Memorandum in Support of Emergency Motion for Stay or Suspension of Proceedings

Public Court Documents

July 11, 1972

53 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Milliken Hardbacks. Memorandum in Support of Emergency Motion for Stay or Suspension of Proceedings, 1972. 85c2d562-53e9-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/bed03f78-efd0-4357-bfcf-7142378c3523/memorandum-in-support-of-emergency-motion-for-stay-or-suspension-of-proceedings. Accessed February 27, 2026.

Copied!

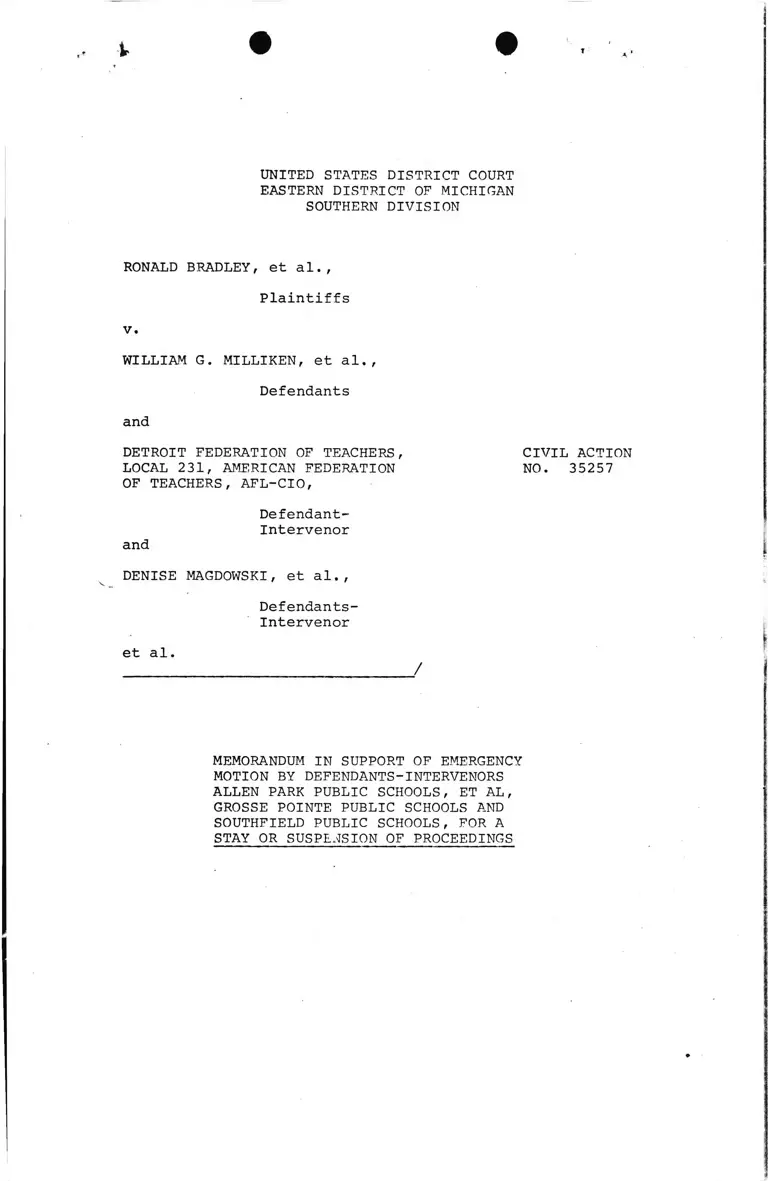

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

EASTERN DISTRICT OF MICHIGAN

SOUTHERN DIVISION

RONALD BRADLEY, et al.,

Plaintiffs

v.

WILLIAM G. MILLIKEN, et al.,

Defendants

and

DETROIT FEDERATION OF TEACHERS, CIVIL ACTION

LOCAL 231, AMERICAN FEDERATION NO. 35257

OF TEACHERS, AFL-CIO,

Defendant-

Intervenor

and

DENISE MAGDOWSKI, et al.,

Defendants-

Intervenor

et al.

______________________________________ /

MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT OF EMERGENCY

MOTION BY DEFENDANTS-INTERVENORS

ALLEN PARK PUBLIC SCHOOLS, ET AL,

GROSSE POINTE PUBLIC SCHOOLS AMD

SOUTHFIELD PUBLIC SCHOOLS, FOR A

STAY OR SUSPENSION OF PROCEEDINGS

UNITED STATER DISTRICT COURT

EASTERN DISTRICT OF MICHIGAN

SOUTHERN DIVISION

RONALD BRADLEY, et al.,

Plaintiffs

v.

WILLIAM G. MILLIKEN, et al.,

Defendants

and

DETROIT FEDERATION OF TEACHERS, CIVIL ACTION

LOCAL 231, AMERICAN FEDERATION NO. 35257

OF TEACHERS, AFL-CIO,

Defendant-

Intervenor

and

DENISE MAGDOWSKI, et al.,

Defendants-

Intervenor

et al.

/

MEMORANDUM IN SUPPORT OF EMERGENCY

MOTION BY DEFENDANTS-INTERVENORS

ALLEN PARK PUBLIC SCHOOLS, ET AL,

GROSSE POINTE PUBLIC SCHOOLS AND

SOUTHFIELD PUBLIC SCHOOLS, FOR A

STAY OR SUSPENSION OF PROCEEDINGS

A

INTRODUCTION

On September 27, 1971, this Court issued a "Ruling On

Issue of Segregation" holding that illegal segregation exists

in the public schools of the City of Detroit. Subsequently,

on June 14, 1972, the Court handed down its "Ruling On De

segregation Area and Order for Development of Plan of Dese

gregation, together with Findings of Fact and Conclusions

of Law in support thereof. The Court has thus determined

that de jure segregation exists in the Detroit public school

system and that said situation must be remedied by imple

mentation of a so-called metropolitan plan of desegregation.

The rulings and orders issued by the Court to date terminate

litigation on the issue of de_ jure segregation and the matter

of a metropolitan plan of desegregation. Nothing remains

to be done except to enforce by execution what has been deter

mined by the Court.

The Order for Development of Plan of Desegregation com

mands the Intervening School Districts to assist, at their

own expense, in the detailed implementation of the Court-

ordered metropolitan desegregation and in this regard is,

in effect, a mandatory injunction.

On June 20, 1972 Newly Intervening School Districts

appealed this order to the United States Court of Appeals

for the 6th Circuit. Since that time the Board of Education

for the City of Detroit and the Defendants-Intervenors Kerry

Green, et al have likewise filed appeals with the 6th Circuit.

Defendants-Intervenors now move this Court for an Order

staying implementation of its June 14, 1972 order, pending

appeal, and in support of said motion submit this Memorandum.

B

THERE IS NO CONTROLLING JUDICIAL

PRECEDENT FOR A METROPOLITAN

PLAN OF DESEGREGATION UNDER THE

CIRCUMSTANCES EXTANT IN THIS CASE

In its "Ruling on Propriety of Considering A Metropolitan

Remedy to Accomplish Desegregation of the Public Schools of

the City of Detroit", and in the course of hearing on July

10, 1972, the Court candidly acknowledged that the issue of

whether a metropolitan plan of desegregation is legally proper

has not been passed upon by the United States Supreme Court.

In the context of this case, such issue may be stated as

follows:

2

Where a single school district has been found

to have committed acts of de_ jure segregation, may

a court constitutionallv issue ^desegregation order

extending to fiftv-three (53) other independent school

districts and requiring massive bussing of children,

absent (i) any claim or finding that such other inde

pendent school districts have deliberately operated

in furtherance of a policy to deny access to or sepa

rate pupils in schools on the basis of race, or, (ii)

absent anv claim or finding that the boundary lines

of such other independent school districts were created

or have been maintained with the purpose of creating

or fostering a dual school svstem?

The trial court answered "YES".

The Newlv Intervening School Districts

contend the answer should be "NO".

The existence of a new or novel question has frequently

been assigned as the basis for granting a stav order by

the United States Supreme Court. Just last Fall in a school

desegregation case Mr. Justice Black reinstated a stay of

a district court order which had been vacated bv the United

States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit because of

the existence of previously undecided questions. The decision

holds:

"It is apparent that this case is in an undesirable

state of confusion and presents questions not hereto

fore passed on bv the full Court, but which should

be. Under these circumstances, which present a very

anomalous, new and confusing situation, I decline as

a single Justice to upset the District Court's stav

and, therefore, I reinstate it . . . Corpus Christi

School District v Cisneros, ____ F Supp _____ (1971)

application for reinstatement of stay granted, 404

US 1211 (1971).

A new or novel question of law has also been recognized

as adequate reason for a stay in the following cases: Guey

Heung Lee v Johnson 404 US 1215; American Manufacturers

Mutual Insurance Company v American Broadcasting - Paramount

Theatres, Inc., 17 L Ed 37 (1966).

Intervening School Districts suggest that to implement

a plan affecting over 500,000 students, their parents and

teachers and to require the expenditure of millions of dollars

3

by already financially depressed state and local govern

mental authorities without granting a stav order pending

the prosecution of the several appeals taken by the various

parties would be a gross abuse of this Court's discretion.

C

THERE IS A SUBSTANTIAL PROBABILITY

THAT THIS COURT'S ORDER WILL BE

REVERSED BY AN APPELLATE COURT

There is an absolute dearth of controlling judicial

precedent to support the implementation of a metropolitan

plan of desegregation. Decisions rendered by appellate courts

in other school desegregation cases and traditional equity

principles clearly indicate a strong likelihood that this

Court's Order for a metropolitan plan of desegregation will

be reversed.

The case of Keyes v School District No.1, Denver, [1]

445 F2d 990 (CA 10, 1971) is very similar to the instant

case. In Keyes there was no evidence that the state had

fostered or maintained a dual education system. As a result

of population changes certain school attendance areas in

the older core area of the city, though at one time predomin

antly white, were by 1970 predominantly populated by Negroes

' and Hispanos. Other areas within the school district, referred

to as the Park Hill area, had also experienced a growth

in black population. .

In 1968 a comprehensive plan for desegregating the

Denver schools was presented to the Board. Before this

plan could be implemented, a school board election ensued

and two candidates who promised to rescind the plan were

elected and thereafter the Board did rescind the plan. The

Court found that by means of the manipulation of attendance

zones, the adoption of transfer policies and the selection

[1] Appeal pending,

U,S. Supreme Court. 4

of sites for the construction of new schools, all in the

Park Hill area, the Board had deviated from the traditional

neighborhood school plan and had pursued a policy calculated

to perpetuate racial isolation in the Park Hill area schools

in violation of the Fourteenth Amendment.

As to the older core area of the city, both the trial

court and the Court of Appeals held that the racial imbalance

was due to population changes and was not fostered or per

petuated by any action of the school authorities. The school

authorities had done nothing to change the racial imbalance

in said area. Both the trial court and the Court of Appeals

refused to hold that the inaction of the school authorities

violated the Fourteenth Amendment.

The trial court, however, held that even though the

existence of a significant racial imbalance in the older

core area schools did not permit a finding deprivation of

constitutional rights, the quality of education offered

in such schools was inferior to that being offered in other

Denver schools. The trial court then concluded that this

unequal educational opportunity offended the Fourteenth

Amendment and justified a desegregation remedy. The Court

of Appeals reversed the judgment of the trial court with

respect to the core area on the grounds that a firm founda

tion for constitutional deprivation cannot be located upon

the naked existence of racially imbalanced schools, saying:

". . . . It is well recognized that the law in

this Circuit is that a neighborhood school policy is

constitutionally acceptable, even though it results

in racially concentrated schools, provided the plan

is not used as a veil to further perpetuate racial

discrimination. . . . " Keyes v School District No.1,

Denver, 445 F2d 990 at 1004 (CA 10, 1971).

5

This Court placed strong reliance on the case of Bradley

v School Board of the City of Richmond, 338 F Supp 67 (1972) ,

reversed _____ F2d _____ (June 5, 1972) , in support of its

assumption of authority to order a metropolitan plan of

desegregation (Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law On

Detroit-Only Plans of Desegregation, March 28, 1972). The

District Court's order in Bradley v Richmond, supra, pairing

three school districts for the ostensible purpose of effect

ing desegregation in the Richmond school district was reversed

by the Courth Circuit Court of Appeals sitting en banc,

Bradley v School Board of the City of Richmond, _____ F2d

_____ (CA 4, June 5, 1972).

This Court has stated that for want of a direct ruling

on the issue as to the appropriateness of a metropolitan

plan of desegregation by the United States Supreme Court it

could' only proceed by "feeling" its way through past decisions

of the Supreme Court. (Ruling on Propriety of Considering

A Metropolitan Remedy to Accomplish Desegregation of the

Public Schools of the City of Detroit.) In so doing, the

Court has, to all outward appearances, completely ignored

the very recent affirmance of the decision of the three

judge court in Spencer v Kugler, 326 F Supp 1235 (1971),

aff'd. Mem. _____ US _____, 92 S Ct 707 (1972) which the

majority of the Fourth Circuit found to be controlling with

respect to the lack of authority of the District Court

to order a multi-school district plan of desegregation to

overcome a preponderance of black students within a single

school district.

Significantly, even the rationale of the lone dissenting

opinion in Bradley v Richmond, supra, would condemn the

ordering of a metropolitan desegregation plan .in this case

6

under the principle upheld in Spencer v Kugler, supra,

Circuit Judge Winter distinguished Spencer v Kugler, supra,

on the grounds that whereas Virginia had a long history of

a state-required dual system of schools, Spencer v Kugler,

supra, like the instant case, presented a situation where

there was no state history of a state-imposed dual system

of education, and no allegation that the school district

boundaries had been invidiously drawn.

The Order of this Court for a’metropolitan plan of

desegregation cannot be reconciled with the holdings of the

United States Supreme Court in Spencer v Kugler, supra,

and the Fourth Circuit in Bradley v Richmond, supra.

This Court has clearly predicated its Order for a

metropolitan plan of desegregation upon its desire to achieve

a viable racial mix vis-a-vis Detroit and surrounding com

munities. The intendment of the Court in this regard is

patently expressed in its "Ruling On Desegregation Area and

Order for Development of Plan of Desegregation", as follows:

"Within the limitations of reasonable travel time

and distance factors, pupil reassignments shall be

effected within the clusters described in Exhibit P.M..

12 so as to achieve the greatest degree of actual de

segregation to_ the end that, upon implementation,

no school, grade, or classroom by [be] substantially

disproportionate to the overall pupil racial composi

tion. " [Emphasis added.]

As a rose by any other name is still a rose, so racial mixing

couched in other terms remains racial mixing.

In Deal v Cincinnati Board of Education, 419 F2d 1387

(CA 6, 1969) , cert, denied 402 US 962 (1971) , the Sixth

Circuit Court of Appeals noted that the Constitution imposes

no duty to effect a racial balance, saying:

"It is the contention of appellants that the

Board owed them a duty to bus white and Negro children

away from the districts of their residence in order

that the racial complexion would be balanced in each

7

of the many public schools in Cincinnati. It is sub

mitted that the Constitution imposes no such duty.

Appellants are not the only children who have consti

tutional rights. There are Negro, as well as white,

children who may not want to be bussed away from the

school districts of their residences, and they have

just as much right to attend school in the area where

they live. They ought not to be forced against their

will to travel out of their neighborhoods in order

to mix the races." at p. 1390. [Emphasis added.]

This Court has indicated that it perceives the holding

of the U.S. Supreme Court in Brown v Board of Education

of Topeka, 346 US 483 (1954) to bestow virtually unlimited

remedial authority on the Court in the area of school de

segregation. Statements issued by the Supreme Court in

Swann v Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, 402 US

1 (1971) clearly indicate that such is not the case and

adumbrate an ultimate reversal of this Court's Order for

a metropolitan plan of desegregation.

". . . . However, a school desegregation case

d o e s not differ fundamentally from other Ccises in

volving the framing of equitable remedies to repair

the denial of a constitutional right. . . . " p. 16.

[Emphasis added.]

* * *

". . . . Remedial judicial authority does not

put judges automatically in the shoes of school auth

orities whose powers are plenary. Judicial authority

enters only when local authority defaults." p. 16.

* * *

"If we were to read the holding of the District

Court to require, as a matter of substantive consti

tutional right, any particular degree of racial balance

or mixing, that approach would be disapproved and we

would be obliged to reverse. The constitutional com

mand to desegregate schools does not mean that every

school in every community must always reflect the

racial composition of the school system as a whole."

p. 24. [Emphasis added].

The clear purpose of this Court's Findings of Fact

and Conclusions of Law on Detroit-Only Plans of Desegregation

and the Ruling on Desegregation Area and Order for Develop

ment of Plan of Desegregation, and the only purpose of the

8

cluster plans approved therein, is to obtain a racial balance

or mix in each school which reflects the racial composition

of the metropolitan area as a whole.

Intervening School Districts suggest that to require

massive outlays of money for implementation of the Court's

order and the disruption and transfer of tens of thousands

of students from one educational environment to another in

the absence of clear and controlling judicial precedent

would be a crippling blow to education in Michigan and would

be an extreme abuse of this Court's discretion.

D

THIS COURT MAY NOT HAVE JURISDICTION

TO IMPLEMENT A METROPOLITAN REMEDY

As a matter of jurisdiction, 28 USC 2281 provides

that:

"An interlocutory or permanent injunction re

straining the enforcement, operation or execution

of any State statute by restraining the action of

any officer of such State in the enforcement or exe

cution of such statute or of an order made by an ad

ministrative board or commission acting under State

statutes, shall not be granted by any district court

or judge thereof upon the ground of the unconstitu

tionality of such statute unless the application there

for is heard and determined by a district court of

three judges under section 2284 of this title."

This Court's "Ruling on Desegregation Area and Order

for Development of Plan of Desegregation," dated June 14,

1972, will effectively enjoin and restrain Intervening School

Districts from exercising the powers conferred upon them

by the Constitution and Statutes of the State of Michigan.

In particular, said Order will enjoin and restrain enforce

ment and operation of the following statutes:

1. MCLA §340.356, MSA 15.3356, "All persons, resi

dents of a school district not maintaining a kinder

garten, and at least 5 years of age on the first day

of enrollment of the school year, shall have an equal

right to attend school therein."

9

2. MCLA §340.583, MSA 15.3583, "Every board shall

establish and carry on such grades, schools and de

partments as it shall deem necessary or desirable for

the maintenance and improvement of the schools; deter

mine the courses of study to be pursued and cause

the pupils attending school in such district to be

taught in such schools or departments as it may deem

expedient. . . . "

3. MCLA §340.882, MSA 15.3882, "The board of each

district shall select and approve the textbooks to

be used by the pupils of the schools of its district

on the subjects taught thereon."

4. MCLA 340.589, MSA 15.3589, "Every board is auth

orized to establish attendance areas within the school

district."

5. MCLA §340.575, MSA 15.3575, "The Board of every

district shall determine the length of the school term.

II

• • •

In addition, said Order will prevent Intervening School

Districts from exercising those powers relating to employment

and assignment of teachers, construction of school buildings,

determination as to proper and necessary expenditures,

activities and standards of conduct for students, the training

and use of faculty and staff, and the conduct of extra

curricular activities in their respective school districts. [2]

The rationale behind 28 U.S.C. §2281 and its application

to this action are set forth in the following quotations

from Swift £ Co v Wickham, 382 US 111, 118 (1965):

[2] For illustrations of the future problems this Court will

face in connection with Michigan statutes, see Dr. Porter's

report to this Court dated June 29, 1972.

10

"The sponsor of the bill establishing the three-

judge procedure for these cases, Senator Overman of

North Carolina, noted:

1[T]here are 150 cases of this kind now where

one federal judge has tied the hands of the state

officers, the governor, and the attorney-general.

* * * * *

'whenever one judge stands up in a state and

enjoins the governor and the attorney-general,

the people resent it, and public sentiment is

stirred, as it was in my state, when there was

almost a rebellion, whereas if three judges de

clare that a state statute is unconstitutional

the people would rest easy under it.'"

"Section 2281 was designed to provide a more responsible

forum for the litigation of suits which, if successful,

would render void state statutes embodying important

state policies. . . . It provides for three judges,

one of whom must be a circuit judge. . . . to allow .

a more authoritative determination and less opportunity

for individual predilection in sensitive and politically

emotional areas. It authorizes direct review by this

Court, . . ., as a means of accelerating a final deter

mination on the merits; an important criticism of the

, pre-1910 procedure was directed to appeal through the

circuit courts to the Supreme Court, and the consequent

disruption of state tax and regulatory programs caused

by the outstanding injunction." 382 US 111, 119-120.

Intervening School Districts have previously raised

the question as to whether a three judge court should have

been impaneled and this Court made no response thereto.

This question must also be determined by an appellate court

and it is submitted that sound exercise of judicial dis

cretion mandates that this Court stay its Order of June

14, 1972, pending determination as to its jurisdiction

to effectively nullify the operation of State laws of general

application.

E

THERE IS RECENT PRECEDENT FOR A STAY

ORDER IN THIS CASE

As recently as June 2, 1972, the United States Court

of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit, in Northcross v Board

11

of Education of City of Memphis, 312 F Supp 1150 (WD Tenn,

1970), order Misc. 1576, June 2, 1972, granted a motion

for a stay of a district court order in a school desegregation

case of far less impact than the instant case. The Northcross

case was relied upon by this Court in its "Ruling On Issue

Of Segregation" and its "Findings of Fact and Conclusions

of Law in Support of Ruling on Desegregation Area and Develop

ment of Plans."

Likewise, the case of Davis v School District of the

City of Pontiac Inc, 309 F Supp 734 (ED Mich, 1970) , aff'd

443 F2d 573 (CA 6, 1971), relied on by this Court in its

September 27, 1971 and June 14, 1972 orders, was stayed

by the Sixth Circuit pending decision by the appellate court.

Bradley v School Board of the City of Richmond, 338

F Supp 67 (ED Va, 1972), reversed ____ F2d ____ (CA 4, June

4, 1972), perhaps the most important, if not the only authority

for this Court's far reaching remedy, was stayed by the

Fourth Circuit pending their decision.

Considering the incredible scope of this Court's remedy,

the admission by this Court that the issue as to the pro

priety of a metropolitan remedy under the circumstances here

present has not yet been passed on by the United States

Supreme Court, the likelihood of reversal by an appellate

court, and the granting of stays in cases of substantially

lesser affect, Intervening School Districts submit that

this Court should stay implementation of its Order.

F

PRACTICAL CONSIDERATIONS

Implementation of the Court's Order of June 14, 1972,

by the opening of school this September would be so dis

ruptive and strident that it could well defeat the ultimate

12

objective sought to be attained. We are less than sixty

(60) days away from the start of school for the 1972-1973

school year. At the present time there is no intelligible

plan developed for Fall 1972 implementation and after sub

mission of such a plan by the Panel the Court contemplates

further hearings thereon.

Budgeting and other plans for the operation of the

schools for the coming school year have been finalized.

Curriculum, norms and cognitive styles have been established

to accommodate presently enrolled students.

Many school districts employ "continuous progress"

programs wherein the student progresses at his own rate of

achievement, sometimes on a non-graded basis, and frequently

in groups based upon ability and performance. The Court's

- prohibition (paragraph 82 of Findings and Conclusions of

Law issued June 14, 1972) against such "tracking" or group

ing precludes and/or restricts such programs.

The scant time available before the start of school

this September does not permit intelligent modifications

or substitution of present learning programs to accommodate

the varying educational needs of students who would be

summarily infused into new school systems.

As noted in the course of hearings on a metropolitan

plan, a substantial majority of elementary schools do not

have suitable facilities to provide children with at-school

lunches. From the testimony adduced during the course of

hearing there is no conceivable way that such facilities

could be provided prior to the Fall of this year.

It is assumed that the requirements delineated by the

Court in connection with its Order for a metropolitan plan

of desegregation are deemed necessary to the satisfactory

13

effectuation of such a plan. To expect the following to

be accomplished within less than 60 days among fifty-three

(53) school districts is incredible:

(1) Reassignment of faculty and staff by quali

fications for subject and grade level, race, experience

and sex.

(2) Assignment of bi-racial administrative teams.

(3) Restructuring of school facility utilization

necessitated by pupil reassignments so as to produce

schools of substantially like quality, facilities,

extra-curricular activities and staffs.

(4) Establishment of curriculum, activities and

conduct standards which respect the diversity of students

from differing ethnic backgrounds and the dignity and

safety of each individual, students, faculty, staff

and parents.

(5) Expansion of in-service training programs

to insure effective desegregation of the schools.

Teachers unfamiliar with the learning programs at

various school districts cannot be expected to effectively

implement them. Super-charged and last minute in-service

training to prepare a teacher for a new and different edu

cational environment is clearly inadequate and will pre

dictably result in deterioration of educational programs

and confusion to students and teachers alike.

The Order of the Court requires that student codes

must be re-evaluated and reflect the diversity of ethnic

and cultural backgrounds of the children now in the schools

(Findings and Conclusions issued June 14, 1972, paragraph

82 b). Time simply does not permit a meaningful study of

black community customs and the establishment of an effective

14

dialect to assure implementation of bi-racial codes of

conduct. Misguided or ineffectual efforts in these areas

could exacerbate what may now remain of racial bias and

prejudice.

The Court's statement that the burden is upon the State

Defendants to show affirmatively that a metropolitan plan

of desegregation cannot be implemented within less than

sixty (60) days is incredulous. There is no experience

upon which the feasibility of such an undertaking can be

measured. In short, the Court is saying that the State

Defendants must show they cannot do something which has

never been done before. This is like telling a 75 year

old man who has never run a mile in three (3) minutes that

he must prove he cannot accomplish such feat. The only

proof lies in attempt and failure. An attempt to implement

an educationally effective plan of metropolitan desegregation

which fails will prove its unworkability but will also do

serious harm to thousands of children and the educational

system as a whole.

In Alexander v Holmes County Board of Education, 396

US 19 (1969) the U.S. Supreme Court stated that the obliga

tion to terminate dual school systems at once and to operate

only unitary schools requires lower courts not to suspend

efforts to disestablish dual school systems pending appeals.

The Supreme Court decreed that such mandate requires the

operation of "unitary school systems within which no person

is to be effectively excluded from any school because of

race or color" (Alexander v Holmes, supra, at p. 20). This

case is not an Alexander case, however, and is not controlled

by the principle therein enunciated. Here there is no claim,

no evidence and no finding that any of the school districts

except Detroit have failed to operate a unitary school system.

15

To undertake the implementation of a metropolitan

plan of desegregation, even on a limited and interim basis,

in the admitted absence of controlling judicial precedent

and with the likelihood of reversal poses a genuine poss

ibility of having to "undo" the many changes necessary

to such undertaking. Prudence dictates that thousands of

children should not be uprooted from a new stable and familiar

educational environment until this Court's Order of June 14,

1972, has passed appellate review. To attempt hurried and

hastily conceived implementation within a span of a few

weeks would be folly and will serve only to impede the

mission of all school districts — to provide children

with a quality education.

G

A STAY OF PROCEEDINGS SHOULD BE

ORDERED ON THE BASIS OF SECTION

803 OF THE "EDUCATION AMEND

________MENTS OF 19 72"_________

I

INTRODUCTION

On June 23, 1972, the President of the United States

signed into law the "Education Amendments of 1972". This

comprehensive legislation became effective on July 1, 1972.

One provision, Section 803, was added during debates in

the House of Representatives as a non-germane Amendment,

and relates to the question of a stay or suspension of pro

ceedings by this Court at this time. Section 803 provides

as follows:

"Sec. 803. Notwithstanding any other law or provision

of law, in the case of any order on the part of any

United States district court which requires the transfer

or transportation of any student or students from any

school attendance area prescribed by competent State

16

or local authority for the purposes of achieving a bal

ance among students with respect to race, sex, religion,

or socioeconomic status, the effectiveness of such

order shall be postponed until all appeals in connection

with such order have been exhausted or, in the event

no appeals are taken, until the time for such appeals

has expired. This section shall expire at midnight

on January 1, 1974."

As a result of this legislation, it is submitted that

the Ruling on Desegregation Area and Order for Development

of Plan of Desegregation, entered by this Court on June

14, 1972, and particularly those provisions relating to

the transfer and transportation of students within the desegrega- -

tion area, is ineffective until all appeals from that ruling

have been exhausted.

Section I B. of the Court's Order of June 14, 1972

provides, in part, as follows:

" . . . the panel is to develop a plan for the assignment

of pupils . . . and shall develop as well a plan for

the transportation of pupils, for implementation for

all grades, schools and clusters in the desegregation

area......... the panel may recommend immediate imple

mentation of an interim desegregation plan for grades

K-6, K-8 or K-9 in all or in as many clusters as prac

ticable, with complete and final desegregation to proceed

no later than the fall 1973 term."

Section II A. of the Court's Order of June 14, 1972,

in part, provides:

"Pupil reassignment to accomplish desegregation of

the Detroit public schools is required within the geo

graphical area . . . referred to as the 'desegrega

tion area'."

Section II B. of the Court's Order of June 14, 1972,

in part, provides:

" . . . pupil reassignments shall be effected within

the clusters described in Exhibit P.M.12 so as to achieve

the greatest degree of actual desegregation to the

end that, upon implementation, no school, grade or

classroom be substantially disproportionate to the

overall pupil racial composition."

17

Section II E. of said Order provides, in part, as follows:

"Transportation and pupil assignment shall . . . be

a two way process with both black and white pupils

sharing the responsibility for transportation require

ments at all grade levels." .

Finally, Section II I. of the Court's Order provides,

in part:

"The State Board of Education and the State Superintendent

of Education shall with respect to all school construction ,

and expansion, ' consider tĥ s factor of racial balance

along with other educational considerations in making

decisions about new school sites, expansion of present

facilities * * *',"

The particular students to be transferred and trans

ported from one attendance area, prescribed by their local

school district, to another attendance area, prescribed

■

by this Court, have not been identified and the exact date

when such transfer and transportation shall occur has like

wise not been determined by the June 14 Order of this Court.

It is perfectly clear, however, as indicated by the above

referred to provisions of said Order, that:

1. Transfer of students has been ordered (Sec

tion IB., II A. and II E.).

2. The transfers have been ordered for the pur

pose of achieving a balance with respect to race. (Section

II B. and II I.).

That the Order of the Court dated June 14, 1972 constitutes

an order "which require[s] the transfer or transportation"

of students within the meaning of Section 803 is unquestion

able in view of the above quoted provisions and the clear

18

language and legislative history of Section 803. The Order

of this Court from the bench on July 10, 1972, directing

the purchase of 295 buses, makes this all the more clear.

Congress has mandated postponement of the effectiveness

of this type of order during the pendency of appeals and

it is submitted that this Court should therefore suspend

the effectiveness of its Order until appeals are resolved

in this cause.

In the event it should be determined that the Order

of June 14, 1972 does not, by its own terms, actually require

the transfer or transportation of students and is therefore

not at this moment subject to the provisions of Section

803 declaring such an Order to be ineffective, it is submitted

that the practical effect of Section 803 is to make it incumbent

upon this Court to grant an equitable stay of proceedings

at this time. If it is ruled that as a prerequisite to the

application of Section 803, the Court enter a further Order

in pursuance of the Desegregation Panel's recommendations

particularizing the students and schools involved in the pupil

assignments and pupil transportation, they will themselves

be ineffective thus rendering, for all intents and purposes,

the Orders of June 14 and July 10 ineffective. Accordingly,

this Court should enter an Order staying proceedings now,

at least insofar as the Court's prior Orders may contemplate

the entry of further Orders assigning and transporting stu

dents prior to the exhaustion of appeals in order to carry

19

out the manifest intent of Congress that massive expense

and hardship not occur until the legal rights of the parties

have been finally determined.

Both prior and subsequent to the signing of the "Educa

tion Amendments of 1972" by the President of the United

States, there was and continues to be considerable speculation

as to the effectiveness of Section 803 and the applicability

thereof to the instant case. Such speculation, often poli

tically motivated, should have no affect on the construction

to be afforded Section 803; such question being subject

only to judicial determination. Accordingly, the following

is a discussion of several of the principal issues which

might be raised with respect to this unique action by the

Congress of the United States. Intervening School Districts

contend that the significant pre-enactment material, and

cases, discussed below, compel the conclusion that Section

803 must ultimately suspend the effectiveness of any order

transferring students issued by this Court, and therefore

dictates that a Stay of Proceedings be instituted now, so

that all appeals may be exhausted before the implementation

of relief in this cause is further continued.

. II

CONSTITUTIONAL VALIDITY OF SECTION 803

The Intervening School Districts anticipate that argu

ment will be made that Section 803 is an unconstitutional

attempt by the United States Congress to limit the jurisdiction

20

of the United States district courts to implement their

orders while appellate procedures are being exhausted. The

simple answer to this anticipated argument is found in Section

1 of Article III of the United States Constitution, which

sets forth the power of Congress to govern the jurisdiction

of the lower federal courts. This Section provides as follows

"Sec. 1. The judicial Power of the United States, shall

be vested in one supreme Court, and in such inferior

Courts as the Congress may from time to time ordain

and establish."

The breadth of authority of Congress over the juris

diction of the federal courts of the United States was dra

matically illustrated in the 1868 case of Ex parte McCardle,

7 Wall. 506, 19 L Ed 264 (1868). There, a civilian held

for trial by a military commission was denied a Writ of

Habeas Corpus by the circuit court. While an appeal from

this denial was pending before the Supreme Court of the

United States, Congress passed a statute taking away the

appellate jurisdiction of the Supreme Court in habeas corpus

cases. The Supreme Court held that this was a legitimate

exercise of congressional power and that the legislation

deprived the United States Supreme Court of jurisdiction

even though the Act was passed after the Supreme Court had

already taken jurisdiction of the case. This was so even

though the cause before the Court involved an alleged viola

tion of the plaintiff's constitutional rights.

Although the invoking of the appellate procedures from

the decision of a lower federal court does not, as a general

rule, operate to effect an automatic stay of proceedings

this has not always been the case. As discussed in the

case of Brockett v Brockett, 2 How 238, 11 L Ed 251 (1844)

and the SlaughterHouse cases, 10 Wall 273, 19 L Ed 915 (1869),

21

the Judiciary Act of 1789 provided that the filing of a Writ

of Error within ten days from the date of entry of the

order of the court below operated as an automatic supersedeas

and stay of execution under Section 23 of the Judiciary

Act. No case could be found challenging the validity of

this automatic stay provision of the Judiciary Act of 1789.

In more recent times, the question of congressionally

imposed limitations on the jurisdiction of the lower federal

courts has been discussed in a number of cases arising

in several different contexts:

A. LABOR

Although the Congress of the United States may not

circumscribe the original jurisdiction of the Supreme Court,

it may limit or even remove the general jurisdiction of

the lower federal courts. This power is illustrated in

the case of Lauf v E.G. Shinner _& Co, 303 US 323, 82 L Ed

872 (1938) , involving the construction of certain provisions

of the Norris-LaGuardia Act. That Act provided that "no

court of the United States shall have jurisdiction to issue

a temporary or permanent injunction in any case involving

or growing out of a labor dispute" unless certain very specific

findings were made by the court, involving substantial and

irreparable injury in balancing the interests of the parties.

In the Lauf case, the United States Supreme Court in uphold

ing this provision, stated simply, at page 330,

"There can be no question of the power of Congress

thus to define and limit the jurisdiction of the in

ferior courts of the United States."

B. VOTING RIGHTS

The question of Congress' power over the lower federal

courts arose in another context, involving the elimination

of the jurisdiction of the district court to entertain

22

certain matters arising under the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

In referring to that provision of the Act which requires

states to seek certain relief only in one district court

in the United States, the Supreme Court of the United States,

in South Carolina v Katzenbach, 383 US 301, 15 L Ed 2d 769

(1966) stated, at page 331:

"Despite South Carolina's argument to the contrary,

Congress might appropriately limit litigation under

this provision to a single court in the District of

Columbia, pursuant to its constitutional power under

Art. Ill, §1, to 'ordain and establish' inferior federal

tribunals."

C. SELECTIVE SERVICE

The limited nature of the jurisdiction of the inferior

federal courts, as determined by the Congress, is further

illustrated in the selective service cases. In Falbo v

United States, 320 US 549, 88 L Ed 305 (1944), the Supreme

Court held that a selective service registrant could not

defend a prosecution on the ground that he was wrongfully

classified, where the offense was a failure to report for

induction. The court held that until the registrant had

exhausted all administrative appeals, the courts of the

United States had no jurisdiction to entertain his claim

that he had been improperly inducted. Following the Falbo

case, the United States Supreme Court ruled in Estep v United

States, 327 US 114, 90 L Ed 567 (1946), that in a case

where the registrant had exhausted all administrative appeals

before refusing to submit to induction, Congress had properly

limited the scope of the court's review to determining whether

or not the local draft board had acted beyond its jurisdic

tion. In speaking for three of the justices, Justice Douglas

stated at pages 122 and 123:

"The provision making the decisions of the local boards

'final' means to us that Congress chose not to give

administrative action under this Act the customary

23

scope of judicial review which obtains under other

statutes. It means that the courts are not to weigh

the evidence to determine whether the classification

made by the local boards was justified. The decisions

of the local boards made in conformity with the regu

lations are final even though they may be erroneous.

The question of jurisdiction of the local board is

reached only if there is no basis in fact for the

classification which it gave the registrant."

In a concurring opinion, Mr. Justice Rutledge stated

at page 132:

"I have no doubt that Congress could make administra

tive or executive actions final in such matters as

these in the sense of excluding all judicial review,

excepting only what may be required by the Constitution

in the absence of suspension of the writ of habeas

corpus."

In the case of Edwards v Selective Service Local Board,

111. 432 F 2d 287 (5th Cir. 1970), the subject of judicial

review of local draft board classifications again came up

for review. In that case, involving a registrant who sought

to enjoin his induction into the armed forces, the court

held that judicial review of registrant's classification

was barred by Congressional mandate. In its opinion, the

5th Circuit Court of Appeals stated at page 290:

"This Court and the court whose order we review are

each and both inferior courts of limited jurisdiction.

The route of our reasoning properly starts with the

presumption that we lack subject matter jurisdiction

until it has been demonstrated to exist. This has

long been the basic tenent of federal jurisprudence,

(citations omitted). The power to ordain and establish

these courts is vested in the Congress; and, with ex

ceptions not pertinent here, Congress has the power

to give, withhold and restrict our jurisdiction."

(emphasis added)

See also Carlson v United States, 364 F 2d 914 (10th Cir

1966) .

D. PRICE CONTROL

The Emergency Price Control Act of 1942 gave rise to

several cases discussing the power of the Congress to limit

judicial review in the area of wartime price controls.

24

The Emergency Price Control Act of 1942 provided that a

person subject to an order or regulation of the Administrator

under the Act could first file a protest of the Administrat

or's action and could thereafter appeal such action only

to the Emergency Court of Appeals created under the Act

and thereafter to the United States Supreme Court. The

Emergency Price Control Act also provided that the Emergency

Court of Appeals and the Supreme Court had exclusive jurisdic

tion over the subject matter involved and no other court,

federal, state or territorial, could have jurisdiction or

power to consider the validity of any regulation or order

of the Administrator. Finally, the Emergency Price Control

Act provided that the Emergency Court of Appeals and the

United States Supreme Court were denied the jurisdiction

to issue a temporary stay or injunction to prohibit the

enforcement of the Administrator's regulations or orders

during the pendency of an appeal from the denial of a protest,

taken to the Emergency Court of Appeals or the United States

Supreme Court. [3]

In Lockerty v Phillips, 319 US 182, 87 L Ed 1339 (1943) ,

the United States Supreme Court upheld the validity of that

portion of the statute removing jurisdiction of the subject

matter from all other courts. In its opinion, the court

stated at page 187:

^3] Of interest also is the Economic Stabilization Act of

1970, as amended Dec. 22, 1971, which provides in Sec. 211,

as follows:

"(e)(1) . . . [N]o interlocutory or permanent injunction

restraining the enforcement, operation, or execution of this

title, or any regulation or order issued thereunder, shall be

granted by any district court of the United States or judge thereof.

"(f) The effectiveness of a final judgment of the Temporary

Emergency Court of Appeals enjoining or setting aside in whole

or in part any provision of this title, or any regulation or order

issued thereunder, shall be postponed until the expiration of

thirty days from the entry thereof, except that if a petition for

a writ of certiorari is filed with the Supreme Court under sub

section (g) within such thirty days, the effectiveness of such

judgment shall be postponed until an order^bf the Supreme CQurt denying such petition becomes final, or until other final position of the action by the Supreme Court.

25 rr-

"There is nothing in the Constitution which requires

Congress to confer equity jurisdiction on any particular

inferior federal court. All federal courts, other

than the Supreme Court, derive their jurisdiction wholly

from the exercise of the authority to "ordain and

establish" inferior courts, conferred on Congress

by Article 3, §1, of the Constitution. ... The con

gressional power to ordain and establish inferior courts

includes the power "of investing them with jurisdiction

either limited, concurrent, or exclusive, and of with

holding jurisdiction from them in the exact degrees

and character which to Congress may seem proper for

the public good." (emphasis added)

And at page 188, the Court stated:

"In light of the explicit language of the Constitution

and our decisions, it is plain that Congress has the

power to provide that the equity jurisdiction to restrain

enforcement of the Act, or of regulations promulgated

under it, be restricted to the Emergency Court, and,

upon review of its decisions, to this Court."

In a subsequent opinion, Yakus v United States, 321

US 414, 88 L Ed 834 (1944), the Court considered the question

not raised in Lockerty, as to whether Congress could withhold

from the courts actually vested with subject matter juris

diction of price control appeals, (the Emergency Court

of Appeals and the United States Supreme Court) the power

to stay an order or regulation of the Price Control Admini

strator or the power to issue an injunction prohibiting

the enforcement of such order or regulation. In upholding

this provision of the Emergency Price Control Act, the

Supreme Court stated, at page 437:

"In the circumstances of this case we find no denial

of due process in the statutory prohibition of a tem

porary stay or injunction."

And at page 441:

"Here, in the exercise of the power to protect the

national economy from the disruptive influences of

inflation in time of war Congress has seen fit to post

pone injunctions restraining the operations of price

regulations until their lawfulness could be ascertained

by an appropriate and expeditious procedure. In so

doing it has done only what a court of equity could

have done, in the exercise of its discretion to protect

the public interest. What the courts could do Congress

26

can do as the guardian of the public interest of the

nation in time of war." (emphasis added)

Finally, at page-444, the court stated:

"There is no constitutional requirement that test

be made in one tribunal rather than in another, as

long as there is an opportunity to be heard and for

judicial review which satisfies the demands of due

process, as is the case here."

E. DUE PROCESS AND GENERAL APPLICATION

1. Section 803 meets all requirements of one process.

The applicability of the above precedents, and particu

larly the Yakus line of reasoning, to Section 803 is clear.

In the exercise of its constitutional grant of power and

control over the federal judiciary, Congress has seen fit

to speak to the procedures by which the courts, at all levels,

shall determine the ultimate substantive rights and remedies

of all the parties in a particular category of litigation.

The Yakus case is especially relevant because it dealt

with a congressional mandate of a stay of proceedings. The

Emergency Price Control Act provisions allowed the Price

Control Administrator to impose substantial controls over

individuals and then required that such controls, which were

administratively ordered changes from the status quo, be

maintained during the process of appeals. So long as ade

quate appellate procedures were available, there was no

denial of due process by limiting the interlocutory juris

diction of the courts during the pendency of such appeals

even though, as was admitted by the court in discussing

the Lockerty and Yakus cases, irreparable harm could occur.

In the instant case, a similar restriction on the jurisdic

tion of the courts during the pendency of appeals has been

imposed by the Congress with one significant difference:

The stay mandated by Section 803 maintains the status quo,

while the Emergency Price Control Act mandates the con

tinuance of a questionable order or regulation.

27

I

As stated in Yakus, page 444, supra, the demands of

due process must be met in cases where congressional restraints

on the general jurisdiction of the federal courts are imposed,

once such general jurisdiction is granted. This was discussed

in the case of Battaglia v General Motors Corp, 169 F 2d

254 (2d Cir 1948) , a case involving the Portal-to-Portal

Act. The United States Supreme Court, in several cases

preceding the Portal-to-Portal Act, had interpreted the

Fair Labor Standards Act of 1938 as granting certain claims

for time spent by employees before and after the performance

of their main activities. Congress responded by enacting

the Portal-to-Portal Act, which deprived both state and

federal courts of jurisdiction to entertain the claims under

the Fair Labor Standards Act and outlawed the substantive

liability for the claims themselves. The Second Circuit

held that while Congress might not have the power to simply

remove the jurisdiction of all courts to entertain actions

to enforce such claims, the denial of jurisdiction was proper

where the effect of the withholding of jurisdiction itself

was not the cause of extinguishing the substantive liabilities

involved. At page 257, the Court stated:

"We think, however, that the exercise by Congress

of its control over jurisdiction is subject to compliance

with at least the requirements of the Fifth Amendment.

That is to say, while Congress has the undoubted power

to give, withhold, and restrict the jurisdiction of

courts other than the Supreme Court, it must not so

exercise that power as to deprive any person of life,

liberty, or property without due process of law or

to take private property without just compensation."

In the instant cause it is clear that Section 803 does

not deny due process since it simply requires the maintenance

of the status quo during the pendency of appeals. The issue

is resolved by the language and holdings of Yakus, at page

442, supra:

28

" . . . legislative formulation of what would otherwise

be a rule of judicial discretion is not a denial of

due process or a usurpation of judicial functions".

The case at bar indeed involves allegations and findings

regarding substantive constitutional rights under the 14th

Amendment of the Constitution of the United States and these

rights may not be extinguished by action of Congress. The

manner in which these substantive constitutional rights

are to be safeguarded and the establishment of procedures

to remedy denials of these rights by the courts of the

United States is reserved, however, by Article III, Section

1 of the United States Constitution,to the Congress. Within

the teachings of Yakus and Battaglia, so long as minimum

due process requirements of the Fifth Amendment are met,

Congress may exercise its wide discretion in mandating the

procedural jurisdiction of the lower federal courts in this

area which is of such national concern today.

2. Section 803 does not violate any constitutional

requirement of immediate relief.

Intervening School Districts are aware that the argument

has been made that Section 803 is unconstitutional for

the reason that it abrogates a constitutional interest

in immediate relief. This argument has been based upon

the teachings of the United States Supreme Court in Alexander

v Holmes County Board of Education, 396 US 19, 24 L Ed 19

(1969) and Carter v West Feliciana Parish School Board,

396 US 290, 24 L Ed 2d 477 (1970). These cases are further

amplifications of the principle stated in Green v County

School Board of New Kent County, 391 US 430, 20 L Ed 2d

716 (1968). In that case the United States Supreme Court

reiterated that the "deliberate speed" standard established

29

in the second Brown decision in 1955,- 349 US 294 , was no

longer applicable, c.f. Griffin v County School Board, 377

US 218, 12 L Ed 2d 256 (1964), and that the burden on a

school board today is to come forward with a plan that promises

to work and "promises realistically to work now". 391 US

439, 20 L Ed 2d 724. Reasoning from the conclusions of

these cases, opponents of the validity of Section 803 have

made the argument that there is now a constitutional interest

in immediate implementation of a plan upon a prima facie

showing of continued segregation.

It is submitted that the principle of the above cases

does not extend to the facts of the case at bar, which are

totally distinguishable. In each of the above cited cases,

the existence of a dual school system, constituting de

jure segregation, was at issue. Each one of the school

systems in the above cited cases had operated dual systems

prior to 1954, and thereafter, by operation of state law.

This simple fact was either admitted or previously adjudicated

in all of those cases. Thus the issue of "liability" had

been completely resolved and the only question before the

United States Supreme Court and the lower appellate courts

was that of the timing and efficacy of implementing a plan

of desegregation. The comment of Justices Harlan and White

in a concurring opinion in Carter v West Feliciana Parish

School Board, supra, to the effect that the burden, in actions

similar to the Alexander case, should be shifted from Plain

tiffs, seeking redress for a denial of constitutional rights,

to Defendant school boards, and to the further effect that:

What this means is that upon a prima facie showing

of non compliance with this Court's holding in Green

* v County School Board of New Kent County, 391 US 430,

20 L Ed~2d 716, 8lT~S~Ct 1689 (1968), sufficient to

demonstrate a likelihood of success at trial, plain

tiffs may apply for immediate relief that will at once

extirpate any lingering vestiges of a constitution

ally prohibited dual school system.,

must be read as applicable only to a case where the issue

of the existence of a "constitutionally prohibited dual

school system" has been resolved unfavorably to the defendant

school board. Intervening School Districts contend that

the teachings of the United States Supreme Court in the

above cited line of cases accordingly apply only after full

resolution of the issue of de_ jure segregation. In the

case at bar, this issue has not been fully resolved through

appellate process. As outlined in this Brief, and as this

Court knows, there are serious questions of lav/, both as

to the issue of the existence of de_ jure segregation with

the school district of the City of Detroit and as to the

appropriateness of metropolitan relief in this cause. There

has been no allegation or adjudication of the existence

of a dual school system within the Defendant Intervenors'

school districts. Accordingly, it should be readily apparent

that the United States Supreme Court has not ruled that

the right to implementation of a plan of desegregation under

the Constitution is immediate, except in instances where

the existence of a dual school system in violation of the

Constitution has been finally adjudicated or admitted.

Thus, it is clear that Section 803 cannot be held uncon

stitutional in the context of the case at bar where there

has been no exhaustion of appellate remedies on the issues

of liability in the first instance.

Even in a case involving the application of Section

803 to an order transferring students, where there has been

31

full adjudication and exhaustion of appeals on the issue

of liability, there is no reason why the Section cannot

be reasonably accommodated to the teachings of the United

States Supreme Court in the above cited line of cases.

Indeed, the Supreme Court has clearly indicated an immediacy

requirement, once the existence of a dual system has been

finally adjudicated (and Defendants contend that such finality

must include the complete exhaustion of appeals on such

issue). If at that point, a separate order transferring

students or further implementing a plan of desegregation

previously adopted is entered, it is clear that Section

803 would compel the postponement of effectiveness of that

order until any appeals from that order have been exhausted.

However, under the teachings of Green, Alexander, and Carter,

supra, any appellant would have extreme difficulty defending

a motion to dismiss an appeal, in view of the immediacy

requirements. Accordingly, any delay extended by Section

803 would, under those circumstances, be of an extremely

brief nature and would undoubtedly still meet the requirements

of those cases, notwithstanding the application of Section

803.

In summary, the question simply resolves itself into

one of whether or not Section 803 is an attempt by the

Congress to circumscribe the constitutional rights of the

Plaintiffs guaranteed to them by the Fourteenth Amendment,

or a direction by the Congress as to the procedures by which

these substantive rights will be enforced by the courts

of the United States. It is respectfully submitted that

Section 803 could not be more clearly procedural in nature.

The ultimate declaration of the substantive rights of the

32

parties to this case will not be affected by the application

of Section 803 any more than the ultimate determination

of the substantive rights of the parties was affected in

those desegregation cases where the courts, in the exercise

of their discretion, granted a stay of proceedings to main

tain the interests of all of the parties in status quo.

Considering the serious and substantial questions relative

to the issues of "liability" and "remedy" and their potential

affect on parties Plaintiff and Defendant it cannot be said

that the delay during appeal will per se constitute a denial

of substantive constitutional rights. As stated so well

in Yakus, Congress "has done only what a court of equity

could have done, in the exercise of its discretion to protect

the public interest."

Ill

QUESTIONS AS TO THE INTENDED APPLICATION

OF SECTION 803 ARE CONTROLLED BY ITS

_________LEGISLATIVE HISTORY____________

The legislative history of an Act of Congress is composed

of the debates, amendments, committee reports, and explanations

by its sponsors and managers attending a bill which subsequently

becomes law. The legislative history of a law may be resorted

to as an aid in determining the proper construction of a

statute which is ambiguous or of doubtful meaning. Annot.

70 A.L.R. 5, 6, (1931); Blake v National City Bank, 23 Wall.

307, 23 L Ed 119 (1875); Railroad Commission v Chicago B.

& Q. R. Co, 257 US 563, 66 L Ed 371 (1922); Duplex Printing

Press Co v Peering, 254 US 443, 65 L Ed 349 (1921); United

States v Great Northern R. Co, 287 US 144, 77 L Ed 223 (1932) ;

Wright v Mountain Trust Bank, 300 US 440, 81 L Ed 736,

(1937); Mitchell v Kentucky Finance Co, 359 US 290, 3 L Ed

33

2d 815 (1959); Swann v Charlotte-Mecklenberg, 402 US 1,

16, 17, 28 L Ed 2d 554, 567 (1971) and numerous other cases

cited in 70 A.L.R. 5, 6, 7, 8.

It is anticipated by the Intervening School Districts

that issue will be taken as to the meaning and application

of several aspects of Section 803. Because it is certainly

possible that Section 803 is capable of several interpreta

tions as to its affect on Orders antedating the effective

date of the statute, its affect on suits pending as of the

effective date, and whether it applies to all Orders requiring

the transfer and transportation of students, even if in

pursuance of a finding of unlawful segregation, the correct

interpretation must be determined by examination of the

legislative history.

The rule as to the applicability of legislative history

in construing the intent of a statute has been summarized

as follows:

In construing legislative intent by reference to the

legislative history, the Court must differentiate between

statements made by individual legislators and those made

by the sponsors of the Bill, the chairmen of the committees

which consider the Bill, and the conference committee reports.

Annot., 70 A.L.R. 5, 26-39.

In considering the legislative history of a statute,

Mr. Justice Frankfurter, joined by Black and Burton, JJ. ,

dissenting, in agreement with the majority on this point

stated the following:

It has never been questioned in this Court that

committee reports as well as statements by those

in charge of a bill or of a report, are authorita

tive elucidations of the scope of a measure.

Schwegmann Bros v Calvert Distillers Corp, 341 US

384, 399, 400, 95 L Ed 1035, 1050, 1051 (1951).

34

See also Duplex Printing v Peering, 254 US 443, 474, 65

L Ed 349 (1921); and Railroad Commission v Chicago, B. &

Qjl Jk. £2' 257 563, 66 L Ed 371 (1922) .

In considering weight to be given to statements made

by the sponsors of a bill the Supreme Court has stated:

We have often cautioned against the danger, when in

terpreting a statute, of reliance upon the views of

its_legislative opponents. in their zeal to defeat

they understandably tend to overstate its reach.

The fears and doubts of the opposition are no auth

oritative guide to the construction of legislation.

It is the sponsors that we look to when the meaning

o ^the statutory words is in doubt." Schwegmann Bros

v Calvert Distillers Corp, 341 US 384 ,“"394-395, 95---

L Ed 1035, 1048 (1951); see also Mastro Plastics Coro

v 350 US 270, 2 88, 100 L~ETT0 97~32T7l956T;

NLRB v Fruit &_ Vegetable Packers, 377 US 58 , 66 , 12 ‘

L Ed 2d 129, 135 (1964); Woodwork Mfg Assoc v NLRB.

386 US 612, 639, 640, 18 L Ed 2d 357, 375 (1967)T“

In United States v United Mine Workers, 330 US 258,

91 L Ed 884 (1947), statements were made regarding the

proper construction of a statute by the sponsor of the

bill m the House of Representatives and by the ranking

minority member of the committee which reported the bill.

These statements were not challenged by any representative

voting for the bill and because the Senate did not express

a contrary understanding, the Court felt that such legislative

history was "determinative guidance" in establishing the

proper statutory construction. The massive number of cases

which have been decided on the basis of legislative history

is illustrated by Appendix A to Mr. Justice Frankfurter's

dissenting opinion in Commissioner of Internal Revenue

v Uhuuuh, using three pages to list "Decisions During the

Past Decade in which Legislative History was Decisive of

Construction of a Particular Statutory Provision". 335

US 632, 687, 688, 689, 93 L Ed 288, 321, 322, 323 (1949).

35

One of the most recent examples of the use by the

United States Supreme Court of legislative history of Con

gressional Legislation is Swann v eharlotte-Mecklenberg,

402 US 1, 16, 17, 28 L Ed 2d 554, 567 (1971).

IV

THE LEGISLATIVE HISTORY OF SECTION 803

As indicated in the foregoing portion of this Brief,

it is proper and necessary for the courts to look to the

legislative history of laws when their interpretation is

subject to question. In such cases, the intent of Congress

as expressed in its debates and committee reports will

be determinative of the interpretation to be placed on the

law in question.

With respect to Section 803, there is ample legislative

history to support the position urged by the Newly Inter

vening School Districts.

The first phase in the history of Section 803 was when

it was introduced by Congressman Broomfield in the U.S.

House of Representatives on November 4, 1971 as a non-germane

amendment to the "Education Amendments of 1972". On that

evening, Mr. Broomfield stated:

Mr. Chairman, my amendment would postpone the effective

ness of any U.S. district court order requiring the

forced busing of children to achieve racial balance

until all appeals to that order have been exhausted.

* * *

. . . [S]ome U.S. federal courts have ordered busing

in recent months. In many instances, I feel that these

orders are breaking new constitutional ground - that

these orders have created a new and unprecedented

extension of existing law.

* * *

We can expect that many of these decisions ordering

busing will be appealed and that on appeal they may

be overturned. However, the appeals process is a long

36

and difficult one. It may take two or three years.

Thus, before the courts can completely decide this

question, before the law is crystalized once and for

all, busing will have become an accomplished fact.

Mr. Chairman, forced busing may prove to be an expen

sive, time consuming and disruptive mistake.

My amendment would only delay a lower court's busing

order until all those parties have had a chance to

plead their case at their court of last resort.

* * * *

Congressional Record - House H10407, H10408, November

4, 1971. .

Although too extensive to be repeated herein at length,

the discussion by one of the Co-Sponsors, Congressman Nedzi,

as reported in the Congressional Record, constitutes des

cription of the entire history of the instant case and events

leading to the submission of Section 803, and demonstrates

beyond doubt that it was the specific intention of the

Co-Sponsors that Section 803 be applicable to Bradley v

Milliken. Congressional Record - House H10416, H10417,

November 4, 1971.

Following passage of the "Education Amendments of 1972"

in the House, with Section 803 as an amendment, and passage

of the "Education Amendments of 1972" in the Senate, but

containing different "anti busing" amendments, the Act again

came up for debate in the House on a motion to send it to

Conference Committee. In addressing Section 803, the following

debate in the House was had on March 8, 1972:

MR. BROOMFIELD. Mr. Speaker, I rise to stress the

importance of retaining the House language of the

amendment to stay busing orders until all appeals have

been exhausted.

* * *

Mr. Speaker, the other body would have us discriminate

against some busing orders. Some orders would be stayed

pending appeal and others would not. We should write

the law so that it applies uniformly to all cases which

involve busing, otherwise, this law will be by definition,

unfair.

37

* * *

MR. GERALD R. FORD. I would like to ask the gentle

man several questions. First, is the Broomfield amend

ment retroactive?

MR. BROOMFIELD. Yes; it is.

MR. GERALD R. FORD. It is retroactive in its entirety?

MR. BROOMFIELD. In its entirety.

MR. GERALD R. FORD. The second question is this: Your

amendment states that the effectiveness of "any order"

to achieve a racial balance of students "shall be post

poned . "

Now, does that mean that it would affect orders which

have already been put into effect or put into partial

effect? In other words, all would be suspended pending

final appeal?

MR. BROOMFIELD. That is correct.

* * *

MR. GERALD R. FORD. Mr. Speaker, if the gentleman

will yield further, is it the intent of the author

of the amendment that this stay during an appeal of

any order shall be equally applicable not only to orders

’involving forced busing but to desegregation cases

generally?

MR. BROOMFIELD. Yes; it would be, in both cases.

* * *

Congressional Record - House - H1852, H1853, March

8, 1972.

The Conference Committee Report was ordered to be

printed on May 23, 1972, and stated, in part, as follows:

The conference agreement contains the precise lan

guage of the House amendment and provides that this

section shall expire midnight, January 1, 1974. This

section does not authorize the reopening of final orders,

however, appealable orders are considered to be within

the scope of this amendment. The conferees are hopeful

that the judiciary will take such action as may be

necessary to expedite the resolution of the issues

subject to this section. (Emphasis supplied).

U.S. House of Representatives, 92d Congress, 2d Session,

Report No. 92-1085, Education Amendments of 1972, May

23, 1972, p. 220.

38

The Conference Committee Report was brought before

the Senate in May of 1972. Senator Pell was the manager

in the Senate for the Conference Committee Report containing

Section 803. During the ensuing debates on the Senate floor

on May 23, 1972, the following occurred:

Senator Pell......... The conferees struggled long

and hard over the so-called busing amendments. The

Conference Report adopts verbatim the Broomfield Amend

ment, except that the duration of the Amendment is

limited to January 1, 1974. During conference discussion,

there was disagreement as to the meaning of the Broom

field language. Here I would say that a literal reading

of the language by a non-lawyer would indicate that

if a local educational agency is under an appealable

order to transport students to achieve racial balance,

that local educational agency can receive a stay of

that order whether it has been implemented or not.

I expect that today's debate will bring disagreement

from those who have more of a legal background on the

subject than I. However, I would say that the Senate

is not in the habit of enacting frivolous language,

and those who interpret our work as a sham and a fraud

do injustice to both the Senate and the House. Page

S8282.

* * *

Senator Javits, speaking against the Broomfield Amendment,

stated:

Then, Mr. President, we come to the Broomfield Amend

ment, which was finally compromised as between the

two bodies, and here again we have an absolutely flat,

automatic stay of any order until appeals have been

exhausted. At least, if you take the language for

what the House sponsors say it means - and I will dis

cuss that in a moment - you have an automatic stay

for 19 (sic) months of any lower court order which

would seek either to transfer or to transport students

in respect of what again I say the Amendments House

sponsors claim is an effort to desegregate in order

to comply with the Constitution. Page S8286.

Senator Dominick, who is the ranking minority member

of the Education Subcommittee of the Senate and a member

of the Conference Committee which reported on Section 803,

stated as follows:

MR. DOMINICK. Mr. President, as the ranking minority

member of the Education Subcommittee, I rise in support

of the Conference Report of the Education Amendments

of 1972.

39

* * *

To those colleagues who oppose the Conference Report