Larkin v. Pullman Standard Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants

Public Court Documents

July 13, 1987

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Larkin v. Pullman Standard Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants, 1987. 38404ba4-ba9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c37e6fe3-132f-4783-ab1c-32fbd2346e7d/larkin-v-pullman-standard-brief-for-plaintiffs-appellants. Accessed February 17, 2026.

Copied!

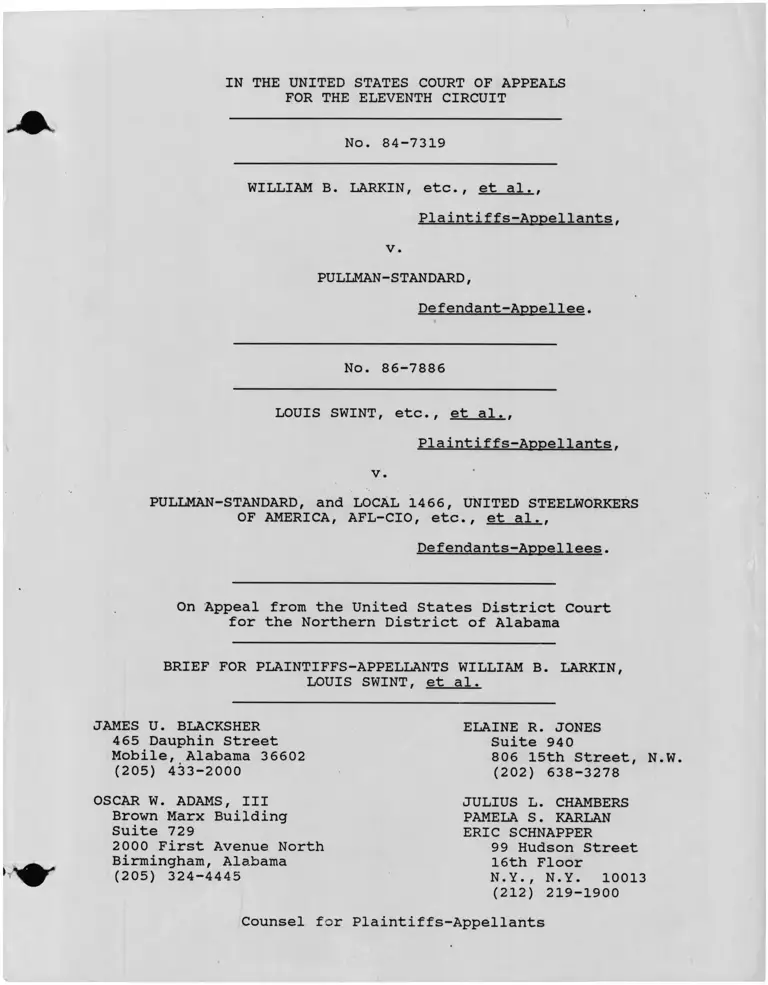

IN THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE ELEVENTH CIRCUIT

No. 84-7319

WILLIAM B. LARKIN, etc., et al..

Plaintiffs-Appellants.

PULLMAN-STANDARD,

Defendant-Appellee.

No. 86-7886

LOUIS SWINT, etc., et al..

Plaintiffs-Appellants.

PULLMAN-STANDARD, and LOCAL 1466, UNITED STEELWORKERS

OF AMERICA, AFL-CIO, etc., et al..

Defendants-Appellees.

On Appeal from the United States District Court

for the Northern District of Alabama

BRIEF FOR PLAINTIFFS-APPELLANTS WILLIAM B. LARKIN,

LOUIS SWINT, et al.

v

v

JAMES U. BLACKSHER

465 Dauphin Street

Mobile, Alabama 36602

(205) 433-2000

ELAINE R. JONES

Suite 940

806 15th Street, N.W

(202) 638-3278

OSCAR W. ADAMS, III

Brown Marx Building

Suite 729

2000 First Avenue North

Birmingham, Alabama

(205) 324-4445

JULIUS L. CHAMBERS

PAMELA S. KARLAN

ERIC SCHNAPPER

99 Hudson Street

16th Floor

N.Y., N.Y. 10013

(212) 219-1900

Counsel for Plaintiffs-Appellants

CERTIFICATE OF INTERESTED PERSONS

The undersigned, counsel of record for plaintiffs-appellants

William B. Larkin, Louis Swint, et al., certifies that the

following listed parties have an interest in the outcome of this

case. These representations are made in order that Judges of

this Court may evaluate possible disqualifications or recusal

pursuant to Local Rule 13(a):

Judge: Hon. Sam C. Pointer, Jr., United States

District Judge for the Northern District

of Alabama.

Hon. Foy Guin, United States District

Judge for the Northern District of

Alabama.

Plaintiffs: Louis Swint

Willie James Johnson

William B. Larkin

Spurgeon Seals

Jesse B. Terry

Edward Lofton

The class of all black persons employed

at Bessemer plant of Pullman-Standard

between 1965 and 1974.

Defendants: Pullman-Standard, Inc.

The Pullman Company

United Steelworkers of America, AFL-CIO

Local 1466, United Steelworkers of

America, AFL-CIO

The International Association of

Machinists

Local 372, International Association of

Machinists

Counsel for Plain

tiffs: Oscar W. Adams, III

James U. Blacksher

Julius LeVonne Chambers

Elaine R. Jones

Pamela S. Karlan

Eric Schnapper

The NAACP Legal Defense and

Educational Fund, Inc.

Blacksher, Menefee & Stein, PA.

Former Counsel for

Plaintiffs: Hon. U.W. demon

United States District Judge for the

Northern District of Alabama

Counsel for

Defendants: C.V. Stelzenmuller

Burr & Forman

n

William J. Marshall, Jr.

F.B. Snyder

Jerome A. Cooper

John Falkenberry

Elaine R. Jones

Counsel for Plaintiffs-Appellants

in

STATEMENT REGARDING PREFERENCE

This case is not entitled to preference under Eleventh

Circuit Rule 11.

iv

STATEMENT REGARDING ORAL ARGUMENT

These Title VII cases present a large number of procedural

and substantive issues. This court held oral argument regarding

both of the previous appeals. Svint v. Pullman-Standard. 624

F. 2d 525 (5th Cir. 1980); 539 F.2d 77 (5th Cir. 1976). The

defendant-appellant has requested oral argument in the companion

case No. 87-7057. We believe that oral argument would be

appropriate in this appeal as well.

v

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Certificate of Interested Persons ................ i

Statement Regarding Preference ................... iv

Statement Regarding Oral Argument ................ v

Table of Authorities .............................. viii

Statement of the Issues ........................... 1

Statement of the Case ............................. 1

(i) Course of the Proceedings .............. 1

(a) Swint .............................. 1

(b) Larkin ............................. 6

(ii) Statement of the Facts .................. 10

(iii) Standard of Review ..................... 18

Summary of Argument ............................... 18

Statement of Jurisdiction ......................... 21

Argument .......................................... 22

I. The Court Below Erred in Refusing

to Provide a Remedy for Discrimina

tion Occurring Prior to July 17, 1969 ....... 22

(1) The Pre-1980 Decisions in Swint

Regarding the Relevant Limita

tions Period ............................ 24

(2) The 1969 Limitation Date in Swint Is

Inconsistent with the Decision in

Larkin .................................. 28

(3) The Title VII Cut-off Date in

Swint Is No Later Than September

28, 1966 ................................ 29

(a) The Limitations Period May

Be Based on the March 27,

1967, Commissioner's Charge ........ 29

Page

vi

(b) The Limitations Period May Be

Based on Title VII Charges

Filed in 1966 and 1967 By Class

Members Who Are Not Named

Plaintiffs ......................... 32

(c) The District Court Improperly

Denied the Motion of Larkin,

et al. to Intervene in Svint ...... 34

(d) The Defendants Have Waived Any

Limitations Defense to Claims

Arising in or After 1966............ 37

(4) The Section 1981 Cut-Off Date in

Swint is October 19, 1965 ............... 39

II. The District Court in Swint Erred in

Holding that Assignment Discrimination

Ended in February, 1969 ..................... 42

III. The Court Below Erred in Refusing

to Provide a Remedy for Discrimina

tion in the Assignment of ExistingEmployees .................................... 49

IV. The Pullman-Standard Seniority System

was Not Bona Fide .............. 55

(1) Discrimination in the Genesis of

the System .............................. 56

(a) The Motives of the IAM ............ 56

(b) The Creation of Single-Race

Steelworker Departments ........... 63

(2) Discrimination in the Maintenance

of the System ........................... 65

(3) The Lock-In Effect of the System....... 72

Conclusion ........................................ 74

Certificate of Service

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Bartholomew v. Fischl, 782 F.2d 1148

(3d Cir. 1986) 40

Boudreaux v. Baton Rouge Marine Contr. Co.,

437 F. 2d 1011 (5th Cir. 1971) ............... 41,42

Buckner v. Goodyear Tire and Rubber Co.,

330 F. Supp.. 1108 (N.D. Ala. 1972) 41

Buckner v. Goodyear Tire and Rubber Co.,

476 F. 2d 1287 (5th Cir. 1973) ............... 41

Chris-Craft Industries v. Piper Aircraft Corp.,

516 F. 2d 172 (2d Cir. 1975) ................. 74

EEOC v. Shell Oil Co., 466 U.S. 54 (1984) ........ 31

Gaines v. Dougherty County Bd. of Ed.,

775 F. 2d 1565 (11th Cir. 1985) .............. 42

Goodman v. Lukens Steel Co., 55 U.S.L.W. 4881

(1987) 19,39,40

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1970) .... 31

Inda v. United Airlines, 565 F.2d 554

(9th Cir. 1977) .............................. . 19,30

Ingram v. Steven Robert Corp., 547 F.2d 1260(5th Cir. 1977) 41

Johnson v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co.,

491 F. 2d 1364 (5th Cir. 1974) ............... 33

Johnson v. Railway Express Agency,

421 U.S. 454 (1975) 42

Jones v. Preuitt & Maudlin, 763 F.2d 1250

(5th Cir. 1985) 19,23,39,40

Jones v. Shankland, 800 F.2d 77

(6th Cir. 1986) 40

Joshi v. Florida Sate University Health Center

763 F. 2d 1227 (11th Cir. 1985) .............. 43

Cases: Page

viii

Marks v. Parra, 785 F.2d 1419 (9th Cir. 1986) .... 40

Mohasco Corp. v. Silver, 447 U.S. 807 (1980) ..... 37

Payne v. Travenol Laboratories, 673 F.2d 798

(5th Cir. 1982) 32,33

Pettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe Co.,

494 F. 2d 211 (5th Cir. 1974) ................ 33

Pullman-Standard v. Swint, 456 U.S. 273 (1982) ___ 5

Rivera v. Green, 775 F.2d 1381 (9th Cir. 1985) .... 40

Swint v. Pullman-Standard, 11 FEP Cas. 943

(N.D. Ala. 1974) 2,11,12,17,25,

43,46,54,59,65

Swint v. Pullman-Standard, 539 F.2d 77

(5th Cir. 1976) 3,18,25,42,43,

45,49,54,59,65,74

Swint v. Pullman-Standard, 15 FEP Cas. 144

(N.D. Ala. 1977) 3,12,26,29,43,

55,56,65

Swint v. Pullman-Standard, 15 FEP Cas. 1638

(N.D. Ala. 1977) 4,26,60

Swint v. Pullman-Standard, 17 FEP Cas. 730

(N.D. Ala. 1978) 4,64,73

Swint v. Pullman-Standard,624 F.2d 525

(5th Cir. 1980) 24,22,26,27,29,

43,56,57,61,64,65,73

Swint v. Pullman-Standard, 692 F.2d 1301

(11th Cir. 1983) 5

Teamsters v. United States, 431 U.S. 324

(1977) 4,60,63

United Airlines Inc. v. McDonald,

432 U.S. 389 (1977) 36

United States v. Georgia Power Co.,

474 F. 2d 925 (5th Cir. 1973) ................ 33

Wilson v. Garcia, 85 L.Ed.2d 254 (1985) 39,40

Cases; Page

IX

Zipes v. Trans World Airlines, 455 U.S. 385

(1982) 37

Other Authorities;

28 u.s.c. § 1291 .................................. 22

42 U.S.C. § 1981 .................................. 1,19,23,

38,39-42

42 U.S.C. § 1983 .................................. 39

42 U.S.C. § 1988 .................................. 39

Title VII, Civil Rights Act of 1964 .............. Passim

Section 706(e), Civil Rights Act of 1964 ......... 30

Rule 8 (c), Federal Rules of Civil Procedure ...... 37

Rule 23, Federal Rules of Civil Procedure ........ 53

Rule 52, Federal Rules of Civil Procedure ........ 5,55

Rule 54, Federal Rules of Civil Procedure ........ 21

29 C.F.R. § 1601.28(a) ........................... 31

29 C.F.R. § 1601.28 (b) (3) (ii) .................... 31

EEOC, Legislative History of Titles VII and XI

of Civil Rights Act of 1964 ................. 30,31

Alabama Code, Section 6-2-34(1) 39

Alabama Code, Section 6-2-39(a)(5) 40

Cases: Page

x

STATEMENT OF THE ISSUES

(1) Did the district court in Swint err in limiting the

class claims to claims arising after July 17, 1969?

(2) Did the district court in Swint err in holding that

assignment discrimination ended in February, 1969?

(3) Did the district court in Swint and Larkin err in

refusing to provide a remedy for discrimination in the assignment

of existing employees?

(4) Is the seniority system at Pullman-Standard's Bessemer

plant bona fide?

(5) Did the district court in Larkin err in denying the

plaintiffs' motion for relief from judgment in that case?

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

(i) Course of the Proceedings

(a) Swint

This case was commenced on October 19, 1971, by a black

employee and a black former employee at the Bessemer, Alabama,

plant of the Pullman-Standard Company. The original complaint

sought injunctive relief as well as back pay; because the plant

has now closed, only monetary relief, including backpay

adjustments in pension and benefit rights and counsel fees, is

now at issue. The complaint alleged that the defendants had

engaged in unlawful discrimination in violation of Title VII and

42 U.S.C. § 1981.

The principal EEOC charges filed regarding the Bessemer

plant were as follows:

EEOC Charges1

Date of Charge Charging Party

November 4, 1966 Spurgeon Seals

March 27, 1967 EEOC Commissioner

Schulman

April 11, 1967 Spurgeon Seals, Jesse B

Terry, Edward Lofton

October 13, 1967 William B. Larkin

October 15, 1969 Louis Swint

On June 4, 1974, the district court certified the case as a class

action on behalf of all blacks who were employed at the plant

during the period beginning one year before the filing of "any

charge" with the EEOC. (R.E., p. 60).

a variety of claims. On September 13, 1974, Judge Pointer found

that prior to 1965 it had been the practice of the defendants to

segregate jobs on the basis of race and to assign new and

existing employees based on whether a particular vacancy was for

a "white" or "black" job. This assignment discrimination, the

court concluded, lasted in some departments as late as 1971.

Swint v. Pullman-Standard. 11 FEP Cas. 943, 953-54 (N.D. Ala.

1974) . The district court concluded, however, that these facts

did not constitute discrimination in departmental assignments,

because, inter alia, blacks were assigned to "black" jobs in

"mixed" departments. Id. at 949-52. The district court also

rejected claims that the company engaged in racial discrimination

This case was first tried in July and August of 1974 on

1 624 F.2d at 528 n. 1; R.E., p. 109; PX 58, pp. 1, 4

2

in the selection of supervisors, and that the company had

dismissed the named plaintiffs in retaliation for having filed

EEOC charges. The district court ordered certain limited

monetary and injunctive for class members injured by the

identified post-Act assignment discrimination. Id. at 961.

Only the plaintiffs appealed from the 1974 district

court decision. The district court's 1974 opinion had been based

largely on a chart, constructed by Judge Pointer himself, which

purported to demonstrate that blacks were actually in "desirable"

departments; the Fifth Circuit dismissed that chart as tainted by

"patent inaccuracies" and not "statistically fair." Swint v.

Pullman-Standard. 539 F.2d 77, 92 (5th Cir. 1976). The court of

appeals overturned the district court's findings regarding

discrimination in assignments and discrimination in the selection

of supervisors, and remanded those issues for further

proceedings. The court of appeals upheld the district court's

rejection of the retaliation claims. 539 F.2d at 105.

On remand the district court held that the limitations

period commenced in December, 1966. Swint v. Pullman-Standard.

15 FEP Cas. 144, 146-47 n.3 (N.D. Ala. 1977). The district court

had found in its earlier opinion that assignment discrimination

continued after 1966 in 5 departments, and the company had not

appealed from the final judgment entered on that issue. In its

1977 opinion, however, the district court held its prior decision

was "incorrect," and that the assignment discrimination in those

departments had actually ended in 1965. 15 FEP Cas. at 149. The

3

district court also held that the company had not engaged in

discrimination in the selection of supervisors. Id. at 150-53.

The 1977 opinion, like the 1974 opinion, was expressly based on a

chart constructed by Judge Pointer himself, but in 1977 Judge

Pointer chose not to disclose the contents of his new chart, id.

at 148; when plaintiffs requested Judge Pointer to reveal the

chart to counsel so it could be reviewed on appeal, Judge Pointer

flatly refused. 15 FEP Cas. 1638, 1639. Later in 1977, in light

of the Supreme Court's decision in Teamsters v. United States.

431 U.S. 324 (1977), the district court ordered a retrial with

regard to the bona fides of the seniority system at the plant.

Swint v. Pullman-Standard. 15 FEP Cas. 1638 (N.D. Ala. 1977). On

May 5, 1978, the district court concluded that the seniority

system was bona fide. Swint v. Pullman-Standard. 17 FEP Cas. 730

(N.D. Ala. 1978).

On appeal, the Fifth Circuit again reversed, holding

that assignment discrimination continued after the effective date

of Title VII, that the company had engaged in discrimination in

the selection of supervisors, and that the disputed seniority

system was not bona fide. Swint v. Pullman-Standard. 624 F.2d

525 (5th Cir. 1980). The appellate court noted that, because of

the 1972 amendments to Title VII, the limitations period

commenced in September 1966, rather than December 1966. 624 F.2d

at 528-29 n. 1.

The company and union sought certiorari on a variety of

issues; the Supreme Court limited review to the question of

4

whether the Fifth Circuit, in holding the seniority system was

not bona fide, had exceeded its authority under Rule 52(a).

Pullman-Standard v. Swint. 456 U.S. 273 (1982). The Supreme

Court held that the bona fides of a seniority system, although

the ultimate issue under Teamsters. was nonetheless an issue of

fact to which Rule 52(a) applied. The company and union urged

the Court to affirm the district court finding that the seniority

system was bona fide; the Supreme Court, however, declined to do

so, choosing instead to vacate and remand the case for further

proceedings. 456 U.S. at 293. This court in turn remanded the

case to the district court with instructions to address several

specified issues, and to conduct such other proceedings as were

"necessary in view of our prior opinion and that of the Supreme

Court." 692 F.2d 1031 (5th Cir. 1983).

On remand the district court held an additional hearing

in April and May, 1984; after a delay of over two years, the

district court issued a new opinion on September 8, 1986.2

First, Judge Pointer held that the limitations period within

which relief could be provided would begin on July 17, 1969

(R.E., p. 109-111); the new date was some 2 years and 7 months

later than the limitations date set in Judge Pointer's own 1977

opinion, and 2 years and 10 months later than the limitations

date approved by the Fifth Circuit in its 1980 opinion. Second,

The district court's decisions regarding discrimination

in the selection of supervisors, and regarding the ability of the

named plaintiffs to represent the class are the subject of a separate appeal by the company. No. 87-7057.

5

Judge Pointer held that all assignment discrimination ended by

February 1969, two years and 4 months earlier than the date which

Judge Pointer had identified in 1974 as marking the end of such

discrimination. Id. at 118-121 The effect of these two changes

was that, rather than receiving over five years of back pay, the

plaintiff class was denied any relief for assignment

discrimination. Third, Judge Pointer again held that the

seniority system was bona fide. Id. at 115-117.

(b) Larkin

In 1966 and 1967 William Larkin, Spurgeon Seals, Edward

Lofton and Jesse B. Terry each filed charges with the EEOC

alleging that they had been the victims of racial discrimination

at the Bessemer plant. The charges claimed, inter alia, that the

complainants had been or were being denied assignments to more

desirable jobs because of their race. (R.E.,pp. 16-17) On May

21, 1971, the EEOC Birmingham Field Director, after investigating

these charges, reported that the company's records "indicate that

Caucasians have received more promotions and received promotions

within a shorter period of time." (Id. at 18) The EEOC

concluded in 1972 that the company's "hiring, job assignment and

permanent promotion policies have been in violation of the Act

and continue to be unlawful . . . ," noting that the hiring

discrimination was a result of continued "segregated job

classifications." (PX 58, p. 7). These practices, the

Commission found, "limit a disproportionate number of Negro

employees to the less desirable jobs in the plant." (Id. at 8).

6

On December 9, 197 5, Larkin, Seals, Lofton and Terry-

filed suit under Title VII on behalf of themselves and others

similarly situated. The complaint alleged, inter alia. that "the

Company discriminated against blacks by excluding them from its

more desirable jobs and departments." (R.E., p. 64) At the time

this complaint was filed, the first district court decision in

Swint was pending on appeal in the Fifth Circuit. On December

31, 1975, Pullman-Standard filed a motion to dismiss the Larkin

complaint on the following grounds:

"1. The complaint fails to state a claim upon which relief can be granted;

2. As shown by the records of this Honorable Court in

case number 74-3726, of which judicial notice may

be taken, the matters complained of are res judicata;

3. As shown by the records of this Honorable Court in

said case, plaintiffs are collaterally estopped to maintain this action;

4. Case number 74-3726 is now pending on an appeal to

the United States Court of Appeals for the Fifth

Circuit taken by Louis Swint, and if that appeal

was properly taken on behalf of the class of

plaintiffs in that case, which included plaintiffs

herein and the alleged class of plaintiffs, this

action should be abated because of the prior action pending."

(R.E., p. 67). On January 20, 1976, the district judge in

Larkin, Judge Guin, granted the motion on the following grounds:

The court has considered said motion is of

the opinion that same is due to be granted on

the basis of either paragraph two, three, or

four. It appears to this court that all

issues presented by the complaint are

presently on appeal to the Fifth Circuit

Court of Appeals in the case of Louis Swint,

Appeals Case No. 74-3726, and that the

plaintiffs herein are included in the

7

putative class of plaintiffs on whose behalf

said appeal was taken.

Accordingly, it is ORDERED ... that the

motion to dismiss be, and hereby is GRANTED,

and the above styled case be dismissed with

prejudice.

(R.E., p. 69). On February 9, 1976, the plaintiffs in Larkin

filed a notice of appeal. However, counsel for plaintiffs,

agreeing with the company and Judge Guin that the Larkin issues

were all within the scope of the Swint case, did not pursue the

Larkin appeal, which was subsequently dismissed.

In June 1983, following the remand of Swint from the Fifth

Circuit, Pullman-Standard urged Judge Pointer to change the

limitations cut-off date in Swint from 1966 to 1969; the company

based its proposal, in part, on its contention that only EEOC

charges filed by the named plaintiffs in Swint could determine

the limitations date in that case. Swint's original charge had

been filed in 1969, some three years after the charge by Larkin

plaintiff Spurgeon Seals. The company's request, if granted,

would have placed outside of the Swint litigation the original

individual charges of all of the four Larkin plaintiffs. In

response to the potential problems raised by the company's new

position, counsel for plaintiffs filed a motion seeking to add

Seals as a named plaintiff and class representative in Swint

(R.E., p. 110 and n. 4); the company asserted that Judge Guin's

1976 order had resolved on the merits the claims of the Larkin

*

plaintiffs, thus precluding them from participating in the Swint

case in any fashion whatever.3

Plaintiffs thereupon filed in Larkin a motion for relief

from judgment, seeking an order to make clear that the court in

Larkin "did not intend to bar Seals from pursuing his claims in

the context of the Swint litigation." Plaintiffs urged Judge

Guin to clarify the matter by deleting the words "with prejudice"

from his 1976 order. 4 The company urged in response that,

because the 1976 opinion contained the words "with prejudice,"

Judge Guin had indeed intended to make "an adjudication on the

merits" on the individual claims of Larkin, Seals, Terry and

Lofton.5 Counsel for the company attacked plaintiffs' different

reading of the 1976 opinion as "deliberately false," and

denounced the motion as an "outrageous" attempt to "backdate" the

limitations date in Swint.6 On April 16, 1984, Judge Guin

declined to modify his 1976 order, but made clear that the 1976

order was not intended to bar the Larkin plaintiffs from seeking

redress in Swint:

[T]he judgment need not be modified or

expounded upon because the court finds that

the order is clear on its face.... This

court correctly stated in its order that, as

J Letter of Elaine Jones to Hon. J. Foy Guin, March 23,1984.

4 Motion for Relief from Judgment, p. 2-3.

5 Defendant's Memorandum in Opposition to Motion, p. 5.

Id. at 4, 7; see also id. at 11 ("outrage,"

"transparently false claim"), 12 ("a scandal in any civilizedsystem of justice."

9

members of the class whose case had already

been heard on the merits, the plaintiffs

named in the above-styled cause were barred

by either res judicata or collateral

estoppel.... The court expressed no opinion

as to the rights which these plaintiffs might

have as unnamed members of the Swint class.

(R.E.,pp. 79-80). This explanation reflected Judge Guin's

original understanding in 1976, to which he adhered in 1984, that

the claims of the Larkin plaintiffs were being "heard on the

merits" in Swint. On May 11, 1984, plaintiffs appealed Judge

Guin's refusal to remove the words "with prejudice" from his 1976

order. This court stayed proceedings in the Larkin appeal

pending disposition of the Swint remand.

(ii) Statement of the Facts

The facts of this case are set out in detail in the

prior decisions of this court and the district court. We

summarize briefly the circumstances of particular importance.

Until its closing Pullman-Standard's Bessemer plant was

one of the largest facilities in the United States assembling

railroad cars. The plant was divided into 28 departments, 26

represented by the United Steelworkers of America and 2

represented by the International Association of Machinists. The

volume of work and thus the number of employees at the plant

varied widely from month to month; at times the plant was working

on as few as 25 cars, on other occasions the plant had several

thousand cars on order. For this reason virtually all workers

were laid off and recalled repeatedly over the course of their

10

careers and even during a single year. 11 FEP Cas. at 945-46 and

nn. 3, 4 .

The wage for a particular position depended on its job

classification; those classifications ranged from JC 1 for the

lowest paid jobs to JC 20 for the highest. As of 1973, for

example, a JC 20 job paid $5.39 per hour, while a JC 1 job paid

$3.63 per hour. (15 FEP Cas. at 946 n. 8.)^ Newly hired workers

were assigned to a specific job and department. When a vacancy

arose in a higher paying position in a department, employees were

not notified of the vacancy or permitted to bid on it. Rather,

the relevant supervisor would simply assign a department employee

to that position. 11 FEP Cas. at 959. In the 2 6 departments

represented by the Steelworkers, management was required by the

collective bargaining agreement to select the worker with the

greatest departmental seniority. The company could pass over the

senior employee if it believed he lacked the ability to do the

job, but at least prior to 1965 it was the general practice at

the plant to provide any needed training on an informal on-the-

job basis.

Prior to 1965 job assignments at the plant were

avowedly made on the basis of race. The defendants did not,

however, simply utilize a crude system of all-white and all-black

departments. Rather, the segregation took a more sophisticated

form, with individual jobs being reserved for whites and blacks

This is the classification scheme in the 26

Steelworkers departments. Wages in the 2 I AM departments are

generally comparable to or higher than the wage for a JC 10 job.

11

respectively. When a vacancy arose in a "white" job it was

filled by a white, regardless of the qualifications or seniority

of blacks in the department. 11 FEP Cas. at 947; 15 FEP Cas. at

147 n. 7, 148. Virtually all of the best jobs in the plant were

reserved for whites:

Employees by Job Class (PX 1038, pp. 1-2)

Job Class Whites Blacks Percent Wh

JC 16-20 38 2 95.0%JC 15 12 0 100.0%JC 14 15 2 88.2%JC 13 23 0 100.0%JC 12 62 1 98.4%JC 11 64 9 87.7%JC 10 1 1 1 49 94.1%JC 9 46 13 78.0%JC 8 36 27 57.1%JC 7 19 32 37.3%JC 6 135 567 19.2%JC 5 4 72 5.3%JC 4 136 220 38.2%JC 3 2 5 28.6%JC 2 8 121 6.2%JC 1 3 14 17.6%

More than 71% of all whites were at JC 10 or above, compared to

less than 6% of blacks. The racial composition of individual

departments turned on the JC rating of jobs in the department.

Some departments, with only low JC jobs, were as a result all

black; some departments, with only high JC jobs, were as a

consequence all-white. Most departments, however, had both high

and low JC jobs, and were therefore racially "mixed." 11 FEP

Cas. at 950. In the mixed departments, however, blacks were

generally restricted to the low JC jobs.

12

Although there are a total of 28 departments at the

plant, almost all of the lucrative jobs were concentrated in just

four departments. Out of approximately 1,250 jobs classified as

JC 10 or above, about 1,100, or 87% were in four departments—

the welding department, the IAM die and tool department, and the

two maintenance departments. Welding alone, with about 845 jobs

at JC 10 and above, had 67% of the best paid jobs at the plant.

Among the 2,545 whites employed in 1964, about 76% were in these

four key departments. Among the 1,325 blacks, on the other hand,

only 230, or 17% were in these four departments. (See PX 20)

In 1980 the Fifth Circuit concluded that

discriminationO in the assignment of newly hired workers had

continued after the enactment of Title VII. 624 F.2d. at 528-30.

In 1965 the average white hire was assigned to a job class almost

three classes higher than the average black hire of that year;

not until well into the 1970's did such discrepancies disappear:

13

Average Job Class

of Newly Hired Employees8

Year of

Hire White

1965 8.18 (292 hires)

1966 6.99 (339)

1967 9.93 (213)1969 8.20 (385)1970 7.11 (134)1971 7.10 (727)

1973 9.85 (101)1974 6.99 (991)

Black Difference

5.27 (164 hires) 2.915.41 (151) 1.587.71 (24) 2.226.64 (215) 1.566.24 (86) .876.47 (318) .639.43 (76) .426.94 (543) .05

In 1966 the job assignments of workers hired in that year were as

follows:

1966 Job Classifications of

________ 1966 Hires________

(PX 1038, p. 3)

Job

Classification White Black Percent White

JC 11-20 17 3 85.0JC 10 99 20 83.2JC 7-9 19 3 86.4JC 6 57 42 57.6JC 4-5 123 66 65.0JC 1-3 14 17 45.2

For employees hired in 1966 and thereafter, the disparity between

blacks and whites generally rose with each year they remained at

the plant:

8

1968. PX 1038, pp. 17-29. There were no hires in 1972 or

14

Job Increase in Black/White

Class Differential bv Year of Hire

(PX 1038, pp. 17-29)

Difference in DifferenceYear of Hire Year of Hire 1974

1966 1.58 3.341967 2.22 3.411969 1.56 1.931970 .87 .941971 . 63 1.561973 .42 .57

As of 1974 the disparities between the job classifications of

blacks and whites hired in 1966-67 were actually greater than the

disparities between blacks and whites hired during the pre-1966

era of avowed racial discrimination.

During the decade after the adoption of Title VII, few

blacks who had been hired and assigned to lower paid black jobs

prior to 1965 were able to move into the higher-rated white jobs.

As of 1965 over 70% of all whites were assigned to jobs with a JC

rating of 10 or above, comparOed to less than 10% of all blacks;

in 1974 the proportion of blacks hired before 1965 who had

reached the JC 10 level or above was still under 20%:

Proportion of Pre-1965 Hires

Assigned to JC 10 and Above

(PX 1038, pp. 22-23)

1965 1974Year of Hire White Black White Black

Pre 1950 68% 5% 70% 14%1950-54 75% 9% 74% 22%1950-59 74% 8% 78% 20%1960-64 79% 3% 84% 13%

The difference in the average job class of blacl

declined only slightly from 1965 to 1974 :

15

Pre-Act Hires

Year of Hire

Black/White Job Class

Differential bv Year of Hire

(PX 1038, p.

1965 Differential

29)

1974 Differential

Pre-1950 3.64 3.251950-54 4.48 3.291955-59 4.04 3.411960-64 4.37 3.90

From 1965 through 1973 the average job classification of newly-

hired whites was always higher than the average classification of

the more senior pre-1965 blacks.^ As a general practice, in the

years after 1965 Pullman—Standard chose to fill vacancies in

higher paying jobs by hiring new white employees, rather than by

reassigning senior black employees.* 10

Under the departmental seniority rules in effect at the

Bessemer plant, an employee who moved into a new department lost

a11 his seniority; for purposes of assigning workers to better

jobs, and for layoffs and recalls, a transferring employee's

seniority was based on the day he entered the new department. 11

FEP Cas. at 94 6. Because of the large number of layoffs and

recalls at the plant, an employee with 10 or 2 0 years seniority

might enjoy relatively steady work in his original department,

but would be employed only intermittently if he changed

Id. at 29. In 1973, for example, the average job

classification of a newly hired white was 9.85, while the average

classification for pre-1965 blacks ranged from 6.10 to 6.87.

10 In 1967, for example, the company hired 199 new employees into jobs at JC 10 or above, all but 11 of whom were

white, despite the fact that there were then over 1000 existing black employees in jobs below JC 10. Id. at 1-4.

16

departments. Not surprisingly, there was only a minuscule number

of transfers between departments. In the era after the adoption

of Title VII, an average of only 17 employees a year changed

departments at the plant, out of an annual workforce of

approximately 2,500. (DX 1208, p. 15).

In 1972 the Labor Department entered into an agreement

with Pullman-Standard designed to provide very limited relief

from the deterrent effect of this departmental seniority rule.

11 FEP Cas. at 947-48. Under the agreement, blacks in four small

traditionally black departments who had been hired prior to April

30, 1965, were permitted to transfer to any other department

without loss of seniority.11 Out of about 1,100 black employees

at the plant in 1972, however, only 88 were eligible for this

transfer, and 30 of them were already in better paid JC 9 jobs.12

The agreement also permitted any black hired prior to April 30,

1965, to transfer without loss of seniority into five small

traditionally white departments.13 Out of approximately 1,250

jobs classified at JC 10 and above, however, only 36 were located

in the 5 departments ;into which all pre-1965 blacks could

transfer. (See PX 20) . Vacancies in these 36 jobs of course

arose only occasionally; how many, if any, vacancies actually

11 The departments were Janitor, Steelworkers Die and Tool, Truck, and Steel Miscellaneous. 11 FEP Cas. at 948.

12 PX 19; Die and Tool (2 eligible employees), Janitors (7

eligible employees), Steel Miscellaneous (64 eligible employees,

30 of them already at JC 9), Truck (15 eligible employees).

13 The departments were Airbrake Pipe Shop, Inspection, Plant Protection, Powerhouse and Template.

17

occurred between 1972 and the 1980 plant closing is not revealed

by the record. Overall, despite this 1972 agreement, 98% of all

jobs at or above JC 10 were still effectively closed to 92% of

all blacks at the plant. Black employees who were eligible for

these transfers were not entitled to red circling, and thus might

face a pay cut upon moving into an entry level position in a

traditionally white department. 539 F.2d at 101. Not

surprisingly the Labor Department agreement had very little

impact; only 17 blacks actually transferred under that program.

(CDX 1208, p. 15). The Labor Agreement had absolutely no effect

on the opportunities of the overwhelming majority of blacks at

the plant.

(iii) Standard of Review

This appeal presents a large number of issues, most of

which are entirely legal in nature and which are thus subject to

de novo consideration by this court. In parts II (assignment

discrimination) and IV (seniority system), we urge that certain

factual findings made by the district court are clearly

erroneous.

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

(1) In its 1980 opinion the Fifth Circuit in Swint found

that there had been classwide post-Act discrimination in

assignments and in the selection of foremen. The court of

appeals set the limitation date as September 28, 1966, and

remanded the case for an award of back pay. On remand the

18

district judge in Swint improperly changed the limitations cut

off date to July 17, 1969.

This new limitations date in Swint is inconsistent with

the dismissal of the complaint in Larkin. Larkin was dismissed

on the assumption that the claims of the Larkin plaintiffs were

being litigated in Swint. The specific discriminatory acts

complained of by the Larkin plaintiffs occurred in 1966 and 1967.

If the Swint cut-off date is 1969, then the Swint litigation does

not encompass the claims of the Larkin plaintiffs, and Larkin was

improperly dismissed.

The Title VII cut-off date in Swint is no later than

September 28, 1966, 180 days prior to the EEOC Commissioner's

charge of March 27, 1966. Title VII clearly contemplates that an

aggrieved individual may sue on the basis of a Commissioner's

charge. Inda v. United Airlines. 565 F.2d 554 (9th Cir. 1977).

The section 1981 cut-off date in Swint is October 19,

1965, six years before the filing of the complaint. The

limitations period for a section 1983 claim arising in Alabama is

6 years. Jones v. Preuitt & Maudlin. 763 F.2d 1250 (11th Cir.

1985) . The same limitations rule must be utilized in a section

1981 case, and should be applied to all pending cases. Goodman

v. Lukens Steel Co.. 55 U.S.L.W. 4881 (1987).

(2) In his 1974 opinion Judge Pointer found that assignment

discrimination at the Inspection, Air and Brake, and Steelworkers

Die and Tool departments had continued until 1970 and 1971. The

defendants chose not to appeal that finding, which became the law

19

of the case. The district court had no authority to thereafter

reopen the question and hold that all discrimination ended in

February, 1969.

It was clear error to hold that assignment

discrimination at the two I AM departments ended in February,

1969. Both departments were all-white in 1965; between 1965 and

1969 every one of the several new employees assigned to these

departments was white. No black was assigned to an IAM

department until at least 1970.

(3) The complaint in Larkin alleged that the company

"discriminated against blacks by excluding them from its more

desirable jobs." (R.E., p. 64). The EEOC charges of Larkin and

the other Larkin plaintiffs were particularly concerned with

discrimination in the assignment of existing employees to better

paid jobs in their own departments. Judge Guin in 1976 dismissed

Larkin on the assumption that those claims were within the scope

of the Swint litigation. On April 16, 1984, in denying our

motion for relief from judgment in Larkin. Judge Guin made clear

that he had not decided the Larkin claims on the merits, but was

merely ruling that those claims had been or could be resolved in

Swint. Two weeks later, on May 1, 1984, Judge Pointer ruled that

discrimination in the assignments of existing employees was not

and never had been within the scope of the Swint litigation. (R.

20

v. 14, p. 50.)14 Clearly these two decisions are inconsistent,

and one must be reversed.

(4) The district court found, as had the Fifth Circuit in

1980, that the I AM was racially motivated in 1941 when it

gerrymandered department lines to exclude all blacks from IAM

seniority units. The resulting system, which divided on racial

lines both the then existing Maintenance department and the Die

and Tool department into two new units, was not bona fide.

The departmental seniority rules in the Pullman-

Standard-Steelworkers contracts were maintained with a

discriminatory purpose. Under the facially neutral terms of

those contracts, vacancies were to be awarded to the most senior

departmental employee, regardless of race. In practice, however,

at least until 1965, a vacancy in a "white" job was reserved for

and filled only by a white, regardless of whether the senior

department employee happened to be a black

STATEMENT OF JURISDICTION

The decision of the district court in Swint was entered on

September 8, 1986. On September 18, 1986, both plaintiffs and

the company defendant filed motions to alter or amend that

decision. On November 15, 1986, the district court denied those

motions. On November 25, 1986, the district court entered a

final judgment under Rule 54. On December 18, 1986, the

14 "R"

court record. cites are to the volumes of the original district

21

plaintiffs filed a notice of appeal. Jurisdiction over this

appeal exists under 28 U.S.C. § 1291.

On March 23, 1984, the plaintiffs in Larkin filed a motion

for relief from judgment in that case. The district court denied

that motion on April 16, 1984, and plaintiffs filed a notice of

appeal on May 11, 1984. Appellate proceedings in Larkin were

thereafter stayed pending developments in Swint. Jurisdiction

over this appeal arises under 28 U.S.C. § 1291.

ARGUMENT

I. THE COURT BELOW ERRED IN REFUSING TO PROVIDE A REMEDY FORDISCRIMINATION OCCURRING PRIOR TO JULY 17. 1969___________

In 1980 the Fifth Circuit held that the defendants during

the years after the enactment of Title VII had continued to

engage in at least two unlawful discriminatory practices. First,

employees continued to be assigned on the basis of race to

particular jobs and departments. The court of appeals emphasized

that prior to 1970 all employees assigned to certain tradition

ally white departments were still white. 624 F.2d at 529.

Second, the Fifth Circuit found that there had been unlawful

discrimination in the selection of foremen from among the plants

hourly employees. It noted that although blacks constituted 45-

50% of the pool of employees from whom foremen were chosen, there

were no black foremen in June 1965, and that from 1966 until 1974

only 12 blacks were promoted into foremen jobs. 624 F.2d at 527-

28, 534-36.

22

The Fifth Circuit's 1980 opinion contemplated that the

limitations period for which backpay would be awarded on remand

would commence no later than 1966. 624 F.2d at 528 n. 1. This

case presents three independent bases for that 1966 cut-off date.

First, the discriminatory practices at issue were the subject of

a March, 1967, Commissioner's charge? litigation under this

charge encompasses claims arising 180 days earlier, since the

charge itself was still pending when Congress enacted the 180 day

rule as part of the 1972 Title VII amendments. Second, the

discriminatory practices at issue were the subject of individual

Title VII charges filed in November, 1966 and April, 1967; these

charges too were pending in 1972 and thus encompass claims

arising 180 days before the date on which they were filed.15

Third, the complaint filed in 1971 alleged a cause of action

under 42 U.S.C. § 1981 as well as under Title VII; the

limitations period for a section 1981 claim arising in Alabama is

six years. Jones v. Preuitt & Maudlin. 763 F.2d 1250 (11th Cir.

1985).

In his 1977 opinion Judge Pointer had expressly agreed that

the limitations period commenced in 1966. This court's 1984

remand contemplated that Judge Pointer would provide backpay for

the assignment discrimination identified by the Fifth Circuit.

Instead of providing that remedy, however, Judge Pointer on

The limitations date would be in September, 1966, under

the Commissioner's charge, and May 1966 under the earliest

individual chart; we urge the court to adopt the latter cut-off date.

23

remand overturned his own 1977 opinion, disregarded the Fifth

Circuit's 1980 decision, and changed the cut-off date from 1966

to 1969. Judge Pointer refused to base the Title VII cut-off

date on either the 1967 Commissioner's charge or the 1966 and

1967 individual charges, and applied to the section 1981 claim a

one year limitation period

(1) The Pre-1980 Decisions in Swint Regarding the Relevant Limitations Period

In its pre-trial order of June 4, 1974, the district court

defined the class to include any black employed at the Bessemer

plant "within one year prior to the filing of any charges under

Title VII." (R.E., p. 60) (Emphasis added). This unambiguous

order was not limited to the EEOC charge filed by the named

plaintiff in Swint itself, but extended to "any" charges. The

significance of this order was unquestionably clear to the

parties. Since, as was well known to counsel, a total of four

different charges had been filed against Pullman-Standard prior

to the end of 1967, it was evident that under the 1974 pre-trial

order the class claims encompassed individuals employed, and

claims arising, as early as 1966.16

When this case was first tried in July and August of 1974,

much of the evidence dealt with alleged discriminatory acts

occurring between 1966 and 1969.17 In its 1974 opinion the

16 The Larkin charges were discussed during the 1974 trial. R. v. 3, pp. 39-40, 162-63, 189-90.

17 See, e.g., R. v. 3, pp. 126-27, 160-61, 182; R. v. 4,

pp. 263-64, 416, 512; R. v. 5, pp. 554-56, 601-04, 611; R. V. 6,pp. 751, 753, 833-34, 891.

24

district court again noted that it was resolving the class claims

"of all black persons who at any time subsequent to one year

prior to the filing of any charges with EEOC had been employed at

Pullman (at its Bessemer plant)". 11 FEP Cas. 944, 948 n.20

(N.D. Ala. 1974) (Emphasis added).

On appeal we expressly asserted in the statement of the case

in our 1975 brief that the effect of the 1974 pre-trial order was

to include within the scope of the class individuals employed by

Pullman-Standard since the spring of 1966. We referred in

particular to the January 1967 Commissioner's charge and the

April, 1967, individual charges.18 Although both the company and

the union included in their 1975 briefs a "counter statement of

the case",19 neither disputed our description of the scope of the

class claims, objected to the terms of the 1974 pre-trial order,

or suggested that the 1967 charges were an inappropriate basis

for determining the commencement of the limitations period.

In 1976 the Fifth Circuit reversed the trial court's 1974

decision, and remanded the case for further proceedings. The

court of appeals noted that the class consisted of "all black

persons who at any time subsequent to 1 year prior to the filing

of any charges with the EEOC had been employed by Pullman-

Standard." 539 F. 2d 77, 85 n.17 (5th Cir. 1976) (Emphasis

18 Brief for Plaintiffs-Appellants No. 74-3726, pp. 2-3 and n.2.

19 Brief of Defendant Appellee Pullman-Standard, No. 74-

3726, p p . 3-6; Brief for Defendants-Appellants United

Steelworkers of America, etc., et al., No. 74-3726, pp. 2-6.

25

added). On remand the district judge held, pursuant to the terms

of the pre-trial order, that the class claims encompassed

discrimination in or after late 1966. 15 FEP Cas. 144, 146 n.5,

147 (N.D. Ala. 1977). The case was retried and decided in 1977

on the basis of this 1966 cutoff date. The district judge held

regarding discrimination in assignments and promotions to

supervisory positions that both practices had ended prior to the

1966 cut-off date. 15 FEP Cas. at 150, 153.

In the 1980 appeal the company again chose not to challenge

the 1966 cut-off date set by the district court. On the

contrary, although the district court had established a cut-off

date in December of 1966, Pullman-Standard referred to September

29, 1966, as the beginning of "the earliest possible limitations

period."20 The company urged the Fifth Circuit to decide on the

merits whether there had been discrimination during "the

limitations period" considered by the district court.21 In its

1980 decision the Fifth Circuit noted that the district court had

set the limitations date at December 27, 1966, 90 days prior to

the EEOC commissioner charge of March 27, 1967; the court of

appeals held that, because of the 1972 amendments to Title VII,

the correct date should have been 180 days prior to that charge,

September 28, 1966. 624 F.2d 525, 528-29 at n. 1 (5th Cir.

20 Brief of Defendant-Appellant Pullman-Standard, No. 78- 2449, p. 50. In a subsequent 1977 order the district judge had

indicated that the September 28, 1966 date was "probably

correct." Swint v Pullman-Standard. 15 FEP Cas. 1638, 1639 (N.D. Ala. 1977).

21 Id. at 56, 67.

26

1980). The appellate court concluded, with regard to the merits,

that discrimination in both assignments and supervisory

promotions had occurred subsequent to that date. 624 F.2d at

528-30, 534-36.

When this case was remanded to the district court in 1983,

plaintiffs requested that court to establish as the anterior cut

off September 28, 1966, the date specified in the Fifth Circuit's

1980 opinion.22 in June, 1983, the Pullman-Standard company

asserted in response that the cut-off date should be July 17,

1969, 90 days prior to the filing of Swint's personal charge; the

company described our proposal of a 19 66 cut-off date as an

attempt to "push[] back" the time limit, "to enlarge the scope of

litigation," and "to enlarge the time dimension of the case."* 23

On September 19, 1983, the district court issued a pre-trial

order which expressly deferred any decision regarding "which EEOC

charge will control". (R.E., p. 70). The court admonished that

"for the purposes of trial preparation, counsel should assume the

anterior cut-off date is 180 days prior to October 30, 1966," the

date of the Spurgeon Seals' charge. (Id.) The 1984 trial

proceeded on the assumption that the anterior cut-off date was

Plaintiff's Motion for a Determination of the Earliest Proper Charge Related to the Issues in the Case, filed June 6, 1981.

23 Defendant Pullman's Response to Plaintiff's Motion for

a Determination of the Earliest Proper Charge Related to the Issues in this Case, pp. 1, 3, 5.

27

1966. In its September, 1986 opinion, however, the district

court set the cut-off date as July 17, 1969. (Id. at 113).

(2) The 1969 Limitation Date in Swint is Inconsistent with the Decision in Larkin

If this court now upholds Judge Pointer's 1986 decision

establishing a 1969 cut-off date, it must overturn Judge Guin's

197 6 and 1984 orders holding that the claims of the Larkin

plaintiffs were within the scope of the Swint class, and could

thus be pursued only in Swint itself.

When Larkin was first filed, the company expressly asserted

that the claims of the Larkin plaintiffs were being litigated in

Swint. (R.E., p. 67) Judge Guin dismissed Larkin because "all

issues presented by the complaint are presently on appeal" in

Swint. (R.E., p. 69). Insofar as the limitations issues were

concerned in 1976, Judge Guin was correct. Although the claims

of the Larkin plaintiffs arose in 1966 and 1967, the Swint class

action, at the time of Judge Guin's 1976 decision, did encompass

class claims for 1966 and 1967. In 1984 Judge Guin reiterated

his original understanding that the claims of the Larkin

plaintiffs "had already been heard on the merits" in Swint.

(R.E., p. 80). Again, that was as recently as 1984 an accurate

description of the temporal scope of the Swint class claims.

In September 1986, however, Judge Pointer announced that he

would limit Swint class claims to claims arising after July,

1969; the new cut-off date was two to three years after the

original individual claims of Larkin, Seals, Lofton and Terry.

Judge Pointer concluded, with regard to the merits in Swint. that

28

assignment discrimination lasted until 1969, and that supervisory

promotion discrimination lasted until 1974. (R.E., pp. 114-15,

118-21) . But because he had redefined the scope of the class

claims, Judge Pointer necessarily refused to hear on the merits

any claim arising in 1966, 1967 or 1968 including those of the

Larkin plaintiffs themselves. In sum, Judge Guin decided in 1976

to dismiss Larkin because he believed that the claims of the

Larkin plaintiffs were being presented and heard in Swint; ten

years later Judge Pointer decided he would not hear and decide

those claims after all, at least insofar as the Larkin plaintiffs

were complaining of discrimination in 1966 and 1967, the dates of

their actual EEOC charges. If Judge Pointer's decision is

upheld, Judge Guin's decision must now be reversed.

(3) The Title VII Cut-off Date In Swint Is No Later Than September 28. 1966__________ _________________ ______

(a) The Limitations Period May Be Based on the March 27. 1967 Commissioner's Charge

In his 1977 decision Judge Pointer held that the cut-off

date should be based on the March 27, 1967, Title VII charge by

EEOC Commissioner Shulman, 15 FEP Cas. at 146 n. 3, a view

concurred in by the Fifth Circuit. 624 F.2d at 528-29 n. 1. On

remand, however, following the Fifth Circuit's holding that the

company had engaged in post-Act discrimination, Judge Pointer in

1986 reversed his earlier decision and held that the temporal

scope of this action could not be based on that Commissioner's

charge. Judge Pointer reasoned that while a Commissioner's

charge might provide a basis for a suit by the government, a

29

private party could never rely on a Commissioner's charge which

had not led to such a government lawsuit. (R.E., No. 87-7057,

pp. 4-6).

The language and legislative history of Title VII make

abundantly clear that a private claimant may indeed rely on a

Commissioner's charge. Inda v. United Airlines. 565 F.2d 554,

559 (9th Cir. 1977). Section 706(e) provides that, if EEOC has

been unable to resolve a charge through conciliation,

a civil action may ... be brought against the respondent

named in the charge (1) by the person claiming to be

aggrieved; or (2) if such charge was filed by a member of

the Commission, by any person whom the charge alleges was

aggrieved by the alleged unlawful employment practice.

Subsection (2) manifestly authorizes private civil suits based

on a Commissioner's charge. The legislative history of the

statute confirms its plain meaning. Although the original

language of the House bill authorized the EEOC itself to sue on

the basis of a Commissioner's charge, the Senate bill, which

ultimately became Title VII, gave the EEOC itself no such

authority. EEOC, Legislative History of Titles VII and XI of

Civil Rights Act of 1964. 3003-04. Senator Saltonstall explained

The section has been modified so that the Commission itself

cannot bring suit.... A single member ... may file a charge

with the Commission . . . but the individual must take it to

court, if ... the Federal Commission is not able to arrive

at an agreement for voluntary compliance. (Id. at 3304)

Other members of the Senate expressed a similar understanding

that individuals could bring suit on the basis of Commissioner's

charges. Id. at 3307 (Sen. Yarborough), 3312 (Sen. Cotton).

30

Judge Pointer argued, in the alternative, that the

Commissioner's charge "did not list any of the named plaintiffs

or would-be intervenors as aggrieved or charging parties."

(R.E., No. 87-7057, p. 47). But section 706(e) does not restrict

civil suits based on a Commissioner's charge to those

individuals, if any, whose proper names might be listed in the

Commissioner's charge; on the contrary, the language of the

statute extends more broadly to "any person whom the charge

alleges was aggrieved by the alleged unlawful employment

practice." It is inconceivable that Congress intended to require

that a Commissioner's charge literally contain a list of names of

aggrieved individuals, since one of the primary purposes of

Congress in authorizing Commissioner's charges was to permit

Commission action where aggrieved individuals were afraid to be

named complainants. 1964 Legislative History, pp. 3305 (Sen.

Case), 3311 (Sen. Keating). The EEOC regulations implementing

section 706(e) do not require that a Commissioner's charge list

specific aggrieved persons, but provide for the issuance of a

right-to-sue letter to any individual who is a member of the

class of persons identified by the charge as aggrieved by the

alleged discrimination. 29 C.F.R. §§ 1601.28(a),

1601.28(b)(3)(ii). The EEOC regulations interpreting Title VII

are entitled to considerable deference. EEOC v. Shell Oil Co. .

466 U.S. 54, 79 n.36 (1984); Griggs v. Duke Power Co. . 401 U.S.

424, 433-34 (1970).

31

It is thus clear that Louis Swint, William Larkin, or any

other of the more than 2 000 class members could now obtain a

right-to-sue letter under the 1967 Commissioner's charge and

bring a new class action. Title VII, however, surely does not

require that the plaintiffs proceed in this cumbersome manner.

(b) The Limitations Period May Be Based On Title VII

Charges Filed in 1966 and 1967 by Class Members Who Are Not Named Plaintiffs

The earliest EEOC charge by a member of the plaintiff class

was dated October 30, 1966, and was filed on November 4, 1966, by

Spurgeon Seals. Subsequent charges were filed in 1967 by Seals,

William Larkin, Edward Lofton and Jesse Terry, who were all

members of the Swint class, although not named plaintiffs in that

litigation. In his 1986 opinion, however, Judge Pointer held

that the limitations date could only be based on the 1969 charge

filed by the named plaintiff Louis Swint. Judge Pointer reasoned

that a limitations cut-off date could be based only on a Title

VII charge filed by a named plaintiff, regardless of whether, as

here, there were a significant number of earlier charges filed by

other class members.

The district court relied on the statement in Payne v.

Travenol Laboratories. 673 F.2d 798 (5th Cir. 1982), that, "The

opening date for membership in a class in a Title VII claim

should be set by reference to the earliest charge filed by a

named plaintiff." 673 F.2d at 813. (R.E. p. 109 and n. 3) In

Payne, however, there is no indication that any class member

other than the named plaintiff had filed a charge with EEOC, or

32

that the parties had asked the court to decide the legal

significance of such charge filed by a class member who was not a

named plaintiff. It would be inappropriate to read into the

language of Payne an intent on the part of the court of appeals

to address a legal issue which the parties had not presented and

which the panel itself appears not to have contemplated.

The governing principle regarding Title VII class actions

is that " [o]nce a complaint has been filed with the EEOC, the

applicable statute of limitations is tolled." Johnson v.

Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co.. 491 F.2d 1364, 1378 (5th Cir. 1974);

see also Pettway v. American Cast Iron Pipe Co. . 494 F.2d 211,

258 (5th Cir. 1974); United States v. Georgia Power Co.. 474 F.2d

925, 906 (5th Cir. 1973). This tolling rule follows from the

very rationale of the 180 day filing requirement, which is to

provide for notice to the filing party, and to bring to bear the

compliance and conciliation functions of the EEOC. zipes v.

Trans World Airlines. 455 U.S. 385, 394 (1982). Once a

discriminatory practice has been the subject of an EEOC charge,

the statutory purpose has been fully satisfied; no legitimate

further purpose would be fulfilled by requiring other employees

to file additional charges reiterating the very grievance of

which the respondent already has notice, and which is already the

subject of EEOC proceedings.

The filing of EEOC charges in 1966 and 1967 by Seals,

Larkin, Lofton and Terry tolled the filing period for all other

black employees with similar claims, including the period

33

applicable to Louis Swint. Although Swint only filed his own

charge in October, 1969, the effect of the tolling triggered by

the earlier charges was that Swint's own claim reached, not 180

days prior to his own charge, but 18 0 days prior to the Seals

charge. If Swint himself had never brought his own action, the

substantive issues would have been litigated and resolved in the

Larkin litigation, and the anterior cut-off date, for Swint and

all other blacks at the plant, would have been 1966. It is

inconceivable that Swint somehow expunged this tolling effect,

and forfeited his own claims for the years 1966-68, because he

brought his own suit in 1971 rather than waiting for Larkin,

Seals, Lofton or Terry to sue. The equitable benefits of a

tolling rule may sometimes be lost by those who sleep on their

rights, but no court has ever fashioned a tolling rule which

penalizes litigants who sue too soon.

(c) The_District Court Improperly Denied the Motion ofLarkin, et al. to Intervene in Swint

On June 4, 1984, counsel for plaintiffs, anticipating the

limitations problems raised two years later by the 1986 opinion,

filed a motion to intervene in Swint on behalf of Larkin, Seals,

Terry, and Lofton, all of whom, of course, were already members

of the Swint class. The motion was denied without opinion on

September 4, 1984; the district court explained that denial two

years later in its 1986 decision on the merits. (R.E., pp. 110-

111) .

Judge Pointer argued, first, that intervention would

"broaden the temporal scope of the case, potentially increasing

34

the liability of the defendants fifteen years after the case was

filed." (Id. at 111). That assertion was clearly incorrect.

Only a year before the motion to intervene, Judge Pointer had

issued a pre-trial order instructing counsel that the 1984

retrial would encompass class claims arising in and after 1966.

(Id. at 70) . Judge Pointer in his 1977 opinion had also used a

1966 cut-off date. The year 1966 had since the 1974 pre-trial

order defined the outset of "the temporal scope of the case." It

was not until September 1986, some two and one-half years after

the motion to intervene, that Judge Pointer moved the cut-off

date to July, 1969.

Judge Pointer also insisted that denying intervention would

not cause Larkin, et al. . any "significant prejudice." Larkin

and the others, Pointer asserted,

are class members whose interests are adequately

protected by the class representatives. They will

hardly be deprived of their "day in court," as plaintiffs contend. (Id. at 111).

The individual EEOC charges of Larkin, Seals, Terry and Lofton

concerned alleged acts of discrimination in 1966 and 1967.

Having denied their motion to intervene, Judge Pointer then

restricted the Swint claims to discrimination occurring after

July, 1969, thus expressly refusing to consider the very claims

that they had raised with the EEOC. In a sense, of course,

Larkin and the others had more than a day in court; their claims

were within the scope of the Swint litigation for over 12 years,

from the June 4, 1974 pre-trial order until the September 6, 1986

opinion. But having accorded Larkin, Seals, Terry and Lofton

35

over a decade in court, Judge Pointer finally and simply refused

to decide the merits of their claims.

Finally, Judge Pointer found the motion for intervention

untimely; indeed, he went on to denounce counsel for plaintiffs

for "inexcusable delay" and "lack of diligence." (Id. at 110-

11) . The touchstone of timeliness, however is the point in time

at which it became clear that the named plaintiffs in Swint would

not be permitted to represent the interests of the Larkin

intervenors by pursuing claims arising in 1966 and 1967. United

Airlines Inc, v. McDonald. 432 U.S. 385, 394 (1977). No such

problem existed in 1975-76 when the Larkin intervenors received

their right-to-sue letter; on the contrary, the parties in Swint

then clearly agreed that 1966-69 claims were within the scope of

that case. No such problem existed in 1977 or 1980 when the

district court and court of appeals, respectively, held that the

cut-off date in Swint was 1966. The Larkin plaintiffs were not

put on notice that their 1966-69 claims could not be presented by

the named plaintiffs in Swint; until September 6, 1986, when the

district court so limited the scope of the Swint proceeding.

That clear notice, of course, came two and one half years after

the Larkin plaintiffs took the precautionary step of moving to

intervene in Swint.

We urged above that the district court erred when, in 1986,

it shifted the limitations cut-off date from 1966 — the date

which had been repeatedly approved by the courts since 1974 — to

1969. Even if such a change were possible, Judge Pointer surely

36

erred when he penalized the Larkin plaintiffs for having relied

on the judge's own repeated insistence that the Swint case did

encompass their claims.

(d) The Defendants Have Waived Any Limitations Defense To

Claims Arising in or After 1966______________________

Although Title VII requires that a charge be filed with EEOC

within 180 days of the alleged discrimination, this rule is not

jurisdictional in nature, but merely establishes a statute of

limitations. Zipes v. Trans World Airlines. 455 U.S. 385, 394-98

(1982) . Like any other statute of limitations rule, the defense

afforded by the 180 day rule "is subject to waiver, estoppel, and

equitable tolling." Id. at 393.

Under Rule 8(c) of the Federal Rules of Civil Procedure, any

such statute of limitations defense must be affirmatively pleaded

in a defendant's answer. In a class action, of course, the

temporal scope of the class claims may not be apparent on the

face of the complaint; where that is the case, however, the

requirements of Rule (8) (c) certainly apply as soon as the

temporal scope of the asserted claims becomes known. Even if the

180 day limitations defense is raised in an appropriate pleading,

the defense is necessarily waived if a defendant thereafter fails

to actually press the defense in a timely manner during the

course of the litigation. Zipes. 485 U.S. at 398; Mohasco Corp.

v. Silver. 447 U.S. 807, 811 n. 9 (1980)

The 1971 Answer of the Steelworkers contained a summary

assertion that the entire action was barred by the statute of

limitations. (R.E., pp. 38, 48) However, since the 1971

37

complaint alleged that the then-existing practices of the

defendants were unlawful, any contention that the entire claim

was untimely would clearly have been frivolous. The union itself

never took this argument seriously or actually argued that all of

the class claims were untimely. The company asserted in its 1971

Answer that the section 1981 limitations date was "six years

prior to the filing of the complaint," and that the Title VII

limitations date was "ninety days prior to the filing of any

charge or charges with EEOC", (R.E., pp. 37-38), a position it

disavowed 12 years later.

A defense assertion that class claims arising before a

particular date were time barred would not have been frivolous.

When the amended complaint was filed on June 5, 1974, it was

absolutely clear that the temporal scope of the alleged claims

extended far earlier than 1969. The pre-trial order of June 5,

1974, encompassed any black employed at Pullman-Standard within

one upon prior to the earliest EEOC charge; the defendants

certainly knew that the earliest such charge had been filed in

October 1966. (See R. E., pp. 86-88) Despite the fact that

plaintiffs were clearly seeking relief for violations occurring

as early as October 1965, neither the company nor the union

asserted in their supplemental answers that a portion of the

class claims were time barred. (R.E., pp. 60-72). No limitations

defense was raised during the 197 6 or 198 0 appeals. Not until

after the 1980 Fifth Circuit opinion, when this case had been

pending for over a decade, did either defendant question the 1966

38

cut-off date or suggest that in any way that some of the class

claims were barred by the 180 or 90 day limitations rule. So

long as they were prevailing on the merits, the defendants

acquesced in a 1966 cut-off date; had the defendants ultimately

prevailed on the liability issues, that 1966 cut-off date would

have determined the scope of the res judicata effect against the

class. Insofar as the plaintiffs seek to raise claims arising in

or after 1966, the defendants have long ago waived any

limitations defense they might have had under Title VII.

(4) The Section 1981 Cut-off Date In Swint Is October 19.1965^4

The complaint in this action also alleged a cause of action

under 42 U.S.C. § 1981 (R.E., p. 20). Because section 1981, like

section 1983, contains no specific statute of limitations, 42

U.S.C. § 1988 directs the federal courts to select and apply the

most analogous state statute of limitations. In Wilson v.

Garcia, 85 L.Ed.2d 254 (1985), the Supreme Court held that the

state limitations statute governing personal injury claims should

be applied to all section 1983 claims. In Jones v. Preuitt &

Maudlin. 763 F.2d 1250 (11th Cir. 1985), this court held that

section 6-2-34(1)(1975) of the Alabama Code, which applies to

various intentional torts, sets the appropriate limitations

period in a section 1983 case arising in Alabama. 763 F.2d at

1253-56. In Goodman v. Lukens Steel Co. . 55 U.S.L.W. 4881

^4 The difference between the Title VII and section 1981

cut-off dates is of importance because plaintiffs' disparate

impact claims are actionable only under Title VII.

39

(1987), the Supreme Court held that the same state limitations

statute applied to a section 1983 case must also be applied in a

section 1981 case. 55 U.S.L.W. at 4882-83. The complaint in

this action was originally filed on October 19, 1971;

accordingly, under Wilson. Jones and Goodman the section 1981

limitations cut-off date is six years earlier, October 19, 1965.

The district court below, however, refused to apply Wilson and

Goodman to the instant case, terming such an application

retroactive and unfair. (R.E., pp. 124-28).

The normal rule, of course, is that new Supreme Court

decisions are applied to all cases pending at the time those

decisions were handed down. The courts of appeals have been

unanimous in applying Wilson to any pending case in which Wilson

had the effect of lengthening the period of limitations.25 In

Goodman the Supreme Court held that, even where Wilson has the

effect of shortening the limitations period, Wilson must still be

applied unless, at the time a particular case was filed, there

was "clear Circuit precedent" setting a different limitations

period than is now required by Wilson. 55 U.S.L.W. at 4882-83.

In the instant case the district court insisted on applying

a one year statute of limitations based on the Alabama catch-all

limitations law, §6-2-39 (a) (5) , relying on Fifth Circuit

Bartholomew v. Fischl. 782 F.2d 1148, 1155-56 (3d Cir. 1986) ; Jones v. Shankland. 800 F.2d 77, 88 (6th Cir. 1986);

Farmer v. Cook. , 782 F.2d 780-81 (8th Cir. 1986); Jones v.

Preuitt & Maudlin. 763 F.2d 1250 (11th Cir. 1985); Riviera v.

Green, 775 F.2d 1381, 1383-84 (9th Cir. 1985); Marks v. Parra.785 F.2d 1419, 1419-20 (9th Cir. 1986).

40

decisions in 1973 and 1977.26 But Judge Pointer did not suggest

that Fifth Circuit precedent had endorsed any such a rule in

1971., the year this suit was filed. As of 1971 the only Fifth

Circuit precedent supported a 10 year limitations period in a

section 1981 action. Boudreaux v. Baton Rouae Marine Contr. Co..

437 F. 2d 1011, 1017 n. 16 (5th Cir. 1971). In its 1971 Answer,

Pullman Standard itself asserted that the limitations period

applicable to the section 1981 claim was "six years prior to

filing of the complaint." (R.E., p. 37). In 1972 Judge Pointer,

writing in Buckner v. Goodyear Tire and Rubber Co. . 330 F.Supp.

1108, 117-18 (N.D. Ala. 1972),- recognized the vague and

conflicting state of Fifth Circuit precedent, and noted that

when Buckner itself was tried, he himself had believed section

1981 was subject to a six year limitations period. 339 F.Supp.

at 1117 n. 10.

In his 1986 order in the instant case, Judge Pointer sought

to justify imposing a one year limitation by arguing that his own

opinions of 1974 and 1977, as well as the Fifth Circuit decision

of 1976, had utilized a one year rule. Judge Pointer repeatedly

described the limitations formula in those three opinions as the

"law of the case." (R.E., pp. 124-26). But Judge Pointer

inexplicably failed to note that under that formula, as it was

set forth in all three opinions, the one year period was to be

based, not on the date that the complaint in Swint was filed, but

R.E., p. 127, citing Ingram v. Steven Robert Coro.. 547

F.2d 1260, 1263 (5th Cir. 1977); Buckner v. Goodyear Tire & Rubber Co. 476 F.2d 1287 (5th Cir. 1973).

41

Since the earlieston the date of the earliest EEOC charge.27

EEOC charge was filed in October 1966, the formula of the 1974,

197 6 and 1977 opinions would have resulted in an October 1965

limitations cut-off.

At the time this suit was filed in 1971, and for several

years thereafter, the limitations period for the filing of a

section 1981 charge was tolled by the filing of an EEOC charge.

Boudreaux v. Baton Rouge Marine Contr. Co. . 437 F.2d at 1017 n.

16 (5th Cir. 1971). The tolling rule of Boudreaux was the clear

precedent in this circuit until overturned by Johnson v. Railway

Express Agency. 421 U.S. 454 (1975). There is no rational basis

for suggesting that the defendants might have relied on the one

year portion of the limitations formula in the 1974 opinion while

ignoring the portion of that opinion calculating the one year

period from the date of the first EEOC charge. It was certainly