Bakke v. Regents Brief for the Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights Under Law as Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1976

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Bakke v. Regents Brief for the Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights Under Law as Amicus Curiae, 1976. d855b94d-be9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/beb11d82-c1a7-44e6-878d-443db3d27c03/bakke-v-regents-brief-for-the-lawyers-committee-for-civil-rights-under-law-as-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

JAMES M. NA8RJT, III

Ksocimcoum

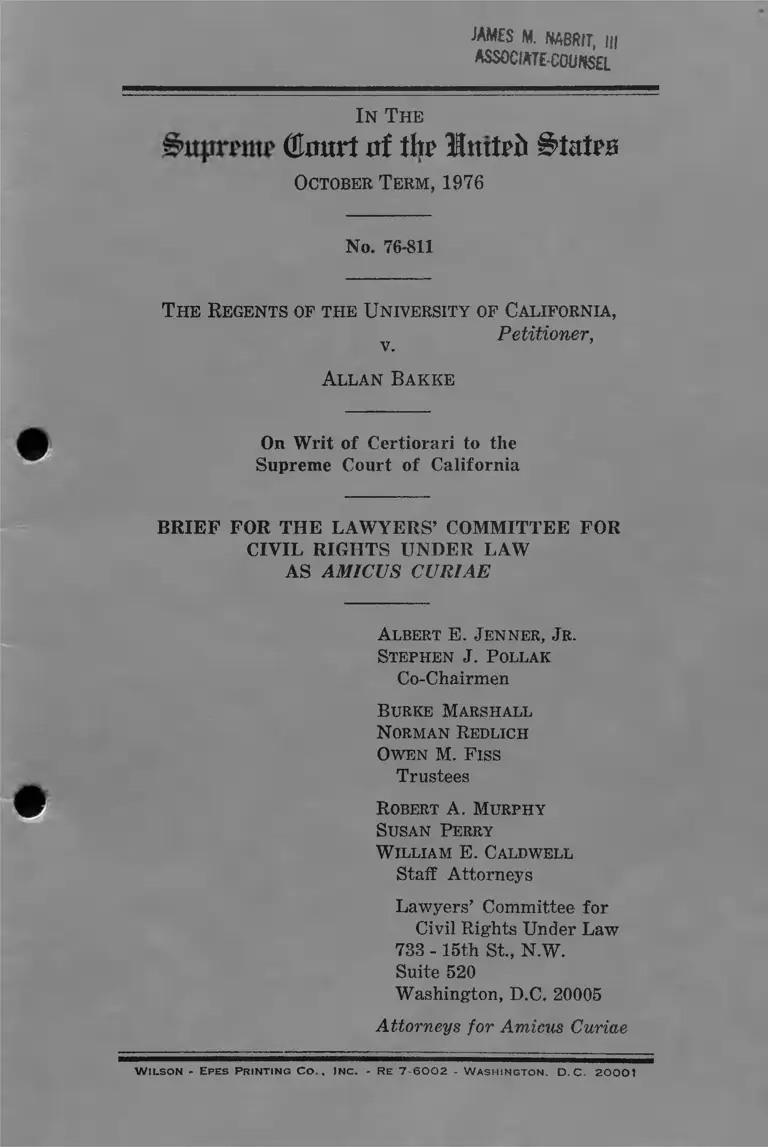

I n The

dmtrt at tlrr Intted §tat?B

October Term, 1976

No. 76-811

The Regents of the University of California,

Petitioner, v. ’

Allan Bakke

On Writ of Certiorari to the

Supreme Court of California

BRIEF FOR THE LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE FOR

CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER LAW

AS AMICUS CURIAE

Albert E. J enner , J r.

Stephen J . P ollak

Co-Chairmen

Burke Marshall

N orman Redlich

Owen M. F iss

Trustees

Robert A. Murphy

Susan P erry

W illiam E. Caldwell

Staff Attorneys

Lawyers’ Committee for

Civil Rights Under Law

733 - 15th St., N.W.

Suite 520

Washington, D.C. 20005

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae

W i l s o n - Ef e s p r i n t i n g C o . . In c . - r e 7 - 6 0 0 2 - W a s h i n g t o n , d . c . 2 0 0 0 1

I N D E X

Page

Interest of Amicus Curiae ---------------- --- --------------

Introduction and Summary of Argument----------------

Argument ------ --- -..... -................... -..... — --- -----------

I. Special Admissions Policies, Such As That of

Davis, That Are Designed to Increase Minority

Matriculation Into Professional Schools Serve

Sound Educational Needs and Basic State and

National Interests................ ....... .... --- ----------

A. The State’s Decision to Increase Minority

Matriculation in Its Medical School Is Con

stitutionally Permissible------------------------

B. The Means Used Are Also Permissible - .....

II. The Equal Protection Clause Does Not Require

This Court To Forbid the Implementation of

Such Policies by State Institutions --------------

A. The Purpose of the Special Admissions Pro

gram Is Permissible Under the Fourteenth

Amendment Because It Does Not Stigmatize

Any Person or Class of Persons Because of

Race ________________________ _______

B. The Class to Which Plaintiff Belongs Is Not

Entitled to the Extraordinary Judicial Pro

tection Afforded “Discrete and Insular”

Minority Groups --------------------------- ------

C. The Use of Racial Criteria by the State in

Allocating Scarce Resources Is Constitution

ally Permissible Where Its Purpose and

Effect Is to Overcome the Effects of Societal

Discrimination ------------------------------------

D. The Fact That the Special Admissions Pro

gram May Impose Some Disadvantage on

Individual Members of Groups Not Directly

Benefitted by the Program Is Not Sufficient

to Make the Program Invalid ......................

1

4

6

6

7

9

13

15

16

18

20

II

INDEX—Continued

Page

III. The Details of the Specific Special Admissions

Program Adopted by Davis Do Not Make It

Constitutionally Objectionable --------- 22

A. The Existence of a Separate Admissions

Track Does Not Invalidate the Program ..... 22

B. The Use of Numerical Goals for Minority

Admissions Does Not Invalidate the Pro

gram ......... .................................... ------ -------- 24

Conclusion ------------------------------- 26

Ill

TABLE OF CITATIONS

CASES: Page

Arnold v. Ballard, C.A. No. C-73-478 (N.D. Ohio,

Sept. 20, 1976) _______ .......... - ..... -.............. - 3

Associated General Contractors of Mass., Inc. V.

Altshuler, 490 F.2d 9 (1st Cir. 1973), cert, de

nied, 416 U.S. 957 (1974) .... .......................... - 20n

Brown V. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483

(1954) ........................ ............................... 11

Califano V. Goldfarb, ----- U.S. ----- , 97 S. Ct.

1021 (1977) - - - ..........- ......................... - 19

Califano V. Webster, ----- U.S. ----- , 97 S. Ct.

1192 (1977) - ...... - ..............................................- 19

Castaneda V. Partida, ----- U.S. ----- , 97 S. Ct.

1272 (1977) .... - ..... .......... -.................................15,16n

Connecticut General Life Ins. Co. V. Johnson, 303

U.S. 77 (1938) ___________ __ - .... ............... 2n

Contractors Ass’n of Eastern Pa. V. Secretary of

Labor, 442 F.2d 159 (3d Cir.), cert, denied, 404

U.S. 854 (1971) .... ...... ......... -......................... - 20n

Craig V. Boren, ----- U.S. ----- , 97 S. Ct. 451

(1976) ........ ........................................................... 17

DeFunis V. Odegaard, 416 U.S. 312 (1974) -------- 3,10

Epperson V. Arkansas, 393 U.S. 97 (1968) .........— 22

Franks V. Bowman Transportation Co., 424 U.S.

747 (1976) ___ ___________ - ---------- 5, 12,13,18, 21

Graham V. Richardson, 403 U.S. 365 (1971) ------ 17

Grayson V. Harris, 267 U.S. 352 (1925) ...... .......... 6n

Hernandez V. United States, 347 U.S. 475 (1954).. 17

Kahn v. Shevin, 416 U.S. 351 (1974) -------------- 19, 22

Keyes V. School Dist. No. 1, 413 U.S. 189 (1973).. 15

Lau V. Nichols, 414 U.S. 563 (1974)....................... 19

Lemony. Kurtzman, 411 U.S. 192 (1973) ........... . 21

Massachusetts Board of Retirement V. Murgia, 427

U.S. 307 (1976) - .................................................. 17

Morrow V. Crisler, 491 F.2d 1053 (5th Cir.) (en

banc), cert, denied, 419 U.S. 895 (1974)-------- 3

Morton V. Mancari, 417 U.S. 535 (1974) ...... ........ 19

North Carolina State Board of Education V.

Swann, 402, U.S. 43 (1971) ................................ 22

IV

TABLE OF CITATIONS—Continued

Page

Nyquist V. Lee, 402 U.S. 395 (1971), aff’g 318 F.

Supp. 710 (W.D. N.Y. 1970) „----------------- --- - 19

Palmer V. Thompson, 403 U.S. 217 (1971) --------- 18

Paschall V. Christie-Stewart, Inc., 414 U.S. 100

(1973) ........................-................. - ..... -------------- 6n

Porcelli V. Titus, 431 F.2d 1254 (3d Cir. 1970) ...... 20n

San Antonio Independent School District V. Rod

riguez, 411 U.S. 1 (1973) __________ ______ 17

South Carolina V. Katzenbach, 383 U.S. 301

(1966) ...... .......... .......... .. ......... -------------------- 18

Southern Illinois Contractors Ass’n V. Ogilvie,

471 F.2d 680 (7th Cir. 1972) _______________ 20n

Swann V. Charlotte-Mecklenberg Board of Educa

tion, 402 U.S. 1 (1971) _____ __- ......... -5,18-19, 24

Teamsters V. United States, 45 U.S.L.W. 4506

(May 31, 1977) ______ ____________________ 21

United Jewish Organizations of Williamsburgh,

Inc. V. Carey, ----- U.S. ----- , 97 S. Ct. 996

(1977) ...... .............. .... .....................-__ ____ _passim

United States V. Carotene Products Co., 304 U.S.

144 (1938) ................................................. 17

United States V. Louisiana, 380 U.S. 145 (1965)- 19

United States V. Montgomery Board of Education,

395 U.S. 225 (1969) ______________________ 24

United States V. Price, 383 U.S. 787 (1966)------- 2n

Village of Arlington Heights V. Metropolitan

Housing Development Corp.,----- U .S .------ , 97

S. Ct. 555 (1977) _______________ ___ _____ 15

Washington V. Davis, 426 U.S. 229 (1976) -------- 15, 18

Wheeling Steel Corp. V. Glander, 337 U.S. 562

(1949) __________ ______ _______________ 2n

STATUTES; EXECUTIVE ORDERS AND LEGIS

LATIVE MATERIALS

Civil Rights Act of 1964, tit. VI, VII, 42 U.S.C.

§ 2000a, 2000e et seq. ___________ ________ 6n, 12

V

TABLE OF CITATIONS—Continued

Page

24 C.F.It. §200.600 (1976) .... ............... ......... .... 19

Executive Order 11246, pt. II, 3 C.F.R., 1964-1965

Comp. 339, as amended by Executive Order

11375, 3 C.F.R., 1966-1970 Comp. 684 ........... . 19

H. Rep. No. 92-238, 92d Cong., 1st Sess. 8 (1972).. 18

MISCELLANEOUS:

Bator, P., P. Mish k in , D. Shapiro & H. Wechs-

ler, Hart & Wechsler’s T he F ederal Courts

& The Federal System (2d ed. 1973) ______ 6n

Educational Testing Service, Applications and Ad

missions to ABA Accredited Law Schools

(Princeton, N.J., May 1977) .................... .......... 9

Edwards & Zaretsky, Preferential Remedies for

Employment Discrimination, 74 Mich. L. Rev. 1

(1975) ____ ____________ ___________ ____ 24

Ely, The Constitutionality of Reverse Racial Dis

crimination, 41 U. Chi. L. Rev. 724 (1974) ---- 12

Fiss, Groups and the Equal Protection Clause, 5

Phil. & Pub. Aff. 107 (1976) ____ ___________ 17

Graham, The “Conspiracy Theory” of The Four

teenth Amendment, 47 Yale L. J. 371 (1937).... 2n

Kartz & Horowitz, Affirmative Action and Equal

Protection, 60 Va. L. Rev. 955 (1974)________ 25

O’Neil, Preferential Admissions: Equalizing the

Access of Minority Groups to Higher Educa

tion, 80 Yale L. J. 699 (1971)______________ 23

Sandalow, Racial Preferences in Higher Educa

tion: Political Responsibility and the Judicial

Role, 42 U. Chi. L. Rev. 653 (1975)................... 10

Note, Reading the Mind of the School Board: Seg

regative Intent and the De Facto/De Jure Dis

tinction, 87 Yale L. J. 317 (1976)___________ 15

In The

ji>itprotu> (Emtrt uf %

October Term, 1976

No. 76-811

The Regents of the University of California,

Petitioner,

v.

Allan Bakke

On Writ of Certiorari to the

Supreme Court of California

BRIEF FOR THE LAWYERS’ COMMITTEE FOR

CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER LAW

AS AMICUS CURIAE

INTEREST OF AMICUS CURIAE *

The Lawyers’ Committee for Civil Rights Under Law

was organized in 1963 at the request of the President

of the United States to involve private attorneys through

out the country in the national effort to assure civil

rights to all Americans. The Committee’s membership

today includes two former Attorneys General, nine past

Presidents of the American Bar Association, two former

* The parties’ letters of consent to the filing of this brief have

been filed with the Clerk pursuant to Rule 42(2).

2

Solicitors General, a number of law school deans and

professors, and many of the nation’s leading lawyers.

Through its national office in Washington, D.C. and its

offices in Jackson, Mississippi and eight other cities,

including two in California, the Lawyers’ Committee

over the past fourteen years has enlisted the services

of over a thousand members of the private bar in ad

dressing the legal problems of minorities and the poor

in voting, education, employment, housing, municipal

services, the administration of justice, and law enforce

ment.

The Lawyers’ Committee has a number of vital inter

ests at stake in this case, the correct interpretation and

application of the Fourteenth Amendment being foremost

among them. The Fourteenth Amendment’s promises of

racial equality have received meaningful attention for

only a small part of the Amendment’s 110-year history,

and those promises are far from being fulfilled. During

the past two decades the law has developed its apologia

for the fact that “for many years after Reconstruction,

the Fourteenth Amendment was almost a dead letter as

far as the civil rights of Negroes were concerned. Its

sole office was to impede state regulation of railroads or

other corporations.” 1 In the case at bar, the California

Supreme Court, in holding that the Fourteenth Amend

ment prohibits a state medical school’s affirmative ad

missions program designed to bring racial equality into

the medical profession, has again diverted the Amend

ment from its intended course. The Amendment cannot

1 United States v. Price, 383 U.S. 787, 801 n.9 (1966). See gen

erally Wheeling Steel Cory. v. Glander, 337 U.S. 562, 576-81 (1949)

(Douglas, J., dissenting); Connecticut General Life Ins. Co. v.

Johnson, 303 U.S. 77, 85-90 (1938) (Black, J., dissenting) ; Graham,

The “Conspiracy Theory” of the Fourteenth Amendment, 47 Yale

L. J. 371 (1937).

3

and should not sustain another major diversion, such as

that portended by the judgment below.

The Lawyers’ Committee has litigated a number of

Fourteenth Amendment cases resulting in remedial or

ders directing state and local governments to utilize

race-conscious means to eradicate the persisting mani

festations of long-standing official racism, see, e.g., Mor

row v. Crisler, 491 F.2d 1053 (5th Cir.) (en banc),

cert, denied, 419 U.S. 895 (1974), and we have negoti

ated a number of consent decrees providing for similar

relief. See, e.g., Arnold v. Ballard, C.A. No. C-73-478

(N.D. Ohio, consent decree entered Sept. 20, 1976).

While the California Supreme Court’s decision in the

instant case does not directly affect the validity of such

remedial orders (see Pet. App. pp. 29a-32a), the ra

tionale of that decision, if affirmed by this Court, would

present serious practical obstacles to our efforts to secure

such relief through the courts and, especially, through

the negotiation process.

Finally, the detrimental impact of the decision below

on the accessibility of graduate and professional school

education, and ultimately the professions themselves, to

members of minority groups is of vital concern to us—

particularly as that impact affects the racial composition

of the legal profession, a concern which we expressed

in our amicus brief in DeFunis v. Odegaard, 416 U.S.

312 (1974). Since 1970 we have operated through our

Mississippi office a Minority Lawyer Leadership, Train

ing and Development Program, the purpose of which is

to help develop an economically viable private black bar

able and willing to respond to the special and general

needs of Mississippi’s black residents. Under this con

tinuing program at least nine young black attorneys

have successfully established private practices in Mis

sissippi towns which previously had few or no black

lawyers. The continued success of this program obviously

4

depends on the availability of black law-school graduates,

which in turn heavily depends on the continuation of

special admissions programs such as the one invalidated

by the court below. Affirmance of the decision below

would impede our Mississippi program, and it would

negate the small steps that have been taken throughout

the nation to diversify the bench and bar by opening the

profession to minorities.

Accordingly, the Lawyers’ Committee files this brief

as friend of the Court urging reversal.

INTRODUCTION AND SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

What is involved in this case is a special admissions

program adopted by the faculty of a state medical school

to bring racial diversity to a student body and to a pro

fession that would otherwise continue virtually all-white

for an indefinite period.

The goal of such a program is fully consistent with

the history and aims of the Equal Protection Clause.

It reflects a great national purpose, exhibited in federal

and state appointment policies, a wide range of legisla

tion, and innumerable job programs, as well as similar

admissions policies of countless educational institutions,

to bring racial diversity to all segments and all levels

of American life. The program also serves sound educa

tional policies reflecting the considered professional judg

ment of the distinguished institution that adopted it,

and the needs of the profession that institution represents

and serves.

The developed constitutional doctrine of the Equal Pro

tection Clause is not so rigid as to prohibit the states

from adopting such programs. It is plain from such cases

5

as United Jewish Organizations of Williamsburgh, Inc.

v. Carey, 97 S. Ct. 996 (1977), and Swann v. Charlotte-

Mecklenberg Board of Education, 402 U.S. 1 (1971),

that the states are not barred per se from taking race

into account in devising and implementing state policies

in which factors of race are inextricably implicated.

Where scarce and valuable state resources (such as jobs,

or places in professional schools) are at issue, such poli

cies may inescapably, and at random, damage the eco

nomic interests of individual members of nonminority

groups. That is a transitional inequity that is the cost

of permitting such programs, but it should not alone in

validate them, compare Franks v. Bowman Transporta

tion Co., 424 U.S. 747 (1976), absent any element of

racial oppression, of perpetuation or protection of pre

ferred positions, or of invidious discrimination against

any group. None of these factors is present here, and

the state’s program should accordingly stand.

6

ARGUMENT

I. Special Admissions Policies, Such As That of Davis,

That Are Designed to Increase Minority Matriculation

Into Professional Schools Serve Sound Educational

Needs and Basic State and National Interests.

What the Supreme Court of California has done here

is to interpret the Fourteenth Amendment2 to forbid

a state university from implementing student admissions

policies that are designed essentially to bring racial di

versity to the virtually all-white populations that might

otherwise exist in professional schools, and in the pro

fessions for which they train their students. That is

the fundamental, dominant purpose of the Davis special

admissions program for “disadvantaged” applicants. If

the Amendment truly requires this result, it must be

because the process of constitutional litigation has frozen

2 The trial court held that the Davis special admissions program

also violated Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C.

§ 2000d, and the Privileges and Immunities Clause of the California

Constitution, Art. 1, § 21. (Pet. App. p. 117a). That court’s holding

as to the California Constitution accordingly constitutes an inde

pendent and sufficient non-federal ground for its injunction. The

Supreme Court of California, however, did not address itself either

to the statutory or the state constitutional issue, and neither

party here has raised a question as to this Court’s jurisdiction. It

is, of course, true in general that the existence of a potential non-

federal ground for the decision of the highest court of a state does

not defeat jurisdiction here where the state court does not con

sider the potential state ground. See, e.g., Grayson v. Harris, 267

U.S. 352, 358 (1925). Since the judgment of the trial court would

be left standing in this case whatever the disposition of the federal

ground, however, the procedure followed in Paschall v. Christie-

Stewart, Inc., 414 U.S. 100 (1973), seems possibly applicable. We

do not urge the Court to follow that route because we believe, first,

that the petitioner is entitled to a reversal of the court below

on the federal constitutional ground on which its decision rests,

with the state constitutional issue then left to the California courts

for disposition, see P. Bator, P. Mish k in , D. Shapiro & H. Wechs-

ler, Hart & Wechsler’s The F ederal Courts & The F ederal

System , 478, 458 (2d ed. 1973) ; and, second, that the federal con

stitutional issue presented needs to be finally decided by this Court.

7

construction of the Amendment into a rigid pattern of

doctrine that outlaws state action designed to achieve

racial equality and justice, the Amendment’s most basic

purpose.

Section II of our argument demonstrates that the

Court’s decisions do not establish any such pattern. This

section is intended simply to show that the kind of ad

missions program used by Davis is a reasonable and

rational way, well within the area of discretion that it

should be allowed, for an educational institution to deal

with the danger of perpetuation of a professional caste

system.

A. The State’s Decision to Increase Minority Matricu

lation in Its Medical School Is Constitutionally

Permissible.

In the first place, it is reasonable for a professional

school to decide that it wants, for its own purposes and

own educational needs, to have significant racial diversity

in its student body and its faculty. The damage done

by racial segregation in educational institutions is at

least not necessarily limited to that inflicted on the ex

cluded minority group. White students need the diversity

of experience and professional interests that may come

only from sharing the educational process with blacks

and other minorities. This could reasonably be supposed

by educators to contribute to innovation in the develop

ment of research priorities, curriculum, and other aca

demic insights. The law schools are responsive to educa

tional needs that they did not perceive before the in

stitution by many of them of special admissions pro

grams similar to that adopted by Davis for medical stu

dents, and it is certainly at least plausible, and not un

reasonable, for those responsible for the educational pro

grams at those schools to believe that the two facts, of

diversity and innovation, are not unrelated. In like vein,

8

it is surely not arbitrary for medical schools to conclude

that their educational program will be enriched by the

presence of racial diversity in their student bodies.

Second, it is also reasonable for a professional school,

especially a state institution supported by public moneys,

to decide that it has an educational responsibility to

prepare a racially diverse group for the profession. Race

is, in fact, an important factor for the doctor or lawyer

in choosing what kind of practice to pursue, in what

location, and for the custom of what kinds of clients.

Further, doctors perform important functions in deter

mining priorities and modes for the delivery of health

services, as lawyers and judges do for legal services.

In all the varieties of judgments that need to be made

in such matters, it is certainly not irrational to believe

that racial diversity is desirable, indeed essential. Nor

is it inconsistent with known facts to think that clients

to be served by the professions, particularly the poor, the

under-represented, and the disadvantaged, deserve the

choice of the opportunity of consulting with racially

identifiable doctors or lawyers they believe will best

understand and sympathize with their problems; it is

certain that race has, in fact, played an enormously im

portant role in their own lives.

Third, it would be reasonable for educators to con

clude that a special admissions program was essential to

achieving these ends, at least for a transitional period

of uncertain duration. The only evidence in the record

on the point is to that effect: “In the judgment of the

faculty of the Davis Medical School, the special admis

sions program is the only method whereby the school

can produce a diverse student body which will include

qualified students from disadvantaged backgrounds.”

(Testimony of admissions committee chairman; Pet. App.

p. 75a). As the amici briefs filed in this case demon

strate, a large number of other private and state pro-

9

fessional schools have reached similar judgments. As

to law schools, these judgments are reinforced, although

not necessarily proved correct, by a May 1977 study of

applications and admissions to ABA accredited law

schools.3

B. The Means Used Are Also Permissible.

To be sure, a state institution cannot accomplish even

these appropriate ends through unconstitutional means.

The majority of the Supreme Court of California ap

parently concluded that that was what Davis had done

here. Yet, as we show in section II, there are no suffi

cient countervailing considerations of constitutional di

mensions created by the type of special admissions pro

gram adopted by Davis to place it outside the parameters

of permissible state action. We show in section III that

neither do such obstacles arise from the details of the

specific plan they have chosen to adopt. Here we simply

point out that the means used are entirely reasonable.

First, there is no merit to the assumption of the court

below that special admissions programs designed to in

crease minority matriculation in professional schools are

3 Educational Testing Service, Applications and Admissions to

to ABA Accredited Law Schools, (May, 1977, copyright by Law

School Admission Council; mimeographed; Educational Testing

Service, Princeton, N.J. 08540). The fact is that not enough is

known about why minority applicants statistically make lower

scores on such intended objective tests, as the MCAT (for medicine)

and the LSAT (for law). In summary, however, the Educational

Testing Service analysis referred to does show that admissions

policies based solely or predominantly on the predictors measured

by the LSAT and related quantifiers would operate severely to limit

access to legal education and the profession by blacks, Chicanos,

and possibly members of other minority groups. Id. at pp. xiii, xvi-

xviii. One statistic cited by the analysis is that of 1539 black Ameri

cans admitted to 129 ABA approved law schools in 1976, only 285

would have been admitted if their ethnic identity had been unknown,

according to the judgment of the law schools admitting them. Id.

at 64, Table 26. It goes without saying that the effects would be

greatest in the best and most prestigious professional schools, such

as the University of California Medical School at Davis.

10

valid only if color-blind and implemented without express

or implicit consideration of race.

By such a program, a university aims to integrate its

student body and the profession generally, and to al

leviate the medical problems of the minority community.

It is hard to see how the state’s concededly racial goals

can be achieved equally well if the state ignores race.

To insist that it do so is to condemn it to bad faith,

or to the adoption of a grossly ineffectual means to its

end.

The alternatives to explicit racial classification most

frequently urged are programs that focus on disadvan

taged persons generally. Such programs, it is argued,

permit a university to achieve racial goals indirectly,

since some or many of the disadvantaged admittees will

be minorities. The first vice of these programs is that

they are ineffectual. They would force universities to

admit large numbers of disadvantaged students in order

to obtain the number of minority students they regard

as optimal. One commentator has estimated in connec

tion with DeFunis v. Odegaard, 416 U.S. 312 (1974),

that, in order to achieve in a racially neutral way the

state’s goal of approximately 15% minority representa

tion in the student body, the University of Washington

Law School would have had to use special admissions

criteria for 40-50 % of its class. Sandalow, Racial Pref

erences in Higher Education: Political Responsibility

and the Judicial Role, 42 U.Chi.L.Rev. 653, 690 n. 113

(1975).

A second vice of this alternative is its disingenousness.

The University’s goal is integration. To select a racially

“neutral” criterion for the purposes of promoting in

tegration cannot honestly be described as a “nonracial”

decision. To suggest that the University may accomplish

sub rosa what it is constitutionally prohibited from ac-

11

complishing de jure is to invite, not without irony, the

very evasiveness that has hindered the implementation of

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954).

The court below also suggested that “the University

might increase minority enrollment by instituting aggres

sive programs to identify, recruit, and provide remedial

schooling for disadvantaged students.” 553 P.2d at 1166

(Pet. App. p. 26a). Yet this suggestion is afflicted with

the same vices as its predecessor. If recruiting and reme

dial programs focus on disadvantaged students generally,

they are an ineffectual and disingenuous means to a

racial and ethnic end. If such programs focus on minority

students in particular, they simply move the racial pref

erence one step away. Exceptional measures taken to pre

pare minorities for a competitive admissions process pre

fer them as surely as does a preference in the admissions

process itself.

Second, it is also not true, as the court below seems

to believe, that special admissions programs abandon the

principles of merit and achievement for a nakedly racial

goal. They do not involve racial quotas in the sense that

race is substituted as a sole standard for some percentage

of the students to be admitted. No doubt one reason for

the need for special admissions programs is the absence of

sufficiently sophisticated admissions standards that can

accurately identify the members of a student body that

will adequately reflect the diverse and various needs of

the educational institution and the profession for which it

trains. Probably no such standards can be created to

choose from among 1000 to 1500 applicants, all of whom

appear to be qualified for the academic demands they

will face. Yet it is clear that the MCAT (for medicine)

and LSAT (for law) scores, and college grades that go

with them, do not purport to measure probable merit or

achievement in a profession, but only serve as statistical

ly accurate predictors of good grades in the first two or

12

three semesters in. a school. It is not at the sacrifice of

the goal of turning out good lawyers and doctors, but

only at the potential sacrifice of more predictable early

academic performance, that special admissions programs

are put in effect.

Third, it is perfectly apparent that there is no smell

of oppression present in such programs. Their guiding

principle is inclusion, not exclusion. Whether wise or not,

the programs are reasonable responses to educational,

professional, and societal needs for full minority partici

pation in the learned professions. They contain no hint

of a majority, or a politically dominant group, attempt

ing to protect itself or its own prior positions or per

quisites from inroads by insurgent minorities. Compare

Ely, The Constitutionality of Reverse Racial Discrimina

tion, 41 U.Chi.L.Rev. 724 (1974). They are instead transi

tional steps, pending the achievement of a more complete

racial equality in the professions, which the political proc

ess can be counted on to abolish when the felt need for

them no longer exists.

The fact that a scarce resource—admission to a limited

student body, membership in which is valuable-—is in

volved does not by itself invalidate the program, even

though that fact necessarily means transitional inequities

will occur to the disadvantage of some individuals such

as respondent, who are not members of the groups that

are the targets of special admissions programs. In

Franks V. Bowman Transportation Co., 424 U.S. 747

(1976), this Court ordered the granting of seniority re

lief to members of a class (black nonemployee applicants)

who were denied jobs by reason of discriminatory hiring

practices taking place after the effective date of Title

VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. 2000e

et seq. It did so despite explicit claims that the district

court had denied such relief, in the exercise of its equita

ble discretion, because it believed the award of such re-

13

lief would conflict with the economic interests of white

employees. 424 U.S. at 773-779. No constitutional claim

was raised, but it would make no constitutional sense to

say that a federal statute could permissibly require that

result, while the Fourteenth Amendment forbade a state

from doing the same thing voluntarily.

This Court’s decisions afford no basis for concluding

that it makes a constitutional difference whether a special

admissions program such as that used by Davis serves

a specific remedial purpose, parallel to that in Franks v.

Bowman Transportation Co., supra, or other legitimate

state needs. See discussion, pages 19-20 infra. It is suf

ficient to emphasize at this point that the specific educa

tional and professional purposes identified above are re

inforced constitutionally because they also serve plain con

cepts of compensatory and corrective justice that are

recognized to lie at the core of the Fourteenth Amend

ment. They are efforts, probably the most significant ef

forts institutions of higher education could make, towards

a solution of the nation’s most intractable problem, which

is its heritage from years of institutionalized, legally en

forced, socially accepted, and invidiously pervasive racial

oppression, with its enduring debris.

II. The Equal Protection Clause Does Not Require This

Court to Forbid the Implementation of Such Policies

by State Institutions.

The appropriate state institution-—the medical school

with the function of producing doctors—has made its

judgment here as to the standards by which it should

choose its student body from among a large pool of quali

fied applicants most of whom must be rejected. These

standards include considerations of race. As we have

shown, the reasons that justify the university’s decision

to do so are founded on sound principles of higher edu

cation, the requirements of the medical profession, and

state and national traditions of justice.

14

It is, of course, recognized that the Court will not in

validate the state’s judgment on these matters because

the Court would not necessarily make the same judgment

itself. The question is whether the state’s judgment is

permissible under the Equal Protection Clause. In sum

mary, we believe that it is evident that the state’s judg

ment may not be invalidated, under the decisions of this

Court, merely because race was taken into consideration.

The use of racial criteria by the state for any purpose

should indeed be given close scrutiny, but such use is es

sential for some purposes, including the desegregation of

school systems. It is permissible here because it does not

cast a stigma on anyone, because the affected class is

not entitled to extraordinary judicial protection, and be

cause there is a showing of sufficient need for the use of

the racial criteria. We recognize that the effect is to

impose costs on some individuals who do not meet the

racial criteria used. That is why the case is here; it is

the inescapable consequence of any system of allocating-

scarce resources that includes the use of racial criteria.

We do not believe that the existence of such costs is suf

ficient to make the use of such criteria impermissible.

Plaintiff does not contend that he was denied admission

to the medical school because of the University’s discrimi

nation against him as a white, or against whites gener

ally. Nor can he accurately claim that he was denied

admission to the special admissions program because of

his race. Rather, and the distinction is a crucial one, his

complaint runs against the University’s decision to fill

a number of places in its entering class with minority

applicants through the special admissions program, thus

making fewer places available through the regular admis

sions process. His case, in other words, depends not on

a showing of discrimination against him, which could not

be made, but on claimed incidental damages to him from

15

benefits, or preferences, given a minority group. Unless

the state is forbidden all programs conferring any such

preferences, therefore, the claim fails.

A. The Purpose of the Special Admissions Program Is

Permissible Under the Fourteenth Amendment

Because It Does Not Stigmatize any Person or

Class of Persons Because of Race.

The parties and some of the amici may join issue on

whether the discrimination allegedly inherent in the spec

ial admissions program is purposeful or intentional with

in the contemplation of this Court’s decisions in such

cases as Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229 (1976). See,

e.g., Castaneda v. Partida, 97 S. Ct. 1272 (1977) ; Village

of Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan Housing Develop

ment Corp., 97 S. Ct. 555 (1977); Keyes V. School Dist.

No. 1, 413 U.S. 189 (1973). To the extent that the “pur

pose or intent” standard is in need of further refinement,

cf. Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229, 253-54 (Stevens,

J., concurring) ; United Jewish Organizations of Williams-

burgh, Inc. v. Carey, 97 S. Ct. 996, 1017 (1977) (Stewart,

J., joined by Powell, J., concurring) ; Note, Reading the

Mind of the School Board: Segregative Intent and the De

Facto/De Jure Distinction, 87 Yale L.J. 317 (1976), the

need is not presented by this case. The precise question

here, rather, is whether the explicit racial purpose of the

special admissions program is an impermissible one. We

show that it is not.

As the Court has recently held, the “deliberate” use of

race “in a purposeful manner” as one criterion of choice

is not constitutionally invalid where such use represents

“no racial slur or stigma with respect to whites or any

other race.” United Jewish Organizations of Williams-

burgh, Inc. v. Carey, supra, 97 S. Ct. at 1009 (plurality

opinion). The remedial nature of the special admissions

program, designed to integrate rather than to segregate,

16

and its enactment by a majority-race decision-maker “belie

the possibility that the decision-maker intended a racial

insult or injury to those [members of the majority] who

are adversely affected by [its] operation. . . Id. at 1016

(Brennan, J., concurring in part).4 The court below spe

cifically held that whites “are not . . . invidiously dis

criminated against in the sense that a stigma is cast

upon them because of their race.” 553 P.2d at 1163

(Pet. App. p. 19a). Moreover, there is no claim that the

special admissions program causes, or is the result of, any

animus against a discrete group within the majority.

Cf. United Jewish Organizations, supra, 97 S. Ct. at

1014, 1016 n. 7 (Brennan, J., concurring in part).

The purpose of the special admissions program, there

fore, is not impermissible under the Equal Protection

Clause. This conclusion is bolstered by the fact that the

class against which the program allegedly discriminates

is not a class entitled to extraordinary judicial protection

under the Fourteenth Amendment, our next point.

B. The Class to Which Plaintiff Belongs Is Not En

titled to the Extraordinary Judicial Protection

Afforded “Discrete and Insular” Minority Groups.

The notion that racial classifications in certain contexts

are presumptively unconstitutional derives from a special

judicial solicitude for the fate of historically disadvan

taged minority groups. Strict scrutiny of state actions

which affect “suspect classes” is a deviation from tradi

tional judicial deference to the judgments of other gov-

4 In Castaneda V. Partida, 97 S. Ct. 1272, 1282 (1977), the Court,

considering the question of discrimination from an evidentiary

perspective, deemed it “unwise to presume as a matter of law that

human beings of one definable group will not discriminate against

other members of that group.” Here, by contrast, the question is

not one of proof but of justification. The Court acknowledged that

distinction in Castaneda by its reference to “a case where a ma

jority is practicing benevolent discrimination in favor of a tradi

tionally disadvantaged minority.” Id. at 1282 n. 20.

17

ernmental agencies which occurs when history has proven

the futility of reliance upon such agencies to secure equal

treatment for a “discrete and insular” minority group.

United States v. Carotene Products Co., 304 U.S. 144,

152-53 n. 4 (1938). See also Hernandez v. United States,

347 U.S. 475 (1954), and Graham V. Richardson, 403

U.S. 365 (1971). The nonminority applicants who would

have been admitted to the medical school at the Univer

sity in the absence of the special admissions program

hardly qualify for this extraordinary judicial aid. The

majority below acknowledged that “the white majority is

pluralistic, containing within itself a multitude of re

ligious and ethnic minorities.” 553 P.2d at 1163 (Pet.

App. p. 19a). There has not been-—nor could there likely

be—any demonstration that this class has been “saddled

with such disabilities, or subjected to such a history of

purposeful unequal treatment, or relegated to such a posi

tion of political powerlessness as to command extraordi

nary protection from the majoritarian political process.”

San Antonio Independent School District v. Rodriguez,

411 U.S. 1, 28 (1973). See also Massachusetts Board of

Retirement v. Murgia, 427 U.S. 307, 313 (1976) ; Craig

v. Boren, 97 S. Ct. 451, 464, n. 1 (1976) (Stevens, J.,

concurring). Rather, this class represents the same kind

of “large, diverse and amorphous” group which this Court

found not entitled to extraordinary judicial protection in

the Rodriguez case, supra. See also Fiss, Groups and the

Equal Protection Clause, 5 Phil. & Pub. Aff. 107 (1976).

It has been suggested that one of the particular dang

ers in the use of race as a factor in the allocation of

scarce resources is that “discrete and insular” subgroups

among the majority will be called upon to bear a dispro

portionate part of the “immediate direct costs of benign

discrimination.” United Jewish Organizations, supra,

97 S. Ct. at 1014 (Brennan, J., concurring in part). The

dissenting justice below noted this concern, and pointed

out that “there is . . . absolutely no indication in the in-

18

slant record that the special admission program at Davis

was instituted to discriminate against a particular sub

class of non-minorities, nor is there any claim that the

program had in fact such a differential impact.” 553

P.2d at 1183 n.10 (Pet. App. p. 61a n.10).

C. The Use of Racial Criteria by the State in Allo

cating Scarce Resources Is Constitutionally Per

missible Where Its Purpose and Effect Is to Over

come the Effects of Societal Discrimination.

Despite the fact that the Fourteenth Amendment itself

originated as a measure to promote integration and elimi

nate racial inequalities, Palmer V. Thompson, 403 U.S.

217, 220 (1971) ; id. at 240 (White, J., dissenting), the

majority below drew from the Equal Protection Clause a

rule which, as a practical matter, virtually forbids recog

nition of the special situation of minority applicants. As

the dissenting justice pointed out, the logic of the ma

jority’s position would preclude the medical school even

taking affirmative steps to recruit minority applicants,

553 P.2d at 1177-78 (Pet. App. p. 26a), a practice which

this Court approved in Washington v. Davis, supra, 426

U.S. at 246.

This result cannot be the command of the Fourteenth

Amendment. The pervasive effects of this nation’s sad

history of racial discrimination have received the wide

spread attention of courts and legislatures. In many con

texts drastic measures have proven necessary to eliminate

lingering discriminatory “systems and effects.” H. Rep.

No. 92-238, 92d Cong., 1st Sess. 8 (1972) (employment

discrimination). See also South Carolina v. Katzenbach,

383 U.S. 301, 327 (1966) (voting rights). And this Court

has authorized and even required race-conscious remedies

in a variety of corrective settings. See, e.g., United Jewish

Organizations of Williamsburgh, Inc. v. Carey, 97 S. Ct.

996 (1977) ; Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., 424

U.S. 747 (1976) ; Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenberg Board

19

of Education, 402 U.S, 1 (1971) ; United States V. Louisi

ana, 380 U.S. 145 (1965). Preferential treatment of

minority groups is recognized in many situations to be

the only effective means of overcoming persistent disad

vantages. E.g., Kahn v. Shevin, 416 U.S. 351 (1974)

(widows benefits) ; Lau v. Nichols, 414 U.S. 563 (1974)

(remedial education) ; 24 C.F.R. § 200.600 (housing) ;

E. O. 11246, pt. II, 3 C.F.R., 1964-1965 Comp. 339, as

amended by E. O. 11375, 3 C.F.R., 1966-1970 Comp. 684

(employment of minorities by federal contractors). See

also Morton v. Mancari, 417 U.S. 535 (1974) (employ

ment of reservation Indians in the Bureau of Indian

Affairs).

There is no reason, constitutional or otherwise, that

the University should first have to be adjudged guilty of

discrimination before being permitted voluntarily to take

steps toward overcoming the lingering effects of societal

discrimination: “the permissible use of racial criteria is

not confined to eliminating the effects of past discrimina

tory districting or apportionment.” United Jewish Or

ganizations v. Carey, 97 S. Ct. at 1007. This Court has

approved voluntary efforts to remedy segregation in

schools, in cases where such efforts could not be judicially

compelled. See, e.g., Swann V. Charlotte-Mecklenberg

Board of Education, 402 U.S. 1, 16 (1971); Nyquist V.

Lee, 402 U.S. 935 (1971), a fg 318 F. Supp. 710

(W.D.N.Y. 1970).

In other cases this Court has recognized the con

stitutional propriety of preferential treatment for groups

which have been the subject of general societal discrimin

ation, most recently in Califano v. Goldfarb, 97 S. Ct.

1021, 1028 n.8 (1977), and Califano v. Webster, 97 S. Ct.

1192 (1977) (per curiam). And there is no suggestion

in any of these cases that an adjudication of fault must

accompany every contribution to overcoming entrenched

patterns of discrimination and segregation. While the

culpability of an employer or school admissions committee

20

may well affect the equity of judicial imposition of pref

erential relief, there can be no constitutional or indeed

rational basis for distinguishing between culpable and

nonculpable defendants when the issue is the permissi

bility of their voluntary remedial acts.5

D. The Fact That the Special Admissions Program

May Impose Some Disadvantage on Individual

Members of Groups Not Directly Benefitted by

the Program Is Not Sufficient to Make the Pro

gram Invalid.

The majority below distinguished those cases in which

this Court has upheld the preferential use of racial

criteria on the grounds that such preferences had not

deprived nonminorities of “benefits which they would

otherwise have enjoyed.” 553 P.2d at 1160 (Pet.App.

p. 13a). While stating that school desegregation decisions

may “discommode” nonminorities “by requiring some to

attend schools in neighborhoods other than their own,” the

court found it constitutionally significant that the ra

cial classifications in those cases did not “totally deprive”

any child of an education and subjected members of all

races to essentially equivalent treatment. Id.

It is clear that the effect of the special admissions pro

gram is to impose costs on some individuals who do not

5 Various lower courts have upheld employment quotas pursuant

to federal contracting requirements without any demonstration

that the affected employer had previously engaged in discrimina

tory practices. E.g., Associated General Contractors of Mass., Inc.

V. Altshuler, 490 F.2d 9 (1st Cir. 1973), cert, denied, 416 U.S. 957

(1974); Southern Illinois Builders Ass’n V. Ogilvie, 471 F.2d 680

(7th Cir. 1972); Contractors Ass’n of Eastern Pa. v. Secretary of

Labor, 442 F.2d 159 (3d Cir.), cert, denied, 404 U.S. 854 (1971).

Similarly, voluntary adoption of preferential programs was sanc

tioned in Porcelli v. Titus, 431 F.2d 1254 (3d Cir. 1970).

21

meet the racial criteria used. It is less clear why those

costs appeared to the court below to overstep a constitu

tional line. This Court recently held that detrimental ef

fects upon the expectations of nonminority employees did

not render invalid an order for remedial assignment of

seniority benefits to minority employees. Franks v. Bow

man Transportation Co., 424 U.S. 747, 775-77 (1976).

It is in the very nature of the problem of allocating

scarce public resources that all will not be fully served and

some will be denied access entirely. If the use of racial

criteria is not per se unconstitutional, the determination

of the University as to the criteria for allocating places

in its medical school must be given considerable deference.

In designing and implementing its remedial program, the

University was aware of the need to balance its strong

interests in increasing minority enrollment against pos

sible intrusion on the expectations of others. In so doing,

it was entitled to “ ‘look to the practical realities and

necessities inescapably involved in reconciling competing

interests,’ in order to determine the ‘special blend of what

is necessary, what is fair, and what is workable.’ ” Team

sters v. United States, 45 U.S.L.W. 4506, 4519 (May 31,

1977), quoting from Lemon v. Kurtzman, 411 U.S. 192,

201, 200 (opinion of Burger, C. J.). And it is important

to point out that while the court below characterized the

cost to the plaintiff as an “absolute denial,” 553 P.2d at

1161 (Pet. App. p. 14a), he was in fact, like all other ap

plicants, fairly considered for admission to medical school

by the school’s own standards. As we have argued, that

those standards include consideration of an applicant’s

race is, under these circumstances, permissible; the fact

that this results in fewer places being available for the

nonpreferred majority does not work an injury of consti

tutional dimension to the aspirations of that class, or of

any member of it.

22

III. The Details of the Specific Special Admissions Program

Adopted by Davis Do Not Make I t Constitutionally

Objectionable.

We have demonstrated that the type of special ad

missions program adopted by Davis is necessary to ac

complish important state and national objectives and is

constitutionally valid. Nor is there anything about the

details of the specific program that should change this

result. As this Court has repeatedly recognized, public

school authorities must be afforded wide discretion in

determining and enforcing the standards governing the

academic processes. See, e.g., Epperson v. Arkansas, 393

U.S. 97, 104 (1968). The importance of the interests

served by such programs as that challenged in this case

requires that they not be made subject to the constant

threat of federal litigation. Otherwise, it is predictable

that they will not be adopted at all, in any form, by most

professional schools, and the result will be further frus

tration and delay in realizing “the promise of Brown.”

See North Carolina State Board of Education v. Swann,

402 U.S. 43, 46 (1971).

A. The Existence of a Separate Admissions Track

Does Not Invalidate the Program.

The existence of a separate admissions committee to

screen and evaluate candidates for special admission

serves valid administrative purposes and does not reflect

adversely on the overall validity of the special admis

sions program. The program is designed to benefit mi

norities who have suffered most, both economically and

educationally, from past discrimination, and is narrowly

drawn to assist that class alone. Cf. Kahn v. Shevin, 416

U.S. 351, 360 (1974) (Brennan, J., dissenting). Indeed,

minority applicants with no history of disadvantage are

referred to the regular admissions program. R. 65-66,

23

170.° In any event, final selection of special admissions

applicants, like applicants in the regular admissions pro

cess, is made by the full admissions committee. R. 166.

The only difference in the procedure employed by the two

committees is that, in selecting candidates to be inter

viewed, the special admissions committee does not employ

an arbitrary grade point average cut-off figure. R. 175.

The court below conceded that

“we are aware of no rule of law which requires the

University to afford determinative weight in admis

sions to these quantitative factors. In practice, col

leges and universities generally consider matters

other than strict numerical ranking in admission de

cisions. (O’Neil, Preferential Admissions (1971) 80

Yale L.J. 699, 701-705). The University is entitled

to consider, as it does with respect to applicants in

the special program, that low grades and test scores

may not accurately reflect the abilities of some dis

advantaged students; and it may reasonably conclude

that although their academic scores are lower, their

potential for success in the school and the profession

is equal to or greater than that of an applicant with

higher grades who has not been similarly handi

capped.” 553 P.2d at 1166 (Pet. App. p. 24a).

These are, in fact, precisely the considerations which

informed the judgment of the University and its officials

in establishing and administering the special admissions

program in this case. To hold that the University is

constitutionally disabled from applying a different meas

ure of qualification to individuals whose backgrounds

suggest a less dependable applicability of the usual stand

ards, is effectively to constitutionalize the notion of merit

embodied in standardized tests like the MCAT.

6 “R.” references are to the pages of the clerk’s transcript of the

record filed in the court below.

24

B. The Use of Numerical Goals for Minority Admis

sions Does Not Invalidate the Program.

The decisions of this Court and of the lower federal

courts leave little doubt that numerical goals of them

selves are not constitutionally infirm. In Title VII cases,

the circuit courts have been virtually unanimous in “re

quirting] employers to hire according to ratios of mi

nority to white employees” in order to redress the effects

of past discrimination. See Edwards & Zaretsky, Prefer

ential Remedies for Employment Discrimination, 74

Mich. L. Rev. 1, 9 and nn. 41-44 (1975) (citing cases).

In the school desegregation cases, this Court similarly

has sanctioned the use of “ ‘fixed mathematical’ ratios.”

United States v. Montgomery Board of Education, 395

U.S. 225, 234, 235-36 (1969). It has sanctioned their

use, moreover, not only in remedial judicial orders, but

in voluntary administrative programs. In Swann v. Char-

lotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, 402 U.S. 1 (1971),

this Court acknowledged the validity of a discretionary

judgment by school authorities that “in order to prepare

students to live in a pluralistic society each school should

have a prescribed ratio of Negro to white students re

flecting the proportion for the district as a whole.” Id.

at 16. And in United Jewish Organizations of Williams-

burgh, Inc. v. Carey, 97 S. Ct. 996 (1977), this Court re

cently upheld the use of “specific numerical quotas” to

establish a fixed number of black majority voting dis

tricts. Id. at 1008.

The use of numerical guidelines, secondly, is peculiarly

innocuous in the case at bar. The University’s targeted

percentages are flexible: they have varied between

8%, 12%, and 16% in the six years the program has

operated. There is no suggestion that the University’s

goals set a ceiling on minority enrollment. Indeed, the

16% goal applies only to disadvantaged minority ap

plicants: the court below noted that six Mexican Ameri-

25

cans, one black and 41 Asians were admitted between

1971 and 1974 through the regular admissions program.

553 P.2d at 1165 n.21. Nor does the 16% goal represent

a mandatory requirement which must be filled regardless

of qualifications. In at least one of the years under con

sideration, only 15 minorities were admitted under the

special admissions program. R. 216-18.

Perhaps more fundamentally, numerical goals are nec

essarily implicated in any racially preferential program.

See United Jewish Organizations of Williamsburgh, Inc.

v. Carey, 97 S. Ct. 996, 1008 (1977). Once it is decided

that minorities should be preferred, the magnitude of that

preference must be gauged. Once it is decided that minor

ities are underrepresented, the size of that underrepre

sentation must be assessed. Once it is decided that minor

ities’ test scores should be discounted, the magnitude of

that discount must be determined. “In deciding how many

bonus points to give,” in short, “there is no escape from

setting some goal for the number of minority students in

the entering class.” Karst & Horowitz, Affirmative Action

and Equal Protection, 60 Va. L. Rev. 955, 971 (1974). To

permit racially preferential admissions programs, and to

acknowledge that officials administering them inevitably

must entertain notions as to their proper goals, but

to forbid those officials, on constitutional grounds, to make

these goals plain for all to see, is to encourage nothing

healthy in the law. Here, as before, the question re

duces to one of disingenuousness. Here, as elsewhere,

disingenousness is to be avoided.

26

CONCLUSION

Wherefore we respectfully submit that the decision and

judgment of the Supreme Court of California should

be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

Albert E. J enner , J r.

Stephen J. P ollak

Co-Chairmen

Burke Marshall

N orman Redlich

Owen M. F iss

Trustees

Robert A. Murphy

Susan P erry

W illiam E. Caldwell

Staff Attorneys

Lawyers’ Committee for

Civil Rights Under Law

733 - 15th St., N.W.

Suite 520

Washington, D.C. 20005

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae*

* Amicus Curiae expresses its appreciation to Margaret Colgate

Love, a recent graduate of Yale Law School and current associate

with Shea & Gardner, Washington, D.C., for her valuable contri

butions to this brief.