Rojo v Kliger Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

November 15, 1989

56 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Rojo v Kliger Brief Amicus Curiae, 1989. 4c91f336-c39a-ee11-be37-00224827e97b. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c2928384-36c3-4233-9370-c84d4dfa1dee/rojo-v-kliger-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

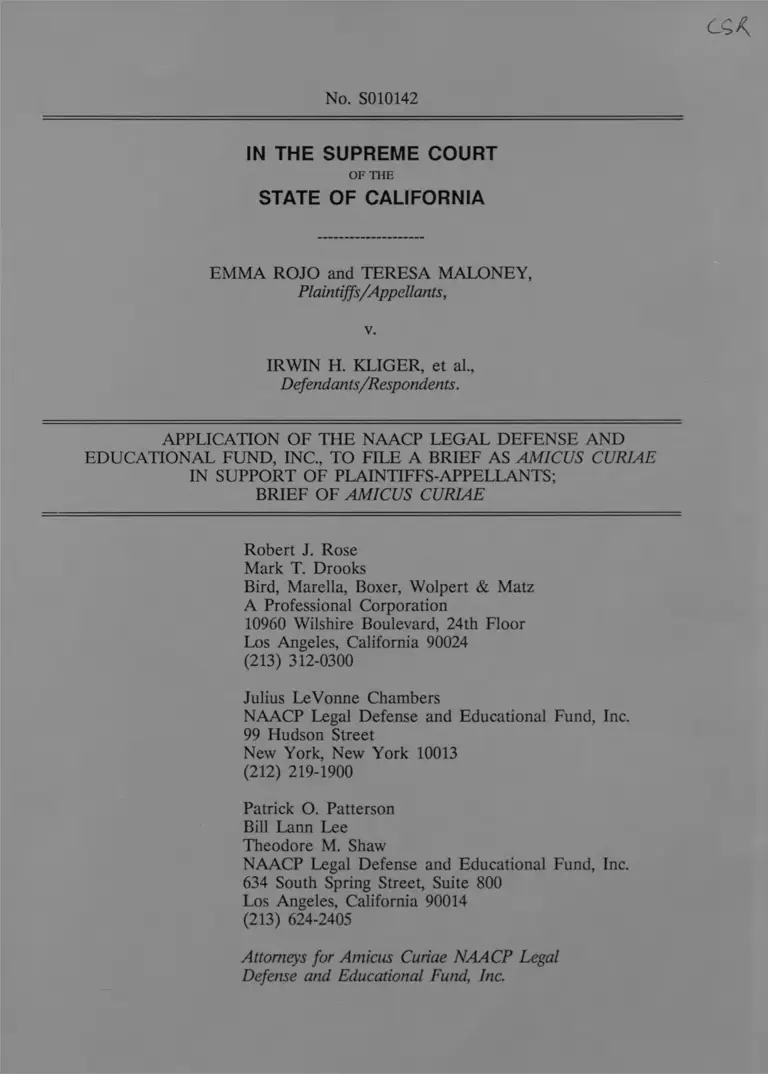

No. S010142

IN THE SUPREME COURT

OF THE

STATE OF CALIFORNIA

EMMA ROJO and TERESA MALONEY,

Plaintiffs/'Appellants,

v.

IRWIN H. KLIGER, et al.,

Defendants/Respondents.

APPLICATION OF THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC., TO FILE A BRIEF AS AM ICUS CURIAE

IN SUPPORT OF PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS;

BRIEF OF AMICUS CURIAE

Robert J. Rose

Mark T. Drooks

Bird, Marella, Boxer, Wolpert & Matz

A Professional Corporation

10960 Wilshire Boulevard, 24th Floor

Los Angeles, California 90024

(213) 312-0300

Julius LeVonne Chambers

NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

Patrick O. Patterson

Bill Lann Lee

Theodore M. Shaw

NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.

634 South Spring Street, Suite 800

Los Angeles, California 90014

(213) 624-2405

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae NAACP Legal

Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.

No. S010142

IN THE SUPREME COURT

OF THE

STATE OF CALIFORNIA

EMMA ROJO and TERESA MALONEY,

Plaintiffs/Appellants,

v.

IRWIN H. KLIGER, et al„

Defendants/Respondents.

APPLICATION OF THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC, TO FILE A BRIEF AS AM ICUS CURIAE

IN SUPPORT OF PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS;

BRIEF OF AM ICUS CURIAE

Robert J. Rose

Mark T. Drooks

Bird, Marella, Boxer, Wolpert & Matz

A Professional Corporation

10960 Wilshire Boulevard, 24th Floor

Los Angeles, California 90024

(213) 312-0300

Julius LeVonne Chambers

NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

Patrick O. Patterson

Bill Lann Lee

Theodore M. Shaw

NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.

634 South Spring Street, Suite 800

Los Angeles, California 90014

(213) 624-2405

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae NAACP Legal

Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.

TO THE HONORABLE MALCOLM M. LUCAS, CHIEF JUSTICE, AND TO THE

HONORABLE ASSOCIATE JUSTICES OF THE SUPREME COURT OF THE

STATE OF CALIFORNIA:

Pursuant to Rule 14(b) of the California Rules of Court, the NAACP Legal

Defense and Educational Fund, Inc. ("Legal Defense Fund"), respectfully requests

permission to file a brief as amicus curiae in support of the Appellants. This application

is based on the following grounds.

1. The Legal Defense Fund is a national civil rights legal organization that has

litigated many cases throughout the United States on behalf of black persons seeking to

vindicate their civil rights. The Legal Defense Fund's western regional office, located in

Los Angeles, currently represents individuals and organizations in a number of lawsuits

and administrative proceedings challenging racial discrimination in employment and

housing under federal and California law. The Legal Defense Fund believes that its

experience in such litigation and the research it has performed will assist the Court in

the present case.

2. The Legal Defense Fund has undertaken an extensive analysis of legislative

history, and has supplied a compilation of legislative materials in the accompanying

Appendix of Legislative Materials, attached to the concurrently lodged Request for

Judicial Notice. The points to be argued in the Legal Defense Fund's amicus curiae brief

are as follows:

(a) Based upon the history of one of the predecessor acts to the Fair

Employment and Housing Act, it is clear that the Legislature understood

there to be independent statutory and common law rights of action in

addition to administrative remedies, and that aggrieved persons could select

- 1 -

their remedy -- either judicial or administrative — without any requirement

of exhaustion.

(b) The history of the parallel development of California Government

Code section 12993(c) from both the Fair Employment Practices Act and

the Rumford Housing Act demonstrates that section 12993(c), without

question, has always been understood by the Legislature and the

administrative enforcement agency to be directed solely to preemption of

local laws. It was never intended to displace or limit the common law

rights or remedies of individuals.

(c) Appellants also allege two claims under the Unruh Civil Rights Act,

Civil Code sections 51 and 51.7, in their proposed First Amended

Complaint. The history of the enactment of section 51.7 in 1976 shows that

the Legislature strongly desired to provide for a separate, independent and

concurrent administrative and judicial remedy to fight violence based upon

race and other enumerated bases, free of any requirement to elect

remedies.

(d) Contrary to the position taken by Respondents and Amicus Curiae

California Employment Law Council, the caselaw is in fact consistent with

this legislative history.

(e) For the foregoing reasons, Appellants should be allowed to pursue

their claims in the proposed First Amended Complaint.

3. Counsel for the applicant are familiar with the questions involved in the

present case and the scope of their presentation, and believe there is a necessity for

additional argument on the points specified.

- 2 -

4. A brief amicus curiae which sets forth the interest of the Legal Defense

Fund and which addresses the foregoing points accompanies this application. Counsel

has also lodged a second volume containing a Request for Judicial Notice by Amicus

Curiae NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc., Memorandum of Points and

Authorities; Declaration of Robert J. Rose; and Appendix of Legislative Materials. That

volume contains the legislative materials relied upon by the Legal Defense Fund in its

brief.

W HEREFORE, the Legal Defense Fund respectfully requests leave to file both

its brief amicus curiae, and its Request for Judicial Notice; Memorandum of Points and

Authorities; Declaration of Robert J. Rose; and Appendix of Legislative Materials.

Dated: November 15, 1989 Respectfully submitted,

Robert J. Rose

Mark T. Drooks

BIRD, MARELLA, BOXER,

WOLPERT & MATZ

A Professional Corporation

Patrick O. Patterson

Bill Lann Lee

Theodore M. Shaw

NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

Attorneys for Amicus Cunae NAACP Legal

Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.

- 3 -

No. S010142

IN THE SUPREME COURT

OF THE

STATE OF CALIFORNIA

EMMA ROJO and TERESA MALONEY,

Plaintiffs/Appellants,

v.

IRWIN H. KLIGER, et al„

Defendants/Respondents.

BRIEF OF AM ICUS CURIAE

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC.

IN SUPPORT OF APPELLANTS

Robert J. Rose

Mark T. Drooks

Bird, Marella, Boxer, Wolpert & Matz

A Professional Corporation

10960 Wilshire Boulevard, 24th Floor

Los Angeles, California 90024

(213) 312-0300

Julius LeVonne Chambers

NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.

99 Hudson Street

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

Patrick O. Patterson

Bill Lann Lee

Theodore M. Shaw

NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.

634 South Spring Street, Suite 800

Los Angeles, California 90014

(213) 624-2405

Attorneys for Amicus Curiae NAACP Legal

Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION ...................................................................................................... 1

STATEMENT OF INTEREST ............................................................................... 3

STATEMENT OF THE C A S E ............................................................................... 4

QUESTIONS P R E S E N T E D ..................................................................................... 5

STATUTES IN V O L V E D .......................................................................................... 6

ARGUMENT .............................................................................................................. 7

I. THE STATUTORY LANGUAGE AND LEGISLATIVE

HISTORY OF THE FEHA CLEARLY SHOW THAT THE

LEGISLATURE DID NOT INTEND TO DISPLACE OTHER

STATUTORY AND COMMON LAW R E M E D IE S ............................ 7

A. The New York Law Against D iscrim ination ............................... 8

B. Passage of the California F E P A ...................................................... 12

II. THE LANGUAGE AND LEGISLATIVE HISTORY OF

CURRENT CALIFORNIA GOVERNMENT CODE SECTION

12993(c) DEMONSTRATE THAT IT WAS INTENDED

ONLY AS A PROCEDURAL DEVICE TO PREEMPT

LOCAL AND COUNTY O R D IN A N C ES................................................ 14

A. The 1959 Preemption Provision in F E P A ..................................... 14

B. The 1963 Hawkins Fair Housing L a w .......................................... 16

C. The 1978 Clean-Up Amendments to FEPA ............................... 20

D. The Final Merger of Section 1432 and

Section 35743 ....................................................................................... 23

III. THE RALPH CIVIL RIGHTS ACT OF 1976 CREATED

A SEPARATE, INDEPENDENT AND CONCURRENT

REMEDY TO FIGHT VIOLENCE BASED UPON

D ISC R IM IN A TIO N .......................................... 23

l

IV. CASELAW IS CONSISTENT WITH THE STATUTORY

LANGUAGE AND LEGISLATIVE HISTORY; COMMON

LAW REMEDIES HAVE NOT BEEN DISPLACED, NOR

MUST THEY BE DEFERRED PENDING EXHAUSTION OF

ADMINISTRATIVE R E M E D IE S .............................................................. 27

A. Preexisting Remedies Were Not Displaced

By The F E H A ..................................................................................... 27

B. Cases Suggesting The FEHA Preempted

Preexisting Common Law Remedies Are Based

On A Misreading Of California Government

Code Section 12993(c)....................................................................... 30

C. CELC's Reliance On Age Discrimination Cases

Is Misplaced ....................................................................................... 32

D. Respondents' Reliance On General Cases

Involving Exhaustion Of Internal Remedies

Is Misplaced ....................................................................................... 34

V. C O N C L U S IO N ................................................................................................ 37

- ii -

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases: Page:

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody (1975)

422 U.S. 405, 95 S.Ct. 2362 ................................................................................................ 3

Alcorn v. Anbro Engineering, Inc. (1970)

2 Cal.3d 493, 86 Cal.Rptr. 88 ............................................................................ 28, 29, 30

Ambrose v. Natomas Co. (1984)

155 Cal.App.3d 397, 202 Cal.Rptr. 2 1 7 ......................................................................... 32

American Tobacco Co. v. Superior Court (1989)

208 Cal.App.3d 480, 255 Cal.Rptr. 280 17

Baker v. Kaiser Aluminum &

Chemical Corp. (N.D.Cal. 1984)

608 F.Supp. 1 3 1 5 ................................................................................................................. 33

Brown v. Board o f Education (1954)

347 U.S. 483, 74 S.Ct. 686 ................................................................................................ 3

California Manufacturers Association v. Public Utilities

Commission (1979)

24 Cal.3d 836, 157 Cal.Rptr. 676 ..................................................................................... 8

Carsner v. Freight liner Corp. (1984)

69 Or.App. 666, 688 P.2d 398 .......................................................................................... 30

Casteneda v. Holcomb (1981)

114 Cal.App.3d 939, 170 Cal.Rptr. 875 ......................................................................... 21

City o f Susanville v. Lee C. Hess Co. (1955)

45 Cal.2d 684, 290 P.2d 520 ............................................................................................. 35

Coca-Cola Co. v. State Board o f Equalization (1945)

25 Cal.2d 918, 156 P.2d 1 ................................................................................................ 21

Commodore Home Systems v. Superior Court (1982)

32 Cal.3d 211, 185 Cal.Rptr. 270 ......................................................................... 7, 8, 28

Diamond View Ltd. v. Herz (1986)

180 Cal.App.3d 612, 619, 225 Cal.Rptr. 6 5 1 ................................................................. 17

Ficalora v. Lockheed Corp. (1987)

193 Cal.App.3d 489, 238 Cal.Rptr. 360 . . .

- iii -

31

Flores v. Los Angeles Turf Club (1961)

55 Cal.2d 736, 13 Cal.Rptr. 201 ....................................................................... 27, 35, 36

Friends o f M ammoth v. Board o f Supervisors (1972)

8 Cal.3d 247, 104 Cal.Rptr. 761 ..................................................................................... 8

Froyd v. Cook (E.D.Cal. 1988)

681 F.Supp. 669 ........................................................................................................... 31, 32

Griggs v. Duke Power Co. (1971)

401 U.S. 424, 91 S.Ct. 849 ................................................................................................ 3

G ulf Oil Corp. v. Bernard (1981)

452 U.S. 89, 101 S.Ct. 2193 ............................................................................................. 3

Harlan v. Sohio Petroleum Co. (N.D.Cal. 1988)

677 F.Supp. 1 0 2 1 ................................................................................................................ 32

Helmick v. Cincinnati Word Processing, Inc. (Aug. 23, 1989)

___Ohio S t.3 d ____, ___N.E.2d

50 F.E.B. Cases 1554 ........................................................................................................ 30

Hudson v. Moore Business Forms, Inc. (N.D.Cal. 1985)

609 F.Supp. 467 ................................................................................................................... 33

Mahoney v. Crocker National Bank (N.D.Cal. 1983)

571 F.Supp. 287 ................................................................................................................... 32

McKee v. Bell-Carter Olive Co. (1986)

186 Cal.App.3d 1230, 231 Cal.Rptr. 304 .............................................................. 35, 36

NAACP v. Button (1963)

371 U.S. 415, 83 S.Ct. 328 ................................................................................................ 3

National Muffler Dealers Association v.

United States (1979)

440 U.S. 472, 99 S.Ct. 1304 ............................................................................................. 21

Newman v. District o f Columbia (D.C. App. 1986)

518 A.2d 698 ...................................................................................................................... 30

People v. Fair (1967)

254 Cal.App.2d 890, 62 Cal.Rptr. 632 ......................................................................... 7

Page:

- iv -

Page:

People v. Tanner (1979)

24 Cal.3d 514, 156 Cal.Rptr. 450 ..................................................................................... 17

Pfeifer v. United States Shoe Corp. (C.D.Cal. 1987)

676 F.Supp. 969 ................................................................................................................... 32

Real v. Continental Group, Inc. (N.D.Cal. 1986)

627 F.Supp. 434 .................................................................................................................... 32

Robinson v. Hewlett-Packard Corp. (1986)

183 Cal.App.3d 1108, 228 Cal.Rptr. 591 ......................................................... 29, 30, 31

Rojo v. KLiger (1989)

209 Cal.App.3d 10, 257 Cal.Rptr. 158 ......................................................................... 5

Salgado v. Atlantic Richfield Co. (9th Cir. 1987)

823 F.2d 1322 ...................................................................................................................... 32

Sorosky v. Borroughs Corp. (C.D.Cal. 1985)

119 L.R.R.M. (BNA) 2785 affd in part,

rev'd in part (9th Cir. 1987) 794 F.2d 794 ................................................................. 32

Strauss v. A.L . Randall Co. (1983)

144 Cal.App.3d 514, 194 Cal.Rptr. 520 ................................................................. 32, 33

Takahashi v. Board o f Education (1988)

202 Cal.App.3d 1464, 249 Cal.Rptr. 578 .............................................................. 29, 31

Van Arsdale v. Hollinger (1968)

68 Cal.2d 245, 66 Cal.Rptr. 2 0 ....................................................................................... 10

Wagner v. Sanders Associate, Inc. (C.D.Cal. 1986)

638 F.Supp. 742 ................................................................................................................... 32

Webster v. State Board o f Control (1987)

197 Cal.App.3d 29, 242 Cal.Rptr. 685 ......................................................................... 10

Westlake Community Hospital v. Superior Court (1976)

17 Cal.3d 465, 131 Cal.Rptr. 90 .................................................................................... 36

Wilson v. Vlasic Foods, Inc. (C.D.Cal. 1984)

116 L.R.R.M. (BNA) 2 4 1 9 ............................................................................................... 32

Yurick v. Superior Court (1989)

209 Cal.App.3d 1116, 257 Cal.Rptr. 665 ...................................................................... 29

- v -

Statutes;

Cal. Civ. Code § 5 1 ............................

Cal. Civ. Code § 5 1 .7 ..........................

Cal. Civ. Code § 5 2 ............................

Code of Civ. Pro. § 1859 .................

Cal. Gov. Code § 12921 ....................

Cal. Gov. Code § 12930(f)(2)...........

Cal. Gov. Code § 12940(i) ..............

Cal. Gov. Code § 12948 ....................

Cal. Gov. Code § 12993(a) .................

Cal. Gov. Code § 12993(c) .................

Cal. Health & Safety Code § 35731

[repealed 1977] ..................................

Cal. Health & Safety Code § 35743

[repealed 1977] ..................................

Cal. Lab. Code § 1412

[repealed 1980] ..................................

Cal. Lab. Code § 1419(f)(2)

[repealed 1980] ..................................

Cal. Lab. Code § 1420.8

[repealed 1980] ..................................

Cal. Lab. Code § 1422.2

[repealed 1980] ..................................

Cal. Lab. Code § 1431

[renumbered § 1432 (1967)]

[repealed 1980] ...............................

New York Law Against Discrimination,

N.Y. Sess. Laws 1945, Ch. 118 § 1,

N.Y. Exec. Laws §§ 290-301 ...........

.................................. 2, 4, 16, 27

............................ 2, 3, 23, 24, 27

............................... 19, 23, 24, 26

................................................... 7

..................................................... 11

........................................ 24, 26

................................................... 4

................................................ 26

....................... 6, 7, 10, 13, 32

1, 2, 6, 7, 14, 15, 18, 23, 30, 31

................................................ 17

....................... 18, 20, 21, 22, 23

..................................................... 11

.................................................. 24

................................................ 26

.................................................. 17

13, 15, 16, 18, 20, 21, 22, 23

Page:

8, 10, 11, 12

v i

Legislative M aterials: Page:

Assembly Bill Nos. 41, 42, 50, 1732, and

1775 (1943 Reg. Sess.) ........................................................................................................ 9

Assembly Bill No. 3 (1945 Reg. S e s s .) .................................................................................. 9

Assembly Bill No. 3027 (1949 Reg. S ess .) ......................................................................... 12

Assembly Bill No. 2251 (1951 Reg. S ess .) ......................................................................... 12

Assembly Bill No. 91 (1951 Reg. Sess.) ............................................................................ 15

Assembly Bill No. 900 (1953 Reg. Sess.) ......................................................................... 12

Assembly Bill No. 971 (1955 Reg. Sess.) ......................................................................... 12

Assembly Bill No. 7 (1957 Reg. S e s s .) ............................................................................... 12

Assembly Bill No. 801 (1961 Reg. Sess.) ......................................................................... 16

Assembly Bill No. 1240 (1963 Reg. S ess .) ........................................................... 17, 18, 19

Assembly Bill No. 1915 (1977 Reg. S ess .) ....................................................................20, 22

Assembly Bill No. 2986 (1976 Reg. S ess .)....................................................................24, 25

The Friends Committee on Legislation,

The Story o f the 1963 California

Legislature (1 9 6 3 ) .................................................................................................. 17, 18, 19

Report o f the New York State Temporary

Commission Against Discrimination (1 9 4 5 ) .............................................................. 9, 11, 12

Statement of Governor Edmund G. Brown on

Human Rights (1 9 6 3 ) ........................................................................................................ 16

Fair Employment Practices Commission,

Section-By-Section Analysis o f A B 1 9 1 5 ......................................................................... 21

13 Fair Employment Newletter (1 9 6 3 ) ......................................................................... 19, 20

11 Fair Employment Newsletter (1963) ............................................................................ 20

14 Fair Employment Newsletter (1963) ............................................................................ 20

- vii -

Page:

Letter from William H. Hastie, Jr.,

to Julian Dixon, dated May 9, 1978 ............................................................................... 22

Ways & Means Staff Analysis of AB 2986 (1976) ................................................... 24-25

Comments of Assembly Office of Research

on AB 2986 (1976) ........................................................................................................... 25

Governor's Office of Legal Affairs,

Enrolled Bill Report on AB 2986 (1976) .................................................................... 24

Law Reviews and Articles:

Spitz, The New York Law Against Discrimination

(1948) 20 N.Y. State Bar Assoc. Bull. 8 ....................................................................... 8

Oppenheimer & Baumgartner, Employment Discrimination

and Wrongful Discharge: Does the California Fair

Employment and Housing A ct Displace Common Law

Remedies? (1989) 23 U. San Francisco L. Rev. 1 4 5 ................................................... 34

Note, Fair Employment Practices - A Comparison o f State

Legislation and Proposed Bills (1949) 24 N.Y.U. Law

Quarterly Rev. 398 .............................................................................................................. 9

Note, State Fair Employment Practices Acts (1961)

36 Notre Dame Lawyer 1 8 9 .......................................................................................... 9, 15

Comment, The New York State Commission Against

Discrimination: A New Technique for an

Old Problem (1947) 56 Yale L.J. 837 ............................................................................ 8

Tobriner, California FEPC (1965)

16 Hastings L.J. 333 ................................................................................................ 9, 12, 20

vm

INTRODUCTION

Upon this point a page o f history

is worth a volume o f logic.

Oliver Wendell Holmes

New York Trust Co. v. Eisner

(1921) 256 U.S. 345, 349

The NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc.1 (referred to as "Legal

Defense Fund") has sought leave to file this brief in support of Respondents Emma Rojo

and Teresa Maloney because there are significant events in the history of the Fair

Employment and Housing Act (the "Act" or "FEHA") that the parties and other amicus

curiae have not brought to the Court's attention. This legislative history establishes that

Appellants should be permitted to proceed with their independent statutory and common

law claims.

The Respondents Brief and the Brief of Amicus Curiae California Employment

Law Council In Support of Respondents ("CELC Brief'), without resort to actual

legislative materials, both rely upon legislative intent which they "infer" from the words

of the Act. They claim that the Legislature intended Government Code section 12993(c)

to displace all other common law rights of a victim of discrimination, and to require

exhaustion of administrative claims ~ even those sought to be waived - to bar access to

independent, simultaneous judicial remedies. (CELC Brief, at pp. 8, 21-22.)

There is no need to resort to inference to divine the intent of the Legislature.

The language of the FEHA demonstrates that no preemption nor exhaustion requirement

1. The NAACP Legal Defense & Educational Fund, Inc., is not part of the National

Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), although the Legal

Defense Fund was founded by the NAACP and shares its commitment to equal rights.

The Legal Defense Fund has had for over 30 years a separate board, program, staff,

office and budget.

- 1 -

was intended. Moreover, the legislative history of this Act is rich. In this Brief, we first

trace the development of a predecessor to the FEHA, the Fair Employment Practices

Act ("FEPA"), to show that its legislative history is flatly inconsistent with the claims of

Respondents and the CELC. In fact, the Legislature understood there to be independent

statutory and common law rights of action in addition to the remedies provided by

FEPA, and intended that aggrieved persons could select their remedy -- either judicial

or administrative — without any requirement of exhaustion.

We next trace the parallel development of California Government Code section

12993(c) from both the FEPA and the Rumford Housing Act, to demonstrate that section

12993(c), without question, has always been understood by the Legislature and the

administrative enforcement agency to be directed solely to preemption of local laws.

It was never intended to displace or limit the common law rights or remedies of

individuals, as Respondents and CELC now assert.

Appellants also allege two claims under the Unruh Civil Rights Act, Civil Code

sections 51 and 51.7, in their First Amended Complaint. We demonstrate that in

enacting section 51.7 in 1976 the Legislature strongly desired to provide for a separate,

independent and concurrent administrative and judicial remedy to fight violence based

upon race and other enumerated bases, free of any requirement to elect remedies.

Again, Respondents and CELC are either unaware of this, or have chosen to ignore it.

Finally, we review the caselaw relied upon by the Respondents and CELC to

show that it is in fact consistent with this legislative history.

The history of the FEHA unequivocally demonstrates the Legislature's intent in

these acts to create a sword against discrimination. It is indeed ironic that this Court

is now asked to turn that sword into a shield for employers who have allegedly

- 2 -

committed violence and other civil wrongs against individuals, who just happen to be

their employees.

STATEMENT OF INTEREST

The Legal Defense Fund is a national civil rights legal organization that has

litigated many cases throughout the United States on behalf of black persons seeking to

vindicate their civil rights. A nonprofit corporation established in 1940 under the laws

of the State of New York, the Legal Defense Fund was founded to assist black persons

in securing their constitutional and statutory rights through the legal system. Under its

charter, the Fund provides free legal assistance to individuals and groups suffering

injustice by reason of racial discrimination.

For nearly five decades, Legal Defense Fund attorneys have engaged in litigation

in federal and state courts involving a wide range of race discrimination issues, including

employment and housing discrimination. (See, e.g., Brown v. BcL o f Education (1954) 347

U.S. 483, 74 S.Ct. 686; Griggs v. Duke Power Co. (1971) 401 U.S. 424, 91 S.Ct. 849;

Albemarle Paper Co. v. Moody (1975) 422 U.S. 405, 95 S.Ct. 2362.) The United States

Supreme Court has recognized the Legal Defense Fund as having "a corporate reputation

for expertness in presenting and arguing the difficult questions of law that frequently

arise in civil rights litigation." (NAACP v. Button (1963) 371 U.S. 415, 533, 83 S.Ct. 328.

See also G ulf Oil Corp. v. Bernard (1981) 452 U.S. 89, 99, fn. 11, 101 S.Ct. 2193 [the

Legal Defense Fund is "a nonprofit organization dedicated to the vindication of the legal

rights of blacks and other citizens"].)

The Legal Defense Fund's western regional office, located in Los Angeles,

currently represents individuals and organizations in a number of lawsuits and

- 3 -

administrative proceedings challenging racial discrimination in employment and housing

under federal and California law. The Legal Defense Fund believes that its experience

in such litigation and the research it has performed will assist the Court in the present

case.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

The original complaint in this action asserted only two causes of action. First, the

complaint alleged a violation of the plaintiffs' civil rights under California Government

Code section 12940(i), the civil remedies provision of the FEHA. Second, the complaint

alleged intentional infliction of emotional distress. Defendants moved for summary

judgment.

On the day the summary judgment motion was to be heard, plaintiffs moved to

amend their complaint. Although the proposed First Amended Complaint for Damages

retained a claim for intentional infliction of emotional distress, it did not contain a cause

of action under the FEHA. The amended complaint also asserted causes of action for:

violation of California Civil Code sections 51 and 51.7; assault and battery; wrongful

discharge and constructive wrongful discharge; breach of contract; breach of the implied

covenant of good faith and fair dealing; negligent infliction of emotional distress; false

imprisonment; and other causes of action. The Superior Court, apparently unaware of

the pending motion to amend the complaint, granted summary judgment based upon the

original complaint.

The Court of Appeal recognized that evidence submitted in connection with the

motion for summary judgment was sufficient to raise factual issues in connection with the

common law causes of action asserted in the proposed First Amended Complaint for

- 4 -

Damages. The Court of Appeal also recognized that "[ujnless an original complaint

shows on its face that it is incapable of amendment, denial of leave to amend constitutes

an abuse of discretion, irrespective of whether leave to amend is requested." (Rojo v.

Kliger (1989) 209 Cal.App.3d 10, fn. 4, 257 Cal.Rptr. 158.) The court next determined

that the common law causes of action asserted in the amended complaint were not

barred either by preemption or by a failure to exhaust administrative remedies. Finally,

the court concluded that a common law cause of action existed for wrongful termination

in violation of the public policy against sex discrimination.

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

The Appellants now seek to litigate only upon the proposed First Amended

Complaint, which states no cause of action under the FEHA. The only issues presented

on this appeal, therefore, relate to the adequacy of the proposed First Amended

Complaint. They are:

(1) Does the FEHA preempt remedies under either the

Unruh Civil Rights Act or common law for wrongful conduct

that also constitutes employment discrimination?

(2) Does the FEHA require that its administrative remedies

be exhausted prior to pursuit of independent Unruh Civil

Rights Act and common law remedies, even where a plaintiff

elects not to pursue any remedies under the FEHA?

(3) Does a cause of action exist for wrongful termination in

violation of the public policy against sex discrimination?

The Legal Defense Fund here addresses only the first two of these issues.

- 5 -

STATUTES INVOLVED

The primary statutes at issue on this appeal are California Government Code

sections 12993(a) and 12993(c). They read as follows:

The provisions of this part shall be construed liberally for the

accomplishment of the purposes thereof. Nothing contained

in this part shall be deemed to repeal any of the provisions

of the Civil Rights Law or of any other law of this state

relating to discrimination because of race, religious creed,

color, national origin, ancestry, physical handicap, medical

condition, marital status, sex, or age. (Cal. Gov. Code

§ 12993(a).)

While it is the intention of the Legislature to occupy the field

of regulation of discrimination in employment and housing

encompassed by the provisions of this part, exclusive of all

other laws banning discrimination in employment and housing

by any city, city and county, county, or other political

subdivision of the state, nothing contained in this part shall

be construed, in any manner or way, to limit or restrict the

application of Section 51 of the Civil Code. (Cal. Gov. Code

§ 12993(c).)

- 6 -

ARGUMENT

I.

THE STATUTORY LANGUAGE AND LEGISLATIVE HISTORY OF THE FEHA

CLEARLY SHOW THAT THE LEGISLATURE DID NOT INTEND TO

DISPLACE OTHER STATUTORY AND COMMON LAW REMEDIES.

The Fair Employment and Housing Act states that nothing contained therein

"shall be deemed to repeal any of the provisions of the Civil Rights Law or of any other

law o f this state relating to discrimination because of race, religious creed, color, national

origin, ancestry, physical handicap, medical condition, marital status, sex, or age." (Cal.

Gov. Code § 12993(a) [Italics added].) The Act further provides that "it is the intention

of the Legislature to occupy the field of regulation of discrimination in employment and

housing encompassed by the provisions of this [Act], exclusive of all other laws banning

discrimination in employment and housing by any city, city and county, county, or other

political subdivision o f the state . . . ." (Cal. Gov. Code § 12993(c) [Italics added].) As

the Court of Appeal correctly held, this statutory language and its legislative history

demonstrate that the FEHA was never intended to displace the common law remedies

available to victims of discrimination in employment.

In construing a statute, the intention of the Legislature is to be pursued. (Code

of Civ. Pro. § 1859.) Indeed, ’”[i]t is a fundamental rule that a statute should be

construed in the light of the history of the times and the conditions which prompted its

enactment'" (.People v. Fair (1967) 254 CalA.pp.2d 890, 893, 62 CaLRptr. 632.) The

Court previously has taken judicial notice of amendments to the ac t legislative reports,

letters and legislators' memos to construe the FEHA. (Commodore Home Systems v.

- 7 -

Superior Court (1982) 32 Cal.3d 211, 185, 185 Cal.Rptr. 270.)2 These legislative materials

establish that the California FEPA was modelled after the 1945 New York Law Against

Discrimination, which explicitly recognized the existence of other remedies. They further

establish that the history surrounding California's adoption of the law shows no intent to

displace alternative statutory or common law remedies.3

A. The New York Law Against Discrimination.

The first major legislation in the United States directed against employment

discrimination was adopted by the State of New York in 1945. (N.Y. Sess. Laws 1945,

Ch. 118 § 1, codified at N.Y. Exec. Laws §§ 290-301 [LDF Appendix, at pp. 1-5].) The

adoption of the New York "Law Against Discrimination" led to an immediate

introduction of similar bills in 31 states.4 (Spitz, The New York Law Against

Discrimination (1948) 20 N.Y. State Bar Assoc. Bull. 8. See also Comment, The New

York State Commission Against Discrimination: A New Technique for an Old Problem

(1947) 56 Yale L.J. 837, 839, fn. 6.) The bills were substantially similar, and varied in

2. A concurring opinion in Commodore Home Systems, 32 CaL3d at 221-22, [Mosk,

J. concurring], expressed concern about the use of individual legislators' letters in

construing legislative intent. (See also Friends o f Mammoth v. Board o f Supervisors (1972)

8 Cal.3d 247, 257-58, 104 Cal.Rptr. 761.) The Legal Defense Fund does not here rely

on any such letters.

3. References throughout this brief to legislative materials are to the concurrently

lodged Appendix of Legislative Materials, attached to the Request for Judicial Notice by

Amicus Curiae NAACP Legal Defense and Educational Fund, Inc., and referred to as

"LDF Appendix." The Legal Defense Fund respectfully requests that the Court take

judicial notice of the material contained in such appendix, as set forth in said Request.

4. ”[T]he wider historical circumstances of [a statute's] enactment are legitimate and

valuable aids in divining the statutory purpose." (California Mfrs. Ass'n v. Public Utils.

Comm'n (1979) 24 Cal.3d 836, 844, 157 Cal.Rptr. 676.)

- 8 -

only small details. (See generally Note, Fair Employment Practices — A Comparison o f

State Legislation and Proposed Bills (1949) 24 N.Y.U. Law Quarterly Rev. 398 [comparing

all the pending bills].)

The California FEPA, as finally enacted in 1959, is patterned after the New York

statute. Beginning in 1943, Assemblyman Augustus Hawkins, now a United States

Representative, had tried in vain to get legislation passed to outlaw employment

discrimination in California. His initial efforts were short, general statements of policy.

(Assembly Bill Nos. 41, 42, 50, 1732, 1775 (1943 Reg. Sess.) [LDF Appendix, at pp. 51-

6].) In contrast, the 1945 New York law was extensive and provided for the

establishment of an Employment Discrimination Commission. (LDF Appendix, at pp.

1-5.) In 1945, Assemblyman Hawkins introduced Assembly Bill 3 (LDF Appendix, at

pp. 57-60.) which was in many respects a duplicate of the New York law.5 (Compare,

e.g., Section 131 with Assembly Bill No. 3 (1945 Reg. Sess.) § 8 [LDF Appendix, at pp.

3, 59]. See generally Tobriner, California FEPC (1965) 16 Hastings L J. 333.)

The Report o f the New York State Temporary Commission Against Discrimination

(1945) ("Report") (LDF Appendix, at pp. 6-50.) is a remarkable document, for it details

the history of this legislation, reports the comments of the vast array of supporters at the

5. A detailed comparison of the New York statute and the eventual California statute

is set forth in Note, State Fair Employment Practices Acts (1961) 36 Notre Dame Lawyer

189, 192-94 [hereinafter "Notre Dame Note"] [California's statute "patterned after that of

New York and is substantially similar." It is "almost identical to New York's in

provisions for enforcement, procedure and penalties for violations"].) The complexity of

the bill and its striking similarity to the New York law make it inconceivable that the

California bill was drafted from scratch. The breadth of legislative efforts, spanning the

entire country, clearly shows that there was exchange of ideas and help among politicians

and support groups in the various states.

- 9 -

public hearings6 and provides a detailed explanation of the rationales for and against

each of its proposed sections. The report is the clearest available section by section

explanation of the New York law. This Court may appropriately review this report since

[r]eports of commissions which have proposed statements that are subsequently adopted

are entitled to substantial weight in construing the statements." (Van Arsdale v. Hollinger

(1968) 68 Cal.2d 245, 250, 66 Cal.Rptr. 20.) Although the report is from a New York

commission, an examination of the policies promoted by sister state legislation may be

relevant in determining the policies and purpose of the parallel California legislation."

(Webster v. State Bd. o f Control (1987) 197 Cal.App.3d 29, 37, fn. 3, 242 Cal.Rptr. 685.)

Of particular note is section 135 of the New \ ork Law Against Discrimination.

which contained both the language that is now in California Government Code section

12993(a) and an election of remedies provision:

Construction. The provisions of this article shall be construed

liberally for the accomplishment of the purposes thereof.

Nothing contained in this article shall be deemed to repeal

any of the provisions of the civil rights law or of any other

law of this state relating to discrimination because of race,

creed, color, or national origin; but as to acts declared

unlawful by section one hundred thirty-one o f this article, the

procedure herein provided shall, while pending, be exclushe;

and the final determination therein shall exclude any other

action, civil or criminal, based on the same griev ance o f the

person concerned. I f such individual institutes any action based

on such grievance without resorting to the procedure provided in

this article, he may not subsequently resort to the procedure

herein. (fLDF Appendix, at p. 5] [Italics added}.)

6. Including, we note, the support of Thurgood Marshall then chrector at the L e a .

Defense Fund.

- 10 -

Since the italicized election of remedies" language alternately appears and disappears in

different versions of California assembly bills, it is important to understand what the

drafters meant by this section.

In the Report, a lengthy statement explains that the framers wanted to avoid

multiplicity of litigation, and so decided to force the aggrieved person into an election

of remedies. The Report continues:

Some have argued that the enforcement of the opportunity to

obtain employment without discrimination and of the penalties

for its violation, should be only as provided in the proposed

law. We are satisfied that we have created no new civil right

but have only, as stated in Section 126, recognized and declared

a right created by the natural law, and since 1938 embodied in

the Constitution o f the state. Hence, there would seem to be

no justification for depriving an aggrieved individual of the

opportunity to seek to enforce that right under the provisions

of Sections 700 and 701 of the Penal Law, or of any other

existing civil rights laws, instead of through the state agency,

if such individual first so elects. (Report, at pp. 34-35 [LDF

Appendix, at p. 23] [Italics added].)7

The legislation that our Act was based upon therefore expressly recognized the existence

of rights and remedies beyond the new Law Against Discrimination, and provided that

the aggrieved person was to be permitted to elect his or her avenue of recourse. The

meaning of the language in section 135 of the New York law that "nothing . . . shall be

deemed to repeal any of the provisions of the civil rights law or of any other law of this

state relating to discrimination," is clear: if other remedies had been displaced, there

7. Section 126 is substantially identical to California Government Code section 12921,

which reads in pertinent part: "The opportunity to seek, obtain and hold employment

without discrimination . . . is hereby recognized as and declared to be a civil right." (Cal.

Gov. Code § 12921 [derived from Cal. Lab. Code § 1412, enacted in 1959] [Italics

added].) The New York constitutional provision reads: "No person shall, because of

race, color, creed or religion, be subjected to any discrimination in his civil rights by any

other person or by any firm, corporation or institution, or by the state or any agency or

subdivision of the state."

- 11 -

would be no alternatives to elect.8 The foundation upon which our Act is based

therefore showed an intent not to displace other rights and remedies.

B. Passage of the California FEPA,

The first attempt in California to pass the FEPA (Assembly Bill No. 3 (1945

Reg. Sess.) [LDF Appendix, at pp. 57-60].) met with failure,9 and a long road began for

Assemblymen Hawkins and Byron Rumford. The two apparently agreed to alternate

with other assemblymen introducing the FEPA thereafter. (See Assembly Bill Nos. 3027

(1949 Reg. Sess.), 2251 (1951 Reg. Sess.), 900, (1953 Reg. Sess.), 971 (1955 Reg. Sess.),

and 7 (1957 Reg. Sess.) [LDF Appendix, at pp. 61, 65, 69, 74, 78].) Although the yearly

submissions were substantially similar, there were variations. Of particular note is that

some versions of the bill appeared with the above-quoted "election of remedies" language

found in New York's section 135. (See Assembly Bill No. 900 (1953 Reg. Sess.) § 12;

Assembly Bill No. 7 (1957 Reg. Sess.) § 1431 [LDF Appendix, at pp. 73, 81].) We have

found no existing legislative material explaining this sometime appearance. In all

likelihood, the California drafters either assumed it to be surplusage, or did not want to

force an election - it would be left to the courts under the doctrine of collateral

8. The CELC amicus curiae brief argues at length that this language, now in section

12993(a), was meant to refer only to statutory provisions. (CELC Brief, at p. 21.) This

argument puts too fine a point on the text. The words were added to save "from any

implication of repeal all existing laws relating to discrimination." {Report, supra, at p. 34 )

Given the election of remedies provision and the recognition of rights under the natural

law and the state constitution, no one can argue that the framers intended any

substantive distinction between common law and statutory law.

9. An ill-fated decision was made to place the statute on the general ballot as a

referendum. Proposition 11 on the November 1946 ballot attempted to enact the

duplicate of Assembly Bill 3. The proposition met with failure. (Tobriner, supra, at p

- 12 -

estoppel to determine the effect upon subsequent actions of a prior administrative or

judicial determination upon the merits.

It is clear, however, that the mere omission of the New York election of remedies

language, while retaining the "no repeal" language now in section 12993(a), does not

indicate an attempt to make the remedy exclusive. On the contrary, the New York

Commission added the election of remedies language to force a choice between the civil

rights law and other laws on the one hand, and the new procedure on the other.

Without this language there would be no prohibition on concurrent actions.

The general election of 1958 was a milestone in the history of the FEPA in

California. The voters elected Edmund Brown, Sr. as Governor, and he made the

passage of the FEPA a centerpiece of his legislative program. (LDF Appendix, at p.

156.) In 1959 the FEPA was finally enacted, and the Fair Employment Practices

Commission ("FEPC") was created to enforce the law. The version of the FEPA that

was introduced that year did not contain the express "election of remedies" language; as

finally enacted section 1431 read, in pertinent part10:

The provisions of this part shall be construed liberally for the

accomplishment of the purposes thereof. Nothing contained

in this act shall be deemed to repeal any of the provisions of

the Civil Rights Law or of any other law of this State relating

to discrimination because of race, religious creed, color,

national origin or ancestry.

Thus, absolutely no intent to preempt pre-existing remedies appears in the legislative

history. On the contrary, it explicitly recognizes and accommodates these pre-existing

remedies.

10. The second paragraph of section 1431 pertained to preemption, and is discussed

in the next section of the Brief.

- 13 -

II.

THE LANGUAGE AND LEGISLATIVE HISTORY OF CURRENT CALIFORNIA

GOVERNMENT CODE SECTION 12993(c) DEMONSTRATE THAT IT WAS

INTENDED ONLY AS A PROCEDURAL DEVICE TO PREEMPT

LOCAL AND COUNTY ORDINANCES.

Respondents attempt to enlist Government Code section 12993(c) to support their

argument that the FEPA displaces other rights of action. This distorts section 12993(c)

to a purpose never intended nor conceived by its drafters. The history of this section

is merely an epilogue to the story of the courageous fight to end discrimination against

blacks and other minorities in the early 1960's. It is, however, a short story that bears

telling, for it demonstrates that Respondents are trying to twist a procedural provision

of civil rights legislation to now curtail the ability of minorities and women to redress

discrimination.

The history begins with the passage of the FEPA in 1959, which contained a clear

preemption of conflicting local and municipal ordinances. The next chapter takes place

in 1963, when an amendment to preempt local ordinances was added to the Hawkins

Fair Housing Act, literally at the eleventh hour before passage. The final chapter takes

place in 1978, when as part of clean-up legislation to the FEPA, the preemption

language of the Hawkins Fair Housing Act was borrowed to update the earlier

preemption language in the 1959 FEPA.

A. The 1959 Preemption Provision in FEPA.

As we noted above, the battle to enact a fair employment law in California

spanned 14 years. It was not until just days before the 1959 legislation was enacted into

- 14 -

law, however, that any language ever appeared in any version o f the FEPA from 1945 to

1959 having anything whatsoever to do with preemption of local and municipal

ordinances. Since different assemblymen alternated bills each year, there was some

variation from year to year, but none of these versions included any predecessor

language to section 12993(c).

The effort to enact civil rights legislation was nationwide, and in addition to the

statehouse attempts to pass such legislation, numerous municipalities, including San

Francisco, were apparently enacting such laws when the statewide efforts stalled. (See

Notre Dame Note, supra, at pp. 199-200 [listing numerous local ordinances].) Of course,

the ability of such local jurisdictions to enact such laws in the face of statewide

legislation was questioned. (Id.) Further, once those opposing enactment of statewide

laws banning discrimination saw the inevitable passage of such legislation, their last

efforts quite naturally would have been to prohibit any local laws which might go even

further than the statewide legislation.

This is exactly what happened. The original version of Assembly Bill No. 91,

Regular Session 1959, was introduced on January 7, 1959. (LDF Appendix, at pp. 82-

5.) On its third Senate reading on April 7, 1959, the Bill was amended to add the

following italicized language as a second paragraph to section 1431, which is clearly

directed against the possibility of inconsistent municipal laws:

The provisions of this part shall be construed liberally

for the accomplishment of the purposes thereof. Nothing

contained in this part shall be deemed to repeal any of the

provisions of the Civil Rights Law or of any other law of this

state relating to discrimination because of race, religious

creed, color, national origin, or ancestry.

Nothing contained in this act shall be deemed to repeal

or affect the provisions o f any ordinance relating to such

- 15 -

discrimination in effect in any city, city or county, or county at

the time this act becomes effective, insofar as proceedings

theretofore commenced under such ordinance or ordinances

remain pending and undetermined. The respective administrative

bodies then vested with the power and authority to enforce such

ordinance or ordinances shall continue to have such power and

authority, with no ouster or impairment o f jurisdiction, until

such pending proceedings are completed, but in no event beyond

one year after the effective date o f this act. (LDF Appendix,

at p. 101].)

This was the text of enacted Labor Code section 1431.11 (LDF Appendix, at p. 106].)

B. The 1963 Hawkins Fair Housing Law.

As we detailed above, 1959 was the turning point in the fight to prohibit

discrimination against blacks and other minorities in California. In addition to the Fair

Employment Practices Act, the 1959 Legislature also passed the Hawkins Fair Housing

Law of 1959, which banned discrimination in publicly assisted housing, and the Unruh

Civil Rights Act, which amended and strengthened Civil Code section 51. In 1961,

Assemblyman Hawkins introduced Assembly Bill No. 801, Regular Session 1961, in an

attempt to extend the Unruh Civil Rights Act and the Hawkins Fair Housing Law to all

housing. (LDF Appendix, at pp. 110-13.) This bill contained no language concerning

preemption of municipal ordinances. The bill was the subject of great controversy and

was sent for interim study, (LDF Appendix, at p. 129.), a move which effectively killed

the bill.

Governor Brown then made it part of his civil rights program to have changes

made to the existing fair housing laws, (LDF Appendix, at pp. 157-58.), and on

11. Section 1431 was renumbered section 1432 in 1967. (Stats 1967, c. 1506, p. 3574,

§ 3.)

- 16 -

February 14, 1963, Assemblyman Byron Rumford of Berkeley introduced Assembly Bill

1240 to provide an alternative administrative remedy for housing discrimination. (LDF

Appendix, at pp. 130-32.) As noted above, an election of remedies provision was

sometimes included in FEPA bills, sometimes not. With respect to housing, however,

one of the early amendments to Assembly Bill 1240 explicitly required this election.

Section 35731 of the bill was amended in the Senate on May 15, 1963, (LDF Appendix,

at p. 141.), and as enacted provided:

However, no such complaint may be made or filed unless the

person claiming to be aggrieved waives any and all rights or

claims that he may have under Section 52 of the Civil Code

and signs a written waiver to that effect. (Cal. Health &

Safety Code § 35731 [repealed 1977], reenacted as Cal. Lab.

Code § 1422.2 [repealed 1980].)

In the meantime, the city council of Berkeley, Assemblyman Rumford's home

district, had passed a fair housing ordinance similar to Assembly Bill 1240, which was

then still pending. (The Friends Committee on Legislation, The Story o f the 1963

California Legislature (1963) at p. 19 ['7963 Legislature"] [LDF Appendix, at p. 162].)u

Opponents immediately secured signatures for a referendum vote, which was set for

April 2, 1963. (Id.) The Berkeley election was viewed by both proponents and

opponents of Assembly Bill 1240 as a test vote, indicating whether the people wanted

legislation of this type. The ordinance lost in an 82% turnout by only 2,477 votes out 12

12. The Friends Legislative Report is a news media report, which may be judicially

noticed and examined to garner the historical background of the b ill (See, e.gi,

American Tobacco Co. v. Superior Court (1989) 208 CaLApp3d 480, ___, 255 CaLRptr.

280, 283 [examined "contemporaneous news accounts of the legislation"]; Diamond View

Ltd. v. Herz (1986) 180 Cal.App.3d 612, 619, 225 CaLRptr. 651 [cited Newsweek]', People

v. Tanner (1979) 24 Cal.3d 514, 547-549, 156 CaLRptr. 450 [Newman. J_ concurring]

[relying upon, e.g., the San Francisco Chronicle, This World, Los Angeles Times, and the

Sunday Punch].)

■ 17 -

of 43,043 cast. {Id.) Although defeated, the Berkeley referendum showed that there was

considerable popular support for prohibiting discrimination in housing, and proponents

pushed the bill with renewed determination. The bill was now stalled in the Senate,

where proponents were resisting repeated attempts to eviscerate the bill with amend

ments. {Id., at p. 20.)

Extensive amendments were added to Assembly Bill 1240 on June 21, the last day

of the session, and hurriedly approved in a meeting of Finance Committee members in

the back of the Senate early in the evening. {Id., at p. 21.) It is in this eleventh hour

amendment process that language similar to that now found in section 12993(c) first

appears. The text of what was to become California Health & Safety Code section

35743 was:

As it is the intention of the Legislature to occupy the whole

field of regulation encompassed by the provisions of this part,

the regulation by law of discrimination in housing contained

in this part shall be exclusive of all other laws banning

discrimination in housing by any city, city and county, county,

or other political subdivision of the State. Nothing contained

in this part shall be construed to, in any manner or way, limit

or restrict the application of Section 51 of the Civil Code.

(LDF Appendix, at p. 146.)

As with the preemption language then found in California Labor Code section

1431, this section clearly was directed against inconsistent local ordinances, all the more

so given the cause celebre of the Berkeley experience. Since this "occupy the field"

language was added long after the election of remedies amendment, and while such

election language remained in the bill, it is obvious that the "occupy the field" language

was not intended to displace the alternative state law remedies. If it did displace those

- 18 -

remedies, then there would have been no reason to execute a waiver of rights under

Civil Code section 52, because there would have been no such rights.

Senators Burns and Bradley then engaged in a series of parliamentary moves that

almost guaranteed that the midnight deadline would arrive before a vote. (1963

Legislature, supra, at pp. 21, 24.)13 At 10:40 p.m., in a tense vote, the Senate

nevertheless voted to make Assembly Bill 1240 a special order of business, and at 11:10

p.m. the bill passed. The bill was rushed back to the Assembly for concurrence in the

amendments, including the new "occupy the field" provision. The final vote was taken

at 11:50 p.m., at which point the Assembly gave Byron Rumford a standing ovation and

spectators sang "We Shall Overcome." {Id., at p. 24.)

The election of remedies provision in the new Rumford Fair Housing Act of

course implied that there was something else to elect.14 This is precisely how the FEPC,

the administrative body enforcing the new law, interpreted it. After passage, the

Division of Fair Employment Practices ("DFEP") of the FEPC published a newsletter

noting the passage of the Rumford Fair Housing Act, and the transfer to the DFEP of

enforcement responsibility. In the newsletter, the DFEP reported:

The legislation, whose author is Assemblyman W. Byron

Rumford of Berkeley, will be administered by FEPC under

basically the same procedures as the fair employment law.

A n aggrieved person has a choice, however, between filing a

complaint with the Commission and going to court under

Section 52 o f the Civil Code. (Italics added)

13. There are no pages 22, 23 in the Friends Report, 1963 Legislature, apparently

due to a typographical error.

14. As discussed below, this election of remedies is no longer in the Act.

- 19 -

(13 Fair Employment Newsletter (1963) at p. 1 [LDF Appendix, at p. 168]. See also 11

Fair Employment Newsletter (1963) at p. 2 [Act gives aggrieved persons "the option"]

[LDF Appendix, at p. 167].)15 Further, in an analysis of the bill, Edward Howden,

FEPC Executive Officer, stated:

The person or family encountering discrimination in the

housing market may now file a complaint with the State FEP

Commission, which will investigate and, where warranted,

bring about a proper correction of the situation. Formerly the

aggrieved home-seeker could secure redress only by retaining an

attorney and going to court. Now he may choose between these

two avenues o f recourse. (Italics added)

(E. Howden, Fair Housing and the Role o f Law, 14 Fair Employment Newsletter (1963)

at p. 2 [LDF Appendix, at p. 170].) Therefore, when the language of section 12993(c)

made its first appearance, no one suggested that it would displace alternative remedies.

Indeed, the Legislature recognized the continued existence of these remedies.

C. The 1978 Clean-Up Amendments to FEPA.

The final step in the evolution of the two preemption provisions found in Health

& Safety section 35743 and Labor Code section 143216 took place in 1978. In that year

the FEPC proposed extensive amendments to the FEPA, which first appeared as Senate

amendments to Assembly Bill 1915 on March 6, 1978. (LDF Appendix, at pp. 178-86.)

Section 21 of the bill deleted the existing language of section 1432, which placed a one

15. The Fair Employment Newsletter is an official report of the activities of the

Commission. (Tobriner, supra, at p. 341.)

16. Labor Code section 1431 had been renumbered section 1432 in 1967. (Stats.

1967, c. 1506, p. 3574, § 3.)

- 20 -

year limit on existing ordinances, as quoted above, and replaced it with language almost

identical to that found in Health & Safety Code section 35743:

It is the intention of the Legislature to occupy the whole field

of regulation of discrimination in employment encompassed

by the provisions of this part. The regulation of

discrimination in employment by this part shall be exclusive,

except as provided by this part, of all other laws banning

discrimination in employment by any city, city and county,

county, or other political subdivision of the State. Nothing

contained in this part shall be construed, in any manner or

way, to limit or restrict the application of Section 51 of the

Civil Code. (LDF Appendix, at p. 185.)

Since the amendments were authored by the FEPC, we are fortunate to have a

Section-By-Section Analysis of Assembly Bill 1915, prepared by William H. Hastie, Jr.,

Executive Officer of the FEPC. (LDF Appendix, at pp. 226-31.) Referring to the

changes to section 21, he writes:17

The amendments to the law in this section are both

procedural, clean up, and substantive. . . ,[T]he effort to clean

up and update is directed at the presently existing preemption

against local agencies attempting to regulate employment

discrimination. (Italics added.)

(Fair Employment Practices Commission, Section-By-Section Analysis o f A B 1915, at 5

[LDF Appendix, at p. 230].) It is therefore clear that this language was directed solely

to preemption of local ordinances. Since the earlier section 1432 language was clearly

out of date -- it referred to the one year limitation that already had expired - the

17. The construction of a statute by a State agency responsible for its administration

and enforcement is entitled to great weight and will not be overturned by the courts in

the absence of a showing that the construction is clearly erroneous or unauthorized.

(National Muffler Dealers Assoc, v. United States (1979) 440 U.S. 472, 476-77, 99 S.Ct

1304; Coca-Cola Co. v. State Bd. o f Equalization (1945) 25 Cal2d 918, ___, 156 P.2d 1,

2-3; Casteneda v. Holcomb (1981) 114 Cal.App3d 939, 945-46, 170 Cal.Rptr. 875.)

- 21 -

drafters took the parallel language found in California Health & Safety Code section

35743 as the pattern.

The Senate amended this language once more on May 10 to provide:

Whale it ft is the intention of the Legislature to occupy the

whole field of regulation of discrimination in employment

encompassed by the provisions of this part:—The regulation

of discrimination—in—employment—by—this—part—shah—be

exclusive, except as provided by this part, exclusive of all

other laws banning discrimination in employment by any city,

city and county, county, or other political subdivision of the

state, nothing State.—Nothing contained in this part shall be

construed, in any manner or way, to limit or restrict the

application of Section 51 of the Civil Code or the right of

local agencies to regulate discrimination in employment by

public contractors.

(May 10, 1978 Senate Amendments to Assembly Bill No. 1915. [Added text in gray

background] [LDF Appendix, at p. 194].) William Hastie explained to Assemblyman

Dixon, the Bill's sponsor, that this amendment:

concerns the revised language of pre-emption contained in

new subsection 1432(c). This statement is revised to tone

down its sweeping language and to clarity that local agencies

may continue to regulate contract compliance efforts of local

public contractors. (Italics added)

(Letter from William Hastie, Jr. to Assemblyman Juhan Dixoc. catec May 9. TJDF

Appendix, at p. 233].)“ This language demonstrates, once axar_ .ne m em to resrrka

only the application of local ordinances.w

It. Tat last phrase of this proposed aoguage vat ssar. atesesz n erx t enaraaKE.

(LDF Apfeatk, at p. 709.% fwt m taunt n M trrtim mmsam osar.

ML ThrCELC m m amkw curiae 0/kf'm w pjm *0 Map—le t . Ha: tag

w e ■/, M a ' / ' w . -v: • - - ' • -

hactrji v. '<g acavrr a. asitkStim.

.g.-.','- ‘.-a n c y s r ; ' / w p t i t & B t g U W : i " - - t c c r r : |T2CJSs: 9 A s

D. The Final Merger of Section 1432 and Section 35743.

The final form of California Government Code section 12993(c), adopted in 1980

when the housing and employment acts were merged into the Government Code, can be

seen clearly as the successor to the two preemption provisions of section 1432 and

section 35743. There is no contrary legislative history - section 12993(c) has reference

only to local ordinances, as the Court of Appeal held there.

III.

THE RALPH CIVIL RIGHTS ACT OF 1976

CREATED A SEPARATE, INDEPENDENT AND CONCURRENT REMEDY

TO FIGHT VIOLENCE BASED UPON DISCRIMINATION.

In their First Amended Complaint, the Appellants have, in addition to their

common law claims, sought to state a statutory claim under section 51.7 of the Civil

Code. Nothing in the FEHA can preempt these claims, because these claims explicitly

were intended to supplement the FEHA.

In 1976, the Legislature sought to address a special problem in the fight to end

discrimination - violence and the threat of violence associated with busing and fair

housing. As explained by a report prepared by the Governor's Office of Legal Affairs:

19.(...continued)

Civil Code for local prosecution of violations of the Unruh Civil Rights Act by city and

district attorneys. (Cal. Civ. Code §§ 52(c), 52(d).) The language "restrict the

application of section 51," read in context with the amendment to section 35743 clarifying

the authority of local governments, and the FEPC comment on that amendment, could

have no other reference than to the power of local governments to enforce the Unruh

Civil Rights Act. The CELC is therefore wrong in suggesting that this provision is

surplusage.

- 23 -

Last year in Taft, California, Black students were forced to

leave town because of threats of physical violence. Blacks

moving into formerly white neighborhoods reportedly suffer

property damage, intimidation, and threats of violence. This

appears to be particularly true in rural counties, such as

Colusa County, where blacks have suffered property damage

and have been forced to give up residence due to violence

and threat of violence.

(Governor's Office of Legal Affairs, Enrolled Bill Report on AB 2986 (Sept. 22, 1976)

[LDF Appendix, at p. 254].)

The existing fair housing law did not provide an adequate remedy for this

violence, since an aggrieved person could not bring a simultaneous civil action and

administrative complaint. As we noted above, before a complaint could be filed with the

FEPC concerning a housing complaint, a written waiver of rights had to be signed. This

forced election between civil and administrative procedures had become a problem, due

to the burgeoning backlog of the FEPC, now 17 years old; greater protection from acts

of violence was needed.

In response, Assemblyman Ralph introduced Assembly Bill 2986 on February 4,

1976. The bill as originally introduced (LDF Appendix, at pp. 234-36.) added a new

section to the Civil Code declaring all persons to have the right to be free from violence

committed against them because of discrimination, provided for a new private right of

action to redress violations of this provision, and gave authority to the FEPC to

investigate violations of this new section. (Cal. Civ. Code §§ 51.7, 52(b); Cal. Lab. Code

§ 1419(f)(2) [repealed 1980], reenacted as Cal. Gov. Code § 12930(f)(2).) The express

intention of this bill was to create simultaneous avenues of relief. As explained in a

staff analysis from the Ways and Means Committee:

Under current law, any person filing a complaint with the

Fair Employment Practices Commission is precluded from

- 24 -

initiating civil action on the same issue. Given the backlog

of cases handled by the FEPC, thus preventing immediate

relief, and the impossibility of receiving substantial awards for

damages, this bill states that while the FEPC shall receive and

investigate such infringements on civil rights, the complainant

shall have the right to pursue any other remedy or procedure.

The racial violence in Taft, California last year, during which

black students were threatened with violence and chased out

of town, would indicate that greater protection of fundamental

civil rights is justified.

The Fair Employment Practices Commission would be

directed to receive, investigate, and pass on complaints

alleging violation of these rights. In this instance, FEPC

administrative remedies would be independent o f any other civil

procedure. (Italics added)

(Ways & Means Staff Analysis (April 30, 1976) [LDF Appendix, at p. 252].) The

Assembly Office of Research echoed this statement of legislative purpose in its

comments on the Assembly Third Reading:

The purpose of this measure is to provide . . . for immediate

relief by allowing a complainant a right to initiate private civil

action as well as use the enforcement mechanisms of the Fair

Employment Practices Commission.

(Assembly Office of Research, Third Reading Analysis of AB 2986 [LDF Appendix, at

p. 253].)20

In the first amendments to Assembly Bill 2986 on April 26, two parallel provisions

were added to the bill to clarify that the right of private action and the right of the

FEPC to investigate were independent of each other, with no requirement of exhaustion.

20. The assertion in the CELC amicus curiae brief that the "Legislature has recognized

the importance of the DFEH's role . . . by requiring that a person who claims to be the

victim of discrimination file an administrative complaint," CELC Brief, at p. 8, is

therefore obviously constructed of whole cloth.

- 25 -

New section 52(e), part of the right of private action under the Unruh Civil Rights Act,

was amended to provide:

Actions under this section shall be independent of any other

remedies or procedures that may be available to an aggrieved

party. (LDF Appendix, at p. 238.)

At the same time, the section granting authority to the FEPC to investigate violations

of the Unruh Civil Rights Act was amended to add: "The remedies and procedures of

this part shall be independent of any other remedy or procedure that might apply."

(LDF Appendix, at p. 239.)

These two corollary provisions remained in the final bill that was signed into law,

and are now found in California Civil Code section 52(e) and California Government

Code section 12930(f)(2), respectively. The independent status of these two provisions

was later underscored when in 1978 two further parallel sections were added to the

Civil Code, confirming that an aggrieved person "may also" file an administrative claim,

in addition to his or her section 52 claim.21

The language of these sections stands unaltered today, and proves beyond doubt

that the right to pursue a civil action under the Unruh Civil Rights Act is independent

of any remedy under the FEFLA, is in addition to such remedies, and can be pursued

simultaneously. Moreover, when the housing and employment acts were in 1980

combined into the Government Code, the Legislature dropped the election of remedies

provision in its entirety. This can only be interpreted as dispensing with the need to

21. (Cal. Civ. Code § 52(f) ["Any person claiming to be aggrieved by an alleged

unlawful practice in violation of section 51 or 51.7 may also file a verified complaint

with the Department of Fair Employment and Housing"]; Cal. Lab. Code § 1420.8

[repealed 1980], reenacted as Cal. Gov. Code § 12948.) If the Respondents' argument

that all administrative remedies had to be exhausted was correct, section 52(f) would,

at the very least, not include the word "also."

- 26 -

elect remedies. Appellants should therefore be permitted to pursue their claims under

sections 51 and 51.7 of the Civil Code.

IV.

CASELAW IS CONSISTENT WITH THE STATUTORY LANGUAGE AND LEGISLATIVE

HISTORY; COMMON LAW REMEDIES HAVE NOT BEEN DISPLACED,

NOR MUST THEY BE DEFERRED PENDING EXHAUSTION

OF ADMINISTRATIVE REMEDIES.

Respondents and CELC ignore or are unaware of the legislative history discussed

above. They also suggest that the Court of Appeal rendered its decision with respect to

preemption and exhaustion in the face of "established authority to the contrary."22 The

weight of authority, however, in fact supports the Court of Appeal. The FEHA did not

preempt common law or other statutory remedies, nor did it interpose a requirement

that administrative remedies be exhausted before these remedies could be pursued.

A. Preexisting Remedies Were Not Displaced By The FEHA.