McCord v. City of Fort Lauderdale, Florida Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants

Public Court Documents

July 8, 1985

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. McCord v. City of Fort Lauderdale, Florida Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants, 1985. 1bbc5472-bc9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c379fd44-0c09-4a65-8f4f-3c065e1b03e9/mccord-v-city-of-fort-lauderdale-florida-brief-for-plaintiffs-appellants. Accessed February 17, 2026.

Copied!

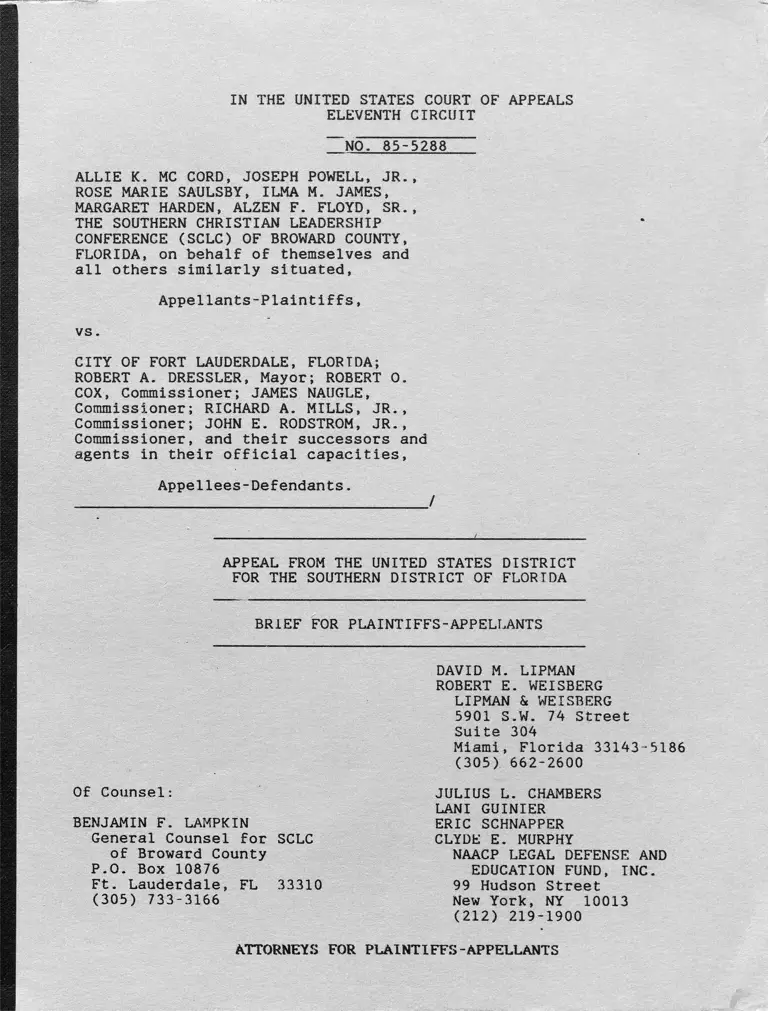

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

ELEVENTH CIRCUIT

NO. 85-5288

ALLIE K. MC CORD, JOSEPH POWELL, JR.,

ROSE MARIE SAULSBY, ILMA M. JAMES,

MARGARET HARDEN, ALZEN F. FLOYD, SR.,

THE SOUTHERN CHRISTIAN LEADERSHIP

CONFERENCE (SCLC) OF BROWARD COUNTY,

FLORIDA, on behalf of themselves and

all others similarly situated,

Appellants-Plaintiffs,

vs .

CITY OF FORT LAUDERDALE, FLORIDA;

ROBERT A. DRESSLER, Mayor; ROBERT 0.

COX, Commissioner; JAMES NAUGLE,

Commissioner; RICHARD A. MILLS, JR.,

Commissioner; JOHN E. RODSTROM, JR.,

Commissioner, and their successors and

agents in their official capacities,

Appellees-Defendants.

______________________________________/

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF FLORIDA

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

DAVID M. LIPMAN

ROBERT E. WEISBERG

LIPMAN & WEISBERG

5901 S.W. 74 Street

Suite 304

Miami, Florida 33143-5186

(305) 662-2600

JULIUS L. CHAMBERS

LANI GUINIER

ERIC SCHNAPPER

CLYDE E. MURPHY

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATION FUND, INC.

99 Hudson Street

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-1900

ATTORNEYS FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

Of Counsel:

BENJAMIN F. LAMPKIN

General Counsel for SCLC

of Broward County

P.O. Box 10876

Ft. Lauderdale, FL 33310

(305) 733-3166

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

ELEVENTH CIRCUIT

NO. 85-5288

ALLIE K. MC CORD, JOSEPH POWELL, JR.,

ROSE MARIE SAULSBY, ILMA M. JAMES,

MARGARET HARDEN, ALZEN F. FLOYD, SR.,

THE SOUTHERN CHRISTIAN LEADERSHIP

CONFERENCE (SCLC) OF BROWARD COUNTY,

FLORIDA, on behalf of themselves and

all others similarly situated,

Appellants-Plaintiffs,

v s .

CITY OF FORT LAUDERDALE, FLORIDA;

ROBERT A. DRESSLER, Mayor; ROBERT 0.

COX, Commissioner; JAMES NAUGLE,

Commissioner; RICHARD A. MILLS, JR.,

Commissioner; JOHN E. RODSTROM, JR.,

Commissioner, and their successors and

agents in their official capacities,

Appellees-Defendants.

_________________________________ ____/

APPEAL FROM THE UNITED STATES DISTRICT FOR THE SOUTHERN DISTRICT OF FLORIDA

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

Of Counsel:

BENJAMIN F. LAMPKIN

General Counsel for SCLC

of Broward County

P.O. Box 10876

Ft. Lauderdale, FL 33310

(305) 733-3166

DAVID M. LIPMAN

ROBERT E. WEISBERG

LIPMAN & WEISRERG

5901 S.W. 74 Street

Suite 304

Miami, Florida 33143-5186

(305) 662-2600

JULIUS L. CHAMBERS LANI GUINIER

ERIC SCHNAPPER

CLYDE E. MURPHY

NAACP LEGAL DEFENSE AND

EDUCATION FUND, INC.

99 Hudson Street

New York, NY 10013

(212) 219-1900

ATTORNEYS FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS

CERTIFICATE OF INTERESTED PERSONS

[LOCAL RULE 22(f)(2)]

The undersigned counsel of record for Plaintiffs-Appellees

certifies that the below listed persons have an interest in the

outcome of this case. These representatives are made in order that

the Judges in this Court may evaluate possible disqualifications or

recusal pursuant to Local Rule 22(f)(2).

PLAINTIFFS-APPELLEES

ALLIE K. MC CORD

JOSEPH POWELL, JR.

ROSE MARIE SAULSBY

ILMA M. JAMES

MARGARET HARDEN

ALZEN F. FLOYD, SR.

THE SOUTHERN CHRISTIAN LEADERSHIP CONFERENCE (SCLC) OF BROWARD COUNTY, FLORIDA

ALL OTHER BLACK CITIZENS OF FORT LAUDERDALE, FLORIDA WHO ARE MEMBERS OF PLAINTIFFS' CLASS

DEFENDANTS-APPELLANTS

CITY OF FORT LAUDERDALE, FLORIDA

ROBERT A. DRESSLER

ROBERT 0. COX

JAMES NAUGLE

RICHARD A. MILLS, JR.

JOHN E. RODSTROM, JR.

-i-

This appeal is not entitled to preference.

STATEMENT REGARDING PREFERENCE

[LOCAL RULE 22(f)(2)]

STATEMENT REGARDING ORAL ARGUMENTS

[LOCAL RULE 22(f)(2)]

Pursuant to Local Rule 22(f)(4), Plaintiffs-Appellants

respectfully request that this appeal be orally argued.

This case presents important questions regarding the proper

interpretation of Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, as

amended, 42 U.S.C. §1973, and whether the Congressional intent of

the amendment of that Act will be properly applied by the Courts of

this Circuit. We submit that the District Court below in finding

for the Defendant City of Fort Lauderdale, Florida, drew legal

conclusions, which are inconsistent with both Congress' intent when

amending the Act in 1982 to provide a broad charter against all

systems that diminish minority voting strength, and the express

holdings of this Court in applying the requirements of the Act.

Plaintiffs-Appellants submit that oral argument would clarify

the presentation of the legal arguments raised in this appeal.

-ii-

TABLE OF CONTENTS

CERTIFICATE OF INTERESTED PERSONS -i-

STATEMENT REGARDING PREFERENCE -ii-

STATEMENT REGARDING ORAL ARGUMENTS -ii~

TABLE OF CONTENTS -iii-

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES -vii-

ABBREVIATIONS -xii-

STATEMENT OF THE ISSUES 1

STATEMENT OF THE CASE 1

COURSE OF PROCEEDINGS AND 1

DISPOSITION IN THE COURT BELOW

A. PROCEDURAL BACKGROUND 1

B. THE DISTRICT COURT'S OPINION 2

STATEMENT OF THE FACTS 3

A. GENERAL BACKGROUND 3

B. THE BLACK CANDIDATES: 1957-1982 6

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT 13

STATEMENT OF JURISDICTION 15

ARGUMENT i6

I. THE CONTROLLING STANDARD OF REVIEW 16

1. THE "CLEARLY ERRONEOUS" STANDARD 16

OF REVIEW DOES NOT APPLY TO FINDINGS

DERIVED FROM AN IMPROPER LEGAL STANDARD

2. APPLICATION OF THIS STANDARD OF REVIEW 16

II. FT. LAUDERDALE'S AT-LARGE ELECTION SYSTEM 19

VIOLATES SECTION 2 OF THE VOTING RIGHTS ACT

BECAUSE IT RESULTS IN DISCRIMINATION AND

DENIES BLACK CITIZENS AN EQUAL OPPORTUNITY

TO ELECT CANDIDATES OF THEIR CHOICE

Page No.

-iii-

Page No.

1. HISTORY OF OFFICIAL DISCRIMINATION 20

AND ITS LINGERING EFFECTS

A. THE HISTORY 20

B. PRESENT EFFECTS OF THIS PAST HISTORY 22

(1) Residential Segregation 22

(2) Imbalance of Blacks on 23

City Boards and Committees

(3) Employment 24

(4) Public Housing 24

(5) Education 24

2. RACIAL POLARIZED VOTING 27

A. PLAINTIFFS' PROOF OF 28

RACIAL POLARIZATION

(1) THIS COURT'S STATISTICAL METHODS 28

USED FOR GAUGING RACIAL POLARIZATION

(a) BI-VARIATE REGRESSION ANALYSIS 28

(b) RACIAL POLARIZATION INDEX 30

(c) SUPPORT FOR WINNING CANDIDATES 31

(d) BLACKS' IMPACT ON THE 32

OUTCOME OF ELECTIONS

(e) AVERAGE NUMBER OF VOTES 32

CAST BY VOTERS

(e) VOTING ALONG RACIAL LINES 33

(2) NON-STATISTICAL METHODS OF 35

PROVING RACIAL BLOC VOTING

B. THE TRIAL COURT ERRONEOUSLY DISREGARDED 36

PLAINTIFFS' POLARIZATION EVIDENCE

(1) THE BI-VARIATE ANALYSIS WAS 36

DISREGARDED FOR IMPROPER REASONS

(2) THE POLARIZATION INDEX WAS 37

DISREGARDED FOR IMPROPER REASONS

-iv-

(3) PLAINTIFFS * OTHER STATISTICAL 39

POLARIZATION ANALYSES WERE

ERRONEOUSLY REJECTED

C. MULTI-VARIATE REGRESSION ANALYSIS 40

(1) THE MULTIVARIATE REGRESSION WAS 42

ERRONEOUSLY UTILIZED IN THIS

CASE SINCE IT HAS BEEN SPECIFICALLY

REJECTED BY THE SUPREME COURT AND

IS INCONSISTENT WITH CONGRESS'

MANDATE IN AMENDING THE VOTING RIGHTS ACT

(a) THE SUPREME COURT HAS REJECTED 42

UTILIZATION OF THE MULTIPLE

REGRESSION ANALYSIS

(b) INQUIRY AS TO THE RACIAL MOTIVE 43

OF THE VOTER IS INCONSISTENT WITH

CONGRESS' MANDATE IN AMENDING

THE VOTING RIGHTS ACT

(2 ) THE DISTRICT COURT'S ADOPTION OF 45

DEFENDANT'S MULTIVARIATE ANALYSIS

IGNORES THE METHODOLOGICAL PROBLEMS

RAISED BY THIS APPROACH

(a) THE

ARE

PROBLEM OF INCLUDED -

WHICH FACTORS

OR - EXCLUDED

46

(b) THE PROBLEM OF QUANTIFICATION 47

(c) THE PROBLEM OF MULTICOLLINEARITY 48

((D) INCUMBENCY 50

((2)) CAMPAIGN CONTRIBUTIONS 51

(3) THE RESULTS OF THE MULTI-VARTATE 53

ANALYSIS DO NOT REFLECT THE "ACTUAL

EVENTS AND REALITIES" OF FT. LAUDERDALE

POLITICS

3. STRUCTURE OF THE ELECTION SYSTEM 55

A. LACK OF RESIDENCY REQUIREMENT 56

B. UNUSUALLY LARGE POPULATION SIZE 57

4. CANDIDATE SLATING PROCESS 58

Page Mo. .

5. SOCIO-ECONOMIC STATUS 60

6. THE EXTENT TO WHICH MINORITY 63

GROUPS HAVE BEEN ELECTED TO

PUBLIC OFFICE IN THE CITY

7. UNRESPONSIVENESS 66

8. TENUOUSNESS 68

RELIEF AND CONCLUSION 70

CERTIFICATE OF SERVICE

APPENDIX

APPENDIX 1: OUTLINE OF THE HISTORY OF la

RACIAL DISCRIMINATION IN

FORT LAUDERDALE

APPENDIX 2: BI-VARIATE REGRESSION ANALYSIS lb

APPENDIX 3: RANKING OF BLACK CANDIDATES BY 1c

PRECINCT IN CITY COMMISSION

ELECTIONS

APPENDIX 4: RACIAL POLARIZATION INDEX Id

-vi-

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Case Law: Pages

Armstrong v. Collier536 F.2d 72 (5th Cir. 1976)

Bolden v. City of Mobile

423 F.Supp. 384 (S.D. Ala.1976) aff'd 571 F.2d 238 (5th Cir. 1978)

rev'd onother grounds 446 U.S. 55 (1980)

Bonner v. City of Prichard661 F.2d 1206 (11th Cir. 1981)

(en banc)

Boylan v. The New York Times

(unreported)

City of Rome v. United States

472 F.Supp. 221 (D.D.C. 1979)

(Three Judge Panel)

Civil Voters Organ, v. City of Terrell

565 F.Supp. 338 (N.D. Tex. 1983)

City of Mobile v. Bolden

446 U.S. 55 (1980)

David v. Garrison

553 F.2d 923 (5th Cir. 1977)

Dowdell v. City oF Apopka698 F.2d 1181 (11th Cir. 1983)

Gingles v. Edminsten

590 F.Supp. 345 (E.D. N.C. 1984)

(Three Judge Panel)

Graves v. Barnes343 F. Supp. 704 (W.D. Tex. 1972)

Hicks v. Miranda

422 U.S. 332 (1975)

Howell v. Jones

516 F.2d 53 (5th Cir. 1985)

In Re Apportionment Law, etc.

414 So.2d 1040 (Fla. 1982)

James v. Stockham Valve Co.

559 F.2d 310 (5th Cir. 1977)

70

19, 27

29

28

30, 35

22, 62

19, 27

57

22

30, 32, 33, 43

65

65

43

43

69

49

-vii -

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

[cont * d ]

Case Law: Pages

Johnson v. Uncle Ben's, Inc. 16

628 F.2d 429 (5th Cir. 1980), vacated

on other grounds 451 U.S. 902 (1981)

Jones v. City of Lubbock 21, 27, 28

727 F.2d 364 (5th Cir. 1984) 37, 42, 45

denial of re-hearing and rehearing en banc 57, 62, 67

730 F.2d 233 (5th Cir. 1984)

*Jordan v. Winter 42

Civil No. GC 82-80-WK-0 (N.D. Miss.

April 16, 1984) aff'd sub, nom.

Mississippi Republican Executive Committee

v. Brooks

__ U.S.____, 83 L.Ed.2d 343 (1984)

Kelly v. Southern Pacific Co. 16

419 U.S. 318 (1974)

Kendrick v. Walden 58

527 F.2d 44 (7th Cir. 1975)

Kirksey v. Board oF Supervisors of Hinds 61

County

554 F.2d 139 (5th Cir. 1977) (en banc)

cert, denied 434 U.S. 968 (1977)

Lee County Branch, NAACP v. City of Opelika 30

748 F.2d 1473 (11th Cir. 1984)

Lincoln v. Board of Regents of Univ. System 16

697 F.2d 928 (11th Cir. 1983)

Major v. Treen 30, 65

574 F.Supp. 325 (E.D. La. 1983)

Mandel v. Bradley 43

432 U.S. 173 (1977)

Matter of Legal, Braswell Government Securities 70

648 F.2d 321 (5th Cir. 1981) (Unit B)

^McMillan v. Escambia County, Fla. 17, 21, 23, 26,

638 F.2d 1239 (5th Cir. 1981) 27, 29, 35, 58

(McMillan I); aff'd 688 F.2d 960 (5th Cir. 1982) 62-65, 67, 69

(McMillan II); vacated and remanded

__U.S__, 80 L.Ed 2d 36 (1984) aff'd

748 F.2d 1037 (5th Cir. 1984) (McMillan III)

-viii-

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

[cont'd]

NAACP by Campbell v. Gadsden County

691 F.2d 978 (11th Cir. 1982)

Nevitt v. Sides

571 F.2d 209 (5th Cir. 1978)

cert, denied 446 U.S. 951 (1980)

Noritake Co., Inc, v. M/V Hellenic Champion

627 F.2d 724 (5th Cir. 1980).

Pavlides v. Galveston Yacht Basin, Inc.

727 F.2d 330 (5th Cir. 1984)

Perkins v. City of West Helena

675 F.2d 201 (8th Cir. 1981)

aff *d 459 U.S. 801 (1982)

Pullman-Standard v. Swint

450 U.S. 273 (1982)

Rodgers v. Lodge

458 U.S. 613 (1982)

Rybicki v. State Board of Elections of Illinois

574 F. Supp. 1147 (N.D. 111. 1983)

Segar v. Smith

738 F.2d 1249 (D.C. Cir. 1984)

Steward v. Waller

404 F. supp. 206 (N.D. Miss. 1975)

Teamsters v. U.S.

431 U.S. 734 (1977)

U.S. v. United Brothers of Carpenters and

Joiners of America. Local 169

457 F.2d 210 (7th Cir. 1972)

United Jewish Organization v. Carey 430 U.S. 144 (1977)

United States v. City of Fort Lauderdale

No. 80-6289-CIV-ALH (S.D. 1980)

^United States v. Dallas County Commissioners

739 F.2d 1529 (11th Cir. 1984)

Case Law:

27, 39, 30, 35

65, 66, 68

27

16

16

35, 59, 67

16

21, 23, 24, 35

40, 56

65

50

65

28

58

35

24, 66

17-19, 21, 26,

27, 30, 37, 45,

57, 62-64

Pages

-ix-

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

[cont'd]

Case Law: Pages

United States v. General Motors

384 U.S. 127

^United States v. Marengo County Commission

732 F.2d 1546 (11th Cir. 1984)

appeal dismissed and cert, denied

__U.S.__, 83 L.Ed 2d 311 (1984)

Valentino v. United States Postal Service

674 F.2d 56 (1982) (D.C. Cir. 1982)

Voter Information Project v. City of

Baton Rouge, 612 F.2d 208 (5th Cir. 1980)

Vuyanich v. Republic Nat. Bank of Dallas

505 F.Supp. 224 (N.D. Tex. 1980)

vacated on other grounds 723 F.2d 1195

(5th Cir. 1984)

Wallace v. House515 F. 2d 619 (5th Cir. 1975)

White v. Regester 412 U.S. 755 (1972)

Wilkins v. Univ. of Houston

654 F.2d 388 (5th Cir. 1981), reh'g denied

662 F.2d 1156 (5th Cir. 1981)

Wise v. Lipscomb

399 F.Supp. 782 (N.D. Tex. 1975) rev*d on other grounds, 551 F.2d 1043

(5th Cir. 1977) rev'd on other grounds,

437 U.S. 535 (1978)

Zimmer v. McKeithen

485 F.2d 1297 (5th Cir. 1973)

(en banc), aff'd on other grounds

sub, nom. East Carroll Parish School Board v.

Marshall, 424 U.S. 636 (1976).

16

16-■19, 21, 25

26,, 36 ,, 57--60

62--66, 68, 70

50

35

50

65

18, 59-61, 65

28

22

65

-x-

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

[cont'd]

Pages

U.S. Constitutional Provisions, Statutes and Rules

28 U.S.C. § 1291 15

42 U.S.C. §1973 (Voting Rights Act) 1, 2, 14, 19

Senate Report No. 97-417

97th Cong. 2d Sess., (1982)

U.S. Code Cong, and Admin. News 1982, Pgs. 177-410

17, 44, 61, 62,63

Rule 23(b)(2) F.R.C.P. 1

Rule 52(a) F.R.C.P. 16

F.R.E. 201(b)(2) 58

Florida Constitutional Provisions and Codes:

Fla. Statutes §§10.101-10.103 69

Fla. Statutes §124.011 69

Fla. Statutes §230.105 69

Florida Constitution, Article 8, §5 69

Additional Authority:

Finkelstein, The Judicial Reception of

Multiple Regression Studies in Race and Sex Discrimination Cases

80 Columbia L. Rev. 737, 738-742 (1980)

50

C. Wright, Law of Federal Courts

495 (2d Ed. 1970)

D. Baldus & J. Cole, Statistical Proof of

Discrimination ('1980') and (1983 Supp.'*

43

4848

ABBREVIATIONS

We utilize the following references in our Brief:

Vol.__, Pg._

Tr.Vol.__, Pg.

RE.Pg.__

RE,Op., Pg.

P.Ex.

D.Ex.

Referring to one of the Volumes (Vol.

1-6), Pages 1-1482, consecutively

consisting of all pleadings,

memoranda, other submissions and Court

Orders.

Referring to one of the seven (7)

volumes (Vol. 7-13) of trial testimony.

Record Excerpts

Opinion of March 12, 1985 (on the

merits of this case)

Plaintiffs' Exhibit

Defendant's Exhibit

-xii-

STATEMENT OF THE ISSUES

I.

Whether the District Court failed to apply the proper legal

standards mandated by Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, as

amended, in rejecting Plaintiffs* claims that '’based on the totality

of circumstances" the Ft. Lauderdale at-large election system

results in an abridgement of black citizens' opportunity "to

participate in the political process and to elect representatives of

their choice." 42 U.S.C. §1973.

II.

Assuming error has occurred by the District Court, is reversal

rather than remand appropriate since the essential facts of this

case are not in dispute and, when the record evidence is considered

in its entirety, there exist no genuine issues as to any material

fact.

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

COURSE OF PROCEEDINGS AND DISPOSITION IN COURT BELOW

A. PROCEDURAL BACKGROUND

Plaintiffs, six black citizens of Fort Lauderdale and the

Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC) of Broward County,

1 /Florida, filed this lawsuit as a class action on March 10, 1983,

1/ The case was certified as a class action at the commencement of

trial on September 26, 1984, pursuant to Rule 23(b)(2) F.R.C.P.

Plaintiffs' class consists of "all black citizens who reside in the City of Fort Lauderdale." (Vol. 4, Pg. 852).

alleging that Fort Lauderdale's at-large election system for

electing City Commission members unlawfully dilutes black voting

strength and has a discriminatory result in violation of Section 2

of the Voting Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. §1973 (West Supp. 1983).

Defendants are the City of Fort Lauderdale and Mayor,

Vice-Mayor, Mayor Pro-Tem, and two additional Commissioners, all

sued in their official capacity (1(5, Complaint) (RE, Pg. 6).

2/Following extensive discovery by both parties , which led to

the stipulation of the parties to virtually all of the essential

facts of the case, see, infra, Pg. 18, n. 13, this case was tried

without jury commencing on September 26, 1984, and continued

intermittently over several weeks.

B. THE DISTRICT COURT'S OPINION

On March 12, 1985, the trial court issued its Opinion (RE, Op.,

Pg. 25-62) ruling that Plaintiffs had failed to prove a violation of

2/ Several Motions resolved prior to trial included Defendants'

Motion to Dismiss filed on June 20, 1983 based in part on its view

that Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act is unconstitutional (Vol. 1,

Pgs. 204-205; Vol. 2, Pgs. 286A-286FFF).

On February 16, 1984, the trial court denied the City's request for a dismissal on the constitutionality issue ruling:

[T]he motion of defendants to declare the Section 2 of

the Voting Rights Act unconstitutional is denied

without prejudice. The court sees wisdom in the

prospect of allowing the record to ripen with respect

to this issue.

(Vol. 2, Pg. 604)

No subsequent Order following the "ripening of the record" has

been issued by the District Court relating to the constitutionality of the Voting Rights Act.

-2-

Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act and entered a Final Judgment for

the Defendants on March 30, 1985 (RE, Pg. 24).3/

STATEMENT OF THE FACTS 4/

A. GENERAL BACKGROUND

Fort Lauderdale was incorporated in 1911 (P.Ex. 2). According

3/ The Trial Court, void of any legal authority, makes four outcome

determinative conclusions as to the governing time frame to assess evidence in this case.

First, the Trial Court essentially disregards nine unsuccessful

pre-1971 black candidacies by restricting its view to elections

between 1971 and 1982 because it found "serious efforts in a black

candidacy began about that time." (RE,Op., Pg. 26)

Secondly, while wiping the slate clean of nine pre-1971

candidacies, notwithstanding its own view that 1985 election results

could affect the Court's decision, the Court purposefully avoided

consideration of the three unsuccessful 1985 black candidates. See,

Order of March 11, 1985 (RE, Pg. 23). ("Because of the desire of

this Court that this opinion and decision would neither affect this

year's City elections, nor be affected by the final results, the

Court is entering this opinion on the late afternoon of the day of the general election.")

By limiting its review to black candidates between 1971 and

1982, the Court only reviewed four of the thirteen black candidates,

or seven of nineteen black candidacies. See, infra, Pgs. 63-64.

Third, for purposes of concluding that blacks have exceeded "pr

oportional representation," Judge Roettger applies the 1970

population data (14.69% black), rather than the 1980 census data

(21% black), or on the average for the past several decades (average from 1930 to 1980: 22% black) (RE,Op. Pg. 61).

Fourth, in considering the responsiveness factor, the Court

focuses on the City's efforts since 1980 to achieve employment

opportunities for blacks. (RE,Op., Pgs. 53-55) Notwithstanding the

fact that since June 17, 1980, the City of Ft. Lauderdale has been

under a Federal Court Order to improve hiring and promotional

opportunities for blacks in the City's police and fire departments. (P.Ex. 23)

4/ This section briefly summarizes the facts presented at trial.

In the interest of fully exploring the objective legal factors which

Congress listed as probative of a Section 2 violation in the context

of the facts in this case, rather than in isolation, many of the

undisputed and underlying facts are discussed in greater detail in

the Argument section.

-3-

to the 1980 Census, its population totals 153,279 persons, of whom

21% or 32,225 are black (P.Ex. 15, Tab 1). Although the de jure

residential segregation imposed by the City of Ft. Lauderdale was

repealed in 1948, see, infra, Pg. 22, its impact on residential

segregation has endured (Tr.Vol. 9, Pg. 464; Tr.Vol. 10, Pgs.

127-28). Ft. Lauderdale's most striking demographic characteristic

is its extreme degree of residential segregation. Blacks today in

Ft. Lauderdale are highly concentrated, wedged literally between two

sets of railroad tracks, in the northwest quadrant of the City. The

relationship between the prior de jure and present segregation is

evidenced by the fact that approximately 87.2% of all black

residents in the city (P.Ex. 29). This concentration is literally

within, adjoining, or adjacent to the boundaries of the 1941 legally

segregated "Negro district" (Ibid.), created through a series of

municipal segregation ordinances.5 ̂ The differences between the

segregated black residential community in the northwest and the

white community elsewhere are more than simply racial. Blacks, as

compared to their white counterparts, are poorer; are significantly

less educated; are grouped in lower level menial employment

5/ The City's legal efforts to segregate blacks began in 1922 (P.

Ex. 6, Tab A, Ord. No. 140); continued in 1926 (P. Ex. 3, Fact 4,

Ord. No. 470); were publicly enforced in 1929 (P. Ex. 3, Fact 18);

were redefined in 1936 (P. Ex. 3, Fact 76, Ord. No. 820); were

redefined in 1939 (P. Ex. 3, Fact 34, Ord. No. 983); were redefined

again in 1939 (Ord. No. 1005); were publicly enforced in 1939 (P.

Ex. 3, Facts 34, 37); and were reinforced and redefined with two

ordinances in 1941 (P. Ex. 3, Facts 45, 46, Ord. Nos. C-48 and

C-51). In 1942, the City attempted to create a permanent buffer

zone to surround the black community (P. Ex. 3, Facts 48, 51).

-4-

positions; and are more likely to live in slum and otherwise over

crowded living conditions.^

Under Fort Lauderdale's election system, city commissioners run

in a primary and then in a general election. The 10 candidates who

obtain the highest number of votes in the primary qualify for the

general election; and the 5 candidates who receive the highest

number of votes in the general election become city commissioners.

Each voter may vote for up to 5 candidates in each of the elections

(P.Ex. 2, Fact 12). All commissioners run at-large with no

subdistrict or ward residency requirement (P.Ex. 2). Despite the

fact that Ft. Lauderdale historically has been and is presently more

than 20% black (P.Ex. 15, Tab 1), the City Commission was all white

6/ The following socio-economic disparities are revealed in 1980

Census data:

Income: In 1979, the average median income for all families inFort Lauderdale was $15,410, while the median income for black

families was $9,761 (P. Ex. 15, Tab 5).

Education: As of 1980, one of every three (33%) black adults

had an eighth grade or less education as compared to only one of

every 10 (10%) white adults (P. Ex. 15, Table 3). Over 42% of white

adults had received some college education as compared to only 13%

of black adults and similarly, approximately 21% of white adults had

four years of college as compared to only 4.1% of black adults (P.

Ex. 15, Tab 3).

Employment Status: Approximately 28% of the white work force

hold professional and executive type positions as compared to 10% of

the blacks (P. Ex. 15, Tab 4). On the opposite end of the scale,

nearly one in every three blacks works in service occupations (P.

Ex. 15, Tab 4).

Living Conditions: Black households in Fort Lauderdale are

nearly twice as likely to be renters as opposed to home owners, as

61% of white households live in homes they own as opposed to 30% of

black families (P. Ex. 15, Tab 6). Black households also are more

likely to occupy overcrowded living conditions and live in slum and

blighted areas (P. Ex. 18, Tab 7), ( Vol. IV, Pg. 122).

-5-

from 1911, the date of its incorporation, until 1973 when the first and

only black was elected to city office (P.Ex. 5, 13). The black

commissioner elected in 1973, Andrew DeGraffenreidt, was re-elected for

two additional commission terms in 1975 and 1977 before being defeated

in 1979. No black candidate, other than Mr. DeGraffenreidt, has been

elected, notwithstanding efforts by 12 other black candidates spanning

a 28 year period between 1957-1985.^ (P.Ex. 25).

B. THE BLACK CANDIDATES: 1957-1982

(i) 1957-1967

In 1957, Nathaniel Wilkerson, the first black candidate to run for

City Commission, announced his candidacy by stating that: "he hope(d)

to serve as a link between the negro population and the City

government." (P.Ex. 14A, March 4, 1957). Although unsuccessful in both

7/ On March 12, 1985, the same day the trial court issued its Order

and Opinion in this lawsuit, two additional black candidates, Beau

Cummings and Leola McCoy lost their bid for election to the City

Commission thus assuring the continuation of an all-white Commission

through 1987 (Vol. 5, Pgs. 1190-1230; Vol. 6, Pgs. 1231-1461). A third

additional black candidate, Henry L. Scurry, lost in his bid for

election when he was eliminated in the February 12, 1985 primary

election (Vol. 5, Pgs. 1194-1219; Vol. 6, Pg. 1335).

On March 22, 1985, ten days after the trial court issued its

opinion and order and five days prior to the Court's entry of Final

Judgment (RE,Pg. 24), Plaintiffs supplemented the record with certified

copies of voter registration and election data corresponding to the

February 12, 1985 primary and March 12, 1985 general City Commission

elections (Vol.6, Pgs. 1241-1461). The record was also supplemented

with affidavits from the unsuccessful black candidates Beau Cummings

(Vol.6, Pgs. 1221-1225) and Leola McCoy (Vol.6, Pgs. 1227-1231), and

with an affidavit from Dr. Rudolph 0. de la Garza, the political

scientist who also testified at trial. Dr. de la Garza's affidavit

describes the statistical relationship between the race of the voter

and the race of the candidate in the 1985 primary and general elections

(Vol.5, Pgs. 1194-1219).

-6-

his 1957 and 1959 campaigns, Wilkerson received overwhelming support

from all the City "negro precincts" (P.Ex. 14A, April 10, 1957; April

29, 1959), (P.Ex. 25, Table 3).

Now Judge, then lawyer Thomas Reddick was the second black to seek a

position on the Ft. Lauderdale City Commission, running in 1963 and

again in 1967. Despite his qualifications, which ultimately led to his

appointment as the first black Circuit Judge not only in Broward County

but throughout the State of Florida (Tr. Vol. 11, Pg. 245), and signifi

cant support from the black electorate, Judge Reddick received less than

minimal support from white voters in Ft. Lauderdale (P. Ex. 25, Table 3).

In 1967, blacks developed a campaign strategy in which five blacks

ran for the Commission (Tr.Vol. 8, Pgs. 221-222). Alcee Hastings, an

architect of that strategy, explained that the five black candidate

strategy was undertaken to encourage black turnout (Tr.Vol. 8, Pgs.

336-38; P. Ex. 34, Pgs. 36-38). While it did not result in the election

of any black commissioners, this strategy led to increased black voter

turnout in subsequent elections.

(ii) 1969-1971: ALCEE HASTINGS

In 1969 and again in 1971, United States District Court Judge Alcee

Hastings, then an attorney in private practice in Ft. Lauderdale, ran

for the City Commission. Judge Hastings, who had waged prior campaigns

for the Florida House of Representatives, the Florida Senate, the State

Public Service Commission and the United States Senate, was one of the

most politically experienced candidates for City office (Ibid., Pgs.

8-10). However, notwithstanding this broad political experience, Judge

Hastings found his ability to raise funds and campaign in the white

community severely limited (Ibid., Pgs. 11, 19-20, 29, 72).

-7-

Judge Hastings’ testimony that he had lost the election because

he is black (Ibid., Pgs. 13, 47-48) is corroborated by the results

of the election. In 1971, he received a vote from virtually every

black (98%) who walked into the polling booth, but received a vote

from less than one-third of the white voters (31.9%) (P. Ex. 38).

Measured by the bi-variate regression analysis, his support from

blacks was literally perfect (R-2 = .99) (P. Ex. 25, Table 2); and

while he finished first among the candidates in every one of the 7

black precincts, he failed to finish among the first 5 candidates in

any of the 52 white precincts (P. Ex. 25, Table 3).8^

C iii) 1973: DeGRAFFENREIDT

In 1973, Andrew DeGraffenreidt became the first and only black

ever to be elected to the City Commission. However, the

circumstances of his election were so unique that they have never

been duplicated by any other black candidate.

First, an unprecedented 31 candidates ran in the 1973 primary.

This was a significantly larger field of candidates than in any

other prior or subsequent election (P.Ex. 1, Pgs. 84-85, 112-113,

126-127, 138, and 148). This large primary field was significant

for DeGraffenreidt's purposes since it effectively fragmented the

white electorate's votes among the 30 other white candidates

8/ Judge Hastings' record black support (the 98% support figure is

unequaled by any black or white candidate in any other election

between 1971-1982) occurred in the context of a black electorate

that "single-shot'' voted and thereby forfeited 3 of their 5 votes in

an attempt to elect a candidate of their choice (P. Ex. 25, Table

1); and a turnout of black voters (38.5%) that was 80% higher than

the white turnout in 1971 (21.4%) (P. Ex. 25A). Indeed, this black

turnout has never been equaled in the white community in any of the

twelve (12) elections between 1971-1982 (P. Ex. 25A).

-8-

(Tr.Vol. 7, Pgs. 56-57, enabling DeGraffenreidt as the sole black

candidate to take full advantage of his consolidated black support.

Second, but equally significant, was the fact that, in 1973, two

incumbents chose not to run for re-election, thus creating 2 new

vacancies on the City Commission (Ibid.., Pgs. 61-62).

Building on this fortuitous set of circumstances, DeGraffenreidt

devised a campaign strategy which sought to minimize the likely

rejection of a black candidacy by the white community while

maximizing his support in the black community. As part of this

strategy, DeGraffenreidt intentionally sought to mask his racial

identity in the white community. Thus, capitalizing on that fact

that his last name did not readily identify his race, he campaigned

in the white community in a manner which deliberately did not reveal

that he was black. (Ibid., Pg. 52). See also. Testimony of

Defendants’ expert, Dr. Bullock (Tr. Vol. 12, Pg. 448).

DeGraffenreidt used two sets of campaign literature: one set,

distributed in the white community without his picture; and another,

distributed in the black community which included his picture (Tr.

Vol. I, Pgs. 51-52, 112). See also, Testimony of Plaintiffs'

expert, Dr. de la Garza (Tr.Vol. 8, Pgs. 234-236). Like all viable

candidates must, DeGraffenreidt ran a newspaper ad with his

picture. This single ad, however, did not affect his overall dual

strategy. In addition, while campaigning in the white community,

DeGraffenreidt employed, as he explained, a "third person" campaign

style in which he asked white voters to "support Andy DeGraffenreidt

for the Fort Lauderdale City Commission" but never made it clear

that he was referring to himself (Tr. Vol. 7, Pgs. 52-53; Tr. Vol.

8, Pgs. 220-223).

-9-

DeGraffenreidt's low profile in the white community contrasted

sharply with his extensive efforts in the black community. Critical

to the campaign was DeGraffenreidt's successful effort in getting

black voters to turn out in unprecedented numbers (Tr. Vol. 7, Pgs.

46-47, 58, 67). The 41.8% turnout of registered black voters was

27% greater than the white turnout in that election and 122% larger

than the average white turnout (18.8%) in the 12 elections between

1971-1982 (P. Ex. 25A). This record black turnout translated

directly into votes for DeGraffenreidt, as 96.9% of all black voters

cast a vote for him, a rate 3 times greater than that of white

voters (32% of whom cast a vote for DeGraffenreidt) (P. Ex. 36).

DeGraffenreidt aggressively and successfully educated the black

electorate to the fact that, in the context of Ft. Lauderdale's

election system where each voter can cast 5 votes for various

candidates, black voters must forfeit 3 or more of their ballots--in

a manner unlike whites--in order for a black candidate to succeed

(Tr.Vol. 7, Pgs. 47-48) (By voting "beyond two you were voting

against your candidate."); (Tr.Vol. 8, Pg. 235). In the 1973

General election, the white electorate cast on the average more than

four ballots (4.3) in contrast to blacks, who on the average cast

less than two (1.7) (P.Ex. 25, Table 1).

Civ) 1975-1977: DeGRAFFENREIDT

As the record below makes plain, DeGraffenreidt's incumbency in

1975 and 1977 placed his re-election on an altogether different

plane. The special status of incumbents, which was recognized by

both parties below, was enhanced by the fact that the individual

Commissioners ran as an incumbent team utilizing the structure of

-10-

the system to avoid head-to-head competition between one another.

As an incumbent, DeGraffenreidt embraced this strategy (Tr. Vol. 7,

9 /Pgs. 74-75), as did his colleagues.

As in 1973, in the 1975 and 1977 general elections the black

voter turnout was so high that its percentages were equaled in the

white community in only one election between 1971-1982 (P. Ex.

25A). Black voters continued to forfeit their available votes

casting half as many of the 5 available ballots as did white voters

(P. Ex. 25, Table 1). Most significantly, blacks, as in 1973, gave

DeGraffenreidt a significantly higher level of support than whites.

Indeed, his level of support among blacks was more than twice the

level of his support among whites. (P.Ex. 30). Re-elected in each

of the 1975 and 1977 elections, DeGraffenreidt continued his tenure

of office.

(v) 1979: DeGRAFFENREIDT

Ultimately, notwithstanding his incumbent status, DeGraffenreidt

lost his Commission seat due to a decrease in white support. In

1979, 92% of all black voters cast a vote for DeGraffenreidt, and,

9/ Various of DeGraffenreidt's contemporaries on the Commission

indicated their support of this team concept for re-election. See,

former Mayor Shaw's testimony (Tr. Vol. 11, Pg. 259; Dep. Pg. 26).

See also, contemporaneous comments from Shaw (P. Ex. 14A, Article of

March 9, 1977) ("I feel the team has been re-elected," Shaw said, "I

don't think any single commissioner or mayor can take credit for

singly being elected."), and Commissioner Mills (Ibid.) (Mills

agreed, "they've given us a vote of confidence-as a team. And we'll

give them the same dedicated type of government."); as well as press

endorsements reinforcing the same concept (D. Ex. 6-C, Pg. 6) ("We

recommend the voters stay with the incumbent five tomorrow as we can

see no reason to break up a 'winning team' nor do we believe that

any of the five opponents remaining offer the qualifications and

experience of the incumbents.").

-11-

he ranked first in every black precinct. In contrast, he ranked as

one of the top five vote getters in only 16 of 64 white precincts

(P. Ex. 25, Table 3).

While turnout of black voters in 1979 was lower than in the

past, 19.6%,^^ it was not significantly lower than the white

turnout for that year, 22.3% (P. Ex. 25A), and was slightly higher

than the average white turnout for the twelve elections that

occurred between 1971 and 1982, i.e., 18.8% (P. Ex. 25A). Thus, in

1979, the historical pattern of elections in Ft. Lauderdale

returned. Notwithstanding the overwhelming support of black voters,

the candidate of their choice, by virtue of his failure to obtain

the support of the majority group, failed to gain sufficient support

to win an election under Ft. Lauderdale's at-large system.

(vi) 1982

In 1982, two black candidates, Art Kennedy and Louis Alston, ran

unsuccessfully for the City Commission. Kennedy, an experienced

campaigner and politician, was a past president of the county-wide,

bi-racial Broward County Classroom Teachers Association and had run

for the Broward County School Board in 1976 (Tr. Vol. 11, Pgs.

310-315). Consistent with other black candidates, other than

10/ The election results plainly reflect that DeGraffenreidt's loss

was not attributable to the black turnout in his 1979 election

defeat. Had blacks turned out at the identical level as whites in

1979 and black voters had single-shot only one ballot for

DeGraffenreidt, he would have lost the election by 746 votes rather

than 870.

-12-

his 1982 opponent Alston, Kennedy finished first in all of the

black precincts but within the top 5 positions in only 13 of 64

white precincts (P. Ex. 25, Table 3). Moreover, 95% of all black

voters cast one vote for Kennedy in contrast to 31% of the white

12 /voters (P. Ex. 37).

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

This case challenges at-large City Commission elections in Ft.

Lauderdale for unlawful dilution of black voting strength. The

essence of a vote dilution claim is that, although there may no

longer be any formal barriers preventing minorities from

registering, voting, or running as candidates, the challenged

election system minimizes minority voting strength and denies

minority voters an equal opportunity to participate in the political

process and to elect candidates of their choice. See, Rogers v.

Lodge, 458 U.S. 613, 616-17 (1982); Ibid, at 616; "The minority's

voting power...is particularly diluted when bloc voting occurs and

ballots are cast along strict majority-minority lines." White v.

Regester, 412 U.S. 755, 765-66 (1973).

11/

11/ The second unsuccessful black candidate, Louis Alston, was within

the top 3 candidates in each of the 6 black precincts and would have

been successful in the election had he received an equivalent number

of votes in the white community.

12/ In Ft. Lauderdale's most recent City Commission election, held

just several months ago on March 12, 1985, the pattern developed over the past 28 years persists. Notwithstanding the overwhelming support

of black voters for the black candidates of their choice, the

candidates failed to gain sufficient support of the white electorate

and thus lost their bid for public office. (Vol. 5, Pg. 1200)

-13-

In 1982 Congress amended Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act of

1965 to eliminate the requirement of proving discriminatory intent

for a statutory violation. Section 2 now prohibits any electoral

system which "results” in racial discrimination by providing

minority voters "less opportunity" than whites "to participate in

the political process and to elect representatives of their

choice." 42 U.S.C. §1973 (West Supp. 1983).

The undisputed evidence in this record, when examined based on

the objective factors which Congress listed as probative of a

Section 2 violation, leads to the conclusion that black voters in

Ft. Lauderdale do not have equal access to the political process and

an equal opportunity to elect candidates of their choice: (1)

Florida and Ft. Lauderdale have an extensive past history of

official discrimination which continues to impair the present-day

ability of blacks "to participate on an equal footing in the

political process," infra, Appendix 1, Pgs. la-8a; (2) the

statistical evidence establishes a strong and persistent pattern in

City Commission elections of voting along racial lines, infra, Pgs.

28-35; (3) Ft. Lauderdale's large size and lack of any subdistrict

residency requirement has enhanced the discriminatory impact of the

at-large election system and increased the opportunity for

discrimination, infra, Pg. 55; (4) blacks have been consistently

denied access to Ft. Lauderdale's most successful candidate slating

group, infra, Pgs. 58-59; (5) black citizens are disadvantaged by

their depressed socio-economic status, infra, Pgs.60-62; (6) only

one black has ever been elected to the City Commission under the

at-large system in Ft. Lauderdale's 74-year history, infra, Pgs.

-14-

63-65 (7) Ft. Lauderdale City officials have historically been

unresponsive to the needs of Ft. Lauderdale’s black community, and

what measures that have been taken have been the result of Federal

requirement and litigation, infra. Pgs. 66-68; and, (8) Ft.

Lauderdale's continued utilization of an at-large system is contrary

to recent state policy initiatives aimed at increasing the

participation of Florida’s black citizens in the political process,

infra, Pgs. 68-69.

The evidence discloses a "system’’ which plainly "minimizes or

cancels out the voting strength and political effectiveness" of the

black community of Ft. Lauderdale. However, by ignoring

well-settled legal principles developed in this Circuit and others,

the District Court erroneously concluded a lack of violation under

the Voting Rights Act. This ultimate conclusion should be reversed

on appeal.

STATEMENT OF JURISDICTION

The jurisdiction of this Court is based upon 28 U.S.C. 1291,

which provides, in part, as follows:

The Courts of Appeals shall have jurisdiction of

appeals from all final decisions of the district

courts of the United States..., except where a direct

review may be had in the Supreme Court.

The appeal stems from a decision of the United States District

Court which is within the jurisdiction of the Eleventh Circuit Court

of Appeals.

-15-

ARGUMENT

I. THE CONTROLLING STANDARD OF REVIEW

1. THE "CLEARLY ERRONEOUS" STANDARD

OF REVIEW DOES NOT APPLY TO FINDINGS

DERIVED FROM AN IMPROPER LEGAL STANDARD

First and fundamentally, the Rule 52(a) F.R.C.P. "clearly

erroneous standard" applies to the appellate review of facts and

does not apply to conclusions of law. Pullman-Standard v. Swint.

456 U.S. 273, 287 (1982). Secondly, where the District Court's

findings are based on an erroneous view of the controlling legal

standards, the "clearly erroneous" rule does not apply, Swint,

supra, 456 U.S. at 287, and the findings may be set aside on that

basis. Kelly v. Southern Pacific Co., 419 U.S. 318, 323 (1974);

United States v. General Motors, 384 U.S. 127, 141 n. 16 (1966).

In other words, the "clearly erroneous" standard "does not

insulate factual findings influenced by legal error." Lincoln v.

Board of Regents of Univ. System, 697 F.2d 928, 938, n. 13 (11th

Cir. 1983); Johnson v. Uncle Ben's, Inc., 628 F.2d 429, 422 (5th

Cir. 1980), vacated on other grounds, 451 U.S. 902 (1981). Thus,

where a finding of fact is "based on a misconception of the

underlying legal standard, an appellate court is not bound by the

erroneous standard of review." Pavlides v. Galveston Yacht Basin.

Inc. 727 F.2d 330, 339, n. 16 (5th Cir. 1984); Noritake Co., Inc, v.

M/V Hellenic Champion. 627 F.2d 724, 727-28 (5th Cir. 1980).

2. APPLICATION OF THIS STANDARD OF REVIEW

In a series of decisions, United States v. Marengo County

Commission. 731 F.2d 1546, 1565, 1567, n. 34 (11th Cir. 1984) appeal

dismissed and cert. denied, __U.S.__, 83 L.Ed 2d 311 (1984); United

16-

States v. Dallas County Comm'n, 739 F.2d 1529, 1534-35 (11th Cir.

1984); McMillan v. Escambia County, 748 F.2d 1037, 1042-43 (5th Cir.

1984), consistent with the legislative history of the amended

Section 2, this Court has delineated nine factors that it

characterizes as "typical factors" which are to be weighed under a

totality of circumstances approach in assessing whether Section 2

has been violated. United States v. Marengo County, supra, 731 F.2d

at 1565; United States v. Dallas County Comm'n, supra, 739 F.2d at

1534; McMillan v. Escambia County, supra, 748 F.2d at 1042-1043.

The drafters of the amended Section 2 were direct in defining

the legal standard to be applied by spelling out "specifically in

the statute the standard that the proposed amendment is intended to

codify." Senate Report No. 417, 97th Cong., 2d Sess. (1982) at Pg.

27, reprinted in 1982 U.S. Code Cong, and Admin. News 177-410

(herein "Sen.Rep., Pg.__"). The legislative history explicitly

provides that under the "results test," Congress was codifying an

"extensive, reliable and reassuring track record of Court

decisions," Sen. Rep., Pg. 32, and that a "Court would assess the

impact of the challenged structure or practice on the basis of

objective factors (emphasis added) derived from the analytical

framework used by the Supreme Court in White v. Register, as

articulated in Zimmer," Sen. Rep., Pgs.27-28, n. 113.

Consequently, when a federal judge is called upon to determine

the validity of a practice challenged under Section 2, as amended,

the trial court should be held accountable to apply the "typical

factors" consistent with the intention of the 97th Congress in

amending Section 2 and with the interpretations already given to

-17-

those factors by this Court in United States v. Marengo, supra,

United States v. Dallas County, supra, and United States v. Escambia

County, supra.

In this case, as evidenced by significant factual stipulations

between parties, the essential facts to be applied to each of these

13"typical factors" are not in dispute. /

Since these underlying facts are not in dispute, the basis of

this appeal is not whether the District Court's factual findings are

"clearly erroneous," but instead whether the District Court's

conclusion pertaining to each of the nine "typical factors" derived

from these undisputed facts is consistent with this Court's

application of the amended Section 2.

13/ Specifically, the parties stipulated to a) voter registration

and election data for City Commission elections with black

candidates (P. Ex. 1, 8, 12); b) a compilation of various City

charter changes from 1911 through 1973, reflecting changes germane

to the electoral system (P. Ex. 2), (Tr.Vol. 7, Pg. 12); c) a series

of summaries of City Commission minutes from 1913 through 1979 (P.

Ex. 3), (Tr.Vol. 7, Pg. 12); d) a designation of City advisory

boards and committees, the purpose of the board or committee and

racial identity of its membership (P. Ex. 4 and 11), (Tr.Vol. 7,

Pgs. 12-13, le); e) summaries of City resolutions and ordinances (P.

Ex. 67), (Tr. Vol. 7, Pg. 13); f) racial composition of public

housing projects in Ft. Lauderdale (P. Ex. 7) (T. Vol. 7, p. 13); g)

results of elections with black candidates between 1957 and 1982 (P.

Ex. 8) (Tr.Vol. 7, Pg. 14); and h) street address of personal residencies of the City Commissioners from 1937 to present (P. Ex.

9), (Tr.Vol. 7, Pgs. 14-15).

Additionally, facts reflecting the comparative socio-economic

status between blacks and whites in Ft. Lauderdale (P. Ex. 15), and

documentary evidence in the form of a map showing the residences of

past and present City commissioners and black residential patterns

were not disputed (P. Ex. 29).

-18-

II. FT. LAUDERDALE'S AT-LARGE ELECTION

SYSTEM VIOLATES SECTION 2 OF THE

VOTING RIGHTS ACT BECAUSE IT RESULTS

IN DISCRIMINATION AND DENIES BLACK

CITIZENS AN EQUAL OPPORTUNITY TO

ELECT CANDIDATES OF THEIR CHOICE

In 1982, Congress extended the Voting Rights Act and amended

Section 2 to strengthen the ability of minority voters to challenge

discriminatory election practices. The amendment to Section 2 was

designed in part to eliminate the requirement, prescribed in City of

Mobile v. Bolden, 446 U.S. 55 (1980), that a Plaintiff demonstrate

purposeful discrimination in order to find that a voting practice is

unlawful. A violation of this new Section 2 "results" test is shown

if "based on the totality of the circumstances" minority voters

prove that they "have less opportunity than other members of the

electorate to participate in the political process and to elect

representatives of their choice." 42 U.S.C. § 1973(b) (West Supp.

1983).

This Court has enumerated the "typical factors," as articulated

by Congress in its passage of the 1982 Amendment, which courts

should consider under the "totality of circumstances" approach in

deciding whether plaintiffs have established a violation of Section

2. United States v. Marengo County Comm'n, supra, 731 F.2d at 1565,

United States v. Dallas County, supra, 739 F.2d at 1534-1535.

Our discussion of the legal standards embodied in these factors

as applied to the record evidence of this case follows.

-19-

1. HISTORY OF OFFICIAL DISCRIMINATION

AND ITS LINGERING EFFECTS

A. THE HISTORY

The District Court, while recognizing that "there was evidence

of discrimination against blacks in the City of Ft. Lauderdale in

the past," these findings are outlined in Appendix 1 of this Brief,

found that "almost none" of this history consisted of the "usual

badges of bias against minorities participating in the political

process" (RE, Op., Pg. 36). The District Court concluded that past

racial discrimination has not adversely affected the right of blacks

"either to register or to vote or otherwise participate in the

democratic process" (Ibid., 38-39); determining that this was

"particularly true" since black voter turnout has equaled or

exceeded white turnout since 1979 (Ibid., 39).

Judge Roettger's conclusion that past discrimination has no

effect on the present day ability of blacks to participate in the

political process is based on an improper application of the

governing legal standards to undisputed historical and contemporary

facts.

Despite the undisputed historical evidence, outlined in Appendix

1, the District Court erred by concluding (a) that none of the

historical evidence evinces the "[U]sual badges of bias against

minorities in the political process" (RE, Op., Pg. 36) and (b) that

the fact that black voter turnout since 1970 equals or exceeds white

voter turnout (RE, Op., Pg. 39), precludes a finding that historical

discrimination adversely affects blacks in Ft. Lauderdale from

participating in the political process.

-20-

These conclusions are legally erroneous for two reasons. First,

under Section 2, "discrimination against minorities outside of the

electoral system" cannot be ignored in assessing the challenged

election system, McMillan v. Escambia County, Fla., supra, 748 F.2d

at 1044; United States v. Marengo County, supra, 731 F.2d at 1567,

1574 (Consideration of "a history of pervasive racial discrimination

that has left blacks economically, educationally, socially and

politically disadvantaged."); United States v. Dallas County, supra,

739 F.2d at 1537 (same); Rodgers v. Lodge, supra, 458 U.S. at

624-625 (Historical evidence including discrimination in schools,

County employment, and in board and committee appointments all

considered in assessing "present opportunity of blacks to

effectively participate in the political process."). The Trial

Court's view of Ft. Lauderdale's past racial history, limited to the

"usual badges of bias against minorities participating in the

political process" (RE,Op., Pg. 36) is legally incorrect.

Secondly, the inquiry mandated by Section 2 as to whether past

discrimination affects present black political participation is not,

as the Trial Court concluded, (RE, Op., Pgs. 38-39), limited to a

comparison of the rates of voter turnout between black and white

voters. Rodgers v. Lodge, supra, 458 U.S. at 625 (Reduced political

participation evidenced by discrimination in hiring of county

employees and applicants to boards and committees); McMillan v.

Escambia County, Fla., 748 F.2d at 1045 (No significant difference

currently existing between black and white registered voters,

however, "other barriers... effectively operate to preclude access

for blacks."); Jones v. City of Lubbock, 727 F.2d 364, 385 (5th Cir.

-21-

1984) (Notwithstanding voter registration drives which have to an

extent ameliorated historical discrimination, the "present system

nevertheless preserves a lack of access.").

B. PRESENT EFFECTS OF THIS

PAST HISTORY

Significantly, by limiting its analysis to comparing voter

turnout rates between black and white voters, the District Court

disregarded important undisputed evidence that this past history of

discrimination has had and continues today to have a significant

impact on black citizens' participation in the political process.

(1) Residential Segregation

Although residential segregation laws were repealed in 1948,

their impact on residential patterns has endured. See, supra, Pg.

14/ See, also, T. Vol. 9, Pg. 464); (Vol. 10, Pgs. 127-28) (P. Ex.

29); (Almost 9 out of 10 [87.2%] of all black residents in the City

reside literally within, adjoining, or adjacent to the boundaries of

what was labeled and defined by 1941 City Ordinance as the "Negro

District.") The segregative impact of these apartheid like

ordinances is a present lingering effect of past racial

discrimination which impedes blacks' access to the political

process. See, e.g. , Wise v. Lipscomb. 399 F.Supp. 782, 790 (N.D.

Tex. 1975) affd, 551 F.2d 1043 (5th Cir. 1977) rev'd on other

grounds, 437 U.S. 535 (1978); Dowdell v. City of Apopka. 698 F.2d

1181, 1186 (11th Cir. 1983) (1937 unenforced city ordinance

prohibiting blacks from living on south side of tracks contributed

to ghetto-like qualities of black residential area); Escambia,

supra, 748 F.2d at 1044 (Continued separation of blacks from

dominant white society reduced black participation in government);

Civil Voters Organ, v. City of Terrell. 565 F.Supp. 338, 342 (N.D.

Tex. 1983) (Lingering racially segregative housing patterns impede

black political participation.)

-22-

(2) Imbalance of Blacks on City Boards and r.nmmi ttsas

Presently, as well as in the past, blacks have been denied

appointment to the City's various citizen advisory boards and

committees. (P. Ex. 4 and 11). Participation on these committees

is the most rudimentary and basic initial step into the City's

political process. See, e.g., Tr.Vol. 11, Pg. 274 (Mayor Dressler's

acknowledgement that Boards and Committees constitute "a very

important function" in the City's political process); (Tr. Vol. 10,

Pg. 202).15/

The Supreme Court has recognized the interrelationship between

blacks' appointment to boards and committees and access to the

political process. See, Rodgers v. Lodge, supra, 456 U.S. at 625

(Denial of "appointments to boards and committees which oversee the

[city] government can restrict the present opportunity of blacks to

participate in the political process); McMillan v. Escambia County

(II). 688 F.2d 960, 968 n. 16 (11th Cir. 1982) (Severe

underrepresentation of blacks on boards and committees reflects

exclusion from governmental policy-making machinery).

15/ From May, 1957 through June, 1983, there have been 66 different

City citizen advisory boards or committees in existence (P. Ex. 4)

On 40 of these boards and committees, no black had ever been appointed

during this 16-year period. On 13 of these committees there had been

only one black appointed during this period. As of October, 1984,

there were 24 City advisory boards and committees (P. Ex. 11, Facts

1-24). There were no black members on 13 of these boards. There were

237 members on these 24 boards and committees, (P. Ex. 11), of which

18, or 7.6% were black (P. Ex. 11). Additionally, of the 18 black

members, 5 serve on the Community Services Board, which by ordinance

requires appointment of members from the northwest quadrant and

blighted areas of the City (P. Ex. 11, Fact 12). Accordingly, of the

remaining 23 boards and committees, blacks comprise 13 of the total 221 members, or 5.9% (P. Ex. 11).

-23-

(3) Employment

Additionally, Judge Roettger disregarded undisputed evidence

showing past discrimination shaping present City employment

practices which act to restrict the present opportunity of blacks to

participate in the political process. Rodgers v. Lodge, supra. 458

U.S. at 625. While recognizing that blacks had petitioned the City

to employ black police officers (RE, Op., Pg. 38 n.3), the Court

disregarded that, on June 16, 1980, forty years after blacks began

petitioning the City to employ black police officers, the City was

placed under a court order through litigation initiated by the

Federal Government to increase the employment opportunities for

blacks in the City's police and fire departments. United States v.

City of Fort Lauderdale, No. 80-6289-CIV-ALH (S.D. Fla. 1980) (P. Ex.

23). Notwithstanding the 1980 Court Order, as of June 1983, of the

City's 353 black workers, 210 or 49.2% are classified as Service

Maintenance employees (P. Ex. 20, Table 13). Similarly, 193 black

workers, or 54.6% of the City's 353 employees are concentrated in two

of the City's ten designated departments - Sanitation and Sewage and

Parks and Recreation (P. Ex. 20, Table 12).

(4) Public Housing

Ft. Lauderdale operates public housing facilities through its

Housing Authority. (Tr.Vol. II, Pgs. 264-66). Six of the nine Public

Housing projects located in the City are segregated. (P. Ex. 7).

(5) Education

Today black children attend schools located in or serving Ft.

Lauderdale, which are more racially isolated and segregated than in

1971, the year that this Court's initial desegregation plan for Ft.

-24-

Lauderdale students was implemented in Allen v. Board of Public

Instruction of Broward, 432 F.2d 302 (5th Cir. 1970) cert, denied

402 U.S. 952 (1971 )16/

16/ Evidence of isolation and segregation was presented by Dr.

Gordon Foster, one of the nation's leading desegregation experts,

(Vol. 9, Pgs. 478-491), (P. Ex. 16), who has served as a consultant

to the Broward County School Board since 1967, stemming from the

Board's initial desegregation efforts. (Tr.Vol. 9, Pgs. 491-493). Ft. Lauderdale is located in Broward County.

Drawing upon that experience, as well as his desegregation background with virtually every school board in the State of

Florida, (Ibid., Pg. 481), Dr. Foster conducted a study and

concluded that in the schools located in or serving Fort Lauderdale:

(1) (A) The number of black students attending racially identifiable

or segregated schools has almost doubled since 1971. Four out of

five (80%) black students today attend racially identifiable

schools. In 1971, when integration was ordered, 48% of the black

students attended identifiable schools. (P.Ex. 24, Table 5A), (Tr.

Vol. 10, Pgs. 5-7), (P. Ex. 24, Table 5A); (B) the number of black

students attending racially isolated schools has tripled since 1971,

(Ibid.); (C) and reciprocally, the number of black students

attending integrated schools has decreased from 52% in 1971 to 20%;

(2) The same schools that were segregated through de iure

restriction in 1968, (Tr. Vol. 10, Pg. 11) are likely to be ''still

predominantly black." (Ibid, Pg. 13), (P. Ex. 24, Table 6); (3)

Schools in Fort Lauderdale today have increasingly higher

enrollments of black students than in 1968, in comparison to the

entire County. (Tr. Vol. 10, Pgs. 15-17), (P. Ex. 24, Table 7); (4)

Black students in more racially isolated schools have generally

performed poorer on standardized achievements tests, (Tr. Vol. 10, Pg. 24), (P. Ex. 24, Table 8).

Based upon these findings, Dr. Foster concluded that blacks are

"still less fitted than their white counterparts" in Fort Lauderdale

to "participate in the voting process." (Tr. Vol. 10, Pg. 48).

In the face of this authoritative evidence, the Trial Court

noted that: (1) the "City of Fort Lauderdale has no control or voice

in the operation of the schools." (RE, Op., Pg. 51 n. 10), a fact

which has no legal relevance at all, see, e.g.. United States v.

Marengo County, supra, 732 F.2d at 1567 n. 36 (Even history of

private discrimination is relevant to issue of minority access to

political process); and (2) a high school located outside of the

City was not included in Dr. Foster's analysis (RE, Op., Pg. 51 n.

10) notwithstanding the fact that Dr. Foster's data utilized in his

study, and corroborated by his 18 year association with the School

Board, was authenticated since it was derived directly from the

School Board itself (Tr.Vol. 9, Pg. 509; Tr.Vol. 10, Pgs. 8-10).

-25-

The Trial Court determined that the effects of "discrimination -

or lingering affects - in the field of education" (RE, Op., Pg. 51)

could not adversely affect political participation due to the level

of "turnout of black voters." (Ibid.) This conclusion is legally

baseless, and constitutes error. United States v. Marengo County,

supra, 732 F.2d 1567-69 (History and lingering affect of segregated

education impeding black access to the political process); Id., at

Pg. 1568 ("[B]ecause blacks are poorer and less educated they have

less political influence than whites."); United States v. Dallas

County Comm'n, supra, 739 F.2d at 1537; McMillan v. Escambia County,

Fla., supra, 748 F.2d at 1044.

In summary, the (1) sustained pattern of rigid residential

racial segregation; (2) present underrepresentation of blacks on

City advisory boards and committees; (3) present discriminatory City

employment practices; (4) segregation in public housing; (5)

educational isolation and segregation of black students; (6)

depressed socio-economic status, see, infra, Pgs. 60-62, and (7)

17/persistent voting along racial lines, infra, Pgs. 28-35, all

reflect the present isolation of blacks and the imbalance in City

practices which directly impair blacks' ability to participate on an

equal footing in the political process.

17/ Only one black has ever been elected to the Ft. Lauderdale City

Commission in the 74 years of its existence, notwithstanding

numerous black candidates, and the fact that Ft. Lauderdale is over

twenty percent black. Moreover, a continuing high degree of

racially polarized voting is itself a vestige of past racial

segregation. Jones v. Lubbock, supra, 727 F.2d at 383 (The

persistence of polarization moreover signals that race and ethnicity

still significantly influence the electorate's preferences); Kirksey

(Footnote continued to next page)

-26-

2. RACIALLY POLARIZED VOTING

This Court as well as previously the Fifth Circuit over the past

decade has identified a variety of methods to measure racially

polarized voting, all of which correlate the race of a voter with

- I Q /the race of the candidate. When the degree of the correlation

is clear and consistent, then a finding of polarization has been

made.

As reviewed in detail, infra. Pgs. 28-35, Plaintiffs have met

each and every of these polarization standards in our analysis of

the black candidacies in Ft. Lauderdale. Notwithstanding, the Trial

Court in disregard of the standards articulated by this Court to

gauge racial polarization, either rejected our analysis or failed

even to consider this Court's precedent insofar as assessing

polarization. As such, the District Court's conclusion that

(Footnote continued from previous page)

v. Board of Supervisors of Hinds County. 554 F.2d 139, 146 (5th Cir.

1977) (en banc) cert, denied. 434 U.S. 968 (1977) (Absence of black

elected officials is indication that blacks' access to the political process is not yet unimpeded.").

18/ See, e.g., McMillan v. Escambia County. Fla., supra. 638 F.2d at

1241 n. 6; 688 F.2d at 966 n. 12 (Bivariate regression correlations of

.85-.98 as proof of polarization.) vacated and remanded. ___U.S.___,

80 L.Ed.2d 36 (1984) aff'd. supra. 748 F.2d at 1043 n. 12; NAACP v.

Gadsden County School Board. 691 F.2d 978, 983 (11th Cir. 1982) (Same

bi-variate analysis); Bolden v. City of Mobile. 423 F.Supp. 384,

388-89 (S.D. Ala. 1976) (Same bi-variate analysis) aff'd 571 F.2d 238

(5th Cir. 1978) rev'd on other grounds 446 U.S. 55 (1980); Nevitt v.

Sides, 571 F.2d 209, 223 n. 18 (5th Cir. 1978) cert, denied 446 U.S.

951 (1980); United States v. Dallas County Comm'n. supra. 739 F.2d at

1535 n. 4 (Racial polarization index of values ranged from 37 to 75;

index of 40 or higher is significant); Jones v. City of Lubbock.

supra, 727 F.2d at 380 (Racial bloc voting exists where polarization

index is 52); McMillan v. Escambia County. Fla., supra. 638 F.2d at

1241 n. 6, 748 F.2d at 1043 (Significant majority [60%] of whites don't vote for black candidate.).

-27-

"[t]here has been no racial polarization showing a violation of the

Voting Rights Act/' (RE, Op., Pg. 47), is infected by erroneous legal

standards and is contrary to the undisputed factual evidence, which in

19 /some instances was never even considered by the Court.

In discussion of the racial bloc voting issue, we review in the

following order: (1) Plaintiffs' evidence of polarization; (2) the

Trial Court's erroneous rejection of that evidence; and (3) the

multi-variate regression, which was erroneously relied upon by the

Trial Court in its conclusion that ''no racial polarization,*' Ibid.,

exists in Ft. Lauderdale elections.

A. PLAINTIFFS' PROOF OF

RACIAL POLARIZATION

(1) THIS COURT'S STATISTICAL METHODS

USED FOR GAUGING RACIAL POLARIZATION

(a) BIVARIATE REGRESSION ANALYSIS

Standard analytic procedures--specifically, correlation and

regression analyses--have been used for more than a decade to assess

the degree to which voting in elections is racially differentiated,

and the estimated differences in voter preferences derived from these

_____________________________/

19/ In bears mention that other than Judge Higginbotham’s concurring

decision for denying a rehearing en banc in Jones v. City of

Lubbock, 730 F.2d 233-36 (5th Cir. 1984), the concepts of which are

discussed at greater length in, infra, Pgs. 40-45, Judge Roettger

relied on no legal authority for his polarization analysis other

than his passing mention to the following three employment

discrimination decisions having absolutely nothing to do with racial

polarization standards: Teamsters v. U.S., 431 U.S. 734 (1977);

Wilkins v. Univ. of Houston, 654 F.2d 388 (5th Cir. 1981), reh' g

denied 662 F.2d 1156 (5th Cir. 1981); and Boylan v. The New York

Times (unreported settled case). See, RE, Op., Pg. 47.

-28-

procedures have rarely been a major source of disagreement in

litigation.

Racially polarized voting is most frequently measured by

correlating the percentage of registered minority voters in a

precinct with the percentage of the vote minority candidates

received in that precinct. This analysis measures the relationship,

and the strength and consistency of the relationship, between the

two variables. This correlation, which is the precise technique

utilized in Plaintiffs' bi-variate regression analysis resulting in

correlations between .81-.99 in 16 elections with 13 elections

producing associations greater than .91 (P.Ex. 25, Table 2, Column

1), see also, (Tr.Vol. 11, Pgs. 251-261), which is lodged in

Appendix 2 for the Court's convenience, is the accepted statistical

standard for gauging racial polarization in our Circuit. McMillan

v. Escambia County, Fla., 638 F.2d 1239, 1291 n. 6 (5th Cir.

20 /February 19, 1981) (Racial bloc voting found, based "on very

high correlations" between the percentage of blacks in a precinct

and number of votes a black candidate received in that precinct),

aff'd on rehearing, 688 F.2d 960, 966 n. 12 (5th Cir. 1982)

(Correlations between .85-.98 as proof of polarization) vacated and

remanded in light of amended Section 2, ___U.S.___, 80 L.Ed. 2d 36

(1989), aff'd 798 F.2d 1037, 1093 (Confirming the use of bivariate

regression analysis to prove racially polarized voting.); NAACP v.

Gadsden County School Board, 691 F.2d 978, 983 (11th Cir. 1982)

20/ Pre-October 1, 1981 decisions of the old Fifth Circuit are binding on the Eleventh Circuit. Bonner v. City of Prichard, 661

F.2d 1206, 1209 (11th Cir. 1981) (en banc).

-29-

(Same bivariate analysis) and Lee County Branch. NAACP v. City of

Opelika, 748 F.2d 1473, 1481 (11th Cir. 1984).217

* * * *

In order to corroborate and further explore the Ft. Lauderdale

electorate's strong and persistent pattern in city commission

elections of voting along racial lines, Plaintiffs submitted the

following additional analysis commonly utilized by the courts in

assessing racial bloc voting.

(b) RACIAL POLARIZATION INDEX

The "racial polarization index" is calculated by determining the

percentage of votes cast in the black precincts for a particular

candidate, and then subtracting the votes cast for the same

individual in the white precincts. This Circuit, just last year in

reversing a trial court, found polarization under this index

technique in elections where index values ranged from 37 to 75, and

held that an index of 40 or higher was significant. United States

v. Dallas County, supra, 739 F.2d at 1535 n. 4. See also. Jones v.

City of Lubbock, supra, at 380 (5th Cir. 1984) (Finding of

polarization with index of 52 where minorities received 11% of the

white vote compared to 63% in minority areas.). In Fort Lauderdale,

21/ Other courts have adhered to this same bivariate correlation

standard in their determinations that polarization existed. See,

g-g-» Jones v. City of Lubbock, 727 F.2d 364, 380-81 (5th Cir7T984)

(Bivariate regression analysis utilized to prove racially polarized

voting.); City of Rome v. United States. 472 F.Supp. 221, 226 n. 36

(D.D.C. 1979) (Three Judge panel) ( Correlation method surest way of

demonstrating racial bloc voting) aff'd 446 U.S. 156 (1980); Major

— Treen, 574 F.Supp. 325, 338 (E.D. La. 1983) (Three Judge Court) (Range from .51 to .95 in proving polarization); Ginales v.

Edminsten, 590 F.Supp. 345, 367-68 n. 29 (E.D. N.C. 1984) (Three

Judge panel) (Range between .7 - .98 with most above .90).

30-

the polarization index average for all elections in which black

candidates ran since 1971 is 54 (P. Ex. 38).22/?

(c) SUPPORT FOR WINNING CANDIDATES

In further analyzing the differing black and white voters

electoral behavior in order to determine polarization, Plaintiffs

presented unrebutted evidence measuring the two racial communities'

ultimate support for the 5 winning candidates in each general

election (4 winning candidates in 1979).

Voter support for the ultimate winning candidates was analyzed

in all general elections between 1971 through 1982 in racially

homogenous precincts. In virtually every case, in each white

precinct white voters cast their votes for one of the 5 winning

candidates more than 50% of the time and in many instances as much

as 60% to 70% of the time. Among black voters, the percentage of

support of their votes for winning candidates was in the range of

10%-12% with the exception of the DeGraffenreidt elections. (Tr.

Vol. 8, Pgs. 207-208), (P. Ex. 25, Table 4). The pattern that

emerged over this 11 year period, structured in graphic format in

Plaintiffs' Exhibit 36, and recognized by Defendants' own expert

(Tr. Vol. 12, Pgs. 505, 508), is that whites cast a disproportionate

share of their votes for winners as compared to their black

counterparts. (Tr. Vol. 8, Pgs. 208-209). * 11

22/ In all elections analyzed between 1971-1982, on the average, 86%

of black voters cast at least one vote for a black candidate while only 32% of all white voters cast a vote for a black candidate, thus

yielding a polarization index of 53 (P. Ex. 38). See also. (Tr.Vol.

11, Pgs. 359-360) (Defendants' expert confirmed this conclusion [31.85%]).

-31-

(d) BLACKS' IMPACT ON THE

OUTCOME OF ELECTIONS

A further study conducted by Plaintiffs analyzed the election

results to determine whether the polarization of voting was

substantively significant. This inquiry simply addressed whether