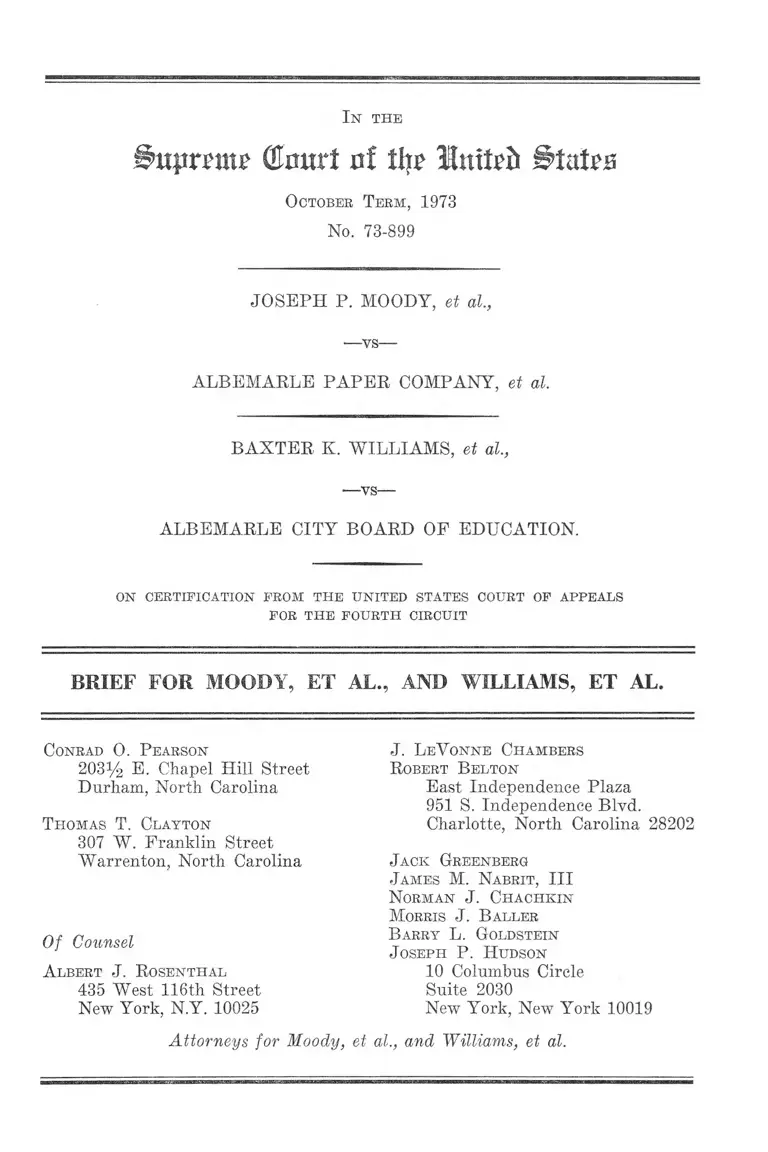

Moody v. Albemarle Paper Company Brief for Moody, et al. and Williams, et al.

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1973

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Moody v. Albemarle Paper Company Brief for Moody, et al. and Williams, et al., 1973. c6a0b92f-be9a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c43d8f93-8eb2-4080-ad7e-aee58a176220/moody-v-albemarle-paper-company-brief-for-moody-et-al-and-williams-et-al. Accessed February 22, 2026.

Copied!

In t h e

(tart at % InttrJi ^tatrs

October Term, 1973

No. 73-899

JOSEPH P. MOODY, et al.,

—vs—

ALBEMARLE PAPER COMPANY, et al.

BAXTER K. WILLIAMS, et al.,

—vs—

ALBEMARLE CITY BOARD OF EDUCATION.

ON CERTIFICATION FROM THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR MOODY, ET AL., AND WILLIAMS, ET AL.

Conrad 0. Pearson

2031/2 E. Chapel Hill Street

Durham, North Carolina

Thomas T. Clayton

307 W. Franklin Street

Warrenton, North Carolina

Of Counsel

A lbert J. Rosenthal

435 West 116th Street

New York, N.Y. 10025

J. LeVonne Chambers

Robert Belton

East Independence Plaza

951 S. Independence Blvd.

Charlotte, North Carolina 28202

Jack Greenberg

James M. Nabrit, III

Norman J. Chachkin

Morris J. Baller

Barry L. Goldstein

Joseph P. Hudson

10 Columbus Circle

Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

Attorneys for Moody, et al., and Williams, et al.

I N D E X

PAGE

Opinions Below ...................-............................................. 1

Jurisdiction ........ ....... ... .......................................—-....... 2

Statutory Provisions Involved ............. 2

Question Presented .......... 3

Statement .......................................... 3

Argument ........................................................................ 6

I. The Language and Legislative History of the

Applicable Provisions Exclude Senior Judges

From Voting ........... 6

II. Compelling Policy Reasons Deriving From The

Purpose And Nature of EnBanc Hearings, The

Status of Senior Judges, And The Need For

Consistent Appellate Practice Support The

Plain Language of The Statute and Rule ....... 10

1. The Purpose of En Banc Hearings and the

Status of Senior Judges ............................... 10

2. The Policy of Uniformity ........................... 13

Conclusion................... 17

Appendix A—Certificate of the United States Court

of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit....... A -l

Appendix B—Results of Survey of Practices in the

Various Circuits ..................................... B-l

11

T able of A uthorities

Cases: page

Allen, v. Johnson, 391 F.2d 527 (5th Cir. 1968) ......... 12,15

Griggs v. Duke Power Co., 401 U.S. 424 (1971) ........ 3

Idlewild Bon Voyage Liquor Corp. v. Epstein, 370 U.S.

713 (1962) ........... 13

Moody v. Albemarle Paper Co., 474 F.2d 134 (4th Cir.

1973) .............................................................................. 1,4

Shenker v. Baltimore & Ohio R. Co., 374 U.S. 1 (1963) 14

Textile Mills Security Corp. v. Commissioner, 314 U.S.

326 (1941) .............. 6

United States v. American-Foreign Steamship Corp.,

363 U.S. 685 (1960) .....................................7,10,11,14,16

Western Pacific Railway Corp. v. Western Pacific

Railway Co., 345 U.S. 247 (1952) .......... .................. 14

Williams v. Albemarle City Board of Education, 485

F.2d 232 (4th Cir. 1973) ............................................. 2,4

Zahn v. International Paper Co., 469 F.2d 1032 (2nd

Cir. 1973), aff’d on merits 94 S.Ct. 505 (1973) .......15,16

Statutes and Rules:

28 U.S.C. §43(b) ............................................................ 11

28 U.S.C. §46(c) .............. 2, 3, 6, 7, 8, 9,10,12,13,14,15,17

28 U.S.C. §294(c) .......................................................... 11

28 U.S.C. §295 ..................... 12

Ill

PAGE

28 U.S.C. §1254(3) ......................................................... 2

28 U.S.C. §1292(b) ............ ............................. ............... 13

28 U.S.C. §2284 ............................. ................................. 13

42 U.S.C. §1983 .................. ............................................. 3

42 U.S.C. §2000e et seq., Title VII, Civil Eights Act

of 1964 .................................................... ,....................... 3

Federal Buies of Appellate Procedure, Rule 35 .....2, 3, 7, 9,

12,13,15,16,17

Rule 35(a) ........................... 9

Rule 35(b) ........................................................ 9

Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure, Rule 4 7 .......... 16

P.L. 88-176, 77 Stat. 331, “Judges—Status After

Retirement” (1963) .............. ................................... .

Other:

Advisory Committee Note to F.R.A.P. Rule 35, 43

F.RD. 61 (1967) ...................................... ...... ......... . 9

House of Representatives Report No. 95, 88th Cong.,

1st Sess. (1963) .............. 8

Note, En Banc Hearings in the Federal Courts of Ap

peals: Accommodating Institutional Responsibilities,

40 N.Y.U.L. R ev. 562 (1965) ........ ......... ..................... 11

Senate Report No. 596, 88th Cong., 1st Sess. (1963) .... 8

United States Code Cong. & Administrative News, 88th

Cong., 1st Sess. (1963) 8

IV

United States Court o f Appeals Local Rules page

First Circuit Rule 1 6 ................................................ 14

Third Circuit Rule 2(3) .............. ............................ 15

Eighth Circuit Rule 7 ...................................... ....... 15

Ninth Circuit General Order No. 15 .......... ...... ...... 15

I n the

B upm n? QJmtrt rtf tljr flutters Stairs

October T erm , 1973

No. 73-899

J oseph P . M oody, et al.,

—vs.—

A lbemarle P aper Company, et al.

B axter K. W illiams, et al.,

—vs.—

A lbemarle City B oard of E ducation.

on certification from the united states court of appeals

FOR THE FOURTH CIRCUIT

BRIEF FOR MOODY, ET AL.,

AND WILLIAMS, ET AL.

Opinions Below

The opinions of the Court of Appeals for the Fourth

Circuit are as follows:

1. The opinions of the panel in the Moody action, en

tered February 20, 1973, reported at 474 F.2d 134.

2

2. The opinion of the panel in the Williams action, en

tered October 1, 1973, reported at 485 F.2d 232.

3. The Certificate of the Court of Appeals, filed Decem

ber 6, 1973, unreported. (The Certificate is set out in the

Brief Appendix, A. 1-2.)

Jurisdiction

The Certificate of the Court of Appeals was entered on

December 6,1973. The jurisdiction of this Court is invoked

pursuant to 28 U.S.C. §1254(3). On January 14, 1974, this

Court granted leave to, and invited the parties to, file briefs

on the certified question on or before February 13, 1974.

Statutory Provisions Involved

This matter involves 28 U.S.C. §46, which provides, in

relevant part, as follows:

(c) Cases and controversies shall be heard and

determined by a court of not more than three judges,

unless a hearing or rehearing before the court in banc

is ordered by a majority of the judges of the circuit

who are then in regular active service. A court in banc

shall consist of all circuit judges in regular active

service. A circuit judge of the circuit who has retired

from regular active service shall also be competent

to sit as a judge in the rehearing of a case or contro

versy if he sat in the court or division at the original

hearing thereof.

The case also involves Rule 35 of the Federal Rules of

Appellate Procedure, which provides in relevant part:

(a) When Hearing or Rehearing In Banc Will Be

Ordered. A majority of the circuit judges who are in

3

regular active service may order that an appeal or

other proceeding he heard or reheard by the Court of

Appeals in banc. Such a hearing or rehearing is not

favored and ordinarily will not be ordered except (1)

when consideration by the full court is necessary to

secure or maintain uniformity of its decisions, or (2)

when the proceeding involves a question of exceptional

importance.

(b) Suggestion of a Party for Hearing or Rehearing

In Banc. The clerk shall transmit any such suggestion

to the judges of the court who are in regular active

service but a vote will not be taken to determine

whether the cause shall be heard or reheard in banc

unless a judge in regular active service or a judge who

was a member of the panel that rendered a decision

sought to be reheard requests a vote on such a sug

gestion made by a party.

Question Presented

The question certified by the Court of Appeals for the

Fourth Circuit in these cases is:

Under 28 U.S.C. §46 and Rule 35 of the Federal Rules

of Appellate Procedure, may a senior circuit judge, a

member of the initial hearing panel, vote in the deter

mination of the question of whether or not the case

should be heard en banc?

Statement

A. The Moody case is a class action attacking systemic

practices of racial discrimination under Title YII of the

Civil Rights Act of 1964, 42 U.S.C. §§2000e et seq. The

case arose at a paper manufacturing mill, and centers on

4

allegations that the defendants engaged in employment

discrimination by utilizing unnecessary testing and edu

cational requirements and maintaining a “lock-in” seniority

system. The plaintiff class seeks injunctive relief and a

compensatory back pay award.

The district court found discrimination in the seniority

system and the educational requirements, but held the

testing program lawful under Griggs v. Duke Poiver Co.,

401 TJ.S. 424 (1971), and denied back pay in the exercise of

its discretion. On appeal, a panel of the Fourth Circuit

consisting of Judge Craven and Senior Judges Boreman

and Bryan reversed the district court’s testing ruling, find

ing the testing program not demonstrably job-related, and

also reversed the denial of back pay, holding that the trial

court’s discretion had been abused. 474 F.2d 134.

On June 25, 1973 the Court of Appeals granted the

defendants’ petitions for rehearing and ordered rehearing

en banc. After filing of supplemental briefs by all parties,

the Court en banc, including Judges Boreman and Bryan,

heard oral argument on October 2, 1973. The problem

raised by the Certificate intervened before any decision of

the en banc Court on the merits could be reached.

B. Williams, a black high school principal’s employment

discrimination action brought under 42 U.S.C. §1983, arose

in the context of the desegregation of a dual school system.

The plaintiff lost his job during the desegregation process.

The district court found that he had suffered racial dis

crimination, and the panel of the Court of Appeals, includ

ing Senior Judge Bryan, affirmed.

The panel, however, vacated the trial court’s back pay

award to plaintiff. The panel based its decision, entered

October 1, 1973, on the duty to mitigate damages, and con

strued that duty to require acceptance of a demotion. 485

5

F.2d 232. A petition for rehearing, with suggestion for

rehearing en banc, has been filed by the plaintiff. This

petition is being held in abeyance pending resolution of

the certified question.

C. The Certificate indicates that a majority of judges

in regular active service voted against rehearing the Moody

matter en banc, but that with the inclusion of the votes of

the two senior judges who sat on the panel, a majority of

the votes were counted in favor of rehearing en banc. (A.

I ).1 The Certificate further indicates that if the en banc

Court reaches the merits, it will probably modify the panel’s

decision regarding back pay (Id.). With respect to

Williams, the Certificate states that a majority of the judges

in regular active service favor granting a rehearing en

banc, but if the vote of the Senior Judge who sat on the

panel is counted the en banc rehearing will be denied by an

equal division of the judges (A. 1-2). The Court of

Appeals has not ruled on the suggestion for rehearing en

banc, pending resolution of the certified question (Id.).

The facts or merits of the two cases are in no way in

volved in the resolution of the issue framed by the Certifi

cate. It is nevertheless apparent that the Fourth Circuit’s

resolution of the back pay issue in both cases will turn on

the answer to the certified question (A. I ).2

1 Citations in this form are to pages of Brief Appendix A. Cita

tions in the form “B. — ” are to Brief Appendix B.

2 If the question is answered in the negative, the Moody panel

decision would apparently stand, since the en banc Court would

have been improperly convened; and in Williams the district

court’s decision would probably be affirmed by an equally divided

en banc Court. If the question is answered in the affirmative, or

the Fourth Circuit’s custom allowed to apply, the Moody panel

decision would be modified and the Williams panel decision would

stand.

6

ARGUMENT

Senior Circuit Judges, Although They May Sit On

An Initial Hearing Panel, Are Not Entitled To Vote

On The Determination Of Whether A Case Should Be

Heard En Banc.

I.

The Language and Legislative History of the Ap

plicable Provisions Exclude Senior Judges From Voting.

Section 46(c) of the Judicial Code, Title 28 U.S.C.,

controls the practice here in question. On its face, the

first sentence of 28 TJ.S.C. §46(c) states that only “ circuit

judges of the circuit who are in regular active service”

are competent to vote on a suggestion of rehearing en tone.

Congress did not, however, simply fail to turn its atten

tion to the role of Senior Judges in en banc proceedings.

The third sentence of §46(c), concerning participation on

rehearing en banc once the rehearing has been granted,

specifically provides for inclusion of a “ circuit judge of

the circuit who has retired from regular active service . . .

[who] sat in the court at the original hearing thereof.”

Other than the power to participate once rehearing has

been ordered, the statute gives no other power to Senior

Judges.

The legislative history of §46(c) supports this plain

reading of the statutory language. The present Section

is the result of a 1963 amendment of the previous provision,

which dated from the 1948 revision of the Judicial Code.

The 1948 statute had clarified the Courts of Appeals’ power

to constitute themselves en banc, by legislatively adopting

Textile Mills Security Corp. v. Commissioner, 314 U.S.

326 (1941). It did not explicitly address the question of

7

the role of Senior Judges upon rehearing. A decision of

this Court thereafter construed §46 (c), as it then read, to

preclude the participation of Senior Judges as part of

the Court en banc, once rehearing en banc had been or

dered, even where the Judge had been a member of the

initial panel (and had retired following the panel decision).

United States v. American-Foreign Steamship Corp., 363

U.S. 685 (I960).3 In that opinion, this Court openly invited

Congress to change that result legislatively, 363 U.S. at

690-691. In 1963, Congress enacted P.L. 88-176, 77 Stat.

331, “Judges—Status After Retirement” , “An Act to clarify

the status of circuit and district judges retired from

regular active service” . The enactment amended, inter

alia, §46 (c), modifying slightly its then-existing two sen

tences, and adding a third which changed the American-

Foreign result by providing for participation of Senior

Judges of the Circuit who had sat on the panel, once the

en banc rehearing is ordered.

It is significant that Congress examined and slightly

redrafted the first sentence, which states the conditions

upon which en banc rehearings may be ordered, without

3 In American-Foreign, this Court held squarely that where a

determination was committed by law to a majority of active judges,

a Senior Judge might not participate in it, whether or not he had

been a member of the panel. While the precise ruling of that case

—that such a Senior Judge could not vote in rendering an en banc

decision once rehearing by the full court had been ordered—has

been changed by Congress, there has been no similar legislative

change in the provision applicable to the question certified herein.

Indeed, the commitment, to active judges only, of the power to

decide whether to have an en banc hearing or rehearing has been

reaffirmed by Rule 35, Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure

(1967). See p. 9, infra. American-Foreign is clear authority

that where the law prescribes “ active judges” , Senior Judges may

not participate— and that is precisely the question raised by the

Certificate herein.

8

mentioning Senior Judges.4 The purpose of the 1963

amendment of §46(e) was only to “permit such a [Senior]

Judge to sit on a rehearing en banc of a case where he

participated at the original hearing thereof,” and spe

cifically to reverse American-Foreign. S. Rep. No. 596,

88th Cong., 1st Sess.; H.R. Rep, No. 95, 88th Cong., 1st

Sess. (1963), reprinted in U.S. Code, Cong. & Administra

tive News, 88th Cong., 1st Session, pp. 1105-1106.5

The purpose of P. L. 88-176 was not to effect a general

reform of judicial practice regarding rehearings en banc,

but to clarify the status of Senior Judges. Other sections

dealt with such matters as the exclusion of Senior Judges

from participation in the appointment of officers of the

court, promulgation of rules of the court, and membership

in the judicial conference of the circuit. See S. Rep. No.

596, H.R. Rep. No. 95, supra. Clearly, the Congressional

intent was to delineate specifically what functions Senior

Judges might and might not perform. In this context,

the express language limiting voting on whether to order

an en banc hearing to judges “ in regular active service”,

but permitting Senior Judges of the circuit who had sat

4 Indeed, the change in language from “active service” to “regular

active service” was apparently intended to remove an ambiguity

as to whether a Senior Judge might still be regarded as “active” .

See the letter from the Administrative Office of the U.S. Courts,

included in the committee reports recommending adoption of P. h.

88-176, quoted in U.S. Code Cong. & Administrative News, 88th

Cong., 1st Sess., p. 1107. The additional word made clear that

irrespective of their service on panels, Senior Judges were not to

be regarded as “active judges” and therefore not to be included

among those who could vote on whether to rehear a ease en banc.

6 The same Senate-House report quoted here continues, shortly

after the cited passage:

It is believed that [a] Judge who has sat on an issue in an

appellate hearing on which a rehearing has been ordered

should be a member of the court for rehearing purposes. (Id.)

(emphasis supplied)

9

on the panel to participate in the decision if an en banc

hearing was ordered, reflects a line carefully drawn by

Congress.

The text of Rule 35, Federal Rules of Appellate Proce

dure, points with equal clarity to the same conclusion.6

Rule 35(a) provides for en banc sittings only when a

“majority of the circuit judges who are in regular active

service” so order. Rule 35(b) directs that the clerk, upon

receipt of a party’s suggestion of a rehearing en banc,

“shall transmit any such suggestion to the judges of the

court who are in regular active service” . The framers of

the Rule clearly intended thereby not to authorize Senior

Judges from the panel to vote on the question of whether

to convene an en banc court. This becomes plain from the

next sentence of Rule 35(b), which specifically allows

Senior [or other] Judges who sat on the panel to request

a vote on a party’s suggestion of en banc consideration.

Similarly, the Advisory Committee’s Note to Rule 35 states

that

The rule merely authorizes a suggestion, imposes a

time limit on suggestions for rehearings en banc, and

provides that suggestions will be directed to judges of

the court in regular active service.

43 F.R.D. 61, 153 (1967).

All the statutory provisions point to the same result :

Senior Judges may not participate in the determination of

whether a case will be heard or reheard en banc.

6 Rule 35, like the other Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure,

was not designed to modify or amend the substance of underlying

legislation such as §46 (c), but to implement it.

10

II.

Compelling Policy Reasons Deriving From The Pur-

Pose And Nature Of En Banc Hearings, The Status Of

Senior Judges, And The Need For Consistent Appellate

Practice Support The Plain Language Of The Statute

And Rule.

1. The Purpose Of En Banc Hearings and the

Status of Senior Judges.

Sound judicial policy dictates a negative answer to the

certified question. The principal purpose of providing for

en banc rehearing of panel decisions is to assure consistency

of the law within a circuit, or as this Court has put it,

To enable the court to maintain its integrity as an insti

tution by making it possible for a majority of its judges

always to control and thereby to secure uniformity and

continuity in its decisions.

United States v. American-Foreign Steamship Corp., supra,

363 U.S. at 689-690. This purpose is not served, and may

well he hindered, by allowing Senior Judges to participate

in the determination of when a panel decision is so out of

line with the views of the majority of the Court responsible

for its “integrity as an institution”—the active members

of the Court—that review by the whole court becomes

necessary.7

7 In American-Foreign the Court wrote that “ Congress may well

have thought that it would frustrate a basic purpose of the legis

lation not to confine the power of en banc decision to the permanent

active membership of a Court of Appeals,” 363 U.S. at 689. As

shown at pp. 6-8 supra, nothing in the text or legislative history

of the 1963 amendment to §46 (c) indicates that Congress had

changed its mind, with respect to the narrow issue posed by the

present Certificate.

11

The ongoing general responsibility for the judicial work

of the circuit is vested in the active judges.8 They have the

continuing duty to develop and apply the law in cases that

will be adjudicated in the future. This Court in American-

Foreign described active judges as being “those charged

with the administration and development of the law” , 363

U.8. at 689, and recognized approvingly that

the evident policy of the statute [old §46] was to

provide ‘that the active circuit judges shall determine

the major doctrinal trends of the future for their

court........’ 363 U.S. at 690

(quoting opinion in same case below, 265 F.2d 136, 155 (2nd

Cir. 1957). Circuit judges in regular active service also

are most directly aware of the problems of calendar con

gestion in the circuit, and are in the best position to

balance the burdens imposed on the time of additional

judges by an en banc hearing against the advantages of

establishing a clear and uniform rule for the circuit.9

In contrast, retired Circuit Judges do not exercise the

same continuing responsibility for the work of the Court

as a whole.10 The rationale for retired judges’ participation

8 28 U.S.C. §43 (b) states flatly, “ Each Court of Appeals shall

consist of the circuit judges of the circuit in regular active service.”

In contrast, §43 (b) provides that Senior Circuit Judges may

participate to a limited extent in the work of the circuit: “ [t]he

circuit justice and justices or judges designated or assigned shall

also be competent to sit as judges of the court.”

9 See also Note, En Banc Hearings in the Federal Courts

of Appeals: Accommodating Institutional Responsibilities, 40

N.Y.U.L. Rev. 562, 574 et seq. (1965).

10 See n. 8, supra. Senior Judges sit pursuant to 28 U.S.C.

§43(b) only when “designated or assigned” . A retired judge may

be “ designated and assigned” by the Chief Judge of the Circuit

“to perform such duties as he is willing and able to undertake”

pursuant to 28 U.S.C. §294(c). Section 294(c) provides, “No re

tired justice or judge shall perform judicial duties except when

12

at en banc rehearings of causes in which they sat on the

panel is significantly different from the rationale for the

en banc proceeding as a whole. Chief Judge Brown of the

Fifth Circuit has articulated the principal reason as “ the

benefit which the entire Court obtains from the prior work,

research, study and deliberation done by a Senior Judge

during his (and his two colleagues’ ) initial consideration

of the case.” Allen v. Johnson, 391 F.2d 527, 531 (5th Cir.

1968) j see also id. at 529. This rationale, however, comes

fully into play only after the decision to convene en banc

has been made, when the whole court addresses the merits

of the case before it with full deliberation.11

There is no general policy to the effect that all judges

who participate in a panel decision of a court of appeals

are necessarily to play a part in either the vote on whether

to order a rehearing en banc or the decision if such a re

hearing is ordered. Court of Appeals panels often include

district judges, circuit judges from other circuits, and

retired Supreme Court Justices, none of whom are au

thorized to play any further role in connection with any

subsequent en banc action. Thus, participation on a panel

designated and assigned.” From this statutory scheme, it is ap

parent that Senior Judges of the Circuit are not regarded as mem

bers of the court generally, but have a separate, limited status.

See also 28 U.S.C. §295 (assignment and designation of Senior

Judges to sit may be revoked).

11 Moreover, the advantages to be drawn from a Senior Judge’s

deliberations while on the panel are not cast away by his non

participation in the vote whether to convene the court en banc.

Section 46(c) nowhere limits, and Rule 35 specifically recognizes,

the authority of Senior Judges to recommend en banc proceedings

or to call for a vote of the active judges on such a suggestion. In

fact, the practice of most circuits appears explicitly to confer this

power on Senior Judges who were panel members. See Brief Ap

pendix B.

And of course, a Senior Judge who sat on the panel will always

participate in the vote on a petition for rehearing by the panel.

13

should not itself entitle a judge to participate in all further

proceedings on the case.12

2. The Policy of Uniformity.

The certified question is of general importance and

nationwide applicability.13 Congress has approved a

statute, 28 U.S.C. §46 (c), and this Court has promulgated

a Rule, F.R.A.P. Rule 35, which are national in scope and

call for uniform application.14 * * The basic issue as to the

composition of the Courts of Appeals in voting whether to

constitute themselves en banc should not be left to the

accidents of local custom or even, conceivably, to ad-hoc

determination by a succession of courts of changing com-

12 Differentiation between the judges designated to decide

whether a case is to be reviewed and the judges who decide on

the merits after review is granted is not uncommon in federal

judicial practice. One example is the requirement of 28 U.S.C.

§1292(b) that the recommendation of the district judge making

an interlocutory order not otherwise appealable is a prerequisite

to the discretionary power of the court of appeals to hear the

appeal. Another is the procedure required by 28 U.S.C. §2284 in

proceedings for an injunction against operation of a state statute.

A single district judge initially determines whether the action

requires a three-judge district court, Idlewild Bon Voyage Liquor

Corp. v. Epstein, 370 U.S. 713, 715 (1962); but once that judge

so rules, the Chief Judge of the circuit must designate the two

other judges to sit on the district- court. 28 U.S.C. §2284(1). And

in many state judicial systems, a lower court may grant leave to

appeal to a higher court.

13 As the Certificate recites, “Were the answer to the question

in each case of importance to the litigants only, the judges of the

Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit, sitting en banc, could

decide it, . . . The question, however, involves more than the rights

of the litigants, for the duties and responsibilities of some of the

judges of the court are in issue and relative powers of participation

are at stake.” (A. 2)

14 Indeed, these provisions have been applied uniformly by the

different Circuits—with the single exception of the Fourth. See

pp. 14-15, infra.

14

position.15 Uniformity of procedure in the appellate courts

on this point is both intended and desirable.

The Fourth Circuit’s local custom of allowing Senior

Judges who sat on the panel to participate in the determina

tion whether to hear the case en banc is inconsistent with

the practice of all the other circuits.16 The First,17

16 The line of decisions by this Court holding that the Courts of

Appeals should have authority to formulate and administer their

own procedural rules concerning rehearings en banc does not

imply otherwise. See, e.g., Western Pacific Bailway Cory. v. West

ern Pacific Railway Co., 345 U.S. 247 (1952) ; United States v.

American-Foreign Steamship Corp., 363 U.S. 685 (1960); Shenker

v. Baltimore & Ohio B. Co., 374 U.S. 1 (1963). The Western

Pacific decision, which fathered the line, specifically dealt with the

purely “house-keeping” functions of the Court of Appeals, 345

U.S. at 255-256. The Court there expressly stated that “ the full

membership of the court will be mindful, of course, that the statute

commits the en banc power to the majority of active circuit

judges. . . .” 345 U.S. at 261. That case and the following decision

in Shenker revolved essentially around the purely procedural

question of whether a litigant can dictate to an appellate court

what method it shall use to determine whether a majority of active

judges desire en banc consideration. (Specifically, the question was

whether each active judge of the court was required to vote on

the suggestion for en banc consideration.) The Court concluded

that the administrative machinery for determining whether a

majority of the active judges of the court favored an en banc

hearing was the appeals courts’ own “house-keeping” business,

as the 1948 Judicial Code Reviser had contemplated. It nowhere

questioned the assumption that the majority involved was of

active circuit judges only. The American-Foreign case had nothing

to do with the issue as to how an en banc hearing may be convened;

it dealt only with the competency of a retired judge to sit on the

rehearing en banc on the merits of the case. 363 U.S. at 688.

Moreover, the result in American-Foreign was specifically over

ruled by Congress in the 1963 amendment to 28 U.S.C. §46 (c).

16 Brief Appendix B summarizes the responses of the Courts of

Appeals to a polling by the undersigned counsel with respect to

their practice regarding the certified question. In some instances

the responses merely set forth answers given to counsel for Albe

marle Paper Company who apparently conducted a similar survey.

17 See First Circuit Local Rule 16, particularly 16(e) (B. 1).

15

Second,18 Third,19 Fifth,20 Seventh,21 Eighth,22 Ninth,23 24 25

and District of Columbia21 Circuits each follow a rule or

practice of not permitting Senior Judges to vote on this

question. The Sixth"5 and Tenth26 27 * Circuits have never had

occasion to consider the question and therefore have no

established practice. No other Circuit follows the Fourth

Circuit’s interpretation of §46 (c) and Rule 35.

Since eight other circuits have determined that section

46(c) and Rule 35 preclude the practice followed by the

Fourth Circuit,"7 this Court can serve the goal of uniformity

of practice as well as the intent of Congress by answering

18 See letter from Chief Deputy Clerk of the Second Circuit

dated January 31, 1974 (B. 1), and see Zahn v. International

Paper Co., 469 F.2d 1033, 1040-1041 (2nd Cir. 1973) (on petition

for rehearing en lane), aff’d on merits 94 S.Ct. 505 (December 17,

“ See letter from Chief Deputy Clerk of the Third Circuit

dated January 31, 1974; and see Local Buie 2(3) (B. 2).

20 See letter from Chief Deputy Clerk of the Fifth Circuit

dated January 31, 1974 (B. 2-3); and see Allen v. Johnson, 391

F.2d 527, 532 (1968).

21 See letter from Clerk of the Seventh

1974 (B. 4). Circuit, dated February 6,

22 See Eighth Circuit Local Rule 7, adopted effective July 1

1973 (B. 4). y ’

23 See Ninth Circuit General Order No. 15 and letter from Hon

Albert T. Goodwin (B. 4-5).

24 See letter from Clerk of the District of Columbia Circuit

dated January 25, 1974 (B. 5).

25 See letter from Clerk of the Sixth

1974 (B. 4).

Circuit, dated January 29,

26 Advice by telephone call from Clerk of Tenth Circuit to office

of undersigned counsel, February 11, 1974.

27 Indeed, the Certificate indicates that the practice of the Fourth

Circuit may not have been premised upon full deliberation. Its

“custom” , although “thought reasonable” , apparently had not been

subject to a “close examination” of §46 (c) and Rule 35 (A. 2)

16

the certified question in the negative. The Federal Rules

of Appellate Procedure adopted by this Court require such

an answer.28

For the reasons summarized above, it is clear that the

Fourth Circuit’s custom contravenes sound policies as to

the nature of the en banc process and the distinction be

tween active and retired judges, as well as the policy of

consistency in appellate practice.29

28 While the Fourth Circuit’s informal “custom” has not been

specifically included in its own rules, it should be noted that Rule

47 of the Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure permits local rules

“not inconsistent with these rules” . The Fourth Circuit practice

is clearly inconsistent with Rule 35. If it could not validly be

embodied in a formal rule, it can scarcely be permitted to stand as

an informal practice.

29 But even if the Fourth Circuit’s practice were desirable, it

would be contrary to present law. This Court has indicated that

change, if any, must come by statute, when it upheld the plain

meaning of the old, flawed §46 (c) as being correct although not

desirable in United, States v. American-Foreign Steamship Corp.,

supra, at 490-491. (After that decision, Congress addressed and

resolved the problem in an appropriate manner, see pp. 7-8 supra.)

Likewise, the dissenters in Zahn v. International Paper Co., supra,

n. 18, while not disputing what present §46 (c) means and vigor

ously expressing their dissatisfaction with that meaning, joined

the prevailing judges in calling for Congressional review of what

the latter described as “ its apparent inconsistency,” 469 F.2d

1041, 1042 n.l.

17

CONCLUSION

The Fourth Circuit’s practice is not reconcilable with

Rule 35 of the Federal Rules of Appellate Procedure or

with 28 U.S.C. §46(c), its history or purpose. This Court

should therefore answer the certified question in the nega

tive.

Respectfully submitted,

J. L eV on ne Chambers

R obert B elton

East Independence Plaza

951 S. Independence Boulevard

Charlotte, North Carolina 28202

J ack Greenberg

J ames M. Nabrit, III

N orman J. Chachkin

M orris J. B aller

B arry L. Goldstein

J oseph P. H udson

10 Columbus Circle

Suite 2030

New York, New York 10019

Conrad O. P earson

203% E. Chapel Hill Street

Durham, North Carolina

T homas T. Clayton

307 W. Franklin Street

Warrenton, North Carolina

Attorneys for Moody, et al., and Williams, et al.

Of Counsel

A lbert J. R osenthal

435 West 116th Street

New York, New York 10025

APPENDIX

A-l

APPENDIX A

Certificate of the United Slates Court of Appeals

for the Fourth Circuit

[caption omitted]

CERTIFICATE

The Judges of the United States Court of Appeals for

the Fourth Circuit, pursuant to the provisions of 28 U.S.C.

§1254(3), respectfully certify the following question to

The Supreme Court of the United States:

Under 28 U.S.C. § 46 and Rule 35 of the Federal

Rules of Appellate Procedure, may a senior circuit

judge, a member of the initial hearing panel, vote in

the determination of the question of whether or not

the case should be reheard en band

The question is of determinative importance in each of

the cases.

In Moody, two senior circuit judges were members of

the original hearing panel and participated in the decision.

Upon a suggestion of a rehearing en banc, each voted for

it. Though a majority of the judges in regular active ser

vice did not vote for an en banc rehearing, the votes of

the two senior circuit judges were counted providing a

majority of the counted votes in favor of rehearing en banc.

On that basis, a rehearing was ordered and held, the two

senior judges participating in the hearing as provided

in 28 U.S.C. § 46. If the en banc court reaches the merits,

the tentative vote is that it will modify the panel decision

with respect to an award of back pay.

In Williams, one senior circuit judge was a member of

the initial hearing panel. Upon a suggestion of a rehear

ing en banc, he is opposed. A majority of the judges in

regular active service is in favor of an en banc rehearing,

but if the vote of the senior circuit judge is counted, the

A-2

suggestion will fail by an equal division of the judges.

No formal order has been entered on the petition for re

hearing with a suggestion for rehearing en banc, because

the question of the right of the senior circuit judge to

vote arose. The panel had reversed an award of damages

by the district court, but if the voting on the petition for

rehearing is an accurate prediction, the en banc court, if

it reaches the merits of the appeal, probably would affirm

the district court by an equally divided court.

In the Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit, the

custom has been to count the votes of senior circuit judges

who were members of the initial hearing panel when the

court was polled on the question of en banc rehearing.

This was thought reasonable since the voting senior cir

cuit judge would be a member of the en banc court if re

hearing were granted. In earlier cases, however, the vote

of the senior circuit judge or judges was not crucial. The

fact that it is crucial in these two cases occasioned a close

examination of the statute and the rule, and a look at

Zahn v. International Paper Co., 2 Cir., 469 F.2d 1033,

1040-42, and Allen v. Johnson, 5 Cir., 391 F.2d 527, 532.

Were the answer to the question in each case of impor

tance to the litigants only, the Judges of the Court of

Appeals for the Fourth Circuit, sitting en banc, could

decide it, though in Williams v. The Albemarle City Board

of Education, there is a possibility of an equal division of

the court. The question, however, involves more than the

rights of the litigants, for the duties and responsibilities

of some of the judges of the court are in issue and relative

powers of participation are at stake.

The execution of this Certificate has been authorized by

the two senior circuit judges and by all of the judges in

regular active service.

s / Clement F. H aynsworth

Chief Judge, Fourth Judicial Circuit

B-l

APPENDIX B

Results of Survey of Practices in the

Various Circuits

First Circuit:

Rule 16. Petition for En Banc Consideration

Supplementing FRAP Rule 35, the following requirements

shall apply:

(a) Each application shall be submitted, with six copies.

(b) No application will be received until the ease has been

determined by a three-judge panel.

(c) No application will be granted if the panel’s decision

is unanimous, regardless of the number of opinions filed.

(d) No application will be granted unless one of the judges

on the panel approves.

(e) If application is granted, a senior judge will sit if, but

only if, he was on the panel.

(f) I f the application is granted, the ultimate decision will

be that of the majority of the active judges.

Second Circuit:

[Letterhead and inside address omitted]

January 31, 1974

Dear S ir:

In reply to the request contained in yours of January 29,

1974 received today, the practice in this court is not to per

mit the senior Circuit Judges who were members of the initial

hearing panel to vote when the court is polled on the question

of granting an in banc hearing.

The practice in this court is as Judge Mansfield stated in

his concurring opinion in Zahn v. International Papers Com

pany, 469 F.2d 1033, 1041, “ . . . that a senior judge who

heard an appeal as a panel member may not participate in

ordering it to be heard in banc, . . . . ”

Sincerely yours,

A. Daniel Fusaro

Clerk

/ s / V incent A. Carlin

by Vineent A. Carlin

Chief Deputy Clerk

B-2

Third Circuit:

Rule 2 (3)

Court and Divisions— Number of Judges to Sit— Court

In Banc. Cases and controversies are heard and determined

by a court or division of not more than three judges unless

a hearing or rehearing before the court in banc is ordered

by a majority of the circuit judges in regular active service.

The court in banc consists of all the circuit judges in regu

lar active service. A senior circuit judge of the circuit is

competent to sit as a judge of the court in bane in the re

hearing of a case or controversy if he sat in the court or

division at the original hearing thereof.

[Letterhead and inside address omitted]

January 31, 1974

Dear Mr. Mittelman:

Your letter of January 29, 1974, to Mr. Quinn has been

received during his absence from the office today. However,

since he just answered a similar question for an attorney in

Richmond, Virginia, I am forwarding you his statement in

that letter which was as follows:

“In this Court, the only votes counted where the question of

rehearing en banc is presented to the Court are the votes

of active circuit judges. Senior judges do not vote on the

question of rehearing en banc.”

Very truly yours,

/ s / M. Elizabeth Ferguson

M. Elizabeth Ferguson,

Chief Deputy Clerk

Fifth Circuit:

[Letterhead and inside address omitted]

January 31, 1974

En Banc Rehearings

Dear Mr. Mittelman:

Responding to the inquiry contained in your letter of Janu

ary 29, 1974 as to the practice of this Court of participation

by Senior Circuit Judges of the Circuit in polls on the ques

tion of granting an en bane rehearing, I am authorized by

B-3

the Chief Judge to advise that the practice in the Fifth Cir

cuit is that only active Judges of the Circuit participate in

the poll. However, if the case is put en bane, and a Senior

Judge of this Circuit sat as a member of the hearing panel

he would participate in the consideration of the case en bane.

Sincerely yours,

Edwabd W. W adsworth

Clerk

By / s / Gilbert F. Ganucheau

Gilbert F. Ganucheau

Chief Deputy Clerk

Sixth Circuit:

[Letterhead and inside address omitted]

January 29, 1974

Re : Bn Banc Rehearings

Dear Mr. Lowden:

This is in response to your letter of January 21, 1974,

regarding the practice in this court in considering sugges

tions for rehearing en banc in cases on which a Senior Circuit

Judge was a member of the original hearing panel. As I

understand your inquiry, you are specifically interested in

whether or not a Senior Circuit Judge who is a member of

the original hearing panel is entitled to vote in the determina

tion of the question whether or not the case should be reheard

en banc.

As I am sure you have already determined, the Sixth Cir

cuit has no rule regarding this question. Moreover, insofar

as I am able to determine, the question of whether a Senior

Circuit Judge who was a member of the initial hearing panel

is entitled to vote in the determination of the question whether

or not the case should be reheard en banc has never been

presented to or decided by the court. Accordingly, I would

have no basis for making any representation concerning the

court’s practice in this regard.

Very truly yours,

/s / James A. Higgins

James A. Higgins, Clerk

B~4

Seventh Circuit:

[Letterhead and inside address omitted]

February 6, 1974

Dear Mr. Mittelman:

In our Court the Senior Circuit Judge who was a member

of the initial hearing panel may request that a vote be taken

on a party’s suggestion that a rehearing be had in banc. How

ever, such Senior Circuit Judge may not participate in such

a vote if and when one is taken.

I know I answered this same question for another attorney

in the Moody case about two weeks ago. I cannot remember

his name, but it could be your opposing counsel.

Very truly yours,

/ s / Thomas F. Strubbe

Thomas F. Strubbe

Clerk

Eighth Circuit:

Rule 7. Hearing and rehearing in banc. A party or a

judge of this court in regular active service may suggest that a

case or controversy be heard or reheard in banc. A. majority of

the judges of this court in regular active service who are

actively participating in the affairs of the court and are not

disqualified in the particular case or controversy may order

a hearing or rehearing in banc. The panel for the hearing or

rehearing consists of the judges of this court in regular active

service who are actively participating in the affairs of the

court at the time of the hearing or rehearing and are not

disqualified in the particular case or controversy and the

senior circuit judges of this circuit who sat at the original

heai’ing thereof unless the senior circuit judges elect not to

sit at the rehearing in banc.

Ninth Circuit:

Practice in the Ninth Circuit is governed by General Order

No. 15—In Banc Hearings. This document, which is not a

published local rule, is lengthy and, to the undersigned coun

sel, somewhat unclear on the point in question here. It does

provide, in part—

“ 2. Panel recommendations for a rehearing in banc.

Should the panel to which a case has been assigned deter

mine, sua sponte, or upon consideration of a suggestion by

B-5

a party or of a member of the Court, or of a member of

the panel, that the case should be reheard in banc or that

the members of the court in active service should decide

whether the case should be so reheard, it shall:

(1) send a memorandum to the Chief Judge so advising

him, indicating why this course is appropriate, and should

provide him with a sufficient number of copies so that the

Chief Judge may distribute the memorandum to all mem

bers of the Court in active service; . .

Because this and other provisions of the General Order do

not indicate with certainty what the Ninth Circuit’s practice

is, the office of the undersigned counsel requested clarification

by the Honorable Albert T. Goodwin, Circuit Judge and In

Banc Expediter of the Ninth Circuit. Judge Goodwin sent

the following letter:

[letterhead and inside address omitted]

February 8, 1974

Dear Mr. Mittelman:

The practice of the Ninth Circuit is to allow Senior Judges

who sat on the original panel to request a rehearing in banc.

The vote on granting a rehearing is limited to the judges in

active service. If a rehearing is granted, a Senior Judge who

sat on the panel of decision is entitled to sit with the court

in banc and to record his vote, 28 U.S.C. §46(c), Gen. Order

15, Ninth Circuit Internal Operating Orders.

Yours very truly,

/ s / A lfred T. Goodwin

Alfred T. Goodwin

United States Circuit Judge

Tenth Circuit:

[No written response to this polling.]

District of Columbia Circuit:

[Letterhead and inside address omitted]

January 25, 1974

In R e : En Banc Rehearings

Dear Mr. Lowden:

Reference is made to your letter of January 21, 1974 in

quiring into this Court’s procedure with respect to suggestions

for rehearing en banc.

B-6

The practice followed by this Court is that a Senior Cir

cuit Judge of this Court, if he was a member of the original

three-judge panel, may call for a vote with respect to a

suggestion for rehearing en banc, but he can not vote thereon.

In the event a majority of the Judges of this Court in active

service vote for rehearing en banc, the Senior Circuit- Judge

can participate in the case with the en banc Court.

Sincerely yours,

/ s / H. Kline

Hugh E. Kline

Clerk

MEiLEN PRESS INC. — N. Y. C. « ^ j|s » 219