Presley v. Etowah County Commission Brief of the Appellee

Public Court Documents

August 30, 1991

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Presley v. Etowah County Commission Brief of the Appellee, 1991. 18642c7b-c19a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c4342a73-f4b8-4942-8fc7-826f481dbfd3/presley-v-etowah-county-commission-brief-of-the-appellee. Accessed February 24, 2026.

Copied!

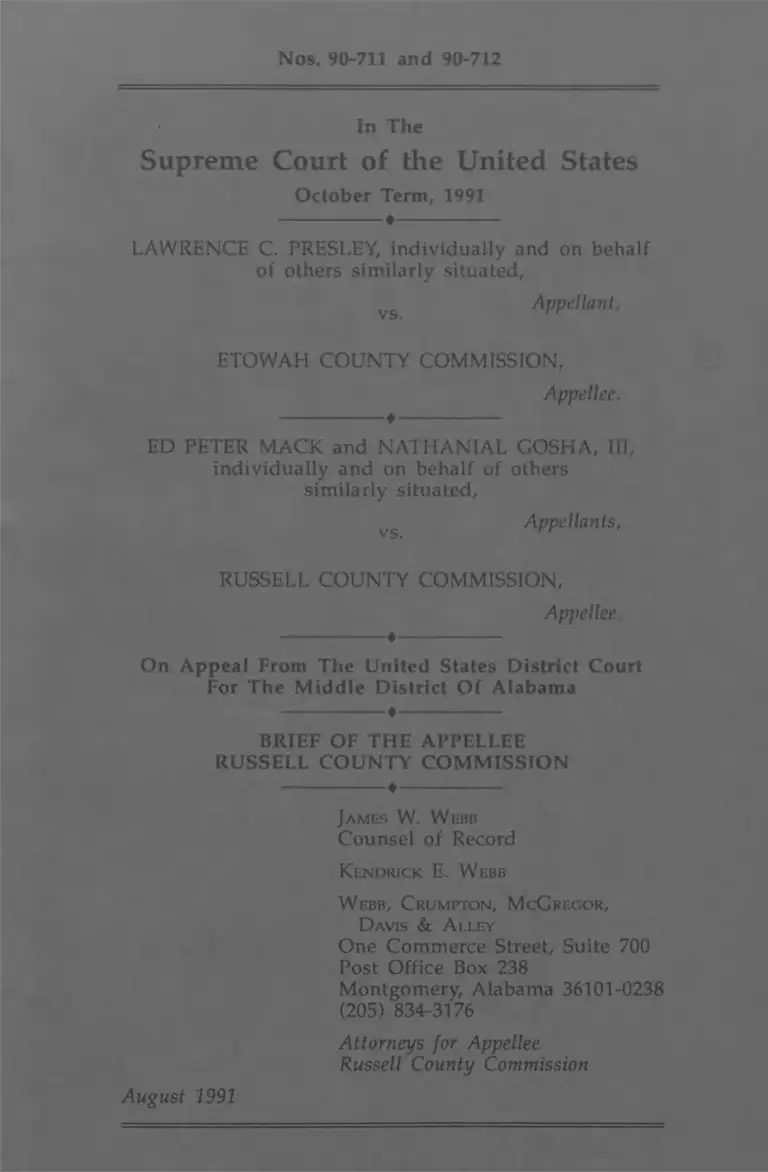

Nos. 90-711 and 90-712

In The

Supreme Court of the United States

October Term, 1991

----------------♦----------------

LAWRENCE C. PRESLEY, individually and on behalf

of others similarly situated,

Appellant,

ETOWAH COUNTY COMMISSION,

Appellee.

----------------- ♦ ------------------

ED PETER MACK and NATHANIAL GOSHA, III,

individually and on behalf of others

similarly situated,

vs Appellants,

RUSSELL COUNTY COMMISSION,

Appellee.

----------------- ♦ ------------------

On Appeal From The United States District Court

For The Middle District Of Alabama

----------------- ♦ ------------------

BRIEF OF THE APPELLEE

RUSSELL COUNTY COMMISSION

----------------- ♦ ------------------

James W. W ebb

Counsel of Record

K endrick E. W ebb

W ebb, C rumpton, McG regor,

Davis & A lley

One Commerce Street, Suite 700

Post Office Box 238

Montgomery, Alabama 36101-0238

(205) 834-3176

Attorneys for Appellee

Russell County Commission

August 1991

1

QUESTION PRESENTED

WHETHER LOCAL LEGISLATION WHICH MERELY

SHIFTS MINISTERIAL ROAD DUTIES FROM INDIVID

UAL COUNTY COMMISSIONERS ELECTED AT LARGE

TO A ROAD ENGINEER RESPONSIBLE TO THE

COUNTY COMMISSION AS A WHOLE IS SUBJECT TO

PRECLEARANCE UNDER SECTION 5 OF THE VOTING

RIGHTS ACT?

11

PARTIES IN COURT BELOW

The parties in the court below at the time of the

judgment were plaintiffs Ed Peter Mack, Nathaniel

Gosha, III, Lawrence C. Presley, and defendants Russell

County Commission and Etowah County Commission.

Ill

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Question Presented............................................................... i

Parties in Court B elow ....................................................... ii

Table of C ontents................................................................. iii

Table of A uthorities............................................................. vi

Opinions B elow ..................................................................... 1

Jurisdiction............................................................................... 1

Statutory Provisions............................................................. 1

Statement of the C a se ......................................................... 1

Summary of Argum ent....................................................... 5

Argument................................................................................. 8

LOCAL LEGISLATION WHICH MERELY SHIFTS

MINISTERIAL ROAD DUTIES FROM INDIVID

UAL COUNTY COMMISSIONERS ELECTED AT-

LARGE TO A ROAD ENGINEER RESPONSIBLE

TO THE COUNTY COMMISSION AS A WHOLE

DOES NOT CONSTITUTE A "CHANGE" WITHIN

THE MEANING OF SECTION 5 OF THE VOTING

RIGHTS ACT AND IS, THEREFORE, NOT SUB

JECT TO PRECLEARANCE.......................................... 8

A. The three-judge court correctly found that

minor reallocations of local governmental

powers among elected officials where there is

no change in constituencies fall outside the

purview of Section 5's preclearance require

ments because there exists no potential for

discrimination............................................................. 8

IV

1. The District Court's ruling is not inconsis

tent with prior Supreme Court cases defin

ing the scope of § 5 coverage.................... 9

2. The District Court's ruling is consistent

with previous district court decisions

which emphasize the presence of a change

in constituencies as being evidence of

potential for discrimination............................ 12

3. The District Court's ruling is consistent

with prior positions held by the Justice

Department emphasizing change in con

stituencies as indicative of potential for

discrimination....................................................... 16

B. The County Commission by state law has

always held general supervisory authority over

the county road system and therefore, the dele

gation of "ministerial" road and bridge duties

to an appointed county road engineer does not

effect a "change" within the meaning of Sec

tion 5 ............................................................................. 17

1. Under Alabama law the county commis

sion acting as a unit has always been

vested with general supervisory authority

over the county's road system with the

power to delegate administrative or minis

terial duties to subordinates.......................... 18

2. The delegation of administrative or minis

terial duties comes within the "administra

tive or ministerial exception" implicit in

section 5 coverage decisions.......................... 21

TABLE OF CONTENTS - Continued

Page

V

C. The Voting Rights Act was "aimed" at voter

registration and was never intended to intro

duce the heavy hand of federal scrutiny into

routine local enactments which have no appar

ent nor real impact upon minority voting

righ ts............................................................................. 23

D. Russell County's 1979 enactments not only

lack a "potential for discrimination", as found

by the three-judge panel; in reality, the conver

sion to the unitary road system actually brings

the most benefit to Russell County's black con

stituents........................................................................ 28

E. The three-judge panel, while according the def

erence due to the Justice Department's posi

tion, properly and prudently chose to override

the Justice Department's position and rule in

the favor of the Russell County Commission 30

TABLE OF CONTENTS - Continued

Page

Conclusion............................................................................... 31

Appendix................................................................................. A-l

VI

C ases:

Allen v. State Board of Elections, 393 U.S. 544 (1969)

...............................................................................10, 12, 24, 25

Beer v. United States, 425 U.S. 130 (1976)...................... 28

County Council of Sumter County, South Carolina v.

United States, 555 F.Supp. 694 (D.C. D.C. 1983)___14

Court of Commissioners of Pike County v. Johnson,

229 Ala. 417, 157 So. 481 (1934)............................ 18, 19

Dougherty County Board of Education v. White, 439

U.S. 32 (1978).................................................................11, 25

Fairley v. Patterson, 393 U.S. 544 (1969).................... 16, 17

Georgia v. United States, 411 U.S. 526 (1973).......... 10, 29

Hadnott v. Amos, 394 U.S. 358 (1969)........................ 11, 25

Hardy v. Wallace, 603 F.Supp. 174 (N.D. Ala. 1985) passim

Horry County v. United States, 449 F.Supp. 990,

(D.C. D.C. 1978)..................................................... 12, 14, 15

Lucas v. Townsend, 698 F.Supp. 909 (M.D. Ga. 1988)___30

McCain v. Lybrand, 465 U.S. 236 (1984)...................... 9, 21

McDaniel v. Sanchez, 452 U.S. 130 (1981)........................ 11

Morris v. Gressette, 432 U.S. 491 (1977).......................... 23

NAACP v. Hampton County Election Comm., 470

U.S. 166 (1985)...............................................................21, 22

Perkins v. Matthews, 400 U.S. 379 (1971)

...................................................................6, 11, 12, 16, 24, 25

Pleasant Grove v. United States, 479 U.S. 462 (1987)___11

TABLE OF AUTHORITIES

Page

Richmond v. United States, 422 U.S. 358 (1975)............ 11

Robinson v. Alabama State Board of Education, 652

F.Supp. 484 (M.D. Ala. 1987).................... 13, 14, 15, 22

St. Louis v. Praprotnick, 485 U.S. 112 (1988).................. 18

South Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383 U.S. 301 (1966)........ 25

Sumbry v. Russell County, CV-84-T-1386-E (M.D.

Ala. 1986)...................................................................................4

Thompson v. Chilton County, 236 Ala. 142, 181 So.

701 (1938)........................................................................ 19, 20

Turner v. Webster, 637 F.Supp. 1089 (N.D. Ala.

1986)......................................................................................... 28

Statutes:

Act No. 79-652, Acts of Alabama 1979.................................. 4

Alabama Code, 1975, § 11-6-1 (Michie 1989 Repl.

V o l.)........................................................................... r ............. 3

Alabama Code, 1975, § 11-6-3 (Michie 1989 Repl.

V o l.)...................................................................................3, 18

Alabama Code, 1975, § 23-1-80 (Michie 1986 Repl.

V o l.)........................................................................................... 18

Alabama Code, 1975, § 23-1-86 (Michie 1986 Repl.

V o l.)........................................................................... 2

Alabama Code, 1940, Title 12, § 69 (M ichie)...................... 3

Voting Rights Act, 42 U.S.C. 1973 and 1973(c)... passim

V ll

TABLE OF AUTH ORITIES - Continued

Page

V lll

TABLE OF A UTH ORITIES - Continued

Page

Statutory H istory M aterials:

Hearings on H.R. 6400 before Subcommittee No. 5

of the House Committee on the Judiciary, 89th

Cong., First Sessio n ............................................................ 27

111 Congressional Record 8363 (daily ed. April 23,

1965)......................................................................................... 27

S. Rep. No. 417, 97th Congress, second session

(1982)....................................................................................... 28

M iscellaneous:

Black's Law D ictionary.......................................................... 26

Corpus Juris Secundum.......................................................... 26

OPINIONS BELOW

The opinion of the district court is unreported. The

opinion of the district court is reproduced beginning at JS

A -l.1 The order denying the motion to alter or amend the

judgment is reproduced beginning at JS A-42.

----------------- * ------------------

JURISDICTION

The district court denied the requested injunction on

1 August 1990 and denied the motion to alter or amend

the judgment on 21 August 1990. The Appellants filed

their respective Jurisdictional Statements in this Court on

16 October 1990. This appeal is taken under 28 U.S.C.

§ 1253.

----------------- ♦ ------------------

STATUTORY PROVISIONS

The Fifteenth Amendment to the Constitution, 42

U.S.C. 1973, and 1973c2 are set out in full in the Appendix

to this brief.

♦

STATEMENT OF THE CASE

Appellee totally rejects Appellants' Statement of the

Case. Appellants are traveling on a totally false assumption

1 Unless otherwise noted, references to "JS" may be found

in the Appendix to Appellants' Jurisdictional Statement at the

cited page.

2 42 U.S.C. 1973c is commonly known as "Section 5."

1

2

that prior to 1979, each commissioner had complete con

trol of a virtually autonomous district, including a por

tion of the budget.

Prior to 1979, the road department of Russell County

operated under a district or semi-district system. In 1979

the Russell County Commission consisted of five com

mission members. Two commissioners whose districts

were contained within the city limits of Phenix City,

Alabama had virtually nothing to do with direct supervi

sion of road operations in the county since the roads and

streets in their district were maintained by the Phenix

City Road Department. The three commissioners whose

districts lay outside of Phenix City were personally

involved in the day-to-day management and direct super

visory aspects of the county road work in their district.3

(See A-14, Deposition of John Belk, p. 10). The districts

were approximately the same size and contained approx

imately the same miles of rural roads. (See A-14, Deposi

tion of John W. Belk, page 20.) All county road funds

were budgeted for the county as a whole and were never

divided between the districts. (See A-14, Deposition of

3 The streets and roads within the Phenix City, Alabama

municipal limits are maintained from separate city and state

funds under control of the municipality. In fact, 20% of Russell

County's share of the State gasoline tax by general and local

law goes to the municipalities. (Exhibit 3 to this defendant's

Motion for Summary Judgment). Counties may, with consent of

the city government, work on city streets. Alabama Code, 1975,

§ 23-1-86 (Michie 1986 Repl. Vol.). Since the case was submitted

to the three-judge lower court on depositions and exhibits,

there is no formal record. References herein to exhibits and

depositions are from those submitted to the lower court.

3

John Belk, pp. 8, 9) The three shops were included in a

single road budget always under the control of the entire

county commission. (See Id.)

During the latter part of 1978 and early 1979, a

Russell County grand jury conducted an investigation

involving misuse of county equipment and personnel. As

a result, one of the commissioners was indicted by the

grand jury. The same grand jury recommended that the

county adopt what is commonly known as the "Unit

System". (See A-14, Deposition of John W. Belk, page 8).

Under the Unit System, the county road department is

operated, without regard to district lines, by the county

engineer, a professional appointed by and responsible to

the county commission. See Alabama Code, 1975, § 11-6-1

(Michie 1986 Repl. Vol.).The duties of the county engineer

are specified by state law (§ 11-6-3 of the Code).4 The Unit

system is the system recommended by the Alabama's

State Highway Department and other authorities. (See

A-16, Deposition of Charles Adams, pp. 13, 14).5

Following the grand jury's investigation, indictment

and recommendation, a member of Russell County's

legislative delegation, Rep. Charles Adams, met with the

4 The specifications for county road engineer have been

set out by statute in Alabama since 1939. See Alabama Code,

Title 12, § 69 (Michie 1940).

5 A copy of the pertinent portion of Auburn University

Professor Lansford C. Bell's recommendation was attached as a

part of Exhibit 1 to Russell County's response to the Justice

Department in the Court below. The unit system or a modified

version of the unit system is currently operating in 45 of

Alabama's 67 counties.

4

county commission to encourage adoption of the Unit

System for operating the county road department. During

a meeting on May 18, 1979, the county commission pas

sed a resolution reorganizing the road department under

the Unit System "effective immediately". (Quoted by

lower court's opinion. See Appellant's JS A-3).

Following the meeting of the county commission,

Rep. Adams introduced House Bill 977 into the Alabama

Legislature, which later became Act No. 79-652. (See A-4)

This bill was introduced by Rep. Adams to prevent the

county commission from deciding at a later date to

reverse its resolution of May 18, 1979. (See A-16, page 9 of

Deposition of Charles Adams).

Approximately seven years later, as a result of a

consent decree entered March 17, 1986, in Sumbry v.

Russell County, CV-84-T-1386-E, the county was redis

tricted into seven commission districts, three of which

have a predominantly black population. Although past

discrimination, based on unlawful dilution of black vot

ing strength was alleged, no such finding was entered.

Prior to Sumbry, the five commissioners, while residing in

individual districts, were elected from the county "at

large". Sumbry divided the county into seven districts and

each commissioner is now elected by district. Two of the

commissioners, Mack and Gosha, (Appellants in this

case) are black and were elected in 1986,6 seven years

after the contested legislation was enacted.

6 Mack and Gosha were elected to Districts 4 and 5 respec

tively. District 4 has 1.3 total miles of county-maintained roads

or .2% ; District 5 has 73.92 miles of county-maintained roads

or 13.8%. (See A -ll, formerly Exhibit 3.B. to Defendants'

Motion for Summary Judgment).

5

Appellants instituted an action in the United States

Federal District Court, Middle District of Alabama, on

May 5, 1989 alleging, inter alia, a violation of their voting

rights pursuant to Section 2 of the Voting Rights Act of

1965. After amending their complaint twice (Joint Appen

dix pp. 15, 31), the Appellants, under the authority of 28

U.S.C. § 2284 (West 1978 & 1990 Supp.) requested a three-

judge court to consider whether the Appellee's legislation

converting the county to the unit road system was subject

to the preclearance requirements of the Voting Rights Act,

found in Section 5. Appellants' motion was granted and

on August 1, 1990 the three-judge panel issued an order

which found Russell County's 1979 enactments to be

exempt from Section 5's preclearance requirements.

(Before JOHNSON, Circuit Judge, HOBBS, Chief District

Judge, and THOMPSON, District Judge. J. THOMPSON

dissented.) It is this order which the Appellants have

chosen to challenge before this Court. (The three-judge

court's order is set out in full in Appellants' Jurisdictional

Statement Appendix, beginning at A-l). Their appeal was

docketed on October 26, 1990 and probable jurisdiction

was noted on May 13, 1991.

----------------- « ------------------

SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT

The Court is called upon today to, once again, inter

pret the scope of the preclearance provisions, commonly

known as § 5, of the Voting Rights Act of 1965. This

section provides for federal preclearance of "changes" in

"voting qualifications or prerequisites to voting, or

6

standards, practices, or procedures with respect to vot

ing" not in effect on November 1, 1964. The purposes

behind the Voting Rights Act, as well as its subsequent

accomplishments, are certainly laudable. However, this

Court should affirm the lower court's ruling that Russell

County's conversion to the unitary road system is exempt

from preclearance and that the application of § 5 is not

without "limited compass."7

The Appellants are challenging Appellee Russell

County Commission's 1979 legislative enactments which

converted the county's road system from a district or

semi-district system to a unitary system. This legislation

shifted responsibility for day-to-day supervision of road

authority in the rural districts from individual commis

sioners once elected at-large to a county road engineer

appointed by the county commission as a whole.

The three-judge court below properly recognized that

its role in assessing Russell County's 1979 legislation was

to look for "potential for discrimination", the triggering

mechanism of § 5. The court found that this local legisla

tion, by which minor government powers are reallocated

effecting no change in constituency, falls outside the pur

view of § 5.

The lower court's holding is clearly justified by the

reasoning implicit in several Supreme Court cases and

7 This term is taken from Justice Harlan's concurrence and

dissent in Perkins v. Matthews, 400 U.S. 379, 398 (1966).

7

explicit in several district court cases considering the

"coverage" issue. This reasoning, termed by the Appel

lees a "change in constituency" analysis, contends that

where minor powers are merely shuffled among govern

ment officials who are responsible to the same electorate

or constituency, there simply is no potential for discrimi

nation. This case can be contrasted with the "normal" § 5

case where the proposed change dramatically effects a

shift in constituency, i.e., a switch from district elections

to at-large elections.

Moreover, the district court's ruling is clearly correct

given Alabama's law characterizing the road duties in

question as being purely ministerial. Since the Russell

County Commission held general supervisory authority

over the county road operations both before and after

1979, only shifting the delegation of routine ministerial

duties, there really was no change in terms of the Voting

Rights Act.

Additionally, the Alabama Middle District Court's

ruling is supported by the statutory construction of § 5

and the legislative intent behind the Voting Rights Act.

The impetus behind the Voting Rights Act was the elim

ination of obstacles to blacks exercising their right to

vote, i.e., poll tests, and the augmentation of black voter

registration. The act in general, and § 5 specifically, was

intended to prevent such states from reimposing obsta

cles to black voter registration and was not intended to

intrude upon the day-to-day operation of local govern

ments.

Finally, in considering the reality behind the imple

mentation of Russell County's unitary system in 1979, it

8

is significant that the plan advocated by the Appellants,

equal distribution of road funds and resources between

the districts regardless of need - though this has never

been the law or practice in Russell County - would

actually harm many black constituents. It is apparent that

the Appellant's main complaint is simply a lack of discre

tionary funding to spend in their districts.

WHEREFORE, PREMISES CONSIDERED, the Appel

lee Russell County Commission requests that this Court

affirm the lower court's ruling and hold that Russell

County's 1979 legislation installing the unitary road sys

tem is exempt from the Voting Rights Act's preclearance

requirements.

----------------♦----------------

ARGUMENT

LOCAL LEGISLATION WHICH MERELY SHIFTS MIN

ISTERIAL ROAD DUTIES FROM INDIVIDUAL

COUNTY COMMISSIONERS ELECTED AT-LARGE TO

A ROAD EN G IN EER R ESPO N SIBLE TO THE

COUNTY COMMISSION AS A WHOLE DOES NOT

CONSTITUTE A "CHANGE" WITHIN THE MEANING

OF SECTION 5 OF THE VOTING RIGHTS ACT AND

THEREFORE DOES NOT REQUIRE PRECLEARANCE.

A. The three-judge court correctly found that minor

reallocations of local governmental powers among

elected officials where there is no change in constit

uencies fall outside the purview of Section 5's pre

clearance requirements because there exists no

potential for discrimination.

The three-judge court below recognized that its duty

was simply to determine whether the Russell County,

9

Alabama's 1979 road and bridge enactments constituted a

change under § 5 of the Voting Rights Act of 19658 creat

ing a "potential for discrimination."9 JS A-8. After fully

considering the facts before them and applying the rele

vant law, Alabama's Middle District concluded that a

reallocation of local governmental authority which does

not effect a "significant relative change in the powers

exercised by government officials" and which does not

change the constituencies to which the officials are

responsible, is not a "change" within the meaning of § 5

of the Voting Rights Act. JS A-13, 14.

1. The District Court's ruling is not inconsistent

with prior Supreme Court cases defining the

scope of § 5 coverage.

While never having addressed the specific issue of

whether § 5 would require preclearance of routine real-

locations of ministerial governmental duties which result

in no change in constituency, this Court has certainly left

the door open for the formulation of a "change in constit

uency limitation" in § 5 coverage. In 1984, the factual

backdrop of McCain v. Lybrand, 465 U.S. 236, set the stage

for the Court to determine whether § 5 applied to minor

8 Section 5 has been encoded at 42 U.S.C. § 1973c, hereaf

ter "§ 5". Section 5 is reprinted in full at A-3.

9 Appellants' contention that the three-judge panel below

exceeded its scope of review looking past the threshold cover

age inquiry of "potential for discrimination" into substantive

considerations is insupportable. Even a cursory review of the

lower decision indicates that the court did not deviate from

accepted Section 5 modes of analysis.

10

reallocations of power, including jurisdiction over roads,

and the impact of a change in constituencies. Id. at 239.

Unfortunately, because the contested South Carolina act

put into force more substantial changes (conceded to

come within § 5's coverage), and the main issue focused

upon an interpretation of previous Justice Department

preclearance approval, the Court never reached the minor

reallocations of power enacted by the South Carolina

legislation nor the impact of a change in constituency. See

Id. at 250 n.17. Such questions were left by this Court,

somewhat prophetically, for "future proceedings." Id. at

250 n.17.10

Whereas this honorable Court may have never used

the term "change in constituencies", many of this Court's

§ 5 rulings appear to be, in fact, rooted in a "change in

constituency" analysis. For example, when a suspect

political subdivision converts from district representation

to at-large representation, the "change" creates a poten

tial for discrimination because "[v]oters who are mem

bers of a racial minority might well be in the majority in

one district, but in a decided minority in the county as a

whole." Allen v. State Board of Elections, 393 U.S. 544, 569

(1969). Justice Stewart conducted a similar analysis in

Georgia v. United States, 411 U.S. 526, 534 (1973), where he

framed the coverage issue to be "whether such changes

[single member to multimember districts] have the poten

tial for diluting the value of the Negro vote." To state the

obvious: the potential for vote dilution arises when there

10 The Court's meaning was of course that the questions

listed would be addressed by the district court upon remand.

11

is a change in constituencies. Clearly, Chief Justice War

ren and Justice Stewart engaged in what the Appellee has

termed, for want of a better expression, a "change in

constituency" analysis.

Similarly, reapportionment and annexation schemes

fall within § 5 because their very purpose is to change the

makeup of a constituency, thereby creating a potential for

minority voting strength dilution. See McDaniel v. Sanchez,

452 U.S. 130, 134 (1981) (reapportionment); and Perkins v.

Matthews, 400 U.S. 379, 388 (1971) (annexation); accord,

Pleasant Grove v. United States, 479 U.S. 462, 467 (1987),

and Richmond v. United States, 422 U.S. 358, 362 (1975).

The remaining § 5 coverage cases decided by this

Court have addressed legislation of the nature which

discourages minority candidates from seeking elective

office, thus making the minority's vote ineffective, see,

e.g., Dougherty County Board of Education v. White, 439 U.S.

32, 37 (1978) (rule requiring Board of Education

employees seeking elective office to take unpaid leave of

absence during campaign periods), and Hadnott v. Amos,

394 U.S. 358, 362-65 (1969) (practice requiring minority

candidates to undergo obstacles not required for white

candidates). The Alabama District Court specifically

found that this line of cases was "basically inapposite"

and factually distinguishable from the Appellants' situa

tion in the present case. See JS A-15, n.14.

12

2. The District Court's ruling is consistent with

previous district court decisions which emphas

ize the presence of a change in constituencies as

being evidence of potential for discrimination.

Following this Court's lead in conducting what was,

in essence, a "change of constituency" analysis, see supra,

the lower courts coined the phrase "different constituen

cies" or "changed . . . constituency", finding the analysis

quite helpful in resolving § 5 coverage close calls. Appar

ently, the first district court case to explicitly rely upon a

"change in constituency" analysis to define § 5's scope

was Horry County v. United States, 449 F.Supp. 990, 995

(D.C.D.C. 1978). The court explained that,

An alternate reason for subjecting the new

method of selecting the Horry County govern

ing body to Section 5 preclearance is that the

change involved reallocates governm ental

powers among elected officials voted upon by

different constituencies. Such changes neces

sarily affect the voting rights of the citizens of

Horry County, and must be subjected to Section

5 requirements. Cf. Perkins v. Matthews, supra;

Allen v. State Board of Elections, supra.

Id. Note that the three-judge district court did not see

themselves as formulating a "novel" § 5 coverage theory;

rather, the court was simply relying upon the Supreme

Court's reasoning in Perkins and Allen, supra. See Id.

The "different constituency" paradigm was elevated

from "an altern ate reason for subjecting . . . [a

change] . . . to Section 5 preclearance", Id. (emphasis

added), to "the most relevant attribute of the challenged

act" in Hardy v. Wallace, 603 F.Supp. 174, 178 (N.D. Ala.

13

1985) (emphasis added). In Hardy, the change in constitu

encies and resultant discriminatory potential created by

Alabama's Act No. 507 in 1983 is quite illustrative of why

the "change in constituency" analysis is so particularly

effective in assessing § 5 coverage. In 1975, the Alabama

legislature created the Greene County Racing Commis

sion whose members were to be appointed by the all

white legislative delegation representing Greene County

at the time. Id. at 175. The powers of the commission were

significant since the county racetrack would become the

county's largest employer and would be responsible for

63% of the county's tax revenue. Id. at 176. In 1983, when

it became clear that a reapportionment plan gave blacks

the power to elect black candidates to the Greene County

le g is la tiv e d e le g a tio n ,11 the Alabam a leg isla tu re

responded by transferring the power to appoint racing

commission members from the Greene County legislative

delegation to the Governor of Alabama, George Wallace, a

white male. The "potential" for discrimination existed

because the appointive powers and its corresponding

influence were taken away from the legislative delegation

responsible to the majority black Greene County voters

and bestowed upon a governor who was responsible to

the state-wide voters, 99% exclusive of Greene County

voters and majority white in makeup. Id. at 176, 179.

The most recent district court decision overtly relying

on a "change of constituency" analysis is Robinson v.

11 Compare the timing of this legislation with Russell

County's 1979 reallocation of day-to-day road and bridge

authority which occurred seven years before appellants Mack

and Gosha or any other black was elected to the Russell

County Commission.

14

Alabama State Board of Education, 652 F.Supp. 484 (M.D.

Ala. 1987) (three-judge panel). The district court was

called upon to analyze Perry County's shift in Marion

city school authority from a county board of education

elected county-wide by a black majority to a city board of

education appointed by Marion City Council members

who were, in turn, elected by the city's white majority. Id.

at 485. The panel's order, drafted by Judge Thompson12,

extended § 5 coverage "[fjirst," because "the resolution

changed the constituency that selected those who super

vised and controlled public schools within the city." Id. at

486 (emphasis in original). The court continued to explain

that "[pjrior to the resolution, county voters elected the

board members who controlled public schools in the city;

under the resolution, however, the city council selected

the board members who controlled city schools." Id.

(emphasis in original).

The common denominator in Horry, Hardy and Robin

son,13 all cases where § 5 coverage was extended, is a

potential for discrimination which arises out of a change

in constituencies whereby minority voting strength can

be either overtly or covertly diluted. This "relevant attrib

ute"14 is conspicuously absent from the Russell County

legislation in the case at bar. Before 1964 and up until

12 Judge Thompson, ironically, was a dissenter in the

lower court's ruling in the case at bar.

13 Arguably, County Council of Sumter County, South Caro

lina v. United States, 555 F.Supp. 694 (D.C.D.C. 1983) relies on a

change in constituency analysis for its holding also but not as

explicitly as Horry, Hardy, and Robinson.

14 This term is taken from Hardy v. Wallace, supra, at 178.

15

1979, the county commission as a whole held general

supervisory authority over the county road system and

delegated direct or day-to-day supervision of the road

system to three rural district county commissioners

elected at large and responsible to the county as a whole.

The 1979 enactments maintained the vestment of general

supervisory authority in the Russell County Commission,

but delegated the direct or day-to-day authority over

county road operations to a professional county engineer

appointed by, and under the authority of the same county

commission. The three judge panel put it most succinctly

when it found that "[bjoth before and after the 1979

change, the official responsible for road operations in

each district was elected by, or responsible to, all the

voters of the county." JS A-16.

While Horry, Hardy and Robinson all use the constitu

ency analysis to extend § 5's coverage, Judge Vance

implicitly recognized in Hardy that the same reasoning

could be used to limit § 5 coverage when he, in dictum,

opined:

The ordinary or routine legislative mod

ification of the duties or authority of elected

officials or changes by law or ordinance in the

makeup, authority or means of selection of the

vast majority of local appointed boards, com

missions and agencies probably are beyond the

reach of section 5, even given its broadest inter

pretation.

Hardy at 178, 179. The instant lower court in its wisdom

recognized the Russell County scenario as the vehicle in

which Judge Vance's cautionary dictum in Hardy would

ripen into a ruling.

16

3. The District Court's ruling is consistent with

prior positions held by the Justice Department

emphasizing change in constituencies as indica

tive of potential for discrimination.

While the Justice Department has decided to support

the Appellants in the instant case, their position generally

upon reallocation of authority and the impact of a change

in constituency is far from settled. This conclusion is

evident not only from the Department's failure to pro

mulgate applicable regulations on the subject, see JS A-15,

but also from its position in earlier cases which is con

trary to its stand today. As recently as 1985, the United

States Attorney General wrote the Alabama Attorney

General concerning the Hardy legislation, described supra.

The Justice Department first objected, then withdrew its

objection to the Hardy legislation stating, "[i]t is certainly

not the case that every reallocation of governmental

power is covered by Section 5 ."15 See Appendix B to

Hardy v. Wallace, 603 F.Supp. at 181. While the Justice

Department may claim that its position in Hardy favoring

such a § 5 limitation is merely a recent aberration, the

truth is that as early as 1969 the Department embraced

the position that, "Section 5 applies to laws [that] sub

stantially change the constituency of certain officials . "

Perkins v. Matthews, 400 U.S. at 391, n.10, quoting the

Justice Department's amicus brief in Fairley v. Patterson,

393 U.S. 544 (1969). From any fair reading of the Justice

15 It appears that, to some extent, it was Hardy v. Wallace

that led Alabama's Attorney General to decide that it was

unnecessary to submit Russell County's legislation for federal

preclearance. (Stipulated Testimony of Lynda K. Oswald,

A-10). The unit system or modified unit system is currently

operating in 45 of Alabama's 67 counties.

Department's position in both Hardy and Fairley, one is

caused to wonder why the Department did not choose to

write its amicus brief in favor of Appellee.

B. The County Commission by state law has always

held general supervisory authority over the county

road system and therefore, the delegation of "minis

terial" road and bridge duties to an appointed

county road engineer does not effect a "change"

within the meaning of Section 5.

While the Alabama District Court focused on the linkage

between changes in constituency and potential for discrimi

nation, the Appellee has, throughout the proceedings,

asserted a subtly different additional ground for the denial of

§ 5 coverage in this case: given Alabama's history of inves

ting the county commission with ultimate or general super

visory authority over county road operations, the 1979

Russell County enactments simply did not effect a "change"

within the meaning of § 5. A comparison with the ruling of

the district court is helpful. The district court found, in terms

of constituency, "[b]oth before and after the 1979 change, the

official responsible for road operations in each district was

elected by, or responsible to, all the voters of the county.

Thus, there was no change in potential for discrimination

against minority voters." JS A-16 (emphasis in original). The

Appellee's proffered alternative ground is similar. Both

before and after 1979, the county commission was clothed

with the ultimate authority over county road and bridge

systems. The fact that in 1979 ministerial or administrative

road duties once delegated to rural district commissioners

were rerouted to a county employee, the county engineer, is

irrelevant in terms of § 5.

18

1. Under Alabama law the county commission act

ing as a unit has always been vested with gen

eral supervisory authority over the county's

road system with the power to delegate admin

istrative or ministerial duties to subordinates.

The appellants have attempted to convince the Court

that prior to 1979 Russell County commissioners were

autonomous road bosses who reigned sovereignly over

their road district "fiefdoms". While this has never been

the practice in Russell County or anywhere in Alabama;

more significantly, it has never been the law in Alabama.16 17

Although admittedly the rural district commissioners

exercised direct supervision16 17 18 over his residency district's

road maintenance, the county commission has always

been entrusted with "general superintendence of public

roads and bridges." See Court of Commissioners of Pike

County v. Johnson, 229 Ala. 417, 419, 157 So. 481

16 The relevant sections of Alabama's code which describe

the road and bridge authority of the county commission and

what authority, duties, or functions may be delegated to a

county road engineer or supervisor are set out in Appellee's

appendix. See A-5, Alabama Code, 1975, § 23-1-80 (Michie 1986

Repl. Vol.) and A-8, Alabama Code, 1975, § 11-6-3 (Michie 1989

Repl. Vol.)

17 In other contexts, this Court has looked to state law to

determine the authority and function of local officials, see, e.g.,

Sf. Louis v. Praprotnick, 485 U.S. 112, 124 (1988) (Section 1983).

18 Appellee employs the term "direct supervision" to

mean day-to-day responsibility for completion of tasks and

overseeing of workers as opposed to "general supervision"

which denotes a responsibility for the formulation of long

range objectives and major budget allocations.

19

(1934). Any duty or power held by the individual district

commissioner was "administrative in character" and

would be "subordinate to, in co-operation with, and in aid

of this court [of commissioners], which is still vested with

general jurisdiction and supervision. . . . " Id. at 420

(emphasis added). The state's supreme court in Court of

Commissioners unequivocally rejected the notion of auton

omous district commissioners.

. . . [T]here was no intention to transfer

these governmental powers from the governing

body of the county and vest them in the com

missioner of each district. Such construction

would destroy the unity of county government,

and set up several rival government units of one

man each, which, with undefined powers,

would lead to great confusion.

Id. at 419. Clearly, no individual commissioner wielded

the kind of autonomy over road and bridge matters, even

within his residency district, that is suggested by Appel

lants.

Further, the creation of the post of county road engi

neer who would be responsible for direct supervision of

road construction and maintenance took nothing away

from the county commission in terms of road and bridge

authority. In Thompson v. Chilton County, 236 Ala. 142, 181

So.701 (1938), Alabama's Supreme Court interpreted a

statute apparently very similar to the 1979 Russell

County legislation at issue. The Thompson opinion

described the limitations of the county road supervisor's

authority (precursor to the county road engineer) in

terms virtually identical to Court of Commissioner's

20

description of an individual commissioner's road author

ity limitations, supra.

To be sure the Road Supervisor is charged

with the duty of supervising the construction,

maintenance and repairing the public roads in

said county, but this does not mean that he

displaces, in this respect, the Court of County

Commissioners. . . . This supervisor is required

to be a civil engineer, and his duties and author

ity in no wise conflict with the general powers

of the court [of commissioners]. He is in imme

diate charge of the construction, maintenance

and repair of the roads, but his duties are purely

ministerial, and subordinate to the Court of

County Commissioners.

Thompson at 145 (emphasis added).

If the pre-1979 district commissioner exercised only

"administrative" road duties which were "subordinate

to" the county commission's road superintendence and

the post-1979 county engineer can only exercise "purely

ministerial" functions "subordinate to" county commis

sion road authority, there was no "change" which could

trigger preclearance under § 5. The county commission as

a whole as well as each individual commissioner main

tained the same general supervisory superintendence

powers before 1979 as they did after 1979. There simply

was no change in the substantive powers held by the

commission.

21

2. The delegation of administrative or ministerial

duties comes within the "administrative or min

isterial exception" implicit in section 5 coverage

decisions.

Although neither this Court nor any district court has

explicitly relied upon an "administrative or ministerial

exception" to limit the coverage of § 5, the framework has

been laid for the formulation of such an exception. In

McCain v. LybrandA9 465 U.S. at 239, this Court considered

the description of a county commission's powers as

"administrative and ministerial" significant enough to

note the description within its opinion. The Court never

was presented with the opportunity to comment upon the

impact such a designation might have on § 5 coverage

because of the procedural posture of the case.19 20 In

NAACP v. Hampton County Election Comm., 470 U.S. 166,

175 (1985), this Court extended § 5 coverage to legislation

creating a two week filing period for a school district

election to be held six months later. The lower court

found that preclearance was unnecessary because "the

scheduling of the election and the filing period were

ministerial acts necessary to accomplish the statute's pur

pose." Id. at 174 (internal quotation marks omitted)

(emphasis added). Interestingly, this Court, in striking

down the lower decision, did not hold that there was no

19 McCain is discussed in a slightly different context supra,

in part A.

20 Besides the fact that the contested legislation in McCain

enacted numerous "changes" in voting practices conceded to

fall within the ambit of Section 5, See McCain at 239-240, 250

n.18, the primary issue before the court involved the inter

pretation of the Justice Department's approval of an earlier

submission. Id. at 239.

22

"ministerial exception" - though the opportunity to do so

was clearly before the court. Rather, the Court rejected

the lower court's characterization of the acts as ministerial

in light of the Voting Rights Act's objectives. Id. at 175.21

Similarly, in Robinson v. Alabama State Board of Educa

tion, supra, 652 F.Supp. at 486, the three-judge federal

court from Alabama addressed a "change" in city school

authority which the defendants characterized as merely

"administrative" in nature. Again, the door was open for

the court to rule that there simply was no "administrative

exception" within § 5. The Robinson court, mimicking

NAACP, chose not to do so; but instead, disagreed "with

the defendants' characterization." Id. It is certainly not

unreasonable to conclude from the NAACP and Robinson

holdings, that in the right factual context, an act which

can be fairly characterized as ministerial or administrative

may not require preclearance under § 5.

Therefore, in the case at bar, where the challenged

acts can be fairly characterized as "m inisterial" or

"administrative"22 , the right fact situation is before the

Court to explicitly recognize an exception that has to this

point remained implicit. This Court should hold that the

21 The Court did rule that "minor alterations" in voting

practices were not exempt from Section 5. NAACP at 176.

Appellee's reading of the ruling in NAACP is justified on the

ground that while the terms "minor" and "ministerial" are

similar, they are not synonymous.

22 Appellee would go so far as to assert that the designa

tion of the road authority in question has been conclusively

characterized as "ministerial" or "administrative" by the Ala

bama Supreme Court cases cited supra.

23

daily supervisory responsibility over a county's road

maintenance program is clearly ministerial or administra

tive in nature and therefore should be excluded from the

"potential severity"23 of § 5 preclearance burdens.

C. The Voting Rights Act was "aimed" at voter regis

tration and was never intended to introduce the

heavy hand of federal scrutiny into routine local

enactments which have no apparent nor real impact

upon minority voting rights.

On August 6, 1965, the legislation commonly known

as The Voting Rights Act went into effect. This legislation,

passed by Congress pursuant to § 2 of the Fifteenth

Amendment to the United States Constitution24 man

dated that,

No voting qualification or prerequisite to

voting, or standard, practice, or procedure shall

be imposed or applied by any State or political

subdivision to deny or abridge the right of any

citizen of the United States to vote on account of

race or color, or in contravention of the guaran

tees set forth in section 1793b(f) (2) of this title.

42 U.S.C. § 1973. The task of this Court today is to

interpret the meaning and intent behind one of the many

enforcement provisions of the Voting Rights Act, § 5, the

23 This term is taken from Morris v. Gressette, 432 U.S. 491,

504 (1977).

24 The text of the 15th Amendment is set out, in full, at

A-l.

24

preclearance provision. This section mandates pre

clearance or prior approval to be sought and obtained

from the United States Attorney General or the Federal

District Court of the District of Columbia "[w]henever a

[suspect] State or political subdivision . . . shall enact or

seek to administer any voting qualification or prerequi

site to voting, or standard, practice, or procedure with

respect to voting different from that in force or effect on

November 1, 1964 . 42 U.S.C. § 1973c.

While it is one thing to convey to Congress an intent

to give the Voting Rights Act "the broadest possible

scope"25 of application; it is quite another matter to emas

culate the section of any meaningful limit.26 Although

this Court has never been confronted with the right facts

justifying § 5's limitation, such does not indicate that the

provision is without boundary. Arguably, this Court has

never had the occasion to comment upon legislation, like

the 1979 Russell County enactments, which have such a

de minimis (if any) impact on voting rights. Certainly, this

Court has described the breadth of § 5 in sweeping terms;

however, these descriptions of § 5 must be interpreted in

the context of the facts before the Court. In each case, the

Court was addressing legislation that had a clear and

undeniable impact on minority voting strength. For

instance, the opinions in Katzenbach, Allen and Perkins

arose out of patent attempts by a political subdivision to

dilute minority voting strength: voter registration tests

25 Allen v. State Board of Elections, 393 U.S. at 565.

26 See Perkins v. Matthews, 400 U.S. at 398 (J. Harlan con

curring in part and dissenting in part).

25

and devices,27 shifts from district to at-large representa

tion,28 and annexations.29 Admittedly, Hadnott30 31 and

Dougherty County3'1 took this Court's interpretation of § 5

one step further when it applied § 5 to legislation

discouraging minority candidacy. Russell County's

enactments present something totally new: a challenge to

legislation which has no discernible impact on minority

voting practices, procedures or patterns. The idea that

these changes, like the ones in Dougherty, "reduce[d]

in some manner the autonomy or political potency of

. . . th e c o u n t y c o m m i s s i o n e r s in R u s s e l l

. . . Count[y]" is plainly inconsistent with an appreciation

of the facts in this case, as found by the three judge panel.

See JS A-15 at n.14.

The most relevant indication of the intent of the 89th

Congress in drafting this legislation, the text itself,

plainly places the emphasis on voting qualifications, pre

requisites, and voting standards, practices or procedures.

See 42 U.S.C § 1973. The phrase "any voting standard,

practice, or procedure with respect to voting" must be

interpreted in this light. See 42 U.S.C. § 1973c. The phrase

"with respect to voting" only has meaning within the

context of voting qualifications, prerequisites, standards,

practices or procedures. The farther one gets away from

27 South Carolina v. Katzenbach, 383 U.S. 301, 329-30 (1966).

This case was a bill in equity which challenged the constitu

tionality of the Voting Rights Act in its entirety.

28 Allen, 393 U.S. at 569.

29 Perkins v. Matthews, 400 U.S. at 387, 388.

30 Hadnott, 394 U.S. 358, 362-365.

31 Dougherty County v. Board of Education, 439 U.S. 32, 37.

26

the items listed in § 1973, the more tenuous is the applica

tion of § 1973c,32 even though there is some, broadly

defined impact upon voting. To give the phrase "with

respect to voting" any other meaning is to presume the

89th Congress intended the absurd33 - the Voting Rights

Act would apply to every local law, ordinance, or regula

tion virtually without exception, because it had an

"impact" on minority voting strength.

Appellee's reading of § 1973c, in light of § 1973, is

equally supported by sources of legislative intent outside

the text. Attorney General Katzenbach, who is widely

recognized to have played a large role in the drafting and

passage of the Voting Rights Act, stressed that the "bill

32 The rule of construction, Ejusdem generis, is applicable

here. Black's Law Dictionary defines Ejusdem generis as:

Of the same kind, class, or nature. In the con

struction of laws, wills, and other instruments, the

"ejusdem generis rule" is, that where general words

follow an enumeration of persons or things, by

words of a particular and specific meaning, such

general words are not to be construed in their widest

extent, but are to be held as applying only to persons

or things of the same general kind of class as those

specifically mentioned . . . .

33 Attributing to Congress such a presumption is in direct

contravention of normal rules of statutory construction. See 82

C.J.S. Statutes, § 316 (1953).

27

really is aimed at getting people registered. . . . " 34 1965

House hearings 21, cited in Hardy v. Wallace, 603 F.Supp.

174, 182 (J. Propst concurring). Senator Jacob Javits, one

of the principal sponsors of the Voting Rights Act,

explained that § 5's purpose was to prevent states from

substituting new methods of voting qualifications and

procedures for proscribed tests and devices suspended by

§ 4.35 Another principle advocate, Senator Tydings, on the

same day, explained that the suspension of voting tests

and appointment of Federal examiners were "the heart of

the bill."36

34 Assistant Attorney General Burke Marshall concurred.

In House hearings, he answered a congressman's question by

stating, "the problem that the bill was aimed at was the prob

lem of registration, Congressman. If there is a problem of

another sort, I would like to see it corrected, but that is not

what we were trying to deal with in the bill." Hearings on H.R.

6400 before subcommittee No. 5 of the House Committee on

the Judiciary, 89th Cong., first session, page 74.

35 Senator Javits commented that,

Section 5 deals with attempts by States or politi

cal subdivisions whose tests or devices have been

suspended under Section 4 to alter voting qualifica

tions and procedures which were in effect on

November 1, 1964. Section 5 permits a State or politi

cal subdivision to enforce new requirements only if it

submits the new requirements to the Attorney Gen

eral and the Attorney General does interpose objec

tions within sixty days thereafter.

I l l Cong. Rec. 8363 (daily ed. April 23, 1965).

36 111 Cong. Rec. 8366 (daily ed. April 23, 1965).

28

It was not the intent of Congress to intrude upon

local legislative processes far removed from any colorable

impact upon voting rights. Bill proponent Senator Javits

protested that the act was "not introduced to federalize

the voting process, but to aid the disenfranchised Ameri

can to exercise the franchise." Id. at 8363. When Congress

extended application of the Voting Rights Act in 1982, the

official Senate report stated that Congress had originally

intended for the act to "cover voting rights while allow

ing the legitimate processes of government to go on."37

Therefore, this Court should, while maintaining § 5's

broad application to voting practices, reject the Appel

lants' all encompassing interpretation of § 5 which pro

vides no reasonable limit to its coverage. Affirmation of

the lower court's ruling is proper, if for no other reason,

because, "[t]he language of section 5 clearly provides that

it applies only to proposed changes in voting pro

cedures." Beer v. United States, 425 U.S. 130, 138 (1976).

D. Russell County's 1979 enactments not only lack a

"potential for discrimination" as found by the

three-judge panel; in reality, the conversion to the

unitary road system actually brings the most bene

fit to Russell County's black constituents.

While a three-judge panel may, in the abstract, opine

that the motive behind and the actual effect of a chal

lenged enactment are "irrelevancfiesj", Turner v. Webster,

637 F.Supp. 1089, 1092 (N.D. Ala. 1986) (three-judge

37 S. Rep. No. 417, 97th Congress, Second Session (1982) at

8.

29

court), this Court has said that Section 5's main concern is

"the reality of changed practices as they affect Negro voters."

See Georgia v. United States, 411 U.S. 526, 531 (1973). In other

words, though the judiciary's responsibility in determining

§ 5 coverage is to focus upon the "potential for discrimina

tion" and not the substantive aspects of the Voting Rights

Act; in assessing the "potential for discrimination", it is

necessary to have an appreciation of the facts surrounding

Russell County's 1979 enactments.

The "reality" behind Russell County's 1979 "changed

practices" is simple: the people of Russell County made a

decision that the unitary road maintenance system was supe

rior to the district system of road management. The district

system had generated duplication and waste, lacked accoun

tability and invited corruption. As a direct response to the

indictment of a county commission for abuse of his office,

the choice for the unitary system was made - all this nearly

seven years before a black candidate was elected to the

Russell County Commission. Governmental integrity bene

fits black constituents as well as white. The Appellants have

strained to implicate some sort of racial animus in a situation

where it just does not exist.

Further, Appellants Mack and Gosha apparently do

not have a problem with the unitary system as much as

they want "discretionary funds" to spend in their dis

tricts.38 Both Mack and Gosha voted in favor of the road

budgets.39 Their common complaint is that they do not

38 See A-18, Deposition of Nathaniel Gosha, pages 35, 36,

82, 84 and see A-21, Deposition of Jerome Gray, page 21. Jerome

Gray is the Field Director for the Alabama Democratic Confer

ence, the black caucus of the Alabama Democratic Party.

39 See A-18, Deposition of Nathaniel Gosha, page 17 and

A-20, Deposition of Ed Mack, page 17.

30

have an "equal share" of revenue to spend in their dis

tricts. Such political dilemmas - so completely devoid of

racial overtones - are not the "stuff" of which Voting

Rights Act challenges are made.

Finally, it is interesting to note that the plan advocated

by Appellants to divide road funds equally between the

districts, regardless of need, would actually be less beneficial

to most black Russell County constituents. District 7, one of

the more heavily populated rural districts and containing

almost 60% of the county's roads40, is predominantly black

though their chosen representative Commissioner Allen is

white. Thus, Appellants' plan to equally divide road

resources regardless of need would actually take away

resources from this majority black district.

E. The three-judge panel, while according the defer

ence due to the Justice Department's position, prop

erly and prudently chose to override the Justice

Department's position and rule in the favor of the

Russell County Commission.

Certainly, the position of the Justice Department is to

be accorded considerable deference due to the major role

it played in the drafting of § 5; yet, its view is not

dispositively binding upon a three-judge court's deter

mination of § 5 coverage cases. Lucas v. Townsend, 698

F. Supp. 909, 911 (M.D. Ga. 1988). It is not rare for a court,

after carefully considering the Department's position, to

40 District 5, represented by Appellant Mack, has 13.8% of

the county roads. District 4, represented by Appellant Gosha,

has only 1.3 miles of county roads within its borders. See

breakdown of road mileage by district in A-ll.

31

reject the Department's leading and make what it views

to be the most accurate application of § 5. See, e.g., Hardy

v. Wallace, 603 F.Supp. 174, 177, n.5 and 181-182.

The instant three-judge panel carefully weighed the

Attorney General's opinion but because the department's

position on the matter had not been settled enough even

to promulgate new regulations for guidance in this area,

the court felt justified to make an independent judgment

of the issues presented. JS A-15.

----------------- ♦------------------

CONCLUSION

Based upon the foregoing, Appellee request that this

court affirm the lower court's holding which found the

Appellee Russell County Commission exempt from the

preclearance requirements of § 5 of the Voting Rights Act

of 1965.

Respectfully submitted,

James W. W ebb,

Counsel of Record

K endrick E. W ebb

Counsel for Appellee

W ebb, C rumpton, McG regor,

Davis & A lley

One Commerce Street, Suite 700

P.O. Box 238

Montgomery, Alabama 36101-0238

(205) 834-3176

APPENDIX

1

APPENDIX

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Page

Fifteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution.......... A-l

42 U.S.C.A. § 1973 (West 1981)........................................ A-l

42 U.S.C.A. § 1973c (West 1981)............................ A -l, 2, 3

Act No. 79-652, Acts of Alabama 1979 .................. A-4, 5

Alabama Code, 1975, § 23-1-80 (Michie 1989 Repl.

V o l.).................................................................................A-5, 6

Alabama Code, 1923, § 1347 (Michie)........................ A-6, 7

Alabama Code, 1940, Title 23 § 43 (Michie)............ A-7, 8

Alabama Code, 1975, § 11-6-3 (Michie 1989 Repl.

V o l.)........................................................................................ A-8

Alabama Code, 1940, Title 12 § 69 (Michie)..................A-9

Stipulated Testimony of Lynda K. Oswald. .A-10, 11, 12

Breakdown of Roadway Mileage Maintained or

Under Jurisdiction of Russell County by Com

mission Districts...............................................................A-l 3

Deposition of John B e lk .......................................... A-l 4, 15

Deposition of Charles Adam s................................ A-16, 17

Deposition of Nathaniel Gosha.............................. A-l 8, 19

Deposition of Ed P. Mack.................................................A-20

Deposition of Jerome Gray................................................A-21

A-1

FIFTEENTH AMENDMENT TO THE U.S. CONSTITU

TION

Section 1. The right of citizens of the United States

to vote shall not be denied or abridged by the United

States or by any State on account of race, color, or pre

vious condition of servitude.

Section 2. The Congress shall have power to

enforce this article by appropriate legislation.

42 U.S.C.A. § 1973 (West 1981)

No voting qualification or prerequisite to voting, or

standard, practice, or procedure shall be imposed or

applied by any State or political subdivision to deny or

abridge the right of any citizen of the United States to

vote on account of race or color, or in contravention of the

guarantees set forth in section 1973b(f)(2) of this title.

42 U.S.C.A. § 1973c (West 1981)

Whenever a State or political subdivision with

respect to which the prohibitions set forth in section

1973b(a) of this title based upon determinations made

under the first sentence of section 1973b(b) of this title are

in effect shall enact or seek to administer any voting

A-2

qualification or prerequisite to voting, or standard, prac

tice, or procedure with respect to voting different from

that in force or effect on November 1,1964, or whenever a

State or political subdivision with respect to which the

prohibitions set forth in section 1973b(a) of this title

based upon determinations made under the second sen

tence of section 1973b(b) of this title are in effect shall

enact or seek to administer any voting qualification or

prerequisite to voting, or standard, practice, or procedure

with respect to voting different from that in force or effect

on November 1, 1968, or whenever a State or political

subdivision with respect to which the prohibitions set

forth in section 1973b(a) of this title based upon deter

minations made under the third sentence of section

1973b(b) of this title are in effect shall enact or seek to

administer any voting qualification or prerequisite to vot

ing, or standard, practice, or procedure with respect to

voting different from that in force or effect on November

1, 1972, such State or subdivision may institute an action

in the United States District Court for the District of

Columbia for a declaratory judgment that such qualifica

tion, prerequisite, standard, practice, or procedure does

not have the purpose and will not have the effect of

denying or abridging the right to vote on account of race

or color, or in contravention of the guarantees set forth in

section 1973b(f)(2) of this title, and unless and until the

court enters such judgment no person shall be denied the

right to vote for failure to comply with such qualification,

prerequisite, standard, practice, or procedure: Provided,

That such qualification, prerequisite, standard, practice,

or procedure may be enforced without such proceeding if

A-3

the qualification, prerequisite, standard, practice, or pro

cedure has been submitted by the chief legal officer or

other appropriate official of such State or subdivision to

the Attorney General and the Attorney General has not

interposed an objection within sixty days after such sub

mission, or upon good cause shown, to facilitate an expe

dited approval within sixty days after such submission,

the Attorney General has affirmatively indicated that

such objection will not be made. Neither an affirmative

indication by the Attorney General that no objection will

be made, nor the Attorney General's failure to object, nor

a declaratory judgment entered under this section shall

bar a subsequent action to enjoin enforcement of such

qualification, prerequisite, standard practice, or pro

cedure. In the event the Attorney General affirmatively

indicates that no objection will be made within the sixty-

day period following receipt of a submission, the Attor

ney General may reserve the right to reexamine the sub

mission if additional information comes to his attention

during the remainder of the sixty-day period which

would otherwise require objection in accordance with this

section. Any action under this section shall be heard and

determined by a court of three judges in accordance with

the provisions of section 2284 of Title 28 and any appeal

shall lie to the Supreme Court.

A-4

Act No. 79-652 H. 977 - Adams (C), Whatley

AN ACT

Relating to Russell County: to provide that all func

tions, duties and responsibilities for the construction,

maintenance and repair of public roads, highways,

bridges and ferries in the county shall be vested in the

county engineer and shall be maintained on the basis of

the county as a whole, without regard to district or beat

lines, and to prescribe certain duties for the county engi

neer.

Be It Enacted by the Legislature of Alabama:

Section 1. All functions, duties and responsibilities

for the construction, maintenance and repair of public

roads, highways, bridges and ferries in Russell County

are hereby vested in the county engineer, who shall,

insofar as possible, construct and maintain such roads,

highways, bridges and ferries on the basis of the county

as a whole or as a unit, without regard to district or beat

lines.

Section 2. The county engineer shall assume the

following duties, but shall not be limited to such duties:

(1) to employ, supervise and direct all such assis

tants as are necessary properly to maintain and construct

the public roads, highways, bridges, and ferries of

Russell County, and he shall have authority to prescribe

their duties and to discharge said employees for cause, or

when not needed; (2) to perform such engineering and

surveying service as may be required, and to prepare and

maintain the necessary maps and records; (3) to maintain

the necessary accounting records to reflect the cost of the

A-5

county highway system; (4) to build, or construct new

roads, or change old roads, upon the order of the county

commission; (5) insofar as is feasible to construct and

maintain all country [sic] roads on the basis of the county

as a whole or as a unit.

Section 2. The provisions of this act are severable. If

any part of this act is declared invalid or unconstitu

tional, such declaration shall not affect the part which

remains.

Section 3. All laws or parts of law which conflict

with this act are hereby repealed.

Section 4. This act shall become effective imme

diately upon its passage and approval by the Governor,

or upon its otherwise becoming a law.

Approved July 30, 1979

Time: 6:00 P.M.

Alabama Code, 1975, § 23-1-80 (Michie 1989 Repl. Vol.)

The county commissions of the several counties of this

state have general superintendence of the public roads,

bridges and ferries within their respective counties so as

to render travel over the same as safe and convenient as

practicable. To this end, they have legislative and execu

tive powers, except as limited in this chapter. They may

establish, promulgate and enforce rules and regulations,

make and enter into such contracts as may be necessary

or as may be deemed necessary or advisable by such

A-6

commissions to build, construct, make, improve and

maintain a good system of public roads, bridges and

ferries in their respective counties, and regulate the use

thereof; but no contract for the construction or repair of

any public roads, bridge or bridges shall be made where

the payment of the contract price for such work shall

extend over a period of more than 20 years. (Code 1923,

§ 1347; Acts 1927, No. 347, p. 348; Code 1940, T. 23, § 43;

Acts 1953, No. 729, p. 984.)

Alabama Code, 1923, § 1347 (Michie).

1347. (5765) Powers of courts of county commission

ers with regard to roads, bridges and ferries. - The

courts of county commissioners, boards of revenue, or

other like governing bodies of the several counties of this

state have general superintendence of the public roads,

bridges and ferries within their respective counties, and

may establish new, and change and discontinue old

roads, bridges and ferries in their respective counties so

as to render travel over the same as safe and convenient

as practicable. To this end they have legislative, judicial,

and executive powers, except as limited in this article.

Courts of county commissioners, boards of revenue, or

courts of like jurisdiction are courts of unlimited jurisdic

tion and powers as to the construction, maintenance and

improvement of the public roads, bridges and ferries in

their respective counties, except as their jurisdiction or

powers may be limited by the local or special statutes of

the state. They may establish, promulgate and enforce

A-7

rules and regulations, make and enter into such contracts

as may be necessary, or as may be deemed necessary or

advisable by such courts, or boards, to build, construct,

make, improve and maintain a good system of public

roads, bridges and ferries in their respective counties,

and regulate the use thereof; but no contract for the

construction or repair of any public road, bridge or

bridges shall be made where the payment of the contract

price for such work shall extend over a period of more

than ten years.

Alabama Code, 1940, Title 23 § 43 (Michie).

§ 43. (1347) Powers of courts of county commission

ers with regards to roads, bridges and ferries. - The

courts of county commissioners, boards of revenue, or

other like governing bodies of the several counties of this

state have general superintendence of the public roads,

bridges and ferries within their respective counties so as

to render travel over the same as safe and convenient as

practicable. To this end they have legislative, judicial and

executive powers, except as limited in this chapter.

Courts of county commissioners, boards of revenue, or

courts of like jurisdiction are courts of unlimited jurisdic

tion and powers as to the construction, maintenance and

improvement of the public roads, bridges and ferries in

their respective counties, except as their jurisdiction or

powers may be limited by the local or special statutes of

the state. They may establish, promulgate and enforce

rules and regulations, make and enter into such contracts

A-8

as may be necessary, or as may be deemed necessary or

advisably by such courts, or boards, to build, construct,

make, improve and maintain a good system of public

roads, bridges and ferries in their respective counties,

and regulate the use thereof; but no contract for the

construction or repair of any public roads, bridge or

bridges shall be made where the payment of the contract

price for such work shall extend over a period of more

than ten years. (1927, p. 348.)

Alabama Code, 1975, § 11-6-3 (Michie 1989 Repl. Vol.)

It shall be the duty of the said county engineer or

chief engineer of the division of public roads, subject to

the approval and direction of the county commission to:

(1) Employ, supervise and direct such

assistants as are necessary to construct and

maintain properly the county public roads,

highways and bridges;