McCrary v Runyon Brief Amicus Curiae

Public Court Documents

January 25, 1974

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. McCrary v Runyon Brief Amicus Curiae, 1974. 79c35f7e-bc9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c36f62c0-d665-4add-850e-51eb16a1fe54/mccrary-v-runyon-brief-amicus-curiae. Accessed February 20, 2026.

Copied!

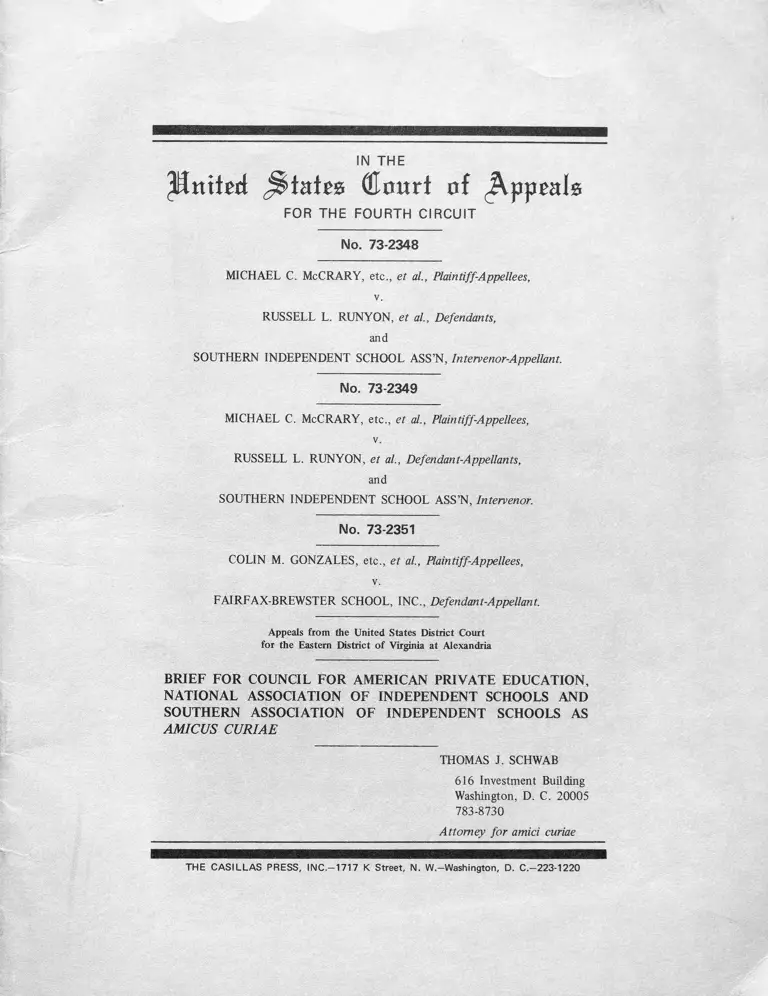

IN THE

P m hd m (ttmtrt of JVppeals

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

No. 73-2348

MICHAEL C. McCRARY, etc., et al., Plaintiff-Appellees,

v.

RUSSELL L. RUNYON, et al., Defendants,

and

SOUTHERN INDEPENDENT SCHOOL ASS’N, Intervenor-Appellant.

No. 73-2349

MICHAEL C. McCRARY, etc., et al., Plaintiff-Appellees,

v.

RUSSELL L. RUNYON, et al., Defendant-Appellants,

and

SOUTHERN INDEPENDENT SCHOOL ASS’N, Intervenor.

No. 73-2351

COLIN M. GONZALES, etc., et al., Plaintiff-Appellees,

v.

FAIRFAX-BREWSTER SCHOOL, INC., Defendant-Appellant.

Appeals from the United States District Court

for the Eastern District of Virginia at Alexandria

BRIEF FO R COUNCIL FO R AMERICAN PRIVATE EDUCATION,

NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF INDEPENDENT SCHOOLS A N D

SOUTHERN ASSOCIATION OF INDEPENDENT SCHOOLS AS

AMICUS CURIAE

THOMAS J. SCHWAB

616 Investment Building

Washington, D. C. 20005

783-8730

Attorney fo r amici curiae

THE CASILLAS PRESS, INC.-1717 K Street, N. W.-Washington, D. C.-223-1220

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

THE INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE. ....................................±

INTRODUCTION......................................................3

ARGUMENT................................... ..................... 6

Application of 42 U.S.C., Sec. 1981 so as to

Prohibit Rejection by Appellant Schools of

Appellees because Appellees were Black Does

Not Violate any Constitutional Rights of

Appellant Schools or of Parents of Children

who Attend them or of Private Schools Generally

CONCLUSION. . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . . ................. 20

TABLE OF GASES

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U.S. 497 (1954)........................... 16

Bond v. Floyd, 385 U.S. 116 (1966)............................... 10

Brown v. Gaston County Dyeing Machine Company, 457 F. 2d 1377

(4th Cir. 1972) . . 5

District of Columbia v. Thompson Co., 346 U.S. 100 (1953) • • • • 19

Elfbrandt v. Russell, 3&4 U.S. 11 (1966).......... 10

Farrington v. Tokushige, 11 F. 2d 719 (9th Cir. 1926),

aff'd 273 U.S. 284 (1927).............. 7

Green v. Connally, 330 F. Supp. 1150 (D.B.C. 1971) f

aff'd sub. nom. Coit v. Green, 404 U.S. 997 18, 19

(1971) •

Grier v. Specialized Skills, Inc., 326 F. Supp. 856

(W.D.N.C. 1971) .............. 5

Griffin v. Breckenridge, 403 U.S. 88 (1971)..................... 19

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971)................... 20

Griswold v. Connecticut, 381 U.S. 479 (1965)........ * .......... 11

Heart of Atlanta Motel v. United States, 379 U.S. 241 (1964). . . 19

Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co., 392 U.S. 409 (1968) .............. 5 , 19

Meyer v. Nebraska, 262 U.S. 390 (1923)• . . . . . . . . . . . . . . 7

Meyerkorth v. State, 173 Neb. 889, 115 N.W. 2d 585 (1962) ........ 7

Murray v. Jamison, 333 F. Supp. 1379 (W.D.N.C. 1971). . . . . . . . 10

N.A.A.C.P. v. Alabama, 357 U.S. 449 (1958)......................... 10, 11

N.A.A.C.P. v. Alabama, 377 U.S. 288 (1964). .........................n

Norwood v. Harrison, 413 U.S. 455 (1973)........................... 6, 17, 18, 19

Pierce v. Society of Sisters, 268 U.S. 510 (1925)............ • • 6, 14

Schneider v. Irvington, 308 U.S. 147....................... . . . . 10

Schneider v. Smith, 390 U.S. 17 (1968). . . . . . . . . . ........ 10

Schneidenaan v. United States, 320 U.S. 118 (1943). . . . . . . . . 10

Scott v. Young, 421 F. 2d 143 (4th Cir. 1970) . . . . . . . . . . . 5

Sims v. Order of United Commercial Travelers of America,

343 F. Supp. 112 (D. Mass. 1972). . . . . . 5

State v. Superior Court, 55 W. 2d 177, 3^6 P. 2d 999 (1959) . . . . 7

State v. Williams, 253 N.C. 337, 117 S.E. 2d 444 (i960) .......... 7

Tillman v. Wheaton Haven Recreational Association, Inc.,

410 U.S. 431 (1973)...............5, 7 , 19

United States v. Hunter, 459 F. 2d 205 (4th Cir. 1972),

cert. den. 409 U.S. 931* (1972).......... 20

United States v. Korner, 56 F. Supp. 242 (S.D. Cal. 1944)........ 10

United States v. Medical Society of South Carolina,

298 F. Supp. 145 (D.S.C. 1969) .......... 5

United States v. Robel, 389 U.S. 258 (1967) ....................... 10

West Coast Hotel v. Parrish, 3°0 U.S. 379 (1937). . . . . . . . . . 16

Wisconsin v. Yoder, 406 U.S. 205 (1972) ........................... 6

Wold v. Shoreline School District, 363 U.S. 8l4 . . . . . . . . . . 7

Zucht v. King, 260 U.S. 174 (1922)................................. 7

TABLE OF STATUTES

Page

28 U.S.C., Section 1981. . . . . ............................... 3

k2 U.S.C., Section 2000a . ....................... 19

k2 U.S.C., Section 2000e . ................. 19

k2 U.S.C., Section 36OI. . . . ....................... . . . . . 19

IN THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

No. 73-231*8

MICHAEL C. McCRAHY, etc., et al.,

Plaintiff-Appellees,

v.

RUSSELL L. RUNYON, et al.,

Defendants,

and

SOUTHERN INDEPENDENT SCHOOL ASS'N,

Intervenor- Appellant.

No. 73-23^9

MICHAEL C. McCRARY, etc., et al.,

Plaintiff“Appellees,

v .

RUSSELL L. RUNYON, et al.,

Defendant-Appellants,

and

SOUTHERN INDEPENDENT SCHOOL ASS'N

Intervenor.

No. 73“2351

COLIN M. GONZALES, etc., et al.,

Plaintiff-Appellees,

v.

FAIRFAX-BREWSTER SCHOOL, INC.,

Defendant-Appellant.

Appeals from the United States District Court

for the Eastern District of Virginia at Alexandria

BRIEF FOR COUNCIL FOR AMERICAN PRIVATE EDUCATION,

NATIONAL ASSOCIATION OF INDEPENDENT SCHOOLS AND

SOUTHER! ASSOCIATION OF INDEPENDENT SCHOOLS AS

AMICI CURIAE

THE INTEREST OF AMICI CURIAE

This brief is submitted by three organizations, each of which is,

directly or indirectly, an association of private schools. The Council for

American Private Education is an association of ten groups, each of which is

itself an association of private schools. The Council’s member groups are tin

following:

American Lutheran Church, Division of Parish Education

Friends Council on Education

Lutheran Church - Missouri Synod, Board of Parish Education

National Association of Christian Schools

National Association of Episcopal Schools

National Association of Independent Schools

National Catholic Educational Association

National Society for Hebrew Day Schools

National Union of Christian Schools

U. S. Catholic Conference.

The National Association of Independent Schools, the second of amic:

curiae, has been in existence in its present form since 1962, when it result©

from a merger of two independent schools associations dating back to 1924 and

1942 respectively. Its membership consists of 734 elementary and secondary

schools of various kinds throughout the U. S.; there are 53 Affiliate member

independent schools outside the U. S.; and there are 52 Association members,

made up of 28 state and regional associations of independent schools; four d

nominational associations; 9 special purpose associations; and seven admini;

trators’ and teachers’ associations. Almost all of the state and regional as'

sociations of schools are made up of schools which themselves are NAlS member

The third amici curiae is the Southern Association of Independent

Schools (not to be confused with the Southern Independent School Association,

2.

Intervenor below), the membership of which includes one hundred thirty-eight

private schools.

Allowing for some overlapping in membership among the three associa

tions, amici curiae as a group include within their membership some twelve to

fifteen thousand private schools, accounting for well over ninety percent of

the non-public school enrollment in the United States.

This litigation presented for decision by the Court below the issue

of whether racial discrimination against black persons by defendant private

schools constituted a violation of the Civil Rights Act of 1866, k2 U.S.C.,

Sec. 1981. As appears from the decision of the Court below, Southern Inde

pendent School Association intervened as a party defendant, asserting that it

represented "non profit, private white schools in seven states and the class

of all similarly situated schools and their associated students and parents".

The Court below held that racial discrimination against black persons by de

fendant private schools was a violation of k2 U.S.C., Sec. 1981.

Intervenor, Southern Independent School Association, argued below

and has argued in its brief in this Court that k2 U.S.C., Sec. 1981, properly

construed, does not prohibit discrimination by private schools, and that the

contrary construction would constitute a violation of rights of private

schools, their students and parents, under the United States Constitution.

Implicit in Intervenor*s position, particularly in light of the assertions in

its Motion to Intervene, is that Intervenor speaks for and expresses the

views of a significant segment of private schools.

Amici curiae do not purport to speak for all of the private schools

which are affiliated with them. They do, however, express the views of their

associations, and of a very sizeable number of private schools which, in af

3

filiating with, one or sore of amici curiae, have placed themselves on record

as being unalterably opposed to the practice of racial discrimination against

black persons in private education. Ihey submit this brief in order that

their views be known to this Court and in order that this Court understand

that the associations representing the overwhelming percentage of private

schools in this country believe that the decision of the Court below was cor*

rect and that it should be affirmed by this Court, that the application of

42 U.S.C., Sec. 1981 to private schools as determined by the Court below does

not constitute an unwanted or unreasonable interference with what they con

sider to be the legitimate operations of private schools, and, further, that

they welcome the decision of the Court below as an added means by which the

stain of racial discrimination in American education ceua be the sooner re

moved, and the opportunity of a private education be available to those blacl

persons as well as those white persons who seek it and can qualify for it.

INTRODUCTION

The purpose of this brief is to bring before the Court the point ol

view of amici curiae only on those issues in the case which are particularly

within their purview and concerning which their first hand knowledge and ex

perience may be helpful to the Court. Amici curiae will therefore address

themselves in this brief only to the issue of whether 42 U.S.C., Sec. 198l#

A/ "All persons within the jurisdiction of the United States shall have the

same right in every State and Territory to make and enforce contracts . . .

as is enjoyed by white citizens . . (42 U.S.C., Sec. 1981)

4.

as applied by the Court below, constitutes a violation of any constitutional

S J

rights of private schools or of the parents of children who attend them.

As to the other principal legal issue in the case, which is whether Section

1981 was properly construed by the Court below as prohibiting discrimination

against black persons in admission to appellant private schools, amici curiae

will limit themselves to submitting that the decision of the Court below was

£/ The designation "private schools" as used throughout this brief refers to

schools which, though they render a public service recognised by governments,

are private in the sense that they are not operated by governments. In that

sense, appellant schools, those affiliated with Intervener and those affilia

ted with amici curiae are all "private schools". In using the ter® in this

way, however, it must be kept in mind that appellant schools are not "private"

as that term is used in another sense to refer to the essentially personal

relationship involved when a group of persons, usually small in number and

having some common element of interest, gather together for a social or simi

lar common purpose. The record before the Court below makes clear that both

appellant schools solicited applicants for membership through the mails and

through telephone directory advertising. Though not part of the record,

there can be little doubt that the majority of schools affiliated with Inter-

venor and with amici curiae are not private in this latter sense.

5.

not only correct but was required in view of the prior decisions of the United

States Supreme Court and of this and other Courts of Appeal, which make clear

that Section 1981 bars discrimination against black persons in contractural

relationships, or in the words of the Supreme Court describing the Act of Con

gress in which Section 1981 first appeared, that it "meant exactly what it

said". Jones v, 392 U.S. 409, 422 (1968); m t e S J h

Wheaton Haven Recreational^s^ociatlQiLLJ^g^.^ 410 U.S. 4 31 (1973); y,fc

3/

Young. 421 F. 2d 143 (4th Cir. 1970); «... IBS 1 >

326 F. Supp. 856 (W.D.N.C. 1971); Brown v. Gaston County Pyeiflg MacMne_SQEE

Twnvj 457 F. 2d 1377 (4th Cir. 1972); United Sta&UL.£> H^ctjcal gQQls&y. ,.o£

South Carolina. 298 F. Supp. 145 (D.S.C. 1969); QS fiHC

mercial Travelers of __ America > 343 F. Supp. 112 (D. Mass. 1972).

3/ This Court determined the applicability of Section 1981 in the Sgfijdi case

upon the basis that the right of admission to the facility there involved was

bestowed in return for a fee. Precisely the same can be said with respect to

the case at bar. The conclusion in Scott, that the opportunity to enter into

this contract of admission could not be denied on the ground that plaintiff

was black, applies equally to the facts of the case at bar and thus requires

the same result.

6.

ARGUMENT

APPLICATION OF k2 U.S.C., SEC. 19&L SO AS TO PROHIBIT REJECTION BY APPELLANT

SCHOOLS OF APPELLEES BECAUSE APPELLEES WERE BLACK DOES NOT VIOLATE ANY CON

STITUTIONAL RIGHTS OF APPELLANT SCHOOLS OR OF PARENTS OF CHILDREN WHO ATTEND

THEM OR OF PRIVATE SCHOOLS GENERALLY.

The constitutional right of private schools to exist, and of par

ents to send their children to attend them rather than attending public

schools, was clearly decided by the United States Supreme Court almost fifty

years ago, in , 268 U.S. 510 (1925), and reaf

firmed frequently since then and as recently as two years ago in Wisconsin

v. Yoder. 4o6 U.S. 205 (1972). As associations of private schools, amici

curiae look upon Pierce and its progeny as establishing a sort of "bill of

rights" for private schools and rightfully recognizing the unique and impor

tant role of private schools in our system and the contribution which they

make to American education. Accordingly, amici curiae would be the last to

question the validity or the vitality of these cases. But, as pointed out

by the Chief Justice in Norwood v. Harrison. ^13 U.S. ^55 (1973)> the case

upon which Intervenor relies so heavily in its brief in this Court, "the

Court's holding in Pierce is not without limits", and, quoting from Mr.

Justice White in Yoder. Pierce "held simply that while a State may posit

(educational) standards, it may not pre-empt the educational process by

requiring children to attend public schools", *̂13 U.S. at 46l. In short,

while Pierce and Yoder establish very clearly the right of private schools

to exist, they do not establish the right of private schools to be free

from reasonable legislative regulation.

7.

Private schools have been held subject to regulations concerning

their educational adequacy, failing which attendance at the private school is

held not a defense to an action under a state compulsory attendance law.

See, for example, St&t.gLy, 55 W. 2d 177, 3^6 P. 2d 999 (1959),

cert. den. sub. nom. Wpld,. y t. ShQrslips Sfltegl...Pls1<riQ.t, 363 U.S. 8l4; Meyeg-

korth v. State. 173 Neb. 889, 115 N.W. 2d 585 (19 6 2). And private schools,

like many other private institutions, are subject to reasonable regulation by

state or federal government in furtherance of legitimate legislative purposes

and provided that constitutional rights are not violated. Meyer v. Nebraska.

262 U.S. 390 (1923); Farrlnaton y, Tokushige. 11 F 2d 710 (9th Gir. 1926),

aff’d 273 U.S. 20k (1927); Z a s h UjJOag, 260 U.S. Yfk (1922); Sj&le.v.

Williaias. 253 N.C. 337, 117 S.E. 2d kkk (i960).

There being no doubt that Section 1981 was validly enacted by Con

gress under authority of the Thirteenth Amendment, Tillman y. Wheaton Haven

Recreational Association. Inc.. ^10 U.S. ^31 (1973), there is no question in

this case as to the legitimate legislative purpose of this statute. Accord

ingly, the only question remaining is whether the statute as applied by the

Court below violates a recognized constitutional right.

In order for this Court to consider this issue, it must first con

sider the way in which Section 1981 affects appellant schools, which is, of

course, the same way in which it affects all of the schools affiliated with

amici curiae. And in view of some of the extravagant assertions of appel

lants concerning the impact of the law, it will be helpful to approach this

problem in terms of what Section 1981 does not do, as well as in terms of

what it does. Since the effect upon appellants is also the effect upon our

8

affiliates, amici curiae have a particular Interest in a clear understanding

of the limitations of this law.

In the first place, it is clear that Hie statute in no way prohibits

the right to teach unpopular theories concerning race, concerning the value or

harm of racial segregation, or concerning anything else. Any indication to

the contrary is wholly false. Amici curiae, numbering among their affiliated

schools representatives of groups which have historically been considered

minorities in one country or another and in one time or smother, are as sensi

tive as anyone, and perhaps more than most, to the importance of free thinking

and free teaching, particularly where the education of young people is involved.

Amici curiae would resist any effort on the part of government to control

thought processes and teaching in their schools and elsewhere, and would be

among the first to challenge any law which had such an effect, whether the

limitation was directed to a belief which they found compatible, or, as would

be the case with the beliefs espoused by Intervenor in its brief in this Court,

one with which they are in sharp disagreement. But amici curiae support the

decision of the Court below without reservation because it is clear from the

wording of Section 1981 and from the holding of the Court below that the free

dom to teach or speak about ideas or theories, any ideas or theories, is in no

way limited by this statute as applied by Hie Court below.

Secondly, the statute as applied by the Court below in this case

places no limitation on the simple right to associate in private for educa

tional or other purposes. The only issue at stake in these cases is the ap

plicability of Section 1981 to schools which are concededly open to all quali

fied whites but are closed to all blacks, no matter how highly qualified.

9

W M l e some Court may have to decide some day the constitutional bounds of Sec

k /

tion 19 8 1 if it is ever applied to strictly private activity, that issue is

not before the Court in this case.

Thirdly, while Section 19 8 1 places a limitation on one criterion

for admission to a private school, namely the criterion of whether the appli

cant is white or black, it places no limitation on any other criteria which a

private school may choose to use, whether of a kind generally used by many

private schools, such as test performance, geographic location, ability to

pay, willingness to abide by rules and regulations, etc., or whether, for

that natter, of a kind not generally used by private schools, or even whether

it would be considered arbitrary or unrelated to the purpose of private

schools generally.

Fourthly, Section 19 8 1 places no limitation on the right of a pri

vate school to concentrate its curriculum in such a way as to appeal to a

particular religious or national group, or any other group, nor the right to

seek applications from a particular segment of the population which might be

expected to wish to avail itself of that kind of particularized education.

If schools which belong to the Intervenor Association, for example, wished

to concentrate their curriculum on studies in white supremacy or wished to

appeal for applicants among those groups which might have an interest in

such an education, Section 19SI would not restrict such activity so long as

the contract of admission was not denied to a black person who might, not

withstanding this concentration of studies, wish to attend.

k j See Footnote 2 supra.

10.

In short, the single effect of Section 1981 upon appellant schools

or upon any private school is to prohibit a refusal to admit a student because

he or she is black. With -amt in mind, we turn to appellants' contention that

this single limitation on their freedom of action is in violation of the Con

stitution.

The process by which a Court evaluates an attack upon a legislative

act on the ground that it violates an asserted constitutional right involves

a consideration of the precise effect of the legislation upon the asserted

right and of the substantiality of the reasons advanced in support of the

legislation. Schneider v ... Igylagfeoa» 308 U.S. 147, l6l; see .Y.i

Alabama. 357 u.s. 449, ^63 (1958) wad 389 u.s. 258,

264 (1967).

As indicated above, Section 1981 places no limitations whatever

upon the rights of appellants, or of the parents whose children attend their

schools, to free speech and free expression, which at the outset distinguishes

this case from most of those upon which appellants rely. Application of Sec

tion 1981 so as to prohibit racial discrimination b y & private school does not

involve a state enforced punishment because of one's beliefs or associations,

as was the case in United. atfttgfi-K*̂ BBfeBl» .SMSm* M liZXaXJL^Jm iG m , 333 F.

Supp. 1379 (W.D.N.C. 1971), and Elfbran&fc. v» Russell. 384 U.S. 11 (1966)

(denial of employment), Schneideraan v. Unitfid.-StaAfiS. 320 U.S. Il8 (1943)

and United States v. K h m e r . 56 F. Supp. 242 (S.D. Cal. 19^0 (revocation of

naturalization), Schneider Xx...Smith. 390 U.S. 17 (1968) (denial of a license)

or pond V. Flovd- 385 U.S. Il6 (1966)(denial of right of elected official to

take seat in state legislature to which he was elected).

11.

Nor Is this a case in which the legislative act, by reason of its

broad scope, could be found by a court to have the effect of depriving a pro

tected relationship from the very essence of its being. In Griswold v. Conn

ecticut. 38 1 U.S. *4-79 (1965) the Supreme Court held that Connecticut's law

which forbade the use of contraceptives, "rather than regulating their manu

facture or sale" had a "maximum destructive impact" upon the marriage rela

tionship, 38 1 U.S. at *4-8 5. It is clear from the majority opinion that the

Court was impressed by the personal and private nature of the relationship

affected by the statute, and, as appears from the Court's quotation of lan

guage from N.A.A.C.P. v- Alabama. 377 U.S. 288, 307 (1964), that Connecticut's

governmental purpose had been achieved "by means which sweep unnecessarily

broadly and thereby invade the area of protected freedoms", 381 U.S. at 485.

And in N.A.A.C.P. v. Alabama. 357 U.S. 449 (1958), which is the other case

principally relied upon by appellants, the Court found that the effort of the

state to compel disclosure of membership in the association was "likely to

affect adversely the ability of (the association) and its members to pursue

their collective effort to foster beliefs which they admittedly have a right

to advocate", 357 U.S. at 462-3.

The right to associate for purposes of free speech or political

activity, and the very private association of the marriage relationship, are

clearly distinguishable from the right to associate for the purpose of opera

ting a school which seeks applicants through direct mail and through tele

phone directory advertising. Indeed, there is nothing in the record to indi

cate that appellant schools involve any kind of act of "association" at all,

at least as that term is normally understood, but are rather more properly

12

viewed as institutions established not by the parents of children now attend

ing the schools but by others, and which, as the record discloses, solicit

their membership rather than having been formed by their membership. More

over, even if such a school is considered to be an association entitled to

constitutional protection, there is surely a difference between a limitation

which affects the right to operate the school so formed in but one respect,

prohibiting the exclusion of one class of citizens, and limitations such as

those found by the Supreme Court in Griswold and N.A.A.C.P.. which for all

practical purposes, destroyed the association or the relationship found to

be entitled to constitutional protection.

Amici curiae submit to this Court that the prohibition of the

"right" to discriminate against blacks because of their race cannot be con

sidered a fundamental deprivation of the right to associate as a private

school. Amici curiae, and the schools affiliated with than, have demonstra

ted by their own actions that they do not consider the right to discriminate

against blacks, or, for that matter, the right to discriminate against any

particular group, as essential to any legitimate rights of private schools.

Indeed, they consider that discrimination in schools, both private and pub

lic, has been detrimental, rather than supportive, to the proper goals of

private education in America. Thus, the principle of non-discrimination on

the grounds of race is not only one to which the organizations affiliated

with amici curiae subscribe, but it is a stated principle adopted by all

members of the Council for American Private Education; it is a stated

principle which is a requirement for all members of the Southern Associa

tion of Independent Schools, notwithstanding the location of such schools

13

in the same area of the country as the schools which are affiliated with In

tervener; and it is a stated principle which is a requirement for a n schools

affiliated with the National Association of Independent Schools. Moreover, a

number of affiliates of amici curiae, recognizing the legacy of slavery and of

the discrimination practiced against blacks in this country since slavery, in

the field of education, both public and private, as well as in other areas,

have adopted or supported various programs seeking not only the implementation

of policies of non-discrimination, but affirmative action programs designed tc

create educational opportunities for minority students, particularly black

l l

students. Amici curiae make these representations to the Court not for the

For example, an applicant for admission to the National Association of In

dependent Schools must submit a statement "that the school’s policies provide

for admission of students & employment of personnel without regard to race or

color (if not contained in the school catalogue)"; the NAIS or its affiliates

have supported such outreach programs as A Better Chance, Inc., Broad Jump,

Inc., the Independent Schools Opportunity Project, the Negro Student Fund, the

Supplementary Program of Hartford in Education Reinforcement and Enrichment,

the Minority Teacher Recruitment Program; a policy of admission policies

without regard to race or color was urged upon its affiliates by the Southern

Association of Independent Schools in 19^9, and became a requirement for ad

mission to the Association in 1971; the constitution of the National Asso

ciation of Episcopal Schools, Inc. states, paragraph 2, that a school eligible

for voting membership in the Association shall be one "whose admission policic

do not exclude any candidate on the basis of race or color".

purpose of exhibiting a "holier than thou" attitude, and not in order to flaunt

obedience to what the Court below has held to be the law of the land, but,

rather, to demonstrate that the application of Section 1981 to private schools

is in harmony with, not in opposition to, the views on the subject of discrim

ination of a very large number of private schools and that depriving private

schools of the "right" to discriminate against black persons does not deprive

them of a right which this group considers essential to their operations or to

the principles of their independence which they hold dear*

'The brief submitted by Intervener suggests (page 32) that the exis

tence of private schools identified with particular religions or nationalities

supports its views as to the importance of a right to discriminate against

blacks in admission to its members* schools. Nothing could be further from

the truth. Intervener fails to perceive a critical distinction between the

desire to provide a specialized education, or one with particular meaning and

importance to a particular group, on the ©ne hand, and a desire to exclude

from the benefits of that particularized education those who may seek it but

who do not belong to the group who would normally be most attracted to that

education® Among the schools affiliated with amici curiae are many which are

operated and maintained by a particular religious, or, in some cases national,

group. Their right to maintain such schools, and the right of parents who so

desire to send their children to such schools is established in Pierce v.

Society of Sisters. supra, and is a valued right. But Intervenor's assertion

would have validity if and only if these schools claimed not only the right

to exist and to educate those children whose parents wish them to attend,

but also the absolute right to exclude other children solely because they do

15.

not belong to the group which operates the school. This is a right which

the schools associated with amici curiae do not claim and which they find

repugnant to their concepts of education, whether public or private, in a

free society. As a matter of fact, the enrollments of whose schools affili

ated with amici curiae which are identified with a particular religion or

nationality frequently include persons who are not members of the particular

religious faith or nationality.

Ifor is the foregoing argument nullified by the fact that those

schools affiliated with amici curiae which offer an education directed

towards a particular religious or national group do not fit into the cate

gory represented by the schools affiliated with Intervenor, namely, schools

directed towards a particular group (i.e., white persons) which, by defini

tion, does not include the class of persons whose rights are specifically

16.

y

protected by Section 1981 (i.e., black persons). If, acting under sppropri-

ate Constitutional authority, and finding that past discrimination against a

Minority has had such detrimental effects, and threatens future detrimental

effects, Congress were to determine that legislative protection is needed,

6/ Intervener1s argument on page 33 of Its brief, that race in Section 1901

is an unsupportable classification for equal protection purposes is hardly

worthy of reply, in view of the fact of slavery and the historic discrimina

tion against blacks, and in view of the fact that it is the benefit of the

statute, not its burden or its impact, which falls upon the particular group.

In West Coast Bate! y^J&rzi£h, 300 U.S. 379, ^00 (1937), the Supreme Court

upheld legislation protecting only women, saying "This Court has frequently

held that the legislative authority, acting within its proper field, is not

bound to extend its regulation to all cases which it might properly reach.

The Legislature is free to recognize degrees of harm and it may confine its

restrictions to those classes of cases where the need is deemed to be clear

est". It is strange logic indeed which holds that because Congress cannot

discriminate on the grounds of race (Bolling—Yjl Shaipe, 3^7 U.S. 497 (195*0,

it cannot legislate to prohibit racial discrimination. The cases upholding

Congressional enactments against racial discrimination sake clear the ab

surdity of the suggestion. See cases cited on page 19 below.

17

and were to enact a law, similar to Section 19 8 1, safeguarding the rights of

some other minority, amici curiae would argue just as strenuously in support

of that legislation as they now argue in support of Section 19 8 1. For the

crucial point here is not which minority is protected hut that the right of

a private school to emphasize and concentrate on the thoughts, philosophies

or practices of a particular group does not depend for its vitality upon the

right to refuse the benefits of that education to one not a member of that

group.

Appellants® asserted constitutional right, therefore, comes down

in the final analysis to the right to practice racial discrimination. Amici

curiae submit that the language of the Supreme Court in Norwood v. Harrison.

surra. rather than supporting this claim, demonstrates its invalidity:

"In contrast, although the Constitution does not

proscribe private bias, it places no value on

discrimination as it does on the values inherent

in the Free Exercise Clause. Invidious private

discrimination may be characterized as a form of

exercising freedom of association protected by

the First Amendment, hut it has never been accorded

18

affirmative constitutional protection". 4-13 U.S. at

hQ9* I/

The constitutional importance of anti-discrimination laws was characterized

hy the Court in Green v. Connallv. 330 F. Supp. 1150 (D.D.C. 1971)> aff'd

sub. nom. Colt v. Green, U.S. 997 (1971)# in the following language:

2/ Intervenor suggests in its brief (pp. 12-16) that the issue of the

applicability of Section 1981 to private schools has already been decided

contrary to the holding of the Court below, by reason of Norwood, v. Harrison.

supra, and Green v. Connallv. 330 F. Supp. 1150 (D.D.C. 1971)# aff'd sub.

nom. Colt v. Green. kOk U.S. 997 (1971). Bit in neither of these cases did

the Court have before it a claim based upon Section 1981 by a person claim

ing to be one protected by this statute, nor would a holding in either case

that Section 1981 did or did not prohibit a refusal to admit a black student

decide the issue presented for decision in each case, namely, the constitu

tionality of making a state textbook program available to schools which dis

criminated against blacks, in Norwood, and the allowance of federal tax de

ductions for contributions to discriminating schools in Green. In Green,

the Court, after referring to the interest of a state in preventing racial

discrimination, indicated that "whether such a state interest is sufficiently

compelling to justify outright prohibition of racial discrimination in edu

cation by private or public schools . . . is a matter we are not called upon

to determine in this case". 330 F. Supp. at 1168.

19.

"There is a compelling as well as a reasonable govern

ment interest in the interdiction of racial discrimin

ation which stands on highest constitutional ground,

taking into account the provisions and penumbra of

the Amendments passed in the wake of the Civil War.

That governmental interest is dominant over other con

stitutional interests to the extent that there is com

plete and unavoidable conflict". 330 F. Supp at 116 7.

Even if it were to be assumed, arguendo, that Section 1981 involved

a constitutionally recognizable limitation on appellants8 right to associate,

this Court would nevertheless have to weigh that limitation against the sub

stantiality of the reasons advanced in support of the law. And here again,

the way is suggested by the Chief Justice in Moavo&d:

"And even some private discrimination is subject to

special remedial legislation in certain circumstances

under Sec. 2 of the Thirteenth Amendment. Congress

has made such discrimination unlawful in other signi

ficant contexts". 413 U.S. at 469.

The Chief Justice, in a footnote to the above quotation, cites as examples

Griffin v. Breekenridge. 4-03 U.S. 88 (1971)> Y,t Alfred IfeyM.-Sfit,

supra, and the federal public accommodations law (42 U.S.C., Sec. 2000a et.

seq.), the federal law against discrimination in employment (42 U.S.C., Sec.

2000e et. seq.) and the federal fair housing law (42 U.S.C., Sec. 3601 e_fc*

seq.). When the federal legislative enactments designed to protect the

rights of blacks against private racial discrimination have been contested

in the Courts, frequently in the face of arguments similar to appellants',

that they impinge impermissibly upon the rights of those charged with dis

crimination, they have been uniformly upheld, in the cases cited by the

Chief Justice and in others such as TflJbman v. Wheaton-HayeiLiigcr,dati

Association. I n c . . supia> jfeMt.--.Qf. A tla n ta M dtel Y» UfUldd 379 U.S.

241 (1964), District of Columbia v. ThMPgQB 346 U.S. 100 (1953),

20

Griggs v. Duke Power Co.. 401 U.S. 424 (1971) and.

459 F. 2d 205 (4th Cir. 1972), cert. den. 409 U.S. 934 (1972). In short,

while the Courts have interpreted the Constitution as providing the maximum

possible freedom from unnecessary or unreasonable governmental limitations

on private activity, they have come to view the freedom to discriminate

against black persons as a practice which must give way to the public policy

reflected in anti-discriminati.on laws, and they have done so because the

minimal limitations of these laws are clearly justified by the legislatively-

recognized need to take steps against the persistent and devastating dis

crimination against blacks by white people and white institutions which has

plagued America for so long.

CONCLUSION

For the reasons set forth above, in addition to the reasons set

forth in appellees' brief, amici curiae ask that the decision of the Court

helow be affirmed.

Respectfully submitted,

Thomas J. Sdhwab

6l6 Investment Building

Washington, D. C. 20005

783-8730

Attorney for amici curiae

January 25, 1974