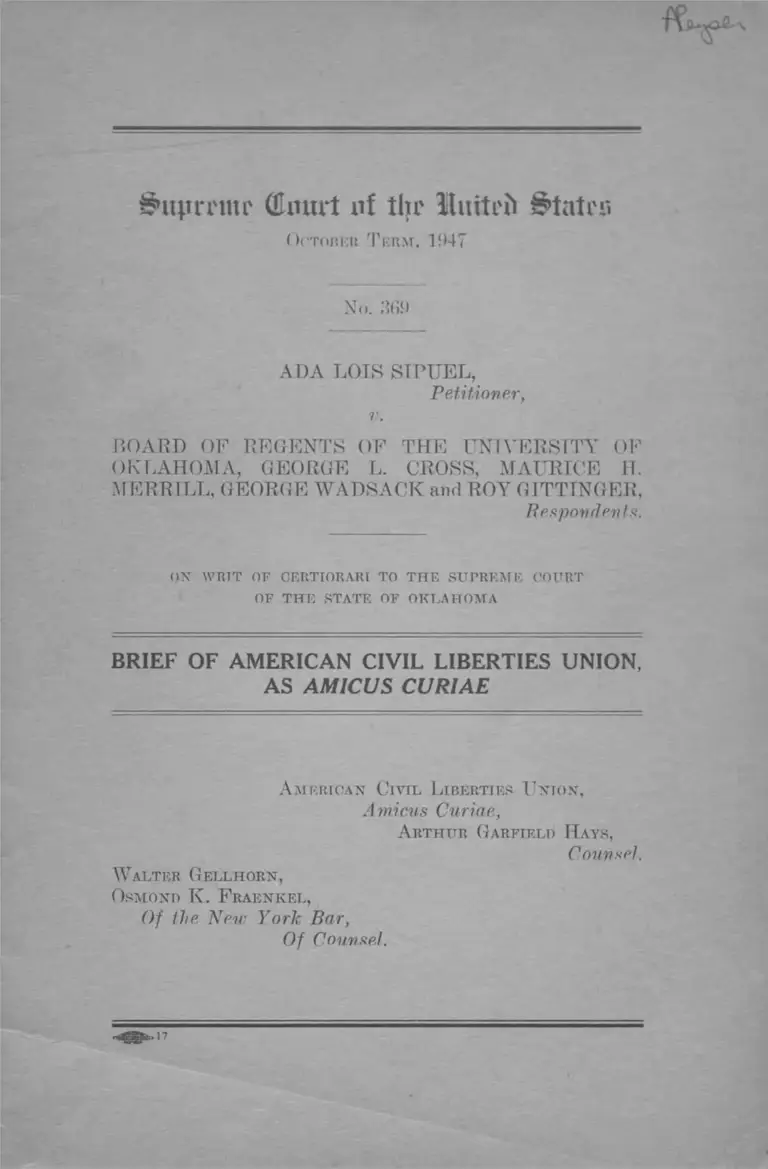

Sipuel v Board of Regents of UOK Brief of Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

October 1, 1947

12 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Sipuel v Board of Regents of UOK Brief of Amicus Curiae, 1947. 7f1e1997-c49a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/bed8cedc-f320-43e1-bc45-9cb9afd5fbe7/sipuel-v-board-of-regents-of-uok-brief-of-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

^ujtrrmc GImtrt nf tljr lHuitrft States

October T erm, 1947

No. 3(19

ADA LOIS SIPUEL,

Petitioner,

v.

HOARD OF REGENTS OF THE UNIVERSITY OF

OKLAHOMA, GEORGE L. CROSS, MAURICE H.

MERRILL, GEORGE WADSACK and ROY GITTTNGER,

Respondents.

OX WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT

OF THE STATE OF OKLAHOMA

BRIEF OF AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION,

AS AMICUS CURIAE

A merican Civil Liberties Union,

Amicus Curiae,

A rthur Garfield H ays,

Counsel.

W alter Gellhorn,

Osmond I\. F raenkel,

Of the New York Bar,

Of Counsel.

*1 7

I N D E X

PAG E

I nterest of A merican Civil Liberties U nion ............. 1

F acts ................................................................................................ 2

Point I.—The requirement that petitioner give notice

that a separate law school be opened and the

inevitable delay in opening it cast an unequal

burden on petitioner .................................................. 3

P oint II.—Admission of petitioner to a separate law

school for Negroes would not constitute equal

protection ..................................................................... 5

Point III.— Segregation of Negroes from whites vio

lates the equal protection clause .............................. 7

Table of Cases

Gong Luiri v. Rice, 275 U. S. 7 8 ...................................... 8

McCabe v. Atchison, T. S. F. Ry., 235 U. S. 151 ....... 4

Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337 .......3, 4, 5

Mitchell v. United States, 313 U. S. 8 0 ........................ 4

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537 ................................. 8

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U. S. 303 .................... 7, 8

Constitutional Provisions

Article VI .........

13th Amendment

14th Amendment

15th Amendment

4

1, 3,4, 7,8

....... 7

Supreme Court ot tljr H&mUb Stairs

October T erm, 1947

No. 369

--------- * i ■ ---------

A da L ois Sipuel,

Petitioner,

• v.

B oard of R egents of the U niversity of Oklahoma,

George L. Cross, M aurice H. M errill, George W adsack

and R oy Gittinger,

Respondents.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT

OF THE STATE OF OKLAHOMA

----------- * i m ------------

BRIEF OF AMERICAN CIVIL LIBERTIES UNION,

AS AMICUS CURIAE

The American Civil Liberties Union, which is devoted

to the furtherance of the civil rights guaranteed by the

Constitution of the United States, submits this brief in

the belief that respondents’ refusal to admit petitioner to

the School of Law of the University of Oklahoma consti

tutes a violation of that provision of the 14th Amendment

to the Constitution of the United States which provides

that no State shall “ deny to any person within its juris

diction the equal protection of the laws.”

2

The Facts

The facts have been admitted by respondents (E. 22-25).

Petitioner brought this proceeding in the District Court

of Cleveland County, Oklahoma, seeking mandamus to

compel respondents to admit her to the School of Law of

the University of Oklahoma (R. 2-6). Petitioner is a

resident and citizen of the United States and of Oklahoma;

she desires to practice law in Oklahoma and, to that end,

being fully qualified financially, scholastically and morally,

applied for admission on January 14, 1946, to the School

of Law of the University of Oklahoma, the only law school

maintained by the state (R. 22, 23). Petitioner was

refused admission solely because she is a Negro (R. 24),

and this suit followed on April 6, 1946 (R. 2). Respond

ents are the Board of Regents of the University of Okla

homa, which has authority as to the admission of students

to the University, George L. Cross, President of the

University, Maurice H. Merrill, Dean of the School of

Law, Roy Gittinger, Dean of Admissions, and George

Wadsack, Registrar (R. 3-4, 14). All the personal

respondents act pursuant to orders of respondent the

Board of Regents of the University (R. 4, 14).

The University of Oklahoma is maintained by public

funds raised by taxation, and the School of Law specializes

in Oklahoma law (R. 23). Indeed, unless petitioner is

permitted to attend the School of Law, she will be placed

“ at a distinct disadvantage” both at the Oklahoma bar

and in the Oklahoma public service, vis a vis those who

have gone to the School of Law (R. 23), to which, how

ever, only whites are admitted (R. 16-17, 23-24).

Petitioner did not apply to the Board of Regents of

Higher Education of Oklahoma to set up a separate law

school for Negroes, although after this action was filed

3

that Board considered whether it should open sucli a

school and concluded that it had no funds so to do and

that it had never requested or been asked to request such

funds from the State Legislature (R. 24-25).

The District Court of Cleveland County denied the writ

of mandamus (R, 25), on the ground that petitioner had

not chosen the proper form of action in which to raise

the Constitutional question (R. 21-22). The Supreme

Court of Oklahoma affirmed (R. 51). It explicitly refused

to pass on whether mandamus was the appropriate rem

edy, and decided “ the merits” of the claim that failure

to admit petitioner to the School of Law constituted a

discrimination “ on account of race contrary to the 14th

Amendment to the United States Constitution” (R. 38).

The reasoning of the Supreme Court was that the state's

policy, specifically embodied in its statutes, is to segre

gate Negroes and whites in its educational institutions,

that this policy is valid under the language of Missouri

ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337, and other cases,

and that if the State may satisfy the 14th Amendment

by a separate law school for Negroes, it was incumbent

upon petitioner to make known by demand or other form

of notice to the Board of Regents of Higher Education

her desire for separate legal education, which she has

failed to do (R. 38-51).

POINT I

The requirement that petitioner give notice that a

separate law school be opened and the inevitable delay

in opening it cast an unequal burden on petitioner.

Assuming arguendo that Oklahoma could and would,

after appropriate demand or notice, open a law school

which petitioner may attend, “ equal” in the Constitu

4

tional sense to the law school to which she has applied

for admission, that fact would not, contrary to the posi

tion of the Court below and of respondents, indicate

satisfaction of the equal protection clause. It is not

asserted that whites are subject to any burden to give

such notice or make such demand. It is undisputed (R.

24-25) that there are no State funds available with which

to open without delay a separate law school. The addi

tional burden to give notice or make demand and the

inevitable delay in opening another school in themselves

make plain the inequality of treatment petitioner has

been accorded. That inequality is not to be justified by

reference to the so-called “ valid” state policy of segre

gation. Even assuming, without conceding, that separate

facilities for Negroes may in some instances satisfy the

demands of equal protection, we start, hy reason of the

Supremacy Clause of the Constitution, Article VI, with

the 14th Amendment which prohibits the state from deny

ing to any “ person” the “ equal protection of the laws.”

We do not start with the assumption that segregation is

“ valid” per se so that additional burdens, both of time

and circumstance, may be visited on a Negro, asserted

by the Oklahoma Supreme Court to be the first such to

desire legal education in Oklahoma (R. 41), in order to

enable the state to pursue its policy of segregation. The

right given by the equal protection clause is a personal,

not a group, right. McCabe v. Atchison, T. S. F. Ry.,

235 U. S. 151, 161, 162; Mitchell v. United States, 313

IT. S. 80, 97; Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, supra,

350, 351. The state may not, in the words of the Amend

ment, “ deny to any person” that right. Segregation

does not justify discrimination, even on the assumption

that segregation does not demonstrate discrimination.

5

Further, the discrimination is not “ excused by what is

called its temporary character.” Missouri ex rel. Gaines

v. Canada, supra, 352. Petitioner was entitled to “ equal

protection” when she applied for admission on January

14, 1946, to the only law school supported by the state.

The additional burden and delay imposed upon her by

the Court below demonstrate the lack of “ equal protec

tion” which she has received.

POINT II

Admission of petitioner to a separate law school

for Negroes would not constitute equal protection.

Even if we were to assume for the sake of argument

that a law school physically identical to that to which

petitioner has applied were available to her, and that

segregation in some contexts is valid, the segregation of

petitioner in a separate school to which only Negroes

would be admitted would, by the very nature of the

educational process, deny to petitioner the equal protec

tion to which she is entitled.

The agreed facts of record show that petitioner “ will

be placed at a distinct disadvantage at the bar of Okla

homa and in the public service of the aforesaid State with

persons who have had the benefit of the unique prepara

tion in Oklahoma law and procedure offered to white

qualified applicants in the School of Law of the Univer

sity of Oklahoma, unless she is permitted to attend the

School of Law of the University of Oklahoma” (R. 23).

Petitioner can reach an equal footing at the bar of Okla

homa and in its public service with white lawyers only

if she attends the School of Law of the University of

Oklahoma and participates in its “ unique” course. Unless

6

slip does so, she “ will be placed at a distinct disadvan

tage.” Tt follows that she will he placed at a disadvan

tage if she is admitted, not to the school giving “ unique”

preparation, but, to a law school which will educate only

Negroes, perhaps only herself.

It is plain why the course given at any such separate

school could not be equal to the “ unique” course given at

the Law School of the University. Even the novitiate will

admit that education, and legal education in particular,

is not a matter of bricks and mortar or even of books

and paper. Instructors so successful as to give a

“ unique” course could hardly be duplicated. But neither

is legal education the sole work of the professors. The

students play a substantial role in individual self-instruc

tion, and in the education of one another. Which lawyer

is there whose abilities were not sharpened and enhanced

by the varied personalities, abilities and propensities of

his fellow students at law school? What makes a great

law school, the books, the professors, or the students?

It would be a bold Oklahoman who could say that not

one white student in the law school of the State Univer

sity was capable of contributing to the legal education

of petitioner.

The Court below made much of the fact that petitioner

is the first Negro to desire legal education within Okla

homa (R. 41). Will a legal education in which petitioner

will have few, if any, fellows occupying a similar educa

tional position be as fruitful as one in which the ideas

of the official educators will be tested, perhaps rejected,

by varied intellects within a substantial student body?

Further, in the absence of the point of view of the white

one-half or more of the State’s population, those ideas

could hardly be effectually tested and appreciated. Peti

tioner is entitled to a legal education equal to that of the

white students, who could contribute to her education

as well as their own.

POINT III

Segregation of Negroes from whites violates the

equal protection clause.

The 14th Amendment is one of the three Constitutional

provisions “ having a common purpose; namely, securing

to a race recently emancipated, * * * the enjoyment

of all the civil rights that under the law are enjoyed by

white persons.” Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U. S.

303, 306. Before the Civil War discrimination against

Negroes had been habitual both in the community’s atti

tude and in the official laws of the states. Indeed, most

Negroes were slaves, and the race had long been regarded,

officially and unofficially, as inferior and subject. The

13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments were a reaffirmation of

the principle that those who were equal in the sight of

Cod were equal too in the sight of the Nation. And so,

the Nation prohibited the States from proceeding upon

an assumption of the inferiority of Negroes which the

blood of a great war had washed away. By the equal

protection clause the Negroes were given “ a positive

immunity, or right, most valuable to the colored race,—

the right to exemption from unfriendly legislation against

them distinctively as colored,—exemption from legal dis

criminations, implying inferiority in civil society.”

Strauder v. West Virginia, supra, 307-308. The States

were prohibited from taking action with respect to the

Negroes as would be “ a brand upon them, affixed by the

8

law, an assertion of their inferiority, and a stimulant

to that race prejudice which is an impediment to securing

to individuals of the race that equal justice which the

law aims to secure to all others.” Strauder v. West Vir

ginia, supra, 368. (Italics ours.)

What more explicit “ brand” upon petitioner, what

clearer “ assertion” of her “ inferiority” , could there be

than the segregation of her in a law school for Negroes

only? Segregation in itself serves no rational purpose

other than that found in the asserted inferiority of the

Negro. That purpose the Nation would not condone.

Even the case of Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537,

551, in which segregation of the races in separate rail

road cars was upheld, recognized that the State could

not “ stamp” the Negroes “ with a badge of inferiority” ,

but the Court held that “ solely because the colored race

chooses to put that construction upon it” Negroes should

not assume that segregation implies inferiority, for the

dominant whites and the state which they control make no

such assumption. There have been subsequent judicial

expressions which have followed the Plessy case without

examining its basic factual assumption that segregation is-

no assertion of inferiority. Gong Lum v. Rice, 275 U. S.

78, and cases cited. In each case in which segregation has

been upheld there has been no recognition that or investi

gation whether segregation of itself implies inferiority.

Can Oklahoma honestly say today that the official segre

gation of petitioner and her exclusion from the School of

Law of the University of Oklahoma, where only whites

may attend, is based any less on a notion of inferiority

than would be a brand or a chain? The equal protection

clause loosed the shackles and covered over the scars of

the brands which had been inflicted upon “ any person” .

No less does that clause shield petitioner from the brand

of segregation.

The judgment should be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

A merican Civil L iberties U nion,

Amicus Curiae,

A rthur Garfield H ays,

Counsel.

W alter Gellhorn,

Osmond K. F raenkel,

Of the New York Bar,

Of Counsel.