Defendant-Intervenor's Answer to Emergency Motion

Public Court Documents

3 pages

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Milliken Hardbacks. Defendant-Intervenor's Answer to Emergency Motion, 3ba1e0ca-53e9-ef11-a730-7c1e5247dfc0. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c245aa96-791f-4d65-bf62-4fc35e55a6e3/defendant-intervenors-answer-to-emergency-motion. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

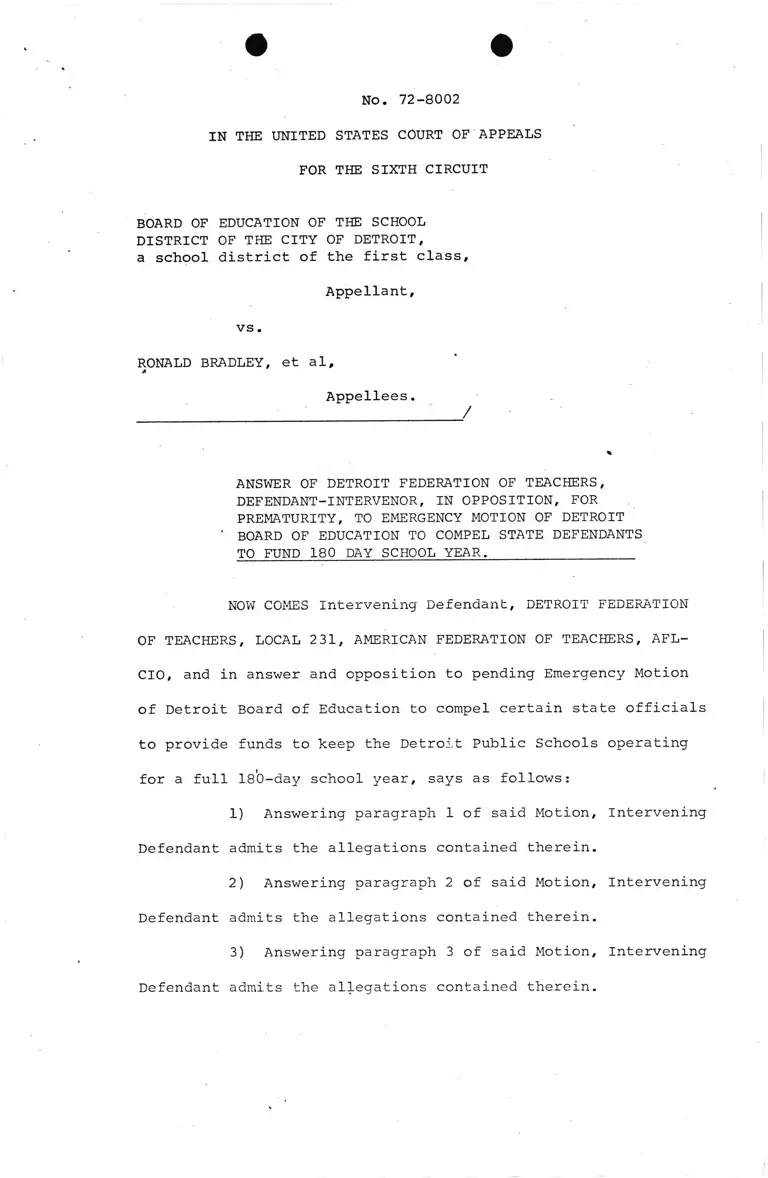

NO. 72-8002

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE SIXTH CIRCUIT

BOARD OF EDUCATION OF THE SCHOOL

DISTRICT OF THE CITY OF DETROIT,

a school district of the first class,

Appellant,

vs.

RONALD BRADLEY, et al,

4

Appellees.

/

ANSWER OF DETROIT FEDERATION OF TEACHERS,

DEFENDANT-INTERVENOR, IN OPPOSITION, FOR .

PREMATURITY, TO EMERGENCY MOTION OF DETROIT

' BOARD OF EDUCATION TO COMPEL STATE DEFENDANTS

TO FUND 180 DAY SCHOOL YEAR.________________

NOW COMES Intervening Defendant, DETROIT FEDERATION

OF TEACHERS, LOCAL 231, AMERICAN FEDERATION OF TEACHERS, AFL-

CIO, and in answer and opposition to pending Emergency Motion

of Detroit Board of Education to compel certain state officials

to provide funds to keep the Detroit Public Schools operating

for a full 180-day school year, says as follows:

1) Answering paragraph 1 of said Motion, Intervening

Defendant admits the allegations contained therein.

2) Answering paragraph 2 of said Motion, Intervening

Defendant admits the allegations contained therein.

3) Answering paragraph 3 of said Motion, Intervening

Defendant admits the allegations contained therein.

/

4) Answering paragraph 4 of said Motion, Intervening

Defendant admits the allegations contained therein.

5) Answering paragraph 5 of said Motion, Intervening

Defendant admits the allegations contained therein.

6) Answering paragraph 6 of said Motion, Intervening

Defendant admits the allegations contained therein on information

and belief, except that Intervening Defendant Federation denies

the conclusions that the Detroit Board cannot keep the schools

open through February, 1973.

7) Answering paragraph 7 of said Motion, Intervening

Defendant admits the allegations contained therein qn information

and belief.

8) No answer is required.

9) Answering paragraph 9 of said Motion, Intervening

Defendant admits the allegations contained therein.

10) Answering paragraph 10 of said Motion, Intervening

Defendant admits only that the recited recommendations of

Dr. Wolfe were made and that the Board Resolution pursuant

thereto was adopted but denies the conclusions that the Detroit

Board cannot or should not continue the school year without

the proposed mid-semester closing.

11) Answering paragraph 11 of said Motion, Intervening

Defendant neither admits nor denies the allegations in the first

sentence, for lack of information. The Federation denies the

allegations in the second sentence as inaccurate conclusions of

fact and law.

12) Answering paragraph 12 of said Motion, Intervening

Defendant admits the allegations contained therein.

T

13) Answering paragraph 13 of said Motion, Intervening

Defendant neither admits nor denies the allegations contained

therein, not having sufficient information thereof.

14) Answering paragraph 14 of said Motion, Intervening

Defendant admits the allegations contained therein.

15) No answer is required.

16) Answering paragraph 16 of said Motion, Inter

vening Defendant admits the allegations contained therein.

17) No answer is required.

WHEREFORE, we pray that said Motion be denied, on

account of prematurity, or in the alternative, that it be held

in abeyance.

Respectfully submitted,

ROTHE, MARSTON, MAZEY, SACHS,

O'CONNELL, NUNN & FREID, P.C.

By: ____________ _______ _________

Theodore Sachs

Attorneys for Intervening Defendant,

Detroit Federation of Teachers

1000 Farmer Street

Detroit, Michigan 48226

Telephone: 965-3464

Dated:

- 3 -