Holden v. Owens-Illinois, Inc. Brief of Respondent in Opposition to Petition for Certiorari

Public Court Documents

November 14, 1986

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Holden v. Owens-Illinois, Inc. Brief of Respondent in Opposition to Petition for Certiorari, 1986. cb2d354f-b89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c34f46d9-23d4-460b-90b2-0114e6c1d02b/holden-v-owens-illinois-inc-brief-of-respondent-in-opposition-to-petition-for-certiorari. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

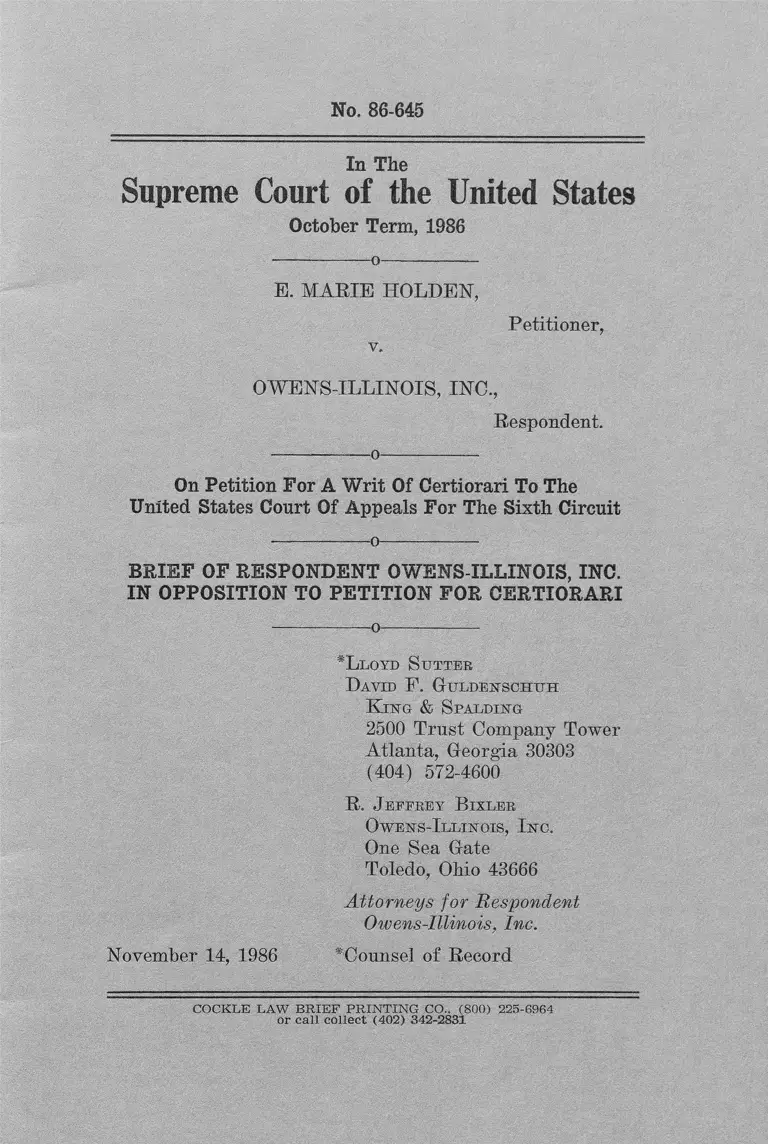

No. 86-645

In The

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1986

------------- o---------*—

E. MARIE HOLDEN,

Petitioner,

v.

OWENS-ILLINOIS, INC.,

Respondent.

------------- o-------------

On Petition For A Writ Of Certiorari To The

United States Court Of Appeals For The Sixth Circuit

— — - .....- ......- o — ------------- ------------ ----

BRIEF OF RESPONDENT OWENS-ILLINOIS, INC.

IN OPPOSITION TO PETITION FOR CERTIORARI

----- --------- o------- ------

*L loyd S u t t e e

D avid F. G u l d e n s c h u h

K in g & S pa ld in g

2500 Trust Company Tower

Atlanta, Georgia 30303

(404) 572-4600

R. J e f f r e y B ixler ,

O w e n s - I l l in o is , I n c .

One Sea Gate

Toledo, Ohio 43666

Attorneys for Respondent

Owens-Illinois, Inc.

November 14, 1986 ^Counsel of Record

COCKLE LAW B R IE F P R IN T IN G CO., (800) 225-6964

o r c a ll co llec t (402) 342-2831

1

QUESTIONS PRESENTED

1. Does there exist any inter-circuit conflict with

respect to the narrow issue raised in this appeal, i.e.,

whether Section 704(a) protects “ opposition” to prac

tices voluntarily undertaken by Federal contractors pur

suant to Executive Order No. 11246 and government “ af

firmative action” regulations promulgated thereunder?

2. Should an employee, claiming discharge for “ op

position” to practices governed by Executive Order No.

11246 and government regulations, he “ protected” from

discharge by Section 704(a) of Title VII?

11

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

QUESTIONS PRESENTED ..................................... i

TABLE OF CONTENTS ........................................... n

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES ..................................... iv

STATEMENT OF THE CASE .................................. 2

A. Proceedings Below ............. 2

B. Statement of the Facts .................................. 4

REASONS FOR DENYING THE W R IT ................. 13

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ..... 13

ARGUMENT ................................................................ 14

I. NO INTER-CIRCUIT CONFLICT EXISTS ... 14

A. The Decision of the Court of Appeals Does

Not Conflict with Those of Other Circuits

Concerning the Standard for Establishing a

Section '704(a) Violation ................................ 14

B. The Court of Appeals’ Interpretation of the

Scope of Section 704(a) In This Case Was Ap

propriate and Consistent With the Only De

cisions Involving Similar Subject Matter ... 19

II. THIS CASE DOES NOT PRESENT IMPORT-

A N T QUESTIONS CONCERNING THE

SCOPE OF SECTION 704(a) .......................... 21

A. No Issue of National Importance Exists

Which Necessitates Expansion of the Scope

of Section 704(a) Because Relief is Already

Provided for Under the Executive Order

Program ........................................................... 21

B. Expansion of Section 704(a) to Provide “ Ab

solute Immunity” For Affirmative Action

Program Fiduciaries Will Itself Adversely

Effect, Not Enhance, Achievement of Execu

tive Order No. 11246 Objectives ................... 23

Ill

TABLE OF CONTENTS—Continued

Page

III. THE COURT OF APPEALS’ DECISION IS

CONSISTENT WITH THIS COURT’S DE

CISION IN PULLMAN-STANDARD v. SWINT 25

CONCLUSION.............................................................. 26

APPENDIX ............................................................ App. 1

IV

Cases

Berg v. La Crosse Cooler Co., 612 F.2d 1041 (7th

Cir. 1980) .................................................................... 16

Emporium Capwell Co. v. Western Addition Com

munity Organisation, 420 U.S. 50 (1975) ................ 22

Gifford v. Atchison, Topeka and Santa Fe Railway

Co., 685 F.2d 1149 (9th Cir. 1982) ............................ 17

Hicks v. ABT Associates, Inc., 572 F.2d 960 (3d

Cir. 1978) .................................................................... 21

Eochstadt v. Worcester Foundation for Experi

mental Biology, 545 F.2d 222 (1st Cir. 1976) .......... 18

Holden v. Commission Against Discrimination of

the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, 671 F.2d

30 (1st Cir.), cert, denied 459 U.S. 843 (1982).......... 11

Jones v. Flagship International, 793 F.2d 714 (5th

Cir. 1986) .................................................................. 19,24

Love v. Re/Max of America, Inc., 738 F.2d 383

(10th Cir. 1984) ....................................................... 16,17

Monteiro v. Poole Silver Co., 615 F.2d 4 (1st Cir.

1980) ........................................................................... 18

Parker v. Baltimore and Ohio Railroad Co., 652

F.2d 1012 (D.C.Cir. 1981) ......................................... 17

Payne v. McLemore’s Wholesale & Retail Stores,

654 1 ’.2d 1130 (5th Cir. 1981) ................................... 16

Pullman-Standard v. Swint, 456 U.S. 273 (1982) ....... 25

Rosser v. Laborer’s International Union, 616 F.2d

221 (5th Cir.), cert, denied 449 U.S. 886 (1980) .....20, 24

Rucker v. Higher Educational Aids Board, 669

F.2d 1179 (7th Cir. 1982) ......................................... 16

Sias v. City Demonstration Agency, 588 F.2d 692

(9th Cir! 1978) .................. ...................................... 17, 21

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Page

V

Sisco v. J.S. Alberici Construction Co., 655 F.2d

146 (8th Cir. 1981)........................ ............................ 16

Smith v. Singer Co., 650 F.2d 214 (9th Cir. 1981).......16,19,

21, 24

United Steelworkers of America v. Weber, 443 U.S.

193 (1979) .....................................................-............4,17

Texas Department of Community Affairs v. Bun

dine, 450 U.S. 248 (1981) ...... '................................... 18

United States Postal Service Board of Governors

v. .likens. 460 U.S. 711 (1983)................................... 18

Whatley v. Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit

Authority, 632 F.2d 1325 (5th Cir. 1980)................. 19, 20

Wrighten v. Metropolitan Hospitals, Inc., 726 F.2d

1346 (9th Cir. 1984) .................................................. 21

S tatutes

Civil Rights Act of 1964, as amended,

42 U.S.C. § 2000e

Section 703(a), 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(a) ................. 2

Section 703(j), 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-2(j) ................... 17

Section 704(a), 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-3(a) .......... passim

Section 706(g), 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(g) ................. 2

42 U.S.C. § 1981 ...... ...................................................... 21

National Labor Relations Act, Section 8(a)(4),

29 U.S.C. § 158(a)(4) ................................................ 22

Fair Labor Standards Act, Section 15(a)(3),

29 U.S.C. §215 (a) (3) ................................................ 22

Occupational Safety and Health Act,

Section 11, 29 U.S.C. § 660 ....................................... 22

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Continued

Page

V I

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES—Continued

Page

R egula tio n s

Executive Order No. 11246 .................................... passim

41 C.F.R. Part 60-1................................................ passim

§60-1.32 .................................................................. 21

41 C.F.R. Part 60-2 (“ Revised Order No. 4” ) ........ passim

§60-2.11 .............................................................6,17,23

§60-2.12 ......................................................... 6,7,17,23

§ 60-2.30 .................................................................. 7,17

41 C.F.R. Part 60-30 ....................................................18, 23

41 C.F.R. § 60-60.2a....................................................... 9

R u les

Rule 52(a), Fed. R. Civ. P ............................................. 25

No. 86-645

- -------- o------------- -

In The

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1986

-------- ------ o---- ——-—-

E. MARIE HOLDEN,

Petitioner,

v.

OWENS-ILLINOIS, INC.,

Respondent.

------------- o-------——

On Petition For A Writ Of Certiorari To The

United States Court Of Appeals For The Sixth Gircuit

----- --------o-------------

BRIEF OF RESPONDENT OWENS-ILLINOIS, INC.

IN OPPOSITION TO PETITION FOR CERTIORARI

—---- ------o-------------

Respondent, Owens-Illinois, Inc. (“ Owens” ),* prays

that the Writ of Certiorari sought by petitioner, E. Marie

Holden (“ Ms. Holden” ), be denied because the Sixth Cir

cuit correctly held as a matter of law that Owens dis

charged petitioner for statutorily “ unprotected” activity.

-------------------------------------o — — ----------- —

* Owens-Illinois, Inc. has listed in the Appendix hereto its

subsidiaries, other than wholly-owned subsidiaries, and affili

ates, as required by this Court's Rule 28.1.

1

2

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

A. Proceedings Below

This case involves, for purposes of the instant re

view, a single issue: whether petitioner was discharged be

cause she opposed practices by her employer made unlaw

ful by Title VII. Section 704(a) of Title YII of the Civil

Rights Act of 1964, as amended, 42 U.S.C. '§2000e-3(a)

(“ opposition clause” ).1

In its decision on liability entered July 25, 1984, the

district court made no specific findings either identifying

any Owens’ practices (actual or perceived) which were

made unlawful by Title VII that were opposed by peti

tioner or connecting causally her discharge and any pro

tected opposition activity. On the other hand, the district

court did make specific findings as to petitioner’s unsat

isfactory behavior: “ her zeal to do the work she was em

ployed to do tended to make [her] more rigid and unyield

ing in her demands than she perhaps should have been”

(Petitioner’s Appendix—Pet. App. 26a-27a) ; “ with more

1 This statute reads in relevant part:

"It shall be an unlawful employment practice for an em

ployer to discriminate against any of his employees . . .

because he has opposed any practice made an unlawful

employment practice by this title" (Emphasis added).

Employer unlawful employment practices are specified in 42

U.S.C. §20Q0e-2(a); and, if a court finds an employer has in

tentionally engaged in such unlawful practices because of race,

color, religion, sex, or national origin, but not for any reason

other than Title VII prohibited discrimination, the court may

grant equitable relief. 42 U.S.C. § 2000e-5(g).

The "remedy phase" decisions of the district court, in

cluded at Pet. App. 20a-53a, were not considered by the court

of appeals (see Pet. App. at 5a) and, therefore, should not be

reviewed by this court.

3

zeal than good judgment, [she] moved aggressively to get

action” (Pet. App. 32a); against supervisory instructions,

she cancelled a scheduled plant management-community

leaders meeting and failed to return home in time to

confer with her supervisor before he went out of town

(Pet. App. 30a); and she sought an immediate meeting

in his absence with her supervisor’s superiors to clarify

the Company’s “ commitment” to affirmative action (Id.).

Finally, notwithstanding the finding that petitioner’s dif

ficulties arose almost exclusively from the trip to Shreve

port “ to set up an affirmative action program” (Pet.

App. 28a), the district court made several conclusory

findings as to its opinion of certain Owens’ practices

which were not the subject of any opposition by peti

tioner, and which were not supported by any evidence

of record (Pet. App. 31a-32a).

On appeal, Owens made essentially two arguments:

first, the district court failed to make any specific findings

to support its conclusion that petitioner had been dis

charged for opposing any Owens practices “ made unlaw

ful by [Title VII] ” ; and, even if petitioner was terminated

because she aggressively and zealously sought to imple

ment an affirmative action program which would comply

with Executive Order No. 11246, her actions did not con

stitute “protected conduct.”

Confronted with no specific findings of fact on the

critical Section 704(a) “ opposition” elements, the court of

appeals examined the transcript, the record, and the dis

trict court opinion in search of a factual basis on which

the district court might have decided petitioner’s Section

704(a) claim, i.e., some opposition by petitioner to specific

practices of Owens made unlawful by Title VII (Pet. App.

6a-7a). The appellate court, by reference to the district

court opinion itself, concluded:

4

“The district court held that Owens discharged plain

tiff because she aggressively sought to do her job and

that the discharge violated 42 TJ.S.C. § 2000e-3(a),

the ‘opposition clause’. . . . We hold that plaintiff’s

attempts to implement affirmative action plans which

would comply with Executive Order No. 11246 do

not qualify as protected activity under the opposi

tion clause.”

Pet. App. at 2a; see also id. at 8a. The basis of the court

of appeals decision was that any alleged failure by Owens

to implement its affirmative action plans did not and

could not violate Title VII, a principle which this Court

clearly articulated in United Steelworkers of America v.

Weber, 443 U.S. 193, 204-08 (1979). Petitioner, as a mat

ter of law, simply never engaged in opposition to conduct

made unlawful by Title VII.

In addition to holding that the subject matter of

petitioner’s opposition was unprotected by Section 704(a),

the court of appeals also held as a matter of law that, on

the findings made by the district court and the record

considered as a whole, petitioner “never proved, by a

preponderance of the evidence, that the legitimate rea

sons that Owens offered for her termination were but a

pretext for retaliation” (Pet. App. 17a). Accordingly,

the Sixth Circuit reversed the district court’s decision

and remanded the case with instructions that petitioner’s

complaint be dismissed (Pet. App. 2a, 19a).

It is this decision of the court of appeals which pe

titioner, opposed by Owens, asks this Court to review on

writ of certiorari.

B. Statement of the Facts

Ms. Holden was employed by Owens to be its Manager-

Equal Opportunity Affirmative Action Programs (De-

5

fendant’s Trial Exhibit—Def. Ex. 0), a position she knew

from her pre-employment interview was responsible solely

for development and implementation of Executive Order

No. 11246 affirmative action plans (“ AAPs” ) which

would comply with Revised Order No. 4, the regulation

issued by the Federal contract compliance agency gov

erning the form and contents of such AAPs (Trial Tran

script—Tr. 73-74). Her direct supervisor, Mr. Anthony,2

had advised her during her interview that he wanted an

experienced person who was fully qualified to develop

AAPs in compliance with the Executive Order program,

not a “ trainee” (Tr. 75-76, 588-89). Ms. Holden assured

Mr. Anthony that she was familiar with the Executive

Order and regulations and knew what she was doing

(Tr. 75-76), even though she had intentionally misrep

resented her experience and had falsified her employment

history.3

Mr. Anthony was Manager, Equal Opportunity. He super

vised Ms. Holden and another employee in a parallel position

whose responsibilities were exclusively confined to the han

dling of EEO discrimination charges and complaints (Def. Ex. O;

Tr. 86-87, 628-29). Mr. Anthony reported to Mr. Chadwell, a

black male who was director of the department (Def. Ex. O;

Tr. 585-86).

3 Owens was approached by an employment agency on pe

titioner's behalf (Def. Ex. J) and interviewed her after she had

completed a pre-employment application form (Def. Ex. M).

She misrepresented her experience to Owens as having in

cluded Revised Order No. 4 AAP work. The amendments to

Revised Order No. 4 initially requiring "utilization analyses"

and "goals and timetables" were promulgated in 1972. See

41 C.F.R. § 60-2.32. From 1970 to 1973 Ms. Holden was

a public information officer for the Massachusetts Commission

Against Discrimination (MCAD), about which employment she

never informed Owens and from which organization she was

discharged, see n. 9, infra; was then unemployed for about a

(Continued on following page)

6

In order to understand the job Ms. Holden was em

ployed to perform, this Court must focus on the require

ments of an Executive Order No. 11246 affirmative action

plan. For non-construction contractors, these require

ments are established in Executive Order No. 11246,

particularly Section 202(a), in 41 C.F.E. Part 60-1, and in

41 C.F.E. Part 60-2 (“ Revised Order No. 4” ), particularly

the requirements for development of the technically com

plex “ work force analyses,” “ job groupings,” “ utiliza

tion analyses,” and “ goals and timetables” specified in

41 C.F.R. §§ 60-2.11 and 60.2.12.4 These are the essential

(Continued from previous page)

year; and later worked during 1974-75 as a community affairs

consultant for Supermarkets, Inc. (Tr. 16-20, 66-67, 71). She

admitted that Supermarkets was not a Federal contractor and

that she had never developed a Revised Order No. 4 AAR

(Tr. 241-42). Notwithstanding the district court's “findings" to the

contrary (Pet. App. 24a-25a), Ms. Holden was not qualified to

perform the job for which Owens hired her, although the court

of appeals did not address this question.

4 In 41 C.F.R. §60-2.11 (a), the contractor is required to

prepare a "work force analysis," i.e., distribution by race and

sex of employees by job classification; next, it is required to

categorize into “job groups" those classifications “having sim

ilar content, wage rates and opportunities," 41 C.F.R. § 60-2,11

(b); then it is required to perform eight factor analysis statis

tical comparisons between minority and female composition

in the particular job groups with relevant internal or external

(e.g., U.S. Census and other information) “availability" data to

determine whether the business unit's work force either over

utilizes or underutilizes minorities or women, 41 C.F.R. § 60-

2.11(b)(1) (minority utilization factors) and 60-2.11 (b)(2) (female

utilization factors). After compiling this information, the con

tractor is then required to adopt voluntary “goals and time

tables" to correct its minority and female utilization deficiencies.

It is important to note that the OFCCP regulations provide:

'T l]n establishing the size of its goals and the length of its

timetables, the contractor should consider the results which

(Continued on following page)

7

elements of an AAP without which a contractor is pre

sumed by the U.S. Department of Labor, Office of Fed

eral Contract Compliance Programs (“ OFCCP” ) to be

in noncompliance status. See 41 C.F.R. §60-1.40(a) and

(b). The additional requirements of an AAP are set

forth in 41 C.F.R. § 60-2.13.5

Prior to Ms. Holden’s arrival in November of 1975,

Owens had developed its own Procedure Manual describ

ing in detail the content and format for its AAPs (Tr. 593

and Def. Ex. Y). Owens also had already developed and

annually “ critiqued” or updated AAPs for its headquar

ters and its over 100 field units. (Tr. 591-93).6 The “ cor

porate headquarters AAP”, moreover, had previously

been determined by the responsible Federal enforce

ment agency to comply with the requirements of Re

vised Order No. 4 (Tr. 592; see also Plaintiff’s Trial Ex-

(Continued from previous page)

would reasonably be expected from its putting forth every

good faith effort to make its overall affirmative action pro

gram work."

41 C.F.R. § 60-2.12(a); see a Iso §§ 60-2.12(c) ("goals should be

significant, measurable, and attainable"), 60-2.12(e) ("may not be

rigid and inflexible quotas . . ., [rather] targets reasonably

attainable . . ."), 60-2.12(f) (work force expansion, contraction,

and turnover are to be considered), and 60-2.30 (goals are not

to he used to "reverse discriminate").

Although the district court took judicial notice of the

Executive Order and OFCCP regulations (Tr. 21), the decision on

liability completely ignored the Order and regulations, as well

as the existence of any distinction between Title VII discrim

ination and voluntary Federal contractor affirmative action ob

ligations.

6 See 41 C.F.R. §§ 60-1.40(c) and 60-2.14. During a com

pliance review, the government regularly reviews the immedi

ate past year's AAP against the current AAP to ascertain what

utilization improvements were possible and were achieved.

41 C.F.R. §§ 60-1.20(a), 60-2.10, 60-2.12(a), 60-2.14 (Tr. 591-92;

Def. Ex. AR through AZ).

8

Mbit—PL Ex. 2); and, though subsequent to her discharge

and due in no part to her efforts, the Shreveport plant

AAP was also found by the government to be in compli

ance (Tr. 592; see Def. Ex. AY).

During her brief tenure, Ms. Holden was given only

three specific work assignments: critiques7 of the existing

Bridgeton and Waco plant AAPs for compliance with Re

vised Order No. 4 (Tr. 593-95, 606) and development “from

scratch” of an AAP for the Shreveport plant (Tr. 596).

The latter assignment was required because, as a new plant

(Tr. 496, 498), Shreveport did not have an AAP yet; and,

under the applicable regulations, 41 C.P.R. § 60-1.40(c),

one had to be developed within 120 days after startup.

Ms. Holden was unable to critique either the Bridge-

ton or Waco AAPs (Tr. 595-96, 606). More importantly,

though, the manner in which she undertook development

of the Shreveport plant AAP, i.e., in an adversarial fash

ion, acting like a “ Federal compliance agent,” rather than

as a technical advisor to plant management, was what

caused the difficulties between Ms. Holden and Owens

(Tr. 432-33, 481, 490-91, 510-11, 599, 601-02).

All of Ms. Holden’s problems at Shreveport involved

differences of opinion about what information she needed

and how fast the plant personnel should supply it so she

could prepare the AAP. On her first day at the Shreve

port plant, Ms. Holden had a plant tour, met the plant

manager, went to lunch with a friend from another com

pany, and spent the afternoon at the state employment

service getting area labor force statistical data (Tr. 152-54,

7 Mr. Anthony described a "critique" as a section-by-section

analysis of an existing AAP to determine whether its form and

content met the requirements of Revised Order No. 4 (Tr. 595).

9

157-58, 292-93). The next two days she spent -working

at the plant, analyzing documents and other information

on workforce composition and other employment related

information supplied by the plant (Tr. 305-07). Ms. Hol

den thought she had not been given certain employee salary

information, but the evidence and plant representatives’

testimony reflect otherwise (Tr. 308-09, 424-26, 491-92;

PL Ex. 13). Some of the information demanded by peti

tioner (see Def. Ex. S) could not be immediately or easily

developed, the plant personnel director and his secretary

explained (Tr. 424, 477-98). To assist Ms. Holden in the

information compilation task, however, the plant hired and

assigned to her a temporary employee (Tr. 431-33).

Ms. Holden called Mr. Anthony to say that the plant

was not cooperating with her in terms of producing im

mediately some of the information she said she needed

(Tr. 509-510, 599-600). Mr. Anthony advised her:

“ Well, that data could be sent to you after you get

back. You know you don’t have to insist on having

it prepared right then and there . . . . [JJust inform

them what you want and then they would send it in

[to Toledo].”

(Id.)* When petitioner’s continuing demands created a

stalemate, she was asked to return to Toledo (Tr. 510-11,

601-02).

After he informed her to return to Toledo, Mr. An

thony gave Ms. Holden two specific instructions: (1) pro-

Even government compliance officers do not demand in

stant production of information. See, e.g., OFCCP Revised Or

der No. 14, 41 C.F.R. § 60-60.2(a) (30-day return deadline).

10

ceed to meet, as scheduled, that afternoon with the per

sonnel director and various community leaders (Tr. 171-

73, 603); and (2) return to Toledo the next day in time

to meet with him because he would be out of town on the

following two days (Tr. 173, 603-04). Ms. Holden did

neither. She immediately cancelled the scheduled meeting

with community leaders. Moreover, she intentionally de

layed returning to Toledo until Mr. Anthony had left town

(Tr. 172-76, 603). And, after she returned, petitioner

wrote a memorandum to Mr. Anthony’s superiors request

ing in his absence an immediate meeting to clarify the Com

pany’s “ EEO policy/affirmative action commitments” and

to discuss her “ Shreveport plant visitation” (Def. Ex. U).

When Ms. Holden’s supervisor returned to Toledo, he

chastised her for intentionally disregarding his instruc

tions and for attempting to embarrass him in his absence

by writing her memorandum to his superiors (Tr. 605-06).

He advised her that he had serious doubts about her com

petence and gave her the Waco AAP to critique by the end

of that workday (Id.). Ms. Holden, however, left the office

soon thereafter and did not return (Tr. 341). She never

completed the Waco AAP assignment and she failed to

report for work the next day.

Her supervisor made several unsuccessful attempts

to contact her by telephone at home the next day (Tr 606).

He then prepared a meorandum to her specifying his con

cerns and promising to take appropriate action upon her

return (Id. ; Def. Ex. U). When he learned while at lunch

11

with his supervisor of Ms. Holden’s earlier mistreatment

of a black staff secretary,9 Mr. Anthony decided simply to

terminate her {Id.; see also Tr. 562). He wrote Ms. Hol

den’s dismissal notice upon return from lunch and mailed

it to her that day (Tr. 606-07; Def. Ex. V).

In her pretrial statements and testimony, Ms. Holden

predicated her claim, not on Owens’ allegedly discrimina

tory treatment of her personally or any other specific in

dividual, but rather on what she perceived to be a lack

of commitment by Owens as to its affirmative action obli

gations. Contrary to her pre- and post-employment in

structions, Ms. Holden admitted that she intended to act

like a “ compliance officer,” rather than someone whose

job it was to assist managers to develop and update their

AAPs to comply with Revised Order No. 4 and the Com

pany’s AAP Procedure Manual (Tr. 278-79).

Ms. Holden was discharged because of her disagree

ments with Owens as to how the Company’s AAPs should

be developed and implemented, as well as the adversarial

manner in which she had gone about her affirmative action

The district court, Owens argued on appeal, improperly

excluded the evidence on the secretary incident and refused to

consider any evidence concerning the reasons for Ms. Holden's

termination by MCAD, both indications Owens contended of

petitioner's reluctance to accept supervisory direction and

tendency to abuse staff personnel (Tr. 341-88, 574-80; deposition

of Sharon Savage and Def. Ex. D, E, and I as Offer of Proof).

See also Holden v. Commission Against Discrimination of the

Commonwealth of Massachusetts, 671 F.2d 30 (1st Cir.), cert.

denied 459 U.S. 843 (1982), affirming the district court decision

sustaining her MCAD discharge for, among other things, be-

haviorial characteristics similar to those she exhibited while em

ployed by Owens. The court of appeals never addressed this

evidentiary issue.

12

manager’s job (Tr. 601-06; Def. Ex. IT and V). The dis

trict court clearly so found, i.e., she went to Shreveport

“ to set up an affirmative action program” (Pet. App.

28a) and her aggressive and overzealous behavior was ad

dressed exclusively to that objective (Pet. App. 28a-32a).

Notwithstanding its specific findings that petitioner ’s

“ opposition” and related behavior was solely addressed

to affirmative action subject matter, the district court also

made several conclusory findings which were neither the

subject of any specific opposition by petitioner, nor sup

ported by any evidence in the record:

“ . . . [Owens’] employment practices were in many

respects discriminatory, especially as to race, but also

as to gender. It had been following the common prac

tice of window dressing by token employment of mi

nority individuals, rather than seriously trying to

change its methods and to remedy the results of its

past discriminatory actions. ’ ’

(Pet. App. 31a-32a). Aside from the workforce composi

tion of petitioner’s own department (75% black) and evi

dence contained in the two AAPs—“ corporate headquar

ters” and Shreveport plant, both of which were found to

be in compliance with Executive Order No. 11246—the rec

ord contained no evidence on the basis of which the dis

trict court could make such conclusory findings. But, most

important, the foregoing observations were those of the

district court, not petitioner; and those “ findings” were

not subject matter about which she raised any specific

opposition, nor were they the “ opposition” activity causal

ly connected with her discharge.

The record and district court findings simply show no

opposition on petitioner’s part to any practices by Owens

13

which either were or even arguably could have been per

ceived to be Title VII violations (Pet. App. 24a, 28a-32a).

Hence, the court of appeals was correct as a matter of law

in its conclusion, on the record and findings of fact, that

petitioner had engaged in no Section 704(a) protected

opposition and that she had failed to prove that her termi

nation was a pretext for retaliation (Pet. App. 2a, 8a, 16a-

17a).

------------- o------------- -

REASONS FOR DENYING THE WRIT

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The Sixth Circuit held that the district court failed to

make any specific findings with respect to what practices

Owens had engaged in, and that Petitioner had opposed,

which were unlawful under Title VII. It could locate no

evidence in the record from which the district court could

have made any such findings. Therefore, it held that Ms.

Holden’s “ opposition” related to subject matter, i.e., the

company’s lack of commitment to affirmative action under

Executive Order No. 11246 and applicable regulations and

her desire to act as a “ compliance officer,” which was un

protected by Section 704(a) of Title VII.

This appellate court decision is not in conflict or in

consistent with any of the authorities upon which petitioner

relies. In fact, it is completely consistent with decisions of

the Fifth and Ninth Circuits involving EEO specialists

whose opposition activities “ disabled” them from per

forming the jobs for which they had been hired.

Likewise, this case raises no issue of national im

portance which would justify judicial expansion of the

14

scope of Section 704(a); and, contrary to petitioner’s as

sertion, to protect activities such as Ms. Holden’s would

adversely effect, not enhance, OFCCP’s accomplishment of

Executive Order No. 11246’s legitimate objectives by in

hibiting the ability of employers to establish voluntary

AAPs in the manner they, not their EEO specialists, de

termine to be appropriate.

Finally, the court of appeals made no de novo find

ings of fact. It decided this case as a matter of law

either on the findings made by the district court or, where

such were lacking, on the record which permitted only

one resolution of the factual issue.

-------------- 0---------------

ARGUMENT

I.

NO INTER-CIRCUIT CONFLICT EXISTS

A. The Decision of the Court of Appeals Does

Not Conflict with Those of Other Circuits

Concerning the Standard for Establishing a

Section 704(a) Violation

Petitioner mistakenly argues (Petition—Pet. at 22)

that the Sixth Circuit held that, in order to prevail in a Sec

tion 704(a) action, she had to prove an actual violation

of Title VII, rather than a “reasonable belief” that some

particular employer practice was unlawful under Title

VII. That is not what the court of appeals held at all.

Rather, the Sixth Circuit held:

“Since Title VII does not require the adoption of

affirmative action programs, to the extent that [pe-

15

titioner] sought to implement an affirmative action

plan which would comply with Executive Order No.

11,246, [she] was not opposing a practice that vio

lated Title VII. Consequently, the District Court

erred in treating [petitioner’s] attempts to implement

an affirmative action program which would comply

with Executive Order No. 11,246 as protected conduct

under the ‘opposition clause’.”

(Pet. App. 8a; see also Pet. App. 2a and 17a).

None of the decisions relied upon by petitioner are

in conflict with the Court of Appeals’ decision in this case.

The Sixth Circuit simply held that a perceived violation

of Title VII under an undisputed set of facts is protected

by Section 704(a) only if those facts, if true, establish

a Title VII violation. In this case, even if the conduct

which petitioner “opposed” was true, that is, that Owens

was not satisfying its affirmative action commitments,

such conduct did not constitute a violation of Title VII.

Petitioner could not, therefore, as a matter of law, estab

lish opposition to conduct perceived to be a violation of

Title VII.

Regardless of how particular appellate courts have

phrased the “reasonable belief” standard, the same three

elements are required to establish a prima facie case:

1. “opposition” to some specific conduct or practice

of the employer which is a violation of Title VII,

i.e., discriminatory on the basis of race, color,

religion, sex, or national origin;

2. adverse action against the employee; and

3. a “causal connection” or “linkage” between the

protected “opposition” and the adverse personnel

action.

16

See, e.g., Payne v. McLemore’s Wholesale & Retail

Stores, 654 F.2d 1130, 1136 (5th Cir. 1981) and Love v.

Re/Max of America, Inc., 738 F.2d 383, 385 (10th Cir.

1984). The district court acknowledged this standard

(Pet. App. at 36a-37a), hut then failed to render any

findings with respect to what specific Title YII “pro

tected” opposition was causally connected with petition

er’s discharge.

In addition, however, petitioner’s case differs sub

stantially from all of the authorities she cited for at least

three reasons.

First, her job circumstances differed substantially

from those of the employees involved in the decisions on

which she relies. Ms. Holden was employed as a technical

adviser to Owens’ management, responsible for making

sure its AAPs complied particularly as to format and con

tent with the requirements of Revised Order No. 4. Com

pare Smith v. Singer Co., 650 F.2d 214, 217 (9th Cir. 1981),

with authorities relied upon by petitioner, none of which in

volved an EEO specialist.10 See Argument, infra, 19, 23-24.

10 Payne v. McLemore's Wholesale & Retail Stores, supra

(laid off employee picketing, among others, his employer for

failure to hire blacks in supervisory and white collar jobs);

Berg v. La Crosse Cooler Co., 612 F.2d 1041 (7th Cir. 1980)

(personnel department clerk who differed politely with

Personnel Director over Company's maternity benefit poli

cy); Rucker v. Higher Educational Aids Board, 669 F.2d 1179 (7th

Cir. 1982) (black supervisor who refused to "set up" white fe

male for discharge and informed his black superior that he

agreed with woman's sexual harassment and other discrimina

tion claims); Sisco v. I.S. Alberici Construction Co., 655 F.2d 146

(8th Cir. 1981) (white construction worker and union shop

steward who claimed "reverse discrimination" in his layoff se-

(Continued on following page)

17

Second, Ms. Holden’s “ opposition” was to tlie Com

pany’s “ commitment” to affirmative action. As this Court

clearly held in United Steelworkers of America v. Weber,

443 U.S. 193, 204-08 (1979), development of voluntary af

firmative action programs is permitted, but not required,

by Title VII when Section 703(j) of that Act is taken into

consideration. Furthermore, Revised Order No. 4 itself

speaks not of illegality, but of “ good faith effort” to im

prove the utilization of minorities and women, through the

use of realistic and voluntary goals and timetables. 41

C.F.R. 60-2.11 and 60-2.12. Finally, Revised Order No. 4

admonishes all Federal contractors that:

“ The purpose of a contractor’s establishment and use

of goals is to insure that it meets its affirmative action

obligation. It is not intended and should not be used to

discriminate against any applicant or employee because

of race, color, religion, sex, or national origin.”

41 C.F.R. § 60-2.30. “Opposition” to how a company seeks

to develop its AAPs or achieve its affirmative action goals

is simply not protected subject matter because non-compli

ance with Revised Order No. 4, which is enforced through

(Continued from previous page)

lection under AAP); S/'as v. City Demonstration Agency, 588 F.2d

692 (9th Cir. 1978) (member of city agency seeking Mexican-

American applicants who complained to Federal compli

ance agency about discriminatory hiring practices); Gifford

v. Atchison, Topeka & Santa Fe Railroad Co., 685 F.2d 1149 (9th

Cir. 1982) ("relief" clerk who claimed discriminatory effect re

sulted from labor agreement expansion of geographic work

area); Love v. Re/Max of America, Inc., supra (female executive

who complained about pay discrimination against her); and

Parker v. Baltimore and Ohio Railroad Co., 652 F.2d 1012

(D.C. Cir. 1981) (white male employee complaining about re

verse discrimination precluding his employment opportunities

in favor of black beneficiaries of an AAP).

18

an entirely different legal framework, see 41 C.F.R, §§ 60-

1.26, 60-1.28, and 41 C.F.R. Part 60-30, is not synonomous

with discrimination “ made unlawful by this subchapter

[Title V II].” 42 U.S.C. § 2Q00e-3(a).

Third, Section 704(a) protects expression of opinion,

not conduct. The manner in which Ms. Holden conducted

herself was the ultimate, uncontradicted cause of her dis

charge. Her refusal to accept directions and adversarial

approach to everything connected with her brief Owens’

employment compares to that found unprotected in Hoch-

stadt v. Worchester Foundation for Experimental Biology,

545 F.2d 222, 231 (1st Cir. 1976); see also Monteiro v. Poole

Silver Co., 615 F.2d 4, 7-8 (1st Cir. 1980) (opposition raised

as a “ smokescreen” for disregard of supervisory instruc

tion is not activity protected by Section 704(a)).

Ms. Holden’s evidence and the district court’s findings

were missing two essential elements of a prima facie Sec

tion 704(a) “ opposition clause” case: opposition to pro

tected subject matter and any causal connection between

such protected opposition and her discharge. In addition,

the court of appeals accepted the district court’s findings

of fact as to petitioner’s “ rigid and unyielding demands”

and the district court’s implicit acknowledgement that she

had “engaged in numerous instances of unsatisfactory be

havior,” quoting from its findings on the post-Shreveport

visit activities (Pet. App. 16a-17a). Where the facts justi

fied Owens ’ termination of Ms. Holden if the subject mat

ter of her opposition was unprotected, then she could not

as a matter of law prove that such legitimate reasons for

discharging her were a pretext for unlawful retaliation

(Id.). Texas Department of Community Affairs v. Burdine,

450 U.S. 248 (1981) and United States Postal Service

19

Board of Governors v. Aikens, 460 U.S. 711 (1983). The

conclusion reached by the court of appeals was correct,

therefore, where its differences of opinion with the district

court were as a matter of law, not fact.

B. The Court of Appeals’ Interpretation of the

Scope of Section 704(a) In This Case Was

Appropriate and Consistent With the Only

Decisions Involving Similar Subject Matter

The court of appeals, in deciding the instant case,

analogized it properly to the only appellate court decisions

involving similar subject matter. Smith v. Singer Go.,

supra; Whatley v. Metropolitan Atlanta Rapid Transit

Authority, 632 F.2d 1325 (5th Cir. 1980); see also Jones v.

Flagship International, 793 F.2d 714 (5th Cir. 1986). These

cases hold that Section 704(a) grants equal opportunity of

ficers or affirmative action specialists no special brand of

protection. In fact, the Sixth Circuit noted that individuals

in such jobs are distinguishable from other employees:

“ The position was unique in that it required the oc

cupant to act on behalf of his employer in an area

where normally action against the employer and on be

half of the employees is protected activity.”

Pet. App. at 14a, quoting Singer, supra, at 217.

Owens, like Flagship International, was entitled to re

quire a “ commitment” from Ms. Holden to its affirmative

action program interests, not her own. As the Fifth Circuit

held in Flagship:

20

“ [I] t was her position, as a representative of the com

pany in EEO matters, not her methods, which created

the conflict of interest.”

* * # .

“ [S]ome conduct, even if sincere opposition to em

ployment practices under Title VII, may be so disrup

tive or inappropriate as to fall outside the protection

of § 704(a).”

793 F.2d at 725 n. 12 and 728. Cf. Rosser v. Laborers’ In

ternational Union, 616 F.2d 221, 223 (5th Cir.) cert, denied

449 U.S. 886 (1980) (employee’s “conduct . . . so interferes

with the performance of his job that it renders him ineffec

tive in the job for which he was employed” ).

Ms. Jones’ opposition in Flagship was to Title VII

subject matter; yet, because of her position with the com

pany, it was unprotected by Section 704(a). In Ms. Hol

den’s case her opposition was not even to Title VII subject

matter, all the more reason why, in light of her AAP man

ager position, it should be held “ unprotected” by Section

704(a). The Sixth Circuit, therefore, in reliance on Singer

and Whatley, and based on the district court’s own find

ings, properly concluded that petitioner’s deviation from

her unique fiduciary duty in favor of assuming a self-pro-

claimed compliance officer role “ disabled” her from per

forming the job for which she had been employed. Such

interpretation of Section 704(a), given the unique facts of

this case, was consistent with applicable precedent and al

together appropriate.

21

II.

THIS CASE DOES NOT PRESENT IMPORTANT

QUESTIONS CONCERNING THE SCOPE

OF SECTION 704(a)

A. No Issue of National Importance Exists

Which Necessitates Expansion of the Scope

of Section 704(a) Because Relief is Already

Provided for Under the Executive Order

Program

While petitioner would like this Court to review her

case, it involves no issue of national importance because of

its unique facts. The authorities relied upon by Ms. Holden

in Part II-A of her petition (Pet. at 31-36) do not justify

issuance by this Court of a writ.11

When Congress enacted Title VII, it provided an anti-

retaliation provision in Section 704(a) similar to provisions

Petitioner cites (Pet. 29-30) four cases for the proposition

that Section 704(a) should encompass opposition such as Ms.

Holden's. Smith v. Singer Co., supra; Wrighten v. Metropolitan

Hospitals, Inc., 726 F.2d 1346 (9th Cir. 1984); Hicks v. ABT

Assoc., Inc., 572 F.2d 960 (3d Cir. 1978); and Sias v. City Dem

onstration Agency, supra. None are apposite. Wrighten, Hicks,

and Sias all involve employees, other than EEO specialists, com

plaints concerning specific employer practices claimed to vio

late Title VII. In Wrighten, hospital employment practices, i.e.,

staffing, were the Title VII subject matter to which complainant

attributed the inadequate black patient care. Singer is discussed,

supra. Petitioner's reliance (Pet. 30 and n. 23) on appellate

court recognition of Section 704(a) protection of opposition in

the parallel 42 U.S.C. § 1981 context is simply inapplicable.

Non-compliance with voluntary affirmative action obligations is

not synonomous with or analogous to discrimination prohibited

by Title VII.

22

included in other employment laws.12 This Court, however,

has cautioned against attempts to use activity “ protected”

in one statutory context to accomplish objectives “ unpro

tected” in another. Emporium Capwell Co. v. Western Ad

dition Community Organization, 420 U.S. 50, 70-73 (1975).

Section 704(a) of Title VII should not be expanded to pro

tect opposition to a company’s commitment to affirmative

action.

It is, furthermore, unnecessary for this Court to ex

pand judicially the scope of Section 704(a) beyond “opposi

tion” to practices which are made violative of Title VII be

cause the Executive Order Program provides its own anti

retaliation protection. Specifically, 41 C.F.R. § 60-1.32 al

ready provides that the OFCCP Director in appropriate

circumstances can institute enforcement proceedings

against any employer:

“ . . . [W]ho fails to take all necessary steps to en

sure that no person intimidates, threatens, coerces, or

discriminates against any individual for the purpose

of interfering with . . . any other activity related to the

administration of the order . . . ”

See also 41 C.F.E. § 60-1.24 (Executive Order Program

Complaint Procedure).

The Weber distinction between discrimination prohibi

tion and affirmative action compliance should, therefore, be

preserved; and, absent amendment by Congress, the scope

of Section 704(a) should not be judicially broadened to in-

£.g., Section 8(a)(4) of the National Labor Relations Act,

29 U.S.C. § 158(a)(4); Section 15(a)(3) of the Fair Labor Standards

Act, 29 U.S.C. § 215(a)(3) and Section 11 of the Occupational

Safety and Health Act, 29 U.S.C. § 660. Petitioner has so recog

nized (Pet. at 32 n. 24). Each of these statutes' anti-retaliation

provisions protect opposition with respect to that statute's sub

ject matter.

elude “ opposition” to a company’s affirmative action prac

tices,

B, Expansion of Section 704(a) To Provide

“ Absolute Immunity” For Affirmative

Action Program Fiduciaries Will Itself Ad

versely Effect, Not Enhance, Achievement of

Executive Order No. 11246 Objectives

Pressure is already exerted by government compliance

officers upon the nation’s employers to satisfy the require

ments of Executive Order No. 11246 and Revised Order No.

4. See 41 C.F.R. §§ 60-1.26 to 60-1.33; see also 41 C.F.R.

Part 60-30.

Satisfaction of the requirements of Revised Order No.

4, particularly the annual revision of “ utilization an

alyses,” 41 C.F.R. §60-2.11, and the preparation on the

basis thereof of “ goals and timetables”, 41 C.F.R. § 60-2.12,

is technical and complex. It is, therefore, necessary for em

ployers to hire affirmative action specialists whose inter

ests are consistent with those of the company. These in

dividuals, as distinct from other employees, simply cannot

be licensed to act as adversaries of management.

The Ninth Circuit said it well when, declining to apply

Section 704(a) to protect an affirmative action specialist,

it noted:

“ The question is whether, under § 2000e-3(a), it is pro

tected activity for this executive employee, occupying

this position of responsibility, to take such action

against the company he represents in support not of his

own rights but of the perceived rights of those with

whom it is his duty to deal on behalf of the company.

I f § 2000e-3(a) gives him the right to make himself an

adversary of the company, then so long as he does not

give nonprivileged cause for dismissal he is forever

24

immune from discharge. Section 2000e-3(a) so con

strued renders wholly unworkable the program of vol

untary compliance which appellant was employed to

conduct. It was the same public interest in equal em

ployment opportunities that brought forth both Title

VII and the executive orders and regulations in ques

tion. Surely there must be room for them to operate

harmoniously. ’ ’

Smith v. Singer Co., supra, at 217 (emphasis added).

Just as Mr. Smith betrayed his employer surrepti

tiously, Ms. Holden “ disabled” herself with Owens’ man

agement by seeking to enforce her own affirmative action

demands instead of acting “ on behalf of” the Shreve

port plant consistent with her supervisor’s instructions

to develop and audit AAPs which would ensure that

the company satisfied Revised Order No. 4. Ms. Holden

simply created a ‘ ‘ conflict of interest ’ ’ between herself and

Owens to the extent that she became ineffective in the job

for which she had been employed. Jones v. Flagship Inter

national and Rosser v. Laborers’ International Union,

supra.

What petitioner seeks in this writ is transformation by

this Court of Section 704(a) from a shield against retalia

tion for opposition to conduct violative of Title VII into a

sword for use within a Company to achieve personal af

firmative action goals inconsistent with company-estab

lished procedures and beyond those specified by the Fed

eral regulations. OFCCP does not need a private attorney

general within each company to accomplish the Executive

Order’s objectives and Section 704(a) should not be misap

plied in a way which will surely disrupt the ability of em

ployers to pursue voluntary affirmative action compliance

and goals in the manner they, not their EEO specialists,

deem most appropriate.

25

III.

THE COURT OF APPEALS’ DECISION

IS CONSISTENT WITH THIS COURT’S

DECISION IN PULLMAN-STANDARD V. SWINT

In. Pullman-Standard v. Swint, 456 U.S. 273, 287-93

(1982), this Court criticized an appellate court ’s practice of

holding itself bound under Rule 52(a) by “subsidiary

facts” found by the trial court, but not by findings as to

“ ultimate facts.” This Court went on to hold:

“ Rule 52(a) broadly requires that findings of fact not

be set aside unless clearly erroneous. . . . This Rule

does not apply to conclusions of law. The Court of Ap

peals, therefore, was quite right in saying that if a dis

trict court’s findings rest on an erroneous view of the

law, they may be set aside on that basis. ’ ’

Id. at 287. Moreover, the Court held :

‘ ‘ [W] here findings are infirm because of an erroneous

view of the law, a remand is the proper course unless

the record permits only one resolution of the factual

issue. ’ ’

Id. at 292 (emphasis added).

In the instant case the court of appeals did not make

de novo findings of fact. It accepted the district court’s

specific findings regarding the subject matter and manner

of Ms. Holden’s opposition activities. However, it noted

that the district court did not make any specific findings

of fact as required by Rule 52(a) with respect to any spe

cific practices of Owens which petitioner opposed that

she perceived to be “ made unlawful by Title V II” (Pet.

App. at 6a). The court of appeals then examined the

transcript, the record, and the district court’s opinion

in search of any facts suggesting petitioner’s “ opposi-

26

tion” was addressed to Title VII, rather than affirmative

action, subject matter; and it found none.

Based upon the findings which the district court made

and the absence of any record evidence of opposition to

Title VII subject matter, the court of appeals properly con

cluded—“ the record permit [ting] only one resolution of

the factual issue,” 456 U.S. at 292—that the district court

had erred as a matter of law by granting petitioner relief

with respect to opposition addressing subject matter “ un

protected” by Section 704(a).

■--------------- o----------------

CONCLUSION

For the foregoing reasons, a writ of certiorari should

not issue to review the judgment and opinion of the Sixth

Circuit.

Respectfully submitted,

#L loyd S u t t e r

D avid F. G u l d e n s c h u h

K in g & S palding

2500 Trust Company Tower

Atlanta, Georgia 30303

(404) 572-4600

R. J e ffr e y B ixler

O w e n s - I l l in o is , I n c .

One Sea Gate

Toledo, Ohio 43666

Attorneys for Respondent

Owens-Illinois, Inc.

*Counsel of RecordNovember 14, 1986

App. 1

APPENDIX

Owens-Illinois, Inc., pursuant to Rule 28.1 of this

Court, identifies the following as its subsidiaries, other than

wholly-owned subsidiaries, and affiliates:

Advanced Graphics, Inc.

Milford, NH

Andover Controls Corporation

Andover, MA

HCRC Services, Inc.

Toledo, OH

HCRC Services of Illinois, Inc.

Toledo, OH

HCRC Services of South Carolina, Inc,

Toledo, OH

HCRC Services of Texas, Inc.

Toledo, OH

Prudent Supply, Inc.

Minneapolis, MN

Toledo Air Associates, Inc.

Toledo, OH

O-I/Schott Process Systems, Inc.

Vineland, NJ

Owens-Illinois de Puerto Rico

Puerto Rico

Societe Anonyme de Developpement du Verre de Table

Mecanique

Belgium

Libbey St. Clair Inc.

Canada

Cristal Owens Plasticos Ltd.

Chile

Cristaleria Peldar, S.A.

Colombia

App. 2

Cristaleria del Ecuador, S.A.

Ecuador

Middle East Glass Mfg. Co.

Egypt

Emballages Laurent, S.A.

France

Papeteries d ’Espaly, S.A.

France

Papeteries Etienne, S.A.

France

Hellenic-Owens Elefsis Glass Company, S.A.

Greece

P. T. Igar Jaya

Indonesia

P. T. Kangar Consolidated Industries

Indonesia

Nippon Electric Glass Company, Limited

Japan

Nippon Glass Kabushiki Kaisha

Japan

Sasaki-Owens Glass Co., Ltd.

Japan

Sun-Lily Co. Ltd.

Japan

Hankuk Electric Glass Co., Ltd.

Korea

Cajas Corrugadas de Mexico, S.A.

Mexico

Cajas y Empaques de Occidente, S.A.

Mexico

Envases de Borosilicato, S.A.

Mexico

App. 3

Inmuebles Heda, S.A.

Mexico

Kraft, S.A.

Mexico

Union Cdass & Container Corporation

Plxillippines

Consol Limited

South Africa

U.S.I. Far East Corporation

Taiwan

Manufactuera de Vidrios Pianos, C.A.

Venezuela