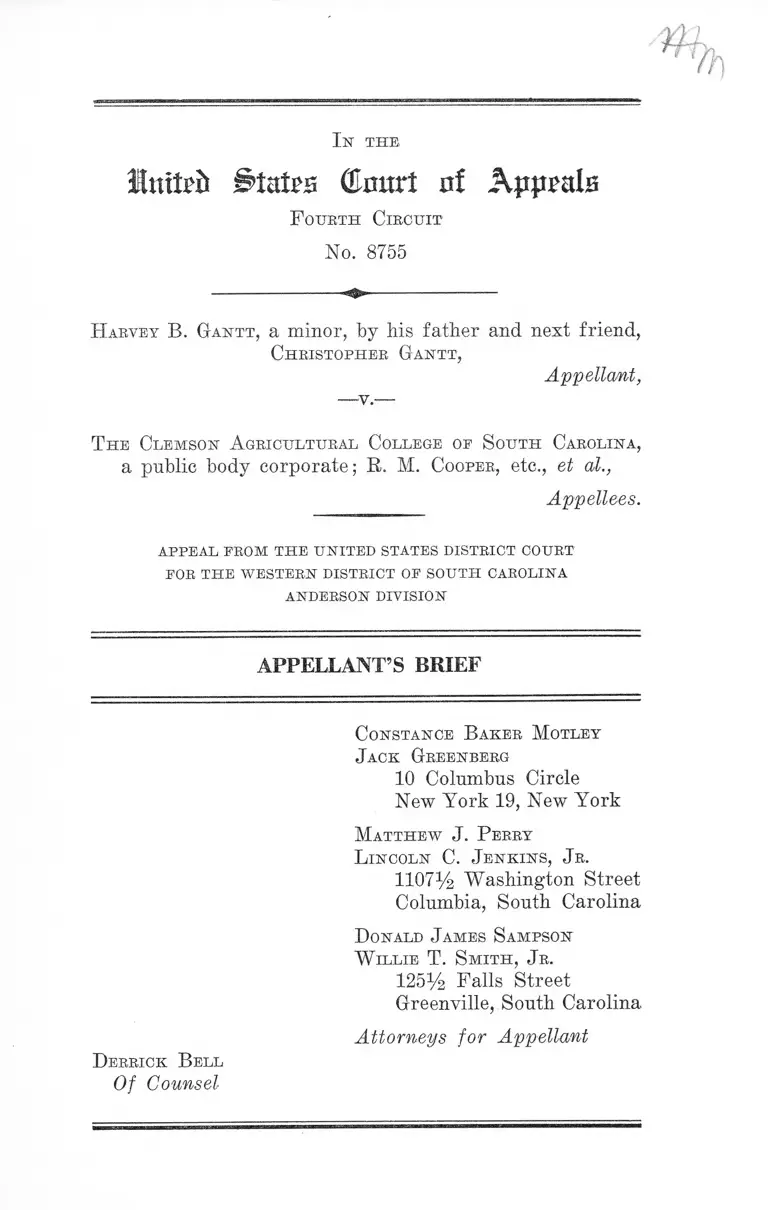

Gantt v. Clemson Agricultural College of South Carolina Appellant's Brief

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1963

This item is featured in:

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Gantt v. Clemson Agricultural College of South Carolina Appellant's Brief, 1963. 1fa8d7bb-b29a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/bfcc421e-01d2-4e6d-9158-99976b0fbe5f/gantt-v-clemson-agricultural-college-of-south-carolina-appellants-brief. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

finite States (Enart of Appeals

F ourth Circuit

No. 8755

I n the

H arvey B. Gantt, a minor, by his father and next friend,

Christopher Gantt,

Appellant,

-v.—

The Clemson A gricultural College oe S outh Carolina,

a public body corporate; R. M. Cooper, etc., et at.,

Appellees.

A P P E A L FR O M T H E U N IT E D STA TES D IS T R IC T COU RT

FO R T H E W E S T E R N D IS T R IC T OP S O U T H C A R O LIN A

A N D ER SO N D IV ISIO N

APPELLANT’S BRIEF

Constance B aker Motley

J ack Greenberg

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Matthew J. P erry

L incoln C. J enkins, J r.

11071/2 Washington Street

Columbia, South Carolina

D onald J ames S ampson

W illie T. S mith, J r.

125% Falls Street

Greenville, South Carolina

Attorneys for Appellant

D errick B ell

Of Counsel

INDEX TO BRIEF

Statement of the Case ................................................ 1

Question Presented ..................................................... 3

Statement of the Fact ......... ........................................ 4

A rgum ent :

The Denial by the Court Below of Appellant’s

Motion for a Preliminary Injunction, on the Record

in This Case, and the Law Applicable Thereto,

Was an Abuse of Discretion ................................ 14

A. The racial policy of Clemson College, reflected

by its adoption of the out-of-state scholarship

program and unreasonable “completed applica

tion” requirement, denies to appellant rights

protected by the Fourteenth Amendment ...... 14

B. The record in this case when applied to well-

settled principles of law left no discretion in

the court below to deny appellant’s preliminary

injunction ............ 20

Conclusion ...... 23

Table oe Cases

Avery v. Georgia, 345 U. S. 559 ........................ .......... 20

Booker v. State of Tenn. Bd. of Ed., 240 F. 2d 689

(6th Cir. 1957) cert. den. 353 U. S. 965 ........ ..... 18

Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U. S.

483 (1954) ...... 22

Davis v. Schnell, 81 F. Supp. 872, 878 (S. D. Ala. 1949)

aff’d. 336 U. S. 993 (1949)

PAGE

17

11

Eubanks v. Louisiana, 356 U. S. 584, 585 ..................... 20

Farley v. Turner, 281 F. 2d 131 (1960) ..................... 20

Frazier v. Board of Trustees of Univ. of N. C., 134

F. Supp. 589 (M. D. N. C. 1955) ....................... 18

Green v. School Board of City of Roanoke, Va., 304

F. 2d 118 (4th Cir. 1962) .......................................... 20

Hawkins v. Board of Control of Florida, 347 U. S.

971 (1955); 350 U. S. 413 (1956); 355 U. S. 839

(1957); 162 F. Supp. 851 (N. D. Fla. 1957) .......18, 21, 22

Henry v. Greenville Airport Commission, 284 F. 2d

631 (4th Cir. 1960) ......................... ....................... 22. 23

Hernandez v. Texas, 347 U. S. 475 ................................ 20

Holmes v. Danner, 191 F. Supp. 394 (M. D. Ga,

1961) ................................................................... .18,19,22

Hunt, et al. v. Arnold, et al. (N. D. Ga, 1959), 172

F. Supp. 847, 852-853 .............................................. 18,19

Hurd v. Hodge, 334 U. S. 24 (1948) ......................... 22

Lucy v. Adams (N. D. Ala. 1955), 134 F. Supp. 235,

afPd. 228 F. 2d 619 (5th Cir. 1955), cert. den. 351

U. S. 931. See also 350 H. S. 1 (1955) ................. 18, 21, 22

Ludley v. Board of Supervisors of L.S.U., 150 F. Supp.

900 (E. D. La. 1957) aff’d. 252 F. 2d 372 (5th Cir.

1958) cert. den. 358 U. S. 819................. ..................17,18

McCoy v. Greensboro City Board of Education, 283

F. 2d 667 (4th Cir. 1960) reversing 179 F. Supp.

745 (M. D. N. C. 1960) .............................................. 20

McKissick v. Carmichael, 187 F. 2d 949 (4th Cir. 1951),

cert, denied 341 U. S. 951 ................ ................ ...... 18

McLaurin v. Board of Regents, 339 U. S. 637 (1950) ..18, 21

PAGE

Ill

Meredith v. Fair, 199 F. Supp. 754 (S. D. Miss., 1961)

aff’d. 298 F. 2d 696 (5tli Cir. 1962), 202 F. Supp. 224

(S. D. Miss., 1962), rev’d. — — F. 2 d ----- (5th Cir.,

June 25, 1962) ......... ..... ............................17,18,19,21,22

Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 IT. S. 337 (1938) .. 16

Norris v. Alabama, 294 U. S. 587 (1935) .................... . 20

Parker v. University of Delaware, 31 Del. Ch. 381,

75 A. 2d 225 (Del. Ch. 1950) ...... ......................... 18

Reece v. Georgia, 350 U. S. 85 ................................... 20

Sipuel v. Board of Regents, 332 U. S. 631 (1948) ..... . 21

Swanson v. Univ. of Virginia, Civil Action No. 30

(W. D. Va. 1950) (unreported) ................................ 18

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629 (1950) ..................... 21

Tureaud v. Board of Supervisors of L.S.U., 116

F. Supp. 248 (E. D. La. 1953) rev’d. 207 F. 2d 807

(5th Cir. 1953) vacated and remanded 347 U. S. 971

(1954) on remand 225 F. 2d 434 (5th Cir. 1955) on

rehearing 228 F. 2d 895 (5th Cir. 1956), cert. den.

351 U. S. 924 ....... .........................- ............................. 18

Wilson v. Board of Supervisors of L.S.U., 92 F. Supp.

986 (E. D. La. 1950), aff’d. 340 U. S. 909 (1938) .... 18

Wilson v. City of Paducah, Ky., 100 F. Supp. 116

(W. D. Ky. 1951) ................................................... . 18

Other A uthority

Greenberg, Race Relations and American Law (1960),

p. 262, n. 192 ........... .... ....——........-.................—- 18

PAGE

I n the

Inttefr States CEourt nf Appeals

F ourth Circuit

No. 8755

H arvey B. Gantt, a minor, by his father and next friend,

C h r is t o p h e r Gantt,

Appellant,

T he Clemson A gricultural College of S outh Carolina,

a public body corporate; R. M. Cooper, etc., et al.,

Appellees.

A P P E A L FR O M T H E U N IT E D STA TES D IS T R IC T COU RT

FO R T H E W E S T E R N D IS T R IC T OF S O U T H CA RO LIN A

A N D ER SO N D IV ISIO N

APPELLANT’S BRIEF

Statement of the Case

This is an appeal from an order of the United States

District Court, Western District, South Carolina, Ander

son Division, entered September 7, 1962, denying appel

lant’s motion for preliminary injunction securing his admis

sion to Clemson, a state college in South Carolina (191a).

The order was entered following a hearing on the motion

on August 22, 1962. The President of Clemson testified

(44a), and the appellant took the stand briefly (66a). In

additional support of the motion, the appellees placed in

evidence the depositions of the registrar of Clemson (Pi’s.

Exh. 31, 118a), and the Administrative Secretary of the

State Regional Education Board (Pi’s. Exh. 32, 163a).

2

Finally, the appellant introduced correspondence between

himself and the registrar over a period of more than a

year (Pi’s. Exhs. 1-24, 77a-107a), the Clemson College

catalog requirements for admission (Pi’s. Exhs. 25-30, 108a-

115a), and the Rules and Regulations of the State Regional

Education Board which defines state policy with respect

to the education of Negro college students (Pi’s. Exh. 33,

187a).

The action was commenced on July 7, 1962 after more

than a year’s correspondence between the appellant and

the registrar during which the registrar never advised

appellant that he was eligible for admission to the college

or would be admitted subject to the fulfillment of certain

requirements. The appellees answered the complaint on

July 28, 1962, and admitted that the Clemson Agricultural

College of South Carolina is a body corporate under South

Carolina law and that the individual appellees constitute

the Board of Trustees of the college1 (15a).

The answer admitted that Kenneth N. Vickery is the

registrar of the college (17a), admitted the appellant’s race,

residence and citizenship (16a), and admitted that the regis

trar received a transcript of the appellant’s work at Iowa

State University showing satisfactory completion of two

years’ work toward a degree in architectural engineering

(19a).

The answer then alleges that the college did not receive

information requested of appellant by letter to him dated

July 2, 1962 from the Dean of the School of Architecture

requesting appellant to furnish a portfolio of work in archi

1 One member of the Board had resigned. One had died but no

successors had been appointed. The answer also stated that Mr.

J . T. Anderson, Superintendent of Education of the State of South

Carolina, who was made a defendant had no connection with the

college (20a).

3

tectural design and drawing done by him at Iowa State

University. The letter, a copy of which was attached to

the answer as Exhibit “P” stated that this information

was:

To assist us in the evaluation . . . of your work in archi

tectural design and drawing at Iowra State University

* * * * #

The more complete the portfolio is the better our eval

uation can be (Pi’s. Exh. 20,101a).

However, the evidence on the hearing of appellant’s motion

showed that the appellant had offered to furnish this in

formation, but the appellees refused to accept same on the

ground that the apjoellant had instituted this action. Suit

was instituted by appellant’s counsel at the time the letter

was received by the appellant. No other reason for denying

appellant’s admission to Clemson College was alleged in

the answer.

In denying appellant’s motion for preliminary injunc

tion, the court below found that there are material issues

of fact in dispute, and that appellant failed to prove that

his application was treated differently because of his race

(203a).

Question Presented

Whether the court below abused its discretion in deny

ing a preliminary injunction securing the admission of the

appellant to the Clemson College of Agriculture of South

Carolina following a hearing on appellant’s motion for pre

liminary injunction.

4

Statement of the Facts

Appellant is a nineteen year old Negro resident of the

State of South Carolina (66a). He evidenced interest in

enrolling in the Clemson Agricultural College of South

Carolina, even as a High School Junior, and in 1959, wrote

the College, requested a bulletin of the School of Engineer

ing and expressed definite interest in the School of Archi

tecture (Pi’s. Exh. 1, 77a).

1. The Out-oj-State Scholarship Program .

After graduation from high school in June 1960, (Pi’s.

Exh. 5, 81a), appellant enrolled in Iowa State in Septem

ber 1960, using out-of-state scholarship aid provided by the

South Carolina Regional Education Board, a state agency

which provides financial aid to Negro students who desire

courses not available to them in state-supported schools in

South Carolina (Pi’s. Exh. 6, 82a; Pi’s. Exh. 32, 167a-168a,

174a-176a; Pi’s. Exh. 33,187a).

It is undisputed that appellant is attending Iowa State

College with financial aid from the state even though archi

tecture is offered at Clemson (Pi’s. Exh. 31, 129a-130a),

because he cannot take a course in architecture at South

Carolina State College for Negroes at Orangeburg and such

a course is not available to Negroes at any other state in

stitution of higher learning (Pi’s. Exh. 32,168a).

It is also undisputed that there never has been any change

in the policy of South Carolina of providing separate but

equal education for Negroes on the college level (Pi’s. Exh.

31, 129a.-130a, 135a-136a; Pi’s. Exh. 32, 167a-168a; Pi’s.

Exh. 33). As a matter of fact, admission of Negroes has

not even been discussed by the Clemson Board of Trustees.

And although the application of appellant has been pending

5

since January 1961, that Board has never discussed appel

lant’s application (45a-49a).

Moreover, when the appellant applied for admission to

Clemson both the registrar and the president of the college

inquired of the Regional Education Board whether the ap

pellant was receiving out-of-state scholarship aid (Pi’s.

Exh. 31,136a-139a ; Pi’s. Exh. 32,176a-177a), and when they

learned that he was receiving such aid, returned his appli

cation (Pi’s. Exh. 6, 82a).

2. The “C om pleted A pplication ” R equirem ent, 1961.

On his application for admission to the September 1961

term at Clemson College filed in January 1961, appellant

was required to state his race, and responded with the letter

“N” in the blank following the word “race.” Appellant also

indicated on his application that he was enrolled at Iowa

State and desired to take a course in architecture at Clem

son in September 1961 (Pi’s. Exh. 5, 81a).

In reply to the registrar’s letter of January 19, 1961

(Pi’s. Exh. 6, 82a), returning his application because he

was receiving out-of-state aid, appellant merely wrote Mr.

Vickery in February 1961, returned his application and

requested that it be processed for entry in September 1961

(Pi’s. Exh. 7, 83a).

On February 17, 1961, the registrar answered, stating

that the application “ . . . is being placed with the pending

applications” (Pi’s. Exh. 8, 84a). Almost three months

later, and in response to appellant’s letter of April 26, 1961

inquiring as to the status of his application, the registrar

wrote on May 9:

“In response to your letter of April 26 I beg to

advise that as of this date no applications from any

prospective transfer students have been processed”

(Pi’s. Exh. 9, 85a).

6

When by May 29, 1961, appellant did not hear from the

registrar, he wrote again inquiring as to the requirements

for admission as a transfer student. In reply, the registrar

wrote on June 8, 1961 for the first time informing him that

the requirements included the following:

(1) Satisfactory scores on the College Entrance

Examination Board tests, including the scholastic ap

titude test and achievement tests in English composi

tion and intermediate mathematics. If you have taken

these examinations, you may request the College

Board, Box 592, Princeton, New Jersey, to forward

your scores to this office.

(2) An official transcript of your academic record

to date at Iowa State University, including entrance

credits.

(3) A statement from Iowa State University that

you are entitled to an honorable discharge from that

University, and that you are eligible to return to that

institution next semester.

The registrar pointed out that none of this information

had been received as of that date (Pi’s. Exh. 10, 86a).

Appellant, of course, had not previously known of these

requirements.

Thereafter, on June 17, 1961, appellant wrote the regis

trar that: (1) he was arranging to take the College Entrance

Examination Board Test, (2) he had requested an official

transcript of his Iowa State record, and (3) had requested

the statement of honorable discharge and eligibility for

readmission to the Iowa school. The letter contained this

sentence:

“Meanwhile, if there are any other requirements

which I should meet in connection with my desire to

7

enter Clemson, I shall appreciate your so advising me”

(Pi’s. Exh. 11, 88a).

The registrar did not respond until August 31, 1961

when he wrote appellant that although his application had

been pending since February 7, 1961 (the date on which

appellant returned his application) it was then impracti

cable for the registrar’s office to process his application in

time for admission in September 1961 since the new students

were expected to matriculate beginning September 8, 1961.

This letter indicated the following with respect to the status

of appellant’s application: 1) the College Entrance Exam

ination Test score had been received too late to allow suffi

cient time for the Director of Admissions to complete

investigation of “other requirements for admission” and,

2) the required personal interview was incomplete.

No other deficiencies with respect to appellant’s applica

tion were noted (Pi’s. Exh. 12, 89a). Moreover, appellant

hacl received no prior notice that his application for admis

sion to the September 1961 term could not be considered

after a certain date and had not been advised, prior to that

time, of the necessity for a personal interview (59a).

Suddenly, on October 13, 1961, the registrar wrote appel

lant as follows:

“As you were advised by my form letter dated Au

gust 31, 1961, your incomplete application for admis

sion to Clemson College for the semester beginning in

September 1961 was canceled for the reasons indicated”

(Pi’s. Exh. 13, 92a).

The letter of August 31, 1961 advised of no such can

cellation (Pi’s. Exh. 12, 89a). The letter then proceeded

to advise the appellant that all other pending applications

not completed prior to the beginning of the fall semester

8

were likewise canceled. The October 13, 1961 letter further

advised appellant that he had no “pending application” for

admission at any future date but he was free to apply for

admission “at the beginning of any subsequent semester”

(Pi’s. Exh. 13, 92a). Finally, this letter advised appellant

that he would be called for a personal interview before

a final decision was made on his application but that the

interview would not be scheduled until his application was

otherwise complete. The letter concluded with this sentence,

“The application must have been completed in time to

permit the scheduling of the interview prior to the re

quested entrance date” (Pi’s. Exh. 13, 92a). The interview

has never been scheduled.

3 . The “ C om pleted A pplication” R equirem ent, 1962.

On November 13, 1961 appellant wrote Mr. Vickery of

his surprise to learn that his application had been can

celed, since the letter of August 31, 1961 gave him the

definite impression that his application was still pending,

and requested the registrar to consider his pending appli

cation as a continuing one or, if this were not possible,

to send him a new application (Pi’s. Exh. 14, 94a). A new

application was sent and returned to the registrar on

December 6, 1961 (Pi’s. Exh. 16, 96a). Appellant requested

that this application be considered for the next semester,

which would have been January 1962, and, if not processed

in time, considered for the September 1962 term (Pi’s.

Exh. 15, 95a). Almost five months later, appellant not

having heard from the registrar, wrote again inquiring as

to the status of his application and again inquiring as to

the admission requirements. The registrar replied on May

21, 1962, forwarded a catalog under separate cover, and

stated that:

9

“ . . . the College cannot act on any application until

the necessary information has been submitted in full”

(Pi’s. Exh. 17, 98a).

No deficiencies were pointed out to the applicant. On June

13th appellant appeared in the office of the registrar for

the purpose of being interviewed. At that time he was

advised that he could not be interviewed because his tran

script from Iowra State College had not then arrived for

the 1961-62 academic year although a transcript had been

received for the 1960-61 academic year (53a-55a). The

appellant was not interviewed on June 13 despite the fact

that the president testified that the interview was designed

to determine certain “intangibles” about the applicant, such

as, motivation (50a-51a).

On June 26, appellant wired the registrar that a tran-

scipt of his work at Iowa State College had been forwarded

to Clemson and requested favorable consideration of his

application and the required interview. A reply within

48 hours was requested (Pi’s. Exh. 18, 99a). In reply, on

June 28, the registrar telegrammed as follows:

Betel June 26, Transcript received. Tour application

along with all others pending completion is being

processed in manner we advised during your visit to

this office on June 13. You will be advised date for

interview as soon as other details relative to your ap

plication have been completed (Pi’s. Exh. 19, 100a).

It should be noted that despite the registrar’s continued

reference to the necessity for an interview, the president

testified on August 22, 1962 that it had not been deter

mined whether an interview would be required in appel

lant’s case (55a). This was the president’s position at that

late date despite his own finding that he has “seen nothing

10

in his [appellant’s] file at this point that would indicate

that he isn’t a very good student” (53a). The president

also testified that appellant’s academic record was “unques

tionably above average” (55a). And neither the pleadings,

affidavits, depositions or testimony upon motion for pre

liminary injunction have even suggested any character

deficiency on the part of appellant.

On July 2, 1962 the Dean of the School of Architecture,

Harlan E. McClure, wrote appellant, with a copy to the

registrar, that appellant’s transcript from Iowa State

University had been handed to the School of Architecture

for analysis and evaluation, but that such evaluation was

difficult, as in every transfer case, because of the problem

of equating courses at one school with courses given at

the other. To assist in this evaluation, the Dean requested

a “portfolio” of appellant’s work in architectural design

and drawing with an indication of the duration of the

exercises submitted and advised appellant he might submit

any other creative work which he cared to show, since

the more complete the “portfolio” the better the evaluation

would be. The letter concluded with the suggestion that

appellant come for a conference at the time he submitted

the information, however, the letter pointed out that, “This

conference will have to do with the standards and pro

cedures of the School of Architecture and will not be a

substitute for the preacceptance interview provided by the

College admission policies” (Pi’s. Exh. 20, 101a).

On July 13, 1962 the appellant wrote the Dean that he

would be happy to furnish the information requested al

though he could not furnish all the design and drawing

done at Iowa State since a great deal of it was kept by

the Department of Architecture; however, he would be

happy to furnish whatever he had and any other informa

tion required. Appellant desired to know, however, wheth

11

er in view of the filing of a suit which coincided with the

Dean’s letter, the Dean wished him to comply with the

request for the review of the work at Iowa State (Pi’s.

Exh. 22, 104a). In reply to this, appellant’s attorney re

ceived a letter from the attorney for Clemson College

which stated in part:

“In view of the fact that the administrative remedies

of the College are under attack in this case, it would

seem to us to be highly inappropriate that there be

any further consideration of this client’s application

while litigation is pending . . . this will explain why

we have advised Dean McClure not to reply to the

letter” (Pi’s. Exh. 23,106a).

Appellant’s attorney then wrote that appellant “wanted

Dean McClure and other officials to understand his will

ingness to submit to the requirements of the College”

despite the fact that he had brought an action to gain

his admission (Pi’s. Exh. 24, 107a).

The appellant has met all requirements for admission to

Clemson College as set forth in the Clemson College Record,

1960-61 (Pi’s. Exhs. 25-27, 108a, 111a), and in the Clemson

College Record, 1961-62 (Pi’s. Exhs. 28-30, 112a-115a).

The request of Dean McClure for an opportunity to evalu

ate appellant’s architectural designs and drawings at Iowa

State is not a stated or even implied requirement for admis

sion. Appellant was never even advised by letter that an

evaluation of credits at a previous school was a condition

of admission. This suggestion was made for the first time

in the answer filed by appellees in this action. The answer

claimed that appellant had failed to supply a portfolio of

his work (19a). However, the evidence shows the contrary

(Pi’s. Exhs. 22, 23, 24, 104a-108a).

12

Moreover, tie president testified that interviews are not

given in every case, that the registrar reviews the record

and determines “whether or not he [feels] there [is] some

thing that indicate[s] an interview” (53a). Less than

100 applicants have been subjected to such interviews for

the September 1962 term, although as of August 22, 1962,

600 or more applications for admission were still “pend

ing” (59a-60a).

The Clemson College Record, 1961-62, provides as fol

lows with respect to transfer applicants:

“The applicant must present for consideration;

(a) a statement of honorary discharge from the insti

tution last attended,

(b) an official transcript of his record, including en

trance credits, and

(c) an official statement that he is eligible to return

to the institution last attended” (Pi’s. Exh. 29, 113a).

The appellant has complied with these requirements

(Pi’s. Exh. 19a, 100a).

The Record then provides:

“College credits given by transfer are provisional

and may be canceled at any time if the student’s work

is unsatisfactory” (Pi’s. Exh. 29, 113a).

The Record further provides as follows:

“In order for a transfer student to be considered

for enrollment his complete application including test

scores, transcripts, and statement of eligibility must

be on file in the Admissions Office at least two weeks

prior to the date of desired matriculation” (Pi’s. Exh.

29, 114a).

The appellant has complied with this requirement.

13

The Record also required that for admission in Septem

ber 1962, these materials must be submitted no later than

August 23, 1962. The appellant’s test score, transcript,

statement of honorable discharge and statement of eligibil

ity to return to Iowa State were all submitted prior to

August 23, 1962. His transcript was mailed June 13, 1962

(Pi’s. Exhs. 18, 19, 99a-100a). His test score was received

prior to August 31, 1961 (Pi’s. Exh. 12, 90a). His applica

tion has been pending since January 1961 (Pi’s. Exh. 6,

82a). The appellant had never been advised, prior to filing

suit, that his credits would have to be evaluated before ad

mission to the College and he has never been advised, ac

cording to the president’s testimony, that an interview would

be required in his case (55a).

14

ARGUMENT

The Denial by the Court Below of Appellant’s Motion

for a Preliminary Injunction, on the Record in This

Case, and the Law Applicable Thereto, Was an Abuse of

Discretion.

A. The racial policy of Clemson College, reflected by

its adoption of the out-of-state scholarship program

and unreasonable “ completed application” require

ment, denies to appellant rights protected by the

Fourteenth Amendment.

Appellant comes here seeking this Court’s aid after ex

pending eighteen frustrating months in an unsuccessful ef

fort to enter Clemson College. While appellant filed appli

cations on three occasions he was unable to complete appli

cation procedures to appellees’ satisfaction. The appellees

contend that applicant’s application was treated no differ

ently because it contained the question “Race”, and he

responded, “N” (Pi’s. Exhs. 5, 16, 81a, 97a). However,

appellant submits that what the state does is more enlight

ening here than what it says.

For sixty-nine years, the State of South Carolina has

been operating Clemson College, and in all that time, no

Negro student has ever been admitted. Until recent deci

sions of the United States Supreme Court, Negroes were

admittedly excluded from Clemson. More recently, officials

claim that race is no longer a factor in the admission of

students (130a, 151a). However, the Board of Trustees has

never advised the registrar or other school officials that

the separate but equal policy has changed, and no public

announcement has been made that the school now accepts

students without regard to race. Perhaps most significant,

of the five or six Negroes who have applied since 1938, not

only have none been accepted, but like the appellant, none

15

have ever “completed their applications” (Pi’s. Exh. 31,

127a, 131a).

A newsletter sent out by the Registrar’s Office to high

schools in the state outlining and explaining admission

policies set forth in the catalog (Pi’s. Exh. 31,118a), is sent

only to white high schools (Pi’s. Exh. 31,120a). In addition,

Rule No. 1 of the Rules and Regulations of the South Caro

lina Regional Education Board, a state agency governing

scholarship aid for study at out-of-state institutions pro

vides :

“1. Scholarships may be granted to study courses which

are not offered at South Carolina State College in

Orangeburg, but which are offered at state-sup

ported institutions within the State of South Caro

lina which are not available to Negro students”

(Pi’s. Exh. 33,187a).

In explanation of this rule, the Administrative Secretary

of the Regional Educational Board testified that at the

present time, South Carolina State College, a state sup

ported school in Orangeburg is the only state supported

college in South Carolina open to Negro students (Pi’s.

Exh. 32,168a).

“Q. Now then, let us go to this situation. Is it not a

fact that there are courses of study offered to white

students in white supported institutions in South Caro

lina that are not offered at South Carolina State Col

lege in Orangeburg? A. That is true.

“Q. Now, does not your office furnish out of state aid

for negro students who cannot obtain at South Carolina

State College certain courses of study, but those same

courses of study are offered to white students in other

white institutions in South Carolina? A. That’s true.

16

“Q. And those are other white—State supported in

stitutions to which we refer, is that not a fact? A.

Yes sir” (Pi’s. Exli. 32,170a).

The out-of-state scholarship program for Negroes was

held constitutionally void as an equal protection measure

in 1938. Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337

(1938). Nevertheless, the Administrative Secretary further

testified that she presently handles about 600 to 650 appli

cations, approximately 370 of which are from Negroes who

are enrolled in out of state institutions for courses not

offered at the all-Negro South Carolina State College in

Orangeburg (Pi’s. Exh. 32,174a). She stated that normally,

Negro students seeking out-of-state aid write: “I cannot

receive the course or the degree that I am seeking in South

Carolina, it is not offered at State College” (Pi’s. Exh. 32,

184a). Upon receipt of such requests, state officials provide

all qualified Negro students with scholarship funds up to

$500 per year for tuition and transportation expenses.

For two years, the appellant has received scholarship aid

from the Regional Educational Board. When he submitted

his first application to Clemson College in January 1961

(Pi’s. Exh. 5, 81a), the Registrar did not inform appellant

that he was improperly receiving out-of-state aid since he

was eligible to take architecture courses at Clemson, rather

he noted that appellant was receiving state aid, impliedly

advised him to continue doing so, and returned his applica

tion to him (Pi’s. Exh. 6, 82a).

The lengthy correspondence that ensued has been made

a part of the record and has been reviewed in the statement

of facts. There is no factual dispute as to any of it. Rather

than point out each instance of appellees’ delay in respond

ing to his inquiries, and their failure to advise him of re

quirements, prerequisites, interviews, tests, and cut-off

17

dates in a timely manner, appellant submits that these

dilatory proceedings are in perfect harmony with the policy

of limiting Clemson College to white students; a policy ad

mittedly in effect a few years ago, never officially aban

doned, and adhered to in principle by the Registrar when

he learned appellant was a Negro, informed the College

President, .ascertained from the Regional Educational

Board that appellant was receiving out-of-state aid, and

indicated his ineligibility to enroll at Clemson by returning

his application. The lengthy correspondence that followed,

when considered in the realistic light of what is actually

done in South Carolina by Negro students and state offi

cials, clarifies rather than confuses the issues posed here.

As the Fifth Circuit, reviewing similar facts, recently said

in taking* judicial notice of Mississippi’s policy of segrega

tion in its schools and colleges, “What everybody knows the

court must know.” Meredith v. Fair,----- F. 2 d ------ (5th

Cir., June 25, 1962). See also Board of Supervisors of

Louisiana St. v. Ludley, 252 F. 2d 372, 376 (5th Cir. 1958);

Davis v. Schnell, 81 F. Supp. 872, 878 (S. D. Ala. 1949),

aff’d. 336 F. S. 933 (1949).

The refusal of appellees to promptly process and de

termine appellant’s application, when as here, such failure

is so obviously a part of a discriminatory policy is no less

a violation of appellant’s constitutional rights than an

outright refusal to consider his application because he is a

Negro. Indeed, the only discernible difference between the

response appellant’s application elicited and that received

by Negroes who applied during separate-but-equal days

is that while the earlier Negroes were referred to the

Negro school at Orangeburg (Pi’s. Exh. 32, 130a), appel

lant was referred to the integrated school in Iowa. Ap

pellant submits that the distinction is without a constitu

tional difference, and that the court decisions which in

virtually every southern state except South Carolina have

18

held invalid the refusal to admit Negro students to state

colleges are entirely applicable to appellee’s refusal here.2

2 Oklahoma

Louisiana

Delaware

Virginia

Kentucky

Alabama

— McLaurin v. Board of Regents, 339 U. S. 637

(1950);

— Wilson v. Board of Supervisors of L.S.U.,

92 F. Supp. 986 (E. D. La. 1950) aff’d 340

U. S. 909; Ludley v. Board of Supervisors of

L.S.U., 150 F. Supp. 900 (E. D. La. 1957),

aff’d 252 F. 2d 372 (5th Cir. 1958), cert. den.

358 U. S. 819; Tureaud v. Board of Super

visors of L.S.U., 116 F. Supp. 248 (E. D.

La. 1953) rev’d 207 F. 2d 807 (5th Cir.

1953) vacated and remanded 347 IT. S. 971

(1954) on remand 225 F. 2d 434 (5th Cir.

1955) on rehearing 228 F. 2d 895 (5th Cir.

1956) cert. den. 351 U. S. 924;

— Parker v. University of Delaware, 31 Del.

Ch. 381, 75 A. 2d 225 (Del. Ch. 1950);

— Swanson v. University of Virginia, Civ. No.

30 (W. D. Va. 1950) (Unreported);

— Wilson v. City of Paducah, Ky., 100 F. Supp.

116 (W. D. Ky. 1951);

— Lucy v. Adams, 134 F. Supp. 235, aff’d 228

F. 2d 619, cert. den. 351 U. S. 931; see also

350 U. S. 1;

North Carolina— Frazier v. Board of Trustees Univ. of N. S.,

134 F. Supp. 589 (M. D. N. C. 1955) ; Mc-

Kissick v. Carmichael, 187 F. 2d 949 (4th

Cir. 1951) ;

Tennessee — Booker v. State of Tenn. Bd. of Ed., 240 F.

2d 689 (6th Cir. 1957); cert. den. 353 U. S.

965;

Florida — Hawkins v. Board of Control of Florida, 347

U. S. 971 (1955); 350 U. S. 413 (1956);

355 U. S. 839 (1957) 162 F. Supp. 851

(N. D. Fla. 1957);

Georgia — Hunt v. Arnold, 172 F. Supp. 847 (N. D.

Ga. 1959) ; Holmes v. Danner, 191 F. Supp.

394 (M. D. Ga. 1961);

Mississippi — Meredith v. Fair, 199 F. Supp. 754 (S. D.

Miss. 1961), aff’d 298 F. 2d 696 (5th Cir.

1962), 202 F. Supp. 224 (S. D. Miss. 1962),

rev’d ----- - F. 2d ------ (5th Cir. June 25,

1962).

Arkansas voluntarily admitted Negroes in 1950, following

threat of legal action. Greenberg, Race Relations and Amer

ican Law (1960), p. 262, n. 192.

19

Appellees’ defense that Clemson has no policy regarding

the admission of Negroes (48a) has been tried in Georgia,

Alabama and Mississippi without success. Holmes v. Dan

ner, 191 F. Supp. 394, 402 (M. D. Ga. 1961); Lucy v. Adams,

134 F. Supp. 235 (N. D. Ala. 1955), aff’d. 228 F. 2d 619

(5th Cir. 1955), aff’d. 228 F. 2d 619 (5th Cir. 1955), cert,

den. 351 IT. S. 931. See also 350 U. S. 1 (1955); Meredith

v. Fair, 199 F. Supp. 754 (S. D. Miss. 1961), aff’d. 298 F. 2d

696 (5th Cir. 1962), 202 F. Supp. 224 (S. D. Miss. 1962),

rev’d .----- F. 2 d ------ (5th Cir. June 25, 1962). Even the

claim that appellant’s application has not been completed

is not new. Holmes v. Danner, 191 F. Supp. 385, 390, 393

(M. D. Ga. 1960).

The court below’s finding that no decision can be reached

on the issue of whether appellant’s application was treated

in the same manner as all other applications until the

treatment given such other applications is reviewed (202a)

would be appropriate if appellant had brought this action

in a state where Negroes have regularly been permitted to

apply and enroll in the state schools of their choice. Such

is not the case in South Carolina. The record shows as

much. It further shows that appellant, a Negro and a

good student was given a state scholarship to attend an

out-of-state college, and his attempts to apply at Clemson

College have received something considerably less than

helpful support from appellees.

Where a state school which has never admitted a Negro,

refuses to admit or even pass on the application of one

whom its officials admit is eminently qualified, and defends

on grounds similar to those offered by other states faced

with the same problem, appellant submits that the burden

falls to the school to show by more than mere denials of

racial discrimination that white students similarly situated

are treated in like fashion. This Court has frequently re

20

quired as much of school boards who seek to administer

desegregation of public schools through pupil placement

plans. Administrative remedies provided by such plans

need not be exhausted where, because the policy of seg

regation has not been abandoned, such exhaustion would

be useless and futile. Farley v. Turner, 281 F. 2d 131

(1960); McCoy v. Greensboro City Board of Education, 283

F. 2d 667 (1960); Green v. School Board of City of Roanoke,

Va., 304 F. 2d 118 (4th Cir. 1962).

In the analogous cases involving allegations by a Negro

criminal defendant of exclusion of Negroes from the jury,

see cases cited in Eubanks v. Louisiana, 356 IT. S. 584, 585,

proof that Negroes constitute a substantial segment of the

population, that some Negroes are qualified to serve as

jurors, and that, for an extended period of time none has

been called for jury service, see Hernandez v. Texas, 347

IT. S. 475; Norris v. Alabama, 294 U. S. 587, cannot be

rebutted by mere denials of state officials that there was

racial discrimination. Avery v. Georgia, 345 IT. S. 559;

Reece v. Georgia, 350 U. S. 85; Eubanks v. Louisiana, supra.

Pending such proof that Clemson is no longer a school

for white students only, appellant is entitled to relief

which will protect his rights under the Fourteenth Amend

ment to the United States Constitution.

B. The record in this case when applied to well-settled

principles of law left no discretion in the court below

to deny appellant’s prelim inary injunction.

Appellant has completed two years of college at Iowa

State, and has for more than a year, vainly tried to transfer

to Clemson College. Appellees admit that appellant is a

“good student” (53a), and has “a better than average

21

academic record at Iowa State” (49a, 55a), a “top flight

school” (Pi’s. Exh. 31, 123a). Nevertheless, the record

shows that the appellees have committed themselves to

what Judge Wisdom has called a program of “planned dis

couragement and discrimination by delay.” Meredith v.

Fair,----- - F. 2d----- (5th Cir. June 25, 1962).

The elements of this program are procedural circumven

tion, adherence to detailed eligibility requirements, and

reliance on delay inherent in judicial remedies, all intended

to conclude in appellant’s frustration or graduation prior

to the date when by court order, appellees are required

to open the facilities of Clemson College to all citizens of

South Carolina. The irreparable harm which appellant

suffers as a result of such delay is clear.

For this reason, the Fifth Circuit said in the Meredith

case, supra,

“ . . . time is of the essence. In an action for admission

to a graduate or undergraduate school, counsel for

all the litigants and trial judges too should be sensi

tive to the necessity for speedy justice. Lucy v. Adams,

N. D. Ala., 1955, 134 F. Supp. 235, aff’d. 228 F. 2d

619, cert. den. 351 U. S. 931; see also 350 U. S. 1, and

Hawkins v. Board of Control, 1956, 350 TJ. S. 413.

The court below relied on several cases which indicate

that the issuance of preliminary injunctions are within the

discretion of the district court and will be granted only

in rare circumstances (192a-195a). But the case here in

volves rights protected by the equal protection clause of

the Fourteenth Amendment, Such rights are “personal and

present”. Siueatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629, 635 (1950);

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U. S. 637, 642

(1950). Cf. Sipuel v. Board of Regents, 332 U. S. 631

(1948).

22

Moreover, this Court has recently held that there may he

no delay in granting access to governmentally owned public

facilities, even before a trial on the merits, where the right

to relief is clearly established on motion for preliminary

injunction. Henry v. Greenville Airport Commission, 284

F. 2d 631 (4th Cir. 1960). It was there held that the

trial court “has no discretion to deny relief by preliminary

injunction to a person who clearly establishes by undis

puted evidence that he is being denied a constitutional

right”.

Not only are appellant’s constitutional rights being de

nied, but unless the court below’s refusal to grant pre

liminary relief is reversed, he may have advanced too far

in his studies at Iowa State to make transfer practicable.

In such event, a final decision in his favor will not prevent

an irreparable injury to his constitutional rights. On the

other hand, if a preliminary injunction is granted, appellees

shall suffer no similar injury. The danger of irreparable

injury in desegregation cases has been recognized. Brown

v. Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U. S. 483 (1954);

Lucy v. Adams, 350 U. S. 1 (1955).

Here too, the public interest is involved, for there is

national concern and interest in the elimination of state-

enforced racial segregation, generally, Hurd v. Hodge, 334

U. S. 24 (1948), and particularly in education. Brown v.

Board of Education of Topeka, 347 U. S. 483 (1954);

Hawkins v. Board of Control, 347 U. S. 971; 350 U. S. 413;

355 U. S. 839.

Finally, there is strong likelihood that appellant will

prevail when this case reaches final hearing. Holmes v.

Danner, supra, Lucy v. Adams, supra, Meredith v. Fair,

supra.

23

In view of all of these factors, appellant submits that

this Court’s ruling in Henry v. Greenville Airport Commis

sion, supra, is applicable here, and should be followed.

CONCLUSION

It is respectfully submitted that the judgment of the

court below should be reversed and the case remanded

with directions that the appellant be granted the relief

sought and such other and further relief as may be just.

Respectfully submitted,

Constance B aker Motley

J ack Greenberg

10 Columbus Circle

New York 19, New York

Matthew J. P erry

L incoln C. J enkins, J r.

1107% Washington Street

Columbia, South Carolina

D onald J ames S ampson

W illie T. S mith, J r.

125% Falls Street

Greenville, South Carolina

Attorneys for Appellant

D errick B ell

Of Counsel

3 8