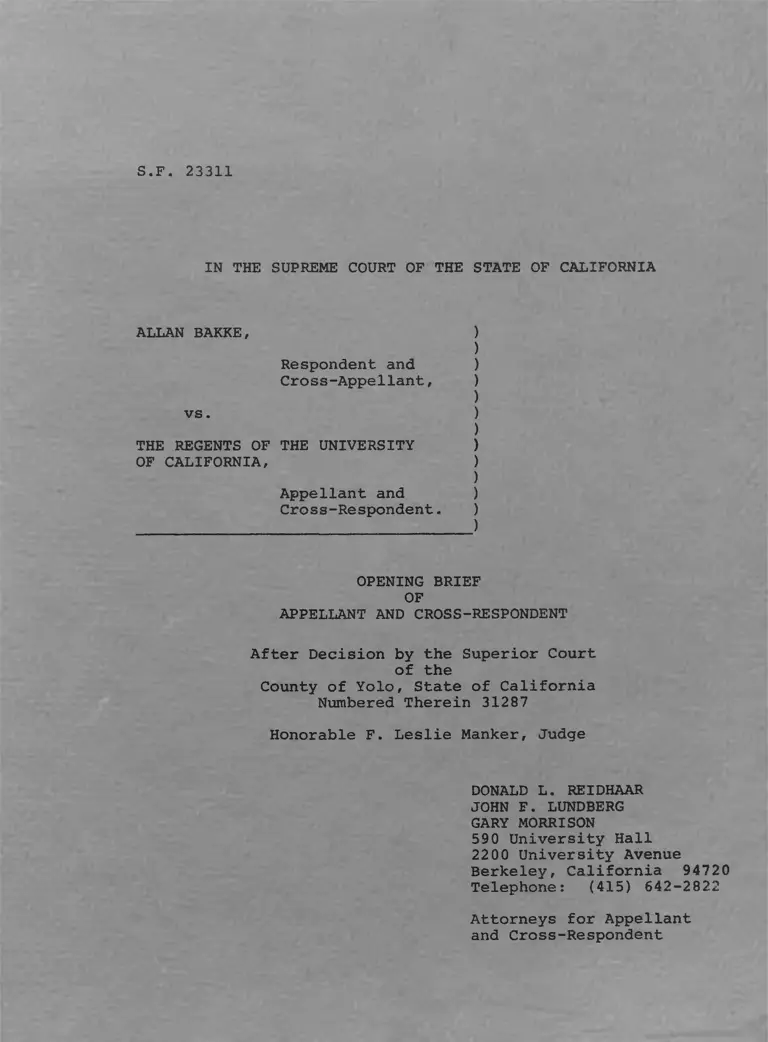

Bakke v. Regents Opening Brief of Appellant and Cross-Respondent

Public Court Documents

July 29, 1975

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Bakke v. Regents Opening Brief of Appellant and Cross-Respondent, 1975. baa5b153-be9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c12a31ec-f95e-42b4-91c9-22e54d0f687a/bakke-v-regents-opening-brief-of-appellant-and-cross-respondent. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

S.F. 23311

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA

ALLAN BAKKE, )

)Respondent and )

Cross-Appellant, )

)

vs. )

)

THE REGENTS OF THE UNIVERSITY )

OF CALIFORNIA, )

)

Appellant and )

Cross-Respondent. )

)

OPENING BRIEF

OF

APPELLANT AND CROSS-RESPONDENT

After Decision by the Superior Court

of the

County of Yolo, State of California

Numbered Therein 31287

Honorable F. Leslie Manker, Judge

DONALD L. REIDHAAR

JOHN F. LUNDBERG

GARY MORRISON

590 University Hall

2200 University Avenue

Berkeley, California 94720

Telephone: (415) 642-2822

Attorneys for Appellant

and Cross-Respondent

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

1 3

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

SUBJECT INDEX

Page

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

1. Introduction 1

2. Procedural History 1, 2 , 3

3. The Admissions Process at the

Davis Medical School . . . . 3, 4, 5, 6

a. The Regular Admissions Program 3, 4

b . The Special Admissions P r o g r a m ........ 4, 5, 6

1. Does the Equal Protection Clause of the United

States Constitution, the Privileges and Immuni

ties Clause of the California Constitution, or

Title VI of the Federal Civil Rights Act of 1964

deny officials of a state university discretion

to fill a limited number of places in a medical

school class with qualified members of ethnic

minority groups from disadvantaged backgrounds

for purposes of promoting diversity in the

school and in the medical profession and expand

ing medical education opportunities for such dis

advantaged members of minority groups? ........

2. Did the trial court correctly refuse to order

Bakke's admission to the Davis Medical School? . . 6

I. IN CHOOSING WHICH OF MANY QUALIFIED APPLICANTS

WILL BE OFFERED PLACES IN EACH YEAR'S ENTERING

CLASS AT THE DAVIS MEDICAL SCHOOL, THE UNIVERSITY

HAS DISCRETION TO FILL A REASONABLE NUMBER OF

THOSE PLACES BY GIVING SPECIAL CONSIDERATION TO

QUALIFIED DISADVANTAGED MEMBERS OF ETHNIC MINORITY

GROUPS ...................................... .. *

STATEMENT OF ISSUES 6

ARGUMENT 7

i.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

SUBJECT INDEX

Page

A. Professional Schools, Particularly Those

Within the University of California, Must

be Given Broad Discretion to Make Admis

sions Decisions ...................... 7-15

B. Neither the Equal Protection Clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment Nor the Privileges and

Immunities Clause of the California Consti

tution Denies University officials Discretion

to Give Special Consideration to a Reason

able Number of Qualified Minority Applicants,

When Such Consideration is Given for the

Purposes of Promoting Diversity in the

School and the Profession and Expanding

Medical Education Opportunities for Dis

advantaged Members of Minority Groups . . . 16-32

1. The Special Admissions Program Is Not

Per Se Unconstitutional, But Is

Consistent With the Purposes of the

Equal Protection Clause........ .. 16-20

2. Racial Classifications Designed to

Assist Minorities Are Not Subject to

the Same Strict Scrutiny as Classifi

cations Directed Against Minorities . . 21-25

3. The Efforts of the University to

Assure That Disadvantaged Members of

Minority Groups Have a Reasonable

Representation in the Davis Medical

School and in the Medical Profession

Serve Rational and Compelling Univer

sity Interests ........................26-32

II. THE ADMISSIONS STANDARDS USED BY THE DAVIS

MEDICAL SCHOOL ARE PERMITTED BY TITLE VI OF

THE CIVIL RIGHTS ACT OF 1964 . . . . . . . . 34, 35

III. THE TRIAL COURT CORRECTLY FOUND THAT BAKKE

WOULD NOT HAVE BEEN ADMITTED EVEN IF THERE

HAD BEEN NO SPECIAL ADMISSIONS PROGRAM . . . . 36-38

IV. CONCLUSION . . . . . . ........ . . . . . . . 39-41

li.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES CITED

CASES

Page

Alevy v. Downstate Medical Center (Sup. Ct. 1974)

78~ Misc. 2d 1091, 359 N.Y.S.2d'426, 429, aff'd

(2d Dep., 1975), 47 A.D.2d 715, 366 N.Y.S.2d

390 ................................. ..

Brown v. Board of Education (1954) 347 U.S. 483,

“ 494, 98 L.Ed. 873, 880-81 ...................

Carter v. Gallagher (8th Cir. 1971) 452 F.2d 315,

---3 31; cert, denied (1972) 406 U.S. 950,

32 L .Ed. 2d 338 ........ .................. *

Clarke v. Redeker (8th Cir. 1969) 406 F .2d 883,

cert, denied (1969) 396 U.S. 862 ..........

Conne11v v. University of Vermont and State_Agr.

Coll. (D. Vt. 1965) 244 F.Supp. 156 . . . . .

DeFunis v. Odeqaard (1973) 82 Wn.2d 11, 507 P.2d

116 9 j vacated as moot (1974) 416 U.S. 312,

40 L .Ed,2d 164, 185, (1974) 84 Wn.2d 617, 529,

438 ............................... ..

P. 2d

11, 29, 30

General Order and Memorandum (W.D. Mo. 1968)

4 T T T r7d7 “1 3 3, 141 ̂ • ~ ............................

Goldberg v. Regents of the University of California

(1967) 248 C .A.2d 867, 874 . ....................• *I

Graham v. Richardson (1971) 403 U.S. 365, 372,

29 L.Ed.2d 534, 541-542 .............................

Hamilton v. University of California (1934)

293 U.S. 245, 255; 79 L.Ed. 343, 349 ...............

Hirabayashi v « United States (1943) 320 U.S. 81,

100, 87 L.Ed. 1774, 1786 ................... .. . . .

iii.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES CITED

(c ontinua11onl

CASES

Page

Ishimatsu v. Regents of the University of California

(1968) 266 C .A .2d 854 ” 864 ................... • 11

Korematsu v. United States (1944) 323 U.S. 214,

---216, 223; '59 L . Ed.' 1947 199, 202 .............

Lau v. Nichols (1974) 414 U.S. 563, 39 L .Ed.2d 1

Loving v. Virginia (1967) 388 U.S. 1, 18 L.Ed.2d

T 5 1 0 , 1020 ...................* ..............

McLaughlin v. Florida (1964) 379 U.S. 184,

13 L.Ed.2d 222 . .............................

Norwalk Core v. Norwalk Redevelopment Agency

(2d Cir. 1968) 395 F.2d 920, 931-2 ..........

Oregon v. Mitchell (1970) 400 U.S. 112, 284,

27 L.Ed.2d"2727 373 .........................

People, ex. rel. Lynch v.

School District (1971)

San Diego Unified

T9_cTa .3d 252, 261

Porcelli v. Titus (3d Cir. 1970) 431 F.2d 1254,

1257 . . r. .".............................

San Antonio Indep. School District v..R_odrig_uez_

(1973) 411 U.S. 1, 98-110, 36 L.Ed.2d 16

(Justice Marshall dissenting)...............

San Francisco Unified School District v . Johnson

(1971) 3 C . 3d 937, 950, 9 5 1 ............ *

Slaughter-House Cases (1872) 83 U.S. 395, 407,

21 L.Ed. 59, 72 ...........................

Strauder v. West Virginia (1879) 100 U.S. 303,

306-3077 25‘L.Ed. 664, 665 .................

16, 24

23, 24

. 25

16, 20

17, 19

. 17

iv.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13,

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES CITED

(continuation)

CASES Page

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education

(1971) 402 U.S. 1, 16, 28 L.Ed.2d 554, 566. .22, 23, 24

United States V. Carolene Products Company (1938)

304 U.S. 144, 152, n. 4; 82 L.Ed. 1234, 1242,

n. 4............................. 19

Wall v. Board of Regents, U.C. (1940) 38 C.A.2d

698 , 699 ........................................... 11

Williamson v. Lee Optical Company (1955) 348 U.S.

483, 99 L.Ed. 563 ............................. 20

Wong v. Regents of the University of California

(1971) 15 C . A . 3d 823. . . . .~........ .. . . . 12, 13

Wright v. Texas Southern University (5th Cir. 1968)

392 F . 2d 728. ...................................... 12

Yick-Wo v. Hopkins (1885) 118 U.S. 356, 373-374,

30 L.Ed.220, 223.................................... 19

v.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

STATUTES AND REGULATIONS

Page

42 U.S.C

45 C.F.R

45 C.F.R

45 C.F.R

45 C.F.R

Section

Section

Section

Section

Section

2000(d). . . .

80.3(b) (vii) (6)

8 0.4(1) and (2)

80.5(e). . . .

80.5 (j). . . .

2, 3, 6, 34

. . . . 35

. . . . 35

. . . . 35

. . . . 34

CONSTITUTIONAL PROVISIONS

Page

United States Constitution,

13th Amendment. . . . . 17, 18

United States Constitution,

14th Amendment. . . . 2, 3, 6, 17, 24, 30, 33

United States Constitution,

15th Amendment. . . . 17

California Constitution,

Article I, Section 21 .

California Constitution,

Article IX, Section 9 .

vi.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

PUBLICATIONS

Page

Bickel, The Original Understanding and the

Segregation Decision 69 Harvard L.Rev. 1, 60. . . 1/

Colwill, J., Jr., "Medical School Admissions as a

Reflection of Societal Needs", The Pharos,

publication of Alpha Omega Alpha (July 1973)

91, 92........ .....................................

Curtis, Blacks, Medical Schools and Society (1971)

University of Michigan Press, 147 .................

"Developments in the Law- Equal Protection" (1969)

82 Harv. L . Rev. 1965. . • • • * • * ...............

Dube and Johnson, "Study of U.S. Medical School

Applicants, 1972-73", 49 Jour. Med. Educ.,

849-869 (1974). . . . ...................

Ely, J . , The Constitutionality of _Reyerse_^aci^l.

Discrimination, 41 U. of Chicago L.Rev. 723

(1974) .................

"Graduate and Professional School Opportunities

for Minority Students", 5th Ed. (1973-74),

published by Educational Testing Service . . . . . iu

Griswold. E., Some Observations on the D,ejhinis__Case, ___

75 C o lu m .~LTRevu Wl2~, 5 T 4 -5T 5 (T9T5T^ * * 7 ' 10

Gunther, The Supreme Court, 1971 Term-g^rward:

In Search of Evolving Doctrine on a Changing

Court: A Model for a Newer Equal Ptotecjtion,

J T ~ E a r v . L.Rev. 1 (1972). ........... - ............ 25

Karst and Horowitz, Affirmat.iye_Aot^^r^ Egua^

Protection, (1974) 60 Va. L.Rev. 955, 956-965,

part of a Symposium entitled, ’"DeFunis : The

Road Not Taken" . ...........................

Kendrick, "Minority Students on Campus' xn The ̂

Minority Student on the Campus :_

ahTTos sib ill tie s ..........

8

29

Kurland, Egalitarianism and the Warren_Court,

68 Mich. L.Rev. 629, 674 (1970) . . . • - . 17

v n .

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

PUBLICATIONS (continuation)

Page

"Medical School Admission Requirements, U.S.A.

and Canada" (24th Ed., 1974-75) published by

the Association of American Medical Colleges . . . 10

Nickel, J., Preferential Policies in Hiring and

Admissions! Sr~3jrfT§prudenFTaI 'AppToacTT)

75 Colum. ~L. Rev. 52Tj 5TF~*(1975) T ........... 2 7

O'Neill, R., Preferential Admissions, Equalizing

the Access~~oF~Mhorit.y~^r^upsl~Eo Higher- ~~

Education (1971) 80 Yale Law Journal 6~99, 735 . . 29

"'Reverse Prejudice': Medical School Issue", Medical

World News (March 10, 1975) 47-48 . . 7 T T . " . . 10

Thresher, "College Admissions and the Public

Interest" (1966) pp. 56-57, 59-61 . . . . . . . . . 9

1970 Census of Population: Detailed Characteristics -

California (PC(1) - D6), Table lT9 . . . . .~. . . 33

1970 Census of Population: Occupational Characteristics -

U .S ., Subject Report PC (2), Table 2 ...............26

Brief of the President and Fellows of Harvard

College, Amicus Curiae, U.S. Sup. Ct.,

DeFunis v. Odegaard, 5 2 . . . . . ............. 39,40

viii.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

S.F. 23311

IN THE SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA

ALLAN BAKKE, )

)

Respondent and )

Cross-Appellant, )

)

vs. )

)

THE REGENTS OF THE UNIVERSITY )

OF CALIFORNIA, )

}

Appellant and )

Cross-Respondent. )

)

OPENING BRIEF

OF

APPELLANT AND CROSS-RESPONDENT

After Decision by the Superior Court

of the

County of Yolo, State of California

Numbered Therein 31287

Honorable F. Leslie Manker, Judge

TO THE HONORABLE DONALD R. WRIGHT, CHIEF JUSTICE,

AND TO THE HONORABLE ASSOCIATE JUSTICES OF

THE SUPREME COURT OF THE STATE OF CALIFORNIA:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

1. Introduction

This case concerns the legality of a special

admissions program operated by Appellant and Cross-Respondent

The Regents of the University of California (hereafter

"University") at the School of Medicine of the University of

California, Davis (hereafter "Davis Medical School"). That

program gives special consideration to the minority group

status of qualified applicants from economically and educa

tionally disadvantaged backgrounds in filling a limited

number of spaces in each year's class for the purposes of

promoting diversity in the School and the profession, and

expanding medical education opportunities for disadvantaged

members of minority groups. (CT 388:31-389:6)

2. Procedural History

Respondent and Cross-Appellant. Allan Bakke (here

after "Bakke") unsuccessfully applied for admission to the

Davis Medical School for the academic years beginning

September 1973 and September 1974. (CT 387:15-17) Bakke brought

suit in the Yolo County Superior Court against the University

for a mandatory injunction ordering his admission, alleging

that his applications would have been accepted if members of

ethnic minority groups had not been admitted under the

special admissions program which he claimed discriminated

against him on the basis of his Caucasian race, in violation

1.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

of the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment

of the United States Constitution, the Privileges and Immunities

Clause of the California Constitution (Article 1, Section 21)

and the Civil Rights Act of 1964 (42 U.S.C. § 2000(d)). (CT 1-4)

The University alleged that Bakke was not entitled

to an injunction ordering his admission because he would not

have been admitted even if there had been no special admissions

program and that the special admissions program was lawful.

(CT 24-26) In order to bring the issue of the legality of

the special admissions program squarely before the court

regardless of whether the operation of the program resulted

in Bakke's failure to be admitted, the University cross-

complained for declaratory relief as to the legality of the

special admissions program. (CT 29-31)

No testimony was taken at the trial and the case

was submitted on the following evidence:

The pleadings (CT 1-8; 24-33; 57-60);

The deposition and attached exhibits of

George H. Lowrey, M.D., the Associate

Dean and Director of Admissions at the

Davis Medical School (CT 141-281) ;

The declaration of George H. Lowrey, M.D.

(CT 61-73); and

Plaintiff's Answers to Defendant's Inter

rogatories (CT 48-55) .

///

2.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

The trial court found, on the UNIVERSITY'S cross

complaint for declaratory relief, that the special admissions

program violated the Fourteenth Amendment to the United

States Constitution, the Privileges and Immunities Clause of

the California Constitution, and Title VI of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964 (CT 390:29-391:4; CT 394:14-20)

The trial court also found that Bakke would not

have been accepted for admission, in either 1973 or 1974,

even if there had been no special admissions program, and

therefore declined to order his admission as requested in

his complaint for injunctive relief. (CT 389:20-390:4)

3. The Admissions Process at the Davis Medical__School_

a. The Regular Admissions Program

The admissions process at the Davis Medical School

is initiated by filing an application form which contains

Medical College Admissions Test (MCAT) scores, academic

background, personal information, and personal comments.

(CT 62:7-26; CT 112-116) After receiving the application

the applicant’s file is supplemented by letters of recommenda

tion and transcripts. (CT 62:8-10) Applicants' files are

screened by an Admissions Committee of faculty and students

chosen by the Dean of the Medical School. (CT 62:12-16)

Selected members of the Admissions Committee screen the files

to determine which of the applicants will be invited for a

personal interview. If an applicant is not interviewed he

is sent a letter of rejection. (CT 62:27-63:8) After the

3.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

interview the interviewer writes a summary of the interview

stating his evaluation of the interviewee’s potential contri

bution to the medical profession. The interviewer then

reviews the applicant's file, along with the results of the

interview, and rates the applicant on a scale of zero to

one hundred. The file, including the interview summary,

but not the rating of the interviewer, is then submitted to

a meeting of the Admissions Committee for a review and rating

by other members. The other members of the Admissions

Committee then rate each applicant on a scale of zero to one

hundred and the ratings are added for a combined numerical

rating. An applicant's combined numerical rating is used as

a bench mark for selection. (CT 63:13-32) For the class

entering in 1973, there were five raters and therefore a

maximum possible rating of 500; for 1974 there were six

raters and a maximum possible rating of 600 (CT 63:21-29)

b . The Special Admissions Program

The application forms permit minority applicants

from disadvantaged backgrounds to request consideration under

the special admissions program. Applicants making such a

request are considered by a subcommittee of the Admissions

Committee (hereafter "Special Admissions Committee").

Each application is screened first by the faculty chairman

of the Special Admissions Committee to determine whether the

applicant is disadvantaged. In making this determination,

the chairman looks at such factors as whether the student

4 .

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

has requested and been granted a waiver of his application fee,

which requires a means test; whether the student was an

Educational Opportunity Program (EOP) student in college;

whether the applicant worked during his undergraduate years

or interrupted his education to support himself or family

members; his parents' occupational and educational level;

and other information relative to disadvantage which is

volunteered by the applicant. Minority applicants from

nondisadvantaged backgrounds are referred to the regular

admissions process. (CT 64:28-66:10)

After the chairman of the Special Admissions

Committee has classified those students qualifying for

consideration as disadvantaged members of minority crroups,

their applications are reviewed in the same manner as all

other applications. The applications are screened to

determine which of such applicants will be invited for an

interview. Interviews are conducted and the interviewees

evaluated and given a combined numerical rating. (CT 66:11-25)

Acceptances are generally mailed to applicants at

four times during the year. Sixteen of the one hundred

places in each year's opening class are reserved for applicants

under the special admissions program. About one-half of

those offered admission through the special admissions

program choose to attend the Davis Medical School. Therefore,

as each batch of regular acceptance letters is mailed the

Special Amissions Committee selects approximately eight of

5.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

the most promising disadvantaged minority applicants and

makes a written and oral report to the regular Admissions

Committee concerning each. The regular Admissions Committee

then votes on whether the recommendations shall be con

firmed. Those confirmed are sent letters of acceptance.

(CT 66:26-67:9)

Every applicant accepted to the Davis Medical

School, whether admitted through the regular admissions

program or the special admissions program, is fully quali

fied for admission and will, in the opinion of the Admissions

Committee, contribute to the School and the profession.

(CT 67; 9-13)

sta t e m e n t of issues

1. Does the Equal Protection Clause of the United

States Constitution, the Privileges and Immunities Clause of

the California Constitution, or Title VI of the Federal

Civil Rights Act of 1964 deny officials of a state university

discretion to fill a limited number of places m a medical

school class with qualified members of ethnic minority

groups from disadvantaged backgrounds for purposes of

promoting diversity in the school and in the medical pro

fession and expanding medical education opportunities for

such disadvantaged members of minority groups?

2. Did the trial court correctly refuse to order

Bakke's admission to the Davis Medical School?

6.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

ARGUMENT

I. IN CHOOSING WHICH OF MANY QUALIFIED APPLICANTS WILL

BE OFFERED PLACES IN EACH YEAR'S ENTERING CLASS AT

THE DAVIS MEDICAL SCHOOL, THE UNIVERSITY HAS

DISCRETION TO FILL A REASONABLE NUMBER OF THOSE

PLACES BY GIVING SPECIAL CONSIDERATION TO QUALIFIED

DISADVANTAGED MEMBERS OF ETHNIC MINORITY GROUPS

A. Professional Schools, Particularly Those Within

the University of California, Must be Given

Broad Discretion to Make Admissions Decisions

Admissions officials at the Davis Medical School

have a responsibility to choose which 100 of the thousands

of applicants will best serve the School and the

profession. The discharge of that responsibility requires

the informed judgment of thoughtful professionals involved

in the health sciences in determining the needs of the School

and the profession and in developing admissions criteria

which fill those needs. Their task necessarily involves no

more and no less than a systematic development of special

or "preferential" standards through which the vast number of

applicants qualified to pursue medical studies are narrowed

to those few who can be accepted.

///

///............ ... ........... ......... — ----------------------

1/ For the class entering in 1973 the Davis Medical

School received 2,464 applications, that is

approximately 25 for each place; in 1974 there

were 3,737 applications, approximately 37 for

each place. (CT 62:3-7)

2/ See E. Griswold, Some Observations on the DeFunis Case,

75 Colum. L .Rev. 512, 51T-515 (1975T~

7.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

The abilities demonstrated by previous academic

records and standardized test scores form the basis for one

such preferential standard and an important one. But, an

outstanding academic record does not alone disclose whether

an applicant has those qualities of character or motivation

necessary for a good physician. For example, the school

may and does consider that the greater present need of the

medical profession is not for more academic doctors who may

favor medical research, but for family physicians who have

/

the personal qualities necessary to serve all income levels

in a practice in which success may not correlate with the

_3/

highest grades and test scores.

There are many other such preferential standards:

Schools often give preference to applicants who will bring

distinction and diversity to the school because of special

talents, skills, backgrounds and motivations; undergraduate

education at one institution may be preferred over under

graduate education at another; certain courses of study may

be preferred over others; one applicant's hobbies or work in

the community may make him more desirable than another

3/ See Karst and Horowitz, Affirmative Action and Equal

Protection (1974) 60 Va. L.Rev. 955, 956 — 965, part of

a' Symposium entitled "DeFunis : The Road Not Taken",

for a discussion of the common misconception that the

qrades and test scores necessarily correlate with

qualifications; J. Colwill, "Medical School Admissions

as a Reflection of Societal Needs", The^ Pharos, publica

tion of Alpha Omega Alpha (July 1973l~927^93.

8 .

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

applicant with higher grades who has no strong non-academic

interests; those who have shown leadership as undergraduates

may be given preference because they can be expected to bring

leadership and inspiration to other students while in school

and credit to the school in later life. See, e.g., Thresher,

College Admissions and the Public Interest (1966) pp. 56-57,

59-61.

Another common preference is based upon the appli

cant's residence. At many public institutions, by statute

or regulation, preference is required to be given to residents

of a state. See, e.g., Clarke v. Redeker (8th Cir. 1969)

406 F .2d 883, cert, denied (1969) 396 U.S. 862. Indeed, the

Davis Medical School gives preference to California residents

who are likely to return to areas in California in need of

physicians, especially such areas in northern California.

(CT 64:32-65:2)

The development of such preferential standards is

especially necessary in-medical schools because of the

tremendous number of applications for the few places in each

class: The Davis Medical School receives nearly 40 applications

for each place. (CT 62:3-7) Just as the School has determined

that its best interests and those of the profession are not

served by a class made up solely of those applicants with

the highest grades and test scores, it has similarly concluded

that those interests are not best served by a class containing

few, if any, disadvantaged members of minority groups. (CT 67:25—

9.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

12

14

12

if

i;

IS

68:27) So, the School has instituted preferential standards

to assure a reasonable minority representation. Similar

programs have been instituted at many other medical schools

throughout the country. The same is true with respect

4/

to almost all law schools.

The courts have often recognized that the setting

of standards concerning the makeup of a student body is a

///

ZZZ_

3/ See "Medical School Admission Requirements, U.S.A. and

Canada" (24th Ed., 1974-75) published by the Association

of American Medical Colleges; "Graduate and Professional

School Opportunities for Minority Students , 5th Ed.

(1973-74), published by Educational Testing Service.

To take a few of many examples of such programs from

the compilation of catalogues in "Medical School

Admissions Requirements": Stanford University

School of Medicine has a "special program for

minority students from disadvantaged, educational

and social backgrounds. Under this program 12 students

of American citizenship are admitted to the M.D. program

annually." (p. 101) At the Harvard Medical School

"Special consideration is given to minority group

students who demonstrate the potential for successful

completion of the medical school curriculum (p. 163)

And at the University of Minnesota-Duluth School of

Medicine "A program has been established for regional

native Americans." (p. 177) The University of

Minnesota-Minneapolis Medical School_ has recently

established a special program in medical education

for minority students." (p. 179) These programs

have had some success. Approximately 10% of the

students beginning medical school in 1974 were Bla ,

Chicano, native American, or mainland United States

Puerto Ricans compared to 4.9% in 1969 See "’Reverse

Prejudice': Med School Issue", Meda^a^J^WJte^S-

(March 10, 1975) 47-48.

4/ E. Griswold, Some Observations on the DeFuni£__Case

” 75 Colum. L .Rev. 512, 5l6 (1973), a part oi a

"DeFunis Symposium" in the April 1975 Columbia Law

Review.

10.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

function primarily within the discretion of University

5/officials. In California, this discretion is rooted in

the State Constitution, which gives The Regents "full powers

of organization and government" over the University of

California. California Constitution Article IX, Section 9;

Hamilton v. University of California (1934) 2 93 U.S. 245,

255; 79 L.Ed. 343, 349. The University has been analogized

to "a branch of the state government equal and coordinate with

the legislature, the judiciary and the executive." 30 Ops. Cal.

Atty. Gen. 162, 166, quoted with favor in Ishimatsu v. Regents

of the University of California (1968) 266 C.A.2d 854, 864.

This constitutional power of The Regents includes,

of course, the right to determine admission standards. In

Wall v. Board of Regents, U.C. (1940) 38 C.A.2d 698, 699,

the Court referred to Article IX, Section 9, of the Constitution

and concluded that "this court has no right to interfere

with [the University's] government. The conclusions reached

by The Regents are final in the absence of fraud or opression."

See, also. Goldberg v. Regents of the University of California

(1967) 248 C .A .2d 867, 874.

5/ The decisions of the trial court in this case and the

~ trial court in DeF'unis v. Odegaard, which was overturned

by the Washington Supreme "Court (T973) 82 Wn.2d 11, 507 P .2d

1169, vacated as moot (1974) 416 U.S. 312, 40 L.Ed.2d 164,

are the only decisions of any court of which Appellant is

aware which uphold a challenge to the discretion of univer

sity officials to make admissions decisions and to adopt and

implement minority preference admissions programs.

11.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

Even in the absence of constitutional powers,

decisions by college or university authorities regarding the

makeup of the student body are final and nonjusticiable in

the absence of proof they were made arbitrarily, capriciously,

or were motivated by bad faith. See Wright v. Texas Southern

University (5th Cir. 1968) 392 F.2d 728. In Wong v. Regents

of the University of California (1971) 15 C.A.3d 823, the

Court discussed the legal standards applicable to judicial

review of the judgment of a medical school on whether a

student, once admitted, should be permitted to continue in

school. The legal standards governing discretion to admit

could not be more stringent than those governing dismissal,

since the adverse effect on the student manifestly is greater

if he is dismissed than if he is merely denied admission.

Wong upheld the dismissal of a student after attending

medical school for four years. That decision referred

to the rule of judicial non-intervention in scholastic

affairs and quoted favorably from Connelly v. University

of Vermont and State Agr, Coll. (D. Vt. 1965) 244 F.Supp. 156,

as follows:

"The effect of these decisions is to give

the school authorities absolute discretion

in determining whether a student has been

delinquent in his studies, and to place

the burden on the student in showing that

his dismissal was motivated by arbitrariness,

12.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

capricousness or bad faith. The reason for

this rule is that in matters of scholarship,

the school authorities are uniquely qualified

by training and experience to judge the

qualifications of a student, and efficiency

of instruction depends in no small degree

upon the school faculty's freedom from

interference from other non-educational

tribunals.

"The rule of judicial non-intervention in

scholastic affairs is particularly

applicable in the case of a medical

school. A medical school must be the

judge of the qualifications of its

students to be granted a degree? courts

are not supposed to be learned in medicine

and are not qualified to pass opinion as

to the attainments of a student in medicine. . .

(Wong V. Regents, supra, 15 C.A.3d at 830.)

One of the reasons for this broad grant of power

is given eloquent expression in a recent Federal Court

opinion:

"If it is true as it may well be, that man is

in a race between education and catastrophe,

13.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

it is imperative that^educational institutions

not be limited in the performance of their

lawful missions by unwarranted judicial

interference."

(General Order and Memorandum (W.D. Mo. 1968)

45 F.R.D. 133, 141.)’

The minority preference at issue here is simply an

attempt by responsible professionals at the Davis Medical

School to do their job: design an educational policy to

produce physicians which best meet the needs of the School, the

medical profession, and ultimately the patients they will serve.

These needs are not best met by a medical profession which

continues to count in its ranks only a tiny percentage of

minority physicians. If the affirmative efforts by the

Davis Medical School to remedy this situation are halted by

the courts, the minority representation among physicians

will become even smaller as the competition for medical spaces

6/

becomes ever more severe. But if these efforts are

permitted to continue, the time will almost certainly come

when special minority admissions programs will no longer be

6/ In spite of the fact that many medical schools have

increased their enrollments in recent years, it is

increasingly difficult to gain admission to medical

school. In 1970 54% of applicants to medical schools

were unable to gain admittance. By 1972 the rejection

rate had risen to 72%. See Dube and Johnson, 'Study

of U.S. Medical School Applicants, 1972-73", 49 Jour.

Med. Educ. 849, 869 (1974)

14.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

necessary, as more and more disadvantaged members of minority

groups recognize that they can successfully aspire to medical

6a/

careers.

The special admissions program is like the myriad

of other preferential programs comprising the very heart of

the admissions process: Whenever one qualified applicant is

selected over another a "discrimination" takes place. But

these "discriminations" result from a responsible attempt to

meet legitimate educational needs. They do not violate

fundamental law.

///

///

///

///

///

///

///

///

///

/// ______________ __ ______________________________________

6a/ See J. Ely, The Constituionalitv of Reverse. ..B&sIa I

Discrimination, 41 U. of Chicago L.Rev. 723, 726,

n. 2 2 nin/ryT~ "The real hope lies, I think, in the

fact that parents seem to make a difference. . . .

If we underwrite a generation of Black professionals,

even a generation that does not do quite as well in

professional school as their White classmates, their

children and their children’s children may grow up

with interests, motivations and aptitudes that are not

dissimilar from those the rest of us grew up with,

and, consequently, may do as well in school as Whites

from similar backgrounds."

15.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

B . Neither the Equal Protection Clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment Nor the Privileges and

Immunities Clause of the California Constitution

Denies University Officials Discretion to Give

Special Consideration to a Reasonable Number of

Qualified Minority Applicants, When Such Con

sideration is Given for the Purposes of Promoting

Diversity in the School and the Profession and

Expanding Medical Education Opportunities for

Disadvantaged Members of Minority Groups_________

1. The Special Admissions Program Is Not Per Se

Unconstitutional, But Is Consistent With The

Purposes of The Equal Protection Clause_____

The lower court's announcement of intended decision

stated in sweeping terms the reasons for its finding that

the special admissions program denied equal protection of

_7/

the law:

"This Court cannot conclude that there is

any compelling or even legitimate public

purpose to be served in granting preference

to minority students in admissions to the

medical school when to do so denies white

persons an equal opportunity for admittance."

(CT 307:10-14)

7/ The trial court also found that the special admissions

program violated the Privileges and Immunities Clause of

the California Constitution (Article I, Section 21). How

ever, since the apposite California cases rely primarily

on Federal law and are consistent with the University's

discussion of Federal law, no separate discussion of

Article I, Section 21, is included herein. See, e.g.,

People, ex. rel. Lynch v. San Diego Unified School

District (1971) 19 C .A.3d 252; San Francisco Unified

School District v. Johnson (1971) 3~~cT. 3d 937, 95l7~

16.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

This too broad conclusion of the trial court that any racial

classification is unconstitutional per se, regardless of its

purpose or effect, simply cannot be squared with the Fourteenth

_ 8 /Amendment. It ignores the primary fact that the Fourteenth

Amendment arose out of an attempt to give Blacks special

_9 /

protection against discrimination.

As stated by the United States Supreme Court in

the Slaughter-House Cases (1872) 83 U.S. 395, 407, 21

L.Ed.59, 72:

". . . on the most casual examination of the

language of these amendments [13th, 14th,

and 15th] no one can fail to be impressed

with the one pervading purpose found

in them all, lying at the foundation of

each, and without which none of them would

have been even suggested; we mean the free

dom of the slave race, the security and

firm establishment of that freedom, and

8/ See Bickel, The Original Understanding and the

Segregation Decision', 69 Harvard L.Rev. 1, bO;

KurlandT~~EgaTitaria’nism and the Warren Court,

68 Mich, t."r^ 77~6?9T ~674.(T5TffyT~ ^ ^ 5i~r Y• ftesto O IXLx (J X1 • J~j • JAC: Vo ** s ̂* * ' — „ . - , » — —— •—

Virginia (18 79) 100 U.S. 303, 306-307 ; 25 L.Ed 664 ,

9/ The United States Supreme Court has expressly stated

that racial classificatons_are not unconstitutional

Hirabayashi v. United States (1943) 320 U.S3er se. ------ ---- - - TT . . .JIT Too, JTTTEd. 1774, 1786; ^ r ^ a ^ u j ^ J n ^

States (1944) , 323 U.S. 214, 216, 2137 59 L.Ed. 194,

199", 202 .

17 .

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

|

;

the protection of the newly made freemen [sic]

and citizen from the oppressions of those

who had formerly exercised unlimited

dominion over him. It is true that only

the 13th Amendment, in terms, mentions the

negro by speaking of his color and his

slavery. But it is just as true that each

of the other articles was addressed to the

grievances of that race, and designed to

remedy them as the fifteenth.

"We do not say that no one else but the

negro can share in this protection. Both

the language and spirit of these articles

are to have their fair and just weight in any

question of construction." (Underlining added.)

///

///

///

///

///

///

///

///

///

///

18.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

The trial court's decision also ignores the develop

ment of the Equal Protection Clause. Although just as

predicted in Slaughter-House Cases special protection has

been extended to discrimination against groups other than

Blacks, it has been so extended only with respect to classifi

cations the design or purpose of which was discrimination

10/

against "discrete and insular minorities" analogous to

Blacks. See, e.g., Yick-Wo v. Hopkins (1885) 118 U.S. 356,

373-374, 30 L.Ed. 220, 223 [Chinese immigrants]; Graham v .

Richardson (1971) 403 U.S. 365, 372, 29 L.Ed. 2d 534,

541-542 [aliens].

The situation is quite different when a racial

classification, such as the special admissions program at

issue here, has the same purpose and effect as the Fourteenth

Amendment itself, that is, to assist minorities and society

in overcoming the effects of past discrimination. As stated

by the Court of Appeals in Norwalk Core v. Norwaljc_Redgvelo£-

ment Agency (2d Cir. 1968) 395 F.2d 920, 931-2:

" . . . classification by race . . . is

something which the Constitution usually

forbids, not because it is inevitably an

impermissible classification, but because

it is one which . . . has been drawn for

10/ United States v. Carolene Products Company (1938) 304 U.S

1447 152/n7"Tr^2-L.Ed. 1234 , 1242, n. 4.

///

19.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

the purpose of maintaining racial inequality.

Where it is drawn for the purpose of achieving

equality it will be allowed, and to the extent

it is necessary to avoid unequal treatment by

race, it will be required,"

In San Francisco Unified School Dist. v, Johnson

(1971) 3 Cal. 937, 950, 951, this Court observed:

"It would be ironic, indeed, if the Fourteenth

Amendment, adopted to secure equality of

citizenship for the Negro, prevented school

boards from providing equality of education

for the Negro.

* * *

". . . .We conclude that the racial classifi

cation involved in the effective integration of

public schools, does not deny, but secures, the

equal protection of the laws."

Therefore, a finding that a classification favors

a minority group only begins the analysis of an equal

protection question and does not end it.

///

///

///

2 0 .

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

2. Racial Classifications Designed to Assist

Minorities Are Not Subject to the Same

Strict Scrutiny as Classifications

Directed Against Minorities________ ______

The general rule is that a classification will be sustained

against a claim of denial of equal protection if there is

any rational basis for it. See, e.g., Williamson v. Lee

Optical Company (1955) 348 U.S. 483, 99 L.Ed. 563. But the

courts have carved out a narrow exception to this rational

basis test for the protection of certain discrete and insular

minorities: When the classification is to the detriment of

such a minority it is called a "suspect" classification

requiring proof that the objective of the classification

serves a compelling state interest rather than merely any

rational state interest. See "Developments in the Law -

Equal Protection" (1969) 82 Harv. L.Rev. 1965; McLaughlin

v. Florida (1964) 379 U.S. 184, 13 L.Ed.2d 222; Loving v .

Virginia (1967) 388 U.S. 1, 18 L.Ed.2d 1010, 1020.

///

///

///

///

///

///

///

///

///

21.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

In extending the special "suspect classification"

protection to minority groups, the United States Supreme Court

carefully avoided a finding that advantaged Caucasians, like

Mr. Bakke, are entitled to this same special protection. The

Court has acted to strike down invidious discrimination, but

its decisions, considered in context, indicate that a racial

classification is invidious only to the extent it excludes,

disadvantages, isolates, or stigmatizes minorities or is

designed to segregate the races. See Brown v. Board of

Education (1954) 347 U.S. 483, 494, 98 L.Ed. 873, 880-81;

Loving v. Virginia (1967) 388 U.S. 1, 18 L.Ed. 2d 1010,

1020; McLaughlin v. Florida (1964) 379 U.S. 184, 13 L.Ed. 2d 222.

It is fanciful to argue that Mr. Bakke or other

non-minorities are stigmatized by feelings of inferiority

because of the special admissions program. And the purpose

of the special admissions program is to encourage integration

of the races in the medical school and in the profession.

(CT 67-69)

Other recent cases, without discussing distinctions

between the rational basis and compelling interest tests,

have assumed that affirmative attempts to equalize opportunity

for minorities are lawful and have made clear that the Equal

Protection Clause does not indiscriminately invalidate such

programs. In Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Boardof_Education-

(1971) 402 U.S. 1, 16, 28 L.Ed.2d 554, 566, the Court held

///

22.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

that school authorities may assign minority students to a

particular school so that the minority percentage of the

student body is the same as the minority percentage of the

whole population of the district and, in language especially

appropriate here, stated:

"School authorities are traditionally

charged with broad power to formulate

and implement educational policy and

might well conclude, for example, that

in order to prepare students to live in

a pluralistic society each school should

have a prescribed ratio of Negro to white

students reflecting the proportion for the

district as a whole. To do this as an

educational policy is within the broad

discretionary powers of school authorities ;

absent a finding of a constitutional

violation, however, that would not be

within the authority of a federal court."

(Underlining added.)

Similarly, in Porcelli v. Titus (3d Cir. 1970) 431

F.2d 1254, 1257, the Court held that a school board may give

preference to Black teachers over white teachers in order to

integrate the faculty and stated:

"State action based partly on considerations

of color, when color is not used per se,

23.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

and in furtherance of a proper governmental

objective, is not necessarily a violation

of the Fourteenth Amendment."

Cases such as Swann and Porcelli have established

that the Equal Protection Clause does not inflexibly require

that educators be blind to the special problems and needs of

minority groups. Other cases have gone even further and

held that where segregation results directly or indirectly

from past or present racially motivated public policies, the

Constitution requires favorable treatment of minorities.

For example, in Carter v. Gallagher (8th Cir. 1971) 452 F.2d

315, 331; cert, denied (1972) 406 U.S. 950, 32 L.Ed. 2d 338,

the Court stated:

"It would be in order for the District Court

to mandate that one out of every three

persons hired by the (Minneapolis] Fire

Department would be a minority individual

who qualifies until at least 20 minority

persons have been so hired."

See, also, People ex. rel. Lynch v. San Diego Unified School

District (1971) 19 C.A.3d 252, 261 and numerous cases therein

cited.

Thus, it appears clear that the compelling interest

exception to the normal rational basis test applies only to

discrimination against discrete and insular minorities.

But, in any event, the history and development of the

24.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

1 3

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

Fourteenth Amendment has established that where, as here,

the purpose and effect of a racial classification is to

assist such discrete and insular minorities that there is a

sufficient state interest to pass muster under the Equal

n /

Protection Clause.

///

///

///

///

///

///

///

///

///

///

///

///

///

///

///

/// ___________________ _____ ___ ____________ ___________

11/ It has been suggested that the United States Supreme

™ Court may be moving away from a rigid two-tiered

approach to equal protection. See, e.g., Gunther

The Supreme Court, 1971 Term - Forward: .In Search

olH E v o T v T m r D o ^

For "a- Newer Equal >rotec€xon7 SlTTflFv. ETRevT"!

( 1'9'7'2T; gaF~MFonIo TnHep . School District v .

Rodriguez (1973) 411 U.S. 1, 98-110, 36 L.Ed.2d 16

(Justice Marshall dissenting) .

25.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

1 3

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

3. The Efforts of the University to Assure That

Disadvantaged Members of Minority Groups Have

a Reasonable Representation in the Davis

Medical School and in the Medical Profession

Serve Rational and Compelling University Interests

The central fact which creates the need for the

special admissions program is that minority groups would

otherwise be grossly under-represented at the Davis Medical

School. Without the program there would be few, if any,

Blacks, Chicanos, or ative Americans at the School.

(CT 67:25-68:1) This is not a situation unique to the

Davis Medical School or to California. In 1970 only 2% of

American physicians were Black, 3.7% spoke Spanish or had

11/Spanish surnames, and .045% were Native Americans.

This gross under-representation of minorities

results in large measure, of course, from the effects of

past societal discrimination; and, although the University

of California has never had a policy of racial discrimination,

it is well recognized that such discrimination is part of

our nation's heritage, an "evil . . . which in varying

degrees manifests itself in every part of the country."

///

///

///

///

/ / / __________________ _____________________ _________________

12/ 1970 Census of Population: Occupational Characteristics -

U.S., Subject Report PC (2) , Table 2.

26.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

Oregon v. Mitchell (1970) 400 U.S. 112, 284, 27 L.Ed.2d

272, 373, The special admissions program is simply an

effort by the Davis Medical School to use its resources

to combat this evil and to serve the interests of the profession

and society at large by providing reasonable medical education

opportunities for qualified disadvantaged members of minority

groups and by bringing the advantages of diversity to the

School and the profession.

The special admissions program contributes to

overcoming the evils of racial injustice by permitting dis

advantaged minority persons to enter medical school and

eventually practice medicine. With these persons as role

models, younger disadvantaged minority persons will realize

that it is possible to aspire to a medical career. The

program will contribute to breaking the cycle of hopelessness

in which families do not improve their economic status or

.13/

educational achievements over generations. {CT 68:17-24)

Adequate medical service to disadvantaged, often

minority group persons is one of the great medical needs of

our society. For example, in 1970 in the primarily minority

area of East Los Angeles, there was one physician, dentist,

or related professional for every 5,236 persons, and in Pico

Rivera there was one such professional for every 4,526 persons.

13/ See J. Nickel, Preferential Policies in Hiring and Admis-

sions: A Jurisprudential Approach, 75 Colum. L.Rev. 524,

541 (19751

27.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

1 3

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

But in the affluent, primarily white communities of Beverly

Hills and Burlingame the ratio was one to 61 and one to 114,

11/respectively. The special admissions program is intended

to help correct this imbalance. Every applicant admitted to

the Davis Medical School under the special admissions program

has expressed an interest in serving a disadvantaged community.

(CT 68:14-16) See, also, Curtis, Blacks, Medical Schools,

and Society (1971) University of Michigan Press, 147.

Aside from putting more physicians where they are

most needed, the special admissions program will assist

treatment of the specific health problems of minorities. To

give just a few examples: Black physicians will have greater

rapport with Black patients and greater interest in treating

diseases which are especially prevalent among Blacks, such as

15,

sickle cell anemia, hypertension, and skin ailments. (CT 68:6-16)

The professors, students, and members of the

medical profession with whom the disadvantaged minority

student or doctor comes into contact will be influenced and

enriched by that contact. They will be exposed to the

ideas, needs, and concerns of disadvantaged minorities and

may themselves be enlisted in meeting the medical needs of

disadvantaged minority communities. (CT 62:22-28)

14/ 1970 Census of Population, General Social and Economic

Characteristics - California (PC(1) - C6), Tables 86 and

105.

15/ See E. Griswold, Some Observations on the DeFunis Case,

75 Colum. L.Rev. 512, 517.

28 .

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

Another important justification for the special

admissions program is that quantifiable data, such as test

scores and grades, do not necessarily reflect the capabilities

of disadvantaged minority persons- They may reflect inadequate

prior schooling which the applicant is only gradually over

coming. Poor grades may reflect the need to work long hours

to support the applicant or his family. Disadvantaged

minority applicants often lack the reinforcement and support

that others derive from more stable families. (CT 68:30-

69:6) See, e.g., R. O'Neill, Preferential Admissions,

Equalizing the Access of Minority Groups to Higher Education

(1971) 80 Yale Law Journal 699, 735; Kendrick, "Minority

Students on Campus" in The Minority Student on the Campus:

Expectations and Possibilities (1970) 46-49.

In DeFunis v. Odegaard (1973) 82 Wn.2d 11, 507

P .2d 1169, vacated as moot (1974) 416 U.S. 312, 40 L.Ed.2d

164, the Supreme Court of Washington specifically found that

a minority admissions program at the University of Washington

Law School, very similar to the special admissions program

at issue here, served compelling interests:

"We believe the state has an overriding

interest in promoting integration in

public education. In light of the serious

under-representation of minority groups in the

law schools, and considering that minority

groups participate on an equal basis in the

29.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

tax support of the law school, we find the

state interest in eliminating racial

imbalance within public legal education

16/to be compelling." (507 P.2d at 1187 .)*

And as stated by Justice Douglas in his opinion dissenting

from the United States Supreme Court's finding of mootness in

DeFunis v. Odegaard;

"I cannot conclude that the admissions pro

cedure of the Law School of Washington that

excluded DeFunis is violative of the Equal

Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amend

ment." (416 U.S. at 312, 40 L .Ed.2d at 185.)

///

///

/ / / ___________________________ ___________________ _

16/ In considering the case after vacation by the United States

Supreme Court, the Washington State Supreme Court enter

tained plaintiff's motion to convert the case to a class

action and a motion by the University of Washington to

reinstate the earlier decision of the State Supreme

Court.. The Court denied the motion to convert to a

class action. The University's motion to reinstate the

prior judgment would have been granted by the Court's

plurality opinion, but it appears that opinion was

concurred in by only four of the nine members of the

Court. (DeFunis v. Odegaard, 84 Wn.2d 617, 529 P.2d

438 (1974T"I ~But see PaciTTc 2d' s headnote, "The

Supreme Court . . . held . ... that the court would

reinstate its prior judgment." (529 P .2d at 438)

In any event, it is clear that on the constitutional

issue, six of the nine members of the Washington

Supreme Court have found the minority admissions program

to be valid.

30.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

The only appellate court, other than the Supreme Court of

Washington, to reach the merits of the issue also has upheld

the validity of such admissions practices. Alevy v. Downstate

Medical Center (Sup. Ct., 1974) 78 Misc.2d 1091, 359 N.Y.S.2d

426, aff'd without opinion (2d Dep., 1975) 47 A.D.2d 715,

366 N .Y .S.2d 390. As stated by the New York Court in

upholding a preference admissions program for the benefit

of disadvantaged Blacks and Puerto Ricans:

"There is nothing in the record to indicate

that acceptance of minority students by

respondent was based solely on race. On the

contrary, the testimony adduced in behalf of

respondent is that a minority student whose

low grades could not be attributed to

financial and educational disadvantage would

///

///

///

///

///

///

///

///

///

///

31.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

not be given the consideration given to the

disadvantaged. Furthermore, with respect to

minority applicants, educational, cultural,

and economic background and probability of

success in the program were considered. The

court is of the opinion that there is no bar

to considering an individual's prior achieve

ments in the light of his disadvantages,

culturally, economically and educationally,

as a factor in attempting to assess his true

potential in a successful career. The court

is of the further opinion, as expressed at

times by others, that standards of admission

need not be based on predetermined robot like

mathematical formulae. On the contrary,

educators should be free to assess the cre

dentials and the persons presenting them upon

entrance outside of test scores and formula

ratings. (359 N.Y.S.2d at 429.)

The special admissions program is a reasonable

effort to meet rational and compelling interests. Applicants,

including all minorities, are admitted only if they are fully

qualified to successfully complete the course of study and

become competent physicians. (CT 67:9-13) The decision to

reserve 16 seats under the special admissions program was

made after deliberation by the faculty (CT 164:14-18), and is

32.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

far below the percentage of disadvantaged minorities in the

17/

California population. It is the judgment of the faculty

at the Davis Medical School that the special admissions

program is the only method whereby the School can produce a

diverse student body which will include qualified minority

students. (CT 67:14-18; CT 67:28-68:1)

The Fourteenth Amendment was passed to help insure

that all Americans stand equal before the law. Experience

has taught, however, that where the law is strictly neutral

racism and prejudice often hold sway. Statutes and court

decisions which ended segregation in public schools, and

which guaranteed voting rights, access to public accommo

dations, and housing all constituted steps whereby the power

of the state was used affirmatively to combat discrimination

and make the promise of the Fourteenth Amendment a reality.

Here, the University is merely using its lesser power in a

less dramatic way to achieve that same purpose in the Davis

Medical School and in the medical profession. If such

affirmative steps cannot be taken there will be few, if any,

members of certain minority groups who will become doctors.

This will be the loss of the School, the profession and

society.

I L L __________________-_________________________________ _________

17/ See 1970 Census of Population: Detailed Characteristics -

California (PC(1) - D6), Table 139. Approximately 7%

of the Californians are Black, and 16% Spanish speaking

or Spanish surnamed.

33.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

II. THE ADMISSIONS STANDARDS USED BY THE DAVIS MEDICAL

SCHOOL ARE PERMITTED BY TITLE VI OF THE CIVIL

RIGHTS ACT OF 1964 ________________________

The trial court found that the special admissions

program at the Davis Medical School violates Title VI of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964 [42 U.S.C. § 2000(d)]. (CT 390:14-

20; 394:14-20) It states:

"No person in the United States shall, on

the ground of race, color, or national

origin, be excluded from participation in,

be denied the benefits of, or be subjected

to discrimination under any program or

activity receiving federal financial

assistance.11

Implementing regulations issued under 42 U.S.C § 2000(d) by

the Department of Health, Education and Welfare provide that

recipients of federal financial assistance, such as the

University of California,

" . . . may properly give special considera

tion to race, color or national origin

to make the benefits of its program

more widely available. . ." (38 Fed. Reg.

17979, July 9, 1973, 45 C.F.R. § 80.5 (j) .

Those regulations further provide:

"In administering a program regarding which

the recipient has previously discriminated

against persons on the ground of race, color

34.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

or national origin, the recipient must take

affirmative action to overcome the effects

of prior discrimination. Even in the absence

of such prior discrimination a recipient in

administering a program may take affirmative

action to overcome the effects and conditions

which resulted in limiting participation by

persons of a particular race, color or

national origin. 38 Fed. Reg. 17979,

July 5, 1973 , 45 C.F.R. § 80.3(b) (vii) (6) ;

made applicable to admissions at 45 C.F.R.

§ 80.4(d)(1) and (2) and at 45 C.F.R. § 80.5(e).

In Lau v. Nichols (1974) 414 U.S. 563, 39 L.Ed.2d 1,

the United States Supreme Court upheld similar provisions of

these same regulations and required the City of San Frncisco

to give special bilingual education to students of Chinese

ancestry who do not speak English.

In light of the foregoing, it is apparent that the

special admissions program clearly does not violate Title VI

of the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and, indeed, the regulations

issued under that Act specifically permit giving special

consideration to minority group members in admissions for

the purpose of increasing their participation in educational

programs.

///

35.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

1 3

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

III. THE TRIAL COURT CORRECTLY FOUND THAT BAKKE WOULD NOT

HAVE BEEN ADMITTED EVEN IF THERE HAD BEEN NO SPECIAL

ADMISSIONS PROGRAM_________ ________________ __

The trial court carefully reviewed the evidence on

whether Bakke would have been admitted had there been no

special admissions program and found

" . . . that even if 16 positions had not

been reserved for minority students in

each of the two years in question, plaintiff

still would not have been admitted in

either year. Had the evidence shown that

plaintiff would have been admitted if the

16 positions had not been reserved, the

Court would have ordered him admitted."

(CT 383:20-26)

Bakke's applications for admission to classes

beginning 1973 and 1974 were processed and evaluated in the

same way as those of every other applicant seeking admission

through the regular admissions program. (CT 69:11-13) It is

unfortunate that the competition for the few available

spaces in each year's class is so intense that applicants

with credentials such as Bakke's must be turned away. However,

the competitive situation is by no means limited to the Davis

Medical School; although Plaintiff applied to 10 medical

schools for 1973 and two other medical schools for 1972 he

was admitted nowhere. (CT 48:25-49:14; 51:14-19)

36.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

For the class beginning in 1973, Bakke's file was

not received and processed at the Davis Medical School in

the normal course until after the March 14, 1973 mailing of

acceptances, at which time 123 of the 160 acceptances,

including 24 of the 32 acceptances under the special admissions

program, had already been mailed. (CT 69:18-23) Bakke's

combined numerical rating of 468 was two points lower than

any applicant accepted under the regular admissions program

after his evaluation was completed. (CT 69:23-26)

At that time only four of the sixteen spaces

reserved under the special admissions program remained

unfilled. (CT 70:2-3) If we assume that the four spaces

reserved under the special admissions program had been open

to regular applicants, Bakke would not have been among those

accepted. There were 15 interviewees with scores of 469 and

20 interviewees with scores of 468 who had not been accepted

at the time Bakke's evaluation was complete and who would

have been selected ahead of Bakke. (CT 70:4-30)

Even if we assume that all 16 of the spaces

reserved under the special admissions program had been open

at the time Bakke's application was complete, he still would

not have been among the 16 selected. There were 15

unaccepted interviewees with scores of 469, and 20 with

scores of 468. Bakke was not among the 20 interviewees with

scores of 468 likely to have been selected, even assuming

the selection process had gotten down that far, because he

37 .

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24