Evans v. Newton Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

September 1, 1965

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Evans v. Newton Brief Amicus Curiae, 1965. ae2ddc29-b19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/bf6e4eb0-be3b-4e3c-a46a-605ed9bbf532/evans-v-newton-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

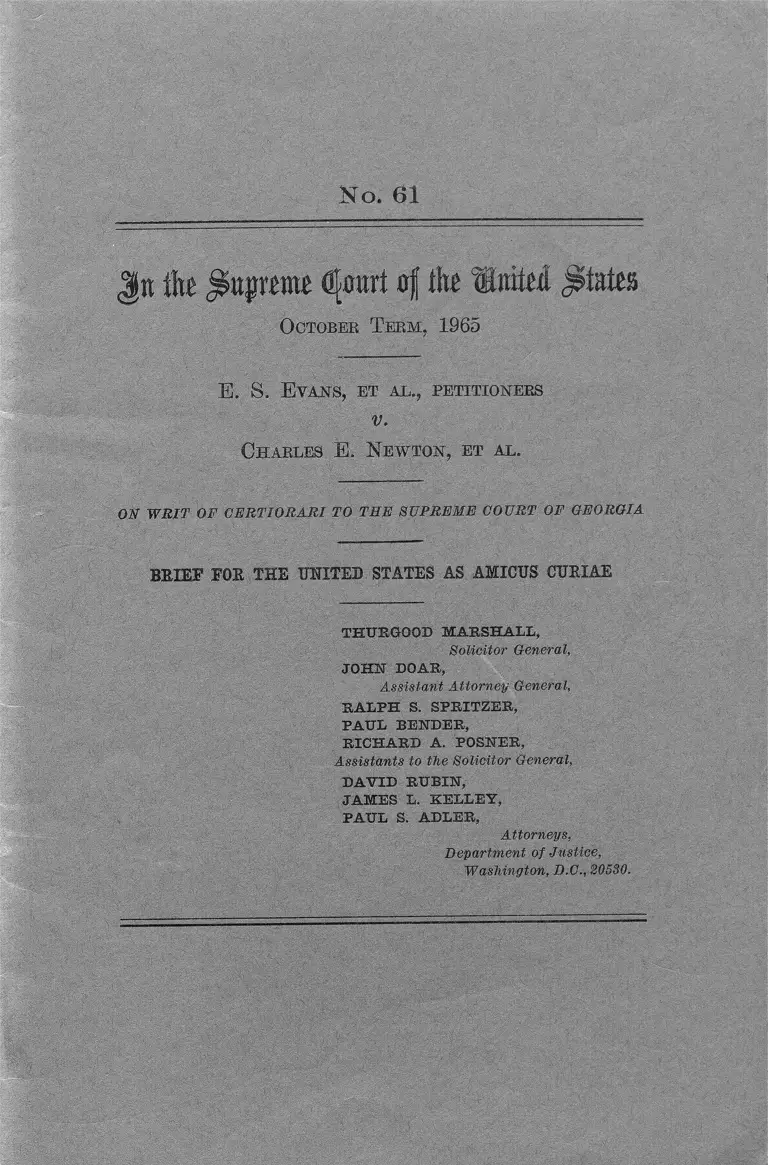

No. 61

Jin the Supreme tyomt of the ilratti states

October T erm, 1965

E. S. E yAJSTS, ET Ah . , PETITIONERS

V .

Charles E. Newton, et al.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE SUPREME COURT OF GEORGIA

BEIEF EOE THE UNITED STATES AS AMICUS CUEIAE

TK U RG O G D

Solicitor General,

JO H N D O A R ,

Assistant Attorney General,

R A L P H S. S P R IT Z E R ,

P A U L B E N D E R ,

R IC H A R D A . PO SN ER,

Assistants to the Solicitor General,

D A V ID R U B IN ,

JA M E S L. K E L L E Y ,

P A U L S. A D L E R ,

Attorneys,

Department of Justice,

Washington, D.C., 20530.

I N D E X

Page

Opinion below__ ____ 1

Jurisdiction____________________________________ i

Question presented____________ ....__________ ____________ ; \ 2

Interest of the United States___________________________________2

Statement____________________________________________■___ 3

Argument:

Introduction and summary________■_________________ 7

Viewed in their totality, the factors which establish

that Baconsfield serves a public function and that

the State is significantly involved in the history and

conduct of its operations require the conclusion that

the Fourteenth Amendment applies_______________ 10

1. State paternity and superintendence_________ 12

2. State support and maintenance_ ____________ 15

3. The public character of the park_____________ 16

4. Irhpact upon racial minorities________________ 20

5. State involvement in the decision to discrimi

nate___________________________ 23

6. The effect upon private choice__ ____________ . 26

Conclusion__________________________ ____ ____________ . 29

CITATIONS

Cases:

B alivnny. Morgan, 287 F. 2d 750_,____i________12*16, 17

Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U.S. 249_________________ 17, 29

Bell v. Maryland, 378 U.S. 226___________ ______ 10, 17, 21

Boman v. Birmingham Transit Co., 280 F. 2d 531 _ _ _ _ 12, 17

Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen v. Howard, 343 U.S.

768________i.________________________________ _____ 12

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U.S. 60___________________ 21

Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U.S.

715_______________ ________________ _ 9, 10, 14, 20, 24, 26

Civil Rights Cases, 109 U.S, 3----------- -----------10, 11, 26

; Coke v, City of Atlanta, 184 F. Supp. 579:____________ 20

d>787-479—88— 1

Gases—Continued prm

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 4 _ - - - - - ~ - - — ̂ . 15

Cox y. DeJarnette, 104 Ga. App. 604----- -------------------- 14

Gumming v. Trustees of Reid Memorial Church, 64 Ga,

105____________________________________________________25

Department of Conservation <fe ;Development v, Tate,

: 231 F. 2d 615----- - - - - - - - - — 20

Derrington v. Plummer■, 240 F. 2d 922, certiorari denied,

353 U.S. 924_____________ .--------- - -------- 20

Doming, y , Stanley , 162 Ga, 211— . W- — 25

Duffee y. Jones, 208 Ga. 639— ----------- 25

Eaton v. Grubbs, 329 F. 2d 710. _— 11* 43, 15

Freeman v. Retail Clerks Local 1207, 28 U.S. Law Wk.

2311 (Kings County Super. Ct., Washington,

decided December 9, 1959),- _ --------------------- - 1~

Girard College Trusteeship, 391 Pa. 434------- H

Gomillion v. Lightfogt, 364 U.S, 339------ , ----- ------------- 26

Greenway v. Irvin’s Trustee, 279 Ky. 632-------------- — 25

Griffin v. Maryland, 378 U.S. 130........ ....... .............. - - 7

Griffin v. School Board, 377 U.S. 218------------------------- 26, 29

Guillory v. Administrators of Tulane University, 203 F.

Supp. 855----------------------- - - - - - — 7, 15, 17

Guillory v. Administrators of Tulane University,

212 F. Supp. 674_______________ ______ ___________ 29

Harris v. Brown, 124 Ga. 3 1 0 , ------- 25

Jones y. Marva Theatres, Inc., 180 F. Supp. 49---------- 20

Kerr v. Enoch Pratt Free Library, 149 1 .2d 212— - - - 15

Lawrence v. Hancock, 76 F. Supp. 1004__--------— — •• 20

Leeds v. Harrison, 15 N.J. Super. 8 2 . ------------------ — 25

Lombard v. Louisiana, 373 U.S. 267— ------------— 10, 23, 24

Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U.S. 501„-------------------- 10, W, 19

Morehouse College v. Russell, 219 Ga. 717. ------------— 14

M uir y. Louisville Park Theatrical Ass’n. 347 U.S. 971,

reversing 202 F. 2d 275------- , 4 20

Nash y. A ir Terminal Services, 85 F. Supp. 5 4 5 - . 2 0

National Labor Relations Board v. Lake Superior

Lumber Carp,, 167 F. 2d 147----------17

National Labor Relations Board v. Stowe Spinning

Co., 336 U.S. 226------------------ - --------------------------- --- ̂ 17

Nixon y. Condon, 286 U.S. 73------------------------------- — 17,48

Pace y. Dukes, 205 Ga. 8 3 5 - - - - - - - -— ------- - - - - - ^

IX.

Gases—Continued '‘Page

Pennsylvania v. Board of Trusts, S53 tJ.S,-230L- > 7

10, 11, 12, 20, 24

Pennsylvania v. Board o f Trusts, 357 U.’S. 570 j _ „ : "v 11

Peterson v. Greenville, 373 U.S. 2 4 4 . ____________C_.' 10, 23

Public Utilities Com,m’n v. Pollack, 343 U.S. 4-51.. 10, 12, 17

Railway Employes’ Dept. v. Hanson, 351 U.S. 2 2 5 . . . . 10, 12

Regents of University System y. Trust OS', of Georgia,

186 Ga. 498___________________________ i , _____ 14

Republic Amotion Corp. y. National Labor Relations

Board, 324 U.S. 7 9 3 .._____C j . - . . . C 17

Rice y. Elmore, 165 F. 2d 387 ..1 .. J--.-U._t ■. A 17

Robinson V. Florida, 378 U.S. 153: C . _ J_ . . __ _ _ _j _ , i 23

Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1. . . . . . . . . 10, 17, 21,22, 25. 26

Silcox y. Harper, 32 Ga. 639___ . . - . . . . I . . . . 25

Simians v. Moses H. Cone Memorial Hospital, 323 F,

2d 929, certiorari denied, 376 U.S. 958_±:. . . 13 15

Smith v. Attwrigkt, 321 U.S. 1 4 9 . ..10' 17

Smith v. Holiday Inns of America, Inc. , 220 F. Supp. l l > 20

Steele v. Louisville & N. R. Co., 323 U.S. 1 9 2 . . . . . . . . . R) 12

Stubbs y. City of Macon, 78 Ga. App. 237..................... ■■■•:,’ ig

Terry y. Adams, 345 U.S. 461___________ _ _ _ 10, 17

Constitution and statutes:

U.S. Constitution: " v::

Fourteenth Amendment. _______ - 1j ____ 2

4, 5, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 13, 15, 23, 26, 27, 28

Fifteenth Amendment._____. 1 . 1 7

Civil Rights Act of 1964, 78 Stat. 241, et sef.

§ 201(b)(l)-(4 )___________ __________

Pa. Stat. Ann., Tit. 18, § 4654.___

Georgia Code Ann.:

§ 69-504_______...____________ ____ _ __

§ 6 9 -5 0 5 -.- .. . . . . . _____________ ____

§ 69-602__________________

§ 92-201______ C

§ 108-201.._______ ____________ .

§ 108-202____________ ________________

§ 108-206-09... ______ _______ ________

§ 108-212 (1963 Supp.)____________

Miscellaneous:

:-----i 12

------ 1 12

13, 14,23, 24

23

- C 18

------•- 15

13

- — 6

------- • 14

------- 13

10 McQuillin, Municipal Corporations (3d e d )

§ 28.51__________________________________ . . . 18

j n tte ^ujjwntc afoiirt of the Suited pistes

October T erm, 1965

No. 61

B. S. E vans, et al., petitioners

v.

Charles E. Newton, et al.

OS WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO TEE SUPREME COURT OF GEORGIA

BRIEF for the united states as amicus curiae

O P IN IO N BELO W

The order and decree of the Superior Court of

Bibb County (R. 64-66) are not reported. The

opinion of the Supreme Court of Georgia (R. 81-88)

is reported at 220 Ga. 280, 138 S.E. 2d 573.

JU R ISD IC T IO N

The judgment of the Supreme Court of Georgia

was entered on September 28, 1964 (R. 89). Re

hearing was denied on October 8, 1964 (R. 92). By

order of December 22, 1964, Mr. Justice Stewart ex

tended the time for filing a petition for a writ of cer

tiorari to and including March 5, 1965 (R. 93). The

petition was filed on that date, and granted on April 26,

1965 (R. 94; 380 U.S. 971). The jurisdiction of this

Court rests on 28 U.S.C. 1257 (3).

(i)

2

QUESTION PRESENTED

Baconsfield is a , large park and recreation area

established for the use oi' all white persons of the

City of Macon, Georgia, under a charitable trust

which originally (in 1911) designated the City as

trustee. In 1963, the City managers of Baconsfield

brought the present suit in a State court to have

private trustees designated in place, o f the City.

The purpose was to permit Baconsfield to continue

operation as a facility for whites only. In the course

of the action, the City resigned as trustee and the

court appointed private trustees.

The question presented is whether Baconsfield,

viewed in the light of its history and taking into

account its public role in the community, the public

incidents and effects of its operation and the exten

sive character of the,State’s involvement in its estab

lishment and administration, is to be regarded as a

public institution subject to the requirement of the

Fourteenth Amendment that its use not be denied

to Negroes on the basis of their race.

IN T E R E S T OP T H E U N IT E D ST A TE S

The denial of equal opportunities to this country’s

Negro citizens is a matter of utmost national concern.

The present case—involving the question whether

racial discrimination in the administration of a char

itable trust established to fulfill an important public

purpose is beyond the reach of the Equal Protection

Clause—has far-reaching implications. We deem

it appropriate, therefore, to submit the views of the

United States.

S T A T E M E N T

In 1911, United States Senator Augustus O. Bacon

executed a will granting a life estate, in trust, in

certain designated real property known as “ Bacons-

field” for the benefit of his wife and two named

daughters (R. 12, 18-19). Senator Bacon’s will

further provided that upon the death of the last sur

viving beneficiary, the Baconsfield property, including

alh remainders and reversions,

shall thereupon vest in and belong to the Mayor

and Council of the City o f Macon, and to their

successors forever, in trust for the sole, per

petual and unending, use, benefit and enjoy

ment of the white women, white girls, white

boys and white children of the City of Macon

to be by them forever used and enjoyed as a

park and jdeasure ground, subject to the re

strictions, government, management, rules and

control

of a Board of Managers of seven persons, at least

four to be women and all seven to be white (R. 19).

The Board, to be appointed by the Mayor and City

Council, was given discretion to open the park to

white men and white non-residents of Macon (R. 19-

20), and this power has been exercised (R. 7-8). To

provide for maintenance of the park, income from

other described real property was to be expended by

the Board of Managers (R. 20). Senator Bacon stated

in his will that he was providing for a park exclu

sively for whites because he disapproved of the social

mixing of the white and ISTegro races (R. 21).

3

4

This suit was brought on May 4, 1963, in the Supe

rior Court of Bibb County, Georgia, by the individual

members of the Board of Managers of Baconsfield, in

their capacities as members of the Board, against the

City o f Macon and the trustees of certain residuary

beneficiaries of Senator Bacon’s estate (R. 5-10),

Its purpose was to enforce the racial limitations in

the will. It was alleged that the City was “ failing

and refusing to carry out and enforce the provisions

of said Will with respect to the exclusive use” of the

parfi by white persons (R, 8). The plaintiffs asked

that the City be removed as trustee, that the court ap

point new trustees and that the legal title to “ Bacons-

field” and any other assets held by the City of Macon

as trustee under Senator Bacon’s will be vested in the

trustees so appointed (R. 9).

The City’s answer alleged that it could not legally

enforce racial segregation in the park and asked that

the court construe the will and enter a decree setting

forth its duties and obligations as trustee (R. 32-34).

The other defendants admitted the allegations and re

quested the removal of the City as trustee (R. 34—35).

On May 29, 1963, six Negro citizens of the City of

Macon moved for leave to file a petition for interven

tion on behalf of themselves and other Negroes sim

ilarly situated (R. 36). In their petition, filed on

June 18, 1963, they asserted that the racial limitation

was contrary to the public policy of the United States

and the laws of Georgia and that the Superior Court,

as an agency of the State of Georgia, could not, con

sistently with the Equal Protection Clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment, enter an order appointing

private citizens as trustees for the purpose of regulat

ing public property in a racially discriminatory man

ner (R. 40). They asked the court to effectuate the

general charitable purpose of the testator to establish

and endow a public park by refusing to appoint

private trustees (R. 41-42) .1

On February 5, 1964, the City filed an amendment

to its answer alleging that, pursuant to a resolution

adopted by the Mayor and City Council on February

4, 1964, the City had resigned as trustee. The City

asked that its resignation be accepted and substitute

trustees be appointed (R. 50-51). The Negro inter-

venors subsequently amended their petition, alleging

that the Fourteenth Amendment would be violated if

the relief sought by the parties was granted (R.

62-63).

1 On January 8, 1964, the plaintiff members of the Board of

Managers filed an amendment to their original petition, re

questing (1) that Negroes be enjoined from using the park, (2)

that four previously unrepresented residuary legatees under

Senator Bacon’s will (the Sparks heirs) be added as plaintiffs,

and (3) that the trustees o f the Curry heirs, originally joined

as defendants, be permitted to assert the interests o f the Curry

heirs as plaintiffs (E. 42-45). At the same time, the Sparks

heirs intervened, the trustees for the Curry heirs sought leave

to assert their interests as plaintiffs, and both parties joined in

the original plaintiffs’ prayers for relief (E. 45-49). Addi

tionally, the Sparks heirs and the trustees for the Curry heirs

asked for reversion of the trust property to the Bacon estate

in the event that other relief was denied (E. 47, 49). In the

decree of the Superior Court, no ruling was made on the

requests that Negroes be enjoined from using the park and

the conditional prayers for reversion of the trust property

were held to be moot (E. 65).

787—479—65----2

6

The Superior Court of Bib!) County issued a decree

on March 10, 1964, which, inter alia, (1) allowed in

tervention by the Negro interveners, (2) accepted

the resignation of the City of Macon as trustee of

the park, and (3) appointed three individuals as new

trustees (R. 64-66). The relief souglit, by the Negro

interveners was denied. Subsequently, all seven of the

City-appointed members of the Board of Managers of

“ Baeonsfield” submitted their resignations to the three

new court-appointed trustees. The latter then reap

pointed three of the old Board members and appointed

four new members (R. 70-72).

On appeal by t he Negro intervenors, the Supreme

Court of Georgia affirmed. It held that “ A. O.

Bacon had the absolute right to give and bequeath

property to a [racially] limited class” (R. 87); that

charitable trusts are subject to the supervision of the

courts (Ga. Code Ann. § 108-202) ; and that, since the

City had resigned as trustee, the Superior Court was

authorized to appoint private trustees in its place

(R. 86) .2

The record does not disclose the physical charac

teristics of Baeonsfield. We have therefore attached

at the end of our brief a recent map of the City of

Macon. It is apparent from the map that Baeonsfield

2 The Supreme Court held further that, assuming the inter

venors' could properly raise the issue of cy-pres, the Superior

Court had not erred in refusing to apply the doctrine to this

case. The court said that “the facts * * * w6re wholly in

sufficient to invoke a ruling that the charitable bequest was or

was not incapable for some reason o f exact execution in the

exact manner provided by the testator” (R. 87).

7'

is one of Macon’s largest parks, artel its size can be

estimated as about 100 acres. It is centrally located, on

the banks of the Oemulgee River, and is traversed by a

major interstate highway (Route 16) as well as by

several streets which connect with the public streets

abutting the park.

A R G U M E N T

Introduction and Summary

For many years the City of Macon and its Board

of Managers served as trustee and administrator of

Baconsfield. During that period, Baeonsfield was, in

every practical sense, a City park, and, until recently,

the City entirely excluded Negroes from the park un

der the terms of the trust, while freely admitting all

white persons who desired to use the park. In thus

operating Baconsfield as a park solely for the use of

white persons, the City clearly was violating the Four

teenth Amendment. It made no difference that the

park was not owned outright by the City, but was

merely administered by it under a trust containing a

racial exclusion. See Pennsylvania v. .Board of

Trusts, 353 U.S. 230 (the Girard Trust case) ; cf. Guil

lory v. Administrators of Tulane University, 203 F.

Supp. 855 (K B . La). The Fourteenth Amendment

forbids a State to undertake “ an obligation to en

force a private policy of racial discrimination” ( Grif-

jin v. Maryland, 378 U.S. 130, 136).

Shortly before this suit was instituted, the City of

Macon began to permit Negroes to. use Baconsfield.

The explicit purpose of the present suit was. to reverse

that course of action and restore Baconsfield as a segre

8

gated facility. The suit was brought in a State

court by the members of the Baconsfield Board of

Managers against the City and certain heirs of Sena

tor Bacon. The plaintiffs alleged, as a basis for

relief, that the City was ‘ Tailing and refusing to

carry out and enforce the provisions of said Will

[of Senator Bacon] with respect to the exclusive

use” of Baconsfield park by white persons (R. 8).

The court; was asked to appoint new trustees who would

be obligated to exclude Negroes from the park. Six

Negro citizens of Macon, who were permitted to inter

vene in the litigation, urged that the requested relief

be denied under principles of State and federal law.

While the suit was pending, the Mayor and Coun

cil of Macon resigned as trustees of Baconsfield.

Thereafter, the court entered an order accepting their

resignation and appointing three new trustees to oper

ate Baconsfield on a segregated basis. The new

trustees appointed a new Board of Managers which

included three members of the old board appointed by

the city. On appeal to the Supreme Court of Georgia

by the Negro intervenors, the lower court’s order was

affirmed.

The basic question thus raised in this Court is

whether it is consistent with the Fourteenth Amend

ment for Baconsfield to be operated by the newly ap

pointed trustees as a facility exclusively for white per

sons. In rejecting the intervenors’ contentions below,

both Georgia courts have expressly held that Baeons-

field may be so operated.

The Fourteenth Amendment, in providing that

“ [n]o State shall * * * deny to any person within

9

its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws” ,

reaches every form of State-sponsored inequality.

The question presented, therefore, cannot be resolved

in favor of permitting Baconsfield to remain exclu

sively a white facility merely by noting that formal

legal title to the park has now been transferred by

the Georgia courts to trustees who are not members

of the City government. As this Court has recog

nized on a number of occasions, formally ' ‘ private”

conduct may sufficiently assume the character of gov

ernmental action or may become so entwined with

or dependent upon governmental actions or policies

as to become subject to the constitutional limitations

placed upon State action.3 It is our position in this

case that Baconsfield has thus become a public facility

subject to the Fourteenth Amendment, despite the

formal transfer of title and control to private trus

tees; the Georgia courts therefore erred in deciding

that Baconsfield may be operated for the benefit of all

the white citizens of Macon while Negroes are excluded.

We base our judgment upon the totality of relevant

facts and circumstances bearing on the degree of

State involvement, mindful of this Court’s warning

against attempting to formulate fixed rules or me

chanical tests to measure State action in areas of

mixed public action and private responsibility (Bur

ton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U.S. 715,

722). Proceeding under this approach, we show that

the facts and circumstances of this case demonstrate

3 See cases cited at nn. 4 to 6, infra, pp. 10-11.

10

“ State action of a parteiular character that is pro

hibited” ( Civil Rights Cases, 109. IT.S, 3, 11).

VIEWED I X THEIR TOTALITY, THE FACTORS WHICH ESTAB

LISH THAT BACONSFIELD SERVES A PUBLIC FUNCTION

AND THAT THE STATE IS SIGNIFICANTLY INVOLVED IN

THE HISTORY AND CONDUCT OF ITS OPERATIONS REQUIRE

THE CONCLUSION THAT THE FOURTEENTH AMENDMENT

APPLIES

In attempting to determine the point at which State

involvement in an activity conducted by private per

sons gives the activity sufficient governmental char

acter to bring a discriminatory practice within the ban

of the Fourteenth Amendment, we look to six major

factors which this Court has deemed relevant to such

an inquiry: (1) the degree of State paternity and

superintendence afforded the discriminating enter

prise ; 4 (2) the extent of direct State support and

maintenance of the activity;5 (3) the public character

of the discriminating enterprise;6 (4) the impact of

the discrimination upon the affected minorities;7 (5)

the extent of State participation in, or encouragement

of, the decision to discriminate;8 and (6) the absence

of a significant interest in private determination in

4 See, Railway Employes’ Dept. v. Hanson, 351 U.S. 225;

Steele v. Louisville <& N. R. Go., 323 U.S. 192; Public Utilities

C'omm'n v. Poliak, 343 U.S. 451.

r> See Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, supra; Penn

sylvania v. Board o f Trusts, supra.

16 See Smith v. AUwright, 321 I7.S. 149; Terry v. Adams, 345

U.S. 461; Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U.S. 501.

7 See Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S. 1; Bell v. Maryland, 378

U.S. 226, 329 (dissenting;opinion). '

* See Peterson v. Greenville., 373 U.S. 244; Lombard v. Louisi

ana, 373 U.S. 267.

11

the management of the enterprise.9 We suggest below

that all of these elements are involved to a substantial

degree in Baeonsfield. There is thus no need to decide

in this case whether any single one of them would, if

present in sufficient strength, require a finding that

the State is responsible for racial discrimination ir

respective of the remaining considerations. The

totality of circumstances showing the State’s close

participation in the establishment and administration

of Baeonsfield, as well as the public role which the

park plays in the community, compels the conclusion

that the Fourteenth Amendment forbids the present

and any future trustees or operators of the park in its

present form to exclude any person on account of his

race. Of. Eaton v. Grubbs, 329 F. 2d 710 (C.A. 4).10

0 Cf. Civil Bights Cases, supra.

10 The question whether racial discrimination by the private

trustees of Baeonsfield is forbidden by the Fourteenth Amend

ment is fully ripe for decision by this Court in this case—as

may not have been true in the second Girard Trust case {Penn

sylvania v. Board of Trusts, 357 IJ.S. 570). A fter this Court

-held in its first decision (Pennsylvania 'v. Board o f Trusts, 353

U.S. 230) that the City o f Philadelphia could not, as trustee

o f Girard College, exclude Negroes as directed in the trust

instrument, the State court appointed private trustees to re

place the city. See Girard College Trusteeship, 391 Pa. 434,

138 A.2d 844. The Negro plaintiffs again appealed to this

Court; but this time the Court, without opinion, dismissed the

appeal and, treating the appeal as a petition for a writ of

certiorari, denied certiorari. The reason for the Court’s action

in declining to review the State court’s decision can only be con

jectured. The Court’s disposition, however, was not on the

merits. The dismissal o f the apefkl, as in the first case, was

evidently for want of jurisdiction (see Pennsylvania v. Board,

of Trusts, 353 U.S. 230); and denial o f certiorari, o f course-, im

ports no view o f the merits. The explanation o f the Court’s

12

1. State Paternity and Superintendence.—A union

shop agreement between a labor union and an em

ployer-—both private entities—is subject to constitu

tional scrutiny where federal law authorizes the mak

ing of such agreements. Railway Employes’ Dept. v.

Hanson, 351 U.S. 225, 231-232. Likewise, a union is

forbidden to exclude Negroes where its authority to

act as exclusive bargaining agent derives from fed

eral law. Steele v. Louisville & N. R. Co., 323 U.S..

192; Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen v. Howard,

343 U.S. 768. The constitutional duty of equal treat

ment regardless of race has also been imposed on pri

vately owned transportation companies operating

under an exclusive franchise granted and closely regu

lated by the State (Public Utilities Comm’n v. Pol

iak, 343 U.S. 451; Baldwin v. Morgan, 287 F. 2d 750

(C.A. 5) ; Bomcm v. Birmingham Transit Go., 280 P.

2d 531 (C.A. 5 )), and upon privately owned hospitals

action may lie in the fact that, in view of a State antidiscrimi

nation enactment seemingly applicable to the private trustees o f

Girard College (Pa. Stat. Ann., Tit. 18, § 4654, expressly for

bidding racial discrimination bj? schools), it was not clear that

the private trustees would or could operate Girard on a segre

gated basis. I t was therefore premature to complain that the

appointment o f the private trustees rrould perpetuate racial

segregation. But it is entirely clear that the private trustees

of Baconsfield will continue to operate the park on a segregated

basis. The State courts have said they must, and there is no

applicable federal law requiring them to admit Negroes. (The

public accommodations provisions o f the Civil Bights Act of

1964, 78 Stat. 241 et seq., do not cover parks. See § 201(b)

( l ) - ( 4 ) . ) It is thus indisputable here, as it may not have been

in the Girard Trust case, that the effect under State law of the

State’s action in procuring the appointment of private trustees

will be to compel adherence to the racial limitation of the trust.

13

operating under comprehensive State plans to provide

medical facilities for the State’s citizens (.Simkins v.

Moses E . Cone Memorial Hospital,, 323 F. 2d 959

(C.A. 4), certiorari denied, 376 TT.S. 938; Eaton v.

Grubbs, 329 F. 2d 710 (C.A. 4 )).

The primary rationale of such decisions in that the

State may become so intimately involved in the creation

and regulation of an enterprise as to make it (though

privately owned) an agent of the State. Such an.

enterprise—in reality the State’s creature—is not

permitted to avoid the restrictions placed by the

Fourteenth Amendment upon State action; nor should

persons be compelled to suffer discrimination because

governmental ends are thus achieved through nom

inally private arrangements.

The charitable trust in general, and the charitable

trust for park purposes in particular, are, in Georgia

as well, as other States, a form of “private” enter

prise bearing substantial indicia of State paternity

and superintendence. In Georgia, the type of trust

created by Senator Bacon-—establishing a park to lie

operated by a municipality—is expressly authorized

by statute (Ga. Code Ann. §69-504). Georgia law

additionally provides for the enforcement of chari

table trusts in equity (Ga. Code Ann. § 108-201) and

specially empowers the State Attorney General to

enforce them (Ga. Code Ann. § 108-212 (1963

Supp.)); further, as this case shows, equity courts

are empowered to appoint new trustees to prevent a

charitable trust from failing. Georgia law also pro

vides favorable rules of construction designed to up-

-'3787-479—61

14

hold the validity of an attempted charitable trust

(Ga. Code Ann, § 108-206-09), waives the Rule

Against Perpetuities (Ga. Code Ann. § 69-504; see

Regents of University System v. Trust Go. of Geor

gia, 186 Ga. 498, 198 S.E. 345; Pace v. Dukes, 205 Ga.

835, 55 S.E. 2d 367), and grants immunity for negli

gent torts (Morehouse College v. Russell, 219 Ga. 717,

135 S.E. 2d 432; Cox v. DeJarnette, 104 Ga. App. 604,

123 S.E. 2d 16).

These special privileges (and others, see, e.g., p. 15,

infra) undoubtedly derive in large part from the fact

that, like a municipal transit system, or a labor union

having broad statutory powers, or a private hospital

operating under a comprehensive State health plan, a

charitable trust is typically engaged in activity in

which there is a high degree of public interest. Since

health, recreation, and education are among the cen

tral responsibilities of the States to their citizens, the

charity hospital, the charitable park (like Baeons-

field), charitable museums and libraries, and non

profit private schools act for the State in the pursu

ance of public goals.11 The State fosters private insti

tutions of this kind, providing; them with special priv

ileges and benefits, because without such institutions

the direct obligations of the State to provide for the

welfare of its citizens would be expanded. Such spon

sorship is a form of “ interdependence” between the

public and the private sectors and creates a pattern

of “benefits mutually conferred”' (Burton v. Wil- 11

11 Sometimes in areas, like sectarian education, which the

.States are constitutionally barred from entering.

15

mington Parking Authority, 365 U.S. 715, 724-725).

The State grants the charity special advantages to

encourage it to assume public responsibilities. The

private charity in turn assumes an essentially public

function which the State might otherwise have to per

form directly, and thereby acquires substantial attri

butes of a public rather than a private institution.

2. State Support and Maintenance— This Court has

said that affirmative “ State support of segregated

* * * [activity] through any arrangement^, manage

ment, funds, or property cannot be squared with the

[Fourteenth] Amendment’s command” (Cooper v.

Aaron, 358 U.S. 1, 19). In this case, the State is sig

nificantly involved in the support of Baconsfield

within the sense of this doctrine.

First, it grants Baconsfield, in common with other

charitable trusts, exemption from taxation (see Ga.

Code Ann. § 92-201), thus affording it appreciable

financial assistance difficult to distinguish from an

outright subsidy. “ Tax exemption may attain sig

nificance when viewed in combination with other at

tendant state involvements.” Eaton v. Grubbs, 329

F. 2d 710, 713 (C.A. 4) ; see Kerr v. Enoch Pratt Free

Library, 149 F. 2d 212 (C. A. 4) ; Simkins v. Moses H,

Cone Memorial Hospital, supra; Guillory v. Adminis

trators of Tulane University, 203 F. Supp. 855, 863

(E.D. La.).

Second, the State has chosen and appointed the

trustees who govern Baconsfield and these trustees

are, in turn, answerable to the State court which ap

16

pointed them and which exercises a continuing super

visory authority over the administration of the trust.

Third, for many years the City itself was the trus

tee. The Baeonsfield of today is thus a product in

substantial measure of actions taken and decisions

made during the City’s direct custodianship. In addi

tion, three of the City’s former park managers are

members of the new Board of Managers designated by

the court-appointed trustees. The close support and

supervision which the City has provided have not been

dissipated.

The State, in short, has not only encouraged the

creation of Baeonsfield to serve a public purpose, but

to that end it has lent and continues to lend significant

financial support and administrative supervision to the

park.

3. The Public Character of the Park.—Even with

out the kind of State support and sponsorship dis

cussed in sections (1) and (2) above, a private person

or group permitted by the State to perform a func

tion normally performed largely by government oc

cupies a position comparable to that of a formal

agency of the State.12 Hence, the exercise of consti

tutionally protected rights on the public streets of a

town may not lie denied by a private company that

owns the town and its streets; a State is not justified

in “ permitting a corporation to govern a community

of citizens so as to restrict their fundamental liber

12 “When private individuals or groups are endowed by the

State with powers or functions governmental in nature they

become instruments of the State and subject to the same con

stitutional limitations as the State itself.” Baldwin v. Morgan,

supra.; at 755, n. 9.

17

ties” (Marsh- v. Alabama, 326 U.S. 501, 509). I f the

State delegates an aspect of the elective process to-

the control of private groups, those groups become

subject to the Fifteenth Amendment. Terry v. Ad

ams, 345 U.S. 461; Smith v. AUwright, 321 U.S. 149;

Nixon v. Condon, 286 U.S. 73; Bice v. Elmore, 165

F. 2d 387 (C.A. 4). Similarly, where private real

estate developers are permitted to impose systems of

restrictive covenants, which have substantially the

same effects as municipal zoning regulations, the State

courts are forbidden to enforce racial restrictions con

tained in such covenants. Shelley v. Kraemer, 334

U.S. 1; Barrows v. Jackson, 346 U.S. 249; see Bell v.

Maryland, 378 U.S. 226, 329 (dissenting opinion).13

Baeonsfield is not an entire “ private” community

as in Marsh v. Alabama, or a large residential subdi

vision as in Shelley v. Kraemer. Nor is the public

recreational function it serves as vital to the purposes

of State government as the “ private” elective process

involved in Terry v. Adams, Smith v. Allwright, and

13 The principle of the Marsh case lias been applied in a

variety of additional contexts: union activity on private com

pany property (Republic, Aviation Gory. v. National Labor Re

lations Board, 824 U.S. 793; National Labor Relations Board v.

Stowe Spinning Go., 386 U.S. 2-26; National Lai or Relations

Board v. Labe Superior Lumber- Gory., 167 F. 2d 147 (C.A.

6 ) ) ; private colleges ( Guillory v. Administrators o f Tvlane.

University, 203 F. Supp. 855, 859 (E.D. La. ) ) ; private railroad

terminals (Baldwin v. Morgan, 287 F. 2d 750, 754-755 (C.A.

5 ) ) ; the sidewalks of shopping centers (Freeman v. Retail

Clerks Local 1207, 28 U.S. Law Wk. 2311 (Kings County

Super. Ct., Washington, decided^December 9, 1959)) ; and pri

vate transit companies (.Public Utilities Comm'n v. Poliak, 343

U.S. 451; Boman v. Birmingham Transit Go., 280 F. 2d 531 (C.A.

5)) .

18

Nixon v. Condon. Nevertheless, the principle of these

decisions-—that a private organization which assumes

a substantially governmental character must obey the

restrictions placed by the Constitution upon govern

mental action—applies to a significant extent to

Baconsfield.

:. (a) The provision of parks for the leisure and rec

reation of urban dwellers is a traditional function of

local government. “ In densely populated cities, pub

lic parks are manifestly essential to the health, com

fort and pleasure of their citizens, and it is generally

held that municipalities may acquire land for park

purposes.” 10 McQuillin, Municipal Corporations

(3d ed.), § 28.51, p. 123. The State of Georgia ex

plicitly authorizes its municipalities to acquire land

for parks, playgrounds and other recreational pur

poses, and to provide for their conduct and main

tenance. (Georgia Code Ann. § 69—602; see Stubbs v.

City of Macon, 78 Ga. App. 237, 50 S.E. 2d 866.)

.Baconsfield is one of the largest parks in Macon with

a distinctly public character. It is 100 acres in size

/and centrally located. The park contains several

fstreets which connect with the public streets surround-

| ing the park, and is traversed by a major highway.

! It is an integral part of Macon’s park system; if it

were closed, the city might well he forced to acquire

j additional park land to replace it. The existence of

several privately endowed parks like it might actually

dissuade a city from providing any recreational areas

of its own—areas which it would, of course, be consti

tutionally forbidden to operate on a segregated basis.

19

■(b) Apart from its physical characteristics, Baeons-

field’s public nature is shown by its admissions

policy which—unlike that of a private activity—lacks

all selectivity (except as to race) with respect to those

who are permitted to use the property. There are no

qualifications for participation in the use of Bacons-

field's facilities, no admission fees, and. no member

ships or membership requirements. In contrast to

a specialized recreational area sponsored by a group

that has special interests which bring its members to

gether, Baeonsfieid is designed to serve the entire

community of Macon. “The more an owner, for his

advantage, opens up his property for use by the pub

lic in general, the more do his rights become circum

scribed by the statutory and constitutional rights of

those who use it.” Marsh v. Alabama, 326 U.S. 501,

506.

(c) That Baeonsfieid serves a municipal function is

also strongly suggested by the fact that the Mayor

and the Council of Macon were designated as trustees

in the trust instrument and served in that capacity for

many years. Senator Bacon intended Baeonsfieid to

be a public area serving the entire community. Pre

sumably, it was to assure its public character and its

community function that he made the City responsible

for its management and control. In exercising this

function, the City confirmed the municipal character

of the park.

(d) It is now a settled principle that the lessee or

operator of public property may not exclude persons

20

from such property on racial grounds.14 This holds

true even when the State has only bare legal title and

is merely enforcing a racial limitation in a trust in

strument. See Pennsylvania v. -Boat'd of Trusts, 35o

U.S. 230. It seems apparent that a vital reason behind

this rule is to erase the image of discriminatory

government.

Regardless of the underlying technical arrangement,

the appearance of Baconsfield is that of a municipal

facility. The City of Macon managed Baconsfield for

many years. For all intents and purposes it was a

municipal park; and, in appearance and character, it

remains indistinguishable from other municipal parks.

The appointment of private trustees has not changed

this. I f Baconsfield remains segregated, whatever the

technicalities of the trust arrangement, it will have

the appearance of a segregated public facility and be

regarded as such Dy a substantial segment of the

community.

4. Impact upon Racial Minorities.—One of the ele

ments which may be weighed in assessing State in

volvement in nominally private discrimination is the

discrimination’s probable impact on the affected

14 See Burton v. Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U.S. 71.5;

Muir v. Louisville Park Theatrical Ass'n, 347 U.S. 971, re

versing 202 F. 2d 275 (C.A. 6 ); Derrington v. Plummer, 240

F. 2d 922 (C.A. 5), certiorari denied, 353 U.S. 924; Depart

ment of Conservation & Development v. Tate, 231 F. 2d 615

(C.A. 4) ; Smith v. Holiday Inns of America, Inc., 220 F. Supp.

1 (M.D. Term.); Coke v. City of Atlanta-, 184 F. Supp. 579

(N.D. G a .); Jones v. Ma-rva. Theatres, Inc., 180 F. Supp, 49

(D. M d .); Nash v. A ir Terminal Services, 85 F. Supp. 545 (E.

D. Y a .) ; Lawrence v. Hancock, 76 F. Supp. 1004 (S.D. W . Va.).

21

minority. Where a “ private” discriminatory ar

rangement has the same degree of impact upon a

minority group as if such discrimination were prac

ticed by a governmental unit, strong reasons are pres

ent for applying the standards of the Fourteenth

Amendment. Undoubtedly an important factor in

the Court’s decision in Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 U.S.

1, p. 17, supra, was that racially restrictive covenants

are not isolated or localized but, on the contrary, >

broad and far-reaching in their impact. A system of

such covenants blankets a neighborhood with uniform

restrictions. Its natural, tendency is to create ghettos.

It thereby curtails radically the opportunities of the

excluded minority group, in a manner and to an

extent ordinarily effected only by governmental action.

See Bell v. Maryland, 378 IT.S. 226, 329 (dissenting

opinion) ; cf. Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U.S. 60. The

restriction imposed has an even more pervasive charac

ter when, as in Shelley v. Kraemer> it is binding not

only on one generation, but on future generations as

well; communities may consequently be frozen for long

periods of time along rigid racial lines. Effects so

profound and enduring are, so far as the prejudiced

minority is concerned, equivalent to those produced

by legislative action. Clearly, their magnitude far

exceeds that of ad hoc private discrimination.

As a major public recreational facility reserved in

perpetuity for whites, Baconsfield shares important

characteristics with the perpetually restricted resi

dential community in Shelley v. Kraemer. It would

be anomalous in the extreme if Baconsfield, a facility

22

serving, a community-wide function, could constitu

tionally be preserved in perpetuity as a park barred to

Negroes, when private owners of surrounding prop

erty are precluded by Shelley from enforcing racial

covenants. Even more important than the impact

upon Negroes of an individual public facility to which

they can never have access are the wider implications

if the restricted operation of Bacon sfield is approved.

To the extent that the white, but not the Negro, com

munity is served by restricted facilities like Bacons-

field, there is correspondingly less incentive for the

community to provide adequate facilities to which

Negroes would have access. I f the present arrange

ment is permissible in Macon, what is to prevent a

iBaeonsfield in a community where there is only one

park? Or, indeed, what is to prevent the provision

of other essential public services through racially re

strictive private endowments, and a concomitant re

gression in the operation or creation of municipally

owned and State-owned facilities open to Negroes?

As these questions suggest, discrimination by the

establishment of a perpetual charitable facility serv

ing a public purpose and open to all hut Negroes with

out charge has more serious portents for the excluded

minority than most forms of “ private” discrimina

tion. I f Negroes are denied access to a particular

commercial establishment, the forces of competition

will ordinarily induce other establishments to provide

the service. But if they are denied the use of free

hospitals, parks, libraries, or schools, they may well

end up denied access to alh or substantially all such

facilities. Private enterprise will not proride such

facilities; they are provided hv government or by

charitable endowments or not at all. Moreover, they,

typically require substantial capital investments and

highly specialized skills and training, and few Negro

communities will be able to donate the requisite funds

and skills. A Negro “ Baconsfield” is not a likely

response to the white-only Baconsfield—even if that

were a solution which could commend itself to a demo

cratic society.

5. State Involvement in the Decision to Discrimi

nate.— State discrimination within the meaning of the

Fourteenth Amendment occurs whenever the State ac

tually participates in or significantly influences private

decisions to discriminate. See Peterson v. Greenville,

373 ILS. 244; Lombard v. Louisiana, 373 TT.S. 267;

Robinson v. Florida, 378 ILS. 153. At a number of

points in the history of the Baconsfield trust, the State

has thus become involved in the actual implementa

tion of racial discrimination. To some extent, this

involvement persists.

(a) Georgia Code Ami. § 69-504 permits any per

son to grant a municipal corporation lands in trust

“ dedicated in perpetuity to the public use as a park,

pleasure ground, or for other public purpose, and in

said conveyance * * * [to] provide that the use of said

park, pleasure ground, or other property so conveyed

to said municipality shall be limited to the white race

only, or to white women and children only * *

Section 69-505 authorizes municipal corporations to

accept such grants and enforce the racial limitation

24

by the police power. These statutes were in effect

when Senator Bacon executed his will, and the lan

guage in which he created the trust was in part bor

rowed from § 69-504. In this sense, the present case

parallels Lombard v. Louisiana, supra, where public

officials encouraged private restaurants to exclude

Negroes. See, also, Burton v. Wilmington Parking

Authority, 365 U.S. 715, 726-727 (concurring opinion).

(h) For many years after the establishment of

Baconsfield, the City itself managed the park. Dur

ing most of this period, it systematically excluded

Negroes. This was unconstitutional State action,

jPennsylvania v. Board of Trusts, 353 U.S. 230. More

important in the present context, however, this past

State action may well be directly responsible for the

present status of Baconsfield. I f the City had not

thus unconstitutionally administered Baconsfield as

a park for whites only during this long period, it is

conceivable that the park, administered privately,

would by this time have become an integrated facility.

Or, if the failure of the City as trustee had led in

stead to the withdrawal of Baconsfield from public

park use, the City might itself have acquired substitute

park property, which it would now be compelled to

make available to Negroes on a basis equal with whites

(see, also, n. 15, infra, pp. 25-26).

(c) When the City realized it could no longer con

stitutionally exclude Negroes from Baconsfield, it

began to admit them. Thereupon the Board of Man

agers of Baconsfield—appointed by the City and a

part of the city administration—sued to procure the

25

appointment of private trustees who would resume

the practice of exclusion. This, suit, which was not

prompted by any private complaint, was also State

action. For, so far as appears, “hut for the active

intervention of the state courts, supported by the full

panoply of state power,” the Negro residents of

Macon “ would have been free to occupy the properties

in question.” Shelley v. Kraemer, 334 IT. S. 1, 19.

The clear purpose of the suit was to perpetuate racial

discrimination, the gravamen of the complaint being

that the City was “ failing and refusing to carry out and

enforce the provisions of * * * [Senator Bacon’s]

W ill with respect to the exclusive use” of the park

by white persons (R. 8). Absent the State’s action

here, there is strong basis to believe that Baeonsfield

would have been permitted to become an integrated

facility through the acquiescence of all interested

parties.15

16 To be sure, a beneficiary of the trust (i.e., a white person

who used the park) could have sued to enforce the racial limita

tion. See Duffee v. Jones, 208 Ga. 639, 68 S.E. 2d 699; Doming

v. Stanley, 162 Ga. 211, 133 S.E. 245; Harris v. Brown, 124 Ga.

310, 52 S.E. 610. But no such person evinced any interest in

suing. A citizen or taxpayer o f Macon who was not a bene

ficiary of the trust could not have sued {Flam s v. Brown,

supra), and we have found no Georgia case ruling that an

heir or residuary legatee of the settlor may enforce a charitable

trust; the general rule denies standing to the settlor, his heirs,

and contributors, to the trust. Greenway v. Irvine's Trustee,

279 Ivy. 632, 131 S.W. 2d 705; Leeds, v. Harrison, 15 A.J.

Super. 82, 83 A. 2d 45. O f course, an heir may sue to set

a trust aside and obtain the property himself by reversion.

Of. Silcox v. Harper, 32 Ga. 639; Gumming v. Trustees of

Reid Memorial-Church, 64 Ga. 105. But this, is a very differ

ent matter from enforcing the trust according to its original

26

(d) The City thereafter resigned as trustee. The

resolution of resignation (R. 60-61) makes clear that

its action in resigning was motivated principally, if

not exclusively, by a desire to perpetuate racial dis

crimination. Cf. (xomiUioii v. Light foot, 364 U.S.

339 ; Griffin v. School Board, 377 U.S. 218.

(e) The State court accepted the City’s resignation

and appointed private trustees to operate Baconsfield

on a segregated basis. The State Supreme Court

upheld the lower court’s action. Cf. Shelley v. Krae-

mer, supra. In short, the case is one where the State,

having administered Baconsfield as a segregated mu

nicipal institution for many years, has acted to trans

fer it to private j(dnds in order to perpetuate segrega

tion. In these circumstances, the State bears substan

tial responsibility for the racial discrimination now

enforced by the trustees, albeit they are nominally a

private body (see cases cited in n. 14, supra, p. 20).

6. The Effect upon Private Choice.—The Civil

Rights Cases, 109 U.S. 3, 11, distinguished between

State action subject to the Fourteenth Amendment

and purely “ [iIndividual invasions of individual

rights” , which the Amendment does not reach. This

distinction, uniformly followed (see, e.g., Burton v.

Wilmington Parking Authority, 365 U.S. 715, 722),

tenor. Faced with the prospect of losing Baconsfield to the

heh’S' of Senator Bacon, who might close the park and use the

land for other purposes, the City might decide to secure the

land by condemnation—in which event it would be constitu

tionally required to continue to operate it on a non-segregated

basis A t all events, the heirs o f Senator Bacon instituted no

suit, but merely joined belatedly in the suit brought by the

Board o f Managers.

27

recognizes that the Fourteenth Amendment, consist

ently with the spirit and institutions of American

life, leaves substantial freedom for private choice in

social, business, and professional activities and asso

ciations. The Amendment was not intended to raise

every instance of personal or private racial discrimi

nation to the constitutional level. Therefore, in de

termining its application in the disputed borderline

area of joint public and private responsibility, it is

relevant to consider evidence not only of affirmative

State involvement, but of the absence of a substantial

interest in protecting the area of truly private choice

that the Amendment does not penetrate.

A finding of State action in this case would not in

trude upon that area. No issue is presented here as

to a property owner’s right to decide whom to permit

on his premises; and the only private choice effectu

ated by enforcing the racial limitation in the trust

would be that of Senator Bacon, who died many years

ago. So far as the living are concerned, Baeonsfield

is not a private facility used in a private way but a

public facility open to all except: Negroes. Even less

than most commercial establishments, Baeonsfield is

not a place of intimate or private associations. As a

public park open to all (except Negroes), it is a place

of strictly transient and casual encounters. It has

none of the aspects of a private home or club, where

there is a compelling interest in permitting people to

be free to choose those with whom to associate. More

over, the decision to exclude Negroes was not made by

28

anyone using the park and, for all that appears, there

was not even a complaint from the white users when

the City admitted Negroes to Baconsfield.

In sum, Baconsfield is, except for its exclusion of

Negroes, a truly municipal facility serving a public

purpose. The State has not only created the legal

framework within which such “ private” charitable

institutions are established to serve public functions,

but it lends them its direct support. In this case, in

addition, the State has been intimately involved in

the actual discriminatory operation of Baconsfield:

The City of Macon administered the park for many

years as a facility for whites only—thus inevitably

shaping its present character—and this very suit is an

example of affirmative State action recently taken to

preserve Baconsfield as a public facility entitled to

exclude Negroes while admitting all others. The

consequence of Baconsfield’s continued existence as a

segregated facility will be not only to deprive Negroes

of equal access to public parks in Macon; there is

danger that similar “private” operation of addi

tional public facilities will deprive Negroes of other

public services freely available to whites. All of these

considerations, as well as the fact that Baconsfield s

public character negates any substantial interest in

private choice which would be adversely affected

should the Fourteenth Amendment be held to apply,

lead us to conclude that Baconsfield should be treated

as a public institution of a governmental character re-

29

quired by the Constitution to admit persons without

regard to their race.16

CONCLUSION

The judgment of the Supreme Court of Georgia,

holding that the trustees of Baconsfleld are legally

obligated, and constitutionally permitted, to exclude

Negroes on grounds of race or color, should be

reversed.

Respectfully submitted.

T hurgood M arshall,

Solicitor General.

J ohn D oar,

Assistant Attorney General.

R alph S. Spritzer,

P aul B ender,

R ichard A . P osner,

Assistants to the Solicitor General.

D avid R ubin ,

J ames L. K elley,

P aul S. A dler,

Attorneys.

September 1965.

16 While it is clear, if our views are accepted by the Court,

that no one mav operate Baconsfleld as a segregated park, we

think it would*be premature for this Court to consider (1)

whether the heirs o f Senator Bacon may obtain the property

by reversion and use it for non-park purposes (e.g., a resi

dential development); or (2) whether the present trustees may

close the park. W e note, however, that both courses o f action

would raise constitutional questions. As to the first, see Gv/d-

Imy v. Administrators o f Tutane University, 212 F. Supp. 674,

687 (E.D. L a .) ; cf. Barrows v. Jackson, 846 U.S. 249, 254; as

to the second, see Griffin v. School Board, 377 U.S. 218.

U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE: 1965