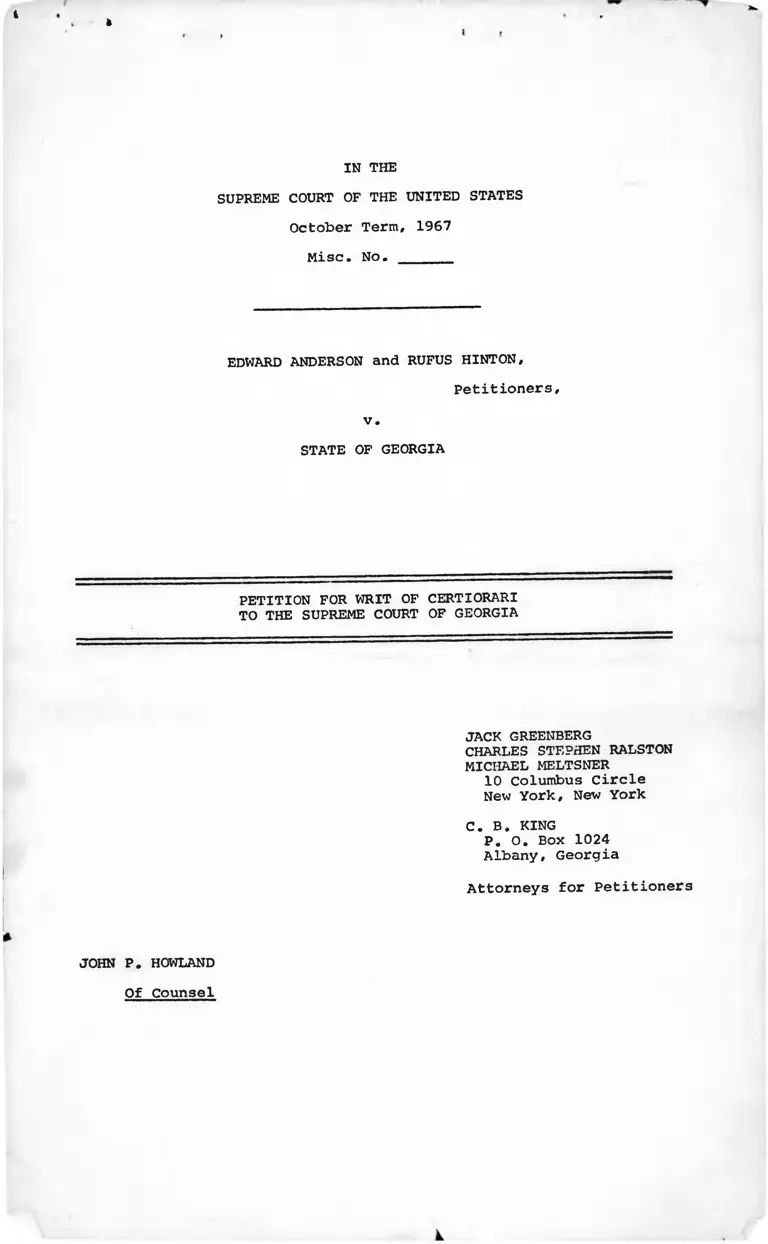

Anderson v. Georgia Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Georgia

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1967

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Anderson v. Georgia Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the Supreme Court of Georgia, 1967. 12c2f1c2-b79a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/bf5d571c-749d-4f9e-b81c-94fe4f6041db/anderson-v-georgia-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-supreme-court-of-georgia. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

t ft

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 1967

Misc. No. ______

EDWARD ANDERSON and RUFUS HINTON,

Petitioners,

v.

STATE OF GEORGIA

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE SUPREME COURT OF GEORGIA

JACK GREENBERG CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

MICHAEL MELTSNER10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

C. B. KINGP. O. BOX 1024

Albany, Georgia

Attorneys for Petitioners

JOHN P. HOWLAND

Of Counsel

I N D E X

PAGE

Citation to Opinion Belov;------------------------------

Jurisdiction-- ----------------------— ~

Questions Presented---- ------—— ------------

Constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved-------

S t a t ement------ ---- -------— — ---------------

How the Federal Questions Were Raised and Decided Belova

REASONS FOR GRANTING TKE WRIT:

I. THE DECISION OF THE SUPREME COURT OF GEORGIA

CONFLICTS WITH THIS COURT'S DECISION IN

WHITUS V. GEORGIA----------- ------- *-------------

II. THE DECISION UPHOLDING THE EXCLUSION FROM JURIES

OF PERSONS SOLELY BECAUSE OF THEIR ECONOMIC STATUS

CONFLICTS WITH PRINCIPLES DECLARED 3Y THIS COURT

AND WITH DECISIONS OF THE FIFTH CIRCUIT----------

CONCLUSION------------------------ *----------------------

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases:

Bostick v. South Carolina, 386 U.S. 479------ -Brookins v. State, 221 Ga. 181, 144 S.E.2d 83 (1965)-

Brown v. Allen, 344 U.S. 443--------------

7

8

15

Douglas v. California, 372 U.S. 353

Fay v. New York, 332 U.S. 261-----

Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 U.S. 335-

Griffin v. Illinois, 351 U„S. 12—

13

15

13

13

Harper v. Virginia State Board of Elections, ^ ^

383 U.S. 663--- --------------------------------------- - 14

Labat v. Bennett, 365 F.2d 698 (5th Cir. 1966) -11# 12, 14, 15

Reece v. Georgia, 350 U.S. 85---- ---------- ~ “ “ °

Smith v. Texas, 311 U.S. 128 (1940)--------------------- “ J-4Speller v. Allen, 344 U.S. 443 (1953)---------------------- 12

Spencer v. Texas, 385 U.S. 554, — —— — — - •

Swain v. Alabama, 380 U.S. 202— — -- 9# 10

Thiel v. Southern P. Co., 328 U.S. 217— - --— — —11, 14, 15

United States ex rel Goldsby v. Harpole, 263 F.2d 71

(5th Cir. 1959)------------------------

Whitus v, Balkcom, 333 F.2d 496 (5th Cir. 1964)----

Whitus v. Georgia, 385 U.S. 545----- *--------------

Williams v. Georgia, 349 U.S. 375---- —

ii

PAGE

Statutes:

28 U.S.C. § 1257(3)— ---------------------

Ala. Code Ann., Tit. 30 § 21 (Recomp. 1958)

Del. Code Ann., Tit. 10 § 4504 (1953)-----

Ga. Code Ann.:

§

§

§

§

§

§

§

§

§

§

§

§

§

§

26-7202----

59-106-----

86-1210-------

92-101-----

92-111-----

92-130-----

92-201-- —

92-219-----

92-239— —

92-3101----

92-3210----

92-3706----

92-6305---

92-6307----

2, 3, 7, 8, 11,

$

2. 3,

3

13

3

1212

13

13

1313

12

12

12

12

7

Ind. Ann. Stat. § 4-3317 (Supp. 1966) 11

Mont. Rev. Codes Ann. § 93-1402 (1964) 12

N.Y. Judiciary Law § 504(3) (Supp. 1965)

Tex. Rev. Civ. Stat. art. 2133 (1964)--

W. Va. Code Ann. § 5262 (1961)-----

H.B. 307, Georgia Legislature (1967)

Other Authorities:

45 Mich. L. Rev. 262 (1947)—

26 Tex. L. Rev. 533 (1948)—

United States Census (I960)—

33 Va. L. Rev. 519 (1947) —

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 1967

Misc. No. ______

EDWARD ANDERSON and RU^US HINTON,

Petitioners,

v.

STATE OF GEORGIA

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE SUPREME COURT OF GEORGIA

Petitioners pray tliat a writ of certiorari issue to review

the judgment of the Supreme Court of Georgia entered in the above'

entitled cases February 23, 1967, rehearing denied March 9, 1967.

(Time to file petition for writ of certiorari has been extended

to and including July 7, 1967.) In the trial court, the Superior

Court of Crisp County, the same evidence was entered in both

cases relating to jury discrimination. The cases were briefed

together in the Supreme Court of Georgia and that court entered

a single opinion in both cases. The two cases present the same

questions and review is sought here by a single petition for

certiorari as authorized by Supreme Court Rule 23 (5).

Citation to Opinion Below

The opinion of the Supreme Court of Georgia is reported

at 154 S.E.2d 246 (1967). It is set out in Appendix A, infra.

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Supreme Court of Georgia was entered on

February 23, 1967 (R. A. 111-121? R. H. 241-250),"" and motion

1/ There is a separate certified record from the Supreme Court

of Georgia for the case of each petitioner. Throughout this

petition "R. A." refers to the Record in the Anderson case and

"R. H." refers to the record in the Hinton case.

for rehearing was denied on March 9, 1967 (R. A. 130; R. H. 259)*

An extension of time for filing a petition for writ of certiorari

was granted by Mr. Justice Black to and including July 7, 1967.

Jurisdiction of this Court is invoked pursuant to 28 U.S.C.

§ 1257(3), petitioners having asserted below and assert here the

deprivation of rights, privileges and immunities secured by the

Constitution of the United States.

Questions Presented

Under Georgia law, the grand juries which indicted petitioners

and the traverse juries which convicted them were drawn from lists

compiled from tax digests segregated according to race and from

which persons with property less than a certain amount were

excluded.

1. Were petitioners, who are Negroes, denied due process

and equal protection of the laws by being indicted and tried by

juries selected from segregated tax digests and hence by juries

from which Negroes had been systematically excluded?

2. Were petitioners, who are indigents, denied due process

and equal protection of the laws by being indicted and tried by

juries from which persons with insufficient property to be on tax

digests were excluded?

constitutional and Statutory Provisions Involved

These cases involve the Fourteenth Amendment to the Consti

tution of the United States.

These cases also involve the following sections of the

Georgia Code Ann., which are set out in full in Appendix B,

infra?

§ 59-106;

§ 92-101;

§ 92-130;

§ 92-201;

§ 92-219;

§ 92-239;

§ 92-6307.

2

STATEMENT

In March 1966 a group variously estimated to be from 175

to 300 persons assembled in the front of the courthouse of Crisp

County, Georgia (R. A. 46, 56, 62). The persons were Negroes

who had gathered to protest conditions in the Negro community,

including segregated schools and poor street conditions in Negro

neighborhoods (R. H. 209). Petitioners were among the group.

Petitioner Hinton testified at his trial that he decided, as a

symbol of mourning over the conditions of Negroes in Crisp County,

to lower the United States and the State of Georgia flags at the

courthouse to a position of half mast (Ibxd.). In the process,

unidentified persons pulled the flags from the ropes, and the

eyelets by which the American flag was fastened to the rope were

torn (R. A. 58-60, 61-64; R. H. 156, 166, 173, 209). Petitioners

subsequently were indicted under §§ 26-7202 and 86-1210, Georgia

Code Ann. for defacing, mutilating and contemptuously abusing the

flags of the United States and the State of Georgia.

Prior to trial petitioners filed motions to quash the indict

ments and to challenge the traverse jury panel from which the

jurors were to be selected to try the cases (R« A. 11—18; R. H.

10-17). The motions challenged §§ 59-106 and 92-6307, Ga. Code

Ann., the statutes establishing the method for selecting juries,

on a number of grounds: (1) § 59—106 set up a property quali

fication for jury service in limiting it to persons possessing

sufficient property to be placed on the Georgia Tax Digest;

(2) the standards provided to guide the jury commissioners in

selecting the jurors were too broad and indefinite; (3) the two

statutes violated the due process and equal protection clauses

of the Fourteenth Amendment in that they required that Negroes

and whites be listed separately on the tax digests, and hence

permitted the jury commissioners to consider race in the selection

of jurors. Petitioners also charged that Negroes had been system

atically excluded from the grand and traverse juries as a result

of the statutes and the practices of the jury commissioners.

— 3 —

At the hearing on the motions to quash and to challenge the

array, the following was put into evidence: according to the

United States Census reports for 1960, the total population in

Crisp County over 21 years of age and hence eligible for service

on juries was 9,680; 3,567, approximately 37% were Negro; 6,113,

approximately 63% were white. Of the Negroes, 2,207 did not own

sufficient property to be placed on the Tax Digest. Thus, only

1,360 Negroes, or about 38.2% of the Negro population, could be

initially considered for jury service under the Georgia statutes

(R. H. 142). About 78% of the whites, or 4,758, were on the tax

digests (R„ H. 142) . It was stipulated at trial that a sub

stantial number of the citizens of Crisp County had all of the

statutory qualifications for jury service save being listed

on the Tax Digest, and for that reason were not considered for

jury service (R. H. 4C).

Of the persons on the Tax Digest themselves from which the

juries were selected, 22% were Negro; 13.7% of the traverse jury

actually drawn were Negro (7 out of 51). Of the grand jury, one

out of 21 was a Negro (R. H. 40).

The evidence as to the method used by the commissioners in

2/compiling the jury lists was as follows. In December, 1964

the jury commissioners cf Crisp County, at the instance of the

County Solicitor, revised the jury list (R, H. 42). The revised

lists, which took four to seven days to complete, were made from

names in the segregated Tax Digest (R. H. 78). Selection was

made by six white jury commissioners, aided at times by the ex

sheriff, tax commissioner and a Negro grocer, on the basis of

their knowledge of the people in the Digest (R. H. 60-61, 79-80).

Their knowledge of the Negro population was based entirely on

casual and business acquaintance (R. H. 43-45, 56-58, 80-82, 94,

101, 107, 121-22). Women, white or Negro, were considered for the

2/ There was evidence that there had been an earlier revision

In October, 1964 (R. H. 109), which had to be redone because all

the Negro names had been put at the end of the list (R. H. 109-10)

4

None3l/list only if they specifically requested it (R. H. 61).

of the commissioners could remember more than two Negroes actually

serving either on grand or traverse juries after use of the revised

list (R. H. 96, 108, 117, 132-33, 137).

Petitioners' pre-trial motions were all overruled by the trial

court. The two cases were tried separately and both petitioners

were convicted as charged (R. A. 25; R. H. 1 8 ) They were both

sentenced to 12 months in work camps (R. A. 26; R. H„ 19), and

the convictions were affirmed by the Supreme Court of Georgia.

Petitioners are presently enlarged on bail pending disposition

of this petition by this Court.

How the Federal Questions Were Raised

_______ and Decided Below_______ _

Prior to trial, petitioners made motions to quash the indict

ment and challenged the array of traverse jurors. They raised in

those motions the constitutionality under the Fourteenth Amendment

of excluding persons from consideration for jury service who did

not have sufficient property to be placed on the Tax Digest (R. A.

14-17; R. H. 14-17). They also raised the question of the consti

tutionality under the Fourteenth Amendment of the jury statutes

insofar as they required juries to be selected from tax digests

that were segregated as to race and the question of whether Negroes

had been systematically excluded from juries (R. A. 11-14; R. H.

10-14). Petitioners introduced evidence which showed the method

by which jury commissioners selected jurors. These motions were

overruled by the trial court.

3/ This practice was followed despite the absence of authorization

for it in the Georgia statutes.

4/ In the Hinton case, when the jury returned with its verdict

and was polled, it appeared that one of the jurors was either

incompetent or had bean under duress to agree to the verdict. The

jury was sent back out to reconsider its verdict, and counsel for

the petitioner moved for a mistrial or to be able to examine the

juror further. The jury returned once more with a verdict of

guilty. The motions were denied, however (R. H. 225-33).

5

Upon appeal these questions were raised by petitioners in

their enumerations of errors to the Supreme Court of Georgia

(R. A. 107-109; R. H. 237-39). The Supreme Court of Georgia

ruled on these points by holding that the challenge to the array

of the grand jury had been waived under Georgia law because it

was not made until after indictment. It further held that the

exclusion of persons with insufficient property to be on the Tax

Digest was constitutional and that the evidence as to exclusion

of Negroes was not sufficient to demonstrate such exclusion.

6

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

I

THE DECISION OF THE SUPREME COURT OF GEORGIA

CONFLICTS V7ITH THIS COURT'S DECISION IN

WIIITUS V. GEORGIA o

At the time of petitioners' convictions, May 1966, the jury

lists for crisp County and all other Georgia counties were required

5/by law to be made up from the county tax digests. Ga. Code Ann.

§ 59-106 (App. B, p. 1 ). The digests were required by law to

be segregated by race. Ga. Code Ann. § 92-6307 (App. B., p. 3).

Jury commissioners used the digest to select names of upright

and intelligent citizens" to serve as jurors, qualifying the

persons selected on the basis of the statutory standard and their

own knowledge of the people in the digest.

Thus, petitioners were indicted by a crisp County grand jury

and convicted by a traverse jury chosen under a selection system

virtually identical to the one already condemned by this Court as

a denial of equal protection of the laws. Whitus v. Georgiâ

6/385 U.S. 545; Bostick v. South Carolina, 386 U.S. 479.

The Supreme Court of Georgia refused to rule on petitioners

objections to the grand jury on the ground that the motion to

quash had been filed too late under Georgia law, i.e., after the

indictment had been handed down rather than before. Petitioners

urge, however, that the Georgia rule is not an adequate state

5/ The Georgia jury selection scheme was changed after this

Court's decision in Whitus v. Georgia, 385 U.S. 545. H.B. 307,

passed in the 1967 session of the Georgia Legislature, requires

that in the future jurors be selected from the lists of registered

voters and, if necessary, other sources. Petitioners here were

tried by a jury selected by the method in effect prior to Whituŝ.

6/ The jury list involved hex’e was selected in the revision in

T964. The system of selection had resulted in discrimination in

Crisp County prior to that revision. Thus, the Georgia Supreme

Court stated in another case that "the evidence is undisputed

that prior to the December 1964 term of the Superior Court o

Crisp County there has been a long history of 75 years in whic

only a few Negroes had served on a jury in Crisp County. This is

sufficient to establish a prima facie case of discrimination

against Negroes * * Brookins v. State, 221 Ga. 181, 144

S.E.2d 83, 87 (1965).

7

ground that bars this Court's reaching the question of the consti

tutionality of the composition of the grand jury. It clearly

would be impossible to raise the issue of the composition of

the grand jury before that jury had actually been drawn and its

Williams v. Georgia, 349 U.S. 375. In any event, since the grand

jurors were drawn from the same list as was the traverse jury

panel, the statistics as to the grand jury, set out below, are

relevant to deciding the issue of the constitutionality of the

method of selection of the traverse jury panel, a question reached

and decided by the court below.

In December 1964, the jury commissioners of Crisp County

had completely revised the jury list (R. H. 42).^/ Eut, just as

in Whitus, the revised lists were made, as statutorily required,

from the segregated tax digest. The method used was for the

rommissioners to meet, to call off one by one the names of tax

payers as listed on the digest, and to discuss whether each was

qualified according to the commissioners' knowledge. The six

jury commissioners were white and were aided at times by a few

outsiders, who provided additional information concerning the

Negro, were considered for the list unless they specr.fically

requested it (R. H. 61). Grand and traverse jury panels were

then selected from the jury list by the method prescribed by law.

Ga. Code Ann. § 59-106.

The following statistics were stipulated by counsel to apply

to this case. The tax digest numbered 1,360 Negroes and 4,758

whites, Negroes being 22% of the total taxpayers listed (R. H.

7/ The evidence as to the procedure followed by the commissioners T s found in the certified record in the Hinton case (R. II. 38-145) ,

and was used in both cases. The evidence consists of testimony

taken at the hearing on the motions in these cases, together with

evidence taken in Brookins v. State, 221 Ga. 181, 144 3.3.2d 83

(1965), which concerned the same jury list.

8/ The persons consulted were all whites, with the exception of

one Negro grocer (R. H. 79-80).

composition known. See, Reece v. Georgia, 350 U.S. 85? and cf_.,

people in the digest (R. H. 60-61, 79-80) & No women, white or

8

142). A venire of 30 men was drawn for grand jury duty; 2 Negroes

and 28 whites (R. H. 40). The percentage of Negroes drawn was

6.61%, which dropped to 4.7% when only one Negro was chosen to

serve on a panel of 21 (R. H. 40). At the same time a traverse

jury panel of 7 Negroes (13.7%) and 44 whites was drawn (86.3%)

(R. H. 40); the evidence does not show whether a Negro served on

the actual juries that tried the cases.

The testimony of the jury commissioners tended to corroborate

the discrimination revealed by the statistics. None of them

could remember more than a handful of Negroes who had been drawn

from the revised list, and only one or two who had actually served

on grand or traverse juries (R. H. 96, 108, 117, 132-33, 137).

The State did not attempt to rebut the petitioners' case.

Rather, the Supreme Court of Georgia attempted to distinguish

Whitus v. Georgia, suprac on the grounds that s (1) in that case

a discriminatory jury list and tax digest were used to make up

the revised list; (2) that in the instant case the jury commis

sioners called on outside help, including a Negro, to gain

information on the community taxpayers rather than relying solely

on their own knowledge? and (3) this case was governed by Swain

v. Alabama, 380 U.S. 202, since the percentage of Negroes on the

traverse jury panel as compared to that on the tax digest was

closer to the statistics developed in Swain than to those in

Whitus.

Petitioners contend that none of the grounds asserted by the

Supreme Court below are sufficient to distinguish the case from

Whitus.

(1) in Whitus, the discriminatory revised list was prepared

by using the jury list which had been condemned in Whitus v *

Balkcom, 333 F.2d 496 (5th Cir. 1964), as well as the segregated

tax digest. Preparation of the jury list from these two segregated

sources presented an "opportunity for discrimination. v *

Georgia, 385 U.S. at 552. The fact that here the jury list was

made only from the segregated tax digest, rather than from a

segregated jury list as well, in no way eliminated that opportunity

9

to discriminate." The most that can he said is that the Whitus

jury commissioners also had reference to a discriminatory jury

list which had been made from an earlier segregated tax digest.

In both cases the revised jury lists were made from segregated

sources.

(2) The use of outside sources in the way revealed by this

record in no way should lead to a different result. The people

consulted by the commissioners did not supply names in addition

to those on the segregated digests— they merely gave information

concerning persons listed in the digests. With a single excep

tion, they were white and knew little more of the Negro taxpayers

than the commissioners themselves. Lee Outlaw, the one Negro

consulted, operated a grocery store in the Southern part of

Cordele, Georgia, where only half of the Negro population lived

(R. H. 111-12). He allegedly went through the entire list of

1,360 Negro taxpayers in a half day or a whole day (R. H. 49).

He clearly was limited by his partial knowledge of the Negro

population and inadequate time to consider the qualifications

of the people that he did know.

(3) The Georgia Supreme Court misplaced its reliance on

Swain v. Alabama, 380 U.S. 202. The "opportunity for discrimi

nation, " in Whitus, resulting from preparation of a jury list

from segregated sources, was not present in S w a m . In Alabama,

a wide variety of sources were used for prospective jurors. 380

U.S. at 207.

For the above reasons, the decision of the Georgia Supreme

Court is in conflict with this Court's decision in Whitus v.

Georgia, certiorari is appropriate, and the judgment should be

reversed.

10

II

THE DECISION UPHOLDING THE EXCLUSION FROM JURIES

OF PERSONS SOLELY BECAUSE OF THEIR ECONOMIC

STATUS CONFLICTS WITH PRINCIPLES DECLARED BY

THIS COURT AND WITH DECISIONS OF THE FIFTH

CIRCUIT.

The Supreme Court of Georgia held that the exclusion from

jury service of persons with insufficient property to be on tax

digests did not violate the equal protection clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment. Petitioners contend that that decision

conflicts with principles set down by this Court in HarE§£ v*

Virginia State Board of Elections, 383 U.S. 663# which struck

down the exclusion of persons from state governmental processes

solely because of their indigency. The decision also is in con

flict with the decision of the Fifth Circuit in Labat v. Bennett,

365 F.2d 698 (5th Cir. 1966), which applied principles established

by this Court in Thiel v. Southern P. Co., 328 U.S. 217, and held

that the exclusion of daily wage earners from state juries violated

the equal protection clause.

Both the grand jury which indicted petitioners and the

traverse jury which convicted them were drawn from lists of

Crisp County landowners and personal property taxpayers in

accordance with Ga. Code Ann. § 59-106.^/ This Court has not yet

passed directly upon the important question presented by dis

crimination along economic lines in the selection of state juries.

At least three other states maintain explicit property qualifi

cations,^ and two other states expressly bar paupers from jury

9/ Petitioners' challenge to the composition of the grand jury

was overruled below on state procedural grounds, .i.e,., that it had

been made after indictment rather than before. Petitioners contend

that this rule is insufficient to prevent this Court :crom reaching

the issue (see text, supra). However, since the grand juiy is

selected from the list of jurors who in turn have bear* cnosen

exclusively from the county tax digests, the grand jury no less

than the traverse jury bears the taint of the improper selection

procedure.

10/ ind. Ann. Stat. § 4-3317 (Supp. 1966)r N.Y„ Judiciary Law

§ 504(3) (Supp. 1965); Tex. Rev. Civ. Stat. art. 2133 (1964).

11

service.^/ Even in jurisdictions where there are no express

statutory provisions, the juror selection process often functions

as if there were. For example, in 1949, the Clerk of the Vance

County, North Carolina, jury commission placed on the list those

among the eligible population who had "the most property," Speller

v. Allen, 344 U.S. 443, 480 (1953) (where the issue of economic

discrimination in state jury selection was expressly reserved for

future scrutiny). In Labat v . Bennett, 365 F.2d 698 (5th Cir.

1966) (en banc), daily wage earners were excluded from jury

service by the commissioners without statutory authority. In

other instances, persons who have failed to pay poll taxes have

been barred from jury service because the list of registered

voters was used as the source of names by the jury commission.

See, United States ex rel Goldsby v. Harpole, 263 F.2d 71, 78

(5th Cir. 1959).

For these reasons, the recent amendment of the Georgia

statute (substituting voter registration lists for tax digests

as tho source of prospective jurors) does not make the constitu

tional question raised by this record of less consequence. Cf,.

Spencer v. Texas, 385 U.S. 554, 556, Note 2 (1967).

The county tax digests in Georgia contain only the names of

property taxpayers. Ga. Code Ann. § 92-6305.“ *'' All real c*nd

personal property is subject to the state ad valorem tax and

the county tax unless otherwise exempted. Ga. Code Ann.

§ 92-101 Exemptions are granted covering land held for

charitable, religious, educational, or other eleemosynary purposes

11/ Del. Code Ann., Tit. 10 § 4504 (1953); W. Va. Code Ann.

§ 5262 (1961). And see, e.q., Ala. Code Ann., Tit. § 21 (Recomo. 1958) (illiterates excluded from jury service unless

they are freeholders or householders); Mont. Rev. Coues Ann.

§ 93-1402 (1964).

12/ Collection of the state income tax is made through the state

Revenue Commissioner's office rather than by county officials.

Ga. Code Ann. §§ 92-3101, 3210.

13/ See also, Ga. Code Ann. §§ 92-111 and 92-3706.

12

as well as property owned by certain foreign corporations. Ga.

Code Ann. §§ 92-130 and 92-201. In addition, a specific exemp

tion is granted for property actually occupied as a home up to

a valuation of $2,000, and for personal property such as clothing,

furniture, domestic animals, and tools up to a value of $300.

Ga. Code Ann. §§ 92-219 and 92-239.

An individual whose assets do not exceed the maximum allowed

by the various exemptions may be required to file a return indi

cating his non-liability for tax, but he will be excluded from

jury service. Thus, 62% of the Negroes in Crisp County did not

own sufficient property to be listed on the 1964 tax digest and

they were thereby barred from serving on grand or traverse juries.

Similarly, 22% of the white population of the County was excluded.

Petitioners contend that such a system of juror selection

violates the Fourteenth Amendment in at least three respects.

(1) It is a denial of equal protection of the laws because

the service on juries is restricted according to an irrational

and arbitrary distinction based on property ownership. It was

admitted by the State by stipulation that a "substantial number"

of Crisp County citizens have all of the statutory qualifications

for jury service; U e ., they are "upright," "experienced," and

"intelligent" (Ga. Code Ann. § 59-106). Nevertheless, they are

not considered for jury service because they have insufficient

property to be included on the tax digest (R. H. 40). Such

exclusion for the sole reason of indigency or insufficient pro

perty after statutory exemptions is no more valid under the

Fourteenth Amendment than was the denial of the right to vote on

analogous grounds struck down in Harper v . Virginia State Board

of Elections. 383 U.S„ 663. And, in other cases this Court has

similarly held that classifications based solely upon poverty

cannot be sustained. E_.g_., Griffin v. Illinois, 351 U.S. 12;

Gideon v. Wainwright, 372 T7.S. 335; Douglas v. California, 372

U.S. 353. While these cases concern the denial of counsel or

assistance on appeal, the principles which they embody extend to

every area of contact between the government and the citizen.

13

(2) Petitioners urge that Georgia's method of juror selec

tion contravenes the equal protection clause of the Fourteenth

Amendment because the consistent result of its use has been juries

on which the Negro minority in Crisp County is drastically under

represented. Despite repeated condemnation by this Court of the

exclusion or token inclusion of a racial minority on juries# such

practices continue under the guise of nonracial methods of

selection. Thus# in Labat v. Bennett, 365 F.2d 698 (5th Cir. 1966)#

the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit# sitting

en banc# held that the intentional failure to include daily wage

earners in the jury lists discriminated against Negroes in vio

lation of the equal protection clause in that the class excluded

contained a disproportionately large number of Negroes. 365 F.2d

at 720. As has been noted, the mere use of tax digests as the

source of prospective jurors automatically excludes 62% of the

adult Negro population of Crisp County. There can be no question

that the automatic disqualification of such a percentage amounts

to an invidious discrimination# whether that discrimination is

premised upon property classifications or not.

(3) Finally, petitioners urge that this Court recognize

and enforce the due process right to a jury which reflects a

cross section of the community available fcr service. Petitioners

clearly have standing to enforce this right since they themselves

are indigents and hence were tried by juries from which members

of their class were excluded (R. A. 27-29; R. H. 23-25). (See

also the affidavits of poverty filed with this petition.) A

holding that a cross section of the community must be represented

on state juries was intimated in Smith v. Texas# 311 U.S. 128

(1940)11/ and applied to federal juries in Thiel v. Southern,P.

Co.# 328 U.S. 217, 220. Many commentators read Thiel to presage

constitutional application of the standard to the states. See#

e.g..# 45 Mich. L. Rev. 262# 264 (1947); 26 Tex. L. Rev. 533, 536

14/ "it is part of the established tradition in the use of juries

as instruments of public justice that the jury be a body truly

representative of the community." 311 U.S. at 130.

14

(1948); 33 Va. L. Rev. 519, 521 (1947). See also, Fay v. New

York, 332 U.S. 261.

Indeed, in Labat v c Bennett, 365 F.2d 698 (5th Cir. 1966),

the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, sitting

en banc, has applied the cross-section theory of Thiel, to state

criminal juries, 365 F.2d at 722-23. There, the jury selection

system excluded daily wage earners. Thus, the decision of the

Supreme Court of Georgia in this case, by rejecting that argument,

is in conflict with the Fifth Circuit.

The court below relied on Brown v. Allen, 344 U.S. 443,

evidently interpreting that decision as permitting the selection

of jurors solely from tax digests that excluded a substantial

proportion of members of the community who were otherwise quali

fied for jury service. However, in Brown, the North Carolina jury

selection statute contemplated a list including not only property

owners but also voters. This Court specifically remarked that

the addition of voters as eligibles for jury service to an earlier

scheme limiting such service to taxpayers alone represented a

15/significant enlargement of the pool. 344 U.S. at 470. In

Brown, in fact, this Court clearly left open the question of the

validity of the use of a source for jurors by a state when that

source does not "reasonably [reflect] a cross-section or the

population suitable in character and intelligence for that civic

duty." 344 U.S. at 474. Here, the tax digests in Crisp County

do not reflect such a cross section since 62% of eligible Negroes

and 22% of eligible whites (comprising one-third of the total

eligibles) were automatically excluded from consideration for

jury duty, although many of them, as was stipulated, were otherwise

fully qualified.

15/ in addition, the new statute’'worked a radical change in the

racial proportions of drawings of jurors." Ibid. Moreover, the North Carolina taxing statutes involved in Brown provie.ed no P^o-

perty exemptions whatsoever and thus lacked the restrictive effec

of the Georgia statutes.

16/ One of the effects of the restrictive jury selection system

may be seen by the colloquy mentioned in footnote 4 , supra, where

it became apparent that one of the jurors serving was probably not

qualified. Without the property qualifications imposed by Georgia

law, the pool of qualified persons would of course be much greater#

thus reducing the chances of such a juror having to be used.

- 15 -

Thus, certiorari should be granted in order to determine

the important issue presented by this case, to decide the appli-

cability of Brown v. Allen to the facts here, and to resolve the

conflict with the Fifth Circuit’s decision in Lab at v. Bennett.,

supra.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, petitioners pray that a writ of

certiorari be granted*

Respectfully submitted,

JACK GREENBERG CHARLES STEPHEN RALSTON

MICHAEL MELTSNER

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York

C. B. KINGP.0. Box 1024

Albany, Georgia

Attorneys for Petitioners

JOHN P. HOWLAND

Of counsel

16

APPENDIX A

Decided: Feb. 23# 1967

SUPREME COURT OF GEORGIA # # 608, 609

23956 HINTON v. STATE

23957 ANDERSON v. STATE

1. Where a defendant is represented by counsel at a

commitment hearing and where no challenge to the array of

the grand jury is made until after indictment any conten

tion that the grand jury is not properly constituted will

be treated as having been waived.

2. The challenge to the array of the traverse jury was

properly overruled.

3. The Acts under which the defendants were indicted

Were not subject to the constitutional attack made

thereon.

4. When upon the trial of a case the poll of the jury

discloses a possibility that the verdict is not unanimous

the proper procedure is to return the jury to the jury

room for further deliberation.

(a) After verdict it is too late to challenge the com

petency of a juror where the alleged ground of incompetency

is known before verdict.

5. The evidence authorized the verdict.

2

The defendants were indicted, tried and con

victed under Code § 26—7202 and the Act of 1960 (Ga, L.

1960, p. 985; Code Ann. § 86-1210). After indictment a

motion to quash the indictment and challenge the array

of the traverse jury was filed in each case and after

hearing overruled. Demurrers were filed challenging the

Acts under which the indictments were made in one case

and after verdict the defendants' motions for new trial

were overruled. They now appeal and enumerate as error

these rulings adverse to them.

3

NICHOLS, Justice, 1. It was stipulated that

defendants were represented by counsel on April 5, 1966,

that commitment hearings were held on the fifth and sixth

of April, 1966 v/here the defendants were represented by

counsel and the indictments were returned on April 26, 1966.

No challenge to the array of the grand jury was made prior

to indictment although the defendants were represented

by counsel and had been represented by counsel for three

weeks prior to such indictments. Under the decision in

Blevins v. State, 220 Ga. 720 (3) (141 SE2d 426), and the

numerous cases cited therein the motions to quash the

indictments on this ground are without merit as such

contention must be treated as having been waived.

2. The challenge to the array of the traverse

jury was properly overruled. The contention of the

defendants is basically the same as that made in Whitus

v. State, 222 Ga. 103 (149 SE2d 130), reversed by the United

States Supreme Court (Whitus v. Georgia, U S ; 87

S. C. 643; L E2d ), and it is contended that such

decision is controlling in the cases sub judice. The

decision in that case, based upon entirely different

circumstances, nowise controls the present cases. While

in both cases the jury was selected from a segregated tax

4

digest as was required by Georgia statutes (this is no

longer required. See 1966 Ga. L. p. 393), there the

similarity ends. The evidence in the Whitus case showed

a "revision" of an old jury list which had previously

been declared to show discrimination while in the present

case the evidence showed a completely new jury list made

up from the tax digest without reference to the old jury

list. In Whitus the jury commissioners relied completely

upon their own knowledge of the people in the community

while in the present cases the jury commissioners sought

information from others including a negro business man in

the community.

These cases arose in Crisp County, as did the

case of Brookins v. State, 221 Ga. 181 (144 SE2d 83),

where the same question was presented for decision and the

jiiry selection approved. The evidence in the Brookins

case was stipulated as part of the evidence in the present

cases and the additional evidence adduced noway requires

a different result. The percentages of negroes on the

tax digest in Crisp County were shown to be 22 percent and

on the traverse jury actually drawn 13.7 percent (44 whito

anti 7 negro) . This is not such a disparity as to authorize

a conclusion on *-his ground alone th*': discrimination exists.

5

See Brookins v. State, supra, citing Swain v. Alabama,

380 U S 202 (85 S C 824; 13 L E2d 759). Nor is the require

ment that jurors be selected from a tax digest unconstitu

tional as contended by the defendants. See Brown v. Allen,

344 U S 443 (73 S C 397; 97 L E 469).

3. In case numbered 23957 hive defendant demurred

and sought to attack the constitutionality of the statues

[sic] under which he was indicted as being too vague and

uncertain to set forth a standard of conduct and therefore

they violate the due process clause of the Constitution

of the United States as secured by the Fourteenth Amendment

and the due process clause of the constitution of the

State of Georgia.

Code § 26-7202 provides; "Contemptuous use

or defacement. - It shall also be unlawful for any person,

firm or corporation to mutilate, deface, dsfrle or con

temptuously abuse the flag or national emblem of the United

States by any act whatever. (Acts of 1917, p. 203)." The

Act of 1960, supra, in so far as the case sub judice is

concerned makes unlawful the same conduct as it applies

to the flag or emblem of the State of Georgia.

In Halter v. Nebraska, 205 U S 34, 41 ( S C

51 L E 697), the United States Supreme Court upheld a

6

statute of the State of Nebraska which prohibited the use

of the national flag as a part of any advertisement. The

basis of such decision was the right of the people to

protect such flag from disrespectful conduct and insults.

The statute upon which Code Chapter 26-72 is based was

enacted after the decision in Halter v. Nebraska, supra,

and followed the language of the Nebraska statute. Accord

ingly, it must be assumed that the General Assembly was

cognizant of the above decision. It was there held; "One

who loves the Union will love the State in which he resides,

and love both of the common country and of the State will

diminish in proportion as respect for the flag is weakened.

Therefore a State will be wanting in care for the well

being of its people if it ignores the fact that they regard

the flag as a symbol of their country's power and pres

tige, and will be impatient if any open disrepect [sic]

is shown towards it." The conduct sought to be prohibited

by such statute is conduct which shows open disrespect for

such flag, and no question of freedom of speech is here

involved. The language of such statute making it unlawful

to mutilate, deface, defile or contemptuously abuse such

flags by any act is not vague, uncertain or indefinite, and

such statutes are accordingly not unconstitutional for any

7

reason urged in the demurrers attacking them. Nor was the

indictment, which expressly stated the unlawful conduct

of the defendants, subject to demurrer as being vague or

uncertain.

(a) In view of the holding in the preceding

division of the opinion it was not error, in the absence of

a proper request, to fail to define in the charge to the

jury the terms contained in such statutes which needed no

definition in order to be understood by the jury.

4. The next enumeration of error to be dealt

with concerns a motion for mistrial which was overruled in

case numbered 23956. After deliberation the jury returned

to the courtroom and its verdict was published. Counsel

for the defendant then began to poll the jury and as the

second juror was being polled a colloquy took place which

counsel for the defendant interpreted as showing that the

verdict returned was not the verdict of such juror. At

this point, on motion of the Solicitor-General, the jury

was instructed to return to the jury room and return a

unanimous verdict if possible and if not possible to so

inform the court. After further deliberation the jury

returned to the courtroom and published another verdict

which apparently (as far as can be observed from the tran-

8

script), consisted of the original written verdict with the

additional words "by unanimous vote" added after "guilty."

Counsel for the defendant objected to such verdict as not

being a new verdict but the same verdict to which a question

arose and requested that the jury be instructed to return

to the jury room and write out a new verdict which request

was granted. Again the jury returned to the jury room and

at this point counsel for the defendant moved for a mistrial

based upon the colloquy which took place when the jury was

being polled after the original verdict was published.

This motion was overruled and thereafter the jury returned

to the courtroom with a rewritten verdict of guilty and

upon being polled each member of the jury affirmed that it

was his verdict.

The procedure followed by the trial court in

directing the jury to return to the jury room and arrive

at an unanimous verdict if possible was not error as this

is the proper procedure where a poll of the jury discloses

other than a unanimous verdict of the jury. Macon Ry. &

Light Co. v. Barnes, 121 Ga. 443, 448 (49 SE 282).

(a) Nor was it, after the verdict was published

and the jury returned to the jury room to correct it as to

form, error to overrule a motion for mistrial or hear evi

dence because of the alleged incompetency of one of the jurors

9

5. All who participate in the commission of a

misdemeanor are principals. Parmer v. State, 91 Ga. 152

(16 SE 937): Crocker v. State, 103 Ga. App. 870 (121 SE2d

166) .

"Intention may be manifested by the circumstances

connected with the perpetration of the offense, and the

sound mind and discretion of the person accused." Code

§ 26-202.

The evidence disclosed that the defendants were

involved in a "freedom march" in Crisp County, Georgia

and a crowd (estimated by various witnesses to be as many

as 250 persons) had gathered at the County Courthouse.

The defendants moved over to the flagpole and proccded [sic]

to lower the flags. The defendant Hinton in his unsworn

statement said the negro community was in a state of mourning

and he intended to lower the flag to half mast to symbolize

the state of mourning. The defendant Anderson made no

statement. At this point, as the flag was being lowered

others in the group closed in, removed the flags from the

lanyard actually tearing the American flag and damaging

the State flag, both of which were displayed to the jury,

and proceded [sic] to shake the flags in the faces of the

police officers ■'•’ho were stationed nearby, At this point

10

James Burch toofc possession of the flags from the demon

strators and delivered them to the county authorities.

The evidence authorized the verdicts.

Judgments affirmed. All the justices concur.

APPENDIX B

Georgia Statutes Relating to

Jury Selection and Tax Digests

Ga. Code Ann, §59-106 (1963 Supp.) . Revision of jury;

lists. Selection of grand and traverse jurors.. — Biennially,

or, if the judge of the superior court shall direct, tri-

ennially on the first Monday in August, or within 60 days

thereafter, the board of jury commissioners shall revise

the jury lists.

The jury commissioners shall select from the books

of the tax receiver upright and intelligent citizens to

serve as jurors, and shall write the names of the pex’sons so selected on tickets. They shall select from these a

sufficient number, not exceeding two-fifths of the whole

nuiriber, of the most experienced, intelligent, and upright

citizens to serve as grand jurors, whose names they shall

write upon ether tickets. The entire number first selected,

including those afterwards selected as grand jurors, shall

constitute the body of traverse jurors for the county, to

be drawn for service as provided by law, except that when

in drawing juries a name which has already been drawn for

the same term as a grand juror shall be drawn as a traverse

juror, such name shall be returned to the box and another

drawn in its stead. (Acts 1878-79, pp. 27, 34; 1887, p. 31;

1892, p. 61; 1899, p. 44; 1953, Nov. Sess., pp. 234, 285;

1955, p. 247.)

Ga. Code Ann. §92-101 (1961 Revision). Taxable property.— All real and personal property, whether owned

by individuals or corporations, resident or nonresident,

shall be liable to taxation, except as otherwise provided

by law. (Acts 1851-52, pp. 288, 289.)

Ga. Code Ann. §92-130 (1961 Revision). Exemptions— There

shall be exempt from taxation all intangible personal

property owned by or irrevocably held in trust for the

exclusive benefit of, religious, educational and charitable

institutions, no part of the net profit from the operation

of which can inure to the benefit of any private person.

There shall be exempt from all ad valorem intangible

taxes in this State, the common voting stock of a sub

sidiary corporation not doing business in this State, if

at least 90 per cent of such common voting stock is owned by a Georgia corporation with its principal place of

business located in this State and was acquired or is held

for the purpose of enabling the parent company to carry

on some part of its established line of business through

such subsidiary. (Acts 1946, pp. 12, 14; 1947, p. 1183.)

Ga. Code Ann. §92-201 (1961 Revision). Property

exempt from taxation.— The following described property

shall be exempt from taxation, to-wit: All public prop

erty; places of religious worship or burial, and all

property owned by religious groups used only for single

family residences and from which no income is derived;

all institutions of purely public charity; hospitals not

operated for the purpose of private or corporate profit

and income; all intangible personal property owned by or

irrevocably held in trust for the exclusive benefit of

4 <

- 2 -

religious, educational and charitable institutions, no

part of the net profit from the operation of which can

inure to the benefit of any private person; all buildings

erected for and used as a college, nonprofit hospital,

incorporated academy or other seminary of learning, and

also all funds or property held or ‘*sed as endowment by such colleges; nonprofit hospitals, incorporated academies

or seminaries of learning, providing the same is not invested

in real estate: and Provided, further, that said exemptions

shall only apply to such colleges, nonprofit hospitals,

incorporated academies or other seminaries of learning as

are open to the general public: Provided, further, that

all endowments to institutions established for white

people shall be limited to white people, and all endowments

to institutions established for colored people shall be

limited to colored people; the real and personal estate of

any public library, and that of any other literary asso

ciation, used by or connected with such library; all books and philosophical apparatus and all paintings and statuary

of any company or association, kept in a public hall and

not held as merchandise or for purposes of sale or gam:

Provided the property so exempted be not used for the

purpose of private or corporate profit and income, distributable to shareholders in corporations owning such property

or to other owners of such property, and any income from such property is used exclusively for religious, educational

and charitable purposes, or for either one or more of

such purposes and for the purpose of maintaining and

operating such institutions; this exemption shall not

apply to real estate or buildings other than those used

for the operation of such institution and which is ren^ ed,

leased or otherwise used for the primary purpose of securing

an income thereon; and also Provided that such donations of

property shall not be predicated upon an agreement, contract

or otherwise that the donor or donors shall receive or retain any part of the net or gross income of the property;

farm products, including baled cotton grown m thm State and remaining in the hands of the producer * but not longer

than for the’year next after their production. The word

"production" as applied to laying hens shall mean from

the time that such laying hens come into production at age

six months rather than when said laying hens are hatched.

The words, "institutions of purely public charity," "nonprofit hospitals," and "hospitals not operated fcr̂ the pur

pose of private or corporate profit and income," snail mean

and include such institutions or hospitals which may have

incidental income from pay patients: Provided such income,

if any, is devoted exclusively to the charitable purpose of

caring for patients who are unable to pay, and for the pur

pose of maintaining, operating and improving the facilities

of such institutions and hospitals, and not directly or

indirectly for distribution to shareholders in corporations

owning such property, or to other owners of same. (Acts

1878-9, p. 33; 1913, p. 122; 1919, p. 32; 1943, p. 348;

1946, p. 12; 1947, p. 1183; 1955, pp. 262, 263; 1965, pp.

182, 183.)

Ga. Code Ann. §92-219 (1961 Revision). Exemption of

home occupied by owner.— The homestead of each resident of

Georgia actually occupied by the owner as a residence and

homestead, and only so long as actually occupied by the

owner primarily as such, but not to exceed $2,000 of its

value, is hereby exempted from all ad valorem taxation for

State, county and school purposes, except taxes levied by

municipalities for school purposes and except to pay interest

on and retire bonded indebtedness: Provided, however,

should the owner of a dwelling house on a farm, who is

already entitled to homestead exemption, participate in

the program of rural housing and obtain a new house under

contract with the local housing authority, he shall be

entitled to receive the same homestead exemption as allowed

before making such contract. The General Assembly may from

time to time lower said exemption to not less than $1,250.

The value of all property in excess of the foregoing exemp

tions shall remain subject to taxation. Said exemptions

shall be returned and claimed in such manner as prescribed

by the General A-ssembly. The exemption herein provided

for shall not apply to taxes levied by municipalities.

(Acts 1946, pp. 12, 14.)

Ga. Code Ann. §92-239 (1961 Revision). Exemption of

personalty.— All personal clothing, household and kitchen

furniture, personal property used and included within the

home, domestic animals and tools, and implements of trade

of manual laborers, but not including motor vehicles, are

exempted from all State, county, municipal and school

district ad valorem taxes, in an amount not to exceed $300

in actual value. (Acts 1946, pp. 12, 13.)

Ga. Code Ann. §92-6307 (1961 Revision). Entry on

digest of names of colored persons.— The tax receivers

shall place the names of the colored taxpayers, in each

militia district of the county, upon the tax digest in alphabetical order. Names of colored and white taxpayers

shall be made out separately on the tax digest. (Acts

1894, p. 31.)