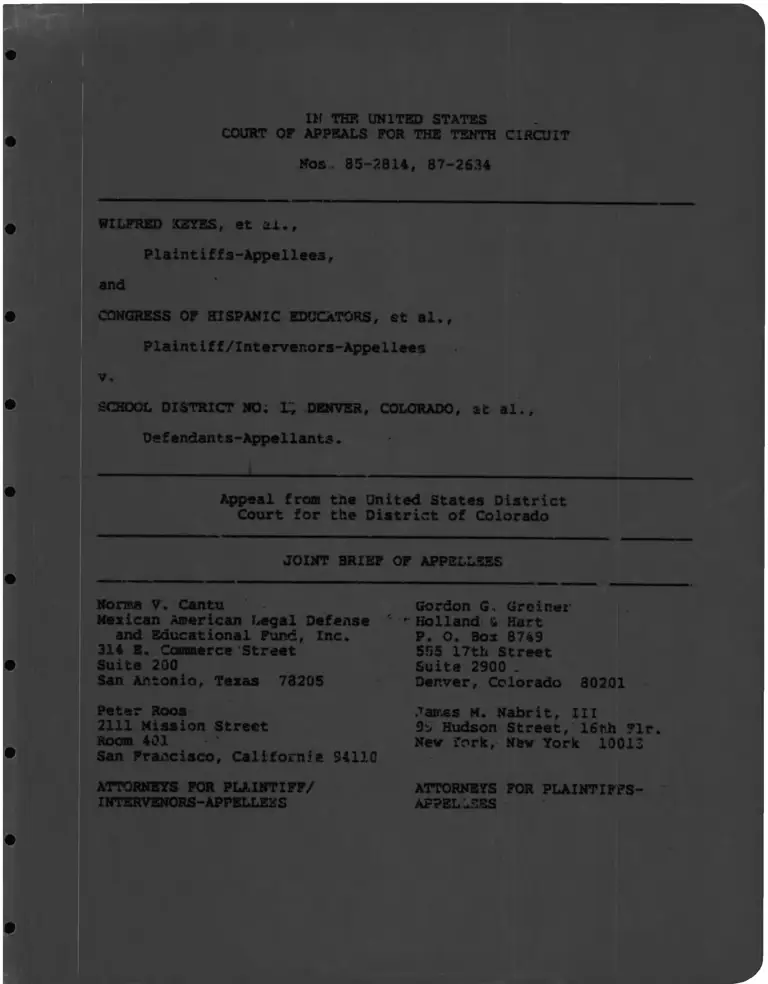

Keyes v. School District No. 1 Denver, CO. Joint Brief of Appellees

Public Court Documents

June 2, 1988

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Keyes v. School District No. 1 Denver, CO. Joint Brief of Appellees, 1988. 0d4837e7-b99a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c203c2df-fce9-4ef3-a858-349425ac29e7/keyes-v-school-district-no-1-denver-co-joint-brief-of-appellees. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

IN THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE TENTH CIRCUIT

Nos, 85-2814, 87-2634

WILFRED KEYES, et ai.r

Plaintiffs-Appellees,

and

CONGRESS OF HISPANIC EDUCATORS, et al..

Plaintiff/Intervenors-Appellees

v,

SCHOOL DISTRICT NO; IT, DENVER, COLORADO, at al.,

Dsfendants-Appellants.

Appeal from the United States District

Court for the District of Colorado

JOINT BRIEF OF APPELLEES

Norma V. Cantu

Mexican American Legal Defense '■

and Educational Fund, Inc.

314 E. Commerce Street

Suite 200

San Antonio, Texas 73205

Peter Roos

2111 Mission Street

Room 401

San Francisco, California 9411C

ATTORNEYS FOR PLAINTIFF/

INTERVENORS-APPELLEES

Gordon G„ Greiner

Holland & Hart

P. O. Box 8749

555 17th Street

Suite 2900 .

Denver, Colorado 80201

James M. Nabrit, III

9^ Hudson Street, 16th Fir.

New fork,- New York 10013

ATTORNEYS FOR PLAINTIFFS-

AFPEL.LSES

TABLE OF CONTENTS

JURISDICTION ................................................... 1

STATEMENT OF CASE............................................... 2

HISTORY OF THE CASE ....................................... 2

The 1974 Decree ...................................... 2

The 1976 Order ....................................... 3

The 1979 Hearings and Order .......................... 3

The Hearing On The Total Access Plan -

March, 1982 .......................................... 5

Hearing On Consensus Plan And Order Of

May 12, 1982 ......................................... 5

The Ruling On The Language Complaint -

December 1983 ........................................ 6

Events Leading Up To The 1984 Hearings ...............7

THE PROCEEDINGS BELOW..................................... 9

RESTATEMENT OF FACTS........................................... 13

The History of Integration and Resegegation At

Barrett, Harrington And Mitchell Elementary

Schools .................................................. 13

Barrett .................................................. 14

Harrington ............................................... 15

Mitchell ................................................. 15

Remedial Proposals For Barrett, Mitchell and

Harrington ............................................... 17

The Resegregative Effect Of The Baby-Sitter

Transfer Policy .......................................... 19

Evidence Relating To Building Utilization, School

Construction And Abandonment And Pupil Assignment

Practices ................................................ 22

Colorado Constitution "Anti-Busing" Amendment

Faculty Segregation and Desegregation ......

ARGUMENT..........................................

I. The findings and record abundantly support

the injunctions in effect from 1976 until

October 1987 and the retention of jurisdiction

during that period ..........................

A. The Board's arguments about the

previous injunctions are without merit

because of mootness, untimeliness and

waiver or acquiescence .................

B. The findings of transfer abuses

supported injunctive relief and

retained jurisdiction ...................

C. The findings on faculty segregation

supported injunctive relief and

retained jurisdiction ..................

D. The duty to prevent re-establishment

of the dual system by construction and

abandonment policies supports the

retention of jurisdiction ..............

E. The finding that the Consensus Plan

needlessly resegregated Barrett,

Mitchell and Harrington supported the

1985 Orders ............................

F. The need to avoid conflict between

desegregation remedies and the

language consent decree supports the

retention of jurisdiction during

implementation of the language plan ....

G. The court did not abuse its discretion

in retaining jurisdiction and in its

management of the case .................

H. The decisions below are not in conflict

with the Spangler case .................

II. The record and findings support the October

1987 injunction and the limited retention

25

26

27

27

27

30

31

32

33

36

37

38

-ii-

of jurisdiction .....................................40

III. The Interim Decree is an Appropriate

Exercise of Judicial Discretion......................41

School Desegregation Is Not Yet Complete

In Denver ...........................................42

The Interim Decree Is A Temporary, And

Reduced Intrusion Into Total Board Control ......... 43

The Provisions Of The Interim Decree Are

Sufficiently Specific Under Rule 65(d)....

Adequate Safeguards Exist Against

Inadvertent Contempt ....................

The Decree Properly Describes The Enjoined

Conduct In Terms Of Its Effect ..........

The Interim Decree Imposes No Requirement

Of Maintaining Racial Balances Through

Periodic Adjustments In Assignments .....

The Interim Decree Imposes No Obligation

To Undertake New Remedies ............

44

45

46

48

48

CONCLUSION ....................................................49

REQUEST FOR ORAL ARGUMENT......................................49

-ill-

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases Page

Adams v. United States, 620 F.2d 1277

(8th Cir.), cert. denied. 449 U.S.

826 (1980) ............................................... 31

Battle v. Anderson. 708 F.2d 1523

(10th C'ir. 1983), cert dismissed.

465 U.S. 1014 (1984) .......................... 1,27,33,37,39

Board of Pub. Inst, v. Braxton. 326 F.2d 616

(5th Cir. 1964) ........................................... 2

Brown v. Board of Education. 349 U.S. 294

(1955) ................................................... 37

City of Mesquite v. Aladdin's Castle. Inc..

455 U.S. 283 (1982) ..................... 39

Columbus Board of Ed. v. Penick. 443 U.S. 449

(1979) ................................................ 31,34

Davis v. School Commissioners of Mobile. 402

U.S. 33 (1971) ........................................... 34

Dayton Board of Ed. v. Brinkman. 443 U.S. 526

(1979) (Dayton II) ........................ 31,34,44

Dowell v. Board of Education. 795 F.2d 1516 (10th Cir.)

cert, denied. ___ U.S. ___, 107 S.Ct.

420, 93 L.Ed. 2d 370 (1986) ........................ 33,39,45

Ford v. Kammerer. 450 F.2d 279 (3rd Cir.

1971) .................................................... 46

Frederick L. v. Thomas, 557 F.2d 373

(3rd Cir. 1977) ........................................... 2

Green v. County School Board. 391 U.S.

430 (1968) ............................................ 32,33

Hoots v. Commonwealth. 587 F.2d 1340 (3rd

Cir. 1978) ........................ 2

Keyes v. School District No. 1. 413 U.S.

189 (1973) ............................................... 14

Keyes v. School District No. 1, 521 F.2d 465

(10th Cir. 1975) .......................................... 2

Keyes v. School Dist No. 1, 474 F. Supp. 1265

(D. Colo. 1979) ........................................ 3,35

Keyes v. School Dist No. 1, 540 F. Supp. 399

(D. Colo. 1982) ............................. 5,6,23,25,35,40

Keyes v. School Dist No. 1, 576 F. Supp. 1503

(D. Colo. 1983) ......................................... 6,7

Keyes v. School Dist No. 1, 609 F. Supp. 1491

(0. Colo. 1985) ............ Passim

Keyes v. School Dist No. 1, 653 F. Supp. 1536

(D. Colo. 1987) .....................................Passim

Keyes v. School Dist No. 1. 670 F. Supp. 1513

(D. Colo. 1987) .................... 1,11,12,24,25,30,42,47

Morales v. Turman, 535 F.2d 864 (5th Cir.

1976) ..................................................... 2

Morgan v. Nucci. 831 F.2d 313 (1st Cir.

1987) .............................................. 42,43,48

N.A.A.C.P. v. Lansing Bd. of Ed.. 559 F.2d 1042

(6th Cir. 1977) .........................................31

New York Tel. Co. v. Communications Workers

of Am. 445 F.2d 39 (2nd Cir. 1971) ....................... 46

Pacific Marine Ass'n v. International.

L.&.W.U. . 517 F.2d 1158 (9th Cir. 1975) ...................46

Pasadena City Bd. of Educ. v. Spangler. 427 U.S.

424 (1976) ............................................ 38,48

S.E.C. v. Jan-Dal Oil & Gas, Inc.. 433 F.2d

304 (10th Cir. 1970) ..................................... 39

Cases Page

-v-

Cases Page

Scandia Down Corp. v. Euroquilt, Inc., 772

F.2d 1423 (7th Cir. 1985) .............................44,45

Swann v. Board of Education, 402 U.S. 1

(1971) ............................................... Passim

System Federation v. Wright. 364 U.S. 642

(1961) ................................................... 39

Taylor v. Board of Education, 288 F.2d 600

(2nd Cir. 1961), .......................................... 2

United States v. Montgomery County Board

of Ed. 395 U.S. 225 (1969) ............................... 32

United States v. Oregon State Medical Soc..

343 U.S. 326 (1952) ................................... 39

United States v. Swift & Co.. 286 U.S.

106 (1932) ................................... 39

United States v. W. T. Grant Co.. 345 U.S. 629

(1953) ................................................... 39

Youngblood v. Board of Public Instruction

of Bay County. 448 F.2d 770 (5th Cir. 1971) ..............42

Other Authorities:

20 U.S.C. S1703(f) ............................................. 6

28 U.S.C. S1292(a)(1) ........................................ 1,2

Colorado Constitution, Article IX, Section 8 ............25,40,41

Rule 65(d) Fed.R.Civ.P......................................... 44

Attachments:

Keyes v. School District No. 1, 540 F.Supp. 399

(D.Colo. 1982)

Keyes v. School District No. 1. 670 F.Supp. 1513

(D.Colo. 1987)

JURISDICTION

This case involves an appeal from two orders which have been

superseded, and an effort by the United States, as amicus. to

have the court reverse an injunction which has not yet been writ

ten.1 Appellees submit that the appeal in No. 85-2814 should be

dismissed for lack of appellate jurisdiction.2 That appeal from

the Order of June 3, 1985 (609 F.Supp. 149) which declined to

vacate or modify the 1974 Final Decree, is moot. Battle v.

Anderson. 708 F.2d 1523, 1527 (10th Cir. 1983). The 1974 Decree

was superseded by the Order of October 6, 1987 (670 F.Supp. 1513)

which is the subject of the District's other appeal No. 87-2634.

The Board's appeal of the June 3, 1985 order's refusal to

declare the District "unitary", is not a permissible

interlocutory appeal from an injunctive order under 28 U.S.C.

S1292(a)(l). A refusal to issue a declaratory judgment that a

defendant has complied with an injunction is not a reviewable

injunctive order.

1 Space limitation precludes a full reply to the premature

argument of the United States against the entry of a permanent

injunction at the conclusion of this case. That injunction does

not exist, nor do all of the fact findings necessary to a sub

stantive analysis of the propriety of any permanent order.

Should the Court nevertheless wish to address that issue, we

request leave to file a supplemental brief on that topic. See

Amicus Brief at 16-20.

2 Appellees' Motion to dismiss the appeal was denied "without

prejudice to renewing the jurisdictional issue before the merits

panel." Order of May 7, 1986.

The appeal from the Order of October 29, 1985 is also mooted

by the 1987 interim Decree and is also not an appeal from an

injunction. It merely required the preparation and filing of a

desegregation plan and was not an injunction under S1292(a)(1).3

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

HISTORY OF THE CASE.

The 1974 Decree. The 1974 Decree incorporated a racially-

explicit plan of student assignment prepared by a court appointed

expert.4 On cross-appeals, this court affirmed most provisions

of the Decree but upheld plaintiffs' argument that certain

aspects of the plan did not sufficiently integrate the system.5

3 The point was briefed in our memorandum in support of the

motion to dismiss, pp. 7-11. Taylor v. Board of Education. 288

F.2d. 600 (2nd Cir. 1961); Hoots v. Commonwealth. 587 F.2d 1340

(3rd. Cir. 1978); Frederick L. v. Thomas 557 F.2d 373 (3rd Cir.

1977); Morales v. Turman, 535 F.2d. 864 (5th Cir. 1976). The

only contrary authority (Board of Pub. Inst, v. Braxton. 326 F.2d

616 (5th Cir. 1964)) is plainly distinguishable and inapposite

here where there was never an injunctive order requiring that the

plan be implemented. See 653 F.Supp. 1536, 1542.

4 Contrary to the Board's description of the Finger Plan as

"racially neutral", the plan deliberately took account of race to

promote school integration and to overcome the fact that many mi

nority pupils lived in segregated neighborhoods. The plan

changed grade structures to "pair" minority and Anglo schools,

drew attendance area lines to promote integration, and created

"satellite" attendance areas to transport pupils away from

schools in segregated neighborhoods.

5 The rejected portions included the provision for only

part-time pairing of certain elementary schools and the failure

to include five predominately Hispanic elementary schools in the

desegregation plan. Keyes v. School District No. 1. 521 F.2d

465, 477-79, 479-80 (10th Cir. 1975).

The 1976 Order. On remand the parties agreed to changes in

the plan, the court accepted the stipulation, and the changes

were implemented in September 1976.® At the Board's request, the

1976 order provided for a three-year moratorium before any major

changes of the plan would be considered. The Board acquiesced in

the exercise of the court's continuing jurisdiction implicit in

that provision. There was no appeal from the 1976 order.

The 1979 Hearings And Order. As the end of the three-year

moratorium neared, the district court learned that the Board

wished to close several elementary schools because of a decline

in enrollment.7 After a hearing the court permitted the

requested school closings but rejected the Board's reassignment

proposals and implemented some of those proposed by plaintiffs.

The court said:

"Where I have disagreed with the Board's pro

posal, that disagreement results from the

belief that the choices which I have made are

more consistent with movement in the direc

tion of a unitary system." 474 F.Supp. at

1272.

The Board did not appeal from the 1979 Order. In fact dur

ing that period the Board accepted the court's continuing

6 See Order dated March 26,1976, DPS Add. at 22-24.

7 The court ordered the Board to report on the proposed

changes, which it did through Resolution No. 2060, on May 1,

1979. Plaintiffs objected that it proposed a pattern of

assigning Anglo pupils to schools which were already predomi

nately Anglo, with the converse being true for minority pupils.

-3-

jurisdiction and its conclusion that unitary status had not been

attained. The Board in May, 1980 appointed the Ad Hoc Committee

to formulate guidelines for a unitary system and to suggest

changes in the pupil assignment plan. After that committee's

final report in June 1981, the Board after further deliberations

produced a plan which came to be known as the Consensus Plan.

The reasons for a planned major reorganization of the

schools in the fall of 1982 were the Board's decisions to close

nine more schools and to reorganize the system's secondary grade

structure into middle schools with grades 7-8 and high schools

with grades 9-12.

On the eve of adopting the Consensus Plan Board member

William Schroeder, an opponent of "forced busing" and proponent

of neighborhood schools, introduced the Total Access Plan. The

Total Access Plan offered every pupil freedom of choice and free

transportation to attend any school in the district without

regard to residence or location.8 The Board adopted both the

Total Access and Consensus plans and asked the court to choose

between them. The court directed the Board to make the policy

choice.9 The Board then proposed the Total Access Plan, which

was set for hearing on plaintiffs' objections.

8 The plan also called for a limited number of magnet schools,

and added some educational embellishments.

9 See Order of November 12, 1981.

-4-

The Hearing On The Total Access Plan - March 1982. Follow

ing a two-week hearing in March 1982, the court ruled that the

Total Access Plan was completely unacceptable. In its opinion,

540 F.Supp. 399, the court explained why the plan was rejected:

"The probability that the Total Access Plan

would result in resegregation of schools is a

fair inference from the facts that most of

the students would be served by regular

schools; that the regular schools must be

equal in the quality of their curriculum; .

that housing patterns in Denver continue to

be segregated; and that most families would

choose to have their children attend the

closest school.

"In summary, the Total Access Plan was

lacking in concern, commitment and capacity."

540 F.Supp. at 402.10

The Board filed no appeal. Rather it submitted a modified

Consensus Plan which was considered in an April 1982 hearing.

Hearing On Consensus Plan And Order Of May 12, 1982. Plain

tiffs objected to the adverse impact of some proposals on the

level of integration previously achieved. This impact was caused

by abolishing some pairings and eliminating some satellite areas

to create more neighborhood walk-in schools. Plaintiffs

presented an alternative plan which would have avoided these

results. The opinion makes clear that acceptance of the

Consensus Plan was temporary and reluctant:

10 That finding was fully supported, see, e.g.. PX-111, 112,

113, 164, 167 (1982) as to the effect on elementary schools.

"In this case, I am now accepting the

modified consensus plan for the single school

year of 1982-83. I do so with considerable

reservation because I am not convinced that

the incumbent school board has shown a com

mitment to the creation of a unitary school

system which will have adequate capacity for

the delivery of educational services without

racial disadvantages......... Acceptance of

this plan for a single school year is not to

be construed as an abdication of this court's

authority and responsibility to compel com

pliance with the desegregation mandate." 540

F.Supp. at 403.

The Board did not appeal.11

The Ruling On The Language Complaint - December 1983. The

court next considered as an ancillary matter the supplemental

complaint of the plaint iff-intervenors Congress of Hispanic

Educators regarding the failure to provide appropriate education

for limited English language proficiency children. After a two

week trial, the court on December 30, 1983 issued a Memorandum

Opinion and Order On Language Issues, 576 F.Supp. 1503 (D. Colo.

1983). In holding that the District violated plaintiff-

intervenors' rights under 20 U.S.C. S1703(f), the court noted

the interrelationship of the required remedy with desegregation:

In sum, the issues which have been brought

before the court by the plaint iff-intervenors

are part and parcel of the mandate to estab

lish a unitary school system.

11 The Board's pleading at the outset of the 1982 hearings had

requested a declaration that the district was unitary, and estab

lishment of a timetable for relinquishment of jurisdiction.

Accordingly, no discrete remedy for these

issues will now be ordered, but the school

district has the responsibility for imple

menting appropriate action as a part of com

pliance with the mandate to remove the

effects of past segregative policies and to

establish a unitary school system in Denver,

Colorado. 576 F. Supp. at 1521.

* * *

A failure to take appropriate action to

remove language barriers to equal participa

tion in educational programs is a failure to

establish a unitary school system." Id. at

1522.

Once again the Board did not appeal. Subsequently

plaintiff-intervenors and the Board negotiated a language consent

Decree, which was accepted by an Order dated August 17, 1984.12

Events Leading Up to The 1984 Hearings. In late 1982 the

court appointed three expert witnesses (Compliance Assistance

Panel) to advise the District on how to complete and maintain

desegregation.13

In the spring of 1983 the Board asked for a one year exten

sion of the Consensus Plan while it planned assignment revisions.

On April 15, 1983, the Court granted the one-year extension.1*

12 The remedy, to be phased in over a period of several years,

was entitled "A Program For Limited English Proficient Students".

See Add. at 125.

13 See Order To Show Cause Concerning The Appointment Of A Com

pliance Assistance Panel dated November 2, 1982. Findings, Con

clusions And Order Appointing Compliance Assistance Panel, dated

December 16, 1982.

l* See Transcript of April 15, 1983 hearing.

-7-

Resolution 2193, submitted by the Board in support of the

one-year extension, stated in part:

WHEREAS, maintenance of the present Pupil

Assignment Plan for a period of one year,

with some modifications therein, will provide

the necessary stability of assignment and

time necessary for the Board, the parties and

the Compliance Assistance Panel, to properly

evaluate proposals for pupil assignments and

programs designed to ensure the provision of

equal educational opportunities; and

WHEREAS, the School District is actively

engaged in the planning necessary to develop

appropriate guidelines for Pupil Assignment

Plans for subsequent years.

In April 1983 the Board voiced no objection to the continu

ing jurisdiction. Its Hearing Memorandum of April 15, 1983 (PX

800) reassured the court of the Board's commitment to correct the

many resegregative effects of the Consensus Plan which were by

then apparent. However, shortly after the hearing the Board

secretly determined that it would submit no further plans. 609

F.Supp. at 1505. To pursue this secret agenda, the Board hired

new co-counsel and began to assemble evidence to support the

position that the District already was a unitary system and that

the court had no authority to continue jurisdiction. Ibid. The

Board treated the Panel as an "interloper" and rebuffed or

ignored its efforts. Ibid.

The Board finally revealed this new stance in December,

1983, followed by a motion dated January 19, 1984. This was less

than 20 days after the court, in the Language Opinion, had ruled

that the District was still not unitary. Nevertheless, the motion

sought an order:

(1) declaring that the District is unitary as to

faculty, staff, transportation, extracurricular activities,

facilities and composition of student body;

(2) modifying and dissolving the injunction as it

relates to student assignments;

(3) declaring that the previously ordered remedy to

correct the constitutional violation has been implemented and

that there is no need for continuing court jurisdiction. The

District's other motion, to sever the language issues, was

denied.15

THE PROCEEDINGS BELOW

The 1984 hearings16 concluded on May 23, 1984. On June 3,

1985 the court issued its Memorandum Opinion And Order, 609

F.Supp. 1491 (1985).17 That opinion rejected the District's

claim that it was unitary and denied the request to dissolve all

15 See Order Denying Motion To Sever, dated January 20, 1984.

16 Prior to the commencement of the 1984 hearings, the court

granted the plaintiffs' motion to incorporate the evidence from

the 1982 hearings as part of the 1984 record.

17 The Brief implies judicial delay (p. 36), but the delay in

decision occurred because briefing was deferred by agreement

through the summer and fall of 1984 as the parties unsuccessfully

negotiated to settle the case.

pupil assignment injunctions. The court asked the parties to

renew settlement discussions. 609 F.Supp. 1522. On October 4,

1985 the parties reported their inability to settle. The court

then ordered the Board to file a plan dealing with four mat

ters: 1 a

(1) elimination of the resegregation of Barrett,

Harrington and Mitchell elementary schools which had been caused

by the Consensus Plan;

(2) Elimination of abuses in the hardship transfer

policies;

(3) Correction of faculty desegregation practices,

which had violated the Decree since 1974;

(4) Further details to provide assurances that future

school construction, utilization and planning decisions would not

reestablish the dual system.

The Board appealed from the October 1985 order and the

June 1985 opinion and order.

The Board's response to the October 1985 order was a plan

which was considered at a three day hearing in March 1986. The

court ruled that the Board could proceed with its plans in

September 1986 pending a written opinion, which was filed on

February 25, 1987. 653 F.Supp. 1536. Since the District had

18 Order For Further Proceedings of October 29, 1985. D.P.S.

Brief, Attachment.

chosen various subtle and untested methods to integrate the three

elementary schools through voluntary integration the court ruled

that it would await the results before making any final determi

nation. The court said that the Board should return to court

when it could demonstrate that its proposals had been implemented

and were effective. Plaintiffs' requests for further injunctive

relief were rejected, reserving them for further consideration if

the Board's plans proved ineffective. Id. at 1540.

The opinion also said that in the interim pending the

Board’s further presentation of evidence judicial supervision

over the district would be reduced by eliminating provisions

requiring prior court approval before changing pupil assignments

and school utilization. As many of the 1974 Decree's provisions

were outdated they should be eliminated or updated. The court's

plan was to relinquish jurisdiction of the case and enter a per

manent injunction when the Board proved the effectiveness of its

plans. Id. at 1540-41.

The court next considered the parties' positions on the

form of the amended injunction. They took strikingly different

approaches to the interim order. The Board wanted specific

detailed requirements and continuation of pre-approved pupil

assignment and related plan changes. The Board suggested that

the court fix a specific racial percentage guideline which would

trigger the need for prior court approval.19 The Board made

1 9 670 F. Supp. 1513 at 1515.

vagueness objections to plaintiffs' attempts to formulate princi

ples to govern the Board's conduct without the need for prior

court approval.20 Plaintiffs' suggestions were based on language

in the Supreme Court's Swann decision to give the Board substan

tive guidance about making plan changes without pre-clearance.21

The interim Decree was issued, Memorandum Opinion and Order,

dated October 6, 1987, 670 F.Supp.1513. The court noted that the

interim Decree, "removes obsolete provisions of existing orders,

relinquishes reporting requirements, and eliminates the need for

prior court approval before making changes in the District's

policies, practices and programs." 670 F.Supp. at 1515. Such

pre-approval was supposedly the Board's greatest objection to

continuing jurisdiction and the impetus for seeking relinquish

ment.22 The order supersedes all prior injunctions in the case

including the 1974 Decree. 670 F. Supp. at 1517. The Board is

no longer obliged to follow the Finger Plan or any particular

plan of pupil assignment. Rather the Board is directed to

achieve and maintain desegregation under the Decree's principles.

The Board's second appeal, (No. 87-2634) followed.

20 670 F. Supp. at 1515-16.

21 Swann v. Board of Education. 402 U.S. 1 (1971). The plain

tiffs' proposals were based on Part V of the Swann Opinion par

ticularly the language at 402 U.S. 26.

22 See 609 F. Supp. at 1517-18.

-12-

At a subsequent status conference about the hearing at which

the Board will show the results of its plan, the court scheduled

the hearing for after school opens in the fall of 1988. In fall

1988 the District will implement a new grade structure, whereby

all sixth graders will be assigned to middle schools rather than

elementary schools and third graders in paired schools will be

shifted to the school containing grades four and five. 23 If

the Board makes a satisfactory showing, the court plans to

formulate a permanent injunction and end active jurisdiction. 2<f

RESTATEMENT OF FACTS

Our summary of evidence concentrates on four reasons the

Court held that the District was not unitary: (1) the Board's

resegregation of three elementary schools, (2) abuse of the

parent-initiated pupil transfer policy, (3) building utilization,

construction and abandonment, and (4) faculty integration.25

The History Of Integration And Reseqreqation At Barrett.

Harrington And Mitchell Elementary Schools. Barrett, Harrington

and Mitchell elementary schools were virtually all-black when the

23 A report showing that the changes will be implemented at the

beginning of the 1988-89 school year, and providing projections

as to the results as to school enrollments, was filed on May 12,

1988.

21* 653 F. Supp. at 1541-42. See Transcript of Pretrial Confer

ence, November 13, 1987, Add. at 154-168.

25 Order for Further Proceedings, Oct. 29, 1985 at pp. 1-2.

case began in 1969. They are located in Denver's black ghetto.

Barrett was deliberately located, and its zone gerrymandered, to

make it segregated. Mitchell and Harrington are nearby in the

core city area.26

These schools were desegregated by pairing with Anglo

schools in 1976.27 These 1976 arrangements continued (with minor

changes in 1979) through the 1981-82 school year. During this

time Barrett and Harrington remained successfully integrated, and

Mitchell — with a 22.5% Anglo student body was only slightly

below the plan's target range.

The implementation of the Consensus Plan in 1982 changed

these three schools back to heavily minority schools. (PX 610,

cf. PX 2155) The Board advanced no educational justification for

these changes. By 1984 these schools had the smallest Anglo per

centages in the system. PX 2110.

Barrett. The Consensus Plan changed Barrett from 43% Anglo

in 1981 to 22.8% in 1982. Under the Plan the predominately white

satellites were removed from Barrett. Knight became a magnet

school and was no longer paired with Barrett. Barrett received a

26 The Supreme Court opinion contains a map showing the loca

tion of these schools, and summarizes Judge Doyle's findings.

Keyes v. School District No. 1.. 413 U.S. 189 (1973).

27 Barrett was paired with Knight; it also received pupils from

a predominately-white satellite area. Harrington was paired with

Ellis. Mitchell, the largest minority school, was in a triad

with Denison and Force.

new pair, Cory. Before implementation the Board had projected

the 1982 enrollment at Barrett to be 37% Anglo. (PX 735) Subse

quently the Anglo enrollment drifted lower: 18% in 1983, 13.5%

in 1984 and 16% in 1985.28

Harrington. The Consensus Plan changed Harrington from 26%

Anglo in 1981 to 15.5% in 1982. Under the Plan predominately-

minority Wyatt school was closed and its children reassigned to

Mitchell and Harrington, while a portion of Harrington was

assigned to Smith. Subsequently the Anglo enrollment remained

low:14.9% in 1983; 16.2% in 1984 and 19.5% in 1985.

Mitchell. The Consensus Plan changed Mitchell from 22.5%

Anglo in 1981 to 17% in 1982. Under the Plan, Denison was

removed from the triad and closed. Most of its predominately

white pupils were reassigned to Doull which was removed from the

plan and became a K-6, walk-in predominantly white neighborhood

school. The rest of the Denison pupils were reassigned to the

new Mitchell-Force pair. Anglo enrollment at Mitchell was 15.8%

in 1983, 16.7% in 1984 and 16.9% in 1985. The Plan changed Force

to a 22.7% Anglo school, down from 33.5% in 1981.

The court found that it was the Consensus Plan effort to

reduce "forced busing" which resegregated the three schools:

28 The enrollment history of Barrett, Harrington and Mitchell

is detailed in PX 2100. Anglo percentages in the text exclude

kindergarten. See PX 2130 for 1985 elementary enrollments.

The evidence now before the court shows that

the plaintiffs' objections and the court's

concerns about the Consensus Plan were well

founded. Barrett and Harrington have become

racially identifiable schools, . . . Mitchell

fell from 22.5% to 12% Anglo. 609 F.Supp. at

1507. [12.8% in 1982, includes kindergarten.

PX-2100]

After hearing an extensive factual presentation, the court

expressly found against the District's claim that these three

schools had become resegregated because of population movements.

The court analyzed a "vast array of statistical data and expert

opinion" before finding against the District's contention:

"This court is not persuaded that demographic

change is the reason for the development of

racial imbalance in the schools." 609

F.Supp. at 1508. See also id. at 1517.

In its 1986 opinion, the court reiterated that: " . . . the

Consensus Plan had resegregative effects on Barrett, Harrington

and Mitchell schools." 653 F.Supp. at 1540.29 The history of

these schools, set out in PX-2100 at the 1986 hearing, was undis

puted; the court's resolution of the dispute over the cause of

the resegregation and rejection of the Board's "white flight"

explanation was supported by credible evidence.30

29 In the Order for Further Proceedings, but not in its 1985

opinion, the court had erroneously stated that Barrett and

Mitchell had never been integrated; the error was recognized and

corrected in the 1986 opinion, 653 F.Supp. at 1540, fn 1.

30 PX-2100. Testimony as to cause was presented through

Drs. Bardwell and Stolee at the 1984 and 1986 hearings. See

Stolee 1986 R.Vol. Ill at 193; Bardwell re PX-2100 at Id.,

131-33.

Remedial Proposals For Barrett, Mitchell and Harrington.

The components of the Board's proposals which were implemented in

fall 1986 are set out in DX-B(86), D.P.S. Add. at 193-214.31

The Board eschewed any changes of Consensus Plan zoning or

pairings to increase integration at the three schools. It

asserted that the schools could be integrated by using various

subtle techniques to influence Anglos to attend these ghetto

schools. One method was simply improving the physical facilities

and appearance of the three schools (including planting grass,

carpeting, painting and maintenance) to make them comparable to

Anglo schools and thus attractive to the Anglos who, it was

hoped, would volunteer to attend. Ld. at 198, 208, 212.

Equally revealing was the fact that a major element of the

Board's own plan was to require Anglo pupils who lived in the

zones of these schools to actually attend them by stopping the

abuses of the parent-initiated pupil transfer program by which

many white children transferred out to Anglo schools under liber

ally granted "baby-sitting" excuses. The plan for each school

was for "Implementation of the [new] adopted transfer policy and

the monitoring of transfers to insure that they do not have a

31 Through Dr. Stolee, plaintiffs presented plans based upon

mandatory reassignments to restore integration at the three

schools. See PX-2030, pp.3-6, the offer of the mandatory plans

at 1986 R. Vol. Ill at 204-05, and on cross-examination, Ld. at

209-12. The court found that these proposals could "easily"

remedy the problem. 653 F. Supp. at 1540.

negative impact on the racial composition of the school." D.P.S.

Add. at pp. 204, 209 and 212.

By such other measures as enhanced educational programs at

Barrett and Harrington and the adoption of a one-grade-a-year

plan to establish a Montessori school at Mitchell,32 the Board'

plan proposed to control the racial composition of the three

schools and restore integration without mandatory assignment

changes.

The court allowed the implementation of these plans to see

if they would prove to be effective:

"This court cannot determine the effec

tiveness of the programs for increasing the

Anglo population at Barrett, Harrington and

Mitchell Schools from the evidence at the

March, 1986 hearing. . . . It is precisely

because the Board has selected the more

subtle methods for inducing change that this

court must retain jurisdiction to be certain

that those methods are effective." 653

F.Supp. at 1539, 1540.

This record does not indicate the results of the imple

mentation of the Board's plan in 1986 and 1987. The 1988 fall

hearing will consider that as well as the change of the transfer

policy discussed below.

32 The Montessori program called for the establishment of pre

kindergarten and kindergarten in 1986, and a grade a year there

after. Thus implementation will not be complete (grades pre-K

through 5), until 1991. As each Montessori grade is established

at Mitchell, the pupils in that neighborhood who do not elect to

participate are assigned to Force. There was concern expressed

through plaintiffs' evidence that the plan would cause Force to

become segregated. No remedy for this problem has been put in

place. See Stolee, 1986 R.Vol. Ill, at 200-01.

The Reseqreqative Effect Of The Baby-Sitter Transfer Policy.

The Board's policy allowing parent-initiated transfers has been

in effect since 1974, but first came under scrutiny at the 1982

hearing. 33 Under the policy elementary pupils could change

their school of assignment simply by retaining a baby-sitter

within the attendance area of the school of their choice; at the

secondary level the vehicle was the location of after-school

jobs. The District made no effort to determine the effects of

individual transfer requests upon the transferee or transferor

school, or to prevent use of transfers to thwart desegregation.

609 F.Supp. at 1512, 1514. After reviewing plaintiff's study of

the transfers' effects at the 1984 hearing3*' the court concluded;

33 At the 1982 hearing, plaintiffs were only able to demon

strate possible adverse impacts at Mitchell. PX-330 (1982). The

state of the "records" of transfers was described by Martha

Nelson, 1982 R.Vol. 19 at 119-122. The lack of monitoring or

analysis was admitted, Id. at 122-23, as was the ease in picking

the transferee school by finding a sitter in that area, .Id. at

125. Similar manipulation was available at the secondary level

through selection of the location of after-school jobs. .Id. at

125-27. See also PX-110 (1982), showing that hardship and

babysitting accounted for 212 of 352 children excused from

satellite areas.

34 At the 1984 hearing plaintiffs demonstrated that in the

single school year 1983 transfers had substantially affected

Anglo percentages in seventeen elementary schools, including

Barrett, Harrington and Mitchell. PX-720, 730 (1984). Of the 12

schools whose Anglo enrollment had dropped due to transfers, all

were former minority schools. Ibid. See Bardwell, 1984

R.Vol. 13, at 1148-59; Stolee, 1984 R.Vol. 14 at 1230-33.

The 1974 Decree appears at D.P.S. Add. at 1-17. Paragraph 8

of the Decree provided that parent requested transfers, when fea

sible, "shall be made to improve integration at the transferee

"Yet the fact that the schools with the

largest net changes are the schools which

have historically been the racially

identifiable schools is some evidence that

for those schools the hardship transfer may

have been used to avoid the desegregation

plan.

The District has done the minimum required in

keeping records and maintaining the policy

that it would refuse a transfer if the

express reason given was "race". The dis

trict has failed to monitor the system-wide

effect of the transfers, leaving the decision

to the principal of the receiving school. In

fact, prior to the 1982 hearing, no record of

ethnicity was kept in the central card filing

system. The plaintiffs’ analysis of 1983-84

transfer data appears to be the first such

system-wide analysis, and it does reveal that

the effects of such transfers in certain

schools are significant and are contributing

to the racial identification of those

schools. In addition, the schools affected

are some of the schools initially at issue in

this lawsuit." 609 F. Supp. at 1513-14.

(Footnote Continued)

school," and required record-keeping. Add. at 6. In paragraph

18(9), semiannual reports on transfers were required. The spirit

if not the letter of these requirements were violated. 1984

R.Vol. 14, Stolee at 1233. The president of the Denver P.T.A.

testified as to the demoralizing effect of these transfer abuses

upon the parents whose children complied with the Decree. Ruckle,

1984 R.Vol. 18 at 155-56.

Martha Nelson, who continued to administer the program in

1984 (and in 1985 as well), testified that despite the potential

for abuse and the inadequacies disclosed at the 1982 hearing,

there had been no substantive change in the policy or record

keeping. Transfers were still not assessed as to their

segregative effect. No transfer request had ever been rejected

due to its segregative effect. 1984 R.Vol. 18 at 211-219.

At the 1986 Hearing the Board finally presented a revised

transfer policy and promised to allow transfers only in cases of

genuine necessity. See DX-D(86), D.P.S. Add. at 215-18. Imple

mentation of the new policy was to be for the 1986-87 school

year.35 The Superintendent stated that this tightening of the

policy was an important component of improving Anglo enrollments

at Barrett, Mitchell and Harrington; this admission was confirmed

by the schools' principals who testified as to their individual

ized efforts to recapture Anglo families abusing the system.36

Plaintiffs' evidence showed the continuing adverse impacts

upon the desegregation program.37 Over 10% of all elementary

pupils (2,869 children) were avoiding attending their schools of

assignment under the desegregation plan.38

35 Superintendent Scamman admitted that the data base available

to Mrs. Nelson was inadequate to measure the cumulative effect of

transfers in the 1985-86 school year. 1986 R.Vol. I at 107-08.

Details of the policy's application to transfers based upon

academic programs were unknown. M. at 99-103. Monitoring and

analysis of transfers would not be in place until the 1986-87

school year. Id. at 40-41.

36 Dr. Scamman's testimony appears in 1986 R.Vol. I at 65-66,

133-34, 141-42. That of Barrett principal Hazzard, _Id. at 184,

197-201; of Harrington principal Santorno, Id. at 231-32, 252; of

Mitchell principal Urioste, 1986 R.Vol. II at 42-46,55-56.

37 See Bardwell, 1986 R.Vol. Ill at 119-30, PX-2176,2095;

Stolee, Id. at 168-85, PX-2035, 2041, 2055, 2060, 2065. The list

of schools whose Anglo enrollment had been significantly affected

had grown to 40; of those, 29 were moved farther away from the

district-wide average due to transfers. Dr. Stolee concluded

that these transfers were having a segregative effect. Id. at 182

83.

38 The percentage was even higher for Anglo elementary pupils.

1986 R.Vol. Ill at 119-20 (Bardwell) PX-2176, p.4. Barrett and

The court credited this evidence,39 and noted that the new

policy was focused only on the impact of the transfer at the

receiving school, and concluded that, "only carefully monitored

implementation of [the new policy] will indicate whether it

effectively prevents circumvention of the pupil assignment plan."

While the court concluded that, "the defendants have not demon

strated that the new transfer policy . . . will produce the

required results," implementation was nevertheless allowed to

determine whether it would work. 653 F.Supp. at 1540, 1542.

Evidence Relating To Building Utilization. School Construc

tion And Abandonment And Pupil Assignment Practices. Here we

focus on the evidence underlying the court's concern that the

District's policies and practices relating to building

utilization, school construction, the closing of schools and

pupil assignment might result in resegregation of the schools.

This concern was rooted in the history of the violation in this

case, where these policies and practices were found to have been

the tools for intentional segregation.

(Footnote Continued)

Mitchell remained among those minority schools with the largest

declines in Anglo enrollment due to transfers. Id. at 127-28,

PX-2095.

39 See 653 F.Supp. at 1538.

-22-

The evidence throughout the remedial phases of the case

reflects the fact that the black ghetto upon which the District

built its segregated system still remains intact today.40

As detailed above, in three successive presentations to the

court, the Board failed to demonstrate that it would use its

policies of school utilization and abandonment to advance or pre

serve desegregation. Its 1979 proposals were rejected, as was

the "irresponsible” Total Access Plan in 1982. 653 F.Supp. at

1540. The Consensus Plan was accepted only temporarily and

reluctantly. 540 F. Supp. at 403. Less resegregative alterna

tives were available.41

Seeing these continued failures, the court appointed the

Compliance Assistance Panel to assist the Board in developing

plans and policies to assure the establishment and maintenance of

a desegregated system. However, the Board, during the spring and

sxammer of 1983 turned its back on this assistance.

Instead, the Board declared that the District was already

unitary and attempted to set forth its future commitment to main

taining integration in Resolution 2233. Resolution 2233 was

40 See 653 F.Supp. 1536, 1541. While blacks and Hispanics have

moved to some extent into formerly all-white neighborhoods, a

corresponding migration of whites into the ghetto has not

occurred, and they remain unchanged in their concentrations of

minority families. See also 609 F.Supp. at 1519, 1520.

41 See Stolee, 1982 R. Vol. 15 at 1-62.

passed by the Board on the eve of the 1984 hearing seeking a dec

laration of unitary status.42 The Resolution was a document pre

pared by lawyers for the litigation; it was based on no input

from the staff and little input from the Board.43 It was obvi

ously meant to track the resolution which the Ninth Circuit had

found convincing in the Spangler case.44

At the hearing the plaintiffs' evidence was that the resolu

tion was too vague to be meaningful,45 and it implied a program

the ultimate objective of which would be a return to neigh

borhood, segregated schools.46 Despite misgivings the court

accepted Resolution 2233 as official Board policy, (653 F.Supp.

at 1540) and determined to let them prove its bona fides by their

actions under relaxed judicial supervision. See 670 F.Supp.1513,

1516:

42 DX C-6, DPS Add. at 171.

43 Testimony of Board member Mullen, 1984 R.Vol. 15 at 1268.

44 See discussion 609 F.Supp. at 1514, 1518-1520.

45 See testimony of Dr. Willie, 1984 R.Vol. 21 at 51-58.

46 609 F.Supp. at 1520; see testimony of Dr. Hawley, 1984

R.Vol. 20 at 381-93. In reviewing PX-845 (1984), he noted a sim

ilarity between the Consensus Plan's approach and the approach of

Resolution 2233.

See also Schomp, 1984 R.Vol. 18 at 114; Mullen, 1984

R.Vol. 15 at 1269-75; Schroeder, .Id. at 1305; the day he voted

for Resolution 2233, Mr. Schroeder on a radio talk show agreed

that school integration was "unconstitutional", PX 880 (tape

recording), 1984 R.Vol. 21 at 21, and that anyone who mandated

. . . that your child must really have to go across town was out

rageous. Id. at 24.

"What the District does in the operation of

its schools will control over what the Board

says in its resolutions."

Colorado Constitution "Anti-busing" Amendment. In its 1985

opinion the court recognized that even the best intentions under

Resolution 2233 would be nullified unless Colorado's "anti

busing" amendment was permanently enjoined.lf7 See 609 F.Supp. at

1518. Maintenance of integration in Denver without busing would

be impossible:

The total return to neighborhood schools

throughout the system under the residential

patterns which have existed and now exist

would inevitably result in the resegregation

of some schools particularly at the elemen

tary level." Id. at 1519.*8

The interim Decree, 670 F.Supp. at 1517, enjoins the amend

ment in paragraph 8.

*7 The 1974 Amendment is Colo. Const. Art.IX, § 8:

No sectarian tenets or doctrines shall ever ■

be taught in the public school, nor shall any

distinction or classification of pupils be

made on account of race or color, nor shall

any pupil be assigned or transported to any

public educational institution for the pur

pose of achieving racial balance. (Emphasis

added).

This provision would even prohibit transportation for the

voluntary integration efforts purportedly supported by the Board.

*8 This conclusion was clearly supported by the plaintiffs'

"nearest school" evidence introduced in opposition to the Total

Access Plan in the 1982 hearings, PX-111, 112, 113, 167 (1982)

and credited by the court, 540 F.Supp. at 402.

Faculty Segregation and Desegregation. In the June 1985

Opinion Judge Matsch found that the District had never complied

with paragraph 19A of the 1974 Decree regarding faculty assign

ments. 609 F.Supp. at 1508-1512. Rather the District had

"adopted the interpretation which requires the fewest minority

teachers in schools which previously had a predominantly Anglo

faculty". Id. at 1509. Thus the District had perpetuated the

old pattern and failed "to remedy, as much as possible, the prior

practice of assigning Black teachers to Black schools as 'role

models'." Id. at 1510. (PX 710) Judge Matsch found the Dis

trict never adopted guidelines for determining when minority

schools had too many minority teachers. 609 F.Supp. at 1510.

Judge Matsch's review of the evidence resulted in a finding that:

The schools with a high percentage of minor

ity teachers are, in large part, the same

Park Hill and core city schools identified by

the Supreme Court in Keyes. 413 U.S. at

192-193 nn. 3,4 . . .. Comparing the loca

tion of the listed school with its percentage

of minority teachers and the minority resi

dential patterns in Denver, reflected in the

census data maps submitted by the District,

it appears that the concentration of minority

teachers in the schools is correlated to mi

nority residential patterns. 609 F.Supp. at

1511.

The District had retained its "neighborhood teacher policy."

After reviewing the extensive evidence and testimony

presented by plaintiffs on faculty assignment patterns,*9 and

The findings are supported by substantial testimony and

exhibits. See Dr. Stolee, 1984 Vol. 14 at 1233; Dr. Bardwell,

after rejecting the District's arguments on the subject as being

made "somewhat disingenuously" (.Id. at 1510), the court con

cluded:

From the totality of the evidence, this court

finds that the District has tended to inter

pret the Decree's mandate for minimum per

centages of minority teachers as the maximum

for schools with large Anglo enrollments and

has failed to place any maximum minority per

centages for the schools with large minority

pupil populations. The conclusion is that

there is a sufficient residue of segregation

in faculty assignments to deny a finding that

the District has been desegregated in that

respect. 609 F.Supp. at 1512.

ARGUMENT50

I. The findings and record abundantly support the injunctions

in effect from 1976 until October 1987 and the retention of

jurisdiction during that period.

A. The Board's arguments about the previous injunctions

are without merit because of mootness, untimeliness and waiver or

acquiescence. The Board argues that since 1976, the court has

(Footnote Continued)

1984 Vol. 13. at 1116, 1126, 1129 (PX 711), 1135, 1137-1139, 1146

(PX 719). See Dr. Willie, 1984 Vol. 21 at 44-51. See also

PX 685, 700, 705, 718, 719 (1984).

Standard of Review: District courts in school desegregation

cases have broad discretion under traditional equity principles

to formulate injunctions and retain jurisdiction. Swann v. Board

of Education. 402 U.S. 1, 15-18 (1972). Abuse of discretion is

the standard of review. Battle v. Anderson. 708 F.2d 1523, 1539

(10th Cir. 1983). See infra. Argument 1(G). Fact findings are

reviewed under the "clearly erroneous standard." Review of legal

conclusions is plenary.

-27-

had no power to enter injunctive orders or to retain jurisdic

tion, because a court-ordered desegregation plan was implemented

in September 1976. The Board's complaints about the injunctions

in effect before October 6, 1987, which have now been superseded,

are moot. The complaint about retention of jurisdiction under

the earlier orders is also moot, as the current relaxed judicial

supervision is different from that prior to October 6, 1987.

The Board's complaints about the 1987 injunction and

retained jurisdiction remain for consideration. We answer the

attacks on the moot orders in detail because findings and argu

ments supporting those orders also support the 1987 Decree.

There are two other procedural bars to the Board arguments,

e.q. timeliness and waiver or acquiescence. The complaints that

the court erred by continuing to issue injunctions in 1979, and

1982 are untimely. There were no timely appeals when those

injunctions issued. The Board did not discover or assert its

position until years later.

By its conduct from 1976 through 1983 the Board acquiesced

in the court's continuing jurisdiction. Principles of waiver and

estoppel should preclude the Board from complaining about juris

diction which was retained at the Board's own request and to

serve its purposes. The three-year moratorium on changes in the

plan — approved at the board's suggestion — necessitated con

tinuing jurisdiction from 1976 to 1979. If the Board had wanted

termination of jurisdiction in the fall of 1976 it could have

reported the plan results to the court and sought a hearing.

Instead the Board sought a three year delay because it could

thereby avoid the risk that the court would find the plan inade

quate and order changes. From 1979 to 1981 the Board made no

request that the court's supervision be ended. Instead the court

was led to await the work product of the Ad Hoc Committee which

was charged to develop guidelines and long term plans for a

unitary system. Even in April 1983 (after rejection of the Total

Access Plan and the one-year approval of the Consensus Plan) the

Board obtained a one year extension of the Consensus Plan by rep

resenting in a pleading that it would cooperate with the Compli

ance Assistance Panel and prepare a plan to satisfy the Court's

reservations about the Consensus Plan. Thus from 1976 through

1983 the defendants never raised the present claim (advanced for

the first time in early 1984) that the entire remedial proceeding

since 1976 has been ultra vires. The court was entitled to prem

ise its 1985 orders on earlier orders (such as the 1982 order)

which had never been challenged or appealed by defendants. The

Board misplaces the blame in accusing the court of a "bootstrap

theory of federal judicial power" (Brief at 18) where the Board

did not challenge or appeal the earlier exercises of that power.

When the court addressed unitariness in the June 1985 opin

ion it set forth several solid grounds for rejecting the Board's

position. Two of the most significant grounds relied on by the

trial judge are not even challenged on appeal. The Board's brief

concedes the validity of the court's findings "regarding teacher

assignment and hardship transfers". Brief, p.2,n.5. This

concession is also a waiver by the Board, and the concession is

fatal to the Board's entire argument against the pre-1987 injunc

tions and retained jurisdiction. The Brief requests a remand for

the court to consider whether there was "good faith imple

mentation," whereas the appropriate review is as to the effec

tiveness of the Board's 1986 plan. Brief p.36, 49. But an

appeal for that remand is entirely superfluous because the court

has already repeatedly stated his plan to conduct that hearing on

effectiveness when the Board is ready to make the required

showing. See 653 F.Supp. at 1540; 670 F.Supp. at 1515; Tr.

Pretrial Conf. Nov. 13, 1987, Add. at 154-168.

B. The findings of transfer abuses supported injunctive

relief and retained jurisdiction. The court's finding that the

Board permitted parents to abuse the "babysitting" transfer

option to undermine the desegregation plan at racially

identifiable minority schools which were involved in the original

violation provides a solid basis for continued injunctive relief

and equitable jurisdiction. The Board allowed ten percent of all

elementary children to transfer without any control to prevent

transfers from defeating the desegregation plan. The Board's own

presentation in 1986 made it clear that preventing abuse of the

transfer device could go a long way toward integrating Barrett,

Mitchell and Harrington schools.

The Board argues as if these transfers were entirely

unrelated to "pupil assignments." But transfers are "pupil

assignments" approved by school authorities. The findings of

significant transfer abuses which undermined the desegregation

plan provided a solid basis for the 1985 orders.51

C. The findings on faculty segregation supported

injunctive relief and retained jurisdiction. The finding that

the Board had violated the faculty desegregation order since 1974

also supports the 1985 orders. The Board argues the case as if

faculty assignments had no relation to or effect on pupil assign

ments. In Denver the Board's pupil assignment rules which per

mit children to choose their schools (e.g. magnet programs,

transfer options) provide a special reason why schools must not

be racially identifiable by the race of their faculties. The

Board's continuing unlawful practice of assigning faculties to

correlate with residential segregation patterns and the historic

racial identification of the schools, (609 F.Supp. at 1511), had

51 Columbus Bd. of Ed. v. Penick. 443 U.S. 449, 461 (1979);

Dayton Bd. of Ed. v. Brinkman. 443 U.S. 526, 535 (1979); Adams v.

United States, 620 F.2d 1277, 1290 (8th Cir.), cert, denied. 449

U.S. 826 (1980); N.A.A.C.P. v. Lansing Bd. of Ed.. 559 F.2d 1042,

1050-51 (6th Cir. 1977).

-31-

the obvious potential to influence Anglo acceptance of the paired

school and pupil choices about those schools. At Barrett,

Harrington and Mitchell Anglos would not be persuaded if black

teachers were still concentrated there as role models for black

pupils. The purpose of faculty integration is to assure that

Denver operates "just schools" and not "white schools" or "black

schools." Swann, supra, 402 U.S. at 18; United States v.

Montgomery County Board of Ed., 395 U.S. 225 (1969); Green v.

School Board. 391 U.S. 430, 442 (1968). Here faculty integration

is so closely related to the pupils that it could not be error

for the court to retain jurisdiction of. pupil assignment issues

when it found the faculty order had been violated for a decade.

D. The duty to prevent re-establishment of the dual system

by construction and abandonment policies supports the retention

of jurisdiction. The trial judge found another basis to reject

the Board's argument that the 1976 order completed the remedy.

He ruled (609 F.Supp. at 1506) that the 1974 and 1976 orders had

failed to provide a mechanism to address a specific command of

the Supreme Court in Swann:

In devising remedies where legally imposed

segregation has been established, it is the

responsibility of local authorities and dis

trict courts to see to it that future school

construction and abandonment are not used and

do not serve to perpetuate or re-establish

the dual system. When necessary, district

courts should retain jurisdiction to assure

that these responsibilities are carried out.

402 U.S. 1, 21 (emphasis added below).

The quoted language concluded an important discussion in

Swann which emphasized that decisions about construction and

utilization, "when combined with one technique or another of stu

dent assignment, will determine the racial composition of the

student body in each school in the system." 402 U.S. at 20.

Judge Matsch has always kept in mind that official decisions made

by school authorities ultimately control the racial composition

of the schools. The 1985 opinion held that the Board had failed

to adopt adequate programs and policies to insure that these

decisions about school utilization would not re-establish segre

gation. 609 F.Supp. at 1506, 1514-21. The court cites Battle v.

Anderson. 708 F.2d.1523, 1538 (10th Cir. 1983), cert, dismissed.

465 U.S. 1014 (1984), which cites Green v. County School Board.

391 U.S. 430 (1968) as precedent for the duty to exercise super

visory power "until it can say with assurance that the unconsti

tutional practices have been discontinued and that there is no

reasonable expectation that unconstitutional practices will

recur. n 5 2

E. The finding that the Consensus Plan needlessly

reseqreqated Barrett, Mitchell and Harrington supported the 1985

The February 1987 opinion cites this Court's recent language

that "the purpose of court-ordered school integration is not only

to achieve, but also to maintain a unitary school system."

Dowell v. Board of Education. 795 F.2d 1516, 1520, cert, denied.

___ U.S. ___ (1986). Keyes. supra. 653 F.Supp. at 541.

-33-

orders. The court ordered the Board to devise new plans for

these three schools because it found that they had been need

lessly resegregated by the Board in 1982. The Court held that

its prior reluctant and temporary approval of the Consensus Plan

was a mistake and that plaintiffs' objections had been correct.

Plaintiffs demonstrated that it was feasible to maintain integra

tion at the three schools with their own proposals at the 1982,

1984 and 1986 hearings. The Board presented no justification for

the zoning and pairing changes that resegregated them except its

preference for "walk in” schools and opposition to "forced

busing." The decision to require new plans fulfilled the obliga

tion to achieve "the greatest possible degree of actual

desegregation, taking into account the practicalities of the sit

uation." Davis v. School Commissioners of Mobile. 402 U.S. 33,

37 (1971); Swann, supra 402 U.S. at 26.

The court found it unnecessary to decide plaintiffs' conten

tion that the Consensus Plan showed "segregative intent" by

defendants. 609 F.Supp. at 1507. The defendants have no valid

complaint that the court did not reach this question but instead

evaluated the effectiveness of the Consensus Plan under the

affirmative duty standards of the Swann and Davis. See Dayton

Board of Ed.. supra. 443 U.S. at 538 (Dayton II) and Columbus

Board of Ed.. supra; "Each. . .failure to fulfill the affirma

tive duty [violates]. . .the Fourteenth Amendment." 443 U.S. at

Further relief for the three schools was also supported by

the uncontested findings of transfer abuses for which the Dis

trict was fully responsible. These abuses significantly contrib

uted to the racial isolation of these schools by allowing Anglos

to move from Mitchell, Barrett and Harrington to Anglo schools.

653 F.Supp. at 1538; PX 2030, PX 2095, PX 2060.

The Board's brief attacks a "straw man" by attributing to

the court a purpose to correct racial imbalance resulting from

demographic changes for which the Board had no responsibility.

The trial judge found otherwise.53 609 F. Supp. at 1508, 1517.

The court's order required relief only to repair damage done by

the Consensus Plan. The Board's argument ignores the court's

explicit findings which rejected the Board's contention that

"demographic changes" were the cause. Id.

Moreover, the Board's claim about "demographic changes" is

fatally undermined by its own 1986 evidence that these three

schools could be much more integrated without any use of manda

tory means by stopping transfer abuses, and by improving their

53 The court has repeatedly stated it would not require any

particular racial balance or percentage and recognized the hold

ing of Swann on that point. See 474 F.Supp. at 1269; 540 F.Supp.

at 402; 609 F.Supp. at 1521. The District's schools have a wide

range of racial compositions. In 1983 (the year considered by

the opinion) there were actually six schools between 10 and 19%

Anglo. PX. 671, 650. The Consensus Plan created a number of

other racially identifiable schools. Compare PX-164 (1982) with

PX-631 (1984).

-35-

comparability, making them more appealing to the Anglo pupils who

lived in their zones.

F. The need to avoid conflict between desegregation reme

dies and the language consent decree supports the retention of

jurisdiction during implementation of the language plan. Nothing

in the Board's brief challenges the need of the court to retain

jurisdiction during implementation of the language consent

decree. This appeal does not affect the District's obligations

under that decree, or present any issue about how long jurisdic

tion of the language issues should be retained.

However, the language decree does support retained jurisdic

tion of desegregation issues. The court below refused to sever

the statutory language claim from the desegregation case because

of the need to coordinate the remedies. Two examples:

(1) The language decree provided for the employment and

assignment of over 100 new teachers in September 1985 (1986 R.

Vol. I at 25, 27); at the same time the Board was ordered to

desegregate faculties.

(2) The language decree provided for the placement of pro

grams for limited English proficiency children — many of them

Hispanic — at various schools over several years (id. at 28);

the desegregation orders have required that Hispanic pupils be

integrated.

It was simply common sense for the court to retain jurisdic

tion of the school desegregation issues while the language decree

was being implemented.

G. The court did not abuse its discretion in retaining

jurisdiction and in its management of the case. As Judge Matsch

noted, the Supreme Court placed the burden on the district courts

to supervise desegregation programs because of their "proximity

to local conditions." 609 F. Supp. at 1494, n.l. citing Brown v.

Board of Education. 349 U.S. 294, 296 (1955). The decisions of

trial judges, engaged in this difficult and time consuming pro

cess should not be lightly second guessed. Their judgment as to

discretionary matters should be respected. Swann, supra. 402

U.S. at 15-18. This Court held in Battle v. Anderson. 708 F.2d

1523, 1539-40 (10th Cir. 1983) that "abuse of discretion" was the

standard for review of a decision to retain jurisdiction in a

prison conditions case:

Absent a conclusion that the district court

has made clearly erroneous fact findings or

has abused its discretion, we have no author

ity to overturn its determination of the need

for continuing jurisdiction.

The opinions below, covering more than a decade of effort,

amply demonstrate the wisdom, patience and restraint of the dis

trict judge in handling this complex case. The judge has always

been appropriately respectful of the proper role of the elected

school board. There is not an iota of evidence in this

voluminous record that the court has improperly interfered with

the Board's educational policy decisions; rather he has encour

aged and supported every innovative educational proposal while

insisting upon effective desegregation. There is simply no basis

for a holding that he abused his discretion in retaining juris

diction over this case.

H. The decisions below are not in conflict with the

Spangler case.51* Both below and here the Board has placed prin

cipal reliance upon what Judge Matsch called "a very expansive

interpretation of the Supreme Court's Spangler opinion". 609 F.

Supp. at 1516. The Board's interpretation brushes aside numerous

important factual differences in the two cases. Spangler did not

involve findings that the district had caused resegregation by

its own decision to close and reorganize schools and partially

dismantle the pairing plan which created integration, or a plan

that had never been finally accepted by the court, or a district

that had allowed "baby-sitting" transfers to undermine its

desegregation plan, or a district that had disobeyed a faculty

desegregation order for a dozen years, or a district that

attempted to desegregate by persuading Anglos into ghetto

schools, or a district where desegregation was incomplete as to a

grade-a-year Montessori magnet school. All of the foregoing

5 * Pasadena City Bd. of Educ. v. Spangler. 427 U.S. 424 (1976).

factors are distinguishing aspects of the Denver case. While

Spangler was premised upon an effective plan subsequently changed

only by demographics, here the changes have been Board-initiated,

and, when ineffective, subject to further judicial review.

The Spangler decision does not hold that a brief period of

obedience to a desegregation decree deprives a court of power to

prevent a school board from scrapping its desegregation plan and

returning to the status quo ante. It would pervert equitable

principles to argue that a defendant is entitled to have an

injunction dissolved merely because it has been obeyed for a num

ber of years. That is not the rule of United States v. Swift &

Co.. 286 U.S. 106 (1932). A defendant must show more than mere

obedience to obtain relief from a permanent injunction. S.E.C.

v. Jan-Dal Oil & Gas. Inc.. 433 F.2d 304 (10th Cir. 1970); Dowell

v. Board of Education. 795 F.2d 1516, 1521 (10th Cir. 1986).

This Court rejected the contrary argument in Battle v. Anderson.

708 F.2d 1523, 1538, n.4 (10th Cir. 1983), invoking the familiar

principle that "the power to grant injunctive relief survives

discontinuance of the illegal conduct."55

55 United States v. W. T. Grant Co.. 345 U.S. 629, 633 (1953);

United States v. Oregon State Medical Soc., 343 U.S. 326, 333

(1952); City of Mesquite v. Aladdin's Castle, Inc.. 455 U.S. 283,

289 (1982); System Federation v. Wright, 364 U.S. 642 (1961).

II. The record and findings support the October 1987 injunction

and the limited retention of jurisdiction.

The Interim Decree superseded prior injunctions. It elimi

nated detailed plan requirements from the 1974 Decree but con

tinued injunction provisions based on Svann to require integra

tion of the school system. The findings and conclusions

contained in the four preceding opinions, which we have discussed

in Argument I, parts B to G, demonstrate the current need for

injunctive relief in the Denver schools. See Keyes. supra. 540

F.Supp. 399 (1982); 609 F.Supp. 1491 (1985); unreported Order for

Further Proceedings, October 29, 1985; and 653 F.Supp. 1536

(1987).

These findings and our arguments above amply demonstrate the

need for some form of injunction here. The opinions simply belie

the Board's contention that the court has found the system

unitary, as the determination that the District is not unitary as

to pupil assignment, and not ready for complete release from

supervision is abundantly supported. The Board's brief concedes

as much with respect to transfer abuses and faculty segregation.

The rulings on the three resegregated schools and the issue of

school abandonment and utilization similarly are based on well

supported findings and clear legal precedents.

The Board also concedes the need for injunctive relief

against Colorado's Anti-Busing Amendment which if unimpeded would

require that the remedies be dismantled. The Board correctly

states that the provision is unconstitutional (Brief pp.32-33)

and says that the concern "could" be met by a "declaratory judg

ment or injunctive provision." Id. That is tantamount to

conceding the propriety of paragraph 8 of the interim Decree.

The court has relaxed supervision of the desegregation pro

cess. The pre-clearance feature of retained jurisdiction — an

element of "supervision" by the trial judge — has been elimi

nated. The decision to give the Board more leeway at this time

was well within the discretion of the trial judge. The judge

thought this a necessary step toward a final decree wherein