Firefighter Local Union No. 1784 v. Stotts Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

October 27, 1983

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Firefighter Local Union No. 1784 v. Stotts Brief Amicus Curiae, 1983. 56d088c0-b19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/bf80da59-ad5b-4837-a1cd-f97aaa09d3ca/firefighter-local-union-no-1784-v-stotts-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 28, 2026.

Copied!

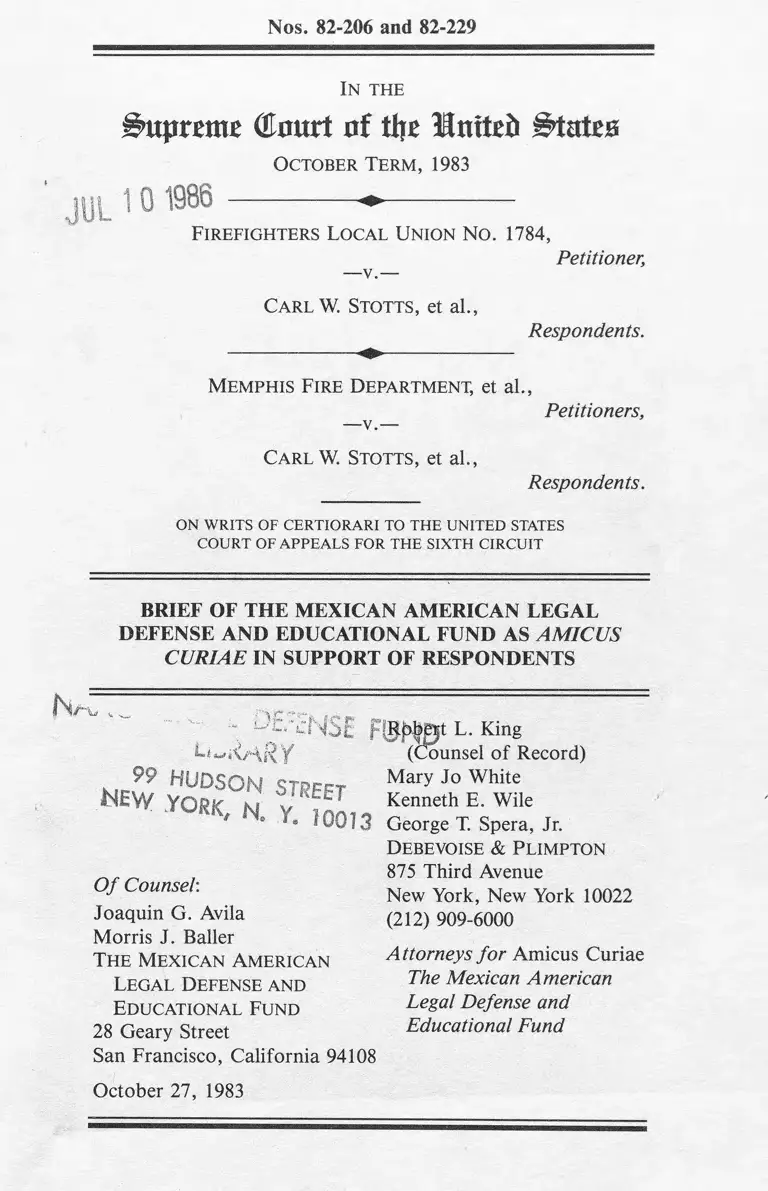

Nos. 82-206 and 82-229

In the

Supreme (Court of tire Unit zb Staten

October Term , 1983

jljl \ Q 1988 ---------------♦ ---------------

Firefighters Local Union No . 1784,

-v.-

Ca r l W. Stotts, et al.,

Petitioner,

Respondents.

Memphis Fire Department, et al.,

Petitioners,—-v.—

Ca r l W. Stotts, et al.,

Respondents.

ON WRITS OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF OF THE MEXICAN AMERICAN LEGAL

DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND AS AMICUS

CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF RESPONDENTS

IN.

Ai U t

- t f

tiEW y S O N s t r e e t

w y0RK< N. Y. I00T3

O f Counsel:

Joaquin G. Avila

Morris J. Bailer

The Mexican American

Legal Defense and

Educational Fund

28 Geary Street

San Francisco, California 94108

'b 0 t L. King

(Counsel of Record)

Mary Jo White

Kenneth E. Wile

George T. Spera, Jr.

Debevoise & Plimpton

875 Third Avenue

New York, New York 10022

(212) 909-6000

Attorneys fo r Amicus Curiae

The Mexican American

Legal Defense and

Educational Fund

October 27, 1983

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES................... iii

INTEREST OF THE MEXICAN AMERICAN LEGAL

DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND. . . . . . . . . . 1

INTRODUCTION ......................................... 2

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT............................... 3

ARGUMENT:............................................. 5

I. The District Court Had the Power To Modify the

1980 Decree and Properly Exercised That Power 5

II. Title VII Mandates the Relief Awarded in the

Preliminary Injunction......................... 10

A. Section 706(g) of Title VII Does Not Limit

Relief to Adjudicated Victims of Discrimina

tion ............. 10

B. The Relief Granted in the Preliminary Injunc

tion Did Not Impermissibly Interfere with the

Operation of a Seniority System............... 18

CONCLUSION................... 24

Ill

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases page

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405 (1975) . .10, 11,

20

Alexander v. Gardner-Denver Co., 415 U.S. 36 (1974).. 12

Baker v. City o f Detroit, 483 F. Supp. 930 (E.D. Mich.

1979), a ff’d sub nom. Bratton v. City o f Detroit, 704

F.2d 878 (6th Cir.), modified, 712 F.2d 222 (6th Cir.

1983)............. 13

Berkman v. City o f New York, 705 F.2d 584 (2d Cir.

1983)......................... 11

Bonner v. City o f Pritchard, 661 F.2d 1206 (11th Cir.

1 9 8 1 ) . . . . . ....................................................................... 12

Boston Chapter, N.A.A.C.P., Inc. v. Beecher, 504 F.2d

1017 (1st Cir. 1974), cert, denied, 421 U.S. 910 (1975) 11

Boston Chapter, NAACP v. Beecher, 679 F.2d 965 (1st

Cir. 1982), vacated and remanded fo r a determination

o f mootness, 103 S. Ct. 2076 (1983) .......................... .. 9, 20

Bratton v. City o f Detroit, 704 F.2d 878 (6th Cir.),

modified, 712 F.2d 222 (6th Cir. 1983).................. 12

Brown v. Neeb, 644 F.2d 551 (6th Cir. 1981).................. 9

Brown v. Swann, 35 U.S. (10 Pet.) 497 (1836).............. 10

Carson v. American Brands Inc., 450 U.S. 79 (1981).. . 12

Carter v. Gallagher, 452 F.2d 315 (8th Cir. 1971), cert,

denied, 406 U.S. 950 (1972) .......................................... 12

Chisholm v. United States Postal Service, 665 F.2d 482

(4th Cir. 1981)........................................................... ...10 , 12

Chrysler Corporation v. United States, 316 U.S. 556

(1942)............................................................................. 5, 6, 7

IV

City o f Alcoa v. International Brotherhood o f Electrical

Workers Local 760, 203 Tenn. 12, 308 S.W. 2d 476

(1958)............................................................................... 18

Davis v. County o f Los Angeles, 566 F.2d 1334 (9th Cir.

1977), vacated as moot, 440 U.S. 625 (1979)......... 12

EEOC v. American Telephone and Telegraph Co., 556

F.2d 167 (3d Cir. 1977), cert, denied, 438 U.S. 915

(1978)................................................................... 12, 13, 14, 15

Environmental Defense Fund, Inc. v. Castle, 636 F.2d

1229 (D.C. Cir. 1980)..................................................... 7

Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co., 424 U.S. 747

(1976)........................................ 4, 11, 18, 19, 21, 22, 23

Gautreaux v. Pierce, 535 F. Supp. 423 (N.D. 111. 1982) 6

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971)............ 14

International Brotherhood o f Teamsters v. United

States, 431 U.S. 324 (1977) . . . .4, 11, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 23

Kirke la Shelle Co. v. Armstrong, 263 N.Y. 79, 87, 188

N.E. 163, 167 (1933)..................................................... 7

Luevano v. Campbell, 93 F.R.D. 68 (D.D.C. 1981) . . . . 7

McKenzie v. Sawyer, 684 F.2d 62 (D.C. Cir. 1982)........ 11

NAACP v. Allen, 493 F.2d 614 (5th Cir. 1974).............. 11

Prate v. Freedman, 583 F.2d 42 (2d Cir. 1978)................10, 12

Stotts v. Memphis Fire Department, 679 F.2d 541 (6th

Cir. 1982), cert, granted, 103 S. Ct. 2451 (1983)........ 8, 13

United States v. Armour & Co., 402 U.S. 673 (1971)... 6

United States v. Bethlehem Steel Corp., 446 F.2d 652 (2d

Cir. 1971) ................................... ......................... 21

United States v. City o f Alexandria, 614 F.2d 1358 (5th

Cir. 1980)................................................................... 10, 12, 15

PAGE

V

PAGE

United States v. City o f Chicago, 549 F.2d 415 (7th Cir.

1977)................................................................................. 12

United States v. City o f Miami, 664 F.2d 435 (5th Cir.

1981) (en banc)............................................................... 21

United States v. Ironworkers, Local 86, 443 F.2d 544

(9th Cir.), cert, denied, 404 U.S. 984 (1971)................ 17

United States v. IT T Continental Baking Co., 420 U.S.

223 (1975)......................................................................... 7

United States v. Lee Way Motor Freight Inc., 625 F.2d

918 (10th Cir. 1979)....................................................... 12

United States v. Swift & Co., 286 U.S. 106 (1932)........ 5, 6

United States v. United Shoe Machinery Corp., 391 U.S.

244 (1968)..................... 6

United Steelworkers o f America v. Weber, 443 U.S. 193

(1979)............................................. 17

Statutes

Civil Rights Act of 1964, Title VII, Pub. L. 88-352, 88th

Cong., 2d Sess., 78 Stat. 253 (1964), codified (as

amended) at 42 U.S.C. § 2000e et seq......... ............ passim

Section 703(h), 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(h)...................... .18, 19

Section 704(a), 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-3(a)........................ 14

Section 706(g), 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(g)..........10, 13, 14, 15,

16, 18, 22

Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1972, Pub. L.

92-261, 92d Cong., 2d Sess., 86 Stat. 103 (1972),

codified (as amended) ai 42 U.S.C. § 2000e et seq. .. 17

VI

Miscellaneous

110 Cong. Rec. (1964):

p. 2567 ....................................................................... 14, 15, 16

p. 6548 .......... ................................................................ . 17

p. 7214............. 16

118 Cong. Rec. (1972):

pp. 1671-75 .......................... 17

p. 3460 ....................... 17

p. 7168................... 10

H.R. 7152, 88th Cong., 1st Sess. (1963).......................... 15

H.R. Rep. No. 914, 88th Cong., 1st Sess. (1963).......... 15

Burton, Breach o f Contract and the Duty to Perform in

Good Faith, 94 Harv. L. Rev. 369 (1980)............ 7, 8

Vaas, Title VII: Legislative History, 7 B.C. Indus. &

Com. L. Rev. 431 (1966).... ................ ....................... 14

PAGE

In the

Suprem e © curt o f ttjr l&nxtzb States

October Term, 1983

Nos. 82-206 and 82-229

Firefighters Local Union No . 1784,

Petitioner,

Ca r l W. Stotts, et al.,

Respondents.

Memphis Fire Department, et al.,

Petitioners,

Ca r l W. Stotts, et al.,

Respondents.

ON WRITS OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF OF THE MEXICAN AMERICAN LEGAL

DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND AS AMICUS

CURIAE IN SUPPORT OF RESPONDENTS

INTEREST OF THE MEXICAN AMERICAN LEGAL

DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND

The Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational

Fund (“MALDEF”) is a national organization dedicated to

achieving equal employment opportunities for Mexican Ameri

cans and other Americans of Hispanic heritage. MALDEF has

pursued this objective in part by serving as counsel of record in

employment discrimination actions. It has also presented its

views, as amicus curiae, to the United States Courts regarding

2

employment discrimination issues of importance to Hispanics.

The availability of the relief directed by the District Court in

this case and challenged on this appeal is such an issue.

Hispanics, like blacks, endure the persistent effects of em

ployment discrimination throughout the United States. His

panics who aspire to the equality of employment opportunities

guaranteed by Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 must

have some assurance that gains in hiring and employment won

through litigation will not be eradicated by an employer’s

response to developments unforeseen at the time of suit. In this

case, the Court is called upon to review a district court decree

that protects gains in minority hiring and promotion threat

ened by circumstances arising after entry of a consent decree

settling a Title VII action. In light of the importance of this

issue for the Hispanic community, MALDEF submits this brief

urging affirmance of the decision below.1

INTRODUCTION

At issue on this appeal is the power of a federal district court

to preserve legally mandated gains in the hiring and promotion

of minorities, made pursuant to a judicially enforceable con

sent decree, when those gains will be substantially diminished

by an employer’s actions in response to circumstances unfore

seen when the parties entered into the decree.

Two separate actions, one a Government pattern and prac

tice suit initiated by the Department of Justice in 1974 and the

other a private class action filed by Respondent Carl W. Stotts

in 1977, were brought against the City of Memphis and its Fire

Department (hereinafter collectively referred to as “ the City” )

under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C.

§ 2000e et seq., and related statutes. In both cases, the parties

reached negotiated settlements. These settlements were em

bodied in consent decrees (the “ 1974 Decree” and the “ 1980

Decree” , respectively) that commit the City to the goal of

1 The parties have consented to the submission of this brief, and their

letters of consent have been filed with the Clerk of the Court pursuant to

Rule 36.2 of the Rules of this Court.

3

achieving, within each job classification in the Fire Depart

ment, minority representation approximating the minority rep

resentation in the civilian labor force. Partial, but by no means

complete, achievement of this goal had been attained by 1981

when an unforeseen change in the economic climate prompted

the City to initiate a lay-off program. If implemented, this

program would have substantially undone the gains in minority

hiring and promotions that had been made under the decrees.

After the program was announced, the private plaintiffs

sought equitable relief solely to preserve the partial remedy

already accomplished. The result was the preliminary injunc

tion at issue here, which enjoins the City from applying its

lay-off program to decrease the percentage of blacks in certain

job classifications within the Fire Department.2

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

Under longstanding precedent, the district courts possess the

authority to modify a consent decree in light of unforeseen

circumstances that have arisen following its entry. This equita

ble power is properly exercised when, as here, a change in

circumstances threatens to frustrate the remedial program set

forth in the decree. The seniority-based layoffs proposed by

the City of Memphis for its Fire Department would have

reversed the progress made in hiring and promoting blacks into

positions from which they had historically been excluded. The

District Court, in a careful exercise of its equitable discretion,

entered a preliminary injunction that preserved the status quo

by preventing the City from reducing the percentage of blacks

within each Fire Department rank pending a hearing on the

merits. This limited relief falls squarely within the equitable

power of the court to preserve the efficacy of the earlier

remedial order.

2 MALDEF joins in Respondents’ argument that, because those white

employees laid off due to the preliminary injunction were reinstated shortly

thereafter, the case is now moot.

4

The relief ordered in the preliminary injunction is fully

consistent with the broad remedial scope of Title VII. The

preliminary injunction preserves the relief ordered in the con

sent decree, but imposes no additional burdens on defendants.

Because the 1980 Decree was designed to eliminate the present

effects of past discrimination, the preliminary injunction

plainly falls within the authority of the courts under Section

706(g) of Title VII, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(g), to order all

appropriate “ affirmative action.” Title VII relief, moreover, is

not limited to adjudicated victims of discrimination; Peti

tioners’ argument to the contrary is contradicted by the legisla

tive history of Section 706(g) and by numerous decisions of the

federal courts.

The preliminary injunction is not prohibited by Title VII

even though it affects the expectations of white employees. The

intrusion is minimal. Since Franks v. Bowman Transportation

Co., 424 U.S. 747 (1976), and International Brotherhood o f

Teamsters v. United States, 431 U.S. 324 (1977), grants of

permanent retroactive seniority have been widely available

when necessary to fulfill the objectives of Title VII, even where

employees enjoy seniority benefits under a bona fide seniority

plan. The equitable relief ordered by the District Court was

necessary to preserve the effectiveness of the remedy previously

ordered and intrudes far less on the operation of seniority than

does the remedy of full permanent retroactive seniority autho

rized in Franks and Teamsters.

Because the District Court neither abused its discretion nor

exceeded its authority, its entry of the preliminary injunction

should be affirmed.

5

ARGUMENT

I. t h e d is t r ic t c o u r t h a d t h e p o w e r to

MODIFY THE 1980 DECREE AND PROPERLY EX

ERCISED THAT POWER

The Court of Appeals, in sustaining the District Court’s

preliminary injunction, ruled both that the relief was based

on a proper construction of the 1980 Decree as written

and, alternatively, that the injunction fell within the equita

ble power of a court to modify a consent decree in light

of changed circumstances. Assuming that the preliminary-

injunction does in fact “modify” the original decree, the

Court of Appeals was clearly correct in its ruling.

It is a principle of longstanding that a district court has

the power to modify a consent decree in light of changed

circumstances “to adapt its restraints to the needs of a

new day.” United States v. Swift & Co., 286 U.S. 106, 113

(1932). As Justice Cardozo wrote for the Court: “We are

not doubtful of the power of a court of equity to modify

an injunction in adaptation to changed conditions though

it was entered by consent.” Id. at 114. This power is “in

herent in the jurisdiction of the chancery,” id., and exists

whether or not the decree expressly reserves to the court

the authority to modify the decree, id.; see Chrysler Cor

poration v. United States, 316 U.S. 557, 567 (1942)

(Frankfurter, J., dissenting). It is appropriately exercised

where a change in circumstances prevents the decree from

achieving the remedy agreed upon by the parties.

A district court’s exercise of its power to modify a con

sent decree will be overturned only if entry of the modifi

cation amounts to an abuse of discretion. This Court, in

Chrysler Corporation v. United States, defined the narrow

scope of review as follows:

The question is whether the change . . . amounted to an

abuse of this power to modify. We think that the test to be

applied in answering this question is whether the change

served to effectuate or to thwart the basic purpose of the

original consent decree.

6

316 U.S. at 562. Applying this test in United States v. United

Shoe Machinery Corp., 391 U.S. 244 (1968), the Court held

that where a decree has failed to achieve its “principal ob

jects,” it is appropriate “to prescribe other, and if necessary

more definitive, means to achieve the result.” Id. at 251-52.3

As noted in Gautreaux v. Pierce, 535 F. Supp. 423, 426 n.7

(N.D. 111. 1982), “If a plaintiff can show that modification of

the decree is crucial to the effectuation of the purpose the

decree was intended to achieve, then a grievous wrong would

be perpetrated if the decree was not modified.”

United States v. Armour & Co., 402 U.S. 673 (1971), relied

upon by Petitioners, does not disturb these principles. In

Armour, the Court held that construction of a consent decree

must be conducted within the “four corners” of the decree.

The opinion, however, did not purport to alter the standards

applicable to requests for modification of a decree; to the

contrary, the Court suggested that “if the Government believed

that changed conditions warranted further relief [beyond that

provided for in the original consent decree], it could have

sought modification of the [decree] itself.” Id. at 674-75 (citing

Chrysler Corporation v. United States, supra). In addition, the

Court observed that there “might be a persuasive argument for

modifying the original decree, after full litigation, on a claim

that unforeseen circumstances now made additional relief de

3 Citing United States v. Swift & Co., 286 U.S. 106, 115 (1932), the

Firefighters Union suggests that modification of the 1980 Decree cannot be

upheld unless changed circumstances have transformed the original decree

into an “instrument of wrong.” The Swift Court’s insistence on a “clear

showing of grievous wrong,” 286 U.S. at 119, however, applies only to

applications by parties seeking to reduce their obligations under a consent

decree, not to requests for modification by the beneficiary of the decree’s

remedial program. United States v. United Shoe Machinery Corp., 391 U.S.

244, 248-49 (1968). It is not the consent decree that constitutes the “wrong”

for the beneficiary of the relief therein, but the prior practices that led to the

injunctive provisions of the decree. When, in light of changed circumstances,

the decree no longer effectively prevents the harm against which it was

intended to guard, the question relevant to an application for modification is

that identified in Chrysler, whether the proposed modification is needed to

effectuate the goals embodied in the decree. See United Shoe, 391 U.S. at

249-51.

7

sirable to prevent the evils aimed at by the original complaint.”

402 at U.S. at 681. More recently, this Court has reiterated that

a party may petition for modification of a consent decree if it

believes that changed circumstances warrant further relief. See

United States v. IT T Continental Baking Co., 420 U.S. 223,

233 n.8 (1975). See also Environmental Defense Fund, Inc. v.

Castle, 636 F.2d 1229, 1240 (D.C. Cir. 1980) (“sound exercise

of judicial discretion may require that terms of a consent

decree be modified when there has been a significant change in

the circumstances obtaining at the time the consent decree was

entered”); Luevano v. Campbell, 93 F.R.D. 68, 92-93 (D.D.C.

1981) (court has power “to modify the obligations of the

Consent Decree in order to further its purposes in light of

unforeseen problems which may arise”).

In the present case, it is plain that, to the extent (if any) that

it modified the 1980 Decree, the District Court’s preliminary

injunction “served to effectuate” rather than “thwart” the

objects of the original decree.

The “evil aimed at” in this Title VII action was the exclusion

of blacks from all levels of the Memphis Fire Department. The

1980 Decree strikes at this evil by requiring progress in the

hiring and promotion of blacks until their representation in the

Memphis Fire Department approximates their representation

in the civilian work force. By accepting the 1980 Decree,

moreover, the plaintiffs agreed to forego pursuit of other

relief, e.g., back pay (beyond a $60,000 award provided in the

settlement) and full retroactive seniority. The lay-offs proposed

by the City would have effectively deprived plaintiffs of the

benefit of their bargain in agreeing to the consent decree. See,

e.g., Kirke la Shelle Co. v. Armstrong, 263 N.Y. 79, 87, 188

N.E. 163, 167 (1933) (every contract contains “an implied

covenant that neither party shall do anyting which will have the

effect of destroying or injuring the right of the other party to

receive the fruits of the contract”); Burton, Breach o f Contract

and the Duty to Perform in Good Faith, 94 Harv. L. Rev. 369

(1980).

The goal of proportional representation had been achieved

to only a limited degree when the City announced its intention

to lay-off members of the Department. All parties agree that

the proposed lay-offs would have disproportionately affected

black fire fighters and officers; progress in minority hiring and

promotion would largely have been undone. Disproportionate

numbers of blacks in supervisory positions such as lieutenant

would have been reduced in rank, thereby negating the ad

vances made in minority promotions under the 1980 Decree.4

In addition, disproportionate numbers of blacks at the lowest

rank would have been laid off, thereby diminishing overall

black representation in the Department. As the Court of

Appeals noted, “[T]he application of the lay-off policy to the

job classifications selected by the City would have virtually

destroyed the progress belatedly achieved through affirmative

action. The City contracted in 1974 and 1980 to accomplish

precisely that which the lay-offs would destroy: a substantial

increase in the number of minorities in supervisory positions.”

679 F.2d at 561. Had the City been allowed to proceed, the

plaintiffs would have been deprived of the very remedy in

exchange for which they gave up their right to pursue remedies

of back pay and full retroactive seniority. See Burton, supra,

94 Harv. L. Rev. at 387.

Because the proposed lay-offs would have vitiated the in

tended effects of the 1980 Decree, the District Court, under the

authorities cited above, properly exercised its equitable discre

tion to halt the proposed City action. The Court’s preliminary

injunction is carefully limited to avoid interference with the

operation of the Memphis Fire Department and to minimize

any infringement of the interests of other employees.5 It does

no more than prevent the City from reducing the percentage of

4 The City acknowledges that, of 36 proposed demotions, 26 would

have affected blacks. This disparity was most pronounced at the lieutenant

rank, where 16 of 29 black lieutenants (55%) would have been demoted to

driver or private, while only 1 of 211 white lieutenants (0.5%) would have

been so affected. See Brief for Petitioners Memphis Fire Department et al. at

7 n .l l .

5 Compared with the range of possiblities available to the District

Court, the relief ordered was strikingly modest. The Court, for example, did

not direct that the City, during its fiscal crisis, make continued progress

9

minorities in each job classification. While furthering the

objectives of the 1980 Decree, the relief carefully accommo

dates the interests of all employees affected by the preliminary

injunction. The District Court engaged in a sound exercise, not

an abuse, of its equitable discretion.

The decisions in other employment discrimination cases

further confirm the propriety of the District Court’s action.

Courts confronted with facts virtually identical to those pre

sented here have modified consent decrees without hesitation

to prevent eradication of gains in minority employment. See

Boston Chapter, NAACP v. Beecher, 679 F.2d 965 (1st Cir.

1982), vacated and remanded fo r a determination o f mootness,

103 S.Ct. 2076 (1983); Brown v. Neeb, 644 F.2d 551 (6th Cir.

1981) (consent decree pursuant to 42 U.S.C. §§ 1981, 1983).

Petitioners and various amici suggest that the District

Court’s action will deter settlement of other Title VII cases,

since parties will be reluctant to agree to consent decrees that

might be revised at some point in the future in light of

unforeseen circumstances. This line of reasoning is unper

suasive.

As the precedents cited above establish, a court has power to

modify a consent decree only in a manner that will advance the

goals originally agreed to by the parties and comprehended by

the decree. Modification in accordance with this standard does

not disrupt the legitimate expectations of the parties; it merely

ensures that unforeseen circumstances will not defeat a reme

dial program whose success was anticipated by both parties to

the decree. This long-established equitable power must be

regarded as a part of the informed expectations of litigating

parties and their attorneys. Because affirmance of the decision

below would represent no augmentation of the equitable power

of a district court, there is no basis for apprehension that the

prospects for settlement of other cases will be impaired.

toward the goals set forth in the 1980 Decree. The preliminary injunction

actually imposed no additional burdens on the City, since it did not compel

the City to retain more members of the Fire Department than the City

determined to be appropriate. The relief instead was a temporary, limited

measure directed exclusively to preservation of the limited progress already

achieved under the 1980 Decree.

10

II. TITLE VII MANDATES THE RELIEF AWARDED IN

THE PRELIMINARY INJUNCTION

Petitioners and several amici also maintain that the prelimi

nary injunction contravenes the provisions of Title VII. They

argue that the relevant remedial provision of Title VII, Section

706(g), 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(g), prohibits the granting of any

relief to persons who have not been adjudicated victims of

discrimination prohibited by Title VII. They also argue that,

even if Section 706(g) permits the award of certain types of

relief to persons not adjudicated victims of discrimination, the

preliminary injunction impermissibly granted a form of retro

active seniority which is limited to adjudicated victims of

discrimination. These arguments find no support in the lan

guage or purpose of Title VII, and the relevant decisions of

this Court argue strongly to the contrary.

A. Section 706(g) of Title VII Does Not Limit Relief to

Adjudicated Victims of Discrimination

In enacting Title VII, “ Congress took care to arm the courts

with full equitable powers. For it is the historic purpose of

equity to ‘securje] complete justice.’ ” Albemarle Paper Co. v.

Moody, 422 U.S. 405, 418 (1975) (“Moody”) (quoting Brown

v. Swann, 35 U.S. (10 Pet.) 497, 503 (1836)). Congress in

tended that, through the exercise of this plenary authority, the

courts would “ fashion the most complete relief possible.’’ 422

U.S. at 421 (quoting 118 Cong. Rec. 7168 (1972) (remarks of

Sen. Williams)).

These broad equitable powers are granted by Section 706(g)

of Title VII, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(g). Section 706(g) explicitly

empowers the district courts to “ order such affirmative action

as may be appropriate.” Affirmative action remedies have

frequently included hiring and promotion goals for minority

employees (such as those contained in the 1974 and 1980

Decrees), see, e.g., Chisolm v. United States Postal Service,

665 F.2d 482 (4th Cir. 1981); United States v. City o f Alexan

dria, 614 F.2d 1014 (5th Cir. 1980); Prate v. Freedman, 583

F.2d 42 (2d Cir. 1978), as well as awards of retroactive

11

seniority to prevailing class members, see, e.g., International

Brotherhood o f Teamsters v. United States, 431 U.S. 324

(1977) (“ Teamsters” ); Franks v. Bowman Transportation Co.,

424 U.S. 747 (1976) (“Franks”).

In fashioning the complete remedy required by Section

706(g), the district court must fulfill two objectives of Title

VII. First, as Petitioners and the Department of Justice em

phasize, the court must provide complete “ make-whole” re

lief, so that identifiable victims of discrimination will be placed

in the economic position they would have enjoyed in the

absence of discrimination by the employer. See, e.g., Franks,

424 U.S. at 763; Moody, 422 U.S. at 418-19.

“ Make-whole” relief, however, does not exhaust the reach

of Title VII. There is a second goal. “ [A] primary objective of

Title VII is prophylactic: to achieve equal employment oppor

tunity and to remove the barriers that have operated to favor

white male employees over other employees.” Teamsters, 431

U.S. at 364. Thus, the court has “ not merely the power but the

duty to render a decree which will so far as possible eliminate

the discriminatory effects of the past as well as bar like

discrimination in the future.” Teamsters, 431 U.S. at 364

(quoting Moody, 422 U.S. at 418).6

Because eliminating the present effects of past discrimina

tion is no less important an objective under Title VII than the

providing sufficient “ make-whole” relief, remedies under Sec

tion 706(g) have never been limited to adjudicated victims of

the employer’s discrimination. The twelve circuits are unani

mous in upholding hiring and promotion goals not limited to

adjudicated victims of discrimination, explicitly or implicitly

because such remedies are necessary to eliminate the present

effects of past discrimination.7 As Judge Charles Clark ex

plained in NAACP v. Allen, 493 F.2d 614, 621 (5th Cir. 1974):

6 See Berkman v. City o f New York, 705 F.2d 584, 596 (2d Cir. 1983)

(“ Affirmative relief is that designed principally to remedy the effects of

discrimination that may not be cured by the granting of compliance or

compensatory relief.” ).

7 See, e.g., McKenzie v. Sawyer, 684 F.2d 62 (D.C. Cir. 1982); Boston

Chapter, N .A.A.C .P., Inc. v. Beecher, 504 F.2d 1017 (1st Cir. 1974), cert.

12

The use of quota relief in employment discrimination

cases is bottomed on the chancellor’s duty to eradicate the

continuing effects of past unlawful practices. By mandat

ing the hiring of those who have been the object of

discrimination, quota relief promptly operates to change

the outward and visible signs of yesterday’s racial distinc

tions and thus, to provide an impetus to the process of

dismantling the barriers, psychological or otherwise,

erected by past practices. It is a temporary remedy that

seeks to spend itself as promptly as it can by creating a

climate in which objective, neutral employment criteria

can successfully operate to select public employees solely

on the basis of job-related merit.

Limiting relief under Section 706(g) to adjudicated victims

of proven discrimination could only obstruct enforcement of

Title VII. If an adjudication were required, it would be

impossible to award class-wide relief under a consent decree;

each plaintiff who seeks such relief would be forced to go to

trial, despite the efforts by Congress and the Court to foster

settlement of Title VII claims. See, e.g., Carson v. American

Brands, Inc., 450 U.S. 79, 88 n.14 (1981); Alexander v.

Gardner-Denver Co., 415 U.S. 36, 44 (1974). Even if an

increase in the number of Title VII trials were desirable, the

ability of the district courts to desegregate previously all-white

work forces would depend on the fortuitous availability of all

denied, 421 U.S. 910 (1975); Prate v. Freedman, 583 F.2d 42 (2d Cir. 1978);

EEOC v. American Telephone and Telegraph Co., 556 F.2d 167 (3d Cir.

1977), cert, denied, 438 U.S. 915 (1978); Chisholm v. United States Postal

Service, 665 F.2d 482 (4th Cir. 1981); United States v. City o f Alexandria,

614 F.2d 1358 (5th Cir. 1981); Bratton v. City o f Detroit, 704 F.2d 878 (6th

Cir.), modified, 712 F.2d 222 (6th Cir. 1983); United States v. City o f

Chicago, 549 F.2d 415 (7th Cir. 1977); Carter v. Gallagher, 452 F.2d 315 (8th

Cir.) (en banc), cert, denied, 406 U.S. 950 (1972); Davis v. County o f Los

Angeles, 566 F.2d 1334 (9th Cir. 1977), vacated as moot, 440 U.S. 625

(1979); United States v. Lee Way Motor Freight, Inc., 625 F.2d 918 (10th

Cir. 1979). Under Bonner v. City o f Pritchard, 661 F.2d 1206 (11th Cir.

1981) (en banc), panels of the Eleventh Circuit remain bound by Fifth Circuit

decisions rendered prior to October 1, 1981, such as United States v. City o f

Alexandria, supra.

13

persons who were victims of the employer’s discriminatory

practices. As the Third Circuit has observed, all of the victims

of an employer’s illegal practices are unlikely to be available;

race-conscious remedies are therefore necessary “ to counteract

the effects of discriminatory practices upon the balance of sex

and racial groups that would otherwise have obtained.” EEOC

v. American Telephone & Telegraph Co., 556 F.2d 167, 180

(3d Cir. 1977), cert, denied, 438 U.S. 915 (1978) (“AT& T”);

accord, Baker v. City o f Detroit, 483 F. Supp. 930, 993-94

(E.D. Mich. 1979), a ff’d sub nom. Bratton v. City o f Detroit,

704 F.2d 878 (6th Cir.), modified, 712 F.2d 222 (6th Cir.

1983).

Both the 1980 Decree and the preliminary injunction at issue

here fulfill these important objectives of Title VII. The Sixth

Circuit held that the race-conscious employment goals in the

decree were a reasonable means of ameliorating the present

effects of past discrimination and of desegregating the Fire

Department. 679 F.2d at 553-56. The preliminary injunction,

by preserving for the successful class members the benefits of

the consent decree until there is a hearing on the merits,

equally serves those goals.8

Even though the 1980 Decree and the preliminary injunction

are plainly the type of “affirmative action” mandated by

Section 706(g), the Justice Department implausibly interprets

the final sentence of Section 706(g) to prohibit an award of

relief to any except proven victims of discrimination. This

sentence provides that:

No order of the court shall require the admission or

reinstatement of an individual as a member of a union, or

the hiring, reinstatement, or promotion of an individual

as an employee, or the payment to him of any back pay, i f

such individual was refused admission, suspended, or

expelled, or was refused employment or advancement or

8 Of course, to the extent that beneficiaries of the 1980 Decree and the

preliminary injunction were victims of discrimination by the Fire Depart

ment, the relief serves the “make-whole” objective of Title VII as well.

14

was suspended or discharged for any reason other than

discrimination on account of race, color, religion, sex, or

national origin or in violation of section 2000e-3(a) of this

title.

(Emphasis added.)

By its terms, this sentence does not apply to the relief

ordered in the preliminary injunction. In exempting some

members of the prevailing class from lay-offs, the preliminary

injunction does not order “the hiring, reinstatement, or pro

motion” of any person. However, even if this sentence did

apply to the preliminary injunction, it would not prohibit the

relief ordered by the District Court.

No court has ever adopted the Justice Department’s novel

interpretation of Section 706(g), and this reading was explicitly

rejected by the Third Circuit in AT&T. The statute prohibits

the courts only from ordering the hiring, reinstatement, or

promotion of an individual “if such individual was refused

. . . employment or advancement or was suspended or dis

charged for any reason other than discrimination on account

or race, color, religion, sex, or national origin . . . .” This

language applies only to those persons who previously sought

employment or promotion but had been rejected by the em

ployer for nondiscriminatory reasons (e.g., because they were

unqualified); it makes no reference to persons who had not

sought employment or promotion and thus does not prohibit

their hiring under a remedial affirmative action plan.

Instead, the quoted language reflects Congress’s intent that

persons who had been refused employment or promotion (or

who had been fired) for legitimate, nondiscriminatory reasons

could not invoke the strong remedial provisions of Section

706(g) to obtain employment or promotion. AT&T, 556 F.2d at

176; 110 Cong. Rec. 2567 (1964) (remarks of Rep. Celler in

introducing this language); Vaas, Title VII: Legislative History,

7 B.C. Ind. & Com. L. Rev. 431, 438 (1966). In enacting Title

VII, Congress did not intend to authorize hiring of unqualified

employees. See Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424, 436

(1971). The 1980 Decree approved by the panel more than

15

complies with this limitation under Section 706(g) because it

permits the City to deny employment to any person who is not

qualified for the position. See United States v. City o f Alexan

dria, 614 F.2d 1358, 1366 (5th Cir. 1980); AT&T, 556 F.2d at

176.

In AT&T, the Third Circuit, after thoroughly canvassing the

relevant legislative history, concluded that the interpretation

now advocated by the Justice Department distorted congres

sional intent. 556 F.2d at 175-77. As the AT&T court noted, the

section-by-section analysis in the 1964 House Report inter

preted the initial House version of Section 706(g), H.R. 7152,

88th Cong., 1st Sess. § 707(e) (1963), as follows:

No order o f the court may require the admission or

reinstatement of an individual as a member of the union

or the hiring, reinstatement, or promotion o f an individ

ual as an employee or payment of any back pay i f the

individual was refused admission, suspended, or sepa

rated, or was refused employment or advancement, or

was suspended or discharged fo r cause.

H.R. Rep. No. 914, 88th Cong., 1st Sess. (1963) (emphasis

added). Like the final language of Section 706(g), this passage

reflects only congressional concern that employers not be

compelled to hire specific individuals who were unqualified or

who were denied employment or promotion for nondiscrimina-

tory reasons.

On the House floor, the proposed section was amended. The

grounds on which an employer could refuse to hire or promote

“such individual” claiming discrimination were expanded by

substituting for the word “cause” the present language, “for

any reason other than discrimination on account of race, color,

religion, or national origin.” See 110 Cong. Rec. 2567 (1964).

The substitution of this language was designed to prevent

plaintiffs pressing spurious claims of discrimination from argu

ing that an employer’s legitimate reason for denying employ

ment or promotion did not qualify as “cause”. Representative

Celler’s explanation in introducing the amendment is authori

tative:

16

Mr. Chairman, the purpose of the amendment is to

specify cause. Here the court, for example, cannot find

any violation of the act which is based on facts other—

and I emphasize “other”—than discrimination on the

grounds of race, color, religion, or national origin. The

discharge might be based, for example, on incompetence

or a morals charge or theft, but the court can only

consider charges based on race, color, religion, or na

tional origin. That is the purpose of this amendment.

110 Cong. Rec. 2567 (1964) (remarks of Rep. Celler). The

concluding language of Section 706(g) is therefore concerned

exclusively with defining a “violation of the act,” id., not with

limiting the broad equitable powers granted by Title VII.

The progress of Section 706(g) in the Senate similarly af

fords no basis for distorting its language to prohibit race-con

scious affirmative remedies. The interpretive memorandum

offered by Senators Clark and Case stated, in a passage relied

upon by Petitioners and their amici, that:

No court order can require hiring, reinstatement, admis

sion to membership, or payment of back pay for anyone

who was not discriminated against in violation of this

title. This is stated expressly in the last sentence of section

707(e) [now Section 706(g)] which makes clear what is

implicit throughout the whole title; that employers may

hire and fire, promote and refuse to promote for any

reason, good or bad, provided only that individuals may

not be discriminated against because of race, color, reli

gion, sex, or national origin.

110 Cong. Rec. 7214 (1964). The passage demonstrates only

the Senators’ concern that employers be able to refuse employ

ment or promotion to those employees considered unfit for the

position without fear that their judgment would be overruled

by the provisions of Title VII. It does not address (much less

prohibit) the availability of affirmative remedies not restricted

to individuals who have proven that they were victims of the

employer’s practices. Far more relevant is the statement of

17

Senator Humphrey, a sponsor of Title VII, that the statute was

intended to “open employment opportunities for Negroes in

occupations which have been traditionally closed to them.”9

110 Cong. Rec. 6548 (1964) (remarks of Sen. Humphrey).

The legislative history of the Equal Employment Opportu

nity Act of 1972, Pub. L. 92-261, 92d Cong., 2d Sess., 86 Stat.

103 (1972), codified (as amended) at 42 U.S.C. § 2Q0Qe et seq.,

further demonstrates that Title VII remedies are not limited to

adjudicated victims of discrimination. The section-by-section

analysis of that Act provided by Senators Javits and Williams

states that:

In any area where the new law does not address itself, or

in any areas where a specific contrary intention is not

indicated, it was assumed that the present case law as

developed by the courts would continue to govern the

applicability and construction of Title VII.

118 Cong. Rec. 3460 (1972).

Congress was unquestionably aware of decisions ordering

race-conscious affirmative action remedies. During the debates

on the 1972 Act in the Senate, Senator Javits specifically

defended the affirmative action remedy ordered in United

States v. Ironworkers, Local 86, 443 F.2d 544 (9th Cir.), cert,

denied, 404 U.S. 984 (1971), and inserted a copy of the court’s

opinion in the Congressional Record. 118 Cong. Rec. 1671-75

(1972).10

Thus, the language and legislative history of Section 706(g)

leave no doubt of the propriety of race-conscious relief that

may benefit persons never adjudicated to have been victims of

discrimination.

9 In United Steelworkers o f America v. Weber, 443 U.S. 193 (1979),

the Court relied on this language in upholding a private employer’s race-con

scious affirmative action plan.

10 In Ironworkers, the Ninth Circuit ordered the union to apprentice

“sufficient black applicants to overcome past discrimination” without regard

to whether an applicant was a proven victim of discrimination. See 443 F.2d

at 553.

18

B. The Relief Granted in the Preliminary Injunction Did Not

Impermissibly Interfere with the Operation of a Seniority

System

Petitioners and their amici apparently believe that, even if

certain forms of race-conscious relief were authorized under

Section 706(g), any race-conscious remedy that intrudes (even

minimally) on the seniority expectations of employees outside

the plaintiff class can never be granted. The language of

Section 706(g), however, contains no such limitation. In fact,

the decisions of this Court support the award of relief far more

intrusive than the remedy provided in the preliminary injunc

tion if, as here, a valid remedial purpose is served.11

The District Court’s prohibition of reductions in the percent

age of black employees in specified ranks within the Fire

Department was designed solely to preserve the partial attain

ment of the objectives set forth in the initial version of the

1980 Decree. By shielding certain class members from the

operation of the City’s lay-off plan, the District Court tem

porarily protected them from a rigorous application of last-

hired-first-laid-off seniority principles. That protection was

limited in time to the 1981 Memphis fiscal crisis and directed

exclusively to protecting job tenure. Unlike recipients of per

manent retroactive seniority in Title VII cases, these class

members did not receive increased pension rights or time

credited towards promotion. This Court’s decisions in Franks

11 The discussion in text assumes arguendo that the City maintained a

bona fide seniority system as that term is used in Section 703(h) of Title VII,

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(h). Absent a bona fide seniority system, the considera

tions set forth in Teamsters concerning the protection of such systems do not

apply. It is by no means clear whether or not the City’s lay-off plan, whose

terms differ from those of its previous, non-binding (see City o f Alcoa v.

International Brotherhood o f Electrical Workers Local 760, 203 Tenn. 12,

308 S.W.2d 476 (1958)) Memorandum of Understanding with the Union, is a

bona fide seniority system. Were decision of this factual issue determinative,

its resolution should be made first at the trial court level. Resolution of this

issue is unnecessary, however, because Respondents would prevail even if the

lay-off plan did constitute a bona fide seniority system.

19

and Teamsters, endorsing the wide availability of permanent

retroactive seniority, support both the purpose and scope of the

more limited relief granted by the District Court in the prelimi

nary injunction.

In both Franks and Teamsters, defendant employers chal

lenged the availability of an award of class-wide permanent

retroactive seniority to successful Title VII plaintiffs. In

Franks, the Court established a general presumption in favor

of granting full retroactive seniority to victims of an em

ployer’s discrimination.12 The Court did not relegate perma

nent retroactive seniority to the status of rare or extraordinary

relief, but instead held that it should ordinarily be awarded

unless there was an “unusual adverse impact arising from facts

and circumstances that would not be generally found in Title

VII cases.” 424 U.S. at 779 n.41. While stressing that the

design of the appropriate remedy is left to the sound equitable

discretion of the district court, the Court admonished that the

district court’s discretion must be exercised to “allow the most

complete achievement of the objectives of Title VII that is

attainable under the facts and circumstances of the specific

case.” Id. at 770-71. Franks was primarily concerned with

retroactive seniority as a restitutionary “make-whole” remedy.

It nowhere limits retroactive seniority to serving exclusively

that objective of Title VII, and speaks instead of the “objec

tives” of the statute.

In Teamsters, the Court explicitly validated the employer’s

seniority system as bona fide, yet reiterated that successful

class members were presumptively entitled to permanent retro

active seniority. 431 U.S. at 347. While retroactive seniority in

Teamsters was sought and granted solely as a matter of

12 The Court in Franks rejected the contention that Section 703(h) of

Title VII, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(h), prevents the district court from awarding

retroactive seniority. Section 703(h) states that the maintenance of a bona

fide (i.e., nondiscriminatory) seniority system does not constitute actionable

discrimination. As this Court explained, Section 703(h) merely defines legal

and illegal practices under Title VII; it does not impose a limitation on the

district court’s remedial authority under Title VII. See 424 U.S. at 757-62.

20

“make-whole” relief, the Court emphasized the importance of

other remedial objectives of Title VII, stating (in language we

have previously quoted) that “the district courts have ‘not

merely the power but the duty to render a decree which will so

far as possible eliminate the discriminatory effects of the past

as well as bar like discrimination in the future.’ ” Id. at 364

(quoting Moody, 422 U.S. at 418).

Given (1) the strong presumption in favor of awarding

permanent retroactive seniority, (2) the District Court’s “duty”

to eliminate the present effects of past discrimination, and (3)

the deference paid to the court’s sound equitable discretion,

the preliminary injunction here, which at most temporarily and

partially suspended the operation of a seniority program, is not

objectionable. The remedial purpose of the 1980 Decree, the

elimination of the present effects of past discrimination, was

specifically endorsed in Franks and Teamsters. Those decisions

in no way diminish the power and obligation of the District

Court to safeguard the efficacy of the relief that it ordered. On

the contrary, those decisions approve active pursuit of the

prophylactic goals of Title VII, even where, as here, this

pursuit may partially disrupt expectations based on seniority.

As the First Circuit noted in Boston Chapter, NAACP v.

Beecher, 679 F.2d 965, 975 (1st Cir. 1982), vacated and re

manded fo r a determination o f mootness, 103 S.Ct. 2076

(1983), on facts virtually identical to those presented here, “To

hold a seniority system inviolate in such circumstances would

make a mockery of the equitable relief already granted.”

Both Franks and Teamsters recognize that relief in Title VII

cases, including class-wide permanent retroactive seniority,

often affects the interests of non-minority employees. See

Franks, 424 U.S. at 774-79; Teamsters, 431 U.S. at 374-76. Yet,

as the Court noted in Franks,

If relief under Title VII can be denied merely because the

majority group of employees, who have not suffered

discrimination, will be unhappy about it, there will be

little hope of correcting the wrongs to which the Act is

directed.

21

424 U.S. at 775 (quoting United States v. Bethlehem Steel

Corp., 446 F.2d 652, 663 (2d Cir. 1971)). In Teamsters, this

Court stated that it is the responsibility of the trial court to

resolve the competing interests. See 431 U.S. at 375-76. The

very limited and necessary relief contained in the preliminary

injunction entails far less intrusion on the interests of non

minority employees than did the award of permanent retro

active seniority authorized in Franks and Teamsters. The

District Court sensitively accommodated the interests and ex

pectations of both class members and nonminority employees

in fashioning a decree that does no more than safeguard, for

the limited duration of the 1981 layoffs, the progress in

affirmative action that had already been made.

Petitioners and their amici argue that, because there was no

finding of discrimination by the City and no adjudication that

each class member protected from lay-offs was a proven victim

of discrimination, the District Court lacked equitable discre

tion to issue a preliminary injunction affecting seniority expec

tations. These arguments treat the 1980 Decree as a procedural

nullity without consequences for the defendants.

A consent decree is a court order embodying an agreement

by the defendant to provide the plaintiff class with specified

relief. See United States v. City o f Miami, 664 F.2d 435, 439-40

(5th Cir. 1981) (en banc) (plurality opinion). By agreeing to the

1980 Decree, the City waived its right to insist that the plaintiff

class prove the City’s commission of discriminatory practices,

just as the plaintiff class waived its right to seek greater relief

(e.g., full retroactive seniority) from the court. The City, in an

effort to defeat the District Court’s injunction preserving the

remedy agreed upon in 1980, cannot now rely on the absence

of a finding which it, by its consent, made unnecessary.13 A

13 However, the District Court could not have approved the 1980

Decree unless it found that the the decree was fair and equitable in light of

the plaintiff’s showing of a potential violation. Here, both the District Court

and, on appeal, the Sixth Circuit carefully reviewed the 1980 Decree and

found it fair and equitable. In granting the preliminary injunction, the

District Court explicitly took judicial notice (on the basis of both facts in the

record and common public knowledge) that the City was guilty of racial

discrimination. (Petitions for Cert., App. at 73-74).

22

contrary rule would render courts of equity powerless to

protect the efficacy of relief ordered by consent and would

subject litigants to the protracted litigation that the consent

decree was designed to avoid.

The Petitioners also mistakenly insist that the District Court

could not issue the preliminary injunction without first deter

mining that each recipient was a victim of the City’s dis

criminatory practices. When full retroactive seniority is sought

solely as restitutionary “make-whole” relief, Franks and Team

sters understandably limit such relief to identifiable victims of

the employer’s practices. (A non-victim neither seeks nor needs

restitution.)

In this case, however, the relief granted was not sought as

“make-whole” relief. It was awarded pursuant to the District

Court’s mandate under Section 706(g) to order appropriate

affirmative action and pursuant to its power as a court of

equity to preserve the integrity of its decrees. Thus, affirmative

action was necessary to protect the remedy (albeit partial)

achieved under an earlier uncontested decree designed to elimi

nate the enduring effects of historic discrimination. Franks and

Teamsters hold that, if a class-wide award of permanent

retroactive seniority is necessary to achieve the objectives of

Title VII, it should be granted notwithstanding its effect on the

seniority expectations of employees outside the class. These

cases do not hold that retroactive seniority can never be

granted to individuals not adjudicated victims of the em

ployer’s discrimination. Instead, they commit the scope of

relief to the sound discretion of the district court. Given the

presumption established by these cases in favor of granting a

form of seniority relief far more intrusive than that at issue

here, the District Court should not be found to have abused its

discretion. After considering the equities, the court acted well

within its discretion in approving a remedy that has only a

limited and temporary effect on seniority while achieving the

unexceptionable purpose of effectuating the court’s prior de

cree.

The requirement of an adjudication that each beneficiary

was a victim of discrimination, like the requirement of an

23

adjudication that the defendant had engaged in discriminatory

practices, would effectively prevent courts of equity from

moving swiftly to preserve the results that have already been

achieved under a Title VII consent decree. Such adjudications

would be especially inappropriate in the context of a prelimi

nary injuction, which seeks only to protect the status quo,

prior to a decision by the District Court on the merits.

Even assuming that such individual adjudications were

appropriate, this Court held in both Franks and Teamsters that

such adjudications are not a prerequisite to an initial class-wide

award of retroactive seniority. In Franks, this Court ruled that

class-wide permanent retroactive seniority should be awarded

by the district court subject to the employer’s right, at subse

quent proceedings, to object to the award of retroactive senior

ity to specific employees on an individual basis. Franks, 424

U.S. at 772-73. As an indication of the importance given to

providing complete relief, the Court placed the burden of

proof in such individual proceedings on the employer. Id. at

773 n.32. In Teamsters, the Court restated these propositions.

431 U.S. at 359 & n.45.14 Accordingly, individual adjudica

tions, even where appropriate, should occur only following the

entry of class-wide retroactive seniority after a hearing on the

merits, and a fortiori were not required before the entry of the

much more modest relief at issue here. The absence of such

adjudications prior to issuance of the preliminary injunction

affords no basis for disturbing the District Court’s ruling.

14 In Teamsters, the court isolated a single discrete group of plaintiffs,

those who had never applied for the position of over-the-road driver, and

held that, before they enjoyed the presumption in favor of full retroactive

seniority, they first bore the burden of establishing that they would have

applied for the position but for the employer’s discrimination. See 431 U.S.

at 367-68. There is no indication that such a discrete group exists here,

because all employees benefiting from the preliminary injunction were hired

prior to the entry of the consent decree in 1980, see Brief for Petitioner

Memphis Fire Department, Add. A. The less intrustive form of relief granted

in the preliminary injunction cannot justify such segmentation in any event.

24

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, MALDEF respectfully requests

that this Court affirm the decision of the United States Court

of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit.

Respectfully submitted,

Robert L. King

(Counsel of Record)

Mary Jo White

Kenneth E. Wile

George T. Spera, Jr.

Debevoise & Plimpton

875 Third Avenue

New York, New York 10022

(212) 909-6000

Attorneys fo r Amicus Curiae

The Mexican American

Legal Defense and

Educational Fund

O f Counsel:

Joaquin G. Avila

Morris J. Bailer

The Mexican American

Legal Defense and

Educational Fund

28 Geary Street

San Francisco, California 94108

October 27, 1983

RECORD PRESS, INC., 157 Chambers St., N.Y. 10007 (212) 243-5775