Case Involving Suit for Damages for Violation of Racial Restrictive Covenant on Real Property

Press Release

April 28, 1953

Cite this item

-

Press Releases, Loose Pages. Case Involving Suit for Damages for Violation of Racial Restrictive Covenant on Real Property, 1953. 8119b2b9-bb92-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c1a430a7-16ac-4ac2-869c-f5061bec995d/case-involving-suit-for-damages-for-violation-of-racial-restrictive-covenant-on-real-property. Accessed February 24, 2026.

Copied!

> < * r }

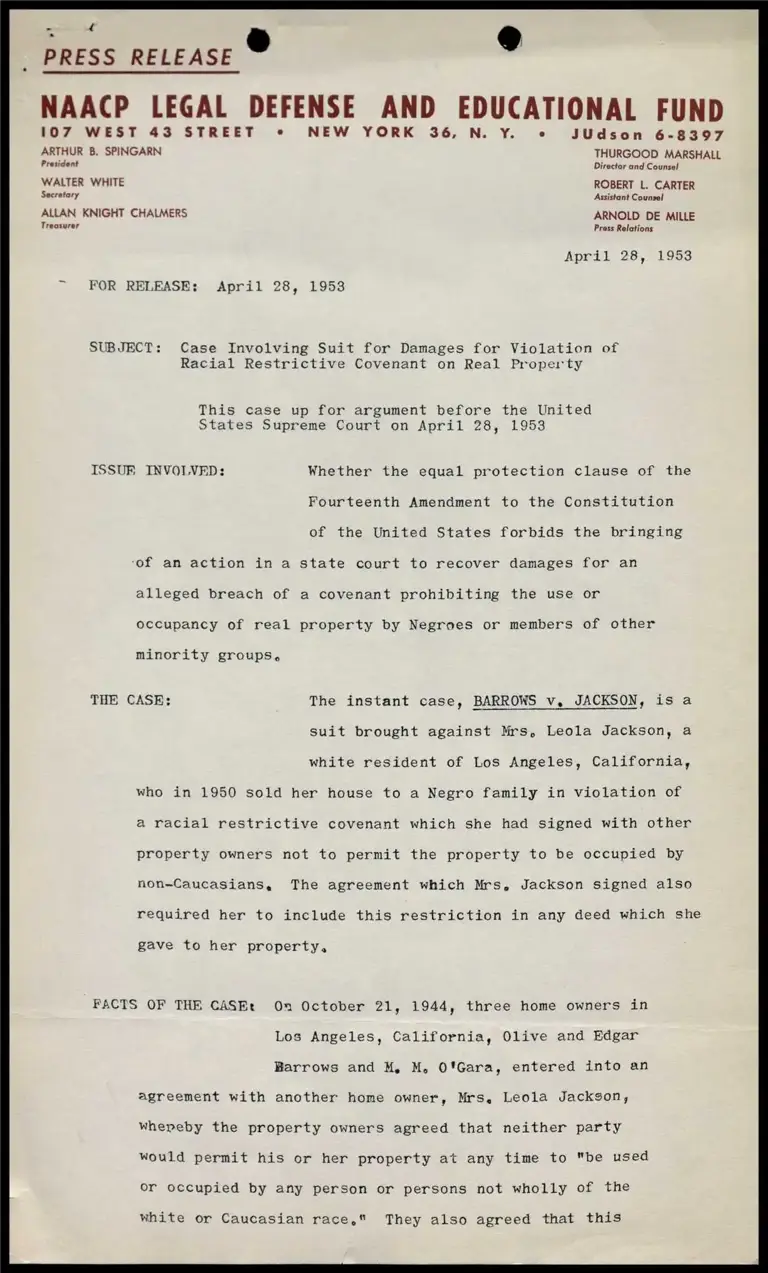

PRESS RELEASE

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND

107 WEST 43 STREET * NEW YORK 36, N. Y. © JUdson 6-8397

ARTHUR B. SPINGARN THURGOOD MARSHALL

President Director and Counsel

WALTER WHITE ROBERT L. CARTER

Secretary Assistant Counsel

ALLAN KNIGHT CHALMERS ARNOLD DE MILLE

Treosurer Pross Relations

April 28, 1953

~ FOR RELEASE: April 28, 1953

SUBJECT: Case Involving Suit for Damages for Violation of

Racial Restrictive Covenant on Real Property

This case up for argument before the United

States Supreme Court on April 28, 1953

ISSUR INVOIVED: Whether the equal protection clause of the

Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution

of the United States forbids the bringing

of an action in a state court to recover damages for an

alleged breach of a covenant prohibiting the use or

occupancy of real property by Negroes or members of other

minority groups,

THE CASE: The instant case, BARROWS v. JACKSON, is a

suit brought against Mrs, Leola Jackson, a

white resident of Los Angeles, California,

who in 1950 sold her house to a Negro family in violation of

a racial restrictive covenant which she had signed with other

property owners not to permit the property to be occupied by

non-Caucasians, The agreement which Mrs, Jackson signed also

required her to include this restriction in any deed which she

gave to her property,

FACTS OF THE CASEt On October 21, 1944, three home owners in

Los Angeles, California, Olive and Edgar

Barrows and M, M. O'Gara, entered into an

agreement with another home owner, Mrs, Leola Jackgon,

whepeby the property owners agreed that neither party

would permit his or her property at any time to "be used

or occupied by any person or persons not wholly of the

white or Caucasian race," They also agreed that this

Legal Defense and Educational Fund—--April 28, 1953 Page 2

racial restriction would be included in “all papers and

transfers,"

The agreement further provided that if

any of the lots should be used or occupied by persons not

wholly of the white or Caucasian race, the signor of the

agreement who permitted his or her property to be so oc-~

cupied in violation of the agreement, and his or her suc-

cessors, would immediately become -liable to “the other

signors and their successors whose lots were not so oc-

cupied for all damages which they may have suffered by

reason of the breach." This agreement was recorded on

the 8th of May, 1945,

On February 2, 1950, Leola Jackson, in

violation of the agreement, sold her property to Pearnell

and Florine Smally, non-Caucasians, and in September, 1950,

the Smallys began to occupy the property. In 1951, the

Barrows, Richard Pikaar, a successor in title to a signor,

and O'Gara filed suit in the Superior Court of Los Angeles

County to recover $3,000 damages each which they claimed

they had suffered as a result of the sale of the property

by Mrs, Jackson to the Smallys,.

Mrs. Jackson's attaneys argued that the

United States Supreme Court had held in the 1948 restrictive

covenant cases that a state court could not issue an injunc-

tion against the breach of such racial restrictive covenants

as such action on the part of a state court violated the

Fourteenth Amendment, Therefore, the Superior Court of

California could not award damages to the Barrows, Pikaar

and O'Gara in view of such decision as such an award of

damages is also prohibited by the Fourteenth Amendment to

the Federal Constitution,

On March 26, 1951, Judge Daniel N. Stevens

oe ® @

Legal Defense and Educational Fund-~-April 28, 1953 Page 3

2 qe

rendered a decision agreeing with Mrs, Jackson's attorneys

and dismissed the suit. The Barrows, Pikaar and 0'Gara

then appealed to the District Court of Appeals, Second

Appellate District of California,

The three judges sitting in the District

Court of Appeals, in a lengthy decision by Associate Judge

Paul Vallee, concurred in by Presiding Judge Clement Shinn

and Associate Judge Parker Wood, reviewed all of the cases

decided by the United States Supreme Court, and other courts,

involving state enforcement of racial restrictive covenants

and suits for damages for alleged breach of such covenants,

Theyconcluded that the decisions of the United States

Supreme Court in 1948 prohibiting the injunction for breach

of restrictive covenants, precluded the bringing of an

action for damages for breach of such covenants,

Following this decision, the Barrows,

Pikaar and O'Gara appealed to the Supreme Court of the State

of California which refused to review the case, The decision

of the District Court of Appeals was therefore affirmed,

The Barrows, Pikaar and O'Gara then petitioned the United

States Supreme Court to review their case, and on March 9,

1953, the highest court agreed to hear it.

ARGUMENTS: I, Petitioners--They argue that;

A, They are entitled to recover damages

from Mrs, Jackson because she violated her agreement by not

including the racial restrictive agreement in the deed

which she gave to the Smallys and by permitting the property

to be occupied by the Smallys, who are"non-Caucasians,"

B, The United States Supreme Court decision

in Shelley v, Kraemer, and other restrictive covenant cases

Legal Defense and Educational Fund-~-~April 28, 1953 Page 4

in 1948, does not prevent them from bringing action for

damages for breach of racial restrictive covenants,

C, If the United States Supreme Court

should. agree with the California courts, they would be

denied rights secured to them by the Fourteenth Amendment,

D, The public policy of the State of

California does not prevent the bringing of an action for

damages for breach of restrictive covenants,

II, Respondents--NAACP Legal Defense attorneys for

Leola Jackson argue that:

A. The United States Supreme Court

decisions in 1948 in the restrictive covenant cases, which

withdrew from the state courts the power to issue an injunc-

tion against the sale of real property to a Negro in violation

of restrictive covenants, is the basis for the California

courts’ ruling that they are without power to order that damages

be paid to the Barrows, Pikaar and O'Gara by Mrs, Jackson

for breaching her agreement with them,

B,. If damages may be recovered for breach

of racial restrictive covenants, the United States Supreme

Court's decisions in 1948 will be nullified, Negroes, and

other minority groups, would be as effectively denied their

civil right to purchase a home in a more desirable residential

area as they were before the 1948 decisions, Residential

racial segregation devices would again receive the sanctions

of the state courts,

C. Ina suit for damages, the state court

is urged to penalize the seller, who sells in violation of

@ racial restrictive covenant by, in effect, nullifying the

sale through taking from the proceeds of the sale a portion

or all of the proceeds to be paid to the suing parties to

Legal Defense and Educational Fund -- April 28, 1953 Page 5

the covenant in the form of damages, The seller would,

therefore, refuse to sell his property to a Negro because

of the fear of having to pay damages, Thus, the seller

would be effectively denied the right to dispose of his

property to whomever he pleases, This would be in violation

of the due process clause of the Fourteenth Amendment,

OTHER RESTRICTIVE

COVENANT CASES: In 1948, the United States Supreme Court

reviewed four cases, Shelley v. Kraemer,

Sipes v. McGhee, Hurd v. Hodge and Urciolo v,

Hodge, involving suits for injunction to enjoin white sellers

who, in violation of agreements, had sought to sell their

properties to Negroes, The high court held that neither

the state courts nor the federal courts could issue an in-

junction in such cases enjoining the sale to a Negro because

by so doing the courts would be giving effect to racial

discrimination in violation of the Constitution, laws and

public policy of the United States.

The question whether a party who sold toa

Negro in violation of the covenant might be sued for damages

for breach of the covenant was not decided by the high court

in those cases. Therefore those who sought to maintain the

vitality of the racial restrictive covenants found it necessary

to resort to the courts for determination of this question.

The first such case involving this question

arose in the State of Missouri in 1949 in Weiss v. Leaon.

The highest court of that state held that damages, if proved,

might be recovered,

The next case arose in 1950 in the District

of Columbia. In Robert v. Curtis, the United States District

Court for the District of Columbia held that the United States

Legal Defense and Educational Fund -- April 28, 1953 Page 6

Supreme Court's decisions in 1948 were broad enough to

include suits for damages. Therefore, under those decisions,

the federal courts could not entertain a suit for damages,

The next case arose in 1950 in the State of

Michigan where the Circuit Court for Wayne County, in

Phillips v. Naff, ruled that in accordance with the United

States Supreme Court decision, in Shelley v. Kraemer in 1948,

suits for damages for breach of a reciprocal racial restrictive

covenant constituted an indirect method of enforcing racial

restrictive covenants.

The case which preceded the instant case,

which was decided in 1951 by the highest court of the State

of Oklahoma, was Correll v. Harley. In this case the court

held that damages may be recovered in tort for “willful,

malicious conspiracy" to injure another's property in

violation of the agreement,

There have also been several other cases

involving suits for injunction which were pending in state

courts in 1948 at the time that the United States Supreme

Court rendered its decisions in the four above-mentioned

cases. Subsequent to 1948, there have also been other state

court cases involving suit for injunction for breach of

racial restrictive covenants. In all of these cases, the

state courts have denied injunctions in accordance with the

decisions handed down by the United States Supreme Court.

IMPORTANCE OF THE

PRESENT DECISION: As indicated above, California, Michigan

and the District of Columbia have held

that suits for damages for breach of racial

restrictive covenants may not be maintained. Missouri and

Oklahoma have held the contrary. It is therefore important

Legal Defense and Educational Fund -- April 28, 1953 Page 7

that the United States Supreme Court resolve this conflict

by its decision in the present case in order that this

question may be finally settled.

If the United States Supreme Court should

affirm the California courts in this case, it will end all

racial restrictive covenants. However, should the high

court follow the holding in the Missouri case, the question

which then might arise would be: What damages can actually

be proved as flowing directly and solely from the moving in

of Negroes? In Buchanan v. Warley, the United States Supreme

Court said that property values may depreciate by the moving

in of undesirable white persons and from putting property

to perfectly lawful uses.

There is now scientific evidence which proves

that Negroes do not depreciate property by moving into certain

residential areas. This evidence has been published in

articles appearing in 1951 in the Appraisal Journal, a journal

of real estate appraisers, by Charles Abrams, the noted

authority on housing, and Dr. Luigi M. Laurenti of the University

of California. A similar study has been made by Belden Morgan

and published in The Review of the Society of Residential

Appraisers for March 1952.

ATTORNEYS: For Mrs. Leola Jackson--Loren Miller, NAACP

attorney of Los Angeles, California, who

successfully agrued Sipes_v. McGhee, one of

the 1948 restrictive covenant cases before the United States

Supreme Court, and several other cases arising in the State

of California. He is assisted by Thurgood Marshall, Director

and Counsel, N.A.A.C.P. Legal Defense & Educational Fund, of

New York; Franklin H, Williams, West Coast Regional representa-

tive. Assisting in preparing the brief were Maurice Walbert,

James Sims and Harold J. Sinclair of California.