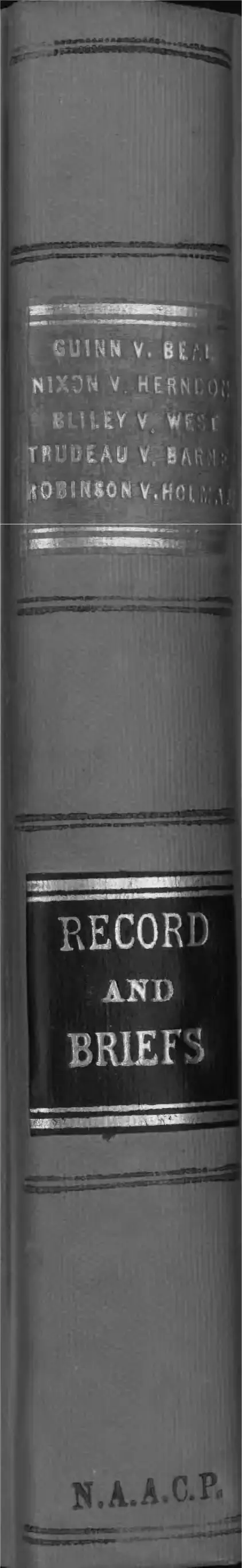

Guinn v. United States and Other Voting Rights Cases Record and Briefs

Public Court Documents

January 13, 1913 - April 3, 1930

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Guinn v. United States and Other Voting Rights Cases Record and Briefs, 1913. d9364047-ca9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c157431a-fa0b-41f9-bec9-94425e17a92b/guinn-v-united-states-and-other-voting-rights-cases-record-and-briefs. Accessed February 13, 2026.

Copied!

tfUINN V. 6 i, ■

NIXON V. HERN

; BIS LEV V Wf

T RUDE AO V, BAR

rf'OUKION V. HO i.;

RECORD

AND

BRIEFS

m

i

n? n: a: a. o; p.

, . Q ,, 70 FIFTH AVE„

NEW YORK CITY

3ltt tlje Supreme Court of tlyo Uutteu States

OCTOBER TERM, 1913 ■ /

[No. 423]

FRANK GUINN AND J. J. BEAL

v.

THE UNITED STATES.

BRIEF FOR THE NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE

ADVANCEMENT OF COLORED PEOPLE.

MOORFIELD STOREY,

Counsel.

V

\

IN D E X .

P a g e

S t a t e m e n t o f C a s e .............................................................................. 1

A r g u m e n t

All discriminations respecting the right to vote on

account of color unconstitutional............................... 3

Whether the Oklahoma amendment constitutes such a

discrimination to be determined by its purpose and

effect, and not by its phraseology alone................... 6

The undoubted purpose and effect of the amendment

to discriminate against colored voters........................... 12

TABLE OF CASES CITED.

P age

Anderson v. Myers, 182 Fed. Rep. 223 ............................... 15

Bailey v. Alabama, 219 U. S. 2 1 9 ....................................... 6

Brimmer v. Rebman, 138 U. S. 7 8 ....................................... 11

Collins v. New Hampshire, 171 U. S. 3 0 ............................... 8

Chy Lung v. Freeman, 92 U. S. 275 ...................................• 11

Galveston, Harrisburg & San Antonio Railway v. Texas,

210 U. S. 2 1 7 .................................................................. 7

Giles v. Harris, 189 U. S. 475 ............................................... 13

Giles v. Teasley, 193 U. S. 146 ............................................... 13

Graver v. Faurot, 162 U. S. 435 ........................................... 13

Hannibal & St. Joseph Railroad v. Husen, 95 U. S. 465 . . 11

Henderson v. Mayor of New York, 92 U. S. 259 ............... 10

Lochner v. New York, 198 LT. S. 4 5 ....................................... 7

Maynard v. Hecht, 151 LT. S. 324 ....................................... 13

Minnesota v. Barber, 136 U. S. 313....................................... 11

Mobile v. Watson, 116 U. S. 289 ........................................... 8

New Hampshire v. Louisiana, 108 U. S. 7 6 ....................... 8

People v. Albertson, 55 N. Y. 5 0 ........................................... 10

People v. Compagnie Generate Transatlantique, 107 U. S.

5 9 ..................................................................................... 15

Postal Telegraph-Cable Co. v. Taylor, 192 U. S. 64 . . . . 8

Schollenberger v. Pennsylvania, 171 U. S. 1 ....................... 11

Scott v. Donald, 165 U. S. 5 8 ............................................... 11

Smith v. St. Louis & Southwestern Railway, 181 U. S.

248 11

State v. Jones, 66 Ohio St. 453 ............................................... 10

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U. S. 303 ........................... 6

Voight v. Wright, 141 U. S. 62 ............................................... 11

Williams v. Mississippi, 170 U. S. 213................................... 13

Yarbrough, Ex parte, 110 U. S. 651...................................... 13

3ln the Supreme Olmtrt nf the Mtttirh States

OCTOBER TERM, 1913-

[No. 423]

FRANK GUINN AND J. J. BEAL

v.

THE UNITED STATES.

BRIEF FOR THE NATIONAL ASSOCIATION FOR THE

ADVANCEMENT OF COLORED PEOPLE.

STA TE M E N T OF FACTS.

This case comes before this court upon a certificate from

the Circuit Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit asking

instructions upon two questions relating to the validity of an

amendment to the constitution of Oklahoma adopted in

1910 and reading as follows:—

“ No person shall be registered as an elector of this State,

or be allowed to vote in any election herein, unless he be

able to read and write any section of the constitution of the

State of Oklahoma. And no person who was on January

1, 1866, or at any time prior thereto, entitled to vote under

any form of government, or who at that time resided in some

foreign nation, and no lineal descendant of such person

shall be denied the right to register and vote because of his

inability to so read and write sections of such constitution.

2

Precinct election inspectors having in charge the registra

tion of electors shall enforce the provisions of this section

at the time of registration, provided registration be required.

Should registration be dispensed with, the provisions of this

section shall be enforced by the precinct election officer when

electors apply for ballots to vote.”

Previous to this amendment, the qualifications of elec

tors had been defined in that constitution thus (Art. I l l ,

§ 1 ) : -

‘ ‘ The qualified electors of the State shall be male citizens

of the United States, male citizens of the State, and male

persons of Indian descent native of the United States, who

are over the age of twenty-one years, wUo have resided in

the state one year, in the county six months, and in the elec

tion precinct thirty days next preceding the election at which

any such elector offers to vote.”

The questions certified are as follows:—

“ 1. Was the amendment to the constitution of Okla

homa, heretofore set forth, valid?

“ 2. Was that amendment void in so far as it attempted

to debar from the right or privilege of voting for a quali

fied candidate for a Member of Congress in Oklahoma, un

less they were able to read and write any section of the con

stitution of Oklahoma, negro citizens of the United States

who were otherwise qualified to vote for a qualified candi

date for a Member of Congress in that State, but who were

not, and none of whose lineal ancestors was, entitled to vote

under any form of government on January 1, 1866, or at

any time prior thereto, because they were then slaves? ”

The vital importance of these questions to every citizen

of the United States, whether white or colored, seems

amply to warrant the submission of this brief.

3

ARG U M EN T.

The amendment to the constitution of Oklahoma now

before the court is one of many similar provisions adopted

in certain states, varying in their language but intended to

accomplish the same object, and that an object forbidden

by the constitution of the United States.

The provisions of that constitution are clear:—

“ No state shall make or enforce any law which shall

abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United

States; nor shall any state deprive any person of life, liberty

or property without due process of law, nor deny to any per

son within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws”

(Fourteenth Amendment, § 1).

“ The right of citizens of the United States to vote shall

not be denied or abridged by the United States, or by any

state, on account of race, color or previous condition of

servitude” (Fifteenth Amendment, § 1).

An amendment to a state constitution is a law within the

language of the Fourteenth Amendment, and it certainly is

action by the state.

While in terms no reference is made in the Oklahoma

amendment to race or color, that amendment abridges and

is intended to abridge the right of colored citizens of the

United States to vote, and it imposes upon them a con

dition not imposed upon any other citizens of the state,

thus denying them the equal protection of its laws. By

its terms practically every man who is not colored may vote

without the ability to read and write the constitution of

Oklahoma. A great stretch of the imagination is needed

in order to conceive of a white voter who does not come

within the classes excepted from this requirement, while

4

with very insignificant exceptions, such as possible descend

ants of free colored men residing in the free states on Janu-

uary 1, 1866, every colored voter is excluded.

The language employed is just as effective as if it dis

tinctly enforced a peculiar disqualification on all descend

ants of negro slaves. The purpose and effect of such

amendments as this have been openly avowed, and there

is not an intelligent man in the United States who is igno

rant of them. If it is possible for an ingenious scrivener

to accomplish that purpose by careful phrasing, the pro

visions of the Constitution which establish and protect the

rights of some ten million colored citizens of the United

States are not worth the paper on which they are written,

and all constitutional safeguards are weakened.

The principles governing this case are well settled. It

would hardly be contended that the Fifteenth Amendment

was not violated if the constitution of Oklahoma had been

amended so as to read as follows:—

“ No person shall be registered as an elector of this State,

or be allowed to vote in any election herein, unless he be

able to read and write any section of the constitution of

the State of Oklahoma. And no white person shall be

denied the right to register and vote because of his inability

to so read and write sections of such constitution.”

The fact that the discrimination against colored men took

the shape of exempting white voters from the restriction,

which the first sentence purported to impose upon all

citizens alike, would be immaterial.

While the Fifteenth Amendment may not necessarily

confer an affirmative right to vote, it does require in the

plainest terms that, if the right is granted at all, it must be

extended on the same terms to white and colored citizens

alike. The well-known language of Mr. Justice Bradley

5

with reference to the analogous provisions of the Four

teenth Amendment is equally pertinent here:—

“ It [the Fourteenth Amendment! ordains that no State

shall deprive any person of life, liberty or property, without

due process of law, or deny to any person within its juris

diction the equal protection of the laws. What is this but

declaring that the law in the States shall be the same for the

black as for the white; that all persons, whether colored

or white, shall stand equal before the laws of the States, and,

in regard to the colored race, for whose protection the amend

ment was primarily designed, that no discrimination shall

be made against them by law because of their color? The

words of the amendment, it is true, are prohibitory, but they

contain a necessary implication of a positive immunity, or

right, most valuable to the colored race,—the right to exemp

tion from unfriendly legislation against them distinctively

as colored,—exemption from legal discriminations, im

plying inferiority in civil society, lessening the security of

their enjoyment of the rights which others enjoy, and dis

criminations which are steps towards reducing them to the

condition of a subject race.

“ That the West Virginia statute respecting juries—the

statute that controlled the selection of the grand and petit

jury in the case of the plaintiff in error—is such a discrimina

tion ought not to be doubted. Nor would it be if the persons

excluded by it were white men. If in those States where

the colored people constitute a majority of the entire popu

lation a law should be enacted excluding all white men from

jury service, thus denying to them the privilege of parti

cipating equally with the blacks in the administration of

justice, we apprehend no one would be heard to claim that

it would not be a denial to white men of the equal protection

of the laws. Nor if a law should be passed excluding all

naturalized Celtic Irishmen, would there be any doubt of

its inconsistency with the spirit of the amendment. The

very fact that colored people are singled out and expressly

denied by a statute all right to participate in the adminis

6

tration of the law, as jurors, because of their color, though

they are citizens and may be in other respects fully qualified,

is practically a brand upon them, affixed by the law, an as

sertion of their inferiority, and a stimulant to that race

prejudice which is an impediment to securing to indi

viduals of the race that equal justice which the law aims to

secure to all others.”

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U. S. 303, 307.

The statute considered in that case did not expressly

declare that colored men should not serve as jurors, but

simply provided that “ all white male persons” should be

liable to serve as jurors, omitting all mention of negroes.

It was condemned none the less.

It is likewise plain that the mere form of words is of no

consequence, and that, if the effect of the provision in ques

tion is substantially the same as if it read as just suggested,

the fact that the use of the words “ white” and “ colored”

is carefully avoided is of no consequence. This rule has

been repeatedly applied by this and other courts when hold

ing invalid statutes artfully designed to accomplish purposes

forbidden by the Constitution while evading the letter of its

prohibitions.

In Bailey v. Alabama, 219 U. S. 219, it was held that

§ 4730 of the Code of Alabama as amended by certain stat

utes was repugnant to the Thirteenth Amendment, because,

as the court said (at p. 238):—

“ We cannot escape the conclusion that, although the

statute in terms is to punish fraud, still its natural and in

evitable effect is to expose to conviction for crime those who

simply fail or refuse to perform contracts for personal ser

vice in liquidation of a debt, and judging its purpose by its

effect that it seeks in this way to provide the means of com

pulsion through which performance of such service may be

secured.”

7

In Galveston, Harrisburg & San Antonio Railway v.

Texas, 210 U. S. 217, this court said, with reference to a

statute imposing a tax upon railroad companies equal to

one per cent, o f their gross receipts (at p. 227):—

“ A practical line can be drawn by taking the whole scheme

of taxation into account. This must be done by this court

as best it can. Neither the state courts nor the legislature,

by giving the tax a particular name or by the use of some

form of words, can take away our duty to consider its nature

and effect. If it bears upon commerce between the States

so directly as to amount to a regulation in a relatively im

mediate way, it will not be saved by name or form.”

• In Lochner v. New York, 198 U. S. 45, it was said with

reference to a statute limiting the hours of work in bakeries

(at p. 61):—

“ We do not believe in the soundness of the views which

uphold this law. On the contrary, we think that such a

law as this, although passed in the assumed exercise of the

police power, and as relating to the public health, or the

health of the employes named, is not within that power,

and is invalid. The act is not, within any fair meaning of

the term, a health law, but is an illegal interference with

the rights of individuals, both employers and employes,

to make contracts regarding labor upon such terms as they

may think best, or which they may agree upon with the

other parties to such contracts. Statutes of the nature of

that under review, limiting the hours in which grown and

intelligent men may labor to earn their living, are mere

meddlesome interferences with the rights of the individual,

and they are not saved from condemnation by the claim

that they are passed in the exercise of the police power

and upon the subject of the health of the individual whose

rights are interfered with, unless there be some fair ground,

reasonable in and of itself, to say that there is material

danger to the public health or to the health of the employes,

if the hours of labor are not curtailed.”

8

In Postal Telegraph-Cable Co. v. Taylor, 192 U. S. 64, it

was held that a municipal ordinance purporting to impose

a license fee for purposes of inspection on telegraph com

panies was void as being, in fact, an attempt to tax inter

state commerce. The court said (at p. 73): —

“ Courts are not to be deceived by the mere phraseology

in which the ordinance is couched.”

In Collins v. New Hampshire, 171 U. S. 30, it was held

that a statute forbidding the sale of oleomargarine unless

colored pink was unconstitutional because amounting to

an absolute prohibition. The court said (at p. 33):—

“ The direct and necessary result of a statute must be

taken into consideration when deciding as to its validity,

even if that result is not in so many words either enacted

or distinctly provided for. In whatever language a statute

may be framed, its purpose must be determined by its

natural and reasonable effect. Henderson v. Mayor of New

York, 92 U. S. 259; Morgan’s Steamship Co. v. Louisiana,

118 U. S. 455, at 462. Although under the wording of this

statute the importer is permitted to sell oleomargarine

freely and to any extent, provided he colors it pink, yet the

permission to sell, when accompanied by the imposition

of a condition which, if complied with, will effectually pre

vent any sale, amounts in law to a prohibition.”

In New Hampshire v. Louisiana, 108 U. S. 76, it was held

that the constitutional prohibition of suits against a state

by citizens of another state cannot be evaded by bringing

suit in the name of the latter state fcr the benefit of the

real claimants.

In Mobile v. Watson, 116 U. S. 289, it was held that the

obligations of a municipal corporation cannot be evaded by

dissolving the corporation and incorporating substantially

9

the same people as a municipal body under a new name for

the same general purposes, though the boundaries of the

new corporation differ from those of the old one.

The constitution of New York (Art. X , § 2) provides

that “ all city, town and village officers . . . shall be elected

by the electors of such cities, towns and villages, or of some

division thereof, or appointed by such authorities thereof as

the legislature shall designate for that purpose.” A stat

ute abolished the police force of Troy and established the

so-called “ Rensselaer Police District,” to be administered

by officers appointed by the governor. This district con

sisted of the city of Troy together with three small patches

of territory adjoining the city on different sides and em

bracing in all less than one square mile. It was held that

the act was void as an attempt to evade the constitutional

requirement quoted above, the court saying (at p. 55 and

p. 68):—

“ A written Constitution must be interpreted and effect

given to it as the paramount law of the land, equally obliga

tory upon the legislature as upon other departments of

government and individual citizens, according to its spirit

and the intent of its framers, as indicated by its terms.

An act violating the true intent and meaning of the instru

ment, although not within the letter, is as much within the

purview and effect of a prohibition as if within the strict

letter; and an act in evasion of the terms of the Constitu

tion, as properly interpreted and understood, and frustrating

its general and clearly expressed or necessarily implied pur

pose, is as clearly void as if in express terms forbidden. A

thing within the intent of a Constitution or statutory enact

ment is, for all purposes, to be regarded as within the words

and terms of the law. . . .

“ The experiment in the act before us was to see with how

little disturbance of the political organizations of the towns

adjacent to the city of Troy, or the change of boundary lines,

a police district could be established which would abide

10

the tests of the Constitution, and, as that is patent upon

the face of the act, it cannot be sustained as a valid and

effectual exercise of the power claimed to exist in the legis

lature, to constitute a single police district from the whole

or a part of several distinct municipal organizations, each

constituting a substantial part of the new district, and being

within the necessities leading to its creation, and having

the benefits of the new organization.”

People v. Albertson, 55 N. Y. 50.

In State v. Jones, 66 Ohio St. 453, it was held that

a statute designed to reorganize the police force of Toledo

under color of regulating the police force “ in cities of the

third grade of the first class” was repugnant to the 13th

article of the constitution of Ohio, which required that the

general assembly should “ pass no special act conferring

corporate powers.” The court said (at p. 487):—

“ In view of the trivial differences in population, and of the

nature of the powers conferred, it appears . . . that the

present classification cannot be regarded as based upon

differences in population, or upon any other real or supposed

differences in local requirements. Its real basis is found in

the differing views or interests of those who promote legis

lation for the different municipalites of the state. An in

tention to do that which would be violative of the organic

law should not be imputed upon mere suspicion. But the

body of legislation relating to this subject shows the legis

lative intent to substitute isolation for classification, so that

all the municipalities of the state which are large enough to

attract attention shall be denied the protection intended

to be afforded by this section of the constitution.”

In Henderson v. Mayor of New York, 92 U. S. 259, with

reference to a statute purporting to be designed as a pro

tection against the importation of paupers, the court

said (at p. 268):—

11

“ In whatever language a statute may be framed, its pur

pose must be determined by its natural and reasonable effect;

and if it is apparent that the object of this statute, as judged

by that criterion, is to compel the owners of vessels to pay

a sum of money for every passenger brought by them from

a foreign shore, and landed at the port of New York, it is

as much a tax on passengers if collected from them, or a tax

on the vessel or owners for the exercise of the right of landing

their passengers iu that city, as was the statute held void

in the Passenger Cases [7 How. 283].”

In Smith v. St. Louis & Southwestern Railway, 181 U. S.

248, the court said, with reference to certain state quaran

tine regulations (at p. 257):—

“ What . . . is a proper quarantine law—what a proper

inspection law in regard to cattle—has not been declared.

Under the guise of either a regulation of commerce will not

be permitted. Any pretence or masquerade will be dis

regarded and the true purpose of a statute ascertained.”

On these principles this court has repeatedly held that it

must look into the practical working of statutes purporting

to establish inspection or quarantine regulations, and has

declared such statutes invalid if they effect a substantial

prohibition of interstate commerce or virtually impose a

tax thereon, however carefully the real purpose may be

concealed.

Chy Lung v. Freeman, 92 U. S. 275.

Hannibal & St. Joseph Railroad v. Ilusen, 95

U. S. 465, 473.

Minnesota v. Barber, 136 U. S. 313.

Brimmer v. Rebman, 138 U. S. 78.

Voiglit v. Wright, 141 U. S. 62.

Scott v. Donald, 165 U. S. 58, 98.

Schollenberger v. Pennsylvania, 171 U. S. 1.

12

In determining how far this firmly established doctrine

applies to the present case, it is important to analyze the

amendment to the constitution of Oklahoma now in question.

In substance, this amendment provides that, without re

gard to educational qualifications, any adult male citizen

may vote unless (1) he was on January 1, 1866, a resident of

the United States, but not then entitled to vote in any state,

or unless (2) he is a descendant of such a person. In other

words, a negro who was born in the United States and

whose ancestors may have resided here for many genera

tions cannot vote unless he can read and write any sec

tion of the Oklahoma constitution, but a native of Siberia,

for example, who resided in that country on January 1,

1866, or whose ancestors then resided there, is entitled to

vote if he has been in the United States for the short period

necessary to obtain naturalization, although he m ay be

unable to read or write, and although he and all his an

cestors may have been living in a state of barbarism until

within five or six years ago.

This extraordinary result makes the purpose of the amend

ment almost too plain for argument. If it were not for the

exemption of foreigners and their descendants, it might con

ceivably be argued that the familiarity with our institutions

which may be inferred from the fact that a person is

descended from one who was a voter in 1866 might have

been deemed a valid reason for allowing such a person to

vote, even though he could not read or write. Such a

contention, it is submitted, would be altogether frivolous.

The choice of January 1, 1866, as the decisive date is in

itself enough to show conclusively what the real purpose

of the amendment was.

But not even this flimsy argument is open as the case

now stands. The effect of the amendment is to allow almost

anybody to vote, whatever his education or extraction, unless

he happens to be a negro, for it is as well known to the Court

13

as it was to the framers of the amendment that practically

all residents of the United States, other than negroes, en

joyed the right to vote in 1866.

There is no decision by this Court tending to uphold the

amendment now in question. In Williams v. Mississippi,

170 U. S. 213, the suffrage restrictions of the Mississippi

constitution were considered. It was held that the pro

vision that persons, who could understand the constitution

when read to them, should be allowed to vote did not on its

face discriminate between the races, and that, while such

discrimination was possible through partiality on the part

of the registrars, this possibility did not of itself offend

against the Fourteenth and Fifteenth Amendments. The

decision has, therefore, no application to the case at bar,

since here the discrimination, if any there be, appears on

the face of the amendment to the constitution of Oklahoma,

and in no way depends upon the determination of the regis

trars or other officers. The two cases relating to the Ala

bama constitution— Giles v. Harris, 189 U. S. 475, and

Giles v. Teasley, 193 U. S. 146— went off on questions of

procedure which are of no moment in the present case, as

this is a prosecution for the violation of Rev. Stat., § 5508

(now Section 19 of the Penal Code), which directly applies

to such a situation.

Ex parte Yarbrough, 110 U. S. 651.

Since the case comes before this court on a certificate,

the plaintiffs in error are not in a position to raise the objec

tion taken in the Alabama cases,— i.e., that, if the scheme

for registration is unconstitutional, the registrars have no

right to register any one. The Court has no jurisdiction

to pass upon the whole case on a certificate, and is limited to

answering the precise questions of law certified.

Maynard v. Hecht, 151 U. S. 324.

Graver v. Faurot, 162 U. S. 435.

14

But, if the point were open, this would not help the de

fendants because the Alabama cases arose under a new con

stitution which superseded all previous provisions, so that,

if the scheme of registration embodied therein was void,

there was no subsisting legislation on the subject. In the

present case the offending provisions are found in an

amendment to the constitution of Oklahoma. If this amend

ment is invalid, the result is to leave unaffected the original

provisions of that constitution, under which it was the duty

of election officers to receive the votes of all races without

discrimination.

It may be that the amendment affects adversely some few

persons other than negroes. In so far as it may operate

against Indians, this only strengthens the conclusion that

it was intended to be a measure of racial discrimination:

if it affects any other class of citizens,— e.g., those who

may have resided in 1866 in some state where they were

not allowed to vote for want of a necessary property quali

fication, or who may be the descendants of such persons,—

this makes it yet more clear that the amendment was not

framed with any sincere purpose to obtain an intelligent

electorate.

The case against the amendment is well summed up in

the following extract from the opinion of Judge Morris in a

case dealing with a Maryland statute of similar purport:—

“ It is true that the words ‘ race’ and ‘ color’ are not used

in the statute of Maryland, but the meaning of the law is

as plain as if the very words had been made use of; and it

is the meaning, intention, and effect of the law, and not its

phraseology, which is important. No possible meaning

for this provision has been suggested except the discrimina

tion which by it is plainly indicated. . . .

“ There are restrictions of the right of voting which might

in fact operate to exclude all colored men, which would not

be open to the objection of discriminating on account of

15

race or color. As, for instance, it is supposable that a prop

erty qualification might, in fact, result in some localities

in all colored men being excluded; and the same might be

the result, in some localities, from an educational test. And

it could not be said, although that was the result intended,

that it was a discrimination on account of race or color, but

would be referable to a different test. But looking at the

Constitution and laws of Maryland prior to January 1,

1868, how can it be said, with any show of reason, that any

but white men could vote then? And how can the court

close its eyes to the obvious fact that it is for that reason

solely that the test is inserted in the Maryland act of 1908,

and is not the court to take notice of the fact that, during

all the 40 years since the adoption of the fifteenth amend

ment, colored men have been allowed to register and vote

in Maryland until the enactment of the Maryland statute

of 1908?”

Anderson v. Myers, 182 Fed. Rep. 223.

This Court has already taken notice of the object aimed

at by a historic circumlocution in the federal constitution,

and it cannot do otherwise in the case at bar.

In People v. Compagnie Generate Transatlantique, 107

U. S. 59, referring to Art. I, § 9 of the Constitution (which

relates to “ the migration or importation of such persons as

any of the States now existing may think proper to adm it” ),

the Court said:—

“ There has never been any doubt that this clause had

exclusive reference to persons of the African race. The two

words 'migration’ and ‘ importation’ refer to the different

conditions of this race as regards freedom and slavery.

When the free black man came here, he migrated; when

the slave came, he was imported.”

Although these considerations are decisive, it may not be

unprofitable to quote the language of Section 3 of the en

16

abling act under which Oklahoma was admitted to the

Union:—

“ The constitution shall be republican in form, and make

no distinction in civil or political rights on account of race

or color, and shall not be repugnant to the Constitution

of the United States and the principles of the Declaration

of Independence” (34 Stat. 269).

The present case does not call for a determination of the

important question how far the requirements of the en

abling act constitute a check on action by the State after

its admission. If the provisions in question constitute a

“ distinction in civil or political rights on account of race

or color,” they are necessarily “ repugnant to the Con

stitution of the United States,” because the right to which

they relate is one protected against such distinctions by

the express language of the Constitution.

The enabling act is nevertheless significant as showing

that Oklahoma obtained admission to the Union only with

the most definite understanding that the rights of her citi

zens were to be in no way dependent on considerations of

race or color. Indeed, the prohibition of distinctions on

account of race or color indicates a desire on the part of

Congress to prevent such distinctions as to all civil and

political rights whatever,— even as to those, if any there

be, not already protected by the Constitution.

If the amendment now in question can stand, it means

that a state received into the Union on these stringent

terms may, immediately after her admission, make sport

of her solemn obligations and by a transparent subterfuge

set at naught the Constitution of the United States itself.

The real question for decision is whether the court is to

be “ deceived by the mere phraseology” into permitting

such a flagrant breach of the fundamental law. To this

question, it is submitted, there can be only one answer.

17

We respectfully urge that this is not a case where the

Court should be ingenious in construing the language of the

amendment in question so as to effectuate the purpose of

its framers and nullify the Constitution of the United States,

and that the Court should rather look through all subtleties

and throw its great weight against all efforts to take away

the rights which the Constitution secures to every citizen.

Especially is this true now when on every hand race preju

dice is exercising a most baleful influence in our affairs

and in the language of Mr. Justice Bradley opposes “ an

impediment to securing to individuals of the [colored]

race that equal justice which the law aims to secure to all

others” ; when, in a word, it is used to keep men down

who ought to be helped up.

M OORFIELD STOREY.

■

C E R T IF IC A T E

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES.

October T e r m , 19 1&

N o

FRANK GUINN AND J. J. BEAL

vs.

THE UNITED STATES.

ON A CER TIFICATE FROM TH E UNITED STATES CIRCUIT COURT OF

APPEALS FOR TH E EIGHTH CIRCUIT.

FILED JANUARY 13, 1913.

(28,498)

SUPREME COURT OE THE UNITED STATES.

Oc to b e r Te r m , 1912.

No. 923.

FRANK GUINN AND J. J. BEAL

vs.

THE UNITED STATES.

ON A CERTIFICATE FROM THE UNITED STATES CIRCUIT COURT OF

APPEALS FOR THE EIGHTH CIRCUIT.

INDEX.

Original. Print.

Certificate from the United States Circuit Court of Appeals for

the Eighth Circuit___________________________________ 1 j

Statement__________________________________ 7 4

Questions certified_________________________________ 7 4

Judges’ certificate_____________________ 1___________ 7 4

Clerk’s certificate_____________________________________ g 4

77566—13 !

GUINN AND BEAL VS. UNITED STATES. 1

1 United States Circuit Court of Appeals, Eighth Circuit.

December term, A. D. 1912.

F r a n k G u in n an d J. J. B e a l , pl a in t if f s in error.1

vs. No. 3736.

U n ited S tates of A m e r ic a , d efen d an t in error, j

The United States Circuit Court of Appeals for the Eighth Cir

cuit, sitting at St. Louis, Missouri, on the sixteenth day of December,

A. D. 1912, certifies that the record in the case above entitled which

is pending in this court upon a writ o f error to review a judgment of

conviction of Frank Guinn and J. J. Beal o f the offense of wilfully

and corruptly conspiring .to injure, oppress, and intimidate, on

account of their race and color, certain negro citizens named in the

indictment, who were electors qualified to vote for a Member of Con

gress in the congressional district and in the precinct in Oklahoma in

which they resided, in the free exercise and enjoyment o f the right

and privilege secured to them by the Constitution and laws of the

United States to vote for a qualified candidate for such Member of

Congress at the general election on November 8, 1910, in violation of

section 5508 o f the Revised Statutes, now section 19 o f the Penal

Code, discloses these facts:

The defendants below were duly indicted for the offense

2 of which they were convicted; they were arraigned; they

pleaded not guilty; they were tried by a jury which found a

verdict against them; they were convicted and they were sentenced

to serve one year in the penitentiary at Leavenworth, Kansas, and

each to pay a fine of one hundred dollars, and they have sued out a

writ of error to this court to review the judgment against them. The

indictment charged that the defendants below wilfully and corruptly

conspired together to injure, oppress, and intimidate, on account of

their race and color, certain negro citizens named in the indictment

who were qualified to vote for a qualified candidate for a Member of

Congress in the congressional district and in the precinct in which

they resided, in the full exercise and enjoyment of the right and

privilege secured to each of them by the Constitution and laws of

the United States to vote for a qualified person for a Member o f Con

gress at the general election on November 8, 1910, and to prevent

them from exercising that right and privilege, and from voting for a

Member of Congress, and that in pursuance of said conspiracy and

to effect its object the defendants below, who were members of the

election_board_of the precinct in which the negro citizens were en

titled to vote, did, by illegal oppression, intimidation, and threats

deny and prevent the exercise by these negro citizens o f their right

to vote for a qualified candidate for a Member of Congress at the

election named, although the negro citizens repeatedly demanded

and sought to exercise that, right and privilege at the time and place

of the election in their precinct. At the trial o f the case there was

2 GUINN AND BEAL VS. UNITED STATES.

substantial evidence that the defendants were members of the elec

tion board of the precinct in which the negro citizens named in the

indictment resided, and that the defendants wilfully and cor-

3 ruptly conspired together to injure, oppress, and intimidate

some of these negro citizens named in the indictment as therein

charged, and that in pursuance of that conspiracy they so oppressed

and intimidated them in the free exercise of their right and privilege

o f voting for a qualified candidate for a Member of Congress that

they prevented them from exercising, deprived them of, and denied

them that right and privilege.

The original constitution of the State of Oklahoma provided, with

certain exceptions not material in this case, that “ the qualified elec

tors of the State shall be male citizens of the United States,

male citizens of the State, and male persons of Indian descent

native of the United States, who are over the age o f twenty-

one years, who have resided in the State one year, in the county

six months, and in the election precinct thirty days next preced

ing the election at which any such elector offers to vote. (Con

stitution of Oklahoma, art. 3,' sec. 1.) There was undisputed testi

mony at the trial that the negro citizens named in the indictment

were qualified electors entitled to vote for a qualified candidate for

a Member o f Congress under that constitution. But in 1910, prior

to the eighth day of November in that year, the day of the general

election, this amendment to that constitution was adopted: “ No per

son shall be registered as an elector of this State, or be allowed to vote

in any election herein, unless he be able to read and write any section

o f the constitution of the State of Oklahoma. And no person who

was, on January 1, 18G6, or at any time prior thereto, entitled to vote

under any form of government, or who at that time resided in some

foreign nation, and no lineal descendant of such person, shall

4 be denied the right to register and vote because of his inability

to so read and write sections o f such constitution. Precinct

election inspectors having in charge the registration of electors shall

enforce the provisions of this section at the time of registration, pro

vided registration be required. Should registration be dispensed

with, the"provisions o f this section shall be enforced by the precinct

election officer when electors apply for ballots to vote. There was

substantial testimony at the trial that several of the negro citizens

named in the indictment were not, and that their lineal ancestors were

not, entitled to vote under any form of government on January 1.

1866, or at any time prior thereto, and that each of them, or each of

his lineal ancestors, at that time resided in the United States and was

a slave; that the defendants claimed that by reason of this amend

ment these negro citizens were deprived of their right to vote for a

qualified candidate for a Member of Congress unless they were able

to read and write and unless they did read and write, in the presence

o f the defendants, any such section o f the constitution of Oklahoma

which the defendants selected. That, on the other hand, the negro

citizens claimed at the election, and the United States insisted at the

GUINN AND BEAL VS. UNITED STATES. 3

trial, that the amendment was unconstitutional and void, and that

the negro citizens who, the evidence introduced at the trial proved,

were in all other respects qualified to vote for a qualified candidate

for a Member of Congress, were qualified so to vote, although they

were not able to read or write, and did not read or write any section

of the constitution of Oklahoma.

The trial court, speaking of the negro citizens named in the indict

ment, charged the jury, among other things, in these words:

5 “ As the evidence on the point is undisputed, I take it you will

have no difficulty in concluding that a number, or several, of

these colored voters (referring to the negro citizens named in the

indictment) were entitled to vote for congressional candidates in

Union Township precinct (the precinct in which they resided) and

were deprived o f such right. * * * The fourteenth amendment

declares them to be citizens if they were born in the United States

and subject to the jurisdiction thereof. I f they were citizens, and

otherwise qualified to vote, they had a right the same as all citizens

to be not discriminated against on account of their race or color.

This right is guaranteed by the fifteenth amendment to the Federal

Constitution, which provided that ‘ the right of citizens of the United

States to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United States on

account of race, color, or previous condition o f servitude.’ And Con

gress has also provided, by section 200-1. Revised Statutes, ‘ All citi

zens of the United States who are otherwise qualified by law to vote

at any election by the people of any State. Territory, district, munic

ipality, or other territorial subdivision, shall be entitled and allowed

to vote at all such elections without distinction o f race, color, or pre

vious condition of servitude; any constitution, law, custom, usage,

or regulation of any State or Territory, or by or under its authority,

to the contrary notwithstanding.’ * * * In the opinion of the

court, the State amendment which imposes the test of reading and

writing any section of the State constitution as a condition to voting

to persons not on or prior to January 1. I860), entitled to vote under

some form of government, or then resident in some foreign nation,

or a lineal descendant of such person, is not valid, but you may

consider it insofar as it was in good faith relied and acted upon

6 by the defendants in ascertaining their intent and motive. I f

you believe from the evidence that the defendants formed a

common design and cooperated in denying the colored voters of

Union Township precinct, or any of them, entitled to vote, the privi

lege of voting, but this was due to a mistaken belief sincerely enter

tained by the defendants as to the qualifications of the voters—that is,

if the motive actuating the defendants was honest, and they simply

erred in the conception of their duty—then the criminal intent requi

site to their guilt is wanting and they cannot be convicted. On the

other hand, if they knew or believed these colored persons were en

titled to vote, and their purpose was to unfairly and fraudulently

deny the right of suffrage to them, or any of them, entitled thereto,

4 GUINN AND BEAL VS. UNITED STATES.

on account of their race and color, then their purpose was a corrupt

one, and they cannot be shielded by their official positions.”

The evidence at the trial, and the charge of the court which have

been referred to in this certificate, together with the exceptions to the

rulings herein mentioned, were embodied in a bill of exceptions duly

settled by the court, a copy o f which forms a part of the transcript

o f the record before this court.

The fourteenth assignment of error made by the plaintiffs in error

is, “ The court erred in instructing the jury as follows: ‘ In the opin

ion of the court the State amendment, which imposes the test of read

ing and writing any section in the constitution as a condition to

voting to persons not on or prior to January 1, 1866, entitled to vote

under some form of government, or as a resident of some foreign

nation, or a lineal descendant of some such person, is not valid,’ and

an exception to this portion of the charge of the court was duly made

and preserved at the time it was given.”

7 And the Circuit Court of Appeals for the Eighth Circuit

further certifies that the following questions of law are pre

sented to it in the case above entitled, that a decision o f each of these

questions is indispensable to a determination o f the cause, and that

to the end that the cause may be properly determined and disposed

of, it desires the instruction of the Supreme Court of the United

States upon these questions:

1. Was the amendment to the constitution of Oklahoma, heretofore

set forth, valid?

2. Was that amendment void in so far as it attempted to debar

from the right or privilege of voting for a qualified candidate for a

Member of Congress in Oklahoma, unless they were able to read and

write any section of the constitution of Oklahoma, negro citizens of

the United States who were otherwise qualified to vote for a qualified

candidate for a Member of Congress in that State, but who were not,

and none of whose lineal ancestors was, entitled to vote under any

form of government on January 1, 1866, or at any time prior thereto,

because they were then slaves?

W alter H. S a n b o r n ,

W alte r I. S m it h ,

Circuit Judges.

C h ar les A. W illard ,

District Judge.

Filed Dec. 16, 1912. John D. Jordan, clerk.

8 United States Circuit Court of Appeals, Eighth Circuit.

I, John D. Jordan, clerk of the United States Circuit Court of A p

peals for the Eighth Circuit, do hereby certify that the foregoing

certificate in the case o f Frank Guinn and J. J. Beal, plaintiffs in

error, vs. United States of America, No. 3736, was duly filed and

entered o f record in my office by order of said court, and as directed

GUINN AND BEAL VS. UNITED STATES. 5

by said court, the said certificate is by me transmitted to the Supreme

Court o f the United States for its action thereon.

In testimony whereof, I hereunto subscribe my name and affix the

seal of the United States Circuit Court of ApjWals for the Eighth

Circuit, at the city o f St. Louis, Missouri, this sixteenth day of

December, A. D. 1912.

[seal .] J o h n D. J ordan ,

Clerk of the United States Circuit Court of

Appeals for the Eighth Circuit.

9 (Indorsed:) U. S. Circuit Court of Appeals, Eighth Cir

cuit. December term, 1912. No. 3736. Frank Guinn and

J. J. Beal, plaintiffs in error, vs. United States o f America. Certifi

cate of questions to the Supreme Court of the United States.

(Indorsement on cover:) File No. 23498. U. S. Circuit Court A p

peals, 8th Circuit. Term No., 923. Frank Guinn and J. J. Beal vs.

The United States. (Certificate.) Filed January 13th, 1913. File

No. 23498.

O

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES.

Mr. Chief Justice W h ite delivered the opinion of the Court.

This case is before us on a certificate drawn by the court below

as the basis of two questions which are submitted for our solution

in order to enable the court correctly to decide issues in a case

which it has under consideration. Those issues arose from an

indictment and conviction of certain election officers of the State

of Oklahoma (the plaintiffs in error) of the crime of having con

spired unlawfully, wilfully and fraudulently lo deprive certain

negro citizens, on account of their race and color, of a right to vote

at a general election held in that State in 1910, they being entitled

to vote under the state law and which right was secured to them

by the Fifteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United

States. The prosecution was directly concerned with Section 5508,

Revised Statutes, now Section 19 of the Penal Code which is as

follows:

“ If two or more persons conspire to injure, oppress, threaten, or

intimidate any citizen in the free exercise or enjoyment of any right

or privilege secured to him by the Constitution or laws of the

United States, or because of his having so exercised the same; or

if two or more persons go in disguise on the highway, or on the

premises of another, with intent to prevent or hinder his free

exercise or enjoyment of any right or privilege so secured, they

shall be fined not more than five thousand dollars and imprisoned

not more than ten years, and shall, moreover, thereafter be in

eligible to any office, or place of honor, profit, or trust created by the

Constitution or laws of the United States.”

We concentrate and state from the certificate only matters which

we deem essential to dispose of the questions asked.

No. 96.— O ctober T erm , 1914.

Frank Guinn and J. J. Beal,

vs.

The United States.

On a Certificate from the

United States Circuit

Court of Appeals for the

Eighth Circuit.

[June 21, 1915.]

2 Quinn et al. vs. The United States.

Suffrage in Oklahoma was regulated by Section 1, Article III of

the Constitution under which the State was admitted into the

Union. Shortly after the admission there was submitted an amend

ment to the Constitution making a radical change in that article

which was adopted prior to November 8, 1910. At an election

for members of Congress which followed the adoption of this

Amendment certain election officers in enforcing its provisions

refused to allow certain negro citizens to vote who were clearly

entitled to vote under the provision of the Constitution under

which the State was admitted, that is, before the amendment, and

who, it is equally clear, were not entitled to vote under the pro

vision of the suffrage amendment if that amendment governed.

The persons so excluded based their claim of right to vote upon the

original Constitution and upon the assertion that the suffrage

amendment was void because in conflict with the prohibitions of the

Fifteenth Amendment and therefore afforded no basis for denying

them the right guaranteed and protected by that Amendment.

And upon the assumption that this claim was justified and that

the election officers had violated the Fifteenth Amendment in

denying the right to vote, this prosecution, as we have said, was

commenced. At the trial the court instructed that by the Fifteenth

Amendment the States were prohibited from discriminating as to

suffrage because of race, color, or previous condition of servitude

and that Congress in pursuance of the authority which was con

ferred upon it by the very terms of the Amendment to enforce its

provisions had enacted the following (Rev. Stat. sec. 2004) :

“ All citizens of the United States who are otherwise qualified

by law to vote at any election by the people of any State, Territory,

district, municipality, or other territorial subdivision, shall be

entitled and allowed to vote at all such elections without distinction

of race, color, or previous condition of servitude; any constitution,

law, custom, usage, or regulation of any State or Territory, or

by or under its authority, to the contrary notwithstanding. ’ ’

It then instructed as follows:

“ The State amendment which imposes the test of reading and

writing any section of the State constitution as a condition to

voting to persons not on or prior to January 1, 1866, entitled to

vote under some form of government, or then residents in some

foreign nation, or a lineal descendant of such person, is not valid,

but you may consider it in so far as it was in good faith relied and

acted upon by the defendants in ascertaining their intent and

motive. I f you believe from the evidence that the defendants formed

Quinn et al. vs. The United States. 3

a common design and cooperated in denying the colored voters of

Union Township precinct, or any of them, entitled to vote, the

privilege of voting, but this was due to a mistaken belief sincerely

entertained by the defendants as to the qualifications of the voters—

that is, if the motive actuating the defendants was honest, and

they simply erred in the conception of their duty—then the criminal

intent requisite to their guilt is wanting and they cannot be con

victed. On the other hand, if they knew or believed these colored

persons were enitled to vote, and their purpose was to unfairly

and fraudulently deny the right of suffrage to them, or any of

them entitled thereto, on account of their race and color, then

their purpose was a corrupt one, and they cannot be shielded by

their official positions. ’ ’

The questions which the court below asks are these:

“ 1. Was the amendment to the constitution of Oklahoma, here

tofore set forth valid ?

“ 2. Was that amendment void in so far as it attempted to debar

from the right or privilege of voting for a qualified candidate for

a Member of Congress in Oklahoma unless they were able to read and

write any section of the constitution of Oklahoma, negro citizens of

the United States who were otherwise qualified to vote for a

qualified candidate for a Member of Congress in that State, but

who were not, and none of whose lineal ancestors was, entitled to

vote under any form of government on January 1, 1866, or at any

time prior thereto, because they were then slaves ? ’ ’

As these questions obviously relate to the provisions concerning

suffrage in the original constitution and the amendment to those

provisions which forms the basis of the controversy, we state the text

of both. The original clause so far as material was this:

“ The qualified electors of the State shall be male citizens of the

United States, male citizens of the State, and male persons of

Indian descent native of the United States, who are over the age

of twenty-one years, who have resided in the State one year, in the

county six months, and in the election precinct thirty days, next

preceding the election at which any such elector offers to vote. ’ ’

And this is the amendment:

“ No person shall be registered as an elector of this State or be

allowed to vote in any election herein, unless he be able to read and

write any section of the constitution of the State of Oklahoma;

but no person who was, on January 1, 1866, or at any time prior

thereto, entitled to vote under any form of government, or who

at that time resided in some foreign nation, and no lineal descend

ant of such person, shall be denied the right to register and vote

because of his inability to so read and write sections of such

constitution. Precinct election inspectors having in charge the

4 Guinn et al. vs. The United States.

registration of electors shall enforce the provisions of this section

at the time of registration, provided registration be required.

Should registration be dispensed with, the provisions of this section

shall be enforced by the precinct election officer when electors apply

for ballots to vote.”

Considering the questions in the light of the text of the suffrage

amendment it is apparent that they are twofold because of the

twofold character of the provisions as to suffrage which the amend

ment contains. The first question is concerned with that pro

vision of the amendment which fixes a standard by which the

right to vote is given upon conditions existing on January 1, 1866,

and relieves those coming within that standard from the standard

based on a literacy test which is established by the other provision

of the amendment. The second question asks as to the validity of

the literacy test and how far, if intrinsically valid, it would con

tinue to exist and be operative in the event the standard based

upon January 1, 1866 should be held to be illegal as violative of the

Fifteenth Amendment.

To avoid that which is unnecessary let us at once consider and

sift the propositions of the United States on the one hand and of

the plaintiffs in error on the other, in order to reach with precision

the real and final question to be considered. The United States

insists that the provision of the amendment which fixes a standard

based upon January 1, 1866 is repugnant to the prohibitions of the

Fifteenth Amendment because in substance and effect that pro

vision, if not an express, is certainly an open repudiation of the

Fifteenth Amendment and hence the provision in question was

stricken with nullity in its inception by the self-operative force of

the Amendment, and as the result of the same power was at all

subsequent times devoid of any vitality whatever.

/ For the plaintiffs in error on the other hand it is said the States

have the power to fix standards for suffrage and that power was not

taken away by the Fifteenth Amendment but only limited to the

extent of the prohibitions which that Amendment established. This

being true, as the standard fixed does not in terms make any dis

crimination on account of race, color, or previous condition of servi

tude, since all, whether negro or white, who come within its require

ments enjoy the privilege of voting, there is no ground upon which

to rest the contention that the provision violates the Fifteenth

Amendment. This, it is insisted, must be the case unless it is in

tended to expressly deny the state’s right to provide a standard for

Guinn et al. vs. The United States.

suffrage, or what is equivalent thereto, to assert: a, that the judg

ment of the State exercised in the exertion of that power is subject

to Federal judicial review or supervision, or h, that it may be

questioned and be brought within the prohibitions of the Amend

ment by attributing to the legislative authority an occult motive

to violate the Amendment or by assuming that an exercise of the

otherwise lawful power may be invalidated because of conclusions

concerning its operation in practical execution and resulting dis

crimination arising therefrom, albeit such discrimination was not

expressed in the standard fixed or fairly to be implied but simply

arose from inequalities naturally inhering in those who must come

within the standard in order to enjoy the right to vote.

On the other hand the United States denies the relevancy of

these contentions. It says state power to provide for suffrage is not

disputed, although, of course, the authority of the Fifteenth

Amendment and the limit on that power which it imposes is

insisted upon. Hence, no assertion denying the right of a state

to exert judgment and discretion in fixing the qualification of

suffrage is advanced and no right to question the motive of the

state in establishing a standard as to such subjects under such

circumstances or to review or supervise the same is relied upon and

no power to destroy an otherwise valid exertion of authority upon

the mere ultimate operation of the power exercised is asserted. And

applying these principles to the very case in hand the argument of

the Government in substance says: No question is raised by the

Government concerning the validity of the literacy test provided

for in the amendment under consideration as an independent

standard since the conclusion is plain that that test rests on the

exercise of state judgment and therefore cannot be here assailed

either by disregarding the state’s power to judge on the subject

or by testing its motive in enacting the provision. The real question

involved, so the argument of the Government insists, is the re

pugnancy of the standard which the amendment makes, based upon

the conditions existing on January 1st, 1866, because on its face

and inherently considering the substance of things, that standard

is a mere denial of the restrictions imposed by the prohibitions of

the Fifteenth Amendment and by necessary result re-creates and

perpetuates the very conditions which the Amendment was intended

to destroy. From this it is urged that no legitimate discretion could

have entered into the fixing of such standard which involved only

6 Guinn et al. vs. The United States.

the determination to directly set at naught or by indirection avoid

the commands of the Amendment. And it is insisted that nothing

contrary to these propositions is involved in the contention of the

Government that if the standard which the suffrage amendment

fixes based upon the conditions existing on January 1,1866, be found

to be void for the reasons urged, the other and literacy test is also

void, since that contention rests, not upon any assertion on the part

of the Government of any abstract repugnancy of the literacy

test to the prohibitions of the Fifteenth Amendment, but upon the

relation between that test and the other as formulated in the

suffrage amendment and the inevitable result which it is deemed

must follow from holding it to be void if the other is so declared

to be.

Looking comprehensively at these contentions of the parties it

plainly results that the conflict between them is much narrower than

it would seem to be because the premise which the arguments of

the plaintiffs in error attribute to the propositions of the United

States is by it denied. On the very face of things it is clear that

the United States disclaims the gloss put upon its contentions by

limiting them to the propositions which we have hitherto pointed

out, since it rests the contentions which it mates as to the assailed

provision of the suffrage amendment solely upon the ground that

it involves an unmistakable, although it may be a somewhat dis

guised, refusal to give effect to the prohibitions of the Fifteenth

Amendment by creating a standard which it is repeated but calls

to life the very conditions which that Amendment was adopted

to destroy and which it had destroyed.

The questions then are: (1) Giving to the propositions of the

Government the interpretation which the Government puts upon

them and assuming that the suffrage provision has the significance

which the Government assumes it to have, is that provision as a

matter of law repugnant to the Fifteenth Amendment ? which leads

us of course to consider the operation and effect of the Fifteenth

Amendment. (2) I f yes, has the assailed amendment in so far

as it fixes a standard for voting as of January 1, 1866, the meaning

which the Government attributes to it? which leads us to analyze

and interpret that provision of the amendment. (3) I f the investi

gation as to the two prior subjects establishes that the standard

fixed as of January 1, 1866, is void, what if any effect does that

conclusion have upon the literacy standard otherwise established by

the amendment ? which involves determining whether that standard,

Guinn ei al vs. The United States. 7

if legal, may survive the recognition of the fact that the other or

1866 standard has not and never had any legal existence. Let

us consider these subjects under separate headings.

1. The operation and effect of the Fifteenth Amendment. This

is its text:

“ Section 1. The right of citizens of the United States to vote

shall not he denied or abridged by the United States or by any

State on account of race, color, or previous condition of servitude.

‘ ‘ Section 2. The Congress shall have power to enforce this article

by appropriate legislation.”

(a) Beyond doubt the Amendment does not take away from the

state governments in a general sense the power over suffrage which

has belonged to those governments from the beginning and without

the possession of which power the whole fabric upon which the

division of state and national authority under the Constitution

and the organization of both governments rest would be without

support and both the authority of the nation and the state would

fall to the ground. In fact, the very command of the Amendment

recognizes the possession of the general power by the State, since

the Amendment seeks to regulate its exercise as to the particular

subject with which it deals.

(b) But it is equally beyond the possibility of question that the

Amendment in express terms restricts the power of the United

States or the States to abridge or deny the right of a citizen of

the United States to vote on account of race, color or previous con

dition of servitude. The restriction is coincident with the power

and prevents its exertion in disregard of the command of the

Amendment. But while this is true, it is true also that the Amend

ment does not change, modify or deprive the States of their full

power as to suffrage except of course as to the subject with which

the Amendment deals and to the extent that obedience to its com

mand is necessary. Thus the authority over suffrage which the

States possess and the limitation which the Amendment imposes

are coordinate and one may not destroy the other without bringing

about the destruction of both.

(c) While in the true sense, therefore, the Amendment gives no

right of suffrage, it was long ago recognized that in operation its

prohibition might measureably have that effect; that is to say, that

as the command of the Amendment was self-executing and reached

without legislative action the conditions of discrimination against

8 Quinn et al vs. The United States.

which it was aimed, the result might arise that as a consequence of

the striking down of a discriminating clause a right of suffrage

would be enjoyed by reason of the generic character of the pro

vision which would remain after the discrimination was stricken

out. Ex parte Yarborough, 110 U. S. 651; Neal v. Delaware, 103

U. S. 370. A familiar illustration of this doctrine resulted from the

effect of the adoption of the Amendment on state constitutions in

which at the time of the adoption of the Amendment the right of

suffrage was conferred on all white male citizens, since by the

inherent power of the Amendment the word white disappeared and

therefore all male citizens without discrimination on account of

race, color or previous condition of servitude came under the generic

grant of suffrage made by the state.

With these principles before us how can there be room for any

serious dispute concerning the repugnancy of the standard based

upon January 1, 1866, (a date which preceded the adoption of the

Fifteenth Amendment), if the suffrage provision fixing that standard

is susceptible of the significance which the Government attributes

to it? Indeed, there seems no escape from the conclusion that to

hold that there was even possibility for dispute on the subject

would be but to declare that the Fifteenth Amendment not only

had not the self-executing power which it has been recognized

to have from the beginning, but that its provisions were wholly

inoperative because susceptible of being rendered inapplicable by

mere forms of expression embodying no exercise of judgment and

resting upon no discernible reason other than the purpose to dis

regard the prohibitions of the amendment by creating a standard

of voting which on its face was in substance but a revitalization of

conditions which when they prevailed in the past had been destroyed

by the self-operative force of the Amendment.

2. The standard of January 1, 1866, fixed in the suffrage amend

ment and its significance.

The inquiry of course here is, Does the amendment as to the

particular standard which this heading embraces involve the mere

refusal to comply with the commands of the Fifteenth Amendment

as previously stated? This leads us for the purpose of the

analysis to recur to the text of the suffrage amendment. Its opening

sentence fixes the literacy standard which is all-inclusive since it is

general in its expression and contains no word of discrimination

on account of race or color or any other reason. This however is

Guinn et al vs. The United States. 9

immediately followed by the provisions creating the standard based

upon the condition existing on January 1, 1866, and carving out

those coming under that standard from the inclusion in the literacy

test which would have controlled them but for the exclusion thus

expressly provided for. The provision is this:

“ But no person who was, on January 1, 1866, or at any time

prior thereto, entitled to vote under any form of government, or

who at that time resided in some foreign nation, and no lineal

descendant of such person, shall be denied the right to register and

vote because of his inability to so read and write sections of such

constitution. ’ ’

We have difficulty in finding words to more clearly demonstratej

the conviction we entertain that this standard has the characteristics

which the Government attributes to it than does the mere statement

of the text. It is true it contains no express words of an exclusion

from the standard which it establishes of any person on account of

race, color, or previous condition of servitude prohibited by the F if

teenth Amendment, but the standard itself inherently brings that

result into existence since it is based purely upon a period of time

before the enactment of the Fifteenth Amendment and makes tha1

period the controlling and dominant test of the right of suffrage

In other words, we seek in vain for any ground which would

sustain any other interpretation but that the provision, recurring

to the conditions existing before the Fifteenth Amendment was

adopted and the continuance of which the Fifteenth Amendment

prohibited, proposed by in substance and effect lifting those condi

tions over to a period of time after the Amendment to make

them the basis of the right to suffrage conferred in direct and

positive disregard of the Fifteenth Amendment. And the same

result, we are of opinion, is demonstrated by considering whether

it is possible to discover any basis of reason for the standard thus

fixed other than the purpose above stated. We say this because

we are unable to discover how, unless the prohibitions of the F if

teenth Amendment were considered, the slightest reason was af

forded for basing the classification upon a period of time prior to

the Fifteenth Amendment. Certainly it cannot be said that

there was any peculiar necromancy in the time named which

engendered attributes affecting the qualification to vote which would

not exist at another and different period unless the Fifteenth

Amendment was in view.

10 Quinn et al vs. The United States.

While these considerations establish that the standard fixed

on the basis of the 1866 test is void, they do not enable us to

reply even to the first question asked by the court below, since to

do so we must consider the literacy standard established by the

suffrage amendment and the possibility of its surviving the deter

mination of the fact that the 1866 standard never took life since

it was void from the beginning because of the operation upon it

of the prohibitions of the Fifteenth Amendment. And this brings

us to the last heading:

3. The determination of the validity of the literacy test and the

possibility of its surviving the disappearance of the 1866 standard

with which it is associated in the suffrage amendment.

No time need be spent on the question of the validity of the

literacy test considered alone since as we have seen its establish

ment was but the exercise by the State of a lawful power vested

in it not subject to our supervision, and indeed, its validity is ad

mitted. Whether this test is so connected with the other one re

lating to the situation on January 1, 1866, that the invalidity of

the latter requires the rejection of the former is really a question

of state law, but in the absence of any decision on the subject by

the Supreme Court of the State, we must determine it for our

selves. We are of opinion that neither forms of classification

nor methods of enumeration should be made the basis of striking

down a provision which was independently legal and therefore was