Memorandum from Ganucheau (Clerk) to All Counsel of Record

Public Court Documents

December 20, 1989

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Chisom Hardbacks. Memorandum from Ganucheau (Clerk) to All Counsel of Record, 1989. e59b3395-f611-ef11-9f8a-6045bddc4804. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c0d713fd-f9d2-45ea-9df4-207b70deeb5b/memorandum-from-ganucheau-clerk-to-all-counsel-of-record. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

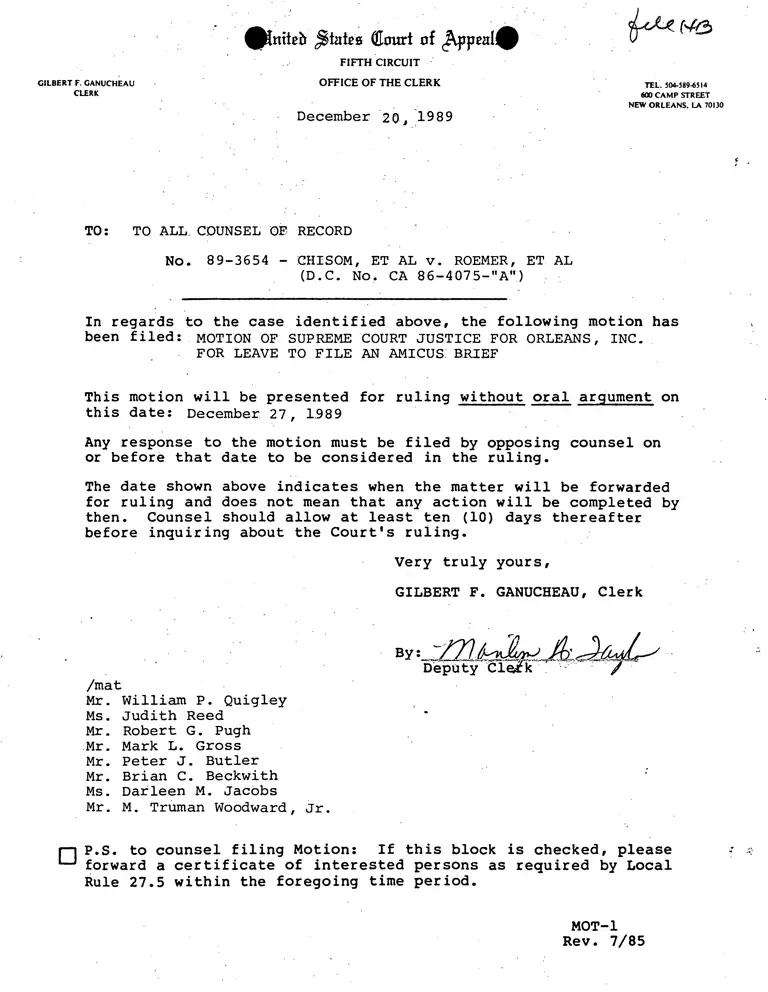

eniteb tees Court of cilypeatO

FIFTH CIRCUIT •

GILBERT F. GANUCHEAU

CLERK

OFFICE OF THE CLERK

December 20, 1989

TO: TO ALL COUNSEL OF RECORD

No. 89-3654 - CHISOM, ET AL v. ROEMER, ET AL

(D.C. No. CA 86-4075-"A")

TEL. 504-589-6514

600 CAMP STREET

NEW ORLEANS. LA 70130

In regards to the case identified above, the following motion has

been filed: MOTION OF SUPREME COURT JUSTICE FOR ORLEANS, INC.

FOR LEAVE TO FILE AN AMICUS BRIEF

This motion will be presented for ruling without oral argument on

this date: December. 27, 1989

Any response to the motion must be filed by opposing counsel on

or before that date to be considered in the ruling.

The date shown above indicates when the matter will be forwarded

for ruling and does not mean that any action will be completed by

then. Counsel should allow at least ten (10) days thereafter

before inquiring about the Court's ruling.

Very truly yours,

GILBERT F. GANUCHEAU, Clerk

By:

/mat

Mr. William P. Quigley

Ms. Judith Reed

Mr. Robert G. Pugh

Mr. Mark L. Gross

Mr. Peter J. Butler

Mr. Brian C. Beckwith

Ms. Darleen M. Jacobs

Mr. M. Truman Woodward, Jr.

D P.S. to counsel filing Motion: If this block is checked, please

forward a certificate of interested persons as required by Local

Rule 27.5 within the foregoing time period.

MOT-1

Rev. 7/85