United States' First Set of Requests for Admission

Public Court Documents

September 27, 1988

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Chisom Hardbacks. United States' First Set of Requests for Admission, 1988. 1c7bb225-f211-ef11-9f8a-6045bddc4804. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c10ceb64-1b5c-4ff6-a071-3e29347ccce7/united-states-first-set-of-requests-for-admission. Accessed February 24, 2026.

Copied!

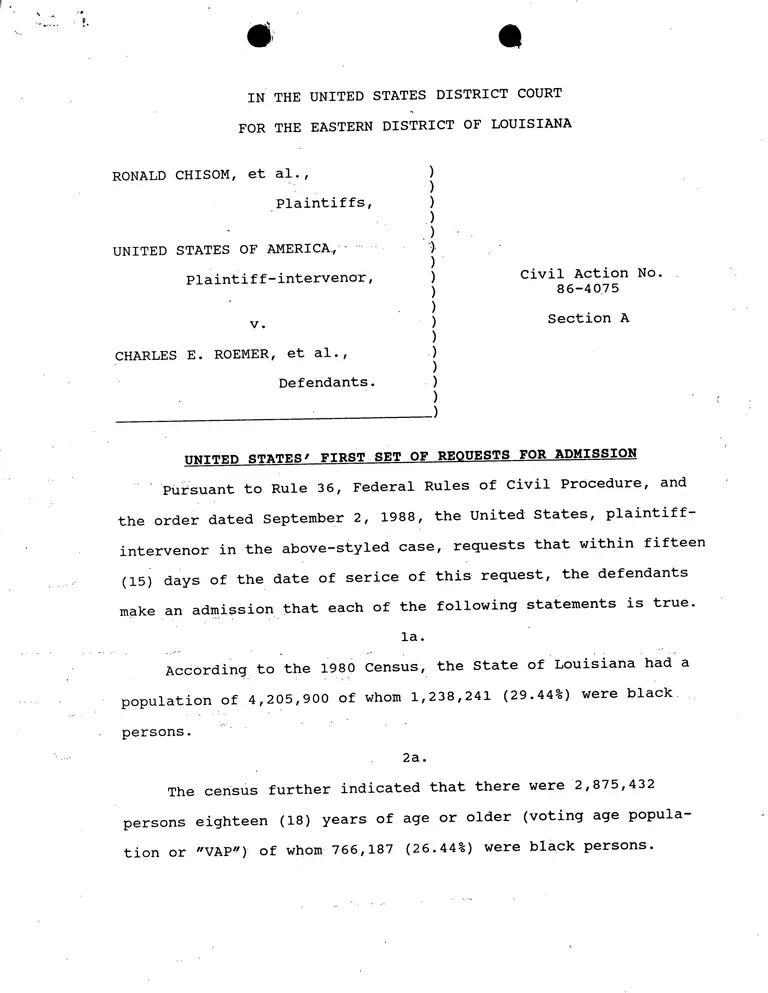

IN THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE EASTERN DISTRICT OF LOUISIANA

RONALD CHISOM, et al., )

)

Plaintiffs, )

)

.)

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, )

)

Plaintiff-intervenor, )

)

)

v. )

)

CHARLES E. ROEMER, et al., )

)

Defendants. )

)

)

Civil Action No.

86-4075

Section A

UNITED STATES/ FIRST SET OF REQUESTS FOR ADMISSION

Pursuant to Rule 36, Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, and

the order dated September 2, 1988, the United States, plaintiff-

intervenor in the above-styled case, requests that within fifteen

(15) days of the date of serice of this request, the defendants

make an admission that each of the following statements is true.

la.

According to the 1980 Census, the State of Louisiana had a

population of 4,205,900 of whom 1,238,241 (29.44%) were black

persons.

2a.

The census further indicated that there were 2,875,432

persons eighteen (18) years of age or older (voting age popula-

tion or "VAP") of whom 766,187 (26.44%) were black persons.

3a.

The Louisiana Supreme Court consists of seven members

elected in public elections to ten-year terms.

4a.

For purposes of electing members of the state supreme court

the state is divided into five single-judge election districts

and one multi-judge election district.

5a.

The supreme court election districts are comprised of the

following parishes:

First district: Orleans, St. Bernard, Plaque-

mines and Jefferson.

Second district: Caddo, Bossier, Webster,

Claiborne, Bienville, Natichitoches, Red

River, Desoto, Winn, Vernon and Sabine.

Third district: Rapides, Grant, Avoyelles,

Lafayette, Evangeline, Allen, Beuaregard,

Jefferson Davis, Calcasieu, Cameron and

Acadia.

Fourth district: Union, Lincoln, Jackson,

Caldwell, Ouachita, Morehouse, Richland,

Franklin, West Carroll, East Carroll, Madi-

son, Tensas, Concordia, LaSalle, and Cata-

houla.

Fifth district: East Baton Rouge, West Baton

Rouge, West Feliciana, East Feliciana, St.

2

Helena, Livingston, Tangipahoa, St. Tamman-

any, Washington, Iberville, Point Coupee,

St. Landry.

Sixth district: St. Martin, St. Mary, Iberia,

Terrebonne, Lafourche, Assumption, Ascension,

St. John the Baptist, St. James, St. Charles,

and Vermillion.

Attachment A is a map of Louisiana which accurately indicates

the supreme court election districts.

6a.

The five single-judge election districts consist of eleven

to fifteen parishes; the First Supreme Court District, the sole

multi-member district, consists of four parishes and elects two

judges.

and

7a.

The 1980 Census indicates that the population character-

istics for the six supreme court elections districts are as

follows:

Total pop.

1 1,102,253

2 582,223

3 692,974

4 410,850

5 861,217

6 556,383

Black pop. (%)

379,101 (34.39)

188,490 (32.37)

150,036 (21.65)

134,534 (32.74)

256,523 (29.79)

129,557 (23.28)

Total VAP

772,772

403,575

473,855

280,656

587,428

337,510

Black VAP (%)

235,797 (30.51)

118,882 (29.45)

92,232 (19.46)

81,361 (29.99)

160,711 (27.36)

78,660 (23.31)

8a.

The 1980 Census indicates that the population character-

istics for the parishes in the First Supreme Court District

[first district] are as follows:

Parish

Jefferson

Orleans

Plaquemines

St. Bernard

Total pop. Black pop. (%)

454,592

557,515

26,049

64,097

63,001 (13.85)

308,149 (55.27)

5,540 (21.27)

2,411 ( 3.76)

Total VAP

314,334

397,183

16,903

44,352

Black VAP(%)

37,145 (11.81)

193,886 (48.81)

3,258 (19.27)

1,508 ( 3.40)

9a.

As of July 1, 1988, registered voter data compiled by the

Louisiana Commissioner of Elections indicated the following

characteristics for

District

1

2

3

4

5

6

the supreme court

Total Regis. Voters

503,181

278,084

373,463

209,348

472,773

310,018

election districts:

Black Regis. Voters (%)

161,484 (32.09)

73,907 (26.58)

72,816 (19.50)

59,933 (28.63)

121,318 (25.66)

71,435 (23.04)

10a.

As of July 1, 1988, registered voter data compiled by the

Louisiana Commissioner of Elections indicated the following

characteristics for the first district:

Parish

Jefferson

Orleans

Plaquemines

St. Bernard

Total

Total Regis. Voters

203,000

244,374

14,327

41,480

503,181

Black Regis. Voters (%)

24,953 (12.29)

132,094 (54.05)

2,743 (19.15)

1,694 ( 4.08)

161,484 (32.09)

ha.

There is a majority-vote requirement in election contests

for the supreme court.

12a.

Elections for the two positions in the first district are Q,

4

•not conducted in the same years (staggered terms). This precludes

voters from single-shot voting.

13a.

Pursuant to state law, the Louisiana Supreme Court sits en

banc and its jurisdiction extends statewide.

14a.

None of the members of the supreme court are elected on a

statewide basis.

15a.

No parish lines are cut by the supreme court districts.

16a.

The State of Louisiana's Constitutional Convention of 1898

imposed a "grandfather" clause as well as educational and prop-

erty qualifications for voter registration which were designed to

limit black political participation.

17a.

Within ten years of the new qualification for voter regis-

tration authorized by the Convention of 1898, black voter regis-

tration had dropped from approximately 135,000 persons in 1896 to

less than 1,000 persons in 1907.

18a.

In 1921, the state amended its constitution and replaced

the "grandfather" clause with a requirement that an applicant

"give a reasonable interpretation" of any section of the federal

or state constitution. The United States Supreme Court in United

States v. State of Louisiana, 380 U.S. 145 (1965) held this

"interpretation" test to be one facet of the state's successful

plan to disenfranchise its black citizens.

19a.

In 1923, the state Democratic Party established, pursuant

to state law, an all-white primary which was in use until 1944.

20a.

Following the invalidation of the all-white primary in

1944, the state adopted such electoral devices as citizenship

tests, anti-single-shot laws and a majority vote requirement for

party officers.

21a.

In 1972 two black candidates ran unsuccessfully for the

supreme court from the first district.

22a.

No black person has been elected to the supreme court in

•the Twentieth Century.

23a.

No black person has run in a contested election for judicial

office in any parish in the first supreme court district other

than Orleans parish.

24a.

The following list identifies all black persons who have

been candidates in contested Orleans Parish judicial elections

since 1978, the office they sought and the date of the election:

Wilson Criminal Magistrate (September 16, 1978)

Ortique Civil Dist. Ct. H (March 3, 1979, primary)

Ortique Civil Dist. Ct. H (April 7, 1979, general)

Julien Civil Dist. Ct. I (February 6, 1982, primary)

Wilson Civil Dist. Ct. I

Julien Civil Dist. Ct. I (March 20, 1982, general)

Di Rosa Civil Dist. Ct. D (June 18, 1983)

Dorsey Civil Dist. Ct. F (September 29, 1984, primary)

Johnson Civil Dist. Ct. I

Douglas Civil Dist. Ct. B

Dannell Juvenile Ct. Div. A

Gray Juvenile Ct. Div. A

Young Juvenile Ct. Div. C

Douglas Civil Dist. Ct. B (November 6, 1984, general)

Young Juvenile Ct. Div. C

Magee Civil Dist. Ct. F (February 1, 1986, primary)

Wilkerson Civil Dist. Ct. F

Magee Civil Dist. Ct. F (March 1, 1986, general)

McConduit Municipal Court (September 26, 1986, primary)

Lagarde Juvenile Ct. Div. D

McConduit Municipal Court (November 4, 1986, general)

Douglas 4th Cir. court of (October 24, 1987)

appeals, Dist. 1

Hughes Civil Dist. Ct. G (March 8, 1988, primary)

Hughes Civil Dist. Ct. G (April 16, 1988, general)

25a.

There have been thirteen elections for district judgeship

in Orleans Parish which featured a contest between a white and a

black candidate since 1978. Black candidates have won three of

the contests. In this same time period (1978 to the present),

there have been thirteen elections for parochial or municipal

judgeship positions which also have featured a contest between a

7

white and a black candidate. Black candidates have won three of

these elections.

26a.

The court of appeals in Orleans Parish elects eight judges

on a parish-wide basis with a numbered-post provision to a separ-

ate district of one of the appellate circuits. The only con-

tested court of appeals election involving a black candidate was

in 1987 when a black candidate was defeated in Orleans Parish.

27a.

Ernest Morial became the first black person to serve on a

court of appeals in this century when he ran unopposed in 1972.

Israel Augustine also was unopposed in 1974, as was Joan Arm-

strong in 1984.

28a.

A regression analysis of the twenty-seven judicial elections

contests identified in Requests 24a to 26a indicates that black

voters cast a majority of their votes for the black candidate(s)

in twenty-four of the contests. The regression estimates reveal

that in only four of these twenty-four instances did the black

candidates receive less than 60% of the votes cast by black

voters and in fifteen, over half of the elections analyzed, the

black candidate received over 75% of the votes cast by black

voters. In no election, however, did a majority of white voters

vote for the black candidate(s). According to the regression es-

timates, less than 10% of the white voters voted for the black

candidate in thirteen of the contests. An examination of these

8

elections under an extreme case analysis indicates a similar re-

sult.

29a.

Judicial election contests constituted one-third (13 of 39)

of the elections analyzed by a panel of this court in Major v.

Treen, 574 F. Supp 325 (E.D. La. 1983).

30a.

The white population in the parishes surrounding Orleans

Parish, some of whom consist of persons seeking to avoid court-

ordered school desegregation, are less receptive to candidacies

by black persons than are residents of Orleans Parish.

31a.

The First Supreme Court District has twice the population

of any congressional district in Louisiana and, in terms of

population, is the largest of any of the state's election dis-

tricts.

32a.

After 1954, school boards in Louisiana failed to abolish de

lure segregation in the public schools voluntarily and it was

necessary for local federal courts to issue decrees in order to

obtain compliance with federal law.

33a.

The state maintained a dual university system until 1981.

34a.

Public accommodations and facilities were not open to

members of both races until the late 1960s.

9

35a.

The following 1980 Census statistics indicate that black

residents of the four parishes in., the first district lag signifi-

.

cantly behind white residents in several socio-economic categor-

ies.

Jefferson Orleans ' Plaquemines St.Bernard

persons over 25 high .

school grad. (%) 70;9 49.2 7Q.8 46.9 56.0 27.1 58.5 32;0

. .

- per capita income $8,302 4,279 9,781 3,985 6,620 3,185 6,660 3,155

families below

poverty level (7) 5.3 24.7 7.4 33.4 7.7 32.4 6.6 31.6

persons 200% be-

- low poverty level (7)- 20,2. 55.0 8.0 29.1' 29.9 68.0 26.1 74.8

• •

%ofocivilian -

,force Unemployed' - 3..6' 8.3. 4.0 10.1 • 3.5 14.4 4.7 15.0

36a.

• A consistent application of the state policy of electing

members f the supreme court from single-judge election districts

that do not cross parish lines would result in Orleans Parish

constituting single-judge election district.

37a.

A supreme court election district comprised exclusively of

Orleans Parish would have a black majority of the total popu-

lation (55.27%) and of the registered voters (54.05%).

JOHN VOLZ WM. BRADFORD REYNOLDS

United States Attorney Assistant Attorney General

GERALD W. JONES

STEVEN H. ROSENBAUM

ROBERT S. BERMAN

Attorneys, Voting Section

Civil Rights Division

Department of Justice

P.O. Box 66128

Washington, D. C. 20035-6128

(202) 724-3100

V

I

N

R

W

H

O

V

I

I

V

•

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that on this2ji day of September 1988, I

served a copy of the foregoing United States' First Set of Re-

quests for Admission by mailing a copy, by overnight express

mail, to the following persons:

William P. Quigley

901 Convention Center Blvd.

Fulton Place

Suite 901

New Orleans, LA 70130

Roy Rodney, Jr.

643 Magazine Street

New Orleans, LA 70130

Julius L. Chambers

Charles Stephen Ralston

C. Lani Guinier

99 Hudson Street, 16th Floor

New York, New York 10013

Pamela S. Karlen

University of Virginia Law School

Charlottesville, VA 22901

Ron Wilson

Richards Building, Suite 310

837 Gravier Street

New Orleans, LA 70112

William J. Guste, Jr.

Attorney General

Louisiana Department of Justice

234 Loyola Avenue, 7th Floor

New Orleans, LA 70112

M. Truman Woodward, Jr.

909 Poydras Street, Suite 2300

New Orleans, LA 70130

Blake G. Arata

201 St. Charles Avenue

New Orleans, LA 70130

George Strickler, Jr.

639 Loyola Street

Suite 1075

New Orleans LA 70113

A. R. Christovich

1900 American Bank Bldg.

New Orleans, LA 70130

Noise W. Dennery

601 Poydras Street

New Orleans, LA 70130

Robert G. Pugh

330 Marshall Street, Suite 1200

Shreveport, LA 71101

ROBERT S.BERMAN

Attorney, Voting Section

Civil Rights Division

Department of Justice

P.O. Box 66128

Washington D. C. 20035-6128

202-724-3100