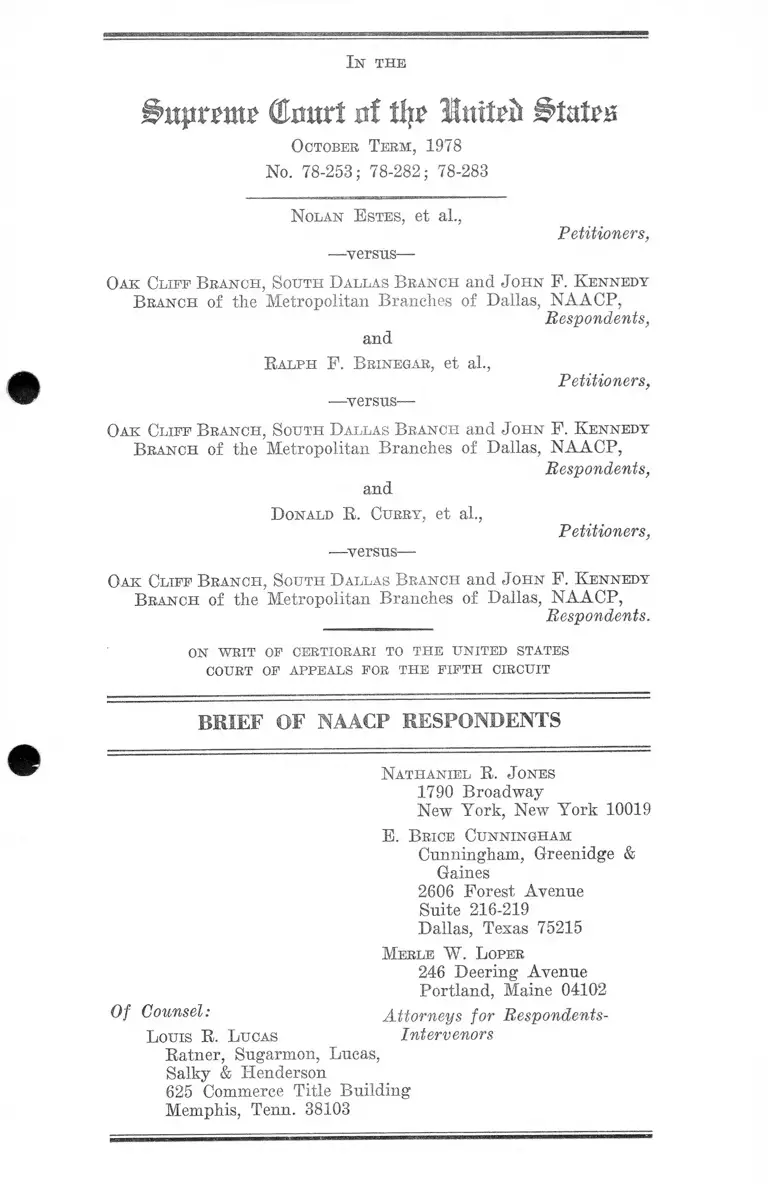

Estes v. Dallas NAACP Brief of NAACP Respondents

Public Court Documents

July 20, 1979

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Estes v. Dallas NAACP Brief of NAACP Respondents, 1979. 989fb717-b19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c3c7cf2d-ab78-4662-8634-df95f566c5b8/estes-v-dallas-naacp-brief-of-naacp-respondents. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

§>uptm$ (tort nf tip Intfrft §>UU&

October T erm , 1978

No. 78-253; 78-282; 78-283

In the

N olan E stes, et al.,

—versus—

Petitioners,

Oak Cliff B ranch , South D allas B ranch and J ohn F. K ennedy

B ranch of the Metropolitan Branches of Dallas, NAACP,

Respondents,

and

R alph F. B einegar, et al.,

■—versus—

Petitioners,

Oa k Cliff B ranch , South D allas B ranch and J ohn F. K ennedy

B ranch of the Metropolitan Branches of Dallas, NAACP,

Respondents,

and

D onald R . Curry, et al.,

—versus—

Petitioners,

Oa k Cliff B ranch , South D allas B ranch and J ohn F. K ennedy

B ranch of the Metropolitan Branches of Dallas, NAACP,

Respondents.

ON WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF OF NAACP RESPONDENTS

N athaniel R. J ones

1790 Broadway

New York, New York 10019

E. B rice Cunningham

Cunningham, Greenidge &

Gaines

2606 Forest Avenue

Suite 216-219

Dallas, Texas 75215

M erle W . L oper

246 Deering Avenue

Portland, Maine 04102

Of Counsel: Attorneys for Respondents-

Louis R. L ucas Intern enors

Ratner, Sugarmon, Lucas,

Salky & Henderson

625 Commerce Title Building

Memphis, Tenn. 38103

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

Questions Presented .......................................................... 2

Summary of Argument .............................................. 2

A bgu m en t

I. The Dallas Desegregation Plan Is Facially Inade

quate to Eliminate Segregated Student Enroll

ments in a School System That Was Segregated

by State Law and That Has Never Yet Been

Brought Into Constitutional Compliance by

Achieving a Non-Baeial, Unitary School System 5

A. The Projected Operation of the District Court’s

Desegregation Plan Shows That It Will Not

Dismantle the Dual System of Baeially Identi

fiable Schools as Bequired by This Court’s

Prior Decisions and to the Extent That the

Plan Itself Shows Is Practical and Feasible in

Dallas ...................................................................... 5

B. Effective Desegregation Techniques Are Avail

able and Bequired in Order to Achieve a Non-

Bacial Unitary System Throughout the DISD 12

1. The Senior High Schools ....... ............... ....... 12

2. The Early Elementary Schools (K-3) ......... 19

3. The East Oak Cliff Sub-District................... 21

II. Proper Principles of Appellate Beview Left the

Court of Appeals No Besponsible Alternative But

to Bemand the District Court’s Plan in Light of

the Large Number of One-Bace Schools and the

Failure to Explain Any Adequate Justification

for Falling So Far Short of the Elimination of

the Segregated Student Enrollment in Most of

the Dallas School System ........................................ 23

11

C. The Dallas Independent School District’s Ra

cially Dual System Was Created by State Law,

Its Patterns of Racially Segregated Enroll

ment Have Never Yet Been Corrected, and a

System-Wide Remedy Is Therefore Constitu

PAGE

tionally Required .................................................. 24

C onclusion- ...................................................................................... 33

T able of A uthorities

Cases:

Bell v. Rippy, 146 F. Supp. 485, 487 (N.D. Tex. 1956)....8, 26

Borders v. Rippy, 247 F.2d 268 (5th Cir. 1957)............... 31

Boson v. Rippy, 285 F.2d 43 (5th Cir. 1960).................... 31

Brown v. Board of Education II, 349 U.S. 294, 300

(1955) .......................................... ...................... .16. 17n.33

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.S. 483 (1954)....... 21

Brown v. Rippy, 233 F.2d 796 (5th Cir. 1956) ....... ....... 31

Columbus Board of Education v. Penick,------ U .S.------- ,

47 U.S.L.W. 4924 (1979) ................................................ 27n

Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S. 1 (1958) ................................. 16

Dayton Board of Education v. Brinkman I, 433 U.S.

406, 409 (1977) ......................................... ...................... 30

Creen v. County School Board, 391 U.S. 430, 442 (1968)

11,17, 23, 28, 33

Keyes v. School District No. 1, 413 U.S. 189 (1973).... . 27n

Mapp v. Board of Education, 525 F.2d 169 (6th Cir.

1975) reh. den. 527 F.2d 1388 cert. den. 427 U.S. 911 17n

Ill

Monroe v. Board of Commissioners, 391 U.S. 450, 459

PAGE

(1968) ............................................................................. 16,20

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537 (1896) ........................ 21

Swann v. Ckarlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education,

402 U.S. 1, 31 (1971) .................................................. 20, 20n

Swann v. Charlotte-M ecklenburg Board of Education,

402 U.S. 1, 26, reh. denied 403 U.S. 912 (1971)....11, 23, 26,

27, 27n, 28, 30, 31, 32, 33

Tasby v. Estes, 572 F.2d 1010, 1012 n. 3 (5th Cir. 1978)

342 F. Supp. 945 (N.D. Tex. 1971) rev’d on other

grounds 517 F.2d 92, 5th Cir. 1975 cert. den. 423 U.S.

939 (1975) ......................................................6n,8,25,28,32

United States v. Jefferson County Board of Education,

372 F.2d 836 (5th Cir. 1966) adopted on reh. en banc,

380 F.2d 385 (5th Cir. 1967) cert. den. 389 U.S, 840 .... 18

United, States v. Jefferson County Board of Education,

372 F.2d 836, 890-891 (5th Cir. 1966) cert. den. 389

U.S. 840 ..................................................................... - ..... 31

United States v. Scotland Neck City Board of Educa

tion, 407 U.S. 484 (1972) 22

I n t h e

dottrl of tl?p HuttPii States

O ctober T erm , 1978

No. 78-253; 78-282; 78-283

N olan E stes, et ah,

— versu s—-

Petitioners,

Oak C liff B r a n c h , S outh D allas B ranch and J ohn F.

K ennedy B ran ch of the Metropolitan Branches of

Dallas, NAACP,

and

Respondents,

R alph F. B rinegar, et al.,

— versu s—

Petitioners,

Oa k C liff B ran ch , S ou th D allas B ran ch and J ohn F .

K ennedy B ran ch of the Metropolitan Branches of

Dallas, NAACP,

and

Respondents,

D onald R. C u rry , et ah,

—versus—

Petitioners,

Oak Cliff B ran ch , S ou th D allas B ranch and J ohn F.

K ennedy B ran ch of the Metropolitan Branches of

Dallas, NAACP,

Respondents.

ON W R IT OF CERTIORARI TO T H E U N IT E D STATES

COURT OF APPEALS FOR T H E F IF T H CIRCU IT

BRIEF OF NAACP RESPONDENTS

Questions Presented

1. Whether a school desegregation plan for a district

that was found to be segregated by state law, and that

has never yet eliminated its racially dual system, is ade

quate when it fails to make any significant effort to de

segregate the student enrollment in its high schools, its

early elementary schools, or any of the schools in a vir

tually all-black sub-district, except through provision for

voluntary transfers and a partial system of magnet-type

schools ?

2. Whether the Court of Appeals properly exercised

its appellate review by remanding the District Court’s

order because it failed to either eliminate or expressly

justify the large number of one-race schools under the

Dallas desegregation plan!

Summary of Argument

I.

The projected operation of the Dallas desegregation

plan implemented under the District Court’s order shows

such a substantial degree of continuing segregation in

student enrollment and such a large number and high

proportion of one-race schools—at least 70 out of 172—

as to make it necessarily inconsistent with the disestab

lishment of Dallas’ previously state-imposed racially dual

system.

The failure of the plan to achieve substantial desegre

gation of the high schools, early elementary schools, or

any of the schools of the East Oak Cliff sub-district is in

sharp contrast to the significant desegregation that is

achieved in grades four through eight in the areas out

2

3

side the all-black East Oak Cliff sub-district. This con

trast highlights the fact that the same desegregation tech

niques that have been effective in grades four through

eight are available as feasible remedies for the state-

imposed segregation in the other grade levels and areas

of the school district in the absence of any findings as to

their infeasibility in specific instances.

The reason for the lack of effective desegregation in

the high schools and the East Oak Cliff area is that the

pattern of initial segregated student assignments is main

tained and the opportunities for desegregation rest solely

on what is basically a transfer policy—majority-to-mi-

nority transfers and transfers to magnet schools. These

techniques in themselves have long been held impermissi

bly inadequate to dismantle the continuing effects of a

dual system of student enrollment. Much the same is true

of the nature of the failure to desegregate the early ele

mentary grades, except that in those grades the magnet-

type schools are not even included as a supplementary

desegregation device.

Desegregation in these aspects of the Dallas school

system has been essentially written off by the District

Court without any sufficient justification and without

focussing specifically enough on particular questions of

the feasibility of using the kinds of techniques approved

in Swann and used with effectiveness in other aspects of

the Dallas plan itself. Rather, the district court assumed

that white students would not attend minority schools, or

in general terms assumed the techniques were not work

able or would interfere with certain educational objec

tives. All of these reasons are either impermissible or

based upon assumptions that were not clearly spelled out

or established.

4

The Dallas system of dual attendance has not yet been

effectively disestablished since the time it was mandated

by state law. The Court of Appeals’ remand is necessary

in order to focus the attention of the school officials on

the remaining task and require them and the District

Court to look more closely at the feasibility of using the

Swann techniques to effectively enforce the constitutional

rights of minority students to attend public schools in a

nonracial, unitary system.

II.

In remanding this case for consideration of a new plan

and for specific findings concerning the infeasibility of

eliminating any remaining substantially one-race schools,

the Court of Appeals was properly insisting on adherence

to the decisions of this Court. This is a proper and im

portant function of the courts of appeals and a part of

the particular tradition of the Court of Appeals for the

Fifth Circuit. To fail to affirm the Court of Appeals in

this case would seriously undermine the function of that

court and its role in our federal judicial system.

Responsible appellate review of the district court order

in this case could have led only to the remand of this plan

in light of the standards previously set by this Court, and

the clear disregard of those standards by the District

Court.

5

ARGUMENT

I.

The Dallas Desegregation Plan Is Facially Inade

quate to Eliminate Segregated Student Enrollments in

a School System That Was Segregated by State Law

and That Has Never Yet Been Brought Into Constitu

tional Compliance by Achieving a Non-Racial, Unitary

School System.

A. The Projected Operation of the District Court’s Desegre

gation Plan Shows That It Will Not Dismantle the Dual

System of Racially Identifiable Schools as Required by

This Court’s Prior Decisions and to the Extent That the

Plan Itself Shows Is Practical and Feasible in Dallas.

The two basic facts that most boldly stand out in this

case are the contrasting degrees to which the District

Court’s desegregation plan both fails and succeeds in de

segregating student enrollment at different levels of the

Dallas school system.

For those grade levels and areas where no real attempt

is made to desegregate the regular attendance area schools

—the high schools, the early elementary schools (K-3), and

the entire all-black East Oak Cliff sub-district—the con

tinuing segregation is stark. Based on the projections at

tached to the District Court’s April 7, 1979 Final Order

(Estes Pet. for Cert. 53a, at 85a-119a) and subsequent mod

ifications (Id. at 121a-129a), over 83 percent (40 out of 48)

of the early elementary schools (K-3),1 and 50 percent (9

1 These figures for the K-3 grade schools necessarily include

only those schools which contain only grades K-3 since those are

the only schools for which racial and ethnic enrollment projections

were furnished under the district, court’s plan. Many K-3 grades

are combined with 4-6 grade intermediate schools, for which racial

and ethnic enrollments are given in grades 4-6, but not in grades

K-3. Since the intermediate schools were .to be largely desegregated

6

out of 18) of the regular attendance area high schools,2 are

one-race or virtually one-race schools whose student bodies

are comprised of approximately 90 percent Anglo or 90

percent minority students.3 Even when the all-black East

Oak Cliff sub-district is omitted from these figures, the

degree of segregation, as measured by the proportion of

one-race schools in the four “ racially proportioned” sub-

districts, is not significantly changed-—82 percent (36 out

of 44) of the separate K-3 schools and 44 percent (7 out

of 16) of the regular attendance area high schools. In the

East Oak Cliff sub-district, all four of the K-3 schools, all

four of the 7-8 middle schools, both of the regular attendance

area high schools, and 15 of the 16 intermediate schools

(grades 4-6)4 were expected to have at least 98 percent mi

under the plan, but the early elementary grades were not, the

figures for the 4-6 grades hear no relationship to the racial compo

sition of the K-3 student body in the same school.

2 These include all the senior high schools of grades 9-12 based

on the projected enrollments in the District Court’s Final Order

which were intended to be the comprehensive high schools for their

respective specified ̂neighborhood attendance areas. Magnet high

schools with specialized programs (for which no reliable racial and

ethnic enrollments were, or could reliably be, given) are not in

cluded. Any integration that might occur in the magnet high

schools themselves would not significantly affect the over-all amount

of high school desegregation achieved, and would itself have no

affect on the racial composition of the regular attendance area high

schools.

3 This definition is the same as that used by the Court of Appeals

in this case, in which it defined a one-race school as “a school that

has a student body with approximately 90% or more of the stu

dents being either Anglo or combined minority races,” but with

an admonition that “ the 90% figure is not a ‘magic level below

which a school [will] no longer he categorized as “one-race.” ’ ”

Tasby v. Estes, 572 F.2d 1010, 1012, n. 3 (5th Cir. 1978). Estes

Pet. for Cert. 132a. In compiling the figures in this Brief, the

actual cut-off point used was 88 percent Anglo or minority.

4 One of the 15 black intermediate schools, Maynard Jackson,

was designated as a Vanguard school with 300 student stations

reserved for integration purposes. According to the DISD’s De

cember 15, 1976 Report to the District Court, the Jackson School

nority enrollment. In fact, all of these East Oak Cliff one-

race schools are at least 89 percent black, and all bnt two

of them are at least 97.5 percent black. Estes Pet. for

Cert. 113a-117a.

By contrast, however, the District Court’s plan did show

the promise of largely eliminating at least the 90 percent

or more Anglo or minority school enrollments in those grade

levels and areas where it tried to do so. Based again on

the projections attached to the District Court’s Final Order

(Estes Pet, for Cert, 85a-llla), none of the middle schools

(grades 7-8) and only two5 of the 66 intermediate schools

(grades 4-6) contain approximately 90 percent or more

minority or Anglo enrollments in those sub-districts aside

from East Oak Cliff.6 These are the grade levels and areas

was 98.8 percent black during the first year of the plan. The most

recent DISD Report to the District Court (April 1979) shows that

Jackson remains as a one-race sehol with 98.3 percent black enroll

ment,

5 The K. B. Polk School in the Northwest sub-district is not

included in these figures as a one-race intermediate school despite

the fact that its projected and actual present status are somewhat

unclear in the Record. In the April 7, 1976 District Court order

Polk was projected to have a totally black enrollment except for

the reservation of 300 student stations for integration under the

Vanguard concept. Estes Pet. for Cert. 86a, The DISD’s April

1979 Report to the District Court indicates a Vanguard enroll

ment of 119 students, of whom 66 percent are Anglo. The Report

also indicates that the total intermediate enrollment (grades 4-6)

is 272. Thus, there appear to be 152 non-Vanguard students in

grades 4-6 at the Polk School, all of whom are minority students.

It thus appears that Polk has a regular intermediate program

that is all-minority and a Vanguard program that is majority

Anglo. The K-3 grades are virtually all-black, as reflected in the

figures of the DISD’s April 1979 Report.

6 Seagoville, the only predominantly Anglo sub-district, is essen

tially omitted from the plan. None of the grade structures for its

four schools are conformed to the standardized grade structures

of the rest of the school district. Racial and ethnic enrollment

comparisons at the standardized grade levels are therefore not

available, and the four Seagoville schools cannot be included in

the above figures.

8

where the plan specifically assigns students for the purpose

of dismantling the segregated student enrollment patterns

that mark schools as “Anglo” or “black” or “Hispanic”—

schools which had remained so marked in Dallas ever since

segregation was initially mandated by the statutes of Texas.

Bell v. Rippy, 146 F.Supp. 485, 487 (N.D. Tex. 1956); Tasby

v. Estes, 342 F.Supp. 945, 947 (N.D. Tex. 1971), revd. on

other grounds, 517 F.2d 92 (5th Cir. 1975), cert. den. 423

TT.S. 939 (1975).

The difference between the failure and the effectiveness

of the plan shows itself in two ways: (1) by comparing the

decreased number of clearly one-race schools in grades 4-8

with the high degree of remaining segregation of the grade

levels immediately above and below them in the very same

districts, and (2) by comparing the almost total segregation

remaining in the East Oak Cliff sub-district, where no sig

nificant desegregation attempt was even made, with the

deceased number of clearly one-race schools in grades 4-8

in those districts where the attempt was made. The dif

ferences are more graphically illustrated in the table on the

next page.

Grades K-3 Grades 9-12

Sub-

Dist.

No. of

Schls.

No. of

1-Race

Schls.

% o f

1-Race

Schls.

No. of

Schls.

No. of

1-Race

Schls.

N.W. 19 16 84% 5 3

s . w . 27 2 100% 4 0

N.E. 13 12 92% 4 2

S.E. 10 6 60% 3 2

Total 44 36 82% 16 7

East

Oak

Cliff 4 4 100% 2 2

Grades 4-6 Grades 7~8

% of

1-Race

Schls.

No. of

Schls.

No. of

1-Race

Schls.

% of

1-Race

Schls.

No. of

Schls.

No. of

1-Race

Schls.

% of

1-Race

Schls.

60% 16 0 0% 5 0 0%

0% 26 1 4% 5 0 0%

50% 15 1 7% 3 0 0%

67% 9 0 0% 3 0 0%

44% 66 2 3% 16 0 0%

100% 16 15 94% 4 4 100%

7 All but two of the K-3 schools in the Southwest sub-district are combined with the 4-6 grades in the same

respective schools, so that the figures for this district are not necessarily representative. Of the 26 schools in

that sub-district, which combine grades K-6, only 2 were 90 percent or more Anglo or minority at the time of

the DISD’s Report to the Court on December 1, 1975. These figures are included in the DISD’s “Answers to

Interrogatories (First Set) of Strom, et al, Intervenors,” which is a part of the Record in this Court as Ex

hibit “M” from the 1975-1976 District Court Hearings.

10

The degree of effectiveness in eliminating 90 percent

Anglo and minority enrollments in grades 4-8 where the

attempt was made, makes the overall number and propor

tion of one-race schools in Dallas even more questionable.

Based on the racial and ethnic enrollment figures that are

given as projections in the District Court’s April 7, 1976

Final Order for those schools for which the statistics are

available, 70 out of 172 schools in the DISD are all or

predominantly one-race schools—41 percent. Of the 53,351

black students who were projected to be enrolled in those

schools, 34,150—64 percent—were projected as enrolled

in schools with approximately 90 percent or more minority

enrollment.

Such statistics on one-race schools cannot, of course, tell

the entire story of a school desegregation plan. The need

to define one-race schools by a cut-off point—90 percent or

88 percent—can itself mask a large number of other

essentially one-race schools that may lie just below the

cut-off point. For example, the four early elementary

schools (K-3) in the Southeast sub-district are all virtually

segregated white schools having between 85 and 87.4 per

cent Anglo student bodies. Estes Pet. for Cert. 99a. If

these were counted as one-race schools, the proportion of

one-race schools for separate K-3 schools in the Southeast

sub-district would be 100 percent rather than 60 percent.

This illustrates the importance of going beyond the one-

race school statistics to examine the actual amount of

desegregation in various school enrollments.

Another problem is the lack of racial or ethnic statistics

for the projected enrollments of those K-3 schools that are

included within a K-6 school. Since the one-race schools in

grades 4-6 have been largely eliminated by student assign

ments under the plan (except for East Oak Cliff), but

similar techniques have not even been attempted for grades

K-3, one would expect that many of the K-3 grades may

11

represent one-raee scliools for those grades even though

included within one school along with the desegregated

intermediate grades (4-6).

This problem can be illustrated by the Reilly School

(K-6) in the Northeast sub-district. This school was at

first designated in the plan as a separate K-3 school with a

92.9 percent Anglo enrollment (Estes Pet. for Cert. 92a).

A later modification of the plan corrected its designation

to that of a K-6 school, showing its enrollment for grades

4-6 as 55.8 percent Anglo and 44.2 percent minority—an

apparently integrated intermediate school. Estes Pet. for

Cert. 123a. It is only because of the initial misdesignation

of the Reilly School as a separate K-3 school that the

Record indicates the one-race nature of the early elemen

tary grades in what otherwise appears to be a desegregated

school. Similar information is not available for the other

K-3 grades where they are included in a full K-6 elemen

tary school.

While all of these statistics cannot tell the full story, they

do point clearly to the fact that the state-mandated patterns

of segregated student enrollment have not yet been dis

mantled. This is particularly true where the failure—in

the high schools and early elementary schools and in the

maintenance of an entire all-black sub-district—lies side-by-

side with a demonstration of the possibility that desegrega

tion can be made effective in the same grade levels and in

the same sub-districts where those failures occurred be

cause the same techniques were never tried.

Dallas clearly has not converted its dual system “to a

system without a ‘white* school and a ‘Negro’ school, but

just schools.” Green v. County School Board, 391 U.S. 430,

442 (1968) ; cf. Swann v. Charlotte-MecMenburg Board of

Education, 402 U.S. 1, 26, reh. denied 403 U.S. 912 (1971).

At the very least, these figures demand the closer scrutiny

12

and justification that the Court of Appeals required in this

case.

B. Effective Desegregation Techniques Are Available and Re

quired in Order to Achieve a Non-Racial Unitary System

Throughout the DISD.

The amount of continuing segregation in the Dallas

school system shows the failure of the plan, as projected,

to eliminate the dual school attendance patterns in the

district. The particular areas of failure under the Dallas

plan are constitutionally inadequate both because they rely

solely upon out-dated desegregation techniques that may

have sufficed at an earlier time as the “ first steps” toward

a desegregated system but are wholly inadequate today,

and because they ignore effective techniques that are

working in neighboring areas of the district or in neighbor

ing grade levels of the Dallas system itself. The early

elementary schools, all of the regular attendance area high

schools, and the East Oak Cliff sub-district have been auto

matically written off. The fear that desegregation will

cause “white flight” and that “white flight” will cause more

segregation is used as an excuse to avoid desegregation in

the first place. Efforts to achieve greater desegregation

may well also be hampered by the fact that the integrative

student assignments that are made are always from black

and Hispanic areas toward Anglo areas, and never the

other way around.

It is little wonder that the Court of Appeals found itself

unable to approve the District Court’s plan in the absence

of specific findings concerning the feasibility of alternative

and more effective means of desegregation.

1. The Senior High Schools.

One of the most difficult things to understand about the

Dallas plan is its failure to carry the intermediate and

middle school desegregation into the high schools. The

13

feasibility of using the elementary school attendance areas

as a basis for assigning students to grades 4-8 to effectively

achieve desegregation is demonstrated by the plan itself.

Yet, for some unexplained reason, students who have been

assigned to integrated schools for the fourth through the

eighth grades are then dropped back into their neighbor

hood high schools, half of which are one-race schools.

Black and Hispanic students, for instance, who make up

the C.F. Carr elementary attendance area in west central

Dallas are assigned to the Burnet School in northern

Dallas for grades 4-6, then farther north to the Walker

School for grades 7-8. Estes Pet. for Cert. 87a, 89. Upon

completion of the eighth grade, however, they return to

their neighborhood Pinkston High School, which has a 95

percent minority enrollment. Estes Pet. for Cert. 90a. It

takes more information than appears on the Record before

this Court to see why it would not be feasible to give these

students an integrated education at Hillcrest or W.T. White

High Schools, both of which have a 96 percent Anglo en

rollment, both of which are within the same general area

and distance range as the schools at which the Carr students

spent grades 4-8, and the first of which appears to have an

enrollment of only 70 percent of its capacity (Pet, for Cert.

90a). Alternatively, there is no apparent reason why

Anglo students in the areas where the Carr students at

tended grades 4-8 could not be brought down to Pinkston

High School for an integrated education with the Carr

students.

This same basic situation occurs time after time under

the present Dallas plan. Minority students are assigned

out of central and west central Dallas to integrated inter

mediate schools and middle schools for grades 4-8, and then

sent back to segregated schools for their last four years.

The following chart traces the progression of students in

14

such situations, showing the racial and ethnic composition

for the K-3 attendance area (measured by the percentage

of minority enrollment) and for each of the schools those

students would attend through their graduation from high

school:

K-3 Sch. & Inter. Sch. & Middle Sch. & High Sch. &

% Minority % Minority % Minority % Minority

Carr 99% Burnet 48% Walker 48% Pinkston 95%

Allen 91% Caillet

Marcus

60%

60%

March 45% Pinkston 95%

Arlington

Park

98% Caillet 60% Rusk 44% N. Dallas 83%

Carver/

Tyler

99%

100%

Foster

Pershing

Walnut H.

51%

60%

41%

Walker 48% Pinkston 95%

Earhart/

Navarro

100%

100%

Longfellow

Williams

54%

58%

Cary

Marsh

48%

45%

Pinkston 95%

Travis 98% Preston

Hollow

59% Spence 77% N. Dallas 83%

Hassell 100% Bayles 46% Gaston 43% Madison 100%

Brown 100% Conner

Truett

44%

47%

Gaston 43% Madison 100%

City Pk. 96% Lakewood 38% Gaston 43% Madison 100%

Colonial 100% Reinhardt 42% Gaston 43% Madison 100%

Frazier 100% Rowe 47% Hood 40% Madison 100%

Wheatley. 100% Sanger 46% Hill 39% Madison 100%

Harris 100% Sanger 46% Hill 39% Madison 100%

Rice 100% Reilly 44% Hill 39% Lincoln 100%

Thompson 100% Ireland

J. Adams

37%

42%

Florence 41% Lincoln 100%

Rhoads 100% San Jacinto 49% Hood 40% Lincoln 100%

Dunbar 100% Hawthorne

Blanton

42%

43%

Florence 41% Madison 100%

Buckner 88% Rylie

Burleson

Dorsey

43%

42%

46%

Comstock 41% Spruce 28%

(The above information is taken from the District Court’s Final Order,

April 7, 1976, and subsequent modifications, as set forth in the Estes

Pet. for Cert., at 85a-105a, 123a-124a, and 127a-129a.)

15

In all of these situations students are assigned to fourth

through eighth grade schools outside their ordinary segre

gated neighborhood attendance areas and substantial de

segregation is achieved. In every case, except for the last

one listed, they are brought back to segregated high schools.

It does not appear that the routes to integrated high schools

would be any longer or less feasible than those already

travelled to intermediate and middle schools. High school

students should be at least as capable of participating in

such a program as students of elementary and junior high

school age. The building capacities seem to be generally

available at the high school level (Estes Pet. for Cert., 90a,

97a, 104a), and even where present building capacities ap

pear to be full, students could be exchanged without causing

over-capacity problems.

The District Court’s only findings to justify the omission

of desegregated student assignments at the high school level

did not go to the feasibility of the transportation involved,

or to any lack of a constitutional requirement to desegregate

them. Rather, the District Court concluded that such assign

ments would not work because Anglos would not go to

minority schools. Estes Pet. for Cert. 34a.

The real reason for avoiding regular high school assign

ments on a non-segregated basis thus appears to be that

white students do not want desegregation, at least if it

means that they must attend schools that minority students

have to attend, in areas where minority students have to go

to school. This approach is constitutionally impermissible.

It allows the constitutional rights of minority students to

be defeated because of speculation about the feelings of

white students. To make these minority rights dependant

upon the cooperation of white students is itself racially

discriminatory. This Court has long held that the vindica

tion of constitutional rights cannot be avoided because of

10

disagreement with those rights. Brown v. Board of Educa

tion II, 349 U.S. 294, 300 (1955); Cooper v. Aaron, 358 U.S.

1 (1958); Monroe v. Board of Commissioners, 391 U.S. 450,

459 (1968).

In Monroe the District Court had approved a desegrega

tion plan that assigned students to schools on an initially

desegregated basis, but allowed them freely to transfer back

to their original segregated schools. The free transfer plan

was defended as necessary to prevent “white flight” and

preserve the public school system. In holding such a plan

invalid as a device that in fact prevented the desegregation

that is required by the Constitution, this Court stated:

[N] o attempt has been made to justify the transfer

provision as a device designed to meet “ legitimate local

problems,” . . . rather it patently operates as a device

to allow resegregation of the races to the extent de

segregation would be achieved by geographically drawn

zones. Respondent’s argument in this Court reveals its

purpose. We are frankly told in the Brief that without

the transfer option it is apprehended that white stu

dents will flee the school system altogether. “ But it

should go without saying that the vitality of these con

stitutional principles cannot be allowed to yield because

of disagreement with them.” Brown II, at 300.

Monroe v. Board of Commissioners, 391 U.S. 450,459 (1968).

The failure of the District Court to require any meaning

ful desegregation in one-half of the regular attendance area

high schools in Dallas is comparable to the Monroe plan

of making initial desegregated assignments and allowing

everyone to transfer back. The difference is that in Dallas

no initial desegregated assignments are made, so there is

no need to transfer back. The essential similarity between

the Monroe and Dallas plans is the purpose—and that pur

17

pose has been held to be impermissible since it forecloses

that possibility of desegregation from the outset.8

The District Court depreciated the importance of inte

grated high school assignments for minority students be

cause of the opportunities to attend magnet schools or to

take advantage of the majority-to-minority transfers. Estes

Pet. for Cert. 35a. The fact of the matter is that the entire

high school desegregation plan rests solely upon the magnet

school concept and majority-to-minority transfers, which

the District Court found to be the more practical and effec

tive way to achieve high school desegregation. Estes Pet.

for Cert. 35a.

In reality, high school desegregation in Dallas is based

on a transfer system, and one that is less exacting and

contains none of the safeguards of the freedom of choice

desegregation devices that became obsolete at the time of

Green v. County School Board, 391 TT.S. 430 (1968). It is

less than the old free choice plans because the initial assign

ments are made by the school system to segregated schools

and students are allowed to transfer out on the basis of

certain criteria—to attend a magnet school for special pro

8 While the District Court purported to recognize that the

Brown II “ disagreement principle” applies to the fear of “white

flight,” and purported not to base its high school plan on find

ings of fact from any of the sociological evidence in this case con

cerning the effects of “forced busing” on white flight” (Estes Pet.

for Cert. 43a, fn. 50), the court’s citation to Mapp v. Board of

Education, 525 F.2d 169 (6th Cir. 1975), reh. den. 527 F.2d 1388,

cert. den. 427 U.S. 911, might suggest otherwise. Whatever might

be said about the Mapp case, the plan in Dallas show's that de

segregation cannot be achieved by avoiding it. The two schools in

Mapp that became segregated because of non-attendance by the

white students who had been assigned there were certainly no

more segregated than the all-black Lincoln, Madison, Roosevelt,

and South Oak Cliff High Schools, or the other one-race high

schools in Dallas whose desegregation has been sacrificed by the

District Court to the unsubstantiated fear of “white flight.”

18

grams of interest to them, or to attend a school where their

racial or ethnic proportion in the student body is less than

in the school system as a whole. Compare United States v.

Jefferson County Board of Education, 372 F.2d 836, 890-891

(5th Cir. 1966), adopted on rehearing en banc, 380 F.2d 385

(5th Cir. 1967), cert, den., 389 U.S. 840.

Nor does the magnet school concept offer any realistic

promise of ever effectively desegregating the high schools

of Dallas, let alone do it now. The magnet schools involve

only a small proportion of the high school population. They

have no effect whatever on bringing integration into the

regular attendance area high schools where the vast major

ity of the student population attends.9 The use of magnet

schools can have excellent educational value. They can play

a role in helping to create and maintain a system of inte

grated student enrollment. But magnet schools, as they

exist in Dallas, cannot begin to do the whole job of desegre

gation all by themselves.

In summary, the high school aspect of the desegregation

plan is essentially a lost opportunity to use methods that

the defendants are using successfully to achieve desegrega

tion in earlier grade levels. It is based apparently on the

assumed reluctance of white students to go to desegregated

9 There may also be some question about the nature of the inte

gration that occurs in a school with a magnet-type program. As

pointed out in footnote 5, the April 1979 DISD Report to the

District Court concerning enrollment in the Polk Intermediate

Vanguard School (grades 4-6), shows that there are 152 regular

program students and 119 Vanguard program students. The regu

lar program students are all minority, while the Vanguard pro

gram is substantially integrated. While the exact nature of the

operation of this program is not clear on the Record before this

Court, it appears that the magnet-type programs may not actually

integrate the school generally, but only the particular magnet

program that exists within the school. To the extent that this is

true in the magnet-type programs, the desegregating effectiveness

of such programs is further reduced.

19

schools. It operates as an inadequate freedom of choice

plan with no real prospect of significantly desegregating

the high school student enrollment system generally. It is

hard to see how the Court of Appeals could have done other

than reject it in the absence of specific consideration and

findings that the more effective desegregation devices that

are apparently available are not feasible.

2. The Early Elementary Schools (K -3).

The major reasons given by the District Court for leav

ing the segregated enrollment untouched in the early

elementary grades were the lesser ability of young children

to deal with the problems of transportation, the special

programs in the minority areas that were presumed to

result in higher quality education for minority students

there, and the opportunity to use the diagnostic-prescrip

tive concept in the early childhood learning centers with

parental involvement. On this basis, the District Court

provided for attendance in grades K-3 in the local area

around each such elementary school, modified only by the

opportunity for majority-to-minority transfers. Estes Pet.

for Cert. 32a-33a, 5Ia-55a.

The result is a highly segregated pattern of early elemen

tary school enrollments. As shown by the chart on page

9, supra, 36 of the 44 separate K-3 centers (82%) are

one-race schools even when only the four “ racially propor

tioned” sub-districts are considered—-that is, not including

the all-black East Oak Cliff sub-district, or the Seagoville

sub-district in which no separate K-3 centers exist.. Indeed,

in three of the sub-districts10 almost all of the separate

early elementary schools are of one race—16 out of 19 in

10 The figures for the Southwest sub-district are less conclusive

because only two separate K-3 schools exist there. That sub-district

is also one of the more integrated areas of Dallas.

20

the Northwest, 12 out of 13 in the Northeast, and at least 6

out of 10 in the Southeast.

While the age of students is one of the important factors

in determining the feasible limits on the time and distance

of travelling to school, Swann v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg

Board of Education, 402 U.S. 1, 31 (1971), it was not

intended to be a reason for precluding such transportation

altogether when that is necessary to desegregate a school

system. Surely, the value of an integrated education is a

factor that also must weigh heavily in the balance of

“ legitimate local problems,” Monroe v. Board of Commis

sioners, 391 U.S. 450, 459 (1968). Yet, the District Court

merely cited the age of such students generally as an excuse

for totally avoiding desegregation of these crucial grade

levels.

The court made no findings of fact that would show the

infeasibility of some meaningful degree of school pairing.

Nor did it consider the possibility of transportation dis

tances that might be well within the ability of younger

children to deal with. Much more careful and individualized

consideration of these factors should be required in light

of the everyday busing of large numbers of such children

throughout our country. It would no doubt come as a

surprise to the millions of parents in both urban and rural

areas to learn that their young children are being harmed

by being transported to consolidated elementary schools

or special schools miles from their homes for purposes

unrelated to desegregation.11 Indeed, the objection was not

,11 “Bus transportation has been an integral part of the public

education system for years, and was perhaps the single most im

portant factor in the transition from the one-room sehoolhouse to

the consolidated school. Eighteen million of the Nation’s public

school children, approximately 39%, were transported to their

schools by bus in 1969-1970 in all parts of the country.” Swann v.

Charlotte-Mecklenbnrg Board of Education, 402 U.S. 1, 29 (1971).

21

raised in earlier times when both white and black children

of all ages were being bused for long times and great

distances, often past schools of the opposite race, in order

to keep them apart. Clearly, considerations of young age

in determining how far a child should travel to school

cannot legitimately be used to preclude all serious con

sideration of any desegregating school assignment at all.

Likewise there is no finding that the educational concepts

and programs that are desired in these early years could

not be carried out as well under a system of integration.

As to the District Court’s reliance on special programs for

a higher quality of education, it should go without saying

that such programs are not sufficient substitutes for

eliminating dual systems of student enrollment. This has

been true ever since Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U.8.

483 (1954), overruled Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U.S. 537

(1896).

The complete writing-off of desegregation in the early

elementary schools is further illustrated by the fact that the

magnet-type school concepts that are used in the Vanguard,

Academy and magnet-schools in the other grade levels of

Dallas apparently play no real part as a supplementary

tool to desegregate grades K-3.

3. The East Oak Cliff Sub-District.

The District Court’s treatment of the virtually all-black

East Oak Cliff sub-district is similar to its treatment of

the high school grade levels: it created an aspect of the

system that remains initially highly segregated and then

relied solely on a transfer system—to magnet schools or

by majority-to-minority transfers—as the only means of

achieving any desegregation. This approach is constitution

ally inadequate in East Oak Cliff for the same reasons that

it is inadequate in the high school levels generally.

Because of the heavy concentration of black population

within East Oak Cliff, there may well be greater difficulties

in substantially desegregating that area than exist in other

geographical areas of the city. The fact does not, however,

justify writing off the entire district without more strictly

scrutinizing the possibilities for achieving desegregation

through regular student assignments to integrated schools,

complemented by the other appropriate special education

programs and magnet schools contained in the plan.

What the District Court’s plan essentially does is draw

a line around an entire area and hold that no attempt will

even be made to change the racial make-up of the enroll

ments there except through the voluntary transfer devices.

As a result, no significant desegregation in any of the reg

ular attendance area schools was projected at the time of

the plan’s adoption, or is likely to be achieved under a con

tinuation of the present plan.

While there is nothing inherently improper about using

the sub-district approach to an urban desegregation plan,

that approach should not be allowed to create an all-black

district in a way that prevents the use of all parts of the

system in a plan of desegregating the whole district. See

United States v. Scotland Neck City Board of Education,

407 U.S. 484 (1972). Plans were submitted to the District

Court by the plaintiffs and the plaintiff-intervenors that

would have brought significant desegregation to the schools

within the East Oak Cliff area. Yet, the District Court

seemed merely to draw a line around the problem and write

it out of the system except for magnet schools, quality edu

cation programs, and transfers.

At the very least, the failure to do more to desegregate

a major all-black section of Dallas requires a fuller explana

tion with findings of fact focussed on the particular prob

lems that might be involved, rather than assuming too easily

that nothing could he done. That is what the Court of

Appeals would require.

23

II.

Proper Principles of Appellate Review Left the Court

of Appeals No Responsible Alternative But to Remand

the District Court’s Plan in Light of the Large Number

of One-Race Schools and the Failure to Explain Any

Adequate Justification for Falling So Far Short of the

Elimination of the Segregated Student Enrollment in

Most of the Dallas School System.

The Court of Appeals was faced with the review of a

desegregation plan whose goal must be “ to convert to a

unitary system in which racial discrimination would be

eliminated root and branch.” Green v. County School Board,

391 U.S. 430, 437-438 (1968). Full compliance with this

constitutional mandate, and thus the standards of any judi

cially ordered remedy, requires “ a system without a ‘white’

school and a ‘Negro’ school, but just schools.” Green, at 442.

In speaking to the requirements of a desegregation plan

for a large, urban school system that had been segregated

under state law, this Court in Swann v. Charlotte-Mechlen-

burg Board of Education, 402 U.S. 1, reh, den., 403 U.S.

912 (1971), applied these one-race-school principles to sys

tems such as Dallas. Recognizing that “ the existence of some

small number of one-race, or virtually one-race, schools

within a district is not in and of itself the mark of a

system that still practices segregation by law,” the Court

explicitly placed on the school districts, and on the district

courts reviewing the adequacy of remedial plans, the obliga

tion to “make every effort to achieve the greatest possible

degree of actual desegregation and . . . thus necessarily be

concerned with the elimination of one-race schools.” Swann,

at 26.

For purposes of district court review of school board

proposals, and thus necessarily for purposes of proper re-

24

view of district court orders by the courts of appeal, the

burden of justification of remaining one-race schools was

placed upon the school boards:

No per se rule can adequately embrace all the difficulties

of reconciling the competing interests involved; but in

a system with a history of segregation the need for

remedial criteria of sufficient specificity to assure a

school authority’s compliance with its constitutional

duty warrants a presumption against schools that are

substantially disproportionate in their racial composi

tion. Where the school authority’s proposed plan for

conversion from a dual to a unitary system contem

plates the continued existence of some schools that are

all or predominantly of one race, they have the burden

of showing that such school assignments are genuinely

nondiscriminatory. The court should scrutinize such

schools, and the burden upon the school authorities will

be to satisfy the court that their racial composition is

not the result of present or past discriminatory action

on their part.

Id. All of these strictures concerning one-race schools were

made specifically in the context of an urban school system,

like Dallas, with significant concentrations of residential

segregation.

C. The Dallas Independent School District’s Racially Dual Sys

tem Was Created by State Law, Its Patterns of Racially

Segregated Enrollment Have Never Yet Been Corrected,

and a System-Wide Remedy Is Therefore Constitutionally

Required.

There is no doubt that the District Court in this case has

found that the dual system of Dallas is uneorreeted, and

is system-wide. As the District Court stated when this case

was originally brought:

25

When it appears as it clearly does from the evidence

in this case that in the Dallas Independent School Dis

trict 70 schools are 90% or more white (Anglo), 40

schools are 90% or more black, and 49 schools with 90%

or more minority, 91% of black students in 90% or

more of the minority schools, 3% of the black students

attend schools in which the majority is white or Anglo,

it would be less than honest for me to say or to hold

that all vestiges of a dual system have been eliminated

in the Dallas Independent School District, and I find

and hold that elements of a dual system still remain.

Tasby v. Estes, 342 F. Supp. 945, 947 (N.D. Tex. 1971),

revd. on other grounds, 517 F.2d 92 (5th Cir. 1975), cert,

den. 423 U.S. 939 (1975).

The District Court went on to refer to the required rem

edies for the various aspects of a dual system, such as

faculty and staff desegregation, majority-to-minority trans

fer policies, the use of transportation, school construction

and site selection, and noted:

The Dallas School Board has failed to implement any

of these tools or to even suggest that it would consider

such plans until long after the filing of this suit and

in part after the commencement of this trial.

Tasby v. Estes, supra, 342 F. Supp. at 948.

Many of these desegregation tools have since been imple

mented in Dallas under the compulsion of court order. In

the area of student enrollment, however, no adequate plan

has ever yet been ultimately approved or held by the Dis

trict Court or by the Court of Appeals to have successfully

brought the school system into constitutional compliance

in that aspect of its operation. The statistics of student

enrollment revealed by this record and projected under the

26

District Court’s plan show how extensive and widespread

the segregation continues to be.

This case involves a large, urban school system in the

South— one in which segregation existed in every aspect

of its system under the mandate of state statutes. Bell v.

Rippy, 146 F. Supp. 485, 487 (N.D. Tex. 1956). As such,

it is on all fours with the school district involved in Swann

v. Charlotte-Mecklenburg Board of Education, 402 U.S. 1

(1971), where the Chief Justice, speaking for the Court,

stated, “The objective today remains to eliminate from the

public schools all vestiges of state-imposed segregation.”

Id. at 15.

While cautioning that the basis for any judicial remedy

is the unconstitutional dual system itself, this Court in

Swann made clear that the use of racial school enrollment

statistics was relevant to determining whether a plan was

effectively dismantling a dual attendance system in the con

text of geographical attendance zones. Swann made it clear

that the use of pairing and transportation of students to

schools outside their areas of residence was an appropriate

and sometimes necessary tool for eliminating racial atten

dance patterns, even though, “more often than not, these

zones are neither compact nor contiguous; indeed they may

be on opposite ends of the city.” Id. at 27. It is clear that

this Court in Swann contemplated a. complete wiping out,

to the extent feasible, of the segregated attendance patterns

that accompanied a school system whose segregation had

been state imposed.

All things being equal, with no history of discrimina

tion, it might well be desirable to assign pupils to

schools nearest their homes. But all things are- not

equal in a system that has been deliberately constructed

and maintained to enforce segregation. The remedy

27

for such segregation may be administratively awkward,

inconvenient, and even bizarre in some situations and

may impose burdens on some; but all awkwardness and

inconvenience cannot be avoided in the interim period

when remedial adjustments are being made to eliminate

the dual school systems.

Id. at 28.

Swann did not impose a requirement for maintaining

racial balance in the schools once their segregated atten

dance patterns have been fully corrected, but it does require

their full correction. The full remedy clearly has never

occurred in Dallas.

There is no inconsistency between the requirement of full

elimination o f segregated attendance in a system with state-

imposed segregation, and the principle that the remedy must

be directed to the constitutional wrong.12 While the rem

edies of Swann may not be invoked to achieve objectives

other than correcting the violation, the Court there recog

nized the problem of sorting out the entangled web of inter

related causes and effects of school and residential segrega

tion. As the Court stated:

People gravitate toward school facilities, just as schools

are located in response to the needs of people. The

location of schools may thus influence the patterns of

residential development of a metropolitan area and

have important impact on composition of inner-city

neighborhoods.

Id. at 20-21.

12 Indeed, this Court has now made clear that the remedies of

Swann apply as well to systems where the poliey of segregation

was not statutorily imposed and where the public school officials

have not shown that the segregation was not caused by the uncon

stitutional policies and acts. Columbus Board of Education v.

Permit,------ U .S .------- , 47 U.S.L.W. 4924 (1979); Keyes v. School

District No. 1, 413 U.S. 189 (1973).

28

We do know, as the Court pointed out, that decades of

existence under a system of state-mandated school segrega

tion keeps all other things from being equal. The school

segregation in Dallas today exists as an extension of a state-

imposed discriminatory system that has never been fully

remedied. It would not be logical or fair to deprive the

plaintiffs of a full remedy in this case just because the

school board’s failure to more promptly begin to devise

remedies to deal with segregation in all of the various

aspects of the system now raises doubts about which kind

of segregation caused the other. To the extent that we can

not know just what segregation would or would not exist

today but for the decades of state-imposed school segrega

tion, we must assure a full remedy for those who have been

constitutionally deprived. Swann and the other decisions of

this Court require no less.

In the light of this specific language, the Court of Appeals

in this case was faced with a plan that left at least 70 one-

race schools—not just “ some” or “ some small number” as

referred to in Swann, The nature of the plan itself raises

numerous questions as to why many of these schools could

not be integrated as easily as some of the others that had

been, as described in earlier parts of this brief. The Court

of Appeals had three years earlier directed the District

Court to “ immediately take the necessary steps, using and

adapting the techniques discussed in Swann,” and stressed

to that court that, “ It is imperative that the dual school

structure of the DI8D be completely dismantled by the

second semester of the 1975-76 academic year.” Tasby v.

Estes, 517 F.2d 92, 110 (5th Cir. 1975), cert. den. 423 IT.8.

939.

It is hard to see how the Court of Appeals could have

come down with a more moderate decision given the con

trast between this Court’s mandates in Green and Swann

29

and the projected operation of the District Court approved

plan for Dallas. The Court of Appeals stated the dilemma

of reviewing such a plan:

We cannot properly review any student assignment

plan that leaves many schools in a system one race

without specific findings by the district court as to the

feasibility of these techniques. * * * There are no ade

quate time-and-distance studies in the record in this

case. Consequently, we have no means, of determining

whether the natural boundaries and traffic considera

tions preclude either the pairing and clustering of

schools or the use of transportation to eliminate the

large number of one-race schools still existing.

Estes Pet. for Cert. 137a.

The Court of Appeals did not preclude the eventual jus

tification of one-race schools if the findings, supported by

the record, would show the infeasibility of desegregating

them:

The district court is again directed to evaluate the

feasibility of adopting the Swann desegregation tools

for these schools and to reevaluate the effectiveness of

the magnet school concept. I f the district court deter

mines that the utilization of pairing, clustering, or the

other desegregation tools is not practicable in the

DISD, then the district court must make specific find

ings to that effect.

Estes Pet. for Cert. 138a. Nor was the Court of Appeals

unduly interfering with the District Court’s discretion, or

substituting its own findings of fact for those of the District

Court. In the same decision, the Court of Appeals deferred

to that discretion and upheld the District Court’s dismissal

of the separate Highland Park Independent School District

30

as a defendant (Estes Pet. for Cert. 139a-141a) and its

approval of the school board’s selection of a challenged

school site (Estes Pet. for Cert. 141a-145). The Court of

Appeals further recognized that special considerations as

to feasibility may apply to school districts made up pre

dominantly of racial or ethnic minorities. Estes Pet. for

Cert. 134a.

But when it came to the student assignment portion of

the Dallas plan, the only alternative to the Court of Ap

peals’ remand would have been the approval of a plan that

left at least 70 one-race schools and, without adequate ex

planation, neglected to use apparently available desegrega

tion techniques in several significant levels and areas of

the Dallas school system.

Where school boards are under an obligation to come up

with effective plans, and district courts are under an obliga

tion to review those plans with an eye to effective enforce

ment of constitutional rights, courts of appeals necessarily

have an obligation to review the district court decisions in

a meaningful way. Without more information in the form

of factual findings, there was no responsible way for the

Court of Appeals in this case to approve a plan that is so

woefully inadequate on its face “ to achieve the greatest

possible degree of actual desegregation” and be “ concerned

with the elimination of one-race schools.” Swann, supra,

402 U.S. at 26.

The importance of the “ proper allocation of functions

between the district courts and the courts of appeals” in

school desegregation cases has been noted by this Court.

Dayton Board of Education v. Brinkman I, 433 U.S. 406,

409 (1977). Just as important as the deference due the

district courts as triers of fact is the recognition of the

function of the courts of appeals in these matters. The

31

entire history of the Fifth Circuit’s school desegregation

litigation is itself a dramatic illustration of that importance.

Time after time, reluctant district court judges have been

held to the standards enunciated by this court only because

of the dogged insistence of the Court of Appeals. The chain

of cases developing the standards for school desegregation

plans ultimately led to the Fifth Circuit’s formulation of

its model freedom of choice decree in United States v. Jeffer

son County Board of Education, 372 F.2d 836 (5th Cir.

1966), adopted on reh. en banc, 380 F.2d 385 (5th Cir. 1967),

cert. den. 389 TT.S. 840—a model decree born of its painful

and frustrating experience in reviewing district court de

segregation orders.

This case itself furnishes an illustration of the role of

the court of appeals in requiring district court enforcement

of desegregation. In the original case involving the desegre

gation of the Dallas schools, the court of appeals reversed

a district court order dismissing the suit as premature.

Brown v. Rippy, 233 F.2d 796 (5th Cir. 1956). The next

year the court of appeals had to reverse the distinct court’s

second dismissal of the case, this time for failure to exhaust

administrative remedies. Borders v. Rippy, 247 F.2d 268

(5th Cir. 1957). The district court was subsequently re

versed again for approving a plan that would have allowed

parents to choose whether to enroll their children in a

segregated or an integrated school. Boson v. Rippy, 285

F.2d 43 (5th Cir. 1960). All of these cases, and others,

involved district court orders by a judge who preceded

the district court judge who is currently handling the Dallas

school case.

The present district court judge, however, has also dem

onstrated a reluctance to take this Court’s admonitions

in Swann seriously. The first plan entered in the present

case was largely based upon the district court’s reluctance

32

to require the transportation of students. It sought to

achieve desegregation through television—a cable television

arrangement whereby white and black classrooms would he

able to communicate with each other on a two-way audio

visual hook-up. In directing the Dallas school officials in

1971 to formulate a plan for achieving a unitary school

system, the judge who is presently handling this , case ex

plained :

Now all of this is not as grim as it sounds. I am

opposed to and do not believe in massive cross-town

bussing of students for the sole purpose of mixing

bodies. I doubt that there is a Federal Judge any

where that would advocate that type of integration as

distinguished from desegregation. There are many

many other tools at the command of the School Board

and I would direct their attention to part of one of

the plans suggested by TEDTAC which proposed the

use of television in the elmentary grades and the

transfer of classes on occasion by bus during school

hours in order to enable the different ethnic groups

to communicate. How better could lines of communica

tion be established than by saying, “ I saw you on TV

yesterday,” and, besides that, television is much

cheaper than bussing and a lot faster and safer. This

is in no sense a Court order but is merely something

that the Board might consider.

Tasby v. Estes, 342 F. Supp. 945 (N.D. Tex. 1971). The

school board based much of their plan at that time on the

district court’s suggestion, and thus occasioned the first

reversal of a plan in the present litigation. Tasby v. Estes,

517 F.2d 92 (5th Cir. 1975). It is this same reluctance to

take Swann seriously that the Court of Appeals is dealing

with in its present remand.

33

The essential effect of the Court of Appeals decision in

this case is to require district courts to give -serious and

specifically-focussed consideration to the feasibility of

eliminating one-race schools and achieving the greatest

possible degree of actual desegregation necessary to dis

mantle racially created enrollment patterns as required

by Swann and by use of the devices that Swann deals with.

In one sense it is an exercise of the appellate role that

complements the role of the trial court by calling upon it to

meet its function as trier of fact in a responsible manner.

This is the kind of guidance and insistence on effective

enforcement of constitutional rights and obligations, as

set forth by this Court, that characterizes the tradition of

the Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit in this long and

painful line of cases. At the very least, this moderate

order of the Court of Appeals should be affirmed to allow

reconsideration of the Dallas plan in this context. To do

otherwise would be to undermine important principles of

responsible appellate review and harm the ability of the

courts of appeal to carry out their important function in

our federal judicial system.

CONCLUSION

The decision of the Court of Appeals should be affirmed.

It is particularly important to indicate once again this

Court’s adherence to the principles of Brown I and II,

Green and Swann upon which the Court of Appeals is here

insisting.

Beyond the affirmance of that decision, this Court should

make clear that those principles, as applied to the Dallas

Independent School District, require greater efforts and

results in eliminating segregated school attendance pat

terns, and use of the Swann techniques in the absence of

34

“ legitimate local problems” that in fact make those

techniques infeasible or inapplicable in particular instances

in the Dallas school desegregation process,

N a t h a n ie l R. J ones

1790 Broadway

New York, New York 10019

E. B hice C u n n in g h a m

Cunningham, Greenidge &

Gaines

2606 Forest Avenue

Suite 216-219

Dallas, Texas 75215

M erle W . L oper

246 Deering Avenue

Portland, Maine 04102

Attorneys for Respondents-

Intervenors

Of Counsel:

Louis R. L ucas

Ratner, Sugarmon, Lucas,

Salky & Henderson

625 Commerce Title Building

Memphis, Tenn. 38103

Certificate of Service

I, Nathaniel E. Jones, one of the counsel for the Respon

dents, certify that a copy of the foregoing Brief was

served upon the following counsel of record by regular mail

by postage prepaid, this 20th day of July, 1979.

Nathaniel R, Jones

M r. E dw ard B. C l o u t m a n , III

8204 Elmbrook Drive, Suite 200

P.O. Box 47972

Dallas, Texas 75247

Mr . M a r k M a r t in

1200 One Main Place

Dallas, Texas 75250

Ms. V il m a S. M a r t in e z

Mexican-American Legal Defense

and Educational Fund

28 Geary Street

San Francisco, Calif. 94108

Mr. L ee H olt, City Attorney

New City Hall

Dallas, Texas 75201

M r . J o h n B r y a n t

8035 East R.L. Thornton

Dallas, Texas 75228

M r . J a m e s G. V e t t e r , J r.

555 Griffin Square Building-

Suite 920

Dallas, Texas 75202

Mr . T h o r n t o n E. A s h t o n , III

Dallas Legal Services

Foundation, Inc.

912 Commerce Street—Room 202

Dallas, Texas 75202

Mr. R obert H. M ow , J r.

Mr. R obert L. B lttm en th al

3000 One Main Place

Dallas, Texas 75250

Mr. J am es A. D onoh oe

1700 Republic National Bank

Building

Dallas, Texas 75201

Mr. M a r t in F rost

777 South R.L. Thornton

Freeway—Suite 120

Dallas, Texas 75203

M r . J am e s T. M a x w e l l

4440 Sigma Road— Suite 112

Dallas, Texas 75240

M r . W arren W h it h a m

412 Adolphus Tower

Dallas, Texas 75202

MEUEN PRESS INC. — N. Y. C 219