Franklin v. Giles County, VA School Board Brief and Appendix on Behalf of Appellant

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1965

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Franklin v. Giles County, VA School Board Brief and Appendix on Behalf of Appellant, 1965. 82c83153-b29a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c2550611-62a8-4f9a-88a9-67534f465e31/franklin-v-giles-county-va-school-board-brief-and-appendix-on-behalf-of-appellant. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

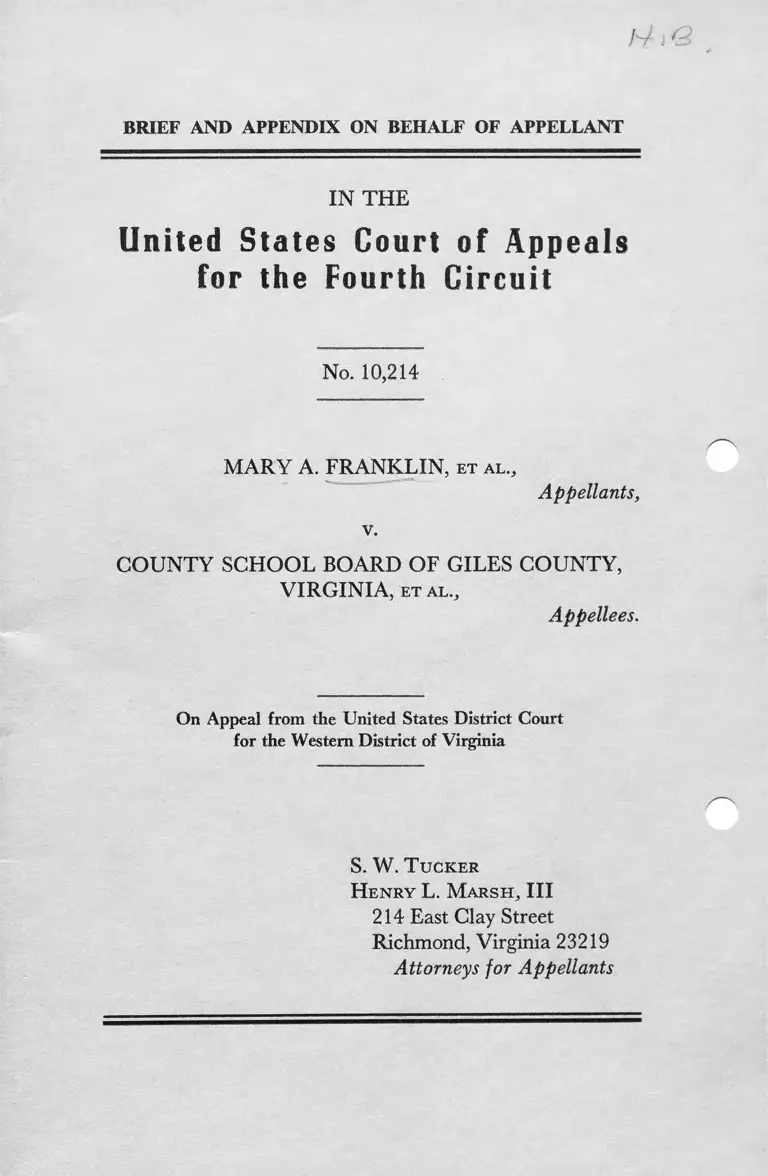

BRIEF AND APPENDIX ON BEHALF OF APPELLANT

IN TH E

United States Court of Appeals

for the Fourth Circuit

No. 10,214

MARY A. FRANKLIN, et a l ,

Appellants,

v.

COUNTY SCHOOL BOARD OF GILES COUNTY,

VIRGINIA, ETAL,

Appellees.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Western District of Virginia

S. W. T ucker

H enry L. M arsh, II I

214 East Clay Street

Richmond, Virginia 23219

Attorneys for Appellants

Page

St a t e m e n t of t h e C a s e ....................................................................................... 1

T h e Q u e s t io n P r e s e n t e d ................................................................................ 3i

St a t e m e n t o f F a c t s .............................................................................................. 3

A. The Dismissal of Plaintiffs..................................... - ................ 3

B. The Hiring of New Teachers.................................................. 4

A r g u m e n t ............................................................................................ 10

I. The Pleadings and the Evidence Require A Finding That

Plaintiffs Were Denied Re-employment Solely Because of

Their Race........................... -.................................................. 10

II. Nothing Short of Reinstatement Will Redress the Depriva

tion of the Plaintiffs’ Constitutional Rights............................... 12

C o n c l u s io n ............................................................................................................... 15

TABLE OF CITATIONS

Cases

Corbin v. County School Board, 177 F. 924 (4th Cir. 1949) ......... 13

Griffin v. County School Board of Prince Edward County, 377 U.S.

218.................................................................................................. 14

State ex. rel. Anderson v. Brand, 303 U.S. 95 (1938) ..................... 14

Todd v. Joint Apprenticeship Committee of the Steel Workers of

Chicago, 223 F. Supp. 12 (N.D. 111. 1963) ................................ 14

Watson v. Burnett, 216 Ind. 216, 23 N.E. (2d) 420 (1939) ........... 14

Wieman v. Updegraff, 344 U.S. 183 (1952) ...................................... 14

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

28 United States Code 1343 ............................................................... 13

29 United States Code 160 ........................... .......... ..... ........... ....... 15

42 United States Code 1983 ........................................................ ..... . 12

Civil Rights Act of 1964, Section 604 ..................................... .......... 15

Civil Rights Act of 1964, Section 706 .......................... ................... 15

INDEX TO APPENDIX

Complaint....................... 1

Request for Admissions.............................................................. 7

Answer to Request for Admissions ................................................... 8

Excerpts from Transcript of Trial Proceedings.......................... ..... 9

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit No. 4 ..................................................... ............... 13

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit No. 5 ........... 14

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit No. 6 ........................... ............................... ......... 21

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit No. 7 ......... ................................. .................. ....... 23

Statement of Position of Plaintiffs .................................................. . 24

Opinion of District Court ................................................................. 25

Order of District Court..... ......... ........... .................................. ......... 37

Notice of Appeal.... ............................................................................ 39

Other Authorities

IN THE

United States Court of Appeals

for the Fourth Circuit

No. 10,214

MARY A. FRANKLIN, e t a l .,

v.

Appellants,

COUNTY SCHOOL BOARD OF GILES COUNTY,

VIRGINIA, ET AL.,

Appellees.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Western District of Virginia

BRIEF ON BEHALF OF THE APPELLANTS

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

This litigation was commenced on July 29, 1964, by the

complaint of the seven Negro teachers who, until the close

of the 1963-64 school session, had constituted the faculties

of the Negro elementary and high schools of Giles County,

Virigina, which schools were then and thereafter to be

terminated. Joined as plaintiff, and seeking relief on behalf

of its constituents, was the Virginia Teachers Association,

Incorporated, which is composed of those members of the

teaching profession residing in the State of Virginia who

are Negroes. Alleging that the defendants, the County

2

School Board of Giles County and its Division Superin

tendent of Schools, had elected to dispense with the services

of the plaintiff teachers solely because of their race, the

individual plaintiffs sought a mandate requiring their rein

statement as teachers in the public school system of Giles

County during the 1964-65 session and other and general

relief.

The defendants’ motion for summary judgment and mo

tion to dismiss, filed on August 3, were denied at a pre-trial

conference held on October 3, 1964. The case was heard on

its merits on December 28, 1964, and, in response to the

request of the Court, counsel for the respective parties filed

briefs on February 15, and presented oral argument on

M arch 11, 1965. On June 7, the District Judge filed his

opinion dated June 3, 1965, finding that the action of the

Superintendent “deprived these teachers of their rights

under the Fourteenth Amendment.” By a “Statement of

Position of Plaintiffs” filed on June 22, counsel urged that

“the Court should place these plaintiffs as nearly as possible

in the position they would have held but for the School

Board’s unconstitutional action” and that “ [ijnasmuch as

the normal relief would be reinstatement, the burden should

be placed on the defendants to demonstrate that such relief

should not now be given.” (App. 25.)

The order of the District Court, entered June 23, 1965,

does not direct the reinstatement of the plaintiff teachers

or afford them any certainty that they or any of them will

ever again be employed as teachers in the Giles County

school system. Relief to them as individuals was limited to

an assurance of an opportunity to make application for

any teaching position which may become vacant during

the next two years and the further opportunity, in this

action, to obtain judicial review of the Superintendent’s

decision with respect to the several applications for such

position. (App. 38.)

3

On July 23, 1965, the plaintiffs filed notice of their appeal

to this Court from the order of the District Court insofar

as it fails to require the school board to employ the individ

ual plaintiffs as teachers in the public school system of Giles

County, Virginia. (App. 40.)

THE QUESTION PRESENTED

Does the “Act To Enforce The Provisions Of The Four

teenth Amendment” contemplate the reinstatement of a

teacher whom the school board refused to reemploy solely

because of race?

STATEMENT OF FACTS

A. The Dismissal of Plaintiffs

As the 1963-64 school session drew to a close, all of Giles

County’s approximately 125 Negro children of public school

age were attending the Bluff City Elementary School or the

Bluff City High School, the faculties of which consisted of

the seven individual plaintiff teachers. Never had Negro

children attended public school with white children; neither

had any Negro been employed to teach white children in

the public schools.

However, between M arch 15 and April 30, 1964, twenty-

three Negro children had made application to the state’s

Pupil Placement Board that they be assigned to the Giles

County High School. Thus faced with the ominous prospect

that white and colored children would attend the same

school, the School Board at its meeting of May 5, 1964,

ordered the discontinuance of the Bluff City schools for

Negroes and directed the Division Superintendent to notify

each of the seven Negro teachers that his services would

not be needed after the close of the 1963-64 session.

The discontinuance of one or more public schools was

not a new experience. But the abrupt termination of the

4

employment of the teachers at a school so discontinued was

without precedent. These facts and their significance are

discussed in the opinion of the District Court, viz.:

“ [T ]he record shows that on a number of occasions

throughout the period preceding the closing of the Negro

schools consolidations of white schools were carried out and

in each instance the white teachers whose schools had been

closed were retained in the school system. The earlied aban

donments indicate to me that the Superintendent had fol

lowed a policy of using teachers from the abandoned schools

in other schools in the system because he viewed the system

as basically homogeneous, by which I mean that in normal

circumstances he would transfer teachers between the var

ious schools to suit the needs of the system rather than con

sidering the teachers in the abandoned schools as unem

ployed and potentially available for any openings that might

occur in the other schools. There are other indications of

this policy in the record. Teachers have been shifted from

school to school when and as needed. This system of shifting

faculty personnel must have been used widely in the school

years immediately prior to and following the 1962-63 school

year when thirteen elementary teachers were eliminated

to remedy the overstaffing in the elementary schools which

had resulted from the series of consolidations. In order to

adjust to an overstaffed condition and then to readjust fol

lowing the elimination of that problem the system and the

faculty must have had a great deal of flexibility in assign

ments.” (App. 30.)

B. The Hiring of New Teachers

At least four elementary teachers, three high school

teachers of English and/or Social Sciences, and one high

school science teacher were employed effective with the

commencement of the 1964-65 session. All of these new

5

employees were white. The qualifications of six of these

newly employed teachers and the contrasting qualifications

of the seven plaintiff teachers, as revealed by the evidence,

will be next shown.

Carolyn Chaffin Johnston, race white, age 25, was em

ployed in September, 1964 to teach the third grade. She

was not a college graduate and had no previous teaching

experience. She merely held a Special License, having been

certified by the State Board to teach specific area subjects.

(App. 14, PL Ex. 5.) Concerning her, the Superintendent

testified:

“Carolyn Johnston did her practice teaching at Pearis-

burg Elementary School in the immediate preceding

school year 1963-64. At the time she made applica

tion she listed that she would be a graduate from

Radford College in the summer of 1964. I, as I recall,

had interviewed her as I had interviewed a number

of teachers previous to the actual close of the Negro

schools and had made a commitment to Carolyn

Johnston for employment. The observation of her

principal, her supervising teacher and my supervisor

indicated that she would be a very good teacher. . . .

She is listed as not a graduate because she had dif

ficulty with biology, a subject that is not at all kin

to the elementary work she is teaching. She ended up

with passing biology but she ended up with not

enough quality points to be a graduate.

* * 1 *

“. . . I made a commitment to this lady for employ

ment.

* * *

“ [T ]he lady was at work two weeks before I knew

she wasn’t a college graduate when I got into the

matter of getting a certificate for her.” (Tr. 66, 67.)

* * *

6

“We made commitments for employment when we

believed that she would be a degreed person.” (Tr.

92.)

By way of contrast, the evidence (A. 13, PI. Ex. 4) shows

that each of the individual plaintiffs had a Collegiate Pro

fessional Certificate, four of them being endorsed for Ele

mentary Education, and that the teaching experience of the

four having Elementary Education ranged from four to

forty years.

Dorothy Harvey, race white, age 23, was employed in

September, 1964, to teach the third grade. She held a

Collegiate Professional Certificate endorsed for History and

English, and had no previous teaching experience. (App. 14,

PI. Ex. 5.) Concerning her, the Superintendent testified:

“Mrs. Dorothy Harvey had been promised work in

January of 1964.

* * *

“I made a commitment to her. I finally did not place

her in the area of certification but in an area in which

she is doing a satisfactory job.” (Tr. 90, 91.)

* * *

“The understanding that I had with Mrs. Harvey was

that she would be considered for such vacancies as

occurred.” (Tr. 99.)

Four of the plaintiffs had Collegiate Professional Cer

tificates endorsed for Elementary Education and had pre

vious teaching experiences which ranged from four to forty

years. Moreover, the plaintiff Sylvia J. Harvey, whose Col

legiate Professional Certificate was endorsed for Social

Science had five years’ experience and the plaintiff, Spivey,

whose Collegiate Professional Certificate was endorsed for

Business Education and Social Studies, had completed one

7

year of employment in the system when Dorothy Harvey

was employed. (App. 13, PI. Ex. 4.)

Grover DeHart, race white, age 30, sex male, was em

ployed in September 1964 to teach the seventh grade. He

had no previous teaching experience and did not hold a

Collegiate Professional Certificate. His Collegiate Certifi

cate was endorsed for Elementary Education, Sixth and

Seventh Grades. (App. 14, PI. Ex. 5.) The Superintendent

testified:

“Grover DeHart has lived all the time in the county

and a former employee of industry who made himself

available early in the school year of 1963-64, went to

summer school and is well qualified in his area of in

struction having been a personnel—having worked with

personnel with a major in sociology.” (Tr. 92.)

The vacancy which Grover DeHart was employed to fill

would not have occurred except for the decision not to re

employ any of the seven Negro teachers, four of whom had

objective qualifications for teaching elementary education

which were superior to those of Grover DeHart.

Nancy Morgan, race white, age 33, was employed in

September 1964 to teach the first grade. She held a Col

legiate Professional Certificate, the subject endorsement

on which was Art. She had had two years’ previous teaching

experience. (App. 14, PI. Ex. 5.) The Superintendent testi

fied:

“Nancy’s Morgan’s home has always been in Narrows.

Her teaching experience has been in eastern Virginia

and I am not certain whether it was in the City of

Norfolk, Norfolk County, or Princess Anne. She had the

misfortune of having her home broken up and she came

home. She wanted an assignment the previous school

year but I had none for her.” (Tr. 77, 78.)

* * *

8

“Mrs. Nancy Morgan although she was certified in art

had done all of her teaching in eastern Virginia as a

primary teacher in the area in which I placed her. I had

made a commitment to her as early as July in the pre

vious year but did not find a job for her the previous

year and she served as a substitute during that year, the

year previous to this year.” (Tr. 91.)

No objective consideration was suggested for withholding

preference for this position from either of the four Negro

teachers who were certified in Elementary Education and

who had teaching experience which ranged from four to

forty years. (App. 13, PL Ex. 4.)

Ann Shelton, race white, age 43, was employed in Sep

tember 1964 to teach English at Giles High School. She had

three years’ previous experience. Her Collegiate Professional

Certificate was endorsed for English, History, Social Studies

and Latin. (App. 22, PI. Ex. 6.) As to her the Superin

tendent testified:

“Mrs. Ann Shelton had not worked under my super

vision. She had done extensive substitute work in my

period of time in the county and had been promised an

assignment. I might mention that she and her husband

had run a variety store and they had made the decision

to close the business and it made her available for sub

stitute and full time teaching.” (Tr. 89.)

The plaintiff Franklin was certified in English and Social

Science in high school and had forty years’ teaching

experience. The plaintiff Leftwich was certified in English

and had eighteen years’ experience which included the

teaching of English in Giles County. The plaintiff Woodliff

was certified in English and had four years’ teaching ex

perience which included the teaching of English in Giles

County. (App. 13, PI. Ex. 4.)

9

Helen Blankenship, race white, age 23, was employed in

September 1964 to teach Mathematics and General Science

in the eighth grade at Narrows High School. Her Collegiate

Professional Certificate was endorsed for Biology and Chem

istry. She had no previous teaching experience. (App. 24,

PI. Ex. 7.) The Superintendent had this to say concerning

her:

“I feel that in fairness since I was questioned about

Helen Blankenship that I would like to make a state

ment about her status. I committed myself to her as

early as last January but actually she was placed the

day before school opened after a principal at Narrows

High School resigned and after it was necessary for me

to reshuffle my faculty there and I had no math person

at that time who was available. She was certified in

Science. She was a graduate of Narrows High School

and as a student had done an outstanding job in math.

We had no hesitancy that she would not do a good job

in m ath.” (Tr. 71.)

* * *

“Her mother is a teacher.

* * *

“She is not certified in mathematics.

* * *

“She is teaching eighth grade general math which is

arithmetic.” (Tr. 77.)

Two of the seven Negro teachers (Leftwich and Woodliff)

were teaching Mathematics when the School Board decided

not to reemploy them. Two others (Montgomery and

Austin) had certification similar to that of Helen Blanken

ship and, in addition, had eight years’ and three years’ teach

ing experience, respectively. (App. 13, PL Ex. 4.) The fail

ure to retain the Negro teachers (as earlier the thirteen white

elementary teachers had been retained (Tr. 72-77, 102-

10

103)) created the occasion for the last minute employment

of Helen Blankenship.

ARGUMENT

I

The Pleadings And The Evidence Require A Finding That Plaintiffs

Were Denied Re-employment Solely Because Of Their Race

The District Court erroneously perceived the question

before it as being whether, in reaching the conclusion that

the seven Negro teachers were less suitable for re-employ

ment than any of the 179 white teachers, “the Superintend

ent exercised his discretion in such an arbitrary, capricious or

unlawful manner as to violate these teachers’ rights under

the Fourteenth Amendment.” (App. 29, 30.) By considering

that as the question (and painstakingly concluding “that the

scope and nature of the Superintendent’s evaluation of these

teachers was arbitrary and resulted in a discrimination

against them” (App. 31 )), the District Court avoided de

cision of the factual issue tendered by the pleadings which,

at the outset of the opinion, had been correctly assessed,

viz.: “The gist of the complaint is the allegation that the

seven individual plaintiffs were denied re-employment as

teachers by the defendants for the 1964-65 school session

because of their race.” (App. 26.)

Neither by their motion to dismiss nor by their answer

did the defendants suggest that the Superintendent made any

evaluation of the plaintiff teachers at any time. The District

Court’s opinion (App. 31) notes that “the Superintendent

did not explain why these teachers were not evaluated and

compared with all of the other teachers in the system who

taught in areas in which the plaintiffs could teach in ac

cordance with his prior practice in making these decisions.”

Further, there was “evidence offered by the plaintiffs that

11

in fact there never was a real evaluation of teaching qualifi

cations and that in deciding to discharge all seven of these

teachers the Superintendent considered only the closing of

the Negro schools.” The opinion continues: “There is evi

dence from which such a conclusion could be inferred. The

letter sent to the individual plaintiffs refers solely to the abo

lition of their jobs because of the closing of the Bluff City

schools without any reference to an evaluation or to any

possibility that they could be employed in the previously

all-white schools.” (App. 31, 32.)

To avoid meeting the crucial factual issue in the case,

the District Court undertook to discuss the adequacy of an

“evaluation” which the pleadings do not mention and which,

according to the evidence, simply did not occur.

The allegation of Paragraph 12 of the Complaint that

“ [t]he defendants elected to dispense with the services of

[the individual plaintiffs] . . . solely because they are

Negroes . . .” (App. 5), although formally denied in the

answer, was clearly established. The affidavit of the Super

intendent of Schools, filed August 19, 1964 in support of the

defendants’ motion for summary judgment, concludes in

these words:

“When the relatively few Negro children being taught

by these plaintiffs in separate schools were assigned to

the previously all-white schools, availability of teaching

positions for the plaintiffs no longer existed in a school

system which has been employing fewer teachers each

year for the past five years.” (App. R. 11.)

The plaintiffs’ request for admissions established that on

May 15, 1964, the Superintendent of Schools notified each

of these teachers that the closing of the Bluff City schools

and the placement of the Negro children in other schools

12

“make it necessary to abolish your job.” The letters of

notification concluded with these words: “May I take this

opportunity to thank you for the years of service rendered

the School Board of Giles County and the children of your

race.” (App. 7.)

The opinion of the District Court points out that, in view

of the Superintendent’s awareness that there would be

vacancies for the 1964-65 session, “his abrupt termination

of the employment of these plaintiffs is suspect. It certainly

must be contrasted with the termination of the thirteen

white elementary teachers in 1962-63 who defendants stated

in their brief then formed a ‘pool’ against future needs.

* * * It does appear that several of the individual plaintiffs

were better qualified considering only their certification and

experience than some of the people who were subsequently

hired.” (App. 32.)

The complaint and the evidence require the unequivocal

statement of an unavoidable finding of fact, viz.: that the

defendant School Board terminated the employment of

the plaintiff teachers and declined to reemploy them in the

Giles County school system solely because of race and

color. It is that actual occurrence (not the imagined but

nonexistent “evaluation” ) which the Court is called upon

to redress.

II

Nothing Short Of Reinstatement Will Redress The Deprivation Of

The Plaintiffs’ Constitutional Right

Unquestionably, a state may not refuse to employ any

individual solely because of his race. The District Court’s

opinion observed that “ [t]he defendants, while denying

that they discriminated against these individuals, acknowl

edge that the Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution

of the United States forbids discrimination on account of

13

race by a public school system with respect to the employ

ment of teachers.” (App. 26, 27.) If, as has been shown, the

School Board did in fact refuse to re-employ the plaintiff

teachers solely because of their race, then the only question

of law confronting the Court is the measure of relief to

which they are entitled.

When, in 1871, the Congress passed “An Act to Enforce

the Provisions of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Con

stitution of the United States” (42 U.S.C. 1983), it ordained

that if a person under color of state law, custom or usage

subjected any person to the deprivation of rights, privileges

and immunities secured by the Constitution, the person so

offending shall be liable to the party injured in a “proper

proceeding for redress.” The district courts have original

jurisdiction to “redress the deprivation” under color of

state law, custom and usage, of any right, privilege or im

munity secured by the Constitution (28 U.S.C. 1343). This

Court has succinctly stated the intent of the Congress, viz.:

“Whenever the forbidden racial discrimination rears its

head, a solemn duty to strike it down is imposed upon the

Court” (Corbin v. County School Board, 111 F. 924, 928

(4th Cir. 1949)).

Forbidden racial discrimination reared its head in the

Giles County school system on May 14, 1964, when the

School Board decided to dispense with the services of the

seven Negro teachers pursuant to its custom which pre

cluded the employment of Negroes as teachers for white

children. Because she is a Negro, the plaintiff Franklin, a

resident of Pearisburg in Giles County, must travel to

Bedford County (at least 75 miles) for professional em

ployment (Tr. 4, 6). Because they are Negroes the other

plaintiffs are denied professional employment in Giles

County. That forbidden racial discrimination continues be

cause the District Court failed to grant the only relief by

14

which the deprivation of the plaintiffs’ rights could be

effectively redressed.

The propriety of a mandatory injunction directing rein

statement of a teacher whose statutory protection against

the denial of re-employment was breached is discussed in

Watson v. Burnett, 216 Ind. 216, 23 N.E. (2d) 420 (1939).

There, as here, the invasion of the right would not sustain

an action for compensatory damages. There the court stated

and followed the rule which has been applicable in this

case ever since August 19, 1964, when the defendants filed

the affidavit of the Superintendent of schools (R. 10) in

dicating that availability of teaching positions for Negroes

ceased to exist upon the assignment of the Negro children

to previously all white schools, viz.:

“Where the rights of a party are clear and where ac

tion rather than inaction is essential to maintain the

status quo of the parties and to avoid irreparable in

jury, a court of equity may properly issue a temporary

mandatory injunction.” (23 N.E. (2d) at 424)

In State ex rel Anderson v. Brand, 303 U.S. 95 (1938)

the Supreme Court reviewed the Indiana court’s refusal of

a writ of mandamus to compel reinstatement of a teacher

and held that the repeal of the Teacher’s Tenure Law was

an unconstitutional impairment of the obligation of con

tracts. In Wieman v. Updegraff, 344 U.S. 183 (1952), the

Court reversed the denial of the school teachers’ prayer for

a mandatory injunction directing state officers to pay their

salaries notwithstanding the teachers’ failure to take a

loyalty oath, the Court having determined that the require

ment of such oath violated Fourteenth Amendment rights. In

Todd v. Joint Apprenticeship Committee of the Steel

Workers of Chicago, 223 F. Supp. 12 (N.D. 111. 1963), a

15

mandatory injunction issued to require that Negroes be

admitted to an apprenticeship program and be employed,

the court having found that governmental involvement in

their exclusion brought the plaintiffs within the protection

of the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments.

In recent years the Congress has directed that persons

wrongfully discharged from employment in certain indus

tries be reinstated. See 29 U.S.C. § 160(c), authorizing the

National Labor Relations Board “to take such affirmative

action including reinstatement of employees with or with

out back pay, as will effectuate the policies” of Subchapter

II of the Labor Managament Relations Act. See also the

Civil Rights Act of 1964, Section 706 (42 U.S.C. § 2000

e-5 (g))> where judicial authority to order reinstatement

is preserved if the individual was “expelled or was refused

employment or advancement . . . on account of race, color,

religion, sex or national origin.”

If ever there was justification for reluctance on the part

of a Federal court to enter a mandatory injunction when

nothing else would effectively redress the deprivation of

rights secured by the Constitution, that justification ceased

to exist when the Supreme Court delivered its May 25, 1964,

opinion in Griffin v. County School Board of Prince Edward

County, 377 U.S. 218.

CONCLUSION

It is fairly predictable that as more and more school

boards adopt “freedom of choice” plans for racial desegre

gation in efforts to satisfy the requirements of the Depart

ment of Health, Education and Welfare, an increasing

number of localities will be faced with the transfer of Negro

children from all-Negro schools. By virtue of Section 604

of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, the Department of Health,

16

Education and Welfare considers itself powerless to pro

tect Negro teachers against unwarranted loss of employ

ment upon the desegregation of students. Any failure of

the federal courts to effectively curb racial discrimination

in the employment policies of school boards, as and when

the children obtain racially nondiscriminatory school as

signments, is likely to be viewed by some Negro teachers

as a practical justification for them to discourage the transfer

of Negro students from all-Negro schools.

The courts can enlist all elements of the school com

munity in an effort to desegregate schools—but only by a

display of firmness, affording prompt and adequate redress

against racially discriminatory hiring practices. This case

should be remanded with direction that the School Board

be ordered to offer reemployment to each of the plaintiff

teachers.

Respectfully submitted,

S. W. T ucker

H enry L. M arsh, III

214 East Clay Street

Richmond, Virginia 23219

Attorneys for Plaintiffs

A P P E N D I X

I n T he U nited States D istrict Court

For T he Western D istrict of V irginia

ROANOKE DIVISION

Civil Action N o. 64-c-73-r

Mary A. Franklin, Lawrence H. Leftwich, Mary F. M ont

gomery, Sylvia J. Harvey, Hugh D. Woodliff, Sylvia D.

Austin, Alma G. Spivey and Virginia Teachers Association,

Incorporated,

Plaintiffs,

vs.

County School Board of Giles County

and P. E. Ahalt, Division Superintendent

of Schools of Giles County,

Defendants.

COMPLAINT

[Filed July 29, 1964]

1(a) Jurisdiction is invoked under Title 28, United States

Code, Section 1343. This is a suit in equity, authorized by

law (42 USC §1983) to be brought to redress the depriva

tion under color of any statute, ordinance, regulation, cus

tom or usage, of rights, privileges and immunities secured

by Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amendment to the Con

stitution of the United States and Title 42, United States

Code, Section 1981.

1 (b) Jurisdiction is invoked under Title 28, United States

Code, Section 1331. This action arises under the Fourteenth

Amendment to the Constitution of the United States, Section

1, and under Title 42, United States Code, Section 1983,

as hereafter more fully appears. The matter in controversy,

exclusive of interest and costs, exceeds the value of Ten

Thousand Dollars.

2. This action is a proceeding under Title 28, United

States Code, Sections 2201 and 2202 for a declaratory judg

ment that racial discrimination in the employment and as

signment of teachers in a public school system is forbidden

by the Due Process and Equal Protection Clauses of the

Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution and by Title 42,

USC §1981, for relief by injunction restraining the defend

ants from refusing to employ the individual plaintiffs for and

during the 1964-65 school session, and for relief by injunction

restraining the defendants from discriminating on a basis of

race with respect to employment of teachers in the public

school system.

3. Plaintiffs bring this action in behalf of the individual

plaintiffs and, pursuant to Rule 23(a) (3) of the Federal

Rule of Civil Procedure, as an action in behalf of persons

constituting a class so numerous as to make it impractical

to bring them all before the court; the character of the

rights sought to be enforced for the class being several, and

there being common questions of law affecting the several

rights of the individual plaintiffs and other members of the

class, and a common relief being sought.

4. The defendant County School Board of Giles County

is a body corporate discharging governmental functions,

existing pursuant to the Constitution and laws of the Com

monwealth of Virginia. Said school board is empowered

and required to establish, maintain, control and supervise

an efficient system of public free schools in said county.

Among the duties of said board is that of employing teachers

and assigning them individually to specified schools. (Con

stitution of Virginia, Article IX, Section 133; Code of V ir

ginia, 1950, as amended, Title 22.)

App. 2

App. 3

5. The defendant P. E. Ahalt is sued in his capacity as

Division Superintendent of Schools for Giles County. He

holds such office pursuant to the Constitution and laws of

the Commonwealth of Virginia as an administrative officer

of the public free school system of Virginia. (Constitution

of Virginia, Article IX, Section 133; Code of Virginia, 1950,

as amended, Title 22.) He is under the authority, super

vision and control of, and acts pursuant to the orders,

policies, customs and usage of, the defendant school board.

6. The plaintiff Virginia Teachers Association, Incor

porated, is an association chiefly composed of those mem

bers of the teaching profession residing in the State of Vir

ginia who are Negroes. Over 8000 of the estimated 8,533

Negroes teaching in public schools in Virginia are members

of the Virginia Teachers Association, Incorporated, in good

standing. Solely because of race, Negroes are excluded from

membership and participation in the Virginia Educational

Association which is composed of those members of the

teaching profession residing in the State of Virginia who are

not Negroes. The purpose of the plaintiff association is to

use all means in its power to protect the interest of edu

cation in general and to raise the standards of the teaching

profession.

7. One interest herein asserted by the plaintiff association

is the interest of those of its members who have not hereto

fore been employed by the defendant school board but now

desire or hereafter may desire employment by the defendant

school board. The experience of the plaintiff association and

its members is and has been such that it believes, and here

alleges, that a school board is unlikely to consider favorably

an application for employment from an individual who by

prosecuting litigation against the board concerning its em

ployment policies might thereby characterize himself as

undesirable. The plaintiff association asserts the interest of

App. 4

such member or members because the right not to have his

application for employment denied on racial grounds might

well be lost to the now anonymous member by his mere act

of asserting it.

8. Another interest herein asserted by the plaintiff as

sociation is the interest of the general class represented by the

individual plaintiffs, i. e., Negroes who are qualified to teach

in the public schools in Virginia. For the benefit of that

class and every person thereof, the plaintiff association here

asserts that a school board may not, for reasons of race,

discriminate against Negroes in the employment and assign

ment of public school teachers.

9. During the 1963-64 school session, each of the in

dividual plaintiffs was employed by the defendant school

board as a teacher in the Bluff City Elementary School or

the Bluff City High School which that board had set apart

and maintained for the separate education of all of the Negro

children of Giles County. The only Negroes who as teachers

were employed by the defendant school board at the close

of that session and the total number of years of such em

ployment of each were:

Mary A. Franklin............................... 30 years

Lawrence H. Leftwich 19 years

Mary F. Montgomery........................ 8 years

Sylvia J. Harvey................................... 5 years

Hugh D. Wood li IT............................... 4 years

Sylvia D. Austin................................... 3 years

Alma G. Spivey................................... 1 year

10. Following action by the Pupil Placement Board of

Virginia by which several Negro children living in Giles

County were assigned to Giles High School for the 1964-65

session, the defendant school board, on May 5, 1964, directed

that operation of Bluff City Elementary School and Bluff

City High School be discontinued after the close of the 1963-

App. 5

64 school session. By letters from the defendant Division

Superintendent of Schools dated May 15, 1964, each of the

persons named in the next preceding paragraph was

notified that his services would not be needed after the close

of the 1963-64 school session.

11. Under and by virtue of a long standing policy, prac

tice, custom and usage prevailing through the Common

wealth of Virginia (unbroken except in Arlington County

and the City of Alexandria within recent years), and par

ticularly in the County of Giles, Negroes (regardless what

the individual qualifications may be) are not and have not

been assigned to teach in public schools which white children

attend.

12. The defendants elected to dispense with the services

of all of the persons who had previously taught at the Bluff

City Elementary and High Schools solely because they are

Negroes and because the defendants have had, have, and

unless enjoined from so doing will continue to have and to

follow, the above mentioned policy, practice, custom and

usage which precludes the employment and assignment of

any Negro to teach in a public school which white children

attend.

13. The said policy, practice, custom and usage of the

defendants constitutes an arbitrary denial of the property

right of each person of the class represented by the plain

tiffs to fair and proper consideration for professional em

ployment and a denial of the right of each such person to

the equal protection of the laws, contrary to the provisions

of Section 1 of the Fourteenth Amendment and contrary

to Section 1981 of Title 42 of the United States Code.

14. The individual plaintiffs and all persons of the class

represented by the plaintiffs are suffering irreparable injury

and are threatened with irreparable injury in the future by

App. 6

reason of the policy, practice, custom and usage and the

actions of the defendants herein complained of. They have

no plain, adequate or complete remedy to redress the wrongs

and illegal acts herein complained of other than as is herein

pursued. Any other remedy to which they could be remitted

would be attended by such uncertainties and delays as would

deny substantial relief, would involve a multiplicity of suits,

and would cause further irreparable injury and damage,

vexation and inconvenience.

W herefore, plaintiffs respectfully pray:

1. That this cause be advanced on the docket and that a

hearing on the prayer for an interlocutory injunction be

held as soon as practical.

2. That the court enter a judgment, declaratory of the

rights of the individual plaintiffs and the members of the

class here represented and of the corresponding obligations

of the defendants, that the defendants may not permit con

siderations of race to affect the selection and employment or

the assignment of persons as teachers in the public school

system.

3. That the court enter an interlocutory injunction re

straining the defendants from refusing to employ the in

dividual plaintiffs, or either of them, as teachers in the public

school system of Giles County, Virginia, during the 1964-65

session.

4. That the defendants be permanently restrained and

enjoined from failing or refusing to select and hire any per

son in any position of employment under the defendants’

control, or otherwise to discriminate against any person with

respect to compensation, terms, job assignment, or con

ditions or privileges of employment, because of the person’s

race or color.

App. 7

5. That the defendants pay the costs of this action in

cluding a fee for the plaintiffs’ attorneys in such amount as

to the court may appear reasonable and proper.

6. That the plaintiffs have such other and further relief

as is just.

/ s / S. W. T ucker

Of Counsel for Plaintiffs

REQUEST FOR ADMISSIONS

Under provisions of Rule 36(a) of the Federal Rules of

Civil Procedure, plaintiffs request that, on or before the 26th

day of November, 1964, the defendants make admission of

the matters of fact hereinafter set forth :

One

That under date of May 15, 1964, the defendant Division

Superintendent of Schools sent a letter over his signature to

each of the individual plaintiffs and that the body of the

letter was as follows:

“The Giles County School Board on May 5, 1964, by

an [sic] unanimous vote, took action to close both the

Bluff City Elementary School and the Bluff City High

School at the close of the 1963-64 school session. In a

special School Board meeting on May 14, 1964, children

presently attending these schools were placed by the

School Board for the 1964-65 session.

“These two actions make it necessary to abolish your

job. Please accept this letter as your notification that

your services will not be needed after the close of this

school session. I shall be glad to discuss this problem

with you should you care for a conference.

“May I take this opportunity to thank you for the

years of service rendered the School Board of Giles

County and the children of your race.”

* * *

App. 8

Three

That the factual matter contained in paragraph 9 of the

complaint is true.

Four

That the factual matter contained in paragraph 10 of the

complaint is true.

H enry L. M arsh, III

Of Counsel for Plaintiffs

ANSWER TO REQUEST FOR ADMISSIONS

[Served November 24, 1964]

For answer to the plaintiffs’ request for admissions under

Rule 36(a) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, de

fendants state as follows:

(1) Defendants admit the letter of May 15, 1964 was

sent and that the body of the letter as set forth in the request

for admissions is correct.

* * *

(3) Defendants admit that the factual matters contained

in paragraph 9 of the complaint are true.

(4) Defendants admit that the factual matters contained

in paragraph 10 of the complaint are true.

Respectfully,

County School Board of Giles

County and P. E. A halt, Divi

sion Superintendent of Schools for

Giles County

By John H . T hornton, Jr .

Of Counsel

App. 9

EXCERPTS FROM TRIAL PROCEEDINGS OF

DECEMBER 28, 1964

* * *

[ t r . p . 6 ]

Paul E. A h a l t , called as an adverse witness by and on

behalf of plaintiffs having been duly sworn, testified as

follows:

DIRECT EXAMINATION

By: M r. Marsh

Q Would you state your name, address and occupation

please sir?

A My name is Paul Edwin Ahalt. My address is Box

493, Pearisburg, Virginia. My occupation is Division Super

intendent of School, Giles County, Pearisburg, Virginia.

* * *

[ t r . p p . 12-14]

Q Mr. Ahalt I noticed that on the forms submitted and

answers to interrogatories, I notice a listing of the various

Virginia certificates held by your teachers. Would you

explain the order of priority of these certificates and what

the various certificates signify—I mean collegiate and pro

fessional?

A If I understand your question you are asking me now

to enumerate for the Court the various kinds of certificates

issued by the State of Virginia.

Q Yes and held by the teachers in Giles County in order

of their priority?

A I would like for you to isolate those two questions

if you would please sir. When you say in the order of priority

that is where I would like to comment secondly if I may

explain further.

Q Go ahead.

App. 10

A The highest type teacher so far as paper qualifica

tion is concerned would be the post graduate professional.

This is a certificate issued for holders of masters degrees

who have had as I recall five successful years of teaching.

We have a collegiate professional certificate which is issued

to college graduates who had during their preparation for

teaching either practice teaching or over paying this de

ficiency by two years of successful teaching. Then we have

the collegiate certificate which is issued to college graduates

for those who have had the required hours and preparation

in practice teaching in specified areas. Then we have a

certificate that has not been issued since 1942 known as the

Normal Professional Certificate. This is issued originally

to persons who have had two years of college preparation

and these persons have kept their certificate active over the

years. Then there is another classification of elementary

and this is my understanding is a certificate that has been a

number of years since it has been issued. I cannot tell you the

number but those were issued originally by persons who took

a teacher’s examination and these persons will date back

forty years or more. And then there is a special certificate

and I would like to note this separate from special license.

I am frank to tell you that I don’t know what a special

certificate is. We have had as far as I know only one of

them in my period of Superintendent of Schools. The original

conditions under which that certificate was issued I could

not say. I would assume that that was one who had had

more than the one who had been issued the elementary but

not as much as the one who had been issued a normal pro

fessional certificate. That is my projection. I could not

sustain that. I have never seen that in writing. Then we

have a certificate which is known as a special license. This

is a certificate issued to persons since in the vicinity of 1955

— I would not give you that as a positive date but it is a

App. 11

certificate that has come into being during the time I have

been a superintendent of schools, issued to persons who in

1942 would not have had the equivalent of two years of

college preparation but it may be well that when the cer

tificate was issued to the person could have completed all

but the degree requirements, special license means that the

person has been certified to teach specific area subjects

by the State Board of Certification in Richmond. As I

recall that would be the full number. Now in addition to

that certain endorsements but they all come under types of

certificates which I have outlined.

* * *

[ t r . p . 26]

E v e l y n W. S h a d e , called as a witness by and on behalf

of the plaintiffs having been duly sworn, testified as follows:

DIRECT EXAMINATION

By: M r . M a r s h

Q Would you state your name and occupation please?

A Evelyn W. Shade. I am presently employed as a

secretary of the law firm of Tucker and Marsh in Richmond,

Virginia.

Q Mrs. Shade have you had any experience as a statis

tician?

A Yes I have. I have been doing statistical work in

various teacher, salary cases and equal facility school cases

and other civil rights cases since 1950, in addition to other

work in accounting and other statistical work prior to 1950.

* * *

[ t r . p . 32]

Q Did you make a compilation of the total number of

white teachers appointed to teach in Giles County in each of

the years 1960-1961 to 1964-1965?

A Yes I did.

App. 12

Q Will you explain it to us please?

A This was taken from the individual summary sheets

supplied by the superintendent of schools. In 1964-1965

there were thirteen teachers whose beginning year with the

Giles County School System was 1964-1965 and there were

four such white elementary teachers. In 1963-1964 there

were six such teachers in the high school, and none in the

elementary school. In 1962-1963 there were seven teachers

appointed to the Giles County system for the first time in

the high school and one in the elementary school. In 1961-

1962 six white teachers were appointed to the high school

and two to the elementary school and in 1960-1961 there

were two appointments to the high school and one ap

pointment to the elementary school.

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit No. 4

NEGRO TEACHERS IN GILES COUNTY, VIRGINIA, PUBLIC SCHOOLS—SCHOOL YEAR 1963-64

T o ta l

N a m e and School

T ear

A p p o in te d

C ertifi

cate

E xp eri

ence S u b je c t E ndorsem en ts S u b je c t A ssignm en ts

Mary A. Franklin

Bluff City Elementary

1923 CP 40 yrs. Elementary; Soc. Sci.,* English* Building Teacher; 5th, 6th

& 7th grades

Laurence Leftwich

Bluff City High

1949 CP 18 Elementary; English, Soc. Science Math, English, History,

Music, Guidance;

Principal

Mary F. Montgomery

Bluff City Elementary

1956 CP 8 Elementary; Gen. Sci.,* Biology* 1st & 2nd grades

Sylvia J. Harvey

Bluff City High

1959 CP 5 Soc. Sci. (not including History) Home Econ., M ath, Science,

History, Phy. Ed.

Hugh D. Woodliff

Bluff City High

1960 CP 4 Elementary 4-7; English, History,

Soc. Studies

Math, Government,

Geography, English,

Biology, Phy. Ed.

Sylvia D. Austin

Bluff City Elementary

1961 CP 3 Gen. Sci., Biology, Chemistry 3rd & 4th grades

Alma G. Spivey

Bluff City High

1963 CP 1 Business Education, Soc. Studies English, Soc. Studies,

Business Typing

*Information furnished by respective plaintiff’s. Answer to interrogatory indicated that information was not available to Superin

tendent of Schools.

CP—Collegiate Professional.

A

pp. 13

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit No. 5

WHITE ELEMENTARY TEACHERS IN GILES COUNTY, VIRGINIA, PUBLIC SCHOOLS—1964-65 SCHOOL YEAR

T otal

N a m e a n d Schoo l

Tear

A p p o in te d

C ertifi

cate

E xp eri

ence S u b je c t E ndorsem en t S u b je c t A ssignm en t

Nancy Morgan—Narrows 1964 CP 2 yrs. Art 1st Grade

Carolyn Johnston— Pearisburg 1964 SL 0 — 3rd Grade

Dorothy Harvey—King Johnston 1964 CP 0 History, English 6th Grade

Grover DeHart— Pembroke 1964 Coll. 0 Elem. 6 & 7; English, History,

Social Studies

7th Grade

Nancy Boens— Pembroke 1962 CP 2 Biology (High & Jr. High) 6th Grade

Goldie Auvil—Rich Creek 1961 CP 9 Elem. grades 1 thru 7 2nd Grade

Mildred Miller-—Pembroke 1961 CP 8 Elementary 2nd & 3rd Grades

Florence Mandeville— Glen Lyn 1960 CP 8 Elementary; English, Social Science 1st and 2nd Grades

Inez Richards— Pearisburg 1959 CP 12 Elementary; English 5th Grade

Maurice Witten—-Newport 1959 CP 7 Gr. 4 thru 7; English, Social

Studies

7th Grade

William Forrestal— Pembroke 1958 pp 11 Social Studies, History, French,

Basic Business, Distributive Educ.

Diversified Occupations

Principal; 3rd Grade

part-time

Duane Billups— Pearisburg 1957 CP 7 Social Studies, History 5th Grade

Robert Taylor—King Johnston 1957 CP 8 Health, Phy. Ed., History, Social

Studies

Principal; 7th Grade

Ronald Whitehead—Rich Creek 1957 pp 7 History, Social Studies, Basic Principal; 7th Grade

Business

A

pp. 14

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit No. 5 ( continued)

WHITE ELEMENTARY TEACHERS IN GILES COUNTY, VIRGINIA, PUBLIC SCHOOLS— 1964-65 SCHOOL YEAR

T otal

N a m e a n d School

Tear

A p p o in te d

C ertifi

cate

E xp eri

ence S u b je c t E n dorsem en t S u b je c t A ssignm en t

Irene Copen— Pearisburg 1956 CP 19 Elementary 1 st Grade

Louise Miller—Pearisburg 1956 CP 23 Elementary; English, Soc. Studies 2nd Grade

Nannie Muncy—Narrows 1956 CP 35 Elementary 3rd Grade

John H. Webb—Narrows 1956 SL 44 — 6th Grade

Mary Whitehead— Pearisburg 1955 CP 9 Social Studies 1st Grade

Shirley Ramsey— Pearisburg 1955 CP 8 Elementary; English 2nd Grade

Frances B. Coburn—Rich Creek 1954 CP 14 English, Social Studies 4th Grade

Betty Coffman—Rich Creek 1954 CP 12 Gr. 1 thru 7; English, Biology,

Social Studies

7th Grade

Alice Mustard—King Johnston 1954 CP 12 Gr. 6 & 7; Home Econ., English

History, Chemistry

7 th Grade

Pauline Williams—Narrows 1954 CP 22 Elementary; English 3rd Grade

Howard Houchins—Narrows 1953 NP 19 Elementary 6th Grade

Nona Eisel— Penvir 1953 SL 14 — 1st & 2nd Grades

Sarah Ragsdale— Penvir 1953 SL 11 — 3rd & 4th Grades

Hazel Armbrister— Pearisburg 1952 CP 9 Elementary 5 th Grade

Edith H. Lewey—King Johnston 1952 SL 8 — 7th Grade

Dan M. Huffman—Narrows 1952 PP 12 Gr. 6 & 7; Spanish, Accounting,

History, English, Social Studies

Principal

A

pp. 15

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit No. 5 (continued)

WHITE ELEMENTARY TEACHERS IN GILES COUNTY, VIRGINIA, PUBLIC SCHOOLS— 1964-65 SCHOOL YEAR

T otal

N a m e and School

Tear

A p p o in te d

C ertifi

cate

E xp eri

ence S u b jec t E n dorsem en t S u b je c t A ssignm en t

Glenn Cruise—JPearisburg

fc; C sJL..-., ,M. i *.f. i. At-..

1951 p p 13 Gr. 6 & 7; English, Social Studies,

History, Spanish

Principal

Iris Williams—Narrows 1950 CP 17 Elementary; Biology, Chemistry,

English, Home Economics

1st Grade

Lavinia Bogess—Rich Creek 1950 CP 18 Gr. 6 & 7; Physical Ed., Biology 6th Grade

Bessie Price— Rich Creek 1949 Elem. 29 Elementary 1st Grade

Gladys Johnson—Narrows 1948 NP 17 Elementary 4th Grade

Emma Steele—Newport 1948 CP 10 Elementary, English, History,

Social Studies, Art, Music

4th & 5th

M artha W. Britts—Kimballton 1948 CP 16 Gr. 1 thru 7; English, History,

Social Studies

Head teacher; 7th Grade

Alva Lucas—Newport 1946 CP 10 Elementary; English, History,

Social Studies

1st & 2nd Grades

Mary Allen—King Johnston 1946 CP 12 Elementary; English, History,

Social Studies

6th Grade

Elizabeth Graves—Narrows 1946 NP 25 Elementary 4th Grade

Hazel Lester— Pearisburg 1946 CP 26 Elementary; Geography 5 th Grade

Margaret Whittaker—Eggleston 1946 CP 18 Gr. 6 & 7; English, Social Science,

Chemistry, General Science, Art

5th & 6th Grades

Florine McCrady—Narrows 1945 CP 17 Elementary; English, History,

Social Studies

2nd Grade

A

pp. 16

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit No. 5 ( continued)

WHITE ELEMENTARY TEACHERS IN GILES COUNTY, VIRGINIA, PUBLIC SCHOOLS— 1964-65 SCHOOL YEAR

Total

N a m e a n d School

Tear

A p p o in te d

C ertifi

cate

E xp eri

ence S u b je c t E n dorsem en t S u b je c t A ssignm en t

Elizabeth Johnston— Pearisburg 1945 CP 19 Elementary, English 4th Grade

Virginia M. Ward—King Johnston 1945 CP 27 Gr. 1 thru 7; History, Social

Studies

6th Grade

Maereen Whitt— Eggleston 1945 CP 22 Elementary; English Head Teacher; 2nd & 3rd

Grades

Loma Lowe— Pearisburg 1944 CP 34 Elementary; Biology, English,

History, Social Studies

4th Grade

Virginia Martin—Kimballton 1943 SL 23 — 1st & 2nd Grades

Eleanor Snapp— Pearisburg 1943 CP 35 Elementary; English, History 2nd Grade

Lucille Meadows—Rich Creek 1943 NP 18 Elementary 5th Grade

Beulah Fox—Glen Lyn 1942 PP 12 Elementary Head Teacher; 3rd, 4th,

5th Grades

Lucy W. Miller—White Gate 1941 CP 20 Elementary; English, Latin, French,

History, Social Studies

Head Teacher; 4th, 5th,

6th Grades

Frances Montague— Penvir 1940 CP 27 Elementary; English, History,

Social Studies

Head Teacher;

5th, 6th Grades

Constance Thompson—Narrows 1940 CP 23 Elementary; English, History,

Social Studies

1st Grade

Gladys Jamison— Pembroke 1940 CP 24 Elementary; English 1st Grade

Vivian M. Akers—Bane 1939 CP 23 Elementary; English, History Head Teacher; 1st & 2nd

Grades

A

pp. 17

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit No. 5 ( continued)

WHITE ELEMENTARY TEACHERS IN GILES COUNTY, VIRGINIA, PUBLIC SCHOOLS— 1964-65 SCHOOL YEAR

Total

N a m e a n d S choo l

T ear

A p p o in te d

C ertifi

cate

E xp eri

ence S u b je c t E ndorsem en ts S u b je c t A ssignm en ts

Rosalinda F arrier—Kimball ton 1938 CP 20 Elementary; English, Geography,

History, Social Science

5th & 6th Grades

Violet Philpott— Pearisburg 1936 CP 28 Elementary; English, History,

Social Studies

2nd Grade

Myrtle Guynn—Rich Creek 1936 CP 17 Elementary; Biology, English

Social Science, History

3rd Grade

Pauline Frazier—Narrows 1935 CP 12 Elementary Grades 4 to 7 7th Grade

Anne Hendrickson— Pembroke 1935 NP 19 Elementary 2nd Grade

Mary Morrison— Pembroke 1935 NP 19 Elementary 7th Grade

Inez Miller—Newport 1934 NP 13 Elementary 2nd & 3rd Grades

Myrtle Whittaker—Eggleston 1934 NP 15 Elementary 4th & 5th Grades

Edna G. Thompson— Pearisburg 1934 CP 40 Elementary; English, History,

Social Studies

4th Grade

Virginia Houchins—Narrows 1933 NP 17 Elementary 4th Grade

Jocelle Saunders—Narrows 1933 NP 28 Elementary 6th Grade

Ella Williams—Pembroke 1931 CP 22 Gr. 1 thru 7; English 2nd Grade

Ruth J. Perdue— Eggleston 1931 CP 26 Elementary; English 6 th & 7 th Grades

Jessie B. Givens—Narrows 1930 CP 34 Elementary; English, History,

Social Studies

2nd & 3rd Grades

A

pp. 18

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit No. 5 ( continued)

WHITE ELEMENTARY TEACHERS IN GILES COUNTY, VIRGINIA, PUBLIC SCHOOLS— 1964-65 SCHOOL YEAR

Total

N a m e a n d School

Tear

A p p o in te d

C ertifi

cate

E xp eri

ence S u b je c t E ndorsem ents S u b je c t A ssignm ents

Eliza Miller—Pearisburg 1928 CP 27 Elementary; Biology, English, Soc.

Studies, History, Math

3rd Grade

Ruby Herbert—Narrows 1928 CP 39 Elementary; English, History,

Social Studies, Art

5th Grade

Clara Patteson—Narrows 1928 CP 36 Elementary; English, History 7th Grade

Olive Williams— Pearisburg 1928 NP 28 Elementary 1st Grade

Hester Beamer—Narrows 1927 NP 26 Elementary 7th Grade

Margaret Straley—Eggleston 1927 CP 33 Elementary, English, History,

Biology, Social Science

1st & 2nd Grades

Annie Munsey— Pearisburg 1926 CP 17 Elementary 3rd Grade

Mattie Guthrie— Pearisburg 1926 CP 38 Elementary; Biology, English,

Soc. Science, History

1st Grade

Emily Eaton—Bane 1925 CP 39 Grades 1 thru 7 2nd & 3rd Grades

Nancy Allen— Pembroke 1924 CP 40 Elementary, Music, English, History 1st Grade

Nancy Dobyns—White Gate 1924 CP 32 Elementary, English, French,

History, Social Studies

1st, 2nd, 3rd Grades

Nellie V. Wheeler—Narrows 1924 CP 40 Elementary; English, History,

Social Studies

5th Grade

Mary Carman— Pembroke 1923 CP 29 Elementary; English, History 5th Grade

61

'

44

v

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit No. 5 ( continued)

WHITE ELEMENTARY TEACHERS IN GILES COUNTY, VIRGINIA, PUBLIC SCHOOLS— 1964-65 SCHOOL YEAR

Total

N a m e a n d School

Tear

A p p o in te d

C ertifi

cate

E xp eri

ence S u b je c t E ndorsem ents S u b je c t A ssignm ents

Greye Lovall—Narrows 1922 CP 41 Elementary; English 2nd Grade

Margaret Caldwell—Kimballton 1921 CP 17 Elementary 3rd & 4th Grades

Anne Hale— Pembroke 1919 NP 34 Elementary 3rd Grade

Lila J. Guthrie— Pearisburg 1919 CP 45 Elementary; Biology, English

Social Studies

4th Grade

Marguerite Williamson— Pembroke 1919 CP 41 Elementary; English, History 4th Grade

Hollie P. Stowers—Bane 1918 CP 29 Grades 4 thru 7; English,

Social Studies

4th & 5th Grades

Type of Certificate: CP— Collegiate Professional NP—-Normal Professional

PP— Postgraduate Professional SL— Special License

C oll— Collegiate Elem.— Elementary

A

pp. 20

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit No. 6

T otal

WHITE HIGH SCHOOL TEACHERS OF ENGLISH AND SOCIAL SCIENCES

IN GILES COUNTY, VIRGINIA, 1964-65 SCHOOL YEAR

N a m e and School

T ear

A p p o in te d

C ertifi

cate

E xp eri

ence S u b je c t E ndorsem en ts S u b je c t A ssignm ents

Ann Shelton—Giles 1964 CP 3 yrs. English, History, Soc. Studies,

Latin

English

Larry Greer—Narrows 1964 CP 5 History, Soc. Science, Health,

Physical Educ.

Amer. History, Soc. Studies,

assistant football,

basketball, spring sports

Susan von Peachy— Giles 1964 CP 12 English English 10; Developmental

Reading

Pamela Croy— Giles 1963 CP 1 History, Social Science English 11, World History

Arvenie Shutt— Giles 1963 pp 18 Health Educ., History, Soc. Stud. U. S. History, Sociology

Jewell Francis—Giles 1962 CP 2 English, Vocational Health Educ. English 11

Grace Glenn—Giles 1962 CP 9 English, History, Social Science;

Elementary grades 1-7

English 12

Donald Brookman—Narrows 1962 CP 2 Spanish, Social Studies (not

including History)

Economics, Sociology; Soc.

Studies; World Geography

Sybil Kountz— Narrows 1961 CP 2 Art English 8, Art

Joseph Coleman— Giles 1961 pp 7 History & Soc. Science, Gen.

Science, Basic Business

World History, Government

Robert Richards—Giles 1961 PP 10 Music, English, Speech, Sociology, English, Speech

Bioiogy

A

pp. 21

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit No. 6 (continued)

T otal

WHITE HIGH SCHOOL TEACHERS OF ENGLISH AND SOCIAL SCIENCES

IN GILES COUNTY, VIRGINIA, 1964-65 SCHOOL YEAR

N a m e a n d School

Tear

A p p o in te d

C ertifi

cate

E xp eri

ence S u b je c t E ndorsem en ts S u b je c t A ssignm ents

Ruby Hylton— Giles 1959 CP 18 English, History, Soc. Science;

Elementary grades 1-7

English 9

Thomas Ballard—Narrows 1959 pp 16 Health, Phy. Educ., History,

Biology, Soc. Studies

Government 12

Nancy Taylor— Giles 1958 CP 7 English English 8, Reading

Carnell Hype—Giles 1957 CP 33 Biology, English, History, Latin,

Soc. Science; all elementary

English 9

Norene Harding— Giles 1957 CP 30 Biology, English, French, History,

Soc. Science; all elementary

English 8

Glorena Rader—Narrows 1955 CP 18 English English 9

Grace Robertson—Giles 1954 pp 11 English, French, History, Soc.

Studies

U. S. History

Claude Goodwin— Giles 1949 CP 8 English, History, Soc. Studies;

Grades 6 & 7

Government, Economics

Jewell Ballard—Narrows 1947 CP 10 English, Soc. Science (not including

History), Gen. Science

English 8 & 10; Reading

Cuba Hardwick—Narrows 1943 CP 33 Biology, English, History English 12

Katheryn Ring—Narrows 1930 CP 19 English, History, Social Studies U. S. History, English 10

A

pp. 22

Plaintiffs’ Exhibit No. 7

T o ta l

WHITE HIGH SCHOOL SCIENCE TEACHERS IN GILES COUNTY, VIRGINIA, PUBLIC SCHOOLS

1964-65 SCHOOL YEAR

N a m e a n d School

Tear

A p p o in te d

C ertifi

cate

E xp eri

ence S u b je c t E ndorsem ents S u b je c t A ssignm ents

Helen Blankenship—Narrows 1964 CP 0 yrs. Biology, Chemistry M ath, Gen. Science

Jacquelyn Cantley—Giles 1963 CP 6 Biology, Gen. Science Gen. Sci. 8 & 9

William Copley, Jr.—Narrows 1962 Coll. 2 Chemistry, M ath, Physics, Mech.

Drawing

Chemistry, Physics, Mech.

Drawing

Dorothy Johnson— Giles 1962 CP 4 Vocational Home Economics,

Biology, General Science

Gen. Science, Biology

Bobby D. Wilburn— Giles 1960 CP 4 Health, Phy. Educ., Biology Biology

Robert Price—Narrows 1960 pp 4 Biology, Health & Phy. Educ.,

Gen. Sci., Driver Education

Biology, Phy. Educ., head

football coach, assistant

spring sports

Cornelius Burgess—Narrows 1958 CP 9 History, Soc. Sci., Chemistry,

Biology, Physics, Gen. Science

Gen. Sci. 9, Biology

Panco Cantley—Giles 1954 CP 12 Social Studies, History, Biology,

Gen. Science

World Geography, Physics

Clotilde Ballard 1948 pp 40 Chemistry, Biology, Home

Economics, English

Chemistry, Biology

A

pp. 23

App. 24

STATEMENT OF POSITION OF PLAINTIFFS

[Filed June 22, 1965]

The position of the plaintiffs with respect to the relief

which the Court should grant pursuant to the factual find

ings and legal conclusions reached in its opinion filed on

June 3, 1965, is:

1. Having found that the school board failed to renew

the contracts of the individual plaintiffs for reasons for

bidden by the Fourteenth Amendment, the Court should

place these plaintiffs as nearly as possible in the position

they would have held but for the school board’s uncon

stitutional action. To do less is to fail to accord these plain

tiffs the protection which the constitution requires that

they have. From the evidence in this case, it appears that if

these plaintiffs had been white they would have been

reemployed for the 1963-64 session and, on a competitive

basis with other teachers in the system, they would have

had a chance for continued employment thereafter.

2. Inasmuch as the normal relief would be reinstate

ment, the burden should be placed on defendants to demon

strate that such relief should not now be given. Plaintiffs

are informed that the defendants have vacancies in several

of the areas in which some of them are certified and that

the defendants have been actively recruiting in an effort to

fill these vacancies.

3. One of the individual plaintiffs is available and anxious

to teach in Giles County in September 1965. Because the

Court’s opinion was handed down after the time for signing

contracts for the 1965-66 school year had passed, the other

six individual plaintiffs have already contracted to teach

elsewhere during the 1965-66 school term. The Court having

found that the seven teachers were discharged because of

App. 25

their race, equitable principles require that the one teacher

now available to work in September be reinstated forthwith

and that the remaining six now under employment with

other school divisions be given an early opportunity to accept

reemployment in the Giles County school system,

4. Being aware that Negro teachers in five counties in

the Western District of Virginia have suffered termination

of employment following the abandonment of special school

facilities for Negro children for the 1965-66 session, the

plaintiff Virginia Teachers Association urges that anything

less than reinstatement or opportunity for reinstatement in

the instant case will fail to deter other school boards from

similar unconstitutional action.

/ s / H enry L. Marsh, III

Of Counsel for Plaintiffs

OPINION

[Filed June 3, 1965]

This action was brought by seven Negro teachers and the

Virginia Teachers Association, Inc., an organization repre

senting Negro teachers throughout the state, against the

County School Board of Giles County, Virginia (herein

after referred to as the School Board) and the Division

Superintendent of Schools of Giles County, Mr. P. E. Ahalt.

The jurisdiction of this court is invoked under Sections

1331, 1343, 2201 and 2202 of Title 28 and Sections 1981

and 1983 of Title 42 of the United States Code.

The gist of the complaint is the allegation that the seven

individual plaintiffs were denied re-employment as teachers

by the defendants for the 1964-65 school session because of

their race. The defendants, while denying that they dis

criminated against these individuals, acknowledge that the

Fourteenth Amendment to the Constitution of the United

App. 26

States forbids discrimination on account of race by a public

school system with respect to the employment of teachers.

Defendants on their part moved for summary judgment

on the ground that the decision to refuse these teachers

re-employment was wholly within the discretion of the

school authorities. This motion was denied and an evi

dentiary hearing held at which the facts hereinafter stated

were developed.

Giles County lies in the mountains of Appalachia on the

Virginia-West Virginia line to the north and west of R ad

ford, Virginia. Over the last fifteen years the County has

experienced a gradual decline in population, recently con

tributed to by cut-backs in the work force of the Celanese

Corporation, its principal employer, resulting from automa

tion of the Celanese plant. The overall decline in population

was matched by a leveling off and decline in the number of

school age children.

P. E. Ahalt, the Superintendent, was appointed to his

present position in 1953. The evidence shows that through

out the decade 1953-63 Mr. Ahalt was faced with a con

siderable challenge in his efforts to upgrade and improve the

quality of education for all of Giles County’s children. A

program of consolidation of the white schools was carried

out and completed in 1962. Bond issues were fought, de

feated and later passed, with many of the citizens in the

remoter areas apparently resisting the closing of their local

schools. Also throughout this period efforts were made to

upgrade the quality of the schools which were provided for

the County’s approximately 125 Negro students. The evi

dence shows that during Superintendent Ahalt’s term Giles

for the first time provided facilities for the education of

Negro high school students beyond the tenth grade, and

that school building conditions were greatly improved. How

ever, the evidence also shows that the County’s facilities for

App.27

Negro students, the so-called Bluff City Schools, were never

sufficiently satisfactory to warrant accreditation and that the

faculty was, by the Superintendent’s own admission, below

the standard of the other schools. Because of the very small

Negro population of the County (some 400 out of a total

of 17,000), Mr. Ahalt recruited actively, but experienced

great difficulty in attracting teachers to staff the Negro

schools. He testified that his standards for accepting teachers

for these positions were somewhat lower than the standards

he used in screening new white applicants.

This dual school system with all of its difficulties was

ended when in May, 1964, the School Board voted to

abandon the Bluff City Negro schools as the result of the

application of approximately twenty of the Negro high

school students for transfer to the formerly all white high

schools. Following the Board’s decision, the individual plain

tiffs were notified by letters from the Superintendent dated

May 15, 1964 that their jobs had been abolished and that

their services would no longer be needed. It is this dismissal

which plaintiffs complain of, arguing that the decision of

the Superintendent was motivated by considerations for

bidden by the Fourteenth Amendment.

Mr. Ahalt has accepted full responsibility for the decision

to discharge these teachers. He acknowledges that the

decision was made only after ‘‘hours of meditation” and

that he “had a lot of misgivings” as to what his procedure

should be. No one can look into a man’s mind and examine

his thought processes. However, in the view which I take

of this case, such delving is unnecessary. Mr. Ahalt has

testified before me and appeared to be an excellent ad

ministrator dedicated to the best interests of the Giles

County school system. However, while I do not question his

allegiance, I am satisfied that his action deprived these

teachers of their rights under the Fourteenth Amendment.

App. 28

Although I sympathize with a school administrator who has

had this very thorny problem thrown upon him after what

appears to have been a long and bitter battle over con

solidation, my duty to assist in the transition from seg

regated to integrated schools requires that I direct him to

re-examine his decision.

This case bears a definite factual and legal relationship to

the case of Brooks, et al. v. School District of City of

Moberly, Missouri, 267 F. 2d 733 (8th C ir.), cert, denied,

361 U.S. 894 (1959), which involved the discharge of