White v. Florida Hearing Transcript

Public Court Documents

August 21, 1969

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. White v. Florida Hearing Transcript, 1969. 1f3be5fe-c89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c4623ffd-f534-4ce2-b25f-c6cf122ac77f/white-v-florida-hearing-transcript. Accessed February 24, 2026.

Copied!

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

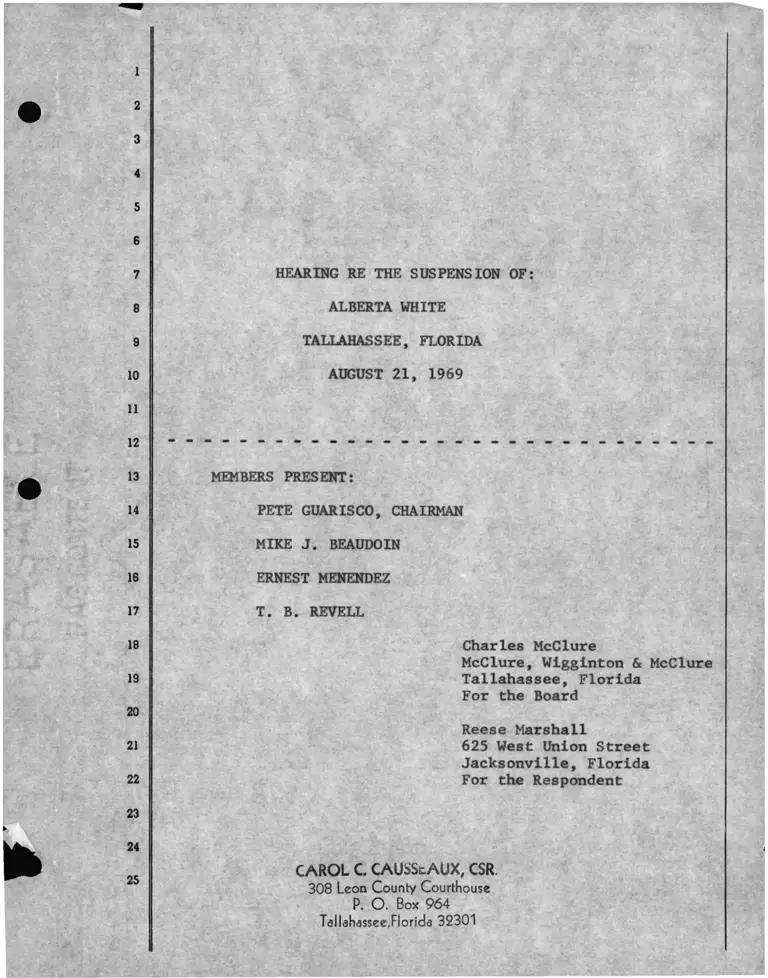

HEARING RE THE SUSPENSION OF:

ALBERTA WHITE

TALLAHASSEE, FLORIDA

AUGUST 21, 1969

MEMBERS PRESENT:

PETE GUARISCO, CHAIRMAN

MIKE J. BEAUDOIN

ERNEST MENENDEZ

T. B. REVELL

Charles McClure

McClure, Wigginton & McClure

Tallahassee, Florida

For the Board

Reese Marshall

625 West Union Street

Jacksonville, Florida

For the Respondent

CAROL C. CAUSScAUX, CSR.

308 Leon County Courthouse

P. O . Box 964

Tdllahassee,Florida 32301

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

NAME OF WITNESS

I N D E X

DIRECT CROSS REDIRECT RECROSS

JAMES N. TOOKS 19 53 76

E X H I B I T S

NO. & DESCRIPTION I.D. ADMITTED

1 - Notice to Mrs. White re hearing 18

2 - Notice of charges 18

3 - Notice from Mrs. White requesting hearing 18

4 - Cover letter from Supt. Ashmore 18

(Nos. 3 & 4 composite)

5 - Notice of hearing signed by Chairman 18

with cert, of service on Mrs. White 18

6 - Mrs. White's contract 18

7 - Supplement " 18

8 - Memo from Principal to teachers 23 36

9 - Letter to Mrs. White 41

10 - Evaluation of Mrs. White 42 45

11 - March 25 memo from Principal to Mrs. White 50 51

12 - Letter April 1 51

13 - Letter April 24 52

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

MEETING WAS CALLED TO ORDER BY THE CHAIRMAN AT THE

APPOINTED HOUR OF 10:00 O’CLOCK, A.M., AUGUST 21, 1969:

MR. GUARISCO: Are we ready to proceed?

MR. MARSHALL: Mrs. White is not here yet.

MR. GUARISCO: Let the record show that we are wait

ing for the respondent, Alberta White.

MR. McCLURE: Would it be appropriate for me to move

for a short recess?

MR. GUARISCO: Yes, sir, but as soon as she comes in

we will need to start the hearing. Let’s take a few min

utes recess here until she comes in.

MR. McCLURE: All right, sir.

MR. GUARISCO: While we’re waiting, why don’t you

gentlemen, for the benefit of the Court Reporter, intro

duce yourselves and proceed to that preliminary so that

it can be taken care of.

MR. MARSHALL: My name is Reese Marshall and I rep

resent Mrs. Alberta White in this cause.

MR. McCLURE: I am Charles McClure and I have been

retained to prefer the charges against Mrs. White and pre

sent them to the Board.

MR. GUARISCO: Mr. Marshall, would you give your

address for the record?

MR. MARSHALL: My address is 625 West Union Street,

Johnson and Marshall, Attorneys at Law, Jacksonville,

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

Florida, 32202.

MR. GUARISCO:

MR. MARSHALL:

MR. GUARISCO:

Mr. McClure, do you

MR. McCLURE:

I believe Mrs. White is here now.

May I have one further moment, please']

Yes, if you need a few minutes furthea

need a moment, also?

Yes. sir, I want them to study a dia

gram of the school.

MR. GUaRISCO: Let the record show that Mrs. Alberta

White has made her appearance here. This is a hearing

with the regard of the dismissal of Alberta White, 1112

Orange Avenue, Tallahassee, Florida. We will make part

of the record the notice of charges and I am sure counsel

will probably introduce those and also the notice of the

hearing which was mailed to the respondent. At this poin

then, with these preliminaries, Mr. McClure, are you

ready to present your case?

MR. McCLURE: Yes, sir, I am. I would like the

Board's permission for a brief opening statement and ther

the presentation of my case.

MR. GUARISCO: For the record, to make sure that we

can show that the Board members present are four, these

are Mr. Mike J. Beaudoin, Mr. Ernest Menendez, Mr. T. B.

Revell, Pete Guarisco, and the record will also show tha :

the Superintendent is also in the room representing the

the Executive Secretary, officer of the system,system as

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

Freeman Ashmore. Did you want to invoke the Rule, by the

way, before we get started?

MR. McCLURE: Yes, I would like to. I think it would

be a proper procedure at this time.

MR. GUARISCO: I think it’s fair to both sides if

you do invoke the Rule. Do you want to make the statement

now and then invoke the Rule after that?

MR. McCLURE: No, I would like to invoke the Rule

first.

MR. GUARISCO: Why don’t you get your witnesses to

gether and we will get the Reporter to swear them in and

invoke the Rule at this point and then proceed from there.

MR. McCLURE: All right, sir.

MR. GUARISCO: All witnesses that are going to appear

if you will come forward.

MR. McCLURE: Mr. Chairman, we have one witness who

will be coming in and who is at this point manning the

school, I believe, and is at another meeting. She will

be coming in later on.

MR. GUARISCO: All right, do you have any witnesses

at this time, Mr. iMarshall?

MR. .'1ARSHALL: No, but I would like to make an an

nouncement after the Rule is invoked to the Board.

MR. GUARISCO: Does anyone in the room here repre

sent anyone that you're going to use as a witness?

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

MR. MARSHALL: No, except, of course, Mrs. White.

MR. GUARISCO: The respondent is all right, but those

who are in here, once we invoke the Rule you can't use

them as witnesses.

MR. McCLURE: Mr. Chairman, Mr. Tooks is here and I

have asked .Mr. Marshall for a stipulation that he would

be able to remain here in the hearing room.

MR. GUARISCO: Do you stipulate to that?

MR. MARSHALL: Yes, sir.

MR. GUARISCO: All right, it is stipulated that

Mr. Tooks may remain in the room. All right, Mrs.

Causseaux, you may swear the witnesses and instruct them

as to the Rule.

(WITNESSES WERE SWORN AND PLACED UNDER RULE BY

REPORTER.)

.MR. GUARISCO: Sterling, you can make these people

comfortable in another room somewhere and perhaps you

can act as bailiff.

(WITNESSES WERE ESCORTED TO WITNESS ROOM.)

MR. MARSHALL: Mr. Chairman, I would like to move

for a continuance of this hearing because the witnesses

for Mrs. White, after my having contacted some twenty

persons, failed to appear because, in their mind, this

was an adversary proceeding and they were not clear as to

whether or not it would be ethical for them to appear b e

fore the School Board. All of them indicated that they

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

would like some reassurance from the Board that it is

proper and that they can appear and that they can give

testimony in this cause on behalf of Mrs. White. For tha

reason we only have one witness here today but there are

other names that we have and I can certainly furnish all

of those names to the Board and I would like for the

Board, in some form either formal or informal, to assure

them that it is proper for them to appear before this

Board and it is not an adversary proceeding in the sense

that the Board is moving against somebody as a defendant.

MR. GUARISCO: You are asking for a continuance for

the entire hearing?

MR. MARSHALL: Not for the entire hearing, no, but

for my - -

MR. GUARISCO: You mean for your side of the case?

MR. MARSHALL: Yes, for my side, yes, sir.

MR. GUARISCO: Well, that’s understandable, and I

think that request can be granted. If there is no objec

tion to that, we can proceed with the case that the Schoo

Board has and we can have a continuance for your side of

it. The motion is granted on that basis.

MR. McCLURE: Mr. Chairman, was this continuance for

another day this week or would it be for a specified timefi

MR. GUARISCO: I think we can arrive at a date here

before we get started now. We can select a date now,

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

and place, and proceed from there.

MR. McCLURE: Well, I did want to speak in oppositio

to the motion here.

MR. GUARISCO: Oh, you did, I’m sorry.

MR. McCLURE: Yes, sir, because I believe that the

notice was mailed out to Mrs. White on August the 8th and

the certificate of service shows that it was mailed on

that day to her through the United States mail and it is

the position of my client that they have had sufficient

notice to bring their witnesses before this hearing today

and that the plaintiff in this case is ready. There was

no prior notification of a motion for postponement and I

have gotten my witnesses here today. We have arranged

for them to be present and we have had no problem on get

ting witnesses and I think, without a prior motion being

filed, it would be an undue delay on the part of the

respondent here to ask for another continuance.

MR. GUARISCO: Your argument is well taken, counsel.

This hearing cannot go beyond 12:30 today due to prior

committment of members of the Board, so that we can allow

you to put on your case and if you are through, I think

Mr. Marshall can put the witness that he has heie on the

stand and then any continuance we might have would be in

respect to time running out, in which event we would have

to continue the case anyway. I agree with you that there

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

was ample notice and there is no excuse for the witnesses

not being here, but on the basis of the fact that we mighl

have to continue it for reasons other than the witnesses

not being able to be here, we can give them an opportunity

to bring them in at a later date. Now, we can get off th«

record and decide on a date and a time.

(DISCUSSION OFF THE RECORD.)

MR. GUARISCO: Let the record show that after 12:30

today the hearing will be continued to Saturday morning,

at 8:00 o'clock in the same room, the same place, and tha-:

both counsel have agreed that there will be no more con

tinuances for this case after today. You may proceed,

Mr. McClure.

MR. McCLURE: Members of the School Board, I would

like to make a few brief opening remarks to acquaint you

with what to expect will be presented today in support of

the charges for dismissal of Mrs. Alberta White, the

respondent. We are here today on a landmark decision in

Leon County. Your job, as members of the School Board,

is not a pleasant one; it's one that people would rather

not have, as a matter of fact, to prefer charges against

someone who has been in the school system for a long time

and prefer those charges in an attempt to terminate her

contract and terminate her services as a school teacher.

It's one, certainly, that the witnesses would rather be

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

someplace else than to be here to testify and certainly,

with the witnesses that we will call today as being con

temporaries of Mrs. White, fellow faculty members for one

or two years, and maybe even more. It's one that Mr. Took

the principal of Pineview Elementary School, certainly

doesn't like to bring up, but because of the responsibilit

and importance of this particular type of proceeding and

the effect not only that he has had in the past but would

be projected in the future if Mrs. White were allowed to

continue in teaching, the effect on our children is the

primary importance here today. It is not pleasant for

me to bring these charges, to draw them up, to interview

witnesses and to ask people to appear here and testify

today of the things they observed during the past two

school years, '67-'68 and '68-'69. It's not pleasant for

anybody, but the importance of this job is similar to

other jobs that juries have to maintain order in our

society and mairtain the peaceful community and to save

the taxpayers money. Today evidence will be introduced

that will attack the very competence of Mrs. White. She

has taught for nearly forty years, I'm told, in the

school system of our State but this evidence, some of it

will border on insubordination, neglect of duty, or in

competence. It's going to be embarrassing to have people

come up and testify to that. We don't like to do it but

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

we have a job to do. You will hear testimony that Mrs.

White couldn’t control her children in her classroom.

You will hear testimony that the children were even slip

ping out of her classroom while Mrs. White was there,

without any authority and without any purpose or any

place to go. You will hear testimony that Mrs. White

couldn't even stay awake in her classroom. These are not

pleasant things; the testimony will show that she went to

sleep, not on isolated instances, but on numerous occasio

throughout two school years, at least two school years,

and that she was so sound asleep in her classroom that

some of the fellow faculty members and secretaxies from

the school went to the door where Mrs. White's classroom

was, and, from the door, saw that she was asleep and call

her and walked all the way across the room to her desk

and called several times to her before she waked up.

These are not nice things to talk about but they are im

portant things to talk about. You will hear evidence tha

Mrs. White couldn't or wouldn't keep her room or her desk

straight or clean. For example, you will hear testimony

of old food wrappers and things like that on her desk

that were not just from a recent snack, but appeared to

be left there from several days. You will hear testimony

of papers on the floor. Now, everybody knows that childn

in grammar school, these children are going to have paper:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

and things dropping on the floor and we're not saying tha

teachers should have a custodial duty here in Leon County

They have a professional duty, but to offer a proper edu

cational climate in the classroom for the students, they

have to keep some order and maintain some sort of clean

liness there, but you will hear testimony that her desk

and her room were filthy and what sort of educational

climate is derived from that type of condition? You will

hear testimony that Mrs. White couldn't, or wouldn't fol

low directions and orders from her principal, Mr. Tooks.

These are very basic things, not technical things, but

very basic things that she could not or would not do.

You will hear testimony that there was no evidence of an̂

lesson plans in her classroom. What effect does this ha\

on a school day for elementary school children? You wil]

hear testimony that she wouldn't read any messages that

came from Mr. Tooks, her own principal; that when the

messages were sent to her by one of the secretaries, tha1

she would either sign them and not read them or just say,

"They say I'm not a teacher, anyway, so there's no use oi

my reading these messages". You will hear after a con

ference with Mr. Tooks, after a continued attempt by

Mr. Tooks to have Mrs. White correct these different

discrepancies, that she directly disobeyed his order not

to return to the classrodm and you will hear the circumsf

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

whereby Mr. Tooks - - I mean Mrs. White, that she was al

most in a state of hysteria; that she was crying and

screaming end hollering, and this is the reason Mr. Tooks

told her not to return to her classroom because of the

example and the emotional impact that it would have on

her students. You will hear testimony that she did, in

fact, return in this state to her classroom. You will

hear testimony that she failed to prepare any records or

any plans for field trips and you will hear the importanc

of this. Students need to have field trips and principal

need to have some sort of plans to show that the teacher

has planned field trips. You will hear evidence that

there was no physical evidence or documentary evidence

that she had even taken her children to the library. How

important is the library to students, to youngsters try

ing to learn, and trying to get ahead in this world?

You will hear evidence that there was no grouping of

students in reading level groups or capability groups

or any group at all, but that they were all sitting as

one great big classroom. You will hear evidence that

the children's work was not displayed on the bulletin

board and each of you knows the importance of a child

getting involved in their work and having something to

be proud of, no matter how simple or how complicated it j

They need to have something to show off and say that the}

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

IS

20

21

22

23

24

25

did it. You will hear evidence that there was none of th

displayed in Mrs. White’s classroom and you will hear

evidence that the very one program, an assembly program,

that she had during the past year at Pineview on Memorial

Day was completely disorganized; that there was no point,

that there was no organization, there was no follow throe

and the results of the program itself were just tragic,

more than anything else. You will hear the testimony tha

she continually sent a stream of students down to Mr. Too

office for things that she could have controlled herself

and that a teacher normally would control herself. No,

these things aren't pleasant to talk about, but these are

all things, that, lumped together, you must take into

consideration who are the losers. The children are the

losers; they are the ones that are not able to catch up

because they weren't properly oriented and programmed in

their schooling. We are here today to present the case

and you have, as your job on the School Board, to listen

to all the testimony and to make your decision of whethei

or not Mrs. White should continue in any capacity in the

Leon school system and continue teaching our youngsters

and our children and to continue setting the example of

what she has set in the past few years and what effect

this may have on the children in the future. Thank you.

MR. MARSHALL: Mr. Chairman, I would like to reserve

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

IS

20

21

22

23

24

25

my opening statement to the time when I put on my case.

MR. GUaRISCO: All right, Mr. McClure, are you ready

for your first witness?

MR. McCLURE: Yes, Mr. Chairman, but first, Mr. Mars

and I have stipulated on the introduction of certain docu

mentary evidence dealing with the chages and notification

of charges and the response from Mrs. White, and Mrs.

White's continuing contract and her supplement to her con

tinuing contract, and we have also stipulated to the inti

duction at this point of the record book showing the date

the charges were originally brought before the School

Board, which are contained or which were decided on July

of this year. I would like at this time, without any ob

jection, to submit to the Board these documents, the firs

being, as plaintiff's exhibit No. 1, and if you will help

me keep up with the numbers here, Carol, is the notice to

Mrs. White informing her of her right to a public hearinc

and her right to counsel and cross examination of witness

and, without objection, I would like to introduce that ir

evidence.

MR. GUARISCC: Let's call these County exhibits in

stead of plaintiff's exhibits. Let's make this County

Exhibit No. 1.

MR. McCLURE: And at the end of the hearing here I

would also like, and I think Mr. Marshall has agreed, tha

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

some of the documents which belong in Mrs. White’s per

sonnel jacket, could be removed from the hearing record

and copies substituted in there, and also the record book

could be substituted. This is the notice of charges

specifying that Mrs. White has been accused of neglect

of duty, incompetence and gross insubordination, with the

specification as to times and places of these charges,

and that would be County Exhibit No. 2.

MR. GUARISCO: You don't have any objection to Ex

hibits No. 1 and 2, do you, Mr. Marshall?

MR. MARSHALL: No, in fact I have already stipulatec

to the introduction of those.

MR. GUARISCO: That they could be introduced now?

MR. .MARSHALL: Yes.

MR. McCLURE: Thirdly is notification from Mrs. Whii

of her request for a hearing. Fourthly, and this probabi

should have been numbered earlier, but this is the cover

letter from Mr. Ashmore on the charges and if we could

make that a composite exhibit.

MR. GUARISCO: All right, I*ve marked 3 and 4 as a

composite.

MR. McCLURE: Next is the notice of hearing signed

by the Chairman with a certificate of service on Mrs. Wh:

MR. GUARISCO: That's 5.

MR. McCLURE: Next would be Mrs. White’s continuing

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

contract of employment. I have previously shown all thes

to Mr. Marshall.

MR. GUARISCO: Do you have copies now that you want

to submit?

MR. McCLURE: No, I don’t have them all. I have

copies of the contract and the supplement to the contract

MR. GUARISCO: You have no objection to substituting

the copies?

MR. MARSHALL: No, I have no objection.

MR. McCLURE: The next one is a supplement to her

contract, '68-*69.

MR. GUARISCO: All right, sir, that will be Exhibit

6 for the contract and Exhibit 7 for the supplement.

MR. McCLURE: At this point, the last thing is the

record book and I would like to read into the record the

book and page number. These are the official minutes of

the Board of Public Instruction. I furnished Mr. Marshal

with a copy of the page and I would like for the Board tc

take official notice of the time and the minutes of the

meeting contained in the book, Minute Book 9, beginning

at Page 475 and continuing on Page 476, as it relates to

this particular case, showing that the origination of the

charges by Mr. Tooksand the Board'oaction, showing the

members present at the Board to be a majority of the

Board and that the vote was unanimous on preferring the

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

charges. I would like to submit this for the Board to

take official notice of it.

MR. GUARISCOi Let the record show that the Minute

Book is here and available to the Board members and take

official notice of it and if you want to look through the

minutes now or at any time later you can do that.

MR. McCLURE: I have it marked with a piece of paper

I have other documentary evidence that I will introduce

as the testimony goes along here.

MR. GUARISCO: All right, let the record show, then,

that County Exhibits 1 through 7 are admitted into eviden:

County Exhibits 1 through 7

admitted into evidence.

MR. McCLURE: Mrs. Lavania Lackey is here and she

is the custodian of the files and I have no longer need

for her to remain. Her presence was merely to have her

introduce these but we have agreed that the documentary

evidence could come from the files and records of the

School Board.

MR. GUARISCO: Mr. Marshall, have you stipulated to

that?

MR. MARSHALL: That’s fine.

MR. McCLURE: I’m sure that Mr. Ashmore needs her

back at the office if it would be all right for her to

leave at this point.

MR. ASHMORE: Mr. Chairman, if she could be excused.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

IS

20

21

22

23

24

25

we are in the midst of compiling our new schedules and

things and there are many important matters to be attende

to in the office.

MR. GUARISCO: All right, we'll excuse her.

JAMES N. TOOKS

was called as a witness and having been sworn, was examii

and testified as follows:

DIRECT EXAMINATION

BY .MR. McCLURE:

Q Give the Board your name and address, please, sir.

A James N. Tooks, Principal of Pineview Elementary School,

3303 Wheatley Road.

Q And you say you are the principal of Pineview Elementary

School?

A Yes, sir.

Q Do you know the respondent, Mrs. Alberta White?

A I do.

Q Would you point her out to the Board?

A She is sitting to my left at the end of the table here.

MR. McCLURE: We would like the record to show that

he did point to Mrs. White.

Q How long have you been principal of Pineview Elementary

School?

A Since July 1, 1967.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

Q Have you ever been a principal before?

A Yes, I was principal of Barrow Hill School prior to assum

ing the principalship at Pineview.

Q All right, sir, and how about before that, were you a

teacher?

A I was a teacher at Barrow Hill one year prior to that tim =

Q How long have you been a principal, Mr. Tooks?

A I started teaching the school term of '56-'57 at Griffin

Junior High School, teaching mentally retarded children.

Q Now, I would like to refer you to the school term of 1967-

'68 and direct your attention, so we can bring out an

orderly presentation of the evidence here, and was Mrs.

White a teacher at Pineview Elementary then?

A Yes, sir, she was.

Q Where was her room at the time?

A (No response.)

W*. McCLURE: For the purposes of identification

here, and Mr. Marshall has agreed, Mr. Tooks has preparec

a diagram of Pineview Elementary School and I would like,

at this time, to have him testify as to where his office

is and where Mrs. White’s room is located.

Q For identification purposes, will you tell the Board

where you got that diagram and what it is of?

A This is a diagram of the floor plan of Pineview Elemental

School. This is the room assignment for the past school

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

IS

20

21

22

23

24

25

term. There were one or two changes - -

Ml. GUARISCO: I believe if you would take it to the

easel that it would be able to be seen by everyone.

Q All right, could you give us first the location of Mrs.

White's room?

A This is the school's office here and Mrs. White's room

is located here, or was located here during the '67-'68

school term. During the '68-'69 school term her room

was located here.

Q For the record would you identify where you office is anc

how many rooms are in between your office and Mrs. White'

room for the '67-'68 school term and the '68-'69 school

term?

A I am putting my finger on the exact location of my offic«

now.

Q All right, and where does that appear on the chart here?

A In the southeast corner here. There are two rooms betwee

the office and Mrs. White's room during the '67-’68 schoo

term, including a boys'and a girls’restroom.

Q All right, and what about the '68-*69 term?

A The boys' and the girls' restroom were the only existing

structures betweenmy office and Mrs. White's office.

Q All right, I would like to direct your attention - - and

you may be seated now (witness seated). I would like to

direct your attention to on or around November 11, 1967,

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

18

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

and have you testify as to what event happened with rela

tion to Mrs. White and your school plan for the school

year?

A During this time all teachers at Pineview were issued a

memorandum of the things in which I would be looking for

upon visiting their classes. The memorandum had referenc

to do with schedule of principal's official classroom

visitation. Each teacher at Pineview was given this. I

indicated to all teachers at that time, after this visit,

that I would have a personal conference with each of the

classes visited. Upon visiting Mrs. White's class, she

was in receipt of this memorandum.

Q Would you identify that memorandum, does it have a letter

head on it and someone's name?

A All right, this is a typical memorandum that I sent out t

all teachers from the school's office.

Q All right, and what is the subject matter of the memoranci

A The schedule of principal's official classroom visitation

Q Was one like this sent to Mrs. White, this memorandum?

A Yes, it was.

MR. McCLURE: I would like to show that to opposing

counsel here. (Document examined by Mr. Marshall.) With

out objection I would like to have it marked for identi

fication.

MR. GUARISCO: That will be marked as Exhibit 8 for

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

identification.

County Exhibit No. 8 sub

mitted for identification.

Q And do you also have a classroom visitation check list?

A The checklist corresponded with the items that I observec

or did not observe in the classroom. This, of course, I

went through with each teacher here.

MR. GUARISCO: Is this a composite or will this be

individual exhibits?

MR. McCLURE: Well, without objection, I would like

to introduce it as a composite because they relate to th<

same thing.

Q Does this show a name of the teacher?

A Yes, it does.

Q Who does it show?

A Mrs. A. White.

Q All right, and where did you get that form from?

A This form was developed at Pineview School.

Q Is this the form that appears in Mrs. White's jacket at

your school?

A Yes, it did.

MR. McCLURE: All right, I would like to have this

marked as a composite exhibit.

MR. GUARISCO: All right, this is part of the County

Exhibit No. 8 for identification, a composite.

Q Mr. Tooks , I would like for you to tell the Board in youh

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

own words what you did insofar as Mrs* White and what you

observed in the classroom after receiving notification,

and I would like for you to explain to the Board where

this form came from, who agreed on it, and go through the

form and explain, item by item, what you expected and

what you found.

aA The form itself was/result of several years experience

as a principal observing certain things in the classroom

and listening to the teachers and the comments that they

would make and I would suggest at this point that the

entire instrument, as a composite of feelings and expres

sions of teachers and the type of things they would like

to be informed about prior to a principal's official visi

Q Was this form decided on by the teachers at Pineview

Elementary or did they assist in making it up?

A A committee of teachers did, yes.

Q All right, go ahead and explain your classroom observatio

at that time and the date of it.

A Well, the first thing that’s listed here, the first ques

tion asked is whether or not lesson plans, since the be

ginning of the school term, were present in the classroon

There was no indication of this. It’s reasonable to ex

pect that there is a tremendous amount of spontaneous

learning going on in a class but you would not expect all

of it to be spontaneous.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

Q You didn't find any lesson plans?

A None were presented to me when I walked into the classroo

and, of course, I would assume, inasmuch as all teachers

had this form, that I had specifically stated that I want

certain things in a particular area when I walked into th

classroom so that I would not have to disturb the teacher

while teaching. These are the things that were not there

the lesson plans. I did not see any samples of the

childrens' work. I did not see any evidence of grouping

other than the fact that the entire class was sitting to

gether as a body.

Q Why is it necessary to have grouping?

A Well, I think just because - - we believe that children

are different and they learn at different rates. Their

interest span is different and we can see that when the

bell rings all children are not ready for math and all

children are not ready for social studies and all childr*

are not ready to eat, so it's reasonable to expect that

the different interest levels of children would vary so,

therefore, we need to meet the needs of the children.

This is especially so in the area of reading. We need tc

think in terms of different levels that children read on

and provide the individual interest and the individual

teaching procedures and this, of course, could not be

carried on when students were sitting together as a body

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

The next four or six items on here related to things in

which were not necessarily present in the classroom. I

did not make any comment, whether they were existing yes

or no, because these records were available in the libra

or other places. For instance, with regard to the film

strip and records - -

HR. MARSHALL: Excuse me, Mr. Chairman, but I'm ha1

difficulty following this, Mr. Chairman, and is it my

understanding that this is offered in evidence or - -

MR. GUARISCO: This is for identification purposes

at this point.

MR. McCLURE: I do plan to introduce it into evidenc

after he has finished his testimony.

MR. GUARISCO: This is still introduced as an exhibi

for identification at this point. Just identify the iten

and explain what it stands for, that item.

Q All right, continue now.

A Item 4,"Records in your class, number and names of film

strips used since opening of class," and this, of course

I did not indicate on the check list that she should

direct her attention to because this information was

available in the library. Item b,"Names and places of

field trips,list of places planned for the rest of the

school term." This, of course, I did not see in the

classroom and I did not indicate it on the classroom

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

visitation check list because duplicate copies of these

are available to me in the office. Item b, "Names of

parents visited this school term." This, of course, was

not present neither was it presented to me. This infor

mation also is available to me in the office. No. 7,

"The number of times and dates the class visited the

library." This she was not checked on in the evaluation

check list, the classroom visitation check list.

Q Did you find any evidence of her class visiting your

library?

A No, I did not.

Q All right, continue.

A No. 8, "The number and name of library books read by

students in the classroom." This, of course, was not

present at that particular time and, of course, it is not

checked on the evaluation check list. Now, with regard

to the type of things I felt really reflected learning

in the classroom, I underlined evidence of children's

art work as no, that I did not see that at this time and

there had not been any indication that it had gone on as

of the 20th of November of '67.

Q All right, why is it important to have children's art wor

A I think that as a result of children working and express

ing themselves through the art media they get a chance to

relieve their inhibitions and get a chance to develop

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

their finger dexterity by using the finger paint, using

paste, being able to do things in three dimensional. This

develops a self-concept and at the same time it develops

their concept of the world around them. Then No. 10,

"Evidence of the classroom illustrating orderliness, good

taste and systematic procedure."

Q Would you explain what you would expect on that?

A Well, I don't expect chaos; I don’t expect regimentation;

I do think that children can be busy going about their

classroom and be engaged in meaningful activities and

experiences without feeling as though they are restricted

from moving.

Q And what did you find?

A I found children going about doing this - - some children

were working math problems out of work books. She was

sitting to the desk. One or two were reading comic books

and this sort of thing. The classroom, of course, was

disarrayed.

Q Would you go into detail as what you best recall about it

being in disarray?

A In my way of thinking there is a systematic way of

disorder. You can look at a person's desk and you can sej

that a person is busily engaged in something constructive.

You can look at the desk and you can also see a lack of

organization that they can't really put their hands on

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

anything because they don't know where it is.

Q What did you find on Mrs. White's desk, if anything?

A Quite a bit of paper, the desk was very dirty, food wrapp

and candy wrappers. I can't say it was hers and I don't

know whether it belonged to the kids, but it was there.

Q It was on her desk?

A Some was on her desk and some of this was on the work

tables in the classroom and this sort of thing.

Q When you say that the desks in her room were dirty, what

do you mean by that? What did you find on the desk or in

the room that would make it dirty?

as

A Such things/ broken chalk on the floor that certainly had

not been there for just that - - it had been there for a

period of time. The papers that were crumpled and paste

isand watermarks, this^/the general impression that I had.

Q Are these the type things that teachers are normally ex

pected to correct or is that a janitorial service that

the cleaners are supposed to keep up?

A Well, we don't want to have teachers doing custodial work

but we certainly want them to involve children in trying

to keep their surroundings clean. I don't mean they have

to take a broom every thirty or forty minutes during the

day or every ten or fifteen minutes during the day, and

sweep, but they certainly ought to provide them with some

housekeeping chores. I think this is a vital learning

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

experience that teachers can provide for children. In

many instances the custodians are available on the school

grounds and many times are engaged in other things, but I

don't think the students and teachers need to sit back

and wait for them to do it. If a teacher can’t get this

done, certainly the children on the fourth or fifth grade

level really get a big kick out of doing this type of

thing.

Q All right, and what grade was Mrs. White teaching in 1967-

A She was teaching fifth grade then.

Q What sort of educational climate does a room in Mrs. Whits

condition create for the children?

A Well, I didn’t think that it created much of an educations

climate at all. I was convinced that, in spite of perhaps

something she had to offer the children, I felt that

teaching wasn't it.

Q All right, go ahead and continue with your items there

and calling out the numbers, if you would.

A Well, 11 I think we have just explained, "Evidence that

your room and facilities are properly cared for." No. 11,

"Evidence that work was evaluated and returned to pupils.'

MR. MARSHALL: I'm sorry, but could you give me

No. 11; I was on 10.

A "Evidence that your room and facilities were properly

cared for." Then we go to No. 12, "Evidence that you

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

evaluated and returned all work that pupils are required

to turn in."

Q All right, and what were your results of the finding in

that?

A This, of course, I have a Mno"check which means that I did

not see any evidence of this.

Q All right, go ahead.

A 13, "Your personal appearance", and I have "no" here be

cause it was certainly, in my opinion, unsatisfactory.

Q Could you go into detail on that because this is a very

important thing here. Why should personal appearance be

an important part of a teacher's duty?

A I think a teacher represents something to kids that many

of them, perhaps, don't get from other people. I don't

think they have to come dressed as if they were going to

a White House steak dinner but certainly they need to

come attired pleasant, appealing, not, of course, sugges

tive, either, but something that children can look at and

admire. I don't think that it would be appropriate for

me to wear Bermuda shorts or a teacher to wear slacks.

Neither do I think that it is proper for a teacher to

have on dresses that have been worn for a period of time,

dirty. I know that teachers and ladies in many instances,

because they get out of cars, they have a run in their

stocking, but I don't think this should happen every day.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

I think that their shoes should be shined sometime if

they are going to have those types of shoes that need to

be shined. I think that their B.O. should be pleasant so

that children can be happy to be around them and if this

is unpleasant the children certainly don’t get any love

and affection out of a teacher that they can’t enjoy

smelling.

Q All right, go ahead and continue.

A 14, "Evidence of a warm and friendly relationship with

your pupils."

Q What were the results of your findings and would you ex

plain this to the Board, what that means in your mind?

A I guess like much of us, it is debatable. On one hand it

may be yes and on the other hand it may be no. If you

are concerned bout the type of thing that is really good

for the children, that is. I recall on one morning about

7:30 Mrs. White had a group of children in her room and

it had been reported to me that there had been modern

dancing, not modern creative dancing, of course, but

modern dancing with the up-beat tempo. That was 7:30 in

the morning. I turned on the intercom and I happened to

have got a good ear of this and I said to her over the

intercom that I was enjoying the music. So she came to

the office and said to me, "Oh, you are, I have spent a

great deal of money buying these type of records and the

children love them." I think she missed my point.

Were you, in fact, enjoying the music or were you trying

to make a point in this way?

I was trying to make a point, very hard, that I was not

enjoying the music, and apparently it was not understood

that way. But I did go back to her on another occasion.

Perhaps at that time I indicated to her that this was not

the type of thing that ought to be going on in school, not

at 7:30 in the morning.

Do other teachers play this type of music?

It was never reported to me and I never heard it over the

intercom, nor did I ever see it.

All right, let me direct your attention back to this forrr

here and ask you to go ahead with that.

Well, in this instance perhaps it would be a friendly

relationship for the kids for them to dance if they

wanted to dance, but it was not that way with me. I did

not think that this would be a warm and friendly relation

ship. I guess there are standards that you have, intan

gible standards that an individual would have to have in

dealing with children. This is a good example, I guess,

of any. Perhaps there are standards that she had that

did not dictate to her that there was nothing wrong with

this. Perhaps these feelings transferred over into other

things.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

Q Go ahead and continue.

A 15, "Indication of classroom enthusiasm." I have that

checked "no" because I did not see enthusiasm.

Q What sort of enthusiasm would you expect to see?

A Well, children excited and eager to learn; children who

want to participate in class discussions and children who

want to talk about their experiences; children who are

happy to be in school and children who are happy to be in

a particular classroom.

Q You did not observe this when you were in the classroom?

A No, I did not observe it then, I did not observe it prior

to then and I did not observe it subsequent to that time

Q All right, then this was not just an isolated instance.

This, in your opinion, was over a period of time?

A Over a period of time and this is still my opinion.

Q All right, continue, please.

A 17, "Evidence of students'progress in fundamental knowlec

skills, abilities, attitudes, and appreciation of reading."

17 I checked "no", because I did not see any evidence of

children's progress in fundamental knowledges and skills

and their understanding and concept and appreciation of

reading. If so, then we would seen an appreciable degree

of students participating in reading activities, going tc

the library, checking out books, and this we did not see

Q All right, go ahead, sir.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

A 18, "The following schedules posted on your bulletin board

in your classrooms! 1, grade level; 2, classroom; 3, musi:

4, P.E.; 5, speech schedule." This was not there and hers

again, this would indicate the fact that the absence of

the schedule - - the absence of these schedules would in

dicate that children who would be scheduled for speech

would not know when they were to go to speech. Neither

would they know when to go to music or to P.E.

Q Did you make an investigation as to trips to the library

and, if so, what were the results of those trips, or that

investigation?

A A few trips had been made to the library. There were son

times in which activities had been scheduled for her clas

to come to the library and, of course, on each occasion

that the library had her scheduled to come she carried

her class along, but there were many other instances tha1

the library had not been used, nor the children in her

classroom had not used the library.

MR. McCLURE: I would like to have this introduced

at this time into evidence.

MR. MARSHALL: May I ask a few questions?

MR. GUARISCO: Yes, sir.

BY MR. .MARSHALL:

Q Is this the original of this record, Mr. Tooks?

A Yes, sir.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

Q And these are your notes?

A Yes, sir.

MR. MARSHALL: No objection.

MR. GUARISCO: All right, this will be County Exhibi :

No. 8 in evidence.

County Exhibit No. 8

received in evidence.

BY MR. McCLURE:

Q Mr. Tooks, after you made this plassroom observation did

you go over this critique with Mrs. White at a subsequent

time?

A Yes, sir, immediately after this visitation I had Mrs. WhL

in the office and we went through this and she concurred

in everything that was there and she indicated to me at

that time that she would try to do all she could to corre:

some of these inefficiencies. The lack of things that I

did not find in the classroom, on one or two occasions,

she would come to me and point out one or two things on

here that she had been doing. This was very sporadic,

though, without any consistency at all.

Q Did you make additional observations of the things that

you pointed out to Mrs. White after the conference?

the

A Yes, sir, none of this sort, none to/scope to which this

one complied. A casual observation or a regular observa

tion by a principal should make, and anyone else would mal

a point of going into the classroom from day to day and a

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

IS

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

a result of trying to learn the children, I think after

this visitation I got a pretty good indication of the typ

of things that were going in in the classroom. I might

point out, too, that the form that we had, this was a

form that each teacher had in her hands at least two week|=

prior to the visitation, which would have given each

teacher, I think enough time to prepare herself if she

did not have it already.

Q All right, I direct your attention to on or about

December 11th. Did you have any communication, or what

communication, if any, did you have with .Mrs. White with

regard to her duties as a teacher at Pineview Elementary

School?

A I guess in the course of trying to get adjusted to a

school the first year that a principal does not have time

to talk to teachers each time something comes up that the^

need to be reminded of. I simply followed a pattern that

when teachers reported late for work, rather than having

them to come in and make excuses, or something else that

would be of relative insignificance, to come in and ask

for forgiveness or to be excused, that there is no need

to do this unless there is a consistent pattern and once

I have been able to determine that there has been a con

sistent pattern with somebody, we simply use a letter that

we send out to the teachers, reminding them that they hav»

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

been derelict in this or derelict in that and we wished

that they make note of it and do something about it. This

is the essence of it. On that particular day a letter

was sent to her with regard to not getting her absentee

forms into the office by 9:00 a.m. We had generally

stated that - -

MR. MARSHALL: Mr. Chairman, excuse me. I haven't

objected to anything thus far, but with the pleasure of

the Chairman, Mr. Tooks refers, like he just did, to

"what we do when a person is late". I don’t want to

create any undue impressions about what we are talking

about and, if we can, let him just address himself to

the particular charges made relative to Mrs. White becauss

all of these statements may not be exactly relevant or

do not apply to her.

MR. McCLURE: Mr. Chairman, I think that we will con

nect it up and show where it will apply to Mrs. White.

MR. GUARISCO: Well, I think the point is well taken

so let's stick to the charges and the individual here,

who is the respondent, in these charges- Let's do this

to keep the record straight and also, if we keep going

back and forth, we will be here for two days trying to

get this case tried.

NR. McCLURE: All right, sir, is Mr. Marshall object

ing to this letter? The intent of the letter and the

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

IS

20

21

22

23

24

25

evidence

MR. MARSHALL: No, I'm not talking about the letter,

I'm talking about the response of Mr. Tooks to somebody

being late for work and certain things that might not be

relevant here. I see no connection about somebody being

late here and Mrs. White. I have no objection to the

letter.

MR. GUARISCO: I think the objection is well taken,

so let's stay with the respondent and her activity.

MR. McCLURE: All right, sir, we will certainly do

that.

BY MR. McCLURE:

Q Mr. Tooks did you have an occasion to send Mrs. White a

letter on December 11th?

A Yes, sir, I sent her a letter reminding her that a summar

of her absences had not been coming into the office as I

had requested for it to be.

Q All right, sir, do you have a copy of that letter in your

file?

A Yes, sir.

Q Is this a carbon copy of the letter that was sent to

Mrs. White?

A Yes, sir, this is a copy of the letter that was sent to

Mrs. White.

Q And what date is on that letter?

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

A December 11, 1967.

Q All right, and where has this copy been since you sent it

out?

A In her personnel folder in the school.

Q Has it at any time left the personnel folder?

A No, other than now.

MR. McCLURE: I would like to offer this.

MR. .'MARSHALL: I would like to object to that copy

being offered in evidence because the best evidence is

the original, unless there can be some good showing why

the original is not here.

WITNESS: Well, she has the original.

MR. 'MARSHALL: Also, that this is not a proper - -

the proper foundation has not been laid to introduce the

carbon copy into evidence.

.‘MR. GUARISCO: Mr. Tooks, has this copy been in your

records all this time?

WITNESS: Yes, sir.

MR. GUARISCO: And this is what you wrote in the

normal course of your duties as principal of Pineview

Elementary School?

WITNESS: Yes, sir.

MR. GUARISCO: All right, and where is the original

copy?

WITNESS: The original was mailed to her.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

MR. GUARISCO: All right, I will accept that as

County Exhibit No. 9 in evidence.

County Exhibit No. 9

received in evidenceBY MR. McCLURE:

Q All right, sir, why was it necessary to send Mrs. White

this letter?

A Because she had not done as had been requested of her to

do, to get the summary of absentees into the office,

all right, and you had requested her to do that?

Yes, sir, I had requested all the teachers to do this in

order to do a school-wide count each morning.

Q And what reaction, if any, did (Mrs. White have to this

memorandum?

A None to me personally.

She never responded to that memorandum?

A Other than perhaps to try to see that this was not done

anymore. I never had another occasion to write her a

similar letter.

Q Now, at the end of the '67-*68 school term, did you make

an overall evaluation of Mrs. White's duties as a teacher

at Pineview Elementary School?

A Yes, sir, I did.

Q Is this it here?

A Yes, sir.

•MR. McCLURE: I would like to have this offered for

identification purposes as County Exhibit No. 10.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

Exhibit No. 10.

County Exhibit No. 10

for identification.

Q Would you explain to the Board where this form has been

and the results of your examination in this form?

MR. MARSHALL: Excuse me, but could I see this befoi

he testifies to it?

iMR. McCLURE: Excuse me, yes. (Exhibit supplied.)

MR. MARSHALL: Okay, go ahead.

A This form has been in Mrs. White’s personnel record at

Pineview School and a copy of this has been in the

Superintendent's office in the personnel records there.

Q Would you identify that as to what type form it is?

A This is a form that was developed by a group of Leon

County teachers, principals and administrators to evaluai

the instructural effect of teachers.

Q Does it have a title?

A Yes, it does. The title is “Instructural Effectiveness,

Leon County Evaluation Instrument, Tallahassee, Florida."

Q All right, now is there a name on there as to who the

form was about and who made the evaluation and what year"’

A Yes, sir, the name on here is Alberta White and the

evaluator is James N. Tooks.

Q and is that the form that you made?

A This is the form that I made.

MR. GUARISCO: It will be for identification County

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

A Yes, sir, it is.

Q Would you tell the School Board, in a general summary

way, of how you evaluated Mrs. White during the school

year 1967-68?

A The evaluation scale ranged from below average, 1 to 3;

and average, 4 to 6; superior, 7 to 9. Only in seven

instances did Mrs. White receive a higher evaluation

score than 4.

Q And 4 is what, now?

A Average, low average. The average ranged from 4 to 6.

Over all, on the entire instrument which includes a

professional person, under inter-personal relations,

professional person under organization, she had an averac

of 85% below average on all of the items listed. In man}

instances she received 1 and in some instances she recei\

2.

Q The grade 1 and 2, is that what you're indicating there?

A The grade 1 and 2, receiving the grade 1 for some items

and the grade 2 for other items.

Q And in what category does that fall in?

A Below average.

Q What percentage of below average did she rate?

A On 85% of them.

Q All right, does it show writing in this form?

MR. McCLURE: I would like at this time to introduce

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

that into evidence, if I may.

MR. MARSHALL: Mr. Chairman, I respectfully object to

this being introduced into evidence, No. 1, and No. 2, to

move that all such testimony concerning this record be

stricken. The charges against Mrs. White, specifically

No. 4, relate to competency and it outlines four items.

Certainly this is a complete surprise to her and this is

the first I have heard of it, the first I have seen it,

and it certainly should have been included in No. 4.

Since it is not, it is a complete surprise and certainly

she has not been informed of this and nothing in the recoi

reflects that she has been advised of this and I respect

fully request that it be stricken, or that all testimony

concerning this be stricken.

MR. McCLURE: Mr. Chairman, I think it is pertinent

to show her incompetency, in general, insofar as that is

concerned and this was done by her principal, Mr. Tooks,

and this was done at the direction of the Leon County

school system and I respectfully submit that this is a

proper document for introduction at this time, going to

the general incompetence of - - I believe it touches on

some of the things that were in the specific charges.

MR. GUAR1SCO: I will overrule that objection and

use this to evaluate the overall evidence that you are

going to introduce by testimony from the witness. He sho'

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

N

try to stay within his knowledge of what constitutes in

competency, as set out in charge 4, specifically his

knowledge of what happened and specify those particular

items. I will admit this in evidence as County Exhibit

No. 10.

County Exhibit No. 10

submitted in evidence.

Q Mr. Tooks, in light of the charges that we have preferred

against the respondent here, I direct your attention to

the year 1968-69. I would like for you to give a general

summary of the things that you found to be missing in

Mrs. White’s classroom insofar as her day to day work

with the students and the lesson plans and the activity

plans and the plans that the teacher should have had or

could have had for the students at Pineview Elementary

School.

MR. MARSHALL: Excuse me, but once again, not to

delay matters, but certainly Mr. McClure is being very

skillful and has suggested all sorts of answers in a

compounded question that even I couldn’t follow. Certair

it leaves the field wide open and this man can testify tc

anything he wants to. I would respectfully request of

the Chairman that he not lead- the witness, what should

have been there or what could have been there and was

not there and just let him answer specific questions.

He is the principal and we should limit this to specific

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

questions and answers as to his knowledge.

MR. McCLURE: I will be glad to rephrase that questio

MR. GUARISCO: I will sustain that objection,

Mr. McClure. Ask him specific questions and get specific

answers. Be responsive to the question that he asks and

if we move it in this direction, and a little faster if

we can, I think that we can accomplish what we are here fc

Q Mr. Tooks, I would like for you to tell us the results of

any investigation that you might have made insofar as

lesson plans that Mrs. White had for the school year 1968-

A Would you repeat that question, please?

Q MR. McCLURE: Would you read the question, please?

(QUESTION READ BY REPORTER.)

A I never saw any lesson plans that Mrs. White had for 67-’<

school term or the ,68-,69 school term.

Q All right, did you made an observation of her room and,

if so, what did you find on the atmosphere or the - -

MR. MARSHALL: Once again, just to make the same

objections, the question has been asked and it suggests

the answer and he is looking for a certain answer, and,

once again, I don’t think that is necessary, Mr. Chairman

MR. GUARISCO: I will sustain that objection.

Mr. McClure, you might ask the question as to the particu!.

and

period of time that you want it,/as to the particular tes :

mony that you are seeking.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

MR. McCLURE: All right, sir.

Q I would like to direct your attention to the cleanliness

of Mrs. White's classroom. You have testified before as

to the cleanliness. Did you make any observation as to

that particular item during the year 1968-'69 and, if so,

what were the results of that examination?

A I did not make, if I understand the question, whether or

not I made any examination with regard to the cleanliness

in the room, I observed that the room was disorganized an<

there was a lack of orderliness in the room and I tried t<

do all that I could to see that this particular thing

would not happen.

Q What conferences, if any, did you have on or about

November 12, 1968, with Mrs. White?

A I had a conference with regard to the things in which I

had been dissatisfied with and the things that were - -

the things that the two of us had talked about; that is,

the areas of weaknesses that I felt she possessed and wha';

she should and could do.

Q All right, and what are the areas of weaknesses and what

conferences did you have on those?

A I had a conference with her as a result of the evaluative

instrument and the result of the classroom observation.

In terms of classroom organization and her use of materia..

and resources within the classroom, her interpersonal

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

relationship with the faculty, and her personal appearance

Q All right, who else was there at the conference?

A At this conference a Mrs. Hollis and a Mrs. Manning were

present and I mentioned to Mrs. White at that time that

it would be good for the grade level chairman, Mrs. Hollis

to be present and for the area coordinator, Mrs. Manning,

to be present to offer any suggestions they might have to

work with her and help her in any way possible. She ap

peared to have been quite perturbed and upset over this

after it was all over with and she left the office and

she was very hysterical and upset and she walked into the

teachers' lounge and I heard the noise and I guess every

one else on the school ground heard the noise, too.

Since I represented the threat that had caused this emo

tion, I sent the area coordinator, Mrs. Manning, to tell

her not to go back to the classroom but to come back to

the office and instead she went to the classroom so that

the kids saw her in this condition.

Q All right, where did Mrs. White go, if you know, after

you told her not to go back to the classroom?

A She went back into the classroom and I sent someone down

for her a second time and the person who went returned

with her and I told her that I did not think that she was

in a condition to be with her children and that possibly

it would be best for her to take the rest of the day off

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

and she felt that she was not that bad off, but I felt

that she was.

Q All right, and what directions did you give her, if any?

A I made it very clear to her that after she refused the

first time that I was suggesting very strongly for her to

take the rest of the day off.

Q All right, now I would like to direct you to February of

1969 and ask you if you had a conference with Mrs. White

on her duties as a teacher?

A Yes, sir, this conference with her bordered on the same

area that all the rest of the conferences had bordered on,

We were trying to do the same thing in the same areas.

Q You mean, you had the objections that you had had before

on her organization of the classroom?

A Yes, sir.

Q All right, I would like to direct your attention to on or

about March 25th and ask you what communication, if any,

you sent to Mrs. White?

A Well, I didn’t send it to her, I passed to her across my

desk the statement that I had written. "I am not satisfi?

with your performance as a teacher and suggest that you

look real closely into retirement benefits," and I asked

her whether or not she had any questions.

MR. MARSHALL: May it please the Court, I object to

what was just read being competent because the best evider

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

as to what was being read is the instrument itself and it

has not been offered into evidence and I respectfully re

quest that it be stricken.

MR. McCLURE: All right, I will take that procedure,

Mr. Chairman. I would like to offer this and ask that it

be marked for identification as County Exhibit No. 11.

MR. GUAR1SCO: All right, for identification, No. 11.

County Exhibit No. 11

received for identificat i

Q All right, sir, I hand you this instrument here. Is this

the communication that you read to Mrs. White?

A Yes, sir.

Q Whose handwriting is that in?

A This is in my handwriting.

Q Where has this instrument been since that conference?

A It has been in Mrs. White’s personnel record.

Q And where are those personnel records kept?

A At Pineview School.

MR. MARSHALL: May I just ask one question?

MR. GUARISCO: Certainly.

BY .MR. MARSHALL:

Q Who is the custodian of these records, Mr. Tooks?

A I am,

Q You are the custodian of the records?

A Yes, sir.

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

MR. MARSHALL: No objection.

MR. McCLURE: I would like to introduce that into

evidence at this time.

MR. GUARISCO: This will be County Exhibit No. 11

admitted in evidence.

County Exhibit No. 11