Riddick v The School Board of the City of Norfolk Writ of Certiorari

Public Court Documents

October 1, 1985

76 pages

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Riddick v The School Board of the City of Norfolk Writ of Certiorari, 1985. 719c1174-c29a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c2ca57d2-1f66-4082-a1d9-6838bded5545/riddick-v-the-school-board-of-the-city-of-norfolk-writ-of-certiorari. Accessed February 24, 2026.

Copied!

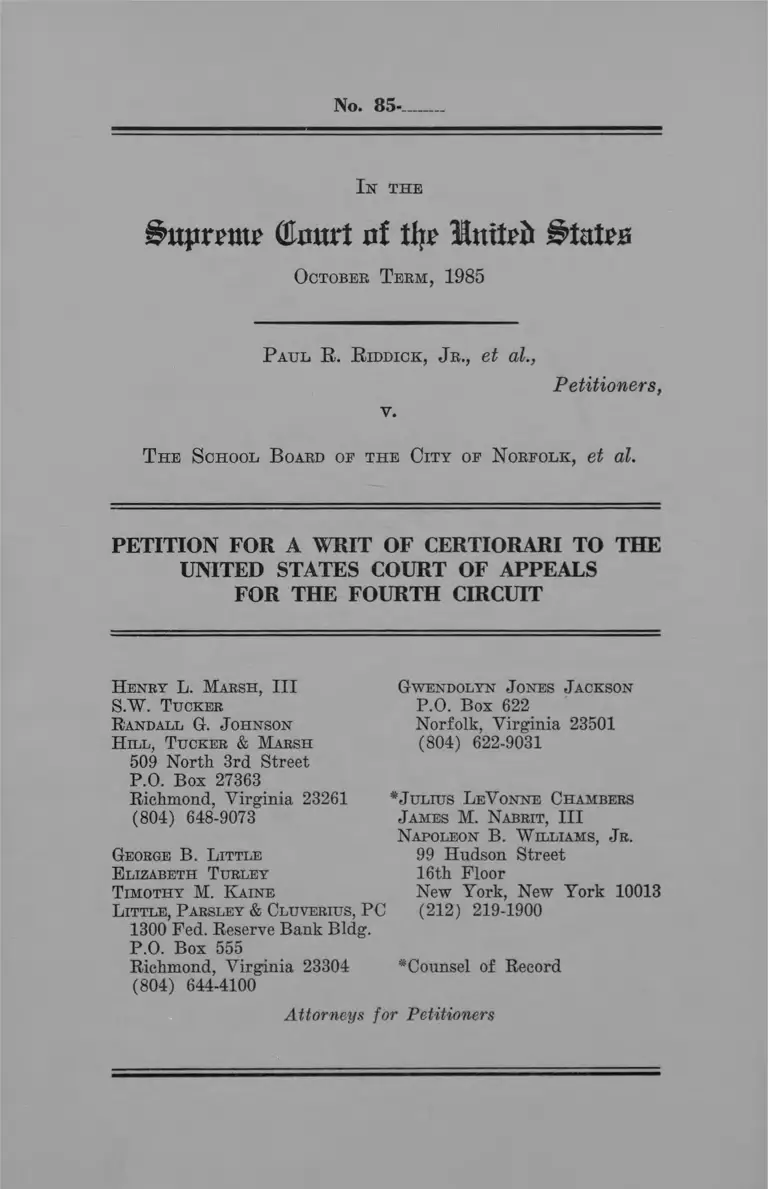

No. 85-

I n the

i>uprrmr (tort of % Imfrfu ^tatro

October T erm, 1985

P aul R. R iddick, Jr ., et al.,

v.

Petitioners,

T he School B oard of the City of Norfolk, et al.

PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

Henry L. Marsh, III

S.W. Tucker

Randall G. Johnson

H ill, Tucker & Marsh

509 North 3rd Street

P.O. Box 27363

Richmond, Virginia 23261

(804) 648-9073

George B. L ittle

Elizabeth Turley

Timothy M. K aine

Little, Parsley & Cluverius, PC

1300 Fed. Reserve Bank Bldg.

P.O. Box 555

Richmond, Virginia 23304

(804) 644-4100

Gwendolyn Jones Jackson

P.O. Box 622

Norfolk, Virginia 23501

(804) 622-9031

*Julius LeV onne Chambers

James M. Nabrit, III

Napoleon B. W illiams, Jr.

99 Hudson Street

16th Floor

New York, New York 10013

(212) 219-1900

* Counsel of Record

Attorneys for Petitioners

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

I. Whether a public school system that

has been declared "unitary" only after

eliminating all one-race schools through a

desegregation plan conforming to Swann v.

Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

401 U.S. 1 (1971), will violate its

constitutional duty to eradicate racial

segregation as announced in Brown v. Board

of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954), if it

then dismantles the desegregation plan

that made it "unitary" and assigns almost

40% of black elementary pupils to ten

all-black schools which existed prior to

the unitary plan?

i

II. Does the proposed plan violate the

Fourteenth Amendment on this record where:

(a) It is undisputed that the plan

will have a substantial segregative effect

on thousands of pupils who now attend in

tegrated schools, by placing two-thirds of

white elementary pupils in 14 majority

white schools and 39% of blacks in ten 97

to 100% black schools; and

(b) The school board adopted the

plan to serve the eiplictly articulated

racial purpose of increasing the number of

white pupils attending the Norfolk public

schools, and this is to be achieved by

minimizing the number of blacks attending

schools with whites by creating 14 schools

having over 50% white pupils in accord

ii

with the board's public opinion poll show

ing that white parents (but not black par

ents) opposed sending their children to

schools where they were less than a major

ity?

LIST OF PARTIES

1. The named plaintiffs in this cer

tified class action are listed below:

Paul R. Riddick, Jr. and Phelicia

Riddick, infants by Paul R. Riddick,

their father and next friend;

Cynthia C. Ferebee, Johnny Ferebee,

Gary Ferebee, and Wilbert Ferebee,

infants, by Rev. Luther M. Ferebee,

their father and next friend;

Anita Fleming, infant, by Blanche

Fleming, her mother and next friend;

Darrell McDonald and Carolyn Mc

Donald, infants, by Ramion McDonald,

Sr., their father and next friend;

Eric E. Nixon and James L. Nixon, in

fants, by Patricia Nixon, their

mother and next friend;

- iii-

Johnny Owens, Trent Owens, Myron

Owens, Shawn Owens, and Antonio

Owens, infants by Annette Owens,

their mother and next friend;

Paul R. Riddick, Rev. Luther M.

Ferebee, Blanche Fleming, Ramion

McDonald, Sr., Patricia Nixon, and

Annette Owens.

The district court certified a plain

tiff class consisting of "all present and

future black schoolchildren in the public

school system of the City of Norfolk, Vir

ginia" pursuant to Rules 23(a)(1) and 23

(a)(2) Fed. R. Civ. P.

2. The defendants are the School

Board of the City of Norfolk, and the mem

bers of the school board sued in their of

ficial capacity. The individual defen

dants are Thomas G. Johnson, Jr., Dr. John

H. Foster, Dr. Lucy R. Wilson, Jean C.

Bruce, Cynthia A. Heide, Robert L. Hicks,

and Hortense R. Wells. Mr. G. Wesley

Hardy replaced Dr. Foster on the Board.

iv -

QUESTIONS PRESENTED ............. i

LIST OF PARTIES ........... ...... iii

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ............ vii

OPINIONS ......................... 2

JURISDICTION ..................... 2

STATUTES AND CONSTITUTIONAL

PROVISIONS INVOLVED ........ 3

STATEMENT OF THE CASE ........... 4

Introduction ............... 4

The Beckett/Brewer Case,

1956-1975 ............. 8

The system of segregation prior

to the 1971 P l a n . 13

The 1971 Desegregation Plan.. 15

The Proposed Plan .......... 17

The District Court Decision.. 26

The Court of Appeals

Decision .............. 30

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

- v -

Page

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT .... 33

I. THE CASE PRESENTS QUES

TIONS OF OBVIOUS NATIONAL

IMPORTANCE WHICH ARE

BOUND TO ARISE IN EVERY

PAST, PRESENT OR FUTURE

SCHOOL DESEGREGATION

CASE ...................... 33

II. THE DECISIONS BELOW ARE

INCONSISTENT WITH THE

PRINCIPLES OF SWANN V.

BOARD OF EDUCATION AND

OTHER DECISIONS BY THIS

COURT ..................... 41

III. THE DECISIONS BELOW CON

FLICT WITH THE PRINCIPLES

OF THIS COURT'S KEYES, DAYTON,

AND COLUMBUS DECISIONS DE

FINING UNCONSTITUTIONAL SEG

REGATIVE ACTIONS, AND WITH

SCOTLAND NECK AND OTHER CASES

REJECTING‘“WHITE FLIGHT" AND

OPPOSITION TO DESEGREGATION

AS A JUSTIFICATION FOR

SEGREGATION .............. 51

CONCLUSION ....................... 58

vi

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Cases Page

Arlington Heights v. Metro.

Housing Corp., 429 U.S. 252

(1977) ...................... 52

Beckett v. School Board of the

City of Norfolk, 2 Race

Relations Law Reporter 337

(Feb. 12, 1957) ............ 5

Beckett v. School Board of the

City of Norfolk, 3 Race

Relations Law Reporter

942-964 (1958) ............. 5

Beckett v. School Board of the

City of Norfolk, 3 Race

Relations Law Reporter

1155 (E.D. Va. 1958);

affirmed 260 F.2d 14 (4th

Cir. 1958) ................. 5,9

Beckett v. School Board of the

City of Norfolk, 5 Race

Relations L. Rep. 407

(Oct. 23, 1959) ............ 6

Beckett v. School Board of the

City of Norfolk, 9 Race

Relations Law Reporter

1315 (E.D. Va. 1964);

vacated and remanded

sub, nonu ......... ......... 6,9

- vii -

Page

Beckett v. School Board of the

City of Norfolk, 11 Race

Relations Law Reporter

218 (E.D. Va. 1965) ........ 6

Beckett v. School Board of the

City of Norfolk, 11 Race

Relations Law Reporter

1273 (E.D. va. 1966) .......... 6

Beckett v. School Board of City

of Norfolk, 148 P.Supp. 430

(E.D. Va.), affirmed 246

F.2d 325 (4th Ci'r.)' c^rt.

den. 355 U.S. 855 (1957) _____ 5,8

Beckett v. School Board of the

City of Norfolk, 181

F.Supp. 870 (E.D. Va.

1959) ....................... 6

Beckett v. School Board of the

City of Norfolk, 185 F.Supp.

459 ( 1959) ................ 6

Beckett v. School Board of the

City of Norfolk, 269 F.Supp.

118 (E.D. Va. 1967); supple

mental memorandum 12 Race

Rel. L. Rep. 867 (June 2,

1967) 6

viii

Page

Beckett v. School Board of the

City of Norfolk, 302 F.Supp.

18 (E.D. Va. 1969) ......... 6

Beckett v. School Board of the

City of Norfolk, 308 F.Supp.

1274 (E.D. Va. 1969) ....... 6,10

Brewer v. School Board of the

City of Norfolk, 349 F.2d

414 (4th Cir. 1965) ........ 6,10

Brewer v. School Board of the

City of Norfolk, 397 F.2d

37 (4th Cir. 1969) ......... 6,10

Brewer v. School Board of the

City of Norfolk, 434 F.2d

408 (4th Cir. 1970) cert.

den. 399 O.S. 929 (19757 ___ 6,11,13

Brewer v. School Board of City

of Norfolk, 456 F.2d 943

(4th Cir.), cert, den. 406

O.S. 933 (1972)' ....... 7,12

Brewer v. School Board of the

City of Norfolk, 500 F.2d

1129 (4th Cir. 1974) ....... 7

ix

Page

Brewer, sub, nom. Adams v. School

District No. 5, Orangeburg

Co. S. C., 444 F.2d 99

(4th Cir.) en banc; cert. den.

404 O.S. 912 (1971) ........ 7,11

Brown v. Board of Education, 347

O.S. 483 (1954) ........ 8,34,37,57

Columbus Board of Education v.

Penick, 443 O.S. 449

(1979) ..................... 31,35,49

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 O.S. 1

(1958) ...................... 57

Davis v. Board of School Com

missioners of Mobile County,

402 O.S. 33 ( 1971 ) ......... 11,35

Dayton Board of Education v.

Brinkman, 433 O.S. 406

(1977) (Dayton I) .......... 49

Dayton Board of Education v.

Brinkman, 443 O.S. 526

(1979) (Dayton II) ..... 31,35,49,50

Dowell v. Board of Education

of Oklahoma City Public

Schools, 606 F.Supp. 1548

(W.D. Okla. 1985) .......... 38

x -

Duckworth v. James, 267 F.2d

224 (4th Cir. 1959) ........ 5,9

Farley v. Turner, 281 F.2d 131

(4th Cir. 1960) ............ 6,9

Gomillion v. Lightfoot, 364

U.S. 339 (1960) ............ 52

Green v. County School Board,

391 U.S. 430 (1968) ...... 27,32,35

Harrison v. Day, 200 Va. 439,

106 S.E.2d 636 (1959) ...... 5

Hill v. School Board of the City

of Norfolk, 282 F.2d 473

(4th Cir. 1960) ............ 6

James v. Almond, 170 F.Supp. 331

(E.D. Va. 1959) ............ 5,9

James v. Duckworth, 170 F.Supp.

342 (E.D. Va. 1959); affirmed

267 F.2d 224 (4th Cir.

1959) ....................... 5

Keyes v. School District No. 1,

413 U.S. 189 (1973) ___ 27,32,44,56

Monroe v. Board of Commissioners,

391 U.S. 450 (1968) .. 32,35,40,53,57

Spangler v. Pasadena, 611 F.2d

1239 (9th Cir. 1979) ....... 31

Page

- xi

Page

Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg

Board of Education, 402 U.S.

1 (1971) .................... passim

United States v. Scotland Neck

Board of Education, 407

U.S. 484 ( 1972) ............ 28,32,

35,53,54,57

Yick Wo v. Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356

(1886) ...................... 52

Statutes and Constitutional

Provision

Fourteenth Amendment to the

Constitution of the

United States .............. 3

Statutes

28 U.S.C. Section 1254(1) ....... 3

28 U.S.C. Section 1331 .......... 2

28 U.S.C. Section 1343(3) ....... 2

28 U.S.C. Section 1343(4) ....... 2

42 U.S.C. Section 1981 ........... 2

42 U.S.C. Section 1983 .......... 2

42 U.S.C. Section 1988 .......... 2

xii

Page

Other Authorities

Department of Justice Press

Release dated February 18,

1986 ........................ 38

- xiii

No. 85- ____

IN THE

SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES

October Term, 1985

PAUL R. RIDDICK, JR. et al,

Petitioners,

v.

THE SCHOOL BOARD OF THE

CITY OF NORFOLK, et al.

TOPETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

The petitioners Paul R. Riddick, Jr.

et al. respectfully pray that a writ of

certiorari issue to review the judgment

and opinion of the United States Court of

2

Appeals for the Fourth Circuit, entered in

the above-entitled proceeding on February

6, 1986.

OPINIONS BELOW

The opinion of the Court of Appeals

for the Fourth Circuit is reported at 784

F.2d 521, and is reprinted in the appendix

hereto, p. 1A, infra.

The Memorandum Opinion of the United

States District Court for the Eastern

District of Virginia (MacKENZIE, C.J.),

dated July 9, 1984 is reported at 627

F.Supp. 814 (E.D. Va. 1984). See appendix

p. 99A, infra.

JURISDICTION

Petitioners brought suit in the

Eastern District of Virginia invoking

federal jurisdiction under 42 U.S.C.

sections 1981, 1983 and 1988, and under 28

U.S.C. sections 1331, 1343(3) and 1343(4).

3

On July 9, 1984, after a trial on the

merits, the Court denied petitioners'

prayer for injunctive relief.

On petitioners' appeal, the Fourth

Circuit on February 6, 1986 entered a

judgment and opinion affirming the

District Court. A timely petition for

rehearing and suggestion for rehearing en

banc was denied March 19, 1986. App.

158A, infra.

The jurisdiction of this Court to

review the judgment of the Fourth Circuit

is invoked under 28 U.S.C. section

1254(1).

STATUTES AND CONSTITUTIONAL

PROVISIONS INVOLVED

This case involves the equal protec

tion clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to

the Constitution of the United States.

4

STATEMENT OP THE CASE

Introduction

This class action was filed in May

1983 by a group of black parents seeking

an injunction to prevent the Norfolk

School Board from dismantling a desegre

gation plan for elementary pupils and

changing ten currently integrated schools

into one-race schools which will range

from 97 to 100% black and average 99%

black. Both courts below have approved

the proposed plan, which would assign 39

percent of Norfolk's black elementary

1

students to the ten all-black schools.

The same ten schools were all-black in

1969 prior to the final desegregation plan

ordered by the courts in a prior case in

̂ About 59% of the pupils are black. It was

estimated that 4738 black and 54 white

children would attend the 10 black

schools. The remaining 26 elementary

schools would have 8403 white and 7416

black pupils.

5

1971. Thus, after 15 years of desegrega

tion, Norfolk's schools will again become

substantially segregated unless this Court

intervenes.

In a historic prior lawsuit which

lasted 19 years black parents successfully

overcame Virginia’s official policy of

"massive resistance" and desegregated the

2

public schools of Norfolk, Virginia. That

Opinions in the earlier case and

related cases were:

1. Beckett v. School Board of City

of Norfolk, 148 F.Supp. 430 (E.D. Va.),

affirmed~246 F.2d 325 (4th Cir.) cert.

den. 355 U.S. 855 (1957).

2. Beckett v. School Board of the

City of Norfolk, 2"Race Relations Law

Reporter 337 (Feb. 12, 1957).

3. Beckett v. School Board of the

City of Norfolk, 3 Race Relations Law

Reporter 942-964 (1958).

4. Beckett v. School Board of the

City of Norfolk, 3 Race Relations Law

Reporter 1155 (E.D. Va. 1958); affirmed

260 F.2d 18 (4th Cir. 1958).

5. James v. Almond, 170 F.Supp.

331 (E.D.Va. 1959); 3-Judge Court.

6. Harrison v. Day, 200 Va. 439,

106 S.E.2d 636 (1959).

7. James v. Duckworth, 170 F.Supp.

342 (E.D. Va. 1959); affirmed 267 F.2d

224 (4th Cir. 1959).

litigation required ten appeals to the

8. Beckett v. School Board of the

City of Norfolk, 181 F.Supp. 870 (E.D.

Va. 1959). Beckett v. School Board of

the City of Norfolk, 5 Race Rel. L. Rep.

407 (Oct.23, 1959).

9. Beckett v. School Board of the

City of Norfolk, 185 F.Supp." 459 (1959);

affirmed sub, nom. Farley v. Turner,

281 F.2d 131 (4th Cir. 1960).

10. Hill v. School Board of City

of Norfolk;;; 282" F.2d 473 (4 th Cir.

T § 60" ) .

11 • Beckett v. School Board of the

City of Norfolk, 9 Race Relations Law

Reporter 1315 (E.D.Va. 1964); vacated

and remanded sub. nom. Brewer v.

School Board of the City of Norfolk, 349

F.2d 414 (4th Cir. 1965).

12. Beckett v. School Board of the

City of Norfolk, 11 Race Relations Law

Reporter 218 (E.D. Va. 1965).

13. Beckett v. School Board of the

City of Norfolk, 11 Race Relations Law

Reporter 1273 (E.D. Va. 1966).

14. Beckett v. School Board of the

City of Norfolk,'269 F.Supp. 118 (E.D.

Va. 1967); supplemental memorandum 12

Race Rel. L. Rep. 867 (June 2, 1967).

15. Brewer v. School Board of the

City of Norfolk, 397 F.2d 37 (4th Cir.

1968) en bancT

16: Beckett v. School Board of the

City of Norfolk, 302 F.Supp. 18 (E.D.Va.

1969) .

17. Beckett v. School Board of the

City of Nor folic, 308 F.Supp. 1274 (E.D.

Va. 1969); reversed and remanded sub.

nan. Brewer v. School Board of the City

of Norfolk, 434 F.2d 408 (4th tir.

7

Fourth Circuit before it finally produced

3

an acceptable desegregation plan. The

case was concluded on February 14, 1975,

four years after implementation of a

desegregation plan which used the tech

niques of rezoning, pairing and busing

approved in Swann v, Charlotte-Mecklenburg

Board of Education, 402 U.S. 1 (1971),

when counsel agreed to the following

order:

It appearing to the Court that all

issues in this action have been

disposed of, that the School Board of

the City of Norfolk has satisfied its

affirmative duty to desegregate, that

1970) en banc; cert. den. 399 U.S. 929

(1970).

18. Brewer, sub nom. Adams v.

School Dist. No. 5, Orangeburg Co. S.C. ,

444 F.2d 99 (4th Cir.) en banc; cert.

den. 404 U.S. 912 (197177

19. Brewer v. School Board of City

of Norfolk, 456 F. 2d ~94 3 (4 th Cir.).

cert, den. 406 U.S. 933 (1972).

20. Brewer v. School Board of City

of Norfolk, 500 F.2d 1129 (4th CirT

1974) (attorneys fees).

3 An eleventh appeal involved attorneys

fees. See note 1 supra.

8

racial discrimination through offi

cial action has been eliminated from

the system, and that the Norfolk

School System is now "unitary", the

Court doth accordingly

ORDER AND DECREE that this action is

hereby dismissed, with leave to any

party to reinstate this action for

good cause shown.

The Beckett/Brewer Case, 1956-1975.

The Norfolk school desegregation case

began in 1956 amidst Virginia's official

policy of "massive resistance" to Brown v.

Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954).

An injunction was issued and affirmed on

appeal in 1957, but no desegregation

occurred during the first four years after

Brown I. Beckett, supra, 246 F.2d 325. In

the fall of 1958, when the District Court

finally ordered the admission of 17 black

children to several Norfolk schools (while

denying the similar requests of 134

others), Virginia's Governor issued a

proclamation closing the schools Bee-

9

kett, supra, 260 F.2d 18; James v. Almond,

supra, 170 F.Supp. 331. After state and

federal courts simultaneously ruled the

school closing unconstitutional (James,

supra, Harrison v. Day, supra), Norfolk's

City Council was enjoined to prevent the

enforcement of resolutions cutting off

funds to the integrated schools. Duck

worth v, James, supra, 267 F.2d 224.

Even after the first handful of black

children were admitted to white schools,

the court found "the melody of massive

resistance lingers on" (185 F.Supp. at

462 ) , as black pupils ran a gauntlet set

up by the state's "pupil placement board"

laws and procedures. Farley v. Turner,

supra, 281 F.2d 131. Progress was slow.

By 1964, 1251 of 13,348 black children

elected to transfer to white schools while

the all-black schools remained intact.

Beckett, supra, 9 Race Rel. Law Rep. 1315.

10

Plaintiffs' attempts to obtain system-wide

desegregation and faculty desegregation

were initially rejected. Brewer, supra,

34 9 F.2d 414. In 1964 the board adopted

neighborhood attendance areas, and in some

districts allowed pupils an option to

attend either a black or a white school.

The neighborhood plan was amended re

peatedly as litigation continued during

1965-1968. See note 2 supra; Brewer,

supra, 397 F.2d 37.

In 1 96 9 the board proposed, and the

district court approved, implementation of

a so-called "optimal plan of desegrega

tion" which was an effort to create

"middle class" schools. Beckett, supra

308 F.Supp. 1274. The premise of the plan

was that 30% Negro schools would be

"optimal", and the board drew "neighbor

hood" school zones to achieve this result

in a few schools. The Fourth Circuit

rejected the plan in 1970 because the

"optimal" neighborhood zones left 76% of

the black elementary pupils attending 19

all-black schools. Brewer, supra, 434

F. 2d 408 . In 1970 the Fourth Circuit

finally ordered system-wide faculty

desegregation. Id.

In June 1971, following this Court's

decisions in Swann v. Charlotte Meck

lenburg Board of Education, 402 U.S. 1

(1971), and Davis v. Board of School

Commissioners of Mobile County, 402 U.S.

33 (1971), the Fourth Circuit ordered the

district court to require a plan based on

the proposal of the Government's expert

witness, the "Stolee C plan". See Adams,

supra, 444 F.2d 99. The Fourth Circuit

ordered "all techniques of desegregation,

including pairing or grouping of schools,

noncontiguous attendance zones, restruc

turing of grade levels, and the trans

12

portation of pupils." Id. at 101. The

district court ordered such a plan

implemented in 1971, but refused to

require free transportation to pupils

assigned to schools beyond walking

distance. On a tenth appeal to the Fourth

Circuit plaintiffs won an order requiring

free bus transportation on the ground that

the "Court cannot compel the student to

attend a distant school and then fail to

provide him with the means to reach that

school." Brewer, supra, 456 F.2d at 947.

The school board filed annual reports

about its implementation of the plan in

1972, 1973, and 1974. After receiving the

third such report, the district court

entered the order of February 14, 1975

quoted above. Counsel for plaintiffs and

defendants had consented to this order.

The case was thus concluded without any

further evidence, or any notice to members

13

of the plaintiff class. The order did not

dissolve or modify the court's previous

inj unction.

The system of segregation prior to the

1971 Plan.

Under Norfolk's 1969 desegregation

plan, one high school, five junior highs,

and 22 elementary schools were more than

90% black. Brewer, supra 434 F.2d at 410;

PX 144. Each of the 22 segregated black

elementary schools was established as part

of the system of de j ure segregation.

Sixteen of the 22 schools were 100% black.

PX 144. Eleven of these 22 schools are

still operated as elementary schools in

Norfolk, eleven others were closed between

4

1972 and 1980.

The 93-100% black elementary schools in

1969 which are still open are Bowling

Park, Tidewater Park, Young Park, St.

Helena, Chesterfield, Monroe, Roberts

Park, Tucker, Diggs Park, Lindenwood

and Oakwood. In addition a one-race

black Junior High School in 1969 is now

14

Plaintiffs' attack on the board's

present proposed plan, which is discussed

below, focuses on ten schools which were

all black in 1969. Nine of these schools

are located near all black public housing

projects. All of the schools and most of

the nearby housing projects were built

during the period of de jure school and

housing segregation. (PX. 163, 164, 165,

164F).

School Opened

Chesterfield (1920)

Tucker (1942)

Bowling Park (1953)

Diggs Park (1953)

Young Park (1954)

Roberts Park (1964)

Tidewater Park

(1964)

Jacox (1949)

Project Opened

Grandy Park (1953 )

Oakleaf Park (1942)

& Diggs Park (1952)

Bowling Park (1952)

Diggs Park (1952)

Young Park (1953)

Roberts Park (1942)

Tidewater Park (1955)

Roberts Park (1942)

& Roberts East (1953)

& Moton Park (1962).

operated as the Jacox Elementary school.

The 98-100% black elementary schools

closed between 1972 and 1980 were Carey,

Gatewood, Goode, Liberty Park, Lincoln,

Smallwood, Titus, Titustown, West, Lee,

and Marshall.

15

Monroe (1903) subsidized sec.8

housing

St. Helena (1966) Bell Diamond Manor

(1970's) (Subsidized,

§ 236)

The 1971 Desegregation Plan.

The 1971 plan eliminated all of

Norfolk's one-race schools. From 1971 to

the 1984 trial (and indeed to the present

time), Norfolk has not operated any school

which was all black or white. PX 152. The

desegregation plan for elementary schools

relied on the pairing and grouping

technique. Pupils were transported both

within single attendance areas, and

between paired noncontiguous areas. The

school authorities modified the plan to

create single zone attendance areas when

integrated residential areas developed.

When the board made changes to the plan

such as school closings it sought to place

16

a maximum of 70% of any race in a school,

but the board did not make annual adjust

ments to maintain racial balance.

5

In 1983 Norfolk's elementary schools

were well desegregated with enrollments

ranging from a high of 80.7% black at

Bowling Park to 23.7% black at Sewell

Point. All but seven elementary schools

were reasonably close (within plus or

minus 15 percentage points) to the

elementary average of 57% black students.

At the time of the trial (1983-84

school year) pupils in 12 elementary

schools were assigned in single attendance

areas surrounding the schools; the other

28 elementary schools were grouped and

paired in a pattern similar to the 1971

5 1983-84 figures are the most recent ones

in the record. The Fourth Circuit order

denying rehearing also denied plain

tiff's motion to supplement the record

to add 1984-85 and 1985-86 enrollment

statistics. App.162A.

17

plan. Agreed Ex.17(a). The plan remained

in effect during the appeal of this case

through the 1985-86 school year. After the

Fourth Circuit decision the board resolved

to implement its proposed new plan in the

fall of 1986.

The Proposed Plan

The school board adopted the Proposed

Plan February 2, 1983 by a 5-2 vote with 2

of its 3 black members dissenting. The

plan would create a contiguous single

attendance area for each elementary school

and break up the pairs and clusters which

were the basis for the 1971 plan. The new

zones did not reflect historic or func

tional Norfolk neighborhoods and the trial

court found that the term "neighborhood

schools" was being used "somewhat inac

curately". 627 F.Supp. at 817. The board

estimated the expected racial percentages

in each school based on initial assign-

18

merits. The trial judge credited estimates

that 10-15% of black pupils, but very few

whites, would elect majority-to-minority-

race transfers by which students could

transfer from schools enrolling over 70%

of their race to schools where their race

was under 50%.

The board estimated that ten schools

will become all-black if the plan is

implemented. The ten schools with their

racial percentages in 1969, in 1983, and

under the proposed plan (PX. 144, 147 —

before transfers) are:

ELEMENTARY 1969 1983 PROPOSEDSCHOOLS BLACK% BLACK% BLACK%Bowling Park 100.0% 80.7% 100.0%Tidewater Park 100.0% 68.8% 100.0%Young Park 100.0% 57.1% 100.0%St.Helena 98.9% 57.7% 99.1%Chesterfield 92.9% 69.9% 99.1%Monroe 98.9% 63.3% 99.0%Roberts Park 100.0% 76.6% 98.0%Jacox (all black jr.hi) 65.0% 98.0%Tucker 100.0% 47.2% 98.0%Diggs Park 100.0% 66.7% 96.9%

19

It was estimated that 4738 black and 54

white children would attend these 10

schools. The other 26 elementary schools

would have 8403 white and 7416 black

pupils. The reciprocal effect of this

realignment would create 14 majority

white schools . (Id.):

ELEMENTARY 1969 1983 PROPOSEDSCHOOLS BLACK % BLACK % BLACK %

Fairlawn 1 .9% 64.2% 49.9%

Coleman Place 0.0% 57.2% 44.5%

Calcott 0.0% 61 .8% 40.1%

Meadowbrook 6.8% 47.8% 40.0%Taylor 0.0% 36.4% 39.9%

Willoughby 4.6% 24.3% 36.1%

Camp Allen (opened 1970) 61.1% 36.0%Sewell Pt 31 . 3% 23.7% 34.1%

Sherwood Forest 0.0% 49.1% 30.1%Oceanair 4.1% 45.8% 29.0%LittleCreek .2% 57.0% 28.0%

Tarrallton 2.2% 60.9% 22.0%Ocean View 7.5% 56.8% 17.2%

Bay View 0.0% 44.6% 15.1%

The 14 schools would enroll 5423 whites

(64% of white elementary pupils) and 2587

blacks and average 67.7% white.

6

20

Only about 13 of the 36 schools would

remain reasonably close to the projected

59% black district average. Thirty-nine

percent of black elementary students would

attend the 10 all-black schools and

two-thirds of white pupils would attend

the 14 majority white schools. Only two

of the 22 black elementary schools which

existed in 1969 would be integrated; the

others are either closed or scheduled for

resegregation. The chart at the end of

this petition (page IB) contains the

enrollments for each elementary school in

1969, 1933 and under the proposed plan.

White Flight

The District Judge found that "the

primary objective of the Board in adopting

the Proposed Plan" was "providing a

response to the threat posed by white

flight to the long term integration of the

Norfolk school system...." 627 F.Supp. at

21

824 . In agreement with the Board's

contention, the Court found that "as a

result of busing, the Norfolk school

system has lost between 6000 and 8000

white students who otherwise would have

enrolled there"; and that "as a result of

white flight, the Norfolk schools are

faced with imminent resegregation." 627

F.Supp. at 822. The court said that "one

of the purposes of the Proposed Plan is to

stabilize elementary school population at

its present ratio of black students and

white students, roughly 60-40." Id. at

821. The judge found "the possibility

that the Proposed Plan would increase the

number of white students would be a strong

point in its favor." Id. at 822.

Before adopting the plan the board

employed a consultant, a sociologist, Dr.

David Armor who recommended that the board

proceed with the plan in a report dated

22

December 1982. Dr. Armor's report

concluded that white enrollment "declined

at an alarming rate during the 1970's"

because of mandatory busing policies (4th

Cir. App. 2164); that "racial balance has

little value if all schools are predomi

nantly black" (JD3.); and that "there is no

indication from Norfolk achievement test

results that racial balance has aided the

academic progress of its minority stu

dents; on the contrary, it is quite

possible that some damage was done during

the mid-seventies." Id. at 2164-65. He

predicted that if busing continued white

enrollment would "drop to about 8,000

students in 1987" (_id. at 2166) and then

7

The Armor report is Agreed Ex.43. The

board approved the plan after it

received Dr. Armor's report, and

expressly relied on his predictions

about the return of whites to the

system, predicting an increase of 500

white pupils the first year of the plan.

See Agreed Ex.lD, note *.

7

23

Norfolk would be "nearly 75 percent

minority and resegregated according to

8

most definitions of segregation." Id.

The report predicted that "If a neighbor

hood school plan is reinstated and white

enrollment stabilizes and increases to

1 7,000 or so over the next five years,

then voluntary methods could meaningfully

desegregate up to 10,000 black students

— including all of those black parents who

would prefer to attend desegregated

schools rather than their neighborhood

schools." Id* at 2168.

Petitioners have continually contested Dr.

Armor's white flight predictions and his

predictions have not come true. More than

14,000 whites and "other" races remained

in the system each year from 1981 to 1985.

The Fourth Circuit declined to consider

enrollment figures for 1984 and 1985

showing that the black-white ratio

remained stable at about 1984 59-41

percent black/white from 1981 through the

fall of 1985. The board opposed the

motion to supplement the record in the

district and appellate courts without

challenging the accuracy of these facts.

24

Dr. Armor's predictions that the

proposed plan would increase the number of

white pupils in the school system rest on

a public opinion poll he conducted for the

board. Dr. Armor polled groups of black

and white public school parents, white

pre-school parents, and white private

school parents on attitudes about the

racial composition of schools and said:

We find that virtually none of

the groups object to sending their

child to a school that is half white

and half black. Interestingly, while

black parents do not object to being

a minority, from 40 to 56 percent of

white parents do object to a school

where most of the students are black.

Id. at 2147-2149.

He found "three-fourths of black

parents favor busing to achieve racial

balance, while two-thirds of white public

parents oppose it", and that white

opposition was even stronger among the

25

pre-school and private school parents.

Parents were also polled about their

intentions if busing was ended, leading

Dr. Armor to state that "An end to busing

alone would probably capture nearly all

public school white parents, would nearly

double the participation rate for pre

school parents, and would capture about

one-fourth of private school parents..."

Id. at 2158. He concluded:

White parents oppose busing

rather strongly, even those who

participate in the current busing

program. Only a small fraction of

parents who are not now using Norfolk

schools will do so if busing contin

ues, but if it ends, it appears that

significant fractions of non-users

would enroll their children in

Norfolk public schools. An end to

busing could therefore lead to an

9

Although Dr. Armor's report does not

mention it, his poll data actually showed

that a majority of all Norfolk parents

favored the present desegregation plan,

when his results are weighted appro

priately for the fact that the district is

majority black. 4th Cir. App. 823.

26

increase in white enrollment, and to

long-term stabilization of white

enrollment, _Id. at 2163.

The District Court Decision

The district court opinion and order

of July 9, 1984 upheld the Proposed Plan

and denied injunctive relief to plain

tiffs. The Court reaffirmed the recitals

in the order of February 14, 1975 dismis

sing the Beckett/Brewer case and held

that "the Norfolk school system displays

today, as it did in 1975, all indicia of

'unitariness.*" 627 F. Supp. at 819.

Supporting its conclusion, the court said

that the school administration was

racially balanced, that the faculty and

staff is mixed and that "the overwhelming

majority of schoolchildren, of both races,

. . . attend schools whose student bodies

4

are mixed." _ld. The Court said that the

system was " free of discrimination" in

1975 and remains so today. Ij3. at 820 .

The court decided that the effect of

the 1975 order was "to shift the burden of

proof from the defendant School Board to

the plaintiffs, who must now show that the

1983 Proposed Plan results from an intent

on the part of the School Board to

discriminate on the basis of race." id.

Citing Keyes v. School District No. 1, 413

U.S. 189 (1973), the court defined a dual

system as "one which is created by state

authorities acting intentionally, with

discriminatory purpose, to segregate the

races." The court said cases such as

Green v. County School Board, 391 U.S. 430

(1968), and Swann, supra, which impose an

affirmative duty on dual school systems to

eliminate segregation, were inapplicable

since Norfolk had "fully discharged its

- 27 -

28

affirmative obligation to create a unitary

system" . <̂3. It held that plaintiffs

must prove an intent to discriminate and

that such intent "will not be inferred

solely from the disproportionate impact of

a particular measure upon one race." id.

It rejected plaintiffs' arguments that

Swann required the board to justify

one-race schools, saying "Swann is

inapplicable here". Jd. at 821.

The court found that the board's

purpose to use the new plan to attract

white students to the system and prevent

white flight was appropriate and indeed a

"strong point in its favor". jDd. at 822.

The court acknowledged that under United

States v. Scotland Neck Board of Educa

tion , 407 U.S. 484 (1972), white flight

will not excuse a failure to desegregate a

dual system, but found that case also

distinguishable because Norfolk "was

declared unitary in 1975 and the Board's

continuing, affirmative duty to desegre

gate was discharged at that time." Id. at

824.

The court rejected plaintiffs'

argument that another Board objective in

adopting the * planV e.g. , to increase the

level of parental involvement in the

schools, was pretextual, and also rejected

an argument based ©n the fact that an

alternative board plan (Plan Tl) could

have reduced busing while preserving

integration. id. at 824-25. The court

found Plan II "not viable" solely because

of the lack of vocal support in community

meetings; it made no finding that the plan

was infeasible or unreasonable. Id. at

: 2 5.

The court found that Norfolk's 15

public housing projects and 7 subsidized

housing projects are occupied almost

- 29 -

30

exclusively by blacks and house about 25%

of Norfolk's black children. i£. at 826.

Noting that the projects were built to

eradicate slums and provide livable

housing for low-income residents, the

court said it "defies logic" to suggest

that this makes the School Board respon

sible "in some way for the fact that under

the Proposed Plan, the racially identifi

able black schools are located in close

proximity to those projects." _id. at 826.

The Court of Appeals Decision

The Fourth Circuit affirmed the

finding that the district was now unitary

as not clearly erroneous, and agreed with

the district court that this shifted the

burden of proof to plaintiffs. The Court

acknowledged that, under Swann, school

boards have the burden of showing that any

one-race schools are "genuinely nondis-

criminatory and not vestiges of past

31

segregation." 784 F.2d at 535. However,

the court declined to apply the rule of

Swann to Norfolk, holding instead that:

"Once a constitutional violation has

been remedied, any further judicial

action regarding student assignments

without a new showing of discrimina

tory intent would amount to the

setting of racial quotas, which have

been consistently condemned by the

Court in the context of school

integration absent a need to remedy

an unlawful condition. 784 F.2d at

538.

Judge Widener's opinion for the panel

acknowledged that it could "find no case

decided in the same situation as that

before us", ( 789 F.2d at 537) and then

rested on reasoning in a Ninth Circuit

decision, Spangler v. Pasadena, 611 F.2d

1239 (9th Cir. 1979). The Fourth Circuit

expressly declined to apply the principles

of five of this Court's major school

decisions, Columbus Board of Education v.

Pen ick, 443 U.S. 449 ( 1979); Dayton Board

32

of Education v. Brinkman, 443 U.S. 526

(19 7 9 ) ( Dayton II); Keyes, supra; Swann,

supra; and Green, supra. The court said

"all of those cases involved state

sanctioned discriminating school districts

that had not dismantled their dual

systems." 784 F.2d at 539. "None had

reached the goal of a unitary system as

Norfolk has done." id.

The court approved the trial court's

reasoning on the question of white flight,

finding Scotland Neck, supra, and Monroe

v. Board of Commissioners, 391 U.S. 450

(1968), inapplicable because "Norfolk is

not operating a dual school system with a

present duty to desegregate." 784 F.2d at

539. The court held the board's consider

ation of white flight and its effort to

"stabilize school integration in Norfolk"

were "legitimate". id. at 540. The court

also generally approved the district

33

court's findings and reasoning on the

other issues. The court endorsed the

proposed plan as "a reasonable attempt by

the school board to keep as many white

students in public education as possible

and so achieve a stably integrated school

system." _Id . at 543. It found the plan's

"creating several black schools is

disquieting" but said that "that fact

alone is not sufficient to prove discrimi

natory intent." Id. at 543.

REASONS FOR GRANTING THE WRIT

I.

THE CASE PRESENTS QUESTIONS OF

OBVIOUS NATIONAL IMPORTANCE WHICH ARE

BOUND TO ARISE IN EVERY PAST, PRESENT

OR FUTURE SCHOOL DESEGREGATION CASE.

This is a case of enormous and

sweeping impact. The rule of law announced

by the courts below, would — if followed

34

generally — permit a very general

resegregation of the public schools of the

South.

During the 32 years since Brown v.

Board of Education, supra, the federal

courts have devoted countless hours to

deciding hundreds of school desegregation

cases. These decisions have eventually

produced a measure of integration in the

public schools of the South. Progress

toward eradicating segregation — typified

in many respects by Norfolk's experience

-- is directly traceable to this Court's

repeated rulings implementing Brown —

rulings which hold that school boards

have an affirmative duty to desegregate,

that the courts must demand desegregation

plans that "work", that desegregation must

not yield to public opposition, that the

need for remedial criteria sufficiently

specific to insure compliance justifies a

35

legal presumption against one-race

schools, and that racially "neutral"

assignment plans such as "neighborhood"

attendance zones are inadequate if they

fail to counteract the continuing effects

of past school segregation. These are the

principles of Green, Swann, and Davis,

supra, which the Court reiterated and

applied in such cases as Monroe, Scotland

Neck, Dayton II, and Columbus, supra. It

is these principles that the courts below

have declined to apply to Norfolk's

proposed plan. They have thus written a

charter for the resegregation of the

public schools of the South.

There can be no doubt that the

proposed plan could not pass muster as a

desegregation plan under Green, Swann and

Davis. If those decisions apply, the

invalidity of the proposed plan is obvious

and not seriously debatable. It is only

36

by declaring that the entire series of

precedents which are the bedrock of school

desegregation throughout the nation are

"inapplicable" that the courts below could

approve Norfolk's proposed plan.

This treatment of Swann and cognate

cases presents an issue of first impres

sion which is bound to arise in every

school case. At some point there must

come a time in every desegregation suit

when the school district is "unitary" in

the sense that it will have carried out

all of the judicial orders required by

Swann and achieved at least the momentary

termination of a dual system. Under the

reasoning of the courts below, the arrival

of that inevitable moment entitles each

school district immediately to dismantle

its desegregation plan, ignore the

principles of Swann, and adopt a new

plan with substantial resegre—

37

gative impact, provided only that this is

accomplished without revealing a purpose

to "discriminate" against black pupils.

The significance of such a rule is

manifest. It provides an easy and obvious

way to nullify school desegregation

decrees, threatening as a practical matter

to undermine school desegregation plans

everywhere. No principle of school

desegregation law established since Brown

is valid more than transitorily if the

Riddick ruling stands. Every desegrega

tion plan adopted since Brown may be

uprooted, and we will face another

generation of litigation over long-closed

school cases.

Promptly after the Fourth Circuit

decision, the U.S. Department of Justice,

supporting the decision below, issued a

press release listing 117 school districts

that have been declared unitary and 47

38

districts whose orders have been "dis

missed" . Department of Justice Press

Release dated February 18, 1986. The

Department, which has continued to oppose

the use of busing and other Swann reme

dies, issued the release in an effort to

encourage districts to emulate Norfolk.

Oklahoma City did so even before the

Fourth Circuit ruled, and actually

resegregated some of its schools in the

fall of 1 985. That case is now pending

after argument in the Tenth Circuit.

Dowell v. Board of Education of Oklahoma

City Public Schools, 606 F.Supp. 1548

(W.D. Okla. 1985), pending on appeal as

10th Cir. No. 85-1886, argued March 20,

1986.

The rule announced below also foments

wasteful litigation in school districts

which have not yet been declared unitary.

If the Fourth Circuit rule stands,

39

plaintiffs' lawyers have an overwhelming

incentive to resist the closure of all

school cases, and any acknowledgement that

a district is "unitary", as long as

possible, for they will know full well

that all desegregation is potentially lost

as soon as a district is declared "uni

tary". The plaintiffs' lawyers who

consented to the 1975 termination of the

Norfolk school case could then act on the

reasonable premise that achieving present

compliance through a permanent injunction

was a good enough reason to end a 19-year

old case. They could reasonably leave

future problems to be settled when and if

they arose, rather than anticipating the

prompt reversal of the plan that had

produced compliance. The Fourth Circuit's

Riddick doctrine would make such a

decision irresponsible in any future case,

because a lawyer would know that an

40

agreement that a system was unitary was

tantamount to an agreement that it could

be resegregated forthwith.

The importance of the case to the

next generation of black students in

Norfolk is also evident. The new plan is

particularly destructive in the way it

concentrates school segregation among

low-income blacks who reside in all-black

public housing projects. Almost forty

percent of Norfolk's black elementary

students will be segregated during the

formative kindergarten through sixth grade

years, if the plan is implemented, the

board will have substantially reconsti

tuted the situation which existed during

the 1960's when integration was available

only for the few blacks who took the

initiative of transferring out of black

schools. Monroe v. Board of Commission

ers, 391 U.S. 450 (1968).

41

II.

THE DECISIONS BELOW ARE INCONSISTENT

WITH THE PRINCIPLES OF SWANN V . BOARD

OF EDUCATION AND OTHER DECISIONS BY

THIS COURT.

We submit that the courts below erred

in declining to apply the principles of

Swann when judging the validity of

Norfolk's Proposed Plan. The courts did

not apply Swann's presumption against

one-race schools which was announced in

the unanimous opinion for the Court by the

Chief Justice:

No per se rule can adequately embrace

all the difficulties of reconciling

the competing interests involved; but

in a system with a history of segre

gation the need for remedial criteria

of sufficient specificity to assure a

school authority's compliance with

its constitutional duty warrants a

presumption against schools that are

substantially disproportionate in

their racial composition. 402 U.S.

at 26.

42

The courts below also declined to

require the school board to show that the

ten proposed one-race schools did not

result from past discrimination as

required in the next passage in Swann:

Where the school authority's proposed

plan for conversion from a dual to a

unitary school system contemplates the

continued existence of some schools

that are all or predominantly of one

race, they have the burden of showing

that such school assignments are

genuinely nondiscriminatory. The

court should scrutinize such schools,

and the burden upon the school

authorities will be to satisfy the

court that their racial composition is

not the result of present or past

discriminatory action on their part.

402 U.S. at 26.

The courts below similarly failed to

judge the "adequacy" of the proposed

single-attendance-zone plan in accord with

Swann's admonition that:

"Racially neutral" assignment plans

proposed by school authorities to a

district court may be inadequate;

such plans may fail to counteract the

continuing effects of past school

segregation resulting from discrimi

natory location of school sites or

43

distortion of school size in order to

achieve or maintain an artificial

racial separation. 402 U.S at 28.

A proper application of these

principles would surely condemn the plan

because it is undisputed that the same ten

schools which Norfolk now proposes to

operate as one-race schools were previ

ously operated as one-race all-black

schools as part of the de jure system of

segregation. The size and location of all

ten schools were determined during the

dual system. All ten schools were built

and planned to serve the black children

who lived nearby. Norfolk followed the

"classic pattern of building schools

specifically intended for Negro or white

students." Swann, supra, 402 U.S. at 21.

The schools are still located in the same

all-black neighborhoods near the same

all-black public housing projects that

44

existed under the dual system. The ghetto

areas which existed in 1960 and 1970

remain all-black today. The proposed

racial composition of these schools is the

obvious result of past discriminatory

action on the part of the school authori

ties, because the proposed plan substan

tially reconstitutes the segregated

neighborhood school plan of 1969 in those

school areas. The plan reestablishes the

pattern of de jure segregation in the same

place and by the same method that existed

previously. The school board could not

possibly show "that its past segregative

acts did not create or contribute to the

current [proposed] segregated condition."

Keyes, supra, 413 U.S. at 211.

The racial composition of these

schools is plainly the "result of past

discriminatory action" by school offi

cials. The conditions which made a

45

neighborhood assignment plan inadequate

and unacceptable in 1971 still exist:

namely all-black ghettos adjacent to

schools built expressly to serve those

ghettos. Thus the reason for the Swann

rule still exists. The fact that the

board temporarily obeyed the prior

injunction is not a sound basis for

applying a different rule of law to the

same facts which called for constitutional

relief when the courts did apply Swann to

Norfolk. Under Swann and Davis, none of

the proposed plan's purposes — preventing

white flight, increasing parental involve

ment, promoting neighborhood schools —

would justify extensive segregation which

could be readily avoided by available

plans of integration.

The courts below held that the Swann

inquiry whether pupil assignments are

"genuinely nondiscriminatory" or are "the

46

result of present or past discriminatory

action on [the State's] ... part" is

inappropriate and inapplicable because the

district has been "unitary" since 1975.

But nothing in the 1 975 order did, or

could appropriately, confer on the board

permission to undo the very steps that

made the system unitary. The Courts below

held that the system is presently unitary

because all the schools are now desegre

gated. But there is no logic to the notion

that a school system which becomes

"unitary" by eliminating segregation

remains "unitary" in perpetuity even if it

deliberately destroys the conditions that

made it unitary and reestablishes the

pattern of segregation that preceded its

"unitariness".

A school system that attains "uni

tariness" by effectuating a court-ordered

plan for integrating its schools is like a

47

heart patient who attains "health" by

having a pacemaker implanted. Just as a

patient who is healthy by virtue of a

pacemaker becomes sick when it is removed,

a school system that is "unitary" because

of an affirmative desegregation plan

employing special means of insuring

integration will become "dual" again when

it deliberately reconstitutes a substan

tial number of its one-race schools by

revoking the plan.

The opinions below assert that the

school' board acquired a new legal status

when it "discharged" its affirmative duty

to desegregate. But there is no reason in

a doctrine that a school board's temporary

obedience to a permanent injunction gives

it a legal right to reestablish the exact

situation that the injunction was designed

to bring to an end. If the facts sur

rounding the Norfolk schools had origin

48

ally permitted the board to dismantle its

dual system simply by abandoning illegal

action and acting without discriminatory

intent in a "color blind" fashion, there

might be logic to the lower courts'

approach. But, the history of efforts to

integrate Norfolk's schools plainly

demonstrates that the affirmative consti

tutional duty to eradicate segregation

could not be "discharged" by "color blind"

passivity. "Discharging" the affirmative

duty required pairing and non-contiguous

zones designed to produce actual integra

tion in the context of the all-black

schools built to serve segregated neigh

borhoods and one-race public housing

projects. The proposed plan to abolish

the pairing and to reestablish segregation

on the basis of the same neighborhood

pattern violates the same constitutional

duty that was temporarily fulfilled.

49

The reasoning of the Court below is

at war with Swann1s stated objective which

is "to dismantle the dual system". 402

U.S. at 28. In Dayton Board of Education

v. Brinkman, 433 U.S. 406, 414 ( 1977)

(Dayton I) , this Court directly held that

the rescission of a desegregation plan

which a board had a constitutional duty to

adopt would violate the Constitution.

See Dayton II, supra, 443 U.S. at 531,

n.5. And in Columbus Board of Education v.

Penick, 443 U.S. 449, 459 ( 1979), the

Court announced a corollary rule that

"Each instance of a failure or refusal to

fulfill this affirmative duty continues

the violation of the Fourteenth Amend

ment." It is logical that a deliberate

and intentional plan to destroy the

essential features of a remedial scheme

that made desegregation work and to

recreate the preexisting conditions is

50

equally a violation of the Fourteenth

Amendment. As stated in Dayton II,

supra, the "Board has had an affirmative

responsibility to see that pupil assign

ment policies and school construction and

abandonment practices 'are not used and do

not serve to perpetuate or re-establish

the dual school system.'" 443 U.S. at 538,

quoting Swann, supra.

The rule announced below would, as a

practical matter, repudiate Swann, Green,

Davis, Columbus and Dayton. Such a rule

deserves plenary review by this Court

because the practical repudiation of a

series of the Court's most important

constitutional decisions is as important

as the decisions themselves.

51

THE DECISIONS BELOW CONFLICT WITH THE

PRINCIPLES OF THIS COURT'S KEYES,

DAYTON, AND COLUMBUS DECISIONS DE

FINING UNCONSTITUTIONAL SEGREGATIVE

ACTIONS, AND WITH SCOTLAND NECK AND

OTHER CASES REJECTING *WHITE FLIGHT"

AND OPPOSITION TO DESEGREGATION AS A

JUSTIFICATION FOR SEGREGATION.

Both courts below acknowledged the

substantial segregative effect of the

proposed plan but found that "the dis

criminatory impact alone shown here is not

sufficient to make out such a claim" of

"intent to discriminate". 784 F.2d at 543.

Both courts understood that the primary

purpose of the plan was to attract white

students to the Norfolk public schools and

thereby counteract "white flight", but

found this acceptable. We believe that

both holdings are inconsistent with this

III.

Court's decisions.

52

Petitioners submit that the segrega

tive impact of the proposed Norfolk plan

is so stark as to put the case in the

class of extreme cases like Yick Wo v.

Hopkins, 118 U.S. 356 (1886), and Gomil-

1 ion v. Lightfoot, 364 U.S. 339 (1960)

where impact alone reveals a purpose to

segregate. See Arlington Heights v.

Metro. Housing Corp., 429 U.S. 252, 266

(1977). The historical background of de

j ure segregation in the very same schools

the proposed plan will segregate makes the

inference of segregative purpose inescap

able. Arlington Heights, supra, 429 U.S.

at 267. But petitioners need not rely on

impact and history alone because the

racial purpose in this case was not at all

covert.

The racial character of the board's

primary goal in implementing the plan is

quite openly acknowledged. The board

53

adopted the plan in reliance upon its

consultant's advice that white parents

opposed schools with black majorities, and

that the way to stem white flight and

increase the white school population was

to end busing (which whites opposed) and

create schools with the kind of racial

composition favored by whites. Since 57

percent of elementary pupils were black,

the only way to get a group of majority-

white schools was to create a group of

all-black schools. The proposed plan

groups two-thirds of the white pupils in

majority-white schools by the expedient of

creating ten all-black schools.

Both courts below acknowledged this

Court's holdings rejecting "white flight"

as a justification for continued segre

gation in other contexts. United States

v. Scotland Neck Board of Education, 407

U.S. 484, 491 (1972), and Monroe v. Board

54

of Commissioners, 391 U.S. 450 (1968). But

they limited those precedents to school

districts operating dual systems. Neither

court mentioned the fact that the objec

tive of stemming "white flight" was

explicitly racial. This plan is based on

the board's policy of trying to "stabi

lize" the ratio of black and white pupil

at about 60% black and 40% white. A

purpose to manipulate the racial composi

tion of the school system is not a

racially neutral or color blind purpose.

The concurring opinion in Scotland Neck,

supra, 407 U.S. 484, 493, by the Chief

Justice (joined by Justices Blackmun,

Powell, and Rehnquist) makes exactly this

point where "white flight" was urged to

justify the creation of a separate school

system, and the proposal was held uncon

stitutional in part because:

55

"...the Scotland Neck severance was

substantially motivated by the desire

to create a predominantly white system

more acceptable to the white parents

of Scotland Neck. In other words, the

new system was designed to minimize

the number of Negro children attending

school with the white children

residing in Scotland Neck." id. at

493.

So in Norfolk the board set out to

stop the district from becoming 75% or

greater black, as its consultant pre

dicted, and to stabilize the racial ratio.

The recommended means of accomplishing

this was to control the racial composition

of the schools attended by white pupils,

so as to attract whites to attend the

system. The cost of attracting whites was

segregating blacks in all-black "neighbor

hood" schools. This is as deliberate a

segregation policy as any ever encounter

ed, and is none the less unconstitutional

because it is overt and not covert. And of

course cases indicating that a benign

56

consideration of "white flight" might help

promote integration do not assert that

such a purpose is color blind or that it

is permissible as a justification for

creating ten all-black schools. Nor is the

policy any less racial because blacks in

the all-black schools can "volunteer" to

transfer out, or because the board

promises to make the "separate" schools

"equal".

The combination of an explicitly

racial purpose and a substantially

segregative impact makes out a plain

violation of the Fourteenth Amendment. See

Keyes, supra. There is no requirement

that the plaintiffs also prove that the

board adopted the plan with malice toward

black children. The fact that Norfolk's

present school authorities sincerely do

not believe that integration is worthwhile

does not justify segregation in 1986 any

57

more than the similar views of their

predecessors did. Brown v. Board of

Education, supra, is premised on the harm

segregation does to black children and not

on the theory that the proponents of

segregation necessarily had malice toward

them.

It is enough to show a violation of

the Equal Protection Clause that the

purpose of the board in abandoning the

desegregation plan was to appeal to the

views of white people who opposed the

desegregation plan. Black people are not

accorded equal protection of the laws when

a school board acts to segregate black

children because white people prefer a

different racial composition in the

schools. See Monroe, supra; Scotland

Neck, supra; cf. Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S.

1 (1958).

58

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons it is

respectfully submitted that this petition

for certiorari should be granted and that

the judgment below should be reversed.

Respectfully submitted,

HENRY L. MARSH, III

S.W. TUCKER

RANDALL G. JOHNSON

Hill, Tucker &

Marsh

509 North 3rd St.

P.O. Box 27363

Richmond, VA 23261

(804) 648-9073

GEORGE B. LITTLE

ELIZABETH TURLEY

TIMOTHY M. KAINE

Little, Parsley &

Cluverius, p.C.

1300 Fed. Reserve

Bank Bldg.

P.O. Box 555

Richmond, VA 23204

(804) 644-4100

GWENDOLYN JONES JACKSON P.O. Box 622

Norfolk, VA 23501

(804) 622-9031

♦JULIUS LeVONNE CHAMBERS

JAMES M. NABRIT, III

NAPOLEON B. WILLIAMS, JR.

99 Hudson Street

16th Floor

New York, N.Y. 10013

(212) 219-1900

Attorneys for

Petitioners

♦Counsel of Record

IB

]RACIAL I

SOURCES:

ELEMENT APPOSED PROPOSED PROPOSED PROPOSED

SCHOOLS WHITE BLACK TOTAL BLACK %

Bowling !1 0 665 665 100.0%

Tidewate:] 0 291 291 100.0%

Young Pa:1 o 541 541 100.0%

S t .Helen i 3 343 346 99.1%

Chesterf 4 427 431 99.1%

Monroe 7 701 708 99.0%

Roberts i| 10 489 499 98.0%

Jacox 13 630 643 98.0%

Tucker 7 336 343 98.0%

Diggs Pa: 10 315 325 96.9%

Lindenwoi 139 464 603 76.9%

Willard 183 519 702 73.9%

Norview 224 475 699 68.0%

Larrymori 313 581 894 65.0%

Granby 252 447 699 63.9%

Inglesidi 288 433 721 60.1%

Crossroa' 336 446 782 57.0%

Ghent 267 353 620 56.9%

Oakwood 226 277 503 55.1%

Suburban 198 241 439 54.9%

Poplar H 220 258 478 54.0%

Larchmon 334 335 669 50.1%

Fairlawn 183 182 365 49.9%

Coleman 452 363 815 44.5%

Calcott 293 196 489 40.1%

Meadowbr 320 213 533 40.0%

Taylor 232 154 386 39.9%

Willough 212 120 332 36.1%

Camp All 332 187 519 36.0%

Sewell P 420 217 637 34.1%

Sherwood 437 188 625 30.1%

Oceana ir 491 201 692 29.0%

LittleCr 747 291 1038 28.0%

T arralIt 295 83 378 22.0%

Ocean Vi 434 90 524 17.2%

Bay View 575 102 677 15.1%

IB

r NORFOLK PUBLIC SCHOOLS, 1969, 1983 AND PROPOSED PLAN,

proposed plan based on 1984 assignments before transfers).

1969 1969 1969 1969

WHITE BLACK TOTAL BLACK %

0 934 934 100.0%

0 513 513 100.0%

0 572 572 100.0%

4 357 361 98.9%

51 671 722 92.9%

13 1185 1198 98.9%

0 513 513 100.0%

I black Jr . High school in 1969)

0 477 477 100.0%

0 677 677 100.0%

0 713 713 100.0%

aned 1979)

406 273 679 40.2%

1067 115 1182 9.7%

642 20 662 3.0%

428 22 450 4.9%

1046 73 1119 6 • 5?£

aned 1978)

O 442 442 100.0%

542 36 578 6.2%

560 22 582 3.8%

630 100 730 13.7%

512 10 522 1.9%

865 0 865 0.0%

841 0 841 0.0%

561 41 602 6.8%

383 0 383 0.0%

750 36 786 4.6%

ened 1970)

603 275 878 31.3%

666 O 666 0.0%

678 29 707 4.1%

1254 2 1256 .2%

631 14 645 2.2%

1002 81 1083 7.5%

874 0 874 0.0%

1983

BLACK %

80.7%

68.8%

57.1%

57.7%

69.9%

63.3%

65 213 278 76.6%

238 442 680 65.0%

143 128 271 47.2%

121 242 363 66.7%

142 376 518 72.6%

214 537 751 71.5%

209 481 690 69.7%

282 515 797 64.6%

223 270 493 54.8%

272 430 702 61.3%

324 314 638 49.2%

232 266 498 53.4%

164 199 363 54.8%

235 359 594 60.4%

106 235 341 68.9%

379 243 622 39.1%

128 230 358 64.2%

327 437 764 57.2%

177 286 463 61.8%

283 259 542 47.8%

245 140 385 36.4%

396 127 523 24.3%

316 496 812 61.1%

444 138 582 23.7%

323 311 634 49.1%

356 301 657 45.8%

423 560 983 57.0%

137 213 350 60.9%

310 407 717 5 6 . QsZ

261 210 471 44.6%

PROPOSED PROPOSED PROPOSED PROPOSED

WHITE BLACK TOTAL BLACK %

0 665 665 100.0%

0 291 291 100.0%

0 541 541 100.0%

3 343 346 99.1%

4 427 431 99.1%

7 701 708 99.0%

10 489 499 98.0%

13 630 643 98.0%

7 336 343 98.0%

10 315 325 96.9%

139 464 603 76.9%

183 519 702 73.9%

224 475 699 68.0%

313 581 894 65.0%

252 447 699 63.9%

288 433 721 60.1%

336 446 782 57.0%

267 353 620 56.9%

226 277 503 55.1%

198 241 439 54.9%

220 258 478 54.0%

334 335 669 50.1%

183 182 365 49.9%

452 363 815 44.5%

293 196 489 40.1%

320 213 533 40.0%

232 154 386 39.9%

212 120 332 36.1%

332 187 519 36.0%

420 217 637 34.1%

437 188 625 30.1%

491 201 692 29.0%

747 291 1038 28.0%

295 83 378 22.0%

434 90 524 17.2%

575 102 677 15.1%

1983 1983 1983

WHITE BLACK TOTAL

110 460 570

100 220 320

149 198 347

161 220 381

135 314 449

163 281 444

1969 1969 1969 1969 1983 1983

WHITE BLACK TOTAL BLACK X WHITE BLACK

0 366 366 100.0X(closed 1978)

0 453 453 100.O X (closed 1979)

0 392 392 100.OX(closed 1972)

0 553 553 100.O X (closed 1980)

O 378 378 100.OX(closed 1972)

0 474 474 100.OX(closed 1970)

0 519 519 100.OX(closed 1979)

0 277 277 100.OX(closed 1970)

0 472 472 100.OX(closed 1980)

7 449 456 98.5X(closed 1974)

10 525 535 98 .IX (closed 1978)

45 136 181 75.1X(closed 1976)

281 559 840 66.5X 143 224

410 45 455 9.9X 102 192

716 32 748 4.3X(closed 1981)

245 10 255 3.9X(closed 1978)

746 27 773 3.5X 38 53

271 6 277 2.2X (closed 1972)

252 1 253 .4X(closed 1980)

168 0 168 0.OX 195 84

124 O 124 0 .OX(closed 1980)

____________________ — —

18284 13877 32161 43.IX 8771 11611

1983 1983 PROPOSED PROPOSED PROPOSED PROPOSED

TOTAL BLACK * WHITE BLACK TOTAL BLACK %

367 61.O X (proposed closing)

294 65.3%(proposed closing)

91 58.2*:

279 30.IX(proposed closing)

20382 57.OX 8457 12154 20611 59.OX

Hamilton Graphics, Inc.— 200 Hudson Street, New York, N.Y.— (212) 966-4177