Occidental Life Insurance Company of California v. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit

Public Court Documents

July 22, 1976

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Occidental Life Insurance Company of California v. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit, 1976. 7b57f81a-c09a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c2207979-80f4-484b-8245-b9ffa75132e4/occidental-life-insurance-company-of-california-v-equal-employment-opportunity-commission-petition-for-a-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-us-court-of-appeals-for-the-ninth-circuit. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

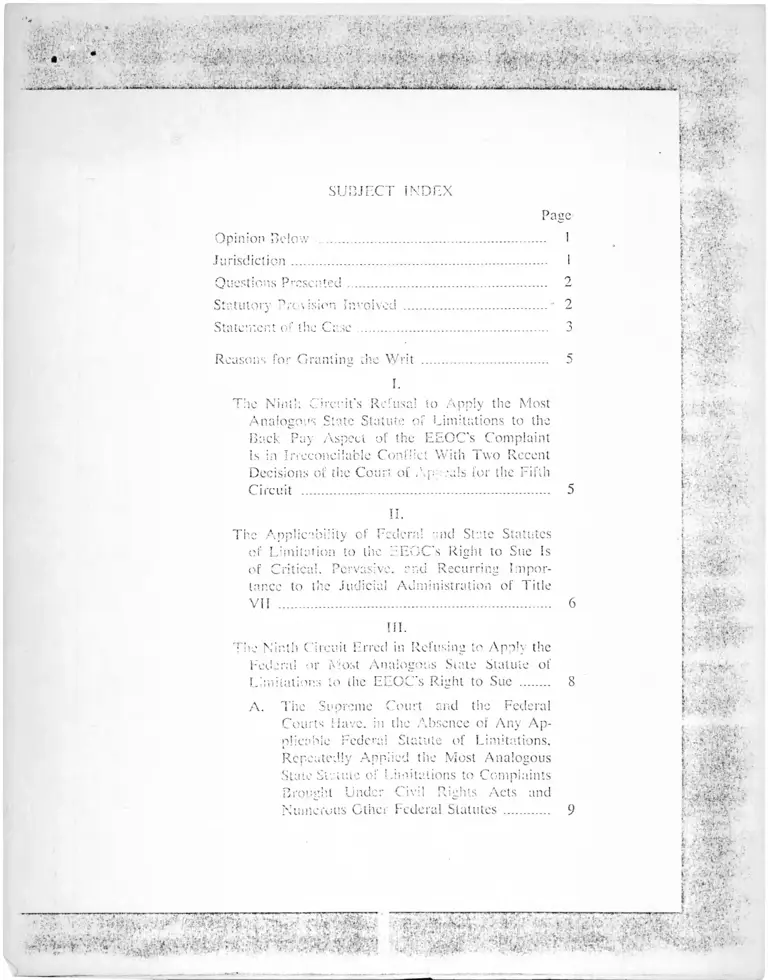

SUBJECT INDEX

Page

Opinion Below......................................... .................... 1

Jurisdiction.................................. ...... ..................-....... I

Question,s Presented..................................................... 2

Statutory Prevision Involved ......................................' 2

Statement of the Case.............................. 3

Reasons for Granting the Writ ................................. 5

1.

The Ninth Circuit’s Refusal to Apply the Most

Analogous State Statute of Limitations to the

Back Pay Aspect of the EEOC’s Complaint

is in Irreconcilable Conflict With Two Recent

Decisions of the Court: of Ap :a!s for the Fifth

Circuit .................................................................. 5

II.

The Applicability of Federal and Stale Statutes

of Limitation to the EEOC’s Right to Sue Is

of Critical. Pervasive, and Recurring Impor

tance to the Judicial Administration of Title

VII ................................. 6

III.

The Ninth Circuit Erred in Refusing to Apply the

Federal or Most Analogous Suite Statute of

Limitations to the EEOC's Right to Sue .......... 8

A. The Supreme Court and the Federal

Courts Have, in the Absence of Any Ap

plicable Fcdcal Statute of Limitations,

Repeatedly Applied the Most Analogous

Stale Statute of Limitations to Complaints

Brought Under Civil Rights Acts and

Numerous Other Federal Statutes ............... 9

Sr

- ’ -------- — « ■ i — m.m ■ ... F —» ’ - T * — ' l " ■ll ’ 1 ■ J ■ ■!.- ■ —

■ a a. i • W. ■■ '• . . . ' ■ .W AW

i ■

- ' r A

: :

m -

O W L ,C ; AE-

La. a - ' :

!• E.XlE,

l .TELA''

i aa i v.■ v .f. ' •-'•vr'.

ti- '¥ ■•’ i ' lVe - •

b ■••••.’,* j - A-' : • - •■AT’-f'T -t , •;

I < a •• :

iIi .. T v

k

l./.iEE

I ’

i l"- ' '

ii . . : :

s ; > • ' E •

' -■!,.va-'.'

Eh ~’

I

‘ • ■ • E .> '

i /MU AWi • ■ »l ;■

! uWSAi-AU «. . W'A

I a'.-a-A'

i- -a i te .

* .

- v . .■• - ' \ •.V. r'-vf' av-Si '

i as , '.'Vj -■

' A u■' » a > •As r\V ' ..f

5 •• _ ■

i - M • .r F, »• y Vv.-.:S5,;*V A V "V-1Q

■VU’I * A'

^ En '.TAj , ' ..

i*H V'-*. V**?

v‘>I 'V.v a.

: • »

• w --!; V: '.>•? r.-:pmf'ya Eup -p,-.. ■

E '"var • e / as,

; ,%r ’ >

■ A . > ' V

• ‘ ::,-vx*Tay: -" ' ?

•S ® tS ■

■ vv4::7.v;. W

■ , f . ■

■

I. . . •••!

1

•:u v • ,1

. ... • ;] : i

1

'A*A... \v

WAFA >

r.\ ;: " •]

f.« \ »*♦ f- \i ■. 1’ .1

i

i

li.

Page

B. The Supreme Court’s Only exception to

the Rule Applying State Statutes cl Limi

tation When No Federal Limitation Exists

Has Been Where the United States Gov

ernment Was Suing to Collect Revenue

for the United States Treasury or to Pre

vent Injury to the United States Govern

ment .......................-................................... 13

C. The Ninth Circuit's Reasons for Expand

ing This Limited “Sovereign Immunity”

Exception to Include Suits Brought by a

Governmental Agenc\ to Recover Back

Pay Claims for Private Individuals Are

Not Persuasive ........................................... 14

1. The Ninth Circuit's Argument That

“Public Policy” Prevents Application

of State Statutes of Limitation to

EEOC Back Pay Claims .................... 14

2. The Ninth Circuit's Argument That

the EEOC Should Be Treated the

Same as the NLRB in This Respect.. 17

Conclusion .................................................................. 19

Appendix. Opinion ......................................App. p. 1

A!

r

■'vv

a y •: r A

A |

wa

■ • - , “3

. )

•AW-:

A'v;4;’Av A

A AAv'v'*rf

-:-5 » r . ' -

It , *.-*■ V ’

•«w*y a

. V /•;: r . • • iv.- •. : | *'• - ■

> * ; . - A '$ ■ :' -.Vf '

■ ■ . ■

V

L

. . . . . . . .

... i - V * : . . '■ u . . .

i

■ - ----- --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- . . . L , ------- -------------------------^ - . . ------------ ----------. . . . . ---------------------------

13

14

jii.

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES CITED

Cases Pa.ee

Adams v. Woods. 2 Cranch 336 ( i<S05) ................ 12

Albemarle Paper Company v. Moody. 422 U.S.

405 (1975) ................ 15

Campbell v. Haverhill. 155 U.S. 610 (1895) .......... 12

Curtncr v. United Stales, 139 U.S. 662 (1893) 13

Davis v. Corona Con! Co.. 265 U.S. 219 (1924)

EEOC v. Christianbera Garment Co., 376 F.Supp.

13

6

EEOC v. Eagle Iron Works. 367 F.Supp. 817 (S.D.

Iowa 1973) ............................................................. 6

EEOC v. Griffin Wheel Co.. 51 1 F.2d 456 ( 5th Cir.

1975). affirmed on rehearing, 521 F.2d 223 (5th

cfir. 1975) 5. 6

Fra nks v. B:Vvvmari J I'cimsrtertati on Co.. U.S.

— ? 14 U.S.LAV. 1 7 TT A A (1 976) 15

.Tollnson v. \\: tiiway Ex Hi•ess Agency. Inc.. 1 O I U.S.

454 ( | 075 ) ...................... 5, 7. 15

Uni ted States v. Beebe, "i27 U.S. .338 (1888) 13

Uni ted States rr

V . a lies M Road Co.. 140

U.S. 599 ( 189!) 13

Un:ted States v. Dcs; Moine:s Nav ipation & R. Co..

i42 U.S. 5 1 0 ( 1 \\;92) 13

Uni icd Suites v. Georgia Power Co.. 474 F.2eI 906

( 5 th Cir. i 973) . .... 5, 6

Uni ted U-j o *" •' /■'. v. M; ISO nrv Contra etors A.ssoci ation

of Memphis. Inc.. 497 F.2d 87! ( 6th Cir. 1974)

.........................-................................................................ 6

United Stales v. Nashville. Chattanooga &. St. Louis

Railway Co.. 118 U.S. 120 (1886) .................... 13

United States v. Summerlin, 310 U.S. 414 (1940)

................. ................................................................. 13

United States v. Thompson. 98 U.S. 486 ( 1879) .... 13

; - , / y .

r .v-.

s oA •l e--**

v ;

' • ..v ■

t

i> -

i

U:

A

i . . • ;

UvlCd,;.

> ■;."

u.w-v.;

I AT" .f.: 'V ' •: •-

V.W‘

fc /.a ;:.

I

ii - . ' v * • ••'•••■ ■ ml V ; . " v ‘JU: ;•* ; -•- •>.; ■*> .. w' Mr .

• -Vjv«.IU ; ■" C > •:r*.. ; Vf.li*. ?. f 4. -■

r{u... A*.,

1 T'"Av

*-~7— ><■ ......... ;• ................... •

‘ J. v .V.* .

' . , • s •. o t t .T y ' '.

• • . ; ' "T

■' ■

. , - ■' . % % ' ■.......• ■:

* . %

. , : ' ■ ■ ■ ' ■ : ■

-.1 ........____ ii_m__ î i— ■ ..<*l‘ . ..»»• ■,■»■!.I.... iV • >•!>i

. x v

•-.V- »' :i

' 'Eg

• ' >

■ w

Vi

•' f

v<

■V-W

' <v

:,V'4

■V .

Statutes

Act of Feb. 26. j 845 (re custom duties): Barney

v. Oelrichs. 138 U.S. 529 (189!) .......................

i at e

10

Civil Rights Act of 1 866: Johnson v. Rail[way Ex-

press / ige:ncv. Inc. , 42! U.S. 4■54 ( 1975 \) .......... 9

Civil Rig!fits Act of 11870: O'Sid ilivan v. Fe.MX, 23j

U. S. 31IS (1914) . 9

Civil Rights Act of 1964.. Title VII, See. 706(b).. 16

Civil Rigfits Act of 1964.. Title VI!, . 706(b)

(2 ) -- 16

Civil RightS Act of 1964. nr;. » . . I iltC VII, See. 706(b)

(4) .. 16

Civil Riahts Act of i 961. Title VII, Sec. 706(c)- 16

Civil Rights Act of 1964,, Title v n . See. 706(f).. 16

Civil Rights Act of 1964.. Title VI i. See . 706(f)

(1) .. 2

Civil Rig! its Act of 11964: United Stat C S V . Georgia

Power Co.. 474 L.2d 906 (5 th Cir. 1973);

EEOC v. Griffin Wheel Co.. 5! 1 F.2d 456 (5th

Cir. 1975 ) ................................................................ 10

Clayton Antitrust Act: Englander Motors Inc. v.

Ford Motor Co.. 293 F.2d 802 (6th Cir. 1961);

Williamson v. Columbia Gas & Electric Corp.,

27 F.Supp. 198 ( I).Del. 1939). affirmed. 110

F.2d 15 (3rd Cir. 1939). cert, denied. 310 U.S.

639 (19-10) ............................................................. 11

Communications Act of i 934: Hufalino \L Micliigan

Beil Telephone Co.. 404 F.2d 1203 (6th Cir.

1968), cert, denied. 394 U.S. 987 (1969) .......... 11

Investment Company Act of 19-10: Esplin v. Hirschi,

402 F.2d 94 (10th Cir. 1968). cert, denied, 394

U.S. 928 (1969) ..................................................... 11

Labor Management Relations Act: Autoworkers v.

Hoosier Cardinal Corp., 383 U.S. 696 (1966) .... 10

Labor '■

of F-

of V-

5 4 5 ■

(197:

Nation;:.

(194'

P;.:: a.

i Cilon l

/ 1 ri r\V i C* V

Raii\v::\

Inc..

Sec mid

A 'i\ i

Shenm

Alio

United

United

United

United

X’nited

United

Hill. Si-

Ling;

66 . :7

. ■ ■ . : V : ! ' 4 • .. . ''

: ■ | ' | ■ ■ '

/

IN THE

October Term. 1976

No.....................

O ccidental

fornia .

L ife I nsurance C ompany of Cali-

Petitioner,

vs.

E qual E m p l o y m e n t O ppo rtu n ity C om m ission ,

Respondent.

Petition for a Writ of Certiorari to tine United States

Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit.

Petitioner prays that a writ of certiorari issue to

review the judgment of the Court of Appeals for the

Ninth Circuit entered on May 11, 1976, in the above-

entitled case.

Opinion Belov/.

The opinion of the Court of Appeals, not yet officially

reported, appears in the Appendix hereto. No opinion

was rendered by the District Court for the Central

District of California.'

Jurisdiction.

The judgment of the Court of Appeals for the Ninth

Circuit was entered on May 11, 1976, and this petition

'The Findings of Fact and Conclusions of Law made and

entered by the District Court appear at 12 FEP 1298 (1976);

the Court of Appeals’ Opinion follows at 12 FEP 1300 (1976).

— — ....... ’: ..................... ------ ~—~

* •• • *

-

■ ■ :

/ ■' " ' \ , ":{V ■ ■ : ■ ' ’ .

1 ' 1 ' ‘ . ; r 1 - ■ ■ "

. • ■ '

4jiÂaw»«*yi..'bnH li-

*;$*.? i.

for certiorari was filed within 90 days of that date.

The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked pursuant to

28 U.S.C. Section 1254( 1).

Questions Presented.

Whether there is no time limitation whatsoever appli

cable to the EEOC's right to sue under Title VII of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964, as amended.

This question involves the following subsidiary ques-

ions:

( 1) Whether the most analogous state statute of

limitations is applicable to the EEOC's right to sue

to collect back pay for private individuals;

(2) Whether the most analogous state statute of

limitations is applicable to the EEOC's right to sue

to obtain injunctive relief; and

(3) Whether the EEOC's right to sue is governed

by any federal statute of limitations.

Statutory Provision Involved.

Section 706(f)(1) of Title VII of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964. as amended. 42 U.S.C. Section 2000e

et seq. (hereinafter “Title VII") provides in pertinent

part:

“ | I | f within one hundred and eighty days from

the filing of |a | charge . . . the Commission

has not filed a civil action under this section

. . . the Commission . . . shall so notify the

person aggrieved and within ninety days after the

giving of such notice a civil action may be brought

against the respondent named in the charge . . .

by the person claiming to be aggrieved. . . ."

: ■?- V. %'■ V-v. • W , .; • - U ; V. !

' •.*::*v i «•*. '• •• . ... •-v-v W riC . 'v A W v ■ -

- - —

(

clu

anc

wit

( he

cl i-

spe

dis

Ed

eh

i a

th;

i . , .

th

rc

Ec.

CO

Ch

c

st;

no

be

tic

:• . . .

■ ' ■/, Y . o .' ; ’ '• > i « ' •

'ate.

. to

•Pli-

thc

of

sue

o f

sue

aeci

fits

'Oe

:nt

>n

Ml

ie

1

it

S ta te m e n t o f ti’jc C ase.

On December ^7 107,0 t

Cl:argC of di~ ™ ™ « o n *

X thc’Taua, E Ca,,f0mi‘n hereinafter “Petitioner”)"

(hereinafter he ° ? H,ro,ni‘J' Commiofon

“ r : : 7

« = - r 5 1 : : - * *

* e date of her discharge by Petitioner. °'

Although the EEOC acknowledged receipt of M

Edclson is charge on December 30 ,« r **>

did not form-,n./ r , , ° ’ l 9 , a !lrc EEOClonnally l,lc the charge until March 9 ' 97 ,

This was the only charge which Ms Ed-I,on

f"Cd •*“'"« Petitioner, and the EEOC aCm ^

that this is acknowledges

herein is based. ' ' * * * “P° " emire <»™PWnI

Howeyer. it was not until February 27 1974

Edclson had S ^ T S S c T ?

complaint seeking back nav for ‘' E° C f CU " s

vidua,s and initnietive re, ef A 7 ° “ ^ * *

Court dismissed the E E O cC c DiS' riC‘

S io u ndstha , ( | ) Tide VM ? UP° " " *

- . . e o f i i ' i t i r i ^ : " , ; 80^ ^

<*> ‘ '-native,y. asst: d ^ T h l e Vn '° 7

m> federal statute of limitations, the EEOCs P

- r hy the most anaiogous state

I 7 v > ■

i ^ m

I >-■ ■ ■ ■ .

h v ^ i - y

< ( -c i -: ,,

i s f :f " , 7

i, . .

i

I

: .'■•'v.D

If?-T

1 • . a .

i .-.'t-w .,

i '.v'M

K J' '

.v>kv:v

J ,

r -7 ■t V i;

.«e

hi:

iV -V.,,-. c- .X'DV: 7 7

' (7 -,r> h'Vsi C ‘■ T ■■■--

Vi1*'?; rv-j. ■*

«•*»;,/ •

4 ' c - v .

■ vfs. ; ... C -• ... . .. ' '

,

'V.M'Vr. eh

>V?y.

‘fv7. v,f. •,

\

f

-4—

On May II, 1976, the Court of Appeals for the

Ninth Circuit reversed on both grounds, holding that

there was no lime limitation whatsoever on the reEOC s

right to sue. First, the Court found that the 180-

day languaae of Title VII docs not constitute a federal

statute of limitations on the EEOC's right to sue,

so that “there is simply no governing federal limitations

period.” (A. p. 5). Second, the Court refused to apply

the most analogous state statute of limitations to the

EEOC's right to sue.

It is to these two holdings that this Petition for

Certiorari is directed, particularly that aspect of' the

holding in which the Court expressly ruled contrary to

two recent decisions of the Court of Appeals for the

Fifth Circuit which held that the EEOCs right to

recover back pay for private individuals is governed

k" die most analogous state statute of limitations.

r e x :

The Nir.

an interim;

private inch

decisions o'

Supreme C

analogous

in absence

which rub

Supreme 6

v. Raih.vov

The Ninth

O^o *JS

Aspcc

c is 4*1)

Cour

In Unit

906, 922-'

that becat.

the most

applicable

discrimina

eminent m

in EEOC

(5th Cir.

223 (5th

the Fifth

statute of

aspect of

by the E'

i|

i,i

i , ,.....................................

. . . .

: | - i f -

Kit

C's

ie.

"S

■>r

:c

S.

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT.

The Ninth Circuit's holding that the EEOC has

an interminable right to sue to collect back pay for

private individuals is in direct conflict with two recent

decisions of the Fifth Circuit and contrary to numerous

Supreme Court decisions which hold that the most

analogous state statute of limitations should be applied

in absence of an applicable federal statute of limitations,

wnich rule has most recently been applied by the

Supreme Court in a Civil Rights Act case in Johnson

v. Railway Express Agency, Inc., 421 U.S. 454 ( 1975).

e

n

d

I.

The Ninth Circuit’s Refusal to Apply the Most Anal

ogous State Statute of Limitations to the Back Pay

Aspect of the EEOC’s Complaint Is in Irrecon-

ci,ab,c Conflict With Two Recent Decisions of the

Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit.

In United States v. Georgia Rower Co., 474 F.2d

906, 922-924 (5th Cir. 1973), the Fifth Circuit held

that because there was no federal statute of limitations,

the most analogous state statute of limitations was

applicable to the back pay aspect of an employment

discrimination suit brought by the United States Gov

ernment under the Civil Rights Act of 1964. Thereafter,

m EEOC v. Griffin Wheel Co.. 5! 1 F.2d 456, 458

(5th Cir. 1975). affirmed on rehearing, 521 F ?d

223 (5th Cir. 1975). another three-judge panel of

the Fifth Circuit held that the most analogous state

statute of limitations was applicable to the back pay

aspect of an employment discrimination suit brought

by the EEOC under the Civil Rights Act of 1964

I

■ 1 - ■ ? v , A'TT

, j M ~

' 4 “ " . s.b,,. a. 7 •* J+ * ■ . •'■if* *> f- ' ... . . ■ .-V : ■ . •• -.'v ?£& EAOi . r , . • • '• .■ .* . ' ... *

, '• - -* . * * ? ; > £ • $ ii

»ii— *..m« ■— i tim~*

'

■yX

y ^ i «

I

i

•«

i

i

iiii

!

ii

]

i

1

!

f

i

t

;iA

Ji

— 6—

The Sixth Circuit in dicta lias exp. ..red its agreement

with Georgia Power,~ and at least two district court

decisions have reached the same result as Griffin

Wheel:'

Nevertheless, the Ninth Circuit refused to apply the

most analogous state statute of limitations to the back

pay aspect of the EEOC complaint herein, finding

instead that the EEOC's right to sue to recover

back pay for private individuals was interminable.

Expressly noting the contrary decisions of the Fifth

Circuit, the Court stated. “We decline to follow its

lead" (A. p. 11). The conflict between the Fifth

and Ninth Circuits concerning the applicability of the

most analogous state statute of limitations to the back

pay aspect of an EEOC complaint is thus clear,

unequivocal, and irreconcilable, and certiorari should

be granted to resolve that issue.

II.

The Applicability of Federal and State Statutes of

Limitation to the EEOC’s Right to Sue Is of

Critical, Pervasive, and Recurring Importance to

the Judicial Administration of Title VII.

Over the years the EEOC will be the party-plaintiff

in thousands of cases across the United States, many

of which will involve EEOC efforts to recover back pay

-In United Slates v. Masonry Contractors Association of

Memphis, Inc., 497 F.2d 871. 877 (6th Cir. 1974), the Sixth

Circuit stated:

“The appropriate statute of limitations for a Section 2000e-

6 action |by the United States Government] is the limi

tation period prescribed by the state where the court sits

for an action which seeks similar relief brought in a court

in that state."

'■'EPOC v. Eagle Iron Works, 367 F.Supp. 817 (S.D. Iowa

1973), and EEOC r. Cltristianherg Garment Co., 376 F.Supp

1067, 1071-1073 (W.D. Va. 1974).

for private

EEOC coin

years after

complaints t

Thus, wit

EEOC com-

one which

enerev. ant:

litigants i;v

such issues :

until this C

the question

cal to a m

court resow

EEOC com.

Furtherm

statute of 1:

discriminat:

the Civil E

"v. Railway /

that the m<

is applicable

cant, rccurri

rnent disci

also governe

its right to :

by this Petit:

Finally, a

issue is crib

Title VII.

takes severa:

federal cow

to sue is ini

belief—and ;

■ . . . . ? '

■V v A i"' v- ■ ' ■ . ■ ■W: . ' ' ■ ■ ?. 'V . ,■o' O, ■ • .*’/ ; V. • “ • . / • > K-J' S ?..••• j-. • . 1 v: . . . . ■ - ' •' ■ "

■ ,-.v . • .. \ ;v -{• y.-,. . - t. ;•» »■ : • • > ,. ■ ' .■ :4 ri, * •■'.•*<’ ?.■ ■: • A, . .

; C T A . V T C t t t a -- '.'v : T Af'-h'o.R

•»' ' V *' •* * ' * ’ t " . -

1 - . . . . i 'i. 1 — . . ____ __ a . ■■■■■'

: merit

court

• riff in

y the

back

auing

•cover

ruble.

Fifth

vv its

Fifth

4 the

back

•!r*o **

h.ould

:s of

Is of

■ce to

.intiff

many

k pay

on of

Sixth

2000c-

j limi-

::t sits

.1 court

. Iowa

■'hupp.

for private individuals. Furthermore, many of these

EEOC complaints will undoubtedly be filed several

years after the filing of the charge upon which these

complaints are based.

Thus, whether any statute of limitations applies to

EEOC complaints will be a constantly recurring issue,

one which will continue to consume substantial time,

energy, and resources of the federal courts and the

litigants involved. Furthermore, litigation concerning

such issues is certain to increase rather than to subside

until this Court accepts review and definitively answers

the question. Consequently, a prompt resolution is criti

cal to a more effective utilization of limited federal

court resources and a more expeditious resolution of

EEOC complaints.

Furthermore, this Court has already resolved the

statute of limitations issue with regard to employment

discrimination suits brought by private individuals under

the Civil Rights Act of 1866. holding in Johnson

v. Railway Express Agency. Inc.. 421 U.S. 454 (1975),

that the most analogous state statute of limitations

is applicable to such suits. Accordingly, the most signifi

cant, recurring timeliness issue which remains in employ

ment discrimination cases is whether the EEOC is

also governed by some statute of limitations or whether

its right to sue is interminable—the very issue presented

by this Petition for Certiorari.

Finally, an early Supreme Court resolution of this

issue is critical to fulfillment of the purposes behind

Title VII. At the present time, the EEOC frequently

takes several years simply to file its complaint in the

federal court, apparently presupposing that its right

to sue is interminable. If die EEOC is wrong in this

belief— and there are compelling reasons set forth below

■

)

Ii

4

j

.1>

j

— 8—

to believe that it is— its present practice of interminable

delays clearly subverts the purpose of Title VII by

preventing expeditious resolution of employment dis

crimination claims. If, however, such interminable de

lays are indeed what Congress intended, that should

be established by Supreme Court decision, not ad

ministrative fiat, for the adverse effect of such delays

is obvious.

III.

The Ninth Circuit Erred in Refusing to Apply the Fed

eral or Most Analogous State Statute of Limitations

to the EEOC's Right to Sue.

Four choices exist concerning the timeliness of EEOC

complaints: ( 1) the EEOC’s right to sue is governed

by a federal statute of limitations, (2) the EEOC's

right to sue is governed by the most analogous state

statute of limitations, (3) the EEOC’s right to sue

to collect back pay for private individuals is governed

by the most analogous state statute of limitations, or

(4) the EEOC's right to sue is interminable. The

Ninth Circuit concluded that the most extreme, fourth

option— the interminable right to sue—was the one

Congress intended. That conclusion is plainly in error.

With regard to the first option—the 180-day pro

vision of Title VII as a federal statute of limitations—

Petitioner presented 18 pages of argument and authority

to the Ninth Circuit showing why that was Congress'

intent, and Petitioner remains convinced that thm "in

clusion has substantial merit. Petitioner also presented

argument to the Ninth Circuit in support of the second

option—that the EEOC's right to sue. not just its

right to collect back pay for private individuals, is

governed by the most analogous state statute of limita

tions. Bee:

circuits on

second op:

ments on :

the com pc ■

refusing—

most anal-

pay aspect

the EEOC

pay. Howe

concerning

to back p

of private

be advise!

on the fc

genera! st:

ing itself

options.

A. The Si;

Absence

Repent',

Li’iiha:

anti Ni:

Many fc

tions, and ■

that suits

the most an

Civ:

(

Civ

■ ‘c V

" C T

- e - : ■

. R. . • .' - -

. V Jr

tm ': . • ■ ' . ■ ■ ■ '■ ' fSik&Zz'V •H

I f - C f A V . 9 ■ a, TvV V , .>{>• :*• 7 c • ■ 5 * v I- v: •*

. ■ fy.v\

__

i ; - '

k ;1 . .

e de-

louid

ad-

clays

j< 0 ( 3 .

cons

:oc

:rncd

OC's

state

sue

■Tied

• . or

The

urth

one

rror.

pro-

ority

t o s s '

con

oted

ond

its

is

1 ila-

tions. Because there is as yet no conflict among the

circuits on the issues raised under either the first or

second options. Petitioner will not summarize its argu

ment: oit these points at this time, focusing instead on

the compelling reasons why the Ninth Circuit erred in

refusing—contrary to the Fifth Circuit—to apply the

most analogous state statute of limitations to the back

pay aspect o? the EEOC's complaint and holding that

the EEOC has an interminable right to sue for back

pay. However, if this Court grants the writ of certiorari

concerning the applicability of state statutes of limitation

to back pay claims asserted by the EEOC on behalf

of private individuals. Petitioner submits that it would

be advisable for this Court also to grant certiorari

on the federal statute of limitations issue and the

general state statute of limitations issue, thereby afford

ing itself full consideration of all of the available

options.

A. The Supreme Court and the Federal Courts Have, in the

Absence of Any Applicable Federal Statute of Limitations,

Repeatedly Applied the Most Analogous State Statute of

Limitations to Complaints Brought Under Civil Right:; Acts

and Numerous Other Federal Statutes.

Many federal statutes contain no statute of limita

tions, and thus the Supreme Court has repeatedly held

that suits filed under such statutes are governed bv

the most analogous state statute of limitations:

Civil Rights of 1866: Johnson v. Railway e x

press Agency. Inc., 421 U.S. 454. 462

(1975):

Civil Rights Act of 1870: O'Sullivan v. Felix,

233 U.S. 318. 322-324 (1914);

• ' i p ; " , ~ p ?

• - ■ mv -C <> ".V •:; •?».' V * ‘ • . • •• ■“:! *• * T » *• J ' * C •

. '.Tp-V., :

. I'JP' ■ ! X\ ■ .

H- ‘ ’C U . ; ' . .

: r .

» «■’’••• ’,

* . T\ .l - ' ...

| If ' p . | ■ : ;

vV ■ \ ' ■ tfi'-M., ' - : ’ O ' •, : v t T : \ - * n . .• , V ;.. V,... IS •

■ . / • , ‘ ■ ■ ■ ■ , ■ $ • 1 .. , . . ' : ■ ■ ■ . . ■ ■ • •

___ ...

.. i

— JO—

Labor Mm-,,,.,

701-705 0 9 6 6 ) "" 383 ^.S. 696.

O ". i'. Allciara ">03 I I S 1 Q n ° 08<‘ 8,'>n!u!iy

National n„„kJ ^ ^ 397 ('906);-

U S- 961. 463 ( 1947 w £ 33!

-’ >2 U.S. 96. 97-98 0 9 4

«//o-<-.v. 299 u.s. 2/7 V'

Ac,: Campbell „ h

610, 6J3-6I8 0 89% . ' W / "»- '55 U.S.

/<ict ° f Feb. 26 JRiS /

Sim ilarly , t/ic fpdnr 1

° f "n,l!al'on 10 „ lhe; S '’;'VC W * « * e statulcs

TO fcd- a l statute of which e„nlai„cd

O r// ///o/z/.v ^ f7 of J9

G^>rnja p / _ O / /W 5/67/^ v.

<*■ >973):

5 M F,2<. 456. 458.459 ( 5 % % Co.,

Railway Labor A rt- / ' )a

1974): 79°- 799 (2nd Cir.

£ " ,’" r Mmagement Repo -,!,

A c , „/, 9SV . ^ a D * c h » , ,e

* f ”o f M a c h i n e

445 f ' 2d 545. 548-549 (5Z c ‘ * ”* " *

______. ‘h " U '<- 904 U.S. 1024 0 97, % ' ,9 7 l>-

the aiithnI'/a!.H/ / ,“ '1-' 01 ""illations for ■ ,

Sections 15(b), J 6. e'U,Clcd b-v On stress in '1 9 ™ f j ,Wulcri o u.s.c.

MATA-' ■ ' ■V/., . •: . ' • . .4.4 . - ■ v

grid ■'.V, | ■ ). 'y;'.. ; •; •• ; -V';.;; • . V1 V’ f ■■ •• . . i.* ' ' : *’ • •.■>/> .iry. y- • v * •

-------- --------- -

orkcrs

. 696.

■undry

906):'

331

. Ray,

Estate

5 U.S.

barney

latutes

'.laincd

:tes v.

13 (5th

■! Co.,

} *

■■■hi Air-

mi Cir.

■̂■closure

Intern.

i ot hers,

1971),

'it under

15 U.S.C.

— 11—

Clacton Antitrust Act: Englander Motors Inc.

v. Ford Motor Co., 293 F.2d 802. 804 (6th

Cir. 1961); Williamson v. Columbia Gas &

Electric Carp., 27 F.Supp. 198 (D.Dcl.

1939), affirmed, 110 F.2d 15 (3rd Cir.

1939). cert, denied, 310 U.S. 639 (1940),

Securities Exchange Act of 1934: Richardson

v. Mac Arthur, 451 F.2d 35. 39 (10th Cir.

1971); Douglas v. Glen E. Hinton Invest

ments, In cS 440 F.2d 912, 914 (9th Cir.

1971); Klein v. Bower, 421 F.2d 338, 343

(2nd Cir. 1970); Morgan v. Koch. 419 F.2d

993. 996-997 (7th Cir. 1969).

Communications Act of 1934: Bufalino v. Mich

igan Bell Telephone Co.. 404 F.2d 1203.

1208 (6th Cir. 1968). cert, denied, 394 U.S.

987 (1969);

Investment Company Act of 1940: Esplin v.

Hirschi, 402 F.2d 94. 101 (10th. Cir. 196S),

cert, denied, 394 U.S. 92S ( 1969).

Thus, tire rule that state statutes of limitation are

applied where no federal statute of limitations exists

is firmly embedded in our jurisprudence, and with

(T0od reason, the most basic of which stems from an

elemental sense of due process, best summarized oy

Chief Justice John Marshall’s statement in 1805 that

an absence of some statute of limitations

“would be utterly repugnant to the genius of our

laws. In a country within which not even treason

can be prosecuted alter the lapse ot tluec vcais.

it can scarcclv be supposed that an individual

•

t , ■

j- ':

iy. •

i

t

; c

f '

|

m .' 4 4 • . | £ ■ - .

Zjkiifir. *„ * ■■ . >4 *

4 • *

would remain Forever liable to a pecuniary Forfei

ture."

Adams v. Woods, 2 Craneh 336. 342 (1805).

Second, statutes of limitation are designed to pro

tect both the courts and defendants from stale claims

which depend upon evidence and witnesses the availabil

ity and reliability of which have been impaired by

the passage of time. E.g., Campbell v. Haverhill, 155

U.S. 610. 617 (1895).

Third, given the well-established nature of the rule

that state statutes of limitation will be applied in

the absence of federal statutes of limitation, it is

far more reasonable to assume that Congress intended

that rule whenever a Federal statute of limitations was

omitted than it is to presume that Congress intended

the right to sue to be interminable. Hill. State Procedural

Law in Federal Nor,-Diversity Litigation, 69 Harv.

L. Rev. 66. 78-81. 91-92 (1955), and cases cited

therein.

Thus, where the refusal to apply the most analogous

state statute of limitations means that the right to

sue is interminable, only the most compelling reasons

could justify that result, which Chief Justice John Mar

shall found “utterly repugnant to tire genius of our

laws." Adams v. Woods, 2 Crunch at 342. Were it

otherwise, quite obviously defendants would be unfairly

and prejudicially subjected to potentially massive and

totally unknown financial liabilities.

4

15.

appl

tiic

the

its •

the

to i

•j talc

Stak

Unit

(U;,:

from

nooy

(Uni

the i

U.S.

whici

roads

140 1

land

State:

vidua.

ana!'.'.

Unite

v. I 'm

Des A

m . t-y 4t. • ~ ~ y .. C. l." .? • ""‘.'J'.*'"** *" "7 '» ■< ■■■ w t ■■■■! i<-n». ■—r*

' ■ . . . . . . ,

• _ ■ • ■

' ' ■

■

’ ' ■ ■ ■ ' - ' >'

, ' . . - " . ■ ■ . ' ;

, -■ ■■ ■ — -------------------- t ..*.— . — . . . . . . .— m------------

■f >;

i 01-

'i'O-

Tns

oil-

by

; 55

ule

in

is

Jed

was

ided

'■tnil

arv.

1 ted

•ous

to

sons

lar-

our

c it

iirly

and

— 13—

J5. The Supreme Court's Only Exception to the Rule Applying

S(a!c Statutes oi Limitation When No ! edcral Limitation

Exists Mas Been Where the United States Government Was

Sninjr (o Collect Revenue for the United States 1 reasurv or

to Prevent Injury to the United States Government.

The few Supreme Court decisions which refuse to

apply the state statute of limitations to a suit by

the United States Government invariably do so because

the United States is suing as a sovereign to protect

its rights as a sovereign, /.<?., to collect money for

the United States Treasury or to prevent an injury

to the United States Government itself. E.g.. United

States v. Summerlin, 310 U.S. 414 (1940) (United

Slates attempting to eniorce its claim against an estate),

United States v. Thompson, 9S U.S. 486 (1879)

(United States seeking recovery of funds embezzled

from its Treasury); United States v. Nashville, Chatta

nooga &. St. Louis Raihvay Co., 1 18 U.S. 120 ( 1886)

(United States suing to collect on bonds owned by

the United States); Davis v. Corona Coal Co., 265

U.S. 219 ( 1924) (United States suing to enforce claims

which arose during United States operation of rail

roads): United States v. Dalles Military Road Co..

140 U.S. 599 (1891) (United States suing to recover

land it had granted). However, whenever the United

States Government has sued on behalf ot private indi

viduals, the Supreme Court has held that the most

analogous state statute of limitations is applicable. E.g.,

United Stales v. Reehc, 127 U.S. 338 (1888); Curtner

v. United States. 149 U.S. 662 ( 1893): United Suites v.

Des Moines Navigation ct R. Co., 142 U.S. 510 ( 1892).

U

. ' \0$x\ .wA-wm, $£<$?. .;■;• •;'/.. g • •:•■■ . \ f : m ■

■ p . ■ . f • . - , • .: . ■'• '■ ■ ... - ■ # ■ ■■• -

■ ■ » f t • ■ ' • ■ m •■ , . * : i h . . ■ • ■..... .. V •- •

- J m . ■iL>,il..J...«̂ J.î ..M',j... ~r ,11

— 14—

C. The Ninth Circuit's Reasons for Lxpuuriing This Limited

“Sovereign Immunity” Exception to Include Suits Hrought

by a Governmental Agenev to Recover Rack Pay Claims for

Private Individual.s Are Not Persuasive.

No Supreme Court decision to date has ever found

tiie United States Government or one of its agencies

immune from the state statute of limitations where

the government or agency was suing to collect money

on behalf of private individuals. That, of course, is

what the EEOC would have this Court hold for the

first time. Yet neither of the reasons offered by the

Ninth Circuit for such a substantial departure from

Supreme Court precedent has merit.

I. The Ninth Circuit's Argument That "Public Pol

icy" Prevents Application of State Statutes of Lim

itation to EEOC Back Pay Claims.

With no evident analysis of prior Supreme Court

decisions or federal court decisions concerning the appli

cability of state statutes of limitation to government

suits brought under other federal statutes, the Ninth

Circuit concluded that because an award of back pay

to private individuals in an employment discrimination

case serves a “public interest." state statutes of limitation

could not be applied to such suits. There are at least

two compelling answers to that argument.

First, the decisions discussed above page 13 simply

do not support the conclusion that a state statute

of limitations is inapplicable whenever a "public in

terest" may be served by the lawsuit. Rather, the only

exception to the state statute of limitations rule has

heretofore been limited by the Supreme Court to suits

where the United States Government is suing as the

sovereign, seeking to protect its rights as the sovereign.

The e.v

lion of

be com

law sir

immuni

collect i

Thu-,

the coi

inappli

by the

ments :

/(lb emu

public ■

not sc:

pay rec

to the ■

in the

more. ,

to be .

Act of

Exprey.

applied

d ism. is-,

that til*

action v

state !;;

entitled

suit is b

The >

policy"

of limit

policy"

•'.... t \

r,422 l

— 15

it CO

:;iit

for

and

lies

ney

is

die

'(>!-

:in-

nirt

.ill-

C 11L

'nth

pay

lion

.ion

cast

-ply

lute

■ in-

only

has

suits

the

den.

The except’on is. in other words, simply a manifesta

tion of the doctrine of sovereign immunity. It would

he completely inconsistent with the trends ol modern

law suddenly to expand that doctrine of sovereign

immunity to encompass government agency suits to

collect money for private individuals.

Thus, prior Supreme Court decisions do not support

the conclusion that a state statute of limitations is

inapplicable whenever a “public interest" may be served

by the lawsuit. Accordingly, this Court’s recent com

ments in Franks v. Bowman i ranspoitation Co., and

Albemarle Paper Company v. Moody" concerning the

public purpose served by awards in Title VII cases do

not serve to bring such lawsuits, or at least oack

pay recovery thereunder, within any existing exception

to the rule that state statutes of limitation are applied

in the absence of federal statutes of limitation. Further

more. as much could be said about a public purpose

to be served by awards in suits under the Civil Rights

Act of 1866. yet this Court in Johnson v. Railway

Express Agency, Inc., 421 U.S. 454, 462 (1975),

applied a state statute of limitations to affirm the

dismissal of such a cause of action, making clear

that there is nothing “peculiar in a federal civil rights

action which would justiiy special reluctance in applying

state law.” Therefore, the EEOC's right to sue is not

entitled to anv special exception simply because its

suit is based on Title VII.

The second reason why that Ninth Circuit's “public

polk " -.it-male for re IT Ting to apply the dale statute

of limitations is erroneous is because, in fact, “public

poliev'' and Congressional intent clearly rec/uire some

U.S..... . 44 U.S.LAV. 4356 \ 1976).

i;422 U.S. 405 (1975).

'

ij

I

i

I V C ' C" . | N §§ ■

■ ■' ■ ■ ' EC

— 1 6 —

lime limitation on the EEOC's right to sue. Title

Vi! is replete with short specific time deadlines designed

to guarantee prompt handling of all employment dis

crimination charges.7 This elaborate statutory proce

dure imposes strict time limitations on two parties

to the process—the aggrieved party and the federal

court. T’he issue here presented is whether Congress

also intended the EEOC to operate within certain

time limitations as well. In a statutory enforcement

scheme that depends on all of the parties for success,

it is inconceivable that Congress would have intended

that only two of the parties—the aggrieved party and

the federal court—be required to proceed expeditiously,

particularly where the interminable delay of the third

party—the EEOC— can effectively nullify any expedi

tious action by the other two parties.

Furthermore, with no time limitation, the EEOC

has absolutely no incentive to expedite its handling

of charges. The EEOC can— and obviously does—take

as long as it wants to. doing a great disservice not

only to aggrieved parties but to respondents as well.

While the EEOC has an obvious administrative desire

for an interminable period in which to file suit,

what Congressional purpose behind Title Vll is served

by permitting— indeed, encouraging— such delay? Far

from increasing compliance with the Act, such delays

simply lessen the effectiveness of the EEOC and lessen

the likelihood that truly aggrieved parties will turn

to the EEOC for relief. Clearly, such delays impose

■See Sections 706(b) , (e) and (f) of Title VII, as evidence

of the Congressional insistence on prompt action and particularly

the several onerous time demands and limitations imposed on

the federal district courts, such as requiring the court to assign

such eases for hearing “at the earliest practicable date,” to cause

such cases “ to be in every way expedited.," and “ immediately to

designate a judse . . . to hear and determine the case." Sections

7 0 6 (b ) (2 ) and (4).

upon r,

un reuse

sive fin;

In si

grcssic;

process

person-

of fair

thus

result v

of limit

2. T :

Sh

A /

The

refusin;

the EE

enforce

enforce

the sa:

Yet cw

that s'

NLRB

Court"-

sNeitk

its co:ic!

to n l r :

decision

the state

delay in

decision,

after th.

was dire

issued. O

at the i:

of event

in both

state sla

NLRU c

. -■ t-e . .

Y-v'W ' $

net!

dis-

vjc-

iies

oral

:rcss

:.ain

tent

O S S .

• rd

OC

ling

tak e

not

veil,

os ire

suit,

rvcci

days

ssen

turn

pose

• donee

"iKir'iy

. tl on

: ssign

cause

,e!\ to

olions

— 1 7 —

upon respondents an unwarranted burden and a wholly

unreasonable exposure to unknown and potentially mas

sive financial liabilities.

In short, every aspect of Title VI1 envinccs a Con

gressional conviction and insistence that the enforcement

process move swiftly, for the benefit of the aggrieved

persons and respondents and for the prompt realization

of fair employment practices for all. “Public policy

thus requires prompt EEOC handling ol charges, a

result which will be assured only by applying a statute

of limitations to such claims.

2. The Ninth Circuit's Argument That the Ec.OC

Should Be Treated the Same as the NLRB m

This Respect.

The second reason the Ninth Circuit oifered for

refusing to apply the state

the EEOCs complaint was

enforcement procedure;; are

enforcement procedure:s an<

the same with respect to state statutes of limitation.

y ct cven assuming that this Court were to conclude

that state statutes of limitation are inapplicable to

NLRB complaints—an issue not yet decided by this

Court''-__that conclusion cannot properly be extended

svephe- 0f' the eases cited by the Ninth Circuit to support

its conclusion that state statutes of limitation arc mappl.cable

to NL RB comnlaints arc Supreme Court decisions, and nu .hu

decision made that specific holding, tor in iKMtncr ctisc was

the sf'tutc of limitations argument directed at the N LRBs

lehv in filin'.’ its complaint. For ail that appears m cither

decision the NLRB's complaint issued within a icasommle turn

! lcr the chance was filed; rather, in each ease the attach

' i;r i V the NLRB's delay after its complaint had

issued. Of course, statutes of limitation have always been directed

.u t|uf timeliness of the filing of the complaint, not tnc pace

f, Cents' thereafter. Therefore, while there is certainly dicta

in tV)ih lower court decisions to support the conclusion that

state' statutes of limitation are inapplicable to the tiling of

NLRB complaints, neither case squarely so held.

i

k,

r\

r.

i '.

I

x

\

ErL .

L(

j

.

■ ■ .-V • 1 ’■

■ ■ •1 • h i ■■ ■ ■" '

■ ■ ' . ■ ■ - ■ • - ■ : . ■. W.-.-

____ —J m ..... ... -... — -■ . 1 ....

— 18—

to the EEOC, for the enforcement procedures of the

two agencies are radically different.

The key distinction is that the EEOC must go to

court and file its complaint in the federal district

court before any legally cognizable adjudication occurs.

By contrast, the NLRB never has to file a complaint

in the federal district court as part of its normal

enforcement procedure: rather, the NLRB issues its

own complaint and the NLRB has been given full

authority to function in lieu of. and in effect as.

the federal district court. Thus, the only time the

NLRB goes to federal court is to the appellate level.'1

Obviously, state statutes of limitation have never been

thought to apply either to internal agency procedures

or to appeals; they are applicable to the filing of

a complaint in a court, an act which the EEOC must

do and the NLRB need never do. There is, in short,

simply no “complaint" that a statute of limitations

could apply to insofar as the NLRB is concerned.

This critical distinction between the NLRB enforce

ment procedure and the EEOC enforcement procedure

is all the more significant because it is the result

of a deliberate Congressional decision to withhold from

the EEOC the authority which the NLRB has always

enjoyed, in both 1964 and in 1972. extensive efforts

were made in Congress to give the EEOC full NLRB-

type enforcement authority—and both efforts were re

jected by Congress in favor of the present requirement

that the EEOC initiate its enforcement efforts by the

filing of a complaint in the federal district court. Thus,

to hold the enforcement procedures of the two agencies

9Thc only exceptions are suits by the NLRB in federal

district courts to obtain preliminary injunctive relief pending

completion of the adjudicative process before the NLRB itself.

29 U.S.C. Sections 160( j ) and (I).

to '

to

it ll:

ina:

givi

bae

the

put-

res

the

this

Fift

resr

in e

full;

be r

P a t

O

tv ̂ ■ . ./.*■ ' • ■

5 '■ 1 , ; W . : A C V , f

■:•’■ - ' ■ L f ' f ■ •

‘ ■ ■ " T f . c - 7 , . ■ -

. J l „•■ • •* .

">-V-

-*•’*-* k—U - . _____ _ —• ■'■ *'' ~ — -*rft1 n

7 V;'V;'

[. ,.

i .

•if the

go to

•:'.strict

'ccurs.

plaint

ormal

:s its

' full

:t as.

- the

:evei.:’

been

durcs

g c

must

f

hort,

dons

orce-

. 'dure

esult

from

'.vays

forts

RB-

e rc-

ment

the

hus.

ncies

— 1 9 —

*° be analogous is to ignore live Congressional refusal

to give the EEOC the same enforcement authority

it has given the NLRB.

1 ne Ninth Circuits iNLRB analogy is thus totally

inapposite.

Conclusion.

In tiie final analysis, the decision of the Ninth Circuit

giving the EEOC an interminable right to sue to collect

back pay for private individuals will plainly frustrate

the Congressional intent that discrimination cases be

pursued expeditiously and will just as plainly prejudice

respondents in the defense of such suits. In view of

tiic fact that the holding of the Ninth Circuit on

tins issue is in direct conflict with decisions of the

Lifth Circuit and in view of the fact that a definitive

resolution of this issue is of enormous importance

in employment discrimination cases, Petitioner respect

fully submits that this Petition for Certiorari should

be granted.

DATED: July 22. 1976.

Respectfully submitted.

L eonard S. J anofsky .

D ennis H. V aughn .

Howard C. Hay.

Attorneys for Petitioner.

* ••vU Hasting.-) <n ja nofsk y ,

Of Counsel.

it

V

Kline

- J - : - v *'

'“ A V ......

-

: . ■ . ■ ’ • ; . ■ • !" .

________ ________________ — — ------------t: ■ -w TO; ' "k

a p p e n d ix .

Opinion.

in the United States Court of Appeals, tor the Ninth

C*Eciua! Employment Opportunity Commission, Plain-

J Z l l V. Occidental Lil. Insurance Contpany

of California. Defendant-Appellee. No. 75-1705.

Appeal from the United States Dtstrtct Cot,., (or

the Central District of California^

Before: WRIGHT, KILKENNY and TRASK. Ctrc.

Indies. WRIGHT. Circuit Judge:

reverse and re.

mand.

PROCEEDINGS BELOW

n , Pccember 27. 1970. Tamar Edelson filed with

- FOC a charge against Occidental Life Insurance

tnc EEC a - lleffi that she had been

2 = £ t = = = - = ' « T rtool place" was October 1970. the date o, her

discharge by Occidental. .

The EEOC referred the charge to the J “

- Practices Commission, in accordanceFair Employment Practices A i 4? U S C §

• .up nrovisions of Section 706(c) |42 s

9000e-Sfe)|. When that agency took no action, t c

charge was formally filed with the EEOC on March

9-1971. ,

The EEOC undertook an ™ ™

ruary 25,

unaciiouN Gi — -

1972. its District Director issued Findings

’ i i . .. i ,T' . :'-'’A. . .

■ .? , ' ■ .

. •

'■ ■■ ;- - V. ,' A ....■:>:: ..:.ac

I- ; 7 .- ■' - ■ "1 ■■■■■• ■■ ■

ih 1.-

f ’

t wT V- ‘-

. >>*.

<'r ‘: ■ j • •

1 A-i - •

V -U V

y -

r

• V'..* E

' c l .

•O ;7,vo

k:i

I .

,• *T '< ', ' V

■ .‘if

" ' >:• W/.V t

. . • S p f e « * @ s > 3 # '■ ■ ■ ■■ ■ : .

I I I I ■ ' ' ■

• . ' OVT.IV , WW WOW CyvY.y- W/4 m-, . 7 A T A - W E, i ■■; - . ■ .. r ' . • . ' • . ■

... V'

’V?

..-iiuU.H d n&M

■ ' »■ . ■ ■. - '* ,V: • • .

- --Ldmldom .■IliMlU

’ 'A ■ A

; v |1

; V)

. t * n

j

i

• ■ i

1

Y w j

'•'■■ ■. -j. . ■■» '• • .w v

•'■1; •: .. .- * .

I

■

dM . ■■;

i

i l ' .«

. . ■ ■ if

,

of Fact that Occidental had discriminated against Ms.

Edclson and also K,d discriminated against many other

employees through a variety of practices and policies.

Occidental filed exceptions to the findings on March

23. 1972. The EEOC issued its “Reasonable Cause”

Determination on February 8. 1973 and during the

following year, held a conciliation meeting with Occi

dental.

When that effort proved unsuccessful, the EEOC

filed tills action in district court on February 22, 1974.

That court granted Occidental’s motion to dismiss,

finding that:

1. The EEOC has no authority to file suit more

than 180 days after the filing of the underlying

charge, or where, as here, the charge was tiled

prior to the 1972 amendments to Title VII

of the Civil Rights Act of 1964. more than

1 80 days after the effective date of such amend

ments:

2. Alternatively, the EEOC was barred from filing

this suit by the California statute of limitations:

3. Alternatively, the EEOC was barred from pro

ceeding on paragraphs 8(b) and 9(c) of its

complaint because the allegations contained

therein were outside the scope of the underlying

charge: and

4. In any event, the EECc was barred from seek

ing back pay for any alleged violations occur

ring more than two years prior to the filing

of the underlying charge.

By its appeal herein, the EEOC challenges only

the first three findings by the court.

We

(

\ 42

link

nan:

(

stal.

C

( b N

star

The

the 1

'Ik

relcv:.

the e

a rich

...w-m s . -..... i : >■«• — «! ).Y,

•A ■,» •■): v •' . ■. S ; t#v•■'■■. " o . •

• ' " ' '< ■ - •. • :■ >•••; :• , ■ . ;. :.v y

.. - ’si \, f'r. *- .̂ .-/Ci-̂--*ûk».A» *..0*..».»...

•'’*'Vn;. ’■■ "

••",««;■ .i;.

.,’•. ’.v*v•.'•*;•• . • • • ;‘cv -*.. ■ ■■ ■ '■•'.■ .’*• y‘. *". '.«6uUJJw .

• '% /W

iI • ■ -;-.V ' t. "at: .7 -

. m & t

Ts. We hold:

jr (1) Tlie 180-dav language of Section 706(f)(1) [ .

os. [42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5 (f) (1) | does not constitute a i\ ■. ....

oh limitation upon the EEOC's ability to sue in its own f ■-C name; i" -

he (2) This action is not barred by any state by any r •'

ci- state limitations period; and J ‘ ' ‘ 7 !

(3) The EEOC properly included subparagraphs 8 1;

c

• 1 (b) and 9(c) in its complaint. 1 .■■c.;i • - . »-+.

II.

t • . . j. t .

r '■4. -s. THE 180-DAY LANGUAGE OF SECTION 706 i

■re (f)(1 )

“l 'T Section 706(f)(1) [42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(f) (1) ]

cd states in pertinent part:'

'll [ 11f within one hundred and eighty days \ ¥ ■

an from the filing of such charge . . . the j EEOC |

has not filed a civil action under this section

the [EEOC] . . . shall so notify the person L - ,

aggrieved and within ninety days alter the giving

of such notice a civil action may be brought

r];.f .1

o- against the respondent named in the charge (A) : ''

lr-

its by the person claiming to be aggrieved or (B)

;ed if such charge was filed by a member of the i. ..v

'ng [EEOC I. by any person whom the charge alleges

was aggrieved by the alleged unlawful employment

t ■ ' *

-A.“ practice. t • . - ■,i* • , • *■ < • * -

u r- The district court found that the above statute precluded

| j *■ i .r. . i ■

ng the EEOC from bringing this action.

f ■ 4; :vv

r

fnlv 'Before the 1972 amendment of Section 706( f ) (1 ) . the

relevant time periods were 30 days for both the filing of

the eh a rue with the EEOC, and filing suit after receipt of

a right-to-sue letter. f ■■

»' !.

« 1 ' ■Jt- y

■ I .. *V ,• 1 .■■■■•■,■• •• •';• T • . w V>. ; ‘i •-’ w v .. • .- - !;r ■ vVP» f ' -..• . ; i i-

'

' . •■■:

_______ ___________ I> ----Liii*.----- .— --------------

—4-

The statute on its face contains no express limitation

upon suit by the EEOC. Rather, it precludes civil

action by the charging party for 180 days so that

the EEOC may during that period pursue conciliation."

If, after 180 days, the EEOC has neither filed a

civil action nor achieved conciliation, the charging party

may demand a “right-to-sue” letter. On receipt of it,

the charging party has 90 days within which to sue.

Should such private action be filed, the EEOC would

apparently be restricted to intervention."

Fine

we ad

706(7

EEOC

that t

the bn:

/

i

However, should the person concerned choose not The

to sue during the allotted 90 days, the EEOC is not suit v.

prohibited from suing thereafter. The statute in no limit;"

way limits the time within which it must sue, so long §340f

as the charging party has not done so.'1 \yc

This issue has been before the Courts of Appeals

for the Third, Fourth. Fifth, Sixth, Eighth and Tenth

Circuits. All have ruled that Section 706(f)(1) [42

U.S.C. § 2000e-5 (f)(1 ) | does not preclude suit by

the EEOC after the ! 80-day period has run."'

"The charging party may sue before the 180-day period

has run if:

(a) The EEOC finds no reasonable cause during that

time period 142 U.S.C. S 2000e-5(b)]; or

(b) The EEOC dismisses the charge during that time

period i42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(f)( I )].

"H.R. Rep. No. 92-238. 92nd Cong.. 1st Scss. 12 (1971).

1972 U.S.C.C.A.N. 2148. quoted in Equal Employment Op

portunity Conwi'n v. Duval Carp., 528 F.2d 945, 948 n.4

(10th Cir. 1976).

'The sole exception is that the EEOC must wait 30 days

from the filing of the charge before filing suit. 142 U.S.C.

§ 2000c-5(f) ( I ) ] .

Equal Employment Opportunity Conun'n v. Duval Corp., 1

528 F.2d 945, 947 (10th Cir. 1976); Equal Employment

Opportunity Conmt’n r. Meyer liras. Duty Co., 521 F.2d 1364,

1365 (8th Cir. 1975); Equal Employment Opportunity Conmt'n

r. E.l. (luPont tie Nemours and Co.. 516 F.2d 1297 (3rd

[42 l

EEOC

privat

no oti

tion :

EEOC.

no gev

ploy in

51 1 F

(5th C

It :

ac tion

of lim

9

Cir. 19

herley-f

k ^ Equal I

V vide R

X Op port.

Cir. 19

r. Loe

827, 82

5

Nation

■ c i\ i J

' that

tion.'

!pj-J „

party

of it,

■ sue.

•voulci

e net

■s not

n no

> long

'peals

I'e nth

142

4 by

,'cri od

. that

time

'71).

Op-

n.4

days

S.C.

"cnr

••64.

m'n

-'rd

adopt't|!enr2 ir!l ir i7hV lV od '" 'i ty P‘irsUilsivi:"

7 0 6 ( f ) (1 ) docs no, c o n s t t a y ‘1nSU;,Se < * * * * »

EEOC’s a;-'.-., . ,tl,tL a ''nutation upon the

th a t the chstric " c o u r 10 ' Y - ' ” n a m e * VVe’ co n c lu d e

the basis of th« 180 d a v lCned bamng t,lis suit on80-day language in Section 706(f) ( I ) .

a p p l i c a b i l i t y OF RELEVANT STATE

LIMITATIONS PERIOD

- " - h o c

S r found caiif° r - « s s s

|4 ? 'u ' .s .c . i T o o o ^ T o n ? ) t 706ff><>)

EEOC 10 file suit within so ,1 T reC,“irc "K

private charge is filed with d n, a f <to,e ,he

"<> «lhcr portion of Title , 7 T " * being

,i0" « « limitation « « P‘lb = o P - 'c p re ta -

EEOC must bring suit we find ,, Which t>K

no governing federal i n , l , , c , ' c ,s simply

opgo,.,,,,;,,; r< ; °n; pc™ d: )« • ^

511 F.2d 456 45s „fg , " ' W Co.,

(J ib Or. 1975 ) 521 F.2d 223

It is well established that in

action, where Congress ho P W ? " civiI rights

Of limitations, the slate st iun "0t 7 ° Vlded a statute r .— (- V ^ F i t e statute jtpphed to simi| ;1|. |iti_

hi’r le v - c im i C o r f ! s n ’p ' n C o,un,‘n ~ 7 ~ fa ,~

*s.

LL

t- .A.r

fix

F . . .;

| • ■ ; ■ • ; jj . ■. •• *• *

f v ;

r »'

i

A

— 6—

uation vvill be applied to the federal action. Johnson

r. Railway Express Agency, Inc., 42! U.S. 454. 462

(1975), and eases cited therein; Griffin v. Pacific

Maritime Assn, 478 F.2d 1118, 1119 (9th Cir. 1973).

In its complaint the EEOC seeks both injunctive

relief and back pay. By its prayer for injunctive relief

the tEO C promotes public policy and seeks to vindicate

rights belonging to the United States as sovereign,

i hus. the EEOC's request for injunctive relief is not

subject to any state limitations period. Griffin Wheel,

supra, 51 J F.2d at 459; Kimberly-Clark, supra. 51!

F.2d at 1359-60. Cf. United Stares r. Summerlin, 310

U.S. 414 (1940). The district court erred insofar as

it barred EEOC's request for injunctive relief on the

basis of the California limitations period.0

We consider the request for back pay. Occidental

argues that, even though the EEOC is party plaintiff,

“ fi Insofar as the . . . suit constitutes a proper legal

conduit for the recovery of sums due individual citi

zens rather than the treasury, it is a private and not

a public action. United States v. Georgia Power, 474

F.2d 906. 923 (5th Cir. 1973). quoted in Griffin

Wheel, supra, 51 1 F.2d at 458.

Since we cannot agree that EEOC's request for

back pay must be treated as “private" in nature, we

believe the district court erred in applying the California

limitations period to bar the back pay request.

Our starting point is the recent statement of the

Supreme Court in Franks v. Bowman Transp. Co..

........ U.S............ 44 USLW 4356 (Mar. 24. 1976); * •

!:We express no opinion as to which, if any. state limitations

statute would apply had an individual or a class, rather than

the EEOC, been party plaintiff.

'•> \ ,.<V

--.nUiU...

“ | CI lair,

a majoi

44 USE

Analysis

tunity A

Rec. 7 1 (

The C

U.S. 40:

of Title '

As

Co.

I of

pOS'

an i

to :■

re a s

that

emp

evai

deav

_ vest;

in E

Indu

It

pers

of ur

Id. at 417

• •yA.Tt 'V' ; z-w. .r- y > gr v: - ; " ' ■

i .

•... t ■ ‘«i( I 5'n' -7) •? A •

. .. y‘i s'-i • a '• ■ :

C

■

' ' . -A

• r. £

v t\. - ■

....

: e-AA- . A - wE

:i

, . ... --L- I > ■**l,'liim»

• *••' ■*'<V ')1' :'. v / '. •” f '• •• : ■v,‘i \ '■ , • •*• '• 4. r. .

—7—

“ | C | laims under Title VII involve the vindication of

a major public interest. . . . ’ Id. at ....... n.40.

44 USLW at 4365 n.40, quoting Section-By-Section

Analysis, accompanying the Equal Employment Oppor

tunity Act of 1972—Conference Report, IIS Cong.

Rec. 7166. 7168 (1972).

The Court in Albermarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422

U.S. 405 ( 1975), discussed in some detail the nature

of Title VII claims for backpay:

As the Court observed in Griggs v. Duke Power

Co.. 401 U.S.. at 429-430, the primary objective

| of Title VII j was a prophylactic one:

“It was to achieve equality of employment op

portunities and remove barriers that have oper

ated in the past to favor an indentifiable group

of white employees over other employees."

Backpay has an obvious connection with this pur

pose. If employers faced only the prospect of

an injunctive order, they would have little incentive

to shun practices of dubious legality. It is the

reasonably certain prospect of a backpay award

that “provide|s| the spur or catalyst which causes

employers and unions to self-examine and to self-

evaluate their employment practices and to en

deavor to eliminate, so far as possible, the last

vestiges of an unfortunate and ignominious page

iii this country's history." United States v. /V. L.

Industries. Inc.. 479 F.2d 354, 379 (CAS 1973).

It is also the purpose of Title VII to make

persons whole for injuries suffered on account

of unlawful employment discrimination.

Id. at 417-18. (Emphasis added.)

'A-M ‘■K> r.K - ’UM

a - 2 A;;

: a '<■ <. , VC •*’i • , • -• .■- , -:

1 t ’ r-'l- Ws

■. '■■■ ■ g |f : : IS

i

! '

8—

/:■ i 0 M ' .v . ;

»

’ %

h

- J

i

. i

That an award of back pay promotes the primary

statutory objective of deterrence' was also noted by

the Sixth Circuit in Meadows v. Ford Motor Company,

510 F.2d 939, 948 (6th Cir. 1975 ).

The Moody Court noted that “ ] 11 he backpay pro-

vjjPon r • -'"•a,, v h i >--.c .-vnresslv modeled on the

backpay provision of the National Labor Relations

Act.” 422 U.S. at 419 and n .l l . It is established

doctrine that a back pay order under Section 10(c)

of the National Labor Relations Act j 29 U.S.C. ̂

160(c) | “ ‘is a reparation order designed to vindicate

the public policy of tire statute by making the employees

whole for losses suffered on account of an unfair

labor practice.’ ” National Labor Relations Board v.

J. H. Ratter-Rex Mfg. Co., 396 U.S. 258. 263 ( 1969),

quoting Nathanson v. National Labor Relations Boaid,

344 U.S. 25, 27 (1952).

It is true, of course, that whenever a party obtains

relief under a federal statute, public policy is vindicated

even though direct, immediately cognizable benefits

may flow only to the individual. Thus, for example,

private action under Title 42 U.S.C. $ 1981 is subject

to stale limitations periods despite the fact that each

recovery may be said to promote tne public policy

embodied in the statute. See Johnson, supra, 421 U.S.

454 ( 1975).

But certain federal acts, such as the National Labor

Relations Act, are intended to be broadly prophylactic

"The Court in Moody stated that

“backpay should be denied only for reasons which, if

applied generally, would not frustrate the central statutory

purposes^of eradicating discrimination throughout the econ

omy and making persons whole for injuries suffered

through past discrimination.

422 U.S. at 421. (Emphasis added.)

■Jo:

imary

•d by

\pany,

■ p ro

il the

a iions

:ished

10(c)

•C. §

dicatc

tyees

unfair

rd v.

969),

hull'd.

Otains

ieated

unci'its

.:r,ple,

abject

each

policy

i U.S.

Labor

; lactic

..eh, if

.atutory

e econ-

suffercd

-r-

— 9—

as well as remedial. See Section 1 | 29 U.S.C. § 151 j.

Several circuits, including our own, have recognized

that back pay orders promote the prophylactic as well

as the remedial purposes of the National Labor Rela

tions Act.'s

The National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) does

not pursue the "adjudication of private rights.” Rather,

it “acts in a public capacity to give effect to the

declared public policy of the Act. . . National

Licorice Co. v. National Labor Relations Board, 309

U.S. 350, 362 (1940). “The fact that these proceedings

| may j operate to confer an incidental benefit on private

persons does not detract from this public purpose.”

Nabors v. National Labor Relations Board, 323 F.2d

686, 688-89 (5th Cir. 1963).

Accordingly, the NLRB, as an agency of the United

States seeking enforcement of public rights, is not

bound by state limitations statutes even when seeking

back pay. Nabors, supra, at 688. See also ./. H. Rutter-

Rex Mfg. Co. v. National Labor Relations Board,

399 F.2d 356, 358, 362, 364 (5th Cir. 1968), rev’d

on other grounds, 396 U.S. 258 ( 1969).’

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 grew out of Congres

sional awareness of the continued, pervasive discrimina-

P I t ;'

vat

1$

•V„.v Vf*

I: .• \" ' i'< ■ •t t -v;l '

*Ut . V _ '• v ■ •| i

.

vi

* V 4 * i fv. ;■ :V

i cXXs

te r? -

r A 1

r W -

■sMarriott Carp. v. Rational Labor Relations Board. 491

F.2d 367, 371 (9th Cir. 1974); National Labor Relations

Board v. United Marine Division, Local 33, National Maritime

Union, AFL-CIO, 417 F.2d 865, 868 (2nd Cir. 1969); Trinity

Valley Iron R Steel Co. v. National Labor Relations Board,

410 F.2d 1161, 116S (5th Cir. 1969); Nabors r. National

Labor Relations Board, 323 F.2d 686. 688-89 (5th Cir. 1963).

'•‘In Rntter-Rex, after ruling that state limitations statutes

did not apply to the NLRB's action, the Fifth Circuit modified

the Board’s order because of inordinate administrative delay

to the prejudice of defendant. The Supreme Court reversed

and ordered enforcement of the back pay order in its entirety.

In doing so. the Court assumed the inapplicability of state

limitations periods.

—T" ,n-r wt->'

' ' , . ■ $ $ $ ■

.

fc&W;:r ' : v

r • . ,'\

f\ g • '

1 V i '

m '

\ &&

X ■, i ** I

L.>*'Vr T><r.»L .4.{■■: •w '

K •: T:y '

r-f-L

TT?rrr^#^.*!'v

‘ vi' ';?S\ * T •

- J O -

tion against minorities, particularly NegiO'-s, in vot.n_.

access to public facilities, public education and employ

ment. As the Committee on the Judiciary of the House

of Representatives reported:

Considerable progress has been made in elimi

nating discrimination in many areas. . . • Never

theless, in the last decade it has become increasing

ly clear that progress has been too slow and that

national legislation is required to meet a national

need which becomes ever more obvious. . . I This

Act] is designed as a step toward eradicating

significant areas of discrimination on a nationwide

basis. It is general in application and national .

in scope.

H. Rep. No. 914, 1964 U.S.C.C.A.N. 2391. 239a

(1964).

Thus, despite the existence in 1964 of such remedial

statutes as the Civil Rights Acts of 1866, 1870 and

1871 i 42 U.S.C. §§ 1981-881, Congress believed that

some additional federal action was necessary to further

the public objective of elimination of nationwide dis

crimination."' It decided that this objective could

best be pursued by federal agency enforcement.

The original Section 706 of the Civil Rights Act

of 1964, 78 Stat. 259-61, established an enforcement

scheme to be implemented primarily by the EEC» .

In 1972 Congress made it even more clear that tne

vast majority''of complaints will be handled through

the offices of the EEOC or the Attorney General. . . .

U.S.C. S 1981 o i l the one l i a n a ,

421 U.S. ai 461.

■ni.le VII on the oilier.

— I l —

Scction-By-Scction Analysis, supra. 1 ! 8 Conti. Rcc. at

7168. ,

The basic function of the EEOC, as with the NLRB,

is to prevent and eliminate unlawful employment “prac

tices and devices, primarily through “conference, con

ciliation, and persuasion." Alexander v. Gardner-Denver

Co.. 415 U.S. 36. 44 (1974): Section 706(a) &

(b) [42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(a) & (b ) | . The EEOC

has the power to investigate, promote voluntary com

pliance. and bring suit upon failure of conciliation

efforts."

The EEOC vindicates public policy by suing in

federal court, as does the NLRB bv seeking enforcement

of its orders in the courts of appeals. This is so

regardless of the type of relief sought by cither. As

in labor law. so in Title VII law. the fact that private

parties may benefit from public agency action does

not detract from the public nature of those proceedings.

We are aware that the Fifth Circuit has reached

a contrary result in at least two cases. Griffin Wheel,

supra. 51 1 r.2d at 458-59: Georgia Power, supra,

474 F.2d at 922-23. We decline to follow its lead.

Both of those cases were decided before the Supreme

Court decisions in Moody, supra, and Franks, supra.

Moreover, the court in Georgia Power, 474 F.2d at

921, relied on the decision of the Supreme Court

in Ruiter-Rcx, supra, but ignored the Court’s statement

therein that “back pay . . . is . . . desicncd to

vindicate . . . public policy. . . 396 U.S. at

263.

"Unlike the NLRB, the FEOC has no adjudicative powers.

Yet the NLRB must itself seek court enforcement of its orders.

X

1

I

3

I

i

■!I

j

Occidental directs our attention to the Court’s deci

sion in Johnson, supra. The Court there held that

a federal cause of action under Title 42 U.S.C. ̂ 1981

was governed by “the most appropriate | limitation

period | provided by state law.” 421 U.S. at 462.

However, Johnson involved a private claimant litigating

under Section 1981, while this case involves a public

agency enforcing Title VII rights.

Also, the Johnson Court did not qualify its holding

according to the type ot relief sought. Indeed, by

discussing the availability under Section 1981 of “both

equitable and legal relief,” 421 U.S. at 460. the Court

intimated that state limitations periods would apply

to private actions brought under Section 1981, regard

less of the type of relief sought.

Earlier in this opinion we joined the Fifth a^u

Sixth Circuits, in Griffin Wheel and Kimberly-Clark

respectively, in ruling that state limitations periods

do not govern the EEOC’s request for injunctive relief.

Nothing in Johnson dictates a contrary conclusion.

Similarly, Johnson does not preclude us from concluding

that a request by the EEOC for back pay, in vindication

of public policy, is likewise immune from state limita

tions1' periods.1:1

rhere are sound practical considerations in support

of our conclusion. First, subjecting the EEOC to state

’-It appears that the EEOC would likewise be immune

from the defense of laches. Cj. United Slates v. Summerlin,

310 U.S. 414, 416 (1940); Nabors v. National Labor Relations

Board, 323 F.2d 686, 688 (5th Cir. 1963). But see Griffin

Wheel, supra, 511 F.2d at 459 n.5; Georgia Power, supra,

474 F.2d at 923. However, since the issue was not raised

herein, we need not address it.

’ ’•The court in Kimberly-Clark seemed to so conclude, al

though it did not make clear what tvpe of relief was at issue

511 F.2d at 1359-60.

15 '

. _ "—r-— ------------ --------------- ------------------------- ------------ - ,

, : . ■ ■ ■ -v v ■:>.■. . . ■ a 4 • . - . ■ v ; :■ ■■•

■ ■ i C ■ ■ . . V' : v. ; • ■ • ' -V-

■ 06 04 .. V .7 Vie.

■ * ■ ' . . ii.,:7 ■ .. ■ >;

Court's dcci-

jre held that

J.S.C. § 1981

to (limitation

U.S. at 462.

,iant litigating

elves a public

,[y its holding

.. Indeed, by

1981 of "both

50, the Court

would apply

1981. regard-

,.'.e Fifth and

Kimberly-Clark

..lions periods

.junctive relief,

ry conclusion,

'oni concluding

. in vindication

in state limita-

ons in support

EEOC to state

wise be immune

cs v. Summerlin,

: Labor Relations

. But see Griffin

'a Power, supra,

: whs not raised

so conclude, al-

clief was at issue.

— 13—

limitations periods, often as short as one yeai, wou.d

frustrate its attempts to resolve disputes by means

of administrative "conference, conciliation, and pat-