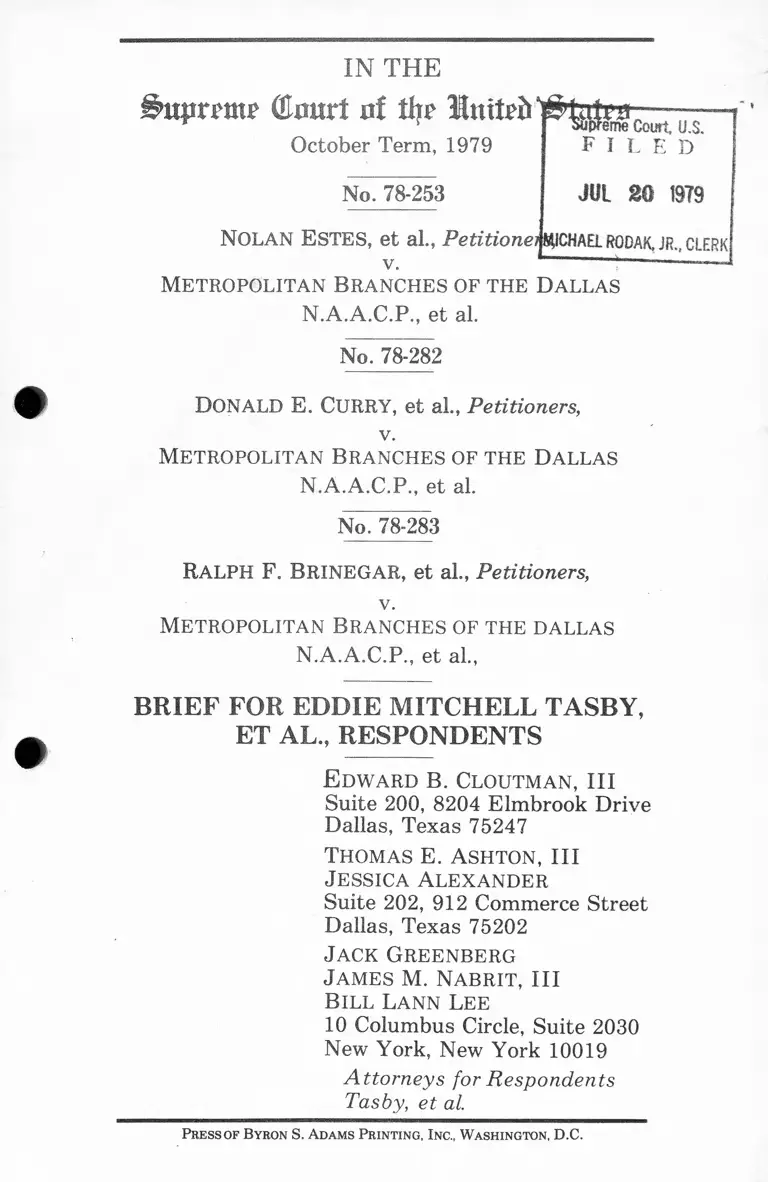

Estes v. Dallas NAACP Brief for Eddie Mitchell Tasby

Public Court Documents

July 20, 1979

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Estes v. Dallas NAACP Brief for Eddie Mitchell Tasby, 1979. 004fbf11-b19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c12beb37-126f-4c33-8c7a-f416859eac56/estes-v-dallas-naacp-brief-for-eddie-mitchell-tasby. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

^itpriw (Emirt ni % us

October Term, 1979 F I L E D

No. 78-253

Nolan E stes, et al., Petitioner siichael rodak, jr„ clerk

v.

Metropolitan B ranches of the Da llas

N.A.A.C.P., et al.

No. 78-282

Donald E. Cu r r y , et a l, Petitioners,

V.

M etropolitan Branches of the Dallas

N.A.A.C.P., et al.

No. 78-283

Ralph F. BRINEGAR, et al., Petitioners,

v.

Metropolitan B ranches of the Dallas

N.A.A.C.P., et al.,

BRIEF FOR EDDIE MITCHELL TASBY,

ET AL., RESPONDENTS

E d w ard B. Clou tm an , III

Suite 200, 8204 Elmbrook Drive

Dallas, Texas 75247

Thom as E. A shton , III

Jessica A lexa n d e r

Suite 202, 912 Commerce Street

Dallas, Texas 75202

Jack Green berg

Jam es M. Na b r it , i l l

B ill Lann Lee

10 Columbus Circle, Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

Att07'neys for Respondents

Tasby, et al.

Press of Byron S. A dams Printing, Inc., Washington, D.C.

INDEX

Table Of Authorities............................................... iii

Opinions Below ............................................................ 2

Jurisdiction.................................................................. 4

Constitutional And Statutory Provisions

Involved. ............................................................. 4

Questions Presented ................................... 5

Statem ent ............................ 6

I. Introduction and Summary of Proceedings . 6

II. The 1971 Proceedings on the Issue of the

Constitutional Violation............................... 13

III. The 1971 Remedy Hearing; Desegregation

Proposals................................. 30

A. Plaintiffs’ Proposal—the TEDTAC

Plan..................... 30

B. The DISD Plan and the Court-Ordered

Plan........................................................ 34

IV. The 1976 Remedy Hearing:..................... 41

A. The DISD Plan, the Hall Plan, Plaintiffs’

Plans A & B, the NAACP Plan................ 41

B. Court-Ordered Plan—Dallas Alliance

Concept as Developed by DISD. . . . . . . . 47

V. The 1978 Fifth Circuit Decision............. 55

Summary Of Argument........................................... 57

Page

Argument

I. The District Court Properly held that the

DISD was not a Desegregated Unitary

System in 1970-71 ........................................ 62

II. The Court of Appeals was Correct in

Deciding that the Court-Adopted

Desegregation Plan Failed to Comply with

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board o f

Education, 402 U.S. 1 (1971). .......... . 76

A. The District Court Erred in Refusing to

Use Affirmative Integration Measures

such as Pairing, Rezoning, or Transpor

tation in the Primary Grades and High

School Grades......................................... 81

B. The District Court Erred in Establishing

the Segregated East Oak Cliff Sub

district ............. 92

III. The Arguments of the Brinegar and Curry

Petitioners for a Modification or Overruling

of Swann should be Rejected .................... 97

A. The Brinegar and Curry Arguments that

Certain Neighborhoods must be exemp

ted from Participation in a Desegrega

tion Plan are without Merit......... 97

B. The Curry Petitioners’ Argument for an

Overruling of Swann should be

Rejected......................................................... 99

Conclusion ....................... 102

11

Page

Ill

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases: Page

Alexander v. Holmes County Board of Ed., 396 U.S.

19(1969).......................................... .............. . 63

Adickes v. Kress & Co., 398 U.S. 144 (1970)......... 70

Allen v. Board of Pub. Inst, of Broward County, 432

F.2d 362 (5th Cir. 1970), cert, denied 402 U.S. 952

(1971). . . ....................... 80

Arvizu v. Waco Independent School District, 495 F.2d

499 (5th Cir. 1974) rehearing 496 F.2d (1974) . . 79, 82

Austin Independent School Dist. v. United States,

429 U.S. 990(1977)....................... 71

Bell v. Rippy, 133 F. Supp. 811 (N.D. Tex. 1955)........ 3

Bell v. Rippy, 146 F. Supp. 485 (N.D. Tex. 1956) . . . . 4,13

Bivins v. Board of Public Ed., 342 F.2d 229 (5th Cir.

1965) . ................................................................... 16

Borders v. Rippy, 184 F. Supp. 402 (N.D. Tex.

1960) ........................ ..............................4,7,57,63

Borders v. Rippy, 188 F. Supp. 231 (N.D. Tex.

1960) .................................. 4,7-8

Borders v. Rippy, 195 F. Supp. 732 (N.D. Tex.

1961) ............... ..................................... 4,8, 15

Borders v. Rippy, 247 F.2d 268 (5th Cir. 1957).......... 4,13

Boson v. Rippy, 275 F.2d 850 (5th Cir. 1960).............. 4

Boson v. Rippy, 285 F.2d 43 (5th Cir. 1960).............. 4, 15

Bradley v. School Board, 382 U.S. 103 (1965).......... 24, 58

Britton v. Folsom, 348 F.2d 158 (5th Cir. 1965)........ 4, 16

Britton v. Folsom, 350 F.2d 1022 (5th Cir. 1965) . . . . 4,16

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483

<1954>................................................. 13,27,57,62,63

Brown v. Rippy, 233 F.2d 796 (5th Cir. 1956), cert,

denied 352 U.S. 878 (1956) .................................... 3

Carter v. West Feliciana Parish School Board, 396

U.S. 226(1969)___ . . . . . ....... . .......................... 58

Columbus Board of Education v. Penick, _ __ U.S.

----- (July 2,1979).............. 59, 67, 68, 70, 97, 98

Davis v. Board of School Commissioners of Mobile

County, 393 F.2d 690 (5th Cir. 1968)................ 58, 64

Davis v. Board of School Commissioners of Mobile

County, 402 U.S. 33 (1971)................ 5, 58, 62, 76, 77

Davis v. Board of School Commissioners of Mobile

iv

Page

County, 414 F.2d 609 (5th Cir. 1969). .............. 58, 64

Davis v. East Baton Rouge School Board, 570 F.2d

1260 (5th Cir. 1978)............................... 79

Dayton Board of Education v. Brinkman, 433 U.S.

406(1977) . . . ............................................. 70,71,72

Dayton Board of Education v. Brinkman, ___ U.S.

----- (July 2, 1979). . . . ............ 59,70,97

Ellis v. Board of Pub. Inst. Orange County, Fla., 465

F.2d 878 (1972) cert, denied 410 U.S. 966

<1973)............................................................ 67,79

Flax v. Potts, 464 F.2d 865 (5th Cir.), cert, denied 409

U.S. 1007(1972)........... 79)82

Gaines v. Dougherty County Board of Ed., 465 F.2d

363 (5th Cir. 1972)................................................. 79

Green v. County School Board, 391 U.S. 430

<1968>............................... 58,62,69,70,72,74,90,93

V

Page

. 62Griffin v. School Board, 377 U.S. 218 (1964)

Hereford v. Huntsville Bd. of Ed., 504 F.2d 857 (5th

Cir. 1974), cert, denied 421 U.S. 913 (1975).... 68,

Keyes v. School District No. 1, 413 U.S. 189

(1973)................. 59,67,97,

Lee v. Autauga County Board of Ed., 514 F.2d 646

(1975)....................................................................

Lee v. Demopolis City School System, 557 F.2d 1053

(5th Cir. 1977), cert, denied 434 U.S. 1014

(1978)........................... .......................................

Lee v. Macon County Board of Ed. (Calhoun County),

448 F.2d 746 (5th Cir. 1971).................................

Lee v. Macon County Board of Ed. (Merengo County)

465 F.2d 369 (5th Cir. 1972).................................

Lee v. Tuscaloosa City School System, 576 F.2d 39

(5th Cir. 1978).................. 68,

Lemon v. Bossier Parish School Board, 566 F.2d 985

(5th Cir. 1978).....................................................

Lockett v. Board of Education of Muscogee County,

342 F.2d 225 (5th Cir. 1965).................................

Lockett v. Board of Education of Muscogee County,

447 F.2d 472 (5th Cir. 1971).................................

Miller v. Board of Ed. of Gadsden, 482 F.2d 1234 (5th

Cir. 1973)...................................... 68,

Mills v. Polk County Board of Public Instruction, 575

F.2d 1146 (5th Cir. 1978)................................. 79,

Monroe v. Board of Commissioners of City of Jackson,

Tenn., 391 U.S. 450 (1968)...................................

69

98

68

79

79

79

79

79

16

82

79

82

72

VI

Pasadena City Board of Ed. v. Spangler, 427 U.S. 424

(1976)..................... ............................................. 71

Raney v. Board of Education of the Gould School

Dist., 391 U.S. 443 (1968)........................ . . . . . . 72

Rippy v. Borders, 250 F.2d 690 (5th Cir. 1957)............ 4

Rogers v. Paul, 382 U.S. 198 (1965)....................... . 24

Singleton v. Jackson Mun. Sup. School Dist., 348 F.2d

729 (5thCir. 1965). . . . . . . . . .............................. 16

Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School

District, 419 F.2d 1121 (5th Cir. 1969) . . . . . . . 24, 58

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

402 U.S. 1 (1971). .......................................... passim

Tasby v. Estes, 342 F. Supp. 945 (N.D. Tex. 1971) 2, 25, 77

Tasby v. Estes, 572 F.2d 1010 (5th Cir. 1978) rehear

ing denied 575 F.2d 300 ............................ . 3

Tasby v. Estes, 416 F. Supp. 644 (N.D. Tex. 1976).... 3

Tasby v. Estes, 412 F. Supp. 1185 (N.D. Tex.

1975) ................................................................ 3, 13

Tasby v. Estes, 412 F. Supp. 1192 (N.D. Tex.

1976) ................................................................. . 3

Tasby v. Estes, 444 F.2d 124 (5th Cir. 1971)................2, 20

Tasby v. Estes, 517 F.2d 92 (5th Cir. 1975), cert.

denied 423 U.S. 939 (1975)................. 2,7,20,78,79

Thompson v. School Board of City of Newport News,

Virginia, 465 F.2d 83 (4th Cir. 1972), cert, denied

413 U.S. 920 (1973)....................... ...................... 82

Thompson v. School Board of City of Newport News,

498 F.2d 195 (4th Cir. 1974)

Page

82

V ll

United States v. Board of Ed. of Valdosta, Georgia,

576 F.2d 37 (5th Cir.), cert, denied 99 S.Ct. 622

(1978).......................................... 68,71,79,95

United States v. Columbus Mun. Sup. School Dist.,

558 F.2d 228 (5th Cir. 1977) cert, denied 434 U.S.

1013(1978).......................................................... 68

United States V. DeSoto Parish School Board, 574

F.2d 804 (5th Cir.) cert, denied 99 S.Ct. 571

(1978).......................................................... 68,79

United States v. Montgomery County Board of

Education, 395 U.S. 225(1969).......................... 58

United States v. Scotland Neck Board of Education,

407 U.S. 484 (1972)............................................... 96

United States v. Seminole County Sch. Dist., 553 F.2d

992 (5th Cir. 1977)....................................... 68,71,80

United States v. South Park Ind. Sch. Dist., 566 F.2d

1221 (5th Cir.), cert, denied 99 S.Ct. 622

(1978)................................................................ 68,79

United States v. Texas Education Agency (Austin

Ind. Schl. dist., 532 F.2d 380 (5th Cir. 1976) . . . . . 82

United States v. Texas Education Agency (Richard

son Ind. Sch. Dist.), 512 F.2d 896 (5th Cir.

1975)............................................ 78

Washington v. Davis, 426 U.S. 229 (1976).............. 70, 71

Weaver v. Board of Public Inst., 467 F.2d 473 (5th Cir.

1972), cert, denied 410 U.S. 982 (1973).................. 79

Wright v. Council of City of Emporia, 407 U.S. 451

(1972) . . . . . ...................... .... ............................... 96

Page

V l l l

Constitutional Provisions and Legislative

History:

United States Constitution, Thirteenth

Amendment ........................................... 7

28 U.S.C. § 1331

§ 1343(3) & (4). ......... 7

42 U.S.C. §1981

§1983

§1988

§200Qc-8

§2000d ......................................................... 7

Texas Acts 1969, 61st Leg., p. 361, ch. 129 § 1 (effec

tive Sept. 1,1969) ................................................. 14

Texas Acts 1969, 61st Leg., p. 1669, ch. 532 § 2 (effec

tive June 10, 1969)..................... 15

Texas Acts 1969, 61st Leg., p. 3024, ch. 889 § 2 (effec

tive Sept. 1,1969).............................. . 13,14

Texas Acts 1969, 61st Leg., p. 179, ch. 75 § 4 (effective

Sept. 1,1969)......................................................... 14

Texas Constitution Art. 7, § 7 (1876) (repealed Aug. 5,

1969)......... 13

Texas Rev. Stat. Ann. Art. 2691 (Vernon 1965)

enacted 1905 ........................................................ 13

Texas Rev. Stat. Ann. Art. 2695 (Vernon 1965)

enacted 1905 ..................... ............................... • 13

Rex. Rev. Stat. Ann. Art. 2719 (Vernon 1965) enacted

1923...................................................................... 14

Texas Rev. Stat. Ann. Art. 2755 (Vernon 1965)

enacted 1965

Page

14

IX

Page

Texas Rev. Stat. Ann. Art. 2816 (Vernon 1965)

enacted 1905 ........................................................ 14

Texas Rev. Stat. Ann. Art. 2817 (Vernon 1965)

enacted 1905 ........................................................ 14

Texas Rev. Stat. Ann. Art. 2819 (Vernon 1965)

enacted 1911 ............................................. 14

Texas Rev. Stat. Ann. Art. 2893 (Vernon 1965)

enacted 1915 ..................... 14

Texas Rev. Stat. Ann. Art. 2900 (Vernon 1965)

enacted 1905 ............. 14

Texas Rev. Stat. Ann. Art. 2900a (Vernon 1965)

enacted 1957 ............................................. 15

Texas Rev. Stat. Ann. Art. 3901a (Vernon 1965)

enacted 1957 ................. 15

Other Authorities:

Robert Crain and Rita Mahard, “ Desegregation and

Black Achievement,” Law and Contemporary

Problems, Vol. 42 (Spring and Summer 1978). 85, 100

J. Freund, MODERN ELEMENTARY STATISTICS

421-22 (4th ed. (1973))............... 24

Christine Rosell, “ The Community Impact of School

Desegregation: A Review of the Literature,” Law

and Contemporary Problems, Vol. 42 No. 2

(Spring 1978)........................................................ 99

Report of the Select Committee on Equal Educational

Opportunity, 92nd Cong., 2d Sess. Senate

Report, No. 92-000; December 31, 1972, Table

7016, p. 117....................... 23

X

Page

U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, DESEGREGATION

Of The Nation’s Public Schools: A Status

Report, p. 20 (Feb. 1979)........................ . 101

IN THE

duprrot? (Emirt nf tlyr States

October Term, 1979

No. 78-253

NOLAN ESTES, et al., Petitioners,

v.

Metropolitan Branches of the Dallas

N.A.A.C.P., et al.

No. 78-282

DONALD E. Curry , et al., Petitioners,

V.

Metropolitan Branches of the Dallas

N.A.A.C.P., et al.

No. 78-283

RALPH F. BRINEGAR, et al, Petitioners,

v.

Metropolitan Branches of the Dallas

N.A.A.C.P., et al,

BRIEF FOR EDDIE MITCHELL TASBY,

ET AL., RESPONDENTS

2

OPINIONS BELOW

I. The principal opinions and orders in this case

are as follows:

1. Memorandum Order denying preliminary in

junction on school construction filed December 15,

1970, unreported.

2. Order of Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

June 3,1971, vacating order as to school construction,

Tasby v. Estes, 444 F.2d 124 (5th Cir. 1971).

3. Memorandum Opinion filed July 16, 1971 on

violation issue, Tasby v. Estes, 342 F.Supp. 945 (N.D.

Tex. 1971).

4. Judgment entered August 2, 1971, unre

ported.

5. Supplemental Order for Partial Stay of Judg

ment, filed August 9, 1971, reported at 342 F.Supp.

949.

6. Memorandum Opinion on Final Desegregation

Order, filed August 17, 1971, reported at 342 F. Supp.

949.

7. Supplemental Opinion regarding Partial Stay

of Desegregation Order, filed August 17, 1971, re

ported at 342 F. Supp. 955.

8. Opinion of court of appeals filed July 23, 1975,

Tasby v. Estes, 517 F.2d 92 (5th Cir.), cert, denied

423 U.S. 939 (1975).

3

9. Memorandum Opinion and Order denying in

terdistrict relief, filed December 11, 1975, Tasby v.

Estes, 412 F.Supp. 1185 (N.D. Tex. 1975).

10. Opinion and Order on school desegregation

plans filed March 10, 1976, Tasby v. Estes, 412

F.Supp. 1192 (N.D. Tex. 1976).

11. Supplemental Opinion and Final Order on de

segregation plan filed April 7, 1976, reported in part

at 412 F.Supp. 1210. (N.B: The reported opinion omits

the important appendices to the Final Order which

detail the court-ordered plan. This portion is reprinted

in the Appendix to the Petition for Certiorari in No.

78-253 at pp. 84a-125a; and see corrections at 127a-

129a.)

12. Memorandum Opinion granting plaintiffs at

torneys fees, filed July 20, 1976, Tasby v. Estes, 416

F.Supp. 644 (N.D. Tex. 1976).

13. Opinion of Court of Appeals for the Fifth Cir

cuit filed April 21, 1978, Tasby v. Estes, 572 F.2d

1010 (5th Cir.), rehearing denied 575 F.2d 300 (1978).

II. The reported opinions in a prior desegregation

case against the Dallas Independent School District

which was litigated from 1955 to 1965 are as follows:

1. Bell v. Rippy, 133 F.Supp. 811 (N.D. Tex.

1955).

2. Brown v. Rippy, 233 F.2d 796 (5th Cir. 1956),

cert, denied 352 U.S. 878 (1956).

4

3. Bell v. Rippy, 146 F.Supp. 485 (N.D. Tex,

1956).

4. Borders v, Rippy, 247 F.2d 268 (5th Cir. 1957).

5. Rippy v. Borders, 250 F.2d 690 (5th Cir. 1957).

6. Boson v. Rippy, 275 F.2d 850 (5th Cir. 1960).

7. Borders v. Rippy, 184 F.Supp. 402 (N.D. Tex.

1960).

8. Borders v. Rippy, 188 F.Supp. 231 (N.D. Tex.

1960) .

9. Boson v. Rippy, 285 F.2d 43 (5th Cir. 1960).

10. Borders v. Rippy, 195 F. Supp. 732 (N.D. Tex.

1961) .

11. Britton v. Folsom, 348 F.2d 158 (5th Cir.

1965).

12. Britton v. Folsom, 350 F.2d 1022 (5th Cir.

1965).

JURISDICTION

The jurisdictional requisites are adequately set

forth in the briefs for petitioners.

CONSTITUTIONAL AND STATUTORY

PROVISIONS INVOLVED

The constitutional and statutory provisions in

volved are adequately set forth in petitioners’ briefs.

5

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Respondents Tasby et alM the original plain

tiffs, believe that the question presented herein in as

follows:

Whether the court of appeals properly remanded

the case for a new pupil assignment plan and for

further findings where:

a. The district court ordered the desegregation

of a de jure segregated school system under a plan

which has resulted in three-fifths of Dallas’ Black

pupils still attending virtually all-Black schools, and

b. The court-ordered plan leaves the primary

grades (1-3) and high school grades (9-12) largely seg

regated by failing to attempt techniques of rezoning,

pairing or transportation to achieve effective deseg

regation of those grades although such methods are

used in Grades 4-8, and

c. The plan carves out a segregated “ subdistrict”

within the school system in the all-Black East Oak

Cliff section of Dallas thus leaving all grades segre

gated in this area, and

d. The district court failed to make appropriate

findings under Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg

Board of Education, 402 U.S. 1, 26 (1971) and Davis

v. School Commissioners o f Mobile County, 402 U.S,

33, 37, (1971) to demonstrate that it had achieved

“ the greatest possible degree of actual desegregation,

taking into account the practicalities of the situation”

6

or that remaining one-race schools are “ not the result

of present or past discriminatory action” on the part

of the school district.

2. The Brinegar group of petitioners and the Cur

ry group of petitioners, interveners below, have stated

other questions including:

a. Whether the district court’s 1971 finding of a

constitutional violation, which the School District

never appealed, was correct.

b. Whether certain all-White or integrated neigh

borhoods, e.g., North Dallas and East Dallas, should

be exempted from the desegregation plan.

STATEMENT

I. Introduction and Summary of Proceed

ings.

This suit was commenced October 6, 1970, by re

spondents Tasby, et al., a group of Black and Mexi-

can-American parents on behalf of 20 children attend

ing pupil schools in the Dallas Independent School

District (DISD), seeking an injunction requiring a

comprehensive plan for the desegregation of the dis

trict. The complaint alleged that the DISD operated

for years under a “ de jure segregated attendance

plan” , that the current operation “ basically continued

the de jure segregation of its schools” , and the de

fendants have “ perpetuated the effects of the de jure

tri-system and have not carried out their duty to dis

7

mantle the segregated school system ‘root and

branch’ Complaint p. 6. The complaint alleged that

the district’s practices violated the Fourteenth

Amendment and the civil rights statutes1 and invoked

the civil rights and federal question jurisdiction of the

United States District Court for the Northern District

of Texas.2

The DISD had been sued in a prior case brought in

1955 to desegregate the district. See Opinions Below

Part II, supra. That case ended with a 1965 order

requiring a desegregation plan based on attendance

area pupil assignments which was to be effective in

all grade levels by September 1967.3 The prior litiga

tion is briefly summarized in the Fifth Circuit’s 1975

decision in this case. Tasby v. Estes, 517 F.2d 92, 95

(5th Cir. 1975). It required seven appeals to the Fifth

Circuit for the plaintiffs in that case to obtain an

order for a stair-step plan to eliminate segregation

under an overt dual system. The opinions in the case

by the late District Judge T. Whitfield Davidson are

remarkable for their frank espousal of a philosophy of

white supremacy and “ racial purity” and their praise

of slavery. See e.g., Borders v. Rippy, 184 F.Supp.

402, 405-409, 415-416 (N.D. Tex. 1960); Borders v.

1 The complaint also invoked the Thirteenth Amendment and

42 U.S.C. sections 1981, 1983 and 2000d.

2 Jurisdiction was alleged under 28 U.S.C. §§1331, 1343(3) and

(4); 42 U.S.C. §§1981, 1983, 1988, 2000c-8 and 2000d. See Com

plaint p. 1 and First Amended Complaint.

3 There were no proceedings in the case following the 1965

Order. See discussion, infra pp. 12-13.

8

Rippy, 188 F.Supp. 231 (N.D. Tex. 1960); Borders v.

Rippy, 195 F.Supp. 732 (N.D. Tex. 1961).

When the Tasby case was filed the DISD initially

defended on the ground that it was in compliance with

the constitutional requirements by virtue of having

obeyed Judge Davidson’s 1965 order. After a trial

limited to the issue of whether or not the DISD was

in compliance the district court on July 16, 1971 is

sued an opinion finding that extensive segregation of

Black and White students continued and that “ ele

ments of a dual system still remain” . 342 F.Supp. at

947. This finding of violation has never been appealed

by the DISD which did file an appeal on remedy is

sues. It was challenged on appeal by the Curry inter-

venors, a group of White parents from North Dallas,

who were granted leave to intervene on July 22, 1971,

after the completion of the trial on the violation issue

and the filing of the court’s opinion. The DISD has,

however, sought to minimize the extent of the viola

tion which existed and the extent of the trial court’s

findings. A more detailed description of the evidence

and findings on the violation is set forth in part II of

this statement below.

After finding a constitutional violation the district

court heard evidence on desegregation plans proposed

by the plaintiffs and defendants. The plaintiffs offered

a plan prepared by a team of experts from the Texas

Educational Desegregation Technical Assistance Cen

ter (TEDTAC). This plan would have desegregated

every school in the District by rezoning secondary

9

schools, and by pairing and grouping attendance

zones at the elementary level. On August 2, 1971 the

court ordered a limited desegregation plan. The Order

provided for only televised integration at the elemen

tary school level, approving the DISD’s elaborate ten

million dollar proposal for Black and White children

to participate in simultaneous instruction by two-way

television connections between their segregated

schools for a few hours each week. The plan also pro

vided for one weekly visit or joint activity of Black

and White pupils. The television plan was promptly

stayed by the Fifth Circuit at the request of the plain

tiffs and was never implemented. At the secondary

level, the district judge ordered some busing of Black

students to formerly White schools in certain neigh

borhoods located closest to the Black ghetto in South

Dallas. Initially in the August 2nd order the district

court ordered a more extensive high school desegre

gation plan with a pairing arrangement. But following

“ a public furor” —to use the Fifth Circuit’s phrase

(517 F.2d at 100)—the district court on August 9,

1971 stayed the high school plan on its own motion.

That high school plan was subsequently abandoned

by the district court in favor of a DISD proposal

involving the satelliting of a small number of Black

pupils to formerly White schools and the zoning of

small numbers of Whites into all-Black schools.

Cross appeals by the parties were orally argued in

the Fifth Circuit on December 2, 1971, but the case

was not decided by that court until July 23, 1975,

10

about 4 years after the district court’s judgment.

Thus at the elementary school level there was no de

segregation except that obtained under Judge Dav

idson’s 1965 order. Desegregation in secondary

grades was quite limited and in accordance with the

DISD ’s own proposal.

On July 23, 1975 the Fifth Circuit reversed the

judgment insofar as it approved the desegregation

plan, and ordered the formulation of a new student

assignment plan. 517 F.2d 92. The court found the

television plan insufficient because it “ does not at

tempt to alter the racial characteristics of the DISD’s

elementary schools’ ’. 517 F.2d at 104. The appellate

court rejected the high school plan because it found

that the DISD had attempted only the limited objec

tive of reducing the proportionate share of any racial

group’s population in a high school to a point just

below the 90% mark so that the school would not be

categorized as a “ one race” school. The court of ap

peals rejected the idea that the 90% mark was a “ mag

ic level” of compliance and said the plan fell short of

“ a bona fide effort to comply with the mandates of

the Supreme Court” . 517 F.2d at 104. The Fifth Cir

cuit rejected the Curry intervenors’ argument that

their North Dallas area should be insulated from the

plan because it was a newly developed community.

517 F.2d at 108.

On remand, the district court considered six deseg

regation plans presented by the parties and amici.

Four of the six plans included detailed pupil assign

11

ment arrangements and projections. They differed

considerably in the extent of desegregation proposed.

Plaintiffs’ expert witness Dr. Willie compared the

DISD plan with the plaintiffs’ two plans, and a plan

designed by Dr. Josiah Hall, the court appointed ex

pert. Using a rule of thumb that labeled schools still

segregated if their Anglo or minority populations ex

ceeded 70%, Dr. Willie’s comparison of the four plans

was as follows:

Segregated

Elementary

Segregated

Junior Highs

Segregated

Senior Highs

DISD Dr. Hall P i 's Plan A P i 's Pli

9 8 b9 2 23

1 J 8 0 4

11 _5 ]_

122 82 3 28

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit 14.

The plans filed by the Dallas NAACP and by the

Educational Task Force of the Dallas Alliance con

tained general outlines of pupil assignment patterns.

The NAACP plan contemplated that all schools would

more or less reflect the district wide Anglo-minority

ration with a 10% variance up or down. The Dallas

Alliance plan provided the concepts which the court

eventually adopted. The proposal left the assignments

in the lowest grades (K-3) and the high school grades

(9-12) virtually unchanged. Desegregation at those

levels was limited to voluntary transfers. The concept

provided for a desegregated pattern in grades 4-6 in

1 2

one set of schools and 7-8 in other schools using trans

portation and satellite zoning. The plan created an all-

Black subdistrict in the East Oak Cliff section in

which there would be no desegregated schools.

The court approved the Dallas Alliance concept and

ordered the DISD to plan the assignment details,

which were eventually incorporated in the Final Order

entered April 7, 1976. The plan left over 27,000 pupils

in 26 all-Black schools in the East Oak Cliff subdis

trict, plus more than 40 one-race schools in the other

subdistricts. See Appendix A to Final Order; Pet.

App. No. 78-253, 84a et seq. On April 21, 1978 the

Fifth Circuit in a unanimous opinion by Judge Tjoflat,

joined by Judges Coleman and Fay remanded the case

for a new plan and further findings. 572 F.2d 1010.

The court found that a large number of one-race

schools remained and that there had been no findings

as to the feasibility of achieving more integration by

using the desegregation techniques approved in

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Educa

tion, 402 U.S. 1 (1971). The Fifth Circuit was partic

ularly critical of the plan’s failure to further desegre

gate the high schools, because the pupils in grades 4-

8 in some areas were integrated in those grades and

then segregated again in grades 9-12. The court or

dered evaluation of the feasibility of applying the

techniques which desegregated grades 4-8 to grades

9-12 in the same areas. 572 F.2d at 1014-1015.

As matters now stand Dallas high schools are still

operated on substantially the same basis ordered by

13

Judge Davidson in 1965, except for limited changes

made by the DISD plan in 1971. The high school plan

which the Fifth Circuit rejected in the first appeal

was not substantially improved on remand and was

accordingly rejected again on the second appeal. Gen

erally speaking, pupils in grades K-3 are also still

assigned on the basis of the “ neighborhood” zones

developed by the Board under the 1965 court order.

II. The 1971 Proceedings on the Issue of the

Constitutional Violation.

The Texas Constitution and statutes required

school segregation in Dallas both before and after

Brown v. Board o f Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954).

Texas Constitution Art. 7, §7 (1876) (repealed Aug. 5,

1969). See Bell v. Rippy, 146 F.Supp. 485, 487 (N.D.

Tex. 1956); Borders v. Rippy, 247 F.2d 268, 272, note

1 (5th Cir. 1957). See also Tasby v. Estes, 412 F.Supp.

1185,1189 (N.D. Tex. 1975). The array of Texas school

segregation laws listed below was not repealed until

1969, fifteen years after Brown, supra.4

4 Texas statutes mandating school segregation enacted in 1905,

1911, 1915, 1923 and 1957 were repealed in 1969:

1. Tex. Rev. Civ. Stat. Ann., art. 2691 (Vernon 1965) enacted

in 1905, provided for separate teachers’ meetings for white and

colored teachers. Repealed by Acts 1969, 61st Leg., p. 3024, ch.

889, § 2, effective Sept. 1, 1969.

2. Tex. Rev. Civ. Stat. Ann., art. 2695 (Vernon 1965) enacted

in 1905, provided for consolidation of small school districts by

race. Repealed by Acts 1969, 61st Leg., p. 3024, ch. 889, § 2,

effective Sept. 1, 1969.

14

Desegregation of the Dallas public schools finally

began at the first grade level in September 1961 (1971

3. Tex. Rev. Civ. Stat. Ann., art. 2719 (Vernon 1965) enacted

in 1923, provided for a free public segregated school system.

Repealed by Acts. 1969, 61st Leg., p. 3024, ch. 889, § 2, effective

Sept. 1, 1969.

4. Tex. Rev. Civ. Stat. Ann., art. 2755 (Vernon 1965) enacted

in 1905, provided that schools constructed with any funds vol

untarily given by one race for a school for that race could not be

used by another race without the consent of the district trustees.

Repealed by Acts of 1969, 61st Leg., p. 3024, ch. 889 § 2, effective

Sept. 1, 1969.

5. Tex. Rev. Civ. Stat. Ann., art. 2816 (Vernon 1965) enacted

in 1905, provided for taking the school census by “ color” of the

parent or guardian of the child. Repealed by Acts 1969, 61st

Leg., p. 3024, ch. 889, § 2, effective Sept. 1, 1969.

6. Tex. Rev. Civ. Stat. Ann., art. 2817 (Vernon 1965), enacted

in 1905, provided for the separation of school census forms by

race. Repealed by Acts 1969, 61st Leg., p. 179, ch. 75, §4, effec

tive Sept. 1, 1969; Acts 1969, 61st Leg., p. 3024, ch. 889, § 2,

effective Sept. 1, 1969.

7. Tex. Rev. Civ. Stat. Ann., art. 2819 (Vernon 1965) enacted

in 1911, provided that the county superintendent make separate

census rolls by race. Repealed by Acts 1969, 61st Leg., p. 3024,

ch. 889, § 2, effective Sept. 1, 1969.

8. Tex. Rev. Civ. Stat. Ann., art. 2893 (Vernon 1965) enacted

in 1915, provided that any child who lived more than two and

one-half miles from a public school for children of his same race

was not required to attend school. Repealed by Acts 1969, 61st

Leg., p. 3024, ch. 889, § 2, effective Sept. 1, 1969.

9. Tex. Rev. Civ. Stat. Ann., art. 2900 (Vernon 1965) enacted

in 1905, provided that no child could attend a public school

supported by public funds for another race. Repealed by Acts

1969, 61st Leg., p. 361, ch 129, § 1, effective Sept. 1, 1969; Acts

1969, 61st Leg., p. 3024, ch. 889 § 2, effective Sept. 1, 1969.

15

Tr. 436),* 5 6 when the Fifth Circuit reversed one of Judge

Davidson’s orders which endorsed a three-way system

of white, black and integrated schools. The Fifth Cir

cuit approved the DISD’s proposal for a grade-a-year

desegregation plan.® Superintendent Estes testified

that the DISD converted from a dual set of school

zones for Black and White pupils to single zones on

a grade-a-year basis until 1965 when the schedule was

accelerated to include all six elementary grades and

Grade 12. 1971 Tr. 435-436; 1971 Defendants Exhibit

4.7 The DISD eliminated the dual zones for Junior

10. Tex. Rev. Civ. Stat. Ann., art. 2900a (Vernon 1965) enacted

in 1957, provided that dual public school systems could not be

abolished except by election of the voters in the school district,

that school districts which maintained integrated schools for the

1956-57 school year be permitted to continue unless abolished,

and that school districts and persons violating these provisions

be subjected to penalty. Repealed by Acts 1969, 61st Leg., p.

1669, ch. 532, § 2, effective June 10, 1969; Acts 1969, 61st Leg,,

p. 3024, ch. 889, § 2, effective Sept. 1, 1969.

11. Tex. Rev. Civ. Stat. Ann., art. 3901a (Vernon 1965) enacted

in 1957, provided, inter alia, that no child should be compelled

to attend school with children of another race. Repealed by Acts

1969, 61st Leg., p. 3024, ch. 889, § 2, effective Sept. 1, 1969.

5 The 5 volume transcript of the 1971 hearings is cited herein

as “ 1971 Tr.’ ’. Volumes 1 and 2, pages 1-663 contain the hearing

on the violation question. Volumes 3-5, pages 664-1435 are the

1971 remedy hearing.

6 Boson v. Rippy, 285 F.2d 43 (5th Cir. 1960). The Fifth Circuit

did not approve the 12 year delay but remanded for further

proceedings on the timing. 285 F.2d at 47. See Borders v. Rippy,

195 F.Supp. 732 (N.D. Tex. 1961).

7 The acceleration of the plan was the result of two more ap

peals by plaintiffs. In September 1964 Judge Davidson denied

16

High schools in 1966 and for the final two grades (10

and 11) in September 1967. 1971 Tr. 437. The 1965

resolution gave the Superintendent complete discre

tion to “ prepare rules and regulations and establish

the boundaries of districts, in order to implement and

carry out the purpose and intent of this Resolution.”

Def. 1971 Exhibit 4. The resolution provided that

schools “ shall be racially desegregated” and that

“ single attendance districts shall be established” at

the various grade levels, and it provided for transfers

without regard to race. Ibid. The resolution and court

order contained no other details about the manner in

which desegregation was to be accomplished. Thus

the 1965 court orders did not prescribe the manner of

desegregation beyond specifying the grades to be in

plaintiffs’ motion to accelerate the 12 year plan. While plaintiffs’

appeal was pending the Fifth Circuit held in other cases that 12

year plans could no longer pass muster. Lockett v. Board of

Education of Muscogee County, 342 F.2d 225 (5th Cir. 1965)

(February 24, 1965); Bivins v. Board of Public Ed., 342 F.2d 229

(5th Cir. 1965) (February 25, 1965); Singleton v. Jackson Mun.

Sep. School Dist., 348 F.2d 729 (5th Cir. 1965) (June 22, 1965).

The day after Singleton, supra, the DISD passed a resolution to

establish single attendance zones for all elementary schools in

September 1965, for Junior High schools in 1966, and for High

Schools in 1967. See this resolution in the Tasby record as 1971-

Defendants Exhibit 1. When the Fifth Circuit was advised of the

resolution it vacated and remanded relying on the board’s good

faith. Britton v. Folsom, 348 F.2d 158 (5th Cir. 1965). It also

ordered the desegregation of grade 12, but despite that clear

direction Judge Davidson refused to order grade 12 desegregated

and plaintiffs appealed again. On September 1, 1965, the Fifth

Circuit again ruled that grade 12 must be desegregated imme

diately. Britton v. Folsom, 350 F.2d 1022 (5th Cir. 1965). See

1971 Defendants Exhibits 2, 3, and 4.

17

eluded, and there was no review of the DI SB ’s com

pliance or other proceeding in that case after 1965.

Superintendent Estes testified that attendance

areas were designated on the basis of such criteria as

building capacities, distance to schools, geographical

barriers, traffic arteries, projected enrollment and

continuity in curriculum. 1971 Tr. 590-592. He stated

that “ We have not considered race in the construction

of attendance zones in this district.” 1971 Tr. 527; see

also 589.

The earliest year for which school-by-school racial

enrollment data is available in the record is 1966-67.8

Racial segregation was very evident at that time. In

1966-67 there were 33 90-100% Black schools. Three-

fourths of all Black pupils (33,850 out of 43,816 or

77.26%) attended these 33 virtually all-Black schools

in 1966-67. There were 114 schools which had less

8 The 1966-67 figures are on the last two pages of Appendix 4

of the DISD answers to plaintiffs’ first set of interrogatories.

The answers were admitted into evidence at 1971 Tr. 6-11. The

Board answered that it did not have racial enrollment data avail

able for earlier years. Before and during the trial Judge Taylor

declined to require the Board to answer plaintiffs’ interrogatories

seeking racial enrollment data, school assignment maps and

other materials for years prior to 1965. See Transcript of hearing

on discovery matters June 8, 1971, pp. 1-15; see also 1971 Tr.

660. In so ruling Judge Taylor said “ . . . I want to know what

the situation is now, in the light of the development on the law

and what the School District is doing now, and has done since

’65. I don’t think it’s necessary to—if you want me to, I will say

that it’s pretty obvious to the Court that there must have been

de jure segregation or segregation prior to the Court order of

’65.” June 8, 1971, Tr. 15.

18

than 10% Black pupils and enrolled nine-tenths of the

Anglos and Hispanics (107,173 out of 118,079 or

90.76%). The 1966-67 enrollment data is summarized

below in a table which shows the number of schools

and pupils in each percentage range. Anglos, Hispan

ics and “ others” are combined in the Board’s figures

for 1966-67. The table indicates the racial separation

of Black pupils during 1966-67:

1966-67

Percentage of

Anglo, Hispanic

& Other Students

No. of

Schools

Anglo, Hispanic

& Other Students

No. %

Black Students

No. %

90-100 114 107,173 90.76 560 1.28

80-89 6 3,882 3.29 770 1.76

70-79 5 2,386 2.02 856 1.95

60-69 4 1,528 1.29 789 1.8

50-59 1 447 .38 442 1.01

40-49 1 278 .24 302 .69

30-39 2 547 .46 1,095 2.5

20-29 1 404 .34 1,045 2.38

10-19 4 832 .71 4,107 9.37

1-9 10 578 .49 11,241 25.66

Less than 1% 23 24 .02 22,609 51.6

Total 171 118,079 100 43,816 100

% o f Total 72.94 27.06

S ou rce : This ta b le was d eriv ed from the data in d e fen d an ts '

Answers to In te r r o g a to r ie s ( f i r s t s e t ) Appendix 4

( la s t two p a g e s ).

19

It is possible to identify the names of the all-Black

schools in Dallas in the early 1960’s despite the ab

sence of detailed enrollment data, because faculties

were segregated and the all-Black faculties are in the

record.9 The faculty figures identify 37 all-Black

schools in the pre-1965 period. There were 28 all-Black

faculties in 1960-61, three new schools were opened in

the early 196Q’s with Black faculties, and the DISD

converted six all-White faculties to all-Black in the

1962-64 period.10

9 Defendants’ Answers to Interrogatories (first set), No. 1(d).

10 Twenty-eight schools with all-Black faculties in 1960-61

were: Lincoln H.S., Madison H.S., B.T. Washington H.S., Se

quoyah Jr. H.S., Arlington Park, J.H. Brown, Carr, Carver, Co

lonial, Darrell, Douglass, Dunbar, Crispus Attucks, Eagle Ford

(Black), Ervin, Frazier, Harllee, Harris, Hassell, Johnston, Polk,

Ray, Rice, Roberts, Thompson, Tyler, Wheatley, and Starks.

Three schools opened in the period with all-Black faculties were

Ervin Jr. H.S., Pinkston H.S., Roosevelt H.S. Six schools con

verted from all-White to all-Black faculties were Holmes Jr. H.S.,

Zumwalt Jr. H.S., Pease, Stone, Miller, and Mills. Answers to

Interrogatory 1(d).

The conversions from all-White to all-Black faculties were:

Schools Years White Teachers Black '

Holmes 1963-64 26 0

1964-65 0 50

Zumwalt 1964-65 42 0

1965-66 0 33

Pease 1963-64 12 0

1964-65 0 24

Stone 1963-64 17 0

1964-65 0 17

Miller 1962-63 20 0

1963-64 0 26

Mills 1961-62 15 0

d. 1962-63 0 24

20

During the period from 1965 to the trial in 1971 the

DISD built at least 15 schools which were either all-

White or all-minority by the time of the trial, and five

others were opened as such shortly thereafter.11 Re

spondents Tasby et al. and the NAACP took four

appeals to the Fifth Circuit complaining of the district

court’s refusal to enjoin the DISD from building a

series of new one-race schools. Dr. Estes testified

“ The policy of the District has been during the pre-

SwanfnJ era not to consider race in the construction

of school facilities.” 1971 Tr. 527-28. The Fifth Circuit

twice remanded and held in 1975 that the district

court had erred in not granting plaintiffs some relief

against the continued building of new one-race

schools. Tasby v. Estes, 444 F.2d 124 (5th Cir. 1971);

Tasby v. Estes, 517 F.2d 92, 104-106, 110 (5th Cir.

1975). In 1978 the Fifth Circuit approved a site ac

quisition complained of by the NAACP, but ordered

the district to study the feasibility of sending White

pupils to the school which had been planned as anoth

er all-Black facility. Tasby v. Estes, 572 F.2d 1010,

11 All-White schools opened between 1965 and the trial were

Carter, Skyline, Hulcey, Alexander, Cochran, Conner, Gooch,

Nathan Adams, Rowe, Runyon, Turner. Minority schools were

Arlington Park, Darrell, Marshall, Edison, Seguin, Tyler, Navar

ro, Jackson and Young. PI. 1971 Exhibit 3; 1971 Tr. 494-500.

Another fourteen one-race facilities benefited from construction

additions between 1965 and 1971. Of further note is the fact that

the five new facilities opened post-1971 were the subject of ob

jection by plaintiffs prior to their completion. Despite plaintiffs’

unsuccessful attempts to enjoin this construction the DISD

opened each as a one-race facility.

2 1

1016-1018 (5th Cir. 1978). Nevertheless, since the 1978

Fifth Circuit decision, the 1979 DISD report to the

court shows that two new virtually all-Black high

schools have been opened in the disputed shopping

center, e.g., A. Maceo Smith High School 97.64%

Black and East Oak Cliff Alternative School 99.21%

Black.

The DISD did not adopt a racial majority-to-mi-

nority transfer plan until the eve of the 1971 liability

trial, and it was not announced until the trial. 1971

Tr. 560-563, 645-647. Prior to the 1971 trial pupils

were required to remain in their attendance area

schools and there was no “ freedom of transfers’ ’ pol

icy except for certain transfers for “ curriculum en

richment” . 1971 Tr. 561.

Despite the 1965 order, pupil segregation was still

extensive in 1970-71 the year this suit was filed. In

that year there were about 181 schools enrolling

165,694 pupils who were 94,354 Anglos (56.94%),

56,621 Blacks (34.17%), 13,948 Mexican Americans

(8.42%) and 771 Asians, American Indians and others

(.47%). A full nine-tenths of the Black students at

tended 48 schools which were less than 10% White;

sixty-three percent of them were in 36 schools which

had less than 1 percent Anglo pupils. More than two-

thirds of the Anglos were concentrated in 69 over 90%

Anglo schools. The following table gives a detailed

analysis of the 1970-71 enrollments and depicts the

great extent of segregation:

1970 - 71

Percentage

Of White

Students

No. of

Schools

White Students

No. %

Black

No.

Students

%

Hispanic Students

No. %

Other Students

No. %

90-100 69 64,995 68.88 242 .43 1,991 14.27 253 32.81

80-89 21 16,466 17.45 516 .91 2,051 14.7 179 23.22

70-79 15 6,555 6.95 442 .78 1,439 10.32 93 12.06

60-69 8 2,252 2.39 218 .39 976 7.0 82 10.64

50-59 1 215 .23 107 .19 40 .29 2 . 26

40-49 7 1,609 1.7 529 .93 1,365 9.79 58 7.52

30-39 1 79 .08 9 .01 144 1.03 6 .78

20-29 5 983 1.04 1,181 2.09 1,657 11.88 25 3.24

10-19 6 650 .69 2,416 4.27 1,552 11.13 28 3.63

1-9 12 439 .47 14,859 26.24 1,696 12.16 34 4.41

Less than 1% 36 111 .12 36,102 63.76 1,037 7.43 11 1.43

TOTAL. 181 94,354 100 56,621 100 13,948 100 771 100

% Of Total 56.94 34.17 8.42 .47

Source: This table was derived from the data in Defendants ' Answers

to Interrogatories (First Set) Appendix 1. (See also

Plaintiffs' 1971 Exhibits 1, 2.)

23

The net effect of the board’s policies between 1965

and 1970 was to increase the extent of segregation of

Black pupils during the years when desegregation was

supposedly being implemented. The 1972 Mondale

Committee Report found that the percentage of Dal

las Blacks in 90-100% Black schools was 82.6% in

1965, 87.6% in 1968 and 91.4% in 1971.12

In 1970-71 the DISD had 7,293 teachers: 1,856 were

Black, 73 were Chicano and 5,364 were Anglo. Plain

tiffs’ 1971 Exhibit 4. Plaintiffs established at the 1971

trial that there had been relatively little progress in

faculty desegregation in the DISD. Plaintiffs’ 1971

Exhibit 4 listed the many one-race schools with vir

tually one-race faculties. This exhibit established that

of 1,865 Black teachers in the DISD, 1,694 or 88.8%

taught in schools with 90% or greater racial minority

students, and only 88 Black teachers or 4.7% were in

schools with 90% or greater white enrollments.13 Su

12 Report of the Select Committee on Equal Educational Op

portunity, 92nd Cong., 2d Sess. Senate Report No. 92-100; De

cember 31, 1972, Table 7-16, p. 117. The 1968 and 1971 figures

in the Senate Report are consistent with exhibits in the record.

(See Defendants’ Answers to Interrogatories (first set) Append

ices 1 and 3). The record does not contain racial enrollment data

by school for 1965. (See note 8, supra).

13 We have now subjected the student and faculty enrollment

figures in the Defendants’ Answers to Interrogatories, first set,

to a more detailed analysis and calculated the correlation be

tween the percentages of black students and teachers in each

school in the system in 1970-71. The calculations yield a coeffi

cient of correlation (r) of .91, and a coefficient of determination

(r ) of .83. The coefficient of determination indicates that the

racial composition of the students accounts for or is associated

24

perintendent Estes testified that in 1968-69 the DISD

began a phased faculty desegregation program, by

assigning more than one ethnic group to the faculties

of 20 of the 182 schools. 1971 Tr. 455. In 1969-70 the

system had “ over forty” faculties “ with more that

one ethnic group represented” . Id. at 455. In 1970-71

Dr. Estes said “ we had all of our twenty-one high

schools, twenty-three junior highs, and over sixty per

cent of our elementary schools that had more than

one ethnic group represented on their faculty.” Id. at

455-456. After the start of the 1971 trial the DISD

announced for the first time its plan to desegregate

the faculties of all schools in accordance with the Fifth

Circuit’s Singleton decision. 1971 Tr. 456, 647-652.

See Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Separate School

District, 419 F.2d 1211 (5th Cir. 1969). Dr. Estes also

indicated an awareness of this Court’s Montgomery

decision on faculty desegregation (1971 Tr. 650)

(United States v. Montgomery County Board o f Ed.,

395 U.S. 225 (1969)), but said that the Board had not

decided to adopt a Singleton plan until after the

Swann decision. 1971 Tr. 651. Of course, this Court’s

first faculty desegregation decisions had been made

six years earlier. Bradley v. School Board, 382 U.S.

103 (1965); Rogers v. Paul, 382 U.S. 198 (1965).

Dr. Estes testified that 19 schools had changed

from White to predominantly Black between 1965 and

with about 83% of the variation in faculty racial compositions.

See J. Freund, Modern Elementary Statistics 421-22 {4th ed.

1973).

25

the 1971 trial, and that these changes were due to

changing neighborhood racial patterns, primarily in

the South Oak Cliff area of Dallas during these years.

1971 Tr. 514-422. Dr. Estes said that 1 High School,

3 Junior High schools and 15 elementary schools

changed from White to Black during the 1965-1971

period.14 The district court stated in its opinion on the

violation issue that “ ft]he School Board has asserted

that some of the all Black schools have come about

as a result of changes in the neighborhood patterns

but this fails to account for the many others that

remain as segregated schools.” Tasby v. Estes, 342

F.Supp. 945, 947 (N.D. Tex. 1971).

The validity of the court’s finding is easily dem

onstrated by observing that 31 schools which had all-

Black faculties in the early 1960’s had 90% or more

Black pupils at the time of the 1971 trial.15 Indeed in

1979, 30 of the pre-1965 all-Black schools remain over

14 The schools named by Dr. Estes were South Oak Cliff High,

Holmes Jr. High, Boude Storey Jr. High, Zumwalt Jr. High, and

Pease, Bushman, Stone, Bryan, Lisbon, Thornton, Budd, Russell,

Oliver, Marsalis, Earhart, Juarez, Lanier, City Park, and Roberts

elementary schools. (At one point Dr. Estes said there were 16

such schools but only 15 elementary schools were named). 1971

Tr. 514-522.

15 Of the 37 pre-1965 all-Black schools which we have been able

to identify by their faculties in note 10 supra, 31 of them had

over 90% Black pupils in 1970-71, 3 were between 82 and 98%

Black and Mexican-American combined, and 3 were no longer

open. Compare Answers to Interrogatories (first set), Answer to

Int. 1(d) with Appendix 1 of the same answers.

26

90% Black.16 Similarly, if one compares the list of all-

Black schools in 1966-67 with the current list of all-

Black schools in the Board’s April 1979 report to the

district court, it is evident that most of the 1966

Black schools have not been desegregated. Twenty-

eight schools which were virtually all-Black in 1966-

67 are still all-Black in 1979; the 28 schools listed in

the note below were 90 to 100% Black in both 1966

and 1979.17 There were five other all-Black schools in

16 Compare list of schools in note 10, supra from Board’s An

swer to Interrogatory 1(d) with April 15, 1979 report by DISD

to the District Court. Of the 36 schools listed in note 10, supra

all are 90% or more Black in 1979 with the following exceptions:

Polk—83.05% Black, Sequoyah—47.65% Black, B.T. Washing

ton (now Arts Magnet school)—47.65% Black. The remaining

exceptions are schools which have been closed since 1965, e.g.,

Attucks, Eagle Ford (Black) and Starks. Zumwalt Jr. H. building

was designated under the Court-ordered plan to be used as part

of the all-Black S. Oak Cliff H.S. The B.T. Washington H.S. was

closed from 1969 until reopened in 1976 as the Arts Magnet high

school.

17 Schools under 10% White in 1966 and 1979:

Less than 1% White in 1966-67

Lincoln H.S., F.D. Roosevelt H.S., James Madison, H.S., J.N.

Ervin Middle School, Arlington Park Comm. Lrn. Center, John

Henry Brown Elem. Sch., Colonial Elem. Sch., B.F. Darrell

Comm. Lm. Center, Paul L. Dunbar Elem. Sch., J.N. Ervin Elem.

Sch., Julia C. Frazier Elem. Sch., Fannie C. Harris Elem. Sch.,

Thomas C. Hassell Elem. Sch., J.W. Ray Elem. Sch., Chas. Rice

Elem. Sch., H.S. Thompson Elem. Sch., Priscilla L. Tyler Comm.

Lrn. Center, Phyllis Wheatley Elem. Sch.

1-9% White in 1966-67

O.W. Holmes Middle Sch., J.N. Bryan Elem. Sch., C.F. Carr

Elem. Sch., G.W. Carver Elem. Sch., N.W. Harllee Elem. Sch.,

Albert S. Johnston Elem. Sch., Roger Q. Mills Elem. Sch., Alisha

27

1966-67.18 Seven of the all-White schools of 1966 re

main over 90% White, and another eight are 80-100%

White in 1979.19

The Curry intervenors, who were allowed to inter

vene as defendants after the trial on the violation,

argued that the desegregation remedy should not ap

ply to their area of North Dallas because it had not

been a part of the DISD at the time of the Brown

decision. However, each of the schools in the area

claimed by the Curry group was established as a one-

race White school during the years of dual school

M. Pease Elem. Sch., Harry Stone Middle Sch., Sarah Zumwalt

Jr. H.S. (now part of S. Oak Cliff H.S.)

18 Schools under 10% White 1966-67 but not in 1979

P.C. Anderson Career Academy, K.B. Polk Elem. School, Booker

T. Washington Elem. Sch. now Arts Magnet school), Winnetka

Elem. Sch., Joseph J. Rhoads Elem. Sch.

19 Schools over 90% White in both 1966-67 & 1979

W.T. White H.S., Wm. L. Cabell Elem. Sch., Tom C. Gooch Elem.

Sch., Victor H. Hexter Elem. Sch., Arthur Kramer Elem. Sch.,

Richard Lagow Elem. Sch., Nancy Moseley Elem. Sch.

Schools over 90% White in 1966 & 80-90% White in 1979

Bryan Adams H.S., George B. Dealey Elem. Sch., Everette Lee

Degolyer Elem. Sch., Chas. A. Gill Elem. Sch., Edwin J. Kiest

Elem. Sch., B.H. Macon Elem. Sch., Urban Pk. Elem. Sch., Harry

C. Withers Elem. Sch.

Note should be made that for elementary and middle schools,

the overall school percentage for Anglo is the utilized measure

ment. In grades K-3 as of 1979, many more elementary schools

will be 80% to over 90% Anglo.

2 8

operation. The schools all opened with all-White fa

culties:

School Year Opened Facu lty (yea r )

N. Adams 1967 26 White - 1967

C ab e ll 1958 26 White,, 1 H isp. - 1960-61

D egolyer 1961 28 W hite - 1961

Gooch 1965 24 W hite - 1965

Marcus 1963 13 White - 1963

W ithers 1961 28 W hite - 1961

Marsh J r . H,S 1962 37 White - 1962

W.T. W hite H.iD. 1964 38 W hite - 1964

Answers to interrogatories (first set) 1(d).

Each of these schools had over 90% White pupils

in the 1966-67 year, with the exception of Nathan

Adams which opened the following year as an over

90% White school. Answers to Interrogatories (first

set), Appendix 4 (last two pages). Gooch, Cabell and

W.T. White H.S. remain over 90% White, and Dego-

lyer and Withers are 80-89% White in 1979.

The district court’s opinion of July 16, 1971 found

that “ elements of a dual system still remain” , and

that the DISD had been aware of, but had not com

plied with, Fifth Circuit decisions ordering various

desegregation steps until after the case was filed.20

20 The court wrote at 342 F.Supp. 945, 947-948:

When it appears as it clearly does for the evidence in this case

that in the Dallas Independent School District 70 schools are

29

The court found that there was insufficient evidence

to show there had been de jure segregation of Mexi-

can-Americans in Dallas, but did find that Mexican-

Americans were a distinct and clearly identifiable eth

nic group, and ordered that any desegregation plan

must take this fact into consideration.21

90% or more white (Anglo), 40 schools are 90% or more Black,

and 49 schools are 90% or more minority, 91% of black students

in 90% or more of the minority schools, 3% of the black students

attend schools in which the majority is white or Anglo, it would

be less than honest for me to say or to hold that all vestiges of

a dual system have been eliminated in the Dallas Independent

School District, and I find and hold that elements of a dual

system still remain.

The School Board has asserted that some of the all-Black

schools have come about as a result of changes in the neighbor

hood patterns but this fails to account for many others that

remain as segregated schools. The defendant School Board has

also defended on the ground that it is following a 1965 Court

order. This position is untenable.

The Green and Alexander cases have been handed down by

the Supreme Court since the 1965 order of the Court of Appeals

for the Fifth Circuit to the Dallas Independent School District.

There have been too many changes in the law even in the Fifth

Circuit and it is fairly obvious to me that the defendant School

Board and its administration have been as aware of them as I.

For example, the case of Singleton v. Jackson Municipal Sepa

rate School District, 419 F.2d 1211 was handed down in Decem

ber of 1969. This was the case in which the Court ordered, among

other things, desegregation of faculty and other staff, majority

to minority transfer policy, transportation, an order with refer

ence to school construction and site selection, the appointment

of bi-racial committees. The Dallas School Board has failed to

implement any of these tools or to even suggest that it would

consider such plans until long after the filing of this suit and in

part after the commencement of this trial.

21 The finding that Mexican-Americans were an identifiable

minority group was made on the basis of considerable evidence

30

III. The 1971 Remedy Hearing; Desegrega

tion Proposals.

A. Plaintiffs’ Proposal—the TEDTAC Plan.

At the 1971 hearing plaintiffs endorsed a desegre

gation plan which would have effectively desegregat

ed the entire DISD. The plan, called the TEDTAC

plan (1971 Pi’s. Exhibits 122, 123, 124, and 125), was

the product of several months work by a team of 8

staff members of the Texas Educational Desegrega

tion Technical Assistance Center, University of Texas

at Austin. TEDTAC had previously worked on deseg

regation plans for 41 other school districts. 1971 Tr.

1016. TEDTAC began working on a Dallas plan fol

lowing a request from Judge Taylor in October 1970.

1971 Tr. 966. The Project Administrator, Pete Wil

liams, met with the Superintendent and all principals,

and then teams of staff members visited every school

in the district and collected data. 1971 Tr.967-970;

1029-1040. This was followed by a three month period

of drawing and redrawing attendance lines to produce

the final product. 1971 Tr. 969. Joe Price, the team

captain, explained the plan in detail. 1971 Tr.986-

1006; 1114-1117; 1150-1168.

The TEDTAC plan would have desegregated each

high school in the city by redrawing attendance lines.

The high school plan is 1971 Pl.Ex. 123; the proposed

offered by plaintiffs. See 1971 Tr. pp. 102-378; testimony of

Richard Medrano, Dr. George I. Sanchez, Rene Martinez, Carlos

Vela, Horacio Ulibarri, and Henry Ramirez.

31

new zone map follows page 20. The plan used elon

gated zones to assign minority pupils in the central

and southern parts of the district and White pupils in

the northern area to the same schools. The plan pro

posed White enrollments in the high schools which

ranged from a high of 84% to a low of 40%. The

highest projected Black percentage in any high school

would have been 41%. (The district-wide ratios in

1970-71 were Anglo 56.94%, Black 34.17% and Mex-

ican-American 8.42%.)

The Junior High proposal (PL 1971 Ex. 124) by

TEDTAC was also a rezoning plan, based upon com

binations of new proposed elementary zones. Each of

the junior high schools would have been desegregated

with the Anglo pupils ranging from a high of 81 to a

low of 31%. Ibid. Black student percentages ranged

from 15% to 48%. The proposed zone map is at PI.

1971 Ex. 124 following p.20.

The elementary school plan (PI. 1971 Ex.125) de

segregated as many schools as possible by pairing or

grouping contiguous school zones, and grouped the

remaining schools on a non-contiguous basis. 1971 Tr.

999-1003. It was the view of the TEDTAC team that

non-contiguous pairing was essential if all racially

identifiable schools were to be desegregated. 1971

Tr.1184. White student percentages would range from

87% to 22%, and Black percentages from zero to 50%.

PL 1971 Ex. 125.

TEDTAC estimated the transportation required by

the elementary plan as 12,500 students in contiguous

32

zones and 21,600 in non-contiguous zones. 1971

Tr.1115. TEDTAC Administrator Pete Williams be

lieve that it was not necessary to plan a bus trans

portation program for high school pupils, because few

would actually use school buses. 1971 Tr. 983-985. He

said that secondary students usually provide their

own transportation and tend to think of school buses

as something for younger children. Ibid. The DISD

estimated that the TEDTAC plan would make 35,000

secondary pupils and a total of 70,000 pupils eligible

for busing. 1971 Tr. 1313-1314; 1324-1327.

The TEDTAC staff used scaled maps to estimate

the distances pupils would be required to travel under

the plan. 1971 Tr. 1155-1160. Mr. Price testified to

the longest distances in each non-contiguous group or

pair; the contiguous pairs were all shorter distances.

He estimated the distances in the non-contiguous

pairs ranged from 7 to 18 miles. 1971 Tr. 1157-1160.

Plaintiffs also presented illustrative travel time stud

ies. Twilla Young drove from Arlington Park Elemen

tary to White High School in both directions meas

uring 14.8 miles and 26 minutes in one direction and

15 miles in 24 minutes in the other direction. 1971 Tr.

1287-1293. She drove from Burnett Elementary to

Darrell Elementary 23.9 miles and 35 minutes one

way and 22.1 miles and 32 minutes in the other direc

tion.

When the TEDTAC plan was finally presented in

court it was not advocated by TEDTAC, but was

merely presented as a feasible proposal. 1971 Tr.988.

33

Instead TEDTAC administrator Williams advocated

his invention the television plan which, as modified,

was urged by the DISD and eventually ordered by

the court. However Mr. Williams did testify that the

TEDTAC plan advocated by plaintiffs was “ educa

tionally sound, administratively feasible, and finan

cially plausible.” 22 1971 Tr. 1185. Mr. Williams testi

fied that in his opinion bus trips not in excess of 45

minutes one-way were acceptable, but that longer

trips might interfere with the school day. 1971

Tr.1186-1187. One of his reasons for finally not ad

vocating the plan was a fear that some of the trips

might be longer than 45 minutes. 1971 Tr. 1233.23

Mr. Bryan Vinson, operator of a private bus com

pany which transports private school children in Dal

las, testified that he transports pupils from 10 min

utes to an hour, and that the average ride of these

private school children in Dallas was 45 minutes. 1971

Tr.1301-1303. Superintendent Estes testified that

based on his experience working at H.E.W. he knew

22 Judge Taylor noted the abuse and criticism TEDTAC re

ceived for creating the proposal: ‘ ‘That agency has been harassed,

intimidated, pressured and abused in many other ways, and it

did not deserve this type of treatment. The politicians have made

their speeches, have called their office demanding names, sug

gesting loss of employment sometimes subtly and sometimes not

so subtly. Some of the staff of TEDTAC have been obliged to

unlist their phone numbers in order to escape harassing telephone

calls.” 342 F.Supp. at 949.

23 Mr. Williams also said he did not recommend the TEDTAC

plan because he thought the community would react badly to the

idea of buying a lot of buses. 1971 Tr. 1232-1233.

34

that about 39% of all pupils in the country were bused

to school. 1971 Tr. 951-952. The DISD’s own 1971

proposal for secondary schools included a few bus

trips of an estimated 30 minutes. 1971 Tr. 852.

In the Memorandum Opinion of August 17, 1971

(342 F.Supp. 949), Judge Taylor declined to order the

TEDTAC plan stating:

The Court has concluded that to adopt the ger

rymandering, pairing, and grouping plan submit

ted by Plaintiffs, accompanied by the massive

crosstown bussing required to implement such a

plan, would result in extensive “ abrasions and

dislocations” and a disruption of the educational

process, and is rejected in the light of the teach

ing of Allen v. Board of Public Instruction of

Broward County, 432 F2d 362 (5th Cir. 1970), to

keep “ such problems at a minimum” .

342 F. Supp. at 950-95).

B. The DISD Plan and the Court-Ordered

Plan.

The desegregation plan filed by the DISD July 23,

1971, (Def.1971 Ex.20) entitled “ Confluence of Cul

tures” provided a student assignment plan for senior

and junior high schools based upon rezoning with the

use of a few satellite zones in Black neighborhoods

from which pupils were bused to formerly White

schools.24 Supt. Estes explained the high school plan.

24 In addition to the assignment plan the proposal provided for

desegregation of faculty and staff, for a majority to minority

35

1971 Tr. 680-705. He testified the plan would elimi

nate every 90% or more White high school and all but

one 90% or more Black high school. Id. at 680. The

plan created three satellite zones in which Black pup

ils would be bused to White high schools, e.g., from

the Ray school area to Hillcrest High (about 20-30

minutes) (Id. at 694), from Arlington Park area to

White High school (350 students about 30 minutes)

(Id. at 695) and from the Harris and Hassell areas to

Bryan Adams. Id. at 698.

Dr. Estes explained that in drawing high school

attendance zones the DISD had attempted to mini

mize the changes in zone lines:

Q. The student assignment in the high schools

for ’71-72 under the School Board’s plan. Now,

you said yesterday in drawing this plan you, the

Board had attempted to maintain the continuity

and integrity of the high school zones. Now, what

does that mean?

A. That’s correct.

Q. What does that mean exactly?

A. This means to maintain as nearly as possible

the feeding schools associated with that partic

ular high school so that the traditions, the cus

toms, the localities that have been established,

the articulation and coordination of the curricu

lum that has been developed over a period of

transfer option, for a recognition by the district of an affirmative

duty to use school location and abandonment to promote inte

gration, and for a tri-ethnic committee. Def. 1971 Ex.20.

36

years, the communication between department

heads, between classroom teachers and among

the principals can be maintained so as to enhance

the possibility of continued quality education.

Q. So for these reasons you have attempted to

minimize the changes in the zone lines at the high

school level?

A. Yes sir, that’s correct.

1971 Tr. 842; Dr. Estes cross-examination by Mr.

Surratt.

The effect of the rezoning with the limited objective

of reducing one-race schools to a point just slightly

under the 90% level was indicated by the projections

in the DISD plan of ethnic composition for the 1971-

72 year. For example Black schools such as Lincoln,

Pinkston, and Roosevelt were projected at 88%,

88.2%, and 86.4% minority pupils respectively in the

plan, and Anglo schools had similar minimal integra

tion.25

The DISD plan’s treatment of the junior high

schools was similar to the high school plan. A few

Black pupils were bused from satellite zones to White

schools with the objective of reducing the number of

90% or more White schools from 10 to 1. The plan left

four 90% or more minority schools (Edison, Holmes,

Sequoyah, and Zumwalt) and another at a slightly

25 For example, the DISD projections for Anglo percentages

included Adams, Hillcrest, Jefferson, Kimball, Samuell, White

and Wilson between 80 and 88% Anglo. Def. 1971 Ex.20.

37

lower level (Storey—85,2% minority). It had eleven

White schools ranging from 79.4%—93.6% Anglo.

1971 Def. Ex. 20.

The secondary school plan finally ordered by the

district court was basically the same as the DISD

proposal just described. 517 F.2d at 100. Initially

Judge Taylor rejected the plan and ordered more bus

ing of Blacks from satellite zones and a high school

pairing arrangement. Unreported Order of August 2,

1971. However a week later, after the pairing order

had touched off public criticism, the district court

“ stayed” and ultimately abandoned this plan, stating

that it was unfair and unreasonable. 342 F.Supp. at

951; see 517 F.2d at 100. The district court then ob

tained a secondary plan from the DISD that was vir

tually identical with the original plan and approved it

in an ex parte proceeding. 517 F.2d at 100.

The DISD ’s television desegregation plan for ele

mentary schools did not change the pupil assign

ments. The DISD's own statistical summary of its

plan indicated that it would not eliminate any racially

identifiable elementary schools. Indeed the number

would be increased by the opening of 4 new Black

schools:

38

ELEMENTARY SCHOOL

STATISTICAL SUMMARY

RACIALLY IDENTIFIABLE SCHOOLS

1970-71 1971-72

Popu lated by student bod ies

90% o r g r e a te r W hite 50 50

Popu lated by student bod ies

90% o r g r e a te r B lack 32 36*

Popu lated by student bod ies

90% o r g r e a te r m in o rity 37 41*

’♦A d d it io n a l e lem entary sch oo ls f o r 1971-72

P e a r l C. Anderson

James Madison

Jose Navarro

Erasmo Seguin

D e f . 1971 E x . 20.

The district court ordered implementation of the

television plan on a basis somewhat different from

that proposed by the DISD. 342 F.Supp. at 952. The

court provided for two-way audio and visual contact

between the Anglo and minority classrooms, and also

ordered that classes be paired for television purposes

on a 2-1 Anglo-minority ratio. The board’s proposal

would have had only one-way video communication,

and would have left 10 Black schools in Oak Cliff

without even a television pairing with Anglo schools.

DISD 1971 Ex. 20; 1971 Tr. 890. Dr. Estes testified

that the DISD was prepared to spend 10 million dol

lars to implement the television plan. 1971 Tr. 729.

As previously Indicated, in 1975 the Fifth Circuit

reversed both the elementary and secondary plans

ordered in 1971 and remanded the case for a new

hearing. 517 F.2d 92. The court of appeals stayed the

39

television plan pending appeal. Thus elementary

school pupils in Dallas remained assigned to “ neigh

borhood schools” under DISD zones adopted before

the case until a new plan was implemented in Septem

ber 1976 after the second remedy hearing which is

described below. Actual desegregation under the 1971

order was limited to the secondary level.