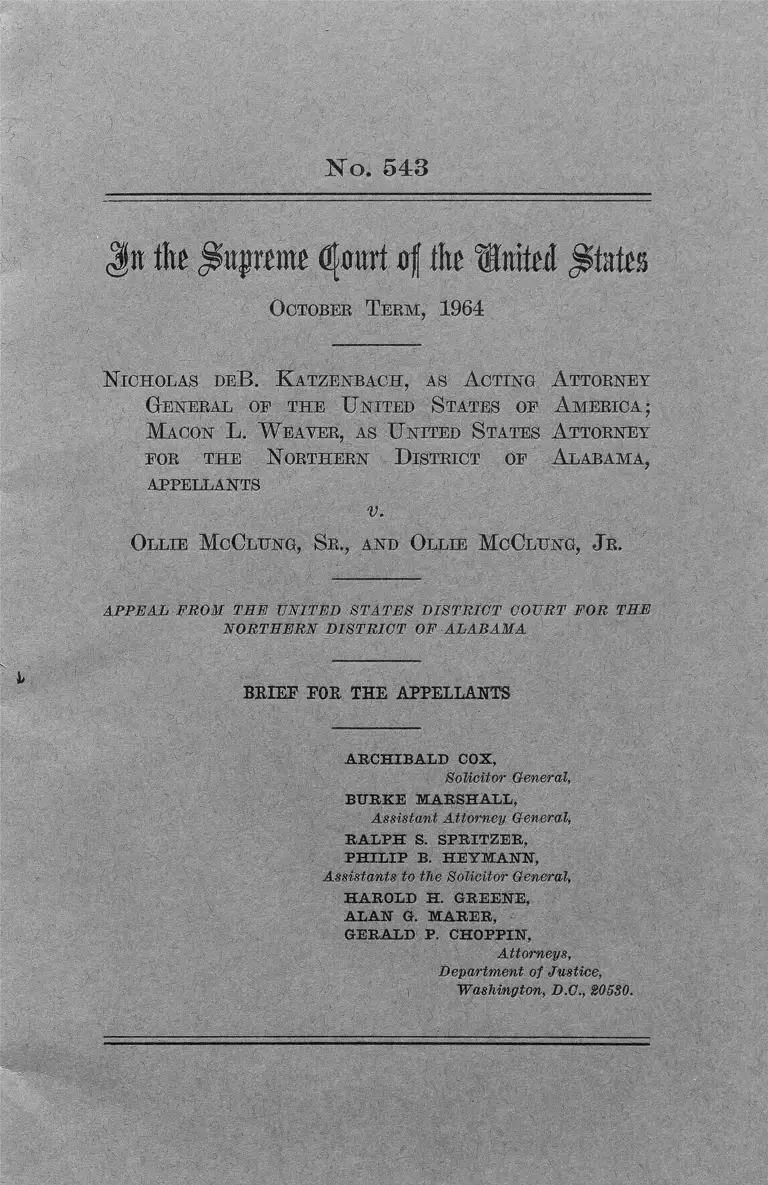

Katzenbach v. McClung Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

October 5, 1964

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Katzenbach v. McClung Brief for Appellants, 1964. 1929fa9c-b99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/be3bbe52-76e5-43c7-adf0-c42bb33a7762/katzenbach-v-mcclung-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 26, 2026.

Copied!

N o . 5 4 3

Jtt ilxt JSfljmne d[m\ <rf th Mnlid $tnU%

October T eem , 1964

N icholas deB. K atzenbach, as A cting A ttorney

General of th e U nited S tates of A m erica ;

M acon L . W eaver, as U nited S tates A ttorney

for th e N orthern D istrict of Alabama,

appellants

v.

Ollie M cClung, Sr ., and Ollie M cClijng, J r.

APPEAL FROM T B E UNITED STA T E S D ISTRIC T COURT FOR THE

NO RTHERN D ISTRIC T OF ALABAM A

BRIEF FOR THE APPELLANTS

ARCHIBALD COX,

Solicitor General.

BURKE MARSHALL,

Assistant Attorney General,

R A L PH S. SPRITZER,

P H IL IP B. H EY M AN N,

Assistants to the Solicitor General,

HAROLD H. GREENE,

A LA N G. M ARER,

GERALD P. CHOPPIN,

Attorneys,

Department of Justice,

"Washington, D.C., 20530.

I N D E X

Pag*

Opinion below--- ------------------------------------------------------- 1

Jurisdiction----.---.-.— — _——------------------------------------- 1

Questions presented__ -------------------------------- 2

Statutes involved-------------------- ——____-------------------- 2

Statement--______________ ____ — — '------------------- 2

Summary of argument-:--- -------------------------- 7

Argument_____A----,— :— --------------------------------- 11

I. The complaint should be dismissed for want of

equity jurisdiction_________________ 12

II. Section 201 of the Civil Eights Act of 1961, as

applied to appellee’s restaurant, is a valid

exercise of the commerce clause______________ 24

A. The power to regulate interstate com

merce extends to local activities whose

regulation is appropriate to protect in

terstate commerce from burdens or

obstructions__________________________ 27

1. The power of Congress is not con

fined to the regulation of the

course of interstate commerce but

extends to matters substantially

affecting it__________________ 27

2. The power to regulate local matters

substantially affecting interstate

commerce extends to retail estab

lishments including restaurants_ 30

3. Cases holding that interstate com

merce ends when goods “come to

rest” in a State are irrelevant to

the power of Congress to regu

late local activities which sub

stantially burden interstate com

merce_______________________ 32

(i)748-011—64------1

II

Argument—Continued

II. Section 201 of the Civil Rights Act, etc.—Con.

B. Racial discrimination in restaurants sell

ing food from out-of-state sources bur- pag8

dens and obstructs interstate commerce. 35

1. Racial discrimination in restau

rants serving food from out-of-

state is a prolific source of

disputes burdening and obstruct

ing interstate commerce_______ 38

2. Racial discrimination in restau

rants serving food from out-of-

state artificially restricts the

market for goods moving in

interstate commerce___________ 44

3. The absence of an explicit recital

that racial discrimination in

restaurants serving food from

out-of-state sources burdens in

terstate commerce does not in

validate Title I I ______________ 48

4. Title I I is not invalidated by the

absence of provision for an ad

ministrative or judicial finding

whether discrimination in an

individual restaurant affects in

terstate commerce, before bring

ing it within the coverage of

the Act,.__. . . ------------------— 53

Conclusion.._____ _______ _______ _____ _______________ 58

CITATIONS

Cases:

Adair v. United States, 208 U.S. 161.---------------- - 29

Adler v. Board of Eduoation., 342 U.S. 485---------- 23

Arizona v. California, 283 U-S. 423------ — -------- 53

Ashwander v. Tennessee Valley Authority, 297

U.S. 288____ ________________________ _______ 18

Baltimore <& Ohio R. Co. v.. Interstate Commerce

Comm., 221 U.S. 612____ . . . . . . -------- -— . 29,49,55

Berea College v. Kentucky, 211 U.S. 45------------------ 18

Cases—Continued

Board of Trade of Kansas City v. Milligan, 90 F. pag«

2d 855_________________ -___________________ ' IV

Bolton & H ay, 100 N.L.R.B. 361________________ 32

Boynton v. Virginia, 361 TJ.S. 454---------------------— 58

Brandeis <& Sons, J . L. v. Labor Board, 142 F. 2d

977, certiorari denied, 323 TJ.S. 751------------------ 31

Brennan's French Restaurant, 129 N.L.R.B. 52-------- 32

Brooks v. United States, 267 TJ.S. 432------------------- 37

Browder v. Gayle, 142 F. Supp. 707 affirmed 352

TJ.S. 902_____________ _______ _______________ 17

Brown v. Maryland, 12 Wheat. 419_______________ 33

Camhnetti v. United States, 242 TJ.S. 470--------------- 37

Carter v. Carter Coal Co., 298 TJ.S. 238---------------- 23,29

Chicago Board of Trade v. Olsen, 262 TJ.S. 1--------29,36

Chicago ds Grand Trunk Ry. v. Wellman, 143

TJ.S. 339_______________ ____________________ 18

Childs Co., 88 NLRB 720________________________ 32

Childs Co., 93 N.L.R.B. 281_____________________ 32

City o f Yonkers v. U.S., 320 TJ.S. 685___________ 50

Civil Rights Cases, The, 109 TJ.S. 3------------------- 25

Clark v. Paul Cray, Inc., 306 TJ.S. 583------------------ 51

Consolidated Edison Co. v. Labor Board, 305

TJ.S. 197_________________________________ — 47

Coronado Coal Co. v. United Mine Workers, 268

TJ.S. 295_________________ 29

Crown Kosher Supermarket v. Gallagher, 176 F.

Supp. 466, reversed on other grounds, 366

TJ.S. 617________________ _______ -___________ 17

Culinary Workers di Bartenders Union v. Labor

Board, 310 F. 2d 853________________________ 32

Currin v. Wallace, 306 TJ.S. 1----------------------------23,24

In re Debs, 158 U.S. 465________________________ 30

Douglas v. City o f Jeammette, 319 U.S. 157----------- 8,16

Euclid v. Ambler Realty Co., 272 U.S. 365---------l-_- 23

Everard's Breweries v. Day, 265 U.S. 545-------------------- 36

Federal Trade Commission v. Mandel Bros., 359

U.S. 385_______________________________ - 37,38,49

First Employers’ Liability Cases, 207 U.S. 463__—_ 29

Florida v. United States, 282 U.S. 194---------------- 50

Gibbons v. Ogden, 9 Wheat. 1------------------- — 9,28,30,59

til

IV

Cases—Continued pag®

Gober v. City of Birmingham, 373 U.S. 374_______ 7

Hamilton v. Kentucky Distilleries Go., 251 U.S. 146_ 53

Hammer v. Dagenhart, 247 U.S. 251_____________ 29

Hemderson v. United States, 339 U.S. 816_________37, 58

Hemdriek v. Maryland, 235 U.S. 610______________ 18

Hooven dr. Allison Go. v. Evatt, 324 U.S. 652_______ 33

Houston <& Terns By. v. United States, 234 U.S. 342_ 29

Lntrl Brotherhood v. Labor Board, 341 U.S. 694___ 31

Joe Hunt's Restaurant, 138 N.L.K.B. 470_________ 32

Kennedy v. Los Angeles Joint Exec. Board, 192 F.

Supp. 339___________________________________ 32

Labor Board v. Bradford Dyeing Assn., 310

U.S. 318____________________________________ 57

Labor Board v. Childs Go., 195 F. 2d 617--------------- 31

Labor Board v. Denver Bldg, da Const. Trades

Council, 341 U.S. 675------ .-------------------------------- 31,47

Labor Board v. Fainblatt, 306 U.S. 601__________ 47

Labor Board v. Gene Compton's Corp., 262 F,

2d 653______________________________________ 32

Labor Board v. Howard Johnson Co., 317 F. 2d 1,

certiorari denied, 375 U.S. 920--------------------------- 32

Labor Board v. Jones da Laughlin Steel Corp., 301

U.S. 1________________ - _________________ 28,29,36

Labor Board v. Laundry Drivers Local, 262 F. 2d

617_____________ _______ - ____- ______________31-32

Labor Board v. Local Joint Board, 301 F. 2d 149— 31

Labor Board v. Morrison Cafeteria Co. of Little

Rock, 311 F. 2d 534___________________________ 31

Labor Board v. Phoenix Mutual Life Insurance Co.,

167 F. 2d 983, certiorari denied, 335 U.S. 845----- 57

Labor Board v. Reliance Fuel Corp., 371 U.S. 224— 11,

28,30,46,57

Legal Tender Cases, 12 Wall 457------------------------- 50

Lion Manufacturing Corp. v. Kennedy, 330 F. 2d

833____________________________ ___ ,------------- 17

Local 7b v. Labor Board, 341 U.S. 707------------------ 31

Lottery Ca.se, The, 188 U.S. 321---------------------------- 37

May Department Stores Co. v. Labor Board, 326 U.S. .

376---------------- ----------- ---------------------------------- 31

McCray v. United States, 195 U.S. 27------------------- 53

V

Cases—Continued Page

McCulloch v. Maryland, 4 Wheat. 316------------------- 53

McDermott v. Wisconsin, 228 U.S. 115— — ----------- 38

McGowan v. Maryland, 366 U.S. 420—------------------ 51

McLeod v. Chefs, Cooks, Pastry Cooks <& Assistants

Local 89, 280 F. 2d 760___ ______ ____ — — — 32

McLeod v. Chefs, Cooks, Pastry Cooks & Assistants

Union, 286 F. 2d 727____ 32

Meat Cutters v. Pairlat.cn Meats, 353 U.S. 20----------- 31

Metropolitan Casualty Insurance Co. v. Brownell, 294

U.S. 580-------------------- 51

Mil-Bur, Inc., 94 N.L.R.B. 1161—-------------- --------- 32

Mintz v. Baldwin, 289 U.S. 346------------------ 33

Mitchell v. United Stales, 313 U.S. 80.----------------- 37, 58

Norman v. Baltimore c& Ohio II. Co., 294 U.S. 240— 35

Pacific States Box and Basket Go. v. White, 296 U.S.

176_________________________________________ 34

Packer Corp. v. Utah, 285 U.S. 105---------------------- 34

Pennsylvania v. West Virginia, 262 U.S. 553--------- 23

Pierce v. Society of Sisters, 268 U.S. 510--------------- 23

Polish National Alliance v. Labor Board, 322 U.S.

643--------- ------------------------- 47,49

Public Utilities Commission of California v. United

States, 355 U.S. 534-------------------------------------- 23

Railroad Commission of Wisconsin v. Chicago B. <&

Q. R. Co., 257 U.S. 563_______________ _____ 29

Railroad Retirement Board v. Alton R. Co., 295 U.S.

330_________________________________________ 29

Retail Fruits <& Vegetable Union v. Labor Board,

249 F. 2d 591______ 31

Richmond Hosiery Mills v. Camp, 74 F. 2d 200------ 16.

Ryan v. Amazon Petroleum Corp., 71 F. 2d 1-------- ' 16

Siemons Mailing Service, 122 N.L.R.B. 81--------------- 57

Siler v. Louisville and Nashville R. Co., 213 U.S.

175-------------------------- ------------------------------------- 18

Sinking Fund Cases, 99 U.S. 700-------------------------- 51

Sioux Valley Empire Electric Assn., 122 N.L.R.B.

92__________________________________________ 57

Smitley v. Labor Board, 327 F. 2d 351___________ 32

Southern Railtoay Co. v. United States, 222 U.S.

20_______________________________________ 29,49, 55

VI

Cases—Continued

South Carolina State Highway D eft. v. Barnwell page

Bros., 303 T7.S. 177____________________________33, 51

Sparks v. Mellwood Dairy, 74 F. 2d 695---------------- 17

Spielman Motor Co. v. Dodge, 295 U.S. 89------------ 15

Stafford v. Wallace, 258 U.S. 495------------------------- 36

Standard Oil Co. v. United States, 221 U.S. 1-------- 29

Stanton Enterprises, Inc., 147 N.L.R.B. No. 81, 4

CCH Lab. L. Rep. 21,075, para. 13,211--------------- 32

Stork Restaurant, Inc. v. McLeod, 312 F. 2d 105----- 32

Stouffer Corf., The, 101 N.L.R.B. 1331---------------- 32

Superior Court o f Washington v. Yellow Cab Co.,

361 U.S. 373__________1_____________________ 34

Sw ift da Co. v. United States, 196 U.S. 375------------ 35

Terrace v. Thompson, 263 U.S. 197---------------------- 22

Terns amd New Orleams Railroad v. Brotherhood

of Railway •amd Steamship Clerks, 281 U.S. 548— 29

Townsend v. Yeomans, 301 U.S. 441------------------- 52

Tyler v. Judges of the Court o f Registration, 179

U.S. 45____________________________________ 18

United Public Workers v. Mitchell, 330 U.S. 75------ 17

United States v. Butler, 297 U.S. 1---------------------- 51

United States v. Carotene Products Co., 304

U.S. 144____________________________________ 51

United States v. Darby, 312 U.S. 100— 11,28,29,38, 54, 56

United States v. Ferger, 250 U.S. 199------------- 29,49, 55

United States v. Harris, 106 U.S. 629------------------- 51

United States v. E. C. Knight, 156 U.S. 1------------ 29

United States v. Lowden, 308 U.S. 225--------------- — 29

United States v. Sullivan, 332 U.S. 689---------------- 37,49

United States v. Wiesenfeld Warehouse Co., 376

U.S. 86_____________________________________ 33

United States v. Wnghtvwod Dairy Co., 315

U.S. 110—______________________________ - — 27

Veazie Bank v. Fenno, 8 Wall. 533---------------------- 53

Virginian Ry. v. System Federation No. Ifl, 300

U.S. 515_____ _____ - ________ __________ — — 29,49

United States v. Yellow Gab Co., 332 U.S. 218-------- 34

Watson v. Buck, 313 U.S. 387__________________ — 17

Weigle v. Curtice Bros. Co., 248 U.S. 285-------------- 34

Wickard v. Filbum, 317 U.S. I l l __— 17,27,29,46,47,55

Woodruff v. Parham, 8 Wall. 123------------------- — 33

VII

Cases—Continued Page

Tarnell v. Hillsborough Packing Co., 70 F. 2d 435— 16

Youngstown Sheet <& Tube Co. v. Bowers, 358

U.S. 534__ 33

U.S. Constitution and Statutes:

Art. I, Sec. 8, Cl. 3_____________________________ 25,27

Art. I, Sec. 8, Cl. 18____________________________ 25

First Amendment----- ----------- -------------— -------11,24,59

Fifth Amendment__________________________ 7,11,24,59

Ninth Amendment------ ---------------------------:---------- 11,24

Tenth Amendment_________________ _—---------- - 4,11, 24

Thirteenth Amendment— -----i— :------------- -— 11,24, 59

Fourteenth Amendment------------------- —-----6,10

Fourteenth Amendment, Section 5—-----— — ----- 26

Civil Rights Act of 1875,18 Stat. 335-*— ,------ -------- 26

Civil Rights Act of 1957, 71 Stat. 637— ------- 20

Civil Rights Act of 1960, 74 Stat. 86------- 20

Civil Rights Act of 1964— 2, 4, 5, 8,12,13, 19, 20, 21, 25, 59'

Title 11— — 2, 4, 5, 6, 7, 12, 13, 15, 20, 53, 58, 59

Sec. 2Q1„____ -_______ *— -------— 8,13,24, 54,55

Sec. 201(a)_______________ - — -----------12,52

Sec. 201(b) (1)------- 19

Sec. 201(b) (2)—— _____________________ 19

Sec. 201(b)(3)__________________________ 19

Sec. 201(c)(2)__________________________ 4,12

Sec. 201(d)______________________________10,25

Sec. 207(b)_______________________ 13

Title X — _______— _____________- ______ 20

Automobile Information Disclosure Act, 15 U.S.C.

1231__________________________- — — -------- 49

Bill of Lading Act, 49 U.S.C. 121---------------------------- 49

Fair Labor Standards Act, 29 U.S.C. 201------- — ,— 48,49

Fair Labor Standards Act, 29 U.S.C. 201, Sec. 6-------- 55

Fair Labor Standards Act, 29 U.S.C. 201, Sec. 7-------- 55

Fair Labor Standards Act, 29 U.S.C. 201, Sec. 15

(a) ( 2 ) ------------------------- ---------- --------- --------- 55

Federal Food, Drug & Cosmetic Act, 21 U.S.C. 201----- 37

Fur Products Labelling Act, 15 U.S.C. 69--------------- 49

National Labor Relations Act, 29 U.S.C. 141------------ 48,49

Railway Labor Act, 45 U.S.C. 151------------------------- 49

Safety Appliance Acts, 45 U.S.C. 8------------------ .— 49

Safety Appliance Acts, 49 U.S.C. 26---------------------- 49

VIII

U.S. Constitution and Statutes—Continued page

Securities Exchange Act of 1934, 15 U.S.C. 78b-------- 49

Textile Fiber Products Identification Act, 15

U.S.C. 70_________________________________ — 49

Trust Indenture Act of 1939, 15 U.S.C. 77bbb--------- 49

18 U.S.C. 241, 242__________________________ 13,20

28 U.S.C. 1252_____________________________ 2

28 U.S.C. 1253_____________________________ 2

Miscellaneous:

Analysis of Prof. Paul A. Freund, S. Bep. 872, 88th

Cong., 2d Sess., pp. 82-83__________________ 38

Census of Business, U.S. Bureau of the Census, 1958— 19

110 Cong. Bee. (daily ed.) :

P. 7174____________________________________ 44

P. 7980___________________________________ - 39

1 Cooley Constitutional Limitations (8th ed.), p. 832_ 18

Hearings before the Committee on Commerce, United

States Senate, 88th Cong., 1st Sess., on S. 1732, Part

2, Ser. 27_____________________ 40, 41, 42, 43, 44, 45, 46

Beport of the House Judiciary Committee, 88th Cong.,

1st Sess., No. 914, Part 2, on H.B. 7152 (December

2, 1963 42

Jit ife JSitjimite <2{mtri of k t ®tM jStatea

October T erm , 1964

No. 543

N icholas deB. K atzenbach, as A cting A ttorney

General of the U nited S tates of A m erica ;

M acon L. W eaver, as U nited S tates A ttorney

for the N orthern D istrict of A labama,

appellants

v.

Ollie M cClung, S r., and Ollie M cClung, J r.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES D ISTR IC T COURT FOR THE

NORTHERN D ISTRIC T OF ALABAM A

BRIEF FOR THE APPELLANTS

OPINION BELOW

The opinion of the district court (R. 34) is not yet

reported.

JURISDICTION

The order of the district court was entered on Sep

tember 17, 1964 and a notice of appeal filed on the

same date.* 1 The jurisdictional statement was filed on

stay of the order was denied by the district court, on

September 18, 1964, but granted by order of Mr. Justice Black,

dated September 23, 1964.

(l)

2

September 28, 1964. The jurisdiction of this Court is

invoked under 28 U.S.C. 1252 and 1253.

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Whether the complaint should be dismissed for

want of equity jurisdiction.

2. Whether Title I I of the Civil Rights Act of

1964 is constitutional insofar as it prohibits racial

discrimination by a restaurant “if * * * a substan

tial portion of the food which it serves * * * has

moved in commerce.”

STATUTES INVOLVED

The relevant statutory provisions are printed in

Appendix A to the government’s brief in the com

panion Heart of Atlanta case, No. 515.

STATEMENT

On July 2, 1964, the President of the United States

signed into law the Civil Rights Act of 1964. On July

3, 1964, certain unnamed and otherwise unidentified

Negroes allegedly entered “Ollie’s Barbecue”, oper

ated by appellees in Birmingham, Alabama. They

requested, but were refused, service at the meal coun

ter; instead, they were offered “take-out” service at

the “colored take-out” end of the counter (R. 87-88).

Although the federal government had had no com

munication with appellees concerning compliance with

the Civil Rights Act of 1964, appellees, on July 31,

1964, filed a complaint in the United States District

Court for the Northern District of Alabama to pro

hibit appellants from enforcing or attempting to en

force the Act against them.

3

The complaint contains the following allegations:

Appellees’ restaurant serves approximately 500,000

meals annually and has gross sales of $350,000 (R. 2).

The establishment serves food and non-alcoholic

beverages, but specializes in barbecued meats and

pies which account for 90% of the business (R. 2).

There is parking space on the premises for about 90

automobiles and the seating capacity of the restaurant

is about 200 persons. Appellees have 36 employees,

26 Negro and 10 white (R. 2).

“Ollie’s Barbecue” is located in a part of Birming

ham “largely occupied by Negro residences, and by

industrial concerns employing a large number of

Negro employees” (R. 4). There is a truck route

one block away; the nearest “Federal or Interstate”

highway is 11 blocks away; the railroad station 17

blocks; the bus station 20 blocks; and the airport more

than five miles (R. 2).

Appellees “do no advertising and make no effort

to attract transient customers” (R. 2). The restau

rant “derives no trade” from the truck route and, to

their knowledge, appellees serve no interstate travelers

(R. 2). Negroes have never been served food or

beverages for consumption on the premises but have

been served for many years on a “take-out” basis

(R. 3, 4). I f Negroes were allowed service for con

sumption on the premises, they would occupy appel

lees’ restaurant in large numbers, to the exclusion of

appellees’ regular customers (R. 5). Appellees’ busi

ness and property would thereby suffer great injury

(R. 5).

4

The restaurant is described by appellees as “essenti

ally local in character,” purchasing all of its food

“within the State of Alabama” (R. 2, 5). Although

“some of the food served” by appellees “probably

originates in some form outside the State of Ala

bama”, the operation of the restaurant, it was averred,

“in no way affects interstate commerce” (R;. 6).2

The complaint further averred that the Civil Rights

Act of 1964 exceeds the power granted to Congress

under the commerce clause; that enforcement of the

Act would deprive them of property without due

process of law; that to require appellees to serve per

sons they had not chosen to serve would constitute

“involuntary servitude;” and that “any effort to en

force said Act against these [appellees] would be

invalid, in contravention of natural law and in viola

tion of the Tenth Amendment of said Constitu

tion” (R. 6-7).

Appellees state additionally that the Attorney Gen

eral and his subordinates are enforcing the Act

against others in reliance upon the provision “that a

restaurant’s operations ‘affect commerce’ if a sub

stantial portion of the food which it serves has merely

moved in commerce” (R. 5). They assert that “ [t]here

is a real and genuine threat” that appellants will seek

to apply it to them and that they have “no adequate

remedy in law” (R. 7).

2 After appellants had moved to dismiss on the groimd,

inter alia, that there was no case or controversy, appellees

produced testimony and affidavits indicating that the meat

products which they purchased for use originate outside the

State of Alabama, thus bringing themselves within the language

of section 201(c) (2) of the Act.

5

On August 4, 1964, a three-judge court was desig

nated. On the following day, a hearing was sched

uled for September 1, 1964 on appellees’ prayer for a

temporary injunction (R. 11,12). On August 19,1964,

appellants filed a motion to dismiss, asserting that the

court lacked equitable jurisdiction because appellees

had an adequate remedy of law by way of a defense

to a proceeding under Title I I of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964 (R. 16-17).

On August 21, 1964, appellees filed an amendment

to their complaint, striking references to I Oil X DOE

AND RUTH ROE, unidentified private defendants.

The amendment added the claim that the Civil Rights

Act of 1964 violated appellees’ rights under the First

Amendment (R. 18-19).

On September 1, 1964, a hearing was held on the

appellants ’ motion to dismiss and on appellees ’ prayer

for a preliminary injunction. The only witnesses

were the appellees. Their testimony largely repeats

the allegations of their complaint. However, in tes

tifying that the nearest interstate highway was 11

blocks from his restaurant, Ollie McClung, Sr., ac

knowledged that there was a State highway which

passed directly by his restaurant and intersected the

interstate highway (R. 71). He also stated that he

had declined service to Negroes because of their race

(R. 77); that most of the restaurants in Birmingham

had served Negroes since the Civil Rights Bill was

signed on July 2, 1964; that one of them had lost 25

percent of its business ; and that he had not heard

from any representative of the federal government

concerning compliance with the Civil Rights Act

6

(R. 78, 86). Ollie MeClung, Jr., testified that on

July 3, 1964, a group of Negroes requested counter

service at the restaurant and were refused because

“ it wasn’t our policy to serve them there and they

got up and left” (R. 88). An affidavit was intro

duced to the effect that all of the meat sold to appel

lees by their principal supplier, valued at $69,683

for the past twelve months and constituting 46 per

cent of all its purchases, was procured from facilities

located outside the State of Alabama (R. 31-32).

On September 17, 1964, the three-judge court ruled

that Title I I of the Act is unconstitutional as applied

to appellees and enjoined appellants from enforcing

it against them pending further order of the court.

The court found that a substantial portion of the food

served by appellees had moved in commerce and that

they were therefore within the terms of the statute.

I t stated that since Title I I imposed a mandatory

duty of service upon appellees and since the Attorney

General was engaged in enforcing it according to its

terms, the prospect of its application to appellees was

“reasonably imminent.” Turning to the question

whether the Act was a proper exercise of the com

merce power, the court reasoned that the out-of-

State supplies handled by appellees had come to rest

before they were sold by the restaurant and that

there was no basis for concluding that there was any

“demonstrable causal connection” between the activi

ties of the restaurant and interstate commerce.3 In

3 The court had previously ruled that the legislative power

conferred by the Fourteenth Amendment was not in point

since there was no showing that the State of Alabama was in-

these circumstances, the court stated, application of

the Act to appellees would violate the Fifth

Amendment.

SUM M ARY OF ARGUMENT

I

The complaint should he dismissed for want of

equity jurisdiction. Title I I of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964 provides for enforcement only by a civil

action for an injunction, at which point all factual

and legal defenses can be raised. The Act authorizes

no criminal prosecution and provides for no civil

penalties. There is no provision for the award of

damages to any person. In this case there has been

no threat to seek an injunction against appellees; be

fore they filed suit the Department of Justice did

not even know of their existence. Appellees claim

that they would be injured by compliance but they

deny any intent to comply and they neither alleged

nor proved that the Act operated ex proprio vigore to

discourage patronage and thus injure their business.

In short, this is a suit seeking to enjoin a possible

suit for an injimction not even threatened.

There is no precedent for adjudicating constitu

tional issues in such an action. Even where the stat

ute provides criminal penalties, the imminence of

prosecution “is not a ground for equity relief since the

lawfulness or constitutionality of the statute or ordi-

volved in appellees’ decision not to serve Negroes. The B ir

mingham restaurant segregation ordinance involved in Gober

v. Gity o f Birmingham, 373 TJ.S. 374, was repealed on July 26,

1963 (Ordinance No. 63-15).

7

8

nance on which the prosecution is based may be de

termined as readily in the criminal case as in a suit

for an injunction.” Douglas v. City of Jeannette,

319 U.S. 157, 163.

There are three reasons for that rule, which apply

with still greater force where there is no shadow of

present injury and the statute provides no penalties.

First, the judicial branch will not adjudicate ques

tions of constitutionality in the absence of a clear

need. Second, permitting such suits would interfere

with the normal processes of law enforcement by

compelling the Department of Justice to expend its

substance in defending unnecessary cases instead of

applying its resources in the manner best calculated

to promote the public interest. Third, a rule allow

ing suits to enjoin enforcement of the Civil Rights

Act could not be confined to that statute alone but

would extend at least to all other regulatory laws,

State and federal, when challenged on constitutional

grounds. The potentiality for damaging interference

with the normal administration of government is

obvious.

I I

Section 201 of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, both

in general and as applied to appellees’ restaurant, is

a valid exercise of the constitutional power to regu

late interstate commerce.

The power to regulate interstate commerce extends

to local activities which are not part of the stream

of commerce but whose regulation is appropriate to

foster and promote commerce, or to protect it from

9

burdens or obstructions. This principle is estab

lished by a wealth of decisions in this Court extend

ing back to Gibbons v. Ogden, 9 'Wheat. 1. Both this

Court and inferior courts have repeatedly applied the

principle to federal regulation of the activities of

retail establishments, including restaurants, where

those activities would burden or obstruct interstate

commerce. The critical inquiry in the present case,

therefore, is whether racial discrimination in a local

restaurant, as a matter of fact, burdens or obstructs

the movement of goods in interstate commerce.

That practical inquiry is primarily for Congress,

and its action is binding unless it appears to have no

reasonable relation to the authorized end. Here, the

evidence before Congress gave it ample ground for

concluding that racial discrimination in places of pub

lic accommodation that receive goods from out-of-

State sources, including restaurants, is a prolific

source of disputes and demonstrations sharply cur

tailing their business activities and reducing their

purchases of out-of-State goods. In addition, the

practice of racial discrimination in places of public

accommodation was shown drastically to curtail the

retail market and thus to restrict the demand for

out-of-State goods.

I t is irrelevant that the volume of goods purchased

by appellees’ restaurant, viewed in isolation, has

scant effect upon the total volume of goods moving in

interstate commerce. Congress was entitled to take

into account the fact that each individual situation

was representative of many others throughout the

746—011— 64----------2

10

country, the total incidence of which would be far-

reaching in its impact upon commerce. I t was also

entitled to judge the importance of the commercial

relationship between racial discrimination in restau

rants and the interstate flow of goods in the light

of the evidence that the discrimination and resulting

threat of disturbances at any one establishment are

part of a complex and interrelated national problem.

The absence of an explicit recital that Congress

found that racial discrimination in places of public

accommodation burdens interstate commerce does not

warrant the conclusion, drawn in the opinion be

low, “that Congress has sought to put an end

to racial discrimination in all restaurants wherever

situated regardless of whether there is any demonstra

ble causal connection between the activity of the par

ticular restaurant * * * and interstate commerce”

(R. 48). Except where it was dealing with discrimi

nation supported by State action in violation of the

Fourteenth Amendment, Congress prohibited discrimi

nation only in those establishments which have a close

and intimate tie to interstate commerce—in the case of

restaurants, through serving food which comes from

out of State ( Section 201 (d) ). We think this amounts

to a declared finding that in such establishments racial

discrimination burdens and obstructs interstate com

merce. But even if that affirmative inference is un

warranted, the reasoning below has a fatal gap. Those

challenging the constitutionality of an Act of Congress

must show “ that by no reasonable possibility can the

challenged legislation fall within the wide range of dis

cretion permitted to the Congress” (United States v.

11

Butler, 297 U.S. 1, 67). Formal findings may aid the

Court to understand the predicate of particular legis

lation but “ [ejven in the absence of such aids the

existence of facts supporting the legislative judgment

is to be presumed, for regulatory legislation affecting

ordinary commercial transactions is not to be pro

nounced unconstitutional unless in the light of the

facts made known or generally assumed it is of such

a character as to preclude the assumption that it rests

upon some rational basis within the knowledge and ex

perience of the legislators” (United States v. Carotene

Products Co., 304 U.S. 144, 152). Appellees have not

only failed to make such a showing but the factual

support for the legislation affirmatively appears.

For is Title I I invalidated by the absence of pro

vision for an administrative or judicial finding

whether discrimination in an individual restaurant

affects interstate commerce. United States v. Darby,

312 U.S. 100, 120-121; Labor Board v. Reliance Fuel

Co., 371 U.S. 2244

ARGUMENT

In the court below the government urged (1) that

the bill should be dismissed for want of jurisdiction

upon several grounds, among others because equity

would not enjoin the enforcement of a statute where

there was no threat to apply it to the plaintiff and no

danger of injury; and (2) that if the district court *

* The arguments presented by appellees under the First, Fifth,

Ninth, Tenth and Thirteenth Amendments are answered, so far

as appears necessary, in our brief in Heart of Atlanta Motel,

Inc. v. United States, "So. 515, this Term.

12

readied, the merits, Title I I of the Civil Rights Act of

1964 should be held constitutional.

Prom the standpoint of the immediate administra

tion of the Civil Rights Act we would welcome a de

cision upon the constitutionality of Title II as ap

plied to establishments like appellees’ restaurant.

The decision below, however, sustaining the power of

a district court to render an opinion upon the consti

tutionality of a federal statute upon the bare request

of any person who alleges that he is subject to the

Act, without any showing of irreparable injury,

threatens such serious interference with the normal

operations of the government as to require us to insist

upon the jurisdictional objection in addition to argu

ing the merits.

I

THE COMPLAINT SHOULD BE DISMISSED FOB WANT OF

EQUITY JURISDICTION

In the present case plaintiffs sued only to enjoin a

possible future suit for an injunction. Prior to the

filing of suit neither the Attorney General nor the De

partment of Justice even knew of the plaintiffs’ exist

ence, much less any of the facts bearing upon the

coverage of their restaurant under Section 201(c) (2)

and their compliance with Section 201 (a). The only

possible sanction that anyone can invoke against them

is a civil action to compel future compliance.

We know of no precedent for such a superfluous

action. Plaintiffs cannot be harmed by waiting to as

sert their contentions as defenses if and when the At

torney General (or a private party) seeks to enforce

13

the statute. Present relief is not only quite unneces

sary, therefore, to protect their interests; it is also

affirmatively harmful to the recognized and significant

public interest in avoiding premature decision of con

stitutional questions and in allowing authorized offi

cials to exercise an informed discretion in administer

ing regulatory legislation.

A. The Civil Rights Act of 1964 was carefully

drawn so as to ensure that no proprietor of a “ place

of public accommodation” would be subjected to any

sanction or liability until after the applicability of

Title I I to his business had been determined in a dis

trict court proceeding for an injunction with full op

portunity for appellate review. Title I I provides

only for enforcement by a civil action for an injunc

tion. There are no criminal or civil penalties. There

is no provision for the award of damages. Section

207(b) provides explicitly that “ [t]he remedies pro

vided in the title shall be the exclusive means of en

forcing the rights based on this title * * *.” 5 Appel

lees can incur no legal sanctions until (1) their rights

and duties under the Constitution and statute have

been determined in the federal courts and (2) they

have been ordered to comply with the statute. They

are not even subjected to the familiar choice of obey

ing the statute or incurring the risk of prosecution.

There neither is nor could be a showing that the

mere existence of the statute and the general intention

of the Attorney General to enforce it subjects ap

5 I t is possible that if outsiders conspire to prevent a restau

rant from complying with Section 201, they can be prosecuted

under 18 U.S.C. 241.

14

pellees to a threat of irreparable injury. Appellees

contend that the statute is void because it is uncon

stitutional and allege that their business and property

would suffer if they complied with the statute (Com

plaint, par. 7) ; but they are not currently complying,

do not intend to comply, and incur no risk of any

sanctions for failure to comply until after their

rights and duties have been determined in judicial

proceedings. There is also an allegation that

“ [enforcement, or attempts to enforce said Act

against plaintiffs by either defendants or by other

so-called ‘aggrieved’ persons would subject plaintiffs

to the burdens, inconvenience and expense of litiga

tion and the aggravation of such burdens and ex

penses occasioned by a potential multiplicity of suits”

(Complaint, par. 8). This allegation will not survive

analysis. An enforcement suit by the Attorney Gen

eral, if one were brought, could subject appellees to

no greater trouble or expense than their own suit

against the Attorney General; indeed, from appellees’

standpoint, the former expense was contingent at

worst whereas by prosecution of this action they

insisted upon incurring those costs. And an injunc

tion issued against the Attorney General would not

bar suits by aggrieved persons. The grounds of the

decision might discourage future litigation, but no

more so than would the grounds of decision in the

first suit for an injunction brought against appellees

under the statute. The likelihood or unlikelihood of

a multiplicity of suits is identical in both circum

stances. Nor is the possibility that an unknown per

son, at some unknown future time, may file some

15

unidentified suit, based perhaps upon new conditions^

a sufficient ground for equitable relief.

In sum, appellees have failed to show irreparable

injury or other grounds for an injunction, because

they have an entirely adequate remedy in the defense

of any action for an injunction that the Attorney

General may bring against them. The complaint is

no more than a request for an immediate advisory

opinion upon the constitutionality of Title I I of the

Civil Rights Act, having no foundation other than

the possibility that the Attorney General may, at some

future date, seek an injunction requiring appellees

prospectively to comply with the Act. Whether that

be enough for a “ case or controversy” may be open

to argument, but it is plainly insufficient to support

equity jurisdiction in a suit intended to determine

the constitutionality of a federal statute.

B. In a case wdiere a party seeks to enjoin enforce

ment of a law on constitutional grounds, the courts are

insistent not only that his claim be concrete and

ripe, but that he be able to show the threat of

immediate, irreparable injury which makes it neces

sary for equity to intervene without delay. Speaking

of a suit to enjoin a State regulatory law imposing

criminal sanctions, Chief Justice Hughes stated in

Spielman Motor Co. v. Dodge, 295 TJ.S. 89, 95:

The general rule is that equity will not inter

fere to prevent the enforcement of a criminal

statute even though unconstitutional. Hygrade

Provision Co. v. Sherman, 266 TJ.S. 497, 500.

See, also, In re Sawyer, 124 U.S. 200, 209-211;

Davis & Farnum Manufacturing Co. v. Los

16

Angeles, 189 U.S. 207, 217. To justify such

interference there must he exceptional circum

stances and a clear showing that an injunction

is necessary in order to afford adequate pro

tection of constitutional rights. See Terrace

v. Thompson, 263 U.S. 197, 214; Packard v.

Banton, 264 U.S. 140,143; Tyson v. Banton, 273

U.S. 418, 428; Cline v. Frink Dairy Co., 274

U.S. 445, 452; Ex parte Young, 209 U.S. 123,

161-162. We have said that it must appear

that “the danger of irreparable loss is both

great and immediate” ; otherwise, the accused

should first set up his defense in the state court,

even though the validity of a statute is chal

lenged. * * *

The point was restated by Chief Justice Stone in

Douglas v. City of Jeannette, 319 U.S. 157, 163-164:

I t is a familiar rule that courts of equity do

not ordinarily restrain criminal prosecutions.

No person is immune from prosecution in good

faith for his alleged criminal acts. Its immi

nence, even though alleged to be in violation of

constitutional guaranties, is not a ground for

equity relief since the lawfulness or constitu

tionality of the statute or ordinance on which

the prosecution is based may be determined as

readily in the criminal case as in a suit for an

injunction.

Similarly, the courts have repeatedly refused to

enjoin federal officials from proceeding against vio

lations of federal statutes. E.g., Yarnell v. Hills

borough Packing Co., 70 F. 2d 435 (C.A. 5) ; Ryan

v. Amazon Petroleum Corp., 71 F. 2d 1, 6 (C.A. 5) ;

Richmond Hosiery Mills v. Camp, 74 F. 2d 200 (C.A.

17

5) ; Sparks v. Mellwood Dairy, 74 F. 2d 695 (C.A. 6) ;

Board of Trade of Kansas City v. Milligan, 90 F. 2d

855 (C.A. 8). The mere fact that the government’s

law enforcement officers stand ready to perform their

enforcement duties under the Act “falls far short of

such a threat as would warrant the intervention of

equity.” Watson v. Buck, 313 U.S. 387, 400; United

Public Workers v. Mitchell, 330 U.S. 75, 88. See,

also, Lion Manufacturing Corporation v. Kennedy, 330

F. 2d 833 (C.A. D.C.).

These are some cases which indicate a softening of

the requirement that the danger of irreparable loss

be both “great and immediate.” E.g., Browder v.

Gayle, 142 F. Supp. 707, affirmed, 352 U.S. 902, and

Croivn Kosher Supermarket v. Gallagher, 176 F.

Supp. 466, reversed on other grounds, 366 U.S. 617.

Possibly Wickard v. Filburn, 317 U.S. I l l , was such

a case, although the point is not discussed in the opin

ion. We know of no decision, however, remotely sug

gesting that the bare allegation that one is covered by

an allegedly unconstitutional statute providing no

penalties and creating no sanctions save a possible

action for prospective relief is sufficient to obtain an

injunction against the normal processes of law en

forcement. To such a case as this, therefore, the

three considerations opposed to anticipatory interven

tion by equity with the processes of law enforcement

through criminal prosecution apply with still greater

force.

First, the judicial branch will not adjudicate ques

tions of constitutionality in the absence of necessity.

18

“I t must be evident to any one that the power to de

clare a legislative enactment void is one which the

judge, conscious of the fallibility of the human judg

ment, will shrink from exercising in any case where he

can conscientiously and with due regard to duty and

official oath decline the responsibility. ’ ’ 1 Cooley, Con-

stitutional Limitations (8th ed.), p. 332, quoted by

Mr. Justice Brandeis concurring in Ashwander v.

Tennessee Valley Authority, 297 U.S. 288, 341, 345.

The principle is exemplified by familiar precepts: the

Court will not pass upon the constitutionality of leg

islation in a friendly, non-adversary proceeding;6

or when the ease may be decided upon another

ground; 7 or when the action is brought by one who

fails to show that he has been injured by the opera

tion of the statute.8 The basic policy is also imple

mented by the rule barring injunction against the

enforcement of a statute by public officials where the

complainant, without risk of irreparable injury, could

wait and raise his constitutional defense in any action

brought against him.

Second, the rule is necessary to prevent interfer

ence with the normal processes of law enforcement.

I f the possibility that appellees might be sued by

the Attorney General to compel them to comply with

the statute at some indeterminate future date were

e E.g., Chicago <& Grand Trunk Ry. v. 'Wellman, 143 U.S.

339, 345.

7 E.g., Siler v. Louisville and Nashville R. Co., 213 U.S. 175,

191; Berea College v. Kentucky, 211 U.S. 45, 53.

8 E.g., Tyler v. Judges of the Court of Registration, 179 U.S.

405 ; Hendrick v. Maryland, 235 U.S. 610, 621.

19

sufficient predicate for them to bring action against

the Attorney General, any proprietor of any place of

public accommodation in the United States, who is

potentially subject to the Civil Rights Act of 1964,

could seek an advisory determination as to whether

the statute could be constitutionally applied to him.

The resources of the government are not unlimited.

I t is essential that the time and funds available for

enforcement be allocated in a manner that will best

promote the public interest. The necessity of de

fending every case in which one potentially subject

to the statute desires an advisory opinion upon its

constitutionality would interfere significantly with the

normal processes of law enforcement.

The facts in the present case are particularly strik

ing. There were, in 1958 (the last year for which

published Census figures are available),9 over 115,000

restaurants, lunch counters, and gasoline stations in

16 Southern or border States 10 which, if they meet

the statutory test of “affecting commerce,” as most

will, are places of public accommodation under Sec

tion 201(b)(2) of the 1964 Act. There are, in addi

tion, about 20,000 hotels and motels in these States

which fall under Section 201(b)(1), and another

6,000 motion picture theaters which fall under Sec

tion 201(b)(3). The Civil Rights Division of the

9 The 1958 Census of Business, compiled by the U.S. Bureau

of the Census. A similar study was made during 1963, but it

has not yet been published.

10 Texas, Louisiana, Oklahoma, Arkansas, Mississippi, Ala

bama, Tennessee, Kentucky, Florida, Georgia, South Carolina,

North Carolina, Virginia, West Virginia, Maryland, Delaware.

20

Department of Justice lias 55 lawyers to handle liti

gation under Title II, as well as all the other titles

of the 1964 Act, the 1960 Act,11 the 1957 Act,12 and the

early federal civil rights statutes.13 I t is hardly nec

essary to point out the import of these facts. The

Department of Justice can only perform its functions

under these statutes if it is free to select carefully

the. cases it will bring so as to use its limited man

power in the most effective way. The decision as to

which cases will be litigated, and where and when,

cannot be left to the private parties subject to the

public accommodations provision of the 1964 Act.

There are other important administrative considera

tions. Congress has provided in Title X of the 1964

Act for a Community Relations Service, now headed by

Governor Leroy Collins, which is intended “ to pro

vide assistance to communities and persons therein

in resolving disputes, disagreements, or difficulties

relating to discriminatory practices based ion

race * * V ’ 78 Stat. 267. I t is hoped that this ap

proach-voluntary negotiation and discussion—will

avoid the necessity of numerous legal proceedings

under Title II. The Department of Justice can co

ordinate its enforcement activities under Title I I

with the activities of the Director of the Community

Relations Service under Title X, but the efforts of

the Community Relations Service could be under

mined by untimely suits by those opposed to the

11 74 Stat. 86.

12 71 Stat. 637.

1318 U.S.C. 241, 242.

2 1

provisions of the statute and equally opposed to volun

tary compliance with desegregation.

Third, a rule allowing suit to enjoin enforcement

of the Civil Rights Act, even though the plaintiff

would be in no way harmed by awaiting the outcome

of the statutory proceedings, could not be confined

to this statute alone. The same principle would be

applicable under any other regulatory statute, such

as the Rational Labor Relations Act, the Fair Labor

Standards Act, the Securities and Exchange Commis

sion Act, etc. The potentiality for interference with

the normal administration of such laws is obvious.

Nor do we see how the principle, once established,

could be confined to suits raising constitutional issues,

unless upon the ground that the action is against the

United States where it is not alleged that the Attor

ney General is acting without constitutional author

ity.14 There would seem to be no less ground for

asserting equitable jurisdiction in the case of a claim

that a regulatory statute did not apply to a complain

ant against whom it might be enforced, or did not

outlaw his conduct, or otherwise bear an interpreta

tion which the government might put upon it.

C. The eases cited by the court below give no sup

port to the assertion of equity jurisdiction to enjoin

the enforcement of Title II. Each involved a threat

of immediate substantial injury to the plaintiff; none

even approached the present case, where the plaintiff

cannot be harmed by awaiting any proceedings

14 See Brief for the Respondent in Rabinowitz v. Kennedy,

Attorney General, No. 287, October Term, 1963, pp. 39-40.

22

against him. Indeed, the cases cited do not even pro

vide authority for the proposition that a person sub

ject to a regulatory statute with immediate penal

sanctions can obtain an adjudication as to the con

stitutionality of the statute without incurring the risk

of violation.

The majority of the cases presented situations like

that in Terrace v. Thompson, 263 17. S. 197, where the

existence of the statute imposing severe penalties

and forfeiture of the land upon one who leased farm

ing land to an alien who had not declared an intention

to become a citizen, and also upon the alien who

acquired an interest in the land, operated ex proprio

vigore to interfere with the owner’s right to dispose

of his property and the alien’s right to pursue the

occupation of farmer (263 U.S. 215-216):

The threatened enforcement of the law deters

them. In order to obtain a remedy at law,

the owners, even if they would take the risk

of fine, imprisonment and loss of property,

must continue to suffer deprivation of their

right to dispose of or lease their land to any

such alien until one is found who will join

them in violating the terms of the enactment

and take the risk of forfeiture. Similarly

Nakatsuka must continue to be deprived of his

right to follow his occupation as farmer until

a land owner is found who is willing to make a

forbidden transfer of land and take the risk of

punishment. The owners have an interest in

the freedom of the alien, and he has an interest

in their freedom, to make the lease.

The same kind of interference with an advanta

geous relationship for which there was no adequate

23

remedy at law was proved in Pierce v. Society of

Sisters, 268 U.S. 510; Euclid v. Ambler Realty Go.,

272 U.S. 365; and Public Utilities Commission of

California v. United States, 355 U.S. 534.10 The

plaintiff’s interest in, and need for, an equitable

remedy is obvious where the statute imposes criminal

penalties on those engaged in business dealings with

the plaintiff unless they discontinue their dealings.

Then there is no adequate remedy at law, for the

plaintiff cannot require those dealing with him to

risk criminal penalties to test the validity of the

statute.

In Pennsylvania v. West Virginia, 262 U.S. 553,

both States were seeking to withdraw natural gas from

the same pool under circumstances in which the with

drawal by one would cause widespread injury in the

other. Carter v. Carter Coal Co., 298 U.S. 238, was

not a suit against the Attorney General to enjoin en

forcement but a minority stockholder’s bill to enjoin

the corporation from complying with the statute; in

any event, irreparable harm was threatened. The

point was not raised in Adler v. Board of Education,

342 U.S. 485, undoubtedly because the action had been

brought in a State court and presented no question

of federal equity jurisdiction. In Currin v. Wallace, 15

15 In Public Utilities Commission of California v. United

States, 355 U.S. 534, the Court did not discuss the irreparable

injury, but the theory of equity jurisdiction clearly appears from

the Brief for the United States, No. 23, October Term 1&57,

pp. 23, 27.

24

306 U.S. 1, the opinion of the lower court clearly

shows that the plaintiffs would have incurred penal

ties “which would be ruinous to them” if they violated

the statute and its constitutionality were.upheld (95

F. 2d 856, 861). In short, none of the cases relied

upon by the court below provide support for the pres

ent case, where the plaintiffs have not even shown that

they have been harmed in any way by the operation of

the statute.

I I

SECTION 201 OP THE CIVIL RIGHTS ACT OF 1964 , AS AP

PLIED TO a p p e l l e e ’s RESTAURANT, IS A VALID EXERCISE

OF THE COMMERCE POWER

In our brief in Heart of Atlanta Motel, Inc. v.

United States, Ho. 515, this Term, we outlined the

general plan of Title I I of the Civil Rights Act of

1964 which grants all persons a right to the full and

equal enjoyment of the goods, services or facilities of

any “place of public accommodation” as defined

therein, and we endeavored to show that, both in gen

eral plan and in specific application to hotels and

motels, Title I I is a valid exercise of the power to

regulate interstate commerce. In this case we deal

with the application of Title I I to a restaurant which

serves the general public and receives the products

which it sells from other States.16

Section 201 (b) and (c) define as a place of public

accommodation subject to the duty to make its goods,

16 The challenges to Title I I based upon the Fifth, Ninth,

Tenth and Thirteenth Amendments are answered in our Heart

of Atlanta brief. Appellees’ argument based upon the First

Amendment requires no response. - -

25

services and facilities available without regard to race

or color—

any restaurant, cafeteria, lunchroom, lunch

counter, soda fountain, or other facility engaged

in selling food for consumption on the premises

if—

a substantial portion of the food which it serves

* * * has moved in commerce.

Appellees allege that their restaurant is covered by

the foregoing provision and that they are, neverthe

less, engaged in racial discrimination. We accept the

allegations. The district court found that in the

twelve months preceding the passage of the Civil

Eights Act of 1964 appellees purchased approximately

$150,000 worth of food locally, but that about 46 per

cent of its purchases were meat which had been

shipped in to the local packer and -wholesaler from

outside the State of Alabama (E. 36). The govern

ment on its part agreed in the lower court that the

discrimination at appellees’ restaurant was not being

supported by the State of Alabama within the mean

ing of Section 201(d). Thus, the question is whether

Title II, as applied to a restaurant receiving about

$70,000 worth of food indirectly from outside the

State, is a valid exercise of the power of Congress to

regulate interstate commerce (Art. I, Sec. 8, cl. 3)

and to enact all laws necessary and proper for the

execution of the commerce power (Art. I, Sec. 8, cl.

18). The Civil Rights Cases, 109 U.S. 3, throw no

light upon the issue because the Civil Eights Act of

748 011 - 8-5— ----8

26

1875, 18 Stat. 335, was not conceived or sought to be

justified under the commerce power.17

The major premise of our argument is the familiar

rule that the powers thus delegated to Congress ex

tend to local activities, even though they are not

themselves interstate commerce, if they have such a

close and substantial relation to interstate commerce

that their regulation is appropriate to foster or pro

mote such commerce, or to relieve it from burdens or

obstructions. The minor premise of our argument

is that Congress, to which the economic question is

primarily committed, had ample basis upon which

to find that racial discrimination at restaurants which

receive from out-of-State a substantial portion of. the

food served does in fact impose commercial burdens

of national magnitude upon interstate commerce.

17 The opinion below states that the court had been advised

that the Solicitor General, in brief, had urged upon the Su

preme Court the sufficiency of the grant of power in the com

merce clause to sustain the challenged legislation. Evidently

the court was partially misinformed. The brief filed by Solici

tor General Phillips at the October Term, 1882, makes no such

argument, nor is any contained in the summary of his oral

argument in the United States Eeports, 109 U.S. 3, 5-7. At

the October Term, 1879, a brief had been filed in three of the

cases by Attorney General Devens. One sentence stated that

inns were essential instrumentalities of commerce, which it

was the province of the United States to regulate prior to the

Civil War amendments. This appears to have been a passing

comment for the entire thrust of the brief lies in the proposi

tion that the power to enact the Civil Eights Act of 1875 was

granted by Section 5 of the Fourteenth Amendment.

27

A. TH E POWER TO REGULATE INTERSTATE COMMERCE EXTENDS TO

LOCAL ACTIVITIES WHOSE REGULATION IS APPROPRIATE TO PRO

TECT INTERSTATE COMMERCE PROM BURDENS OR OBSTRUCTIONS

1. The power of Congress is not confined to the regulation of

the course of interstate commerce but extends to matters sub

stantially affecting it

Article I, Section 8, clause 3 confers upon Con

gress the power “To regulate Commerce * * * among

the several States.” Clause 18 of the same Article

grants the power “ To make all Laws which shall be

necessary and proper for carrying into Execution

the foregoing Powers * * Under those provi

sions the Congress has ample power not only to regu

late interstate travel, transportation' and communi

cation, but also to deal with other matters which sub

stantially affect such commerce even though they

might be local when viewed in isolation. “The com

merce power,” Chief Justice Stone held for a unani

mous court in United States v. Wrightwood Dairy

Go., 315 U.S. 110, 119, “is not confined in its exercise

to the regulation of commerce among the states. I t

extends to those activities intrastate. which so affect

interstate commerce, or the exertion of the power of

Congress over it, as to make the regulation of them

appropriate means to the attainment of a legitimate

end, the effective execution of the granted power to

regulate interstate commerce.” Mr. Justice Jackson,

also speaking for a unanimous court, restated the

principle in Wickard v. Filburn, 317 U.S. I l l , 125, in

words precisely applicable to the present ease:

* * * even'if appellee’s activity be looted and

though it may not be regarded as commerce, it

746- 011— 64— 4

28

may still, whatever its nature, be reached by

Congress if it exerts a substantial economic

effect on interstate commerce, and this irre

spective of whether such effect is what might

at some earlier time have been defined as

“direct” or “indirect.”

See, also, Labor Board v. Jones & Laughlin Steel

Corp., 301 U.S. 1, 37; United States v. Darby, 312

U.S. 100, 119; Labor Board v. Reliance Fuel Corp.,

371 U.S. 224, 226-227.

There is no novelty in this principle, nor was it

new in the cases cited above. The principle was

established by Chief Justice Marshall, speaking for

the Court in Gibbons v. Ogden, 9 Wheat. 1, 195, one

hundred and forty years ago:

The genius and character of the whole govern

ment seem to be, that its action is to be applied

to all those external concerns of the nations

and to those internal concerns which affect the

States generally * * *. [Emphasis added.]

In describing the local activities which Congress

could not regulate he was careful to exclude from

the definition—and thus mark as within the federal

commerce power—those local activities which affect

other States and with which it is necessary to deal in

order to regulate interstate commerce. Thus, he

described the local activities removed from federal

action as ibid.—

those which are completely within a particular

State, which do not affect other States, and

with which it is not necessary to interfere, for

the purpose of executing some of the general

powers of the government. . ..

29

Although the subsequent course of decision included

some departures from the original principle,18 the prin

ciple found frequent application even prior to the

Labor Board cases and other decisions cited above.

I t was applied to violence shutting down production

at a coal mine whence coal might be shipped in inter

state commerce, Coronado Coal Co. v. United Mine

Workers, 268 U.S. 295, to the activities of a local grain

exchange shown to have an injurious effect upon inter

state commerce, Chicago Board of Trade v. Olsen,

262 U.S. 1, to regulation of the intrastate rates of

interstate carriers, Houston & Texas By. v. iUnited

States, 234 U.S. 342; Railroad Comm, of Wisconsin v.

Chicago B. & Q. R. Co., 257 U.S. 563, to the safety

devices upon rolling stock moving in local commerce,

Southern Ry: Co. v. United States, 222 U.S. 20, and

to the regulation of hours worked by employees en

gaged in intrastate activity related to the movement

of any train, Baltimore dc Ohio R. Co. v. Interstate

Commerce Commission, 221 U.S. 612. In United

18 The chief departures are United States- v. E. C. Knight,

156 U.S. 1 (rejected in Standard Oil Co. v. United States. 221

U.S. 1, 68-69, and Labor Board v. Jones &Laughlin Steel Gory.,

301 U.S. 1, 38-39); Adair v. United States, 208 U .S.'161 (sub

stantially overruled in Texas and New Orleans- Railroad v.

Brotkmhood of Railway and .Steamship Clerics, 281 U.S; 548;

Virginian Railway v. System Federation No. Jfi, 300 U S. 515);

Railroad Retirement Board v. Alton R. Co., 295 U.S. 330 (dis

approved in United States v. Lovyden, 308 U.S. 225, 239); First

Employers’ Liability Cases, 207 U.S. 463 (disapproved in Vir

ginian Ry. v. System Federation No. 40, 300 U.S. 515, 557),

Carter v. Carter Coal Co., 298 U.S. 238 (disapproved in United

States v. Darby, 312 U.S. 100, and overruled in Wiolcard v. Fil-

burn. 317 U.S. I l l , 122, n. 21); Hammer v. Da.genhart, 247 U.S.

251 (overruled in United States v. Darby, 312 B.S. 100, 117).

30

States v. Ferger, 250 U.S. 199, 203, Mr. Chief Justice

White pointed out that the power of Congress “must

include the authority to deal with obstructions to inter

state commerce (In re Debs, 158 U.S. 564) and with a

host of other acts which, because of their relation to

and influence upon interstate commerce, come within

the power of Congress to regulate, although they are

not interstate commerce in and of themselves. ”

There was comparatively little federal regulation of

interstate commerce in the nineteenth century. The

need and therefore the volume of legislation increased

greatly in the present century. Furthermore, the in

creasing interdependence of all parts of the economy

and changes in commercial practices have, in fact,

linked to interstate commerce through close and sub

stantial connections many activities which, as a matter

of fact, had no effect upon such commerce in earlier

years. This is the reason the governing principle has

found its clearest application in decisions sustaining

modern economic legislation. The principle, however,

as shown by the Court’s opinion in Gibbons v. Ogden,

is.as old as the Constitution itself. '■

g. The. power to regulate local matters substantially affecting

interstate commerce extends to retail establishments includ

ing restaurants . -

A host of familiar precedents sustains the power of

Congress to regulate the. activities of retail establish

ments, including restaurants,, which directly or indi-

* rectly receive goods from out of State,- where those

‘ activities burden or obstruct , interstate commerce. In

Labor Board x. Reliance Fuel C'orp,, 371 U.S. 224, this

31

Court held that the National Labor Relations Board

had jurisdiction over unfair labor practices committed

by a retail distributor of fuel oil, all of whose sales

were local, where the retailer obtained the oil from a

wholesaler who imported it from another State. That

decision accords with a long series of cases basing

federal power over the labor relations of a retail busi

ness on the threat to the market for interstate goods

caused by unfair labor practices that may decrease

its purchase of goods originating in other States.

See, e.g., Labor Board v. Denver Bldg. Council, 341

U.S. 675, 683-684; May Department Stores Co. v.

Labor Board, 326 U.S. 376 (retail store) ; J. L. Bvan-

dais & Sons v. Labor Board, 142 F. 2d 977 (C.A. 8),

certiorari denied, 323 U.S. 751 (retail store) ; McLeod

v. Bakery Drivers Local, 204 P. Supp. 288 (E.D. N.Y.)

(bakery) ; Retail Fruit <& Vegetable Union v. Labor

Board, 249 P. 2d 591 (C.A. 9) (retail store) ; In t’l

Brotherhood v. Labor Board, 341 U.S. 694 (construc

tion project) ; Local 74 v. Labor Board, 341 U.S. 707

(store, dwelling renovation) ; Meat Cutters v. Fairlawn

Meats, 353 U.S. 20 (retail grocery).

In particular, the Labor Board has on many occa

sions regulated labor relations in restaurants, on the

theory that disputes in restaurants tend to diminish

the quantity of food and other products purchased by

the restaurant to serve its customers. See, e.g., Labor

Board v. Morrison Cafeteria Co. of Little Rock, 311

P. 2d 534 (C.A. 8) ; Labor Board v. Local Joint Exec...

Board, 301 P. 2d 149 (C.A. 9) ; Labor Board v. Childs

Co., 195 F. 2d 617 (C.A. 2) ; Labor Board v. Laundry

3 2

Drivers Local, 262 F. 2d 617 (C.A. 9); Labor Board

v. Gene Compton’s Corp., 262 F. 2d 653 (C.A. 9);

Labor Board v. Howard Johnson Co., 317 F. 2d 1

(C.A. 3), certiorari denied, 375 TJ.S. 920; Kennedy v.

Los Anegeles Joint Exec. Board, 192 F. Supp. 339

(S.D. Cal.) ; Culinary Workers & Bartenders Union v.

Labor Board, 310 F. 2d 853 (C.A.D.C.); Smitley v.

Labor Board, 327 F. 2d 351 (C.A. 9) ; Stanton Enter

prises, Inc., 147 NLRB No. 81, A CCH Lab. L. Rep.

21,075, para. 13,211; Stork Restaurant, Inc. v. McLeod,

312 F. 2d 105 (C.A. 2) ; McLeod v. Chefs, Cooks,

Pastry Cooks & Assistants Union, 280 F. 2d 760 (C.A.

2); McLeod v. Chefs, Cooks, Pastry Cooks & As

sistants Local 89, 286 F. 2d 727 (C.A. 2).19

As pointed out in more detail, with appropriate

citation of precedents, in our brief in Heart of A t

lanta Motel, Inc. v. United States, No. 515, pp. 33-36,

the same principle has been applied under the Sher

man and Federal Trade Commission Acts.

3. Cases Holding that, interstate commerce ends when goods

“come to rest’’' in a State are irrelevant to the power of

Congress to regulate local activities which substantially

burden interstate commerce

Implicit in what we have already said is the dis

tinction between the present case and cases holding

that interstate commerce ends when goods come to

rest in the State of destination. When the issue is

whether the goods are immune from State taxation,

19 See also, Brermamls French Restaurant, 129 N.L.R.B. 52;

Joe Hunt's Restaurant, 138 N.L.R.B. 470; Childs Co., 88

N.L.R.B 720; Childs Co., 93 N.L.R.B. 281; Bolton & Hay,

100 N.L.R.B. 361; The Stauffer Corp., 101 N.L.R.B. 1331; Mil-

Bur, Inc., 94 N.L.R.B. 1161.

33

or whether the States may not regulate the conduct

because of the need for uniformity, then it may be

pertinent to ask whether the goods have ceased to be

part of interstate commerce,20 for the commerce clause

does not operate ex proprio vigore to exclude State

taxation or State regulation of activities which are

not part of, but affect, interstate commerce. The

question is not dispositive, however, in judging the

reach of the federal power to regulate, for federal

power extends, under the principles stated above, to

activities which are outside the stream of commerce

but substantially affect it. Thus, there are many

instances in which a State may tax or regulate goods

and activities which are also regulated by federal law.

See, e.g., South Carolina State Highway Dept. v.

Barnwell Bros., 303 U.S. 177; Mints v. Baldwin, 289

TT.S. 346.21

20 The continued vitality of the “come to rest” doctrine is

open to question in the field of State taxation, but the change

is towards the enlargement of State power. Compare, e.g.,

Broton v. Maryland, 12 Wheat. 419, and Hooven <& Allison

Co. v. Evatt, 324 U.S. 652, with Woodruff v. Parham., 8 Wall.

123, and Youngstown Sheet & Tube Co. v. Bowers, 358 U.S.

534.

21 Although a State may tax a retail sale of drugs which

were originally imported from other States (Woodruff v. Par

ham, 8 Wall. 123), Congress may regulate that sale ( United

States v. Sullivan, 332 U.S. 689). While goods stored in a

warehouse have come sufficiently to rest to be subject to a

State property tax (Woodruff v. Parham, supra), their storage

is also subject to federal regulation (United States v. Wieseru-

feld Warehouse Co., 376 U.S. 86). In each of these cases the

goods have in some sense “come to rest” after an interstate

sale and transportation, but the power of Congress to regulate

subsequent sales or use of the goods continues.

34

Such cases as Weigle v. Curtice Bros. Co., 248 U.S.

285,; Pacific States Box and Basket Co. v. White,

296 U.S. 176, and Packer Corp. v. Utah, 285 U.S. 105,

relied upon by the State of Florida (Brief Amicus

Curiae, pp. 30-33), are therefore irrelevant.

United States v. Yellow Cab Co., 332 U.S. 218,

presented a similar issue (although it was decided in

a statutory and not m a constitutional context). Be

cause the government did not allege or prove that a

monopoly of local taxi service would substantially

interfere with or burden other interstate commerce,

it was necessary to the government’s case to show

that the monopoly was a restraint of the channels

of interstate travel itself, i.e., that the taxis which

carried passengers to and from the railroad stations

as part of a general local business were themselves

instrumentalities of interstate commerce. The Court

was therefore called upon to “ mark the beginning

and end of a particular kind of interstate commerce

by its own practical considerations” (332 U.S. at

231), and it concluded that interstate travel began

and ended “at the station.” The opinion also makes

it clear, however, that the Court did not hold that

the business of operating taxis was beyond the scope

of federal regulation (id. at 232-233). The latter

question depends, as in other cases, upon whether

the activities in fact burden or obstruct, or otherwise

affect, interstate commerce. Superior Court of

Washington v. Yellow Cab Co., 361 U.S. 373, sum

marily reversed a State injunction on the ground that

the National Labor Relations Board has exclusive

35

jurisdiction over unfair labor practices of a similar

taxi service.

B. RACIAL DISCI! IM IN AT'ION IN RESTAURANTS SELLING FOOD FROM

OUT-OF-STATE SOURCES BURDENS AND OBSTRUCTS INTERSTATE

COMMERCE

Under the principle developed above, the power of

Congress to prohibit racial discrimination in restau

rants which receive a substantial portion of the food

they serve directly or indirectly from out-of ■‘•State

sources depends upon whether such discrimination

would in fact burden or obstruct the movement of

goods in interstate commerce. What affects com

merce is a practical inquiry to be answered from the

course of business. Cf. Swift & Go. v. United States,

196 U.S. 375, 398 (“commerce among the States

is not a technical legal conception, but a practical

one, drawn from the course of business” ). The

practical inquiry, moreover, is primarily for Con

gress. As the Court said in Norman v. Baltimore

and Ohio R. Go., 294 U.S. 240, 311, speaking of

whether the gold clauses in private bonds sufficiently

interfered with the monetary policy of Congress to