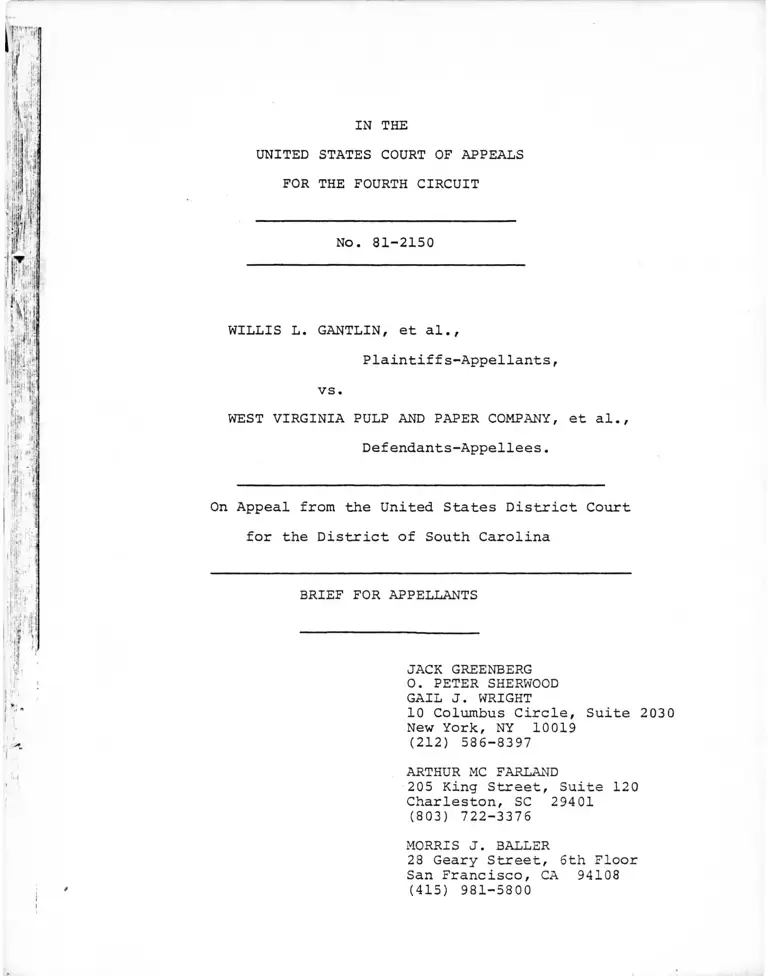

Gantlin v. West Virginia Pulp and Paper Company Brief for Appellants

Public Court Documents

November 10, 1982

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Gantlin v. West Virginia Pulp and Paper Company Brief for Appellants, 1982. 9254c0b5-b29a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c1fc91b3-e505-4e3f-83be-7ecc18b6364b/gantlin-v-west-virginia-pulp-and-paper-company-brief-for-appellants. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

NO. 81-2150

WILLIS L. GANTLIN, et al.,

Plaintiff s-Appellants,

vs.

WEST VIRGINIA PULP AND PAPER COMPANY, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the District of South Carolina

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

JACK GREENBERG

0. PETER SHERWOOD

GAIL J. WRIGHT

10 Columbus Circle, Suite 2030

New York, NY 10019

(212) 586-8397

ARTHUR MC FARLAND

205 King Street, Suite 120

Charleston, SC 29401

(803) 722-3376

MORRIS J. BALLER

28 Geary Street, 6th Floor

San Francisco, CA 94108

(415) 981-5800

INDEX

PAGE

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES..................................... ii

QUESTIONS PRESENTED................................ 1

STATEMENT OF THE CASE..........................

STATEMENT OF FACTS .................................. 5

A. Overview of Factual Issues....................... 5

B. The Mill and Its Segregated Departments

and Jobs...........................................

C. Segregated Unions and Union

Representation Units.............................

D. Segregated Seniority Structure.................. 13

E. "Merger" of Segregated Sequences and

Local Unions in May 1968 ...................... 15

F. Adoption of Mill Seniority System................. 25

G. Refusal to Implement Mill Seniority System . . 29

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT.................................... 41

ARGUMENT............................................. 4 2

The District Court Erred in Holding Defendants'

Seniority System Bona Fide....................... 42

A. The Seniority System Had Its Origin In

Discrimination......................... 44

B. The Seniority System Applied Unequally to

Blacks............................ 47

C. The Seniority System Was Maintained and

Manipulated With Intent To Discriminate. . . . 50

D. The Racially—Defined Dual Seniority System

Was Neither Rational Nor Consistent With

Legitimate Industrial Needs..................... 59

E. The Finding That The Seniority System Was

Not The Result Of An Intent To Discriminate

Is Clearly Erroneous................... 62

CONCLUSION.......................... 65

-i-

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases

Page

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405 (1975). . . . 64

American Tobacco Co. v. Patterson,

___U.S.___, 71 L . Ed . 2d 748 (1982)................... 42

Bigelow v. Virginia, 421 U.S. 809 (1975)............... 65

Chrapliwy v. Uniroyal Corp., F.Supp. ,

15 EPD 1| 7933 (N.D. Ind. 1977). . . .~7~ . . . . . 46,59

Chris-Craft Industries v. Piper Aircraft Corp.,

516 F . 2d 172 (2d Cir. 1975).......................... 65

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971)........... 42

Gulf Oil Corp. v. Bernard, 452 U.S. 89 (1981)...........4

International Brotherhood of Teamsters v.

United States, 431 U.S. 324 (1971)...........41,42,43,61

James v. Stockham Valves & Fittings Co.

559 F . 2d 310 (5th Cir. 1977)....................... 41,43

Johnson v. Ryder Truck Lines, Inc. 575 F.2d 471

(4th Cir. 1981), cert, denied 440 U.S. 979 (1979) . . 43

King v. Georgia Power Co., 634 F .2d 929

(5th Cir. 1981), vac'd and rem'd 72 L.Ed.2d 477 (1982) .45-46,

........ 49-50

Levin v. Mississippi River Corp., 386 U.S. 612. . . . 65

(1967)

Local 189, United Papermakers & Paperworkers v.

United States, 416 F .2d 980 (5th Cir. 1969),

cert, denied 397 U.S. 919 (1970)................... 25,61

Miller v. Continental Can Co., 46,50,61,

___F.Supp. ___, 26 FEP Cases 151 (S.D. Ga. 1981). . . 62

Myers v. Gilman Paper Co., F.Supp.

25 FEP Cases 468 (S.D. Ga. 1981).............47,50,61,62

li

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES (Cont'd)

Cases

Page

Patterson v. American Tobacco Co.,

634 F .2d 744 (4th Cir. en banc 1980),

rev'd 71 L.Ed.2d 748 (1982).............

Pullman-Standard, Inc. v. Swint, U.S.

72 L . Ed. 2d 66 (1982)........ “7“. .

Quarles v. Philip Morris, Inc., 279 F.Supp.

505 (E.D. Va. 1968).....................

Robinson v. Lorillard Corp., 444 F.2d 791

(4th Cir. 1971), cert, dismissed 404 U.S.

1006 (1971)..............................

Rogers v. Int'l Paper Co., 510 F2d 1340

(8th Cir. 1975), vac'd and remanded

423 U.S. 809 (1975).............

........ 43

.41,42,62,63

........ 25

25

. 61

Russell v. American Tobacco Co., F.Supp.

26 FEP Cases ___ (M.D. N.C. 198lJ. .

Sears v. Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Rwy. Co.,

645 F.2d 1365 (10th Cir. 1981), cert, denied

72 L.Ed.2d 479 (1981), aff'g in pert, part

454 F.Supp. 158 (D.Kan. 1979)...............

Stevenson v. Int'l Paper Co., 516 F.2d 103

(5th Cir. 1976)...............

Swint v. Pullman-Standard, Inc., 624 F.2d 525

(5th Cir. 1980), rev'd 72 L.Ed.2d 66 (1982). . . 11,43,64

Terrell v. United States Pipe & Foundry Co.,

644 F .2d 1112 (5th Cir. 1981), vac'd and rem' d

72 L . Ed. 2d 479 (1982)................................ 11,46

Trans World Airlines, Inc. v. Hardison,

432 U.S. 63 (1977)....................... 42

United States v. Hayes Int'l Corp.,

456 F .2d 112 (5th Cir. 1972) . . . 54

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES (Cont'd)

United States v. United States Gypsum Co.,

333 U.S. 364 (1948)................................ 64

United Steelworkers of America v. Weber,

443 U.S. 193 (1979)................................ H

Village of Arlington Heights v. Metropolitan

Housing Development Council, 429 U.S. 252 (1976). . 50,62

Watkins v. Scott Paper Co., 530 F .2d 1159

(5th Cir. 1976).................................... 59,61

Wattleton v. Ladish Co., 520 F.Supp. 1329

(E.D. Wis. 1981), aff'd sub nom Wattleton v.

Int'l Brotherhood of Boilermakers, etc.,

___F -2d___ (7th Cir. No. 81-2411, July 16 , 1982). . . . 62

Statutes and Rules

28 U.S.C. § 1291..................................... 5

42 U.S.C. §1981...................................... 3/43

42 U.S.C. §2000e et seg., Title VII................... passim

42 U.S.C. §2000e-2(h), Section 703(h)................1,5,42,65

Rule 23, F.R.C.P..................................... 3

Rule 52(a), F.R.C.P................................. 43,44,64

Other Authorities

Brooks, G., and S. Gamm, "The Practice of Seniority

in Soughern Paper Mills", Monthly Labor Review

(July 1955).............. ........................ 62

Jacobson, J., The Negro and the American Labor

Movement (1968) . 7 7 ! ] ! ! 7 ! ! ! ! ! ~ . . g2

Marshall, F. Ray, The Negro and Organized Labor

<1965) . . . . 7 .............! ............ .......... 62

Northrup, H., and R. Rowan, The Negro in the Paper

Industry (1968)........ 7 ! ! 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7~ # _ 62

Page

Cases

IV

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

No. 81-2150

Willis L. Gantlin, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,

vs.

West Virginia Pulp and Paper Company, et al.,

Defendants-Appellees.

Appeal from the United States District Court

for the District of South Carolina

BRIEF FOR APPELLANTS

QUESTION PRESENTED

Did the District Court erroneously determine that a

seniority system, whose divisions precisely traced the racial

allocation of job opportunities and whose discriminatory effects

were tenaciously maintained and defended for as long as possible,

was bona fide and therefore shielded by Section 703(h) of Title

VII?

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

This is a Title VII action challenging discriminatory

promotion practices, centering on defendants' seniority system,

as they have affected a class of black paper mill workers. The

-1-

2

case comes to this Court on appeal, eight years after trial,

from a decision of the District Court finding no actionable

discrimination of any sort.

Plaintiffs-Appellants Willis L. Gantlin, et al. (hereafter

"plaintiffs") are six black employees of defendant West Virginia

Pulp and Paper Co. (hereafter "Westvaco") at its paper mill

located in North Charleston, South Carolina (Op. 1). Five

plaintiffs were employed at the time of trial; one had been dis

charged before trial (Op. 1). All six were members of defendants

United Papermakers and Paperworkers International Union (hereafter

2

"UPIU," or as appropriate the "Paperworkers" or "Papermakers" )

and its Local Union No. 508 (hereafter "Local 508"; other defen

dant local unions are cited in similar form). Other unions which

represent employees at Westvaco's North Charleston mill were

also joined as defendants: UPIU Local 435, the International

Brotherhood of Electrical Workers ("IBEW") and its Local 1753,

and the International Association of Machinists ("IAM") and its

Lodge 183.

1 Citations in the form "Op. " are to pages of the

District Court's Order, Findings of Facts, and Con

clusions of Law entered October 19, 1981. Citations to the

trial transcript are by page number (e.g., "Tr. 302"), and the

witness may be identified by surname. Other citations are to

trial exhibits by party introducing them (e.g., "Pi. Ex. ")

or other record items as indicated.

2 UPIU was formed by merger of the United Papermakers

and Papers (UPP) and International Brotherhood of

Pulp and Sulphite Workers (IBPS) in 1972 (Stip. 1(3.)

3 IAM and Lodge 183 have been dismissed, with plain

tiffs' assent, as parties to this appeal (Order

entered August 13, 1982). All other defendants are appellees here.

3

Plaintiffs' complaint filed June 15, 1972, alleged a number

of discriminatory employment practices and claimed violations

of Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S. §§2000e

et seq., and 42 U.S.C. §1981 (Complaint). The complaint was

based on a series of EEOC and administrative agency charges

4

of discrimination, beginning on July 28, 1966, by which plain

tiffs fulfilled the prerequisites to suit under Title VII. See

5

Stipulation 1M| 35-43, Stip. Ex. 11-24. On behalf of a class

of present and past black Westvaco employees, the complaint sought

relief from discrimination in, inter alia, hiring and promotions,

and specifically complained of discriminatory operation of defen

dants' seniority system (Complaint). All parties took voluminous

discovery through written interrogatories and requests, document

inspections, and depositions.

On March 14, 1973, the District Court certified the case

as a class action under Rule 23, F.R.C.P., but narrowed the

scope of the class represented by plaintiffs to black workers

in "production and maintenance" jobs during the relevant time

period:

4 Other charges were filed by plaintiffs on August 4

and November 16, 1966, April 25, 1967, November 3,

1967, March 11, 1969, March 10, 1970 and July 6, 1971. The

District Court apparently treated the EEOC charge of April 25,

1967 (Stip. Ex. 14) as the first charge (Op. 55). However,

the July 28, 1966, letter from plaintiff Gantlin to the Presi

dent's Committee on Equal Employment Opportunity (Stip. Ex.

12) was properly treated by EEOC as a charge of discrimina

tion under Title VII, filed August 4, 1966 (PI. Ex. 1, 2).

5 This Stipulation is described in the text at p. 4,

infra.

4

■̂dl black persons employed in bargaining

unit jobs at Westvaco's North Charleston

Paper Mill between July 2, 1965 and March 14, 1973.

(Op. 2). Over 200 black employees, plus as many former employees,

are members of that class (Pi. Ex. 27(a), 27(b)).6

On the eve of trial, July 16, 1974, the parties entered into a

lengthy factual stipulation which included some 24 attached ex

hibits (Stip.). This stipulation traces, in broad outline, defen

dants basic seniority and employment practices, and plaintiffs'

complaints against them. Trial lasted from July 17, 1974, to

August 15, 1974, on "Stage I" issues of liability for class dis

crimination, the Court having bifurcated Stage II issues of indi

vidual monetary and other relief for later trial if necessary

(Op. 3). At the conclusion of trial, and at the Court's urging,

the parties agreed to defer preparation of post-trial briefs

until completion of the trial transcript, which was estimated

to require several months. The transcription was in fact only

completed some four years later, as a result of special arrange

ments made directly by this Court. Thereafter extensive and

6 Shortly after it had certified the class, the court

d as, ^mposed a '^ag rule" against communications witht mamb<frs and required class members to "opt in" by filina a

border June 7 assistance of c o u L e l ^ o r ^ e ^ L sl raers or June /, 1973)-, These actions, which appear to be

rC,* 1®arn^ ? ® ® ° f discretion, see Gulf Oil Corp. v. Bernard. 452

U.S. 89 (1981), are not directly before~he Court at this time.

ter.rePeated and unsuccessful efforts to get the

cr-ini- nr- C°Urt to assure completion of the transcript or to decide the case without a transcript, and after

o urgent appeals to the Chief Judge of this Court, the

^ r ^ Ptl°n ™ teS and tapes were removed to Richmond and there transcribed. See letters of Jack Greenberg to Hon

i3 7 ^ YnSWOrth' Jr-' APril 9, 1976, October 25, 1976,

5

detailed briefs were filed by the parties, and after a day of

post-trial argument on July 17, 1980, the District Court entered

its decision, rejecting every one of plaintiffs' claims, fifteen

months later.

Judgment was entered below on November 2, 1981 (R. ).

Plaintiffs filed their Notice of Appeal on November 13, 1981

(R. ). This Court has jurisdiction under 28 U.S.C. §1291.

In this appeal, plaintiffs focus on their principal claim: that

defendants' "lock-in" seniority system discriminatorily inhibited

class members' advancement from 1965 to the date of trial, and

that the seniority system, being the instrument of intentional

discrimination, is not bona fide within the meaning of §703(h)

8

of Title VII, 42 U.S.C. §2000e-2(h).

STATEMENT OF FACTS

A. Overview of Factual Issues.

From the mill's beginning, every aspect of work at Westvaco

was totally segregated by race, and this complete racial separa

tion continued until at least 1964. As the parties stipulated,

all jobs, promotional lines, seniority units, and local unions

were either for whites only or for blacks only during this pre-

Title VII period. See Stip. 111(5-7, Stip. Ex. 1 and 2 (Op. 70-

97), 3. Although defendants made some changes in hiring practices

8 A second claim, which plaintiffs had intended to fully

brief and argue — that the District Court erred in

finding no discrimination in hiring and initial assignment to

production jobs in the period 1964-May 1968 — has been elimi

nated in order to bring this brief within the 65 page limit

ordered by this Court. It remains our position, nevertheless,

that such hiring discrimination continued during that period.

^ e ' Rost-Trial Brief for Plaintiffs, filed February 2 , 1979 , pp

17-33, 104-111; Post-Trial Reply Brief for Plaintiffs, filed

November 27, 1979 , pp . 40-43; and see, pp. 51-53, infra.

6

beginning in 1964, and some changes in seniority units and

seniority practices beginning in 1968, plaintiffs contend that

those hiring changes were cosmetic and insignificant, and that

class members continued to be assigned to black jobs on a racial

basis. Plaintiffs further contend that the seniority system in

effect before 1968 was intentionally designed and manipulated to

keep black workers in their inferior places both before and

after the initiation of changes in the strictly segregated

seniority structure.

B. The Mill and Its Segregated Departments and Jobs.

Westvaco's North Charleston mill produces kraft paper from

wood and wood chips through chemical pulping and mechanical roll

ing and finishing, and chemical by-products of the pulping pro

cess (Stip. 114). At the time of trial, Westvaco employed 1,049

unionized, hourly-paid employees in production and maintenance

jobs at the mill, of whom 827 (79%) were white and 222 (21%)

were black (Op. 5). In addition, several hundred salaried

employees worked at the mill as foremen and supervisors, mana

gers, professional and technical workers, clerical workers,

guards, and the like; these employees' jobs were excluded from

the scope of the lawsuit before trial by the Court's class

action determination (Stip. p. 3; Order of March 14, 1973).

Westvaco's production and maintenance employees were

9 10

organized into 14 departments , of which two were no longer

9 Woodyard Service, Woodyard Operating, Pulp Mill, Recovery,

Paper Mill, Technical Services, Water Treatment, Finish

ing and Shipping, Converting, Power, Tall Oil, Polychemicals,

Receiving and Stores, and Maintenance. See Op. 4-5, Stip., pp. 2-3.

10 Water Treatment and Converting.

7

staffed or operating by time of trial. The large maintenance

department, containing approximately 350 jobs, is responsible

11

for repair and maintenance of plant and equipment (Op. 5).

The Woodyard Operating and Pulp Mill departments prepare pulp

for rolling into kraft paper (Op. 4). The Paper Mill and Finish-

« ing and Shipping departments produce and package the paper in

r°ll form (Op. 4—5). The Recovery, Tall Oil, and Polychemicals

departments recover and process chemical by-products (Op. 4-5).

The Woodyard Service (mill-wide), Technical Service, Receiving

and Stores, and Power departments perform ancillary functions

as indicated by their names and described in the parties' Stipu

lation (Op. 4-5). Jobs in the eleven primary production depart

ments are grouped into one or more "sequences" or promotional

ladders of functionally related positions (Op. 5).

Three different unions represented workers in Maintenance

department positions — Machinists Lodge 183 (machinists and

oilers), Electrical Workers Local 1753 (electricians), Pulp

Sulphite Workers Local 508 (other craftworkers) (Stip. 115) .

All these positions were staffed by whites only (Stip. p. 5).

All production workers' positions were governed by a single

joint bargaining unit including members of Local 508, Local

435 and the former black Local 620 (Stip. pp. 6-7). Local

508's jurisdiction included the white workers in the pulp,

chemical recovery, and plant service operations; Local 435

11 Jobs in the Maintenance Department are grouped by

crafts (e.g., Carpenter, Machinist, etc.) and skill

levels within many of the crafts (e.g., apprentice and jour

neyman) (Stip. 1MI28-29).

8

included the white workers in the papermaking and finishing

areas; and Local 620 included all black workers, who were laborers

or held menial positions in all departments (Stip. p. 4, Stip.

Ex. 2; see pp. 11-12,infra). Local 1753 represented white produc

tion workers in a single sequence in the Power department (Stip.

P. 4) .

In six of the production departments — Woodyard Operating,

Recovery, Finishing and Shipping, Receiving and Stores, Tall Oil,

and Polychemicals — there were two separate sequences, one rep

resented by Local 620 and staffed by black employees, the other

represented by Local 508 or Local 435 and staffed by white

employees (Stip. pp. 4-5; Stip. Ex. 2 & 3). These departments

were the principal focus of the evidence at trial. The other

departments — Pulp Mill, Paper Mill, Technical Services, and

Power — had only white sequences represented by Local 508 or

Local 435 with a single black laborer/janitor job, represented

by Local 620, attached to the department but not to the sequences

(Op. 70-83, Stip. pp. 24-25).

Black jobs and sequences were not only separate from white

sequences, but also inferior. With very few exceptions, all

white jobs, including the lowest, paid higher wages and offered

greater opportunities for advancement than even the highest black

position. In terms of May 1968 pay rates, the only black (Local

620) jobs in the Paper Mill, Pulp Mill, Technical Services, and

Power departments carried the laborer's base pay rate of $2,535/

hr., equal to the lowest wage in the mill. In the Woodyard Ser

vice, Finishing and Shipping, Receiving and Stores, Recovery,

9

Polychemicals and Tall Oil departments the maximum black job

pay rate ranged only slightly higher, between $2.58 and $2.80/hrc,

Only in the Long Wood operation of the Woodyard — not a tradi

tional black sequence but a recently-created position assigned

to Local 620 — did a position held by blacks pay as much as

$3.15/hr. In contrast, the pay scale for traditionally white

jobs in the Local 435 and Local 508 sequences was substantially

higher, ranging from a minimum entry level in the range of

12 13

$2.645-$2.79 to maximum wages in the range $3.24-$4.09.

Salaried positions were for whites only. Not a single one of

Westvaco's 19 managers and officials, 280 professional and techni

cal personnel, or 88 clerical staff employed in 1963 was black

(PI. Ex. 33, p. 2). By 1972, Westvaco had employed only one

14

black person — as foreman of janitors — out of about 100

line supervisors (Pi. Ex. 14, 14a, No. 65; Pi. Ex. 9, p. 189,

Tr. 420—22, 424, Hendricks). Likewise, all 571 maintenance

craft workers in 1963 were white (Pi. Ex. 33, p. 2; Tr. 1833-34,

Allison).

The inferiority of the black jobs is reflected in gross pay

disparities between black and white workers, analyzed in a

detailed series of exhibits (PI. Ex. 68-77). Overall, white

workers' incomes were 25 percent higher than blacks' in the

12 Laborer-type jobs in the Paper Mill and Finishing and

Shipping_departments paid slightly less. These jobs

were not actually in the lines of progression.

13 Source of these wage comparisons: Stip. Ex. 2.

14 When this individual was promoted to foreman in 1966,

he had been at the mill 25 years, mostly as a janitor.

PI. Ex. 14 (a), #65.

10

period 1965-1972, or about $1900/year higher (Pi. Ex. 69, p. 3,

Pi. Ex. 70, p. 3; Tr. 2069, Mador). Even restricting the com

parison to production workers only, and controlling for years

of seniority, the same degree of income disparity is present

among workers hired before 1966 (PI. Ex. 73). Similar dispari

ties were consistently present in each department (PI. Ex. 74).

The racial segregation of unions, sequences, and jobs at

the mill remained absolute until at least December 1963 (Stip.

pp. 4-5, 8). All other aspects of the mill were also strictly

segregated. Personal facilities such as restrooms, shower and

locker rooms, and cafeteria were physically separate and sepa-

15

rately used by the two races until at least 1969.

C. Segregated Unions and Union Representation Units.

The defendant unions are lineal descendants of unions which

organized Westvaco's production and maintenance employees soon

after the mill opened in 1937. In that year IBEW and the prede

cessor of Local 1735 became the bargaining agent for the plant's

electricians (Op. 6). The remaining unions organized their bar

gaining units by joint agreement in 1944 — the UPP and its Local

435 shared with IBPS and its Local 508 representation of a single

bargaining unit consisting of white mill production workers in

all-white jobs,_while IAM and its Lodge 183 obtained bargaining

15 These segregated facilities were merged only after

the EEOC noted their existence and found a Title VII

violation in its May 7, 1969 decision (Pi. Ex. 3, pp. 2-3; Tr.

1496, 1499, Gantlin; Tr. 1281, Jenkins). One final segregated

"amenity" — Westvaco's recreational "Athletic Association" —

was never desegregated and Westvaco was orderd by OFCC to sever

its ties with this all-white "club" in July 1970 (PI. Ex. 9, pp.

195-96; PI. Ex. 85, Co. Ex. 98(b)).

11

rights for a unit of machinists (id.). At first black employees

were left outside the union structure, but later in 1944 IBPS

chartered a separate Local 508-A to represent blacks in unskilled

jobs (id.). Local 508-A then entered the joint bargaining unit

of Locals 435 and 508. Because there was no contest over union

recognition or bargaining units, there is no official record of

union or job structure at that time, such as exists in cases

involving intra-union disputes resolved before the National

16

Labor Relations Board. Except for changes in the number of two

locals, this union representation structure remained unchanged

until 1968.

Each of the locals was strictly segregated. The Machinists

and Electricians excluded blacks until the late 1960s or early

17

1970s by union constitution or convention as well as by local

practice at Westvaco (Stip. 119). The two paper mill internationals,

UPP and IBPS, did not charter racially integrated locals anywhere

until at least the 1960s (PI. Ex. 8, pp. 104-12, Dunaway).

Where either one represented black workers, they were segregated

in an all-black local.

These traditions of segregation were respected at Westvaco

(PI. Ex. 14(a), No. 14). Local 508-A became Local 620 and at

all times had only black members (PI. Ex. 9, pp. 12-13; Pi. Ex.

16 See, for example, Swint v. Pullman-Standard Co.,

624 F.2d 525 (5th Cir. 1980), reversed 72 L.Ed.2d

66 (1982); and Terrell v. United States Pipe & Foundry Co.,

644̂ F. 2d 1112 (5th Cir. 1981) , vac'd and rem'd sub nom. Int'l

Ass n of Machinists v. Terrell, 72 L.Ed. 2d 479 (1982) ----

17 Terrell_v. united States Pipe & Foundry Co., supra,

644 F.2d at 1119; United Steelworkers of America v.

Weber, 443 U.S. 193, 198 n. 1 (1979) .------- ------------------

12

7, p. 14). Its "brother" locals, 435 and 508, had white members

only (PI. Ex. 7, p. 14; Tr. 3102). Even when in the mid-1960s

a few blacks began to enter previously all-white jobs in the

white union jurisdictions, and a few whites appeared in jobs

within Local 620's jurisdiction, the locals themselves remained

segregated; apparently those few whites' and blacks' union

affiliation was determined by their race rather than, as for

other employees, their job (Stip. 1f9; Tr. 1565, 3440).

At all times until 1968, divisions of Westvaco positions

within the scope of the joint (IBPS-UPP) bargaining unit between

black Local 620 and white Locals 435 and 508 precisely traced

Westvaco's original segregated job structure. Local 620 repre

sented only those jobs or sequences which were staffed with

black workers. Locals 435 and 508 represented all other jobs,

18

from which blacks had been excluded. Moreover, the hand of

racial segregation did not trace racial lines only between depart

ments. It divided single departments and even functionally

integrated job groups between white and black unions' jurisdic

tions, according to the jobholders' race. Thus, the Woodyard

Operating Department contained two sequences in Local 508's

jurisdiction and two in Local 620's (Op. 70; Stip. Ex. 2). In

Recovery blacks in the three bottom jobs, included in Local

620's jurisdiction, assisted whites in operator positions

18 The only minor exception came in the Woodyard, with

the creation in 1964 of short new progressions in

the Long Wood (620) and Scaler (508) operations (Stip. 1116).

Although the District Court made detailed findings about the

organization and bargaining jurisdiction of the unions, it

failed to mention the undisputed fact that they corresponded

precisely to the segregated job structure. See Op. 5-7.

13

included in Local 508 territory. In the Pulp Mill, Paper Mill,

Technical Service, and Power Departments, black janitors and

laborers in Local 620 jobs assisted and cleaned up after whites

represented by Local 508, Local 435, or Local 1753 (Op. 74-75,

78-79; Stip. Ex. 2). In Finishing and Shipping whites in the

lower portion of the 435 sequence worked closely with blacks

in a separate 620 line (Op. 76; Stip. Ex. 2). Polychemicals,

Tall Oil, and Receiving and Stores all contained truncated black

sequences within Local 620's jurisdiction, along with longer

sequences of Local 508 jobs held by whites (Op. 80-82; Stip. Ex.

2). In every department, union representation reflected not

the close physical or functional proximity of white and black

workers, but the prevalent system of dividing even small units

into their racially defined component parts.

D. Segregated Seniority Structure

Seniority units at Westvaco prior to May 1968 coincided

precisely with the segregated structure of jobs and local

unions. Production and maintenance positions were arranged in

patterns that built in promotional opportunities which care

fully observed the traditional barriers between whites and

blacks, and seniority was the currency of those promotional

19

opportunities.

19 Maintenance craft positions, not involved in this

appeal (see p. 7 , supra), did not observe

seniority-based promotions in the true sense. Rather, helpers

or apprentices progressed to journeymen in their particular

trade as they attained necessary skill levels. Although plain

tiffs do not here challenge Westvaco's hiring for maintenance

craft positions, we note that there were no blacks employed as

apprentices, the gateway to journeyman positions in the high-

skilled ̂ crafts , until shortly after the May 1968 mergers in

production job areas.

14

Almost all production positions were linked to promotional

ladders — lines of progression or "sequences" — leading to

other positions. Thus, typically, a new production employee

entered some part of the plant at a low—skill, entry—level

position, and then promoted up the ladder or sequence to which

that job gave entry according to seniority at each job step and

to qualifications. Since qualifications were judged only on a

Pass-fail" basis, job seniority was the governing factor in

determining which one among at least minimally qualified employees

was promoted to a higher job in the sequence (Stip. 1(20) .

Temporary promotions or "push-ups", which gave valuable oppor

tunity for training and qualification in higher level jobs, were

. 20 also governed by job seniority within the progression. Some

of the entry jobs were "pool" positions whose occupants usually

worked in various locations around the mill and who could then

promote according to seniority into any of several sequences at

its entry point (Stip. 1(19).

Both the progressions and the pools were segregated by

race. The job seniority rights acquired by whites in white jobs

in white sequences were applicable to promotion to higher jobs

in the same sequences (Stip. 1(20). Likewise, job seniority

acquired by black workers in black sequences led only to oppor

tunities for promotion within the segregated sequence (id.).

20 When promotions are of short duration, they are

filled by an employee from the same shift. For

longer-term push-ups, a job-senior employee may exercise his

job seniority rights on another shift. (Stip. 1(21) . Such

long-term or "regular" push-ups are both common and important

for the reasons stated in the accompanying text.

15

In reductions-m-force,job seniority within a sequence was also

the governing factor (Stip. 1(23). Job seniority did not apply

to promotions from one sequence to another; such moves were con

sidered transfers. Transfers were allowed only to the bottom or

entry level of another sequence, at the discretion of management,

and without the carry-over of accumulated job seniority (Stip. pp

16-17). Thus, the transferee would start in the new sequence

as a new employee, insofar as promotion and demotion within that

sequence is concerned (id.). In contrast to the hazards atten

dant on transfer between sequences, promotions within a sequence

are automatic, assuming adequate qualifications. The employee

with most job seniority in the job in sequence below the vacant

position is given the promotion unless he declines or "waives"

it (Stip. 1(22).

The restrictive effect of this seniority system on black

workers is best illustrated by examining the seniority situation

of a black employee in one of the segregated sequences — for

example, the Recovery sequence (see Op. 72). A black employee

in the position of First Service Operator, the top job of

the black sequence of jobs represented by Local 620, was not

routinely considered for promotion to the position of Utility

Man in the white sequence represented by Local 508 — even

though the duties of the jobs were functionally related and

even though the Utility Man position paid slightly more than the

First Service Operator (Stip. Ex. 2). Rather, the black employee,

who necessarily had substantial job security as a First Service

Operator, had a theoretical option — which was barred in prac

tice by the racial barrier until at least 1964 — of applying

16

transfer to the Local 508 job as a new man in terms of job

seniority. If the senior black failed to apply or, more realis

tically, if Westvaco would not consider a black for a white job,

then another worker, usually a "new man" in the true sense, would

be placed. In effect, defendants administered a series of self-

contained small seniority units with only minimal openness to

2

penetration from outside the unit, clearly identifiable by race.

E • "Merger" of Segregated Sequences and Local Unions.

1. Effective May 8, 1968, Westvaco and the UPIU unions

merged the pairs of formerly segregated sequences and local

unions into single, nominally integrated units (Stip. 1MJ11-14) .

The 1968 mergers were the direct result of nearly a decade of

demands by Local 620. Defendants acceded to some of those de

mands only after years of fierce resistance, polite neglect,

and interminable delay.

Plaintiff Gantlin began by 1963 to have frequent and con

tinuing discussions of merger of the sequences and locals with

other Local 620 members, mill management and the white unions

(Tr. 1473-75, 1480-81, 1484-86, 1489, 1692, Gantlin; Pi. Ex. 9,

pp. 78-7 9, Hendricks).

21 The collective bargaining agreements recognized de

partmental seniority and mill seniority in addition

to job seniority, but the latter was by far the predeominant

factor. Mill seniority governed only layoff or demotion from

entry positions to the plant-wide pool, and transfers from the

pool to the bottom of a sequence (Stip. fl23). Department

seniority had little significance, since sequences rather than

departments were the critical seniority units.

17

On June 8, 1963, Gantlin wrote to the Presidents of Locals

435 and 508, proposing to negotiate a program of equal employment

opportunities consistent with Executive Order 10925 (1961); he

also sent copies of the letter to the Pulp Sulphite Workers'

International Representative, President, and Southern regional

Vice President, as well as Westvaco's Industrial Relations

Manager (Stip. Ex. 9; Tr. 1481, Gantlin; PI. Ex. 9, pp. 78-79).

The only official response to the letter came from the Inter

national President, who stated that there was "no use in delay

ing merger, but merely referred Local 620 to negotiations with

Local 508 (Stip. Ex. 10; Tr. 1482). Neither of the white locals'

Presidents responded and the International Representative just

said, "the time is not right" (Tr. 1483-84). Westvaco took

the position that merger was an internal union affair; and the

locals remained adamantly opposed to any merger (Tr. 382-83,

Hendricks; Tr. 1483, 1486, 1488, 1496, Gantlin; Pi. Ex. 6, pp.

57, 59, Rodgers; PI. Ex. 7, pp. 15-16, 18, McCants). Finally

Gantlin complained in 1966 to the President's Committee on Equal

Employment Opportunity, and wrote to the President of Westvaco

(Stip. Ex. 11; Tr. 1486—87), and the Regional Vice President

of the Pulp Sulphite Workers, who again referred the matter to

the Locals (Stip. Ex. 12-13; Tr. 1495, 1718, Gantlin). Although

Westvaco realized as early as 1963 that Local 620's demand for

merger was proper and inevitable (PI. Ex. 9, pp. 84-87), it took

no steps to bring it about until 1967 (PI. Ex. 9, pp. 82-83,

18

22

92—93; Tr. 1497, Gantlin). Gantlin continued to make no

progress until EEOC representatives investigated his complaints

and took a formal EEOC charge on April 25, 1967 (Tr. 1496-98;

see Stip. Ex. 14) .

Defendants first positive response was several discussions

during late 1967 followed by a meeting on January 15, 1968 at

which Westvaco made a specific proposal (PI. Ex. 30(a); Tr.

1051-02, Gantlin; PI. Ex. 7, p. 19). On February 6, 1968,

Local 620 rejected the Company's proposal and authorized a

counter-proposal to the Company's plan; the Local 620 plan

would have given Local 620 employees carry-over seniority in

the merged sequences back to June 8, 1963 (PI. Ex. 31; Tr.

1503-08, 1597-98, 1722, Gantlin; Tr. 694, 713, Melvin; Tr. 386-

"̂7 f Hendricks) . Local 620 also opposed the Company plan because

it provided special "run-around" rights in the Finishing and

Shipping department which would perpetuate white workers'

priority (Tr. 1504, 1515—16, 1601—02). Local 435 of course

insisted on preserving the "run-around" rights (Tr. 1514-15;

cf. PI. Ex. 7, pp. 25-28; Tr. 3081-82, Colbert).

22 Westvaco's delay is particularly revealing since the

Industrial Relations Managr knew in 1963 that Local

620 sought LOP merger with carry-over seniority (Tr. 386,

Hendricks; PI. Ex. 9, pp. 92-93), and sincehe met with Gantlin,

Melvin, and the white locals, to discuss merger from 1965 to

1967 (PI. Ex. 9, pp. 88 — 91) . The Manager could not offer any

explanation for why it took Westvaco nearly five years to make

its first proposal (Tr. 383; PI. Ex. 9, pp. 86-87).

19

Local 62 0 's objections and counter-proposals were ignored.

Locals 435 and 508 voted by April 28, 1968 to accept the merger

as proposed (Pi. Ex. 30(d), 30(e); Tr. 3084, Colbert). Local

620 voted 45-3 to reject the merger (Tr. 1516; PI. Ex. 30(e)).

The Pulp Sulphite Workers overrode Local 620's opposition by

pronouncing the merger accepted by majority vote of the three

Locals (PI. Ex. 30(e)), and by revoking Local 620's charter

and disbanding Local 620 (PI. Ex. 32(c)). Locals 435 and 508

absorbed former 620 members and accounts. Gantlin's refusal

to sign the Memorandum of Agreement on May 8, 1968 for Local

620 was therefore futile. He finally signed in June (Tr.

1521-27, 1724, Gantlin; PI. Ex. 9, pp. 100-01; Tr. 714, Melvin;

see PI. Ex. 30 (f) .

2. As the foregoing narrative makes plain, defendants

agreed to the 1968 merger reluctantly, with qualifying condi

tions to impede swift black advancement, and under considerable

pressure from the filing of plaintiffs' charges and complaints

of discrimination. (See pp. 16-19, supra.) These mergers

brought a major change in the structure of collective bargain

ing representation, seniority units, and promotional practices.

20

In all these mergers, the interests of all black employees

were subordinated to those of all whites then employed. However,

subsequently hired whites were deprived of the automatic prece

dence which their earlier counterparts had enjoyed. Local 620,

which had become a vehicle for expression of black employees'

complaints and interests, was abolished (Pi. Ex. 32(a), 32(b),

32(c)). Locals 435 and 508 absorbed its membership (PI. Ex.

32(c)), without any new election of officers (Stip. 1(12, PI.

Ex. 6, pp. 70-71). IBPS revoked the charter of Local 620 and

placed its assets in receivership.

Simultaneously, the jobs and sequences within the Local 620

jurisdiction were merged into the units represented by Locals

435 and 508. Westvaco and Locals 435 and 508 signed on May 8,

1968, a document entitled "Memorandum of Agreement" (Stip. Ex,

236) which embodied the terms of the merger (Stip. 1(11). in

every department except the Woodyard, separate sequences and

jobs were combined in a single progression based on the jobs'

24pay rates (see Stip. Ex. 1-2; Pi. Ex. 6, pp. 66-67), In

23 Local 620 had refused to agree to the merger because

of objections to "run-around" rights given to white

employees by the merger (Tr. 1521-24, 1526-27, 1724, Gantlin,

Tr. 714, Melvin; Pi. Ex. 9, pp. 100-01). IBPS' dissolution of

Local 620 and its announcement that the merger was approved by

majority vote of the three combined locals bypassed Local 620's

objections (PI. Ex. 30(e)). Subsequently plaintiff Gantlin, as

ex-President of Local 620, signed the Memorandum of Agreement

after it had already been imposed (Tr. 1325-26, Gantlin.)

24 The Woodyard merger was complicated by the existence

of four separate sequences (see Stip. Ex. 2). All

jobs in the traditional 620 (black) sequence — the Chipper

Feeder line — were below all jobs in the traditional 508

(white) sequence — the Crane Operator sequence (Stip. Ex.

2). However, the two other recently-established lines —

Wood Scaler (508) and Long Wood (620) — had pay ranges which

overlapped the lower and higher scales of the older sequences,

and had both white and black workers (Stip. 1(16) .

21

nine of the eleven operating departments — the exceptions were

the Woodyard and Finishing & Shipping — this method resulted

in all former 620 (black) jobs being placed below all former

435 or 508 (white) jobs in the merged sequence, as a result of

the pay disparities summarized at p. 8 above (compare Stip.

25

Ex. 2 and Stip. Ex. 1). In all departments, the dual entry

points which had existed before the merger —— one for whites

bound for higher operator jobs, the other for blacks doomed to

labor — were consolidated into a single entry job denominated

26poolman and placed at the bottom of the merged sequence

(Stip. Ex. 1; Tr. 400, Hendricks). Within the merged sequences,

promotions and demotions continued to be governed by job seni-

ority (Stip. Ex. 6, p. 1; PI. Ex. 9, pp. 102, 126). As a result,

white employees in higher paid former 435 or 508 jobs acquired

job seniority equal to their existing pre-merger seniority dates

in their current position and all lower jobs, including former

620 jobs, within the merged sequence. Black Local 620 employees

who became poolmen, however, were given job seniority dates of

May 8, 1968, as poolmen; and those who promoted subsequently to

former 435 or 508 jobs took their promotion date as their new

25 In some departments with dead-end 620 (black) jobs

for janitors or laborers — Power, Technical Services,

Receiving & Stores — those positions were attached to the new

departmental sequence at the bottom (entry) level (Stip. Ex. 1,

2; Tr. 395-96, Hendricks). In the Pulp Mill and Paper Mill,

the 620 janitor jobs were eliminated from the departmental se

quence (id.). In the departments with formerly separate 620

sequences — Recovery, Polychemicals, and Tall Oil — the

black jobs were tacked on to the bottom of the white sequence

positions, but above the new poolman entry job (Stip. Ex. 1-2).

"Brokeman" in the Paper Mill department; "Woodhandler"

in the Woodyard.

26

22

seniority date (Tr. 389-90, Hendricks; PI. Ex. 9, pp. 111-12;

Stip. Ex. 6).

In both Finishing & Shipping and Woodyard Operating Depart

ments, Westvaco and the white local unions negotiated special

"run-around" provisions to protect white workers from losing

ground to black 620 members who, because of the merger, were

slotted above them in the merged sequence. In the pre-merger

negotiations, Local 620 protested these "run-around" provisions

and their foreseeable effects (Tr. 1505-08, 1515-16, 1601-02,

Gantlin). Local 435, on behalf of its white members, insisted

on recognition of "prior rights" (Pi. Ex. 7, pp. 25-28; Tr.

1514-15, Gantlin; Tr. 3081-82, Colbert), and prevailed over

Local 620's opposition.

27

In Finishing & Shipping, "prior right" employees in

the Senior Roll Finisher category — all of whom were white

— were allowed continued priority in promotions to the lucra-

*

tive Truck Driver position, even though the merger had inserted

the black position of Car Bracer into the line above Senior Roll

Finisher (Stip. Ex. 6, p. 1; see Stip. Ex. 1; Pi. Ex. 7, pp.

24-25; Tr. 606-08, Collins). These "run-around" rights proved

extremely advantageous to white employees for many years after

the merger, during which they prevented qualified black employees,

with greater job seniority in the job immediately below Truck

27 Prior rights were recognized for employees who had

previously held, on a permanent or regular temporary

promotion basis, the next higher position. Of course, only

435 (white) employees had so held the Truck Driver job.

23

Driver, from gaining promotions ahead of "prior right" whites

(Tr. 606-07, 613-18, D. Collins; see Pi. Ex. 25(h)).28 Although

"prior right" black employees in the Poolman and Car Bracer

category were given reciprocal rights to the Car Loader and Car

Bracer positions, respectively, these rights were obviously

destined to be, and proved, meaningless, since the absence of

vacancies prevented theoretical beneficiaries from taking advan-

29

tage of them. In practice, all pre-1968 whites in the depart-

ment continued to promote ahead of pre—1968 black employees

even when the latter had greater job seniority.

In the Woodyard, the "prior rights" provision of the mer

ger gave a number of white 508 members, who had previously held

but been demoted from the Woodyard Assistant job, seniority in

the Wood Scaler position and jobs in the former 620 line although

they had never worked in those jobs. Subsequently, these.whites

exercised demotion or recall rights into those jobs ahead of

blacks with longer service in them (Tr. 1074-78, Middleton;

Tr. 3299, 3400-02, 3408, Nichols; Tr. 1163-65, Graham).

The actual effect of the 1968 merger on the relative stand

ing of black and white incumbent employees was nil. The use of

28 Some 12 or 13 whites were thereby placed ahead of up

to 24 black Car Bracers (Pi. Ex. 25(h),; Tr. 579-81,

588, 589, Ford, Tr. 653-54). These preferential promotions

continued until 1973 (Tr. 620, Collins).

29 The black Car Bracers were blocked in that category

by the promotion of "prior right" whites to Truck

Driver. This blockage rendered empty the "prior rights" of

four black Car Loaders to promote to the Car Bracer job (Tr.

610, Collins; Tr. 579-80, Ford; PI. Ex. 25(h)). The black

Poolmen who had theoretical "prior rights" to become Car

Bracers could not advance to Truck Driver because they could

not qualify for the job (Tr. 637-40, Collins).

24

strict job seniority in those departments where all blacks were

below whites in the merged lines, and the departure from strict

job seniority through "prior rights" in the remaining depart

ments, combined to assure that white employees' seniority—based

expectations, established during the period of overt segregation,

would not be disappointed.

Adoption of Mill Seniority System.

The next significant change in the Westvaco seniority sys

tem was the signing, by the Company and the UPIU unions, on

November 13, 1970, of a "Memorandum of Understanding" (Stip. Ex.

7) negotiated by Westvaco and the Office of Federal Contract

30

Compliance (OFCC) (Stip. 1f27) .

Following approval of the form of the Memorandum of Under

standing by OFCC, Westvaco presented it as a fiat to the unions,

which had not been consulted or involved in its negotiations

(Tr. 2921-23, 3062, Hendricks; Tr. 3249, 3256, Dunaway; Pi. Ex.

8, pp. 120-24). Initially, Local 435 voted to reject the Memo

randum of Understanding in August 1970 (UPIU Ex. 4; Pi. Ex. 8,

pp. 124-25). Local 508, which had a substantial black member

ship as a result of absorbing the former 620 Woodyard employees

31

into its unit, voted under some pressure to accept the

30 OFCC had investigated Westvaco in response to dis

crimination charges filed by plaintiffs on March 11,

1969 (Co. Ex. 2). The record contains extensive documentation

of and testimony about the negotiations leading to the Memorandum

of Understanding (PI. Ex. 84-92; Co. Ex. 94-99; PI. Ex. 93-94;

^^3-31, 2958-67, 3039-59, Hendricks). These documents show

that OFCC compelled a reluctant and dilatory Westvaco to agree

to adopt a mill seniority system by issuing a "show cause" letter

which would have triggered debarment of Westvaco from federal

contracts (PI. Ex. 97, p. 1; PI. Ex.93, pp. 21-24, 26-28).

31 It acted after the IBPS International Representative

characterized the Memorandum as "pretty good" and

sta^ed that if it were rejected the government would stuff a

"worse one" down their throats (Tr. 3199, Kane).

25

Memorandum. Westvaco, under a gun held by OFCC (Co. Ex. 103;

Tr. 2926, Hendricks), insisted that Local 435 approve the Memo-

32

randum, and the union capitulated.

The Memorandum of Understanding identified an "affected

class of black employees ("ACs") hired before May 1968 into

black (620) jobs, and gave them an opportunity to exercise

rights to promote, resist layoff, transfer, and be recalled

based on "mill seniority", or total length of employment at

33

Westvaco, rather than job seniority. The purpose of the

seniority system was to break the seniority roadblock

that confronted black employees whose prior relegation to

lower jobs on a racial basis was perpetuated through the use

34

of job seniority.

agreeing in contractual form to change their seni

ority system in the manner specified by the Memorandum, defen

dants proceeded to alter its terms in several significant ways.*

Each of these alterations took the form of an unwritten inter

pretation, limiting or counteracting the thrust of the mill-

seniority provisions in ways not authorized,or specifically

rejected,by OFCC.

32 The UPP International Representative explained to the

membership that it had to authorize signing, and the

Local voted to accept it in October 1970 (PI. Ex. 7, pp. 33-34*

Tr. 3252, Dunaway; UPIU Ex. 5).

33 See, e.g., Quarles v. Philip Morris, Inc., 279 F.Supp,

505 (E.D. Va. 1968); Robinson v. Lorillard Corp., 444

F.2d 791 (4th Cir. 1971), cert, dismissed 404 U.S. 1006 (1971);

Local 189, United Papermakers & Paperworkers v. United States,

416 F.2d 9 0 (5th Cir. 1969), cert, denied 397 U.S. 919 (1970).

The Memorandum applied mill seniority to production

sequences only. It did not apply to maintenance

positions represented by Local 508, Local 1753, or Lodge 183

(stip. Ex. 7; PI. EX. 9, pp. 158, 160, Tr. 411, Hendricks).

---- — ----------------------------------------------------- ----------

As initially proposed by Westvaco, the mill seniority plan

applied only to vacancies in permanent jobs (Co. Ex. 98(b), Sec.

VIA, 2.a and 2.b). OFCC required Westvaco to strike the word

"permanent", so that all vacancies, including temporary ones,

would be covered (Co. Ex. 98, p. 1, 1(6; Pi. Ex. 92). Subse

quently, the UPP International Representative told Westvaco that

failure to include 'temporary" explicitly was a defect that made

it unlikely that the Memorandum would "stand up", but Westvaco

stood firm (Pi. Ex. 9, pp. 126-27; Tr. 3256-57, Dunaway). In

its later implementation of the Memorandum, Westvaco managers

took the position that mill seniority was inapplicable to tem

porary promotions (see Tr. 406, Hendricks; PI. Ex. 51, pp. 13-14,

Tr. 883-89, Chaddick). OFCC was never informed of this inter

pretation of the Memorandum, and never discovered it.

Defendants also agreed to construe the Memorandum as sub

ject to non-contractual "prior rights" which were recognized

only by informal custom (Tr. 2932-33, Hendricks), and "recall

rights" recognized in union contracts. These prior rights

and recall rights, which resulted from employees' having pre

viously held a higher position than their present job, gave

35

many or even most white employees significant competitive

advantages over black employees. Since before May 1968 black

employees had been barred by the dual seniority lines from

progressing into white positions, blacks had not been able to

35 Due to both reductions in force and temporary promo

tions due to injury, vacation, or workload, the ma

jority of employees eligible for promotion had worked as many

as three or four levels above their current jobs (Stip. 1[21,

Op. 46; Tr. 380-81, 418, Hendricks; Tr. 3311-15, 3405, Nichols;

Tr. 3455-59, Sparkman).

accumulate prior rights or recall rights in the higher-paid jobs.

Westvaco never proposed or mentioned recognition of these rights

in its negotiations with OFCC, even though OFCC clearly intended

by the adoption of mill seniority to alter the formal and infor

mal expectations of white employees based on job seniority accrued

during a period of overt segregation of job opportunities (Tr.

2936-37, 2994-96, Hendricks). In contrast to the avoidance of

these matters with OFCC, Westvaco negotiated them extensively

• 36with white union officials (Tr. 419, 2937-40, 2953, 2996,

Hendricks), and reached firm but unwritten agreement that both

rights and recall rights would be allowed to override the

mill-seniority provisions of the Memorandum until all white

employees had obtained permanent promo-tions to the jobs they had

held on a temporary basis (Tr. 3017-20, 3001-02, 2954-55, 2937-40,

Hendricks). While the Memorandum is silent as to "prior rights,"

it cannot be read to authorize their recognition, as Westvaco's

Manager of Industrial Relations conceded (Tr. 419, 2938, 2992-93,

2998, Hendricks).

Westvaco negotiated with OFCC a provision which limits

use of mill seniority for promotion to the "next higher classi

fication" above the AC employee's current job (Stip. Ex. 7,

36 Since the abolition of Local 620 without provision for

black officials, the unions' leadership had been all-

and no blacks had attended any of the company-union meet

ings (PI. Ex. 7, p. 30; PI. Ex. 6, p. 84; Tr. 3224-26, 3234-35,

Brisbane; Tr. 414, Hendricks).

3 This preference for white employees with expectations

based on prior promotions was formally communicated by

Westvaco's personnel officials to departmental managers and super

visors (Tr. 1332-35, Naylor; Tr. 1456, 1471, Wright; Tr. 2753-54,

Kennedy; Tr. 620-23, 643-49, Collins; Tr. 3308, Nichols).

28

Sec. A.2.a, Tr. 3019-20, Hendricks). This provision prevented

black employees from promoting to vacancies more than one level

higher, regardless of their qualification for the vacant job,

even if the employee had previously worked and qualified in the

intervening positions (Tr. 3020, PI. Ex. 9, p. 142, Hendricks;

Tr. 3397, Nichols, Tr. 3460, Sparkman). Westvaco's Manager of

Industrial Relations admitted that such promotions were feasi

ble in many sequences but were not allowed only because OFCC

did not insist on them (PI. Ex. 9, pp. 142-150, Tr. 409-10,

Hendricks). Westvaco applied this provision in a still more

restrictive manner, and one not required or expressly permitted

by the Memorandum's terms, by interpreting the "next higher

classification" language to refer to the position above the

employee's permanent job — rather than the temporary or long

term temporary position in which the employee might actually be

working (Tr. 1050-51, Hartin; Tr. 3019-20, Hendricks; Tr. 868-

38

69, Chaddick).

The effect of this interpretation was to limit fully quali

fied ACs' ability to utilize mill seniority to competitions with

white employees at the same permanent job level, and to prevent

38 Westvaco applied the same gloss, without any basis

in the language of the Memorandum of Understanding,

to demotions due to reduction in force. Thus a mill-senior

black employee could be displaced by a junior white employee

if the latter bumped down from a higher permanent job level —

even if the two were actually working at the same job level,

as in fact happened (Tr. 3022-33, Hendricks, Tr. 861-64,

Chaddick).

ACs from catching up with whites who had, through job seniority,

prior rights, or recall rights, remained ahead of them in perma

nent job assignment level (Tr. 823, 811, 864, Chaddick).

G. Refusal to Implement Mill Seniority System.

The Memorandum of Understanding, by its terms, was supposed

to be placed in effect January 1, 1971 (PI. Ex. 9, p. 175). Yet

in actuality the seniority changes prescribed by the Memorandum

did not occur until years later, and in the interim black em

ployees were repeatedly denied promotions and other job oppor

tunities to which they were entitled under the mill-seniority

provisions of Westvaco's contracts with OFCC and the UPIU unions.

In reality, defendants simply continued to follow a job seniority

system until they were discovered doing so by plaintiffs in the

course of this litigation. The dates when mill seniority was

first substituted for job seniority in these departments are

shown in the following table:

Department Date

Recovery June-July 1973 (temp.)

June 1974 (perm.)

Tall Oil 1973 (temp.)

April 8, 1974 (perm.)

Polychemicals Sept. 3, 1973

Paper Mill May 28, 1973 (temp.)

Pulp Mill July 1973 or later

Technical Services Late 1973

Finishing &

Shipping

December 1973

Woodyard April 30, 1973

Power August 1973

1348, Naylor). The department manager acknowledged that at

least until February 1973, "prior rights" were not affected by

the Memorandum of Understanding (Tr. 1334). Black employees

like Isaiah Moorer were denied mill seniority promotional rights

39d

until 1973 (Tr. 1014, 1016).

(4) Paper Mill. The first use of mill seniority for tem

porary push-up came on May 28, 1973 (Stip. 1145, p. 28) . At the

time his deposition was taken on July 19, 1973, the President

of Local 435 (and a Paper Mill employee for 20 years) still

believed that job seniority governed temporary promotions (PI.

39e

Ex. 7, pp. 45-47).

(5) Pulp Mill. Apart from the John Smalls promotion offer,

see p. 30, supra, no other AC promotions using mill seniority

3 9f

were made in the Pulp Mill prior to 1973 or 1974.

(6) Technical Services. Job seniority governed push-ups

until the latter part of 1973. Only thereafter was AC member

*

_________________________________________________________________3 2

39d From May 1972 to February 1973, Winston Rabon, a junior

white in the Second Operator job, pushed up to First

Operator ahead of three senior black ACs who were also Second

Operators (Tr. 1337, Naylor). Indeed, at his February 1973 depo

sition, the manager did not even know what the term "affected

class employee" meant (Tr. 1359, Naylor).

39e He stated that he understood the Memorandum was not

supposed to operate in this manner, and was being

changed "right now," PI. Ex. 7 at 47. William Gilliard, a black

AC Paper Mill worker, testified that mill seniority was not used

until he began to push ahead of several junior whites from Seventh

to Sixth Hand in 1973, after several years when those whites had

received priority for promotions (Tr. 1400-03, 1404, 1417).

39f When his deposition was taken on July 19, 1973, the

President of Local 508 had never heard of any bypassing

of a white employee by a mill-senior black employee, or any use of

the Memorandum of Agreement, anywhere in the 508 Jurisdiction (PI.

Ex. 6, pp. 86-87, Rodgers).

George Smith allowed to utilize his mill seniority to push

ahead of junior whites (Tr. 102-03, 114, 123, Smith).

(7) Finishing and Shipping. No promotions of ACs based

on mill seniority rights under the Memorandum of Understanding

occurred until December 1973 (Stip. 1(45) . The Supervisor tes

tified that junior whites continued to exercise their run-around

rights to the Truck Driver position, to the detriment of senior

Blacks, until this practice was cut off, after discussions with

Personnel and union leadership, by implementation of the Memoran-

39g

dum of Understanding in early 1973 (Tr. 620, 643-44, 646, 649).

(8) Woodyard. Permanent promotions of AC employees on

the basis of mill seniority began on April 30, 1973 (Stip.

3 9h

1145) . Use of mill seniority resulted from a grievance

filed by a Black Committeeman on behalf of a senior black worker

(Tr. 1213-14, Williams; Tr. 726-27, Melvin). Even after the

first use of mill seniority in the Woodyard, Westvaco continued

to resist full implementation of the Memorandum of Understanding

and to make promotions of junior whites based on job seniority

33

39g The President of Local 435 affirmed that no mill seni

ority promotions had occurred as of July 19, 1973 (PI.

Ex. 7, pp. 39, 45). Three Black employees testified that some par

tial recognition of mill seniority rights began about 18 months

before trial (Tr. 531, 536, Rhodes; Tr. 673, 677, Williams; Tr. 581

84, Ford). Before and after that time, these three men were denied

permanent and temporary promotions that went to junior whites (Tr.

678, Williams; Tr. 579-82, 588-89, Ford; Tr. 535, 538, 554, Rhodes)

The rights of others of the 7 black Car Bracers who had not waived

promotions to Truck Driver were also subordinated to those of the

junior whites (see PI. Ex. 25(h), 43; Tr. 619-621, 631, Collins).

39h Testimony that mill seniority had never been used before

that date — for permanent promotions, temporary push-ups

or demotions — was given by James Middleton and Wilson Melvin, Jr.

both 508 committeemen (Tr. 691,706, 716, 719-21 Melvin; Tr. 1058-61

Middleton). Plaintiff Clifford Graham and Paul Williams confirmed

that date (Tr. 1163, Graham; Tr. 1215-16, 1221, 1207, Williams).

34

or "prior rights" (Tr. 1087,Middleton; Tr. 1191-1201 Williams;

39i

Tr. 1102-04, Middleton).

2. The record demonstrates that the reason for defendants'

reluctant implementation of the mill seniority system, two to

three years after its theoretical adoption, was discovery ini

tiated by plaintiffs' counsel. On December 14, 1972, Westvaco's

Manager of Industrial Relations testified in deposition that

he didn't know how many promotions based on mill seniority had

actually occurred, and couldn't name any (PI. Ex. 9, pp. 175-

40

77, Hendricks). His deputy, whom the Manager identified

as more knowledgeable, was also unable to identify any ACs pro

moted using mill seniority, at his deposition taken January

41

31, 1973 (PI. Ex. 10, pp. 63-66, Debnam). Westvaco depart

mental managers conceded that mill seniority had never been

actually applied in their departments at depositions taken

January 31, 1973 (Hartin, Woodyard, at 43-45), February 1, 1973

39i As late as trial, the Woodyard Supervisor, Stoney Hartin,

still had no idea when the Memorandum of Understanding

was implemented; he testified that it went into effect in 1968

(Tr. 1054-56) .

Prior to the full implementation of the Memorandum of

Understanding, many blacks in the Woodyard lost contests for

promotion or demotion to junior whites. Clifford Graham and

other blacks lost promotion to white employee Tolle (Tr. 1163-

65, Graham; Tr. 1074-76, Middleton), and Paul Williams was

demoted from Long Log Operator, on the basis of job seniority

while a junior white employee, Weaver, remained in the job (Tr.

1187-88, Williams). The Woodyard Superintendent admitted that

award of a Long Log job to white employee Tucker in April 1972

(see Co. Ex. 104 (i)) was a "mistake"; had the Memorandum been

followed, W.D. Lee, a black, would have been promoted based on

mill seniority (Tr. 3317-18, 3407-08, Nichols).

40 Hendricks guessed at two specific promotions, as to

one of which he was wrong (the other was Smalls), and

erroneously guessed that there had been "a number" of others.

41 Debnam thought there were "several" examples, and

believed that use of mill seniority was "an absolute

thing"; but was unsure whether it had, in fact, been followed.

35

(Chaddick, Recovery, at 13-23, and Naylor, Polychemicals, at

10-12), March 14, 1973 (Wright, Tall Oil, at 28-32), and March

42

15, 1973 (Collins, Finishing & Shipping, at 16-17). Union

officials testified similarly on July 19, 1973 (McCants, Local

435, PI. Ex. 7, pp. 39, 43-45; and Rodgers, Local 508, PI. Ex. 6,

pp. 86-87). Finally, two black union stewards in the Woodyard,

who had learned about their entitlement to mill seniority from

plaintiffs' counsel (Tr. 696, 705, 720-21, Melvin; Tr. 1058-61,

Middleton), challenged officials of Local 508 and Westvaco in

April 1973 about their failure to implement mill seniority for

ACs (Tr. 717, 720-21, Melvin; Tr. 1083-85, 1119-21, Middleton).

The first recognition of AC mill seniority was triggered by this

series of depositions.

3. The existence of the Memorandum of Understanding and the

entitlement of ACs to use mill seniority was never effectively

communicated to employees who might have benefitted from this *

information. Although Westvaco promised OFCC to advise employees

in writing of the new agreement (Co. Ex. 98(b) HE, Tr. 2973, 2980,

Hendricks), and despite its frequent distribution of written in-

43

formation on relatively trivial subjects (Tr. 2973-80, Hendricks),

42 The page citations in text are to depositions in

the record but not admitted in evidence. The cited

testimony is not disputed.

43 Westvaco regularly communicates in writing with its

employees by special mailings, by posting notices

on bulletin boards, by handouts with paychecks or at the

plant gate, and by Company newsletter. It has used such

means to solicit assistance for a volunteer fire brigade,

to announce the appointment of high corporate officers, to

distribute W-2 forms and corporate annual reports, and to

deliver gift turkey cards at Christmas (Tr. 2973-80,

Hendricks).

36

Westvaco gave no written notice to affected AC employees (Tr.

416, 2981, PI. Ex. 9, pp. 172, 175, Hendricks; PI. Ex. 10, pp.

559, Debnam). Although personnel officials said they assumed

that ACs would be told about their rights by departmental super

visors or union officials, the personnel officials took no

steps to assure that any communications occurred or to determine

whether they had occurred (PI. Ex. 9, pp. 172-73, PI. Ex. 10,

pp. 54-57, Tr. 415-16). Thus, even though George Debnam was

in charge of both operation of the TRC system and implementa

tion of the Memorandum of Understanding (PI. Ex. 9, pp. 170,

164; PI. Ex. 10, p. 46), when ACs came to discuss transfer with

him, he didn't mention mill seniority because, as he said, "I

feel like it is understood and known. But, I can't swear to

it" (PI. Ex. 10, pp. 54-55). Neither Local 435 nor Local 508

posted or distributed any written notice of the major change

that had supposedly taken place in their seniority system, and

neither Local's President ever spoke to any black employees

about it until 1973 (PI. Ex. 7, pp. 84-86, 93, Rodgers; PI.

Ex. 6, pp. 34-38, McCants; Tr. 3231-40, Brisbane). C.A.

Rodgers, President of Local 508 from 1969 - 1972, testified

that after the meeting (in August 1970) at which the local

ratified the Memorandum, there was no further discussion of

it at union meetings (PI. Ex. 6, pp. 84-85, Rodgers). The

union never posted any notice of ratification, nor any copy

of the Memorandum, and he never spoke to any black members

about it since nobody told him to do so (id. at 85-86).

37

Rodgers believed it possible that no black member of 508 had ever

heard of the Memorandum (id. at 93). Jerome McCants, President

of Local 435 from 1966 to 1972, testified that apart from the

meeting attended by Uly Rhodes and others the union never com

municated with black members about the Memorandum, never posted

a copy, and he personally had never spoken to any black employee

about it since ratification (PI. Ex. 7, pp. 34-38, McCants).

Although a few AC members apparently heard oral references

to mill seniority at a single union meeting or around the mill,

the great majority of black employees were completely uninformed

44

of their supposed rights. Very few AC employees knew that

they had promotional rights based on mill seniority. As a result,

ACs were unaware throughout the 1971-73 period that their mill

seniority rights were being consistently violated, and were

unable to take any action to preclude further violations.

44 Uly Rhodes and two other black employees were present

at the Local 435 union meeting when the proposed Memo

randum was rejected (Tr. 530, 539-40, Rhodes; Tr. 3089-90, Col

bert) . Because no document was available, Rhodes did not under

stand the proposal very well, and could not explain it to other

black employees in his area, Finishing & Shipping (Tr. 547, 549,

568, Rhodes; Tr. 585-86, Ford; Tr. 673-76, Williams). Rhodes

and the others never received any information at that time from

the Company (Tr. 541-43, 537-38, Collins; Tr. 592-95, Ford),

and of course had no information that the Memorandum was even

tually adopted.

Several other black employees were perhaps given some

minimal information by departmental officials. But the only

efforts of this sort were directed at several employees in Re

covery and in Finishing and Shipping who had waived further pro

motion, generally due to illiteracy (Tr. 791-96, 876-77, 893,

Chaddick; Collins, Tr. 631, 643; Co. Ex. 10). No systematic

effort was made to give any information to employees who could

benefit from the information.

Thus, only in Finishing and Shipping was any informa

tion given prior to 1973 to any Blacks to whom it might make any

sense or difference. Even there, the information was so incom

plete as to be useless.

Testimony by Black ACs who were kept ignorant of their

rights is summarized at notes 44a-44i and accompanying text,

infra.

Because there was no systematic, centralized effort to in

form ACs about the Memorandum of Understanding or mill seniority

rights, the testimony of individual employees takes on particular

significance on this issue. Over 20 ACs testified that Westvaco

and the unions had never informed them of the existence of the

Memorandum of Understanding or their mill seniority rights. In

virtually every case these employees first learned of their rights

from plaintiffs, their counsel, or other employees in contact with

them, after the introduction of the Memorandum as an issue in this

case in December 1972-January 1973.

Among the employees who so testified were many of the most

articulate, active, and concerned black employees at Westvaco's

mill, including a number who were former Local 620 officers,

recent 508 stewards, or persons who had a practice of closely

following seniority changes. Plaintiff Gantlin testified that

he was first told of the Memorandum of Understanding late in

4 4a1972 by his attorneys (Tr. 1535-36, 1539). Wilson Melvin,

Jr., Local 508 Committeeman and shop steward, and longtime mer

ger advocate, also learned of the Memorandum from counsel in

44b

early 1973 (Tr. 696) .

________________________________________________________________3î

44a This occurred despite the fact that he was in frequent

contact with the Industrial Relations Manager, the Per

sonnel department, and officers of Locals 435 and 508 and the Pulp

Sulphite Workers International from 1970 to 1972, as he had been

for years, about black employment opportunities (Tr. 1537-38,

1534, 1727).

44b Company and union officials had never previously dis

cussed mill seniority with him (Tr. 696-97, 705, 720).

When Melvin asked the Local 508 President, who did know about

the Memorandum, why blacks had not been informed, he offered

the excuse that he had not been President in 1970 (Tr. 696;

Tr. 1081-82, Middleton).

39

James Middleton, another 508 steward and Committeeman

and a regular attendee at union meetings, first heard of the

Memorandum or mill seniority when Melvin challenged the Local

President to explain his failure to give earlier information

to Black employees (Tr. 1079-82, 1059-60) . Five other Wood-

yard employees also testified that they had never been told

44c

about the Memorandum of Understanding or mill seniority.

Five Recovery department employees also testified that defendants

had never informed them of the Memorandum or their rights under

44d

it. Other Black AC employees who gave similar testimony

44e 44f 44g

worked in the Paper Mill, Power, Technical Services,

44c See testimony of Paul Williams (first heard from coun

sel in 1974) (Tr. 1206-07, 1215, 1223); A.L. Gardner

(Tr. 1240, 1247); Franklin Carter (Tr. 1269-70); plaintiff Clifford

Graham (informed of Memorandum by plaintiff Gantlin and counsel,

but may have heard a rumor about mill seniority in 1972) (Tr.

1161-62, 1172, 1175, 1176); William Frederick, Sr. (heard from

counsel) (Tr. 1372); and plaintiff George Chatman (first heard

of Memorandum of Understanding and mill seniority from counsel)

(Tr. 504, 517, 522).

44d See testimony of Elijah Sparkman, Jr. (told by counsel

in December 1972; supervisor never discussed either

Memorandum or mill seniority) (Tr. 734, 735, 747); plaintiff