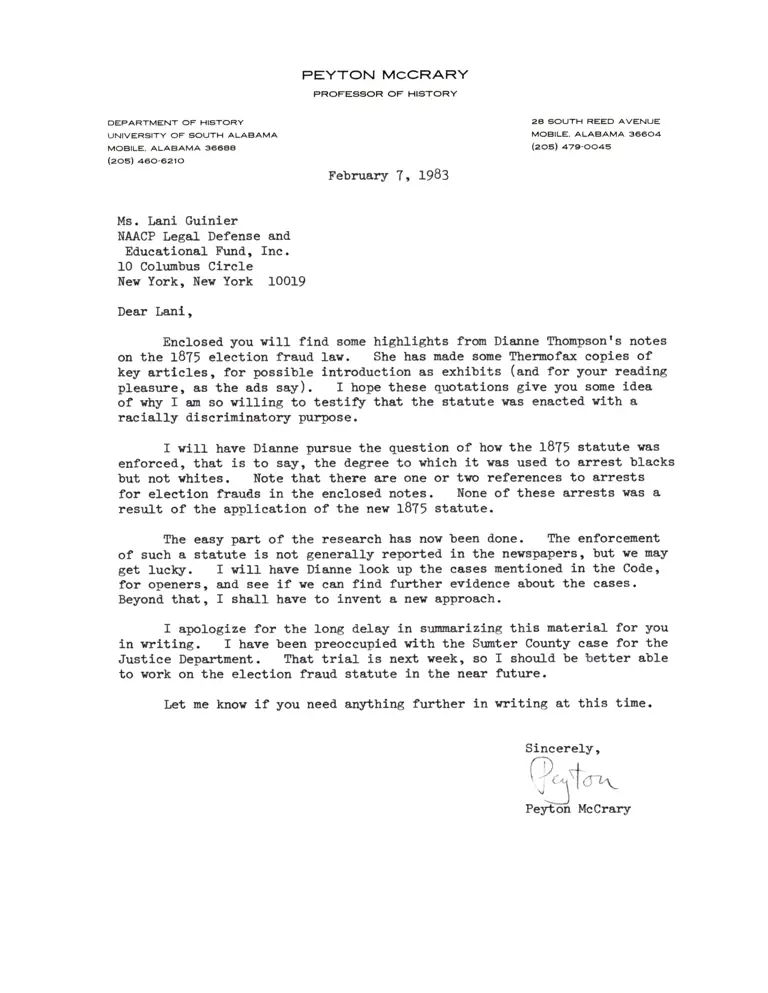

Correspondence from McCrary to Guinier

Working File

February 7, 1983

Cite this item

-

Case Files, Bozeman & Wilder Working Files. Correspondence from McCrary to Guinier, 1983. ce04f2d4-ee92-ee11-be37-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c2587853-9d3d-4812-97d5-732204a2ae2f/correspondence-from-mccrary-to-guinier. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

PEYTON MCCRARY

PROFESSOR OF HISTORY

DEPARTMENT OF HISTORY

UNIVERSITY OF S()UTH ALABAMA

MOBILE. ALABAMA 36664

(2os) 460-62ro

Febnrarly 7, L983

Ms. I€.nl Gulnler

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educatlonal Frrnd., Inc.

10 Colunbus Clrcle

I{er York, Nerr York 100}9

Dear Ianl,

Enclosed you rtlL find eome hlghLlghts from Dla.nne Ihompsonts notes

on the tB75 eteetion fraud lav. She has nade some The:mofax copies of

key artl.eles, for possibLe lntroduetlon as exhlblts (and for your readlng

pleaeure, ae the acl.s say). I hope these quotatlone glve you eome Ldea

of vtry I an so rllLing to testlf! that the statute ras enaeted rlth a

raclally d.Lger{nlnatory purpose.

I rriLl have Dlanne purgue the questLon of hon the t8?5 statute ras

enforced, that is to say, the degree to vhlch lt res used to arrest bLacks

but not vhltes. }{ote that there are oue or tvo referencea to arrests

for eleetlon fraudls in the enclosed notes. Ilone of these arregts flas a

result of the applleatlon of the nev 18?5 statute.

The eaay part of the researcb has now been d,one. Ihe enforceuent

of euch a statute ls uot generally reportetl in the nerspapers, but ve mey

get }uclry. I rl11 have Dlanne look up the eaaes nentioned Ln the Cod.e'

for openers, end see lf ve ean ftnd further evid.ence about the cases.

Beyond. that, I shall have to invent a nev approach.

I alnlogtze for the long de1ay in suma,rlzing thls materlel for you

ln rrrltlng. f have been preoceupled rrlth the Srmter County ease for the

Justlee Departnent. That trlaL ia ne:rt reek, eo I shouLd be better able

to rork on the electlon fuaud. statute ln the near firture.

Let me know lf you need anythlng further ln rrlting at thls tLne.

26 SOUTH REED AVENUE

MOEIILE. ALABAMA 36604

(zos) azs-ooas

SLncerely,

?,1o'.

peyt-# Mccrary

Sel-na Southern Argus

I{ov. 13, 18?\, p. 3. "Not less than one thousand frauduLent votes were eaat

for the Republican ticket ln DaLLas County.r'

Nov. 20, l-87h, g. 2. "On Saturtl.ay Last, Joseph H. Speeti, radleal Buper-

intend.ent of pubS-lc lnstruetion ln [fs,!ilnn, and radlcal probate Jutlge-e].ect

of Perry County, yBs arested. in Marion for a mlsdenea.nor nnder sectlon 99 of

the election larr, and as the proof ls under hls ovn hand. ancl seaL good

larryers think there ts no eseape for hln. Hla onJ-y chqnee is ln technicaL

quibbles. The penalty for tbe crlme le fine and lnprisonment.t'

fhe Alabana State Journal (RepubJ-lcan nevspaper)

Nov. ,, 18?4, p. 2. @! relnrta that a Regrbllcan eandtilate naned. Betts

has probably been defeatett ln the thtrd eongresaional ctlstrict, thanks to

lIlega1 voters (rhlte, presunabl-y) crosslng the Georgia state Ilne to vote

for hls Democratlc opponent. The Journal aLeo contends that ln Russell

Cor:nty at least Ln0oo-Republlean voffire kept fr"on the trnL1s by iILegaI

ehallengers on election day.

Nov. ?, 1B?l+, D. 2. DETOCRATIC SEI{TIIT{ERT. Frm the Opellka Obseryer.

Whites in Opeltka took posseselon of the baLlot box, nhJ.ch at the tLme vas

cronded rith I{egroes fr@ Georgla. (See tbe eonfl-lctlng account oa Nov. 5)

MoblLe Dally Reglgter

lrlarch 6, L875, p. 1. LEIrER FRoM !,toI{TcoMEnI. Rep. Jamea Greeae clted

the electLon tleutl blLL as nore evl.denee of "the proscrlptlon of Republlcana

ln the State.rt He also contended. that havlng one box for federal electlong

antl. another for state eLeetloas vaa deaLgned to confuse blaek votere.

(Greene le a black leglelator. )

Iater, dnrlng the ca,mpaign to eaIl a new eonstitltloaa]. conventLon (vhtch

eueceeded.), tUe DenocratLc and Conaerratl.ve hreeutive Comlttee of A.].ebona

lnclud.ed the foJ.l.ovlng coment ln lts Addreas to the Votere:

Jury 23'J8?5, p. 3. "You nay obJeet to havlng to note ln e beat /E1ecttonpreclnet/, bd there can be no falr electloa ln the Black Belt ytthout that,

ead. la your Betrera.l e].ecttons do you deslre to bc chcated. out of the eleetlon

of eand.Lrlates of your choiee by frautlulent voting?rr

Mobile Daily Reglster

Jan. 9, 187r, p. 2. I,DIfTEIS ELECTIOII BILL. "It is un<loubtedly the purpose

of the Alabana legislature to enaet a.n Electlon tan nhich rill prevent

hereafter the great frauds vhich have been eomLtted vlth the negro vote.

The voter ni11 hereafter be conpelLed to vote ln the preclnct ln vhtch he

reeldes, Ln ord.er that tt nay elearly be knorn that he ls a legal voter, a,nd

to prevent the tntimittation and terrorl.sn to rhieh he is subJectecl by the

carpetbaggers /eie!!/, nho holtl their League a.nd National Guard meetings at

the eoutty geats. I{e intend to break up the practlce under vhieh the

edventurers have eollected their dupes at the eor:ntry churehes, marehed thero

ln armed bod.ies to the county seato placed. tlckets in thelr ha.ntls, and . :

lnstructetl then hor to vote."

Jan. 17, 18?5, p. 1. LETTER FROM MOI{IIGOMERY. "The negroes opposed a suspension

of the ruLes in a nr:mber of caaes, in ord.er that bilIs night not go to a second

readlng. . . . Any biUs affecting the eonduct of eleetlons ln any locallty

or the agrleulturaL lnterests of the state, or punlshnent for the eomisslon

of a crime, invarLabLy meet rith obJeetions.t'

Jan. 28, 1875. ELECTION LAw. "lqr. Cobb has lntroduced ln the Senate a

general eLeetion bil1, with nany changes from the present lanr." Among the

eha^nges sumarized are the requlrement that voters cast ballots only in

the varcl where they reside, a provisl.on allorlng a^ny qualified. voter to

chal-J.enge anotherrs right to vote at the polls, the elinination of "obnoxLous

features about lntinitlation, slmulatLon of ballots, ete.rt' &nd. a provision

givlng eleetion officials free reln to stuff ballot boxes, rhlcb reads as

follovs: "The balLots are retaLnetl by the inspectors in the several rrards

or preelncts, and only the certlficates and poI1 lists &re for-rard.ed to the

hobate Jutlge, rho . shall open and eount the returns. r'

Jan. 29, L875, p. h. BY TELEGnAPH FROM I{ONTGOMERY. In the House Datus Coon

of Sel-ma introcluced. a b111 to enforce the rtght to vote in Alabana by

regulating punlshments of voters for eleetlon fraud. (fn other vords, the

Republicans elearly sav the election fraud bil-I sponsored. by the Democrats --

the one vhich passed and. und.er whleh Ms. Sosemen and Ms. Wiltler were found.

euilty -- as a parbisan statute vhich rras llkely to be enforced. in a raclalJ-y

d.iscrlmlnatory nanner. )

Feb T, 18?5, , p. L. LEITER rROM MONTGOMmY. Comittee on Prlvileges

and Eleetlons reports a nev version of the election b111, lneluding anong

other changes a nev sectlon 38: "that any pereon voting more than onee is

guilty of a felony."

Feb. 27, 1875, p. 1. LEITER FRoM MoNTGoMEBY. The d.ebate over the fraud-

ulent voting btI1 in the House ineludes "violent opposition from the Radleal

members." Among other issues, Rep. Coon arguecl that 'rthe bill would

prevent the free exereise of the balIot in that negroes woulcl be influenced.

and intinidtatetl by their enp}oyers who vote in the same precinct vith them,

whiLe this vould not be the ease if they were allowetl to go ln a body to

such points as they preferred."

l{oblle Daily Regigter

l{or. 3, 187\, p.2. 'Ye varn the freuttulently regiatered negroes that they

are narked; tbat there le a differenee betveen registering and votlug, and.

in voting illegaJ.ly they vlll go fron tbe polle to prison.r'

Nov. lr, 18?l+, p. 1. $IE EIJCTION. The Reglster reports 300 "fraudulent

votes polled by l{egroes wbo escaped belng arreatedrrr but also notee that

\0-50 Negroea vere lqlrLsoned for 'rrepeating. " Anong these rrere 2 or 3

"colored.t' U. S. Deputy Mareha1s.

ilov. 6, I8?\r p. 1. TIIE COURI'S. "A negro naned HenrT HiLllams ras

arralgned, for lllegal. voting.rr

lfov. ?, 18?\, p. 1. The eharges of lll,ega1 votlng against Eenr? l{l}Ll.o'na

rere d.ropped for laek of evid.eece.

I{ov. 1lr, L8?l+ t p. 2. oUR coilGRESsIoltAL DISTRICT. "The apparent vote for

Jere Hara].son /a black Republlean/ la this congresaional- dlstrlct lg ].:9155]-.

The vote for trh. Bromberg /vhite Republlean Frederick Bromberg of the

"Bromlerg lettcrY ls t6r953. flrls gtves Jere aa apparent naJorlty of

2,198. Ttre vote for Haralson ls evidently fuaudulent.t'

l{ov. 20, I8?[, p. 2. lfhe Reglster mentloaa a Moblle voter reglstratlon lav

tteslgaed to prevent voter fr&udThfs refers to a portlon of the statute that

al.so includ.etl the flrst unequlvoeal provlslon for at-large electione for the

Moblle eity goverrrnent ).

Nov. 29, L8?\, g. 2. Rep. Anderson ( ?) spoXe ln the House ln fanor of

the b111 regulatlng nrrnielpal electlons in Moblle. IIe sald the bllI was

lntend.etl to rld the people of MobiLe of "the notorious 6afl s.rnitted frauds

ln public electlons antt the ctlsorders, deuora-lizatlon, and other great

evils florlag from sueh fraudg. rr hrlsting lans ttltl not penallze electlou

frautl ln Mobl1e, he eontended, adctlng that state election lars ln gencral

vere ln need. of revisioa to deal rrlth thls problen.

Dec. 2, 18?L, p. 1. OtR MOilTGOMERY LEHIER. I'It is saltl that the RadlcaLs

have d.etemlaed ln caueus to vote agalnst prolonging the sesslon, whlch, lf

tme, rrtll . . . prevent the passage of a.n eLectlon 1aw and. revenue 18r."

Dec. 6, 18?\, p. 2. PBBPABE FOB ACTION. Under the nev nunlclpal eleetlon

lav for Mobile, eLeetione rere to be helcl wlthln a ferr daya, pronptlng the

Reglster to urge vhlte nen rrunder the banner of the tDeuocratlc and Coasenra-

tive organlzatLont" to be tttnre to thelr eolorsrr end vrest elty govertrment

"ftom the hantls of the Dergoes and ba1lot-box stuffers."

Dec. J.6, 1B?l+, p. \. From MontgomerlT. In reference to the Moblle elty

election (prevlously heltt), Datus Coon, a nhl.te Republlcan from Dellae County,

presented a petition from a Mobile Republlean, I'etating that I,000 eolored

RepublLeaus ln the Seventh Ward. rere ttlsfranehlsed. under the new electLon

lar.rt The eomrrnieatlon fron Mobile lncluttetl. the charge that rfthe reglstrat!.on

ras eonducted glorrly by deslgn, md that voters eouldntt regleter.tt fhe

author of the eomunlcatlon, oae Ben La.ne Posey, asked Rep. Coon to lntroduce

a blIL comecting thta eituation if Mr. Anderson (fron Mobtle) woulct not.

Montgomery Daily Attver-tiger

Nov. 1I, 18?b, p. 1. "The lst Dlstriet remaLns ln doubt. Ihe l{eg3oes

stuffect 11000 fraud.ulent votes ln an obseure box of DalLas County."

Nov. 26, 1B?l+ , p. 2. t'Russe11, a Tuskaloosa ne8ro, vho voted, in the last

electlon there 111ega11y, has been tried., eonvieted, and gentenced to the

peuitentiary for tno years."

Dec. 12, 1B?l+, p. 1. From the Florenee Jourzral. "The present leglalature

ores it to the good of the eomonvealth to enact a lar looklng to the

suppresslon of l}Iegal- votlng. A lav shouJ.d be passecl al.J.oriug no nan

to vote save l.n hls ovn preci.nct. Under the exLsting lavs, enacted ln the

iuterest of the Ratl.ica1 party, the nergoes ean easlIy follow the teachings

of Boss Speaeer 1!J. S. Sen. George Speneer, a Repub1lca41l -- rto vote early

aod vote often.r Shoulcl a lav aa ve have suggested be passed, the negroes

voultt most probably be knovn to the challengers. Such a lav, eurtalling

or abrlfuing the rights and prlvileges of none, rrouJ-tl be hlghJ.y satlsfactory

to the friends of good govertnent throughout the gtate."

Mareh 3, 18?5, p.2. Ar,ABAI'{A LEGTSLATURE. The forlowlng is a defense of

the electl.on fuaud bill by a vhlte Denoerat traned Jerrell ( f ) or Ferrell ( ? )

vho says:

"It is an establishett faet that a whlte man eannot easlly vote more

than once at one eleetlon -- they are generalLy known -- they d.o not

all look aIlke, and, ln nany eaaes, for tbe past ten years, eourtsrnot of

their orm selectlon vere only too glad to tnup up such charges."

March 5,1875, p. 3. "Governor Houston has approved the ner eleetlon lav

for the state. Good.-bye to negro repeatlng and paeklng of negroes around

the courthouse on eleetion day.tt