Slade v Harford County BOE Brief and Appendix for the Appellees

Public Court Documents

December 27, 1957

130 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Slade v Harford County BOE Brief and Appendix for the Appellees, 1957. 65b406a9-c49a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/be400cf9-fa33-40cc-bdb0-fafb18ef4df4/slade-v-harford-county-boe-brief-and-appendix-for-the-appellees. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

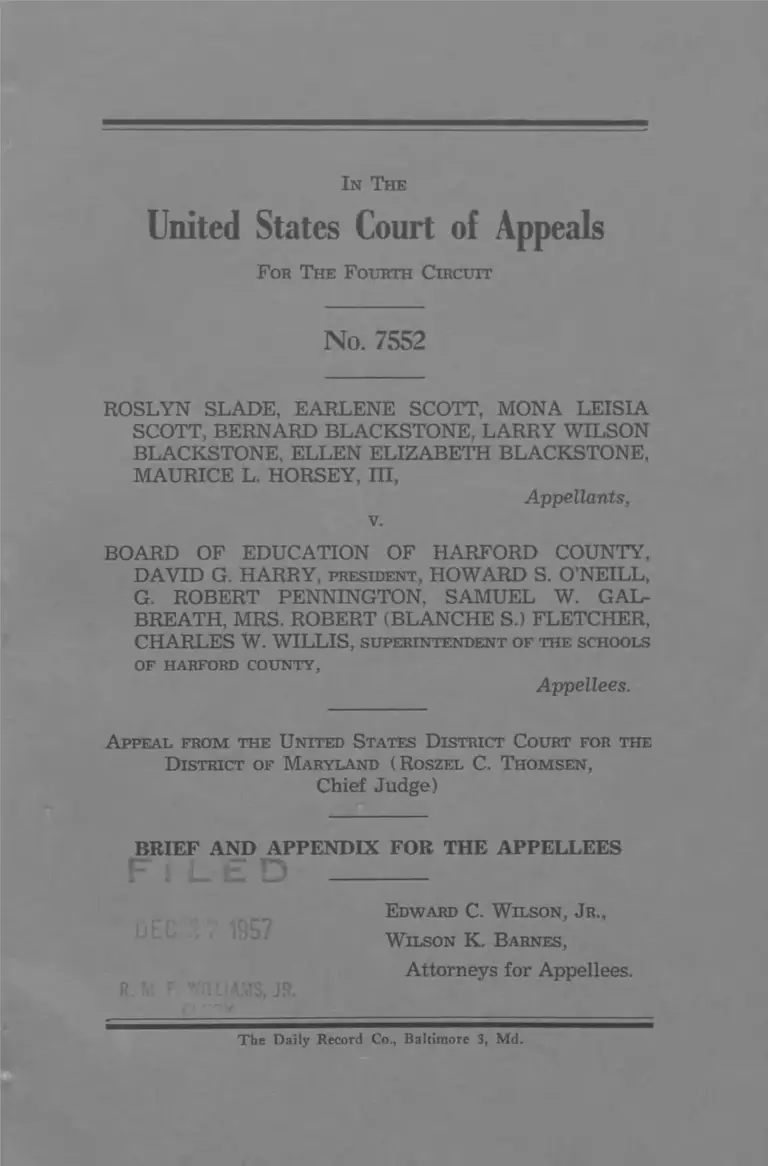

In The

United States Court of Appeals

For The Fourth Circuit

No. 7552

ROSLYN SLADE, EARLENE SCOTT, MONA LEISIA

SCOTT, BERNARD BLACKSTONE, LARRY WILSON

BLACKSTONE, ELLEN ELIZABETH BLACKSTONE,

MAURICE L. HORSEY, III,

Appellants,

v.

BOARD OF EDUCATION OF HARFORD COUNTY,

DAVID G. HARRY, president, HOWARD S. O’NEILL,

G. ROBERT PENNINGTON, SAMUEL W. GAL-

BREATH, MRS. ROBERT (BLANCHE S.) FLETCHER,

CHARLES W. WILLIS, superintendent of the schools

OF HARFORD COUNTY,

Appellees.

A ppeal from the United States District Court for the

D istrict of Maryland (R oszel C. Thomsen,

Chief Judge)

BRIEF AND APPENDIX FOR THE APPELLEESy

Edward C. W ilson, Jr.,

W ilson K. Barnes,

Attorneys for Appellees.

The Daily Record Co., Baltimore 3, Md.

I N D E X

Table of Contents

p a g e

Statement of the Case and Opinions Below 1

Question Involved ...................................................... 2

A ppellees Supplementary Statement of Facts 3

1. The Maryland Statutes....................................... 3

2. Actions of the Attorney General of Maryland

and of the State Board of Education subsequent

to the Second Opinion in the Brown case 7

3. Actions by the Board of Education of Harford

County subsequent to June 22, 1955 8

4. Hearing of November 14, 1956 .......................... 14

5. Proceedings before the State Board 18

6. Action of County Board on February 6, 1957 21

7. Hearing of April 18, 1957 in the District Court 22

8. Hearing of June 11, 1957 in the District Court 23

9. Opinion of June 20, 1957 and Judgment of July

3, 1957 ................................................................... 24

Argument .................................................................... 24

Conclusion .............................................................. 44

Table of Citations

Statutes

Annotated Code of Maryland (1951 Edition):

Article 77:

Sections 1 to 208 ............................................. 3-6

Act of 1865, Chapter 160............................................... 4

Art of 1872, Chapter 377 ............................................... 4

IX

Rules

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure:

52(a) .......................................

PAGE

24

Cases

Aaron v. Cooper,

143 F. Supp. 855 .................................................... 40

243 F. 2d 361 ......................................................31, 40, 41

Booker v. Tennessee Board of Education, 240 F. 2d

689 .......................................................................... 39,40

Briggs v. Elliott, 132 F. Supp. 776 ............................ 27, 29, 30

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka (Second

Opinion) 349 U. S. 294, 75 S. Ct. 753, 99 L. Ed.

1083 ........................................................7,8,27,28,29,30

Carson v. Board of Education of McDowell County,

227 F. 2d 789 ......................................................... 27, 29

Carson v. Warlick, 238 F. 2d 724 ................................ 27, 29

Clemons v. Board of Education of Hillsboro, 228 F.

2d 853 .................................................................... 39

Hood v. Board of Trustees of Sumter County School

District No. 2, 232 F. 2d 626 ................................ 27, 29

Jackson v. Rawdon, 235 F. 2d 93 ................................ 30

Moore, et al v. Board of Education of Harford County,

et al, Civil Action No. 8615 ................................ 10

Moore, et al v. Board of Education of Harford County,

et al,

146 F. Supp. 91 ............................................2, 24, 25

152 F. Supp. 114.......................................... 2, 24, 25

New York Life Ins. Co. v. Tobin, 177 F. 2d 176.......... 24

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537, 16 S. Ct. 1138, 41

L. Ed. 256 ............................................................... 31

Robinson v. Board of Education of St. Mary’s County,

143 F. Supp. 481 .................................................. 3

School Board of City of Charlottesville, Va. v. Allen,

240 F. 2d 59 30

iii

PAGE

School Board of the City of Newport News, Va. v.

Atkins, 246 F. 2d 325.............................................. 30

U. S. v. National Association of Real Estate Boards,

339 U. S. 485, 70 S. Ct. 711, 94 L. Ed. 1007 24

Willis v. Walker, 136 F. Supp. 177.............................. 32

Other Authorities

Opinions of Attorney General (of Maryland):

Vol. 40, page 175 .................................................. 7

Index to A ppendix

A pp.

p a g e

Hearing of November 14, 1956 ................................... 1

Testimony of:

Charles W. Willis—

Direct Examination by Mr. Greenberg.......... 1

Cross Examination by Mr. Barnes ................. 9

Examination by the Court................................ 16

David G. Harry—

Direct Examination by Mr. Barnes................. 21

Cross Examination by Mr. Watts..................... 23

Ernest Volkart—

Direct Examination by Mr. Barnes................. 26

Hearing of April 18,1957:

Testimony of:

Charles W. Willis—

Examination by the Court................................ 28

Hearing of June 11, 1957:

Statements by Counsel ........................................... 37

A p p .

PAGE

Testimony of:

Charles W. W illis-

Direct Examination by Mr. Barnes................. 38

Examination by the Court................................ 46

Excerpts from Documentary Exhibits:

Resolution of Citizens Consultant Committee of

February 27, 1956 .................................................. 49

Transfer Policy of County Board of June 14, 1956 50

Desegregation Policy of County Board of August 1,

1956 ........................................................................ 51

Opinion of Attorney General of Maryland of June

20, 1955 ................................................................... 53

Joint Resolution of State Board of June 22, 1955 .... 55

Extension of Desegregation Policy of County Board

of February 6, 1957 .............................................. 58

Proceedings before State Board on February 27, 1957 59

Statement of Chairman ........................................... 60

Testimony o f:

Charles W. W illis -

Direct Examination by Mr. Barnes................ 61

David G. Harry, Jr.—

Direct Examination by Mr. Barnes................ 69

Opinion and Order of State Board of March 4, 1957 70

Review and Specification of Desegregation Policy by

County Board of May 1,1957 ................................ 76

Letter from Mrs. Juanita Jackson Mitchell to Wilson

K. Barnes, dated May 2, 1957 ............................ 78

Modification of Desegregation Policy by County

Board in regard to High Schools during transi

tion period of June 5, 1957 ................................... 78

iv

I n T h e

United States Court of Appeals

For The Fourth Circuit

No. 7552

ROSLYN SLADE, EARLENE SCOTT, MONA LEISIA

SCOTT, BERNARD BLACKSTONE, LARRY WILSON

BLACKSTONE, ELLEN ELIZABETH BLACKSTONE,

MAURICE L. HORSEY, III,

Appellants,

v.

BOARD OF EDUCATION OF HARFORD COUNTY,

DAVID G. HARRY, president, HOWARD S. O’NEILL,

G. ROBERT PENNINGTON, SAMUEL W. GAL-

BREATH, MRS. ROBERT (BLANCHE S.) FLETCHER,

CHARLES W. WILLIS, superintendent of the schools

OF HARFORD COUNTY,

Appellees.

A ppeal from the United States D istrict Court for the

D istrict of Maryland (R oszel C. Thomsen,

Chief Judge)

BRIEF FOR THE APPELLEES

STATEMENT OF THE CASE AND

OPINIONS BELOW

This is an Appeal by one Original infant colored Plaintiff

and six infant Intervening colored Plaintiffs from a Judg

ment entered on July 3, 1957 by the United States District

Court for the District of Maryland (Thomsen, C.J.), ap

2

proving a Plan as outlined in the Judgment for the desegre

gation of the public schools of Harford County, Maryland.

The Appellees (Defendants below) are the Board of Edu

cation of Harford County; David G. Harry, President of

that Board, Howard S. O’Neill, G. Robert Pennington, Sam

uel W. Galbreath, Mrs. Robert (Blanche S.) Fletcher, who

are members of the Board of Education; and, Charles W.

Willis, Superintendent of the Schools of Harford County.

There were three substantial hearings before the District

Court (in addition to two pre-trial conferences), at which

oral testimony was taken and documentary evidence of

fered. There was also a substantial hearing before the

Maryland State Board of Education. Judge Thomsen wrote

two full Opinions. One was filed on November 23, 1956,

App.1 4a to 15a, 146 F. Supp. 91. The other Opinion was

filed on June 20, 1957, App. 16a-25a, 152 F. Supp. 114.

QUESTION INVOLVED

Were the findings by the District Court (Thomsen, C.J.)

that the Board of Education of Harford County, Maryland

had made a prompt and reasonable start toward the de

segregation of the Public Schools of Harford County and

that additional time was necessary to effectuate such de

segregation as set forth in the District Court’s Judgment

of July 3, 1957 clearly erroneous?

The Appellees maintain that Judge Thomsen’s findings

were not clearly erroneous; on the contrary, they were

clearly in accordance with the great weight of the evidence.

1 The reference “ App.” will be to the Appellants’ Appendix. The

reference to the Appellees’ Appendix will be referred to as “ Appellees’

App............

3

APPELLEES’ STATEMENT OF THE FACTS IN

ADDITION AND SUPPLEMENTAL TO THE

STATEMENT OF THE FACTS OF

THE APPELLANTS

The Statement of Facts by the Appellants omits much of

the background of the present case and the Appellants’

Appendix omits much of the relevant testimony and pro

ceedings. The Appellees deem it necessary to amplify the

Appellants’ Statement.

1. The Maryland Statutes

Chief Judge Thomsen carefully and fully analyzed the

applicable Maryland Statutes in regard to the Maryland

Public School System in his Opinion in Robinson v. Board

of Education of St. Mary’s County, 143 F. Supp. 481 (July

9, 1956). In the Robinson case, as in the case at bar, Judge

Thomsen indicated that the Plaintiffs must first exhaust

their administrative remedy by appeal to the State Board

of Education, before the District Court would proceed with

a decision in the case. The Robinson decision was not ap

pealed to this Court which has not had the Maryland Statu

tory provisions in regard to the Maryland Public School

System before it for consideration.

For the convenience of the Court and without attempt

ing to repeat the excellent analysis by Judge Thomsen

in the Robinson case, a brief summary of the Maryland

Statutes is presented.

Article 77 of the Annotated Code of Maryland (1951 Edi

tion) contains the relevant statutory provisions establish

ing in Maryland “a general system of free public schools;

according to the provisions of this Article” (Sec. 1).

This Article in substantially its present form providing

for “separate but equal” schools for white and colored

4

pupils, came into the Maryland law by the Act of 1872,

Chapter 377. The original Maryland Statute providing for

public schools on a state-wide basis was the Act of 1865,

Chapter 160 (passed March 24, 1865), which provided for

separate schools for white and colored pupils, with a pro

vision, however, that expenditures for colored schools

should be limited to school taxes collected from colored

taxpayers, together with such donations as might be given

for colored school purposes. As indicated this latter pro

vision was eliminated by the Act of 1872, Chapter 377.

Sections 2, 3 and 4 of Article 77 provide that “educational

matters affecting the State and the general care and super

vision of public education shall be entrusted to a State

Department of Education, at the head of which shall be a

State Board of Education” (Sec. 2); “educational matters

affecting a County shall be under the control of a County

Board of Education” (Sec. 3) and “educational matters

affecting a school district shall be under the care of a Dis

trict Board of School Trustees” (Sec. 4).

Sections 16 and 17 set forth the general supervisory and

appellate powers of the State Board. These powers include:

1. The enforcement of the provisions of Article 77.

2. The determination of the educational policies of the

State.

3. The enactment of by-laws for the administration of the

public school system having the force of law.

4. The institution of legal proceedings if necessary to

enforce Article 77.

5. The explaining of “the true intent and meaning of the

law, and they shall decide, without expense to the

parties concerned, all controversies and disputes that

arise under it, and their decision shall be final”.

5

6. The exercise, through the State Superintendent, of

“general control and supervision over the public

schools and educational interest of the State” .

7. Consultation with and advice to “County boards of

education” and other designated officials.

The State Superintendent, by Sec. 35, is charged with the

enforcement of all provisions of Article 77 and the by-laws

of the State Board.

Sections 46 to 71 of Article 77 contain the statutory pro

visions in regard to the County Boards of Education. These

County Boards are required “to maintain a uniform and ef

fective system of public schools throughout their respective

Counties (Sec. 48). The County Superintendent of Schools

is made the executive officer, secretary and treasurer of

the County Board (Sec. 50). The County Board “shall to

the best of its ability cause the provisions of this Article,

the by-laws, and the policies of the state board of educa

tion to be carried into effect.” Subject to Article 77, the

by-laws and policies of the State Board, the County Board

“shall determine, with and on the advice of the county

superintendent, the educational policies of the County and

shall prescribe rules and regulations for the conduct and

management of the schools” (Sec. 51). The County Board

is required to “consolidate schools wherever in their judg

ment it is practicable, and to pay, when necessary, for the

transportation of pupils to and from such consolidated

schools.”

The County Superintendent, as executive officer of the

County Board, is required to “see that the laws relating to

schools, the enacted and published by-laws of the State

Board of Education and the rules and regulations and the

policies of the county board of education are carried into

6

effect” (Sec. 143), and he “shall explain the true intent

and meaning of the school laws, and of the by-laws of the

State Board of Education. He shall decide, without expense

to the parties concerned, all controversies and disputes in

volving the rules and regulations of the county Board of

education and the proper administration of the public

school system in the county, and his decision shall be final,

except an appeal may be had to the State Board of Edu

cation if taken in writing within thirty days” (Sec. 144).

The statutory provisions in regard to the establishment

of schools for white students are found in Sections 84 and

124 which provide that elementary schools “shall be free

to all white youths between six and twenty years of age”

and that “All white youths between the ages of six and

twenty-one years shall be admitted into such public schools

of the State, the studies of which they may be able to pur

sue; provided, that whenever there are grade schools, the

principal and the County Superintendent shall determine

to which schools pupils shall be admitted.”

Sections 207 and 208 provided for the establishment of

schools for colored students. By these Sections, the duty is

placed upon the County Board “to establish one or more

public schools in each election district for all colored youths,

between six and twenty years of age, to which admission

shall be free * * *, provided, that the colored population in

any such district shall, in the judgment of the county board

of education, warrant the establishment of such a school or

schools; (Sec. 207) and that “schools for colored children

shall be subject to all the provisions of this Article” (Sec.

208).

7

2. Actions of the Attorney General of Maryland and of the

State Board of Education Subsequent to the

Second Opinion in the Brown Case.

The Second Opinion in the Brown case, Brown v. Board

of Education of Topeka, 349 U. S. 294, 75 S. Ct. 753, 99 L. Ed.

1083, was filed on May 31, 1955.

The State Superintendent of Schools (Dr. Thomas G.

Pullen, Jr.) very shortly after this decision requested an

Opinion of the Attorney General of Maryland in regard to

the effect of the Brown decision upon the provisions of the

State Law requiring separation of the races in the public

schools of Maryland.

On June 20, 1955, just twenty days after the filing of the

second Opinion in the Brown case, the Attorney General of

Maryland rendered a formal Opinion (published in the

Daily Record of June 29,1955) in which he stated that “ * * *

all constitutional and legislative acts of Maryland requir

ing segregation in the public schools of the State of Mary

land are unconstitutional and must be treated as nullities.”

(Emphasis supplied.)

The Attorney General also stated that even though the

State of Maryland were not a formal party to the Brown

and companion litigation, “We do not believe that differ

ences in the mechanics of obtaining relief can limit in any

sense the legal compulsion presently existing on the appro

priate school authorities of the State of Maryland to make

‘a prompt and reasonable start’ toward the ultimate elim

ination of racial discrimination in public education.” Report

and Official Opinions of the Attorney General, (of Mary

land) Vol. 40, page 175.

The State Board did not defy or seek to evade this opinion

of the Attorney General of Maryland.

8

On the contrary, two days later, on June 22, 1955, the

State Board passed a Resolution, in which, after various

recitals, it stated:

“Now that the Supreme Court has passed its man

date and has directed compliance with its decree with

deliberate speed and with due regard to local condi

tions and in conformity with equitable considerations,

the State Board of Education calls upon the local public

school officials to commence this transition at the earli

est practicable date, with this view of implementing

the law of the land.” (Emphasis supplied.)

In the same resolution the Staff of the State Board is

directed to cooperate with the local public school officials

“to give effect * * * in the process of the transition from

segregation to desegregation” and states that it “trusts that

all citizens will exercise patience and tolerance to the end

that the law of the land may be implemented in the elim

ination of racial discrimination in the public schools of the

State.” (Emphasis supplied.)2

3. Actions by the Board of Education of Harford County

Subsequent to June 22, 1955.

Eight days after the Opinion of the Attorney General of

Maryland of June 20, 1955 and thirty days after the filing

of the Second Opinion of the Supreme Court of the United

States in the Brown case, the Board of Education of Harford

County (hereinafter referred to as the “County Board” )

on June 30,1955 selected a Citizens Consultant Committee

2 Judicial notice may be taken of the fact that there have been two

meetings of the General Assembly of Maryland since the Opinion of

the Attorney General was promulgated, the “ Short” Session of 1956

and the “ Regular” Session of 1957 and that there were no Acts passed

which attempted in any way to overrule or circumvent the Opinion

of the Attorney General that any Maryland Constitutional or Statutory

provisions requiring segregation in the public schools were nullities.

9

of 36 members from all sections of Harford County, 5 of

whom were colored citizens, to consider the problem of

desegregation of the Harford County public schools and to

make recommendations to the County Board.

On July 27, 1955 a group of colored parents petitioned

the County Board “to take immediate steps to reorganize

the public schools under your jurisdiction on a non-discrim

inating basis.”

The Citizens Consultant Committee held its first meeting

on August 15, 1955, divided into Sub-Committees to con

sider (1) facilities, (2) transportation and (3) social re

lationship. A member of the Staff of the County Board

served as a consultant to each sub-committee. These Sub

committees met at various times during the remaining

portion of 1955 and during January and February, 1956.

On February 27, 1956, the Citizens Consultant Committee

held a meeting at which all of the Sub-Committees pre

sented their final reports. None of the specific recommenda

tions in those reports was adopted by the full Committee

which unanimously adopted the following resolution.

“To recommend to the Board of Education for Har

ford County that any child regardless of race may make

individual application to the Board of Education to be

admitted to a school other than the one attended by

such child, and the admissions to be granted by the

Board of Education in accordance with such rules and

regulations as it may adopt and in accordance with the

available facilities in such schools; effective for the

school year beginning September, 1956.” (Emphasis

supplied.)

The Resolution of the Citizens Consultant Committee was

adopted by the County Board on March 7, 1956.

10

On March 9, 1956, Civil Action No. 8615, Moore, et al v.

Board of Education of Harford County, et al, which had

been filed on November 29, 1955, came on for hearing on

the Defendants’ Motion to Dismiss. In this suit it was al

leged that the County Board had “refused to desegregate

the schools within its jurisdiction and had not devised a

plan for such desegregation.” The Plaintiffs were children,

the four infant Original Plaintiffs in the case at bar with

17 other colored children through their parents and next

friends. In Civil Action No. 8615 the Plaintiffs prayed (1)

for a speedy hearing of their application for a preliminary

and for a permanent injunction; (2) for a preliminary and

permanent judgment that any orders, customs, practices

and usages pursuant to which the Plaintiffs are segregated

in their schooling because of race violate the Fourteenth

Amendment; and (3) that the Court enter a preliminary

injunction ordering the Defendants to promptly present a

plan of desegregation to the Court which will expeditiously

desegregate the Harford County schools and enjoin the De

fendants from requiring the Plaintiffs and all other Negroes

of public school age to attend or not to attend such public

schools because of race.

In the Defendants’ Motion to Dismiss the Complaint, the

failure of the Plaintiffs to exhaust their administrative

remedy by way of appeal to the State Board was alleged.

Counsel for the Defendants brought the Resolution of the

County Board of March 7, 1956 to the attention of Counsel

for the Plaintiffs and to the Court, and relying on the Reso

lution, the Plaintiffs dismissed Civil Action No. 8615.

On June 6, 1956 the County Board adopted a “Transfer

Policy”, (App. 8a-9a), which was duly advertised in the

local newspapers. This “Transfer Policy” provided that if

a child desired to attend a school other than the one in

11

which he was enrolled or registered, his parents must re

quest a transfer between June 13 and July 15, 1956, stating

the reason for the transfer and bearing the approval of the

principal of the school the applicant was then attending.

It provided that:

“While the Board has no intentions of compelling a

pupil to attend a specific school or of denying him the

privilege of transferring to another school the Board

reserves the right during the period of transition to de

lay or deny the admission of a pupil to any school, if

it deems such action wise and necessary for any good

and sufficient reason.”

The County Board stated in the “Transfer Policy” that it

would finally consider the application for transfer at its

meeting of August 1, 1956. Children whose applications

were approved, were required to enroll on the regular sum

mer registration date, August 24, 1956. Sixty colored stu

dents filed applications for transfer.

On August 1, 1956, the County Board adopted a “Deseg-

regation Policy” . This Resolution recited the appointment

of the Citizens Consultant Committee, the recommendation

of that Committee, the Resolution adopted by the County

Board on March 7, 1956 and the “Transfer Policy” of June

6, 1956. It then provided:

“The Supreme Court decision, which required de

segregation of public schools, provided for an orderly,

gradual transition based on the solution of varied local

school problems. The resolution of the Harford County

Citizens Consultant Committee is in accord with this

principle. The report of this committee leaves the

establishment of policies based on the assessing of local

conditions of housing, transportation, personnel, educa

tional standards, and social relationships to the discre

tion of the Board of Education.

12

“The first concern of the Board of Education must

always be that of providing the best possible school

system for all of the children of Harford County.

Several studies made in areas where complete desegre

gation has been practiced have indicated a lowering of

school standards that is detrimental to all children.

Experience in other areas has also shown that bitter

local opposition to desegregation in a school system not

only prevents an orderly transition, but also adversely

affects the whole educational program.

“With these factors in mind, the Harford County

Board of Education has adopted a policy for a gradual,

but orderly, program for desegregation of the schools

of Harford County. The Board has approved applica

tions for the transfer of Negro pupils from colored to

white schools in the first three grades in the Edgewood

Elementary School and the Halls Cross Roads Elemen

tary School. Children living in these areas are already

living in integrated housing, and the adjustments will

not be so great as in the rural areas of the county where

such relationships do not exist. With the exception of

two small schools, these are the only elementary build

ings in which space is available for additional pupils

at the present time.

“Social problems posed by the desegregation of

schools must be given careful consideration. These

can be solved with the least emotionalism when

younger children are involved. The future rate of ex

pansion of this program depends upon the success of

these initial steps.”

In accordance with the Desegregation Policy, 15 of the

60 applications were granted, and 45 applications, including

those of the 4 original infant Plaintiffs in the case at bar,

were refused. On August 7, 1956, the County Superintend

ent of Schools, Charles W. Willis, notified the respective

parents of the infant Plaintiffs in writing of the adoption

of the Desegregation Policy (enclosing a copy) and advised

them that “under the provisions of this policy your child

13

will not be allowed to transfer from his present school”, and

that the County Board had refused “your request for a

transfer” (App. 11a).

No appeal to the State Board from the action by the

County Superintendent was taken by the infant Plaintiffs

or their parents or by any of the other applicants whose

applications were refused.

On August 28, 1956, the complaint in the present suit,

Civil Action No. 9105 (R. 3-8), was filed by the Original

Plaintiffs, the infants Stephen Moore, Jr., Dennis Spriggs,

Roslyn Slade and Patricia Garland, on behalf of them

selves and all Negroes similarly situated, against the County

Board and the County Superintendent of Schools. Moore

sought transfer from Central Consolidated Elementary

School in Hickory to the elementary school in Bel Air,

where he resides; Spriggs from the Hickory School to the

Junior High School in Edgewood, where he resides; Slade

and Garland from Havre de Grace Consolidated School to

Aberdeen High School, in the 9th and 11th grades respec

tively. They prayed for (1) advancement of the cause on

the docket and (2) that the Court enter preliminary and

permanent judgments that any “orders, customs, practices

and usages pursuant to which said plaintiffs are each of

them, their lessees, agents and successors in office from

denying to plaintiffs and other Negro residents of Harford

County of the State of Maryland admission to any Public

School operated and maintained by the Board of Education

of Harford County, on account of race and color” (R. 8).

On September 18, 1956, the Defendants filed a Motion to

Dismiss (R. 9-12) substantially similar to the one filed in

Civil Action No. 8615, including the point that the Plaintiffs

had not exhausted their administrative remedy by appeal

to the State Board (R. 9). A pre-trial conference was held

14

by Judge Thomsen on October 2, 1956, and on October 5,

1956, Judge Thomsen overruled the Motion to Dismiss with

out prejudice to the Defendants to raise the same points in

their Answer (R. 13). The Defendants answered on Octo

ber 14, 1957, setting up the defenses in the Motion to Dis

miss as well as answering the allegations of the Complaint

(R. 14-24).

4. Hearing of November 14,1956.

The case was set for hearing on November 14, 1956. At

this hearing both the Plaintiffs and Defendants offered oral

testimony and introduced documentary exhibits.

The Sub-Committee Reports of the Sub-Committees on

(1) Facilities (App. 40a-44a; R. 317-322), (2) Transporta

tion (R. 337-338) and (3) Social and Recreational Aspects

(R. 339-340) were offered in evidence by the Plaintiffs.

These were objected to by Counsel for the Defendants on

the grounds that they were preliminary reports of Sub-

Committees, which were not adopted by the full Com

mittee and were merged in the Report of the full Com

mittee (Appellees’ App. 1-2). They were marked for iden

tification as Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 1-A, B, C (and D ) and were

admitted in evidence by the District Court only for the

limited purpose of showing “the field of study covered by

the Sub-Committees of the General Committee” (Appellees’

App. 4; 8).3

3 Although none of the Reports of the Sub-Committees has any legal

or other effect, it is interesting to note that the recommendations of

each Sub-Committee were quite different and none was adopted either

by the full Committee or by the County Board. The Sub-Committee

on Facilities “ was of the opinion that provision can be made to accom

modate such colored students as apply for admission to Harford

County public schools for the year 1956-1957” (App. 44a: R. 322)

without specifying the basis for such admission; the Sub-Committee

on transportation recommended “ that integration be a planned, gradual

procedure — one grade a year is suggested” (R. 338); the Sub-

15

Mr. Willis testified that both he and the County Board

were familiar with the Opinion of the Attorney General of

Maryland of June 20, 1955, and the Resolution of the State

Board dated June 22, 1955; they understood that their

effect on the laws of Maryland requiring or permitting

segregation in the Public School System of Maryland was

to make those laws “null and void” (Appellees’ App. 10).

He further testified that neither he nor the County Board

had any intention not to comply with the Resolution of the

State Board of June 22, 1955 (Appellees’ App. 10) and then

described the selection and appointment of the Citizens

Consultant Committee. Of the 36 members, 5 members

were Negroes — “presidents of Parent-Teachers Associa

tion, head of a national association for the protection of

Colored People, people from various sections of the County,

a Doctor from Havre de Grace * * *” (Appellees’ App. 11-

12). Mr. Willis then described the advertising for applica

tions for transfers and the adoption by the County Board

of the “Desegregation Policy” of August 1, 1956. Mr. Willis

stated that he believed that he and the County Board had

“made a reasonable start in good faith to carry forward

the integration of the public schools in Harford County” ;

that the process would continue “based upon the experience

obtained by the first year of operation under the plan” ; and,

that he and the County Board “have made a reasonable

start toward the complete integration of the schools of

Harford County in a reasonable time with deliberate speed

and that this will be accomplished in a gradual and orderly

manner” (Appellees’ App. 15-16). He also testified that

Committee on Social and Recreational Aspects recommended that

“ ability be considered in the grouping of all children, but that no class,

for which children of both races are available, be of one race with the

exception of elective courses. That the absorption of the colored pupils

be in all schools and roughly on a 10 per cent basis, provided no hard

ship of long transportation be placed upon any pupils” (R. 339).

16

he was not “relying on any State law, statute, order, regu

lation, custom or usage which purports to require or permit

continued segregation of the races in the public schools of

Harford County” (Appellees’ App. 16).

Judge Thomsen pointed out that he “hadn’t heard Mr.

Willis’ good faith questioned” (Appellees’ App. 16) and

that “there is no question of inequality of facilities” (Ap

pellees’ App. 19).

Mr. Willis described the organization of the school sys

tem in Harford County — a six-three-three system —, that

is, six years of elementary school, three years junior high

school and three years of senior high school. The facilities,

transportation problems and other factors were described

by Mr. Willis (Appellees’ App. 16-21).

David G. Harry, President of the County Board, con

firmed the testimony of Mr. Willis as correct, his familiarity

and that of the County Board with the Opinion of the Attor

ney General of June 20, 1955, the Resolution of the State

Board of June 22, 1955, the effect of the Opinion and Resolu

tion in making the Maryland laws requiring or permitting

segregation in the public schools “null and void”, and the

intention of the County Board to comply with the Resolu

tion of the State Board of June 22, 1955 (Appellees’ App.

21-22). He understood that in promulgating the “Transfer

Policy” of June 6, 1956 and the Desegregation Policy” of

August 1, 1956, he was carrying out the Resolution of the

County Board adopted March 7, 1956 (Appellees’ App. 22).

He also stated that he believed that the County Board had

made a “reasonable start in good faith to carry forward

the integration policy in the Harford County public schools,

the plan adopted by the County Board had been “very suc

cessful thus far” , the County Board intended to continue

the integration of additional grades based on experience

17

obtained in the first year of operation under the Plan, and

that the County Board has “made a reasonable start to

ward completing the integration of the schools of Harford

County within a reasonable time and with deliberate speed”

and that “this will be accomplished in a gradual and orderly

manner” (Appellees’ App. 22-23).

Ernest Volkart, United States Commissioner, and Chair

man of the Citizens Consultant Committee, testified in re

gard to the meeting of that Committee on February 27,

1956 (Appellees’ App. 26). He prepared the Resolution of

the full Committee of February 27, 1956, and stated that

his understanding of the practical effect of that Resolution

as the Committee and he understood it:

“ * * * was that the change which had taken place

under the Supreme Court ruling would have to be in a

measure gradual and that the Citizens Committee could

not prescribe any specific pattern, and that the resolu

tion speaks for itself in that the School Board must

make rules and regulations to integrate the schools

gradually and consistent with the best interests of our

citizens of Harford County” (Appellees’ App. 27).

He stated that “the recommendations of the various Sub

committees” were not “adopted by the full Committee” .

He thought that the actions of the County Board in adopt

ing the Transfer Policy of June 6, 1956, and the Desegrega

tion Policy of August 1, 1956, were “consistent with and in

furtherance of the resolution of the Citizens Committee

of February 27th, 1956” (Appellees’ App. 27).

As a result of that hearing, Judge Thomsen filed an Opin

ion on November 23, 1956 (App. 4a-15a), 146 F. Supp. 91, in

which he concluded (1) that the appointment of the Citi

zens Consultant Committee in the Summer of 1955, its study

and recommendation and the Resolution of March 7, 1956,

18

were “a prompt and reasonable start” toward compliance

with the ruling in the Brown case and (2) that the Plaintiffs

must exhaust their administrative remedy by appeal to the

State Board on or before December 15, 1956 (App. 15a).

He intimated no opinion as to the sufficiency or propriety of

the Desegregation Policy of August 1, 1956. Further pro

ceedings in the case at bar were stayed pending the Appeal

to the State Board.

5. Proceedings Before the Maryland State Board

of Education.

On December 6,1956, two of the Original Infant Plaintiffs

in the case at bar, Stephen Moore, Jr., and Dennis Spriggs,

and 10 additional children, Robert McDaniel, Earlene Scott,

Mona Leisia Scott, Bernard Blackstone, Larry Wilson

Blackstone, Ellen Elizabeth Blackstone, Maurice L. Horsey,

III, David Roland Bell, James J. Bell, Jr., and Aurelia H.

Boose, took an appeal to the State Board from the action

of the County Superintendent of August 7, 1956 (R. 373).

The Appeal of Aurelia H. Boose was withdrawn as she was

not in Maryland at the time of the hearing before the State

Board (Appellees’ App. 61).4

At the hearing before the State Board on February 27,

1957, both parties were represented by Counsel and elab

orate oral testimony and documentary evidence were

offered (R. 399-534). Alexander Harvey, Assistant Attor

4 Of the remaining 9 additional children, 8 were permitted to inter

vene in the case at bar (R . 51) over the objection of the Defendants

(R . 48-50). These Intervenors were: Earlene Scott, Mona Leisia

Scott, Robert McDaniel, David Roland Bell, Bernard Samuel Black

stone, Ellen Elizabeth Blackstone, Larry Wilson Blackstone and

Maurice L. Horsey, III. The present Appellants are 6 of the Inter

venors, i.e., Earlene Scott, Mona Leisia Scott, Bernard Blackstone,

Larry Blackstone, Ellen Elizabeth Blackstone and Maurice L. Horsey,

III, and 1 of the Original Plaintiffs, Roslyn Slade, who did not, how

ever, appeal to the State Board.

19

ney General of Maryland was also present to advise the

State Board (Appellees’ App. 60). The President of the

State Board is Wendell D. Allen, a prominent Baltimore

Attorney. William A. Gunter, a distinguished Attorney

from Western Maryland is a member of the State Board, as

is also Dr. Dwight O. W. Holmes, an eminent colored edu

cator, and President Emeritus of Morgan College (Appel

lees’ App. 59). All of the members of the State Board par

ticipated actively in the hearing.

The Appellants before the State Board offered the testi

mony of parents of some of the infants involved — Mr.

Moore (R. 400-411), Mr. Spriggs (R. 420-427), and the

Reverend Mr. Scott (R. 430-440). Certain documents were

introduced into evidence (R. 412-414).

Mr. Willis, on behalf of the County Board, reviewed his

educational qualifications (Appellees’ App. 61); the prior

history of what the County Board did in regard to the Opin

ion of the Attorney General of June 20,1955, by the appoint

ment of the Citizens Consultant Committee, the Resolu

tion of the County Board of March 7, 1956, the Transfer

Policy of June 14, 1956 and applications for transfer filed

thereunder, and the Desegregation Policy of August 1, 1956

(Appellees’ App. 62-63).

Mr. Willis then outlined the considerations which the

County Board considered in formulating its Desegregation

Policy of August 1, 1956. These were in brief: (1) the

likelihood of successful application of the desegregation

policy in Edgewood and Aberdeen, where there were Army

bases, and a “desegregated” atmosphere; (2) the wisdom

of beginning the desegregation program with the younger

children in the lower grades (a) where social problems

were not so great and (b) both white and colored pupils

would have the same educational program and background

20

and could progress together from grade to grade; and (c)

the available school facilities. In regard to this latter con

sideration, Mr. Willis pointed out that there had been a

100% increase in the Harford County school population in

the past 10 years (from approximately 7,000 to 14,000) dur

ing which period the County Board has spent approxi

mately $14,000,000 for school construction. The County

Board has a $3,000,000 building program projected, one-half

for 1957 and the other half for 1958. The only elementary

schools which had available facilities for the desegregation

program on August 1, 1956, were Edgewood and Aberdeen,

and Perryman, where there were no applications, and Dar

lington, in a very rural area, where there was only one

application (Appellees’ App. 63-66).

The County Board’s “Extension of the Desegregation

Policy for 1957-1958” , adopted February 6, 1957, was

brought to the State Board’s attention. This Resolution, in

effect, extended desegregation to all of the elementary

schools and all classes in those schools for the school year

1957-1958 which were not more than 10% overcrowded

as of February 1, 1957. Mr. Willis explained that schools

which are 10% overcrowded as of February 1, 1957, would

be from 16% to 20% overcrowded in the fall of 1957, the

beginning of the 1957-1958 school year. The normal class

size was based on an average of 30 pupils for each class

room. This is in accordance with the State and National

Standard (App. 33a). The building program would elimi

nate all of the overcrowding in the elementary schools by

September, 1958, if there were no unforeseen developments

in the building program (Appellees’ App. 68). Mr. Willis

pointed out that the new Junior College at Bel Air would

be opened in September, 1957, on a desegregated basis

(Appellees’ App. 68).

21

Mr. Willis stated that the County Board had moved for

ward in the desegregation of the public schools of Harford

County “on a reasonable basis” and “with all practicable

and deliberate speed” (Appellees’ App. 68).

Mr. Harry, the President of the County Board, confirmed

the testimony of Mr. Willis (Appellees’ App. 69).

On March 4, 1957, the State Board by a unanimous de

cision dismissed the appeals, finding that (1) the County

Board had acted within the policy established by the State

Board, (2) the County Superintendent had acted in good

faith within the authority set forth in the Desegregation

Policy adopted on August 1, 1956, by the County Board;

(3) that the Desegregation Policy of August 1, 1956, was

adopted in a bona fide attempt to make a reasonable start

toward desegregation of the Harford County public schools;

(4) that the initial efforts had been carried out without any

untoward incidents (Appellees’ App. 70-76).

The State Board also took cognizance of the Resolution

of the County Board of February 6, 1957, entitled “Exten

sion of the Desegregation Policy for 1957-1958” , (which had

been passed by the County Board pending the appeal to

the State Board and which will be considered below) and

of the testimony that the proposed Harford County Junior

College to be opened in Bel Air in the fall of 1957, would be

opened on a desegregated basis, as well as the testimony

that the present program of new buildings and additions

will make further desegregation possible (Appellees’ App.

75-76).

6. Action of the County Board on February 6, 1957.

As above pointed out, the County Board, on February 6,

1957, passed a Resolution for “Extension of the Desegrega

tion Policy for 1957-1958”. In effect, it extended desegre

22

gation to all grades of all the elementary public schools in

Harford County where space was available. It further

provided:

“Space will be considered available in schools that

were not more than 10% overcrowded as of February

1, 1957. All capacities are based on the state and na

tional standard of thirty pupils per classroom.

“Under the above provision, applications will be ac

cepted for transfer to all elementary schools except

Old Post Road, Forest Hill, Bel Air, Highland, Jarrets-

ville, the sixth grade at the Edgewood High School,

and Dublin. Such applications must be made during

the month of May on a regular application form fur

nished by the Board of Education, and must be ap

proved by both the child’s classroom teacher and the

principal of the school the child is now attending.

“AJ1 applications will be reviewed at the regular June

meeting of the Board of Education and pupils and their

parents will be informed of the action taken on their

applications prior to the close of school in June, 1957.”

7. Hearing in the District Court on

April 18, 1957.

After the decision of the State Board on March 4, 1957,

Judge Thomsen held a second pre-trial conference on

March 29, 1957. A hearing was held before Judge Thomsen

on April 18, 1957. Again oral testimony was taken and

documentary evidence offered, including the proceedings

before the State Board.

Mr. Willis testified fully in regard to the School System

generally in Harford County and in particular in regard

to the individual schools — the ones which are overcrowded

and to what extent, as well as other relevant details (Ap

pellees’ App. 28-37).

23

8. Hearing in the District Court on June 11,1957.

Judge Thomsen had indicated that the Plan of the County

Board was generally acceptable for elementary schools,

but that he was doubtful about postponing desegregation

completely in the High Schools until normally accomplished

by the Plan’s operation in the elementary schools with pro

motions to the High Schools in regular course. Judge

Thomsen suggested that the parties try to agree on some

plan for the High Schools during the transition period. This

was attempted but Counsel for the Plaintiffs would not

agree on any limitation of any number of colored pupils

in the High Schools but insisted that “ the Plaintiffs and the

class they represent should be admitted to the High Schools

without any racial restrictions whatsoever” (Appellees’

App. 78).

The County Board modified its Desegregation Plan for

the High Schools of Harford County during the interim

period by providing for applications for transfers to High

Schools near the applicant’s home to be approved or dis

approved on the “basis of probability of success and adjust

ment of each individual pupil, and the committee will

utilize the best professional measures of both achievement

and adjustment that can be obtained in each individual

situation. This will include, but not be limited to, the re

sults of both standardized intelligence and achievement

tests, with due consideration being given to grade level

achievements, both with respect to ability and with respect

to the grade into which transfer is being requested” (Ap

pellees’ App. 79).

Mr. Willis explained the practical operation of the Modi

fication (Appellees’ App. 42-49).

24

9. Opinion of June 20, 1957 and Judgment of

July 3, 1957.

Judge Thomsen filed his Second and final Opinion on

June 20,1957 (App. 16a-25a). Based on that Opinion, Coun

sel for the Plaintiffs prepared a proposed form of Judgment

(to the form of which Counsel for the Defendants inter

posed no objection), and this Judgment was signed and

filed on July 3, 1957 (App. la-3a).

The Appellants noted their Appeal from the Judgment

of July 3, 1957 on July 25, 1957 (R. 587).

ARGUMENT

The Findings by the District Court (Thomsen, C.J.) that

the County Board had Made a Prompt and Reasonable Start

Toward the Desegregation of the Public Schools of Harford

County and that Additional Time was Necessary to Effec

tuate Such Desegregation as Set Forth in the Judgment of

July 3, 1957, Were not Clearly Erroneous.

There seems to be no contention by the Appellants that

the District Court did not recognize and apply the appli

cable law. They contend that the District Court erred in

concluding that the Appellees met the burden of showing

the necessity for limited delay incident to the Desegrega

tion Plan set forth in the Judgment of July 3, 1957. This

Appeal, therefore, essentially presents an alleged error in

volving a finding of fact. It is well established by Rule

52(a) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure and by the

decisions of the Supreme Court of the United States and

of this Court5 that the Appellants must establish that the

5 U.S. v. National Association of Real Estate Boards, 339 U.S. 485,

70 S. Ct. 711, 94 L. Ed. 1007 (1950 — Douglas, J.) and see other

Supreme Court cases cited by Mr. Justice Douglas at page 495 of 339

U.S. 485.

New York Life Ins. Co. v. Tobin, 177 F. 2d 176 (1949 — C.A. 4th,

Per Curiam) and cases cited on page 177 of the Opinion.

25

findings of the District Court were “clearly erroneous” in

order to obtain a reversal.

It would perhaps have been sufficient for the Appellees

merely to refer to the careful and comprehensive Opinions

of the District Court — the Opinion of November 23, 1956

and of June 20, 1957 (App. 4a-25a) — and the Judgment

of July 3, 1957 itself, to show that the findings of the Dis

trict Court were not clearly erroneous, but were clearly

in accord with the great weight of the evidence. Indeed,

these Opinions and the facts show that the District Court

went beyond the requirements of the applicable law with

a view to expediting the progress of desegregation in the

public schools of Harford County and the protection of the

constitutional rights, not only of the colored pupils as a

class, but also of individual plaintiffs involved in the liti

gation.0 The public importance of the case, not only to 6

6 The Appellants properly point out in their Brief (page 2) that

the “ estoppel” phase of the suit is not at issue in the case at bar. This

is because the Appellees did not file a Cross-Appeal. The determina

tion of the County Board not to file a Cross-Appeal to raise this issue

was deliberate. The County Board does not wish to be thought to

acquiesce in the District Court’s determination that its Desegregation

Policy of August 1, 1956, was not in accord with and consistent with

its Resolution of March 7, 1956. On the contrary, it was, and is, the

position of the County Board that the intention and understanding of

the draftsman of the Resolution, Mr. Volkart, was to leave the

granting of any applications for transfer in the hands of the County

Board without specific recommendations, but in accordance with the

rules and regulations of the County Board and with available facilities.

This was the understanding of Counsel for the County Board, the

President of the County Board, and County Superintendent. This

understanding is in accord with the language of the Resolution of

March 7, 1956, itself. Then too, if the Plaintiffs in Civil No. 8615, had

not voluntarily dismissed the Complaint, it would have been dis

missed — or at least postponed substantially — because the Plaintiffs

had not exhausted their administrative remedy by appeal to the State

Board. There was, therefore, no real prejudice to the Plaintiffs by the

voluntary dismissal of the Complaint in Civil No. 8615. It would not

have been “ inequitable” to have required the Infant Plaintiffs Moore

and Spriggs to have complied with the Plan applicable to others in

26

Harford County, but to the people of the State of Mary

land generally, seemed to require a full consideration of

the background, both Statutory and administrative, of the

case and all of the applicable facts in the particular case.

The decision of this Court in this case is of more than

passing importance. It is of particular importance to the

entire problem of desegregation throughout the United

States. Maryland is a border State, which from the begin

ning of its State-wide educational system in 1865 has had

separation of the races in the public school system. This

continued until 1955, a period of 90 years. The system of

“separate but equal” separate school facilities was insti

tuted in 1872 and continued until 1955, a period of 83 years.

There has been no defiance of the decision in the Brown

case in Maryland. On the contrary, both the political and

administrative officials of the State have officially acted to

require compliance with that decision with more than

“deliberate speed”. In the case at bar, it is conceded that

the County Board has acted in good faith to desegregate

the public schools in Harford County. The State Board —

the highest administrative educational authority in the

State — has approved the County Board’s action after a

full and careful hearing. There has been no conflict be

their situation, particularly as there is no question that the school

facilities which they enjoy are equal — if not superior — to those

which are provided in Paragraph 6 of the Judgment of July 3, 1957.

The District Court indicated that if an appeal or cross-appeal were

taken by the County Board he would not supersede the operation of

the Judgment of July 3, 1957, pending appeal. Under these circum

stances, the County Board decided that it would be inequitable to

displace the infant Plaintiff Moore from the sixth grade at the Bel Air

School and the infant Plaintiff Spriggs from the eighth grade at Edge-

wood High School in the course of a school year even if the County

Board were successful in a cross-appeal, particularly in view of the

nature of the general Plan adopted by the County Board and incor

porated in the Judgment of July 3, 1957. It was for this reason alone

that a cross-appeal was not taken.

27

tween the Federal Courts and State officials. There has

been no untoward incidents arising in Harford County as

a result of the Plan. An affirmance of Judge Thomsen’s

decision by this Court may well point the way to a rational,

equitable and practical solution to the difficult problems

posed in many other localities by the Brown decision.

Judge Thomsen’s decision is also of more than judicial

importance in view of the unusual, if not unique, circum

stance that before his appointment as District Judge, he

was President of the Board of School Commissioners of

Baltimore City — or as he modestly puts it — “I have had

some experience with School Boards” (Appellees’ App. 10).

His decision has the added value of his administrative ex

perience as the head of the local governing body of the

public school system of one of the largest cities in the

United States.

The law governing the case appears in the Second Opinion

of the Supreme Court of the United States in Brown v.

Board of Education of Topeka, 349 U.S. 294, 75 S. Ct. 753,

99 L. Ed. 1083 (May 31, 1955, Warren, C.J.) and in the de

cisions of this Court in Carson v. Board of Education of

McDowell County, 227 F. 2d 789 (1955, Per Curiam); Hood

v. Board of Trustees of Sumter County School District No.

2, 232 F. 2d 626 (1956, Per Curiam); Carson v. Warlick, 238

F. 2d 724 (1956, Parker, C.J.) and of the Three-Judge Court,

composed of Chief Judge Parker, Circuit Judge Dobie and

District Judge Timmerman, in Briggs v. Elliott, 132 F. Supp.

776 (1955, Per Curiam).

In their Brief, page 9, the Appellants seek to narrow

substantially the effect of the Second Opinion in the Brown

case. All of the language of Chief Justice Warren’s Opinion

is important. He stated for the Supreme Court that:

28

“Full implementation of these constitutional prin

ciples may require solution of varied local school prob

lems. School authorities have the primary responsi

bility for elucidating, assessing, and solving these prob

lems; courts will have to consider whether the action

of school authorities constitutes good faith implementa

tion of the governing constitutional principles. Because

of their proximity to local conditions and the possible

need for further hearings, the courts which originally

heard these cases can best perform this judicial ap

praisal. Accordingly, we believe it appropriate to re

mand the cases to those courts.” (Emphasis supplied.)

349 U.S. at page 299.

“In fashioning and effectuating the decrees, the

courts will be guided by equitable principles. Tradi

tionally, equity has been characterized by a practical

flexibility in shaping its remedies and by a facility for

adjusting and reconciling public and private needs.

These cases call for the exercise of these traditional

attributes of equity power. At stake is the personal

interest of the plaintiffs in admission to public schools

as soon as practicable on a nondiscriminatory basis. To

effectuate this interest may call for elimination of a

variety of obstacles in making the transition to school

systems operated in accordance with the constitutional

principles set forth in our May 17,1954, decision. Courts

of equity may properly take into account the public

interest in the elimination of such obstacles in a syste

matic and effective manner. But it should go without

saying that the vitality of these constitutional prin

ciples cannot be allowed to yield simply because of dis

agreement with them.” (Emphasis supplied.) 349 U.S.

at page 300.

“While giving weight to these public and private

considerations, the courts will require that the defen

dants make a prompt and reasonable start toward full

compliance with our May 17, 1954, ruling. Once such

a start has been made, the courts may find that addi

tional time is necessary to carry out the ruling in an

29

effective manner. The burden rests upon the defen

dants to establish that such time is necessary in the

public interest and is consistent with good faith com

pliance at the earliest practicable date. To that end,

the courts may consider problems related to adminis

tration, arising from the physical condition of the school

plant, the school transportation system, personnel, re

vision of school districts and attendance areas into

compact units to achieve a system of determining ad

mission to the public schools on a nonracial basis, and

revision of local laws and regulations which may be

necessary in solving the foregoing problems. They will

also consider the adequacy of any plans the defendants

may propose to meet these problems and to effectuate

a transition to a racially nondiscriminatory school sys

tem. During this period of transition, the courts will

retain jurisdiction of these cases.” (Emphasis supplied.)

349 U.S. at page 300.

This Court, in the Opinions mentioned, has established

that:

1. That if a proper administrative remedy is provided

by the State Law, the Plaintiffs in this type of case must

exhaust that remedy and “the Courts of the United States

will not grant injunctive relief until administrative reme

dies have been exhausted.” 227 F. 2d at 790. (To the same

effect 238 F. 2d at 727; 232 F. 2d at 626.)

2. “The federal courts manifestly cannot operate the

schools.” (227 F. 2d at 790) and the Brown decision did not

provide “that the federal courts are to take over or regu

late the public schools of the States” (132 F. Supp. at 777).

3. Interference by injunction with the schools of a state

is as grave a matter as interfering with its fiscal operations

and should not be resorted to ‘where the asserted federal

right may be preserved without it’ ” (227 F. 2d at 791).

4. Nothing in the Constitution of the United States or in

the decision in the Brown case “ takes away from the people

30

freedom to choose the schools they attend. The Constitu

tion, in other words, does not require integration. It merely

forbids discrimination. It does not forbid such segregation

as occurs as the result of voluntary action” (132 F. Supp.

at 777).

In the Second Opinion of the Supreme Court, it is pointed

out, in effect, that all matters and problems which affect

the school system as a system and which result or may re

sult from the change-over to a desegregated system, may

be considered and evaluated by the local school authorities

in formulating plans and in determining the time of com

pletion so long as the local board (a) acts in good faith and

(b) there is no attempt to resist the application of the Con

stitutional principles involved (1) entirely or (2) for an

unreasonable time. The Supreme Court clearly indicates

that the judgment of the local school authorities is to be

given great weight.

The West Virginia District Court cases on specific plans

(cited on page 10 of the Appellants’ Brief) are not very

helpful as the background and particular facts in each case

are quite different. Essentially each case stands on its own

facts so far as a specifis plan is concerned. Three of the

cases cited by the Appellants arose in jurisdictions in which

the State and Local authorities were actively resisting any

desegregation of the public schools at any time, had made

no start, reasonable or otherwise, and in which no effort

had been made to meet the burden upon the local author

ities to establish the need for additional time to complete

the desegregation program.7 It is well settled, however, that

7 School Board o f the City o f Charlottesville, Va. v. Alim, 240 F.

2d 59 (1956, CA-4 — Parker, C.J.) c.d. 353 U.S. 910.

School Board o f the City o f Newport News, Va, v. Atkins, 246 F.

2d 325 (1957, CA-4 — Per Curiam).

Jackson v. Rawdon, 235 F. 2d 93 (1956, CA-5 — Hutcheson, C.J.).

31

a gradual, grade-by-grade, method of implementing a bona

fide desegregation plan is in accordance with the Supreme

Court’s Second Opinion in the Brown case. Aaron v. Cooper,

243 F. 2d 361 (CA-8,1957, Vogel, Ct. J.).

What then was the factual situation in regard to the

public school system in Harford County?

Harford County is predominantly a rural County. There

are two large government reservations in the southern end

of the County — Aberdeen Proving Ground at Aberdeen

and the Army Chemical Center at Edgewood. On the gov

ernment reservations, the housing developments are op

erated on a non-segregated basis.

In accordance with the Maryland law and policy prior

to 1955, the Harford County public school system provided

“separate but equal” school facilities for white and colored

students as permitted by the Opinion of the Supreme Court

of the United States in Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537,

16 S. Ct. 1138, 41 L. Ed. 256 (1896, Brown, J.). At the time

of this suit, the County Board provided two large “consoli

dated” schools for approximately 1400 colored students,

comprising elementary, junior high and senior high school

classes at Hickory and at Havre de Grace. This was in ac

cord with the County Board’s 6-3-3 system, that is, 6 years

of elementary school, 3 years of junior high school and 3

years of senior high school. The same system was provided

for approximately 12,600 white students. There were 18

white elementary schools8 and 5 high schools, comprising

junior and senior high schools, at Bel Air, Bush’s Corner

(North Harford), Edgewood, Aberdeen and Havre de

Grace.

8 Emmorton, Edgewood, Aberdeen, Halls Cross Roads, Perryman,

Churchville, Youth’s Benefit, State Ridge, Darlington, Havre de

Grace, Old Post Road, Bel Air, Highland, Forest Hill, Jarrettsville,

Dublin, 6th grade at Aberdeen High School and sixth grade at Edge-

wood High School.

32

It is conceded that the school facilities for the colored

students were equal if not superior to the facilities for the

white students. Cf. Willis v. Walker, 136 F. Supp. 177 (1955,

W.D. Ky., Swinford, D.J.) at page 179.

The students, both white and colored, were transported

free of charge to their schools unless they lived within walk

ing distance of the respective schools. White students were

required to attend the nearest white school and colored

students the nearest colored school.

There were white teachers in the white schools and col

ored teachers in the colored schools.

During the past 10 years, the school population has in

creased 100% (from approximately 7,000 to 14,000) and the

County Board has spent during that period approximately

$14,000,000.00 for school construction. To relieve over

crowding and care for additional students, the County

Board has a $3,000,000.00 building program, one-half for

1957 and the other half for 1958.

i

As pointed out in the Supplementary Statement of the

Facts, the Attorney General of Maryland and the State

Board moved with haste (rather than “deliberate speed” )

to announce the change in the long established Maryland

policy in regard to separation of the races in the public

schools. The County Board moved with great expedition

to select the Citizens Consultant Committee, that is, on

June 30, 1955, just 1 month after the filing of the Second

Opinion in the Brown case. Although the colored students

only amount to approximately 10% of the entire school

population, 5 of the 36 members of the Citizens Consultant

Committee, approximately 14% of the entire membership,

were representative Negroes holding important positions

or having a professional status. This Committee met

33

promptly on August 15, 1955 and subdivided into Sub-Com

mittees which studied the problems involved. The Sub

committees presented their final reports at a meeting of

the full Committee on February 27, 1956; none of the recom

mendations in the reports of the Sub-Committees was

adopted, but the Resolution of February 27, 1956 was unani

mously adopted by the full Committee, in effect leaving the

granting of applications to the judgment and discretion of

the County Board. The County Board, 8 days later, adopted

the same Resolution.

Judge Thomsen held that these actions constituted a

prompt and reasonable start toward compliance with the

Supreme Court’s ruling (App. 15a). They were most cer

tainly prompt. They were entirely reasonable. There is no

evidence to the contrary.

Well before the beginning of the school year for 1956

(September 1956), the County Board on June 6, 1956

adopted its Transfer Policy, advising of the right to file

applications for transfer to other schools, but specifically

indicating that it reserved the right “during the period of

transition to delay or deny the admission of a pupil to any

school if it deems such action wise and necessary for any

good and sufficient reason.”

The County Board adopted its “Desegregation Policy” on

August 1, 1956, outlining its proposals for the desegregation

of the schools in Harford County and its reasons for the

Plan. The County Board pointed out that the Supreme

Court’s decision “provided for an orderly, gradual transi

tion based on the solution of varied local school problems

and that the Resolution of the Citizens Consultant Com

mittee was in accord with that principle and left to the

discretion of the County Board the “establishment of poli

cies based on the assessing of local conditions of housing,

34

transportation, personnel, educational standards and social

relationships” . The County Board recited that studies in

areas where complete desegregation had been practiced

indicated a lowering of school standards that was detri

mental to all children and that experience in other areas

showed that bitter local opposition to desegregation in a

school system “not only prevents an orderly transition,

but also adversely affects the whole educational program.”

The County Board also pointed out that its first concern

must always be that of providing the best possible school

system for all of the children of Harford County.” (Em

phasis supplied.) The County Board concluded that it would

be best to start the desegregation policy with younger chil

dren where social problems posed by desegregation could

be solved with the least emotionalism. It selected the first

three grades in Edgewood Elementary School and Halls

Cross Roads Elementary School for the approval of appli

cations of Negro pupils from colored to white schools, point

ing out that there were already integrated housing devel

opments in these areas and that, with the exception of 2

small schools, (in one of which there was one application,

in the other, none) these were the only elementary build

ings in which space was available at the present time. The

County Board further stated that the future rate of ex

pansion of the program depended upon the success of the

initial steps.

The County Board, in accordance with the policy, ap

proved 15 of the 60 applications for transfer received, or

25%, and rejected 45 applications.

The program was successful and on February 6, 1957

(again well in advance of the 1957-1958 school year begin

ning September 1957), the County Board substantially ex

tended its desegregation policy by adopting a Resolution

35

entitled “Extension of Desegregation Policy for 1957-58”

(App. 19a). This, in effect, provided for the acceptance of

applications for transfer from pupils wishing to attend all

elementary schools in all classes in the area in which they

lived, if space were available. Space would be considered

available in schools not 10% overcrowded, as of February

1,1957. All capacities were based on the State and National

standard of 30 pupils per class room (App. 33a).

Mr. Willis, the County Superintendent, pointed out that

in the opinion of the County Board the adjustment of pupils

transferring from a colored to a white school could be ac

complished more smoothly and with better results for the

education of the pupil involved if the transfer were made

to a school which was not substantially overcrowded. Mr.

Willis further pointed out that a school which was 10%

overcrowded as of February 1, 1957 would be more over

crowded in September, 1957. In his judgment, the figures

would be 5% to 10% higher in September, 1957 (Appellees’

App. 37).

Mr. Willis summarized the factual situation in regard to

the 7 schools which were overcrowded more than 10% as of

February 1, 1957 (Appellees’ App. 35-37), as follows:

Name o f Elementary School

Sixth grade at Edgewood

Old Post Road...................

Forest Hill .......................

Bel A ir ...............................

Jarrettsville .....................

Highland ..........................

Dublin ..............................

Percentage o f Overcrowding

as o f February 1,1957

12 %9

24%

17%

14%

10%

16%

14%

9 Mr. Willis pointed out that this school would be considerably

overcrowded this year “ because we will hold every child that is there

and will bring in another sixth grade” (Appellees’ App. 36).

36

The overcrowding in three of these Schools, Old Post

Road, Bel Air and Highland, will be eliminated by Septem

ber, 1958 and the overcrowding in the remaining four

Schools, Forest Hill, Jarrettsville, Dublin and Sixth Grade

at Edgewood High School, will be eliminated by September

1959 by the Building Program if there are no unforeseen

circumstances arising in that Program. Summarizing the

situation in the elementary schools by percentages, 61% of

the elementary schools were desegregated in full as of Sep

tember, 1957; 17% will be fully desegregated as of Sep

tember, 1958; and, the remaining 22% will be fully deseg

regated as of September, 1959. Judge Thomsen held that

the reasons given for this policy in regard to overcrowding

were reasonable and that although this factor would not

justify unreasonable delay, under the circumstances of this

case, it justified that the one or two years delay in deseg