Norris v. State Council of Higher Education for Virginia Brief of Plaintiffs

Public Court Documents

January 25, 1971

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Norris v. State Council of Higher Education for Virginia Brief of Plaintiffs, 1971. e7ae04b4-bf9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/bf4a6bcc-af78-4dfd-9288-ab2427516e0d/norris-v-state-council-of-higher-education-for-virginia-brief-of-plaintiffs. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

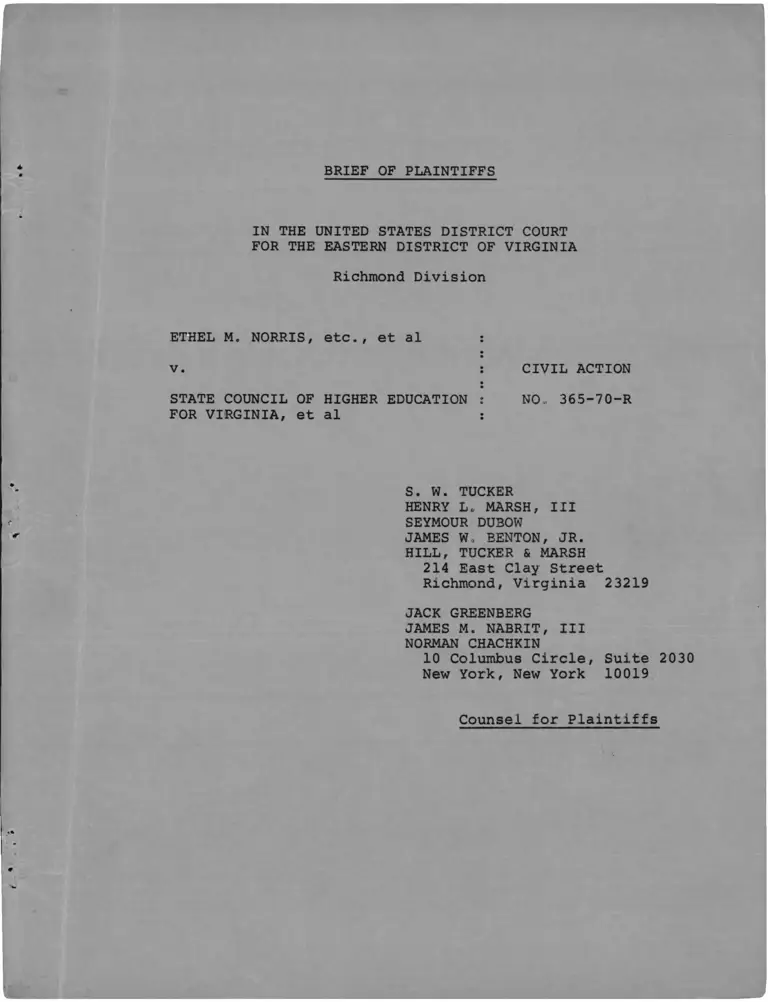

BRIEF OF PLAINTIFFS

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF VIRGINIA

Richmond Division

ETHEL M. NORRIS, etc., et al

v. CIVIL ACTION

STATE COUNCIL OF HIGHER EDUCATION

FOR VIRGINIA, et al

NO.. 365-70-R

S. W. TUCKER

HENRY Lc MARSH, III

SEYMOUR DUBOW

JAMES Wo BENTON, JR.

HILL, TUCKER & MARSH

214 East Clay Street

Richmond, Virginia 23219

JACK GREENBERG

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

NORMAN CHACHKIN

10 Columbus Circle, Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

Counsel for Plaintiffs

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

PRELIMINARY STATEMENT ---------------------------- 1

STATEMENT OF FACTS -------------------------------- 2

A. Virginia's Commitment to Racial

Segregation in Higher Education ------ 2

1. Separate Undergraduate Facilities

for Negroes---------------------- 2

2, The Out-Of-State Graduate Aid

Programs ------------------------ 3

Bo Virginia State College --------------------- 5

Co Richard Bland ------------------------------ 6

D. State and Federal Study Agencies

and Their Recommendations ---------- 7

E. Other Circumstances Material to a

Consideration of the Proposed

Escalation of Richard Bland College 12

Fo The Racial Pattern in Virginia's

Higher Education System ------------ 16

Go The Parties to this Action-------------- 19

ARGUMENT------------------------------------------- 20

Io The Special Three-Judge Court Is

Without Jurisdiction --------------- 20

II. The Fourteenth Amendment Forbids The

Maintenance Of A Racially Dual

System Of Higher Education --------- 24

III. The Racially Dual Character Of The

System Of Higher Education Has

Not Been Disestablished -1----------- 27 l

l

IV. Richard Bland Was Created To Serve

White Students Who Reside Within

Commuting Distance Of Virginia

State College------------------------ 29

V. The Proposed Escalation Of Bland Is

Without Sound Educational Purpose -- 31

VI. The Proposed Escalation Of Bland Is

Without Constitutionally Acceptable

Justification ------------------------ 33

VII. The Escalation of Bland Should Be

Enjoined----------------------------- 35

VIII. Richard Bland Should Be Merged With

Virginia State Or Put In The

Community College System ------------ 36

IX. The State Council Should Be Required To

Devise And Submit A Plan Whereby

The Racial Identifiability Of State

Supported Colleges And Universities

Will Be Eliminated------------------- 38

X, The Defendants Should Be Required To

Pay Costs And Reasonable Attorneys'

Fees To Plaintiffs' Counsel--------- 38

CONCLUSION------------------------------------------ 39

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE ------------------------------ 40

APPENDIX I

APPENDIX II

APPENDIX III

V 11

TABLE OF CITATIONS

Cases

Page

Alabama State Teachers Association v. Alabama

Public School and College Authority, 393

U.S. 400 (1969) -------------------------------- 24,25,33,34

Bailey v. Patterson, 369 U.S. 31, 82 S.Ct. 549

(1962) ----------------------------------------- 22

Bradley v. Board of Public Instruction (U.S.D.C.

M.D. Fla., C . A . No. 64-98 (1965)) ------------ 34,37,38

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 ------ 25,27,29,39

Ex parte Collins, 277 U.S. 565, 48 S.Ct. 585

(1927) ----------------------------------------- 23

Florida ex r e L Hawkins v, Board of Control,

350 U.S. 413 (1956) ---------------------------- 25

Green v. County School Board, 391 U.S. 430

(1968) ----------------------------------------- 25,26,35,36,37,

38

Green v. New Kent County, 391 U.S. 430 (1968) -- 28

Griffin Vo School Board of Prince Edward,

377 U.S, 218, 84 S.Ct. 1226 (1964) ----------- 22,23

Hatfield v. Bailleaux (1961 C.A. 9 Or.), 290

F ,2d 632, cert, den,, 368 U.S 862, 82 S.Ct.

105 — ----------- ------— ------------------- - 23

Kennedy v„ Mendoza-Martinez, 372 U.S. 144,

82 S.Ct. 554 (1963) ------------------ 21

Kier v, County School Board of Augusta County,

249 F. Supp, 239 (1966) ----------------------- 30

Lee v, Macon County Board of Education,

267 F. Supp 458 (M.D. Ala.) ------------------- 25

McLaurm v. Oklahoma State Regents, 399 U.S.

637 (1950)--------:--- 25

Missouri, ex rel Gaines v. Canada, 305 U.S. 337

(1938) ---- 4,25

Moody V, Flowers, 387 U.S. 97, 87 S.Ct. 1544

(1967) ------------ ------------------------

iii

22,23,24

TABLE OF CITATIONS

(Continued)

Page

Pearson v„ Murray, 169 Md- 478, 182 A 590,

103 ALR 706 ------------------------------------- 3

Petition of Public National Bank of New York,

278 U.S. 101, 49 S.Ct. 43 (1928) ------------- 23,24

Rorick v, Board of Commissioners, 307 U.S. 208,

50 S.Ct. 808 (1938) --------------------------- 23

Sanders v. Ellington, 288 F. Supp. 937

(M.Do Tenn. 1968) ----------------------------- 25,28,36,37,38

Sipuel v. Board of Regents, 332 U.S. 631 (1948)- 25

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U.S. 629 (1950) --------- 25

Wallace v„ United States, 389 U.S. 215 (1967) — 25

OTHER AUTHORITIES

Acts of Assembly, 1960 -------- ------- 6

Acts of Assembly, 1964 --------------- 3

Acts of Assembly, 1970 -------------------------- 20

Code of Virginia, 1970, as amended:

Section ,23-9-3 --------- 1------------------------ 7

Section 23-9,11----------------------- --------- 7

Section 23-9,15-------- ----------------------- 9

Section 23-10 — --- ----------------- 3

Section 23-12 — --- ----------- 4

Section 23-49.1 — ----------- --------- --------- - 21

Section 23-165 -------------------------------- 3,21

Section 23-165,1 -- 3

Section 23-168 ----- ---- ---- ------------- ------ 3,21

Section 23-173 --------*----------------------- - 4

Section 23-174.1 ------ 21

Section 23-174,9 ------ 21

iv

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF VIRGINIA

Richmond Division

ETHEL M. NORRIS, etc., et al :

V. : CIVIL ACTION

STATE COUNCIL OF HIGHER EDUCATION : NO. 365-70-R

FOR VIRGINIA, et al :

BRIEF OF PLAINTIFFS

PRELIMINARY STATEMENTS

This litigation was instituted to prevent"'the develop

ment of Richard Bland College, a two-year branch of the College

of William and Mary, located near Petersburg, into a four-year

degree granting institution for the accommodation of students

residing within commuting distance who otherwise would attend

the traditionally and yet predominantly black Virginia State

College at Petersburg. Moreover, the plaintiffs seek an order

requiring the racial desegregation of the several colleges and

universities maintained by the State of Virginia.

The plaintiffs are black students attending Virginia

State College, black high school students from the City of

Petersburg who expect to attend college, and black and white

faculty members of Virginia State College. The defendants are

the State Council of Higher Education, the Governor*of‘ Virginia,

the Board of Visitors of the College of William and Mary (parent

institution of Richard Bland College), the president*of Richard

The exhibits entered by the parties in this case will

be designated as follows:

PX - Plaintiffs'. Exhibits

VSC-X - Virginia State College's Exhibits

Paschall X and McNeer X - James Carson, President of

Richard Bland, and William

and Mary College's Exhibits

The transcripts of the depositions will be referred to

in the following manner:

Tr. I - January 15, 1971 depositions of Elgin M. Lowe,

et al ;

Tr. II - January 15, 1971 depositions of Roy E.

McTarnaghan;

Tr. Ill - January 18, 1971 depositions of Davis Y.

Paschall and James B. McNeer;

Tr. IV - January 18, 1971 depositions of Roy E.

McTarnaghan (continuation of January 15,

1971).

The Appendices will be designated as App. I, App. II, or App. III.

VIRGINIA'S COMMITMENT TO

RACIAL SEGREGATION IN HIGHER EDUCATION

Separate Undergraduate

Facilities For Negroes

Virginia system of higher education has been

characterized by a historical pattern of racial segregation

which was created and maintained pursuant to state law

(PX #4, p. 1).

Virginia State College and Norfolk State College

were the schools of higher learning for Negroes. Section

Bland College,and the Visitors of Virginia State Cdllege.

2

"Name of School; Curriculum. - The school for

Negro students near Petersburg, formerly known

as the Virginia Normal and Industrial Institute,

shall hereafter be known as the Virginia State

College. The curriculum of the College shall

embrace such branches of learning as relate to

teacher training, agriculture and the mechanic

arts without excluding other scientific and

classical studies."

Section 23-168 had created a Norfolk division of

Virginia State College which was not to extend beyond the

sophomore year. A 1956 amendment to this section permitted

the expansion of the college to a four-year degree granting

institution.

These statutes remained in force until repealed

by Chapter 70 of the Acts of Assembly, 1964 (Code §§ 23-165.1

et seq). The new legislation transferred control of the

college from the State Board of Education to a Board of

Visitors to be appointed by the Governor.

23-165 of the Code of Virginia as adopted in 1946 provided:

The Out-Of-State Graduate Aid Program

On January 15, 1936, the Maryland Court of Appeals

affirmed an order for the issue of the writ of mandamus

commanding the officers of the University of Maryland to

admit a young Negro as a student in the law school of the

university. (Pearson v. Murray, 169 Mdo 478, 182 A 590,

103 ALR 706). At its 1936 session the General Assembly of

Virginia enacted its Out-Of-State-Graduate-Aid statute

which, now codified as §23-10, provides:

"[W]henever any Negro, who is a bona fide

resident and citizen of this State and

possesses the qualifications. . . customarily

required for admission to any such State

3

institution of higher learning and education

. . . applies to the Virginia State College

for admission and enrollment in any graduate

or professional course or course of study

not offered in such College but offered at

one or more of the other State institutions

of higher learning and education, if it appear

to the satisfaction of the State Board of

Education that . . . such Negro, is unable to

obtain from some other State institution of

higher learning and education, other than the

one in which he seeks or sought admission,

educational facilities equal to those applied

for, and that such equal educational facilities

can be provided and furnished to the applicant

by a college, university or institution, not

operated as an agency or institution of the

State, whether such other facilities are located

in Virginia or elsewhere in the United States,

the State Board of Education is authorized, out

of the funds appropriated for such purposes to

pay to such person, or the institution attended

by him and approved by the Board, as and

when needed, an amount equal to the amount,

if any, by which the cost to such person to

attend such college, university or institu

tion, not operated as an agency or institu

tion of the State exceeds the amount it

would have cost such person to attend the State

institution of higher learning and education to

which admission was denied or in which the

graduate or professional course or course of

study desired is offered. In determining the

comparative costs of attending the respective

institutions the Board shall take into considera

tion tuition charges, living expenses and costs of

transportation."

Notwithstanding the precepts of Missouri, ex rel

Gaines, v. Canada, 305 U.S. 337 (1938) , the General Assembly

of Virginia at its 1946 session enacted what is now Code

Section 23-173 which authorizes the State Board of Education

to contribute specified sums of money to the cost of educat

ing "properly qualified Negroes of Virginia" pursuing

medical and dental studies at Meharry Medical College,

Nashville, Tennessee.

Section 23-12 of the Code of Virginia requires the

4

.president of Virginia State College or someone designated by

him to administer these grant-in-aid programs and to report

annually to the State Board of Education. During the past

ten years the following amounts had been paid to black students

pursuant to the statute:

Year Amount Year Amount

1960-61 $185,000 1955-66 $233,525

1961-62 185,000 1966-67 190,362

1962-63 195,000 1967-68 190,746

1963-64 195,000 1968-69 70,510

1964-65 205,000 (PX #1, A through I)

The Annual Reports ■also reveal payment to the

Southern Regional Educational Board for contracts with

Meharry Medical College and Tuskegee Institute (In Tuskegee,

Alabama) (PX #1, A through I).

VIRGINIA STATE COLLEGE

Virginia State College, at Petersburg, first named

Virginia Normal and Collegiate Institute, was founded m

1882 pursuant to an Act of Incorporation approved by the

General Assembly of Virginia on March 6, 1882. From 1930 to

1946 it bore the name Virginia State College for Negroes

(Proposed Stipulation Number II, p- 1; #2 ' P* ^ ‘

During the period of 1954-1964, applications of

white students to attend Virginia State College simply were

not processed by the admission officials but were passed on

to the president of the college «.Tr. I, pp. 10 14) .

procedure was not discontinued until 1964 when the legisla

ture transferred the supervision of the college from the State

5

Board of Education to a Board of Visitors appointed by the

Governor (Tr. I, p. 4-5).

The first white faculty member was employed in

1964 (Tr. I, p. 49) and the first white students were enrolled

in 1965 (Tr. I, p. 12, 84-5). The number of white students

and white faculty members gradually increased until the 1970-71

year. The white faculty members now total 43 out of 255 (VSC-X

#6) and the white undergraduate student enrollment is 70 out of

1,926 (VSC-X #4).

RICHARD BLAND

Richard Bland College was established pursuant to

Chapter 56, Acts of the General Assembly, 1960, wherein it

is identified as the Division at Petersburg of the College

of William and Mary in Virginia. The two-year institution

which was established under the close supervision and direction

of William and Mary offered its first classes during the

1961-62 school year (Tr. Ill, p. 13).

Only 3 black students were enrolled in Bland in

1967 and 5 additional blacks were enrolled for the 1968-69

school year. The composition of its faculty and student

body by race for the past two years is as follows:

White

1969

Black % Black White

1970

Black % Black

Students 699 6 1.1 827 14 1.8

Faculty 50-60 0 0.0 50-60 0 0.0

(Carson's Answer to Interrogatory # !L; Tr. Ill, p. 47) .

According to its latest catalogue, Richard Bland

6

"serves the young people of Southside Virginia by offering

close to their homes the basic first two years of college in

the arts and sciences, as well as some approved advanced

courses"(PX #3, p. 7) c

Over 97.5% of the students attending Bland are

recruited from counties, cities and towns located within a

radius of 45 miles of the College. All of the students

commute from their homes to the college. (Paschall X #4; VSC

X #3) .

STATE AND .FEDERAL STUDY

AGENCIES AND THEIR RECOMMENDATIONS

State Council of Higher Education

In 1956, the General Assembly of Virginia created

the State Council of Higher Education for Virginia (herein

after referred to as the Council). The Council was charged

to:

"promote the development and operation of a

sound, vigorous, progressive, and coordinated

system of higher education in the State of

Virginia" (Code of Virginia, Section 23-9.3).

The Council was specificially charged to assemble

data and plans for coordinating the colleges into a system, to

limit the offerings of an instutition to conform to the

Council's plans, to review and coordinate budget requests of the

several institutions and to perform other related functions

indicated in Chapter 1.1 of Title 23 (§23-9.3 et seq) of the

Code of Virginia.

In addition Section 23-9.11 of the Code provides:

" (a) No State institution of higher learning

shall establish any additional branch or

7

division or extension without first referring

the matter to the Council for its information,

consideration and recommendation and without

specific approval by the General Assembly of

the location and type of such branch or

division;* * *.

" (b) No additional state-controlled institution

with the exception of new community colleges,

shall be established, nor shall any existing

institution presently limited by law to two-

year programs, nor any existing institution

presently limited to four-year programs, be

changed to a higher-degree level until a

study has been conducted by the State Council

of Higher Education concerning the need for

such an institution or development and the

presentation by the State Council of a report

and recommendations to the Governor and the

General Assembly."

The Council- consists of eleven able citizens selected

from the state at large who are enjoined by statute against

acting as representatives of their respective regions or of

any particular institution of higher education. This agency

operates through an Executive Director and his 25-member pro

fessional staff, the combined expertise of which embraces

practically every area of concern to college administrators.

(See Tr. II, p . 7 j .

In addition to its own staff, the Council utilizes

professlohal consultants to assist it in complying with its

statutory responsibilities (Tr. IV; pp.7-10). The staff

and also the Council make extensive use of advisory committees

consisting of professional educators and other individuals

to assist them in formulating recommendations and compiling

reports (Id.) Some of the committees consulted are committees

of the presidents of the institutions of higher learning, the

academic deans or vice-deans, the business officers, the

8

admissions personnel and the librarians of each institution

in the state (Tr. IV, pp. 9 and 23) .

The Council is constantly gathering and accumulat

ing data concerning the educational problems in Virginia, the

southern region and the nation and is the only agency in the

State with a broad and comprehensive view of the higher

educational resources and needs of the State (Tr. IV; pages

24,25) .

By Chapter 91 of the Acts of Assembly of 1964, the

legislature authorized the Governor to appoint a commission

"which shall be broadly representative of the public and of

higher education (including junior colleges and technical

institutions)" known as the Virginia Commission on Higher

Education Facilities,, (Code of Virginia §23.9.15). In

December of 1965, this Commission released its report (Tr. Ill,

p, 12) and eleven staff reports which had been prepared by its

professional staff, headed by John Dale Russell (Tr. Ill, p.

13; PX #10-pp = 55-56).

Although in its said reports this Commission

supported the expansion of Christopher Newport College (of

William and Mary) and George Mason College (of the University

of Virginia) to four year status, it refused to support the

escalation of Bland) Instead, it recommended that Richard

Bland and all of the other two-year colleges in the state be

made a part of the community college system (PX #10-p. 40;

Tr. Ill, pp. 18-19).

In December of 1967, the State Council of Higher

9

Education released "The Virginia Plan for Higher Education"

as a guide for the development of higher education in the

Commonwealth during the decade 1967-77. This plan was

designed to "promote maximum utilization of present and

future resources" (PX #10, p. 5).

The Virginia Plan discussed the problems existing

in higher education in Virginia, set forth five broad goals

charting the future of higher education in Virginia and

identified eleven components considered basic to a statewide

plan of higher education (PX #10).

In component IV, after giving careful study to

the present role of each institution and to the future

developments proposed by each institution, the council

spelled out "the role and function it considered appropriate

for each of the several state institutions for the next ten

years"(PX #10, p. 25).

With respect to Richard. Bland and three other

existing two-year colleges, the plan stated:

"The Higher Education Study Commission in its

1965 report to the Governor and General Assembly

recommended■that these branch colleges of senior

institutions be incorporated into the state

system of community colleges,, The State Council

of Higher Education concurs in this role for

these institutions," (PX #10, p. 40).

The proposals in the Virginia Plan were reaffirmed

in late 1967 or early in 1968 when the State Council made its

1966-68 Biennial Report to the Governor and the General Assembly.

"[T]he State Council considers [the Virginia Plan

and its eleven components] of critical importance

to the future of higher education in the Common

wealth. The Council believes its Plan will pro

mote the flexibility which has characterized

10

Virginia higher education, preserve the indivi

duality of the several colleges and universities

in the state system, and provide a sound and

progressive program of higher education for the

future." (PX #14 (e), p. 42).

These proposals were again reaffirmed in the 1968-70

Biennial Report which was transmitted to the Governor and

General Assembly in December of 1969. Listed first among

the Council recommendations for 1970-72 is the following:

"It is recommended that full support be given

to the implementation of higher educational

developments proposed in The Virginia Plan for

Higher Education. The State Council is convinced

that the . . . Plan . . . is a sound and realistic

guide by which the Commonwealth may achieve its

higher educational goals" (PX #14 (f), p. 4),

Pursuant to Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of

1964, the Department of Health, Education and Welfare (HEW)

requested the State of Virginia to submit a (state-wide) plan

to desegregate the higher education facilities of Virginia.

1/

Virginia's response consisted of an outline of its plan

(submitted m April, 1970) and "VIRGINIA'S STATE PLAN" (sub

mitted in December, 1970; for desegregating its institutions

of higher education (Tr. IV, p t 12, line 15; PX #4).

Although the plan was submitted by Governor Holton,

it was prepared in large part by the State Council of Higher

Education (Tr. II, p. 9, [lines 6-161). There is nothing in

the plan that was not approved by the State Council (Tr. II,

p. 9, [lines 18-20]).

The HEW officials were aware of the proposed

PX #9.

!

1/

11

escalation of Richard Bland. They discussed with Virginia

officials the problem of Virginia State College being an

overwhelmingly black institution and Richard Bland, a nearby

college, being all-white. The major concern was in the area

of the overlapping similar levels of degrees in the same pro

grams, the overlapping curriculum or the potential for duplica

tion, particularly if Richard Bland was escalated to a four-

year college (Tr, IV, pp, 31—32). 2/

The recommendations in the Governor's report

dealing with the Virginia State-Richard Bland situation were

designed to correct the problem of the' dual system of higher

education which exists in the Petersburg area (Tr. IV, p. 32-33).

Among the recommendations for 1971-72 academic year (Phase II)

is the introduction of legislation to place Richard Bland College

in the Community College System (PX #4, p,6).

OTHER CIRCUMSTANCES MATERIAL.

TO A CONSIDERATION OF THE PROPOSED

ESCALATION OF RICHARD BLAND COLLEGE

Both Virginia State College and Richard Bland

attract large numbers of students from the nearby counties

and cities. Of the 1,926 undergraduates enrolled at Virginia

State College, 1,099 reside within a 45 miles radius of the

campus (VSC X #1, #2, #4), Another 266 are residents of

the "Tidewater Cities", i.e., Norfolk, Portsmouth, Virginia

Beach, Hampton, Chesapeake and Newport News. Thus, over 70%

of the enrollment of Virginia State College comes from nearby

southside and from the seaport cities. Similarly, 97.5% of

2/

" PX #4.

- 12 -

Richard Bland's 1969 enrollment and 90.5% of its 1970 enroll

ment live within the 45 mile radius of Virginia State College

(Paschall X #4).

The following chart shows the extent to vhich Richard

predominantly

Bland College draws its / -white student enrollment from

specified localities within the forty-five mile radius. The

numbers of students from the several localities are shown on

a map filed as a part of PX #11 and captioned "Richard Bland -

Distribution of Virginia Students by county". The percentages

of blacks in the total populations of these localities are

calculated from figures reported in the 1960 Census.

Bland Black Percentage

Localities Students of Total Populatior

Dinwiddle and Peters-

burg

Prince George and

259 52.7

Hopewell

Chesterfield and

175 19.9

Colonial Heights 134 11.7

Greensville 22 54.8

Sussex 21 66.3

Henrico and Richmond 26 29.1

Mecklenburg 5 46.8

All other localities 63 “ “ “ “

Total enrollment 705

The entrance requirements at Virginia State College

and Richard Bland are similar. All of the courses offered at

Bland are duplicated at Virginia State (Tr. I, p. 99).

Virginia State offers many courses not offered at Bland (Id, p.99).

As was earlier indicated, only 70 of Virginia

State's undergraduate enrollment of 1,926 are white. At least

12 of these 70 students are transferrees from Richard Bland

(Tr. I, p. 32). Sixty of the 70 are commuting students who

13

live within the 50 mile area (Tr. I, p 5 28),

Both Bland and State recruit extensively from the

southside Virginia area (Tr. I, p. 70). During the past few

years Bland has done no active recruiting outside the south-

side Virginia area or the area contiguous to the college

(Tr. Ill, p. 133). Since 1965, Virginia State College has had

"an active and vigorous policy in the recruitment of white

students" to attend the college (Tr. I, p. 69). Many of the

prospective white students and their parents inquired concern

ing the number of white students and faculty members at Virginia

State (Tr. I, p = 62).

Richard Bland, which since its inception has had

an all-white faculty and staff, has historically sought the

attendance of white students. Its first expression of interest

in black students appears in a letter dated April 28, 1970,

(McNeer X #3) from its Director of Admissions, addressed to

certain principals of high schools in the area.

In February of 1966, the Beard of Visitors of

William and Mary adopted a resolution regarding the status

of Bland and Newport. The statement acknowledged the recommen

dation of the Higher Education Commission and suggested that

any legislation purporting to escalate either or both of these

colleges to four-year status "should avoid specifying time

for same", but that this determination should be left to the

Board of Visitors. The Resolution indicated that "available

resources and academic considerations" are not sufficiently

known with certainty to project wisely such a time period

14

within the next two years (Paschall X #1). The proposal, thus

rejected, to escalate Bland and Christopher Newport had been

triggered in part by resolutions of the governing bodies of the

jurisdictions near the respective colleges and the expressions

of white citizens from the respective areas (Tr. in, p . 59) #

The next action taken by the Board of Visitors of

William and Mary with respect to Richard Bland was in December

of 1969 and early in 1970 when the Board made an assessment of

Richard Bland (Tr. in, p. 24). The assessment was made by

officials of William and Mary and Bland exclusively and con

sisted of visitations to check on library resources, to check

on faculty potential and population enrollment to be served, a

check on the report of the Southern Association and a considera

tion of the academic program (Tr. Ill, pp. 55-56). No written

report of the assessment was made.

No inquiry was made to determine the availability

of space and other resources at Virginia State College and

other four-year colleges in the area although the officials

were aware of the fact that such institutions existed

(Tr. Ill, p. 5/). The officials did not even consider any

other four-year institutions. They felt that their "role was

to exercise stewardship for Richard Bland and its future and

what was best for it." (Tr. Ill, p. 57).

In the assessment of Bland, the Board "gave con

sideration to several pertinent factors that led the Board

to adopt a resolution in February, 1970, declaring that

Richard Bland was to be escalated . . . and directing that

15

the House Appropriations Committee be notified of the additional

resources needed, the General Assembly then being in session."

(Tr. Ill, p. 24).

The justification offered in the resolution for the

decision to escalate Bland was :

"* ‘ • the Board is of the opinion that Richard

Bland College can best serve the present and

future educational needs of its rapidly

growing geographic area if it is developed

to the level of a four-year degree—granting

institution." (Paschall X #2).

The presidents of William and Mary and Richard

Bland testified before the Appropriations Committee of the

House of Delegates in favor of the escalation of Bland

(Tr. Ill, p. 25). However, the chairman of the State Council

of Higher Education and its Director testified against the

proposed escalation (Tr. IV, p. 34).

The General Assembly of Virginia enacted the

appropriations bill for the biennium beginning July 1, 1970,

(Acts of Assembly 1970, Chapter 461), Item 600 of which pro

vides $420,625 during the first year and $558,304 during the

second year for "Operating expenses of educational and general

activities of Richard Bland College, at Petersburg, "includ

ing escalation to third and fourth year status."

THE RACIAL PATTERN IN

VIRGINIA'S HIGHER EDUCATION SYSTEM

Virginia currently operates 15 four-year colleges

and universities and 16 two-year community colleges. In

16

there ere three two-year branches of the four —

year institutions (P-X #7). These 34 institutions have a

total student enrollment of 108,033 of which 11,810 or 10.9%

are black. Two of the four-year institutions, Virginia State

College and Norfolk State College, were established for the

education of black students, During the 1969-70 school year

(when this suit was instituted), 4,569 (98.4%) of the 4,644

students enrolled at Norfolk State were black and 2,589 (98.8%)

of the 2,675 students at Virginia State were black. Of the

total of 72,819 students enrolled in four-year colleges and

universities, 8,197 (11.3%) were black. The two "black"

colleges had 87.3% of the black students and Virginia Commonwealth

University had 6,3%. The remaining 523 (6.4%) were scattered

among the other 12 four-years colleges only one of which had

blacks accounting for as much as 1.5% of the school's enrollment.

In 8 of those schools, the black enrollment was less than 1%.

The picture is practically the same for the 1970-71

school year. Of the 5,202 students enrolled at Norfolk State,

5,082 (97.7%) are black; and 2,728 (92.5%) of Virginia State's

2,948 students are black. Of the total of 79,879 students

enrolled in four-year colleges and universities, 9,597 (12.2%)

are black. The two virtually all-black schools have 81.4% of

the black students and Virginia Commonwealth University has

10.8%. The remaining 7,8% (748) are scattered among the other

1/The Eastern Shore Branch of the School of General

Studies and Patrick Henry College (at Martinsville) are branches

of the University of Virginia and Richard Bland College (at

Petersburg) is a branch of the College of William and Mary.

17

12 four-year colleges, only two of which have blacks account

ing for as much as 1.5% of the school's total enrollment. In

6 of these schools, the black enrollment does not exceed 1%

(PX #7 and App. 1).

The total 1969-70 community college enrollment was

22,036. Of these 1,478 (6.2%) were black. For the 1970-71

school year, 2,162 (7.8%) of the total enrollment of 27,840

are black (PX #7 and App, 1).

At the three two-year branches, blacks numbered 24

(2.0%) of the 1,178 students enrolled during the 1969-70 school

year and 51 (3,9%) of the 1,314 students enrolled during the

1970-71 school year.

The complete breakdown of the enrollment by level

of institution and by race and a comparison of the 1969

enrollment with that of 1970 as shown in PX #7 is submitted

on Appendix I.

During the discussion between officials of the

State Council and HEW, the latter took the position that

the State has an affirmative duty to overcome the de jure

existing pattern in all of the institutions of higher

learning, particularly the pattern of student enrollment

(Tr. IV, pp. 33-34).

The Virginia report to HEW acknowledged that

"the historical patterns of racial segregation" in Virginia's

higher education system were "until recent years" maintained

under state law (PX #4, p. 1). The report contained several

statistical charts describing Virginia's higher education

18

system (Tables I through IV of PX #4). The report concludes

with a 3 year time table beginning with the 1970-71 year.

The report contains no numerical goals or any type

of goals which would change the racial makeup in the student

bodies or the faculties at the various institutions of higher

learning (Tr. IV, p. 12). Nor has the State Council formu

lated such goals. In fact, the State Council has taken no

steps to further desegregation beyond what is contemplated

by the report (Tr. IV, p. 12).

THE PARTIES TO THIS ACTION

On June 30, 1970, this litigation was instituted

by three different categories of plaintiffs:

(a) Three black high school students vAio expect to

attend college, each of whom resides in the City of Petersburg,

Virginia, and is a citizen of the Commonwealth of Virginia

and the United States;

(b) Three black students of Virginia State College

who are citizens of the Commowealth of Virginia and of the

United States; and

(c) Six instructors at and members of the faculty

of Virginia State College, two of whom (Florence Saunders

Farley and George W. Henderson) are black and the remaining

4/

4/

For an an accurate statement of the desegregation

status of Virginia's higher education system, see the dis

cussion on pages 1 and 2 of this brief and Appendix I, infra.

19

four are white. Each is a citizen of the United States and

of the Commonwealth of Virginia.

The suit named as defendants the State Council of

Higher Education for Virginia, A. Linwood Holton, Governor

of Virginia, The Board of Visitors of the College of William

and Mary in Virginia, James M., Carson, President, Richard

Bland College, and the Visitors of Virginia State College.

A R G U M E N T

I

The Special Three-Judge

Court Is Without Jurisdiction

No statute requires the maintenance of the racially

dual system of higher education. Primarily, the plaintiffs

seek an order restraining the enforcement, operation or

execution of Item 600 of the Appropriation Act (Acts of

Assembly 1970, Chapter 461) purporting to authorize "escalation

[of Richard Bland College] to third- and fourth-year status."»•

The subject biennial appropriation reads as follows:

II

" * * * First year Second year

II

"Richard Bland College,

at Petersburg

"Item 600

"Operating expenses of

educational and

general activities

including escalation

to third- and fourth-

year status --------- $420,625 $558,305

Item 600

* * * »

Clearly, Item 600 of the Appropriations Action is not of state

wide application,

20

In their motion to reconsider the question of convening

a three-judge court, the defendants suggested that the plaintiffs'

prayer for merger of Richard Bland College into Virginia State

College calls into question the constitutionality of Chapters

5 and 13 of Title 23 of the Code of Virginia. Section 23-49.1

(of Chapter 5) vests in the board of visitors of the College of

William and Mary the supervision, management and control of

the Richard Bland College in Petersburg. Chapter 5 (sections

23-165, et seq) which prescribes the powers and duties of The

Visitors of Virginia State College, does not purport to deal

with the supervision, management and control of the Richard

Bland College.

But these statutes (Chapters 5 and 13) also fall

short of state-wide application; and the facets of the statute

which would be affected by the plaintiffs' prayer for merger

fall even shorter. Chapter 5 deals with but 3 of the 34 state

colleges and universities and those 3 are located in the south

eastern corner of the state. Section 23-168 having been

effectively repealed by Chapter 13.1 (§§23-174.1 and 23-174.9),

Chapter 13 deals with but one institution which is also located

in the southeastern corner of the state,

The purpose of 28 UoS.C. §2281 is to prevent a

single federal judge from being able to paralyze totally the

operation of an entire regulatory scheme, either state or

5/

federal, by issuance of a broad injunctive order. In keeping

Kennedy v. Mendoza-MartInez, 372 U.S. 144, 82 S.Ct.

554 (1963).

5/

21

with that purpose "[t]he Court has consistently construed the

section as authorizing a three-judge court not merely because

a state statute is involved but oniy when a state statute of

general and statewide application is sought to be enjoined".

Moody v. Flowers, 387 U.S. 97, 101, 87 S.Ct. 1544 (1967).

6/

Moreover, §2281 is to be narrowly construed because of the

burden three-judge courts place on the normal operations of

the federal courts. Those statutes that affect a particular

municipality or district, as is the case here, are not within

the limited class of cases for which §2281 was prescribed.

In Griffin v. School Board of Prince Edward, 377

U.S. 218, 228, 84 S.Ct. 1226 (1964), the Court held that it

was for a single district judge to adjudicate a controversy,

that "may have repercussions over the state", as to whether

county officials acting in Prince Edward County could be

enjoined from closing public schools and from giving public

funds including state funds to white children to attend pri

vate schools that excluded black children. The Court stated:

"Even though actions of the State are involved,

the case, as it comes to us, concerns not a

state-wide system, but rather a situation unique

to Prince Edward County".

In Moody v. F1owers, supra, Mr. Justice Douglas,

delivering the Court's unanimous opinion on the issue of a

three-judge court, held that a state statute dealing with

apportionment and districting of one county's governing board

pertained to matters of local concern and a county charter

Bailey v. Patterson, 369 U.S. 31, 82 S.Ct. 549

6/

(1962) .

22

enacted into state law providing that supervisors of a

particular county governing board each representing various

sized towns should each have one vote was similar to a local

ordinance, The Court held that neither situation required a

three-judge court since the statutes involved were not of

"general and state-wide application". (38 U.S. at 101).

In cases involving state statutes regarding city

7/

improvements, taxes assessed and collected for the sole use

8/ 9/

of a city, and the administration of a large drainage district,

the Court has consistently found a three-judge court inapplicable

since the nature of the controversy was legislation affecting

a locality as against a policy of state-wide concern, "Nor

does the section come into operation where an action is brought

against state officers performing matters of purely local con

cern," Moody Vo Flowers, supra at 102. See also Rorick v.

Board of Commissioners, cited in footnote 9. It should be noted

here that administrative orders trigger §2281 only when they are

of state-wide application representing considered state policy.

Hatfield v. Bailleaux (1961 C,A. 9 Or.), 290 F.2d 632, cert, den.,

368 U.S. 862 , 82 S.Ct. 105.

In this case, as in Griffin, state funds and a state

7/

Ex parte Collins, 277 U.S, 565, 48 S.Ct. 585 (1927).

8 /

~ Petition of Public National Bank of New York, 278

U.S. 101, 49 S.Ct. 43 (1928).

9/

Rorick v. Board of Commissioners, 307 U.S, 208, 50

S.Ct. 808 (1938).

23

statute are being directed toward a specific situation in one

locality, namely the expansion of Richard Bland College at

Petersburg. When the Supreme Court has been confronted with

the issue of whether a three-judge court is warranted it has

in the cases cited above conclusively and clearly stated that

a three-judge court need not be invoked whenever "a state

statute is involved but only when a state statute of general

and state-wide application is sought to be enjoined". Moody

v. Flowers, supra. The defendants base their motion for a

three-judge court on Alabama State Teachers Ass'n. v. Alabama

Public School and College Authority, 393 U.S. 400 (1969) , a

memorandum case that did not consider the propriety of the

hearing before three judges. The Supreme Court in Petition

of Public National Bank of New York, supra, provided the best

answer to the defendants’ reliance on Alabama when it stated:

"It is enough to say, as was said in the Collins

Case, that the propriety of the hearing before

three judges was not considered in the cases to

which we are referred, and they cannot be regarded

as having decided the question." (278 U.S. at 105).

II

The Fourteenth Amendment

Forbids The Maintenance Of A 10/

Racially Dual System Of Higher Education

The principle that racial discrimination by the state

in higher education violates the Fourteenth Amendment was well

10/

Except for the change of one word in this headnote,

this argument (II) is lifted verbatim from the Brief of the

United States recently filed in the United States Court of

Appeals for the Fifth Circuit in Anthony Lee, et al vs. Macon

County Board of Education, et al, wherein the Government seeks

affirmance of orders of the District Court entered on August 14,

1970, October 13, 1970 and October 26, 1970.

24

I

established prior to the decision in Brown v. Board of

Education, 347 U.S. 4 83. Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada,

305 U.S. 337 (1938) ; Sipuel v. Beard of Regents, 332 U,S. 631

(1948); Sweatt v = Painter, 339 U.So 629 (1950); McLaurin v.

Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U S. 637 (1950), The decision in

Brown itself was promptly extended to higher education. Florida

ex rel. Hawkins v. Board of Control, 350 U.S. 413 (1956) .

Racial discrimination in public education may take

the form of discriminatory denial of admission to a public

school, as m Brown and Hawkins, or it may take other forms,

such as the maintenance of the dual system in New Kent County,

Virginia. Green v. County School Board, 391 U.S. 430 (1968).

In either event it is forbidden by the Fourteenth Amendment.

Although most higher education cases have involved discrimina

tory admissions policies, all cases dealing with the question

hold that the state may not operate a racially dual system

of higher education. Alabama State Teachers Association, et

al, Vo Alabama Public School and College Authority, et al.,

289 Fo Supp 784 M 0 Ala * (tnree-judge panel, Gewin, Circuit

Judge, Johnson and Pittman, District Judges) aff'd without

argument, 393 U.S 400 (1969}; Sanders v.. El lington, 288 F.

Supp. 937 (m D Term-, 19681; Lee v„ Macon County Board of

Education, 267 F. Supp. 458 , 4 74 (M.D Ala.) (^liree-judge

panel, Rives, Circuit Judge, Johnson and Grooms, District

Judges) aff* 1d sub nom. Wallace v. United States, 389 U.S. 215

(1967). Stated another way, the state may not maintain one

set of schools intended to serve white students and another

l

to serve black students.M As with elementary and secondary

25 -

education, the system of higher education must be one "without

a 'white' school and a 'Negro

Green v, County School Board,

school, but just schools."

supra at 442.

26

Ill

The Racially Dual Character Of The System Of

Higher Education Has Not Been Disestablished

Notwithstanding Virginia's affirmative obligation to

eliminate the racially dual pattern of student enrollment in

its institutions of higher learning, this record shows that

Virginia has operated its institutions of higher education as if

the requirements of Brown v. Board of Education, supra, were

satisfied by the admission of a few black students to white

institutions.

During the 1969-70 school year, all 15 of the four-

11/

year institutions had racial minorities of less than 4%.

Twelve of the 15 institutions had racial minorities of less than

3% and 8 had minorities of less than 1%.

For the 1970-71 school year, all but 3 of the four-

year institutions still had racial minorities of less than 4%.

Ten of the remaining 12, had minorities of less than 1.5%. The

overall percentage of black students was 12.2 percent (App. I).

Equally as important is the continuation of the

historical pattern of racially segregated assignment of faculty

members. The State Council has not requested records from the

various institutions showing the racial make-up of the faculties,

although such information can be secured from these institutions

(Tr. 11, p. 16). Notwithstanding inquiry from HEW officials

11/ The three two-year branches had black percentages of

1.1, 1.5 and 4.1. See App. I.

27

concerning faculty desegregation, the State Council has made no

effort to effect any change in the dual racial patterns of

faculty assignment (Tr. IV, p. 12). Even now, neither William

and Mary nor Bland has a single non-white person on its staff.

The perpetuation of the racially segregated character

of Norfolk State College (97.7% black) within a few miles of

Old Dominion College (98.6% white) is living proof of the

state's failure to disestablish the dual pattern of its higher

education system (See App. I). Virginia State College is 92.5%

black. At least 81.4% of all black college students at

Virginia's four-year institutions are attending Virginia State

and Norfolk State.

The fact that black students are no longer denied

admission to Old Dominion and white students are no longer

denied admission to Norfolk State does not end the inquiry.

"The law is clear that there is an affirmative duty . . . to

formulate and put into effect a desegregation plan which

'promises realistically to work now,' Green v. New Kent County,

391 U.S. 430 (1968)." See also Sanders v. Ellington, 288 F.

Supp. 937 (M.D. Tenn. 1968), where the (single Judge) district

court found that the State of Tennessee was maintaining a dual

system of higher education throughout the state and that there

is an affirmative duty upon the state to dismantle this dual

system (citing Green). More specifically, the court held that

an open door policy "does not discharge the affirmative duty

imposed upon the state by the Constitution, where, under the

policy, there is no genuine progress toward desegregation, and

no genuine prospect of desegregation". 288 F. Supp. at 942.

28

IV

Richard Bland Was Created To Serve White

Students Who Reside Within Commuting Distance

Of Virginia State College

The primary responsibility for the establishment of

Richard Bland has been exercised by Dr. David Y. Paschall,

President of William and Mary, with the guidance of the Board of

Visitors of that institution. During the past 10 years since

Dr. Paschall has been its president (as during the entire 17

years since Brown), William, and Mary has maintained an incredi

ble degree of racial segregation; viz:

In a total student enrollment of 5,319 only

45 are black. In a total undergraduate en

rollment of 3,300 only 5 or 6 are black. In

a total faculty and administration of 375,

none are black (Tr. Ill, pp. 44-46). Such

is the present box score at the College of

William and Mary.

The selection and the continuing replenishment of the

all-white faculty and administration of Bland has been under the

guidance and supervision of William and Mary. The active re

cruiting of white students from areas with large black populations

for the past ten years has been under the direction of William

and Mary. The virtually all-white enrollment of Bland 10 years

after its commencement is a direct result of the practices of

the William and Mary and Bland officials. Bland currently has a

student enrollment of 827 white and 14 black and an all-white

faculty totalling from 50-60 persons (Tr. Ill, p. 47).

Although the catalogue states that Bland's purpose is

to serve the "young people of southside" the total effect of the

29

Bland appeal is to the "white" students of the area. As stated

in Kier v. County School Board of Augusta County, 249 F. Supp.

239 (1966) at 245:

"[T]he presence of all Negro teachers in a

school attended solely by Negro pupils in

the past denotes that school a 'colored

school' just as certainly as if the words

were printed across its entrance in six-inch

letters."

Bland's statements of non-discrimmatory policy are

suspect. Although the admissions officer testified that the

application for admission to Richard Bland College (McNeer X #2)

contains a statement of non-discrimination (Tr. Ill, pp» 105-106),

he admitted on cross-examination that the application had only

been printed within the past month and that none of the prior

application forms had any statements which would indicate a

non-discriminatory admissions policy at Richard Bland (Tr, III,

pp„ 118-119), The admissions officer also disclosed that the

current Richard Bland College catalogue (McNeer X #1) is the

first to have a statement expressing a non-discriminatory ad

missions policy (Tr, III, p. 117), Moreover, he admitted that

he had never discussed Richard Bland with a olack parent (id °,

p. 143).

The organizational structure and the appeal of Bland

was designed to capitalize on the mores of the community in

which Bland was located. In the words of Dr. Wendell P. Russell

(president of Virginia State College):

" * * * [W]e have a fairly well-established

pattern of behavior that says whites go

to white schools and blacks go to black schools,

30

and with the exception of particular situations

and changes which have been brought about, from

generally outside the community, these patterns

remain»

"To translate this to Richard Bland, what I have

been trying to say is that Richard Bland has been

established as a predominantly white institution

and Virginia State as a predominantly black

institution.

"Now, the escalation of Richard Bland is going

to mean that you have again established a com

pletely four-year predominantly white institution.

Virginia State then remains a predominantly black

•institution. There is little chance within this

geographic area for there to be any possibility

of breaking through this pattern of behavior."

(Tr, I, pp. 101-102.)

It is fairly obvious that there are intense social

pressures on white parents against sending their children to

predominantly black Virginia State College, especially where

there is a predominantly white Richard Bland right in the area

(Tr. I, p. 10 2).

In response to gentle pressure from HEW and to this

litigation, Richard Bland has made a few token moves to alter

its image.

V

The Proposed Escalation Of Bland Is Without

Sound Educational Purpose

The asserted justification for the escalation of

Richard Bland is William and Mary's opinion that "Richard Bland

College can best serve the present and future educational needs

of its geographic area if it is developed to the level of a

four-year degree granting institution".

31

The assessment— to determine if Bland should be

escalated— was made only by William and Mary and Bland officials.

12/

Inasmuch as it has stewartship over Bland, William and Mary

was in effect passing judgment on its own efforts.

All of the educational expertise marshalled by the

various independent state councils, their professional staffs,

their consultants and their advisory committees gave careful

attention to the higher education problems of the Petersburg

area and they all opposed the escalation of Richard Bland. In

addition, the expertise of the HEW officials was also arrayed

in opposition to the escalation. Their main reason as set out

by Dr. McTarhaghan is that it would be educationally unsound to

overlap similar levels of degrees in the same area.

"[Tjhe reasons were . . . because of the size

of the current institutions in the state and

the ability of existing institutions [Virginia

State (four-year) and John Tyler (two-year)] to

expand to accommodate and the anticipated

enrollment growth„" (Tr. II, p , 37 .)

Moreover, the assessment made by William and Mary was

incomplete and inadequate, Only the resources of Richard Bland

were examined, No attempt was made to examine the resources and

strengths of the existing four-year institutions serving the

area. Virginia State, the institution considered by the state

and federal agencies as the four-year institution best capable

of meeting the needs of the area, was not even considered (Tr.

Ill, pp. 55-57).

12/ Dr. Paschall also testified that William and Mary felt that

it had responsibility for meeting the higher education needs

of southside Virginia (Tr. Ill, pp„ 85-86).

32

It is obvious that two competing four-year institutions

with overlapping programs in the same area would require con

siderably more financial outlay than would one and that neither

of them would receive as much as it would if it were there

alone, (Tr. I, p. 104.) Hence, it is imperative thac, in order

to meet the higher educational needs of all students in the

region, the existing four-year institution which is capable of

meeting those needs should be strengthened.

VI

The Proposed Escalation Of Bland Is Without

Constitutionally Acceptable Justification

The question posed here is whether, in view of its

affirmative duty to disestablish its dual higher education

system, Virginia can establish two schools, one black and one

white, serving the same geographic area and offering the same

program. In its motion to dismiss, the state argues that free

choice would satisfy the state's constitutional obligation.

That argument is grounded on the decision m Alabama

State Teachers Association v. Alabama Public School and College

Authority, supra. The Court in Alabama noted that the two

colleges involved had two distinct and separate educational

programs. One of the institutions placed emphasis on the

education of teachers, whereas the other one stressed liberal

arts. In the instant case, however, the escalation of Richard

Bland to a four-year school alongside the existing four-year

college at Virginia State would be duplicating at Richard Bland

33

a part of the curriculum which is presently available at Virginia

State, No justification can be perceived for the proposed

escalation except making available for white students a

"separate" educational facility.

Significantly in Alabama, the school to be expanded—

Auburn— had the wider breadth of courses and higher admission

standards and would therefore be more suitable for expansion.

Here, the situation is quite dissimilar. In Alabama there was

some evidence that the preference for Auburn's offerings over

those of Alabama State was based on educational rather than on

racial grounds inasmuch as the College Authority had rejected

an offer to operate the new program from Troy State University,

a white institution which like Alabama State had an inferior

status. Here the evidence excludes every justification but

race .

In Bradley v. Board of Public Instruction, (U.S.D.C.

M.D. Fla. C.A. No . 64-98, 1965) the Court ordered Gibbs Junior

College (a black institution in St. Petersburg, Florida) and

predominantly white St. Petersburg Junior College placed under

the same administration; it was held that Gibbs should be grad

ually phased out of existence because a new branch of

St, Petersburg Junior College was being constructed in

Clearwater, ten miles away. The court found that both junior

colleges had racially non-discriminatory admissions policies,

but that Gibbs' facilities were inferior. The consolidation was

ordered because if three junior colleges existed in the same

34

commuter area, blacks would probably continue to attend Gibbs,

and the two branches of St, Petersburg Junior College would

probably be predominantly white.

VII

The Escalation Of Bland Should Be Enjoined

In the years ahead, a large number of commuting

students (of both races) in the geographic area served by

Virginia State and Richard Bland will be entering college. Many

of the graduates of the four new two-year community colleges

located in the area will be seeking a four-year institution to

complete their requirements for a bachelor's degree.

These students should not have to choose between a

virtually all-white institution and an overwhelmingly predomi

nantly black institution. Such would be the choice if Bland is

permitted to escalate.

The state may not maintain one set of schools intended

to serve white students and another to serve black students. As

with elementary and secondary education, the system of higher

education must be one "without a 'white' school and a 'Negro'

school, but just schools". Green v. County School Board, supra,

at 442.

The testimony of the persons familiar with the

geographic area indicated that it would be extremely difficult

to secure the attendance of many white students to Virginia State

College if Bland is escalated to four-year status.

3 5

The defendants contend that their obligation is met if

students in the area can choose between Bland and Virginia State.

In Sanders v. Ellington, supra, the district court found that

the State of Tennessee was maintaining a dual system of higher

education throughout the state and that there is an affirmative

duty upon the state to dismantle this dual system (citing

Green). More specifically, the court held that an open door

policy "does not discharge the affirmative duty imposed upon the

state by the Constitution, where, under the policy, there is no

»

Igenuine progress toward desegregation, and no genuine prospect

of desegregation". 288 F. Supp. at 942. In defining the duty

of the defendants in regard to the one traditionally clack

college operated by the state, the court said:

c . the one thing that is absolutely

essential is a substantial desegregation

of that institute by whatever means can be

devised by the best minds that the State of

Tennessee can bring to it." 288 F. Supp,

at 943,

VIII

Richard Bland Should Be Merged With Virginia

State Or Put In The Community College System

In Prayer C of the.r complaint, plaintiffs urge this

court to require the defendants to provide for the merger of

Richard Bland into Virginia State College, The evidence ad

duced herein supports that relief. Many witnesses testified

that even as a two-year institution Bland is competing with

Virginia State for students for the first two years of their

higher education and that the Bland program is a duplication

36

of that offered at Virginia State. See Bradley v. Board of

Public Instruction, supra, where merger of two junior colleges

were ordered. See also Sanders v„ Ellington, supra; and Green

v„ County School Board, supra.

The plaintiffs recognize the impressive educational

evidence recommending the transfer of Bland to the State

Community College System. The state's ten-year "Master Plan"

for Higher Education and "The Higher Education Study Commission"

report both made such a recommendation, and the State Council of

Higher Education still adheres to that view. j

Plaintiffs believe that this record clearly indicates

that although the State Council of Higher Education and the

other official bodies have done an excellent job in weighing all

of the other educational factors, they have completely failed to

take into account the state's affirmative obligation to take

steps which realistically promise to work to dismantle the dual

system.

In any event, this court should not permit Richard

Bland to be escalated into a four-year institution "separate"

from the traditionally black Virginia State College,

37

IX

The State Council ShouLd Be Required To

~Devise And Submit A Plan, Whereby The

Racial Identiflability Of State Supported

Colleges And Universities Will Be Eliminated

Prayer C of the Complaint requests this Court to

require the defendants "to provide for and effectuate the

racial desegregation of the several colleges and universities

maintained by the Commonwealth of Virginia . . . " That such

relief is proper has been shown by the cases cited herein. See

Sanders v. Ellington, supra; Green v, County School Board,

supra; Bradley v. Beard of Public Inst ruction, supr a,

The statutes of Virginia have designated the defendant

State Council of Higher Education for Virginia as the agency to

coordinate its system of higher education. Moreover, the

evidence has demonstrated that the State Council is the one

agency with the facilities, resources and expertise to prepare

a state-wide plan of desegregation. This Court should now order

that

/the State Count:' prepare and file a plan whereby each of

the institutions of higher learning will be desegregated; that

the plaintiffs be afforded an opportunity to take exceptions to

the plan, if they be so advised; and that any necessary parties

for the effectuation of such plan be brought before the Court

X

The Defendants Should Be

Required To Pay Costs AncT Reasonable

Attorneys" Fees To Plaintiffs' CounseJ

Here, the plaintiffs are seeking to vindicate federal

constitutional rights in the important area ot public higher

education, Once again, the State of Virginia and the officials

_ 38 _

C E R T I F I C A T E

I certify that copies of the foregoing brief were

mailed to R. D. Mcllwaine, III, Esquire, P. 0. Box 705, Peters

burg, Virginia 23803, counsel for Board of Visitors of William

and Mary in Virginia, et al; Edward S. Hirschler, Esquire, and

Everette G. Allen, Jr., Esquire, 2nd Floor, Massey Building,

Fourth and Main Streets, Richmond, Virginia 23219, counsel for

The Visitors of Virginia State College; William G. Broaddus,

Esquire, Assistant Attorney General, Supreme Court Building,

Richmond, Virginia 23219; and to the Honorable John D. Butzner,

Jr., Richmond, Virginia; the Honorable Walter E. Hoffman,

Norfolk, Virginia; and the Honorable Robert R. Merhige, Jr.,

Richmond, Virginia, members of Three-Judge Court, this 25th

day of January, 1971.

40

APPENDIX I

COMPARISON OF FALL 1969 HEADCOUNT WITH FALL 1970 HEADCOUNT

IN VIRGINIA STATE-CONTROLLED COLLEGES: GROWTH IN BLACK ENROLLMENT

1969 1969 % 1970 1970 °Z

Four-Year Colleges and

A l l Races

Universities:

Black Black All Races Black Black

C . Newport- 1,410 49 3 s 1,828 75 4.1

C l. Valle/ 746 3 0-4- 812 8 1.0

George Mason 1,925 5 0.3 2,456 16 0.7

Longwood 1,951 13 0 7 2,239 17 0.8

Madison 3,803 21 C 6 4,033 31 0.&

MWC 2,166 16 0 7 2,165 25 l .z

Norfolk State 4,644 4,569 98.4 5,202 5,082 97.7

Old Dominion 9,047 120 / . i 9,668 140 l . i

Radford 3,954 45 M 4,159 53 1.3

U. Va. 9,642 134 I A 10,695 240 2.2

VCU 13,853 516 3,7 14,211 1,039 7.3

VMI 1,142 7 o.e 1,130 13 l . l

VPISU 10,990 75 0-7 12,014 85 0.7

Va. St. 2,675 2,589 96.8 2,948 2,728 92.5

W&M 4,871 35 0.7 5,319 45 0.8

Total Four-Year

Two-Year Branches:

72,819 8,197 II. 3 78,879

*

9,597 l 2.2

Eastern Shore 132 2 1.5 118 5 A 2.

Patrick Henry 340 14 i . l 360 31 6 .6

Richard Bland 706 8 l . l 836 15 / .8

Total Branches 1,178 24 2.0 1,314 51 3.9

1969 1970

Black and Black and

1969 Other °7o 1970 O ther Vo

Community C o lleg es : All Races Minorities B lackA II Races M inorities Black

Blue Ridge 1,254 38 3 0 1,315 48 3.7

C entral V a . 1,456 150 10.3 1 ,664 131 7 .9

Dabney S . Lancaster 551 28 S . l 564 38 6 .7

D an v ille 1,301 141 10.8 1,664 239 >4.4-

Germ anna — — 383 49 1 2 .8

John Tyler 1 ,898 323 n o 1,852 385 2 0 .8

Lord Fairfax — — 566 40 7. 1

N ew River 394 9 2 3 637 26 4 .1

Northern V a . 7 ,6 2 9 311 4 .1 9 ,7 7 9 655 6 . 7

Southside V a . — —

1A

217 58 2 6 .7

Southwest V a . 838 12 899 20 2 . 2

Thomas Nelson 1,832 199 10. 9 2 ,2 0 4 362 I 6 A

Tidew ater 1 ,450 122 8 .4 1 ,849 252 13 - 6

V a . Highlands 232 4 1.7 561 32 5 .7

V a . Western 2 ,1 4 2 107 5.0 2 ,7 5 4 197 7 . 2

W ythev ille 1 ,059 34 3 .2 932 22 2 . 4 <

Total Community Co lleges 2 2 ,0 3 6 1,478 6.7 2 7 ,8 4 0 2 ,5 5 4 9 . 2

Less M inorities O ther than Black 111 0,5 392 I A

Black M inority Enrollment 1 ,367 6 1 % 2 ,1 6 2 7 . S

Total - A ll Institutions 96,033 9,588 10.0 108,033 11,810 / 0.9

N o te : A n alysis of data co llected from Virginia institutions, 1970.

>

A P P E N D I X I I

A. LIST OF INTERROGATORIES AND ANSWERS

1. Plaintiffs' Interrogatories to Defendants Visitors

of Virginia State College, Board of Visitors of

the College of William and Mary and James Carson,

President of Richard Bland College, served on

October 28, 1970.

2. Answers to Interrogatories served on William and Mary

College and James Carson received by plaintiffs in

November, 1970.

3. Answers to Interrogatories served on Virginia State

College mailed to plaintiffs on December 4, 1970.

B. TRANSCRIPTS

1. Transcript I (Tr. I) - Depositions of Elgin M. Lowe,

Mabel C. Mortcastle, Robert M.

Hendrick, Jr., James F.

Nicholas, Edwin L. Smith and

Wendell P. Russell (January 15,

1971)

2. Transcript II (Tr. II) - Depositions of Roy E.

McTarnaghan (January 15, 1971)

3. Transcript III (Tr. Ill) - Depositions of Davis Y.

Paschall and James B. McNeer

(January 18, 1971)

4. Transcript IV (Tr. IV) - Depositions of Roy E.

McTarnaghan (continuation of

Tr. II) (January 18, 1971)

C. LIST OF EXHIBITS

Plaintiffs

#1 - (A to I) Graduate Aid Fund - Annual Reports

#2 - Virginia State College Gazette

#3 - Richard Bland College Catalog

#4 - Virginia's State Plan Submitted by Governor to

HEW in December, 1970.

#5 - Table II (Expanded) of Plan Submitted by Governor

#6 - Report of Projected Number of Transfer Students

from Community Colleges to State Controlled

Four Year Colleges for 1971, 1972 and 1973

#7 - Comparison of Fall 1969 Head Count with Fall 1970

Head Count: Growth in Black Enrollment

#8 - Virginia Colleges and Universities - Fall 1970

#9 - Virginia's Outline of State Plan (for desegregation)

#10 - The Virginia Plan for Higher Education

#11 - Records of State Council of Higher Education Dealing

with Escalation of Richard Bland College

#12 - State Council of Higher Education - Degrees

Conferred

A. 1965-66

B. 1966-67

C. 1967-68

D. 1968-69

#13 - Virginia's State System of Higher Education Selected

Characteristics Degree Programs and Student Fees

A. 1966-67

B. 1967-68

C. 1968-69

D. 1970-71

#14 - Biennial Report of State Council of Higher Education

to the Governor and General Assembly

A. January 1960

B. September 1961

C. 1962-64

D. 1964-65

E. 1966-68

F. 1968-70

#15 - institutions of Higher Education in Virginia

A. For 1969-70

B. For 1968-69

Defendant Virginia State College

#1 - Document of City Print-Out

#2 - Document of County Print-Out

#3 - Map of Virginia (Showing 50 miles radius of

Petersburg)

#4 - Summary of Exhibits #1 and #2

#5 - January 11, 1971: Students who have transferred

from Richard Bland Community College for the

years 1965-1971

#6 - Virginia State College 1970-71 Breakdown Report

of Faculty (by race)

#7 - state Council of Higher Education for Virginia

Degrees conferred

#8 - State Council of Higher Education for Virginia -

System of Higher Education

Defendants William and Mary College and

James Carson, President of Richard Bland College

#1 - Paschall - Statement of Policy Regarding status

of Bland and Newport (February 11, 1966)

#2 - Paschall - Resolution: Escalation of Richard

Bland (February 9, 1970)

#3 - Paschall - Project Higher Education Enrollment in

Virginia: Fall 1972 and Fall 1977

#4 - Paschall - Geographical origins of Bland Students

#5 - Paschall - Geographical origins of C. Newport

Students

#6 - Paschall - Geographical origins of Clinch Valley

Students

#7 - Paschall - Geographical origins of George Mason

Students

#1 - McNeer - Richard Bland College Catalog, 1970-71

#2 - McNeer - Bland's Application for Admission

#3 - McNeer - Letter of April 28, 1970, to Principal of

Matoaca High School

- McNeer - Undated letter from Bland relative to

financial aid

#4

A P P E N D I X I I I

STIPULATIONS

PROPOSED BY PLAINTIFFS

1. Stipulation Number I

2. Stipulation Number II

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF VIRGINIA

Richmond Division

ETHEL M. NORRIS, etc., et al :

v. : CIVIL ACTION

STATE COUNCIL OF HIGHER EDUCATION : NO. 365-70-R

FOR VIRGINIA, et al :

STIPULATION NUMBER I

It is hereby stipulated and agreed by and between the

undersigned attorneys for the respective parties hereto as

follows:

A

That the infant plaintiffs Ethel M. Norris, Deborah

Farley and Brenda A. Cole are black and are citizens of the

United States and of the Commonwealth of Virginia and reside

in the City of Petersburg and that each of them is a high

school student and expects to attend college;

B

That the plaintiffs Portia N. Turner, Beverly R.

Mason, Claude Stevens and Laura Ann White are black and are

citizens of the United States and of the Commonwealth of

Virginia and are students at Virginia State College;

C

That the plaintiffs James D. Beck, Florence Saunders

Farley, George W. Henderson, Sam M. Moffett, Peter B. Nemenyi

and Carey E. Stronach are citizens of the United States and of

the Commonwealth of Virginia and that each of them is an

instructor at and a member of the faculty of Virginia State

College. Florence Saunders Farley and George W. Henderson are

black and the other named faculty members are white.

Of Counsel for Ethel M. Norris, et

al, Plaintiffs

C Counsel for the Board of Visitors

of the College of William and Mary

in Virginia

Of Counsel for The Visitors of

Virginia State College

Of Counsel for State Councel of

Higher Education for Virginia, et

al

Approved, , 1971

2

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF VIRGINIA

Richmond Division

ETHEL M. NORRIS, etc., et al :

V. : CIVIL ACTION

STATE COUNCIL OF HIGHER EDUCATION : NO. 365-70-R

FOR VIRGINIA, et al :

STIPULATION NUMBER II

It is hereby stipulated and agreed by and between the

undersigned attorneys for the respective parties hereto as

follows:

A

That Virginia State College, at Petersburg, first

named Virginia Normal and Collegiate Institute, was founded in

1882 pursuant to an Act of Incorporation approved by the General

Assembly of Virginia on March 6, 1882 and that it bore the name

Virginia State College for Negroes from 1930 to 1946;

B

That the Commonwealth of Virginia maintains fifteen

(15) four year colleges or universities or divisions thereof,

viz :