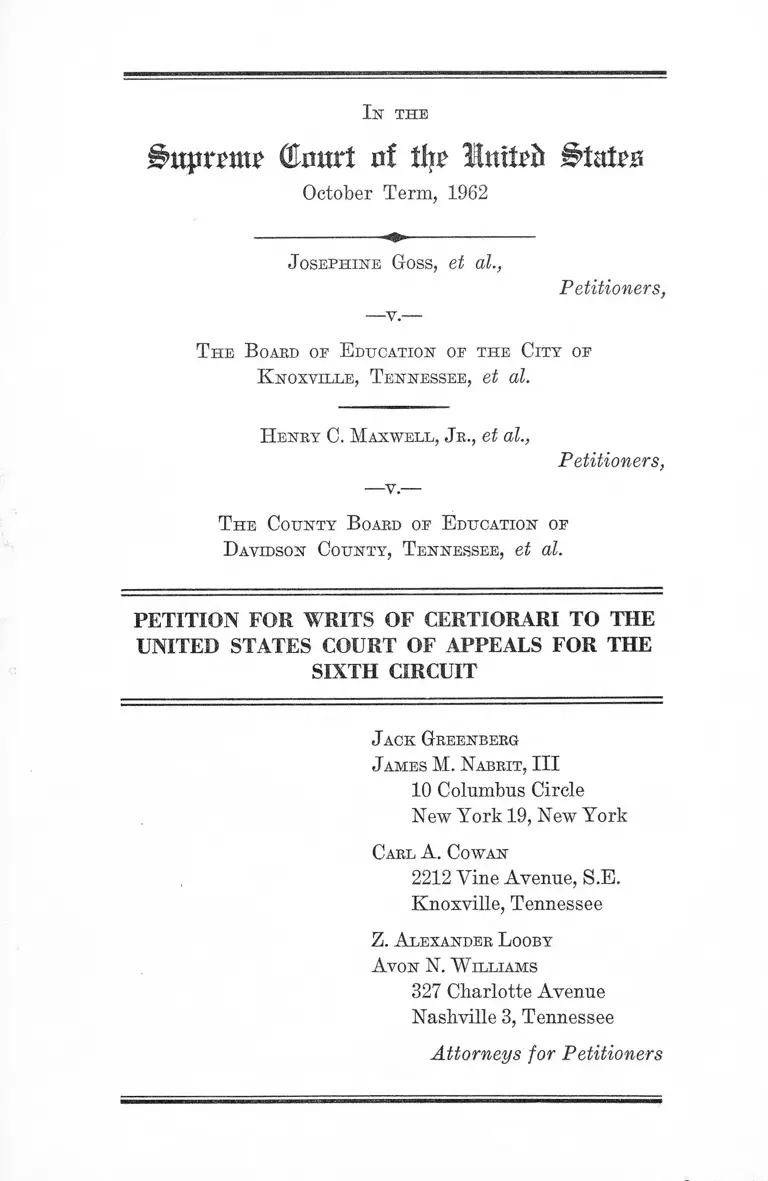

Goss v. Knoxville, TN Board of Education Petition for Writs of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1962

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Goss v. Knoxville, TN Board of Education Petition for Writs of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit, 1962. 0254acf0-b39a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/be30bc30-8290-4087-ba5f-86b23e1c0225/goss-v-knoxville-tn-board-of-education-petition-for-writs-of-certiorari-to-the-us-court-of-appeals-for-the-sixth-circuit. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

Isr t h e

j^ttpran? Okmrt of % llnxUb

October Term, 1962

J osephine Goss, et al.,

Petitioners,

—v .—

T i-ie Board oe E ducation op the City of

K noxville, Tennessee, et al.

H enby C. Maxwell, J r., et al.,

Petitioners,

T he County B oard of E ducation of

Davidson County, T ennessee, et al.

PETITION FOR WRITS OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE

SIXTH CIRCUIT

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, III

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Carl A. Cowan

2212 Vine Avenue, S.E.

Knoxville, Tennessee

Z. Alexander L ooby

Avon N. W illiams

327 Charlotte Avenue

Nashville 3, Tennessee

Attorneys for Petitioners

I N D E X

Citation to Opinions Below ................................ 1

Jurisdiction ................................................................ 2

Questions Presented .................................................. 2

Constitutional Provision Involved .............................. 3

Statement .................................................................... 3

Evidence and Holdings:

PAGE

Goss case ..................................................... 7

Maxwell case ........................ ....................... H

Reasons for Granting the Writs

I. With regard to the racial transfer plan,

there is a conflict among the circuits, the

decisions below are in conflict with princi

ples established by this Court, and the issue

is of widespread importance........................ 15

II. The decision below in the Maxwell case deny

ing injunctive relief to three Negro plaintiffs

who sought admission to white schools in

grades not reached by the plan is in conflict

with principles established by this Court and

is of public importance ................................ 22

Conclusion............................................................................ 26

Appendix A

Opinions and Judgments in Goss ease.............. la

Appendix B

Opinions and Judgments in Maxwell case ........ 37a

11

Table of Cases

Board of Education v. Groves, 261 F. 2d 527 (4th

Cir. 1958) ................................................................ 24

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U. S. 497 ................................ 19

Boson v. Rippy, 285 F. 2d 43 (5th Cir. 1960) ....15,16,19, 20

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483; 349

IT. S. 294 .........................................................4,19, 20, 21,

22, 23, 25

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 60 ............................ 23

Carson v. Warliek, 238 F. 2d 724 (4th Cir. 1956) ___ 16

Clemons v. Board of Education, 228 F. 2d 853 (6th

Cir. 1956) ................................................................ 24

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1 ................................20, 21, 23

Dillard v. School Board of City of Charlottesville,

Va., 4th Cir. No. 8638 ............................................. 21

Dove v. Parham, 271 F. 2d 132 (8th Cir. 1959) ...... 16

Evans v. Ennis, 281 F. 2d 385 (3rd Cir. 1960) .......... 24

Green v. School Board of the City of Roanoke, Va.,

----- F. 2 d ------ (4th Cir. No. 8534, May 22, 1962) 17

Hirabayashi v. United States, 320 U. S. 81 .............. 19

Jackson v. School Board of City of Lynchburg, Va.,

201 F. Supp. 620 (W. D. Va. 1961) ........................

Jackson v. School Board of City of Lynchburg, Va.,

203 F. Supp. 701 (W. D. Va. 1962) ........................

Jones v. School Board of City of Alexandria, 278 F.

2d 72 (4th Cir. 1960) ..............................................

Kelley v. Board of Education of Nashville, 270 F. 2d

PAGE

209 (6th Cir. 1959) .............................................. 10,15, 20

Korematsu v. United States, 323 U. S. 214.............. 19

24

21

17

Ill

Mannings v. Board of Public Instruction, 277 F. 2d

370 (5th Cir. 1960) .................................................. 17

Mapp y. Board of Education of City of Chattanooga,

Tenn., 203 F. Supp. 843 (E. D. Tenn. 1962) .......... 20

Marsh v. Comity School Board of Roanoke County,

Y a.,-----F. 2 d ------ (4th Cir. No. 8535, June 12,

1962) ....................................................................... 17, 23

Moore v. Board of Education, 252 F. 2d 291 (4th Cir.

1958) ......................................................................... 24

Norwood v. Tucker, 287 F. 2d 798 (8th Cir. 1961) .... 17

Pettit v. Board of Education, 184 F. Supp. 452 (D.

Md. 1960) ................ 24

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1 ................................ 18, 23

Shuttlesworth v. Birmingham Board of Education,

162 F. Supp. 372 (N. D. Ala. 1958), aff’d on limited

grounds, 358 U. S. 101 ........................................ 16

Sipuel v. Board of Regents, 332 U. S. 631 .................. 23

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629 ................................ 23

Taylor v. Board of Education of City of New Ro

chelle, 191 F. Supp. 181; 195 F. Supp. 231 (S. D.

N. Y. 1961), app. dismissed 288 F. 2d 600, aff’d 294

F. 2d 36 (2nd Cir. 1961), cert. den. 368 U. S. 940 .... 18

Thompson v. County School Board of Arlington

County, Va., unreported (E. I). Va. March 1, 1962)

(excerpts in 30 U. S. Law Week 2446) ................. 21

Statutes and Other Authority

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, Rule 23(a)(3) .... 4

United States Code, Title 28, §1254(1) ..................... 2

United States Code, Title 28, §§1331, 1343, 2201, 2202 4

United States Code, Title 42, §§1981, 1983 .............. 4

Southern School News, May 1962 ............................ 21, 22

PAGE

I n the

dm trt af tlip luitpft States

October Term, 1962

----------------^ ---------------

J osephine Goss, et al.,

Petitioners,

—v.—

T he Board of E ducation of the City of

K noxville, Tennessee, et al.

H enry C. Maxwell, J r., et al.,

Petitioners,

—v.—

T he County B oard of E ducation of

Davidson County, T ennessee, et al.

PETITION FOR WRITS OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE

SIXTH CIRCUIT

Petitioners pray that writs of certiorari issue to review

the judgment of the United States Court of Appeals for

the Sixth Circuit, entered in the Goss case, on April 3,

1962, and the judgment of that Court entered in the Maxwell

case on April 4,1962.

Citation to Opinions Below

1. Goss case. The memorandum opinion of the United

States District Court for the Eastern District of Tennessee

(R. Goss 326a) reported at 186 F. Supp. 559, is printed in

2

the appendix hereto, infra p. la. The opinion of the United

States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit, printed in

the appendix hereto, infra p. 26a, is reported in 301 F. 2d

164 (6th Cir. 1962).

2. Maxwell case. The first Findings of Fact, Conclusions

of Law and Judgment of the United States District Court

for the Middle District of Tennessee (R. Maxwell 114a),

reported at 203 F. Supp. 768, is printed in the appendix

hereto, infra p. 37a. The second Findings of Fact, Conclu

sions of Law and Judgment of that court (R. Maxwell

171a) is unreported and is printed in the appendix hereto,

infra p. 57a. The opinion of the United States Court of Ap

peals for the Sixth Circuit, printed in the appendix hereto,

infra p. 63a, is reported in 301 F. 2d 828 (6th Cir. 1962).

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Court of Appeals in the Goss case

was entered on April 3, 1962 (R. Goss, unnumbered page

preceding opinion; appendix, infra p. 35a). The judgment

of the Court of Appeals in the Maxwell case was entered on

April 4, 1962 (R. Maxwell, unnumbered page preceding

opinion; appendix, infra p. 67a). The jurisdiction of this

Court is invoked under 28 U. S. C. §1254(1).

Questions Presented

I.

Whether petitioners, Negro school children seeking de

segregation of the public school systems of Knoxville,

Tennessee (Goss case), and Davidson County, Tennessee

(.Maxwell case), are deprived of rights under the Four

teenth Amendment by judicial approval of a provision in

desegregation plans adopted by their local school boards,

3

which expressly recognizes race as a ground for transfer

between schools in circumstances where such transfers op

erate to preserve the pre-existing racially segregated sys

tem, and which operate to restrict Negroes living in the

zones of all-Negro schools to such schools while permitting

white children in such areas to transfer to other schools

solely on the basis of race.

II.

Whether the personal constitutional rights of three Negro

plaintiffs in the Maxwell case were violated, where the courts

below approved a desegregation plan for the school system

which does not provide any nonsegregated education for

these pupils at any time, and the courts refused to order

their admission at all-white schools from which they had

been excluded because of race, even though the school

authorities made no showing of relevant administrative

obstacles to their admission.

Constitutional Provision Involved

This case involves Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the Constitution of the United States.

Statement

These two eases involve the desegregation of the public

schools of the City of Knoxville, Tennessee, and of David

son County, Tennessee, an area adjacent to the City of

Nashville. This single petition for two cases is filed under

this Court’s Rule 23(5) as the cases present an identical

issue, e.g., the validity of identical provisions in desegrega

tion plans adopted by the two school boards and approved

by the courts below. The Maxwell or Davidson County case

presents an additional issue relating to the denial of indi

vidual injunctive relief to certain of the Negro plaintiffs.

4

Both cases were brought by Negro public school pupils

and their parents as class actions under Buie 23(a)(3),

F. B. C. P., against the local school authorities seeking

injunctive and declaratory relief to obtain desegregation in

accordance with Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S.

483; 349 U. S. 294.1 In each case, jurisdiction of the District

Court was invoked pursuant to 28 U. S. C., §§1331, 1343,

2201 and 2202, and 42 U. S. C., §§1981 and 1983, the cases

involving alleged denials of rights under the Fourteenth

Amendment. In both cases the school authorities acknowl

edged by their answers that they were continuing to operate

racially segregated public school systems. After directions

from the trial courts to present desegregation plans (B.

Goss 36a; B. Maxwell 62a), both boards adopted plans to

desegregate one school grade each year over a twelve year

period, beginning with the first grade, in 1960 in Knoxville

and in 1961 in Davidson County. (For text of plans see:

B. Goss 38a; Maxwell 39a.) While there were differences

in wording, the two plans were substantially the same.

Both contained provisions for rezoning of schools without

reference to race, and for a system of transfers.

The transfer rule, which is at issue on this petition,

provided that pupils could obtain transfers from the schools

in their zones of residence to other schools upon request

in certain cases. The Knoxville plan provided:

6. The following will be regarded as some of the valid

conditions to support requests for transfer:

a. When a white student would otherwise be re

quired to attend a school previously serving colored

students only;

1 The Goss case was filed December 11, 1959 in the District Court

for the Eastern District of Tennessee (R. Goss 5a). Maxwell was

filed September 19, 1960 in the Middle District of Tennessee

(R. Maxwell 7a).

5

b. When a colored student would otherwise be re

quired to attend a school previously serving white

students only ;

c. When a student would otherwise be required to

attend a school where the majority of students of

that school or in his or her grade are of a different

race (R. Goss 40a).

The transfer provision adopted by Davidson County was

the same except for one or two words not affecting the

meaning (R. Maxwell 70a).

Plaintiffs filed written objections to both plans including

specific objections to the above-quoted transfer rule (R.

Goss 41a-43a; R. Maxwell 72a-76a). The District Courts

in both cases held hearings to consider the adequacy of

the plans at which the parties presented evidence.

In the Goss case, the District Court found the plan ac

ceptable and approved it in all respects, except that it

required the school board to re-study and re-submit a plan

relating to an all-white vocational school offering technical

courses not available to Negro students. On plaintiffs’

appeal to the Sixth Circuit in the Goss case, the Court of

Appeals modified this judgment “insofar as it approved the

board’s plan for continued segregation of all grades not

reached by its grade a year plan,” and remanded, instruct

ing the District Court “to require the board to promptly

submit an amended and realistic plan for the acceleration

of desegregation” (301 F. 2d at 169). Thus, the Court

sustained one of plaintiffs’ arguments saying the “evidence

does not indicate that the board is confronted with the type

of administrative problems contemplated by the Supreme

Court in the second Brown decision” (301 F. 2d at 167).

The court affirmed the approval of the plan as to the other

features, including the transfer provision, stating that this

6

approval was “subject to it being used for proper school

administrative purposes and not for perpetuation of segre

gation” (301 F. 2d at 168). Plaintiffs’ requests for indi

vidual injunctive relief requiring their admission in certain

white schools were disposed of by the statement that the

request was moot as to some pupils who had graduated

from school, and that after the school board complied with

the Court of Appeals’ order to accelerate desegregation,

this question might become moot as to the others (301 F.

2d at 168). As indicated above, petitioners in the Goss

case seek review of the Sixth Circuit’s decision only as to

its approval of the racial transfer plan.

In the Maxwell case the District Court disapproved the

school board’s twelve year plan and modified it to require

that the first four grades be desegregated as of January

1, 1961, with an additional grade to be desegregated each

September thereafter until all grades were covered. The

District Court approved the racial transfer provision and

also refused injunctive relief to several plaintiffs who

sought admission to white schools nearer their homes as

exceptions to the plan in higher grades that were still segre

gated. On plaintiffs’ appeal involving these last mentioned

two issues, the Sixth Circuit affirmed the approval of the

transfer plan and the denial of injunctive relief as to three

plaintiffs who sought individual admissions. Petitioners

seek review here of both issues decided by the Court of

Appeals in the Maxwell case.

Evidence and Holdings:

Goss Case

7

The major part of the testimony in the record relates to

the issue presented by the request for a twelve year delay

in desegregation, and since no review of the Sixth Circuit’s

action on this matter is sought, this factual summary is

limited to matters bearing on the transfer plan. The evi

dence touching on the transfer plan consisted of testimony

by school board members as to its meaning, their under

standing of its likely effect, and the reasons for the plan.

There was also testimony by a school administrator as to

prior transfer procedures, and several affidavits and ex

hibits were filed by plaintiffs in support of their motion

for new trial which reflect school board action establishing

transfer procedures after the trial court’s approval of the

plan.

The school board president, Dr. Burkhart, testified that

the provision for transfers based on race was adopted out

of concern for “the orderly education of our students, both

white and colored, in an effort to make available to the

community the best facilities and instructional facilities

that we can under the least possible circumstance which

might be harmful” (R. Goss 108a); that the board thought

it might be “harmful” to a certain number of white students

to go to school with Negroes and also “it might be harmful

to some of the colored students to go with white students

if they did not want to” (R. Goss 108a). He said the basis

for this feeling was:

The fact that we are talking about two separate races

of people, with different physical characteristics, who

have not in our community been very closely associated

in many ways, and certainly not in school ways. And

8

there would be a sudden throwing together of these

two races which are not accustomed to that sort of

thing. Either one of them might suffer from it unless

we took some steps to try to decrease that amount of

suffering or that contact which might lead to that in

case it did occur (R. Goss 108a).

The witness stated that he did not necessarily refer to

physical harm but was more concerned with “mental harm”

(R. Goss 109a). With regard to the expected operation of

the transfer rule, the school board president testified that

he did not know the mechanics as to how pupils would be

notified of their new school zones (R. Goss 115a). He

further testified:

Q. I am asking you do you or does the board antici

pate that any white students will remain in schools

which have been previously zoned or used for Negroes

exclusively? A. We doubt that they will.

Q. As a matter of fact, none have remained in the

City of Nashville, have they? A. I don’t know. All

I can do to keep up with the City of Knoxville.

Q. So then a Negro student who happens to be in a

zone where the school for his zone is a school which was

formerly used by Negroes only, that school will be

continued to be used for Negroes only and he will re

main in a segregated school, will he not? A. Yes, sir.

Q. And if he applied for transfer out of his zone to

a school which had been formerly serving white stu

dents only, then his application would be denied under

this plan, would it not, sir? A. Unless it were based

on one of the other reasons that we have established

for transfer. If transferred under one of those, it

would be granted.

# # * # #

9

Q. But a white student to transfer out of a Negro

school, as you have stated, would be entitled to do so,

to have his application granted as a matter of course

under paragraph 6, subparagraph “a” or “e” of this

plan? A. Yes, sir (K. Goss 118a).

Another board member, Dr. Moffett, acknowledged that

the transfer provisions “at least give the opportunity” to

perpetuate segregation insofar as they are availed of by

the students or parents (R. Goss 205a).

Mr. Marable, a school administrator in charge of handling

transfer requests, stated that under the system used before

this plan was approved, when parents request transfers he

investigates the requests and gets the views of the princi

pals concerned and determines if the family has a “valid

reason” (R. Goss 264a-265a); that the school board “leaves

that up to me,” {Ibid. ) ; that he did not know what the

board’s written rules on transfer provided {Ibid. ) ; that

“I just know I have handled it so many years on my own,

and so far I haven’t stuck my neck out on it” (R. Goss 266a);

“that each case is individual. That has to be handled that

way. Could not have a rule” (266a); that an example of a

“valid” reason would be where a child’s mother taught at

a school and wanted the child with her because she had no

where to leave it and the school had room and the principal

agreed (R. Goss 267a); that generally transfers were

granted for “hardship cases and convenience” (R. Goss

267a).

After the trial court approved the plan, the school board

adopted a resolution providing for administration of the

provisions as follows: “All first grade pupils should either

enroll in the elementary school within their new school zone

or in the school which they would have previously attended”

(R. Goss 350, 352a).

10

The District Court opinion did not discuss the transfer

plan issue in its memorandum opinion, although during the

trial the court indicated that it regarded itself as bound by

the Sixth Circuit’s prior approval of an almost identical

provision in the Nashville, Tennessee school case (R. Goss

119a). See Kelley v. Board of Education of Nashville, 270

F. 2d 209, 228 (6th Cir. 1959).

The Court of Appeals’ holding with respect to the transfer

plan in the Goss case was as follows:

The transfer feature of the plan comes under sharp

criticism of the plaintiffs. They claim that the opera

tion of such a plan will perpetuate segregation. We do

not think the transfer provision is in and of itself ille

gal or unconstitutional. It is the use and application of

it that may become a violation of constitutional rights.

It is in the same category as the pupil assignment laws.

They are not inherently unconstitutional. Shuttles-

worth v. Birmingham Board of Education, 162 F. Supp.

372, D. C. N. D. Ala., affirmed, 358 U. S. 101, 79 S. Ct.

221, 3 L. Ed. 2d 145. They may serve as an aid to

proper school administration. A similar transfer plan

was approved by this Court in Kelley v. Board of Edu

cation of City of Nashville, 270 F. 2d 209, C. A. 6, cert,

denied, 361 U. S. 924, 80 S. Ct. 293, 4 L. Ed. 2d 240.

We adhere to our former ruling with the admonition

to the board that it cannot use this as a means to per

petuate segregation. In Boson v. Rippy, supra, the

court said, 285 F. 2d at p. 46, the transfer feature

“should be stricken because its provisions recognize

race as an absolute ground for the transfer of students,

and its application might tend to perpetuate racial dis

crimination.” (Emphasis added.) This transfer pro

vision functions only on request and rests with the

students or their parents and not with the board. The

11

trial judge retains jurisdiction during the transition

period and the supervision of this phase of the reor

ganization may be safely left in his hands (301 F. 2d

164,168).

Maxwell Case

With regard to the transfer plan, the Superintendent of

Schools agreed that the effect of the rule is to permit a

child or his parents “to choose segregation outside his zone

but not to choose integration outside of his zone” (E. Max

well 91a); that the provision was identical to that in the

Nashville plan; and that as it operated in Nashville and was

intended to operate in Davidson County, white pupils were

not actually required to first go to the Negro schools in

their zones and then seek transfers out, and no Negro pupils

who did not affirmatively seek a transfer to an integrated

school were assigned to one (E. Maxwell 91a-92a).

Dr. Eugene Weinstein, a professor at Vanderbilt Univer

sity in Nashville, testified about a survey of the attitudes

of Negro parents in Nashville who had a choice of whether

to send their children to desegregated schools. He indi

cated that the most frequent factor influencing those who

did not send their children to white schools was an unwill

ingness to separate several children in a family where they

had older children not eligible for desegregation under the

grade a year plan. He said the experience in Nashville in

dicated “mass paper transfers of Whites back into what is

historically the White school, of Negroes remaining in what

is historically the Negro school” ; and that the transfer pro

visions tend to keep the system oriented toward a segre

gated system with token desegregation (E. Maxwell 101a-

102a).

Six of the plaintiffs in this case reside nearer to all-Negro

schools than to white schools (E. Maxwell, 116a-Finding

No. 5).

12

At a further hearing held on plaintiffs’ motions following

the initial approval of the plan with modifications, the evi

dence indicated that under the new zones adopted under the

plan, in the first four grades, there were 288 white children

in the Negro school zones and 405 Negro children in the

zones of the white schools (R. Maxwell 150a). The school

authorities sent notices to the parents of these children ask

ing them to indicate within three days whether they re

quested permission for the children to stay at the school

presentely attended or requested permission for a “trans

fer” to the newly zoned school (R. Maxwell 142a-145a). Of

this group, only fifty-one pupils, all of them Negroes, asked

to attend the school in the new zones (R. Maxwell 165a).

As previously indicated the District Court approved the

transfer feature of the plan (R. Maxwell 131a-132a). On

appeal the Sixth Circuit also approved this provision on the

authority of its decision in Goss (301 F. 2d at 829).

Three of the Negro plaintiffs (Henry C. Maxwell, Jr.,

Benjamin G. Maxwell and Deborah Ruth Clark) pressed

their claims for individual injunctive relief in both courts

below. In the trial court they sought this relief by motion

for preliminary injunction, at the trial and by post trial

motions for new trial and other appropriate relief. Relief

was denied on each occasion.

The trial court found on undisputed evidence that these

children (among others) had applied to certain white

schools for the September 1960 term, that they were re

fused admission solely on account of their race or color and

that if they had been white children they would have been

admitted to the white schools to which they applied (R.

Maxwell 115a-116a, Finding No. 4). The Superintendent

indicated that admission of these pupils who sought in

dividual relief (there were six originally) would not have

caused any great administrative problems (R. Maxwell 53a),

13

and that: “I wouldn’t say there wouldn’t be any administra

tive problem. If we had our children and teachers ready

to accept them, maybe there wouldn’t be too much of a prob

lem” (R. Maxwell 54a). When asked what administrative

problems their admission would create, the Superintendent

mentioned only “friction” and the possibility of “bloodshed”

or “fights” (R. Maxwell 54a, 56a~60a), based upon his read

ing of what occurred in Little Rock (R. Maxwell 57a, 93a-

94a). He stated that these children could be accommodated

“as far as room is concerned” but that he couldn’t accept

them without accepting all who might apply (R. Maxwell

82a).

The Court denied plaintiffs’ request that they be admitted

as exceptions to the plan stating in its second opinion dated

January 24, 1961 (R. Maxwell 173a):

With respect to the request of the four individual

plaintiffs, Cleophus Driver, Deborah Ruth Clark,

Henry C. Maxwell, Jr. and Benjamin Grover Maxwell,

to be admitted to schools as exception to said desegre

gation plan, the Court is of the opinion that to grant

such exceptions would be in effect to invite the destruc

tion of the very plan which the Court has held is for the

best interest of the school system of Davidson County.

It is not a plan which is designed to deny the constitu

tional rights of anyone. It is a plan which is designed

to effect an orderly, harmonious, and effective transi

tion from a racially segregated system to a racially

non-segregated system of schools, taking into account

the conditions existing in this particular locality. And

the Court cannot see how these individual plaintiffs

who brought this action are or would be entitled to any

different treatment from any other children who attend

the schools of Davidson County and are members of the

class represented by the plaintiffs.

14

The Court of Appeals affirmed stating at 301 F. 2d 829:

The same questions were decided in our opinion in

Goss et al. v. Board of Education of City of Knoxville,

et ah, 6 Cir., 1962, 301 F. 2d 164.

In that case we said, on the first question: “As pre

viously indicated, we think the Supreme Court contem

plated that there would have to be plans for the transi

tion and that some individual rights would have to be

subordinated for the good of many. The smooth work

ing of a plan could be thwarted by a multiplicity of

suits by individuals seeking admission to grades not

yet reached in the desegregation plan.”

In Goss, supra at 301 F. 2d 168, the Court had gone on to

state:

We think Judge Taylor was correct in denying in

junctive relief and as he so eloquently said: “Some

individuals, parties to this case, will not themselves

benefit from the transition. At a turning point in his

tory some, by the accidents of fate, move on to the new

order. Others, by the same fate, may not. If the transi

tion is made successfully, these plaintiffs will have had

a part. Moses saw the land of Judah from Mount

Pisgah, though he himself was never to set foot there.”

See also the opinion of Novem ber 23, 1960 (R. Maxwell

131a).

15

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRITS

I

With regard to the racial transfer plan, there is a

conflict among the circuits, the decisions below are in

conflict with principles established by this Court, and

the issue is of widespread importance.

There is a clear and direct conflict between the opinion

of the Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit in Boson v.

Rippy, 285 F. 2d 43 (5th Cir. 1960) and the opinions of the

Sixth Circuit in the Goss and Maxwell cases as well as that

court’s opinion in Kelley v. Board of Education of City of

Nashville, 270 F. 2d 209 (6th Cir. 1959), cert, den. 361 U. S.

924. In the Boson case the Fifth Circuit held that an iden

tical transfer provision was unconstitutional, and expressly

recognized that its holding was in conflict with the Kelley

case, supra, stating:

We fully recognize the practicality of the argument

contained in the opinion of the Sixth Circuit holding

that similar provisions are not unconstitutional.

# # # # *

Nevertheless with deference to the views of the Sixth

Circuit, it seems to us that classification according to

race for purposes of transfer is hardly less unconstitu

tional than such classification for purposes of original

assignment to a public school (285 F. 2d at 48).

The Fifth Circuit went on to say that “the transfer fea

ture should be stricken because its provisions recognize race

as an absolute ground for transfer of students, and its ap

plication might tend to perpetuate racial discrimination”

(Ibid, at 47). In the Goss opinion 301 F. 2d at 168), the

16

court, after emphasizing the word “might” in the last quoted

passage, went on to mention the fact that the transfer pro

vision functions only on request and rests with the students

or parents, and said that the matter might be safely left in

the hands of the trial judge. Petitioners submit that this is

no distinction at all between the Goss case and Boson v.

Rippy, supra, for in Boson also the transfer provision func

tioned only at parents’ request and the court was required

to retain jurisdiction. The Sixth Circuit’s qualification of its

approval of the plan affords no ascertainable safeguards.

The Court states that its approval is “subject to its being

used for proper school administrative purposes and not for

perpetuation of segregation.” But the court did not indicate

how racial transfers might be used for proper administra

tive purposes, or how the plan could operate other than to

perpetuate segregation. Perhaps this puzzling reference is

to the perpetuation of complete racial segregation in the

entire school system. In any event it is self evident that to

the extent that the transfer rule is availed of by parents it

will work to preserve the pre-existing pattern of segrega

tion. Obviously transfers of white children from Negro to

white schools, and of Negro children from white to Negro

schools, will have this effect. It is equally clear that the

plan does not provide for transfers on the basis of race to

promote desegregation.

Similarly the Sixth Circuit’s comparison of this provi

sion with pupil assignment laws which are “not inherently

unconstitutional” but may be applied so as to “become a

violation of constitutional rights” is not apt. The pupil

assignment laws upheld in such cases as Sh-uttlesworth v.

Birmingham Board of Education, 162 F. Supp. 372 (N. D.

Ala. 1958), affirmed on limited grounds, 358 U. S. 101; Dove

v. Parham, 271 F. 2d 132 (8th Cir. 1959), and Carson v.

Warlick, 238 F. 2d 724 (4th Cir. 1956), conspicuously did

not mention race as a basis for determining transfers.

17

When race has been found to be a consideration affecting

transfers in the pupil assignment law cases, the appellate

courts have uniformly held the pupil assignment laws to be

invalidly applied. See for example: Norwood v. Tucker,

287 F. 2d 798 (8th Cir. 1961); Mannings v. Board of Public

Instruction, 277 F. 2d 370 (5th Cir. 1960); Green v. School

Board of the City of Roanoke, Va., — — F. 2d----- (4th Cir.

No. 8534, May 22, 1962); Marsh v. County School Board of

Roanoke County, V a.,-----F. 2 d ------ (4th Cir. No. 8535,

June 12,1962); Jones v. School Board of City of Alexandria,

278 F. 2d 72 (4th Cir. 1960). The pupil assignment cases

support the view that the racial transfer is invalid, since

the only manner in which the rule can be invoked is on the

basis of race.

The Sixth Circuit’s holding then furnishes no safeguards,

or real limitations on use of the transfer rule. There is no

indication that the Court regarded the rule as an interim

or temporary transitional device to be discarded at a later

date, nor is there any indication that the trial court so

viewed it. Thus retention of jurisdiction has no particular

significance on this point.

While the court below discussed plaintiffs’ argument that

the rule would perpetuate segregation in the Negro schools,

there is no discussion of plaintiffs’ argument that the rule

discriminates against Negro pupils living near the Negro

schools. This discrimination is very plain and simple. A

Negro child living in the zone of an all-Negro school must

go to that school; his white neighbors are permitted to

transfer out of the zone and attend an all-white or pre

dominantly white school. This valued privilege to transfer

out of a school zone is thus conferred or denied solely on

the basis of the race of the pupil. This is exactly the type

of racially discriminatory application of transfer rules con

demned in each of the pupil assignment law cases cited

above.

18

It is interesting to compare this device with that revealed

in Taylor v. Board of Education of City of New Rochelle,

191 F. Snpp. 181, 185; 195 F. Supp. 231 (S. I). N. Y. 1961),

app. dismissed 288 F. 2d 600, affirmed 294 F. 2d 36 (2nd

Cir. 1961), cert. den. 368 TJ. S. 940, where the courts went

even a step beyond condemning a practice similar to that

here. In Taylor the school officials had at one time followed

a rule allowing white children to transfer out of a Negro

school zone, but abandoned this practice before the suit was

brought. The Court held that the school board was never

theless still obligated to relieve the segregated situation

which continued because of this prior practice and a prior

gerrymandering of zone lines. A fortiori from the Taylor

decision, a present practice of allowing white pupils to

transfer out of a Negro school zone on the basis of race is

unlawful.

However, here the defendants point to the correlative

provision of the plan which effects a similar disparity in

treatment on a racial basis in white school zones as justify

ing that in the Negro zones. They argue that since a white

child in a white area cannot transfer, but a Negro there can

transfer to a Negro school, the reciprocal discriminations

“balance out” as it were. But this symmetrical inequality

of treatment on a racial basis ignores the personal nature

of the Fourteenth Amendment rights to racially nondis-

criminatory treatment by school officials. The Negro pupil

denied a transfer granted to his white neighbors is no less

aggrieved by this because in other areas of the city white

pupils are denied options given to Negroes, particularly

where this denied “privilege” (to attend the all-Negro

school) is one that few white persons in the community

desire in any event.

The problem is very much like that dealt with in Shelley

v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1, where it was argued that a racial

19

restrictive covenant enforced against Negroes was valid,

since the courts would enforce similar covenants against

white persons. After observing that it knew of no case of

such a covenant against white persons, the Court said at

834 U. S. 22:

But there are more fundamental considerations. The

rights created by the first section of the Fourteenth

Amendment are, by its terms, guaranteed to the in

dividual. The rights established are personal rights.

[Footnote citing McCabe v. Atchison, T. & S. F. B. Co.,

235 U. S. 151, 161; Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada,

305 U. S. 337; Oyama v. California, 332 U. S. 633.] It

is, therefore, no answer to these petitioners to say that

the courts may also be induced to deny white persons

rights of ownership and occupancy on grounds of race

or color. Equal protection of the laws is not achieved

through indiscriminate imposition of inequalities.

It is submitted that the ruling of the Fifth Circuit in

Boson v. Bippy, 285 F. 2d 43, 47-50 (5th Cir. 1960) is in

accord with this Court’s determination in Brown v. Board

of Education, 347 U. S. 483 that racial classifications in

public education violate the Fourteenth Amendment. Such

racial classifications are “not reasonably related to any

proper governmental objectives.” Bolling v. Sharpe, 347

U. S. 497, 500.

This transfer plan violates these principles by classify

ing schools both by reference to the race of the pupils

previously attending them, and by reference to the race

of the majority of the pupils in each school. It also classi

fies pupils by race in determining their eligibility to trans

fer. Such racial classifications are presumptively arbitrary.

Cf. Korematsu v. United States, 323 U. S. 214, 216; Eira-

bayashi v. United States, 320 U. S. 81, 100. The defendants

20

It is submitted that this does not satisfy the defendants’

obligation under Brown, supra, and Cooper v. Aaron, 358

IT. S. 1, 7 “to devote every effort toward initiating desegre

gation and bringing about the elimination of racial dis

crimination in the public school system.”

The public importance of the issue presented by this

racial transfer plan has increased as its use has become

widespread. When the issue was first brought to this Court’s

attention in 1959 in the Kelley case, it was a new issue and

involved only Nashville, Tennessee. Nevertheless, at that

time the Chief Justice, Mr. Justice Douglas and Mr. Justice

Brennan, indicated that they:

. . . although cognizant that the District Court retained

jurisdiction of the action during the transition, would

grant the petition for certiorari limited to the fourth

question: whether the provisions of paragraphs four

and five of the plan are constitutionally invalid for the

reason that they “explicitly recognized race as an

absolute ground for the transfer of students between

schools, thereby perpetuating rather than limiting

racial discrimination” (361 XL S. 924).

Since Kelley, this plan has been adopted in numerous

communities, and the courts have expressed divergent

views. In addition to Boson v. Rippy, supra, and the two

cases involved here, see Mapp v. Board of Education of

City of Chattanooga, Tenn., 203 F. Supp. 843 (E. D. Tenn.

1962) which held such a transfer plan invalid a few days be

fore Goss, saying: “Reason would appear to favor the Bo

son decision. Not only is the proposed transfer plan of ques

have not offered any theo ry to ju s tify these rac ial classifi

cations except th a t they accom m odate those who desire

segregation (R. Goss 109a).

21

tionable legality, but it is the opinion of the Court that any

transfer plan, the express or primary purpose of which is

to prevent or delay the adoption or implementation of the

plan of desegregation herein developed, should not be ap

proved. The transfer plan proposed by the Board of

Education would at the very least greatly delay the imple

mentation of a plan already gradual in its provisions, if not

prevent its ever becoming fully adopted.” See also Jackson

v. School Board of City of Lynchburg, Va., 203 F. Supp.

701, 704-706 (W. 1). Va. 1962) (held plan valid; appeal

pending); Thompson v. County School Board of Arlington

County, Va., unreported (E. D. Va. March 1, 1962) (ex

cerpts in 30 U. S. Law Week 2446; held plan valid, refused

to retain jurisdiction, vacated injunction; appeal pending).

The Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit now has this

issue under advisement in a case argued June 12, 1962,

Dillard v. School Board of City of Charlottesville, Va., 4th

Cir. No. 8638.

The racial transfer device has thus become a significant

and effective method for limiting desegregation. Its use

insures that the traditional all-Negro schools will remain

all-Negro, even after every grade is covered in a grade-by

grade plan. This has been the uniform experience with

this device^ The transfer rule is thus a potent device for

partially negating this Court’s decision in Brown v. Board

of Education.

This Court has reviewed but one school desegregation

case, on plenary hearing, since Brown, e.g., Cooper v. Aaron,

supra, nearly four years ago. In the seven years since the

second Brown decision school segregation litigation has

been extensive. Progress in desegregation has been statis

tically insignificant in some of the states where there has

been the most litigation. The Southern School News re

ported in May 1962 (Volume 8, No. 11, p. 1) that only 7.6%

22

of the Negro students in 13 southern states and the Dis

trict of Columbia were in school with white pupils,2 that

there has been an increase of only 1.6% in the past two

years; and that the District of Columbia and six border

states have the greatest proportion of these desegregated

Negro students. It is submitted that a review of this case

will enable the Court to scrutinize one of the principal

methods being used to preserve segregation against legal

attacks.

II.

The decision below in the Maxwell case denying in

junctive relief to three Negro plaintiffs who sought ad

mission to white schools in grades not reached by the

plan is in conflict with principles established by this

Court and is of public importance.

Petitioners, Henry C. Maxwell, Jr., Benjamin G. Maxwell

and Deborah Buth Clark, have been admittedly denied

admission to schools they otherwise would be entitled to

attend under the segregation policy. The courts below

recognized that this denial of admission infringed their

rights under the Fourteenth Amendment, but denied relief

on the ground that exceptions would “destroy” the grade-

by-grade plan.

It is submitted that the courts below failed to give ade

quate recognition to the principle stated by this Court in

the second Brown decision, where it said:

At stake is the personal interest of the plaintiffs in

admission to public schools as soon as practicable on

a nondiscriminatory basis (349 U. S. at 300).

2 The Tennessee figure was reported at .750%, representing 1,167

students in 17 communities. Southern School News, May 1962,

Vol. 8, No. 11, pp. 1, 9.

23

This Court had, of course, previously emphasized the per

sonal nature of the rights involved. Sweatt v. Painter, 339

U. S. 629, 635; Sipuel v. Board of Regents, 332 U. S. 631,

633; Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U. S. 1, 22.

In terms of all of the factors mentioned by the second

Brown decision, the admission of these plaintiffs was plainly

shown to be practicable when their request was made. The

Superintendent of Schools justified their exclusion only

in terms of apprehended “friction” and “bloodshed” aris

ing out of opposition to desegregation. These factors are

plainly legally irrelevant in even supporting delay of plain

tiffs’ rights, and certainly cannot justify abandoning them

altogether. Brown v. Board of Education, 349 U. S. 294,

300; Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U. S. 1, 7, 16; Buchanan v.

Warley, 245 IT. S. 60, 81.

The statement by the Court of Appeals that a multiplicity

of individual suits for such admissions could thwart the

smooth working of the plan (301 F. 2d at 829) rests the

decision of the case before the court on problems which

might arise out of a possibility which has not yet occurred

and might never occur. Here only three persons seek ex

ceptions to the plan. If larger numbers sought similar

privileges, a different administrative problem might be pre

sented and could be dealt with accordingly. There was

room for the plaintiffs in the schools they sought to attend.

The fact that later applicants might present an overcrowd

ing problem should not bar these applicants. The Fourth

Circuit recently rejected such a contention in Marsh v.

County School Board of Roanoke County, V a.,----- F. 2d

——• (4th Cir. June 12, 1962), saying “the fear that appli

cations which have not yet materialized might create a

serious crowding problem is no reason for rejecting appli

cants before the problem has arisen.”

24

The Third Circuit in Evans v. Ennis, 281 F. 2d 385, 393

(3rd Cir. 1960), rejected a grade-a-year plan, stating as

one of its reasons the fact that the plaintiffs were deprived

“of any chance whatever of integrated education.” Evans

v. Ennis, supra, required that pupils who actually sought

desegregation he granted relief, though it permitted com

plete elimination of the dual system to proceed over a

longer period. Similarly the Fourth Circuit has approved

decisions granting individual litigants relief as exceptions

to general desegregation programs in Board of Education

v. Groves, 261 F. 2d 527, 529 (4th Cir. 1958); Moore v.

Board of Education, 252 F. 2d 291 (4th Cir. 1958). See

also Pettit v. Board of Education, 184 F. Supp. 452 (D. Md.

1960); and cf. Jackson v. School Board of City of Lynch

burg, Va., 201 F. Supp. 620 (W. D. Va. 1961). Cf. also the

concurring opinion by Justice (then Judge) Stewart in

Clemons v. Board of Education, 228 F. 2d 853, 859-860

(6th Cir. 1956).

The importance of a nonsegregated education to these

plaintiffs is indeed reemphasized by a finding in the record

that on an overall basis Negro children who have not

attended desegregated schools have achievement levels sub

stantially below white children and that this disparity in

Davidson County “increases in direct proportion to the

grade of the child” (R. Maxwell 126a-127a). The trial court

regarded this as support for a gradual desegregation pro

gram. However, it obviously demonstrates that the longer

Negro pupils are kept in segregated schools, the more their

disadvantaged situation is aggravated.

The trial court’s suggestion (173a) that it would be dis

crimination in favor of the plaintiffs if they were granted

exceptions is extremely ironic, since the question involved

is whether a court of the United States shall enforce per

sonal constitutional rights to the equal protection of the

APPENDIX A

Opinions and Judgments in Goss Case

3a

infant plaintiffs and other negro children similarly situated

who reside in the areas proximately surrounding said

schools, solely because of their race or color. The defen

dant, Board of Education, maintains and enforces a policy

and practice of compulsory racial segregation throughout

the Knoxville School System.

Fulton High School, in addition to providing the usual

high school courses, affords adequate facilities to provide

technical and vocational instruction on a modern basis by

grades. It is used by white children residing in the City

of Knoxville, Tennessee who desire and are qualified to

take said technical and vocational instruction, irrespective

of their place of residence in the City of Knoxville; but

the facilities afforded by Fulton High School are denied by

defendants to infant plaintiffs who desire instruction, and

other negro children similarly situated, residing in the

City of Knoxville, irrespective of their place of residence

in the City of Knoxville, solely on account of their race

or color.

The School System of Knoxville consists of 40 schools,

total enrollment of 22,448 students, of whom 4,786 are negro

students and 17,662 are white students, as at the close of

school June, 1960. On that day, the Knoxville School Sys

tem employed a total of 879 principals and teachers, 712

of whom are white persons and 167 are negroes.

The enrollment in the first grade of the Knoxville Public

School System was approximately 2,314 students, and 2,500

are anticipated in the first grade for the year beginning

1960, of whom approximately 1,900 are anticipated to be

white students and 600 negro students. Teachers employed

for the first grade, year 1959-1960 of the Knoxville School

System numbered 84, of whom 63 were white persons and

21 were negroes.

District Court Memorandum Opinion

4a

Insofar as quality of teaching is concerned, the Public

Schools of Knoxville operated for negro students are sub

stantially equal to the Public Schools of Knoxville operated

for white students.

There is no difference in the salary schedules of negro

teachers and white teachers.

The physical facilities for white and negro students are

excellent.

Beginning with the year 1954 and continuing from time

to time to the filing of the present suit, negro parents and

children and other citizens have petitioned the School

Board and appeared before the School Board and asked the

Board to take immediate action towards desegregation of

the Public School System.

On June 16, 1955, the Attorney General of Tennessee

rendered an opinion to the State Commissioner of Educa

tion, and through him to the Superintendent of Education

for the State of Tennessee, in which he stated in substance

that under the Tennessee Code it is the responsibility of

each local school board to determine for itself the way in

which it will meet the problems of desegregating the schools

under its jurisdiction. As a result of this opinion, together

with the decision of the United States Supreme Court in

the Brown Case, the Board in a special meeting held on

August 17, 1955 resolved that it would act in good faith to

implement the constitutional principles declared in the

Brown decision as applied to public schools, and would

make a prompt and reasonable start towards those objec

tives.

The Superintendent and his administrative Staff were

instructed to develop a specific plan of action leading to the

gradual integration of the Knoxville public schools.

D istric t C ourt M em orandum O pinion

5a

At a special meeting held on August 17, 1955, following

the second Brown decision of May 31, 1955, the Board re

affirmed its policy to work towards gradual desegregation.

Two Members of the Board and two Members of the

supervisory Staff visited the integrated public schools of

Evansville, Indiana in July, 1955 to study desegregation in

those schools.

On August 17,1955 the Board directed the Superintendent

and his Staff to develop a plan of action leading to the

gradual integration of the public schools and to that end

the Superintendent and his Staff began holding meetings

for the purpose of further exploring the subject. As an

outgrowth of these meetings, the study council, composed

of all principals, school administrators and supervisors

(both white and negro) and the Superintendent of Schools,

was formed for the purpose of exploring and studying plans

and procedures in school desegregation. This study council

held an additional series of meetings and formulated sev

eral possible plans for desegregation, eight of which were

presented to the Board for the Board’s study. These study

groups continued with their meetings the remainder of

1955 and during the year 1956.

In the meeting of May 11,1956, the Board announced that

each of the eight plans for desegregation had been carefully

reviewed by the Board but that the Board did not feel at

that time that desegregation of the Knoxville public schools

could be successfully put into operation. Three reasons

were given for such action:

(a) Segregation should not be attempted until the school

building program is further advanced.

(b) The Members of the Board do not believe that the

people of both races are ready for a definite plan for de

segregation and that further delay would lessen the likeli

D istric t C ourt M em orandum O pinion

6a

hood of unpleasant incidents which have occurred in some

places where desegregation has been inaugurated.

(c) Before any plan for desegregation is put into effect,

further studies should be made of the subject, and plans

further developed that the children of both races will not

be handicapped by a radical change in their classroom life.

During the week of August 27, 1956, serious trouble de

veloped in Anderson County, Tennessee in the integration

of the Clinton High School. This trouble produced several

tense hearings and trials in this Court. In September, 1957,

a Nashville, Tennessee elementary school was bombed and

severely damaged. On October 5,1958, Clinton High School

in Clinton, Tennessee was bombed causing damage esti

mated at $250,000.00 to $300,000.00.

A hearing was held by this Court on February 8, 1960 on

plaintiffs’ motion for a preliminary injunction prohibiting

the defendants from refusing to admit or transfer the

infant plaintiffs to the schools to which they had applied

for admittance on account of their race or color and for

the declaratory relief sought in the complaint. At this

hearing, defendant, Board of Education, agreed that it

would submit a plan for desegregation on or before April

8, 1960. Action on other phases of the relief sought in the

complaint was postponed, pending the submission of the

plan.

On April 8,1960, the Board filed the following Plan, which

is sometimes referred to as Plan Nine:

“1. Effective with the beginning of the 1960-61 school

year racial segregation in Grade One of the Knox

ville Public Schools is discontinued.

2. Effective for 1961-62 school year racial segregation

shall be discontinued in Grade Two and thereafter

D istric t C ourt M em orandum O pinion

7a

in the next higher Grade at the beginning of each

successive school year until the Desegregation Plan

is effected in all twelve grades.

3. Each student entering a desegregated grade in the

Knoxville Public Schools will be permitted to attend

the school designated for the Zone in which he or

she legally resides, subject to regulations that may

be necessary in particular instances.

4. A plan of school zoning or districting based upon

the location and capacity (size) of school buildings

and the latest enrollment studies without reference

to race will be established for the administration of

the first grade and other grades as hereafter de

segregated.

5. Requests for transfer of students in desegregated

grades from the school of their Zone to another

school will be given full consideration and will be

granted when made in writing by parents or guard

ians or those acting in the position of parents, when

good cause therefor is shown and when transfer

is practicable, consistent with sound school admin

istration.

6. The following will be regarded as some of the valid

conditions to support requests for transfer:

a. When a white student would otherwise be re

quired to attend a school previously serving col

ored students only;

b. When a colored student would otherwise be re

quired to attend a school previously serving white

students only;

D istr ic t C ourt M em orandum O pinion

8a

e. When a student would otherwise be required to

attend a school where the majority of students of

that school or in his or her grade are of a differ

ent race.”

One Board Member voted against the Plan, stating that

“what the Board is doing is a mistake.”

The Members of the Board are continuously changing,

while the Members of the Administrative Staff remain con

stant. Certain Members of the Board are elected at biennial

election and this puts the terms of the Members on a

staggered basis.

Plaintiffs filed seven objections to the Plan on April

18, 1960. It is insisted by the plaintiffs in these objections

that: (a) The Plan does not provide for elimination of

racial segregation “with all deliberate speed” as required

by the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution; (b) it

does not take into account the five years which have elapsed

during which the Board has failed and refused to comply

with the Fourteenth Amendment; (c) a period of twelve

years for the consummation of the Plan is not in the public

interest and is not in compliance with the Fourteenth

Amendment; (d) the defendants have not carried the burden

of proof of showing problems related to public school ad

ministration as specified by the Supreme Court in the second

decision of Brown v. Board of Education (May 31, 1955),

349 U. S. 294; (e) under the Plan, the infant plaintiffs and

all other children attending the public schools of Knoxville

in their class will be deprived of their right to attend a de

segregated school as guaranteed to them by the Fourteenth

Amendment; (f) the Plan deprives infant plaintiffs and

those similarly situated from enrolling in Fulton Technical

High School and other special vocational schools, summer

D istric t C ourt M em orandum O pinion

9a

courses and kindred educational training of a specialized

nature as to which enrollment is not based upon residence;

and (g) Paragraph 6 of the Plan violates the due process

clause of the Fourteenth Amendment in that said paragraph

provides racial factors as conditions to support requests

to transfer, and the racial factors are designed and neces

sarily operate to perpetuate racial segregation.

A trial was held on August 8-11, 1960 on defendants’

motion for the adoption of the Plan and plaintiffs’ objec

tions thereto. Substantial testimony was introduced during

the trial, a material portion of which consisted of the read

ing of discovery depositions of various individual defen

dants and of a number of adult plaintiffs.

The controlling issue in the case and to which the greater

part of the evidence was directed is :

Is the time delay provided for in the grade a year de

segregation proposal reasonably necessary in the public

interest and is it “consistent with good faith compliance at

the earliest practicable date”? See Brown v. Board of Edu

cation, supra.

It is the position of the Board that a more accelerated

plan for desegregation would cause administrative prob

lems of great magnitude and serious interruption in the

operation of the Knoxville School System with resultant

deleterious effects upon the school children of both races.

The Board maintains that the grade a year plan is a

compliance with the “deliberate speed” concept in the light

of the existing conditions in the Knoxville area.

As to the good faith phase of the issue, the Board insists

that its Members, the then Superintendent of Schools and

the Members of his Staff, began to consider the question of

desegregation immediately following the first decision in

the Brown Case in 1954 but that they withheld efforts to

D istric t C ourt M em orandum O pinion

10a

perfect a plan until the second Brown decision on May 31,

1955; that following this decision Board meetings and work

shop meetings were held by the Board with principals of

negro schools and white schools; and that much of the

literature on the subject of desegregation was studied with

the view of finding a plan that would meet the needs of the

Knoxville community and at the same time protect and

enforce the constitutional rights of the negro children

attending the public schools of Knoxville.

In support of the Plan, Superintendent Johnston testified

that he became Superintendent on June 15, 1955 and that

on the next day he asked his Administrative Staff to come

together to discuss the Supreme Court’s decision and steps

that ought to be taken to study the best approach to com

pliance with the decision; that out of the meeting grew the

suggestion that some Members of the Staff and of the Board

visit a city with experience in desegregation; and that the

City of Evansville, Indiana was chosen because of its com

parable size and because it had been operating under a

desegregated program since 1949. He testified that two

Members of the Board and two Members of the Staff visited

the schools in that City and spent a day or more in the

schools and with the superintendent.

Subsequently, on July 25, 1955, he inaugurated a program

of inviting white principals, Members of the Board and

Staff to discuss how best to comply with the Supreme

Court’s decision. He attempted at the meeting to establish

an atmosphere or environment under which these persons

would talk freely on the subject.

A week later, they had a similar meeting with the negro

principals, Members of the Board and Staff at which exactly

the same matters were discussed in an atmosphere under

which the negro principals would feel free to ask questions

and make suggestions.

D istric t C ourt M em orandum O pinion

11a

He testified that separate meetings were field at his own

suggestion with the thought that participants would talk

more freely if they met separately and that thereby he

could better assess whether there was opposition or a good

feeling about the whole business.

At the same time, he inaugurated a series of Staff meet

ings for a period of an hour a day for 15 successive working

days for the exchange of views on the problem.

On January 26, 1956, he testified that they convened a

meeting of the negro principals and general supervisors in

the central office to determine whether they were willing to

participate in a series of meetings to consider the subject

of desegregation. A similar meeting with the white prin

cipals came a few days afterwards.

On February 1, 1956, a Staff meeting was held to survey

the willingness of principals of both groups to join in a

study group or workshop. On February 2, 1956, all prin

cipals regardless of race were called for a meeting in the

central office at which no shyness or reticence to discuss

the subject appeared. He commented that for 32 years to

his personal knowledge negro principals and white princi

pals had met together in regular meetings.

He testified that a series of workshop meetings were

developed to explore different plans and that out of these

meetings there evolved eight suggestions to be submitted

to the Board of Education without recommendation which

were the result of the studies of the principals of both races

and of the Staff.

Subsequently, in January, 1957 at a meeting, he requested

the principals of both races and the supervisors to meet

with him to further discuss the subject. At that meeting he

indicated that he would like personally to come to the

schools and sit down with their faculties and talk with the

D istric t C ourt M em orandum O pinion

12a

teachers to see how they felt on the subject because he felt

that “the burden of making that plan successful . . . would

be on the shoulders of the teachers who work closely with

children and with parents.” Following this meeting, he

testified that he started going to schools at the invitation

of the principals and that he attended 12 to 15 such faculty

meetings. It was his purpose to discover through these

informal meetings whether there were members of the

faculties who opposed any form of desegregation. He

wanted to determine whether there were pockets of re

sistance or whether a favorable climate for compliance

existed among the teachers. These meetings continued

through the school year 1957. By Fall, he testified, the

invitations seemed to slow down and that he seemed to de

tect a feeling amongst the negro and white principals which

did not exist before. He pointed out that there had been

dynamiting and other difficulties around the Knoxville

area; and that trouble had arisen in Nashville and Clinton.

Superintendent Johnston stated that violence occasioned

by desegregation in neighboring cities caused us to reflect

a little more on how it will affect us and made us more

conscious of what might happen here. He pointed out that

no child could get an education operating under a feeling

of fear or tension or emotional unrest and that every day

a child loses from its normal educational program is prac

tically gone forever and will never be completely regained;

that order is the first law in the classroom and that an

educational program must have order if children were

going to learn. He said: “We were concerned with that.”

At the same time, he noted that the School Board was

engaged in an extensive building program which involved

both Staff and Board and which was heavily time con

suming; that Board and Staff Members examined blue

D istric t C ourt M em orandum O pinion

13a

prints and drawings of the architects minutely and that they

made innumerable visits to the buildings when they were

under construction and that before a building was accepted

it was the duty of the Board to go through it, inspect the

rooms, corridors and facilities in the company of the archi

tect and of the representative of the contractor.

This was a massive building program carried out under

Bond Referendums of 1946 and 1954 and involved nearly

eight million dollars of new construction and remodeling in

both white and colored schools.

In implementation of the Plan filed on April 8, 1960, the

Superintendent testified that he instructed his Staff to be

gin work on a zoning map which was approved at a meeting

of the Board on August 6, 1960, just two days before the

hearings began. He testified that he instructed his Staff

that in the preparation of the map there would be no

maneuvering or gerrymandering, that the re-zoning and

re-establishing of school zones must be based on enrollment

studies and on the size and capacity of the buildings. The

work was in charge of Mr. Frank Marable, Supervisor of

Child Personnel, whose duty it is to check on attendance,

school zones and the movement of people.

On cross-examination, he testified that in preparing the

map, efforts were made through the pre-school round-up

program and estimates of principals to get estimates of

the number of children that would be affected. This zoning-

plan was confined to the elementary schools and did not

include the secondary schools.

Under detailed cross-examination, Mr. Johnston pointed

out that small groups or pockets of negro homes were

scattered throughout the Knoxville City School System in

contrast to major concentrations of negro citizens; that the

zone boundaries were often dictated by artificial barriers

D istric t C ourt M em orandum O pinion

14a

like heavily traveled streets and also by the size and capaci

ties of school buildings.

In response to a question that some capacity was pre

served at Park Lowry for transfers which were authorized

under the Plan, he testified that he had no way of knowing

who was going to ask for a transfer and that he only knew

that under the Plan white students and negro students

would be treated alike.

He testified categorically that no member of his Staff

in working on the map had ever operated deliberately to

cut out negro children; and that they tried to work the

thing out on a fair basis, depending on the size of the build

ing, shifting population and enrollment.

With reference to the fact that eight plans were originally

developed for submission to the Board and that the Plan

which was finally adopted involved only a grade a year

desegregation, he testified that the Plan adopted was based

on the experience around us and studies of the general

situation of desegregation; that it was felt that this plan

could be introduced in the City of Knoxville with the least

disturbance to the over-all educational program; and that

it would be accepted by the majority of citizens with less

tension and less emotional excitement than any other plans

that had been studied.

He reiterated that the Knoxville School System had been

in existence since 1870 and that desegregation would not

be easy; that it was the goal to achieve desegregation and

at the same time maintain an orderly decorum or environ

ment under which all children could continue to go to

school day by day free from tension and free from fear.

He repeated that order is the first rule of a classroom.

In presenting the grade a year plan to the Board, the

Staff made seven observations in favor of the plan. The

D istric t C ourt M em orandum O pinion

15a

first was that it appeared to meet the requirements of the

Supreme Court decision and of the laws of the State which

placed the burden or responsibility on local boards for de

segregation and for the assignment and placement of

students. Second, the Plan did not limit the speed with

which it could be implemented. Third, it provided for

gradual implementation until the complex problems of zon

ing, transfer and assignments of students could be ad

justed in the light of experience. Fourth, it had the ad

vantage of numerous other plans as a background for its

adoption. Fifth, the main features of the Plan have been

upheld by higher courts. Sixth, the Plan lessened the

opportunity for developing prejudices. Seventh, it mini

mized the possibility of administrative problems that could

be of such complexity and magnitude as to seriously under

mine and impair the total educational program of the City.

Finally, he emphasized the adaptability of small children

and that they do not have the prejudices of older children

or grown people and could be fitted into the work easier

than older children. He felt that the gradual plan would

enable the school system to continue a fine educational pro

gram with less tension, less fear and less emotional dis

turbances than a plan which rushed into a broader field of

desegregation. He felt that the gradual plan would have

the sympathetic understanding of the great majority of

the citizens of the City. He pointed out the importance of

this in going before the City Council on behalf of school

budgets with which to operate the schools; that the School

System had to have the sentiment of the people with it

because it involves budgets, their attitude towards refer-

endums for new schools and new buildings, etc.

With reference to evidence that there had already been

desegregation of ball parks, public libraries, buses and air

D istr ic t C ourt M em orandum O pinion

16a

port restaurants, etc. in and around Knoxville and that

this would seem to indicate that a speedier plan of desegre

gation could be inaugurated, Superintendent Johnston

pointed out that under the compulsory attendance law,

children are compelled to go to school for a period of seven

hours a day and that he knew of no law that compelled them

or any adult to go to a ball park, the library or airport

restaurants. He pointed out that those were optional mat

ters, but that under the school law children were required

to go to school.

In the course of his testimony, Superintendent Johnston

testified to certain achievement tests given all children in

the sixth grade in the Knoxville schools. His testimony was

that as a result of these tests it appeared that the achieve

ment levels of students from white schools were somewhat

above the national norm and that the student level from

colored schools were substantially below the national norm.

This testimony was objected to by the plaintiffs on the

ground that the results of the tests were hearsay. The