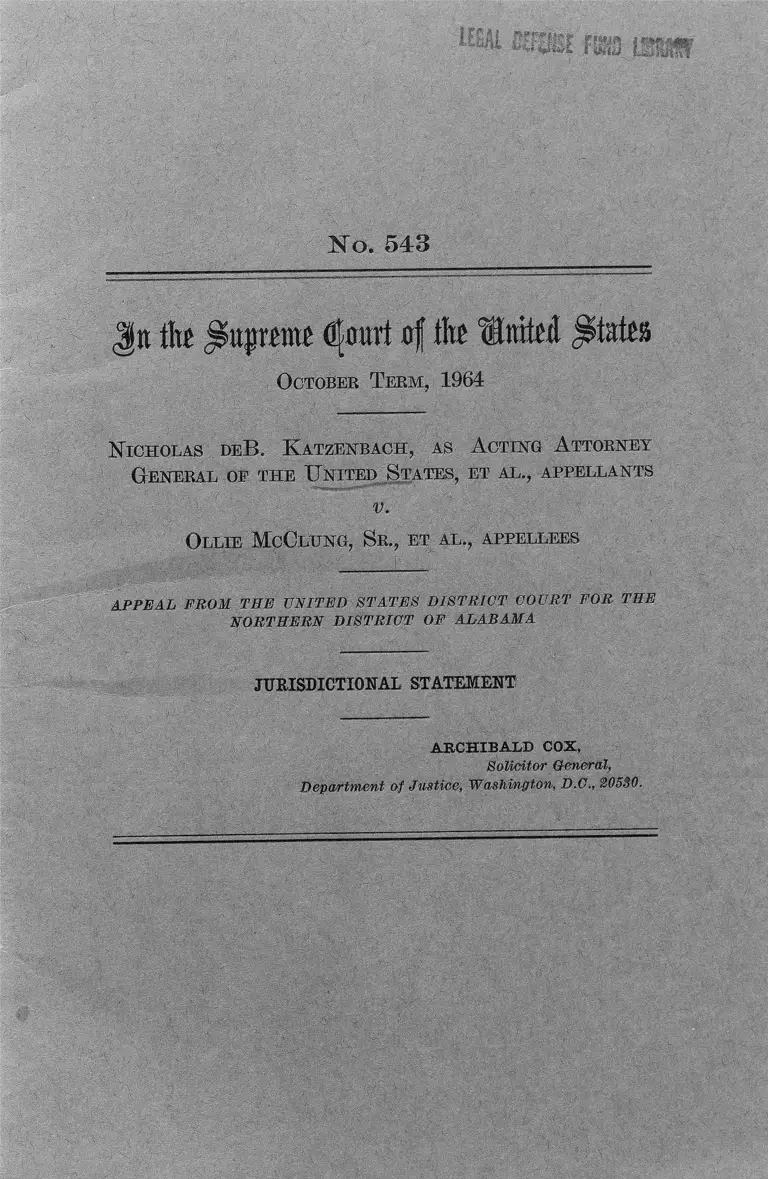

Katzenbach v. McClung Jurisdictional Statement

Public Court Documents

September 17, 1964

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Katzenbach v. McClung Jurisdictional Statement, 1964. 0529fa9c-b99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c0fb556b-bca6-4f56-a2e6-d47d129df634/katzenbach-v-mcclung-jurisdictional-statement. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

O ctober T erm , 1964

N icholas deB. K atzenbach, as A cting A ttorney

General of th e U nited S tates, et al., appellants

v.

Ollie M cClung, S r., et al., appellees

A PP E A L FROM TH E U N ITED S T A T E S D IS T R IC T COURT FO R TH E

N O R T H E R N D IS T R IC T OF A LA B A M A

JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT

A R C H IB A L D COX.

Solicitor General,

D epartm ent o f Justice, W ashington, D.C., 20530.

J tt M^itp ettte fljjmtrt o f the S u ited S ta tes

October T erm , 1964

No. 543

N icholas deB . K atzenbach, as A cting A ttorney

General of th e U nited S tates, et al., appellants

v.

Ollte M cClijng, S r., et al., appellees

A P P E A L FRO M TH E U N ITED S T A T E S D IS T R IC T COURT F O R TH E

N O R T H E R N D IS T R IC T OF A L A B A M A

JURISDICTIONAL STATEMENT

O PIN IO N BELOW

The opinion of the United States District Court

for the Northern District of Alabama (Appendix A,

infra) is not yet reported.

j u r i s d i c t i o n

On September 17, 1964, the three-judge district

court declared unconstitutional that part of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964 (P.L. 88-352, 78 Stat. 241) which

prohibits racial discrimination by any restaurant “if

a substantial portion of the food which it serves * * *

has moved in commerce” (sections 201(a), (b)(2),

(c)(2)), and enjoined the Attorney General and his

(i)

745- 696— 64------ 1

2

subordinates from enforcing the Act against appellees1

restaurant. A notice of appeal to this Court was filed

on September 17, 1964. By order of Mr, Justice

Black, dated September 23, 1964, the injunction has

been stayed.

The jurisdiction of this Court to review the decision

of the district court is conferred by 28 U.S.C. 1252

and 1253.1

CO N STITU TIO N A L A ND STA TU TO R Y PR O V ISIO N S IN V O LV ED

The Commerce Clause of the United States Con

stitution, Article I, sec. 8, cl. 3, and Section 201 of

Title I I of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (P.L. 88-352,

78 Stat. 243) are reproduced in Appendix B, infra.

QUESTIONS PR E SE N T E D

1. Whether the complaint should be dismissed for

want of equity jurisdiction.

2. Whether Title I I of the Civil Rights Act of 1964

is constitutional insofar as it prohibits racial dis

crimination by a restaurant “if * * * a substantial

portion of the food which it serves * * * has moved

in commerce.”

STA TEM EN T

On July 31, 1964, appellees, who operate a restau

rant located in Birmingham, Alabama, filed a complaint

1 Section 1252 authorizes a direct appeal from an interlocutory

or final judgment holding an act of Congress unconstitutional.

Section 1253 authorizes an appeal to this Court from an inter

locutory or permanent injunction entered by a three-judge court.

The decree herein is an interlocutory judgment or injunction,

rather than a temporary restraining order; it is not limited to

ten days (see F.R. Civ. Proc., Rule 65(b)), but is to continue in

effect until further order of the district court.

3

in the district court challenging the constitutionality

of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 insofar as it prohibits

racial discrimination or segregation by restaurants.

The complaint sought an injunction restraining the

Attorney General and his subordinates from enforcing

the Act against appellees’ establishment. On August

4, 1964, pursuant to 28 U.S.C. 2282, a three-judge dis

trict court was designated to hear and determine the

ease. Appellants moved to dismiss on August 19,

1964, and the case was heard on September 1, 1964

On September 17, 1964, the court denied the Govern

ment’s motion to dismiss, declared the challenged pro

visions unconstitutional as applied to appellees’ res

taurant, and granted appellees’ prayer for a pre

liminary injunction.

The gravamen of the complaint is that appellees’

business is “essentially local in character. ” Appellees

alleged that all of their food purchases are made

“within the State of Alabama;” that the operation of

the restaurant “in no way affects commerce” despite

the fact that “some of the food served by [their res

taurant] probably originates in some form outside the

State of Alabama;” and that the restaurant does not

serve interstate travelers. The complaint claimed that,

as applied to appellees, the Act was unconstitutional,

in that it exceeded the power of Congress to regulate

commerce among the several states; deprived appellees

of property without due process of law contrary to

the Fifth Amendment; subjected them to involuntary

servitude prohibited by the Thirteenth Amendment;

was “in contravention of natural law;” and violated

4

the Tenth Amendment. An amendment to the com

plaint raised the additional objection that the statute

contravened appellees’ rights guaranteed by the First

Amendment. I t was further claimed that a genuine

threat existed that, unless enjoined and restrained, the

Attorney General would seek to enforce the Act

against appellants to their irreparable and serious

injury, in an amount far in excess of $10,000.

The government’s motion to dismiss asserted that

no “ case or controversy” was presented within the

meaning of Article I I I of the Constitution; that ap

pellees were not threatened with any injury suffi

cient to justify the exercise of equity jurisdiction;

that appellees had an adequate remedy at law by

way of a defense to any enforcement proceeding

which might be brought against t hem under Title I I

of the 1964 Act; and that, in any event, the Act is

constitutional.

The holding of the district court that the challenged

provision was invalid was premised upon its view

that, although a substantial portion of the food served

by the restaurant is obtained through interstate chan

nels, it comes to rest before being sold by the restau

rant and hence is no longer subject to federal regula

tion under the Commerce Clause.

T H E QUESTIONS A B E SU B STA N TIA E

The issues presented by this appeal are of obvious

importance.

The threshold issue is whether equity jurisdiction

may be invoked in the absence of enforcement pro

ceedings to draw in question the validity of this

5

federal statute at the instance of any proprietor who

might be covered by its terms, despite the fact that

neither criminal prosecution nor money damages are

provided for in the Act and there is accordingly no

threat of any legal injury.

The second issue is the constitutionality of a statute

which has undeniable significance for the Nation and

was enacted at “ the culmination of one of the most

thorough debates in the history of Congress.” Mr.

Justice Black, opinion denying application for a stay,

Heart of Atlanta Motel v. United States, O.T. 1964,

August 10, 1964.

In granting a stay of the district court’s injunc

tion entered in the instant case, Mr. Justice Black

declared that the issues are “ important” and that

“ their final determination should not be unnecessarily

delayed.” He also indicated that the Court is pre

pared to set the case down for argument immediately

following the related Heart of Atlanta case, which is

scheduled to be heard on October 5, 1964. We be

lieve it unnecessary in these circumstances to labor

the obvious proposition that the case is one of high

importance' and merits plenary consideration.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, it is respectfully sub

mitted that probable jurisdiction should be noted.

Archibald Cox,

Solicitor General.

October 1964.

APPENDIX A

In the United States District Court for the Northern

District of Alabama, Southern Division

Civil Action No. 61-448

Ollie M cClung, Sr., and Ollie M cC lung, J r.,

PLAINTIFFS

V S .

N icholas deB . K atzenbach , as A cting A ttorney

General of the U nited S tates of A merica, et al.,

DEFENDANTS

In conformity with the per curiam opinion of this

court, contemporaneously entered herewith:

I t is Ordered, A djudged and D ecreed by the court

that the defendant, Nicholas deB. Katzenbach, as Act

ing Attorney General of the United States of Amer

ica, and his agents, servants, employees, successors in

office and those in concert with him who shall receive

notice of this order, be and they are hereby tem

porarily restrained and enjoined from enforcing the

provisions of title I I of the Civil Rights Act of 1964

against plaintiffs, Ollie McClung, Sr. and Ollie Mc-

Clung, Jr., as partners operating a restaurant under

the trade name “Ollie’s Barbecue” at 902 7th Avenue

South, in Birmingham, until further order of this

court.

(7)

8

Done, this the 17th day of September 1964.

W alter P. Gravin',

Circuit Judge.

Seybourn H . L ynne ,

District Judge.

H. H. Grooms,

District Judge.

[Caption omitted]

In conformity Avith the per curiam opinion of this

court, contemporaneously entered herewith:

I t is Ordered, Adjudged and D ecreed by the court

that the m otion in behalf of defendan ts to dism iss the

complaint h ere in be and the same is hereby overruled .

Done, this the 17th day of September 1964.

W alter P. Geavin,

Circuit Judge.

Seybourn H. L ynne ,

District Judge.

H. H. Grooms,

District Judge.

9

[Caption omitted]

Before (Jewin ', Circuit Judge, and L ynne and

Grooms, District Judges.

P er Cu r ia m : This is a suit by the owners and

operators of a restaurant business in Birmingham,

Alabama, seeking to enjoin the enforcement of the

provisions of title I I of the Civil Rights Act of 19641

on the ground that they are unconstitutional. A stat

utory three-judge court was convened pursuant to 28

U.S.C.A. § 2282, and the case was set down for hear

ing on September 1, 1964, on plaintiffs’ prayer for a

temporary injunction. P rio r . to the hearing the

defendants moved to dismiss the complaint on the

separate grounds that (1) the court lacks jurisdiction

over defendant Robert F. Kennedy2 as Attorney Gen

eral of the United States, because of insufficient

service of process; (2) since defendant Robert F.

Kennedy is an indispensable party, the insufficiency

of service of process upon him renders co-defendant

Macon L. Weaver, United States Attorney for the

Northern District of Alabama, an improper party

defendant; (3) the complaint fails to state a claim

upon which relief can be granted; and, (4) the court

lacks equitable jurisdiction because plaintiffs have an

adequate remedy at law. This motion was heard by

and submitted to the full court on briefs and oral

argument of counsel on September 1, 1964, and was

taken along with plaintiff’s prayer for a temporary

injunction.

1 Public Law 88-352; 78 Stat. 241.

2 Since Robert F. Kennedy tendered his resignation as Attor

ney General of the United States, which was accepted after

submission of this case to the court and since Nicholas deB.

Katzenbach has been appointed Acting Attorney General of

the United States, the said Katzenbach is hereby substituted,

in his official capacity, for the said Kennedy as a party de

fendant, as provided by Rule 25(d) (1) Fed. R. Civ. P.

745- 696— 64---------- 2

10

T H E M OTION TO D ISM ISS

The first two grounds for dismissal, both based upon

the theory that service of process upon the Attorney

General was defective, are no longer in issue. Service

of process upon the Attorney General was made

initially by certified mail in accordance with the pro

visions of 28 U.S.C.A. § 1391(e), and defendants con

tended that because fictitious parties were joined as

defendants the provisions of section 1391(e) were in

applicable. Thereafter, plaintiffs amended their com

plaint by striking and dismissing therefrom the un

served fictitious parties and caused the complaint as

amended to be re-served upon the Attorney General

under section 1391(e). I t was conceded by counsel

for defendants on argument that the first two grounds

in their motion to dismiss were thereby eliminated

and accordingly are considered abandoned.

Defendants have also insisted in their brief and oral

argument that the complaint does not present an

actual controversy between the parties and that the

adequacy of legal remedies deprives this court of

equitable jurisdiction. These grounds were argued

in the hearing on plaintiffs’ prayer for temporary in

junction at which evidence was adduced developing

the undisputed facts set out below.3

31. Plaintiffs are partners operating a restaurant under the

trade style “Ollie’s Barbecue” at 902 Seventh Avenue South,

in Birmingham.

2. The plaintiffs’ family has operated such restaurant under

the same name and at the same location since 1927.

3. Plaintiffs’ restaurant specializes in barbecued meats and

homemade pies; approximately 90 to 95 per cent of its sales

consist of such items and nonalcoholic beverages.

4. Plaintiffs’ restaurant, when filled to capacity, will seat

approximately 220 persons; its trade is derived from local

regular customers who are for the most part known to the

11

Contending that there has not been a sufficient show

ing of a specific threat of immediate enforcement of

title I I of the act as to the plaintiffs, defendants insist

plaintiffs; its trade is predominantly composed of white col

lar business people and family groups. Plaintiffs feature in

their restaurant a wholesome atmosphere in which no profanity

or consumption of alcoholic beverages is allowed. The restau

rant is closed on Sunday. Plaintiffs have in the past declined

service to persons who have been profane and have given the

appearance of drinking alcoholic beverages.

5. Plaintiffs’ restaurant is located in an area of Birming

ham in which are located primarily residences occupied by

Negroes and light industrial development; in the nearby vi

cinity are several Negro churches and schools attended by

Negro children.

6. The restaurant is eleven blocks from the nearest inter

state highway, a somewhat greater distance from the nearest

railroad station and bus station and between six and eight

miles from the nearest airport.

7. Plaintiffs seek no transient trade and do no advertising

of any kind except for the maintenance of a sign on their

own premises. To their knowledge plaintiffs serve no inter

state travelers.

8. In the twelve months preceding the passage of the Civil

Bights Act of 1964, plaintiffs purchased approximately $150,-

000 worth of food, all locally. Approximately 55 per cent

of this was for meat and between 80 and 90 per cent of the

meat purchases were from George A. Hormel & Company, at

its Birmingham branch. Its purchases from Hormel for that

period were shown to be $69,788. All of the meat purchased

from Hormel was shipped to its Birmingham branch from out

side the State of Alabama.

9. Plaintiffs employ 36 persons a t their restaurant, approxi

mately two-thirds of whom are Negro. Plaintiffs personally

prepare food and serve customers. Plaintiffs and some of their

employees would not voluntarily serve meals to Negroes.

10. Since July 2, 1964, plaintiffs have not complied with the

Civil Bights Act of 1964; they have, in fact, on more than one

occasion, refused service to Negroes on an equal basis with

12

alternatively that it is not alleged that defendants

either have instituted enforcement proceedings against

the plaintiffs or have conducted an investigation to de

termine whether plaintiffs have violated the act, and

that insufficient facts are alleged to bring the plain

tiffs within the coverage of the act.

In urging that the allegations are insufficient to

show coverage, defendants point first to averments in

the complaint respecting the remoteness of plaintiffs’

business from any place normally frequented by inter

state travelers, the absence of any advertising by

them and the averment that to their knowledge they

serve no “interstate travelers” as that term is used

in the act. I t is true that these allegations, substan

tiated by evidence at the hearing, tend strongly to

indicate an absence of coverage under title I I insofar

as it relates to a restaurant which “serves or offers to

serve interstate travelers,” and defendants have made

no contention that they are covered by virtue of that

part of the act.

Defendants then seize upon the averment that

“some” of the food served in plaintiffs’ restaurant

originated in some form outside of Alabama. This

use of the word “ some”, say defendants, is insufficient

because the act uses the term “substantial” in defin

ing the portion of a restaurant’s food which must

move in commerce in order that it be within the al-

white customers and on such occasions plaintiffs have been

in actual violation of the act.

11. Because of their location and the manner of conducting

their business, plaintiffs would lose a substantial amount of

business if forced to serve Negroes in their restaurant. From

its beginning, plaintiffs’ restaurant has served only white trade.

12. A substantial portion of the food served in plaintiffs’

restaurant has moved in commerce and plaintiffs have, since

July 2, been in violation of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.

13

ternative criterion of coverage prescribed by section

201(e)(2). We are of the opinion that the meaning

of the term “ substantial” as there used must and

can only be determined judicially, and we conclude

as a matter of law, on the basis of objective evidence,

that a “ substantial” portion of the food served by

plaintiffs has moved in commerce within the meaning

of the act.

As defendants note, the complaint avers neither

that enforcement proceedings have been instituted

against plaintiffs nor that their restaurant was investi

gated by defendants prior to the commencement of

the action. Plaintiffs do aver that prior to its filing

they had violated the provisions of title I I applicable

to their restaurant by refusing to provide service to

Negroes on the same basis as they provide to their

other customers, and the evidence shows that since

its commencement they have consistently continued

and will continue thus to violate the act. In this re

spect alone the circumstances of this case are quite

different from those existing in the cases urged by

defendants in support of their position that this suit

presents no justiciable controversy.

One of the plaintiffs testified further that he was

caused in large part to institute this action by the

fact that the defendants two days previously had

filed in this court an enforcement suit against other

persons operating restaurants of a similar character,

and it appears from the complaint in that su it4 that

the act’s coverage was invoked in part upon the basis

that a substantial part of their food had moved in

commerce. And plainly the Attorney General has

indicated an intention to enforce the provisions of

title I I as against its violators. We cannot say, in

these circumstances, that enforcement against plain

4 Civil Action No. 64-443, Northern District of Alabama.

14

tiffs was not reasonably imminent when this action

was commenced, and no case cited by defendants or

found by us has held under comparable circumstances

that for this reason an actual controversy did not

exist.

There are, moreover, many instances in which a

threat of imminent enforcement of a law has not

been considered requisite to the existence of a justici

able controversy or the exercise by federal courts of

equitable jurisdiction in similar suits seeking antici

patory relief from the operation and enforcement

of the law.

In their complaint plaintiffs attack the validity of

title I I of the act in its entirety. The act requires in

positive terms that the plaintiffs, in the operation of

their restaurant, afford to all persons “ the full and

equal enjoyment of the goods, services [and] facili

ties.” Consequently, as to the plaintiffs, title I I

creates a mandatory duty to which it commands im

mediate obedience. As against this, the plaintiffs

contend, and it is the object of this suit to determine,

that they have a constitutional right to operate their

business free of the restrictions now imposed upon it

by the act. They aver, and have shown by evidence,

that these requirements of title I I will cause sub

stantial and irreparable injury to their business.

Thus, the substance of the allegations and proof is

that the provisions of title I I and the duty it imposes

constitute a present injurious inpingement upon the

plaintiffs’ property rights. The existence of a justi

ciable controversy as well as the equitable jurisdiction

of the federal courts and the right to injunctive relief

have been unheld often under similar circumstances.

Euclid v. Ambler Realty Co., 272 U.S. 365 (1926) ;

Pennsylvania v. West Virginia, 262 U.S. 553 (1923) ;

Carter v. Carter Coal Co., 298 U.S. 238 (1936); Pub-

15

lie Utilities Comm’n of California v. United States,

355 U.S. 534 (1958) ; Adler v. Board of Education, 342

U.S. 485 (1952) ; Pierce v. Society of Sisters, 268 U.S.

510 (1925); Currin v. Wallace, 306 U.S. 1 (1939);

Terrace v. Thompson, 263 U.S. 197 (1923) ; Wickard

y. Filburn, 317 U.S. I l l (1942). I t is our considered

opinion that these decisions are controlling upon the

present case and that defendants’ motion to dismiss

the complaint therefore should be overruled.

T H E M E R IT S

Having negotiated the procedural hurdles, we pro

ceed to an examination of title I I of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964:

Section 201. (a) All persons shall be entitled

to the full and equal enjoyment of the goods,

services, facilities, privileges, advantages, and

accommodations of any place of public accom

modation, as defined in this section, without

discrimination or segregation on the ground of

race, color, religion, or national origin.

(b) Each of the following establishments

which serves the public is a place of public

accommodation within the meaning of this title

if its operations affect commerce, or if discrimi

nation or segregation by it is supported by

State action: * * *

* * * * *

(2) any restaurant, cafeteria, lunchroom,

lunch counter, soda fountain, or other fa

cility principally engaged in selling food

for consumption on the premises, including,

but not limited to, any such facility located

on the premises of any retail establishment;

or any gasoline station ;

* * * * *

(c) The operations of an establishment affect

commerce within the meaning of this title if

* * * (2) in the case of an establishment de-

16

scribed in paragraph (2) of subsection (b), it

serves or offers to serve interstate travelers or

a substantial portion of the food which it serves,

or gasoline or other products which it sells, has

moved in commerce. * * *

(Emphasis supplied.)

Contending that the foregoing portions of the act,

as applied to the local business which they operate,

are unconstitutional, plaintiffs insist that when private

establishments within the confines of the respective

states, in the lawful and legitimate exercise of their

private discretion, wish to select their customers there

is no power, under the Constitution, or any of its

amendments, granted to the federal government to

regulate such private accommodations.

The heart of the federal compact beats in the tenth

amendment of the Constitution: “The powers not dele

gated to the United States by the Constitution, nor

prohibited by it to the States, are reserved to the

States respectively, or to the people. ’ ’ Thus it is to the

Constitution and its amendments that we must look

to determine whether Congress possesses the power

it has in this instance sought to exercise.

Insofar as we can determine from a review of the

legislative history of the ac t5 and the extensive de

bates in the Senate relevant to title II,6 the only

three suggested sources of congressional power were

511 U.S. Code Cong. & Ad. News 1727-1891, 88th Cong., 2d

Sess. (July 20, 1964).

6 V Cong. Rec. 4757, 4593-4598, 4643^1655, 4680-4681, 4833-

4835, 4906, 5066-5072, 5091-5104; VI Cong. Rec. 5454-5458,

5539-5543, 5690-5693, 5770-5771, 5851-5855, 5865-5871, 5879-5889,

6003, 6212-6214, 6234-6240; V II Cong. Rec. 6307, 6334-6344,

7039-7041; V III Cong. Rec. 7552-7558, 7677-7684, 7816-7825,

7837-7854, 7966-7967, 8029, 8092, 8371, 8805-8806; IX Cong. Rec.

8849. (1964).

17

the thirteenth amendment, the fourteenth amendment,

and the commerce clause.

At oral argument counsel for defendants forth

rightly stated their opinion that the thirteenth amend

ment was neither authority for nor prohibitory of this

legislation. We agree, thereby rejecting the argu

ment of plaintiffs that the effect of such act is to

impose upon them a condition of involuntary servi

tude in violation of such amendment.7

I t cannot be successfully contended that the above

quoted portions of the act may be constitutionally

applied to these plaintiffs under the grant of legis

lative power contained in the fourteenth amendment8

since it was conceded at oral argument that the State

of Alabama, in none of its manifestations, has been

involved in the private conduct of plaintiffs in refus

ing to serve food to Negroes for consumption on the

premises. Civil Rights Gases, 109 U.S. 3 (1883) ;

Peterson v. Greenville, 373 U.S. 244 (1963).

In any discussion of the commerce clause as a grant

of power to the national government to regulate ac

tivities commonly described as private and local we

keep in mind the admitted fact that a majority of

sincere and conscientious members of Congress be

lieved this legislation to be in the national interest

and necessary to end practices which they consider

debasing to human dignity. Of course, we express

7 Compare: Butler v. Perry, 240 U.S. 328 (1916) ; Brown

Holding Co. v. Feldman, 256 U.S. 170 (1921); State v.

Sprague, 32 U.S.L.Week 2610 (New Hampshire Sup. Ct.

1964); Scheiber, The Thirteenth Amendment and F re e d o m of

Choice m Personal Service Occupations: A Reappraisal, 49 Cor

nell U.Q. 508 (1964).

8 Section 5 thereof reads as follows: “The Congress shall

have power to enforce, by appropriate legislation, the provisions

of this article.” !

18

no opinion as to the wisdom of the legislation and

confine our consideration to the constitutionality of

the provisions with which we are concerned.

The commerce clause, appearing in article 1, sec

tion 8 of the Constitution, reads as follows:

“The Congress shall have Power * * *

* * * * *

“ To regulate Commerce with foreign Na

tions, and among the several States, and with

the Indian Tribes;

* * * * *

* * *—And to make all Laws which shall he

necessary and proper for carrying into Execu

tion the foregoing Powers * *

The language is simple and unadorned. I t has re

mained unchanged since 1789. With reference to it,

to allay popular misgivings as to the nature and ex

tent of powers vested in the Union by the new Consti

tution, James Madison wrote, “The regulation of

commerce, it is true, is a new power; but that seems

to be an addition which few oppose, and from which

no apprehensions are entertained.” 9 And Alexander

Hamilton made it clear that the commerce clause was

intended to restrain the “interfering and unneigh-

borly regulations of some states.” 10 11 In spite of its

simplicity and clarity and because of the constantly

increasing “ interpenetrations of modem society,” 11

it has spawned thousands of eases.

In Civil Rights Cases, 109 U.S. 3 (1883), at page

10, Mr. Justice Bradley characterized section 1 of the

Civil Rights Act of 1875: “Its effect is to declare, that

in all inns, public conveyances and places of amuse

ment, colored citizens, whether formerly slaves or not,

9The Federalist No. 45 (Madison).

10 The Federalist No. 22 (Hamilton).

11 Polish Alliance v. Labor Board, 322 U.S. 643, 650 (1944).

19

and citizens of other races, shall have the same accom

modations and privileges in all inns, public convey

ances, and places of amusement as are enjoyed by

white citizens; and vice versa.” Thereafter, he posed

and answered a question: “ Has Congress constitu

tional power to make such a law? Of course, no one

will contend that the power to pass it was contained

in the Constitution before the adoption of the last

three amendments [thirteenth, fourteenth and fif

teenth].” Since the commerce clause had been in the

Constitution for almost one hundred years and since

we are advised that the Solicitor General in brief had

urged upon the court the sufficiency of its grant of

power to sustain the challenged legislation, Mr. Jus

tice Bradley’s pronouncement is, to say the least,

highly intriguing and might be accorded more than

persuasive authority but for the subsequent statement

in Butts v. Merchants Transp’n Co., 230 U.S. 126

(1913), at page 132:

“The question of the constitutional validity of

those sections came before this court in Civil

Bights Cases, 109 TI.S. 3, and upon full con

sideration it was held (a) that they received

no support from the power of Congress to regu

late interstate commerce because, as is shown

by the preamble and by their terms, they were

not enacted in the exertion of that power * *

While we shall not attempt the impossible task of a

precise delineation of the contours of the power to

regulate interstate commerce granted the Congress or

the Herculean labor of analyzing the multitudinous

cases dealing with various aspects of what may be

termed primary and implied power, we shall make an

effort to distill from the decided eases a definitive

statement of such power which may be applied to this

case only.

20

Some presuppositions are permissible; indeed they

are required by the teaching of Wickard v. Filburn,

317 U.S. 111, 120, “At the beginning Chief Justice

Marshall described the federal commerce power with

a breadth never yet exceeded. Gibbons v. Ogden, 9

Wheat. 1, 194-195.” ; of Swift v. United States, 196

U.S. 375, 398, “* * * commerce among the States is

not a technical legal conception, but a practical one,

drawn from the course of business.” ; of The Pipe

Line Cases, 234 U.S. 548, 560-61, “The control of

Congress over commerce among the States cannot be

made a means of exercising powers not entrusted to

it by the Constitution * * and, of Labor Board v.

Jones be, Laughlin, 301 U.S. 1, 30, “The authority of

the federal government may not be pushed to such

an extreme as to destroy the distinction, which the

commerce clause itself establishes, between commerce

‘among the several States’ and the internal concerns

of a State. That distinction between what is national

and what is local in the activities of commerce is vital

to the maintenance of our federal system.”

Proceeding to explicate our understanding of the

nature and extent of the power with which we are

concerned, it is quite unnecessary to labor the obvious,

that the commerce clause constitutes an express grant

of power to Congress to regulate interstate commerce,

which consists of the movement of persons, goods or

information from one State to another. The eases are

legion sustaining its exercise in this area.12 Its power

12 E.g. United States v. International Boxing Club, 348 U.S.

236 (1955); United States v. Shubert, 348 U.S. 222 (1955);

Radovieh v. National Football League, 352 U.S. 445, 455

(1957); United States v. Frank ford Distilleries, 324 U.S. 293

(1945).

21

is not restricted, however, to the regulation of inter

state commerce. Congress is further invested with

the power to regulate intrastate activities, but only to

the extent that action on its part is necessary or ap

propriate to the effective execution of its expressly

granted power to regulate interstate commerce.

The power of Congress to regulate wholly intra

state activities is brought into play only when those

activities have such a close and substantial relation

to interstate commerce that their control is essential

or appropriate to protect that commerce from prac

tices within a State which burden its freedom or ob

struct its flow.13 14 The exercise of such power must

necessarily be prospective, for the reason, that, unlike

Tennyson’s brook, interstate commerce does not run

on forever. At some time it must come to an end

within the boundaries of some State.11

This century has witnessed a dynamic expansion of

federal control not only of the movements of com

merce between the states but also of intrastate activ

ities which have been found to burden its freedom or

obstruct its flow. Thus Congress has exercised its

power granted by the commerce clause to enact the

13 United States v.. Wrightwood Dairy Go., 315 U.S. 110

(1942); Bethlehem Steel Go. v. New York State Labor Rela

tions Board, 330 U.S. 767 (1947) ; Santa. Cruz Co. y. NLRB,

303 U.S. 453 (1938); Labor Board v. Jones <& Laughlin, 301

U.S. 1 (1937); Edison Go. v. Labor Board, 305 U.S. 197

(1938); Labor Board v. Fainblatt, 306 U.S. 601 (1939); United

States y. Darby, 312 U.S. 100 (1941).

14 Gibbons y. Ogden, 9 Wheat. 1 (1824); Scheater Corp. v.

United States, 295 U.S. 495 (1935); Carter v. Carter Coal Co.,

298 U.S. 238 (1936); Welton v. Missouri, 91 U.S. 275 (1875);

Bowman y. Chicago <$> N. Ry., 125 U.S. 465 (1888); Packer

Corporation v. Utah, 285 U.S. 105 (1932); Florida v. United

States, 282 U.S- 194 (1931); Yonkers v. United States, 320 U.S.

685 (1944); Palmer v. Massachusetts, 308 U.S. 79 (1939).

22

Robinson-Patman Act/5 the Federal Food, Drug and

Cosmetic Act/6 the White Slave Laws/7 the Gambling

Devices Transportation Act/8 the Agricultural Ad

justment Act of 1938/3 the Fair Labor Standards

Act/0 and the National Labor Relations Act/1 among

others.

Concededly, the latter three, in broad extension of

federal control, have immediate, direct, and practical

impacts upon activities which were at one time con

sidered wholly intrastate in nature thus resting in the

domain of state control.

La each instance Congress cautiously made clear

legislative findings that the regulation of the intra

state practices dealt with was necessary or appropri

ate to the effective execution of its expressly granted

power to regulate interstate commerce. In the Na

tional Labor Relations Act such findings are set forth

in 29 U.S.C.A. § 151. Moreover, assurance was given

that regulation of essentially local matters would ap

ply only where there was an actual effect on inter

state commerce by requiring that this be determined

administratively or judicially on a record in each

individual case. 29 U.S.C.A. §§ 159(c) and 160(a).

In the Agricultural Adjustment Act Congress made

elaborate findings to establish an effect on commerce

of the intrastate activities sought to be regulated. 7

U.S.C.A. §§ 1311, 1321, 1331,1341, 1351, 1357, 1379(a),

and 1380.

The Fair Labor Standards Act contains a built-in

limitation on its enforcement by requiring a judicial

15 52 Stat. 446 15 U.S.C.A. § 13(c).

10 52 Stat. 1040, as amended, 21 U.S.C.A. §§ 301-392.

17 36 Stat. 825, as amended, 18 U.S.C.A. §§ 2421-2424.

18 64 Stat. 1134,15 U.S.C.A. §§ 1171-1177.

18 52 Stat. 31, as amended, 7 U.S.C.A. §§ 1281-1407.

20 52 Stat. 1060, as amended, 29 U.S.C.A. §§ 201-219.

2149 Stat. 449, as amended, 29 U.S.C.A. §§ 151-159.

23

determination of the ultimate fact that acts of em

ployers or employees actually affect such commerce

on a case by case basis.

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 contains no legislative

findings and we proceed to a critical examination of

its provisions to determine whether it may neverthe

less successfully survive the constitutional challenge.

I t is our opinion that neither of the three above-

mentioned acts is an apposite analogy and that the

cases arising thereunder afford scant persuasive au

thority beyond the broad principles enunciated

therein.2*

The duty of this court is classically defined in

United States v. Butler, 297 U.S. at pages 62 and 63:

“ There should be no misunderstanding as to

the function of this court in such a case. I t is

sometimes said that the court assumes a power

to overrule or control the action of the people’s

representatives. This is a misconception. The

Constitution is the supreme law of the land

22 That the National Labor Relations Act may not be analo

gized to the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and that the power of

Congress is not plenary with respect to the regulation of activi

ties not themselves interstate commerce is made crystal clear by

Mr. Justice Black’s concurring opinion in Polish Alliance v.

Labor Board, 322 U.S. 643, 652:

“The doctrine that Congress may provide for regulation of

activities not themselves interstate commerce, but merely ‘af

fecting’ such commerce, rests on the premise that in certain

fact situations the federal government may find that regulation

of purely local and intrastate commerce is ‘necessary and

proper’ to prevent injury to interstate commerce * * *. In ap

plying this doctrine to particular situations this Court prop

erly has been cautious, and has required clear findings before

subjecting local business to paramount federal regulation * * *.

I t has insisted upon ‘suitable regard to the principle that

whenever the federal power is exerted within what would

otherwise be the domain of state power, the justification of the

exercise of the federal power must clearly appear.’ * *

24

ordained and established by the people. All

legislation must conform to the principles it

lays down. When an act of Congress is ap

propriately challenged in the courts as not

conforming to the constitutional mandate the

judicial branch of the Government has only

one duty,—to lay the article of the Constitu

tion which is invoked beside the statute which

is challenged and to decide whether the latter

squares with the former. All the court does,

or can do, is to announce its considered judg

ment upon the question. The only power it

has, if such it may be called, is the power of

judgment. This court neither approves no[r]

condemns any legislative policy. Its delicate

and difficult office is to ascertain and declare

whether the legislation is in accordance with,

or in contravention of, the provisions of the

Constitution; and having done that, its duty

ends.

‘ ‘ The question is not what power the Federal

Government ought to have but what powers in

fact have been given by the people. I t hardly

seems necessary to reiterate that ours is a dual

form of government; that in every state there

are two governments,—the state and the United

States. Each State has all governmental pow

ers save such as the people, by their Constitu

tion, have conferred upon the United States,

denied to the States, or reserved to themselves.

The federal union is a government of delegated

powers. I t has only such as are expressly

conferred upon it and such as are reasonably

to be implied from those granted. In this re

spect we differ radically from nations where

all legislative power, without restriction or

limitation, is vested in a parliament or other

legislative body subject to no restrictions except

the discretion of its members.”

Paraphrased, for clarity of discussion, title I I of

the act declares that no restaurant may refuse service

to any person because of his race, color, religion, or

25

national origin either if it serves or offers to serve

interstate travelers or a substantial portion of the

food which it serves has moved in commerce.

No case has been called to our attention, we have

found none, which has held that the national govern

ment has the power to control the conduct of people

on the local level because they may happen to trade

sporadically with persons who may be traveling in

interstate commerce. To the contrary, see Williams

v. Howard Johnson’s Restaurant, 268 F. 2d 845 (4th

Cir. 1959) ; Elizabeth Hospital, Inc. V. Richardson,

269 F. 2d 167 (8th Cir. 1959) ; United States v. Yellow

Cab Co., 332 TJ.S. 218 (1947).

On the authority of the cases collected in footnote

14, infra, we believe it to be a settled rule of consti

tutional law that goods cease to constitute a part of

interstate commerce, and become a part of the general

property in a state, and amenable to its laws, when

they are sent into a state, either for the purpose of

sale or in consequence of a sale. The simple truth

of the matter is that Congress has sought to put an

end to racial discrimination in all restaurants wher

ever situated regardless of whether there is any

demonstrable causal connection between the activity of

the particular restaurant against which enforcement

of the act is sought and interstate commerce.

If our premise is correct, Congress sought to

achieve its end by the sophisticated means of first

declaring a restaurant is a place of public accommo

dation if its operations affect commerce and by there

after abandoning the “affect commerce” requirement

by legislating what is tantamount to a conclusive pre

sumption that its operations do affect commerce if it

is proved either that it serves or offers to serve inter

state travelers or that a substantial portion of the

food which it serves has at some time, however re-

26

mote, moved in commerce. The courts will not sus

tain a presumption when there is “no rational con

nection between the fact proved and the ultimate fact

presumed, if the inference of the one from proof of

the other is arbitrary because of lack of connection

between the two in common experience.’7 Tot v.

United States, 319 U.S. 463, at 6j^-6ji8. The issues

presented in the instant case require our considera

tion of only that portion of the statute relating to res

taurants which serve food “ a substantial portion” of

which “has moved in commerce.”

If Congress has the naked power to do what it has

attempted in title I I of this act, there is no facet of

human behavior which it may not control by mere leg

islative ipse dixit that conduct “affeet[s] commerce”

when in fact it does not do so at all, and rights of the

individual to liberty and property are in dire peril.

We conclude that title I I of the Civil Rights Act of

1964, as applied to the business operated by these

plaintiffs, was beyond the competence of Congress to

enact and that its enforcement against plaintiffs

under the circumstances of this case would be viola

tive of the fifth amendment of the Constitution of the

United States, in pertinent part reading: “Ro person

shall be * * * deprived of * * *, liberty, or prop

erty, without due process of law; * * *” Accord

ingly, they are entitled to the relief for which they

pray.

This 17th day of September, 1964.

W alter P. Ge w in ,

Circuit Judge.

S eybourn H. L ynne ,

District Judge.

H . H . Grooms,

District Judge.

APPENDIX B

Article I, Sec. 8, cl. 3 of the Constitution provides:

The Congress shall have power * * * To

regulate commerce * * * among the several

states.

Section 201 of Title I I of the Civil Rights Act of

1964, P.L. 88-352, 78 Stat. 241, 243, provides:

(a) All persons shall be entitled to the full

and equal enjoyment of the goods, services,

facilities, privileges, advantages, and accommo

dations of any place of public accommodation,

as defined in this section, without discrimina

tion or segregation on the ground of race, color,

religion, or national origin.

(b) Each of the following establishments

which serves the public is a place of public ac

commodation within the meaning of this title

if its operations affect commerce, or if discrim

ination or segregation by it is supported by

State action:

(1) any inn, hotel, motel, or other estab

lishment which provides lodging to transi

ent guests, other than an establishment lo

cated within a building which contains not

more than five rooms for rent or hire and

which is actually occupied by the proprie

tor of such establishment as his residence;

(2) any restaurant, cafeteria, lunchroom,

lunch counter, soda fountain, or other fa

cility principally engaged in selling food

for consumption on the premises, including,

but not limited to, any such facility located

on the premises of any retail establishment;

or any gasoline station -

(27)

28

(3) any motion picture house, theater,

concert hall, sports arena, stadium or other

place of exhibition or entertainment; and

(4) any establishment (A) (i) which is

physically located within the premises of

any establishment otherwise covered by

this subsection, or (ii) within the premises

of which is physically located any such

covered establishment, and (B) which

holds itself out as serving patrons of such

covered establishment.

r(c) The operations of an establishment affect

commerce within the meaning of this title if

(1) it is one of the establishments described

in paragraph (1) of subsection (b) ; (2) in the

case of an establishment described in para

graph (2) of subsection (b), it serves or offers

to serve interstate travelers or a substantial

portion of the food which it serves, or gasoline

or other products which it sells, has moved in

commerce; (3) in the case of an establishment

described in paragraph (3) of subsection (b),

it customarily presents films, performances,

athletic teams, exhibitions, or other sources of

entertainment which move in commerce; and

(4) in the case of an establishment described

in paragraph (4) of subsection (b), it is physi

cally located within the premises of, or there

is physically located within its premises, an

establishment the operations of which affect

commerce within the meaning of this subsec

tion. For purposes of this section, “ com

merce” means travel, trade, traffic, commerce,

transportation, or communication among the

several States, or between the District of

Columbia and any State, or between any for

eign country or any territory or possession and

any State or the District of Columbia, or be

tween points in the same State but through any

other State or the District of Columbia or a

foreign country.

U .S . GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFSCEi 1S&4