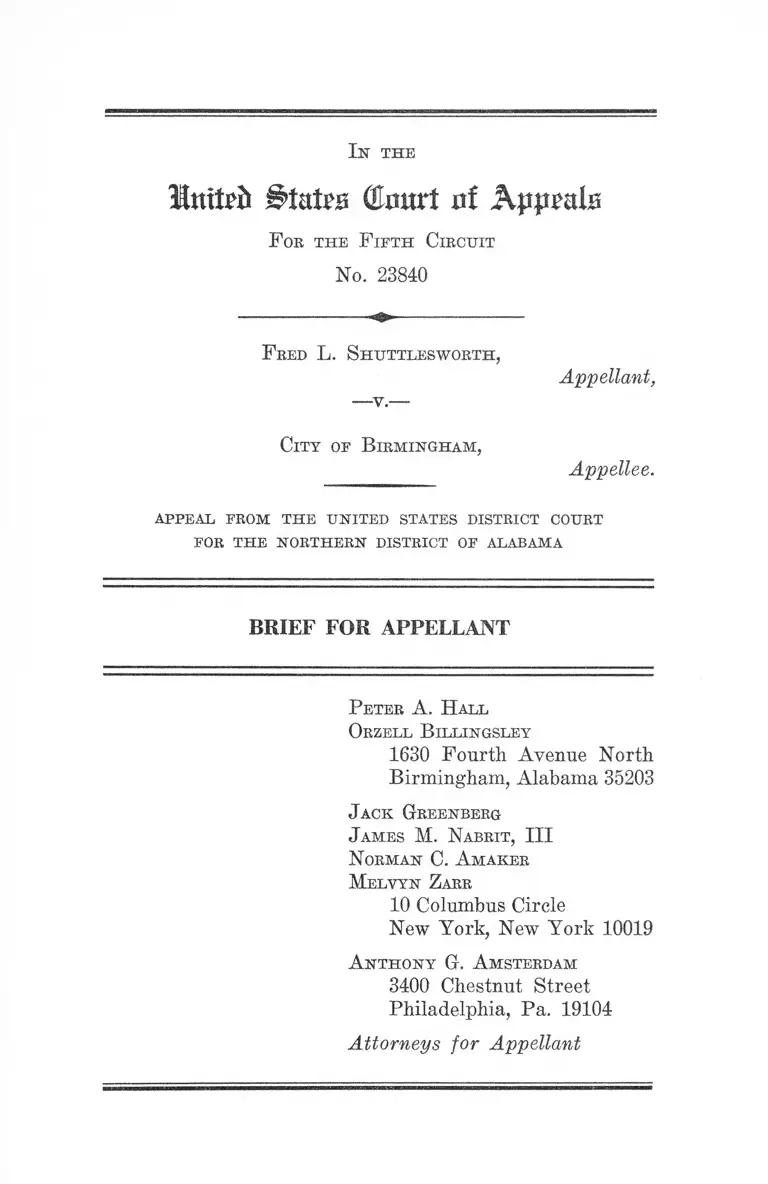

Shuttlesworth v Birmingham AL Brief for Appellant

Public Court Documents

January 13, 1967

13 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Shuttlesworth v Birmingham AL Brief for Appellant, 1967. 8e26a55a-c49a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c17302fc-b565-412a-9d2e-de548ffc8fff/shuttlesworth-v-birmingham-al-brief-for-appellant. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

Initeft States QJnurt ni Appeals

F or the F ifth Circuit

No. 23840

In th e

F bed L. Shuttlesworth,

Appellant,

City of B irmingham,

Appellee.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ALABAMA

BRIEF FOR APPELLANT

Peter A. Hall

Orzell B illingsley

1630 Fourth Avenue North

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

Jack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, III

Norman C. A maker

Melvyn Zarr

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

A nthony G. A msterdam

3400 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, Pa. 19104

Attorneys for Appellant

I N D E X

PAGE

Statement of the C ase........................................................ 1

Specification of Error ........................................................ 4

A bgument :

Appellant’s Prosecution Is Removable to Fed

eral Court Pursuant to 28 U. S. C. §1443(1) Be

cause the Unconstitutional Nature of the Prosecu

tion May Be Established Without an Evidentiary

Hearing ...................................................... 4

Conclusion ............................................................................... 8

T able oe Cases

Bush v. Kentucky, 107 U. S. 110 (1883) .......................... 5

City of Greenwood v. Peacock, 384 U. S. 808

(1966) ......................................................................... 4, 6, 7, 8

Dombrowski v. Pfister, 380 U. S. 479 (1965) ............... 6

Georgia v. Rachel, 384 U. S. 780 (1966) .......................... 7, 8

Kentucky v. Powers, 201 U. S. 1 (1906) ........................ 7

Kentucky v. Powers, 139 Fed. 452 (E. D. Ky. 1905) .... 5

Shuttlesworth v. City of Birmingham, 368 U. S. 959

(1962) ............................................................................... 6

In re Shuttlesworth, 369 U. S. 35 (1962) ....................... 6

11

PAGE

Shuttlesworth v. City of Birmingham, 373 U. S. 262

(1963) ........ 6

Shuttlesworth v. City of Birmingham, 376 U. S. 339

(1964) ..... 6

Shuttlesworth v. City of Birmingham, 382 U. S. 87

(1965) .............................................. 2,5,8

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U. S. 303 (1879) ........... 7

Statutes and Ordinances Involved

28 U. S. C. §1443(1) (1964) ............................................. 1,4,7

28 U. S. C. §1446(c) (1964) ........................................... 5

42 U. S. C. §1981 (1964) .................................................... 4

Birmingham General City Code, §1142..................... 2

Birmingham General City Code, §1231 ..................... 2

In th e

ItttteJi States Qkwrt ni Appmh

F ob the F ifth Circuit

No. 23840

F eed L. Shuttlesworth,

-v.-

Appellant,

City of B irmingham,

Appellee.

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT COURT

FOR THE NORTHERN DISTRICT OF ALABAMA

BRIEF FOR APPELLANT

Statement of the Case

This is an appeal from an order of the United States

District Court for the Northern District of Alabama re

manding appellant’s criminal prosecution to the Alabama

state court from which it was removed pursuant to 28

U. S. C. §1443(l).* 1

Prosecution of appellant, a well-known civil rights leader

(R.. 2-3), was initiated by the City of Birmingham on April

1 §1443. Civil Bights Cases.

Any of the following civil actions or criminal prosecutions, com

menced in a State court may be removed by the defendant to the

district court of the United States for the district and division

embracing the place wherein it is pending:

(1) Against any person who is denied or cannot enforce

in the courts of such State a right under any law providing

for the equal civil rights of citizens of the United States, or

of all persons within the jurisdiction thereof . . .

2

4,1962. He was charged with violating §§11422 and 12313 of

the Birmingham General City Code, brought to trial in the

Circuit Court of Jefterson County, convicted and sentenced

to 180 days at hard labor and an additional 61 days at hard

labor in default of a $100.00 fine and costs. Appellant’s

conviction was affirmed by the Alabama Court of Appeals,

42 Ala. App. 296, 161 So. 2d 796, and the Supreme Court

of Alabama declined review. 276 Ala. 707, 161 So. 2d 799.

On November 15, 1965, the Supreme Court of the United

States reversed appellant’s convictions, holding that his

conviction under §1142 was based upon a possible uncon

stitutional construction of that ordinance and that his con

viction under §1231 was based upon no evidence of guilt.

Shuttlesworth v. City of Birmingham, 382 U. S. 87 (1965).

The Alabama Court of Appeals, on remand from the Su

preme Court of the United States, remanded the case to

the Circuit Court of Jefferson County (181 So. 2d 628). On

May 17, 1966, the day before appellant was to be tried in

the Circuit Court on the §1142 charge, appellant filed a

petition for removal in the United States District Court

for the Northern District of Alabama. In his removal peti

tion, appellant alleged that his arrest and prosecution were

being maintained “ for the sole purpose and effect of har

assing [him] and of punishing him for, and deterring him

and Negro citizens of the City of Birmingham from, exer

2 The relevant paragraph provides: “ It shall be unlawful for

any person or any number of persons to so stand, loiter or walk

upon any street or sidewalk in the city as to obstruct free passage

over, on or along said street or sidewalk. It shall also be unlawful

for any person to stand or loiter upon any street or sidewalk of

the city after having been requested by any police officer to move

on.”

f “ It shall be unlawful for any person to refuse or fail to comply

with any lawful order, signal or direction of a police officer.”

3

cising their constitutionally protected rights to equal pro

tection of the laws and their constitutionally protected

rights of free expression to protest racial discrimination,

which the City of Birmingham and the State of Alabama

now maintain by statute, ordinance, custom and usage” (R.

7-8, 242-43). On January 28, 1966, the district court en

tered a remand order (R. 244), from which this appeal

wTas timely taken (R. 248).

Appellant appended to his removal petition the record

in the Supreme Court of the United States. Taken most

favorably to the prosecution, the evidence in the record

is as follows. On April 4, 1962, at about 10:30 a.m., patrol

man Byars of the Birmingham Police Department observed

appellant standing on the sidewalk with 10 or 12 com

panions outside a department store at the intersection of

Second Avenue and Nineteenth Street in the City of Bir

mingham (R. 31). They were conversing among themselves

and occupied no more than one half of the sidewalk (R, 33,

40). After observing the group for a minute or so, notwith

standing there was no disorder or deliberate obstruction of

pedestrian traffic, Patrolman Byars walked up and told

them that they would have to move on (R. 34). After the

first command by the patrolman, the group commenced to

move away (R. 34). Byars repeated his command and ap

pellant asked, “ You mean to say wrn can’t stand here on the

sidewalk?” (R. 34). By this time everyone in the group

but appellant had begun to walk away, and patrolman

Byars told him that he was under arrest (R. 34, 50). Ap

pellant responded, “Well, I will go into the store” and

walked into the adjacent department store (R. 35). The

officer followed and arrested him (R. 35). The entire inci

dent, from the arrival of appellant and his companions

4

at the corner to Ms arrest, took less than four and one

half minutes (R. 56).

Specification of Error

The district court erred in remanding appellant’s prose

cution to the state court upon a record that, without the

necessity of an evidentiary hearing, revealed that appel

lant’s prosecution was racially motivated.

A R G U M E N T

Appellant’ s Prosecution Is Removable to Federal

Court Pursuant to 2 8 U. S. C. § 1 4 4 3 (1 ) Because the

Unconstitutional Nature of the Prosecution May Be

Established Without an Evidentiary Hearing.

In remanding appellant’s prosecution to the state court,

the court below held that the case was “ probably” 4 con

trolled by City of Greenwood v. Peacock, 384 U. S. 808

(1966). Appellant argues to the contrary.

In this case, the clear prediction that appellant’s state

trial will deny his federal constitutional and statutory

rights to equal protection of the laws (U. S. Const., Amend.

X IV ; 42 U. S. C. §1981 (1964)), may be established with

out a federal evidentiary hearing. Appellant has already

4 “Differing from the petition in Peacock, the removal petition

here has attached to it and made a part thereof a copy of the

record on certiorari to the United States Supreme Court. While

this record shows a conflict in the evidence, that presented by the

City is at variance from the conclusions of the removal petition

above quoted. It is, therefore, probable that this difference would

remove this case from the doctrine of Peacock as delineated in the

opinion of the Circuit Court of Appeals” (E. 243).

5

been tried once in the state courts.5 A full evidentiary rec

ord made at that trial was appended to his petition for

removal, and the removal petition alleged, and the record

shows, that on these facts, “ there is here no possible basis

for a conviction which would be valid under the Federal

Constitution” (Mr. Justice Fortas, concurring, in Shuttles

worth v. City of Birmingham, 382 U. S. 87, 100 (1965).

This was the view of the record taken by the Chief Justice

and by Justices Fortas and Douglas when the Supreme

Court reversed appellant’s conviction on the present charge;

a majority of the Supreme Court found it unnecessary to

reach that ground but did not disavow it. It could hardly

have disavowed it. The record is clear that: 1) at the time

of appellant’s arrest, his companions had dispersed; 2) ap

pellant was incapable of blocking the sidewalk by himself .

Officer Byars testified (R. 50):

Q. Well, all had moved by the time you made the

arrest? A. Except Shuttlesworth.

Q. Nobody was standing there but Shuttlesworth?

A. Nobody was standing; everybody else was in motion

except defendant Shuttlesworth, who had never moved

(R. 50).

Officer Hallman testified (R. 99-100):

Q. What happened to the group then, if anything?

A. All of them dispersed except Shuttlesworth.

5 Appellant’s removal petition was filed “before trial” within

the meaning of 28 U. S. C. §1446 (c). The petition was filed on

May 17, 1966 (R. 1), before appellant’s scheduled trial in the state

court on May 18, 1966 (R. 6). Timeliness of removal petitions has

never been held to turn on whether the removed proceeding is a

trial or retrial (Bush v. Kentucky, 107 U. S. 110, 111-12 (1883) ;

Kentucky v. Powers, 139 Fed. 452 (E. D. Ky. 1905)).

6

Q. What happened after that? A. Officer Byars

told him he was under arrest for blocking the sidewalk

and placed him under arrest.

Appellant was and is no stranger to the police6 and

courts7 of Birmingham. On this record, the conclusion is

inescapable that his prosecution was and is being pursued

by the City of Birmingham without any legitimate or real

prospect of success, but merely for the purpose of subject

ing appellant to the continuing harassment of this long-

protracted criminal litigation. Such harassment violates

appellant’s federal constitutional and statutory guaran

tees of equal protection of the laws,8 and—as it can be

established under “pervasive and explicit” federal princi

ples of law without evidentiary hearing, see Peacock, 384

U. S. at 832—it amply supports appellant’s claim to re

moval.

Appellant’s case is not controlled by Peacock. In that case

the Supreme Court did “ not necessarily approve or adopt

all the language and all the reasoning of every one of this

Court’s opinions construing this removal statute, from

Strauder v. West Virginia, 100 U. S. 303, to Kentucky v.

Powers, 201 U. S. 1.” 384 U. S. at 831. In other words,

civil rights removal is not limited by Peacock to eases in

6 Officer Byars had heard of appellant, had seen his picture on

television, had read that he had frequently been arrested and that

he had been in a Birmingham jail (B. 41-42). Shuttlesworth’s

arrest came during a recess in a well publicized federal civil rights

court proceeding in which he was involved.

7 See, Shuttlesworth v. City of Birmingham, 368 U. S. 959

(1962) ; In re Shuttlesworth, 369 U. S. 35 (1962) ; Shuttlesworth

v. City of Birmingham, 373 U. S. 262 (1963) ■ Shuttlesworth v.

City of Birmingham, 376 U. S. 339 (1964).

8 Dombrowski v. Pfister, 380 D. S. 479, 490 (1965).

7

which it had been allowed under the Strauder-Powers opin

ions—that is, cases in which a facially unconstitutional state

statute was implicated in the litigation. Rachel v. Georgia,

384 U. S. 780 (1966), indeed, permits removal in the absence

of such a statute.

The test of removal stated in Peacock is whether “ it

can be clearly predicted by reason of the operation of a per

vasive and explicit state or federal law that [federal civil

rights] . . . will inevitably be denied by the very act of

bringing the defendant to trial in the state court.” 384

U. S. at 828. The reason for the adoption of this strict

standard is clearly stated: the undesirability of a con

struction of §1443 under which “ every criminal case in

every court of every State . . . would be removable to a

federal court upon a petition alleging (1) that the defen

dant was being prosecuted because of his race and that

he was completely innocent of the charge brought against

him, or (2) that he would be unable to obtain a fair trial

in the state court. On motion to remand, the federal court

would be required in every case to hold a hearing which

would amount to at least a preliminary trial of the motiva

tions of the state officers who arrested and charged the

defendant, of the quality of the state court or judge before

whom the charges were filed, and of the defendant’s in

nocence or guilt.” Id. at 832. This reasoning does not

lead to the conclusion, and the Court does not hold, that

removal under §1443 is disallowed in cases where it can

be “ clearly predicted” without the kind of evidentiary hear

ing that Peacock feared would swamp and embarrass the

federal judiciary, that “by reason of the operation of a

pervasive and explicit state or federal law,” a state criminal

defendant’s federal civil rights would be destroyed “by the

very act of bringing the defendant to trial in the state

8

courts.” It is plain, as we have shown above, that this

“ clear prediction” need not be based on the facial assail-

ability of a state statute, and nothing in Peacock suggests

that the specific factual situation of Rachel is the only ex

ception to that basis.

On this record, “ there is nothing in the facts which jus

tified an arrest and conviction” (opinion of Mr. .Justice

Fortas, 382 U. S. at 101). Since that is ample basis for a

clear prediction that appellant’s civil rights are being ir

remediably denied by the continuation of his prosecution,

the exercise of federal removal jurisdiction is plainly

necessary and proper.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, the order of the District Court

remanding appellant’s case should be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

P eter A. Hall

Orzell B illingsley

1630 Fourth Avenue North

Birmingham, Alabama 35203

Jack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit, III

Norman C. A maker

Melvyn Zarr

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

A nthony G. A msterdam

3400 Chestnut Street

Philadelphia, Pa. 19104

Attorneys for Appellant

9

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

I hereby certify that on January 13, 1967,1 served copies

of the foregoing Brief for Appellant upon the following

attorneys for appellee, by United States air mail, postage

prepaid:

H on. E arl McBee

H on. W illiam C. W alker

Assistant City Attorneys

City Hall

Birmingham, Alabama

Attorney for Appellant

asms* 38