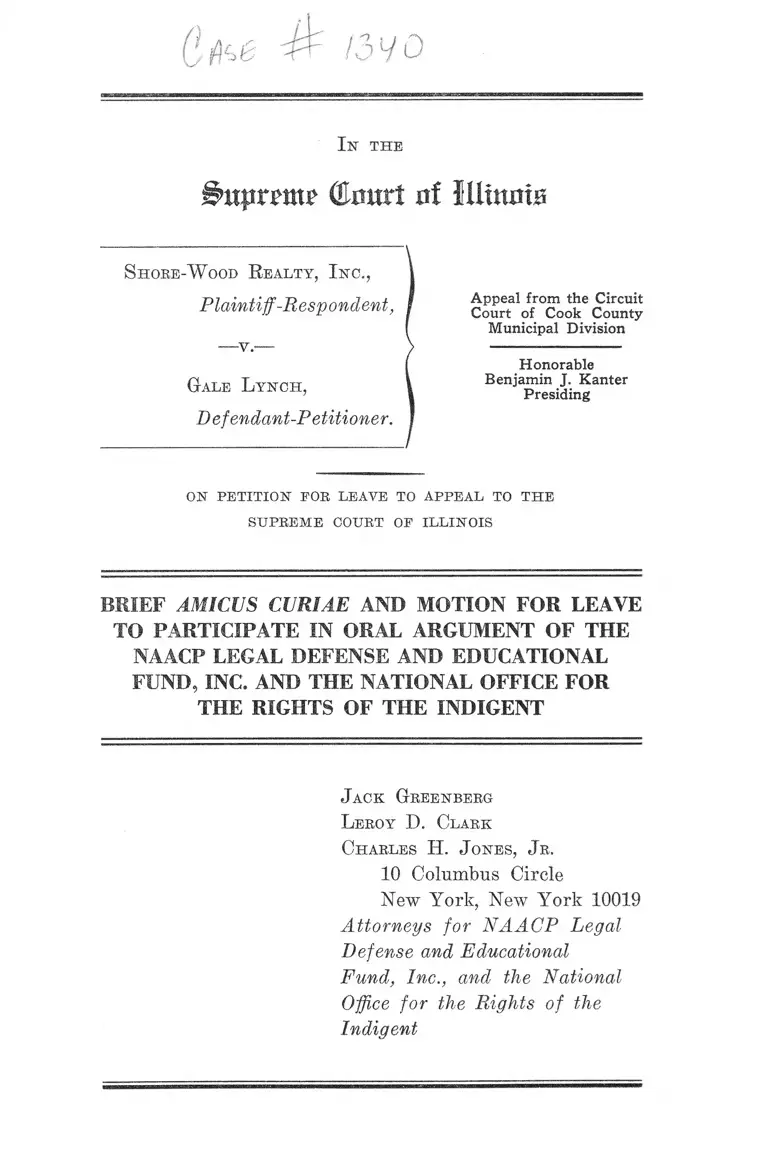

Shore Wood Realty Inc v Lynch Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1967

13 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Shore Wood Realty Inc v Lynch Brief Amicus Curiae, 1967. b0877c42-c49a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c2312974-acd9-4ab6-be74-7df236b115b5/shore-wood-realty-inc-v-lynch-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed March 05, 2026.

Copied!

(I fee ^ i3L/o

I n th e

Ihtpron* (tart nf lUimris

S hore-W ood R ealty , I n c .,

Plaintiff-Respondent,

G ale L y n c h ,

Defendant-Petitioner.

Appeal from the Circuit

Court of Cook County

Municipal Division

Honorable

Benjamin J. Kanter

Presiding

ON P E T IT IO N EOK LEAVE TO A PPE A L TO T H E

STJPBEME COURT OE IL LIN O IS

BRIEF AMICUS CURIAE AND MOTION FOR LEAVE

TO PARTICIPATE IN ORAL ARGUMENT OF THE

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL

FUND, INC. AND THE NATIONAL OFFICE FOR

THE RIGHTS OF THE INDIGENT

J ack Gbeenberg

L eroy D. Clark

Charles H. J ones, Jr.

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for NAACP Legal

Defense and Educational

Fund, Inc., and the National

Offi.ce for the Rights of the

Indigent

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Brief A micus Curiae page

Nature of the Case .................................................... 1

Points and Authorities .............................................. 1

Statement of Facts .................................................... 1

A rgument ............................................................................... . 2

Introduction ................................................................ 2

I. The Illinois Appeal Bond Statute, 111. Eev.

Stat. 1959, Ch. 57, Sec. 20, Violates the Four

teenth Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States, on its Face and as Applied to

Indigent Tenants .................................................. 2

Conclusion ................................................. ............................. 7

Motion for L eave to P articipate in Oral A rgument 9

Nature of the Case

This appeal is from a judgment rendered against the

defendant, Gayle Lynch, on July 24, 1967, in a summary

eviction.

Defendant’s theory of the case is that 111. Rev. Stat. 59

Ch. 57 Sec. 20 requiring a bond in order to file an appeal

is unconstitutional on its face and as applied to an indigent

tenant defendant.

Points and Authorities

Illinois Revised Statutes 1959, Chapter 57, Section 20

requiring the posting of a security bond on appeal violates

the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the

United States on its face and as applied to indigent tenants.

Griffin v. Illinois, 351 U.S. 12 (1956);

Harper v. Virginia State Board of Electors,

383 U.S. 663 (1966);

In Re Gault, 387 U.S. 1 (1967);

Roberts v. Lavallee, 36 L.W. 3171 (October 23,

1967) ;

Williams v. Shaffer, 385 U.S. 1037 (1967).

Statement of Facts

The amicus brief adopts the statement of facts contained

in the Petition For Leave To Appeal From The Appellate

Court To The Supreme Court filed by the Attorneys for

Defendant.

2

Argument

The issue raised in this case by amicus is : the right

of defendant and the class of indigent tenants she repre

sents, to proceed in forma pauperis either without posting

a security bond or alternatively to post a modest use and

occupancy bond in defending against eviction proceedings.

I.

The Illinois Appeal Bond Statute, 111. Rev. Slat, 1959,

Ch. 57, Sec. 20 , Violates the Fourteenth Amendment

to the Constitution of the United States, on its Face

and as Applied to Indigent Tenants.

Defendant recognizes that the U.8. Supreme Court in

National Union of Marine Cooks v. Arnold, 348 TJ.S. 37

(1954), upheld as constitutional a defendants’ bond pending

appeal. But the facts of that case can be distinguished

from the instant case. In National Union the evidence

showed that the defendant had no substantial assets in

the state of Washington but had $298,000 in United States

bonds in his possession in the state of California. The

defendants’ appeal was dismissed only after he refused

to obey a court order to deliver the bonds to the Court’s

receiver, for safe keeping pending disposition of defen

dants’ appeal.

In the instant case the defendant has no assets with

which to post a security bond in the amount set by the

trial court under 111. Rev. Stat. 1959, Ch. 57, Sec. 20.

There is no question of wanton disregard of the court

order in the instant case. Defendant in the instant case

is willing, in fact eager, to pay her rent into the registry

of the court a few days prior to the date due so that the

3

landlord may be protected against the loss of rent. De:

fendant is also willing to pay a reasonable amount to

protect the landlord for any damage that might occur to

his property during the litigation and to cover court costs.

It is submitted that the bond set by the trial court is

prohibitive and bears no reasonable relation to the risk

posed to the plaintiff in view of defendant’s willingness

to post a use and occupancy bond. The Illinois require

ment, in fact, is a penalty bond which requires the posting

of double rent, for more than is necessary to protect a

landlord from harm.

Although it may be perfectly proper for a court to

require some defendants to post a bond pending an ap

peal, a money bond cannot be demanded of an indigent

defendant. The Illinois requirement under 111. Rev. Stat.

1959, Ch. 57, Sec. 20, permits wealthy persons to stay in

rental housing and defend eviction proceedings fully,

whereas poor people have no opportunity to appeal a

decision even though there may be errors of law clearly

manifested on the record from the trial court which were

prejudicial to the substantial rights of the defendant.

As Justice Douglas said in Williams v. Shaffer, 385

U.S. 1037 (1967) (dissenting from the denial of a Writ of

Certiorari in a case challenging a Georgia statute re

quiring the posting of a bond prior to making a defense in

a dispossessory action) :

“ The poor are relegated to ghettos and are beset

by substandard housing at exorbitant rents. Because

of their lack of bargaining power, the poor are made

to accept onerous lease terms. Summary eviction pro

ceedings are the order of the day. Default judgments

in eviction proceedings are obtained in machine-gun

rapidity, since the indigent cannot afford counsel to

4

defend. Housing laws often have a built-in bias

against the poor. Slumlords have a tight hold on the

notion.”

In the instant case the indigent defendant was able to

obtain volunteer counsel but the ordinary member of the

class she represents is not so fortunate. Furthermore,

unless defendant can fully prosecute her appeal, it cannot

be said that she has had a full determination of the merits

of her case.

It may be that states can constitutionally enact some

legislation which creates a greater burden for the poor

than for the rich. For example, it may not be imper

missible for the states to charge fees for licenses of various

sorts, or to require tuition of students attending state

universities. But Griffin v. Illinois, 351 IT.S. 12, 17 (1956)

makes it clear that justice may not be sold.

Surely no one would contend that either a State or

the Federal Government could constitutionally pro

vide that defendants unable to pay court costs in

advance should be denied the right to plead not

guilty or to defend themselves in Court. Such a law

wTould make the Constitutional promise of a fair trial

a worthless thing. Notice, the right to be heard, and

the right to counsel would under such circumstances

be meaningless promises to the poor. . . . There is no

meaningful distinction between a rule which would

deny the poor the right to defend themselves in a trial

court and one which effectively denies the poor an

adequate appellate review accorded to all who have

money enough to pay the costs in advance. . . . There

can be no equal justice where the kind of trial a man

gets depends on the amount of money he has. 351 II.S.

, at 17-19. (Emphasis added.)

5

It is true that Griffin’s prohibition on economic discrim

ination by the state has been applied up to now chiefly

to the criminal process. See Burns v. Ohio, 360 U.S. 252

(1959). Smith v. Bennett, 365 U.S. 708 (1961). But the

equal protection clause, upon which Griffin was based,

applies as well to matters denominated “ civil” , and Harper

v. Virginia State Board of Elections, 383 U.S. 663 (1966),

invalidating the application of a poll tax to indigents,

demonstrates that the exercise of important rights other

than ones relating to the criminal process may not con

stitutionally be conditioned on ability to pay. See Williams

v. Shaffer (Douglas dissent). Furthermore, as pointed

out in In Re Gault, 387 U.S. 1 (1967) certain rights are

so fundamental and entitled to Constitutional protection

that their observance is not determined by the fact that a

proceeding is designated civil instead of criminal. There

is no rigid and inflexible line between criminal and civil

that never fluctuates despite the change in time and cir-

custance. Our constitution is a living document which calls

for contemporaneous construction which takes into con

sideration changing circumstances, new knowledge and a

greater recognition of basic human rights and needs.

In fact, the Supreme Court very recently reaffirmed the

principle of non-discrimination against the poor in the

legal process, in language which apparently applies to any

civil proceedings; “ Our decisions for more than a decade

now have made clear that differences in access to the

instruments needed to vindicate legal rights, when based

on the financial situation of the defendant, are repugnant

to the Constitution.” Roberts v. Lavallee, 36 L.W. 3171,

3172 (October 23, 1967). See also Williams v. Shaffer,

385 U.S. 1037, 1039 (1967).

This is perfectly sensible, since the ability to pay bears

no more rational relation to whether one has a bonafide

6

ground for an appeal from an eviction proceeding than it

does to whether there is a bonafide ground for the appeal

of a criminal conviction. In the former the indigent de

fendant may be deprived of a right or interest in property

whereas in the latter the indigent defendant may be de

prived of his life or liberty. In either event, all are basic

rights or interests protected by the United States Con

stitution. Under the equal protection clause the relevant

constitutional consideration is whether the bond require

ment bears a rational relation to a valid legislative purpose.

Assuming that the relationship between a bond require

ment and the protection of prevailing landlords from loss

of rent during protracted litigation is rational, the Illinois

statute requires too much of an indigent defendant. “ The

breadth of legislative abridgement must be viewed in the

light of less drastic means for achieving the same basic

purpose.” Shelton v. Tucker, 364 U.S. 479 (1960). See also

NAACP v. Alabama, 377 U.S. 288 (1964); Bates v. City

of Little Rock, 361 U.S. 516 (1960); McLaughlin v. Florida,

379 U.S. 184 (1964). Other simple devices exist by which

the state could safeguard both the landlord’s rent during

a suit and the tenant’s right to fully challenge the

eviction. The state of Illinois could permit tenants to pay

landlords their rent during the pendency of the proceed

ings, and condition the making of an appeal on the con

tinued payment of rent, rather than on the posting of a

large bond which indigents cannot raise. In cases of

dispute over whether or not rent has been paid, tenants

might be reluctant to continue to pay rent to the landlord

until the issue was resolved, but the court with juris

diction over the eviction suit could collect the rents for

the landlord or certify payments. Given these and other

alternatives, the Illinois statute, which is designed to pro

tect landlord’s rents, interferes too severely with the rights

of indigent tenants to obtain elemental justice.

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, 111. Rev. Stat. 1959, Ch. 57

Sec. 20 should be held unconstitutional in violation of the

Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution

on its face and as applied to an indigent tenant.

Respectfully submitted,

J ack G reenberg

L eroy D. Clark

Charles H . J ones, J r .

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for NAACP Legal

Defense and Educational

Fund, Inc., and the National

Office for the Rights of the

Indigent

9

I n t h e

^ttpron? (tart of llltturis

S hoee-W ood R ealty , I n c .,

Plaintiff-Respondent,

— v . —

G ale L y n c h ,

Defendant-Petitioner.

Appeal from the Circuit

Court of Cook County

Municipal Division

Honorable

Benjamin J. Kanter

Presiding

ON P E T IT IO N FOE LEAVE TO A PPE A L TO T H E

SU PBE M E COUKT OF IL L IN O IS

MOTION FOR LEAVE TO PARTICIPATE

IN ORAL ARGUMENT

The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.,

and the National Office for the Rights of the Indigent,

respectfully move this court for permission to participate

in oral argument. Movants recognize that such permis

sion is granted very infrequently; we submit, however,

that this is an extraordinary situation.

No amicus can truly speak for all the millions of persons

in need of legal services. But our unvarying objective has

been to extend legal services to those in need, and we feel

that we can help inform this court about that need and

the ways in which it might be satisfied.

10

W herefore, m ovants resp ectfu lly request p erm ission to

partic ip ate in ora l argum ent.

B esp ectfu lly subm itted,

J ack G reenberg

L eroy I). Clark

Charles H . J ones, J r .

10 Columbus Circle

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for NAACP Legal

Defense and Educational

Fund, Inc., and the National

Office for the Rights of the

Indigent

MEILEN PRESS INC. — N. Y. C«S ig** 219