King v. Palmer Brief Amici Curiae

Public Court Documents

November 13, 1990

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. King v. Palmer Brief Amici Curiae, 1990. e7c28e0b-ba9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/bfaead50-fe09-4e05-bd86-b856d1a5b0fa/king-v-palmer-brief-amici-curiae. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

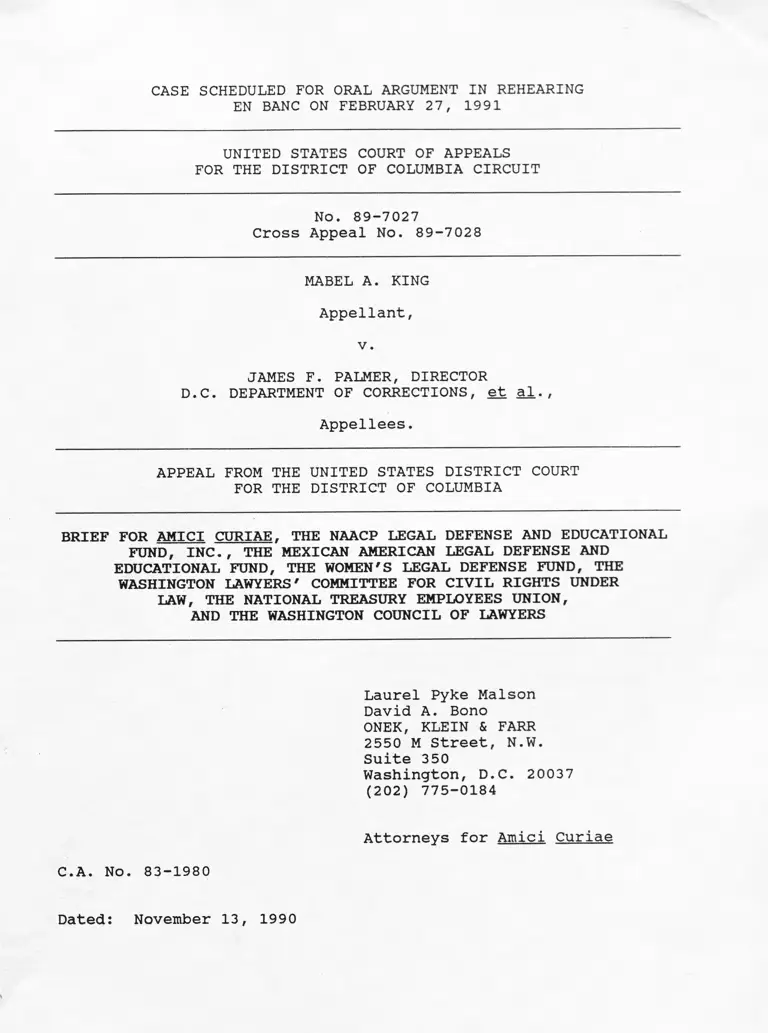

CASE SCHEDULED FOR ORAL ARGUMENT IN REHEARING

EN BANC ON FEBRUARY 27, 1991

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT

No. 89-7027

Cross Appeal No. 89-7028

MABEL A. KING

Appellant,

v .

JAMES F. PALMER, DIRECTOR

D.C. DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTIONS, et al.,

Appellees.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA

BRIEF FOR AMICI CURIAE. THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL

FUND, INC., THE MEXICAN AMERICAN LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATIONAL FUND, THE WOMEN'S LEGAL DEFENSE FUND, THE

WASHINGTON LAWYERS' COMMITTEE FOR CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER

LAW, THE NATIONAL TREASURY EMPLOYEES UNION,

AND THE WASHINGTON COUNCIL OF LAWYERS

Laurel Pyke Malson

David A. Bono

ONEK, KLEIN & FARR

2550 M Street, N.W.

Suite 350

Washington, D.C. 20037

(202) 775-0184

Attorneys for Amici Curiae

C.A. No. 83-1980

Dated: November 13, 1990

ADDITIONAL COUNSEL

Julius LaVonne Chambers

Charles Stephen Ralston

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE

AND EDUCATIONAL FUND

99 Hudson Street

Suite 1600

New York, NY 10013

E. Richard Larson

MEXICAN AMERICAN LEGAL DEFENSE

AND EDUCATIONAL FUND

634 South Spring Street

11th Floor

Los Angeles, CA 90014

Joseph M. Sellers

WASHINGTON LAWYERS' COMMITTEE

FOR CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER LAW

1400 I Street, N.W.

Suite 450

Washington, D.C. 20005

Donna Lenthoff

WOMEN'S LEGAL DEFENSE FUND

2000 P Street, N.W. Fund

Suite 400

Washington, D.C. 20036

Gregory O'Duden

Elaine Kaplan

Timothy Hannapel

NATIONAL TREASURY EMPLOYEES UNION

1730 K Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20006

Paul M. Smith

WASHINGTON COUNCIL OF LAWYERS

1200 New Hampshire Avenue, N.W.

Suite 700

Washington, D.C. 20036

CERTIFICATE OF COUNSEL REQUIRED BY RULE 11(e)(5)

Counsel hereby certifies that this separate brief amicus

curiae is necessary to present and elaborate on arguments

concerning the necessity of risk enhanced fee awards under §

706(k) of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, as amended,

and similar fee-shifting statutes. Counsel further certifies

that, because the interests of these amici differ from those of

other amici, who focus on separate issues, all amici have not

been able to join in a single brief.

RULE 11(a)(1) CERTIFICATE AS TO PARTIES, RULINGS,

AND RELATED CASES

(A) Parties and amici

Appellant and plaintiff below is Mabel A. King.

Appellees and defendants below are James F. Palmer, Director of

the District of Columbia Department of Corrections, and the

District of Columbia. The following parties have moved to be

recognized as amici in this Court: the NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc., the Mexican American Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, the Women's Legal Defense Fund, the Washington

Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights Under Law, the National

Treasury Employee's Union, the Washington Council of Lawyers, the

American Bar Association, Joel P. Bennett, Lynne Bernabei, John

M. Dorsen, Daniel B. Edelman, Bruce A. Fredrickson, Kator, Scott

& Heller, Jane Lang, Elliott C. Lichtman, Squire Padgett, Inez

Reid, Larry Sherman, Gary Simpson, and Robert M. Weinberg.

(B) Rulings under review

The rulings under review are listed in the Brief for the

Appellant.

(C) Related cases

Related cases are listed in the Brief for the Appellant.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES........................................... ii

INTEREST OF AMICI................................................ 1

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT................ 5

ARGUMENT......................................................... 6

I. CONTINGENCY ENHANCEMENTS ARE NECESSARY TO EFFECTUATE

THE PURPOSES OF FEE-SHIFTING UNDER TITLE VII... ....... 7

CONCLUSION...................................................... 13

i

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases Page

Blum V. Stenson. 465 U.S. 886 (1984).................... 2, 9, 12

Bradley v. School Board, 416 U.S. 696 (1974)................... 2

Christiansburq Garment Co. v. EEOC. 434 U.S. 412

(1978)....................................................... 2, 7

Hensley v. Eckerhart. 461 U.S. 424 (1983)...................... 2

Hutto v. Finnev. 437 U.S. 678 (1978)..... ...................... 2

Independent Federation of Flight Attendants v. Zipes,

109 S. Ct. 2732 (1989)..................................... 8, 9

Johnson v. Georgia Highway Express, Inc.. 488 F.2d 714

(5th Cir. 1974)........... ............................. ....... 2

Newman v. Piggie Park Enterprises. Inc., 390 U.S. 400

(1968)................................. 2, 7

New York Gaslight Club, Inc, v. Carey. 447 U.S. 54

(1980)...................................................... 8, 12

*Pennsvlvania v. Delaware Valley Citizens Council

for Clean Air. 483 U.S. 711 (1987)......................... 8, 9

Statutes

42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(k) (1982)................................... 8

Legislative History

110 Cong. Rec. 12724 (1964) (Remarks of Senator Humphrey)..... 8

S. Rep. No. 1011, 94th Cong., 2d Sess., reprinted in. 1976

U.S. Code Cong. & Admin. News 5908.................... ........ 8

Authorities chiefly relied upon are marked with an asterisk.

- ii -

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA CIRCUIT

No. 89-7027

Cross Appeal No. 89-7028

MABEL A. KING

Appellant,

v.

JAMES F. PALMER, DIRECTOR

D.C. DEPARTMENT OF CORRECTIONS, et al.,

Appellees.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE DISTRICT OF COLUMBIA

BRIEF FOR AMICI CURIAE. THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL

FUND, INC., THE MEXICAN AMERICAN LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATIONAL FUND, THE WOMEN'S LEGAL DEFENSE FUND, THE

WASHINGTON LAWYERS' COMMITTEE FOR CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER

LAW, THE NATIONAL TREASURY EMPLOYEES UNION,

AND THE WASHINGTON COUNCIL OF LAWYERS

INTEREST OF AMICI

Amici are non-profit organizations that provide legal

representation, either through direct services or through

referral to lawyers in the private bar, for persons with

potential claims under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act, as.

amended, and other statutes that provide for fee shifting. In

light of the breadth of experience which these organizations

possess in this area, amici provide a unique perspective

concerning the availability of competent legal representation for

individuals with such claims.

The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.

("NAACP-LDF") is a non-profit corporation, incorporated under the

laws of the State of New York. It was formed in 1939 to assist

Blacks to secure their constitutional rights by the prosecution

of lawsuits. LDF attorneys have handled cases involving the

broad range of civil rights litigation, including numerous Title

VII cases, and have also participated in cases in the United

States Supreme Court and in many of the leading cases in other

courts involving attorney's fees questions, both as counsel and

as amicus curiae.

The Mexican American Legal Defense and Educational Fund

(,,MALDEF,,) is a national civil rights organization established in

1967. Its principal objective is to secure, through litigation

and education, the civil rights of Hispanics living in the United

States. With a litigation docket of more than 100 cases, MALDEF

through its staff attorneys and volunteer cooperating attorneys

provides legal representation to Hispanics who have been denied

their civil rights. The degree and extent of this legal

representation depends upon the receipt of market-based

attorney's fees awarded under fee-shifting statutes.

1 E . q . , Blum v. Stenson. 465 U.S. 886 (1984); Hensley v ■

Eckerhart, 461 U.S. 424 (1983); Hutto v. Finney, 437 U.S. 678

(1978); Christiansburq Garment Co. v. EEOC, 434 U.S. 412 (1978);

Bradley v. School Board. 416 U.S. 696 (1974); Newman v. Piggie

Park Enterprises, Inc., 390 U.S. 400 (1968); Johnson v. Georgia

Highway Express, Inc., 488 F.2d 714 (5th Cir. 1974).

2

The Women's Legal Defense Fund ("WLDF") is a non-profit,

tax-exempt national organization that advocates for the

advancement of women's rights and status before the courts and

before legislative and executive policymakers. One of WLDF's

primary goals is to ensure equal opportunity in the workplace,

and to that end it sponsors a litigation program that challenges

discrimination based on sex, primarily under Title VII, through

volunteer and staff lawyers. In accepting cases, WLDF attorneys

agree to seek only those fees awarded under the relevant fee-

shifting statute.

The Washington Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights Under

Law ("Lawyers' Committee") is a non-profit, tax-exempt

organization affiliated with the National Lawyers' Committee for

Civil Rights Under Law. The Lawyers' Committee was founded in

1968 to focus the resources and attention of the private bar on

civil rights issues and other legal issues affecting poor people

in this community. The Lawyers' Committee has represented the

interests of thousands of minorities and women in claims of equal

employment opportunity and fair housing arising under fee-

shifting statutes. Neither the Lawyers' Committee nor the more

than 100 law firms in the Washington Metropolitan Area which have

served as its co-counsel charge clients for the professional

services they render to civil rights claimants. Instead, the

Lawyers' Committee and its co-counsel rely on court-awarded fees

to compensate them for the representation they offer. The

availability of attorney's fees is essential to the continued

delivery of these legal services.

3

The National Treasury Employees Union ("NTEU") is a

federal sector labor organization that represents approximately

140,000 federal employees nationwide. In addition to serving as

their collective bargaining representative, NTEU frequently

conducts litigation in federal court on behalf of its

constituents, seeking to vindicate their civil and constitutional

rights, including rights arising under Title VII of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964, as amended. All of the Union's federal court

litigation is conducted by a small staff of salaried in-house

counsel who do not charge their clients a fee. B e c a u s e i t s

litigation activities are often funded by fee awards recovered

from the litigation of contingent cases, including Title VII

cases, NTEU has an important interest in the outcome of this

case.

The Washington Council of Lawyers ("WCL") is a

nonpartisan voluntary bar association founded in 1971, with

members representing every sector of the Washington legal

community — lawyers and legal assistants from large and small

firms, public-interest groups, government agencies, and

congressional offices, as well as law students and members of

law-related professions. The Washington Council is committed to

the principle of equal access to justice for all citizens. As

part of this commitment, the Washington Council regularly assists

and supports several of the other amici in their efforts to

provide representation to those with civil rights claims who

cannot pay for counsel out of their own funds.

4

Because of their unique "clearinghouse" role for the vast

majority of Title VII claimants in this community who are unable

to pay an hourly fee for legal representation, amici are

intimately familiar with the nexus between the availability of

competent counsel and risk enhanced fee awards for prevailing

plaintiffs. In view of their knowledge and experience in this

area, amici believe they can provide valuable assistance not

provided by the parties or other amici to the Court in addressing

one of the issues presented in this case, i.e.. the substantial

difficulty Title VII claimants would face in finding competent

counsel in the absence of the prospect of risk enhanced fee

awards.2

Moreover, because amici themselves represent plaintiffs

in many cases brought under Title VII and other statutes that

provide for fee shifting, amici have a very real stake in the

outcome of this case. In amici's experience, there are

significantly more cases that warrant further investigation and

prosecution than there are lawyers with whom they can place these

cases, leaving a substantial number of cases for amici themselves

to press. As a result, amici devote their own limited resources

to the litigation of these cases. Indeed, even after securing

private representation for some claimants, because of their

substantive expertise in these cases, amici frequently are asked

2 In compliance with Rule 11(e)(2) of the Local Rules of this

Court, amici have not reiterated the arguments made by Appellant

which address the other issues before the Court, but wish to

advise the Court that they join in Appellant's arguments

regarding these issues.

-5-

to remain in the case as co-counsel at their own expense. For

many of these organizations, the revenues generated by fee awards

greatly contribute to their budgets. But even with enhanced

compensation, they can effectively service only a fraction of the

potential claimants who look to them for legal assistance.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

To effectuate its legislative purpose of attracting

attorneys to Title VII litigation, Title VII's fee-shifting rule

must reflect the market practice in the Washington, D.C.

metropolitan area of providing counsel with compensation that is

enhanced for the risk of non-payment for the time invested. This

compensation is important to non-profit organizations that refer

clients to private attorneys because, in its absence, the

uncontroverted evidence clearly shows that attorneys will be

unwilling to undertake the task of pursuing Title VII claims.3

This compensation is no less important to organizations such as

amici who litigate these cases themselves. To the extent that

non-profit organizations do represent claimants, either alone or

as co-counsel with private attorneys, enhanced compensation

allows these organizations to allocate their scarce resources to

far more claimants than otherwise would be possible. Without the

availability of risk enhanced compensation, it is clear that

3 The numerous affidavits and declarations presented to the

District Court have been reproduced for this Court in the Joint

Appendix. See, e.q.. Joint Appendix at 130-31 (supplemental

declaration of George Chuzi).

6-

Title VII plaintiffs, as well as those with claims brought under

other similar fee-shifting statutes, would face "substantial

difficulties" finding legal representation from either the

private or the public interest bar.

ARGUMENT

I. CONTINGENCY ENHANCEMENTS ARE NECESSARY TO EFFECTUATE

THE PURPOSES OF FEE-SHIFTING UNDER TITLE VII

With the enactment of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act

in 1964, Congress adopted a broad public policy against

discrimination in the workplace. However, " [w]hen the Civil

Rights Act of 1964 was passed, it was evident that enforcement

would prove difficult and that the Nation would have to rely in

part upon private litigation as a means of securing broad

compliance with the law." Newman v. Piggie_Park— Enterprises,.

Inc.. 390 U.S. 400, 401 (1968). The Supreme Court has thus noted

that, in providing for a private cause of action for employment

discrimination, Congress cast the Title VII plaintiff in the role

of "a private attorney general," vindicating a policy "of the

highest priority." Christiansbura Garment Co. v. EEOC, 434 U.S.

412, 416 (1978). Indeed, history has borne out the significant

contribution made by private plaintiffs in the enforcement of the

Title VII mandate.

To encourage an individual worker and his or her

representative to act as "a private attorney general" and police

the workplace for discrimination, Congress found it necessary to

"make it easier for a plaintiff of limited means to bring a

-7-

meritorious suit." New York Gaslight Club, Inc, v. Carey, 447

U.S. 54, 63 (1980) (quoting remarks of Senator Humphrey, 110

Cong. Rec. 12724 (1964)). Congress therefore enacted § 706(k) of

Title VII, 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(k), which relieves an aggrieved

party of the cost of hiring an attorney by shifting that burden

to the pa r t y found to have p e r p e t r a t e d the illegal

discrimination. As the Supreme Court noted last Term, "[i]t is

of course true that the central purpose of § 706(k) is to

vindicate the national policy against wrongful discrimination by

encouraging victims to make the wrongdoers pay at law assuring

that the incentive to such suits will not be reduced by the

prospect of attorney's fees that consume the recovery."

Independent Federation of Flicrht Attendants v. Zipes, 109 S. Ct.

2732, 2736 (1989).

This fee-shifting provision serves its purpose by

allowing a prevailing plaintiff to collect "a reasonable

attorney's fee as part of the costs." 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(k). A

"reasonable attorney's fee," in turn, is one that is "adequate to

attract competent counsel, but . . . [that does] not produce

windfalls to attorneys." S. Rep. No. 1011, 94th Cong., 2d Sess.

6, reprinted in 1976 U.S. Code Cong. & Admin. News 5908, 5913.

Within this balance, Justice O'Connor, in her controlling

opinion on the issue, held that it is necessary to "consider[]

contingency in setting a reasonable fee under fee—shifting

provisions." Pennsylvania v. Delaware Valley— Citizens— Council.

for Clean Air. 483 U.S. 711, 731 (1987) (opinion of O'Connor, J.)

-8-

(Delaware Valley II).4 Specifically, the basic hourly rate is to

be increased to account for contingency because enhancement is

"necessary to bring the fee within the range that would attract

competent counsel." Id., 483 U.S. at 733. This risk enhancement

thus puts the plaintiff in a Title VII action on the same footing

in attracting competent counsel as clients who are able to pay an

attorney's hourly fee, which is what Congress intended when it

provided for fee-shifting.

Moreover, in order not to prejudice such claimants, a

reasonable attorney's fee award, including appropriate risk

enhancement, is due a claimant regardless of whether he secures

the services of a private attorney or a non-profit organization.

As the Supreme Court held in Blum v. Stenson, 465 U.S. 886, 894

(1984), "Congress did not intend the calculation of fee awards to

vary depending on whether [a] plaintiff was represented by

private counsel or by a nonprofit legal services organization."

In this way, the availability of competent counsel to prosecute

the actions of "private attorneys general" can be assured.

In the collective experience of amici, most of whom refer

cases to private attorneys for litigation, this risk premium is

crucial to implementing Congress's purpose of encouraging private

parties to mount their own Title VII claims. This conclusion was

made abundantly clear by the numerous declarations filed with the

4 Although Delaware Valiev II specifically concerned fee-shifting

under Section 304(d) of the Clean Air Act, 42 U.S.C. § 7604(d),

the Supreme Court has noted that all fee-shifting statutes with

similar "prevailing party" language are to be interpreted alike.

Zines. 109 S. Ct. at 2735 n.2 (citing cases).

-9-

District Court that have been reproduced for this Court in the

Joint Appendix. For example, as Julius Chambers, Director-

Counsel of the NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, stated

in his declaration before the District Court, "many meritorious

Title VII employment discrimination cases will not be brought

unless a substantial fee enhancement above the normal hourly

rates paid by noncontingent fee paying clients is given in cases

where the plaintiffs are successful." Joint Appendix at 115-16.

Joseph Sellers, Director of the Equal Employment Program

of the Washington Lawyers' Committee for Civil Rights Under Law,

quantified the difficulty of obtaining private counsel who are

willing to litigate referred cases. Between 1985 and 1987, the

program he directs reviewed 684 requests for assistance and

furnished legal representation together with private firms in

only thirty of them. In his experience,

private practitioners are increasingly

reluctant to undertake representation in EEO

cases on a contingency basis where the case

will require significant expenditure of

resources or will result in protracted

litigation. Given the substantial investment

of time and resources demanded by EEO cases in

which compensation is contingent on success in

the litigation, I believe that even fewer

practitioners in the future will be available

to furnish legal representation if there is no

prospect of obtaining an enhancement for risk

above the normal historic lodestar rate which

is in fact adequate [to] f i n a n c i a l l y

compensate practitioners for the risk of non

payment .

Joint Appendix at 254-55.

These accounts are supported by the declarations of

private practitioners which were filed in the District Court,

-10-

see, e.q . . Joint Appendix at 92 (declaration of Joel P. Bennett),

and which also appear in the brief amicus curiae filed in this

Court on behalf of several individual private practitioners. The

attorneys upon whom amici rely to accept referrals of contingent

fee cases assume substantial risks when they accept such cases --

risks that they increasingly are unwilling to accept in the

absence of enhanced fees when they prevail. Without a pool of

cooperating private attorneys willing to accept referrals, amici

will be unable to service the vast majority of potential

claimants who look to them for assistance in securing legal

representation.

Amici's own experience with private counsel confirms the

declarations presented to the District Court. Because employment

discrimination cases are typically highly complex and costly,

involve extensive discovery, and require the assistance of expert

consultants, private attorneys are reluctant to accept them on

referral from amici without some assurance of adequate

compensation. This is particularly true when these cases involve

the federal or District government as defendant. The virtually

unlimited resources of governmental defendants, which are

represented by a veritable army of tenacious lawyers, add to the

already formidable disincentives that private attorneys find in

representing even the most deserving plaintiffs. Given the

substantial time and resources that have to be devoted to these

cases, it is amici7s experience that private attorneys are only

willing to accept them if there is a firm guarantee of a

substantial contingency enhancement.

11-

Similarly, amici's experience as counsel for Title VII

claimants, either alone or as co-counsel with private attorneys,

underscores the compelling need for risk enhanced fees. For

example, members of the National Treasury Employees Union often

approach that organization to prosecute Title VII and other

discrimination claims on their behalf in federal court against

the government. However, the NTEU is able to assume

responsibility for only a fraction of these federal court cases

for many of the same reasons that private attorneys prove

unwilling to litigate them. As with private counsel, the

possibility of recovering an enhanced fee is a crucial

consideration in NTEU's determination as to whether it can

provide representation in federal court to victims of

discrimination. Clearly, then, enhanced fees greatly further the

common goal shared by Congress on the one hand, and amici and

similar organizations on the other: "mak[ing] it easier for a

plaintiff of limited means to bring a meritorious suit." New

York Gaslight. 447 U.S. at 63.

Without fee enhancement, the reduction in the resources

of amici and other similar organizations will impair their

ability to handle even the limited number of cases for which they

are currently responsible, with the result that meritorious suits

will not be brought. Last year, the more than two million

dollars in court-awarded attorney's fees collected by the NAACP-

LDF represented approximately 17% of that organizations' total

budget. Moreover, over 90% of the budget of the Equal Employment

Program of the Lawyer's Committee is funded by court-awarded

-12-

attorney's fees. A reduction in these fees would, without doubt,

reduce the capacity of these organizations to screen cases and

litigate them. Simultaneously, it would increase the demand for

their services, because a fee reduction would serve as an

additional disincentive for private attorneys who are already

reluctant to take these cases on referral. The result would be

especially problematic for potential claimants who cannot afford

to pay private attorneys' hourly fees and for organizations which

serve the same population as amici. but which have other sources

of significant funding, such as the government-funded Legal

Services Corporation. In the end, it can only be the case that

fewer employment discrimination claims will be brought,

regardless of their merit, to the frustration of clearly-stated

congressional purposes.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, amici respectfully request

that the panel opinion be reinstated.

Respectfully submitted,

ONEK, KLEIN & FARR

2550 M Street, N.W.

Suite 350

Washington, D.C. 20037

(202) 775-0184

-13-

Julius LaVonne Chambers

Charles Stephen Ralston

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE

AND EDUCATIONAL FUND

99 Hudson Street

Suite 1600

New York, NY 10013

E. Richard Larson

MEXICAN AMERICAN LEGAL DEFENSE

AND EDUCATIONAL FUND

634 South Spring Street

11th Floor

Los Angeles, CA 90014

Joseph M. Sellers

WASHINGTON LAWYERS' COMMITTEE FOR

CIVIL RIGHTS UNDER LAW

1400 I Street, N.W.

Suite 450

Washington, D.C. 20005

Donna Lenthoff

WOMEN'S LEGAL DEFENSE FUND

2000 P Street, N.W. Fund

Suite 400

Washington, D.C. 20036

Gregory O'Duden

Elaine Kaplan

Timothy Hannapel

NATIONAL TREASURY EMPLOYEES UNION

1730 K Street, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20006

Paul M. Smith

WASHINGTON COUNCIL OF LAWYERS

1200 New Hampshire Avenue, N.W.

Suite 700

Washington, D.C. 20036

-14-

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that on the 13th day of November, 1990

two copies of the foregoing Brief of Amicus Curiae NAACP Legal

Defense Fund, et al. was mailed first class, postage prepaid to

Robert M. Adler, Esq.

1667 "K" Street, N.W.

Suite 801

Washington, D.C. 20006

Bryan T. Veis, Esq.

Steptoe & Johnson

1330 Connecticut Avenue, N.W.

Washington, D.C. 20036

Herbert O. Reid, Esq.

Charles L. Reischel, Esq.

Donna M. Murasky, Esq.

450 - 5th Street, N.W.

Room 8C39

Washington, D.C. 20004