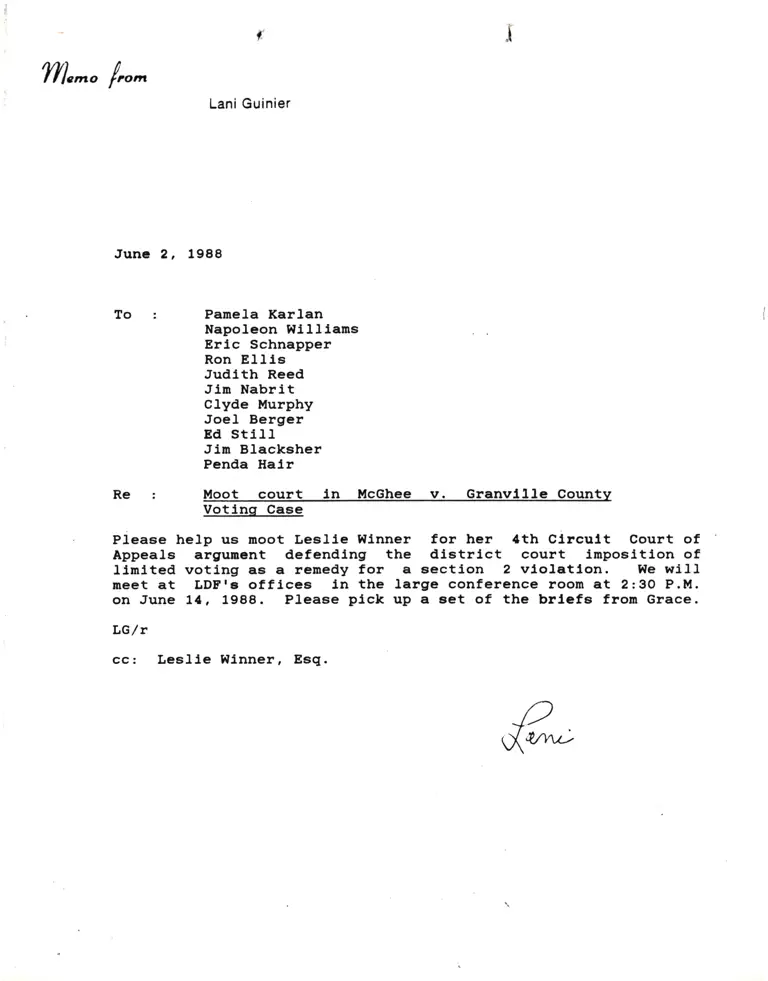

Correspondence from Lani Guinier to Karlan, Williams, Schnapper, Ellis, Reed, Nabrit, Murphy, Berger, Still, Blacksher, and Hair Re Moot Court in McGhee v. Granville County Voting Case

Correspondence

June 2, 1988

Cite this item

-

Legal Department General, Lani Guinier Correspondence. Correspondence from Lani Guinier to Karlan, Williams, Schnapper, Ellis, Reed, Nabrit, Murphy, Berger, Still, Blacksher, and Hair Re Moot Court in McGhee v. Granville County Voting Case, 1988. ce810775-ec92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/bfdb7d9e-a2e9-41fb-a1c3-f96d204bdafe/correspondence-from-lani-guinier-to-karlan-williams-schnapper-ellis-reed-nabrit-murphy-berger-still-blacksher-and-hair-re-moot-court-in-mcghee-v-granville-county-voting-case. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

T/1"^o f,o^

Lani Guinier

Juna 2, 1988

To : Pamela Karlan

Napoleon Wllllans

Erlc Schnapper

Ron Bllle

Judlth Reed

Jln Nabrlt

Clyde Murphy

JoeI Bergcr

Ed stlll

Jln Blackaher

Penda Hair

Re : Moot court ln McGhee v. GranvMe Countv

Votlnq Caee

Pieaee help ue moot Leel.le gflnner for her 4th Circult Court of

Appeals arguncnt defendlng the dlstrlct court lnposltlon of

Llnlted votlng aa a renedy for a eectlon 2 vlolatlon. We will

neet at LDF'c offlcea ln the large conference room at 2:3O P.M.

on June 11, 1988. Pleaee plck up a eet of the brlefs fron Grace.

LG/r

cc: Leelle Wlnner, Eeq.