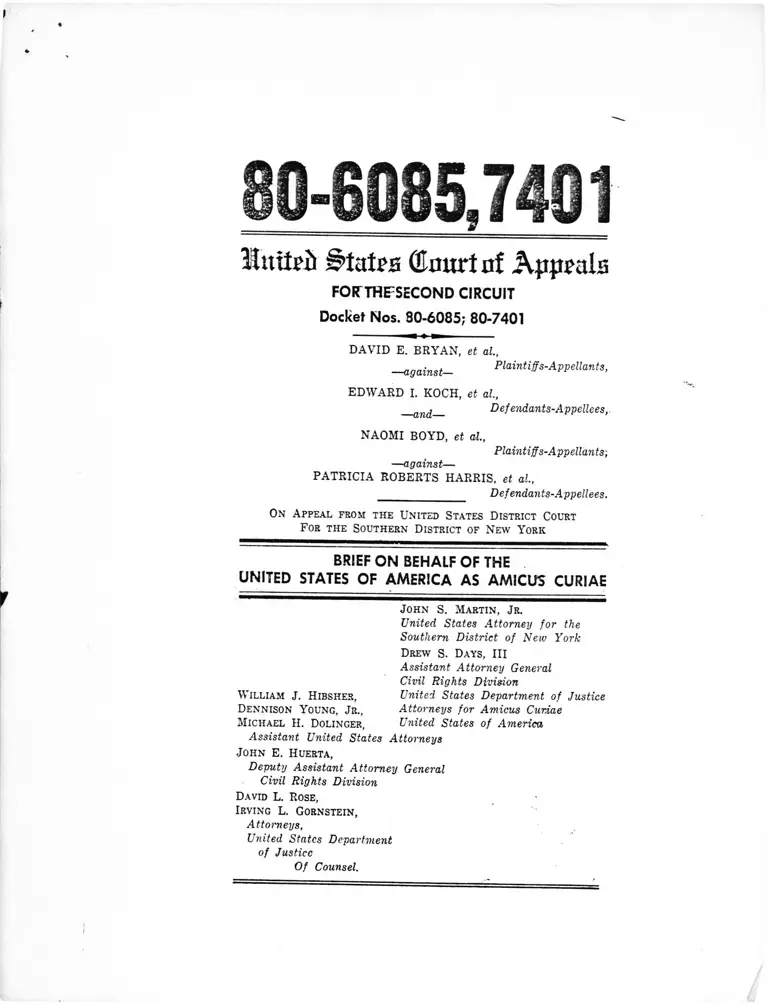

Bryan v. Koch Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

May 27, 1980

32 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Bryan v. Koch Brief Amicus Curiae, 1980. fbac4afa-b69a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c2676e5f-7d31-473e-b429-c99e17b69bda/bryan-v-koch-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

I

r

H t t i t e i ) P l a t t ’ s ( t t o u r t o f A p p e a l s

FORTTHFSECOND CIRCUIT

Docket Nos. 80-6085; 80-7401

DAVID E. BRYAN, et al,

— against— Plaintiffs-Appellants,

EDWARD I. KOCH, et al,

__an(l Defendants-Appellees,.

NAOMI BOYD, et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants;

— against—

PATRICIA ROBERTS HARRIS, et al,

________________ Defendants-Appellees.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

For the Southern District of New Y ork

BRIEF ON BEHALF OF THE

UNITED STATES OF AMERICA AS AMICUS CURIAE

John S. Martin, Jr.

United States Attorney for the

Southern District of New York

Drew S. Days, III

Assistant Attorney General

Civil Rights Division

W illiam J. Hibsher, United States Department of Justice

Dennison Young, Jr., Attorneys for Amicus Curiae

Michael H. Dolinger, United States of America

Assistant United States Attorneys

John E. Huerta,

Deputy Assistant Attorney General

Civil Rights Division

David L. Rose,

Irving L. Gornstein,

Attorneys,

United States Department

of Justice

Of Counsel

I

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Interest of Amicus Curiae ............................................ *

Issues Presented By This Appeal ................................ 2

Statement of the C a se ..................................................... 2

O

Procedural History .........................................................

The Government’s Hole B elow ........ ............................... ^

The Opinion Below .........................................................

A r g u m e n t :

P o in t I— Because The District Court Found That

The Closing Of Sydenham Would Not Cause A---------

(

Significant Adverse "Mod'll Impact On Those

Who Use Sydenham, There Is No Occasion To

Reach The Question Of What Legal Standard

Should Be Used To Establish A Prima Facie

Case Under Title VI Of 'The Civil Rights Act

Of 1964 ................................................ 8

P o in t II— Proof Of Racial Animus Is Not Required

To Establish A Prima Facie Case Under Title

VI ................................................................................ 9

A. Title VI And The Regulations Thereto Prop

erly Seek To Ensure Equal Opportunity For

Participation In Federally Funded Pro

grams ............................................. ^

B. Nothing Relied On By The District Court

Overrules The Supreme Court s Only Deci

sion And This Court’s Most Recent Decision

On Point — Upholding The Impact/Effects

Standard Under Title V I ................................

PAGE

PAGE

1. The Supreme Court Upholds The Regu

lations ........................................................... 13

2. EtYoots SWmdiml Ue.-Ghvmed U\ Vh-=

Court ........................................................... Id

3. Other Authorities Support The 10Hoots

Test ............................. 15)

C. The District Court’s Rejection of HHS’s

Regulations and Interpretation Was Based

on an Erroneous Standard of Intent and a

Misunderstanding of the HHS Interpreta

tion ...................................................................... 22

C o n clu sio n ........................................................................ 26

Cases:

T a b l e of A u t h o r it ie s

Alaska Steamship Co. v. United States, 290 U.S. 256

(1933) .......................................................................

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405 (1975

Association Against Discrimination in Employment

v. City of Bridgeport, 479 F. Supp. 101 (D.

Conn. 1979), appeal argued, Dkt. Nos. 79-7650,

79-7652 (2d Cir. April 30, 1980) .......................

21

13

20

Blackshedr Residents Organization v. Housing Au

thority of the City of Austin, 347 F. Supp. 1138

(W.D. Tex. 1971) .............................................. 20,24

Board of Education v. Califano, 584 F.2d 576 (1978),

aff’d sub nom. Board of Education of the City

of New York v. Harris, 100 S.Ct. 363 (1979) Passim

Board of Education of the City of Neiv York v.

Harms, 100 S.Ct. 363 (1979) ....................... Passim

Castaneda V. Partrida, 430 U.S. 482 (1977) ........... 23

Child v. Beame, 425 F. Supp. 194 (S.D.N.Y. 1977) 20

De La Cruz v. Tormey, 582 F.2d 45 (9th Cir. 1978),

cert, denied, 99 S.Ct. 2416 (1979) ................... . 19

PAGE

^ v . T t u Z Z f-M i^ C * * ^ * * * '* * - ;

7 3 > 7

111

Ford Motor Credit Company v. Milhollin, 48 U.S.L.W.

4145 (U.S. Feb. 20, 1980) ................................ 13> —

General Dynamics Corp. V. Benefits Revieiv Board,

565 F.2d 208 (2d Cir. 1977) ................................

Griggs v. Duke Poiver Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971) . • 13 ,y^ /

Guadalupe Organization Inc. v. Tempe Elementary

School No. 3, 587 F.2d 1022 (9th Cir. 1978) ■ ■ • 19

The Guardians Association of The City of New York,

466 F. Supp. 1273 (S .D .N J .), appea^ar^e^^ _

--------TTkt. iMo. (2d C i ^ ^ A u g . J 7 1 9 7 9 ) 16,20

Hudgens V. NLRB, 424 U.S. 507 (1976) ................... 21

Illinois Brick Co. V. Illinois, 431 U.S. 720 (1977) . . 21

Jackson v. Conway, 476 F. Supp. 896 (E.D. Mo.

1979) ................................... .............. ....................................

Johnson v. City of .Arcadia, 450 F. Supp.

Fla. 1978) ..........................................

Lau v. Nichols, 414 U.S. 563 (1974) . .

1363 (M.D.

................... 20

........ Passim

Lora v Board of Education of The City of Neiv York,

~456 F. Supp. 1211 (E.D.N.Y. 1978), appeal

argued, Dkt. No. 79-7521 (2d Cir. Mar. 17,

1980) ..........................................................................

McMahon v. Califano, 605 F.2d 49 (2d Cir. 1979) 22,23

Mourning v. Family Publications Service, Inc., 411

U.S. 367 (1973) ....................................................... u

NAACP V. The Wilmington Medical Center, Civ. No.

76-298 (D. Del. May 13, 1980) ............................

Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc. V. United

States Nuclear Regulatory Commission, 582 F.2d

166 (2d Cir. 1978) ............... ................ ................

Parent Association o f Andrew Jackson High School v.

Anibach, 598 F.2d 705 (2d Cir. 1979) ...............

iv

PAGE

Red Lion Broadcasting Co. V. F.C.C., 395 U.S. o67 ^

(1969) .......................................................................

Regents of the University of California V. Bakkc,

' 438 U.S. 263 (1978) ............................................

Resident Advisory Board .V. 99

(3d Cir. 1977 ), cert, denied, 43o U.S. 908 (1978) —

Robinson V. Vollert, 411 F. Supp. 461 (S D Tex.

1976), rerid, 602 F.2d 87 (5th Cir. 1979) • • • •

Serna v. P or tales School District, 499 F.2d 1147

10th Cir. 1974) .......................................................

Shannon v. United State, Department 0/

and Urban Development, 436 F.2d 806 (3d C . ^

1970) ...................................................................

Soria v. Oxnard School District Board of Trustees,

386 F. Supp. 539 (C.D. Cal. 1974) ................... 20

Towns v. Beame, 386 F. Supp. 470 (S.D.N.Y. 1974) 24

United States v. Bexar County, Civ. No. SA 78 CA

419 (W.D. Tex. Feb. 11, 1980) ........................... iy

Wade v. Mississippi Cooperative Extension Service,

528 F.2d 508 (5th Cir. 1976) ................................

Statutes and Regulations:

1 % H

PAGE

45 C.F.R. § 80.6 .......................................... .................... 7

45 C.F.R. § 80.8(a) ......................................................... 12

Other Authority:

HU Long. Kec. 1161 ( ) .......................................... 9

110 Cong. Rec. 1519 (196^ ............................................ 10

110 Cong. Rec. 6561 (1964) ............................................ 14

110 Cong. Rec. 6566 (1964) ............................................ 14

111 Cong. Rec. 10061 (1966) ......................................... 20

29 Fed. Reg. 16274-16305 (^ j ) ................................ 2

v

lititrii States (Emm of Apju?als

FOR THE SECOND CIRCUIT

Dockef Nos. 80-6085; 80-7401

D avid E . B r y a n , J r ., et al,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,—against—

E d w ar d I. K o c h , et al,

Defendants-Appellees,—and—

N a o m i B oyd , et al.,

Plaintiffs-Appellants,—against—

P a t r ic ia R oberts H a r r is , et al,

Defendants-Appellees.

, BRIEF ON BEHALF OF THE

JNITED STATES OF AMERICA AS AMICUS CURIAE

Interest of Amicus Curiae

Sft3tes'° f. America has a continuing re-

sponsibihty f° enforce Title VI of the Civil Rights Act

nation in statutes Prohibiting discrimi-

United S t a t e d ? by federaI &nds. The

lo u Z lT M ‘” 7 P°liCy- the U nitedStSs

and eLourag® tlt” flim in T eCeSf *7 h°Spital faeiIities

:i tTy S" faom™ ml i bT carriedout in a non-discriminatory manner.

2

Because the District Court’s ruling that a showing of

•• nal discrimination must be made in all Title VI

hmvlnn Ilrer tenS t0 imp°Se a difficuIt and unwarranted .. on Government agencies’ * enforcement of Title VI

T ? 7 l aS ° ? Pdvats plaintifFs’ eff01*ts, the United States-

, uca has an imPortant interest in this appeal We

Fe i . , ! 7 I T ' thao the United States Department of

H and Human Services is a defendant in the actions.

Issues Presented By This Appeal

in ^ th a t^ h ? 6 r1St! iCt ? ° Urt dearly erroneous in find-

S i f traditionally use Sydenham

“ d be T * as " 'el1 by other hospital facilities

without significantly increased burdei^T- - ---- ------------—

e s ta b '.i l^ 8 reaf hC8 the issue of what standard

o f i f r f a a \ l °f ' TltIe VI of tlK Civil Rights Act

racial animus? * C°“ rt err in re<iuirinS f o o f of

Statement of the Case

Procedural History

Representing minority persons who utilize health care

system" S i * ^ NOT V ' k Ci‘ y’S munioiPal hospital

( “ f i r w i f o L n i ° ™ T d two “ Hons, v.bryan ) and District Council 37 v. Koch (“D C ?7’M

atcr consolidated, seeking I , to enjoin annouiefd c lo s L i ’

sU; „ T a f r ah0SPitalS andn2’ * * * “ * « « • » S E Gfiv’M it- u huu 6 S6rvices b>r New York City (“the

} , s Health and Hospitals Corporation (“HHC’M

and Van°US City officials.*^ PSmtafi charged that S g

tions th.’1'eaiSl l eV! ^ fe:deral. agf ncies have promulgated regula-

2TTecl. keg. 'l)iz74-16,5o|PaCt/ standard under Title VI.

“ P * n t e in a

New York C ltv T p lb h o d bv .s '"™ H°SP'lal Se™ces I"

J f m released on lune 1 ? 1™ ^ * ^ , ? “ “ M ic y Task

"the Board of Directors o f’ HHr ^ P ™ } and apProved hy01 xiHC on June 28, 1979.

3

proposed closings and reductions are violative of federal

law— specifically, the Fourteenth Amendment, the Civil

Rights Acts of 1866 and 1871. Title VI of the Civil Rights

Act of 1964, and rules and regulations promulgated there

under. The United States Department of Health, Edu

cation and Welfare (“ HEW” ), now the Department of

Health and Human Services ( “HHS” ), was named as a

defendant in Binjan pursuant to Fed. R. Civ. P. 19, based

on HHS’j responsibility to enforce the requirements of

Title VI and relevant regulations. (Dkt. Entry. No. 1,*

Bmon Complaint. IT 20). No relief was sought from

HHS.**

Charging that the City and HHC were implementing

the de facto closing of Metropolitan Hospital,*** plain

tiffs in October 1979 moved for preliminary relief seek

ing to enjoin actions designed to bring about the hospi

tal’s closing. For several months, plaintiffs did not press

their motion with respect to Metropolitan, but in Febru

ary of this year, following the City’s announcement that

Sydenham Hospital was to close imminently, plaintiffs

filed a second motion seeking a preliminary injunction

against the closing of Sydenham pending the outcome of

a trial on the merits or a showing that comparable alter

native health care was available for those who depend on

Sydenham.

In late April, a separate action, Boyd v. Harris, was

filed seeking to compel the Secretary of HHS to conclude

* Because of the expedited nature of this appeal and simul

taneous briefing schedule, references to the record below will be,

where possible, to docket entries in Bryan, unless otherwise

indicated.

** Since early 1979, HHS, particularly its Office for Civil

Rights ( “ OCR” ), has been conducting an investigation into

of civil rights discrimination resulting from the pro-

>spital closings and reductions.

Metropolitan Hospital is one of four municipal hospitals,

including Sydenham Hospital, targeted for closing in the Plan.

4

HHS’s Office for Civil Rights ( “ OCR” ) investigation and

to compel the City to cease obstructing that investigation.

The Boyd plaintiffs also sought a preliminary injunction

seeking to prevent the closing of Sydenham pending the

outcome of the OCR investigation.

The United States District Court for the Southern

District of New York, per the Honorable Abraham D.

Sofaer, J., following a hearing and receipt of affidavits

on the Bryan-D.C. 37 injunction motion, and based on

affidavits filed in Boyd as well, issued its opinion on May

15, 1980 denying the injunction. Although the City had

scheduled Sydenham’s closing for that day, the District

Court declined to prevent the hospital’s closing pending

appeal, but did enjoin the closing for several days to per

mit plaintiffs to seek an injunction from this Court. On

May 19, 1980, this Court entered a stay until May 30,

1980, and scheduled argument on the appeal for that

date. On May 23, 1980, the District Court issued an

amended opinion, adding certain findings of fact and

making other changes in its opinion, but again denying

the injunction sought by plaintiffs.

The Government's Role Below

HHS filed two memoranda of law below expressing

its view that a hospital closing which has the effect of

discriminating against members of the minority commu

nity violates Title VI, whether or not the closing is under

taken with discriminatory intent. This interpretation of

Title VI is embodied in a regulation that specifically ad

dresses the location of facilities. 45 C.F.R. 80.1(b) (2).*

The supplemental memorandum suggested a specific ap

proach for determining whether a closing has the effect

of discriminating against minorities in the delivery of

services. Neither memo addressed the application of the

appropriate Title VI standard to the facts of this case.

* See discussion at 11-12, infra.

5

Thereafter, the District Court requested HHS’s views

on the merits of plaintiffs’ request for a preliminary

injunction. On May 14, 1980, HHS responded by letter

that an injunction should issue.

The Opinion Below

In a 49-page opinion issued on May 15, 1980, the

District Court denied the injunction sought by the three

sets of plaintiffs and recommended bv the Government.

(Dkt. Entry No. ------ , May 15, 19(7 ̂ Opinion.) 'l'he

District Court found persuasive the City’s evidence that

it faced a serious financial crisis, that Sydenham was the

most obsolescent of the City’s municipal hospitals, that

its cost per day of in-patient care was consistently high,

and particularly that “ Sydenham patients could be served

upon closure without significantly increased travel time”

and that the consequences of closure are “ probably less

serious than would flow from almost any other municipal

hospital closing.” (Opin. at 17, 21, 231.* While noting

that “ if Metropolitan were closed, a far more serious

problem of access for minority patients would be pre

sented,” the Court considered the issue of the possible

losing of Metropolitan Hospital not to be properly before

i^because no final decision had been made on that issue

by the City. (Opin. at 23.1 The Court’s opinion con

cluded that “ preliminary injunctive relief in the case

would still be unwarranted,” (Opin. at 47), even as

suming that plaintiffs’ (and the Government’s) position

that an impact/effects standard prevailed under Title V I :

For while the legal questions themselves are seri

ous and close, the facts are such that defendants

seem likely to succeed even if the standard of law

most favorable to plaintiffs were adopted.

* References to the Opinion will be to the Amended Opinion

issued on May 23, 1980.

6

(Opin. at 27.) The Court also found that plaintiffs had

failed to establish that Sydenham’s closing violated the

intentional discrimination standard. (Opin. at 5-26.)

Despite its holding that plaintiffs would not prevail

even under the Title VI effects standard that they urged,

the District Court nevertheless, went on to conclude that

intentional discrimination or racial animus was a re

quired element of Title VI violation. In so holding, the

Court relied on dicta (Opin. at 34), contained in two

Supreme Court cases:

[T]he opinions in two recent Supreme Court cases,

Regents of the University of California v. Bakke,

438 U.S. 265 (1978), and Board of Ed., City of

Neiv York v. Harris, [100 S.Ct. 363 (1979)1,

strongly indicate that, wei‘e the issue squarely

presented today, a majority of the Justices would

hold that Lau [^Nichols, 414 U.S. 563 (1974)]

no longer controls, and that the standard of dis

crimination in Title VI is the same standard the

Court has established for discrimination under

the Fifth and Fourteenth Amendments.

(Opin. at 30.)

'Additionally, though it recognized that “ HHS may—

and should— be recognized to possess authority to adopt

regulations that facilitate enforcement of Title VI,”

(Opin. at 39), the Court nevertheless held the HHS regu

lations issued by HHS pursuant to Title VI to “ conflict

squarely with the constitutional standard of Washington

v. Davis [426 U.S. 229 (1976 )]” :

[HHS’s regulations] dispense entirely with the

need for the agency to make a finding of racial

“discrimination” as a predicate for ultimate re

lief. True, the regulations continue to use the

word “discrimination” at various points, and could

therefore be construed to be consistent with the

7

constitutional standard. But HHS has chosen to

construe and apply its regulations otherwise, ar

guing that Title VI permits an “ effects” test, and

that this is proper because Title VI is designed

to assure the result in fact of equal access to all

federal spending programs.

(Opin. at 39.)

Finally, the District Court rejected the Boyd plain

tiffs’ claim that an injunction should issue pending the

outcome of the OCR investigation because HHS, which en

forces the regulations, e.g., 45 C.F.R. § 80.6, on which the

Boyd complaint was based, did not itself seek the relief:

The agency itself makes no such claim. HHS

has offered no evidence in this case of any viola

tion by the City of any law, and, until the eve of

this decision, carefully avoided taking any posi

tion on the merits. Still it claims no violation of

law or regulation but merely asserts the hospital

should be kept open until HHS completes its study.

Plaintiffs cannot claim that relief should be grant

ed merely because HHS commenced and has not

completed an investigation. Such an investiga

tion may be based on nothing more than commu

nity and political pressure.

(Opin. at ii, n.8.)

8

A R G U M E N T

POINT I

Because The District Court Found That Th£ Clos

ing Of Sydenham Would Not Cause A Signifi

cant Adverse Impact On Those Who Use Syden

ham, There Is No Occasion To Reach The Question

Of What Legal Standard Should Be Used To Estab

lish A Prima Facie Case Under;TitJe VI Of The Civil

Rights Act Of 1964.

The District Court accepted the City’s evidence that

“ Sydenham patients could be served upon closure without

significantly increased travel time.” (Opin. at 21-23,

iv-ix, nn. 13-22). The Court made subordinate findings

which show at what hospitals the relatively few Sydenham

patients could be served. (Opin. at 21-23.) There was

an abundance of evidence in 'the record on both sides of

this hotly contested issue.

Rule 52(a) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure

is of course designed to place primary responsibility for

factual determinations in the District Court which has

heard the witnesses and had full opportunity to weigh

the evidence. While we continue to believe that there was

evidence in the preliminary record to warrant a finding

that the closing of Sydenham Hospital would have had an

adverse impact on the minority community which Syden

ham serves, there was, however, evidence to support the

District Court’s finding in this regard. Under the strin

gent standards of Rule 52(a), we cannot and do not

contend that those findings were clearly erroneous.

The District Court found, on the preliminary

record, that there is no adverse impact on the min

ority community which Sydenham serves because the

9

patients can be seiwed at least as well elsewhere.^ Thus,

if the District Court’s findings are accepted, there was no

prima facie case of a violation of Title VI under the

adverse impact theory of liability advocated by the Gov

ernment below and in this brief. Accordingly, if those

findings are accepted, there is no occasion to reach the

important and recurring legal issue of the standard

of liability under Title VI. That issue should be reserved

for decision in a case where .the outcome turns upon

its resolution.

POINT II

Proof Of Racial Animus Is Not Required To Es

tablish A Prima Facie Case Under Title VI.

Title VI of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C.

§ 2000d, was- part of a sweeping package of remedial

measures designed to eliminate various forms of racial ^ —s

discrimination. While the Act as a whole was intended )

to deal generally with discrimination against non-w hit^ f\ _y

Title VI specifically dealt with that discrimination existing

in programs which were supported by huge expenditures

of federal funds. President Kennedy’s June 19, 1963 m e s f

” 7age to Congress proposing the legislation declared as

^follows:

Simple justice requires that public funds, to

which all taxpayers of all races contribute, not

be spent in any fashion which encourages, en

trenches, subsidizes or results in racial discrim

ination. . s

O i c O

109 Cong. Rec. 1161^ (emphasis added’)'..

10

As ultimately enacted by Congress, Title VI states:

No person in the United States shall, on the

grounds of race, color or national origin, be ex

cluded from participation in, be denied the benefits

of, or be subjected to discrimination under any

program or activity receiving Federal financial

assistance.

42 U.S.C. § 2000d.

Title VI was predicated on the principle that all per

sons are entitled to participate in the benefits of federal

programs regardless of their race. Its purpose was not

punitive, but remedial; not to punish people who harbored

an evil intent to discriminate, but to ensure that minorities

would share equally in the benefits purchased with federal

money. The Act’s remedial objective was concerned with

removing barriers which in fact impaired accomplish

ment of federal program objectives with respect to

minorities.

Federally supported health care is clearly encompassed

by the broad commandment that programs receiving fed

eral financial assistance benefit minorities and non-minori

ties equally. The specific intent of Congress with respect

to hospitals was clear:

The bill would offer assurance that hospitals fin

anced by Federal money would not deny adequate

care to Negroes.. . .

[The bill] would, in short, assure the existing

right to equal treatment in the enjoyment of

Federal funds.-

110 Cong. Rec. 1519 (1964) (remarks of Congressman

Celler, floor manager of the bill in the House of Repre

sentatives), quoted in Regents of the University of Cali

fornia v. Bakke, 438 U.S. 265, 285-86 (1978) (Powell, J .).

11

A Title VI And The Regulations Thereto Pr°P®r /

Seek To Ensure Equal Opportunity For Partici

pation In Federally Funded Programs

Title VI authorizes federal agencies to implement the

enactment via promulgation of regulations:

Each Federal department and agency which is

empowered to extend Federal financial assistance

to anv program or activity, by way of grant, loan

or contract other than a contract o ' t r a n c e or

guaranty, is authorized and directed to effectuate

the provisions of section 2000d of this title with

respect to such program or activity by issumg

rules, regulations or orders of general applicab

which shall be consistent with achievement of th

objectives of the statute authorizing the financial

assistance in connection with which the action is

taken. /,

42 U.S.C. § 2000d-l.

Empowered by Congress ‘ out

C w ’oressMntent that federally assisted programs be mi

t r e d in a way which is Jfect of

regulations prohibit all actions , * j those

subjecting minorities to unequal tr^ ™en - Supreme

' regulations have been expressly^ upheld by the ^

Court Lau v. Nichols, 414 U.S. 563 I19 4 >, as w

a number of other courts including

Board of Education v. Cahfano, 584 F. ,

7 c « m n o” ). a ffi sub non. on other yromds;Boa.d o

Education of the City of Note York V. Hams, 100 S. Ct.

363 11979) (“ Hams” ).

The regulations promulgated by HEW pieclude not

only those actions that intentionally discriminate but

those actions that have the eref discrirninating^against

protected classes-the impact/effects standard. Puipose

12

ful discriminatory design is not the standard of the in-

quiry: , ̂ »

(2) A recipient, in determining t e ypes

« * z ^ z T ^ o i : p r i -

m S T which have the effect of

dividuals to discrimination because of .

color or national origin, or have the e“ '

defeating or substantially impairing a-complis

origin.

45 C.F.R. I 80.3(b). Nor may

funds discriminate against minorities m select g

for federally supported facilities:

(3) In determining the site or locations of a

7 r T ^ ^ t l \ U s of, or- subjecting

them to discrimination under o£

which this regulation applies, on _^ g? oge

fte accomplishment of the objectives of the Act

or this regulation. -1

45 C.F.R. § 80.3(b) (emphasis added).*

“ be noted .ha, under the

•f Title VI, HHS has Uv0 ^ admlnistra,ive

S T " t S U ‘ all federal ^ " e ‘ "S e

1 2 o ^ l S » r ^ b e ,aw. .

§ 80.8(a),.

13

B. Nothing Relied On By The District Court Over

rules The Supreme Court's Only Decision And

This Court's Most Recent Decision On Point—

Upholding The Impact/EfFects Standard Under

Title VI

Though the District Court noted that dicta critical of

the impact/effects test in various of the six opinions in

Bakke is “ inconclusive” on the issue (Opin. at 31), and

that Harris expressly declined to rule on the issue which

was not squarely before the Court (Opin. at 33), the

District Court, nevertheless— based on its assessment of

the various Justices’ positions in dicta contained in the

two opinions— concluded that proof of intentional dis

crimination is now required in all cases under Title VI.

In so doing, the District Court apparently deemed the

only Supreme Court case on point to be overruled.

1. The Supreme Court Upholds The Regulations

The Supreme Court has typically afforded great defer

ence to regulations promulgated by the federal agencies

responsible for implementing a broad enactment such as

Title VI. Ford Motor Credit Company v. Milhollin, 48

U.S.L.W. 4145, 4148 (U.S. Feb. 20, 1980); Red Lion

Broadcasting Co. v. F.C.C., 395 U.S. 367, 375 (19691.

See Albefmarle Paper Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405, 431

(1975); Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424, 433-34

(1971).

In Lau v. Nichols, supra, the Supreme Court expressly

upheld HHS’s Title VI regulations, establishing that the

standard of liability under that enactment is impact or

effects, not intent:

Discrimination is barred which has that effect

even though no purposeful design is present: a

recipient “ may not . . . utilize criteria or methods

of administration which have the effect of subject-

14

ing individuals to discrimination ’ or have the

effect of defeating or substantially impairing ac

complishment of the objectives of the program as

respect to individuals of a particular race, color, or

national origin.” Id., § 80.3(b) (2 ).

414 U.S. at 568 (emphasis added).

Lau found that Congress had enacted Title VI based

at least in part on the Government’s spending power au

thority and described this authority as the “ power to fix

terms on which its money allotments to the states shall

be disbursed.” Id. at 569.* In upholding the impact/

effects standard, the Court stated: “ [Wjhatever may be

the limits of that power . . . they have not been reached

here.” Id.**

* The lengthy legislative history of the Civil Rights Act of

1964 is replete with evidence of Congressional intent that the

enactment have a far-reaching impact in prohibiting discrimina

tion. The broad goal of the Act was underscored by Senator

Kuchel who presented the Act to the Senate:

The taxes which support these programs are collected from

all citizens regardless of their race. It is simple justice

that all citizens should derive equal benefits from these

programs without regard to the color of their skin.

110 Cong. Rec. 6561 (1964) (emphasis added).

The House Republican membership also subscribed to the

Act’s broad-reaching goals:

Title VI, in effect, provides that the taxes paid to the

Federal Government by all Americans shall be used to

assist all Americans on an equal basis.

Memorandum prepared by the Republican . membership of the

House Committee on the Judiciary. 110 Cong. Rec. 6566 (1964)

(emphasis added).

** Lau held that the failure of the San Francisco Unified

School District to provide bilingual instruction to 1,800 students

of Chinese ancestry who did not speak English violated the Civil

Rights Act and HEW’s implementing regulations. Even though

insufficient evidence of discriminatory intent or purpose was

adduced, the Court decided that the denial of bilingual services

was discriminatory in effect and therefore violated Section

80.3 (b )(2 ) of HEW’s regulations.

15

To be sure, dicta in Bakke is critical of the effects

standard, but Bakke did not overrule Law. The decision

in Bakke focused on the constitutional acceptability of a

race-specific remedy. The Court held that the remedy

under review— the University’s admissions policy which

excluded Allan Bakke— amounted to impermissible dis

crimination. The Court did not, however, consider the

issue presented in, and therefore did not reverse, its

earlier decision in Lau— which held that for purposes of

establishing liability] under Title VI, as opposed to estab

lishing a remedy under the Constitution or Title VI, as

in Bakke— HHS’s regulations were legally valid and bind

ing. While the six opinions in Bakke cArt^inrnntTT-n^ itvutfvH

them enough dicta to support a host of contradictory

arguments about the scope of the Equal Protection Clause

or various civil rights statutes, the liabil^iy .standard or

standard of proof requirements necessary to establish a

Title VI prima facie violation was simply not under

review in that case.

Bakke was a case confronting the legality of a reci[

ient’s adoption of preferential racial classifications,

which classifications admittedly— albeit on behalf of

minorities— discriminated. Thus, Bakke did not reach

the issue of whether the effects test was applicable because

the University’s intent to discriminate was never in dis

pute.* Lau, on the other hand, was a case confronting

* While the four Justices comprising the so-called Brennan

group in Bakke have been read to criticize adoption of the im

pact effects test, 438 U.S. at .350-53, which was nowhere at issue

in Bakke, the four Justices comprising the Stevens group indi

cated the continued vitality of HEW's regulations and the impact/

effects test:

As with other provisions of the Civil Rights Act, Congress’

expression of its policy to end racial discrimination may

independently proscribe conduct that the Constitution does

not.

Id. at 417 (footnote omitted).

16

allegations of denial of equal services, which are the

allegations posed by the instant action, and did determine

the standard of liability in such cases. *£________________

2. Effects Standard Reaffirmed by This Court

Subsequent to Baklce, this Court reaffirmed the vitality

of the impact/effects test of Title VI and HHS’s regula

tions :

It is significant that Title VI findings of dis

crimination may be predicated on disparate impact

without proof of unlawful intent.

Califano, supra, 584 F.2d at 589.**

this Court specifically cited to Lau among other cases.

inclusion was recently reached in The Guardians

Civil Serv. Comm’n, 466 F\Su^£i>î 273! ia86

(S.D.N .Y.), appeal argued, Dkt. No. TZ-J- (2d Cir. Aug.

Justice Powell’s pronouncement that “Title VI must be

held to proscribe only those racial classifications that would

violate the Equal Protection Clause,” Bakke, supra, 98

S.Ct. 2747, also does not indicate a view contrary to Lau.

The question in Bakke was whether Title VI prohibited all

racial classifications per se or whether it, like the 14th

Amendment, prohibited only those racial classifications for

which there is no compelling justification. Justice Powell

concluded that the two provisions were alike in respect to

their prohibiting only unjustified racial classifications. This

interpretation, however, says nothing about whether Title

VI was designed to reach practices which, although not

involving explicit racial classifications, have the effect of

disproportionately harming minorities and have no justifi

cation in necessity. Concluding that Title VI is like Title

VII in prohibiting these practices (and not like the 14th

Amendment) is not at all inconsistent with the holding in

Bakke.

®* In seeking to distinguish Calif ano, the District Court relies

on the observation that the disparities in Califano were “ substan

tial” and “significant,” (Opin. at xiii-xiv, n.35), failing, in our

view, to confront Califano’s clear holding in favor of the effects

standard.

1979)

17

Like the Stevens group in Bakke, see note at 15, supra,

this Court emphasized in Califano that in the exercise of

its spending power, Congress was free to attach condi

tions to the receipt of federal funds which go beyond

constitutional requirements:

[I] n the exercise of its spending power, Congress

may be more protective of given minorities than

the Equal Protection Clause itself requires, al

though the point at which non-minorities or their

members are themselves unconstitutionally preju

diced remains in doubt even after Bakke.

Id. at 588, n.38 (emphasis added).*

The Supreme Court, in affirming this Court’s Califano

decision in Hands, found that Emergency School Aid Act

( “ ESAA” ) funds in question were governed by ESAA’s

effects test. The Court, therefore, declined to reach the

Title VI issue:

* Parent Association of Andrew Jackson High School v. Am-

bach, 598 F.2d 705 (2d Cir. 1979), does not conflict with Califano,

or with the rule that the impact/effects test is the applicable

standard under Title VI. In Andrew Jackson, this Court required

a showing of intentional discrimination in a pupil assignment/

segregation case in order to impose a court-ordered desegregation

remedy. The application of the intent standard in Andrew Jack-

son—dictated by the Supreme Court’s frequent admonition that

federal courts limit their remedial holdings to de jure segregation

in pupil assignment cases, 598 F.2d at 715-717—was expressly

analogized to Title IV, 42 U.S.C. § 2000c-6, and its constitu

tional standard. This Court concluded as follows:

[T]he limitations of Title IV control in a Title VI case in

the context of de facto segregation claims,

598. F.2d at 716.

18

Thus there is no need here for the Court to be

concerned with the issue whether Title VI of the

Civil Rights Act incorporates the constitutional

standard.

100 S.Ct. at 374.

Although the Hamis Court commented that “ Congress

might impose a stricter standard under ESAA than under

Title VI,” id. (emphasis added), that statement does not

support the conclusion that the impact/effects test is no

longer the standard. Moreover, the Court did not dis

approve or even mention Lau. The Court did state that

because a Title VI violation may result in a cutoff of all

federal funds by the enforcing agency “ it is likely that

Congress would wish this drastic result only when the

discrimination is intentional.” ld.*f Title VI, contrary

to the Harris Court’s implicit assumption, however, re

quires that fund termination by an agency “be limited

in its effects to the particular program, or part thereof,

in which such noncompliance has been so found . . . .”

42 U.S.C. § 2000d-l (1). The issue of fund termination,

it must be emphasized, was not before the Court in

Hams. Moreover, the Harris Court seemed to assume

that fund termination is the only remedy; in fact-, how

ever, Title VI provides for agency enforcement by “ other

means authorized by law,” including court suits for in

junctive relief. See 42 U.S.C. § 2000d-l (2).

In sum, the standard of liability under Title VI was

simply not before the Court in Harris. Thus, Lau and

f Moreover, when it left open the possibility that an intent

standard under Title VI may be applicable, 100 S.Ct. at 374, n.13,

the Court was referring to school segregation cases, and de jure

segregation at that, citing to Robinson v. Vollert, 411 F. Supp.

461 (S.D. Tex. 1976), which, although not noted by the Supreme

Court, was reversed on other grounds, 602 F.2d 87 (5th Cir.

19791 ; additionally, the Court expressed no certainty that even in

that context the intent standard was the one to be used.

19

this Court’s decision in Califano and their standard of

dic-ci innnatory effects under Title VI are still controlling.

3. Other Authorities Support the Effects Test

No case that we have foun^other than in a school /N

segregation setting, has imposed the intent standard in ^

a. Title VI case. At least two Court of Appeals cases

since Bakke, in addition to Califano in this Circuit, have

applied the impact/effects test in Title VI contexts’; both

cited Lau with approval. While Guadalupe Organization

Inc. v. Tempe Elementary School No. 3, 587 F.2d 1022

Ui.h Cir. 1978), a pest-Bakke decision, concluded that

Mexican-American school children were not entitled un

der Title VI to bilingual-bicultural education, the Ninth

Ciicuit nevertheless relied on Lau for the continued va-

lidity of HEW’s regulations as to the impact/effects

standard of prima facie liability. 587 F.2d at 1029 and

n.6.

Another post-Bakke decision, De La Cruz v. Tormey

582 F.2d 45, 61 and n.16 (9th Cir. 1978), cert, denied,

99 S. Ct. 2416 (1979), also relied on Lau and analogized

from the Supreme Court’s analysis of prima facie liability

under Title VI to the Title IX issue under review. The

Court reversed a dismissal of a charge that lack of cam

pus child-care facilities discriminated against women.

The general rule in other Title VI cases has also been

and continues to be that the impact/effects standard ap

plies.* E.g., Wade v. Mississippi Cooperative Extension

i.™ recent cases relied on by the District Court below in

which injunctions were denied plaintiffs contesting hospital place

ment decisions expressly declined to rule on the effects v. intent

issue because they found, (as did the District Court below), that

v 'i 'w v ? lad,MUed t0 meet their burdens under either standard.

< n n i lr \\ 'Vl,min(Jton Medical Center, Civ. No. 76-298

D- Del. May 13, 1980) Slip Op. at 53; United States V. Bexar

County, Civ. bo. SA 78 CA419 (W.D. Tex. Feb. 11, 1980).

20

Service, 528 F.2d 508, 516-17 (5th Cir. 1976) ; Serna v.

Portales School District, 499 F.2d 1147, 1154 (10th Cir.

1974); Shannon v. United States Department of Hous

ing and Urban Development, 436 F.2d 809, 816-17

(3rd Cir. 1970) ; Jackson v. Conway, 476 F. Supp. 896,

903 (E.D. Mo. 1979) ; Jolmson v. City of Arcadia, 450 F.

Supp. 1363, 1379 (M.D. Fla. 1978) ; Child v. Bcame, 425

F. Supp. 194, 199 (S.D.N.Y. 1977) ; Soria v. Oxnard

School District Board of Trustees, 386 F. Supp. 539, 544-

45 (C.D. Cal. 1974); Blackshear Residents Organization

v. Housing Authority of City of Austin, 347 F. Supp. 1138,

1146 (W.D. Tex. 1971).

Additionally, the Title VI issue posed by the instant case

is presented in three ether cases which are^before this

Court; W j f *dio# in all, the District Courts’ post-Bakke de

cisions upheld the effects standard. The Guardians Asso

ciation of The City of Neiv York v. Civil Service Com

mission of The City of New York, 466 F. Supp. 1273

(S.D.N.Y.), appeal argued, Dkt. No. 79— (2d Cir."

Aug. 1979) ; Association Against Discrimination in

Employment v. City of Bridgeport, 479 F. Supp. 101

(D. Conn. 1979), appeal argued, Dkt. Nos. 79-7650, 79-

7652, (2d Cir. April 30, 1980); Lora v. Board of Educa

tion of the City of New York, 456 F. Supp. 1211, 1277

(E.D.N.Y. 1978), appeal argued, Dkt. No. 79-7521, (2d

Cir. Mar. 17, 1980).

Finally, though the District Court below discredits

the significance of the fact that Congress has never

sought to “prevent enforcement of these [HHS’s] regu

lations, even though HHS’s disparate impact standard

was specifically upheld in Lau,” (Opin. at 37-38)—-in

deed, Congress specifically rejected an effort to amend

Title VI so as to require intent, 111 Cong. Rec. 10061

(1966)— Congress’ inaction since Lau, is illustrative of

the fact that Congress’ purpose in enacting Title VI was

to eliminate significant disparities, regardless of intent

to do so, in the use of federal funds by Title VI recipi

ents.

S vk y d e e

21

Given the existence of a Supreme Court case uphold

ing the effects standard of HHS’s regulations, the most

recent pronouncement of this Court on point similaily

upholding the effects standard, other courts’ similar hold

ings over the years, and Congress’ inaction in_ the face

of°such holdings, it was wrong for the District Court

to reach a contrary conclusion. This principle of stare

decisis was articulated by the Supreme Court as follows.

Our institutional duty is to follow until changed

the law as it now is, not as some Members of the

Court might wish it to be.

Hudgens V. NLRB, 424 U.S. 507, 518 (1976). That rale

has even greater validity where the issue is Congressional

intent and Congress has had ample opportunity to pass

on courts’ pronouncements:

[Considerations of stare decisis weigh heavily in

_________ flip area of statutory construction, where Congress

, c is free to change Court’s interpretation of its

-^W lS legislation.

Illinois Brick Co. V. Illinois, 431 U.S. 720, 736 (1977).

The fact, moreover, as this Court observed, that Con

gress has continued to appropriate funds consistent with

courts’ interpretations of enactments in even further sup

port for leaving those interpretations undisturbed:,

“ Courts are slow to disturb the settled admin

istrative construction of a statute, long and con

sistently adhered to . ■ . That consti uction muct

be accepted and applied by the courts when . • . it

has received Congressional approval, ̂implicit in

the annual appropriations over a period of . . .

[many] years.”

Natural Resources Defense Council, Inc. v. United States

Nuclear Regulatory Commission, 582 F.2d 166 (2d Cir.

1978), quoting Alaska Steamship Co. V. United States,

22

290 U.S. 256, 262 (1933). Sec also General Dynamics

Corv. v. Benefits Review Board, 565 F.2d 208, 212 (2d

Cir.* 1977).

In summary, the District Court’s conclusion that the

intentional standard of the Fourteenth Amendment now

applies to all Title VI cases is without support in the hold

ings of the cases which control these actions as well as in

other cases to have ruled on the issue and is inconsistent

with Congressional action and intent.

C. The District Court's Rejection of HHS's Regula

tions and Interpretation Was Based on a n / p ^

Erroneous Standard of Intenirttfnd a Misunder-

standing of the HHS Interpretation

Because HHS’s interpertation for this case * fails to

incorporate the “ constitutional standard of discrimina

tion,” which the District Court concluded is necessary

(Opin. at 36), the District Court rejected “ the_ estab

lished principle that courts must accord great weight or

deference to agency interpretations of legislation.” (Opin.

" a T V ) See Ford Motor Credit Company v. Milhollin, 48

U AL.W . 4145, 4148 (U.S. Feb. 20, 1980) (“ Unless

“ demonstrably irratio/al, Federal Reserve Board Staff

opinions should be dispositive for several reasons ) ;

Mourning v. Family Publications Service, Inc., 411 U.S.

387, 369 (1973) (“ The validity of a regulation will be

sustained as long as it is reasonably related to the pur

pose of the enabling legislation” ) and McMahon v. Cali-

fano, 605 F.2d 49 (2d Cir. 1979), in which this Court

3 K

r

" W

* HHS’ interpretation for this case was based on models

used by courts to apply other civil rights statutes. E.g., Griggs v.

Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971) (Title VII) and Resident

Advisory Bd. V. Rizzo, - 564 F.2d 126, 148 (3d Cir., 1977), cert,

denied, 435 U.S. 908 (1978) (Title V III).

*25

recently rejected an attack on HEW’s interpretation of

Section 202 (d i (6) of the Social Security Act, 42 U.S.C.

§ 402(d) (6), reiterating the principle of court deference

to agency interpretation of statutes:

It also is a well established principle of statutory

construction that “ [t] he interpretation of a statute

by an agency charged with its enforcement is a

substantial factor to be considered in construing

the statute.” Youakim v. Miller, 425 U.S. 231, 235-

36 (19761. Accord, Johnson V. Robinson, 415 U.S.

361, 367-68 (1974); Udall V. Tollman, 380 U.S.

1, 16 (1965) ; Friedman V. Berger, 547 F.2d 724,

731-32 (2d Cir. 1976), cert, denied, 430 U.S. 984

(1977). As long as the agency’s interpretation is

reasonable and there are no “ compelling indica

tions that it is wrong,” the agency’s construction

should be given great deference. Beal v. Doe, 432

U.S. 438, 447 (1977) ; Neiv York State Department

of Social Services v. Dublino, 413 U.S. 405, 421

(1973); Columbia Broadcasting System, Inc. v.

Democratic National Committee, 412 U.S. 94, 121

(1973) ; Red Lion Broadcasting Co. v. FCC, 395

U.S. 367, 381 (1969).

605 F.2d at 53.

Under the HHS interpretation of its regulations, a.

plaintiff, in order to establish a prima facie Title/^fcaseT

must show that a hospital closing has a disproportion

ately * adverse impact on minorities. To satisfy this

* In the context of finding that plaintiffs’ proffer of a statis

tically disparate effect in this case was not adequate evidence of

racial animus, the District Court seemed to reject any but the

so-called bi-nominal standard deviation approach to the assess

ment of disparity in data in civil rights cases. (Opin. at 7-13).

Where a series of independent decisions is under review, courts

have used the approach discussed by the District Court, e.g., Cas

taneda V. Partrida, 430 U.S. 482, 496-07 n.17 (1977) ; not all

[Footnote continued on following page]

24

burden, a plaintiff must show both that the group affected

by the closing will not receive comparajfble services at

other facilities and that the group affected is, to a signi

ficant degree, disproportionately minority. HHS’s inter

pretation requires a careful analysis of the question of

adversity:

HEW’s interpretation is that patients displaced

by the closings and reductions and unable to find

comparable services are adversely affected. In

making a determination of adverse effect, an

assessment of the evidence to determine whether

substitute services exist, whether they will be

available and accessible to those displaced, and

whether they will be comparable should be made.

A comparison of the present health care services

now being provided by the facilities slated for

closure with the services that will be provided at

the facilities designated by the City as able to

absorb the displaced patients should also be made.

All relevant attributes of health care services

should be considered to see whether, even assuming

the availability of the substitute services targeted,

there will be any reduction in the services provided

or any hardship, inconvenience, or additional

expense to displaced patients. For example, con

sideration should be given to any available evidence

on transportation time, convenience, and cost;

availability of bilingual services; availability of

cases present such data, however. For instance, if the issue under

review was the minority composition of a projected Title VI

supported housing project, c.g., Shannon V. United States/Deg’t

“o f Hous-ing^na^Urbun Dev., 436 F.2d 809 (3d Cir. 1970), where

only a single decision was under review, (as here), other ap

proaches to the assessment of disparity might be appropriate.

See also Blaclcshear Residents Org. V. Housing Auth., 347 F.

Supp. 1138, (W.D. Texas, 1972/); Towns V. Beanie, 386 F. Supp.

470 (S.D.N.Y. 1974),

T5

services designed to serve patients with special

needs; and potential barriers to admission, e.g.,

pre-admission deposit requirements; private ph”

sician admission requirements; and whether Medi

id, Medicare, and medically indigent patients a

unable to gain admission to voluntary hospitals.

(Dkt. Entry No. 94, Gov. Supplemental Memo, at 6).

Contrary to the District Court’s understanding (Opin.

at 44), HHS’s interpretation would not shift the burden

of proof based solely on a showing that proportionately

more minorities use Sydenham than use the municipal

hospitals in the City as a whole. The interpretation re

quires a plaintiff to show, in addition, that users of a

hospital scheduled for closing would be unable to obtain

-hos pi tal- oohochriod -4?or olooing w ould bo uim blir~tu' ub*

comparable services at other comparably accessible

facilities.

—^ W e submit that the District Court’s criticism of the

T i t l e y ' regulations and HHS’s interpretation for this

case was in error. The view of the United States is that

the Title VI effects regulations have continued vitality

and that Government civil rights agencies including the

OCR investigators who continue their review of the

City’s hospital closings and cutbacks plan— may continue

to seek to ascertain significant adverse disparities without

the need to justify their inquiries on the ground that they

ultimately point to purposeful discrimination.

26

CONCLUSION

This Court need not reach the issue of what

standard of proof is necessary to show a violation

of Title VI; but if the Court does reach that issue,

the United States of Arn^sica urges the Court to

rule that a disparate adverse impact is sufficient to

establish a prima facie violation of Title VL

Dated: New York, New York

May 27, 1980

Respectfully submitted,

J o h n S. M a r t in , J r .

United States Attorney for the

Southern District of New York

D r e w S. D a y s , III

Assistant Attorney General

Civil Rights Division

„United States Department

of Justice

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae

United States of America.

W il l ia m J. H ib s h e r ,

D e n n is o n Y o u n g , J r ., .

M ic h a e l H . D o l in g e r ,

Assistant United States Attorneys

J o h n E . H u e r t a ,

mi* Deputy Assistant Attorney General

« ay Civil Rights Division

D avid L . R ose ,

I r v in g L . G o r n s t e in ,

< Attorneys, JJnited States Department

of Justice