Watson v. Fort Worth Bank and Trust Brief Amici Curiae

Public Court Documents

October 6, 1986

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Watson v. Fort Worth Bank and Trust Brief Amici Curiae, 1986. e6a6e2b5-c89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c2c09ab8-b9bb-4abb-b476-1d776cb22ae4/watson-v-fort-worth-bank-and-trust-brief-amici-curiae. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

\

1

l

1

9

4

5

534

m

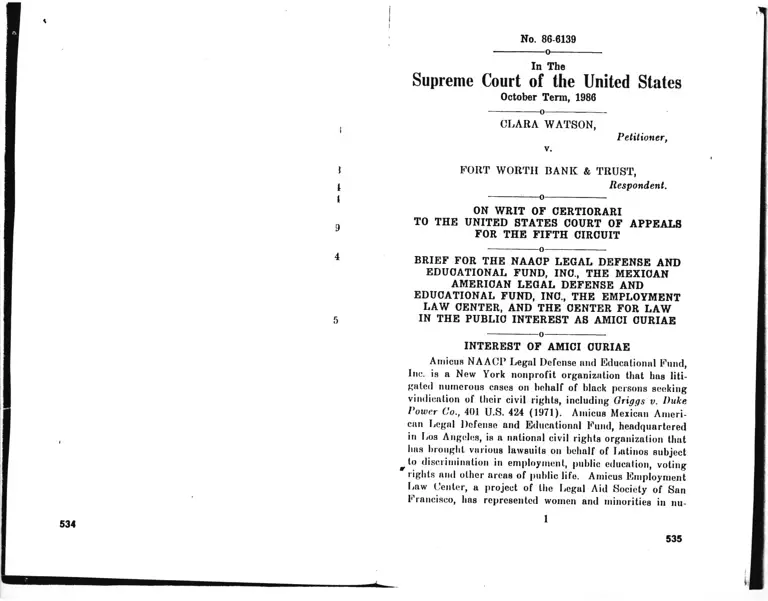

No. 86-0139

-------------- o-------------- -

In The

Supreme Court of the United States

October Terra, 1986

-------------- o---------------- -

CLARA WATSON,

Petitioner,

v.

FORT WORTH BANK & TRUST,

Respondent.

o

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI

TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

--------------o-------------- —

BRIEF FOR THE NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC., THE MEXICAN

AMERICAN LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATIONAL FUND, INC., THE EMPLOYMENT

LAW CENTER, AND THE CENTER FOR LAW

IN THE PUBLIC INTEREST AS AMICI CURIAE

--------------o------------------

INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE

Amicus NAACP Legul Defense and Educational Fund,

Inc. is a New York nonprofit organization that hue liti

gated numerous enses on behalf of black persons seeking

vindication of their civil rights, including Griggs v. Duke

Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971). Amicus Mexican Ameri

can Legal Defense and Educational Fund, headquartered

in Los Angeles, is a national civil rights organization that

has brought various lawsuits on behalf of Latinos subject

^ to discrimination in employment, public education, voting

rights and other areas of public life. Amicus Employment

Law Center, a project of the Legal Aid Society of San

Francisco, has represented women and minorities in nu-

1

535

2

morons employment discrimination cases, including Cali

fornia Federal Savings and Loan Association v. Guerra,

— U.S. —, 107 S.Ut. fJB.'t (11)87). Amicus Center for Law

in the Public Interest is a non-profit corporation located

in Los Angeles that for many years has prosecuted civil

lights and public interest lawsuits, including employment

discrimination class actions on behalf of women and minor

ities. Letters from the parlies consenting to the filing of

this brief have been filed with the Court.

--------------o--------------

INTRODUCTION

The Court granted certiorari to consider whether an

employer’s selection or promotion practices may lie in

sulated from disparate impact scrutiny under Title VII of

the Civil Rights Act of 19(>4, 42 U.S.C. ^ 2000e to 2000c-

17 (1982 ed. & Supp. Ill), simply bccuuse they are subjec

tive. Amici will uddress the merits of the issue so as to

respond to the arguments made by tbe United States in its

amicus curiuo brief supporting the petition for certiorari.

Preliminarily, however, we have grave doubts that this

important legal issue is properly presented by the case

now before the Court. The record reflects that the peti

tioner relied upon disparate treatment analysis in the trial

court, and could not prove a case of denial of promotions

based on disparate impact.* 1 * 1'Jvcn if this Court were to

'The evidence presented al trial was typical of a disparate

treatment case. Petitioner testified as to her qualifications and

the fact that she had applied for three promotions; the defen

dant presented evidence that purported to establish legitimate,

non-discriminatory reasons for each promotion action. Those

reasons focused on the relative qualifications of the persons

selected and the legitimacy of the employer's actions. Evidence

was also presented showing a low hire rate and slower promo

tion rate for blacks.

The district court found—and those findings are not chal

lenged here— that throughout the relevant lime period, the re

spondent employed a total of only 15 blacks, and that at any

one time, the number of blacks employed never exceeded eight

(Continued on following page)

536

3

hold that disparate impact analysis should be applied to

subjective employment practices, ns we urge below, the

petitioner would be unable to establish a violation of Title

VII on that basis. Accordingly, it is appropriate to dis

miss certiorari ns improvidcnlly granted.

Should the Court reach the merits in this—or another

-case , amici urge the Court to reject the government’s

proposed exemption for subjective employment practices.1

(Continued from previous page)

The particular complaint of the plaintiff is that she was dis-

cnmmatorily denied promotions on three occasions The dis-

l" c{ c” urt. fV.rl êr found ‘hat, in addition to plaintiff, only one

other black had applied for promotions given to whites Thus

blacks applied for and were denied a total of five promotions.'

Memorandum Opinion of District Court at 13 (Nov. 21 1984)-

Testimony of Sylvia Harden, Tr. Vol. Ill, at 98-99. Such num

bers do not permit a showing of disparate impact, since they

cannot establish any pattern of the effect of an employment

practice. The government agrees. See Brief for the United States

as Amicus Curiae, at 20 n. 16.

J1 he line between subjective and objective employment

practices is not as bright as the government suggests.

|A]lmost all criteria necessarily have both subjective and

obiective elements. For example, while the requirement

o a certain lest score may appear ''objective,'' the choice

of skills to be tested and of the testing instruments to

measure them involves "subjective" elements of judgment

Such apparently "subjective" requirements as attractive an-

pearance in fact include "objective" factors. Thus the terms

represent extremes on a continuum . . . .

Atonio v. Wards Cove Packing Co., 810 F.2d 1477 1485 fmh

Cir. 1987) (en banc). In the words of one commentator "fm lost

employment decisions contain some element of sub ectivitv"

Comment Applying Disparate Impact Theory to Subjective Em

ployee Selection Procedures, 20 Loy. L A L. Rev. 375, 400 (1987)

See also_ I amber, Discretionary Decisionmaking: The Applica

tion of Title VII c Disparate Impart Theory, 1985 U III F Rev

869. 874 n.14 ("In a sense all decisions-Tmm the p e hunch

to the choice of using a dearlv defined objective rule-involve

discretion. ). Cl. Nation v. Winn-Dixie Stores Inc 567 F 5nnn

917 1005 n 20 (N O. C . l ("M l. is especially £ The

context of promotions to formulate employer derisionmakinp

cnteria that are romoletely free of subjectivity."), ail’d on reli'e

570 F Supp 1473 (N.D. Ga. 1983). g'

537

4

Such an exemption ia directly contrary to Title V II’a plain

meaning, the prior decisions of this Court, specific legis

lative history, tin; Justice Department’s own guidelines on

employee selection, and the prophyluclic purpose of the

statute.

The government would permit nn employer to make

personnel decisions on tin; basis of “ subjective” criteria—

<‘ven if those criteria are “ unrelated to measuring job

capability,” Griggs v. Duke l'ower Co., 401 U.S. 424, 4,'12

(1971), and result in I lie disproportionate exclusion of

minorities and/or women so long ns those delusions are

made in good faith. The alternative, it is argued, would

he to interfere with the employer’s management preroga

tives. See Brief for the United Slates as Amicus Curiae

at 14-17. Yet management prerogatives are necessarily cir

cumscribed by Title VII’s essential purpose of “ achiev

|ing] cqunlily of employment o pportun ity |.” Griggs,

401 IJ.S. at 429. They cannot he permitted to shield dis

crimination, “ subtle or otherwise.” McDonnell Dougins

Corp. v. Green, 411 U S. 792, 801 (1978). Accordingly, this

Court has consistently rejected arguments founded on the

notion of employer discretion where that discretion would

he exercised in n manner contrary to Title V II’s prohibi

tory pronouncements. In llishon v. King <(J Spalding, 407

IJ.S. G9, 78 (1984), for example, the Court held that Title

VII applied to the partnership decisions of a law firm, not

withstanding the possible infringement on that firm’s

rights of expression and association. Cf. id. at 80 n.4

(Powell, J., concurring) (“ [Ij]aws that bnn discrimination

. . . may impede the exercise of jiersonal judgment . . . . ” ).

And last term, the Court rejected government arguments

based on policy considerations relating to the prerogatives

of unions. Goodman v. Lukcns Steel Go., — II.S. —, - ,

107 S.Ct. 2017, 2024-25 (1987).J Whether or not such pre

rogatives are diminished by the application of disparate 3

35ee Brief (or ihe United Stales as Amicus Curiae at 19-24,

Goodman v. Lukens Steel Co., 107 S.Ct. 2617 (1907).

538

5

impact analysis to subjective employment practices, “ Con

gress has made the choice, and it is not for us to disturb

it ” Chandler v. Houdcbusli, 425 U.S. 840, 804 (1970) (re

jecting government’s proffered interpretation of Title VII

in face of plain meaning of statute and its legislative his

tory).

-------------- o— ————

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

“ A disparate impact claim reflects the language o f 1

§ 703(a)(2),” Connecticut v. Teal, 457 U.S. 440, 448 (1982).

I h(> plain terms of the statute provide absolutely no basiB

for exempting the entire category of subjective employ

ment practices from the scope of $ 703(a) (2). Had Con

gress intended to exempt subjective criteria, it well knew

how to do so. See llishon v. King <t! Spalding, 407 U.S.

09, 77-78 (1984) (“ When Congress wanted to grant an

employer . . . immunity, it expressly diil so.” ).

The legislative history of the 1972 amendments to

Title VII demonstrates that Congress ratified and en

dorsed the Court’s decision in Griggs v. Duke Power Co.,

401 U.S. 424 (1971), and contemplated its application to

all employment practices, including subjective criteria, hav

ing a discriminatory impact on minorities and women. In

particular, Congress specifically indicated, with respect

to the federal government’s personnel system, that Griggs

applied to its subjective selection criteria. The adminis

trative regulations issued by the agencies charged with

enforcement responsibility confirm that Congress intended

the disparate impact analysis to apply to “ the full rungo

of assessment techniques from traditional paper and pen

cil tests . . . through informal or casual interviews and un

scored application forms.” 29 C.h’.Ii. $ 1007.10Q (198G).

Limiting $ 703(a)(2) disparate impact analysis to ob

jective criteria would frustrate Title V II’s primary goal

of “ «<:l>iev(ing] equality of employment opportunities.”

Griggs, 401 U.S. at 429. Moreover, the exclusion of sub

jective practices from disparate impact analysis would

539

6

make employers less inclined to ‘‘ ‘self-examine and self-

evaluate [their] employment practices,’ ” Albemarle

Paper Co. v. jMoody, 422 U S. 405, 418 (1975) (quoting

United States v. N.f,. Industries, 479 F.2d 354, 37!) (Hlh

Fir. 1973)), as contemplated by Title VII.

ARGUMENT

The government would exempt from disparate impact

analysis all practices and procedures of n subjective nature

—i.e., discretionary selection devices such ns evaluative

interviews, performance appraisals, and essay examina

tions. Application of the disparate impact analysis would

he li mi ted to objective criteria—i.e., noil-discretionary se

lection devices such as height and weight requirements,

see Dothard v. Hawlinson, 433 IJ.iS. 321, 324 (1977), me

chanically scored intelligence tests, (Iriggs v. Duke Power

Co., 401 U.S. 424, 427-28 (197.1 ), and diploma requirements,

id* Accordingly, the government would make intent the

Bole focus of most Title VII litigation. Sec sujira note 2.

Hut just like their non discretionary counterparts, discre

tionary selection criteria can “ opernte as ‘built-in head

winds’ for minority groups (and women),” (Iriggs, 401

U.S. at 432, even in the absence of discriminatory intent.

See infra at 24-25.5 Whether an employment practice is ob

jective or subjective should not and cannot ‘‘provide! u line

*Ct. W. Cascio, Applied Psychology in Personnel Manage

ment 129 (2d ed. 1902) ("The method of scoring a test may be

objective or non-objective. In the former case, there are fixed,

impersonal standards for scoring . . . . On the other hand, the

process of scoring essay tests and certain types of personality

inventories . . . may be quite subjective . . . ."); D. Baldus & ).

Cole, Statistical Proof of Discrimination § 1.23 (1900 & 1906

Supp.) (distinguishing between "nondiscrelionary criteria" and

criteria that are "discretionarily . . . applied"). Hut see supra

note 2.

’ Under the government's proposed exemption for subjec

tive criteria, a non-discretionary requirement of supervisory ex

perience might be shielded simply by taking that experience

into account through a discretionary requirement of "leadership"

ability. See infra at 26.

540

7

of demarcation to guide courts in choosing the appropriate

analytic tool in a Title VII discrimination case.” Atonio

v. Wards Cove Packing Co., 810 F.2d 1477, 1485 (9th Cir.

1087) (cm banc),

1 THE LANGUAGE OF TITLE VII SUPPORTS THE

APPLICATION OF DISPARATE IMPACT AN

ALYSIS TO SUBJECTIVE CRITERIA

As the Court noted in Connecticut v. Teal, 457 U.S.

440, 448 (1982): “ A disparate-impact claim reflects the

language of $ 703(a)(2).” Nothing in the statute can be

read to exclude subjective employment practices from that

section’s reach.

A. Section 703(a)(2) Is a Crucial Element of Title

VII’s Comprehensive Enforcement Scheme

The two subparts of % 703(a) reflect the intent of Con

gress to proscribe ‘‘not only overt discrimination but also

practices that are fair in form, but discriminatory in oper

ation.” (Iriggs, 401 U.S. at 431.

It shall be an unlawful employment practice for an

employer—

(1) to fail or refuse to hire or to discharge any

individual, or otherwise to discriminate against any

individual with respect to his compensation, terms

conditions, or privileges of employment, beenuse of

such individual’s race, color, religion, sex, or national

origin; or

(2) to limit, segregate, or classify his employees

or applicants for employment in any wny which would

deprive or tend to deprive any individual of employ

ment opportunities or otherwise adversely affect his

status as an employee, because of such individual’s

race, color, religion, sex, or national origin.

42 U fS C. $ 2000e 2(a). Section 703(a)(2) is concerned

with ‘‘the consequences of employment practices,” (Iriggs

401 U.S. at 432 (emphasis in original), for which disparate’

impact analysis is appropriate.

The § 703(a) enforcement scheme evidences no intent

to restrict a plaintiff to subpart ( I ) as an exclusive remedy

541

8

for any category of employment practices. Section 70.1(a)

is a comprehensive framework, embracing all forms of

employment discrimination by providing overlapping guar

antees against both the overt discrimination to which $703

(a)(1) is primarily directed,6 as well as tbe denial of equal

employment “ opportunities” with which $ 703(a)(2) is

concerned, Teal, 457 U S. at 440; Griggs, 402 U.S. at 431.

B. Section 703(a)(2) Draws No Distinctions Among

Different Employment Practices

Section 703(a)(2), by its terms, prohibits practices

that “ limit, segregate, or classify . . . employees or appli

cants . . . iti any way” so ns to deprive an individual of

employment opportunities on the basis of race, sex, oi

some other protected characteristic. 42 U.S.C. $ 2000e-2

(a)(2) (emphasis added). It nowhere suggests that sub

jective practices should he exempted, and indeed, diaws

no distinction between objective and subjective employ

ment criteria. Accordingly, the government’s attempt to

draw such a distinction should he rejected: |T |he

plain, obvious and rational meaning of a statute is always

to bo preferred to any curious, narrow, hidden sense that

nothing hut the exigency of a hard case and the ingenuity

and study of an acute and powerful intellect would dis

cover.’ ” Chandler v. llovdebush, 425 U.S. at H4H (quoting

Lynch v. Alworth-Stephens Co., 2G7 U.S. 3G4, 370 (1025)).

'Pile most natural reading of § 703(a)(2) is that all em

ployment practices arc covered by its broad prohibition

and may come under disparate impact scrutiny. As this

6A violation of § 703(a)(1) may also he established by show

ing that a practice is facially discriminatory. See City of Los

Angeles v Manhart, 435 U.S. 702 (1978); Phillips v. Mailin Mari

etta Corp., 400 U.S. 542 (1971). Several lower courts have held

' that disparate impact challenges may also he brought under

§ 703(a)(1). See, e g., Colby v. 1C Penney Co., 811 F.2d 1119

1127 (7th Cir. 1987); Wambheim v. 1C. Penney C o , 705 F 2d

1492 1494 (9lh Cir. 1983), cert, denied, 467 U.S. 1255 (1984);

cl Nashville Gas Co v. Salty, 434 U.S. 136, 144 (1977) (1 ho

Court "need not decide whether . . . it is necessary to prove

intent to establish a prima facie violation of § 703(a)(1) ").

542

9

Court noted in Franks v. Boivman Transportation Co., 424

U.S. 747, 703 (197G) (emphasis added): “ Congress in

tended to prohibit all practices in whatever form which

create inequality in employment opportunity due to dis

crimination on the basis of race, religion, sex, or national

origin.”

0. The Asserted Exemption From $ 703(a) (2) Is

Found Nowhere in the Language of Title VII,

and Must Be Rejected

The government would exempt a whole category of

employment practices from § 703(a) (2) ’s coverage, though

no such exemption appears in the language of that section

or the other provisions of Title VII. That absence of text

ual support is telling: “ When Congress wanted to grant

an . . . immunity, it expressly did so.” llishon v. King &

Spalding, 4G7 U.S. G9, 77-78 (1984) (rejecting assertion of

immunity for partnership decisions); In l’l Bhd. of Team

sters v. United States, 431 U.S. 324, 349 (1977) (“ Were it

not for $ 703(h), the seniority system in this case would

seem to fall under (lie Griggs rationale.” ).

For example, Congress Bpecificnlly exempted the use

of bona fide occupational qualifications based on religion,

sex or national origin, $ 703(e)(1), 42 U.S.C. $ 2000e-2(e)

(1), see Phillips v. Martin Marietta Corp., 400 U.S. 542,

544 (1971); bona fide seniority or merit systems, $ 703(h),

42 U.S.C. § 2000c-2(h), see Teamsters, 431 U.S. at 350 5G

(exemption applying to ■§ 703(a)(2) cases only); ability

tests “ not designed, intended or used to discriminate,”

$ 703(h), 42 U.S.C. § 2000c-2(h), see Griggs, 401 U.S. at

433-36; and certain preferential treatment of Indians,

§ 703(i), 42 U.S.C. ■$ 2000e 2(i), sec Morton v. Mancari,

417 U.S. 535, 545 (1974). Congress also provided express

exemptions for the employment practices of Indian tribes

and certain agencies of the District of Columbia, § 701(h)

(1), 42 U.S.C. § 2000e(b)(l); small businesses nnd bona

fide private membership clubs, $ 701(h)(2), 42 U.S.C.

$ 2000e(h) (2); certain religious organizations, § 702, 42

U.S.C. §2000e-l; and certnin religious educational insti

tutions, $ 703(e) (2), 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(e) (2).

543

10

Here, tlie government would liuvo this Court create—

where Congress did not—a § 703(a)(2) exemption for sub

jective employment practices and exclude them from dis

parate impact scrutiny. Hecuuse tliut usserted exemption

falls outside the express language of Title VII, however,

it must he rejected. Sec llishon, 407 U.H. at 77-78.

II. THE COURT’S DECISIONS SUPPORT APPLICA

TION OF DISPARATE IMPACT ANALYSIS TO

SUBJECTIVE CRITERIA

This Court’s dicisions are consistent with the above-

proffered construction of $ 703(a)(2). In Albemarle Taper

Co. v. Moody, 422 U.S. 405, 432-33 (1075), the Court ac

knowledged difficulty in determining whether subjective

appraisals, executed ns part of a validation study, had

measured job-related ability. The same concern exists

when such appraisals constitute the employment practice

being challenged. Implicit in the Court’s opinion is the

recognition thnt, notwithstanding a lack of discriminatory

intent, minorities and women might be adversely affected

by discretionary practices that do not closely relate to job

capability.

While the Court has not specifically discussed the ap

plication of disparate impact analysis to subjective employ

ment practices, it has never excluded any practice from

the scope of $ 703(a)(2).7 * Moreover, the Court has eon-

7Those practices "clearly fall[ ing] within the literal lan

guage of § 703(a)(2)," Tea/, 457 U.S. at 440, include written

examinations, Albemarle, 422 U.S. at 425; Griggs, 401 U.S. at

433, educational requirements, id., height and weight require

ments, Dothard, 433 U.S. at 328-29, a policy against employing

persons who use narcotic drugs, New York City Transit Authority

v Beazer, 440 U.S. 568, 584-87 (1979), and a residual category

of practices that perpetuate the effects of prior discrimination,

Teamsters, 431 U.S. at 349 ("One kind of practice 'fair in form,

but discriminatory in operation' is that which perpetuates the

effects of discrimination "). Of course, within such a residual

category, one would expect to find subjective, as well as ob

jective employment practices. See Brown v. Gaston County

Dyeing Machine Co., 457 F.2d 1377, 1382 (4th C ir) (" | e jlusive

[and] purely subjective standards" may effectively perpetuate

past discrimination), cert, denied, 409 U.S. 982 (1972)

544

11

sistently spoken in broad-brush terms such as “ practices,”

“ criteria,” and “ barriers”—terms that clearly encompass

both subjective and objective practices—in discussing and

applying the disparate impact theory.*

That subjective practices are susceptible to challenge

under the disparate treatment analysis of $ 703(a)(1) does

not mean that they ure not susceptible to challenge under

the disparate impact analysis of $ 703(u) (2). As the Court

acknowledged in Teamsters, 431 U.S. at 335 n.15, “ [ejither

theory may, of course, be applied to a particular set of .

facts.” An objective selection criterion may be discrim

inatory either because its adoption is traceable to a dis

criminatory motive,9 or because the practice has an un

justified discriminatory effect. The some is true for a sub

jective selection criterion. The government, without men

tioning Teamsters, argues tliut this Court expressly de-

*5ee, eg ., Griggs, 401 U.S. at 430 ("practices, procedures,

or tests"); id. at 431 ("criteria for employment"); id. at 432

("any given requirement"); Dothard, 433 U.S. at 328 ("arbitrary

barrier to equal employment opportunity"); Beazer, 440 U.S.

at 584 ("an employment practice nas the effect of denying . . .

equal access to employment opportunities"); Teal, 457 U.S. at

448 ("nonjob-related barrier"). Cl. General Tel. Co. ol South

west v. Falcon, 457 U.S. 147, 159 n.15 (1982) ("Title VII pro

hibits discriminatory employment practices," including "sub

jective decisionmaking processes.") (emphasis in original).

95ee, eg ., United States v Georgia Power Co., 695 F.2d

890, 893 (5th Cir. 1903) (non-discrelionary seniority system

"maintained out of an unlawful purpose"); Sears v. Dennett,

615 F.2d 1365, 1374 (10th Cir. 1901) (seniority system "main

tained with the purpose of discriminating against black em

ployees"), cert, denied, 456 U.S. 964 (1902); Chicago Police

Ollicer's Ass'n v. Stover, 552 F.2d 918, 921-22 (10th Cir. 1977)

Rase remanded for determination of whether employment test

having discriminatory impact was adopted with discriminatory

intent); cl. Wallace v. City ol New Orleans, 654 F.2d 1042, 1047

(5th Cir. 1901) (police department's adoption of height/weight

requirement held not a product of intentional discrimination);

Hicks v. Crown Zellerhach Corp., 319 F.Supp. 314, 318 (E.D.

la 1970) ("There was no claim that defendants had adopted

the tests for the express purpose of capitalizing on these dif

ferential passing rales . . . .").

545

12

dined to npply $ 703(a)(2) to discretionary employment

practices in McDonnell Douglas Corp. v. Green, 411 U.S.

71)2 (1973), and Furnco Construction Corp. v. Waters, 438

U.S. 5G7 (1978). Sec Brief for the United States ns Amicus

Curino at 11-12. A close look ut those cases, however, dem

onstrates otherwise.

In McDonnell Douglas, there was simply no assertion

of disparate impact. The plaintiff's claims were limited

to disparate treatment and retaliation under $$ 703(a)(1)

and 704, see 411 U.S. at 796-98, 807; a § 703(a) (2) claim

was never made. Indeed, the plaintiff made no effort to

establish any group-wide effects of the practice at issue.

See id. at 805. Thus, the ense neither holds nor implies

that $ 703(a)(2) disparate impuet analysis is inapplicable

to subjective practices.

Nor does Furnco support such a contention.10 The

Court granted certiorari “ to consider important questions

raised by th[c| case regarding the eiact scope of the priina

facie case under [the] McDonnell Douglas (disparate treat

ment approach] and the nature of the evidence ncccssnry

to rebut such a case.” Id. at 569. The Court agreed with

the court of appeals that the plaintiff had made out a

prima facie case of disparate treatment, but reversed on

the issue of the defendant’s burden of rebuttal. The gov

ernment’s assertion that the Court “ expressly refused to

apply disparate impact analysis,” Brief for the United

States as Amicus Curiae at 12, is incorrect: A disparate

impact claim was not before the Court. While the Court

loln Furnco, several black applicants for employment chal

lenged. on both disparate impact and disparate treatment

grounds, an employer's practice of hiring only those applicants

who were known by the superintendent or who were otherwise

recommended. The district court rejected both claims, finding,

1 on the impact claim, that blacks as a group were not dispro

portionately excluded by the employer's selection process. 430

U.S. at 572. The court of appeals reversed on the disparate

treatment claim, id. at 573-74, and the employer sought and

petitioned for certiorari only on disparate treatment issues.

See id. at 574 n.6 (questions presented in petition for certiorari)

546

13

noted that the selection procedure nt issue in Furnco “ did

not involve employment tests which we[re] dealt with in

Griggs . . . and in Albemarle . . ., or particularized require

ments such as the height and weight specifications con

sidered in Dotliard . . .,” id. at 575 n.7, it cannot be con

cluded that the Court intended this bare listing to announce

a decisional rule restricting use of the disparate impact

nnalysis to objective criteria." Although the government

fails to mention it, the Court also noted, in the same dis

cussion, (hat Furnco “ was not a . . . case like Teamsters

. . id., in which the employment practices at issue were

discretionary in nature. See Teamsters, 431 U.U. at 338

n.19. ’There is, in short, nothing in Griggs or its progeny

that would limit use of the dispurate impact analysis to

objective criteria.

III. LEGISLATIVE HISTORY SANCTIONS APPLICA

TION OF THE DISPARATE IMPACT ANALYSIS

TO SUBJECTIVE PRACTICES

While “ lujndoubtedly disparate treatment wus the

most obvious evil Congress had in mind when it enacted

Title V l l” in 1964, Teamsters, 431 U.S. at 335 n.15, “ it

was clear to Congress tliut * 11 ]ho crux of the problem

[was] to open employment opportunities for Negroes in

occupations which have been traditionally closed to them,’

"First, the complained-of practice in Furnco was itself non-

discretionary or objective in nature: The employer simply

"refusfedj to consider . . . applications at the gate." Furnco,

430 U.S. at 576 n.0. Second, while the employment practices in

Griggs, Albemarle, and Dotbard all might have been susceptible

to disparate treatment analysis, in none of those cases would

the McDonnell Douglas approach have been appropriate. To

make out a prima facie case under McDonnell Douglas, the

plaintiff must show "that be . . . was qualified for ( tliej job"

at issue. 411 U.S. at 002 (emphasis added). However, the

Plaintiffs in Griggs, Albemarle, and Dothard brought suit be

cause discriminatory selection criteria bad rendered them "un

qualified." Thus, perhaps the Court meant only to suggest that

the case before it was (unlike Griggs, Albemarle, and Dotbard)

susceptible to the McDonnell Douglas approach, and not that

the plaintiff was foreclosed from making a disparate impact

challenge.

547

14

110 Cong. Rec. 6548 (1064) (remarks of Sen. Humphrey),

and it is to this problem that Title V II’s prohibition against

racial discrimination in employment wns primarily ad

dressed.” United Steelworkers v. Weber, 443 U.S. 103,

203 (1070). Ry 1072, when it enacted several major amend

ments to Title VII, Congress fully understood that (lie

opening of those opportunities could not be achieved by

the eradication of just intentional discrimination. See

S. Rep. No. 415, 02d Cong., 1st Sees. 14 (1071) [herein

after “ S. Rep. No. 415” ] (“ [WJhero discrimination is in

stitutional, rather than merely a matter of bad faith, . . .

corrective measures appear to be urgently required.” );

see also 117 Cong. Rec. 32103 (Sept. 16, 1071) (remarks of

Rep. Fraser) (“ Often the source of discriminatory pat

terns is inertia rntlier than deliberate intent. Rut that

docs not lessen the injustice and economic damage done to

the recipients.” ).

The 1072 amendments, among them a broadening of

$ 703(a)(2) to include “ applicants for employment,” see

Equal Employment Opportunity Act of 1072, Rub. L. No.

02-261, 86 Stat. 103, 100, were the result of a thorough re

view by Congress of both the stntuto and the existing case

lnw, including this Court’s Griggs decision. Indeed, “ 111lie

legislative history . . . demonstrates that Congress recog

nized and endorsed the disparuto-impuct analysis employed

by the Court in Griggs,” Teal, 457 U.S. at 447 n.8, and

contemplated its application to all employment practices

having a discriminatory effect.12

In extending to state and municipal employees the

protections of Title VII—“ ns interpreted by Griggs,” id.

,2This Court has relied upon the 1972 legislative history

not only in Teal, 457 U.S. at 447 n.8, but also in Franks, 424 U.S.

■at 764 n.21, 796 n.18 (Powell, J., concurring in part and dis

senting in part), Albemarle, 422 U.S. at 420-21, and johnson

v. Railway Express Agency, 421 U.S. 454, 459 (1975). Compare

Teamsters, 431 U.S. at 354 n.39 (little, if any, weight given to

1972 legislative history in light of clear language of § 703(b),

which was unaffected by 1972 amendments).

548

15

at 449 Congress was concerned with “ both institutional

and overt discriminatory practices,” and specifically iden

tified “ stereotyped misconceptions by supervisors regard

ing minority group capabilities” as having perpetuated

the effects of past discrimination. II.R. Rep. No. 238 92d

Cong., 1st Sess. 17 (1971) [hereinafter “ II.R. Rep. No.

238” ] (emphasis added); see also S. Rep. No. 415, at l(h

Congress also relied upon a report authored by the United

.States Commission on Civil Rights, which specifically iden

tified “ supervisory ratings” as a “ [bjnrrierjJ to equal

opportunity.” U.S. Commission on Civil Rights For All

Hie People . . . Ry All the People-A Report on Equal

Opportunity in State and Local Government Employment

119 (1969), reprinted in 118 Cong. Rec. 1817 (1972) See

Teal, 457 U.S. at 449 n. 10.

The extension of Title VII to federal employees was

grounded in similar concerns about both subjective and

objective practices. Quoting the presidential memorandum

accompanying Executive Order 11478, both Committee re

ports declared that “ discrimination of any kind based on

factors not relevant to job performance must be eradicated

completely from Federal employment.” II R Re ,, No

238, at 22-23; S. Rep. 92-415, at 13 (emphasis added).'2

Indeed, legislative hislory is particularly instructive

with regard to the selection procedures of the federal gov

ernment. At the Senate hearings, Rep. Fauntroy of the

District of Columbia testified concerning the numerous

complaints received from his constituents regarding dis

crimination by federal agencies. lie was particularly crit

ical of the Civil Service Commission’s focus on attempting

to find supervisors with malicious intent “ rather than

focusing on personnel policies that have the inherent cf-

"Congress was well aware of the widespread existence of

discretionary employment practices in the federal government

See II.R. Rep. No. 238, at 24 (referring to employees' fears that

administrative complaints "will only result in antagonizing their

supervisors and impairing any hope of future advancement")- S Rep. No. 415, at 14 (same). ’ ’

549

feet of discriminating against Mack, Spanish surname and

women employees.” 14

In (lie eourse of the hearings in the House of Rep

resentatives on what was to heroine the 1972 Act, there was

a speeific foeus on the question of whether the Civil Ser

vice Commission had validated all of its selection pro

cedures and instruments. Thus, the Chair of the House

Committee asked not only whether Civil Service tests and

written examinations Inul been validated, hut also if other

selection techniques had (icon validated.15 The Civil Ser

vice Commission, in reply, identified selection techniques

other than tests as including the evaluation of the experi

ence and training of applicants or employees, and went on

to state: ‘‘In a few instances interviews are a part of

the examination process. In other cases, and in the pro

motion program particularly, the appraisals of an indi

vidual’s job performance and potential are considered in

relation to the job to he filled.” 16 * * With regard to all these

qualification requirements, the Civil Service Commission

claimed that: ‘‘The showing of direct relationships of job

demands to the qualification requirements . . . is fully in

conformity with the Supreme Court decision in Griggs v.

Duke Dower Co.’’11

1G

>4Equal Employment Opportunities Enforcement Act of

1971, Hearings before tbe Subcommittee on Labor of (he Senate

Committee on labor and Public Welfare on S.2515, S.26I7, and

H R. 1746, Oct. 4, 6 and 7, 1971, p. 205.

’’ Letter to John H Dent, Chairman, General Subcommittee

on Labor, Committee on Education, and Labor, U S. House of

Representatives, from Irving Kalor, Assistant Executive Director,

United Stales Civil Service Commission, April 23, 1971, repro

duced in Equal Employment Opportunity Enforcement Proced

ures, I learings before the General Subcommittee on Labor of the

House Committee on Education and Labor on H R. 1746, March

3, 4, and 18, 1971, pp. 362-03.

l6/d. at 383.

,7/d. As part of its submission, the Civil Service Commis

sion introduced into the record tbe text of the 1969 Federal

Personnel Manual Supplement (FPM) 335-1. Evaluation of Em-

(Continued on following page)

550

17

(liven the criticisms of the Commission it had heard,

Congress was understandably skeptical. Therefore, the

House and Senate reports echoed Representative Faun-

troy’s criticisms and instructed:

I he Commission should be especially careful to en

sure that its directives issued to Federal Agencies

address themselves to the various forms of systematic

discrimination in the system----- It apparently has not

I idly recognized that the general rules and procedures

that it his promulgated may in themselves constitute

systematic barriers to minorities and women.

f , N°- 92-415, 92d Cong, 1st Hess, 1971, p. 14.

The Senate report goes on to state:

The Committee expects the Civil Service Commission

to undertake a thorough reexamination of its entire

testing and qualification program to ensure that the

standards enunciated in the Griggs case are fully met.

Id. at 14-15. See also II. Rep. No. 92-238, 92d Cong, 1st

Sess, 1971, pp. 24-25. In short, it is clear beyond any rea

sonable question that in 1972 Congress specifically man

dated that the Griggs rule apply to all forms of selection

and qualification requirements.

Finally, when Congress enacted the amendments to

Idle VII, the courts had uniformly extended disparate im-

(Continued from previous page)

ployees for Promotion and Internal Placement. Id. at 336-62

The supplement required agencies to "give careful considera-

on *° winch of the available evaluation instruments "are rele-

van to the |ob and are sound and dependable measures of the

qualifications needed." Id. at 337. Tbe FPM went on to discuss

various evaluation instruments, including not only written and

other types of tests, hut also interviews and procedures for ap

praisals and assessment of potential. Id. at 340-42. With reeard

to all evaluation instruments, whether objective subjective o r

mixed the FPM required that an agency determine the effective

ness of the instrument through establishing its validity and dis

cussed and defined the three types of validity: content construct

and criterion related. Id at 342-43. Thus, the Civil Service Com

mission attempted to convince Congress that all of the methods

sed m lie federal service to select employees for jobs at all levels had been fully validated.

551

IH

pact scrutiny to suhjce.livo employment practices. And

“ in language that could Imrdly he more exp lic it ,” I1'tanks

v. liowman Transportation do., 424 II .S . at 7(il i i .2 I, Ihe

seclion-hy-Keclioii iiunlyscH suhmitled to both Houses “ con-

f ir in [ c«11 (Jongress’ resolve to accept prevailing judicial

in lerp ietations regarding the scope of T it le V I I , ” Loral

28 of Sheet Metal Workers’ International Association v.

E K O C , — U S . - , - , Kit; s .( !t . 2019, :i()47 (1980): “ In

any area where the new law does not address itse ll, or in

any areas where a specific contrary intention is not indi

cated, it was assumed that the present ease law as devel

oped by the courts would continue to govern the applica

bility and construction of Title I I I . ” 118 Cong. Hee. 7160,

7561 (11172) (emphasis added)."

Congressional awareness of cases applying disparate

impact analysis to subjective employment practices ex

tended at least to United States v. Sheet Metal I Yorkers

International Association, Local Union No. 2(1, 410 I1’.2d

122 (Hlh C ir . 1909), cited by the House Committee Report

as having “ contributed significantly to the tederal effort

to combat employment d iscrim ination,” I I .R . Rep. No. 228,

at 12 n.M , and Local f>.l of the International Association of

Heat <6 Frost Insulators v. i’oglcr, 407 l'\2d 1047 (fdli C ir.

1000), cited by both the House and Senate Committee Re

ports as support for the “ complex and pervasive” nature

of employment discrim ination, l l . i t . Rep. No. 228, at 8 n.2;

S . Rep. No. 415, at 5 n . l . ,w Sheet Metal Workers involved * 06

"Moreover, with respect to the new § 706(a), which gave

the EEOC more power to prevent persons from engaging in Ihe

employment practices made unlawful by §§ 703 and 704, see

06 Slat, at 104, the section by-section analyses expressly stated

tlipt "the unlawful practices encompassed by | §§ ] 703 and 704,

which were enumerated in 1964 in the original Act, anil as de

fined and expanr/ed by die courts remain in effect." 1 Ifl Cong

Rec. 7167, 7564 (1972) (emphasis added).

,9ln explaining the "complex and pervasive" nature of cm

ployment discrimination, the House and Senate Committee Re

ports also cited Cooper A Sobol, Seniority and Testing Under

(Continued on next page)

552

I!)

n union's practice of administering an examination, “ pnr-

lin lly subjective in nature ,” with “ no established | pass/

foil I standard .” 410 I<\2d at 120. The E ighth C ircu it

thought “ it . . . essential that journeym en’s examinations

be objective in nature [nnd| that they be designed to test

(he ability of Ihe applicant to do that work usually re

quired of a journeym an.” Id .

In reaching this conclusion, we do not necessarily

accept the government’s contention that [the test ad

ministrator |, as an individual, would, because of his

past participation in the exclusionary policies of the

Local, discriminate against Negroes in giving and

grading journeymen’s examinations. We are not here

concerned with the individual who gives and grades

the examination. )Ve arc concerned rather with the

system, the nature of the. examination, its objectivity

and its susceptibility to review.

Id. (emphasis added). In Vogler, the F ifth C ircu it also

focused on the effects of subjective crite ria . A d istrict

court order requiring a union to develop objective criteria

for membership “ based on industry need” was upheld be

cause subjective c r ite r ia —calling for applicants to obtain

recommendations from present members and to receive a

favorable vote of a m ajority of the membership—caused

the exclusion of blacks. Sec 407 l'\2d at 1049-50, 1054-55/° * 20

(Continued from previous page)

Fair Employment Laws: A General Appioadi to Objective

Criteria of Hiring and Promotion, 02 llarv. L. Rev. 1590 (1969)

Sec H R. Rep. No. 230 at 0 n.2; S. Rep. No. 415, at 15 n.1. That

article argued that " f i l f any subjective procedure lias a sys

tematic effect in disadvantaging, macks, Ihe employer should

be required to show the same justification as for a test or

other objective procedure." 02 llarv. L Rev. at 1677.

20rhe other courts that had considered the issue prior to

Congress' enactment of the amendments to Title VII agreed

that disparate impact analysis could be applied to subjective

practices. See United States v Dillon Supply Co., 429 F.2d OCX),

002, 004 (4th Cir. 1970) (district court committed reversible

error by failing to consider that " | p |radices, policies or pat-

(Continued on next page)

553

‘20

Inasmuch as the coulcmpnruncnuu ease law included

not only Griggs, hut also lower court decisions applying

$ 703(a) (2) disparate impact analysis to subjective prac

tices, Congress’ express intent in 1072 firmly compels that

application today.

IV. THE ADMINISTRATIVE INTERPRETATION OF

TITLE VII SUPPORTS THE APPLICATION OF

DISPARATE IMPACT ANALYSIS TO SUBJEC

TIVE EMPLOYMENT PRACTICES

Further support for the application of disparate im

pact analysis to subjective practice is found in the adminis

trative regulations concerning Title VII, which have con

sistently required the validation of all selection procedures.

The Uniform (luidelines on Employee Selection Proce

dures, 2!) C.F.R. ̂ I tit >7 (IttHti), “ based upon principles

which have been consistently upheld by the courts, the Con

gress, and the agencies," Id Fed. Reg. 2H2!)(J ( 11)7H), con

template application of disparate impact analysis to "any

selection procedure,” id. at § l(i()7.d, including "the full

range of assessment techniques from traditional paper and

pencil tests . . . through informal or casual interviews and

unscored application forms.” Id. at ^ IG()7.1(i(j. And as

the enforcing agencies’ "administrative interpretation of

(Continued from previous page)

terns, even though neuli.il on their face, may operate to seg

regate and classify on the basis of race at least as effectively

as overt racial discrimination" wheie "the government offered

proof of a decentralized system of hiring and assignment which

vested broad authority on the supervisors of largely segregated

departments and whir It bad no uniform or objective standards

for hiring or assignment"); United States v. /lef/i/e/iem Steel

Carp., 446 F.2d C>5>2, 655 (2d C'ir. 1971) (finding that "jobs were

made available to whites rather than to blacks" in part because

"ft]here were no fixed or reasonably objective standards anti

procedures for hiring"); Rowe v. General Motors Co., 457 F 2d

340, 355, 359 (5th Cir. 1972) (although employer liar) no "de

liberate purpose to maintain or continue practices which dis

criminate," court struck down "promotion/transfer procedures

which depend[erl] almost entirely upon the subjective evalua

tion and favorable recommendation of the immediate fore

man").

554

21

the Act,” 21 the (luidelines nre “ entitled to grent defer

ence.” Albemarle, 422 U.S. nl 431; Griggs, 401 U.S. nt

433-34; see also Local 28 of Sheet Metal 1I'orkers’ Interna

tional Association v. EEOC, — U.S. nt —, 10G S.Ct. at

3044-45 (Court’s interpretation of Title VII “ confirmed by

I In* contemporaneous interpretations of . . . both the Jus-

lire Department and Hit* FFCC, the two federal agencies

charged with enforefement responsibility.]” ); Local No.

!)8, International Association of Firefighters v. Citg of

Cleveland, — U.S. —, —, I0G S.Ct. 30G3, 3073 (108G) ( p i l

fered construction of Act supported by EFOC guidelines).

Compare General Electric Co. v. Gilbert, 429 U.S. 125,

141 4,r> (197(5) (EFOC regulations not followed because

(hey coni indicted agency’s earlier positions and were in

consistent with Congress’ plain intent); Espinoza v. Farah

Mfg.Co., 414 U.S. 80,93-94 (1973) (same).22

21 the Guidelines were jointly adopted in 1970 by the De

partment of Justice, as well as the FEOC, the Civil Service Com

mission, and the Department of Labor. 29 C.F.R. § 1007.1A.

Section 713(a) of Title VII authorizes the FEOC "to issue, amend

or rescind suitable procedural regulations to carry out the pro

visions of | the statute]." 42 U.S.C. § 20(X)e-12(a).

22According to the Uniform Guidelines, a selection pro

cedure having an adverse impact must be validated unless the

employer "choose! s| to utilize alternative selection procedures

in orcler to eliminate adverse impact." 29 C.F.R. § 1607.6A.

No selection procedures are exempted from Ibis requirement.

The government, however, points out that " 11 ]here are circum

stances in which a user cannot or need not utilize the valida

tion techniques contemplated by these guidelines," id. at

§ 1607.6R, and asserts that one such circumstance is the use of

"informal or unscored selection procedureTs]." Id. at §1607.611

(1). The government then concludes that an employer need only

"justify libel continued use of |such| procedure|s| in accord

with Federal law," id., and that the articulation of a legitimate,

nondisc riminatory reason suffices as the requisite justification.

Sec brief for the United Slates as Amicus Curiae at 19 20. This

argument is a distortion of the Guidelines. Tirst, the Guidelines

also include "formal and scored procedures" as circumstances

in which an employer cannot or need not utilize validation

techniques. See id at § 1607.6B(2). Second, the government

(Continued on next page)

555

22

In requiring nppliealon of the disparate impact analy

tes to nil selection procedures, the Guidelines track the

now superseded administrative regulations upon which

this Court relied in its affirmation of the disparate im

pact test in Griggs. The IOEOO’s 15)66 and 15)70 Guide

lines,21 which the Court treated “ as | having] express|ed| * 3

(Continued fiom previous page)

has neglected to mention the tiist two clauses of § 1f>07.6li(1),

which provide that an employer using an informal or unscored

procedure should (1) "eliminate the adverse impact," or (2)

"modify the procedure to one which is a formal, scored or

quantified measure." finally, the government's "belief" that

the use of a selection procedure having a disparate impact may

be justified by the mere articulation of a legitimate, nondiscrim-

inatory reason is undermined by the questions and answers

provided to explain the Guidelines:

36. How can users justify continued use of a pro

cedure; on a basis other than validity?

A. Normally, the method of justifying selection pro

cedures with an adverse impart and the method to which

the Guidelines are primarily addressed, is validation. The

method of justification of a procedure by means other than

validity is one to which the; Guidelines are not addressed.

See Section 60. In Griggs v Duke rower Co., 401 U S. 424,

3 FIT Cases 175, the* Supreme Court indicated that the bur

den on the user was a heavy one, but that the selection

procedure could be used if there was a "business neces

sity" for its continued use; therefore, the Federal agencies

will consider evidence that a selection procedure is neces

sary for the safe and efficient operation of a business to

justify continued use of a selec lion procedure.

44 Fed. Reg. 11996, 12002 (1979). Cl Comment, Applying Dis

parate Impact Theory to Subjective Employee Selection Pro

cedures, 20 toy. L.A.L. Rev 375, .309 (1907) ("Flow to 'other

wise justify' . . . selection procedures remains an open ques

tion."). The government's proposed standard of justification

would flout, rather than "accord" with, the federal law as an

nounced in Griggs.

2JThe Guidelines on Employment Testing Procedures, issued

in 1966, were not published in the Federal Register. They were

superseded in 1970 by the Guidelines on Employee Selection

Procedures, published at 35 Fed Reg. 12333 (1970) (codified

at 29 C.F.R. § 1607, superseded in 1978).

556

i 23

tin* will of Congress,” Griggs, 401 IJ.S. at 434, interpreted

Title VII to prohibit the use of any “ test” that was dis

criminatory in operation and for which job iclatedness

could not be; established. 35 Keel. Iteg. at 12334 (§ 1607.3).

They defined the term “ test” broadly, including within

its scope such subjective practices as “ scored interviews”

and “ interviewers’ rating scales.” Id. at 12334 ($ 1607.2).

Klsewhere, the KKOU Guidelines recognized that “ |s]elec-

tion techniques other Ilian tests,” such as unscored “ casual

interviews” and “ application forms,” might also “ hpve

I lie* effect of discriminating against minority groups.” Id.

at 12336 1607.13). Under those circumstances, the em

ployer was required to validate the selection lcclmiquc(s)

at issue or to eliminate the disparate impact. ld.2A

V. APPLICATION OF THE DISPARATE IMPACT

ANALYSIS TO SUBJECTIVE PRACTICES FUR

THERS THE PRIMARY PROPHYLACTIC PUR

POSE OF TITLE VII

The application of $ 70.3(a)(2) to subjective practices

is entirely consistent with T itle V I I ’s central aim of “ elim

inating the effects of discrim ination in the workplace.”

Johnson v. Transportation Agency, Santa Clam County,

Calif., 11.8. — , -, 107 K.G’i. 1412, 1451 (19H7); see. also

Teal, 457 IJ.S . at 44!) ( “ Congress’ prim ary purpose was

the prophylactic one of achieving equality of employment

‘ opportunities’ and removing ‘ h a rr ie rs ’ to such equal

it y .” ). It is also consistent with the statute’s goal of en

t it le Department of Labor, in its interpretation of Execu

tive Order 11246, 33 Ted. Reg. 14392 (I960) (Employment Tests

by Contractors and Subcontractors: Validation), similarly con

templated the validation of "any . . . performance measure used

to judge qualifications for hire, transfer or promotion," includ

ing measures of "intelligence," "ability," "aptitudes," "knowl

edge and proficiency," as well as measures of "personality or

temperament," id. at 14393 (§9). See id at 14392 (§ 1(g)). Not

ing that " | s |election techniques other than tests may also be im

properly used so as to have the effor t of discriminating," the

Department required that such techniques as "unscored inter

views" and "unscored application forms" also be validated or

adjusted to eliminate any disparate impact. Id. at 14393 (§ 10).

557

24

conniving employers to engage in voluntary self examina-

Iion of their employment practices, and will not unneces

sarily or unreasonably diminish management preroga

tives.

A. Title VII “ Prohibits All Pactices in Whatever

Form Which Create Inequality in Employment

Opportunity”

While § 7<).'t(n) (2 ) 's broad proscription of discrimina

tion in employment extends to all “ practices, procedures,

or I (is t s neutral on their face, and even ventral in terms

of intent . . . Hint operate as ‘built in headwinds’ for mi

nority groups and are unrelated to measuring job capa

bility,’’ Griggs, 40! IJ.S. at 4:t(), 422 (emphasis added),

the government would have plaintiffs prove intent in all

challenges to subjective employment practices.

However, irrespective of an employer’s good inten

tions, the use of subjective selection criteria may unfairly

restrict employment opportunities for minorities and wom

en. Subjective criteria leave substantial room for deeply

ingrained, unconscious biases. As one commentator has

written: “ A supervisor | who is) judging a subordinate

for promotion potential tends to look for traits [in the

subordinate| which the supervisor feels he himself has. It

is, of course, much easier for a Caucasian male to find such

traits in other Caucasia........ . than in minorities and

women.” Stacy, Subjective (/Vitoria in Employment De

cisions Under Title VII, 1(1 (la. I,. Rev. 7.'(7, 711!) (1970).

See also It. IMunihley, Recruitme.nt and Selection 145-4(5

(1 !)B 1) ( When a candidate’s background and personality

“ appear to have been similar to his, the interviewer is

presupposed to be biased in favour of him......... lodgment

can be warped in this way without the interviewer being

conscious of it.” ).25 Moreover, the criteria themselves may

JS5ee/ eg., Wilmore v. City oI Wilmington, 699 F.2d (>f>7,

673-74 (3d Cir. 19(13) (exclusion of blacks from adminislralive

jobs a result of both conscious and unconscious biases); Chance

v. Bil. of Examiners, 330 F.Supp. 203, 223 (S.D.N.V. 1971) (while

interviewers may have unconsciously discriminated against

blacks and llispanics), al'<l 4r>() I 2d 1167 (2d Cir. 1972).

558

25

be “ unrelated to measuring job capability.” Griggs, 401

II.M. 4.32; see 1). Baldus & J. Cole, Statistical Proof of Dis

crimination §1.2:1, nt 27 (11)80 Supp.) (“ (Tjlie defendant

I may bej unbiased in evaluating the candidates and . .

the disparate impact [may be] caused by differences in

characteristics of the candidates which, if measured ob

ject ividy, would surely trigger u demand for proof of job

telaledness.” ).26 The Court has made precisely this point

with respect to subjective performance appraisnla put

forth by the employer in Albemarle in an attempt to vali

date the objective test at issue there. The Court rejected

the proffered correlation, however, because the “ super

visors |had been | asked to rank employees by a ‘standard’

that was extremely vague and fatally open to divergent

interpretations.” 422 U.S. at 4.T1. The Court had no way

of knowing “ whether the criteria actually considered were

sufficiently related to the Company’s legitimate interest

in job specific ability to justify [the] testing system.”

Id. (emphasis in original).17 Thus, the Court was rightly

concerned that the subjective performance appraisals may

not have measured job related skills.

In order to achieve Congress’ primary purpose of

“ achieving equality of employment 'opportunities’ and

removing ‘barriers’ to such equality,” Teal, 457 U.S. at

449, the disparate impact analysis must be applied to all

employment practices, both objective and subjective.

265ee, e g., Hawkins v. Bounds, 752 F.2d 500, 504 (10th Cir

1905) ("The record in Ibis case contains no evidence . . that

the practice of totally discretionary detailing or its use in the

promotion procedure [was] required by business necessity")-

Segar v. Smith, 730 F.2d 1249, 1200 (D C. Cir. 1904) (defendant

never even attempted to showing job-relatednoss of subjective

experience requirement), cert, denied, 471 U.S 1115 (1905)-

Greenspan v Automobile Club, 495 F.Supp. 1021, 1033 (F (V

Mich. 1900) (defendant failed to base evaluations on job analy-

Ct. B Schlci & P. Grossman, Employment Discrimination

■'w 203 (2d ed. 1903) (. . |T|be evaluative devise (should have!

fixed content and cnllfl for discrete judgments ").

559

B. Title VII Requires That Employers “ Self-Exam-

ine and Self Evaluate Their Employment Prac

tices"

1 lie government’s apparent concern for management

prerogatives cannot obscure the fact Hint the exclusion of

subjective criteria from disparate impact analysis would

allow and even encourage employers to avoid the intro

spective assessment of their employment practices as eon

templated by Title VII. Provided a convenient sanctuary

in subjective criteria, employers would be loathe " Mo self-

examine and to sell evaluate their employment practices

and to endeavor to eliminate . . . the last vestiges of an

unfortunate and ignominious page in this country’s his

tory.’ ’’ Albemarle, 422 U.S. at 418 (quoting United States

v. N.Ij. Industries, 47!) l-’.2d .454, ;t7!) (8th (hr. 197.1)). Cf.

United Steelworkers v. IVebcr, 448 U.S. at 204 (Title VII

“ intended as a spur or catalyst" for employer efforts to

eliminate effects ol discrimination).

I lather than encourage self examination, the govern

nient’s proposed exemption for subjective practices would

hkely encourage blind adherence to those practices. See

(\ri ' f f in v: Carlin, 7f>f> l-’.2d IT.If,, 1525 (11th Cir. 1085)

( I'jxclusion of . . . subjective practices from the reach

ot Hu, disparate impact model of analysis is hkely to en

courage employers to use subjective, rather than objec

tive, selection criteria.’’); 1). Baldus & J. Cole, Statistical

I ' o o f of Discrimination § 1.28, at 27 (I08G Supp.) ("ex

clusion ol subjective criteria from review under the dispa

rate impact model may encourage employers to rely less

on objective criteria and more on general standards")

"•Iced, to avoid the potential for disparate impact lia-

, . e,,1l'b)yers would be inclined simply to consider oh

jective criteria, such as a diploma requirement, within the

context of a subjective interview. Yet " | i j | could not

l-ave been the intent of Congress to provide employers

with an incentive to use such devices rather than validated

objective criteria." (h iff in v. Carlin, 755 l-’.2d at 1525-

see also Atonio v. Wards Cove Sacking Co., 810 I<’.2d at

20

560

1

1485 ( " I t would subvert the purpose of Title VII to create

an incentive to abandon efforts to validate objective cri

teria in favor of purely discretionary hiring methods.” ).21 * * * * * * *

Aloreover, if any distinction were to be drawn between

subjective and objective employment practices, one would

expect the courts to scrutinize the former more carefully:

Subjective employment practices are more susceptible to

alms,, Ilian their objective counterparts. As (he Ninth

Circuit noted in Nanly v. Harrows Co., (ifi() l-'.2d 1827 1884’

(!Hh Cir. 1!)8I) (footnote omitted): “ Subjective job cri

teria present potential for serious abuse and should be

viewed with much skepticism. Use of subjective job cri

teria not only has, in many instances, a disparate impact

on minorities, but also provides u convenient pretext for

discriminatory practices."29

The government suggests that application of the dis

parate impact analysis to subjective criteria would impose

“ The government asserts that the application of disparate

anpacl analysis to subjective criteria will force employers either

to abandon such criteria or to eliminate statistical disparities

trough the adoption of quotas—because "subjective selection

<1 wices . . m a y not be susceptible to validation or other such

objective substantiation." Uriel for the United States as Amicus

C-uriae at 15. As noted infra at 20-10, the premise for such a,, « !

serlion is unfounded: subjective criteria arc in fad susceptible

vahdation techniques. The government makes no mention

of the fact that the failure to apply disparate impact analysis

to subjective criteria will cause employers to abandon objective

cr.tena for reasons unrelated to either the promotion of business

necessity or the enhancement of equal opportunity in emjdoj

nSee a/so Harnett v. W.T. Grant Co , 510 F.2d 541 sqn fail,

Cir. 1975) ("Nonobjective hiring standards are always sus|>ect

because of heir capacity for masking racial I bias ) .") Rogers v

Internatuuial I'a,ter ( o , 510 f.2d 1140, 1145 (Oil, Cir ) ("Greater

possibilities for abuse . aie mbeient in subjective definitions

of employment selection and promotion criteria ") vacated on

other grounds 421 U.S. 000 (1-175): Mailer v. United States Steel

Corn., 509 F.2d 921, 920 (10th Cir.) ("personal and subjective

T tf T ' r r ; ,IS(cri' " i"'l li ,,n " )' « v l. denied, 421

bon § j 2 , S ' t nnr c ei ^ 'C tica l Proof of Discrimination 9 1.21, at 27 (1900 Supp.) (subjective criteria are "more

susceptible to abuse"). re

27

561

28

an insuperable bunion on employers because of the un

feasibility of validating suoli criteria. See Brief for the

llnilod States as Amicus Curiae at 14-15. That suggestion

is without merit. The industrial psychology profession uni

versally recognizes that “ [ijntei viewers ure subject to (lie

same standards of reliability and validity as apply to tests.”

W. Casein, Applied Psychology in Personnel Mono,,mient

.(1 (2d ed. 1982).30 All selection procedures, whether oh

joctive or subjective, may he demonstrated to he job-re

lated through acceptable validation procedures.11

! ° 7 he I industrial psychology) profession has taken the

stand that al selection systems, including subjective ones, can

and indeed should he validated. The literature contains numer

ous descriptions of validity studies of the most commonly used

subjective processes, such as interviews, the evaluation of bio-

grajnucal data, and assessment center techniques.” Bartholot

V" ,! ,I,S in 1 l>la«s , 95 //arv. L. Rev. J I7 , 900 (IJ02). See a/so Arvey & Campion, The Employment

Interview: A Summary and Review of Recent Research 35 Per

sonnel Psychology 20I (1902) ("Industrial and organizational

(psychologists have been studying the employment interview

tor more than 60 years in an effort to determine the reliability

and validity of judgment based on the assessment device and

also to discover the various |>sychological variables which in

fluence these judgments.” ); W. Cascio, Applied Psychology in

lersonnel Management I t (2d ed. 1902) ("| R leliability and

validity analyses |of interviews! can easily he made by accu

rately maintaining . records fof information gathered, action

taken, and jrredn lions of future |>erformance] .” ).

"See generally Doverspike, Harrell & Alexander, The Feasi-

hdity of Trad.t'onal Valbh.tion Procedures for Demonstrating

Job-KelaliMlness, 9 Law & Psyi hology Rev. 35 (1905). The

Standards for Educational and Psychological Testinn (1905)

jointly issued by the American Psychological Association, the

American Education Rescan h Association and the National

Council on Measurements in Education, slate that validity is the

most important consideration in evaluating tests, id. at 9 ("Tech

nical Standards for Test Construction and Evaluation") and

broadly define tests to indude all "evaluative devices" as well

as standardized ability instruments. Id al 3. See also Ct.ion,

Recruiting, Seler lion and lob Placement, in Handbook oI In

lo n iw m c if/ °.7?dn,z‘1" f>n<i/ Psychology 799 (M. Diinnetle ed 1)03) ( ISIjrecific items of information drawn from interviews

and | global judgments made by interviewers and others must

be considered as "tests").

562

29

That tho Riibjcctive elements of a promotion or hir

ing system can he validated is further evidenced by the

government’s own experience. Tho standard process for

selecting federal employees for competitive positions con-

fnins a number of subjective elements, including tho use of

pei foi mance evaluations, interivews, and recommenda

tions.32 Nevertheless, (he Office of Personnel Manage

ment requires, as did flic Civil Service Commission hefoi’9

it, see supra at 16, that federal agencies, where feasible,

validate all selection procedures and standards—including

subjective criterin-according to the Uniform Guidelines

on I'iiiqiloyee Selection Procedures. See Federal Person

nel Manual, Chap. 335, Supplement 335-1, suhehapter

3 4(a) (1980). In those few instances where strict valida

tion is not possible, the procedures and standards still must

he shown to he job related. Id.

Amici have been involved in a number of cases under

Title VII against a variety of federal agencies. In several

instances, such agencies have validated their entire selec

tion procedures, including those that involve subjective

elements. For exumple, in Harrison v. Lewis, 559 F.Supp.

943 (D.I).C. 1983), the district court, nfter finding that

blacks had suffered discrimination in selections for pro

fessional and adminisfrelive positions under flic disparate

impact theory, ordered the agency to revise and validate all

elements of its selection process pursuant to the Uniform

Guidelines, including subjective rating, ranking, and selec

tion procedures. See 559 F.Supp. at 953. Subsequently,

the agency commissioned a study by an industrial psy

chology firm and has reported to (lie court that they had

successfully validated their procedures as ordered. In

short, the actual and practical experience of the country’s

largest single employer, the United States Government,

sharply contradicts the contentious advanced by Ihe gov-

J25ee fi. Schlei and P. Grossman, Employment Discrimination

law 1107 n.5 (2d ed. 1903), lor a summary description of the

process.

563

no

~ ll0rc H,al s,,l‘j aclivo »"> '.nptmail.ln

‘ - ' — ( ) -------- - .

CONCLUSION

Mir the reasons nl.ovo, if it is appropriate to decide

tho merits, the judgment of the Fifth (Jirc.it should |)0

reversed. 1,0

DATKI); September I t, 10H7

Respectfully sii limit ted,

H i m , L a nn L e e *

►S'l'El’IlEN M. CoTI.ER

Center for Law in the

Ciihlic Interest

•Ini,m s L e V o n n e C mamuerh

R o NAIJ) L. I'h.MS

O i i ari .es S tki i i e n R auston

NAAFI* Legal Defense and

I'idnralionnl Fund, Ine.

A ntonia H er nand ez

I'<. R i chard L arson

doHE RoilERTO dl/AREZ

Mexican American Legal Defense

nnd Fdncalionul Fund

doAN M. O raee

1‘atricia A. S iiiu

Fmploynient Law Center

# Counsel for Amici

Counsel of Record

564

* * * * * * * *

SUPREH

FO

ON WR1

STATES CO

STATE OF

RIGHTS; Tl

HAWAII; TI

MASSACHU!

TION; THE

OHIO AND

STATE OF

TIONS; TH

WYOMING /

EMPLOYMEf

ON THE Bl

ELAINE RC

Legal In ter

565