Memorandum for the United States as Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

July 15, 1972

23 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Milliken Hardbacks. Memorandum for the United States as Amicus Curiae, 1972. eb54b850-53e9-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/bea82ebd-a81b-4f12-b1ce-ec3d4ad203ee/memorandum-for-the-united-states-as-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 27, 2026.

Copied!

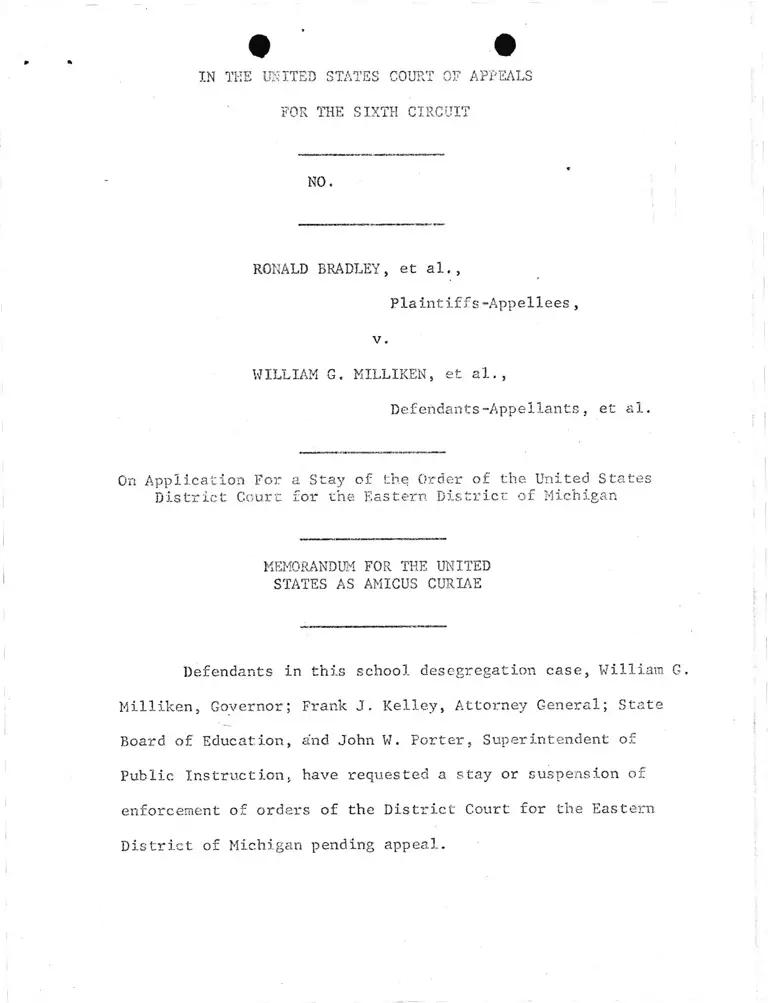

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

NO.

RONALD BRADLEY, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

v .

WILLIAM G. MILLIKEN, et al.,

Defendants-Appellants, et al.

On Application For a Stay of the Order of the United States

District Court for the Eastern District of Michigan

MEMORANDUM FOR THE UNITED

STATES AS AMICUS CURIAE

Defendants in this school desegregation case, William G.

Milliken, Governor; Frank J. Kelley, Attorney General; State

Board of Education, and John W. Porter, Superintendent of

Public Instruction, have requested a stay or suspension of

enforcement of orders of the District Court for the Eastern

District of Michigan pending appeal.

The United States, pursuant to Rule 29, Federal Rules

of Appellate Procedure, submits this memorandum as amicus

curiae. We urge this Court to rule favorably on the stay

application and to set an expedited schedule to hear and

decide the appeals before it.

The interest of the United States in the issues pre

sented by this case is derived in part from the responsibili

ties conferred upon it by Congress in Titles IV, VI and IX of

the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. §§2000c et seq., 2000d,

2000h-2, for enforcement of the law of public school desegrega

tion. Title IV of that Act authorizes the Attorney General

to "maintain appropriate legal proceedings” which "will

materially further the orderly achievement of desegregation

in public education...." The Government has appeared as

1/

amicus curiae in the district court in this case and has

filed a memorandum as amicus curiae with the Court of Appeals

for the Fourth Circuit in Bradley v. School Board of Richmond,

Nos. 72-1058, 1059, 1060 and 1150 (June 5, 1972) — a case

raising similar issues of law and policy. Moreover, we

think the present case, as it comes to this Court, may draw

1/ The United States was granted permission to appear as

amicus curiae in the district court on May 22, 1972.

- 2 - •

into question, the applicability and meaning of a United

2/

States statute which could affect our enforcement responsi

bilities. ■ /

! .

1. The Court below has announced its determination

to consolidate into one attendance area 53 separate school

districts and approximately 780,000 students and has directed

the preparation of detailed plans and the purchase of 295 school

buses looking toward the implementation of the plan this fall.

Moreover, some of the suburban districts as the District Court

3/ _

recognized -- have not even been held to have violated the

law or Constitution, but are included in the plan only because

of the race of the resident students, and were so included

with no opportunity to litigate the lawfulness and legal pro

priety of that inclusion. The unprecedented scope of the

orders below both in geography and law, persuade us to agree

with the applicants and the Congress that there should be an

opportunity for appellate review prior to requiring the

defendants to spend a great deal of money and take other

irreversible steps looking to implementation. -

2/ Education Amendments of 1972, P.L. 92-318, sec. 803

Teffective July 1, 1972). See infra at p. 12 for text of

this statute.

3/ Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law in Support of

Ruling on Desegregation Area and Development of Plan, Slip

op. at p. 1 (June 14, 1972).

In recommending that the district court order be

stayed we are cognizant of the Supreme Court's holding in

Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education, 396 U.S. 19,

*

‘ 20, that "the obligation of every school district is to

terminate dual systems at once and to operate now and here

after only unitary schools." However, this case differs

from Alexander and related cases, Carter v. West Feliciana

School Board, 396 U.S. 290 (1970); Kelley v. Metropolitan

County Board of Education of Nashville, 436 F .2d 856 (6th

Cir. 1970) in a major respect.

Those decisions relate to the elimination of dual

schools which had been maintained under state segregation

statutes. In contrast, the issues on appeal in the present

case are: (1) whether the Detroit School Board has in fact

discriminated against black students in its policies and

4/

actions, and (2) whether it is proper to include suburban

4/ Appeal by the Board of Education of the School District

of the City of Detroit, Notice of Appeal filed on June 22,

1972. The accompanying Brief in Support of Motion For

Accelerated Schedule.of Hearing indicates the appeal is

addressed to this question.

- 4 -

school systems m a desegregation plan without making specific

' ° 5/

findings of discrimination as to them.

The decisions in Alexander and related cases, su£ra,

arguably foreclosed, where they apply, the balancing of

interests by courts which has traditionally been required on

a motion for stay ~ The Alexander limitation on this tradi

tional equitable approach was established in cases which

involved the. appropriate remedy to be applied where there

was an uncontested dual school system. These decisions do

not preclude the granting of a stay under traditional princi

ples where the issue on appeal is not merely one of appropriate

5/ Appeal by Kerry Green, et al p^pubufschiols!6®!™!. Tune 29 1972; and appeal by Allen rark^uuiiu a ’ ,

Southfield Public Schools and Grosse Pointe lu rc S \ -.r. i „ Tlinf> on 1972. The question to be addressee uy filed on June 20, W /J q as stated. The Emergencythese appeals is anticipate defendants

Application for Stay filed on July 12,, with that

^ i ' ^ T T e d ' b . l n e n Park'public Schools, et al., Southfield motion filed by Alien rdav .. . c-hnn1«s indicatesPublic Schools and Grosse Pointetheir appeals are also addressed to this quest o .

6/ See the opinion of Mr. Justice Brennan in ’• S ^ 1-b/ bee cut f (J 969)- See also Hobson v.2H « i £ i N 0u l , 396 U.S. fold I9 5 8); Coppedce v. Franklin

Hansen, 44 F.R.D. J i -— ^ 7T 7n N c 1968).TvTTTT' ftnard of Education, 293 F. Supp. 356 (D. N.C. - ■ ;

- 5 -

remedy because the propriety of any remedy at all is in

question. Thus the choice facing this Court is not whether

to grant a further delay in the long-frustrated vindication

of constitutional rights. It is whether to stay the imposi

tion of a remedy for a violation whose existence is strongly

contested, and to stay a sweeping remedy which is being applied

7/

to districts which admittedly have violated no law.

In deciding whether to grant a stay here, we think

the Court would be more appropriately guided by considerations

suggested by Corpus Christi Independent School District v.

Cisneros, 404 U.S. 1211 (1971) than by those prevailing in

Alexander. In Cisneros, Justice Black reinstated the district

court’s order granting a stay because the case presented "a

very anomalous, new, and confusing situation" including ques

tions "not heretofore passed on by the full court, but which

should be." It would seem that this statement is applicable

to the present litigation.

Further* we note this Court's recent order in Northcross

v. Board of Education of Memphis, Misc. No. 1576 (July 5, 19/2)

(en banc) where a majority of the active jxidges of this Court

indicated approval of stays pending appeal in appropriate

7/ See Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law in Support of

Ruling on Desegregation Are and Development of Plan, slip op.

at p. 1 (June 14, 1972).

6

school desegregation cases and that it disagreed with con

tentions that the Supreme Court had mandated otherwise.

As in the present case, Bradley v. School Board of

Richmond, supra, raised issues not only of great importance

to the parties but with consequence for future education in

the entire nation. The defendants had been enjoined to create

a single school division composed of the city and two counties

and to take extensive actions to effectuate that result. Under

such circumstances, the court found a partial stay coupled

8 /

with an expedited review was justified.

8/ A copy of the stay order of February 3, 1972 is attached

to this memorandum. The Advisory Committee on Appellate

Rules state that Rule 2 of the Federal Rules of Appellate

Procedure authorizes "the courts of appeals to expedite the

determination of cases of pressing concern to the public or

to the litigants by prescribing a time schedule other than

that provided by the rules." This case is of pressing concern

both to the public and the litigants. See also Bradley v.

Milliken, 433 F .2d 897, 902 (1970) and Northcross v. Board_of

Education, 6th Cir., Misc.No. 1576 (June 2, 1972).

2, Courts have traditionally considered upon a

motion for a stay the probability of reversal on appeal,

*

whether the denial of a stay will result in irreparable

injury to the requesting party, whether the granting

of a stay will substantially harm the interests of the

other parties, and whether a stay is in the public in

terest. E.g., Long Vo Robinson, 432 F. 2d 97? (4th Cir.

1970); Belcher v. Birmingham Trust National Bank, 395

F. 2d 685 (5th Cir. 1968); Taylor v. Board of Education

of City School District of City of New Rochelle, 195

F. Supp. 231, 238 (D. N.Y.), aff’d., 294 F. 2d 36,

cert, den., 368 IJ.S. 940 (1961).

We think the record will show that counsel for the

state-level defendants and defendant-interveners presented

to the district court persuasive .reasons why a balancing

of the above considerations justifies a stay of pro-

8a_/

ceedings, and we need not repeat these reasons here.

/ See Emergency Motion of Defendants William G. Milliken,

Governor; Frank J. Kelley, Attorney General; State Board of

Education and John W. Porter, Superintendent of Public In

struction, for a stay or suspension of proceedings; support

ing affidavits of Lloyd Fales and Richard Barnhart; oral

argument of counsel on June 29, 1972, and July 10, 1972, and

motion and brief for a stay or suspension of proceedings filed

on July 12, 1972 by defendants-interveners Allen Park Public

Schools, et al., Grosse Pointe Public Schools and Southfield

Public Schools.

- 8 -

Because the district court invoked a remedy against

school districts without proof of any violation on their part,' t

■ • - *

the required probability of reversal on the merits clearly

U

exists. The Equal Protection Clause does not require a

particular racial balance in schools in a single school

district, even if formerly dual, Swann v. Board of Education,

402 U.S. 1, 22-25 (1971); a disparity in racial compositions

between two proposed school systems is not itself sufficient

to enjoin the creation of a separate district, see Wright v.

Council of City of bmporia, slip op., at 12 (June 22, 1972), nor

does extreme racial imbalance, without more, require the

reformation of neutrally established school district bound

ary lines. See Spencer v, Kugler, 326 F. Supp. 1235, 1243

(D. N.J. 1971), aff’d 404 U.S. 1027 (1972). Special credence

9 / In its Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law in

Support of Ruling on Desegregation Area and Development

of Plan, slip op. at p. 1 (June 14, 1972), the district

court stated: "It should, be noted that the court has

taken no proofs with respect to the establishment of the

boundaries of the 86 public school districts in the coun

ties of Wayne, Oakland and Macomb, nor on the issue of

whether, with the exclusion of the city of Detroit school

district, such school districts have committed acts of

de jure segregation.”

to the probability of reversal was provided by a re

versal on the merits by the. Fourth Circuit Court of

- Appeals in Bradley v. School Board of Richmond, supra,

the same district court case strongly relied upon by the

court below. In Bradley the court of appeals held:

Because we are unable to discern any

constitutional violation in the establish

ment and maintenance of these three school

districts, nor any unconstitutional conse

quence of such maintenance, we hold that it

was not within the district judge’s authority

to order the consolidation of these three

separate political subdivisions of the Common

wealth of Virginia.

Slip Op. at 29.

On the question of appealability of the currently

outstanding district court orders we think there can be

little doubt. In contrast to the prior appeal in this

case (dismissed on February 23, 1972) the Court now has

before it orders stating that relief shall be accomplished

on a metropolitan level according to specified guidelines

and commanding affirmative action on the part of defen

dants and interveners that go considerably beyond the

10/ See Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law on

Detroit-Only Plans of Desegregation (March 28, 1972),

- 10 -

• •

mare filing of plans. Orders which were not complete

dispositions of a case have nevertheless been treated

as "final" under 28 U.S.C. 1291, in a variety of cir

cumstances. Practical as opposed to technical construc

tion is accorded to the word "final," see Brown Shoe

Company v. United States, 370 U.S. 294, 304-11 (1962),

and the oft stated competing considerations involved

are: "...[t]he inconvenience and costs of piecemeal

review on the one hand and the danger of denying justice

by delay on the other." Dickinson v. Petroleum Corporation,

y n / — “

338 U.S. 507, 511 (1964).

On the basis of these cases, we feel the merits

of this action are appealable under section 1291. Like

wise, the affirmative action ordered would suggest that

11/ The rule was also summarised by Mr. Justice Frankfurter

in W s concurring opinion in SearsT Roebuck and Company v.

Mackey, 351 U.S. 427, 441 (1956), as follows:

"Thus the Court has permitted appeal

before, completion of the whole liti~

gation when failure to do so would

preclude any effective review or would

result in irreparable injury."

mandatory injunctions of the type appealable under Section

1™/

1292(a), have been issued.

Moreover, from the perspective of the federal govern

ment, we submit that there are additional factors which merit

attention and which are suggested by Section 803 of the

Higher Education Act of 1972. That section became law on

July 1, 1972 and provides:

Sec. 803. Notwithstanding any other law or

provision of law, in the esse of any order on

the part of any United States district court

which requires the transfer or transportation

of any student or students from any school

attendance area prescribed by competent State

or local authority for the purposes of achiev

ing a balance among students with respect to

race, sex, religion, or socioeconomic status,

the effectiveness of such order shall be post

poned until all appeals in connection with such

order have been exhausted or, in the event

no appeals are taken, until the time for such

appeals has expired. This section shall ex

pire at midnight on January 1, 1974.

First, on the element of public interest, Section

803 represents a strong suggestion by Congress that a stay

of proceedings pending appeal is in the public’s interest.

As stated by the Senate manager of the bill, the purpose

12J As to what constitutes a mandatory injunction in the

context of a school desegregation case, compare Taylor v.

Board of Education of New Rochelle, 288 F. 2d 600 (2nd

Cir., 1961), and Board of Public Instruction of Duval County

v. Braxton, 326 F. 2d 616 (5th Cir., 1.964).' ' ~~

12

of Section 803 is:

"[T] o permit the appellate courts to resolve

what were said to he inconsistencies in the appli

cation of school desegregation requirements

by various federal district courts, without

making local school agencies implement district

court's decrees during the time the issue was

being resolved on appeal." 118 Cong. Rec.

(daily ed.) S8378 (May 24, 1972) (Sen. Pell).

It would be appropriate for the Court to honor this state

ment of legislative intent in considering whether a stay

is in the public interest.

Second, without reaching the question whether Section

803 is applicable at this point in the proceedings, there

can be little doubt that the section would require a stay

once a specific plan requiring transfer of students is

13/

ordered by the district court. This underscores the undesir

ability and inequity of subjecting defendants and intervenors

13/ The author of the amendment, Congressman Broomfield,

stated his intent as follows:

"Mr. O'Hara: ... May I inquire of the gentleman

from Michigan if it was his intention that

Section 803 apply to orders that have the practi

cal effect of achieving some, sort of racial

balance, although the court may have stated that

its order was entered for the purpose of correct

ing unconstitutional segregation?

Ifc* BroomfieId: Yes, it was my intention to cover

such cases and specifically, it: was my intention

to cover cases like those now being litigated in

Richmond and Detroit." 118 Cong. Rec. (daily ed.)

H5416 (June 8, 1972).

- 13 -

to orders requiring major changes in the status quo prior

to review of the merits of the constitutional violation.

Without an immediate stay defendants will continue to be

required to take actions necessitating heavy outputs of

resources and expenditures including the purchase of new

15/ 16/

buses,” the special training of faculty and staff, and

17/

the hiring of additional counselors. These actions

are designed to prepare for the partial implementation by

this fall of a plan for desegregation; a plan that would

be stayed by Section 803, if not obviated earlier by

reversal on the merits by this court.

" CONCLUSION

For the above reasons we think a stay should be

granted to enable this Court to hear and determine ques

tions relating to the constitutional merits supporting

the relief contemplated by the trial court. Since the

15/ Order of District Court of July 10, 1972,

16/ See Ruling on Desegregation Area and Order for Develop

ment of Plan of Desegregation, at p. 9 (dated June 14, 1972).

17/ See i_d., at p. 9. -

14

district court assigned no reasons for its denial of a

stay> this Court should itself weigh the respective

interests involved and decide whether they support the

trial court's exercise of discretion.

Respectfully submitted,

RALPH R. GUY„ SR. DAVID L. NORMAN

United States Attorney Assistant Attorney General

0 . i

BRIAN K. LANDSBERG

WILLIAM C. GRAVES

Attorneys

Department of Justice

Washington, D. C. 20330

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that on the 15th day of July, 1972

a copy of the foregoing Memorandum for the United States as

• e

Amicus Curiae was mailed by United States mail, postage pre-

I

paid to the following counsel of record in this action:

Plaintiffs' Attorneys:

Louis R. Lucas

William E . Caldwe11

Ratner, Sugarmon & Lucas

525 Commerce Title Building

Memphis, Tennessee 38103

- Nathaniel Jones

General Counsel, NAACP

1790 Broadway

New York, New York 10019

E. Winther McCroom

3245 Woodburn

Cincinnati, Ohio 45207

Bruce Miller

Lucille Watts

Attorneys for Legal Redress Committee

NAACP-“Detroit Branch

3426 Cadillac Tower

Detroit, Michigan 48226

J. Harold Flannery

Paul Dimond

Robert Pressman

Center for Law and Education

Harvard University

38 Kirkland Street

Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138

Norman J. Chachkin

Jack Greenberg

James N. Nabrit, II

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

De£eudants* Attorneys:

George T. Roumell, Jr.

Louis D. Beer

Wallace D. Riley

Emmet Tracy, Jr.

Riley & Roumell

7th Floor, Ford Building

Detroit Michigan 48226

Honorable Frank J . Kelley

Attorney General, State of Michigan

BY: Eugene Krasicky

Gerald F. Young

Seven Story Office Building

525 West Ottawa Street

Lansing, Michigan 48913

Intervening Defendants:

Theodore Sachs

Ronald R. Reiverston

Rothe, Mars ton, Mazey, Sachs & 0 !Connell, P .C.

1000 Fanner Street

Detroit, Michigan 48226

Alexander B. Ritchie

Fenton, Nederlander, Dodge & Barris, P.C.

2555 Guardian Building

Detroit, Michigan 48226

Robert J. Lord

8388 Dixie Highway

Fair Haven, Michigan 48023

OF COUNSEL:

Paul R. Vella

Eugene R. Bolanowski

30009 Schoenherr

Warren, Michigan 48093

L. Brooks Patterson

2900 West Maple

Troy, Michigan 48084

OF COUNSEL:

Robert E. Manley

John S. Wirthiin

Beirne, Wirthlin & Manley

3312 Carew Tower

Cincinnati, Ohio 45202

Parvin C. Lee, Jr„

1263 West Square Lake Road

Bloomfield Hills, Michigan 48013

Charles J, Porter / .

860 West Long Lake Road

Bloomfield Hills, Michigan 48013

Professor David Hood

Wayne State Unitersity Law School

468 West Ferry

Detroit, Michigan 48202

Douglas H. West

Robert B. Webster #

Hill, Lewis, Adams, Goodrich & Tait

3700 Penobscot Building

Detroit, Michigan 48226

William M. Saxton _

Butzel, Long, Gust, Klein & Van Zile

1881 First National Building

Detroit, Michigan 48226

Richard P, Condit

Condit and McGarry, P.C.

Long Lake Building

860 West Long Lake Road -

Bloomfield Hills, Michigan 48013

Kenneth B. McConnell .

Hartman, Beier, Howlett, McConnell & Googasian

74 West Long Lake Road

Bloomfield Hills, Michigan 48013

Julius M. Grossbart

Leithauser & Grossbart

3400 Guardian Building

Detroit, Michigan 48226

Sherman P. Faunce, II

29500 Van Dyke Avenue

Warren, Michigan 48093

f/j(Ui<Xy ft.

WILLIAM G, GRAVES

Attorney

Department of Justice

Washington, D. C , 20530

nUNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

No. 72-1058

In the matter of:

Carolyn Bradley, et al,

versus

The School Board of the City of «■

Richmond, Virginia, et al,

Appellees,

versus

The School Board of Chesterfield

County, et al,

No. 72-1059In the matter of:

Carolyn Bradley, et al,

versus

The School Board of the City of

Richmond, Virginia, et al,

versus

The School Board of Henrico

County, et al,

In the matter of:

No. 72-1060

Carolyn Bradley, et al,

versus

Appellants.

Appellees,

Appellants.

The School Board of the City of

Richmond, Virginia, et al,

versus

The State Board of Education of the

Commonwealth of Virginia, et al,

Appellees,

Appellants.

Appeals from the United States District Court for the Eastern

District of Virginia, at Richmond.

Upon consideration of the motion for a stay of the

order of the District Court, and the responses, and of the motion

to accelerate the appeal, and the responses,

IT IS NOW ORDERED:

That the Virginia State Board of Education and Dr. Woodrow

W. Wilkerson, State Superintendent of Public Instruction, direct and

coordinate planning for a merger of the school divisions of the City

of Richmond and Henrico and Chesterfield Counties, encompassing all

phases of the ojaeration and financing of a merged school system, to

the end that there will be no unnecessary delay in the implementation

of the ultimate steps contemplated in the order of the District Court

in the event that the order is affirmed on appeal. To that end, but

with regard for the efficient current operation of each of the three

separate divisions, the Virginia State Board of Education and Dr.

Wilkerson may require the three separate school divisions to supply

administrative and staff assistance to develop and assemble data

information and tentative plans looking toward implementation of the

District Court's order. If deemed advisable, they may direct tne

formation of a provisional school board for the merged division and

employ such outside administrators and assistants as may be deemed

practical. Except such costs as are properly attributable to the

Virginia State Board of Education and the Office of the State

Superintendent of Public Instruction, all necessary costs incurred

in connection with the development of such plans shall be shared by

the three school divisions in proportion to the number of pupils in

each division.

Except as provided above, the order of the District Court

is stayed pending the hearing of the appeals on the merits and,

subject to the further order of this Court, thereafter pending a

determination of the appeals on the merits.

2

The appeals are accelerated. An opening brief shall be

filed by each party on or before Wednesday, March 22, 1972, and

each parcy may fxle a reply brief on or before Wednesday, April 5,

1972.

The appeals will be scheduled for hearing before the

Court en banc during the week beginning April 10, 1972.

- «

Any party has leave to suggest to the Court any modifica

tion of this order which it deems essential, and continuance of the

stay order will be considered by the Court after the hearing of the

appeals on the merits.

By direction of Chief Judge Haynsworth

and Judges Craven,, Russ^TT'luhd Field:*

/ \ . in ! “

h 1 8.on> « • \ ? / \ y*. 4 5

Clerk, United States Court of Appeals'

for the Fourth Circuit

x Judge Winter would grant an oral hearing on the motion

for a stay and the responses thereto, but would not

grant a stay without such a hearing. He joins in the

order insofar as it accelerates the appeal and establishes

a schedule for the filing of the briefs and a hearing.

Judge Bryan was not present and took no part in the

consideration and disposition of these motions.

Judge Butzner did not participate in the consideration

or decision of these motions because, as United States

District Judge, he presided over this case from 1962

until 1967. 28 U.S.C. § 47; see Wright v. Emporia,

442 F.2d 570, 575 (1971); Swann v. Charlotte-^Mecklenburg

Bd. of Educ., 431 F.2d 135 (1970).

1 ! •: J

t ' V * i j ' ? t * t . ,, .• v.’lL \ . . ,}'

r.LC 6

" v •'•0

.7 ; / o

r ..j:, 5cu£: 3

WINTER/ Circuit dge, dissenting:

While my barothers purport to assure that there

will be "no unnecessary delay in the implementation of the

ultimate steps contemplated in the order of the district

court, in the event that the order is affirmed on appeal,"

they articulate no reason why the district court's order

should be stayed almost in toto. I dissent from the or

der, and I dissent from their refusal to conduct an oral

hearing at least to determine if what they order is feas

ible and is capable of accomplishment of its announced

objective.

My concept of the rules under which stays should

be granted or withheld was set forth in Long v. Robinson,

432 F.2d 977 (4 Cir. 1970). And, as pointed out in Long,

the rules governing the granting of this extraordinary re

lief are stricter where, as here, the matter has been care

fully considered by the district judge and relief has been

denied. I am, of course, unable to debate the proper ap

plication of those rules by reason of my brothers' silence.

It suffices to say that nothing in the papers convinces me

that under Long a stay should be granted, and I would infer

1

• •

from the lack of any reasons advanced, by the court for i«~s

action that either Long has been totally ignored or that

Long has been considered and no reasons sufficient to meeu

its test for granting relief have been discovered.

Finally/ I protest the refusal of the court to

permit me and the other judges to hear argument on' the

applications and the responses. In a case and matter of

this importance, it would seem to me to be elementary fair

ness to the parties and to the judges of the court to per

mit. all to explore in oral argument the merits and demerits

of possible courses of action. Additionally, the court has

entered an order in a form requested by no one. While it

grants a stay, it purports to protect the plaintiff's

rights. Whether it is feasible and workable, or whether

it is an empty gesture, is a matter of speculation. I

would think that the court would at least want the assur

ances that its order is not futile that might stem from

oral argument.

r-" Jt H L.'| Si ;.) .

GAY.'JCL V/. P'.liiii.’S

, 3:jT?

r-.tr

(pa)

■r

- 2 -