Delaware State Board of Education v. Evans Brief in Opposition to Certiorari

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1977

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Delaware State Board of Education v. Evans Brief in Opposition to Certiorari, 1977. 15733696-af9a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/bffd7815-5be8-4319-89a8-abceae78675c/delaware-state-board-of-education-v-evans-brief-in-opposition-to-certiorari. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

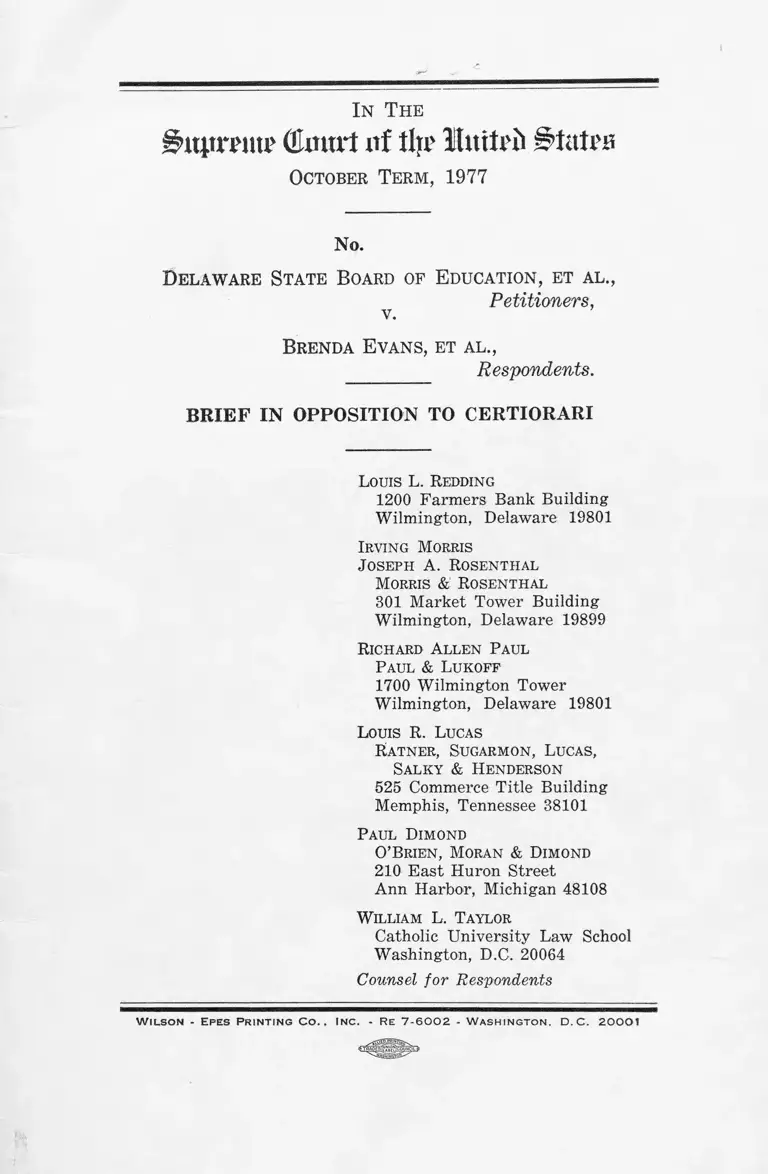

In The

iutjuTnu' Olxmrt xif tin' Hxtrtx>x» i>tatx>a

October Term, 1977

No.

Delaware State Board of Education, et al.,

Petitioners,v.

Brenda Evans, et al .,

Respo'iidents.

BRIEF IN OPPOSITION TO CERTIORARI

Louis L. Redding

1200 Farmers Bank Building

Wilmington, Delaware 19801

Irving Morris

Joseph A. Rosenthal

Morris & Rosenthal

301 Market Tower Building

Wilmington, Delaware 19899

Richard Allen Paul

Paul & Lukoff

1700 Wilmington Tower

Wilmington, Delaware 19801

Louis R. Lucas

Ratner, Sugarmon, Lucas,

Salky & Henderson

525 Commerce Title Building

Memphis, Tennessee 38101

Paul Dimond

O’Brien, Moran & Dimond

210 East Huron Street

Ann Harbor, Michigan 48108

W illiam L. Taylor

Catholic University Law School

Washington, D.C. 20064

Counsel for Respondents

W i l s o n - E p e s P r i n t i n g C o . . In c . - R e 7 - 6 0 0 2 • W a s h i n g t o n . D . C . 2 0 0 0 1

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Brief In Opposition to Certiorari ..... .......................... . 1

Opinions Below _______ _____ ____ __________________ 1

Jurisdiction ____ 2

Questions Presented ............ ...... ............. ...... .................. 2

Statement __________________________ „ _____________ 2

A. Introduction ___ 2

B. Prior Proceedings ____ __ ___________ _____ _ 3

C. The Character of the Inter-District Violation

Previously Found by the Three-Judge Court.... 10

D. The Scope of the Interim Remedy Ordered by

the District Court and Affirmed by the Court of

Appeals ............................... 15

Reasons Why the Writ Should Be Denied___________ 21

1. Violation _____ _______________________ _____ 22

2. Remedy ............... 27

Conclusion __ 31

II

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases Page

Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Education,

396 U.S. 19 (1969)__________________________ 30

Bradley v. School Board of City of Richmond,

Virginia, 462 F.2d 1058 (1972), aff’d by an

equally divided Court, 412 U.S. 92 (1973) ------23n.l5

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954)

349 U.S. 294 (1955) ________________________ passim

Carter v. West Feliciana Parish School Board, 396

U.S. 226 (1969)__________________________ __ - 30

Castaneda v. Partida, 45 L.W. 4302 (23 March

1977) „ ......... ............... - .................. - ------- --------- 26

Dayton Board of Education v. Brinkman, No. 76-

539, 45 L.W. 4910 (27 June 1977) ____14 n.9,18, 22,

26 n.18, 27, 28, 29

Edelman v. Jordan, 415 U.S. 651 (1974) -----------24 n.16

Evans v. Buchanan, 195 F. Supp. 321 (1961) ------ 3, 4

Evans v. Buchanan, 379 F. Supp. 1218 (1974)..3, 4, 10 n.4,

11,12, 14 n.9

Evans v. Buchanan, 393 F. Supp. 428 (1975) ....passim

Evans v. Buchanan, 423 U.S. 963 (1975) _______ 1, 3, 6

Evans v. Buchanan, ------ F. Supp. ------ (D. Del.

Aug. 5, 1977) (C.A. No, 1816-1822) ....18 n.12, 20 n.14

Hicks v. Miranda, 422 U.S. 332 (1975) ________24n.l6

Hills v. Gautreaux, 425 U.S. 284 (1976) _______ 19

Hunter v. Erickson, 393 U.S. 385 (1969) _______ 13, 25

Insurance Group v. Denver and Rio Grande

Western R. Co., 329 U.S. 607 (1946) ________ 24

Keyes v. School District No. 1, 413 U.S. 189

(1973) _____________ 12, 18 n.12, 22, 26 n.18, 27, 28, 29

Lee v. Nyquist, 318 F. Supp. 710 (W.D.N.Y.

1970), aff’d, 402 U.S. 935 (1971) __________ _ 25

McGinnis v. Royster, 410 U.S. 263 (1973) _____ 26 n.18

Milliken v. Bradley, 418 U.S. 717 (1974) -------- passim

Reitman v. Mulkey, 387 U.S. 369 (1967) _____14 n.9, 25

State Board of Education v. Evans, ------ U.S.

------ , 45 L.W. 3394 (29 November 1976) 8

Ill

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES— Continued

Page

Swann v. Charlott e-Mecklenburg Board of Educa

tion, 402 U.S. 1 (1971) ______11,12, 15, 17, 18, 28, 29

United States v. Scotland Neck City Board of

Education, 407 U.S. 484 (1972) __________14 n.9, 24

Village of Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan

Housing Development Corp., 429 U.S. 252, 97

S. Ct. 555 (1977) ________ 14 n.9, 22, 25, 26, 26 n.18, 27

Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229 (1976) ....14 n.9, 22,

25, 26, 26 n.18, 27

Wright v. Council of the City of Emporia, 407 U.S.

451 (1972) ______ ______________ ____ ....14 n.9, 24, 25

Statutes

14 Del. C. §§ 1004(c) (2), 1004 (c) (4), and 1005.... 4

20 U.S.C. § 1701 et seq _____________ 15 n.9, 21, 26 n.18

28 U.S.C. § 1253 ____________ _________ _____ __ 6

28 U.S.C. § 1254(1) __________________________ 2

28 U.S.C. §2281 _____________________________ 4

In The

Ihij.tnw (Exmrt of % MmM BtaUB

October T e r m , 1977

No.

D ela w a r e State B oard of E du cation , et a l .,

Petitioners,

B renda E v a n s , et a l .,

Respondents.

BRIEF IN OPPOSITION TO CERTIORARI

OPINIONS BELOW

The opinion of the Court of Appeals for the Third Cir

cuit is reported at 555 F.2d 373 (1977) and is also set

out as Appendix A of the Petition for Writ of Certiorari

in Delaware State Board of Education, et al v. Brenda

Evans, et al., No. 77-131. The May 19, 1976 Opinion and

June 15, 1976 Interim Remedy Judgment of the United

States District Court for the District of Delaware are

reported at 416 F. Supp. 328 and are set out as Appendix

B of the State Board’s Petition for Writ of Certiorari.

The prior inter-district violation Ruling and Judgment of

the District Court are reported at 393 F. Supp. 428

(D. Del. 1975), aff’d 423 U.S. 963 (1975).1

1 References to the Court of Appeals’ opinion and to the District

Court’s Interim Remedy Ruling will be to the Appendix in the

State Board’s Petition for Writ of Certiorari, in the form, for

example, of A. 16. Citations to the other opinions and orders in

this cause will be in the form, for example, of 393 F. Supp. at 430.

2

JURISDICTION

The Opinion of the Court of Appeals was entered on

May 18, 1977. This Court’s jurisdiction is invoked under

28 U.S.C. 1254(1).

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Whether any issue worthy of reexamination by this

Court is presented by the District Court’s application of

Milliken v. Bradley, standards to find an inter-district

constitutional violation in the operation of the public

schools of northern New Castle County.

2. Whether any issue warranting this Court’s review

is presented by the Court of Appeals’ affirmance of the

District Court’s judgment: (a) delineating, in advance of

the submission of an acceptable plan for reassigning stu

dents, the geographical area within which desegregation

must take place for the scope of the remedy to match the

scope of the violation; and (b) establishing a mechanism

for organizing the public schools of northern New Castle

County into a unitary system which is to become opera

tive only if the State does not prescribe its own mechanism.

STATEMENT

A. Introduction

For the third time in two years, the Delaware State

Board of Education and other Petitioners seek to invoke

this Court’s jurisdiction to review lower court rulings that

the State of Delaware has violated the constitutional

rights of black Respondents and that a remedy must be

adopted that is commensurate with the scope of the viola

tion found. All of these efforts have been undertaken in

advance of the adoption of any plan of student assignment

to cure the violation found.

3

As in their last effort to obtain a review, Petitioners

persist both in regarding no issue in this case as having-

been settled by this Court’s prior dispositions and in in

dulging in sweeping mischaracterizations of the findings

and conclusions of the lower courts.

It is Respondents’ position that the holdings of the

courts below through the Court of Appeals’ affirmance

(555 F.2d 373, A. 1) with modification of the Three-Judge

Court’s interim remedy ruling (416 F. Supp. 328, A. 32)

are in accord with the decisions of this Court dealing both

with the violation and standards for framing a remedy.

We also believe that the existence of an inter-district

violation has already been settled by this Court’s affirm

ance (423 U.S. 963) of the District Court decision finding-

such a violation (393 F. Supp. 428) and that there is no

occasion for this Court to reexamine its prior disposition.

A summary of the violation found and remedial standards

applied below may assist this Court in determining

whether Petitioners present any issue worthy of review.

B. Prior Proceedings

This is simply the latest phase of a lawsuit begun in

1957 whose “object was to eliminate de jure segregation

in Delaware schools” , including those of New Castle

County as well as other districts. 393 F. Supp. at 430.

Although a plan for desegregation of Delaware schools

was accepted in 1961, the Court approved the plan “only

to the extent that it [would prove] effective” , 379 F. Supp.

1218, 1223 (1974), and retained jurisdiction, 195 F. Supp.

321, 325 (1961). The plan did not prove effective in

New Castle County. 379 F. Supp. at 1223 and 1228-30;

393 F. Supp. at 433, 437-8.

The inter-district violations later found were rooted in

circumstances existing at the time of Brown v. Board of

Education. Local school districts in Delaware at that time

4

were “not meaningfully ‘separate and autonomous’ ” , 893

F. Supp. at 437, but rather were subordinate to the State

system of segregation with boundaries that were dual and

overlapping, permeable, or disregarded for the purpose of

imposing racially segregated schooling. To deal with this,

the District Court’s 1961 decree ordered that as part of

the plan for desegregation, the State Board submit a re

vised school code to the legislature, including a reorganiza

tion of the “crazy quilt-pattern of [school] districts and

laws governing education.” 195 F. Supp. at 325.

In belated response, the legislature in 1968 enacted the

Educational Advancement Act which explicitly excluded

the Wilmington school district from the discretion vested

in the State Board to reorganize all districts in the state,

expressly providing that the boundaries for this “reor

ganized school district shall be the City of Wilmington

with the territory within its limits.” 14 Del. C. .§§ 1004

(c) (2), 1004(c) (4), and 1005.

In 1971, plaintiffs, by amended complaint, petitioned the

District Court for supplemental relief; challenged the

constitutionality of the 1968 Act and redistricting; and

requested that the continuing inter-district segregation in

New Castle County be finally and effectively dismantled.

A three-Judge Court was convened pursuant to 22 U.S.C.

2281. On July 12, 1974, following a lengthy evidentiary

hearing, briefs and argument, the District Court found

continuing de jure violations within Wilmington, but re

served ruling on the claims of inter-district segregation

including the constitutionality of the 1968 Act. 379

F. Supp. 1218.

After this Court issued its opinions in Milliken v.

Bradley, 418 U.S. 717 (1974) the District Court promptly

invited the reorganized school districts of New Castle

County to intervene and present evidence on all the issues

raised by plaintiffs’ 1971 Petition for Supplemental Relief

5

and Amended Complaint. Suburban school districts inter

vened as parties defendant;2 they elected to adopt the

State Board pleadings and to stand on the evidence already

of record and to submit briefs on the inter-district viola

tion issues and the impact of Milliken. Primary issues

litigated by the parties included the alleged continuing

nature of the historic inter-district dual system; the pur

pose and effect of acts following Brown, including a state

wide reorganization of school districts, alleged to be either

independent constitutional violations or ineffective means

of eliminating the continuing effects of the inter-district

de jure segregation; and the extent to which the existing

racial disparity in enrollments between Wilmington and

suburban NewT Castle County school districts resulted

from the inter-district effect of any constitutional viola

tions rather than other causes. On March 27, 1975, the

District Court, Judge Layton dissenting, issued its Opin

ion. Applying the Milliken legal standards to the evidence

adduced, the District Court found significant inter-district

de jure segregation throughout New Castle County. 393

F. Supp. at 431-2, 438, 445, 447. Specifically, the District

Court found an inter-district violation based on “ (a) a

historic arrangement for inter-district segregation within

New Castle County; (b) significant governmental in

volvement in inter-district discrimination; and (c) uncon

stitutional exclusion of Wilmington from consideration

for consolidation by the State Board of Education pur

suant to reorganization powers now lapsed.” 393 F. Supp.

at 445. The District Court further found the inter-district

violation “responsible to a significant degree for the in

creasing disparity in residential and school populations

between Wilmington and its suburbs in the past two

decades.” 393 F. Supp. at 438. See also, 393 F. Supp. at

444-5. Accordingly, the Court directed the parties to sub

2 The Wilmington school district had previously intervened as

a party plaintiff and joined in the Petition and Amended Complaint.

6

mit alternative inter-district and intra-district desegrega

tion plans. 393 F. Supp. at 447.

The State Board appealed the inter-district violation

Judgment and Order invoking this Court’s jurisdiction

under 28 U.S.C. 1253. In its Jurisdictional Statement, the

Appellant State Board argued that the findings of a sub

stantial inter-district violation were incorrect. Appellees

filed a Motion to Dismiss or Affirm, arguing that there

were substantial grounds for either disposition. This

Court summarily affirmed, Rehnquist, J. joined by Burger,

C. J., and Powell, J., dissenting, on grounds that the ap

peal did not lie under 28 U.S.C. 1253 within the Supreme

Court’s jurisdiction because the case was not one required

to be heard by a three-judge court. 423 U.S. 963.

In August 1975, the parties submitted desegregation

plans to the District Court. There followed three weeks

of evidentiary hearings during which defendants again

had the opportunity to present proof that the public

school segregation existing in New Castle County, beyond

that already determined to be the product of de jure acts,

was not attributable to a discriminatory purpose or the

reciprocal effect of the deliberately discriminatory actions

already adjudicated. On May 19, 1976, the District Court,

Judge Layton dissenting in part, issued its Interim

Remedy Ruling, followed by the Interim Remedy Order

on June 15, 1976.

The Court reiterated its findings concerning the extent

of the effects of the inter-district violation: “ [t]he acts

described in the prior opinions were the acts of the State

and its subdivisions and had a substantial not a de mini

mis effect on the enrollment patterns of the separate dis

tricts . . . The State Legislature and the State Board of

Education . . . acted in a fashion that is a substantial

and proximate cause of the existing disparities in racial

enrollments in the districts in northern New Castle

County.” (A. 52-3). The Court determined that a Wil

7

mington-only plan would not satisfy its duty to place the

victims of the violation in substantially the position they

would have occupied had the violation not occurred and

that this duty, when viewed in the light of the extent of

the inter-district violation, required the inclusion of all but

one of the twelve New Castle County districts in the area

in which desegregation would take place. A, 55, 60, 78-82.

Rather than selecting any of the various plans submitted,

the Court established an interim framework for develop

ing an effective remedy. A. 76-94. Contrary to appellants’

assertion that the Court provided “ that eleven of the

twelve districts in New Castle County be collapsed into a

single super-district . . . .,” (State Board Pet. p. 8), the

Court simply required that desegregation take place in ac

cordance with the Opinions of the Court and that the

State Board of Education establish an interim board

drawn from the local districts which would serve as a

consolidated body, pursuant to the State law model, to

implement a desegregation plan only if the State failed

to take action to remedy the inter-district segregation

flowing from the violation. A. 74-78, 85-88.

Petitioners again sought review in this Court, praying

that the Court either note probable jurisdiction or, in the

alternative, grant certiorari prior to judgment by the

Court of Appeals. In their jurisdictional statements they

again challenged the existence of the inter-district viola

tion as well as the remedy ordered. The Solicitor General

filed a memorandum for the United States as amicus

curiae, arguing inter alia (1) that further review of the

existence of an inter-district judgment, including the un

constitutionality of the Educational Advancement Act “ is

foreclosed in substantial measure by [the Supreme]

Court’ summary affirmance of the judgment on the liabil

ity question. . . .” (U.S. Memo, p. 1, n. 1) ; and (2) that

the “ significant and continuing inter-district acts of racial

discrimination between New Castle County school dis

tricts . . . would [in any event] require a significant

8

inter-district remedy.” (P. 9). In the Solicitor’s view, it

followed from this understanding of the posture of the

case that direct appeal did not lie because the interim

remedy judgment was not required to be entered by a

three-judge court. On November 29, 1976, this Court dis

missed appellants’ direct appeals, State Board of Educa

tion v. Evans, ------ U.S. ------ , 45 U.S.L.W. 3394. (29

November 1976)

Appellants then pursued their appeals in the Court of

Appeals for the Third Circuit under an expedited brief

ing schedule. Following oral argument before the Court

sitting en bane, on May 18, 1977 the Court issued its

opinion and judgment, affirming the judgment below with

certain modifications largely designed to give the State

Legislature or the State Board of Education a further

opportunity to prescribe the plan and method of reorga

nization that would eliminate the dual system and the

vestige effects of de jure segregation. A. 20-4. The court

viewed itself as precluded by this Court’s summary affirm

ance from reexamining the existence of a substantial in

ter-district violation. A. 12-14. But, in reviewing the

District Court’s decision concerning the scope of remedy,

the Court of Appeals examined the extent of the inter

district violation, for it recognized that “ [t]he existence

of a constitutional violation does not authorize a court to

bring about conditions that never would have existed even

if there had been no constitutional violation . . . the school

district and its students are to be returned, as nearly as

possible, to the position they would have been in but for

the constitutional violations that have been found.” A. 16-

17. Having conducted this review, the court affirmed the

District Court’s decision concerning the appropriate extent

of the desegregation area along with other aspects of the

remedial framework. The Court of Appeals, however, re

fused to embrace the Three-Judge court’s description of

“prima facie desegregated schools” as those having an

9

enrollment not substantially disproportionate to the over

all inter-district racial enrollment insofar as it might be

interpreted by others as imposing a racial quota. A. 18-19.

Judge Garth, joined by Judges Rosenn and Hunter,

dissented on grounds that the majority had failed (1)

to review the existence of inter-district violations and

to identify them specifically; and (2) to assess the ef

fects of the violations on the racial composition of schools

in northern New Castle County. A. 25. They would

have remanded the case to the District Court to require

a precise finding of racially discriminatory intent with

respect to each inter-district violation3 and a precise

calibration of the extent to which segregation in north

ern New Castle County was caused by the inter-district

violations as against other, presumably nondiscriminatory

factors. A. 38-41. The dissent, however, failed to state

in what respect the specific findings of the Three-Judge

Court concerning the nature of the inter-district viola

tion and the extent of its impact on northern New Castle

County fell short of meeting these requirements.

The State Board of Education and suburban school

districts now petition for a writ of certiorari, seeking

a plenary review of all material issues previously ad

judicated by the lower courts.

3 The dissenters perceived eight inter-district violations, a num

ber they apparently arrived at by regarding each element of dis

crimination that underlay the findings of “ significant governmental

involvement in inter-district discrimination” as a separate inter-

district violation. They acknowledged, however, that the racially

discriminatory motivation of several of these elements was obvious.

A. 39. They neither mentioned or considered the historic inter-

district violation and its impact on the analysis of subsequent acts

and failures to act.

10

C. The Character of the Inter-District Violation

Previously Found by the Three-Judge Court

The District Court’s finding of a continuing inter-

district violation in New Castle County was based on a

careful application of Milliken legal standards to the

record evidence. The deliberate character and broad ex

tent of the violation were detailed in the District Court’s

1975 findings and may be summarized as follows:

1. At the time of Brown, and for some time there

after, the state-imposed system of complete segregation

“ in New’ Castle County was a cooperative venture in

volving both [Wilmington] city and suburbs . . . [A]t

that time, a desegregation decree could properly have

considered city and suburbs together for the purpose of

remedy. At that time, in other words, Wilmington and

suburban districts were not meaningfully ‘separate and

autonomous.’ ” 393 F. Supp. at 437. This ultimate find

ing was based on subsidiary findings of fact that local

districts were then subordinate and their boundaries dual

or overlapping or simply breached in order to implement

the basically monolithic Delaware system of school segre

gation, with one state system of schooling for blacks and

another for whites. Although the specifics of this unique

system varied somewhat from place to place and time

to time, 393 F. Supp. at 433, it was unmistakably “ a

historic arrangement for inter-district segregation within

New Castle County.” 4 393 F. Supp. at 447.

2. Far from effectively dismantling the system of

state-compelled inter-district segregation, Delaware of-

4 Thus, for example, the State-mandated and State-financed black

elementary, junior and senior high schools located within Wilming

ton long served substantial numbers of black children who resided

throughout New Castle County. 393 F. Supp. at 433. Likewise, de

jure white schools located in Wilmington served substantial num

bers of white children who resided in New Castle County. Id. See

also, 379 F. Supp. at 1230-31 (Circuit Judge Gibbons, separate

opinion).

11

ficials perpetuated and exacerbated the original viola

tion. 379 F. Supp. 1230-2, 393 F. Supp. 432-445. Over

the next two decades, there occurred, as the District

Court found, “ significant governmental involvement in

inter-district discrimination.” 5 6 393 F. Supp. at 447.

This involvement not only made the dismantling of the

historic inter-district segregation of New Castle County

much more difficult, 393 F. Supp. at 432-3 [Cf. Swann

v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board, of Education, 402 U.S.

1, 14 (1971)], but was also found by the District Court

to be an independent constitutional violation under Milli-

ken, significantly contributing to the marked inter-district

segregation flourishing in New Castle County schools.

393 F. Supp. at 438.

Through a series of specific public actions, govern

mental authorities supported and encouraged pervasive

practices of racial discrimination in suburban housing.*

This government-sanctioned discrimination7 excluded

5 This discrimination occurred during a period of great popula

tion growth and demographic change. From 1954 to 1973, the

public school enrollment of suburban New Castle County expanded

from 21,543 children (4 percent of whom were black) to 73,008

(6 percent of whom were black). This large suburban population

growth corresponded with the growth of Wilmington as an identi-

fiably black school system, changing from 12,875 pupils in 1954

(28 percent black) to 14,688 pupils in 1973 (83 percent black).

6 During this period, some time after Brown, suburban children

were withdrawn from Wilmington schools, which “reduced, to an

extent, the proportionate white enrollment” of Wilmington schools.

393 F. Supp. at 434 n. 8. While the District Court did not find

this to be an independent violation under Milliken, it. was a further

step in the continuing separation of the races in New Castle

County; and the District Court found that the contemporaneous

splintering of the suburban districts from Wilmington failed to

disestablish the inter-district dual system. 393 F. Supp. at 433,

437-8, 379 F. Supp. at 1228-1230 (Circuit Judge Gibbons, separate

opinion).

7 Governmental acts included policies advocating racially homo

genous neighborhoods as a condition of government assistance, the

continued recordation of racially restrictive covenants after they

12

black families from new housing opportunities in the

suburbs, thus excluding them from the burgeoning and

still virtually all-white suburban schools, and funneled

them into Wilmington, 393 F. Supp. at 434-5. At the

same time, state public housing authorities acted directly

to impose racial segregation by concentrating low income

housing for minority residents in the city of Wilmington

and virutally excluding such units from the suburbs,

thus excluding many black children from suburban

schools. 393 F. Supp. at 435. In finding that this con

duct constituted segregative action with inter-district

effects, the District Court cited Mr. Justice Stewart’s

concurrence in Milliken noting that an inter-district viola

tion is established when state officials “had contributed

to the separation of the races . . . by purposefully racially

discriminatory use of state housing or zoning laws.” 418

U.S. at 755.

In addition the Wilmington Board, with the sanction of

the State Board, maintained five pre-Brown “colored”

schools as virtually all-black schools and implemented dis

criminatory policies (e.g., optional zones) to define addi

tional schools as de jure black, with the effect of encourag

ing white outmigration and discouraging white families

from moving in to Wilmington. 393 F. Supp. at 436.

See, also, 379 F. Supp. at 1223.8 Subsequently, the State

also subsidized the transfer of substantial numbers of

white Wilmington children to private schools in the sub

were declared unenforceable by this Court, State publication of the

discriminatory code of ethics of the real estate industry and sanc

tion of restrictive real estate practices that denied minority home-

seekers access to all but a handful of suburban listings. 393 F.

Supp. at 434-5.

8 Thus were Wilmington schools “ earmarked” as the “black

schools” to all who cared to see throughout New Castle County. Cf.

Keyes V. School District No. 1, 413 U.S. 189, 202 (1973). (The

District Court credited testimony that sales in the housing market

are tied to the racial characteristics of the schools. 393 F. Supp.

at 437. Cf. Swann, 402 U.S. at 20-21.)

13

urbs. This, too, “has undoubtedly served to augment the

racial disparity between Wilmington and suburban public

school populations.” 393 F. Supp. at 437. These findings

of the District Court conformed closely to the standard

set for an inter-district violation in Milliken that “ there

has been a constitutional violation within one district

that produces a significant segregative effect in another

district.” 418 U.S. at 745.

Thus, during the decades after Brown, the Court found

that the historic, county-wide arrangement for inter-

district segregation, far from being dismantled, was con

tinued and significantly exacerbated by this variety of

racially discriminatory governmental conduct. Applying

the Milliken standards, the District Court concluded that

these inter-district segregation practices “ are responsible

to a significant degree” for the marked disparity between

Wilmington and suburban New Castle County school dis

tricts, 393 F. Supp. at 432.

3. Finally, against this background of continuing in

ter-district segregation the District Court found that the

Educational Advancement Act and statewide reorganiza

tion of school districts in 1968 “contributed to the separa

tion of the races by . . . drawing or redrawing of school

district lines” (Cf. Milliken, 418 U.S. at 755, Stewart

J., concurring), thereby further isolating Wilmington’s

basically black schools from their suburban and virtually

all-white counterparts by discriminatory state action. 393

F. Supp. at 445-6. The District Court based this declara

tion of unconstitutionality on a careful analysis of the

specific provisions and operation of the Act, as well as

their historical context, immediate objective and ultimate

effect. It found the exclusion of Wilmington in the cir

cumstances to be a suspect racial classification of the

kind invalidated by this Court in Hunter v. Erickson,

393 U.S. 385 (1969). After considering the purported

justifications and the alternatives proposed and studied,

14

the Court concluded that defendants had not met their

burden of jusifying the statute’s disparate treatment of

racial problems. 393 F. Supp. at 438-446. The Court

found:

Accordingly, the language of the Act excluding

Wilmington from consideration by the State Board

for reorganization violates the Equal Protection

Clause . . . [T]he reorganization provisions played a

significant part in maintaining the racial identifia-

bility of Wilmington and the suburban New Castle

County school districts.

393 F. Supp. at 445-6.9 This inter-district school district

9 Given the prior history and continuing inter-district segregation

and the outstanding 1961 court order to reorganize school districts

state-wide to eliminate all vestiges of the historic dual system, the

District Court’s evaluation of the 1968 Act and reorganization may

be viewed as pursuant to Wright V. Council of the City of Emporia,

407 U.S. 451 (1972) and United States v. Scotland Neck City Board

of Education, 407 U.S. 484 (1972). See 379 F. Supp. at 1225

et. seq. (separate opinion of Circuit Judge Gibbons); 393 F. Supp.

at 445; A. 53-54. Under this remedial test, although the District

Court found no dominant racial motive in the General Assembly

(393 F. Supp. at 445), the Court quite properly held that the Act

and reorganization both perpetuated and cemented the prior and

continuing inter-district violation. 393 F. Supp. at 445. However,

the District Court also found the 1968 Act and reorganization to

be an “ independent constitutional violation.” 393 F. Supp. at 438-

446. In this context, it is clear that the Court’s statement that the

provisions excluding the Wilmington District “were [not] purpose

fully racially discriminatory” refers to the dominant, subjective

motivation of the General Assembly and individual legislators and

not to a lack of intentional segregative action. 393 F. Supp. at 439.

Cf. Washington V. Davis, 426 U.S. 242 (1976); Village of Arlington

Heights v. MHDC, 429 U.S. 252, 97 S. Ct. 555, 563-565 (1977) ;

Dayton Board of Education V. Brinkman, 45 U.S.L.W. 4910 (27 June

1977). The District Court examined the proffered nonracial reasons

for Wilmington’s exclusion (393 F. Supp. at 439), but found them

unpersuasive, noting that the legislature fully appreciated the inter-

district segregative effects of its action. 393 F. Supp. at 439. In

the totality of the circumstances, the Court found that the Act

amounted to “ unjustified” or “ invidious” racial discrimination. 393

F. Supp. at 445-46 and n. 36. Cf. Reitman V. Mulkey, 387 U.S.

15

boundary violation affected all of New Castle County and

implicated every New Castle County school district in the

continuing inter-district segregation.

Based on the application of Milliken legal standards to

the weight of the record evidence, the District Court

found a substantial inter-district segregation violation

significantly contributing to marked racial disparity be

tween Wilmington and suburban New Castle County

school districts. 393 F. Supp. at 438, 445.

D. The Scope of the Interim Remedy Ordered by the

District Court and Affirmed by the Court of Appeals

1. In its interim remedy ruling, the District Court

began by analyzing the legal standards in Milliken and

Swann that establish the proper scope for the exercise of

equitable discretion to order a remedy for the inter

district segregation previously found. A. 50-6. In par

ticular the District Court, in adhering scrupulously to the

teachings of Milliken and Swann, held that the nature and

extent of the inter-district violation determine the proper

scope of any inter-district remedy (A. 51) ; that an inter

district violation must be substantial, not de minimis, and

proximately related to the present disparity in enrollment

patterns to require an inter-district remedy (A. 51-2) ;

and that the relief ordered must place the victims of the

violation in substantially the position they would have

occupied in the absence of the violation by insuring that

a racially non-discriminatory system of schools replaces

the basically dual system. A. 55. The Court of Appeals

confirmed that these were the appropriate constraints in

fashioning a remedy, restating them (A. 15-17) and add

369, 373 (1967). (In later evaluating the Act and reorganization

under the “purpose” language of 20 U.S.C. 1715 and 1756, the Court

held that it had found the requisite racially discriminatory purpose.

A. 94-6.)

16

ing for emphasis that “ [t]he remedy for a constitutional

violation may not be designed to eliminate arguably un

desirable states of affairs caused by purely private con

duct {de facto segregation) or by state conduct which

has in it no element of racial discrimination.” A. 17.

2. Having provided the defendants with another op

portunity during the remedial proceedings to demon

strate that the impact of the inter-district violation was

limited, the District Court weighed the evidence and again

found that the inter-district violation “had a substantial,

not a de minimis effect on the enrollment patterns of the

separate districts.” (A. 52). The District Court did not

deem it appropriate at that stage of the proceedings to

seek to delineate remedy on a school-by-school basis.

Rather, it sought to identify the geographical area within

which a desegregation remedy would be required. Hav

ing found that the racially discriminatory acts of the State

and its subdivisions were “ a substantial and proximate

cause of the existing disparity in racial enrollments in

northern New Castle County” 1,0 (A. 52-3), the Court re

jected all plans limiting the remedy to the confines of

Wilmington on grounds that they fell far short of remedy

ing the violations previously found. A. 58-60. While

affirming that all districts in northern New Castle County

were implicated in the violation, the District Court in

exercise of its equitable discretion limited the districts

to be included in further desegregation planning only to

those necessary for continuing and effective relief from

the violation. A. 78-82.10 11

10 The Court focussed primarily on the northern New Castle

County area which comprises 251 square miles with twelve school

districts (reorganized in 1968 from nineteen) and 80,678 public

school students, 19.4 percent of whom are black. Wilmington

schools are 84.7 percent black, while ten of the eleven suburban

school districts are more than 90 percent white A. 45-6 and n. 9.

11 This resulted in the exclusion of the one school district (Appo-

qunimink) most distant from Wilmington because, inter alia, its

17

While refraining from taking a school-by-school ap

proach, the District Court did deem it appropriate to offer

a guide to the desegregation planners. Based on its

reading of Swann, the Court stated that it would consider

any school whose enrollments in each grade ranged be

tween 10 and 35 percent black to be a prima facie desegre

gated school. A. 84. The Court made it clear that this was

intended as a flexible starting point, a guide not a quota.

Newark, for example, was left free to retain one-race

schools not only by demonstrating that the Swann feasi

bility standards limited desegregation, but also by show

ing that “ the existence of one-race schools is not due to

the maintenance of a dual system.” A. 82. The Court

of Appeals, however, refused to embrace the 10-35 per

cent enrollment range because of its view that this flexi

ble range might be interpreted as a fixed requirement.

A. 18-19.

Accordingly, the Court of Appeals, applying the re

medial standard that “the school system and its students

are to be returned, as nearly as possible to the position

they would have been but for the constitutional violations

that have been found” (A. 16-17), affirmed the District

Court’s finding of a violation with area-wide impact call

ing for an area-wide remedy. But the Court of Appeals

opinion does not rule out an ultimate desegregation plan

which leaves some facilities as one-race schools if it has

been demonstrated that this was the distribution that

would have existed even in the absence of any constitu

inclusion would not have any impact on the overall effectiveness

of any inter-district plan and its schools already were substantially

integrated relative to the areawide racial composition. A. 79.

Newark, the other district as to which there was substantial dis

pute among the parties, was included because, inter alia “ consti

tutional violations existed at the State level, and . . . the effects

of the pre-Brown segregation to which Newark was a party have

not yet been dissipated.” A. 80.

18

tional violation. See Dayton Board of Education v. Brink-

man, No. 76-539, 45 L.W. 4910, 4914 (27 June 1977).12

3. In examining various inter-district plans that had

been submitted by the parties, the District Court found

the use of voluntary transfer plans “ as the sole means of

system-wide desegregation . . . decidedly unpromising.”

A. 64. While noting that “ cluster or center plans” pro

posing mandatory reassignment between the existing

Wilmington and New Castle school districts would be

manageable and provide an effective remedy, the District

Court found that the assignment of pupils across district

lines would be difficult to administer and might require

continuing judicial supervision to resolve disputes. A. 67.

Seeking to follow a course that would require the least

judicial intervention, the Court, in exercise of its equitable

discretion, declined to order “ cluster and center plans.”

A. 68.

12 Defendants, however, failed in the violation and remedy hear

ings to adduce persuasive evidence that the existing racial disparity

in enrollments between northern New Castle County school districts

resulted from factors other than the constitutional violation found;

their evidence failed to counter persuasive evidence offered by

plaintiffs to the contrary. Most recently, on July 14, as the District

Court has reported, the State took the position that “ it is not

‘feasible’ to determine what the affected school districts and school

populations would be today ‘but for’ the constitutional violation

found by the Three-Judge Court and affirmed on appeal.” Evans V.

Buchanan, ---- - F. Supp. ------ - (D. Del. Aug. 5, 1977) (C.A. No.

1816-1822), Mimeo op. at 14. Whatever its utility in other situa

tions, this representation by defendants in a case where a substan

tial de jure violation has been determined hardly serves to meet

their burden of proving that the segregation remaining in the

area was not similarly caused. Keyes V. School District No. 1,

412 U.S. 189, 208-209. This final default by defendants provides

further justification for a conclusion that the segregative effects of

the violation on the racial distribution in northern New Castle

County are total and pervasive, requiring desegregation of every

school in the area except where Swann feasibility limitations in

trude. See Dayton Board of Education V. Brinkman, at 4914. No

plan of student reassignment, however, is before this Court.

19

With respect to the various proposals to redistrict or to

consolidate New Castle County districts,13 the District

Court held that “the power of the Court to order a re

organization would not appear to be in doubt,” given the

nature and extent of the inter-district violation, particu

larly in view of the unconstitutional reorganization in

1968 which resulted in the very school districts before

the Court as parties. A. 71-72. While redistricting pro

posals could be implemented pursuant to existing state

law provisions, the District Court was concerned about

the lack of State Board criteria for determining how to

redistrict and the lack of any final decision by the Board

on how to accomplish the task A. 73. Accordingly, the

District Court determined that any redistricting “ ought to

be dealt with explicitly by State officials” (A. 73):

“ Absent such criteria, we feel that the more proper

course is to create a situation which will not freeze

the district lines by court order, but will create a

framework within which the State can make a

future determination of proper districts for the area,

while insuring that actual desegregation will take

place [in the interim]. A. 73. See also A. 77-78.

4. The District Court, therefore, set up a procedure

which would give state officials the first oportunity to

develop an effective reorganization plan. The Court made

no “ final determination of the organization of the area

and of the lines to be followed in setting up such an

area . . . ” A. 74. Citing Milliken, 418 U.S. at 741-742 and

Hills v. Gautreaux, 425 U.S. 284 (1976), the Court noted

that “ [s]uch decisions are far better left to legislators

and the process of compromise than to the rigors of

judicial determination. 418 U.S. at 744.” A. 75. It added

that “ [d] eterminations of methods of governance, and

13 For example the State Board proposed a redistricting plan

creating five new districts, each with one or more of the existing

districts and one-fifth of Wilmington. A. 69.

20

the day-to-day operations of the schools will be left in the

hands of appropriate local officials. This Court should

have no need to interfere in those decisions, unless they

violate federal law or constitutional provisions.” A. 75.

However, to avoid a stalemate and to insure the elimina

tion of the inter-district segregation found, the District

Court provided for an interim consolidation and interim

board drawn from the local districts to begin planning and

to insure implementation should the State fail to take

prompt and effective action. A. 74, 85. To allow time for

State officials to act with regard to the organizational

structure and for the interim board to plan for necessary

pupil reassignments, the Court stayed portions of its

judgment until September, 1977. A. 97-8. If the State

had not acted by that time under the decree the standby

procedure already underway establishing an interim con

solidated Board was to become fully effective. A. 74-5,

77-8, 85, 87. The Court reiterated that this “ reorgani

zation . . . is effective only in the absence of proper State

action to change it.” A. 75. In its general affirmance of

the remedial framework, the Court of Appeals declared

“ [w]e specifically affirm this governance plan and em

phasize that prompt compliance by the State make action

by the interim board unnecessary.” A. 19.“ 14

14 The Court of Appeals ruling and mandate, entered by the

District Court on May 19, 1977, directed that the State Board (or

other appropriate State authority) file with the District Court

“within sixty days [of May 18, 1977] a formal report of its efforts

to carry out the mandate of the District Court.” A. 21. In an

opinion issued on August 5, 1977, the District Court noted that the

State Board report, submitted on July 14, “disclosed that the only

concrete measure which had been taken since entry of the Three-

Judge Court remedy order was passage of legislation authorizing

majority to minority voluntary transfers,” which would permit

black students from the Wilmington and DeLa Warr Districts to

enroll in other districts and white students in the other districts

to transfer to Wilmington or DeLa Warr. Evans V. Buchanan,------

F. Supp. ------ (D. Del. Aug. 5, 1977) (C.A. No. 1816-1822) Mimeo

op. at 9.

[Footnote continued on page 21]

21

5. Finally, the District Court evaluated its proposed

remedial framework under the provisions of the Equal

Educational Opportunity Act of 1974, 20 U.S.C. 1701, et

seq. The District Court “ complied fully with the statu

tory requirements applicable here.” A. 94. Of particular

relevance, the Court held that its prior finding on inter

district violations, including the 1968 Act and reorgani

zation, were findings of the racially discriminatory pur

pose and inter-district effect contemplated under 20 U.S.C.

1715 and 1756. A. 96.

REASONS WHY THE WRIT SHOULD BE DENIED

Petitioners’ attempt to reshape the facts and holdings

of this case to fit those of cases in which lower courts

failed to apply proper legal standards does not withstand

scrutiny of the opinions below. The holdings below dealing

both with the nature of the violation and with the appro

priate standards for framing a remedy are in accord with

applicable decisions of this Court and are a manifestly

correct application of those decisions. In this case the

Three-Judge Court made the detailed factual inquiry and

by specific fact findings traced the history of the inter- 14

14 [Continued]

The District Court found this action a totally ineffective remedy

as only a small portion of the black students and almost no white

students had exercised this option. The Court further found the

State Board’s additional proposal of “ reverse voluntarism” , under

which all Wilmington black students would be assigned to suburban

districts in northern New Castle County with the absolute right to

remain in or return to black schools in Wilmington, to be proced-

urally flawed, substantively ineffective and racially inequitable.

Having found the State Board in default, the District Court viewed

its responsibility under the Third Circuit mandate as requiring

the State Board to appoint a five-member New Board charged

with the duty of planning and implementing a single-district remedy.

In doing so, however, the District Court stayed the requirement

that desegregation at the high school level begin in September, 1977,

pending this Court’s disposition of the present Petitions for Cer

tiorari.

22

district violation and the extent of its effects. Applying

proper legal standards, the Three-Judge Court then pro

vided for a remedy limited to the scope of the violation

and that would intrude on legitimate State and local au

thority as little as possible. The Court of Appeals care

fully reviewed these findings and the record evidence in

light of the applicable legal standards, rather than sub

stituting its judgment for that of the District Court, and

affirmed with modifications the Interim Remedy Ruling.

Accordingly, the Third Circuit’s judgment presents no

new or important issue worthy of review.

1. Violation. The Petitioners’ attack on the 1975 viola

tion holdings of the District Court consists of two well-

rehearsed claims. The first is that the District Court’s

findings of “ significant governmental involvement in inter

district discrimination” (393 F. Supp. at 447) were not

supported by a showing of racial intent. (State Bd. Pet.,

p. 15). The second is that the Court’s finding that the

Educational Advancement Act of 1968 and reorganization

unconstitutionally excluded Wilmington contained a spe

cific negation of discriminatory intent. (State Bd. Pet.,

p. 15).

a. In the Statement, supra, pp. 10-15, we have sum

marized the detailed nature of the District Court’s

findings concerning each of these assertions. The holding

of significant governmental involvement in inter-district

discrimination was not simply conclusory, but was based

on a series of specific findings concerning public acts of

deliberate discrimination. Statement, pp. 10-15. These

acts clearly meet the standards of racial purpose estab

lished by this Court in Keyes v. School District No. 1,

and reaffirmed in Washington v. Davis, Village of Ar

lington Heights V. MHDC, and Dayton Board of Educa

tion v. Brinkman. Unlike the racial imbalance and recis-

sion of a voluntary plan findings in Dayton, the govern

mental practices found by the District Court here were

23

not arguably racially neutral or the results adventitious.

The District Court also recognized that under Milliken

findings of purposeful segregation alone would not be

sufficient to sustain an inter-district remedy absent proof

of inter-district eifect. Applying Milliken standards to

determine the inter-district impact of the violation, the

Court found these acts a proximate cause of the existing

disparity in enrollments between Wilmington and sub

urban New Castle County school districts, 393 F. Supp.

at 438.

After carefully assessing the evidence, the District Court

found that the deliberate acts of discrimination of govern

ment officials, wholly apart from the Educational Ad

vancement Act of 1968 and reorganization, met the

standards for an inter-district violation set down in Mil

liken in that (1) the discriminatory acts of school of

ficials in Wilmington were a constitutional violation that

produced a significant segregative effect in other districts

(418 U.S. at 745) ; and (2) the purposeful racially dis

criminatory use of State housing laws had contributed

to the separation of the races in schools throughout

northern New Castle County (418 U.S. at 755, Stewart,

J., concurring). The District Court also determined

pursuant to Milliken (418 U.S. at 744-745) that these

and other acts, regardless of purpose, served to perpetuate

rather than to dismantle the historic arrangement for

inter-district segregation.15

15 These finding's are to be sharply distinguished from those of

lower courts in Detroit and Eichmond where there were no findings

of inter-district violations significantly affecting the racial composi

tion of schools in either metropolitan area. In Detroit, the lower

court findings focussed only on violations and effects within the

Detroit School District. Milliken V. Bradley, 418 U.S. at 744-51.

In Eichmond, racially discriminatory acts were not found to have

contributed to the disparity in pupil enrollments between the

historically separate Eichmond, Henrico and Chesterfield school

districts. Bradley v. School Board of City of Richmond, Virginia,

462 F.2d 1058, 1065-66 (1972).

24

b. Petitioners’ other claim as to violation is their re

newed assault upon the District Court’s holding that the

1968 Act and reorganization unconstitutionally excluded

Wilmington from consolidation. This claim, of course,

was necessarily disposed of in this Court’s summary af

firmance of the Three-Judge court opinion holding the

Act unconstitutional.16 While this Court is always free

to reexamine its prior judgments, it will do so only in

unusual circumstances. See, e.g., Insurance Group v.

Denver and Rio Grande Western R. Co., 329 U.S. 607,

611-612 (1946). The Petitioners’ well-rehearsed conten

tion that the District Court’s holding of unconstitution

ality was defective for a lack of finding of racially dis

criminatory purpose presents no such circumstances be

cause the contention lacks merit.

First, given the District Court’s findings of an his

toric arrangement for inter-district segregation, a fail

ure to eliminate the vestiges of the State system for im

posing segregation and the continuing acts of discrimina

tion in the two decades after Brown, the remedial stand

ard of the Emporia and Scotland Neck cases are ap

plicable. The issue was whether the 1968 Act and re

organization maintained or effectively dismantled the

prior and continuing inter-district segregation in New

Castle County. See, 407 U.S. at 451, 460; 407 U.S. at

489-490. In such circumstances, there was “no need to

find [the 1968 Act] an independent constitutional viola

16 Whatever the precedential meaning of such a. summary affirm

ance for future cases (see, Edelman v. Jordan, 415 U.S. 651, 670-

671 (1974), it is a decision on the merits dispositive of the inter-

district liability issue in this, the same case. Hicks v. Miranda, 422

U.S. 332, 344 (1975). Even if the scope of prior review was limited

to whether the interlocutory relief ordered was an abuse of discre

tion, the summary affirmance is still properly regarded as dispositive

since it would have been a clear abuse of discretion for the District

Court to order planning for inter-district desegregation if there

were not a substantial inter-district violation.

25

tion.” Washington V. Davis, 426 U.S. 229, 243, quoting

from Emporia, 407 U.S. at 459.

Second, as set forth in the Statement, supra, pp. 13-14,

the District Court found the 1968 Act and reorganiza

tion an independent constitutional violation after a care

ful analysis of “the totality of the relevant facts.” Wash

ington v. Davis, 426 U.S. at 229, 242. The District Court

“quite properly undertook to examine the constitutionality

of the [Act] in terms of its ‘immediate objective’ and its

‘historical’ context and the conditions existing prior to

its enactment.” Reitman v. Mulkey, 387 U.S. 369, 373

(1967). See, Village of Arlington Heights v. MHDC, 97

S. Ct. 555, 564-5. Having conducted this examination

the Court found that the Act was a “racial classification”

of the kind invalidated by this Court in Hunter v. Erick

son, 393 U.S. 385, in that it treated racial problems

differently from related governmental interests.17 Cf.

Lee v. Nyquist, 318 F. Supp. 710 (W.D.N.Y. 1970), aff’d,

402 U.S. 935 (1971). It thus found that plaintiffs had

made out a prima facie case of unconstitutional racial

discrimination, not just disproportionate racial “ impact” .

The District Court therefore shifted “ the burden of proof”

to the defendants to justify the 1968 Act and reorganiza

tion. Id. The District Court’s finding that on balance

the justifications proffered by Appellants were insufficient

17 The Education Advancement Act reorganized Wilmington along

its existing lines and singled it out for exclusion from consideration

at a time when: (a) the dual system within Wilmington’s borders

had not yet been fully dismantled; (b) the Wilmington system,

which contained nearly half the black children in the State had

become identifiably black especially in contrast with surrounding

suburban New Castle County districts; (c) racially discriminatory

State policies had excluded black people from suburban New Castle

County and contributed to the development of identifiably white

schools; and (d) the effects of the historic inter-district system of

segregation between Wilmington and suburban New Castle County

school districts persisted. All of this was part of the “historical

context and the conditions existing prior to enactment.”

26

to rebut the prima facie case and that portions, of the

1968 Act and reorganization amounted to “ invidious dis

crimination” (393 F. Supp. at 446 n. 36) was squarely

the result of the “ sensitive inquiry” called for by Arling

ton Heights to determine whether “ invidious discrimina

tory purpose was a motivating factor.” 97 S. Ct. at

564.18 See also Castaneda V. Partida, 45 L.W. 4302 (23

March 1977). Thus, it is manifest that the District

Court’s analysis and judgment of the 1968 Act and re

organization were not based or “trigger [ed] ” “ solely” on

“ racially disproportionate impact,” Washington v. Davis,

18 While the District Court used the phrase “ invidious dis

crimination” rather than “ racially discriminatory purpose” , this

semantic distinction is of no moment. Nor is it of moment that

the District Court stated that it could not conclude “that the pro

visions excluding the Wilmington District from school reorganiza

tion were purposefully racially discriminatory.” 393 F. Supp. at 439.

In making this statement, the District Court was referring to

the dominant “ subjective intent of the decisionmaker,” Washington

V. Davis, 426 U.S. 229, 252 (Stevens, J., concurring), Dayton

Board of Education, 45 U.S.L.W. at 4910, 4915 (Stevens, J., con

curring), and not a “purpose” or “ intent” of the 1968 Act and

reorganization in the Washington or Keyes sense. The District

Court made clear that its judgment on the 1968 Act and reorgani

zation included a finding of racially discriminatory or segregative

“purpose” or “ intent” in this sense when applying the provisions

of 20 U.S.C. 1715 and 1756 to the case. A. 96. Statement, supra

note 9. As with many State actions, the purposes of the 1968

Act and reorganization were diverse; here, however, one of the

purposes was racial discrimination, “maintaining the racial identi-

fiability of Wilmington and the suburban New Castle County school

districts.” 393 F. Supp. at 495. Compare, Keyes, V. School District

No. 1 , 413 U.S. 189, 210-214, where this Court noted that a State

action “to . . . maintain” segregated schooling is de jure if “ segre

gative intent” is “ among the factors” that motivated the action in

question. See, also, Arlington Heights, where this Court said that

“ [rjarely can it be said that a legislature or administrative body

operating under a broad mandate made a decision motivated solely

by a single concern or even that a particular purpose was the

‘dominant’ or ‘primary’ one” , and, quoting McGinnis v. Royster,

410 U.S. 263, 276-277 (1973), “ [1]egislation is often multi-purposed;

the removal of even a ‘subordinate’ purpose may shift altogether

the consensus of legislative judgment supporting the statute.”

27

426 U.S. 229, 239-242. To the contrary, they adhered

to the substance of this Court’s subsequent opinions in

Washington and Arlington Heights.

Accordingly, the District Court had ample basis for

concluding that a further standard for establishing an

inter-district violation set down in Milliken had been

met, i.e., that district lines had been drawn to frustrate

the “process of dismantling a dual school system” , 418

U.S. at 744, “deliberately . . . on the basis of race” , 418

U.S. at 745, and so as to contribute to the separation of

the races by drawing or redrawing school district lines” ,

418 U.S. at 755 (Stewart, J., concurring). See State

ment, supra, pp. 13-15.

In sum, the District Court’s findings with respect to

violation fully accord with the standards of racial pur

pose or intent set down by this Court in Keyes, Wash

ington, Arlington Heights and Dayton and with the stand

ards for determining inter-district violations set down in

Milliken.

2. Remedy. The petitioners’ attack on the remedial

framework adopted by the District Court and affirmed

with modifications by the Court of Appeals, while posed

in the most amorphous terms (see e.g., State Pet. pp. 16-

18), appears to be an assault on the lower courts’ delinea

tion of the geographic area in which the remedy was to

take place and upon the framework for governance. In

both instances, the petitioners’ claims lack merit.

a. The District Court, having found a substantial

inter-district violation significantly contributing to the

existing racial disparity between Wilmington and subur

ban New Castle County school districts (393 F. Supp.

at 438, 445), then properly invited the parties to submit

desegregation alternatives and evidence and arguments

in support of any plan limiting the extent and geo

graphical scope of an appropriate remedy. See State

28

ment, supra, p. 16. Although under the principles of

Keyes, 413 TJ.S. 189, 208-209, and Sivann, 402 TJ.S. at

26, the burden clearly rested with the defendants to

justify the exclusion of any segregated area of northern

New Castle County as not being the product of segrega

tive intent or the reciprocal effect of the deliberate viola

tion already established, the defendants again failed to

sustain their burden in view of the weight of the record

evidence. See Statement, supra, pp. 16-18. The District

Court had ample basis to conclude as it did that the

racially discriminatory acts of the State and its subdi

visions were “ a substantial and proximate cause of the

existing disparity in racial enrollments in northern New

Castle County.” A. 52-3. Because of the area-wide im

pact of the violation, the District Court, affirmed by the

Court of Appeals, properly required an equally extensive

area-wide remedy.19 See Dayton v. Board of Education,

45 U.S.L.W. at 4914.

This delineation of the appropriate geographical area

for remedy left open the issue of the precise plan for

reassignment and on this question, the District Court pro

posed as a guide, a broad, flexible “ starting point” ratio

specifically modeled after that approved in Swann, 402

TJ.S. at 24-26. The Court of Appeals, however, disap

proved of this portion of the opinion. Statement, supra,

p. 17. Accordingly, the Court of Appeals opinion makes

it clear that the plan for pupil reassignment does not

19 The Newark School District apparently believes that the Court

of Appeals, despite the limited scope of review, was under an obli

gation to explain in its Opinion why the District Court findings

with regard to Newark were not in error (Newark Pet., p. 3).

But no basis is offered for the suggestion that the Court of Appeals,

in affirming the principal finding of area-wide impact of the vio

lation, did not consider all arguments relating to the subsidiary

finding that Newark was properly included because “constitutional

violations existed at the State level and . . . the effects of the pre-

Brown segregation to which Newark was a party have not yet been

dissipated.” A. 80.

29

require racial balance or an application to individual

schools of a remedy which goes beyond the scope of the

violation. See, Statement, pp. 17-18 and footnote 12.

See, also, Keyes v. School Board, No-. 1 of Denver, 413

U.S. 189; Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg School Board,

402 U.S. 1; and Dayton Board of Education v. Brinkman,

45 U.S.L.W. 4910, 4914.

b. As to the organizational structure of the remedy,

the District Court considered three differing approaches

presented in the plans: inter-district transfers utilizing

existing districts, redistricting and redrawing boundary

lines, and consolidation. See Statement, supra, pp. 18-19.

The District Court’s decision to provide a framework for

consolidation came only after a careful evaluation of the

burdens and inconveniences of each alternative. See State

ment, supra, pp. 18-19. Guided by this Court’s admonitions

in Milliken to avoid as far as possible judicial entangle

ment in policy-making or the day-to-day administrative

responsibilities of school authorities, 418 U.S. at 744, the

District Court found that to prescribe redistricting or

inter-district transfers would require the Court either to

make difficult policy judgments (A. 73, 77-8) or to re

solve day-to-day administrative disputes between school

districts (A. 66-8). In contrast, in providing a frame

work for consolidation (pursuant to existing State law

provisions as far as possible and subject to such reorgani

zation and restructuring as the State may enact), the

District Court need not intervene further in the operation

of the schools. A. 75.

Thus, the District Court chose as a standby, the orga

nizational structure requiring the least judicial inter

vention, invited the State to substitute its own organiza

tional structure (A. 75) and delayed and staggered imple

mentation over a two-year period to give the State time

to act and to permit cooperation and effective planning

by all concerned. In its specific affirmance of this gov

30

ernance framework, the Court of Appeals emphasized

that prompt compliance by the State would make action

by the interim board unnecessary (A. 19) and provided

the State with yet another opportunity to shape the

organizational structure by vesting it with responsibility

to appoint a new board even after default. A. 21.

Petitioners nowhere specify in what respect this care

ful deference to State authority runs afoul of principles

declared by this Court in Milliken or other cases, and it

is difficult to imagine how the courts below could have

proceeded more scrupulously to afford the State Board

the widest scope for fulfilling its “duty to prescribe ap

propriate remedies.” Milliken at 744.

* * * *

In sum Petitioners have failed totally to demonstrate

any departure by the courts below from this Court’s stand

ards for determining violations and the appropriate scope

of remedy. To the contrary, the opinions below reveal

scrupulous attention to the standards of this Court and

careful findings of fact after extensive evidentiary hear

ings on each relevant issue. Nor do the Petitions demon

strate any novel issue of law or conflict among the Cir

cuits. Rather, Petitioners’ requests for certiorari appear

to be predicated on the notion that a new decision by this

Court standing by itself is a sufficient reason for invoking

full review of all lower court school desegregation deci

sions, for reexamining issues previously decided, and for

substituting the judgment of this Court for that of the

lower courts. Such a proposition is without any basis. If

embraced in a case such as this where remedy has been

so long delayed, far from promoting the orderly adminis

tration of justice, it would serve to undermine the consti

tutional entitlement of black children under Alexander v.

Holmes County Board of Education, 396 U.S. 19 (1969)

and Carter V. West Feliciana Parish School Board; 396

U.S. 226; 290 (1969) to timely relief.

31

CONCLUSION

Wherefore, for the foregoing reasons, the Petition for a

Writ of Certiorari should be denied forthwith.

Respectfully submitted,

Louis L. Redding

1200 Farmers Bank Building

Wilmington, Delaware 19801

Irving Morris

Joseph A. Rosenthal

Morris & Rosenthal

301 Market Tower Building

Wilmington, Delaware 19899

Richard A llen Paul

Paul & Lukoff

1700 Wilmington Tower

Wilmington, Delaware 19801

Louis R. Lucas

Ratner, Sugarmon, Lucas,

Salky & Henderson

525 Commerce Title Building

Memphis, Tennessee 38101

Paul Dimond

O’Brien, Moran & Dimond

210 East Huron Street

Ann Harbor, Michigan 48108

W illiam L. Taylor

Catholic University Law School

Washington, D.C. 20064

Counsel for Respondents