Thurgood Marshall Legal Society and Black Pre-Law Association v Hopwood Reply Brief of Respondents in Opposition to Certiorari

Public Court Documents

March 29, 1996

14 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Thurgood Marshall Legal Society and Black Pre-Law Association v Hopwood Reply Brief of Respondents in Opposition to Certiorari, 1996. 84826c1a-bd9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c2bb361e-9cae-46f1-abe4-ace04beb9f89/thurgood-marshall-legal-society-and-black-pre-law-association-v-hopwood-reply-brief-of-respondents-in-opposition-to-certiorari. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

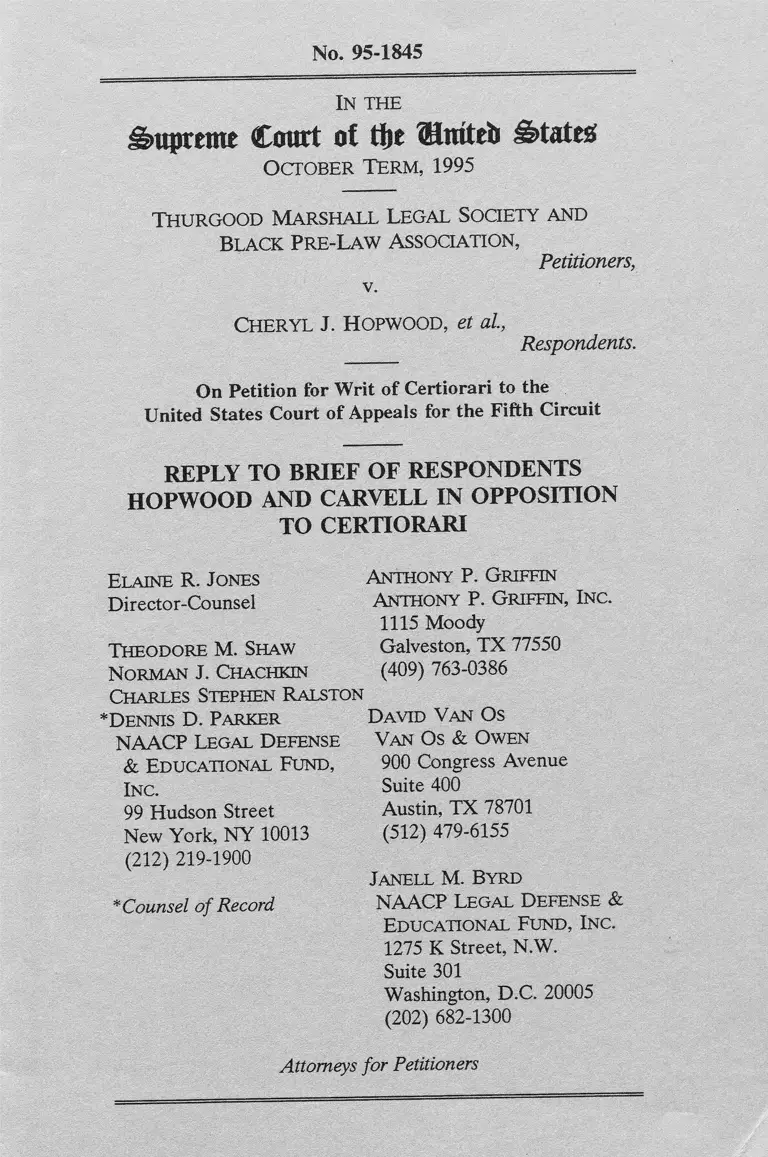

No. 95-1845

IN THE

Supreme Court of tfje ®triteb States*

October Term , 1995

Thurgood Marshall Legal Society and

Black Pre-Law Association,

Petitioners,

v.

Cheryl J. H opwood, et al,

Respondents.

On Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the

United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

REPLY TO BRIEF OF RESPONDENTS

HOPWOOD AND CARVELL IN OPPOSITION

TO CERTIORARI

Elaine R. Jones

Director-Counsel

Theodore M. Shaw

Norman J. Chachkin

Charles Stephen Ralston

* Dennis D. Parker

NAACP Legal Defense

& Educational Fund,

Inc.

99 Hudson Street

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-1900

* Counsel of Record

Anthony P. Griffin

Anthony P. Griffin, Inc.

1115 Moody

Galveston, TX 77550

(409) 763-0386

David Van Os

Van Os & Owen

900 Congress Avenue

Suite 400

Austin, TX 78701

(512) 479-6155

Janell M. Byrd

NAACP Legal Defense &

Educational Fund, Inc.

1275 K Street, N.W.

Suite 301

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 682-1300

Attorneys for Petitioners

Page

Table of Authorities . .............................................. • • • i

ARGUMENT ............................................................ • • 1

Conclusion ........................................................................9

Table of Authorities

Cases:

Aiken v. City of Memphis,

37 F.3d 1155 (6th Cir. 1994) .............. ..............7

Billish v. City of Chicago,

989 F.2d 890 (7th Cir.), cert, denied,

114 S. Ct. 290 (1993)........................................... 8

Ensley Branch, N.A.A.C.P. v. Seibels,

31 F.3d 1548 (11th Cir. 1994) ................... • - 7-8

Forest Conservation Council v. United States

Forest Serv., 66 F.3d 1489 (9th Cir. 1995) . . 5, 6

Meek v. Metropolitan Dade County,

985 F.2d 1471 (11th Cir. 1993) ...........................6

Trbovich v. United Mine Workers,

404 U.S. 528 (1972)...................................... 4n, 5

TABLE OF CONTENTS

i

Statutes and Rules:

28 U.S.C. § 2101(c) . .......... .............................................2

S. Ct. R. 10.1(a) . ............... ..........................................3n

n

In the

Supreme Court of tfte WLmttb £btateg

October Term , 1995

NO. 95-1845

Thurgood Marshall Legal Society and

Black Pre-Law association,

Petitioners,

v.

Cheryl J. Hopwood, et al,

Respondents.

On Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the

United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

REPLY TO BRIEF OF RESPONDENTS

HOPWOOD AND CARVELL IN OPPOSITION

TO CERTIORARI

Respondents labor mightily but, we believe,

ultimately unsuccessfully, to cloud the issues arising

from the approach taken by the court of appeals to

the question of intervention by African-American

students in this "reverse discrimination" case. Only a

few points require reply. 1

1. Jurisdiction of this Court. Respondents

confuse the issue of this Court’s jurisdiction to review

a judgment with the scope of the questions it may

consider once it has determined to grant review. The

argument that the Court lacks jurisdiction to review

the court of appeals’ 1994 ruling affirming the district

court’s first denial of intervention, because no

2

petition seeking review was filed within ninety days

(as required by 28 U.S.C. § 2101(c)), is beside the

point. As explicitly stated at p. 1 of the Petition, the

Thurgood Marshall Legal Society and the Black Pre-

Law Association have requested that this Court

review only the March 18,1996 judgment of the court

of appeals. Their Petition was unquestionably timely

filed for this purpose.

To be sure, Petitioners seek review so that this

Court may clarify the law and correct the errors

which led the court below to enter that erroneous

judgment. These include the grossly inappropriate

refusal by the court of appeals — ostensibly applying

the "law of the case" doctrine to an earlier decision

rendered under different factual circumstances1 - to *

'We agree with Respondents that we "‘made clear

[our] intention to raise questions about the discriminatory

effect of the use of the Texas Index as an admissions

sorting device’" in briefing the first appeal (Br. Opp. at 17,

quoting Pet. at 26). The panel on the first appeal did not

hold, explicitly or implicitly, that intervention could not be

justified for the purpose of assuring that this evidence was

presented. Rather, its decision implied precisely the

opposite - because the panel affirmed the trial judge’s

denial of intervention based upon its assumption that

intervention was unnecessary to assure that the evidence

would be introduced:

Although the BPLA and TMLS may have ready

access to more evidence than the State, we see no

reason they cannot provide this evidence to the

3

reach the m erits o f Petitioners’ appeal from the

district court’s denial of their second request to

intervene in the action.2

State. The BPLA and the TMLS have been

authorized to act as amicus and we see no

indication that the State would not welcome their

assistance. BPLA and TMLS have not met their

burden of demonstrating that they have a separate

interest that the State will not adequately

represent. The proposed intervenors have not

demonstrated that the State will not strongly

defend its affirmative action program. Nor have

the proposed intervenors shown that they have a

separate defense of the affirmative action plan that

the State has failed to assert. See, Jansen v.

Cincinnati, 904 F.2d 336 (6th Cir. 1990).

(App. 98a-99a.) Following this action by the first panel,

the State refused to present the evidence questioning the

validity of the Texas Index as an admissions criterion.

The propriety of denying intervention under these

circumstances — diametrically opposite those anticipated

by the first panel - therefore had never been ruled upon

by the first panel and the second panel’s refusal to

consider the issue on the ground of "law of the case" was

patently in error.

Petitioners believe that the application of the "law of

the case" doctrine by the court below "so far departed

from the accepted and usual course of judicial

proceedings . . . as to call for an exercise of this Court’s

power of supervision." S. Ct. R. 10.1(a).

4

But the approach of the panel below also

reflected the established and incorrect Fifth Circuit

standard for determining whether proposed

intervenors’ interests will be adequately represented

by existing parties. The court of appeals’ holding

that Texas’ refusal to introduce the evidence

proffered by Petitioners did not amount to sufficient

"changed circumstances" justifying intervention flowed

directly from its adherence to the requirement that

proposed intervenors must demonstrate "that the

present parties will inadequately represent the

proposed intervenors’ interests" (App. 72a n.59

[emphasis added]). That standard, of course, is

inconsistent with the principles announced in

Trbovich3 and followed by many other Circuits. The

fact that the decision in Petitioners’ appeal from the

first denial of intervention rested principally upon

this same incorrect legal standard hardly insulates it

from correction by this Court in these proceedings.

Considering and correcting that legal error in

the course of reviewing the 1996 judgment of the

court of appeals will not involve retrospective

reopening and reversal or modification of the earlier

1994 judgment, even assuming arguendo that it was a

"final" order requiring immediate appeal.4 Hence,

3Trbovich v. United Mine Workers, 404 U.S. 528 (1972).

ASee Br. Opp. at 14-16, noting unsettled state of the

law on this question. This Court need not resolve the

question in order to decide this case.

there is no jurisdictional impediment preventing this

Court’s review of the intervention question decided

below.

2. Conflict among the Circuits. Respondents

assert that we have manufactured a conflict among

the Courts of Appeals about the standard to be

applied in judging adequacy of representation where

intervention is sought on the same side of an action

on which a governmental agency is a party. They

imply, for example, that the Ninth Circuit now

follows the more stringent parens patriae presumption

of adequacy, citing Forest Conservation Council v.

United States Forest Serv., 66 F.3d 1489, 1498-99 (9th

Cir. 1995). The distinction between the approach of

the Ninth Circuit panel and that of the court below

could not be greater, however.

The Ninth Circuit court begins its

consideration of adequacy of representation by

recognizing that a proposed intervenor’s "burden in

showing inadequate representation is minimal: it is

sufficient to show that representation may be

inadequate. Trbovich v. United Mine Workers [citation

omitted]." 66 F.3d at 1498. While the court goes on

to recognize that "‘a presumption of adequate

representation generally arises when the

representative is a governmental body or officer

charged by law with representing the interests of the

absentee,’" [citations omitted], it holds that the

presumption is no more difficult to overcome than it

would be to meet the general rule of Trbovich.

6

In the Ninth Circuit’s view, a demonstration

that the interests of the proposed intervenors are not

identical with the general public interest that the

governmental agency must uphold suffices to "satisf[y]

the minimal showing required that the Forest Service

may not adequately represent their interests in

defending against the issuance of a broad injunction,"

66 F.3d at 1499 [emphasis supplied]. The trial court’s

denial of intervention was reversed because ”[t]he

Forest Service is required to represent a broader view

than the more narrow, parochial interests of the State

of Arizona and Apache County." Id. Accord, Meek

v. Metropolitan Dade County, 985 F.2d 1471, 1478

(11th Cir. 1993)("the intervenors sought to advance

their own interests in achieving the greatest possible

participation in the political process. Dade County,

on the other hand, was required to balance a range

of interests likely to diverge from those of the

intervenors. . . . These divergent interests created a

risk that Dade County might not adequately

represent the applicants").5

Thus, there is a real and significant difference

in approach among the Courts of Appeals on the

standard for intervention that warrants this Court’s

review.

5We apologize to the Court for the typographical

error at p. 19 of the Petition, at which this case was cited.

The pinpoint citation should have read "1477-78" rather

than "n.77-78."

7

3. The relevance o f petitioners’ evidence about the

Texas Index. Respondents attempt to minimize the

significance of the evidence about the Texas Index’s

invalidity by characterizing it as "quixotic" (Br. Opp.,

at 19 n. 10) and citing three cases for the proposition

that "the use of an invalid test does not justify

subsequent race-conscious decision-making to

‘remedy’ the use of the invalid test." Id. [emphasis

in original]. However, each of the decisions cited by

Respondents recognized that following a

demonstration that a test or other selection process

was invalid and had a discriminatory effect, race

conscious re lie f is p ro p er un til valid,

nondiscriminatory procedures can be implemented.

Each of the cited decisions condemned as not

"narrowly tailored" the continued, long-term use of

race-conscious measures by public agencies that

exhibited no interest in developing and validating new

selection criteria.

See Aiken v. City o f Memphis, 37 F.3d 1155,

1164 (6th Cir. 1994) (en banc) ("over 15 years ago the

City stipulated that it is ‘currently in the process of

developing’ such procedures, and that ‘development

of fully validated processes is two to three years from

accomplishment’ . . . Yet, incredibly, the City

continues to make police and fire department

promotions according to procedures that have not

been validated as racially neutral. This dereliction

cuts against a finding that the race-based remedies at

issue here are narrowly tailored"); Ensley Branch,

N.A.A.C.P. v. Seibels, 31 F.3d 1548, 1571 (11th Cir.

1994) ("The goal of eliminating discrimination may

8

justify some interim use of affirmative action, but

affirmative action selection provisions are themselves

a form of discrimination that cannot continue forever.

An end to racial discrimination demands the

development of valid, non-discriminatory selection

procedures to replace race-conscious selection

procedures. . . . [T]he single most important race-

neutral alternative contained in the decrees was the

requirement that the Board develop and put in place

non-discrim inatory selection procedures--a

requirement that the Board has not satisfied"); Billish

v. City o f Chicago, 989 F.2d 890, 894-95 (7th Cir.) (en

banc) ("Of course if the city had a desperate need for

twenty captains just then, and the only eligibility list

it had was based on a quite possibly biased

examination that had been given in 1979, a modest

departure in favor of remedial racial balance might

well be justified. . . . But the record does not reveal

whether the city had an urgent need for twenty

captains and thus could not await the administering

and scoring of an unbiased exam"), cert, denied, 114

S. Ct. 290 (1993).

Thus, far from being "quixotic," Petitioners’

evidence, if it had been presented to the trial court,

would have justified race-conscious relief until truly

nondiscriminatory admissions criteria could be

developed by the University of Texas Law School.

4. Reversal of the judgment below will not require

this Court to decide issues other than those raised in the

Petition. In a final attempt to complicate this matter,

Respondents assert that if this Court grants review,

9

it will be required "to resolve numerous fact-specific

questions not passed upon by the lower courts" (Br.

Opp., at 20). None of those questions was answered

by the court of appeals, and the answer to none of

those questions was articulated by the panel as the

basis for its judgment. This Court therefore need not

deal with any of those questions in order to correct

the legal errors by the court below that did undergird

its judgment.

Conclusion

For the reasons stated herein, as well as those

given in the Petition, the Writ of Certiorari should be

issued.

Respectfully submitted,

Elaine R. Jones

Director-Counsel

Theodore M. Shaw

Norman J. Chachkin

Charles Stephen Ralston

Dennis D. Parker

NAACP Legal Defense

& Educational Fund,

Inc.

99 Hudson Street

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-1900

Anthony P. Grifein

Anthony P. Griffin, Inc.

1115 Moody

Galveston, TX 77550

(409) 763-0386

David Van Os

Van Os & Owen

900 Congress Avenue

Suite 400

Austin, TX 78701

(512) 479-6155

* Counsel of Record

10

Janell M. Byrd

NAACP Legal Defense &

Educational Fund , Inc.

1275 K Street, N.W.

Suite 301

Washington, D.C. 20005

(202) 682-1300

Attorneys for Petitioners