United States v. Yonkers Board of Education Opinion

Public Court Documents

February 9, 1987 - December 28, 1987

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. United States v. Yonkers Board of Education Opinion, 1987. 3c8218a0-c79a-ee11-be37-000d3a574715. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c34e0a59-8997-4c32-9086-86e214145684/united-states-v-yonkers-board-of-education-opinion. Accessed February 23, 2026.

Copied!

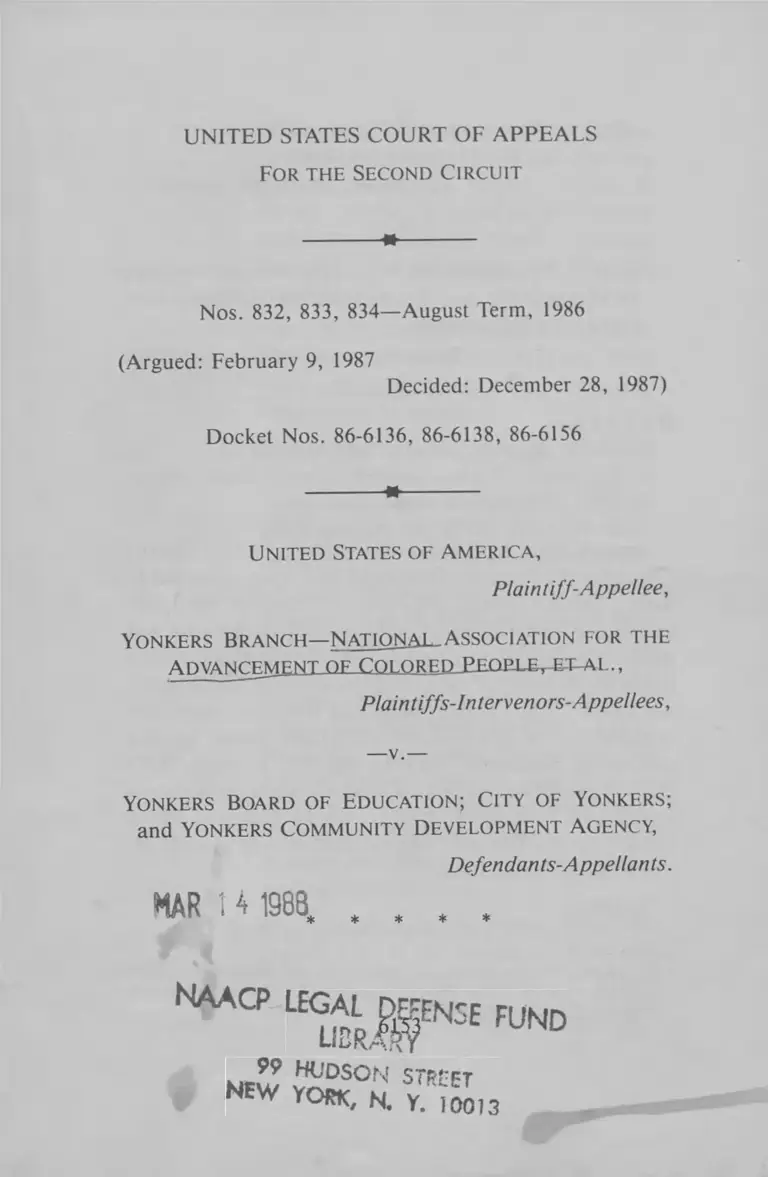

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

For the Second Circuit

*

Nos. 832, 833, 834—August Term, 1986

(Argued: February 9, 1987

Decided: December 28, 1987)

Docket Nos. 86-6136, 86-6138, 86-6156

-----------* -----------

Yonkers Rr anch—National .Association for the

Advancement of Colored Êeoeue^e^ al . ,

Yonkers board of Education; City of Yonkers;

and Yonkers Community development Agency,

United States of America,

Plaintiff-Appellee,

Plaintiffs-Intervenors-Appellees,

—v.—

Defendants-Appellants.

MAR H 1988, , , , ,

NAACP

City of Yonkers; and Yonkers Community

Development Agency,

Third Party, Plaintiffs-Appellants,

—v.—

United States Department of Housing and Urban

Development; and Secretary of Housing and

Urban development,

Third Party, Defendants-Appellees.

B e f o r e

*

Kearse, Pratt,* and Miner,

Circuit Judges.

*

Appeals from a judgment of the United States District

Court for the Southern District of New York, Leonard B.

Sand, Judge, finding the City of Yonkers liable for

intentional racial segregation in subsidized housing and

public schools, finding the Yonkers Board of Education

liable for intentional racial segregation in public schools,

see 624 F. Supp. 1276 (1985), and ordering, inter alia,

construction of 200 units of subsidized family housing

outside of Southwest Yonkers, see 635 F. Supp. 1577

(1986), and desegregation of school system, including a

system-wide voluntary magnet school program to be

funded by the City and implemented by the Board, see

635 F. Supp. 1538 (1986).

Affirmed.

--------•--------

* Judge Winter, originally a member of the panel, subsequently

recused himself. Judge Pratt was appointed to the panel pursuant to

Local Rule § 0.14(b).

6154

Clint Bolick, Washington, D.C. (William

Bradford Reynolds, Assistant Attorney

General, Walter W. Barnett, Joshua P.

Bogin, Marie K. McElderry, United

States Department of Justice, Washing

ton, D.C., on the brief), fo r Plaintiff-

Appellee.

Michael H. SUSSMAN, Yonkers, New York

(Sussman & Sussman, Yonkers, New

York, on the brief), fo r Plaintiffs-

In tervenors-A ppellees.

JOHN H. Dudley, J r ., Detroit, Michigan

(John B. Weaver, Mark T. Nelson, Butzel

Long Gust Klein & Van Zile, Detroit,

Michigan, on the brief), fo r Defendant-

Appellant Yonkers Board o f Education.

Rex E. Le e , Washington, D.C. (Carter G.

Phillips, Mark D. Hopson, Sidley & Aus

tin, Washington, D.C., Gerald S. Hart

man, Michael W. Sculnick, Thomas G.

Abram, Vedder, Price, Kaufman, Kamm-

holz & Day, New York, New York, Jay B.

Hashmall, Corporation Counsel for the

City of Yonkers, Yonkers, New York, on

the brief), fo r Defendants-Appellants-

Third-Party-Plaintiffs-Appellants City o f

Yonkers and Yonkers Community Devel

opment Agency.

M. WILLIAM Munno , New York, New York

(James F.X. Hiler, Ronald A. Nimkoff,

Heidi B. Goldstein, Seward & Kissel,

New York, New York, on the brief), fo r

6155

Joseph Galvin, Alfred T. Lam herd, Paul

Weintraub, Frank Furgiuele, Joseph

M .A. Furgiuele, Jerald Katzenelson and

Salvatore Ferdico, and The Crestwood

Civic Association, Inc. as Amicus Curiae

on Behalf o f Defendants-Appellants-

Third-Party-Plaintiffs-Appellants.

Puerto Rican Legal Defense & Educa

tion FUND, INC., New York, New York

(Linda Flores, Jose Luis Morin, Kenneth

Kimerling, New York, New York, of

counsel) filed a brief fo r the Organization

o f Hispanic Parents o f Yonkers as A m i

cus Curiae on Behalf o f Plaintiff-

Appellee and Plaintiffs-Intervenors-

Appellees.

HENRY MARK HOLZER, Brooklyn, New York

(Daniel J. Popeo, George C. Smith,

Washington Legal Foundation, Washing

ton, D.C., of counsel) filed a brief fo r

the Save Yonkers Federation and the Co

alition o f Concerned Yonkers Citizens on

Behalf o f Defendants-Appellants-Third-

Party-Plain tiffs-A ppellants.

*

KEARSE, Circuit Judge:

Defendants City of Yonkers (the “City”), Yonkers

Community Development Agency (“CDA”), and Yonkers

Board of Education (the “Board”) appeal from a judg

ment entered in the United States District Court for the

6156

Southern District of New York following a trifurcated

bench trial before Leonard B. Sand, Judge, holding the

City liable for racial segregation of housing in Yonkers,

holding both the City and the Board liable for racial

segregation of the Yonkers public schools, and ordering

each defendant to take steps to remedy the segregation

for which it was found liable. The district court held that

the City, by its pattern and practice of confining subsi

dized housing to Southwest Yonkers, had intentionally

enhanced racial segregation in housing in Yonkers, in

violation of Title VIII of the Civil Rights Act of 1968

(“Title VIII” or the “Fair Housing Act”), 42 U.S.C.

§ 3601 et seq. (1982), and the Equal Protection Clause of

the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Consti

tution. The court held that the actions of the Board,

including its decisions relating to individual schools, fac

ulty assignments, and special education, and its selective

adherence to a neighborhood-school policy in light of the

City’s segregative housing practices, combined with its

failure to implement measures to alleviate school segrega

tion, constituted intentional racial segregation of the

Yonkers public schools, in violation of Titles IV and VI of

the Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. § 2000c et seq.

(“Title IV”) and § 2000d et seq. (“Title VI”) (1982), and

the Equal Protection Clause. The court held that the City

had contributed to the segregation of the Yonkers public

schools by means of, inter alia, its segregative housing

practices, and that its segregative intent was revealed by

the foreseeable effects of its housing practices, its direct

involvement with certain schools, and the mayor’s ap

pointments to the Board of persons firmly committed to

maintaining the segregated state of the schools that both

reflected and enhanced the segregated residential pat

terns. The court thus found the City liable for intentional

6157

racial segregation of the schools in violation of Title IV

and the Equal Protection Clause.

To remedy the segregation in housing, the district court

ordered principally that the City provide sites for 200

units of public housing in nonminority areas; the order

stated that if the City did not identify sites the court

would do so. The court ordered that the City reallocate at

least a substantial portion of its federal housing grant

funds for the next several years to a fund to be used to

foster the private development of low- and moderate-

income housing in a way designed to advance racial

integration.

To remedy the school segregation, the court ordered the

Board to take steps toward the desegregation of each

school within specified numerical parameters by the 1987-

88 school year. To this end, the Board was ordered to

create magnet schools and implement a program in which

it would assign each student to a school from among

those nominated by his or her parents. The court ordered

the City to fund the school desegregation plan.

On appeal, the City and the Board raise a variety of

objections to the district court’s rulings on liability and

remedies. The City contends principally that the court (1)

improperly imposed an affirmative duty on the City to

build public housing outside of the City’s predominantly

minority neighborhoods; (2) erroneously found (a) that

Yonkers’s segregated housing patterns were the result of

the City’s intentional discrimination, and (b) that the

City’s housing decisions were a cause of school segrega

tion; and (3) improperly considered the mayor’s Board

appointments in holding the City liable for school segre

gation. The Board contends principally that (1) the court

erred in considering the City’s deliberately segregative

6158

housing practices as a factor relevant to the Board’s

liability for school segregation, and (2) the court’s finding

of segregative intent on the part of the Board was clearly

erroneous.

We conclude that the district court properly applied the

appropriate legal principles, that its findings of fact are

not clearly erroneous, and that its remedial orders are

within the proper bounds of discretion. We therefore

affirm the judgment in all respects.

A. BACKGROUND

The present litigation, unique in its conjoined attack on

the actions of state and municipal officials with respect to

segregation in both schools and housing, brings into

question acts, omissions, policies, and practices of the

City and the Board of Education over five decades. The

case was commenced by the United States in December

1980, with the filing of a complaint alleging, inter alia,

that the City and CDA had intentionally engaged in a

pattern of selecting sites for subsidized housing that

perpetuated and aggravated residential racial segregation,

and that the City and the Board had, by their intention

ally discriminatory acts and omissions, caused and per

petuated racial segregation in the schools. In June 1981,

the Yonkers Branch of the National Association for the

Advancement of Colored People (“NAACP”) and an

individual minority student, by her next friend, were

allowed to intervene as plaintiffs on behalf of themselves

and all others similarly situated, see 518 F. Supp. 191,

201-03 (S.D.N.Y. 1981), and the action was subsequently

certified as a class action.

6159

Trial on the liability issues was held over a period of

some 14 months in 1983 and 1984. During the 90 trial

days, evidence was heard from 84 witnesses; depositions

of 38 additional witnesses were introduced; and thou

sands of documents were received in evidence. In Novem

ber 1985, in an exhaustive and well documented opinion

reported at 624 F. Supp. 1276-1553, Judge Sand found

the City and CDA liable for housing segregation and

found the City and the Board liable for school segrega

tion. Following hearings as to the appropriate remedies

for these violations, the court ordered system-wide, com

prehensive remedies. See Parts A .I.C. and v4.Il.G. below.

In view of the challenges made in these appeals to the

sufficiency of the evidence to support the district court’s

findings of intentional discrimination and the contentions

that the remedies ordered are overly broad, we summarize

at some length the evidence supporting both the findings

and the imposition of system-wide remedies.

I. Housing Segregation

The City of Yonkers, New York, is a section of West

chester County roughly 4 to 6 miles long by 3 to 3-‘/2

miles wide, just north of New York City’s Bronx County.

For purposes of this suit Yonkers is regarded as consisting

of three basic geographic areas, referred to as East

Yonkers, Northwest Yonkers, and Southwest Yonkers.

Southwest Yonkers, which comprises less than one-

quarter of the City’s land mass, is the City’s most densely

populated and urban area. Characterized as containing

the “downtown” or “inner city” area, it is the only

section having any significant amount of industrializa

tion.

6160

At trial, there was little dispute that, at least as of 1980,

when this suit was commenced, the residents of Yonkers

were largely segregated by race, with the minorities con

centrated in Southwest Yonkers. United States Census

figures for 1980 showed that minorities, defined as blacks

or hispanics, made up 18.8% of Yonkers’s total popula

tion; minorities made up 40.4% of the population of

Southwest Yonkers but only 5.8% of East and Northwest

Yonkers. Southwest Yonkers, while housing only 37.5%

of Yonkers’s total population, housed 80.7% of

Yonkers’s minority population.

The minority population of Yonkers grew to 18.8% in

1980 from 2.9% in 1940. During this period, the concen

tration of minorities in Southwest Yonkers increased as

follows:

T ota l

M in o r ity

P ercen ta g e

M in o r ity

P erc en ta g e

o f S o u th w e s t

M in o r ity

P ercen ta g e

O u ts id e o f

S o u th w e s t

1940. .. 2.9 3.5 2.0

1950... 3.2 4.5 1.6

1960... 4.5 6.7 2.8

1970... 10.2 19.8 3.9

1980... 18.8 40.4 5.8

Concentration has also been evident within the South

west itself. In 1940, when minorities constituted only

2.9% of Yonkers’s total population, two of the 10 census

tracts in Southwest Yonkers had minority populations

between 10% and 50%. In 1980, when minorities consti

tuted 18.8% of Yonkers’s total population, four of the 10

Southwest tracts had minority populations between 20

and 50%, and five had minority populations of more

than 50%. A census-tract map showing the 1980 concen

trations is attached to this opinion as Appendix A.

6161

Northwest Yonkers and East Yonkers contained 14

census tracts in 1980, divided into 32 sub-tracts. Of the

32, only two had minority populations of 7% or more.

One, located in Northwest Yonkers, had a minority popu

lation of 28.6%, most of whom lived in a neighborhood

abutting a Southwest Yonkers tract that had a minority

population of more than 50%. The other, a neighborhood

in East Yonkers known as Runyon Heights, had a minor

ity population of 79.8%. Runyon Heights was a middle-

income community founded early in the century on a

large tract of land owned by a state senator who regularly

brought busloads of black residents from Harlem for

picnics at which he auctioned off parcels of land to them.

Runyon Heights is bounded to the north by a white

neighborhood called Homefield. The original deeds for

many Homefield properties contained restrictive cove

nants prohibiting the sale of such properties to minorities,

and as Runyon Heights developed, the Homefield Neigh

borhood Association purchased and maintained a four-

foot strip of land as a barrier between the streets of the

two neighborhoods. “To this day, Runyon Heights streets

terminate in a dead-end just below this strip.” 624 F.

Supp. at 1410.

The current location of low-income subsidized housing

in Yonkers corresponds largely to its concentrations of

minority residents. As of 1982, the City had 6,800 units

of subsidized housing; of these, 6,566 units, or 96.6%,

were located in or adjacent to Southwest Yonkers. A map

showing the City’s subsidized housing sites is attached to

this opinion as Appendix B. Only two subsidized housing

projects were not in or adjacent to Southwest Yonkers.

One was a family project located in Runyon Heights; the

other, also in East Yonkers, was a project for senior

6162

citizens, the majority of whose residents had been ex

pected to be, and were, white. Block-by-block maps for

1950-1980, showing more detail than the census tracts and

sub-tracts, revealed that all sites approved by the City for

low-income or low-and-middle-income family housing

were in or very near neighborhoods that already had high

percentages of minority residents.

Given the facts as to Yonkers’s segregated housing

patterns, most of the trial evidence on housing issues

concerned whether the City’s subsidized housing deci

sions bespoke a racially segregative intent.

A. Evidence as to the City’s Subsidized Housing

Decisions

During the pertinent periods, Yonkers’s governing

body was its City Council (“Council”), comprising the

mayor, elected in a City-wide election, and 12 council-

men, each elected by one of the City’s 12 wards. The

Yonkers Planning Board (“Planning Board”) consisted of

seven nonpaid citizens appointed by the mayor. The

Yonkers Municipal Housing Authority (“MHA”), a public

corporation organized in the 1930’s pursuant to New

York State’s Public Housing Law, was the entity autho-

rized'to propose, construct, and operate public housing in

Yonkers.

Under state law, federal funding could not be requested

for a site proposed by MHA until the site was either (1)

approved by a majority vote of both the Planning Board

and the Council, or (2) approved by at least three-

quarters of the Council if less than a majority of the

Planning Board approved. According to the testimony of

one member of the Council, the opposition of any coun-

6163

oilman to a project proposed for his own ward was

routinely honored by the other Council members.

1. Housing Decisions in 1948-1958

Prior to 1949, the City had erected two housing pro

jects, both in Southwest Yonkers. The second came about

apparently as community leaders’ response to concerns

expressed in the late 1930’s about difficulties blacks were

encountering in obtaining decent and affordable housing

in the private market. Thus, “the City resolved to build a

public housing project ‘for Negroes’ and set about find

ing a suitable site on which to do so. . . . Various sites

were rejected on the ground that the level of minority

concentration there was not sufficiently high, and the site

eventually selected in 1940 was in one of the most heavily

minority areas of Southwest Yonkers.” 624 F. Supp. at

1312.

In 1949, pursuant to the National Housing Act of 1949

(“ 1949 Housing Act”), ch. 338, 63 Stat. 413 (codified, as

amended, at 42 U.S.C. § 1441 et seq. (1982)), which

provided federal funds for urban renewal, the City ap

plied for the reservation of funds to build 750 units of

low-income housing. Its application was approved, but it

was not to receive the funds until it had officially desig

nated specific sites and these were approved by the federal

Public Housing Administration (a predecessor of the

United States Department of Housing and Urban Devel

opment (collectively “HUD”)). The City’s initial deadline

for submitting approved sites was August 31, 1950. In

February 1950, MHA began proposing sites for the con

struction of these units.

MHA’s first proposed site was a vacant, largely City-

owned, parcel of land located in an overwhelmingly white

6164

area of Northwest Yonkers. The City’s ownership and the

nonuse of the land would have made it a relatively

inexpensive building site and avoided any residential dis

placement and relocation problems. Neighborhood

groups, however, swiftly opposed designation of this site,

stating that the new housing would be occupied by per

sons coming from slum areas and that the old slums

would continue to exist. The groups recommended clear

ance of the existing slum areas and the construction of

new housing on those sites. The Planning Board rejected

MHA’s proposed site, citing the parcel’s nonconformity

with planning standards such as sufficiency of school and

shopping facilities.

The next two sites proposed by MHA in 1950 were

located in white neighborhoods of Southwest Yonkers.

Initially, the councilmen of the two wards in which these

sites were located recommended approval. As to one site,

however, residents of the area appeared at a Planning

Board meeting to express their opposition on the ground

that the terrain was irregular and that the presence of

such housing would tend to harm property values in the

area; their councilman withdrew his support for the

project, and the site was not approved. The other pro

posed site was initially approved by both the Planning

Board and the Council. However, when an attempt was

made to enlarge the approved area, community groups

opposed both the enlargement and the original site desig

nation, principally citing the likely deterioration of prop

erty values. Eventually, the councilman from this ward

withdrew his support, the Planning Board voted unani

mously to disapprove the requested expansion, and MHA

abandoned its proposal for even the originally approved

project.

6165

By December 1950, the City had approved just one

project, to which there had been no community opposi

tion, for 274 units. Its site, previously zoned for industrial

use, was in a section of Southwest Yonkers having one of

the highest concentrations of minorities.

After all of the other MHA-proposed sites had been

rejected, a federal official warned that the City would

lose its reservation of funding for the remaining 476 units

unless it acted to put additional units into development

immediately. The City’s response was to expand the

previously approved Southwest Yonkers project to 415

units, notwithstanding a prior Planning Board recom

mendation that no more than 250 units be placed on any

site.

In the period 1951 to 1953, MHA proposed 9 more sites

for subsidized low-income housing in predominantly

white neighborhoods, four in Southwest Yonkers and five

in Northwest and East Yonkers. Eight of these proposals

prompted vigorous opposition by community civic and

social groups, who sent petitions and resolutions to the

Planning Board and the councilmen, contending that

such projects in their areas would “lead to the eventual

deterioration of the surrounding community by the ele

ment which they attract.” None of MHA’s proposed sites

was approved by the City.

In the meantime, between 1,200 and 3,000 applications

had been received for the 415 units that had been ap

proved. Notwithstanding recognition by the Planning

Board and the public of the “desperate need” for addi

tional subsidized housing, no other sites were approved.

The City thereby lost allocation of federal funds for the

remaining 335 units of its original 750-unit allocation

under the 1949 Housing Act.

6166

In 1956, the City was able to renew its reservation of

funds for 335 units, and MHA promptly proposed four

new sites. One of these was quickly rejected because it

was in the path of a proposed highway. The remaining

three prompted strong community opposition. Two of

these, including one described by HUD as “extremely

desirable” for subsidized housing, were in all-white neigh

borhoods of East Yonkers. The residents of both areas

vigorously voiced their opposition at rallies, in petitions,

by telegram, and by attending Council meetings in num

bers ranging from 400 to 1,000. The City rejected these

two sites.

The fourth proposed site was in Runyon Heights, the

predominantly black community in East Yonkers. Repre

sentatives of the neighborhood opposed the building of

low-income housing there on the ground that predomi

nantly white communities had successfully opposed hav

ing such projects in their neighborhoods and Runyon

Heights should not be the only community in which such

a project would be built. They contended that it would be

preferable to integrate Runyon Heights into the com

munities surrounding it and that the placement of low-

income housing in Runyon Heights would have the

contrary effect of enhancing its racial isolation. The City

rejected this site as well.

At least four other sites for low-income housing were

formally considered in 1957; none was approved by the

City.

In 1958, MHA proposed five sites, four new ones plus

one that had previously been rejected because of conflict

ing highway plans. An MHA official described the sites to

the Planning Board as “ ‘the least objectionable’ of those

surveyed” but nonetheless predicted that there would be

6167

“ ‘a lot of objections on the grounds of race or age in

certain sites.’ ” 624 F. Supp. at 1299.

Two of MHA’s proposed sites in Southwest Yonkers—

one in a predominantly white area, and the other in a

predominantly minority area—were disapproved by the

Planning Board because they lay in the paths of proposed

highways. The Council, however, by a three-fourths vote,

overrode the Planning Board’s opposition to these two

sites; it approved family housing units for the site in the

predominantly minority neighborhood and senior citizen

units for the site in the predominantly white neighbor

hood.

The other three sites proposed by MHA in 1958 were

approved by the Planning Board. Two of these sites were

in overwhelmingly white neighborhoods, one in East

Yonkers and described by the City’s Planning Director as

“ideal” in terms of transportation, shopping, recreation,

and schools, and the other in Southwest Yonkers; the

third site was in Runyon Heights. All met with opposition

from the residents of their respective neighborhoods.

From the two white areas, taxpayer and civic groups

wrote their councilmen shortly before the Council was to

vote, describing their general opposition as follows:

We personally prefer a public referendum with

time to acquaint each and every citizen with the full

facts on public housing. Where will these tenants

come from? How will we provide schools? How

much will it cost us over the years? What safeguards

do we have against our having to absorb the over

flow from Puerto Rico or Harlem?

The Council voted to reject the sites proposed for the

white neighborhoods. It approved the project proposed

for Runyon Heights.

6168

Thus, in 1958, the City finally approved sufficient

family housing sites to use the remainder of the 750 units

that had been allocated to it for 1949. All 750 units were

constructed in neighborhoods of high minority concentra

tion; the City had rejected all sites proposed for family

housing in any neighborhood not already having a high

minority concentration.

2. Housing Decisions in 1958-1967

For the next several years, MHA and the City concen

trated on finding sites for senior citizen housing. The

councilmen and the public equated senior citizen housing

with housing for whites, and in fact, few of the residents

of Yonkers’s senior citizen housing projects have been

minorities.

Such housing, so long as not denominated “low-

income,” was not perceived as being for minorities and

met with little or no community opposition. In 1961, for

example, the City approved a senior citizen housing site

for 300 units in a minority neighborhood of Southwest

Yonkers; though the site abutted a predominantly white

neighborhood, the only opposition came when expansion

of the project was proposed and residents complained of

area overcrowding. In 1963, however, when MHA pro

posed eight senior citizen sites, four in East Yonkers and

four in white neighborhoods of Southwest Yonkers, a

local news article, headlined “8 Possible Sites Picked for

Low-Rent Housing,” reported that these locations might

also be considered to house families displaced by urban

renewal. Public protests followed, including a letter from

a community association representing more than 2,000

families expressing concern that “ [t]o penetrate the com

munity with subsidized housing would tend to deteriorate

6169

realty values and adversely affect the character of th[e]

community.” Six of the proposed sites were withdrawn.

In 1964, the City sought federal funds to begin a new

stage of urban renewal. When its application was rejected

due to its poor record with respect to building subsidized

housing for displaced residents, the City began once again

to look for suitable sites for family housing. In 1965,

MHA proposed eleven sites, including five in East

Yonkers or white areas of Southwest Yonkers and four in

minority areas of Southwest Yonkers. Protests and peti

tions were lodged against the five white-area sites on

grounds of potential overcrowding and the effect on

property values. A news report quoted one resident of

East Yonkers as complaining that the City wanted to put

in her neighborhood “ ‘everything [her family had] tried

to get away from’ ” by moving from urban areas to East

Yonkers, and another resident as saying “ ‘it wasn’t that

she didn’t believe in racial or social or economic integra

tion . . . but [that] those people from Yonkers would feel

so out of place here . . . it would not be fair to them.’ ”

624 F. Supp. at 1303. The Planning Director supported

the East Yonkers sites; the Planning Board approved only

the four sites that were in minority areas of Southwest

Yonkers.

These four minority-area sites were then approved by a

committee of the Council and one was approved by the

Council itself. Before any of the sites could be formally

submitted to HUD, however, HUD wrote the City sug

gesting “scattered sites” instead of site concentration in

Southwest Yonkers because “ [relocation feasibility, even

though quantitatively adequate, falls short of acceptabil

ity if racial containment will result from the proposed

provision of relocation housing.” In response, a subcom-

6170

mittee of CDA, the coordinating agency for all of

Yonkers’s urban renewal projects, compiled a list of 19

sites scattered throughout Yonkers; however, when this

list was made public it caused “alarm in the community.”

According to one news report, at a meeting of Yonkers

housing agencies, “fear was expressed by several speakers

that the public is not yet ready to accept the federal

government’s plan for racial and economic integration on

a citywide basis.” None of the 19 sites was approved.

In 1967, the Council finally approved three sites from

among those proposed by MHA in 1965. Despite the

Council’s awareness of the federal preference for scat

tered sites, the three sites approved were located in

densely occupied, heavily minority sections of Southwest

Yonkers. HUD refused to approve the sites.

3. Housing Decisions in 1968-1974

During the period 1968 to 1974, the City turned to

other federal programs for subsidized housing. CDA

sought out private sponsors for a combination of low-

and-moderate-income family projects; it focused its ef

forts solely on sites in Southwest Yonkers.

Proposed sites that were in the Southwest’s predomi

nantly white areas drew heated community opposition.

Notwithstanding the view expressed by former council

man Edward O’Neill that race played no role in site

selections—because “ ‘nothing was ever expressed for the

record to indicate that it did play a role,’ ” 624 F. Supp.

at 1311—several City officials testified that race was a

factor. Some stated that their constituents tended to

equate low-income housing with minorities. Others “pub

licly identified the issue before them as being whether the

residents of Yonkers were ‘ready’ for the economic and

6171

racial integration being urged upon the City” by HUD

and groups such as the NAACP and the Council of

Churches. Id. at 1310.

CDA’s director, Walter Webdale, testified to his view

that the high level of emotionalism exhibited at public

meetings indicated that residents were concerned about

far more than mechanical matters such as the size of the

street or the availability of public utilities, and that

“racial considerations d[id] come into play.” He gave as

an example the reaction to a site proposal for the north

ern end of Southwest Yonkers which, though just a few

blocks from a predominantly minority area, was immedi

ately surrounded by a white neighborhood. A Catholic

Church group, led by their pastor, opposed use of this site

for family housing and urged that it be used for a senior

citizen project instead. The group told Webdale they

opposed family housing because they “feared an influx of

blacks into the neighborhood.”

Another proposed site called Rockledge, located in a

predominantly white area of the Southwest, was initially

supported by the ward councilman, Dominick Iannacone.

Iannacone testified, however, that he received “flack”

from his constituents. Some complained about the loss of

the proposed site as a parking facility; others, “who knew

him better,” stated that “they didn’t want the housing

because they didn’t want any blacks there.” 624 F. Supp.

at 1321. Thereafter, concerned that he would not be

reelected if he supported Rockledge, Iannacone withdrew

his support, citing his constituents’ concern about loss of

parking. Using the informal veto power enjoyed by any

councilman in whose ward a project was proposed, he

“buried” the matter in a Council committee of which he

was chairman. At trial, he “acknowledged that his pub-

6172

licly stated reasons for opposing the project were pretex-

tual, and that his opposition in fact was in response to his

constituents’ racially influenced opposition.” Id. at 1322.

In the end, CDA’s efforts resulted in the construction

of eight low-and-moderate-income family projects; all

were in Southwest Yonkers and all were in or close to that

area’s predominantly minority neighborhoods.

Other City activities included consideration in 1969 of

subsidized housing for the relocation of 1,000 families

from Southwest to other parts of Yonkers; the City’s goal

was to ensure plant expansion space in Southwest Yonkers

for one of the City’s largest employers, which threatened

to move out of Yonkers. A private consulting firm sur

veyed 98 possible sites, 76 of which were located in East

or Northwest Yonkers. A City Council agenda noted that

consideration of sites in nonminority neighborhoods had

generated a “great deal of controversy” ; neighborhood

opposition was expressed by citizens’ committees and the

presentation of petitions by more than 3,000 residents.

Proposals from local businesses for different sites, some

“located deep in Yonkers’[s] ghetto areas,” prompted “a

passionate debate over racism.”

Alfred Del Bello, mayor of Yonkers from 1970 to 1974,

testified that he abandoned the 98-site survey and focused

instead on four sites within a five-block radius of the

predominantly minority downtown section of Southwest

Yonkers. The State Urban Development Corporation

agreed to sponsor these sites despite the known concern

of the Planning Board that the locations chosen were

inconsistent with the goal of commercial and industrial

revitalization of Yonkers; construction was begun without

consultation with the Planning Board. Del Bello testified

that he had settled on the four sites in minority areas

6173

because he “was dedicated to producing housing, and [he]

had to find a political course that would allow us to get it

constructed.” He stated that “race was definitely a con

sideration in many of the demonstrations and visible

opposition that we had.”

In 1971, HUD warned the City that Yonkers would lose

millions of dollars in federal funding unless it provided a

more balanced distribution of its subsidized family hous

ing. City efforts to find sites acceptable to HUD included

some dozen meetings in nonminority neighborhoods. One

official described these meetings as chaotic and carrying a

pervasive feeling of “strong fear” on the part of the

residents; his perception was that “racial” motivations

were “very thick in the air.”

Eventually, in 1972, the City approved construction of

334 units of subsidized housing on a site that was bor

dered on the north by a heavily minority area and on all

other sides by neighborhoods that were predominantly

white. This site was approved over the opposition of

residents of the predominantly white neighborhoods, the

only minority housing site approved over such opposi

tion. Shortly thereafter, the common view being that the

councilman in whose ward that site was located had little

chance for reelection, the councilman resigned to take an

appointed City position. In 1973, a new mayor, Angelo

Martinelli, was elected, having promised during his cam

paign to impose a moratorium on all subsidized housing

in Yonkers. The 334 units approved in 1972 were the last

subsidized housing for families constructed in Yonkers.

4. Housing Decisions in 1974-1982

In 1974, the Housing and Community Development

Act (“ 1974 Housing Act”), Pub. L. No. 93-383, 88 Stat.

6174

633 (codified, as amended, in scattered sections of 42

U.S.C.), replaced previous federal urban renewal pro

grams. Designed in part to expand housing opportunities

for minorities, this statute allowed a community, inter

alia, to receive certificates (called “Section 8 Certifi

cates”) to be distributed to eligible families or individuals

who could then choose an apartment in any participating

building and have part of the rent subsidized by the

federal government. See 42 U.S.C. § 1437f. In 1975, the

Yonkers Department of Development, an agency formed

in 1971 during HUD’s pressure for scattered sites for

public housing, applied for 100 Section 8 Certificates, 50

for senior citizens and 50 for families. HUD reserved

these certificates for the City, pending approval by the

Council.

The Council, however, refused to approve use of Sec

tion 8 Certificates by families. Two City officials who

attended a Council meeting at which the certificates were

discussed testified that many councilmen had been “con

cerned about the possibility that members of the minority

community would, in fact, seek and probably find units

on the east side of the city.”

Accordingly, during the next several years, the City

either applied for no Section 8 Certificates for families,

or applied for and received family certificates but used

few of them, or was denied further certificates because of

its nonuse of prior certificates. In 1981, after MHA, at

the urging of HUD, applied to HUD for Section 8

Certificates for both families and senior citizens, the

Council passed a resolution forbidding MHA to apply for

certificates for families. To the extent that the City

allowed minority families to use any of the family certifi

cates it had received, it referred those families only to

6175

buildings that were located in Southwest Yonkers; only

white families used certificates in East or Northwest

Yonkers.

The 1974 Housing Act also allowed a community to

receive funds for housing construction. During the period

1974 to 1979, the City built four senior citizen housing

projects using such funds. All four were in Southwest

Yonkers.

In 1975, an additional senior citizen project was pro

posed by a private developer for East Yonkers. It was

supported by the Planning Board as “well suited for

Housing for the Elderly vis-a-vis public transportation,

shopping, recreation, etc. as well as its location in the

eastern half of the city.” The developer, however, had

filed a fair housing statement with HUD, expressing his

hope to attract elderly blacks and hispanics from South

west Yonkers and achieve a 20% minority representation

in the project. Local residents opposed the project on the

ground that it contained the “seeds of a ghetto,” and the

project was killed by the refusal of the City’s Zoning

Board to grant minor zoning variances for parking, and

by the Council, which criticized the project on the

ground—squarely contradicted by the planning experts—

that it was unsuitable for senior citizen housing because,

inter alia, there was an “unsightly car lot” nearby. The

project was not built.

In June 1980, HUD advised the City that continued

receipt of federal funding would be conditioned on the

City’s taking “all actions within its control” to construct

100 units of subsidized housing for families “outside of

areas of minority concentration.” Although the City

signed a contract with HUD containing such an undertak

ing, and several sites were thereafter proposed, no such

6176

housing was built. One such site was disapproved by the

Council after receiving the “ [c]ustomary community op

position.” Three others, out of a list of 14 submitted to

HUD by CDA, were tentatively found acceptable by

HUD, but their use for low-income housing was thwarted

by Council zoning actions. For one site, the Council

approved a zoning change so that it eventually became a

shopping center instead. For another, the Council refused

to approve a zoning change to a category consistent with

development as subsidized housing. The third site tenta

tively approved by HUD was the site of School 4, which

had been closed in 1976 and remained vacant, costing the

City $40,000 to $50,000 per year in maintenance; this site

was already in a zoning category that would permit a

housing project. It was also in an area that was 98%

white. In 1979, as soon as the School 4 property was

mentioned as a possible site for low-income housing, the

Council voted to remove it from the multifamily zoning

category in order “to ‘give the community some peace of

mind.’ ” 624 F. Supp. at 1359.

In 1982, a developer expressed interest in the School 4

site for luxury condominiums priced at more than

$100,000. The Council bypassed the Planning Board and

took the unprecedented step of creating a citizens’ com

mittee, composed of five white residents of the area, to

assess proposals for the use of the property. Four of the

five committee members had no experience in planning or

zoning, and the committee was not advised to consult the

Planning Board. The committee recommended the sale

because condominiums priced at $100,000 would attract

the kind of people “that we would like to live in the

neighborhood.”

6177

Prior to Council action on the proposed sale, a council

man whose ward was near School 4 wrote his constituents

urging them to attend the Council meeting, explaining

that the NAACP opposed the sale on the ground that

low-income housing should be built instead. At the meet

ing, a videotape of which is in the record, the predomi

nantly white audience overflowed the room. The

discussion was emotionally charged, with frequent refer

ences to the effect that subsidized housing would have on

the “character” of the neighborhood. The final speaker

from the audience, a white proponent of the sale, stated

that the Bronx had been ruined when blacks moved there

and that he supported the condominium proposal because

he did not want the same thing to happen in Yonkers. The

audience responded with an ovation. During the discus

sion that followed, when one councilmember pointed out

that the current zoning of the site was inconsistent with

the condominium proposal (the Council having, as noted

above, removed the site from the multifamily zoning

category as soon as it was suggested for low-income

housing), another councilmember responded, “ ‘we will

change that zone when the concept fits the people, not

before.’ ” 624 F. Supp. at 1363.

The Council voted 11-2 to sell the site for luxury

housing. A majority of those who voted for the sale

stated that “the will of the community” should be hon

ored. Consummation of the sale has been delayed pend

ing resolution of this suit.

B. The District Court’s Findings as to Housing

After an extensive review of the evidence, Judge Sand

ruled that, in view of the “consistent and extreme”

segregative effect of the City’s actions, which catered

6178

consistently to community positions that were in signifi

cant part racially motivated, plaintiffs had sustained their

burden of proving that the segregated housing pattern in

Yonkers had been caused or exacerbated by the City’s

pattern and practice of discrimination on the basis of race

in its decisions on the location of subsidized housing. Id.

at 1369-73. He found that this pattern had begun with the

City’s first selection of subsidized housing sites under the

1949 Housing Act and had continued through its 1982

attempt to sell the School 4 property for luxury housing.

Id. at 1373.

The court rejected each of the City’s arguments that

persons and factors other than the City- had been the

cause of Yonkers’s segregated housing pattern. It found

that the cause was not HUD encouragement of subsidized

housing construction in Southwest Yonkers, id. at 1328-

30; rather, HUD had urged scattered construction sites,

and the City had repeatedly risked the loss of federal

funding by its refusal to select more widely distributed

sites, e.g., id. at 1323, 1347, 1356. Nor was the cause a

lack of private developer interest in areas outside South

west Yonkers, id. at 1330-31; CDA had sought out devel

opers only for Southwest Yonkers, id., and the City had

thwarted the efforts of a developer who sought to build

an East Yonkers project intended to attract 20% of its

residents from minority groups, id. at 1350-51. Nor could

the housing patterns be attributed to the desire of minor

ity communities for concentration of subsidized housing

in Southwest Yonkers; minority groups had begun at least

as early as 1956 to express concern about the segregative

effects of locating subsidized housing in heavily minority

areas and had expressed a desire to “hav[e] the opportu

nity to live elsewhere in Yonkers.” Id. at 1332-33. Nor was

6179

there, as the City contended, a lack of suitable sites in

East Yonkers, id. at 1333-37; some of the sites rejected by

the Council had been considered by the planners to be

“ideal,” e.g., id. at 1300.

The court also rejected the City’s argument that its site-

selection decisions were made pursuant to a race-neutral

“ legitimate planning strategy” for urban renewal, id. at

1337-42, for the City’s site selections, far from revitaliz

ing Southwest Yonkers, had brought revitalization efforts

to a halt, id. at 1310, 1337. Rather, the court found that

whenever a site was proposed for a predominantly white

area, strong community opposition emerged. Id. at 1369.

Though this opposition was not “based wholly upon

race,” race was “a significant factor,” id. at 1371 (empha

sis in original); the opposition was “based, at least in

significant part, upon fear of an influx of minorities into

what were (and remain today) overwhelmingly white

neighborhoods,” id. at 1313. The court found that “City

officials consistently responded to that opposition.” Id. at

1371. The inference that racial animus was a significant

element in the community opposition to which City offi

cials were responding was drawn from, inter alia, direct

testimony to that effect, evidence of overtly racist com

ments, the racially divided quality of private housing in

Yonkers, and a general pattern in which only sites pro

posed in the predominantly white Northwest or East

Yonkers or the white areas of Southwest Yonkers engen

dered opposition. Id. at 1311-12. The court found that

City officials “came to view racially influenced opposi

tion to subsidized housing in East Yonkers as a ‘fact of

life,’ ” id. at 1316, and made “conscious decisions” to

concentrate on “ ‘politically feasible’ ” sites, id. at 1313.

In addition, the court found that “numerous City offi-

6180

cials not only responded to, but, in the words of the

campaign literature of some, ‘led the fight against subsi

dized housing in East Yonkers.’ ” Id. at 1373.

The court found further evidence of the City’s intent to

preserve segregation in housing in its conduct with regard

to Section 8 Certificates. Its cut-off of applications for

family certificates and its failure to use any already

obtained family certificates for minority families outside

of Southwest Yonkers were found “inexplicable except by

reference to the anticipated race of the certificate hold

ers,” id. at 1347, i.e., “inexplicable except on the basis of

fear that minorities might use the certificates to relocate

to East Yonkers,” id. at 1373. Similarly, with respect to

the City’s 1982 attempt to sell School 4 for luxury

housing, the court found that the procedural innovations

and the nature of the debate made it “difficult to imagine

a clearer case of an action taken for a discriminatory

purpose.” Id. at 1363; see also id. at 1518-21.

In sum, Judge Sand concluded that “the extreme con

centration of subsidized housing that exists in Southwest

Yonkers today is the result of a pattern and practice of

racial discrimination by City officials, pursued in re

sponse to constituent pressures to select or support only

sites that would preserve existing patterns of racial segre

gation, and to reject or oppose sites that would threaten

existing patterns of segregation.” Id. at 1373. The court

emphasized that its finding of the City’s segregative intent

rested not on a failure to act, but on “a thirty-year

practice of consistently rejecting the integrative alterna

tive in favor of the segregative—a practice that had the

unsurprising effect of perfectly preserving, and signifi

cantly exacerbating, existing patterns of racial segregation

in Yonkers.” Id. at 1368.

6181

The court concluded that the conduct of the City and

CDA violated the Equal Protection Clause and that their

conduct since 1968 violated the Fair Housing Act as well.

C. The Housing Remedy

Having found the City and CDA liable for statutory

and constitutional violations, the court held a six-day

hearing as to appropriate remedies. In an order published

at 635 F. Supp. 1577 (1986) (“Housing Order”) and an

unpublished Modification to Housing Remedy Order

(“Modification Order”), dated July 8, 1986, the court

permanently enjoined the City from, inter alia, intention

ally promoting racial residential segregation in Yonkers

and ordered that certain affirmative steps be taken to

ward a wider distribution of public housing.

The court noted that the City had already committed

itself to providing sites for 200 units of public housing in

order to receive its 1983 Community Development Block

Grant (“Development Grant”) funds but had never ful

filled that commitment; the City also had entered into a

Consent Decree with HUD that provided that HUD

would reduce Development Grant funding if the City did

not submit for preapproval sites for at least 140 of the

200 public housing units. The court ordered the City to

submit an acceptable Housing Assistance Plan to HUD

and execute a grant agreement with HUD, in order to

receive the Development Grant funds for 200 units of

subsidized housing, 635 F. Supp. at 1580; Modification

Order at 2-4, and to “submit to HUD for preapproval at

least two sites for 140 [of the agreed 200] units of family

public housing,” 635 F. Supp. at 1580.

The Housing Order provided that if the City did not

submit two such sites within 30 days of the court’s order,

6182

the City would be deemed to have submitted the sites of

three closed schools in East Yonkers, /.<?., School 4,

School 15, and the Walt Whitman School, or such other

sites as might be proposed by plaintiffs and approved by

the court. Schools 4 and 15, closed in 1976, had been

returned to the City in 1982; Walt Whitman had been

closed in 1983, and the court ordered the Board of

Education to return that school to the City as well. The

court also ordered the City to submit sites selected from a

specific list for the remaining 60 public housing units. Id.

at 1581.

In addition, the court ordered the City to create an

Affordable Housing Trust Fund for the encouragement of

private development of low-and moderate-income hous

ing, to be funded initially with at least 25% of the

Development Grant funds allocated to the City by HUD.

Id. at 1581-82; Modification Order at 1-2. It also ordered

the City to establish a Fair Housing Office with pre

scribed responsibilities, to seek HUD approval for trans

fer of the administration of the Section 8 Certificate

program to MHA, and to develop a plan for more

subsidized family housing units in areas outside of South

west Yonkers. 635 F. Supp. at 1577-82.

II. School Segregation

Management and control of the Yonkers school district

were entrusted to defendant Yonkers Board of Education.

The Board, an independent municipal corporation subject

to the control of New York State’s Board of Regents and

Commissioner of Education, consisted of nine members

appointed by the mayor for staggered five-year terms. Its

budget was subject to review by the Yonkers City Coun

cil.

6183

At the liability trial, plaintiffs sought to show that

students in Yonkers schools were segregated and that that

segregation had been caused or enhanced principally by

(1) the Board’s general adherence to a neighborhood-

school policy, with awareness of the City’s practice of

maintaining segregated neighborhoods; (2) other segrega

tive actions of the Board with respect to (a) school

openings, closings, and boundary changes, (b) faculty

assignments, (c) special education classes, and (d) voca

tional programs; and (3) the Board’s failure to take any

of a number of recommended or otherwise appropriate

steps to alleviate the growing school segregation.

Plaintiffs contended also that the segregative housing

practices of the City were designed in part to achieve and

preserve segregation in the schools. They sought to show

that the City helped to maintain such school segregation

also by, inter alia, the mayor’s appointing to the Board

persons known to advocate preservation of the segregated

neighborhoods and neighborhood schools.

A. Racial Composition o f Each School’s Student

Population

As of the 1980-81 school year, Yonkers had 23 elemen

tary schools for grades K-5 or K-6; four middle schools

for grades 6-8 or 7-8; two combined elementary and

middle schools; four general academic high schools; and

one vocational high school. In a number of these schools,

special education classes were conducted for students with

learning disabilities or emotional disturbances.

1. The General Student Population

In 1980, the student enrollment in Yonkers public

schools was approximately 37% minority. The percentage

6184

of minority enrollment had approximately doubled from

1970 to 1980, due in part to an increase in minority

enrollment and in greater part to a decline in white

enrollment:

Y onkers P u b lic S c h o o l S tu d e n t P o p u la tio n

W h ite % W h ite M in o r ity % M in o r ity

1967. .. .. 25,875 85 4,421 15

1970. . . .. 25,049 82 5,583 18

1975 . . . .. 21,514 72 8,195 28

1980... .. 13,840 63 8,023 37

In 1980, only two of Yonkers’s schools, one an elemen

tary school located in Southwest and the other a middle

school in Northwest, had student populations whose

racial compositions approximated that of the system as a

whole. The next most balanced schools had student popu

lations that were, respectively, 21%, 45%, and 47%

minority. The great majority of the schools were either

disproportionately white or disproportionately minority.

At the elementary level, although 61% of the students

were white, in 19 of Yonkers’s 25 elementary schools the

student populations were either more than 80% white or

more than 80% minority. Some 85% of Yonkers’s minor

ity elementary school students attended nine schools in

Southwest Yonkers. In addition, one elementary school in

Northwest Yonkers had an 88% minority population.

These 10 schools enrolled 92% of all of Yonkers’s minor

ity elementary school students. More than 55% of

Yonkers’s minority elementary school students attended

just five Southwest schools, whose minority populations

were 75%, 81%, 90%, 98%, and 98%.

Sixteen elementary schools were located outside of

Southwest Yonkers. Of these, 14 had student populations

that were at least 90% white; more than 70% of

6185

Yonkers’s white elementary school students attended

these 90%-white schools. Of the 11 elementary schools in

East Yonkers, only one had a minority student population

of more than 7%.

In Yonkers’s middle schools, 62% of the students were

white. Two of the six middle schools were located in East

Yonkers and together enrolled only 62 minority students,

or 5% of Yonkers’s total middle school minority popula

tion; these two schools were, respectively, 94% and 96%

white. Three middle schools were located in Southwest

Yonkers and had minority student populations of 62%,

69%, and 94%. Nearly 80% of Yonkers’s middle school

minority students attended the three Southwest schools.

Another 15% attended a middle school in Northwest.

About 70% of the students attending Yonkers public

high schools, including the vocational high school (see

Part y4.II.A .3. below), were white. Of the four academic

high schools, two were located in East Yonkers, one in

Southwest, and one in Northwest. The two located in

East Yonkers had student populations that were 91% and

98% white. The high school in Southwest had a student

body that was 62% minority; it enrolled nearly two-thirds

of all Yonkers minority students attending academic high

schools.

2. Special Education Classes

The Yonkers special education program provided spe

cial classes for students with mental or physical handi

caps, including those with learning disabilities or

emotional disturbances. Beginning in the 1960’s, there

was a growing and disproportionate number of minority

students in special education classes. These classes, espe

cially those for the emotionally disturbed, were viewed by

6186

many teachers, school officials, and community members

as a “dumping ground for black children.” In general,

white children would be placed in a special class only

after having been referred first to a school psychologist

for an evaluation, then to the principal for review of that

evaluation, then to the school district’s special education

screening committee on the handicapped for a final deci

sion as to what type, if any, special program was appro

priate. A black child whose teacher considered him or her

“disruptive,” however, would often (“for the sake of

discipline”) be consigned immediately by the teacher and

the principal to a class for the emotionally disturbed,

without prior reference to a psychologist and with no

effort to determine whether other options might meet the

child’s needs.

As a result, in 1961, when regular classes in Yonkers

elementary schools had a system-wide minority popula

tion of 10%, minorities made up 22% of the special

education classes. By the 1971-72 school year, when the

system-wide minority population was 20%, the minority

children made up 40% of all special education classes and

more than 70% of the classes for those with emotional

disturbances.

Location of the special education classes did not follow

the Board’s usual neighborhood-school policy; rather,

these classes were placed in schools that had space availa

ble to accommodate them. Since most of the schools with

high minority populations tended to be more crowded,

most of the available space was found in schools having

virtually all-white student populations. The principals of

many of the latter schools resisted the placement of

special education classes in their schools for reasons that,

in the opinion of a former director of the program, were

6187

race-related. Nonetheless, most of the special education

classes were placed in schools having few other minority

students. In 1972, for example, classes for some 78% of

the children classified as emotionally disturbed were con

ducted in schools whose regular student populations were

at least 97% white. Three-quarters of the students in

these special classes were minorities.

In most of the schools, there was no mainstreaming of

the special education classes into the general school popu

lation. Because special education assignments were made

without regard to residence, the students were often

bused long distances, often well over an hour’s trip, and

sometimes up to two hours, in each direction. Thus they

arrived at school later than the regular students and

departed earlier. In some instances they entered the school

through separate entrances and were kept in classrooms

located in secluded areas of the school. In one school, for

example, they had to file down two flights below ground

and pass through a boiler room to reach their classroom

in the subbasement. Special education students also gen

erally took their lunch, gym classes, and recesses sepa

rately from the regular students. To the extent that school

officials allowed contact between the two groups, the

interaction was often purposely negative. One witness

who had been a regular student at a 98%-white elemen

tary school in the late 1960’s recalled her perception that

all special education students were black and that they

were held up to the regular students as examples of “poor,

bad behavior.” Thus the special education students were

perceived as “different” and “bad.” Another witness, a

parent and PTA president, testified that her children had

thought the words “retard” and “nigger” were inter

changeable because the children’s only knowledge of

6188

blacks was of special education students bused into their

school.

Nor was the negative reaction to special education

students limited to the school’s other students. One of the

special education teachers and coordinators testified that

parents and community members had thrown rocks at her

car and shouted “Take your niggers and get out.”

In 1972, the Board hired Dr. Gary Carman, a special

education expert, to direct the program. At trial, he

testified that Yonkers, by busing its special education

students long distances and physically segregating them

from the regular student population, “had the most

inhumane program for handicapped children [he] had

ever seen anywhere.” Dr. Carman “knew of no causes,

medical causes, social causes, biological causes that could

possibly account” for the disproportionate number of

minorities placed in the classes for the emotionally dis

turbed. The disproportionate referral of minority stu

dents to special education classes eventually prompted an

investigation by state and federal education officials. The

conclusion of the United States Department of Education

was that the Yonkers special education program subjected

minority students to discrimination and violated their

civil rights.

From 1972 to 1975, Dr. Carman attempted to improve

the special education program by reducing the amount of

busing, returning some special education students to reg

ular classes, to an extent mainstreaming the special educa

tion students into the general school population, and

reducing the incidence of virtually all-minority special

classes in virtually all-white schools. After Dr. Carman

left in 1975, however, these efforts lapsed and the system

reverted to one of long-distance busing and placement of

6189

blocs of minority special education students in virtually

all-white schools. Dr. Carman testified that where the

total experience of white children with blacks was their

exposure to those in special education classes, the white

children would view the special education children as

“less worthy” and could well “generalize that to all

blacks.”

3. Vocational High Schools

Prior to 1974, Yonkers had two specialized vocational

high schools, Saunders Trade and Technical High School

(“Saunders”), and the High School of Commerce (“Com

merce”). Saunders offered technical courses such as auto

mechanics, carpentry, and electricity; Commerce, which

was closed in 1974, offered courses such as stenography,

bookkeeping, cosmetology, food trades, and dressmak

ing. Both schools were located in Southwest Yonkers.

Neither was subject to the Board’s neighborhood policy

and each accepted students from anywhere in the City.

Although precise statistics with regard to vocational

school enrollment by race are not available for years prior

to 1967, the trial testimony indicated that, prior to 1958,

Saunders had a large minority enrollment. From the

1930’s until approximately 1958, it had a reputation as “a

school for problem kids” or for “academically retarded

pupils,” or as a “dumping ground for minority students.”

Many black students from Runyon Heights attended

Saunders or Commerce instead of Roosevelt, the school

nearest their homes, often encouraged by their guidance

counselor to do so even if they wanted an academic

program. Similar steering usually did not occur with

respect to academically undistinguished white students.

6190

In 1958, the Board decided to establish entrance re

quirements for Saunders and Commerce based on grades,

achievement and aptitude test scores, recommendations,

and discipline records. The criteria for admission were

not precise, however, and final decisions lay within the

discretion of the respective principals. Apparently these

entrance requirements had the effect of changing the

community’s perception of the schools as inferior, and by

the early 1970’s, Saunders, whose capacity was roughly

one-half that of the smallest academic high school, was

receiving nearly twice as many applications as it could

accept.

At the same time, Saunders’s minority enrollment was

decreasing substantially, due in part to the heightened

entrance requirements, the acknowledged inferiority of

the educational programs available in Southwest Yonkers

schools, the subjectivity of the school officials’ evaluation

of the applicants’ credentials, and the absence of any

effort on the part of the Board to see that minority

students, most of whom attended schools in Southwest

Yonkers, had an equal opportunity to get into Saunders.

Robert Alioto, the school system’s superintendent from

1971 to 1975, and other school district officials believed

that Saunders’s selection process “ ‘appeared to systemat

ically exclude minority youngsters.’ ” 624 F. Supp. at

1450. The Board, “though aware of the systematic exclu

sion of minorities which resulted from the Saunders

admissions process, did relatively little until the late

1970’s to eliminate the discriminatory impact of the

methods by which students were chosen.” Id. at 1452.

6191

B. Facility and Faculty Disadvantages o f the

Predominantly Minority Schools

In support of their contention that Yonkers’s segre

gated school system provided minorities with lower qual

ity education than was given to whites, plaintiffs offered

evidence of inferior and generally overcrowded facilities

at schools with high minority populations, and of high

faculty turnover and a lower overall level of teacher

experience in such schools.

1. Plant Facilities

School officials testified that adequate facilities at a

school are important not only to a student’s physical

development but also to his ability to benefit from the

instructional aspects of the educational process. Inade

quate physical facilities, including space for recreation,

can cause disciplinary problems and cause the community

to perceive the school as inferior. According to Alioto,

the Southwest Yonkers schools “had probably the worst

facilities that one could imagine.”

The predominantly minority schools had smaller build

ings and sites, particularly in the amount of playground

and recreation areas for each school, than the predomi

nantly white schools. For example, the site size of the five

most heavily minority elementary schools averaged 1.83

acres; the average site size of the nine most heavily white

elementary schools was 4.84 acres. At the minority

schools averaging 1.83 acres, the average school popula

tion was 413 students. At the white schools averaging 4.84

acres, the average school population was 308 students.

The three predominantly minority middle schools, all

in Southwest Yonkers, were located on property totaling

7.2 acres. The two predominantly white middle schools

6192

located in East Yonkers were on a total of 19 acres. The

total number of students attending each group of schools

was nearly identical: 1299 in the Southwest schools, and

1312 in the East Yonkers schools. During the 1970’s,

crowded conditions forced one Southwest middle school

to use storage closets as classrooms.

The 62% minority high school in Southwest Yonkers

was located on 8.0 acres. The high school in Northwest

Yonkers, 47% minority, was located on 6.38 acres. The

two high schools in East Yonkers, averaging 95% white

student populations, were located on 12.64 and 23.41

acres respectively. A total of some 350 fewer students

attended these two East Yonkers schools than attended

the Northwest and Southwest schools.

2. School Staffing

Educators testified that it is generally desirable for a

school to have a balance of experienced and newer teach

ers on its faculty and for its staff to be relatively stable

from year to year. Relatively high rates of turnover and

low levels of faculty experience are factors that contribute

to a school’s lower level of educational effectiveness. The

evidence regarding the Yonkers public school system re

vealed that the predominantly minority schools in South

west Yonkers had low levels of faculty stability, lower

levels of teacher experience than the system-wide average,

and produced the students with the lowest academic

achievement test scores in the system. These schools also

had much higher than average concentrations of minority

staff as a result of a Board practice of race-based assign

ments.

The first minority teachers employed by the Yonkers

school system, hired between 1946 and 1950, were as-

6193

signed to School 1, then the only predominantly minority

school in the system (91% minority student population in

1950). Until the late 1960’s, the system had few minority

teachers and no minority principals. The Board then

began to recruit minorities, and the number of minority

staff members (i.e., teachers, principals, and assistant

principals) rose from 95 in 1967 (out of a total of 1416),

to 174 by 1975. Consistently over the years, most of the

minority staff members were assigned to the schools

having the highest percentages of minority students. For

example, in the 1967-68 school year, Yonkers had 28

elementary schools; seven of the eight with the highest

percentages of minority students were assigned 40% of

the minority staff members. In the 1972-73 school year,

Yonkers had 30 elementary schools, including six whose

student populations were predominantly minority. The

Board assigned 61% of its minority staff members to

these six schools. In the 1975-76 school year, Yonkers had

31 elementary schools, including nine whose minority

student populations ranged from 60% to 98%. These

schools enrolled 29% of all elementary students; they

were assigned 75% of all elementary level minority teach

ers.

Similar patterns were evident in the middle and high

schools. For example, in the 1972-73 school year, Yonkers

had seven middle schools; the three that had the highest

percentages of minority students had 34% of the City’s

total middle school enrollment but were assigned 69% of

the Board’s middle school minority staff members. In

1975-76, the City had eight middle schools; the four

having the highest percentages of minority students,

though enrolling only 43% of all middle school students,

had assigned to them 81% of all middle school minority

teachers.

6194

The Board followed a similar practice in its assign

ments of minority principals. For example, at the elemen

tary level in the 1973-74 school year, the City had six

minority principals; four were assigned to schools whose

minority student populations ranged from 68% to 96%.

In the 1974-75 and 1975-76 school years, the City had five

minority elementary school principals; in 1975-76 it also

had one minority assistant principal; all of these persons

were assigned to schools having minority student popula

tions of 66% or higher.

While at no time was the faculty of any Yonkers school

predominantly staffed by minority teachers, the dispro

portionate assignment of minority staff to schools having

predominantly minority student populations increased the

identification of those schools in terms of race. And to

the extent that minority teachers were assigned to the

virtually all-white schools of East Yonkers it was often to

teach the special education classes, which themselves had

become known as dumping grounds for minority stu

dents. The minority special education teachers “were

deliberately assigned to such schools because of the dis

proportionate number of minority students in Special

Education classes.” 624 F. Supp. at 1465.

Not surprisingly, in view of the assignment of a dispro

portionate number of the more recently hired minority

teachers to the predominantly minority schools, the aver

age level of teaching experience at those schools was

usually lower than the system-wide average. In the year