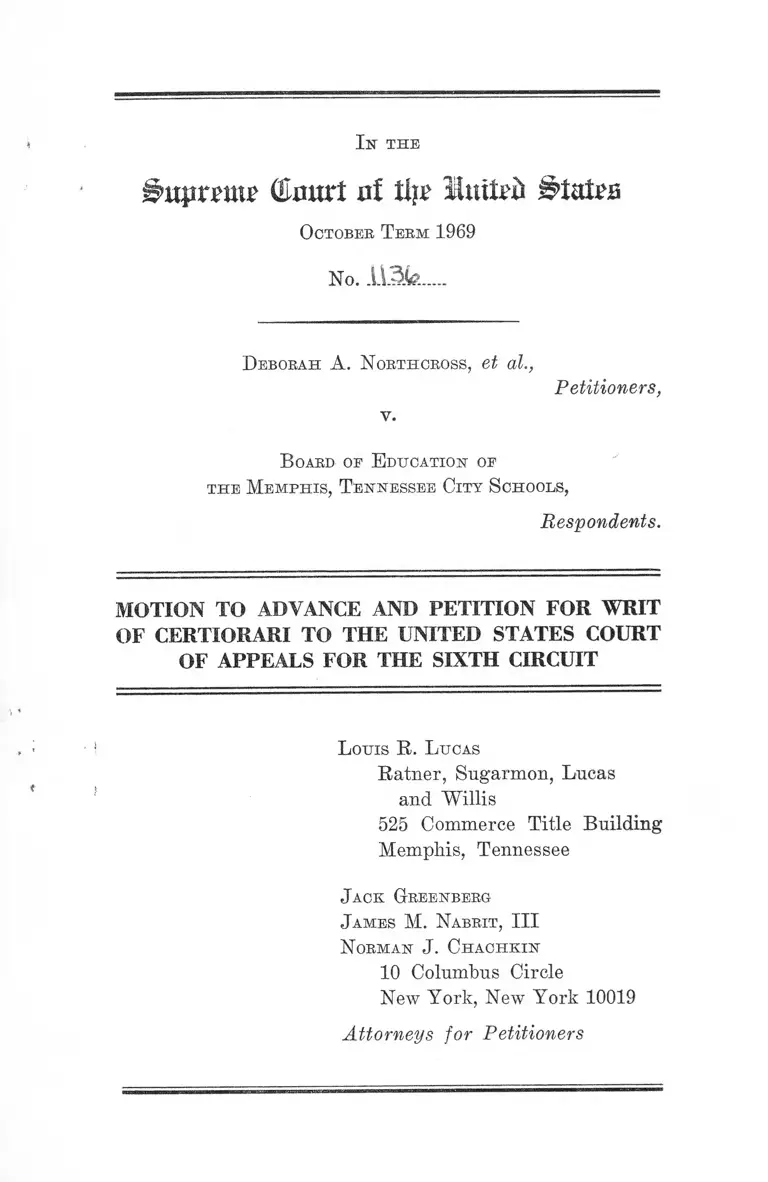

Northcross v. Memphis City Schools Board of Education Motion to Advance and Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1969

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Northcross v. Memphis City Schools Board of Education Motion to Advance and Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit, 1969. 59c5b3de-bf9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/bfdd6a5c-6d0c-45f1-83d0-2b59e16e6575/northcross-v-memphis-city-schools-board-of-education-motion-to-advance-and-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-us-court-of-appeals-for-the-sixth-circuit. Accessed February 25, 2026.

Copied!

I n th e

Shipmur (Emtrf of tip? iluitni ^taf^a

O ctober T erm 1969

No. \.\3k....

D eborah A. N orthcross, et at.,

v.

Petitioners,

B oard of E ducation of

th e M e m p h is , T ennessee Cit y S chools,

Respondents.

MOTION TO ADVANCE AND PETITION FOR WRIT

OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT

OF APPEALS FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

L ouis R . L ucas

Ratner, Sugarmon, Lucas

and Willis

525 Commerce Title Building

Memphis, Tennessee

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. N abrit , III

N orman J. C h a o h k in

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Petitioners

I N D E X

PAGE

Opinions B elow .................................................................... 1

Jurisdiction ............................................................. 2

Questions Presented ......................... 2

Constitutional Provision Involved................................... 2

Statement .............................................................................. 3

History of the Litigation .......................................... 3

The Memphis School System ................................... 4

The District Court Ruling ....................................... 5

The Rulings of the Court of Appeals ................... 8

R easons foe G ran tin g th e W rit :—

I. The Failure of the Court of Appeals to Require

any Action to Eliminate the Dual School System

During the Current School Tear Conflicts With

This Court’s Requirement in Alexander and Carter

That Every School District Terminate Dual School

Systems at Once and Operate Now and Hereafter

Only Unitary Schools ................................................ 12

A. The Decision of the Court of Appeals Re

manding the Case to the District Court With

the Specific Direction That There Was No

Need for Precipitous Action Conflicts With

This Court’s Decision in Alexander and Carter 12

XI

B. The Conflict Between the Decision of the Sixth

Circuit and Decisions of the Fourth, Fifth and

Eighth Circuits Implementing Alexander Man

dates Review by This Court ............................... 14

II. The Court of Appeals’ January 19, 1970 Ruling

That Memphis Now Operates a Unitary School

System Directly Contradicts the Findings of the

District Court and Conflicts With the Decisions of

This Court From Brown to Carter ....................... 16

C onclusion ......................................... 23

A ppendix

Court of Appeals’ December 19, 1969 Order ......... la

Court of Appeals’ January 12, 1970 Order ........... 5a

District Court’s May 15, 1969 Opinion ................... 9a

1969-70 Enrollment Statistics .................................... 24a

Motion to Require Adoption of Unitary System

Now ............................................................................. 32a

Motion to Convene Emergency P anel...................... 36a

En Banc Fourth Circuit Decision ............................ 39a

PAGE

I l l

T able oe A uthorities

page

Cases:

Alexander v. Holmes County Bd. of Educ., 396 U.S. 19

(1969) .......................................................... 2,8,10,12,13,14,

15,16, 20, 22, 23

Anthony v. Marshall County Bd. of Edue., 409 F.2d

1287 (5th Cir. 1969) ....................................................... 4

Brown v. Board of Edue., 347 U.S. 483 (1954); 349

U.S. 294 (1955) .......................... -.........................2,16, 22, 23

Carter v. West Feliciana Parish School Bd., No. 944

O.T. 1969 (January 14, 1970) ...... .......... ..... 2, 4,12,13,14,

15,16, 20, 22

Christian v. Board of Educ. of Strong School Dist. No.

83, 8th Cir. No. 20,038 (December 8, 1969) ....... ....... 15

Goss v. Board of Educ. of Knoxville, 373 U.S. 683

(1963) ....... ....................... -...........................................----- 3

Goss v. Board of Educ. of Knoxville, 406 F.2d 1183

(6th Cir. 1969) .......................................-.................. -.... 22

Green v. County School Bd. of New Kent County, 391

U.S. 430 (1968) ...........................-.................... 2, 4,13,17, 22

Henry v. Clarksdale Municipal Separate School Dist.,

409 F.2d 682 (5th Cir.), cert, denied, 396 U.S. 940

(1969) ................................................................................ 7

Jackson v. Marvell School Dist. No. 22, 416 F.2d 380

(8th Cir. 1969) ............... 17

Monroe v. Board of Comm’rs of Jackson, 391 U.S. 450:

(1968) ....... 4,19

IV

Nesbit v. Statesville City Bd. of Educ., 4th Cir. No.

13,292 (December 2, 1969) (en banc) ......... ............. 13,14

Northeross v. Board of Educ., 302 F.2d 818 (6th Cir.),

cert, denied, 370 U.S. 944 (1962) ................................... 3, 5

Northeross v. Board of Educ., 333 F.2d 661 (6th Cir.

1964) .............................................................. ................... 3,5

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School Dist.,

5th Cir. No. 26285 (December 1, 1969), rev’d sub

nom. Carter v. West Feliciana Parish School Bd.,

No. 944 O.T. 1969 (January 14, 1970) ....................... 16

Stanley v. Darlington County School Dist., 4th Cir. No.

13,904 (January 19, 1970) .............................................. 14

Watson v. City of Memphis, 373 U.S. 526 (1963) ........... 22

PAGE

Statutes:

28 U.S.C. §1343

42 U.S.C. §1983

3

3

I n th e

imtiunm (Emtrt of % Ituteft Stairs

O ctober T erm 1969

No.................

D eborah A. N orthcross, et al.,

v.

Petitioners,

B oard of E ducation op

th e M em ph is , T ennessee Cit y S chools,

Respondents.

MOTION TO ADVANCE

Petitioners, by their undersigned counsel, respectfully

move that the Court advance its consideration and disposi

tion of this case, which presents issues of national im

portance about which the court below and other United

States Courts of Appeals are divided in their interpretation

of Alexander v. Holmes County Bd. of Educ., 396 U.S. 19

(1969) and Carter v. West Feliciana Parish School Bd., No.

944 O.T. 1969 (January 14, 1970). These issues require

prompt resolution by this Court for the reasons stated in

the annexed Petition for Writ of Certiorari.

W herefore, petitioners pray that the Court:

1. Consider this motion immediately;

2

2. shorten the time for filing respondents’ response to

the annexed petition and

3. consider the annexed petition at the Court’s conference

of February 20, 1970.

Respectfully submitted,

Louis R. L ucas

Ratner, Sugarmon, Lucas

and Willis

525 Commerce Title Building

Memphis, Tennessee

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. N abrit , III

N orman J . C h a c h k in

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Petitioners

I n t h e

npwmv (Emtrt nf tip Hutted States

Octobee T eem 1969

No.

D eborah A. N orthcross, et al.,

v.

Petitioners,

B oard of E ducation of

th e M e m ph is , T ennessee Cit y S chools,

Respondents.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF

APPEALS FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

Petitioners pray that a writ of certiorari issue to review

the judgment of the United States Court of Appeals for the

Sixth Circuit entered in this case on December 19, 1969.

Opinions Below

The orders of the United States Court of Appeals for

the Sixth Circuit remanding the cause to the district court

and denying petitioners’ Motion for Injunction Pending

Certiorari, o f which review is sought, are unreported and

are reproduced in the Appendix, infra at pp.la-8a. The

opinion of the United States District Court for the Western

District of Tennessee is unreported and is also reproduced

in the Appendix, infra at pp. 9a-23a.

2

Prior reported opinions in this matter are found at 302

F.2d 818 (6th Cir.), cert, denied, 370 U.S. 944 (1962) and 333

F.2d 661 (6th Cir. 1964).

Jurisdiction

Jurisdiction of this Court is invoked pursuant to 28

U.S.C. §1254(1). The judgment of the Court of Appeals

was entered December 19, 1969 (infra at 4a).

Questions Presented

1. In light of the decisions of this Court in Alexander

v. Holmes County Bd. of Educ., 396 U.S. 19 (1969) and

Carter v. West Feliciana Parish School Bd., No. 944 O.T.

1969 (January 14, 1970), did the Sixth Circuit err in failing

to require prompt action during the current school year to

eliminate the dual school system! 2

2. Did the Sixth Circuit err in determining that the

Memphis system, in which 93% of the Negro pupils still at

tend racially identifiable schools (all-Negro or enrolling

90% or more Negro pupils), was a unitary school system

meeting the requirements of this Court’s decisions in Brown

v. Board of Educ., 347 U.S. 483 (1954); 349 U.S. 294 (1955);

Green v. County School Bd. of New Kent County, 391 U.S.

430 (1968); Alexander and Carterf

Constitutional Provision Involved

This case involves the Equal Protection Clause of Section

1 of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States.

3

Statement

History of the Litigation

Suit was originally filed under 28 U.S.C. §1343 and 42

U.S.C. §1983 to desegregate the Memphis City schools on

March 31, 1960; the district court denied injunctive relief

and upheld the Tennessee Pupil Assignment Law. On ap

peal, the Sixth Circuit reversed, with instructions to the

district court “ to restrain the defendants from operating a

biracial school system in Memphis, or in the alternative to

adopt a plan looking towards the reorganization of the

schools in accordance with the Constitution of the United

States.” Northcross v. Board of Educ. of Memphis, 302

F.2d 818, 824 (6th Cir.), cert, denied, 370 U.S. 944 (1962).

On remand, the school district submitted, and the district

court approved, a stair-step1 2 plan incorporating geographic

zoning and minority-to-majority transfers.2 On appeal, the

Sixth Circuit invalidated the minority-to-majority transfer

feature and directed close scrutiny of all zone lines because

it found substantial evidence that the boundaries approved

by the district court had been “gerrymandered to preserve

a maximum amount of segregation.” Northcross v. Board

of Educ. of Memphis, 333 F.2d 661, 663 (1964).

May 13,1966, petitioners filed a Motion for Further Relief

seeking the adoption of a new desegregation plan. A modi

fied plan incorporating minimal zone changes3 and unre

stricted transfers was submitted by the respondents July 26

1 The original plan of desegregation affected grades 1-3 for the

school year beginning September, 1962. Grade 4 was to be deseg

regated during the 1963-64 school year and one additional grade

per year thereafter. The Sixth Circuit ordered the pace accelerated

to desegregate junior high school grades in September, 1965 and

senior high schools in the fall of 1966. 333 F.2d at 665.

2 See Ooss v. Board of Educ. of Knoxville, 373 U.S. 683 (1963).

8 On May 15, 1969, the district court ruled that these same zones

“are in need of revision for many purposes including further de

segregation where feasible.” (Infra p. 18a).

4

and approved by the district court without hearing July 29,

1966. The court made no ruling upon petitioners’ Motion for

Further Relief. A second Motion for Further Relief, based

in part upon Green v. County School Bd. of New Kent

County, 391 U.S. 430 (1968), was filed July 26, 1968, seeking

(1) cancellation of all transfers which reduce desegregation

in the school system,4 * (2) complete faculty desegregation,

(3) a survey of the location of facilities, pupils, etc. with

a complete report thereon submitted to the district court,

(4) adoption of a new plan of desegregaton, prepared with

the assistance of the Title IY Desegregation Center of the

University of Tennessee, and based on unitary geographic

zones, consolidation of schools or pairing, but without an

unrestricted free transfer. The present proceedings arise

from an appeal of the district court’s May 23, 1969 ruling

on the Green motion.

The Memphis School System

The Memphis school district lies but four miles north of

the Mississippi state line in Shelby County, Tennessee.6

The district operates some 149 schools; 92 of those schools

are more than 90% white or 90% Negro:

4 Compare Monroe v. Board of Comm’rs of Jackson, 391 U.S. 450

(1968). Under the Memphis free transfer provision during the

1968-69 school year, 378 white students transferred from desegre

gated schools to all-white or heavily white schools; 563 white stu

dents transferred from all-Negro or predominantly Negro schools to

all white or heavily white schools; and 526 Negro students trans

ferred from predominantly white desegregated schools to predom

inantly Negro or all-Negro schools. (See Transfer Report for 1968-

69, filed by respondents August 14, 1968).

6 Shelby County is contiguous with Marshall County, Mississippi,

where this Court on January 14, 1970 ordered complete desegrega

tion of pupils and faculty no later than February 1, 1970. Carter

v. West Feliciana Parish School Bd., No. 944, O.T. 1969. In 1968-69

in Holly Springs (Marshall County), Mississippi, 3.2% of that dis

trict’s Negro pupils attended predominantly white schools. An

thony v. Marshall County Bd. of Educ., 409 F.2d 1287, 1288 (5th

Cir. 1969). The comparable percentage in Memphis during 1968-

69 was 2.7%. See text infra.

5

[A ]s of the current school year, 1968-69, there are

presently thirty-five [35] all-white schools, fifty [50]

all-Negro schools, forty-seven [47] predominantly

white schools and seventeen [17] predominantly Negro

schools.6

{Infra, p. 10a). Of the 66,555 Negro pupils in the system

at the time of the February, 1969 hearing on the Green

motion, only 1,842 (.or 2.7 %) attended schools where white

students predominated; only 1,258 (2.2%) of Memphis’

57,707 white students attended predominantly Negro schools

(Trial Exhibit No. 27, reprinted in the Appendix to the

Motion for Summary Reversal). Statistics filed by respond

ents with the Sixth Circuit prior to the oral argument (infra

at pp. 24a-31a) show little change during 1969-70. Of

70,925 Negro students in elementary, junior high and high

schools, only 2,601 (3.5%) attend predominantly white

schools; 49,821 (70.2%) attend all-Negro schools; and 65,967

(93%) attend schools which are more than 90% Negro.

Meanwhile, the number of white students attending pre

dominantly Negro schools has declined to 859 (1.4%) of

the total 60,005 white students.

The District Court Ruling

Following the filing of the Green Motion July 26, 1968,

the district court on August 23, 1968 declined to order any

relief for the 1968-69 school year because of the imminent

reopening of school.7 No hearing on the motion was sehed-

6 In 1960 there were 79, as compared with the present 72 all-

white or predominantly white schools; and 44, as compared with

the present 50 all-Negro and 17 predominantly Negro schools,

in the Memphis system. Northcross v. Board of Educ. of Memphis,

302 F.2d 818, 820 (6th Cir. 1962).

7 The district court deferred ordering the facilities and pupil

surveys requested in the Motion for Further Relief pending receipt

of briefs from respondents in support of their argument that Green

was inapplicable. Hearings were held November 8 and 11, 1968

6

uled until after the survey report (see note 7) was filed by

respondents on December 23, 1968. Thereafter, bearings

were held from February 6-11, 1969; the district court’s

opinion rendered May 15, 1969, and a formal order entered

May 23, 1969.

The district court held that “ the existing and proposed

plans do not have real prospects for dismantling the state-

imposed dual system at the ‘earliest practicable date’.”

(Infra, p. 18a). Nevertheless, the district court declined

to void the free transfer system, even though respondents

frankly admitted that they wished to retain free transfers

to permit students to avoid integration if they wished to do

so.* 8 The court continued, “ [t]he zones are in need of revi

to determine whether respondents should be required to make the

surveys. On November 21, 1968, the district court ordered the

studies to be undertaken and a report thereon filed within 45 days.

8 See the Memorandum of Points and Authorities submitted by

respondents to the district court and reprinted in the Appendix

to petitioners’ Motion for Summary Reversal. Trial Exhibit 6,

also reprinted in that Appendix, demonstrates that this is exactly

how the free transfers work. The following table depicts some

examples:

Whites Attend-

Whites Living ing School

Zone in Zone in Zone

Getwell Elementary ................ ...... - ....... 47 0

Gordon Elementary ................ 130 33

Grant Elementary .................. ................ 51 0

Rozelle Elementary ................ ................ 217 98

Springdale Elementary .......... ................ 93 7

Vollentine Elementary .......... ................ 275 195

Corry Junior H igh .................. .... - ....... . 19 0

Humes Junior H igh ................ ...... - ....... 289 193

Riverview Junior High .......... ................ 36 0

Northside High ........................ 124 63

Melrose High .......................... ... -........... 47 0

Negroes

Negroes Attending

Living School

in Zone in Zone

Cherokee Elementary.............. ................ 274 151

(All students not attending school within their zones attend other

Memphis public schools). (E.g., Tr. 408)

7

sion for many purposes, including further desegregation

where feasible” (infra, at p. 18a).9 Revised zone boundary

9 In 1964 the Court of Appeals pointed out two “obvious” ex

amples of zones “gerrymandered to preserve a maximum amount of

segregation” : Klondike [Negro] and Yollentine [white] elementary

school zones (which have a mutual boundary). Norther oss v. Board

of Educ. of Memphis, 333 F.2d at 663 (1964). Since that time no

changes have been made in the zones (Tr. 374) and no white stu

dents attend the Klondike school.

Most zone boundaries between identifiably white and Negro school

zones correspond directly to the racial distribution of the city’s

population (school boundary lines drawn by respondents follow

historic boundary lines between white and Negro neighborhoods

without regard to natural boundaries, capacities of schools, or any

other criteria except race). (Tr. 40 et seq.) Cf. Henry v. Clarks-

dale Municipal Separate School Dist., 409 F.2d 682, 687 (5th Cir.),

cert, denied, 396 U.S. 940 (1969). (See Trial exhibits 7, 8, 9, 15,

16, 17 and 18). Examples are as numerous as they are flagrant.

For example, the Central High School zone [89% white] is

bounded as follows: on the south by Hamilton [all-Negro] and

Melrose [all-Negro] ; on the west by Washington [all-Negro] and

Northside [95% Negro]; on the north by Douglass [all-Negro];

and on the east by Lester [all-Negro]. The Central zone lines have

no rational basis other than race. The zone is bisected by the fol

lowing “natural” obstacles—in the north by the L & N railroad

tracks and also by North Parkway, a major thoroughfare; in the

south by the Union Pacific and L & N railroad tracks; in the west

by Interstate Highway 255; and in the east by East Parkway, a

major thoroughfare.

Another example is the Messick High School zone [99% white]

which is bounded on the west by the Melrose High School zone

[all-Negro]. The boundary separating these two zones is an irra

tional and jagged line which follows exactly the easternmost edge

of a Negro neighborhood.

The elementary and junior high maps are also replete with simi

lar examples of racial gerrymandering. The district court opinion

(infra at p. 15a) notes “some glaring islands” :

For example, Carpenter Elementary, grades 1-3, and Lester

Elementary, Junior High and High Schools have a total of

2396 students, all Negro. Treadwell and East High Schools

have grades 1 through 12 and are immediately adjacent to the

Lester-Carpenter zone. Treadwell has 2884 whites and 8 Ne

groes. East has 1866 white students and 19 Negroes. The

defendants point out that the Lester-Carpenter “ island” zone

boundaries are necessary because of industrial and commercial

8

lines together with enrollment projections were to he filed

January 1, 1970. The district court denied petitioners’

prayer for an injunction restraining any further school

construction until new zone lines were formulated and

approved, and required only a 20% system-wide assignment

of faculty across racial lines for 1969-70.

The Rulings of the Court of Appeals

June 13, 1968, petitioners filed with the United States

Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit, a Motion for Sum

mary Reversal of the district court’s judgment. June 18,

1968, the Court of Appeals declined to consider the motion

until the complete transcript of testimony was filed. The

court reporter thereafter advised the Court of Appeals,

upon instruction of the district judge and at the request

of petitioners’ counsel, that the transcript could not be pre

pared until September. A second motion renewing peti

tioners’ request that the Court of Appeals proceed on the

basis of the printed Appendix supplied with the motion

and the exhibits forwarded from the district court was like

wise denied by the Court of Appeals, although a major

ground relied upon for summary reversal was the district

court’s failure to require new zone lines to be effectuated

for 1969-70 after finding in May, 1969 that “ the existing

and proposed plans do not have real prospects for dismant

ling the state-imposed dual system at the ‘earliest practi

cable date’ ” (infra at p. 18a).

Following this Court’s decision in Alexander v. Holmes

County Bd. of Educ., 396 U.S. 19 (1969), petitioners filed

with the Court of Appeals on November 3, 1969, a Motion

to Require Adoption of a Unitary System Now (reprinted

barriers, major thoroughfares and railroad tracks. The plain

tiffs point out that these same tracks bisect other zones in other

parts of the city.

9

at pp. 32a-35a infra). November 13, 1969, petitioners

filed a Motion to Convene an Emergency Panel of the Sixth

Circuit (reprinted at pp. 36a-38a infra) to hear and deter

mine the Alexander motion. The following day, the tran

script was received by the Court of Appeals; the convening

of an emergency panel was denied and the Alexander motion

passed for consideration by the regular panel of the Court

which would hear the appeal, which was then calendared

for argument December 17, 1969.

Following oral argument, the judgment of the Court of

Appeals was issued December 19, 1969, remanding the case

to the district court for further consideration of the Motion

for Further Relief and the “plan” 10 or any amendment

thereto to be presented to the district court as required by

its order of May 23,1969:

It appears to this Court that the imminence of the

presentation and consideration by the District Judge of

the proposed plan to be submitted on or before January

1, 1970, suggests the impracticality of this Court at

tempting to consider precipitously the various claims

asserted by plaintiffs-appellants in their appeal, and

motions. This Court has been familiar with the prob

lems of desegregation in the schools of the City of Mem

phis since 1962, when it had before it the first judgment

commanding desegregation, entered by the District

Court on May 2, 1961. From review of this litigation

and its underlying factual situation, it is satisfied that

there is no need at this time for precititous [sic] action.

Therefore, no further order need be entered in this

Court until the United States District Court has had

10 The district court did not require submission of a new plan,

but merely revised zone boundary lines together with enrollment

projections. It further did not call for any changes to be made

until the 1970-71 school year.

10

submitted to it the ordered plan, and has had oppor

tunity to consider and act upon it. {Infra, p. 3a)

(emphasis supplied).

Petitioners then filed a Motion for Injunction Pending

Certiorari, praying that the Court of Appeals, pursuant to

Alexander and to the December 13,1969 order of this Court

granting temporary relief in Carter, direct the district court

to implement changes during the second semester of the

current school year. January 12,1970, the Court of Appeals

denied the Motion for Injunction:

Appellants support their motion with citation of au

thorities which they assert require the action they ask

us to take, viz: Alexander v. Holmes [County] Board

of Education, 398 U.S. 19; Carter v. West Feliciana

Parish School Board No. 944, — —• U .S.------, December

13, 1969, 38 U.S.L. Week 3220; Singleton v. Jackson

Municipal Separate School District, ------ F (2) -——

(5th Cir. 1969, No. 26,285); Nesbit v. The Statesville

City Board of Education, ■—-—■ F(2) —— (4th Cir. 1969,

No. 13,229).

To the extent that the relevant factual context of the

above cases is disclosed by the opinions available to us,

we conclude that they are not analogous to the case

before us. We are satisfied that the respondent Board

of Education of Memphis is not now operating a “ dual

school system” and has, subject to complying with the

present commands of the District Judge, converted its

pre-Brown dual system into a unitary system “within

11

which no person is to he effectively excluded because

of race or color.” (Infra at pp. 6a-7a),u

11 Compare the findings of fact made by the district judge (infra

at p. 18a) :

In this cause the Court finds that the defendant Board has

acted in good faith as it interpreted its burden to desegregate

the schools in its system. However, the existing and proposed

plans do not have real prospects for dismantling the state-

imposed dual system at the “earliest practicable date.”

In dismantling the former state-imposed dual system at the

earliest practicable date the Board should undertake to remove

racial discrimination in all schools, not just the schools in the

inner city.

The zones are in need of revision for many purposes including

further desegregation where feasible.

12

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

I.

The Failure of the Court of Appeals to Require any

Action to Eliminate the Dual School System During the

Current School Year Conflicts With This Court’ s Re

quirement in Alexander and Carter That Every School

District Terminate Dual School Systems at Once and

Operate Now and Hereafter Only Unitary Schools.

A. The Decision of the Court of Appeals Remanding

the Case to the District Court With the Specific

Direction That There Was No Need for Precipitous

Action Conflicts With This Court’s Decision in

Alexander and Carter.

In Alexander and Carter this Court refused to permit

delays in the complete conversion of school districts in

Mississippi, Alabama, Georgia, Florida and Louisiana into

unitary systems. One of the cases included in the Carter

decision involved Marshall County, Mississippi, which ad

joins the county in which the Memphis school system is

located. As in Alexander, “ the question presented is one

of paramount importance involving as it does the denial

of fundamental rights to many thousands of school children

who are presently attending [Memphis, Tennessee] schools

under segregated conditions contrary to the applicable

decisions of this Court. . . .” But by accident of geography,

this case falls within the jurisdiction of the Sixth. Circuit

Court of Appeals.

The rule in the Sixth Circuit for Memphis is “go slow.”

The district court is told he should not act “precipitously”

in deciding the case. The rule is stated in the face of this

Court’s most recent decisions. The practice is far worse.

13

The Green motion filed in Jnne of 1968 was not decided

by the district court for almost a year and the denial by

the Sixth Circuit of a hearing in a manner permitted by

Rule 30(f) of the Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure

for an additional six months makes a mockery out of the

grant of Constitutional rights to Negro children. In Green

v. County School Board, 391 U.S. 430 (1968) this Court

spoke of such delay.

Such delays are no longer tolerable, for “ the govern

ing constitutional principles no longer bear the imprint

of newly enunciated doctrine.” Watson v. City of

Memphis, 373 U.S. 527 at 529.

The Sixth Circuit in its December 19, 1969 order made

no mention of this Court’s decision in Alexander, supra,

despite petitioners’ Alexander motion and their Reply

Brief, which also fully discussed this Court’s December

13, 1969 order in Carter v. West Feliciana Parish School

Bd. and the ruling of the Fourth Circuit in Nesbit v. States

ville City Bd. of Educ., No. 13,292 (December 2, 1969)

(en banc).

If the practice and procedure followed in this cause is

considered in the context of the Sixth Circuit’s decision

that there should be no precipitous action, it will put the

district court below and all other district courts in the

Sixth Circuit in the impossible situation of choosing be

tween (1) the clear and precise decisions from this Court

establishing the pendente lite relief principle for school

desegregation cases and requiring that such cases proceed

on an expedited basis in all courts without formalistic

and technical delays which have the effect, as here, of a

denial of relief, and (2) the subsequent decision of the

Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals to the opposite effect. This

is a case where there is no dispute that segregation was a

14

requirement of Tennessee state law and where the school

district in question is less than four miles from another

school district (Marshall County, Mississippi) in which

this Court on January 14, 1970 ordered an end to all delay

and the full desegregation of faculty and pupils no later

than February 1, 1970.

B. The Conflict Between the Decision of the Sixth Circuit

and Decisions of the Fourth, Fifth and Eighth Circuits

Implementing Alexander Mandates Review by This

Court.

On December 2,1969 the Court of Appeals for the Fourth

Circuit, sitting en banc, unanimously arrived at an inter

pretation of this Court’s decision in Alexander which con

flicts squarely with the interpretation and actions of the

Court below. In Nesbit v. Statesville City Bd. of Educ.,

No. 13,292 (December 2, 1969), the Fourth Circuit ordered

school districts to submit unitary plans by December 8,

1969 for complete implementation no later than January

31, 1970.

The clear mandate of the [Supreme] Court is im

mediacy. Further delays will not be tolerated in this

Circuit. [Slip opinion at p. 2].

On January 19, 1970, that Circuit in Stanley v. Darling

ton County School Dist., No. 13,904, reaffirmed its Nesbit

holding and, citing this Court’s January 14, 1970 holding

in Carter, said:

These decisions leave us with no discretion to con

sider delays in pupil integregation until September

1970. Whatever the state of progress in a particular

school district and whatever the disruption which will

be occasioned by the immediate reassignment of teach

ers and pupils in mid-year, there remains no judicial

discretion to postpone immediate implementation of

15

the constitutional principles as announced in Green v.

County School Bd. of New Kent County, 391 U.S. 430;

Alexander v. Holmes County Bd. of Educ., 396 U.S. 19

(Oct. 19,1969); Carter v. West Feliciana Parish School

Bd. -------U.S. ------- (Jan. 14, 1970).12

The Fifth Circuit on January 21, 1970 entered a brief

Order following reversal by this Court in Carter, adopting

the January 14, 1970 opinion of this Court as its opinion

on remand.

The Eighth Circuit in Christian v. Board of Educ. of

Strong School Hist. No. 83, No. 20,038 (December 8, 1969),

applied the Alexander rule in granting summary reversal

and ordering the school district to file a plan by January 7,

1970 for complete desegregation at the beginning of the

second semester of the current school year.

While the conflict between the decisions of this Court

and the Sixth Circuit Court of Appeals provides a com

pelling case for action by this Court, the added and tradi

tional ground of conflicting decisions among Courts of

Appeals takes on dramatic importance here because of the

nature of the constitutional rights involved and the proxi

mity of school districts operating under exactly opposite

determinations of the constitutional requirements.13 A

Negro child in Marshall County, Mississippi is granted

his constitutional rights by order of this Court, while a

Negro child across the county (and State) line a few miles

away is denied these rights by the decision of a Court

of Appeals. In view of the possible effect on all school

districts, and in particular those within the Sixth Circuit,

this Court cannot allow such different treatment to go

uncorrected.

12 The entire order is reprinted infra at pp. 39a-42a.

18 See Rule 19(1) (b) of the Rules of this Court.

16

In Brown v. Board of Educ., 349 U.S. 294, 300 (1955),

this Court enunciated a standard of action at “ the earliest

practicable date.” Subsequent to Alexander, the Fifth

Circuit in its Singleton en banc opinion delayed pupil in

tegration until September, 1970 based upon a standard of

“ the earliest feasible date.” Although this Court made

clear in Carter that the rule must be Alexander’s—“ at once”

and “now and hereafter”—the one year delay in the district

court, the six month delay in the Court of Appeals, and

the December 19, 1969 order establish a Sixth Circuit

standard of “no precipitous action” which if unreversed

renders Alexander and Carter nugatory within this Circuit.

II.

The Court of Appeals’ January 19, 1970 Ruling That

Memphis Now Operates a Unitary School System Directly

Contradicts the Findings of the District Court and Con

flicts With the Decisions of This Court From Brown to

Carter.

On May 15, 1969, the district court found

that the defendant [Memphis] Board has acted in good

faith as it interpreted its burden to desegregate the

schools in its system. However, the existing and pro

posed plans do not have real prospects for dismantling

the state-imposed dual system at the “ earliest prac

ticable date.”

(Infra at p. 18a) (emphasis supplied). Throughout the

opinion, the district court characterizes Memphis as a

“ state-imposed dual system” which has not yet been dis

established, explicitly rejecting the claims of respondents

that complete compliance with constitutional commands

has been achieved:

17

The defendant has compiled graphs and charts which

indicate that 47,586 pupils within the system are at

tending schools with mixed racial enrollments. An

examination of the enrollment figures shows that in

some cases this includes a school wherein the ratio

will be 1 white to 1822 Negro pupils, as in the case

of Lincoln Junior High, and 1 Negro to 876 white

pupils, as in the case of Treadwell Junior High.

During the current year 71.5% of the Negroes attend

all Negro schools.

(Infra at p. 11a).. Petitioners’ expert witness noted, for

example, that nearly all Memphis high schools were either

attended exclusively by students of one race or had but

six or seven pupils of the minority race among total enroll

ments of 700 to 1000 pupils. The only exceptions were un

zoned Memphis Technical High, Central High and North-

side High, which was 4.8% white (Tr. 89-90).14 In 1968-69,

while 71.5% of Memphis’ Negro pupils were in all-black

schools, only 2.7% were in predominantly white schools,

and only 2.2% of the white pupils were in predominantly

Negro schools (Tr. 248).15 16

14 The district court opinion stated that “ [a]s of the current

school year, 1968-69, there are presently 35 all white schools, 50 all

Negro schools, 47 predominantly white schools and 17 predomi

nantly Negro schools.” (Infra at p. 10a).

16 The Superintendent decried this emphasis upon “statistics,”

and maintained that one student of a minority race among one

thousand of the majority race made a facility a desegregated school

(Tr. 340-42, 382). Compare Green v. County School Bd. of New

Kent County, supra; Jackson v. Marvell School Dist. No. 22, 416

F.2d 380, 384 (8th Cir. 1969) :

“ The admittance of 36 white students into a formerly all-Negro

school still attended by 660 Negroes cannot be said to have

the effect of casting off the school’s racially identifiable cloak.”

18

Other indicia of a continuing dual system were noted by

petitioners’ expert witness and xhe district court. From

a comparison of the racial breakdown of pupils residing

in adjacent zones, petitioners’ witness concluded that the

existing zone lines followed traditional boundaries between

Negro and white neighborhoods (Tr. 40 et seq.), and the

district court recognized the pattern:

For example, Carpenter Elementary, grades 1-3, and

Lester Elementary, Junior High and High Schools

have grades 1 through 12 and are immediately adjacent

to the Lester-Carpenter zone. Treadwell has 2884

whites and 8 Negroes. East has 1866 white students

and 19 Negroes. The defendants point out that the

Lester-Carpenter “island” zone boundaries are neces

sary because of industrial and commercial barriers,

major thoroughfares and railroad tracks. The plain

tiffs point out that these same tracks bisect other

zones in other parts of the city.

(Infra at p. 15a). As of January 17, 1969, only 441%

of the 5,000 teachers in the system were in minority assign

ments, and many of these were not regular classroom

teachers but those engaged in special programs (infra at

p. 16a).

The district court concluded that in fact Memphis was

not a unitary school system, and that further desegregation

was required (although that court rejected some of peti

tioners’ proposals to increase desegregation):

In dismantling the former state-imposed dual system

at the earliest practicable date the Board should under

take to remove racial discrimination in all schools, not

just the schools in the inner city. . . .

The zones are in need of revision for many purposes

including further desegregation where feasible. . . .

19

the Board should appoint a full time Director of Dese

gregation who shall be charged with investigating and

recommending to the Board ways and means of assist

ing the Board in its affirmative duty to convert to a

unitary system in which racial discrimination will be

eliminated root and branch. . . .

The defendant Board in this case shall adopt a plan

of faculty desegregation whereby supervisors, prin

cipals, teachers and other faculty personnel shall be

employed, promoted and assigned in furtherance of a

goal of removing the racial identity of each school,

but no teachers shall be discharged from the system

to correct a racial imbalance.

An interim target for this goal shall be that at least

20% of the teachers in the system will be assigned

to racially minority faculty positions in the year 1969-

70. This percentage shall be systemwide and shall not

necessarily require 20% in each school in 1969-70.16

(Infra at pp. 18a-22a).

Nevertheless, the Court of Appeals made no ruling on

petitioners’ claims that the district court should have voided

Memphis’ free transfer provision,17 required immediate re

16 No further faculty desegregation has yet been required by the

district court.

17 Petitioners’ expert witness noted the general pattern that in

zones with substantial Negro pupil resident population, the white

student enrollment in schools located in those zones was consider

ably less than the white pupil resident population. See n. 8 supra.

The district court declined to limit transfers to those which would

increase desegregation because it found the influence of the free

transfer provision upon the racial composition of the schools to

be equivocal. Petitioners argued below that the free transfer provi

sion facilitates avoidance of integration by students and parents

opposed to it. Compare Monroe v. Board of Comm’rs of Jackson,

391 U.S. 450 (1968).

20

drawing of zone lines,18 accelerated faculty desegregation

and adopted the suggestions of petitioners’ expert witness

for interim steps to substantially increase desegregation

in the Memphis school system.19 In response to petitioners’

argument20 that these things were required, and were re

quired now by the Alexander and Carter decisions, the

Sixth Circuit in its January 12, 1970 order held these de~

18 In 1964 the Sixth Circuit found substantial evidence that the

Klondike and Vollentine zones were “gerrymandered to preserve

a maximum amount of segregation,” required them redrawn and

all zones scrutinized for the same purpose. 333 F.2d at 664. No

change was made in the Klondike-Vollentine boundary (Tr. 374)

nor, generally, in any of the zone lines (Tr. 150, 224-25). The dis

trict court found rezoning necessary (infra at p. 18a) but delayed

requiring submission of new zone lines until January, 1970, setting

no date for implementation of new zone lines.

19 Petitioners’ expert witness suggested that a detailed study

carried out over some time would result in long-range plans to

increase desegregation in Memphis (Tr. 104-07) but that there were

a number of feasible interim alternatives which could have been

effectuated in the fall of 1969 (Tr. 98-104) to move towards the

goal of a completely unitary system: (1) redrawing of zone boun

dary lines at all levels (see also Tr. 49), (2) cancellation of the

open transfer policy, (3) institution of a majority-to-minority

transfer only, (4) suspension of all planned construction pending

restudy to determine consonance with desegregation, (5) increased

faculty desegregation—at least 30% in minority positions for

1969-70, (6) public relations programs to promote acceptance of

more than token desegregation, (7) assistance of the University of

Tennessee Title IV Center, and (8) pairings of schools to increase

desegregation (Tr. 61-65).

20 The Sixth Circuit refers in its order to the suggestion during

oral argument that one measure of whether a unitary school system

had been achieved was the degree to which each school has a pupil

population racially reflective of the total system pupil population:

We have expressed our own view that such a formula for racial

composition of all of today’s public schools is not required to

meet the requirement of a unitary system.

(Infra at p. 7a). This hardly compels the conclusion, however,

21

cisions “not analogous” because “ respondent Board of

Education of Memphis is not now operating a ‘dual school

system’ . . The genesis of this holding is difficult to

discern. On December 19, 1969, the Sixth Circuit had re

manded the case to the district court without impeaching

the lower court’s finding that there was still a dual school

system in Memphis, advising only that the facts did not, in

the Sixth Circuit’s view, call for “precipitous action.” Cer

tainly the 1969-70 enrollment statistics presented to the

Court of Appeals prior to its first ruling indicated no change

from 1968-69. In fact, they show (infra at pp. 24a-31a)

less desegregation than the previous year. 115,748, or

88.4% of Memphis’ 130,930 students in grades 1-12 attend

schools enrolling less than 10% students of the opposite

race. Only 2,601 (3.5%) of 70,925 Negro students, attend

predominantly white schools; 49,821 (70.2%) attend all-

Negro schools and 65,927 (93%) attend schools which are

more than 90% Negro. The number of white students at

tending predominantly Negro schools has declined to 859

(1.4% of 60,005 white pupils). Integration in Memphis is

still largely token: 55,037, or 88%, of the 68,091 students

whom respondents claim attend integrated schools attend

schools enrolling less than 10% students of the opposite

race. 82.8% of the white students and 76.5% of the Negro

students in what respondents term “ integrated” schools

attend classes with less than 10% students of the opposite

race.

These figures hardly call for “no precipitous action,” let

alone “no action at all.” Yet that is exactly the implication

that no further desegregation at all is required in Memphis.

Petitioners also argued below, as they do here, that 93% of all

Negro students attending Negro schools is a certain indicator that

a unitary school system has not been achieved.

22

of the holding below that Memphis has achieved a unitary

school system.21

Seven years ago this Court told the Negro citizens of

Memphis that

[t]he [constitutional] rights here asserted are, like all

such rights, present rights; they are not merely hopes

to some future enjoyment of some formalistic consti

tutional promise. The basic guarantees of our Consti

tution are warrants for the here and now and, unless

there is an overwhelmingly compelling reason, they

are to be promptly fulfilled. The second Brown deci

sion is but a narrowly drawn, and carefully limited,

qualification upon usual precepts o f constitutional ad

judication and is not to be unnecessarily expanded in

application.

Watson v. City of Memphis, 373 U.S. 526, 533 (1963) (em

phasis in original). Alexander and Carter decisively elimi

nated even that narrow and limited qualification. Yet if

the determination of the Sixth Circuit;—that a state-created

dual school system, is converted to a unitary system despite

assignment of 93% of its Negro students to schools which

are more than 90% Negro—is permitted to stand, the dis

trict court in this case and every other district court in this

Circuit will be entirely without guidance. The entire history

of school desegregation from Brown to Carter will have

been for naught in the Sixth Circuit. The ten years of liti

gation by petitioners seeking to enforce the constitutional

rights of Negro pupils in the City of Memphis will have

21 The Sixth Circuit has consistently been apart from other cir

cuits in its application of Green and other cases which state a re

quirement of affirmative action on the part of school boards to

eliminate all aspects of the dual system so that school shall no

longer be racially identifiable. See, e.g., Goss v. Board of Educ. of

Knoxville, 406 F.2d 1183 (6th Cir. 1969).

23

been an expensive exercise in futility, yet another example

of the law’s promise broken. The fundamental error below

as well as the fulfilment of the promise of Brown and of

Alexander require an order providing for effective proce

dures to insure action now to establish a unitary school

system in Memphis.

CONCLUSION

Petitioners respectfully pray that a writ of certiorari to

the United States Court of Appeals for the Sixth Circuit

be issued, that the judgment below be summarily reversed

with direction to require respondents to prepare, with the

assistance of HEW or the HEW-funded University of

Tennessee Title IV Center, a plan of complete pupil and

faculty integration affecting all phases of the operations

of the Memphis public school system to be implemented

during the 1969-70 school year immediately following the

order of this Court.

Respectfully submitted,

Louis R . L ucas

Ratner, Sugarmon, Lucas

and Willis

525 Commerce Title Building

Memphis, Tennessee

J ack G-reexberg

J ames M. N abrit , III

N orman J. Ch a c h k in

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Petitioners

APPENDIX

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

F ob th e S ix t h C ircuit

No. 19,993

Court of Appeals’ December 19, 1969 Order

D eborah A. N orthcross, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants

v.

B oard of E ducation of the Memphis,

Tennessee, City Schools,

Defendants-Appellees.

Order

Before W rick and Celebrezze, Circuit Judges, and

O ’S u llivan , Senior Circuit Judge.

T his cause is before this Court upon the appeal of plain-

tiffs-appellants from an order and judgment of the United

States District Court for the Western District of Tennes

see, Western Division, and upon motions of plaintiffs-

appellants denominated Motion for Summary Reversal

and Motion to Require Adoption of Unitary System Now.

These Motions requested us to hear the appeal and said

motions without waiting the filing in this Court of a full

transcript of the proceedings underlying the order from

which the appeal is taken. However, this Court, on its own

motion, advanced the hearing of the cause and it was sub

mitted to a panel of this Court on December 17, 1969, upon

briefs, oral argument and a partial transcript.

la

2a

This case has been before us previously on two occasions.

In NortJicross v. Board of Ed. of City of Memphis, 302

F(2) 818 (6th Cir. 1962), cert, denied, 370 U.S. 944, we

held that the Tennessee Pupil Assignment Law was in

effective as a desegregation plan and restrained the Board

from operating a bi-racial school system in Memphis, or

in the alternative to adopt a plan looking toward the re

organization of the schools and to retain jurisdiction.

Upon the remand, the District Court ordered desegrega

tion of the Memphis Schools in accordance with a plan of

desegregation. On appeal, we held the transfer provision

of the plan invalid, and required the Board to justify all

existing zone lines. Northcross v. Board of Ed. of City

of Memphis, 333 F (2) 661 (6th Cir. 1964). Subsequent

thereto the District Court approved a modified plan for

desegregation. Other proceedings were had, including con

sideration of a Motion for Further Relief, upon which the

order before us on appeal was entered.

The District Judge, in an opinion covering fourteen pages

of the record, gave consideration to the application for fur

ther relief by the plaintiffs-appellants, and in his opinion

directed that further steps he taken for improvement of

the progress of desegregation in the schools of the City

of Memphis. His opinion, however, states:

“In this cause the Court finds that the defendant Board

has acted in good faith as it interpreted its burden

to desegregate the schools in its system.”

His opinion further requires that steps he taken to fully

comply with the requirements of desegregation as to both

pupils and faculty. His opinion calls for the appointment

by the School Board of an administrative officer designated

Director of Desegregation, to direct and cooperate in the

Court of Appeals’ December 19, 1969 Order

3a

carrying* out of a supplemental plan heretofore proposed

by the Memphis Board of Education. His opinion further

commands:

“Prior to January 1, 1970, the Board will file in this

cause maps showing the revised zone boundary lines

and will file enrollment figures by race of the pupils

actually attending the schools as of the time of the

report and enrollment figures by race of the pupils

who live in the proposed revised zones. The Court

will then consider the adequacy of the revised zone

boundaries and will reconsider the adequacy of the

transfer plan for future years in accordance with the

holding of the Supreme Court that district courts

should retain jurisdiction to insure that a constitu

tionally acceptable plan is operated ‘so that the goal

of a desegregated, non-raeially operated school system

is rapidly and finally achieved.’ ”

It appears to this Court that the imminence of the

presentation and consideration by the District Judge of

the proposed plan to be submitted on or before January

1, 1970, suggests the impracticality of this Court attempt

ing at this time to consider precipitously the various claims

asserted by plaintiffs-appellants in their appeal, and mo

tions. This Court has been familiar with the problems of

desegregation in the schools of Memphis since 1962, when

it had before it the first judgment commanding desegre

gation, entered by the District Court on May 2, 1961. From

review of this litigation and its underlying factual situa

tion, it is satisfied that there is no need at this time for

precititous action. Therefore, no further order need be

entered in this Court until the United States District Court

has had submitted to it the ordered plan, and has had

opportunity to consider and act upon it.

Court of Appeals’ December 19, 1969 Order

4a

NOW, THEREFORE, IT IS HEREBY ORDERED that this Cause

be, and it is, hereby remanded to the United States District

Court for the Western District of Tennessee, Western

Division, for further consideration of the plaintiff s-appel-

lants’ petition for further relief, and the plan, or any

amendment thereto, to be presented to the District Court

as required by its order of May 23, last.

Entered by order of the Court.

Court of Appeals’ December 19, 1969 Order

/ s / Carl W. R etjss,

Carl W. Reuss

Clerk

5a

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

F oe th e S ix t h Circuit

No. 19,993

Court of Appeals’ January 12, 1970 Order

D eborah A. N oethcross, et at.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

B oard of E ducation o f the Memphis,

Tennessee, City Schools,

Defendants-Appellees.

Order

Before W eick and Celebrezze, Circuit Judges, and

O’S u llivan , Senior Circuit Judge.

T h is Cause is now before this Court upon appellants’

Motion for Injunction Pending Certiorari. Such pleading

evidences plaintiffs’ purpose to apply to the United States

Supreme Court for a writ of certiorari to review an order

of this Court entered in this cause on December 19, last.

This litigation relates to the sufficiency of desegregation of

the public schools of Memphis, Tennessee. By our order of

December 19, we remanded this case to the United States

District Court for the Western District of Tennessee. Such

remand was for the purpose of providing District Judge

Robert M. McRae, Jr., with opportunity to consider whether

a plan, heretofore required by him to be filed on or before

January 1, 1970, would conform to the commands of an

order and opinion of said District Judge relating to further

6 a

desegregation of the Memphis schools. Such order and

opinion are the subject of the appeal disposed of by our

remand.

The motion now before us asks the immediate issuance

of an injunction which will require:

“1) The District Court to order the appellee City of

Memphis Board of Education to prepare and file on or

before January 5, 1970, in addition to the adjusted

zone lines it is presently required to file, a plan for

the operation of the City of Memphis public schools

as a unitary system during the current 1969-70 school

year.

“2) Appellants further move the Court that it issue its

injunction requiring the District Court to hold hear

ings on any objections to the proposed plan no later

than January 9, 1970 ; requiring it to issue its decision

no later than January 14, 1970, with same to be filed

with the Clerk of the Court of Appeals and providing

for review by this Court upon motion of the parties

made within ten days of entry of the order on such

papers as are then available in the record of the Dis

trict Court.”

Appellants support their motion with citation of authori

ties which they assert require the action they ask us to take,

v iz : Alexander v. Holmes Board of Education, 398 U.S. 19;

Carter v. West Feliciana Parish School Board No. 944,

— U.S. ------ , December 13, 1969, 38 U.S.L. Week 3220;

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School District,

—— F(2) — — (5th Cir. 1969, No. 26,285); Nesbit v. The

Statesville City Board of Education,------ F (2) —— (4th

Cir. 1969, No. 13,229).

Court of Appeals’ January 12, 1970 Order

7a

To the extent that the relevant factual context of the

above cases is disclosed by the opinions available to ns,

we conclude that they are not analogous to the case before

us. We are satisfied that the respondent Board of Educa

tion of Memphis is not now operating a “ dual school sys

tem” and has, subject to complying with the present

commands of the District Judge, converted its pre-Brown

dual system into a unitary system “within which no person

is to be effectively excluded because of race or color.” In

Alexander v. Holmes Board of Education, supra, the Su

preme Court exposed the question then before it as

involving:

“ the denial of fundamental rights to many thousands of

school children who are presently attending Mississippi

schools under segregated conditions contrary to the

applicable decisions of this Court.”

This quotation is not descriptive of the present situation

of Memphis. For the school year 1969-70, there are approx

imately 134,000 children enrolled in the schools of Memphis,

of which approximately 60,000 are white and 74,000 are

Negroes. Upon the oral argument of this appeal, we asked

counsel for plaintiffs to advise what he considered would

be the “unitary system” that should be forthwith accom

plished in Memphis. He replied that such a system would

require that in every public school in Memphis there would

have to be 55% Negroes and 45% whites. Departures of

5% to 10% from such rule would be tolerated. The United

States Supreme Court has not announced that such a for

mula is the only way to accomplish a “unitary system” .

We have expressed our own view that such a formula for

racial composition of all of today’s public schools is not

required to meet the requirement of a unitary system. Deal

Court o f Appeals’ January 12, 1970 Order

8a.

v. Cincinnati Board of Education (Ohio schools) 369 F(2)

55 (6th Cir. 1966), cert, denied, 389 U.S. 847 (1967); Mapp

v. Board of Education, (Tennessee schools), 373 F(2) 75,

78 (6th Cir. 1967); Goss v. Knoxville Board of Education

fTenn. schools) 406 F (2) 1183 (6th Cir. 1969); Deal v.

Cmcinnati Board of Education, (Ohio schools) ------ F (2)

------ (6th Cir. 1969).

The District Judge’s opinion in this case evidences his

awareness of today’s requirements for school desegrega

tion and his purpose to require strict obedience by the

Memphis Board of Education to all of such requirements.

"We are advised that the plan which he required to be filed

by January 1, 1970, is now before him. We are satisfied

that he will consider it with appropriate dispatch, to the

end that any deficiencies in the plan now in operation in

Memphis will be corrected.

Our own familiarity with the progress of desegregation

in the Memphis schools and our confidence in the District

Judge to whom we have remanded this litigation suggests

that it is not now needed that we issue the injunction asked.

The Motion for Injunction Pending Certiorari is denied.

Entered by order of the Court.

Carl W. R euss

Clerk

Court of Appeals’ January 12, 1970 Order

I n the

UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

F or th e W estern D istrict of T ennessee,

W estern D ivision

No. 3931— Civil

District Court’s May 15, 1969 Opinion

D eborah A. N orthcross, et al.,

vs.

Plaintiffs,

B oard of E ducation of the

M em ph is C ity S chools, et al.,

Defendants.

Opinion

The plaintiffs in this cause filed a Motion for Further

Relief based upon a ruling of the Supreme Court in Green

v. School Board of New Kent County, Virginia, 391 U.S.

430; Raney v. Board of Education, Gould School Distrct,

391 U.S. 443; and Monroe v. Board of Commissioners of

Jackson, Tennessee, 391 U.S. 450, all dated May 27, 1968.

Plaintiffs sought by their motion the cancellation of trans

fers and the requirement of additional desegregation of

faculty members for the 1968-69 school year, an order of

the court requiring a survey and report and a modification

of the plan of desegregation heretofore entered in this cause

on July 29, 1966. The application for immediate relief per

taining to the 1968-69 school year was heard and ruled

upon by the Honorable Bailey Brown, Chief Judge of this

10a

district. On November 8, 1968, a further hearing was had

and this Court ordered the defendants to compile and fur

nish a report for the Court's further consideration con

cerning the plan of desegregation of the defendants. After

the report was filed, the Court conducted a three-day hear

ing on the adequacy of the existing plan and proposed

modification thereof. Proof was offered by the plaintiffs

wherein it was asserted that the defendants have not and,

under the existing plan, would not perform their affirmative

duty of desegregating the former dual system of schools

as required by the Green, Raney and Monroe cases.

The defendant School Board is elected by the voters in

the City of Memphis to operate a school system which

presently has an enrollment of 123,280 students; 65,170 of

them are Negro and 58,110 are white. It operates a total

of 149 elementary, junior high and high schools and it

employs approximately 5200 teachers. The defendant school

system is one of the largest single systems in the United

States. By some standards it is considered twelfth in the

nation. The instant suit was filed in March 1960 and there

have been numerous proceedings in both the District Court

and the Court of Appeals pertaining to this case. The last

order in the cause before the present motion was filed was

entered on July 29, 1966. This provided for a plan of

desegregation which divided the defendant system into

separate geographic zones at the elementary, junior high

and high school levels. Pupils within the system have

been assigned to the respective zones and have been allowed

to transfer under a system whereby free transfers are per

mitted subject to space in the respective schools. As of the

current school year, 1968-69, there are presently 35 all white

schools, 50 all Negro schools, 47 predominantly white

schools and 17 predominantly Negro schools. This is

District Court’s May 15, 1969 Opinion

11a

based upon information furnished by the defendant school

system as set forth in Trial Exhibit #6, wherein the cur

rent enrollment and pupil population based upon students

residing in each attendance zone is set forth. For conven

ience of the Court, this was compiled on the basis of ele

mentary schools, junior high schools and high schools. For

promotion and record keeping purposes the system operates

an elementary school of six grades, junior high of three

grades and high school of three grades.

The defendant has compiled graphs and charts which

indicate that 47,586 pupils within the system are attending

schools with mixed racial enrollments. An examination of

the enrollment figures shows that in some cases this in

cludes a school wherein the ratio will be 1 white to 1822

Negro pupils, as in the case of Lincoln Junior High, and

1 Negro to 876 white pupils, as in the case of Treadwell

Junior High. During the current year 71.5% of the Negroes

attend all Negro schools. In certain schools within the

system there is a more equal mixing of the races, as in the

case of Pope Elementary School, where the enrollment

indicates there are 325 white pupils and 372 Negro pupils.

It is interesting to note that pupils who reside in this zone

number 230 white pupils and 256 Negro pupils. The proof,

including maps which reflect the racial residential concen

trations in the City of Memphis, shows that the Negro

population is heavily concentrated in the older parts of

the city and generally in a westwardly direction. Very few

white citizens reside in these areas. In the extreme north

ern, eastern and southern portions of the city the racial

concentration of the residents is overwhelmingly white.

Within the geographic center of the city there is a pre

dominantly white area ringed by mixed or Negro neighbor

hoods. W ithin this center area are located the more de

District Court’s May 15, 1969 Opinion

12a

segregated schools, including Technical High School which

has the highest high school ratio of mixed enrollment.

The system does not furnish transportation for its pupils

except in unusual circumstances. The various buildings

have been located on a neighborhood plan whereby an

attempt has been made to provide for every student in the

city a school as conveniently located as possible, taking

into consideration such factors as the age of the students,

natural boundaries in the form of major thoroughfares and

other relevant factors.

The testimony reflects that the system is bussing some

white students to overcome temporary problems. In the

southeastern portion of the city some high school students

have been bussed in a relatively new zone during the

establishment of a new school in which a new grade has

been added each year. This bussing will be complete this

year. In the northwestern portion of the city some students

in an all white elementary school zone are bussed to avoid

a hazardous railroad crossing. This will be discontinued

when an overpass is available for the use of those young

pupils.

The system has no power to impose taxes. Its funds

for operating expenses and capital improvements must

be allocated by the City Council. Therefore, the Board is

competing with all other phases of the city government

for its necessary funds.

The system has been and is faced with the problem of

providing school facilities to students who live in newly

annexed areas wrhich wrere formerly located in Shelby

County outside the city limits. This usually requires new

construction because the County system provides trans

portation for some of its students.

A plan which would require the defendants in this cause

to provide transportation on a system-wide basis in order

District Court’s May 15, 1969 Opinion

13a

to effectuate substantial desegregation is not economically

feasible. However, this Court is of the opinion that bussing

which would result in further desegregation would be ap

propriate in preference to permanent additions to schools

when population shifts have created or will likely create

under capacity schools in one zone and over crowded

schools in other zones.

The proof reflects that G-etwell Elementary School is a

school presently attended by 50 Negroes and no whites.

It is in a recently annexed area in the southeastern portion

of the city which is not densely populated. The geographic

area of the zone includes 47 Negro pupils and 48 white

pupils. The school is a legacy through annexation from

the county. The area does not justify building a new school

now but the pupils must be provided schools. The cost per

pupil for 1967-68 was $822.73 in this school when it had

76 pupils. In its post-hearing brief the defendant indicated

that the school would be closed next year. This should be

done.

The primary thrust of the plaintiffs’ proof and argument

is that transfers should be cancelled, thereby increasing de

segregation. The defendants assert that resegregation will

occur through migration by whites from zones integrated

above a “ tilt” point of 30% Negro.

It is apparent from the proof that the cancellation of

all transfers will not effect the racial make-up of many

schools because of the segregated housing patterns in dif

ferent sections of the city which are miles apart. Undoubt

edly, this is due in a large measure to economic factors

over which the defendant Board has no control.

By way of illustration, certain phases of the high school

enrollment and zone population figures by races are sum

marized herein. There are, exclusive of the technical high

District Court’s May 15, 1969 Opinion

14a

school, 22 senior high schools in the system. At present

7 are all Negro and 6 are all white. If all transfers were

cancelled and pupils who live in the respective high school

zones were assigned to their zones of residence 1 school

would remain all Negro and 6 wTould remain all white. The

6 presently all Negro schools would receive a total of 88

white pupils where they would be in respective racial

minorities of .0008 at Carver, .012 at Hamilton, .021 at

Manassas, .043 at Melrose, .001 at Booker T. Washington

and .01 at Douglas. If no majority to minority transfers

were permitted 50 Negro pupils would not be permitted

to attend predominantly white desegregated schools. This

is based upon the present transfers by Negroes to Central

and East High Schools.

I f majority to minority transfers were allowed and

the minority white students mentioned above could not

transfer, whereas the Negro students could and would

there would still be a reassignment of 258 Negroes from the

presently desegregated Northside High School. These

pupils have transferred from five of the overwhelmingly

Negro zones to Northside. At Northside they are in a

racial majority of 95%, whereas in the schools in the zones

of their residence they would be in racial majorities rang

ing from a low of 95.7% to a high of 99.92%.

The zone lines established by the Board have been the

subject of prior proceedings in this cause. See Northcross

v. Board of Education, 33 F2d 661 (C.A. 6, 1964). Again

the zone lines are attacked on the basis that they perpetuate

segregation. Trial Exhibits #31 through #34 reveal that

there have been substantial changes in the attendance fig-

uies of the schools in recent years in many of the zones.

For example, at Hollywood Elementary School the atten

dance in 1963-64 was 371 whites and 5 Negroes, whereas in

District Court’s May 15, 1969 Opinion

15a

1968-69 the school has 814 Negroes and no white pupils.

In the case of Longview Elementary School, in 1965-66

there were 592 whites and 265 Negroes, whereas in 1968-69

there are 1290 Negroes and 16 whites. These changes pri

marily were caused by changes in neighborhood racial pat

terns. In addition to racial changes, some of the zones

have diminishing numbers of school age students and hence

are operating at under capacity. Fairview Junior High

had 786 students in 1965-66 and now has only 476. The

school is still approximately 75% vThit.e. An examination

of the racial residential density map and zone figures shows

that the inner city is the area where the most significant

desegregation does and will occur in the near future unless

a massive bussing system is installed. Within this general

area some glaring islands appear. For example, Carpenter

Elementary, grades 1-3, and Lester Elementary, Junior

High and High Schools have a total of 2396 students, all

Negro. Treadwell and East High Schools have grades 1

through 12 and are immediately adjacent to the Lester-

Carpenter zone. Treadwell has 2884 whites and 8 Negroes.

East has 1866 white students and 19 Negroes. The defen

dants point out that the Lester-Carpenter “island” zone

boundaries are necessary because of industrial and com

mercial barriers, major thoroughfares and railroad tracks.

The plaintiffs point out that these same tracks bisect other

zones in other parts of the city.

The defendant’s initial response to the pending Motion

for Further Relief was a complete defense of its present

system. During this hearing the Board offered a Supple

mental Plan which proposes that the defendant Board

appoint a Director of Interscholastic Activities who shall

be charged with the responsibility of formulating plans

and programs for inter scholastic and extracurricular ac

District Court’s May 15, 1969 Opinion

16a

tivities on a biracial basis. This would include temporary

principal and teacher exchanges and pupil exchanges in

various areas, including vocational training, arts and crafts,

academic courses and music and debate.

Faculty desegregation in the defendants’ system was

first undertaken in the school year 1966-67, when faculty

members were assigned as members of a minority race in

the schools which had formerly had total white faculties

and total Negro faculties under the dejure system of seg

regated schools. In 1967-68 the number of minority assign

ments was 226. After the pending motion was filed in July