).

At this hearing, the sheriff and deputy sheriff who were

present when the confession was made testified at length,

as well as petitioner himself (R. 96-145). At the con

clusion, the motion was overruled (R. 147, 16).

Prior to the decision of this Court in Jackson v. Denno,

supra, Georgia was one of the states which followed the

New York rule, as this Court noted (378 U. S. at 396).

— 12 —

13

As stated in Downs v. State, 208 Ga. 619, 621, 68 S. E.

2d 568 (1952),

“ The State having made out a prima facie case

that the alleged confession was freely and voluntarily

made, it was a question for the jury to determine on

conflicting evidence whether the alleged confession

was freely and voluntarily made.”

While it was early suggested that the preliminary hear

ing should be held outside the presence of the jury, Hall v.

State, 65 Ga. 36 (1880), in practice this rarely has been

done in the past, cf. United States v. Carnignan, 342 U. S.

36, 38, 96 L. Ed. 48 (1951), and note, 49 Minn. L. R. 360,

363 (1964), it was done here. In addition, when the

matter of the confession came up during trial before the

jury, the latter was excused while Sheriff Lee was sub

jected to cross-examination before the confession was ad

mitted (R. 225), but counsel for petitioner then withdrew

his request (E. 226). The Court also submitted the issue

of voluntariness to the jury (E. 312), but this was neces

sary under state law. The Constitution of Georgia, Art. I,

Sec. I, Par. V (Code Ann., §2-105), guarantees every ac

cused “ a public and speedy trial by an impartial jury.”

See also, Constitution, Art. VI, Sec. XYI, Par. I (Code

Ann., §2-5101), declaring that “ The right of trial by

jury, except where it is otherwise provided in this Con

stitution, shall remain inviolate . . . ” This includes the

right of the accused to have the issue as to the voluntari

ness of a confession ultimately decided by a jury. Clay-

bourn v. State, 190 Ga. 861, 869, 11 S. E. 2d 23 (1940).

To comply with this Court ’s decision in the Denno case,

the issue must now be independently resolved by the trial

judge, but in order to comply with the State Constitution,

it must also be submitted to the jury. See Leverett, “ Con

fessions and the Privilege Against Self-Incrimination, ” 1

Ga. St. B. J. 433, 441 (May, 1965), and cf. Siegel, “ The

Fallacies of Jackson v. Denno,” 31 Brooklyn L. E. 50, 58

14

(1964); Note, 50 Iowa L. R. 909, 917 (1965). About the

only thing which the trial judge might have done here

which he did not do would have been to read into the

record specific findings of fact so as to afford “ a reliable

and clear cut determination of the voluntariness of the

confession.” Boles v. Stevenson, 379 U. S. 43, 45, 13

L. Ed. 2d 109 (1964). However, as respondent will pres

ently show, the evidence so far demanded a finding of

voluntariness as to render this failure harmless. The

Georgia procedure followed here was therefore tantamount

to the Massachusetts rule, which this Court specifically

approved in Jackson v. Denno, supra (378 U. S. at 378).

Second, any further effort toward compliance with Jack-

son v. Denno was expressly waived here. After the state

had questioned Sheriff Lee as to the details of the con

fession, the following transpired:

“ The Defendant’s Attorney: Your Honor, we’d like

to have the opportunity to examine this witness be

fore the statement is read into the record.

The Court: All right.

The Solicitor General: Would you like to do it at

this time?

The Defendant’s Attorney: I believe the rule re

quires that the jury be excused.

The Court: All right, let the jury go to the jury

room.

(The jury thereupon retired from the court room.)

The Solicitor General: I was under the impression

that he had already examined Sheriff Lee this morn

ing concerning this statement, and that is a matter

of record.

The Court: All right.

The Defendant’s Attorney: As your Honor knows,

the rule has been recently changed by the Supreme

— 15

Court of the United States, and we did have an op

portunity to examine the witness today, and on that

basis, your Honor, I withdraw my request that the

jury be excused and let him proceed with the direct

examination. I don’t know whether the procedure

being followed at this time satisfied the rule decided

by the Supreme Court on June 22, 1964, that the

Court must make judicial determination whether the

statement was made voluntarily before it is read to

the jury. We did make an examination today, and I

withdraw the request for the jury to be excused.

The Court: All right, bring the jury back” (R.

225-6).

This clearly constitutes a waiver—a “ deliberate by

passing” of any further or different procedural handling

of the issue. Fay v. Noia, 372 U. S. 391, 438, 9 L. Ed. 2d

837 (1963). Insofar as it might be urged that petitioner

did not himself participate in this decision, it is enough

to say that this technical issue was of such nature that

petitioner could not realistically comprehend it anyway.

Whitus v. Balkcom, 333 F. 2d 496 (C. A. 5th, 1964), cert,

den. 379 U. S. 931, 13 L. Ed. 2d 343 (1965).

Third, the evidence demanding a finding that the con

fession was voluntary, and any failure of the trial court

to make an express finding to this effect was harmless.

The Supreme Court of Georgia so held. See division 5 (c)

of the syllabus to its decision (R. 329). The crime was

committed around 10 o ’clock A. M. on Saturday, April 3,

1963 (R. 150). At approximately 1 or 2 o ’clock later that

afternoon, petitioner appeared at the Toledo settlement,

and before he was ever taken into custody, stated to sev

eral Negro turpentine workers that he had “ attacked a

white woman” (R. 176, 179). He was then placed under

citizen’s arrest by these Negro workers (R. 176), and

handed over to the Georgia State Patrol around 3 o ’clock

16

(R. 185). Petitioner was taken to Dr. Jackson’s office

where a physical examination was conducted which lasted

15 minutes (R. 207). He was then taken to the hospital

where a cut over his eye was treated (E. 207), after which

he was taken to the Ware County jail and confined some

time between 5 and 6 P. M. (R. 133). Some time around

6:30, Deputy Dudley Jones happened to be putting a pris

oner in the jail (R. 210), when petitioner, recognizing him

as having been a deputy previously in Charlton County,

called to Deputy Jones and told him that he, petitioner,

had “ got in trouble with a white woman” (R. 113, 138,

210). Upon being asked whether he wished to make a

statement to the sheriff, petitioner replied that he did (R.

210). Petitioner admitted talking to Deputy Jones, and

that he was treated “ nice” and no effort was made to

beat him or to “ say anything” to him (R. 139). About

10:30 later that night, petitioner was brought downstairs

in the interview room where the confession was made

(R. 113, 210, 223). Petitioner testified under oath that

the officers talked “ nice” to him (R. 139); that he

wasn’t beaten or threatened (R. 139-142); that he wasn’t

afraid of Deputy Jones, who was “ friendly” to him (R.

141-3); that he recalls the Sheriff telling him that any

thing he said could be used against him (R. 140); that he

wasn’t scared (R. 142); that the statement was read to him,

and that he signed it because it was right (R. 141). It is

also undisputed that the interrogation and taking of the

statement took only about 15 to 30 minutes (R. 104, 119).

Petitioner had not been taken before a judge, as it was

Saturday evening and none was available (R. 236).

It is thus seen that petitioner confessed initially after

having been in jail only an hour or so during a casual

conversation, and that the written confession was given

about 4 hours later, the latter lasting only 30 minutes at

the most. There is not the slightest evidence that the

confessions made in the Ware County jail were anything

17

but voluntary. To hold otherwise would require a rejec

tion of petitioner’s own sworn testimony at the trial.

Where as here an accused admits at the trial that his con

fession was signed after it was read to him and because it

was “ right,” there is no issue for judge or jury to deter

mine. Viewed in the light of the previous, spontaneous

confession to the Negro turpentine workers made before

he was taken into custody (R. 176, 179), the record “ sug

gests strongly that petitioner had concluded, quite inde

pendently of any duress by the police, that it was wise to

make a clean breast of his guilt.” Stroble v. California,

343 U. S. 181, 191, 96 L. Ed. 872 (1952).

B. The Standards Applied Below to Determine Volun

tariness Were Not Insufficient.

This contention (Brief, p. 22) attacks the charge on

voluntariness given to the trial jury (R. 312), which was

in effect the provisions of Ga. Code, § 38-411, which de

clares :

“ Confessions must be voluntary.—To make a con

fession admissible, it must have been made voluntarily,

without being induced by another, by the slightest

hope of benefit or remotest fear of injury.”

Under decisions of this Court dealing with confessions,

“ the accepted test is their voluntariness,” Gallegos v.

Nebraska, 342 U. S. 55, 65, 96 L. Ed. 86 (1957), which de

pends “upon a weighing of the circumstances of pressure

against the power of resistance of the person confessing.”

Stein v. New York, 346 U. S. 156, 185, 97 L. Ed. 1522

(1953); Fikes v. Alabama, 352 U. S. 191, 197, 2 L. Ed. 2d

246 (1957). “ In short, the true test of admissibility is

that the confession is made freely, voluntarily and with

out compulsion or inducement of any sort.” Haynes v.

Washington, 373 U. S. 503, 513, 10 L. Ed. 2d 513 (1963).

Ultimately, the test announced in the decisions of this;

— 18

Court do not differ from that as stated by Georgia law

and applied below. Rogers v. Richmond, 365 U. S. 534,.

5 L. Ed. 2d 760 (1961), relied upon by petitioner, does not

hold that any specific form of words must be used. It does,

not deal with what must be considered but rather with

one thing which must not be considered, i. e., the probable

reliability of the confession as one circumstance in deter

mining its voluntariness. 365 U. S. at 542. This is a

different proposition from the contention made here which

was rejected by this Court in Lyons v. Oklahoma,, 322

U. S. 596, 601, 88 L. Ed. 1481 (1944), where it was said:

“ The question of how specific an instruction in a

state court must be upon the involuntary character

of a confession is, as a matter of procedure or practice,

solely for the courts of the state. When the state

approved instruction fairly raises the question of

whether or not the challenged confession was volun

tary, as this instruction did, the requirements of due

process, under the Fourteenth Amendment are satisfied

and this Court will not require a modification of local

practice to meet views that it might have as to the

advantages of concreteness.”

C. The Confession Was Not Obtained Under Inherently

Coercive Circumstances.

The confession here was given after petitioner had been

in custody only 7 hours, and after a period of interroga

tion of only 30 minutes at the most. The case therefore

differs from cases where an accused is subjected to per

sistent and repeated questioning over a period of several,

days, such as Chambers v. Florida, 309 IT. S. 227, 84 L.

Ed. 716 (1940); White v. Texas, 310 IT. S. 530, 84 L. Ed.

1342 (1940); Watts v. Indiana, 338 IT. S. 49, 93 L. Ed.

1801 (1949); Harris v. South Carolina, 338 IT. S. 68, 93

L. Ed. 1815 (1949); Johnson v. Pennsylvania, 340 IT. S.

881, 95 L. Ed. 640 (I960); Culcombe v. Connecticut, 367

19

U. S. 568, 6 L. Ed. 2d 1037 (1961); Fikes v. Alabama,,

352 U. S. 191, 2 L. Ed. 2d 246 (1957). Nor is this a ease

where the accused was questioned for a long period with

out rest or sleep, as in Ashcraft v. Tennessee, 322 U. S. 143,,

88 L. Ed. 1192 (1944). Nor was it a case where the ac

cused was seen to have been suffering from a mental dis

order, as in Fikes v. Alabama, supra; Spano v. New York,

360 U. S. 315, 3 L. Ed. 2d 1265 (1959); Blackburn v.

Alabama, 361 U. S. 199, 4 L. Ed. 2d 242 (1960); Reck v.

Pate, 367 U. S. 433, 6 L. Ed. 2d 948 (1961); Culoombe v.

Connecticut, 367 IT. S. 568, 6 L. Ed. 2d 1037 (1961). Nor

is this a case where the accused was subjected to “ trick

ery” in order to induce a confession, as in Spano v. New

York, supra. There was no threat to bring in members of

the accused’s family and implicate them, as in Culcombe v,

Connecticut, supra. There was no request and denial of

counsel, as in Haynes v. Washington, 373 TJ. S. 503, 10

L. Ed. 2d 513 (1963). The undisputed evidence was that

petitioner was advised that he was entitled to an attorney

and that anything he said could be used against him (R.

97, 99, 120, 220, 224). Sims himself admitted he was ad

vised that any statement he made could be used against:

him (R. 140). While the accused was stripped for pur

poses of examination, the entire undertaking took only 15

minutes (R. 207), and there was no instance of keeping the

accused naked over a 5 or 6 hour period until he confessed,

as in Malinski v. New York, 324 U. S. 401, 89 L. Ed. 1029

(1945). By petitioner’s own sworn testimony, he was not

threatened, he was not afraid, he was not beaten, and he

signed the confession because it was “ right” (R. 136-143).

At the time the confession was signed, petitioner had not

had supper, but he did not testify as to being hungry,

only “ I could have eat” (R. 136), and it appears he had

been in jail only about 4 or 5 hours and had not been in

custody long enough to be fed (R. 111). The arrest oc

curred around 3 P. M. on a Saturday afternoon (R. 137),

when no judge was available for commitment hearing

— 20

(R. 236),1 and hence it is not a case when a prisoner is.

held incommunicado without being carried before a

magistrate.

The case of Fikes v. Alabama, supra, principally relied

upon for the contention that the confessions were obtained

under “ inherently coercive circumstances,” is completely

inapposite. In that case, the accused was subjected to

persistent questioning over the period of a week before he

confessed; there was evidence of mental trouble; prompt

commitment was denied; and efforts of the accused’s

father and an attorney to see him were rebuffed.

Nor are the confessions rendered inadmissible by any

claim of alleged physical mistreatment. Petitioner testified

that while in Dr. Jackson’s office in Folkston, Dr. Jackson

knocked him down, kicked him over the eye, and “drug”

him over the floor by his privates (R. 131).

To begin with, Dr. Jackson denied that he knocked

petitioner down or that he was beat while in his office (R.

204). For purposes of review, the Doctor’s testimony in

the respect must be accepted as true. Haley v. Ohio,

supra (338 U. S. at 52): Gallegos v. Nebraska, supra (342

U. S. at 61); Thomas v. Arizona, 356 U. S. 390, 2 L, Ed. 2d

863 (1958).

It is undisputed that petitioner was treated for a cut

over his eye at the hospital in Folkston (R. 204, 207), but

1 Code § 27-212 referred to in the brief of petitioner (p. 33)

expressly recognizes that officers arresting without a warrant

have a prescribed number of hours in which to carry the

arrested person before an officer for hearing. Prior to the

amendment of these two sections in 1956 (Ga. Laws 1956,

p. 796), the requirement was not qualified by any stated num

ber of hours. Here, however, the warrant for petitioner’s

arrest had been obtained (E. 239), and hence Code §27-212

was not applicable, but rather Code § 27-210, which declares

that the accused should be brought before a magistrate within

72 _ hours of arrest. Under Georgia law, capital offenses are

bailable only before a judge of the superior court. Code

— 21

Dr. Jackson says lie fell in the floor (R. 204). Dr. Jack-

son was extensively cross-examined by counsel for peti

tioner, but there was no effort to question him concerning

the claims that he pulled petitioner by his privates (R.

197-208). No confession was elicited or attempted to be

elicited at the doctor’s office. The sole purpose of this

examination was to ascertain whether there was any blood

on petitioner or his pants, in view of the fact that the

victim was seen to have been in her monthly period (R.

205). None of the officers or other persons who were

present in the doctor’s office were present at the jail when

the confession was made. The petitioner was taken com

pletely away from the scene of the doctor’s office in Folks-

ton, and carried 35 miles to the jail in Waycross, Georgia,

before the matter of any confession was ever discussed.

The written confession was not given until over 7 hours

after the incident in the doctor’s office, in entirely differ

ent surroundings, before entirely different persons, and

without any connecting circumstances whatsoever.

Respondent specifically denies that any violence was

committed on petitioner.2 However, even assuming that

petitioner was struck in the doctor’s office, the decisions

of this Court make plain that this fact alone would not

bar use of confessions later obtained. Lisenba v. Cali

fornia, 314 IT. S. 219, 235, 86 L. Ed. 166 (1941); Lyons v.

Oklahoma, 322 IT. S. 596, 602, 88 L. Ed. 1481 (1944);

Stroble v. California, 343 IT. S. 181, 191, 96 L. Ed. 872

(1952); Thomas v. Arizona, 356 IT. S. 390, 2 L. Ed. 2d

863 (1958). Of course, any confession made “ concur

rently” with physical torture is thereby rendered in

admissible. Stein v. New York, 346 IT. S. 156, 182, 97 L.

Ed. 1522 (1953). “ When this Court is asked to reverse

2 It should be noted that petitioner had been involved in a

wreck just prior to the assault (R. 151) and the struggle be

tween petitioner and the victim appeared to have been a vio

lent one (R. 152, 159, 161, 187, 191).

— 22 —

a state court conviction as wanting in due process, illegal

acts of state officials prior to trial are relevant only as

they bear on petitioner’s contention that he has been de

prived of a fair trial, either through the use of a coerced

confession or otherwise.” Stroble v. California, supra.

‘ ‘ Involuntary confessions, of course, may be given either

simultaneously with or subsequent to unlawful pressure,

force or threats. The question of whether those confes

sions subsequently given are themselves voluntary de

pends on the inferences as to the continuing effect of the

coercive practices which may fairly be drawn from the

surrounding circumstances. The voluntary or involuntary

character of a confession is determined by a conclusion

as to whether the accused, at the time he confesses, is in

possession of mental freedom to confess or deny a sus

pected participation in a crime,” Lyons v. Oklahoma,

supra.

In Thomas v. Arizona, supra, the prisoner was lassoed

under threatening circumstances at the time of his arrest

and again subsequently before being placed in jail. His

confession made the following morning was held not in

validated by the experiences of the day previous, the

Court declaring: “ Deplorable as these ropings are to

the spirit of a civilized administration of justice, the un

disputed facts before us do not show that petitioner’s

oral statement was a product of fear engendered by

them” (356 U. S. at 400).

In Stroble v. California, supra, the accused was ar

rested around noon and while being searched, the police

man kicked his foot to make him stand properly and

then threatened the accused with a black jack. While

awaiting for the police car to arrive, when asked whether

he had committed the crime, accused mumbled something,

whereupon a park foreman standing nearby slapped him.

On the way to the jail, petitioner confessed. Upon arriv

ing at the district attorney’s office a short time later, he

23 -r

again confessed in detail. Rejecting the contention that

the previous violence vitiated the subsequent confessions,

this Court declared:

“ Whatever occurred in the park at the foreman’s

office occurred at least an hour before he began his

confession in the District Attorney’s office, and was

not accompanied by any demand that petitioner im

plicate himself. Likewise his statement to the officer

while on the way to the district attorney’s office was

admittedly voluntary. In the District Attorney’s

office, petitioner answered questions readily; there

was none of the pressure of unrelenting interrogation

which this Court condemned in Watts v. Indiana. . . .

His willingness to confess to the doctors who ex

amined him, after he had been arraigned and counsel

had been appointed, and in circumstances free of

coercion, suggests strongly that petitioner had con

cluded, quite independently of any duress by the

police, ‘ that it was wise to make a clean breast of

his guilt’ ” (343 U. S. at 191).

In Lyons v. Oklahoma, supra, the accused was charged

with the murder of a tenant farmer, his wife and small

child, it being contended that the accused thereafter

burned the house with the bodies in it to conceal the

crime. A pan containing the victims’ bones was placed

in his lap during the questioning which resulted in one

confession. This confession was not sought to be intro

duced against him, but later that day, he was taken to

the state prison where another confession was obtained

which was admitted. In holding that this misconduct on

the part of the officers did not invalidate the second con

fession, the Court said:

“ The Fourteenth Amendment does not protect one

who has admitted his guilt because of forbidden in

ducements against the use at the trial of his subse

quent confessions under all possible circumstances.

The admissibility of the later confession depends upon

the same test—isi it voluntary. The effect of earlier

abuse may be so clear as to forbid any other inference

than that it dominated the mind of the accused to such

an extent that the later confession is involuntary. If

the relation between the earlier and later confession

is not so close that one must say the facts of one con

trol the character of the other, the inference is one for

the triers of fact and their conclusion, in such an un

certain situation, that the confession should be ad

mitted as voluntary, cannot be a denial of due proc

ess” (322 U. S. at 603).

Also pertinent to the facts here, in that petitioner was

removed to entirely different surroundings before the ques

tioned confession was obtained, is the language of this

Court, viz.:

“ It followed the prisoner’s transfer from the control

of the sheriff’s force to that of the warden’s. One

person who had been present during a part of the time

while the Hugo interrogation was in progress was

present at McAlester, it is true, but he was not among

those charged with abusing Lyons during the question

ing at Hugo” (322 U. S. at 604).

In Lisenba v. California, supra, the accused, while in cus

tody on Monday, was slapped by an officer. He confessed

the following day. It was held that use of the confession

was not a denial of due process under these circumstances

(314 U. S. at 240).

In view of the circumstances here—the lack of anything

to connect what transpired in the doctor’s office with the

confession made several hours later—coupled with the tes

timony of the accused at the trial to the effect that he

was not scared or afraid (R. 127-144) it is clear that the

admission of the written confession (R. 226), and the peti

— 25 —

tioner’s confirmation of it several days later (R. 238) did

not amount to a ‘ ‘ failure to observe that fundamental fair

ness essential to the very concept of justice” . Lisenba v.

California, supra (314 U. S. at 236).

D. The Decision Below Does Not Violate Petitioner’s

Sixth Amendment Right to Counsel under Escobedo v. Illi

nois, 378 U. S. 478, 12 L, Ed. 2d 977 (1964).

In Escobedo, the crucial facts were (1) that the accused

was never advised of his right to counsel, and (2) he spe

cifically requested counsel which request was denied.

Here, petitioner was fully advised as to his rights (R. 97,

99, 120, 220, 224), and he expressly declared that he did

not desire an attorney (R. 100, 120, 224).

What was done here came very close to complying with

the requirements of Miranda v. Arizona, 384 U. S. 436, 16

L. Ed. 2d 694 (1966), although that case is not applicable

here. Johnson v. New Jersey, 384 U. S. 719, 16 L. Ed. 2d

882 (1966).

“ The mere fact that a confession was made while in

the custody of the police does not render it inadmis

sible.”

McNabb v. United States, 318 U. 8. 332, 346, 87

L. Ed. 819 (1943).

“ And certainly we do not mean to suggest that all

interrogation of witnesses and suspects is impermis

sible. ’ ’

Haynes v. Washington, 373 U. S. 503, 515, 10

L. Ed. 2d 513 (1963).

And, in Miranda v. Arizona, supra, it was said:

“ An express statement that the individual is willing

to make a statement and does not want an attorney

followed closely by a statement could constitute a

waiver.” 16 L. Ed. 2d at 724.

# #

“ Confessions remain a proper element in law en

forcement” * * *

“ Volunteered statements of any kind are not barred

by the Fifth Amendment and their admissibility is

not affected by our holding today” (16 L. Ed. 2d at

726).

The Court of Appeals for the District of Columbia has

construed Escobedo contrary to that as contended for by

petitioner. See Jackson v . United States, 337 F. 2d 136,

140-141 (C. A. D. C. 1964), cert den. 380 U. S. 935, 13 L. Ed.

2d 822 (1965); Long v. United States, 338 F. 2d 549

(C. A. D. 0. 1964). In the Jackson case, it was said:

“ We conclude that no rule of law required the ex

clusion of this appellant’s confession, voluntarily

made, after he had been warned by the F. B. I., the

police and the United States Commissioner acting pur

suant to Buie 40 (b). He had not requested that coun

sel be appointed; he had retained no lawyer; that one

was not then appointed for him denied him no right;

and as the law now stands, there is no automatic rule

of exclusion which will bar use of such a confession

by an accused who has no lawyer, under circumstances

such as appear on the record before us.”

In Massiah v. United States, 377 U. S. 201, 12 L. Ed. 2d

246 (1964), a federal prosecution subject to the Sixth

Amendment, reliance was placed on the fact that Massiah

was tricked, viz.:

“ In this case, Massiah was more seriously imposed

upon . . . because he did not even know that he was

under interrogation by a government agent” (377

U. S. at 206).

— 26 —

— 27 —

It was further said:

“ Here we deal not with a State Court conviction

but with a federal case, where the specific guarantee of

the Sixth Amendment directly applies” (377 U. S.

at 205).

II.

There Was No Denial of Equal Protection by the

Rulings Below Relating to the Challenges

to the Grand and Petit Juries.

The procedure of jury selection in Georgia as set forth

in the Brief of Petitioner (p. 47) is essentially correct,

except that the jury commissioners select a number of

grand jurors from the persons previously selected as

traverse jurors in a number not to exceed two-fifths of

those selected as traverse (petit) jurors. In other words,

the two-fifth’s figure is applied to the traverse jurors in

selecting the grand jurors, and not to the tax digests in

selecting either, as Petitioner’s brief indicates. Pollard

v. State, 148 Ga. 447 (3), 96 S. E. 997 (1918). It should

also be emphasized that the actual selection of the venires

for each term of court is accomplished by the drawing

of tickets containing the names of jurors from the jury

boxes, Code §§ 59-203, 59-701. The making up of the

panels has nothing to do with the “ jury lists” , which are

merely a recording on the minutes of the Court of the

names in the jury boxes. Code § 59-109.

Petitioner contends (A) That the state courts erred in

denying him the right to adduce evidence relating to the

composition of jury lists in existence prior to the revision

in the summer of 1964. (B) That the selection of the jury

lists from the tax digest, required by law at this time to

list Negro and white taxpayers separately, Code § 92-

6307, constitutes a denial of equal protection, and (C)

That the disproportion between the number of Negroes

on the tax digest and the number on the grand and petit

juries in this case established a prima facie case of dis

crimination.

A. No Error Results From the Action of the Georgia

Courts in Restricting Proof to the Current Jury Lists.

In support of the Plea in Abatement to the indictment

(It. 3) and the challenge to the array of traverse jurors

(R. 6-8) both based upon alleged racial discrimination in

jury selection, counsel for petitioner sought to introduce

grand jury lists for previous years, to wit, 1954, 1956,

1958, 1959, 1960, 1962, 1963 (R. 72-3) and traverse jury

lists for the years 1954, 1958, 1960, 1961, 1963, and 1965

(R. 73). Objection was made to the lists for prior years

on the ground that only the jury lists from which the

juries in this case were drawn would be relevant (R. 70,

73). Ruling was initially reserved (R. 72), but sub

sequently, the Court sustained the objection and ruled

out all jury lists other than the 1965 lists from which the

grand and traverse juries in this case were selected (R.

147). However, the Court accepted these lists by way

of offer of proof (R. 254-298).

However, petitioner made no further offer of proof.

Since the burden is on petitioner to prove discrimination,

Akins v. Texas, 325 U. S. 398, 89 L. Ed. 1692 (1945);

Swain v. Alabama, 380 U. S. 202, 226, 13 L. Ed. 2d 759

(1965); Fay v. New York, 332 U. S. 261, 285, 91 L. Ed.

2043 (1947), it is impossible to tell whether or not there

was any discrimination with respect to these prior lists,

and hence petitioner failed to carry the burden.

However, regardless of this, respondent submits that

even assuming a more complete offer of proof had been

made, and even assuming that such evidence would have

made out a prima facie case of discrimination, the evi

dence as to the 1965 jury lists sufficiently rebuts any in

ference of discrimination.

29 —

It plainly appears that the jury boxes were revised in

the summer of 1964 (R. 76).1 “ Former errors can not

invalidate future trials” . . . . It is this particular box

that is decisive. Brown v. Allen, 344 U. S. 443, 479, 97

L. Ed. 469 (1953). What transpired previously is ir

relevant. Cassell v. Texas, 339 U. S. 282, 94 L. Ed. 839

(1950). As the population of the County is very small—

only 5313 (R. 75)—some member of the Board of Jury

Commissioners was personally familiar with every Negro

taxpayer in the County (R. 78, 84-5, 87). For the year

1963, there were 1548 white taxpayers and 411 Negro

taxpayers in the County—approximately 20% (R. 74).

According to the 1960 Census, there were a total of 2656

persons over 21 years, of which only 728 were Negro (R.

75). For the October Term, 1965, at which petitioner was

tried, there was one Negro on the Grand jury (R. 86)

and at least 4 Negroes on the petit jury list from which

the jury trying petitioner was selected (R. 321).1 2 Of the

691 non-white persons in Charlton County 25 years of

age or older, 302 were functionally illiterate.3 “ [T]here

comes a point where this Court should not be ignorant

as judges of what we know as men,” Watts v. Indiana,

338 U. S. 49, 52, 93 L. Ed. 1801 (1949), and “ We recog

nize the fact that these lists have a higher proportion of

white citizens than of colored, doubtless due to inequality

of educational and economic opportunities.” Brown v.

1 Actually, the revision took place on Sept. 3, 1964, according

to the minutes of Court.

2 The Clerk of Charlton Superior Court advises that there

were a total of 479 names on the 1964 traverse jury list, of

which he is able to recognize at least 58 as being Negroes; and

that on the 1964 grand jury list, there are a total of 147 names,

of which at least 11 are Negroes. Of the 99 jurors summoned

for traverse jury service at the 1964 October Term, 9 Negroes

actually appeared for service.

3 See United States Census of Population 1960, Georgia,

General Social and Economic Characteristics, PC (1) 12 c Ga

p. 334.

30 —

Allen, 344 IT. S. 443, 473, 97 L. Ed. 469 (1953), and see

Swain v. Alabama, supra (380 U. S. at 208). To attempt

to apply statistical formulas, such as petitioner suggests

(Brief p. 58) which assume a complete equality of intel

ligence, education and other qualities necessary for jury

service between the races, in a small rural, agricultural

county like Charlton, is not only erroneous, it is absurd.

There was no effort here to prove that any large number

of Negro taxpayers were qualified for jury service.

In Swain v. Alabama, supra, only two Negroes were on

the grand jury indicting the accused, and eight were on

the panel from which the petit jury was selected, and two

of these were exempt. In holding that this did not make

out a case of discrimination, this Court said:

“ It is wholly obvious that Alabama has not totally

excluded a racial group from either grand or petit

jury panels, as was the case in Norris v. Alabama,

294 U. 8. 587; Hill v. Texas, 316 U. S. 400; Patton v.

Mississippi, 332 U. S. 463; Hernandez v. Texas, 347

IT. S. 475; and Reece v. Georgia, 350 IT. 8. 85. More

over, we do not consider an average of six to eight

Negroes on these panels as constituting forbidden

token inclusion within the meaning of the cases in

this Court, Thomas v. Texas, 212 U. S. 278; Akins v.

Texas, 325 IT. S. 398; Avery v. Georgia, 345 U. S. 559.

Nor do we consider the evidence in this case to make

out a prima facie case of invidious discrimination

under the Fourteenth Amendment.”

In Brown v. Allen, 344 U. 8. 443, 97 L. Ed. 469 (1953),

a challenge was overruled where there was only one Negro

who served on the grand jury, and eight on the panel

from which the petit jury was selected. See also, Billings

ley v. Clayton, 359 F. 2d 13 (C. A. 5th, 1966).

While token inclusion does not satisfy the Constitution,

Brown v. Allen, 344 U. S. 443, 471, 97 L. Ed. 469 (1953);

31

Smith v. Texas, 311 U. S. 128, 130, 85 L. Ed. 84 (1940);

Billingsley v. Clayton, 359 F. 2d 13 (C. A. 5th, 1966), the

mere fact that there are no Negroes on the grand or petit

jury in a given case does not establish discrimination,

Virginia v. Rives, 100 U. S. 313, 25 L. Ed. 667 (1880);

Bush v. Kentucky, 107 U. S. 110, 117, 27 L. Ed. 354 (1883);

Martin v. Texas, 200 U. S. 316, 320, 50 L. Ed. 497 (1906);

Akins v. Texas, supra (325 U. S. at 403); Hoyt v. Florida,

368 U. S. 57, 7 L. Ed. 2d (1961); Fay v. New York, 332

U. S. 261, 285, 91 L. Ed. 2043 (1947), for “ Circumstances

or chance may well dictate that no persons in a certain

class will serve on a particular jury.” Hoyt v. Florida,

supra. An accused is not entitled to demand proportional

representation of his race on the jury in his case. Thomas

v. Texas, 212 U. S. 278, 53 L. Ed. 512 (1909); Akins v.

Texas, supra; Swain v. Alabama, supra (380 U. 8. at 208);

Fay v. New York, supra (332 U. S. at 291); Cassell v.

Texas, 339 U. 8. 282, 291, 94 L. Ed. 839 (1950); United

States ex rel. Goldsby v. Harpole, 263 F. 2d 71 (C. A. 5th,

1959), cert. den. 361 U. S. 838; United States ex rel. Seals

v. Wiman, 304 F. 2d 53 (C. A. 4th, 1962), cert. den. 372

U. S. 924; Scott v. Walker, 358 F. 2d 56 (C. A. 5th, 1966);

Billingsley v. Clayton, 359 F. 2d 13 (C. A. 5th, 1966).

Indeed, he is not even entitled to demand that any mem

ber of his race serve. Strauder v. West Virginia, 100

U. S. 303, 305, 25 L. Ed. 664 (1880); Virginia v. Rives, 100

U. S. 313, 25 L. Ed. 667 (1880); Neal v. Delaware, 103

U. S. 370, 26 L. Ed. 567 (1881); Bush v. Kentucky, supra;

Wood v. Brush, 140 U. S. 278, 285, 35 L. Ed. 505 (1891);

Jugiro v. Brush, 140 U. S. 291, 297, 35 L. Ed. 510 (1891);

Akins v. Texas, supra.

B. The Use by the Jury Commissioners of the Tax

Digest, Required by Law to List Negro Taxpayers Sepa

rately, Shows No Violation of the Constitution.

Georgia law requires that jurors be selected from the

books of the tax receiver. Code § 59-106. In this case,

— 32 —

the jury commissioners utilized the tax digests, as dis

tinguished from the individual tax return sheets4 (R. 77).

Prior to 1966, Code §92-6307 provided in part:

“ Names of colored and white taxpayers shall he

made out separately on the tax digest.”

This provision was repealed in 1966 (Ga. Laws 1966,

Vol. I, p. 393).

When the jury boxes in question in this case were pre

pared, however, the tax digests were kept separate, and

it is this fact, coupled with the requirement that the jury

lists be made from the tax records, that petitioner assails

as being unconstitutional, relying upon Avery v. Georgia,

345 U. S. 559, 97 L. Ed. 1244 (1953).

A similar contention was rejected in Maxwell v. Stevens,

348 F. 2d 325 (C. A. 8th, 1965); Harris v. Stephens, 361

F. 2d 888, 892 (C. A. 8th, 1966); and Brookins v. State,

221 Ga. 181, 144 S. E. 2d 83 (1965).

The validity of Code § 92-6307 if attacked in a direct

proceeding by way of injunction is not at issue here. See

Anderson v. Martin, 375 U. S. 833, 11 L. Ed. 2d 439 (1964);

Hamm v. Virginia State Board of Elections, 230 F. Supp.

156 (D. C. Va. 1964), aff’d sub nom. Tancil v. Woolls, 379

TJ. S. 19, 13 L. Ed. 2d 91 (1964). The question is whether

under the facts of this case, the practice is seen to be

harmful, for harmless error is no ground for complaint.

Cf. Rule 61, Fed. Rules Civ. Proc.

In Avery v. Georgia, supra, and in Williams v. Georgia,

349 U. S. 375, 99 L. Ed. 1161 (1955), this Court held that

4 Prior to 1965, the tax return sheets furnished by the State

Revenue Department (Code § 92-6302) to all counties were yellow

for Negro taxpayers and white for white taxpayers (R. 78).

However, this practice was discontinued in 1965, and in any

event, since the tax return sheets were not used in this case,

this is constitutionally irrelevant.

33

the placing of the names of white and Negro jurors in the

jury box on different colored slips of paper was such error

as would require a new trial, where seasonably challenged,

on the reasoning that,

“ Even if the white and yellow tickets were drawn

from the jury box without discrimination, opportunity

was available to resort to it at other stages in the

selection process. And, in view of the case before us,

where not a single Negro was selected to serve on a

panel of sixty—though many were available, we think

that petitioner has certainly established a prima facie

case of discrimination.” Avery v. Georgia, supra

(345 U. S. at 562).

The determinative factor in Avery is the crucial stage

at which the different colored slips afforded an oppor

tunity for discrimination. The slips are placed in the box

to serve the function of affording a fair and impartial

means of selecting the venires through the chance draw

ing of names for each term of court. This procedure by

its nature is designed to be so conducted as to eliminate

the element of conscious choice in the selection process.

It takes place at the critical point when each panel for

the coming term of court is in the actual process of being

made up. Any distinguishing marks therefore tend to

destroy the very element of chance which the drawing of

names from a box is designed to achieve. As pointed out

by Mr. Justice Frankfurter’s concurring opinion in Avery,

the openings in the jury boxes were of sufficient size to

enable the judge drawing the slips to distinguish their

color. 345 U. 8. at 564. In other words, the different

colored slips injected “ color” where it was peculiarly

important that the selection process be color blind.

Such is not the case here, for the difference is between

selecting the jury rolls, and selecting the venires. With

34 —

respect to the former, involved in this case, the decisions

of this Court place an affirmative duty on jury commis

sioners to consider race, for in no other way can they be

sure that the jury consists of a cross-section of the com

munity :

‘ ‘ What the Fourteenth Amendment prohibits is

racial discrimination in the selection of grand juries.

Where jury commissioners limit those from whom

grand juries are selected to their own personal ac

quaintances, discrimination can arise from commis

sioners who know no Negroes as well as from com

missioners who know but eliminate them.” Smith v.

Texas, 311 U. S. 128, 132, 85 L. Ed. 84 (1940).

And, in Hill v. Texas, 316 U. S. 400, 404, 86 L. Ed. 1559

(1942), this Court declared that it was the duty of jury

commissioners imposed by Section 4 of the Civil Eights

Act of 1875, to make an ‘ ‘ effort to ascertain whether there

were within the County members of the colored race

qualified to serve as jurors, and if so, who they were.”

In Cassell v. Texas, 339 U. S. 282, 94 L. Ed. 839 (1950),

convictions were reversed because of failure of the jury

commissioners to acquaint themselves with Negroes in the

County in order to ascertain their qualifications. See also

Eubanks v. Louisiana, 356 U. S. 584, 2 L. Ed. 2d 991

(1958); and United States ex rel. Seals v. Wiman, 304 F.

2d 53 (C. A. 5th 1962), cert. den. 372 U. S. 924 (1963).

See also, Woods v. State, 222 Ga. 321, . . . S. E. 2d . . .

(1966).

Just recently, the Fifth Circuit alluded to this fact in

Brooks v. Beto, . . . F. 2d . . . , 35 L. W. 2077 (July 29,

1966), where it was said that “ How then can it be

said that conscientiously to do what the Constitution de

mands makes the result bad because race had been con

sciously considered to assure that race has not been the

basis of discrimination?”

— 35

Moreover, any racial differentiation appearing on the