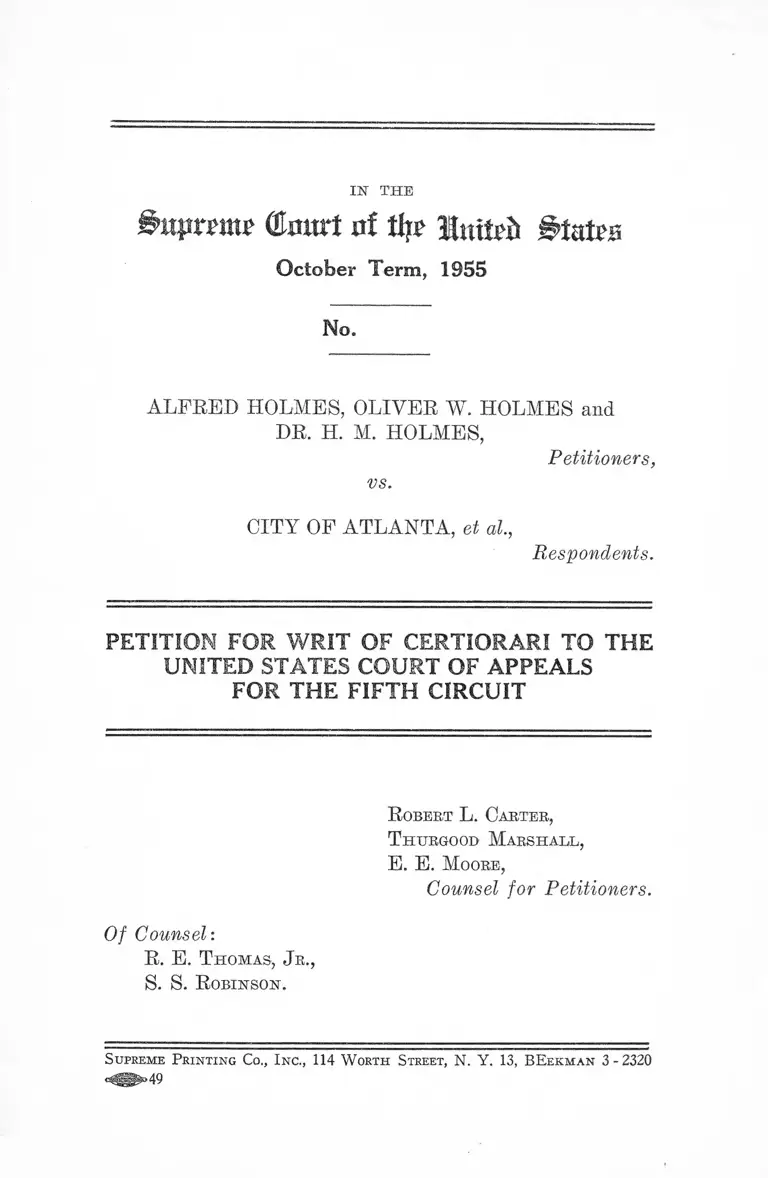

Holmes v. City of Atlanta Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit

Public Court Documents

January 1, 1955

Cite this item

-

Brief Collection, LDF Court Filings. Holmes v. City of Atlanta Petition for Writ of Certiorari to the US Court of Appeals for the Fifth Circuit, 1955. 862b9b55-b89a-ee11-be36-6045bdeb8873. LDF Archives, Thurgood Marshall Institute. https://ldfrecollection.org/archives/archives-search/archives-item/c47bb769-0ced-42fa-a7ae-20076f128696/holmes-v-city-of-atlanta-petition-for-writ-of-certiorari-to-the-us-court-of-appeals-for-the-fifth-circuit. Accessed February 21, 2026.

Copied!

IN T H E

&UJIWUU' ffimtrt of % Hutted Staten

October Term, 1955

No.

ALFRED HOLMES, OLIVER W. HOLMES and

I)R. H. M. HOLMES,

Petitioners,

vs.

CITY OF ATLANTA, et al,

Respondents.

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

R obert L. Carter,

T hitrgood Marshall,

E . E . Moore,

Counsel for Petitioners.

Of Counsel:

R. E . T homas, J r.,

S. S. R obinson.

S upreme P rinting Co., I nc., 114 W orth S treet, N. Y. 13, B E ek m an 3 - 2320

TABLE OF CONTENTS

PAGE

Opinions Below .................................................... 1

Jurisdiction ............................................................... 2

Question Presented .................................................. 2

Statement Of The Case ........................................... 2

Specification Of Errors To Be U rged ....................... 4

Reasons For Allowance Of The W r i t ....................... 5

Conclusion.................................................................. 13

Table of Cases

Blazer v. Black, 196 F. 2d 139 (CA 10th 1952)......... 13

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 U. S. 497 ..................5, 6, 8, 9,10,11

Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483 .. 5, 6, 9,10,11

Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 6 8 ........................... 5, 8

Carter Oil Co. v. McCasland, 190 F. 2d 887 (CA 10th

1951), cert. den. 342 U. S. 8701, rehearing den. 342

U. S. 899 ................................................................. 13

Cohen v. Randall, 137 F. 2d 441 (CA 2d 1943), cert.

den. 320 U. S. 796 ................................................ 13

Cumming v. County Board of Education, 175 U. S.

528 .......................................................................... 6

Dawson v. Mayor, 220 F. 2d 836 (CA 4th 1955)__ 10

Del Balso v. Carozza, 136 F. 2d 280 (C. A. D. C. 1943) 13

Gardner v. Mid-Continent Grain Co., 168 F. 2d 819

(CA 8th 1948) ............ 13

Gong Lum v. Rice, 275 U. S. 7 8 .................................. 6

Hawkins v. Frick-Reid Supply Corp., 154 F. 2d 88

(CA 5th 1946) ........................................................ 13

Henderson v. United States, 339 U. S. 816 ............. 10

11

PAGE,

McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339 U. S.

637 ..................................................................6,7,9,10,11

Missouri ex rel. Gaines v. Canada, 305 U. S. 337 . . . 6

Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537 ............................. 4, 5, 6

Rice v. Arnold, judgment vacated and remanded, 340

U. S. 848, judg. aid’d, 54 So. 2d 114 (1951), cert.

den. 342 U. S. 946 .................................................. 7

Roth v. Fabrikant Bros., Inc., 175 F. 2d 665 (CA 2d

1949) ...................................................................... 13

Sipuel v. Oklahoma, 332 U. S. 631.............................. 6

Sweatt v. Painter, 339 IT. S. 629 .............................. 6, 7

Sweeney v. Louisville, 102 F. Supp. 525 (W. D. Ky.

1951), aff’d sub nom. Muir v. Louisville Park

Theatrical Assn., 202 F. 2d 275 (CA 6th 1953),

judg. vacated and remanded 347 U. S. 971 . . . . . . . 7

Williams v. Kansas City, 205 F. 2d 47 (CA 8th 1952) 9

Statute Cited

Title 28, United States Code, Section 1251(1) ......... 2

Rules Cited

Federal Rules of Civil Procedure:

Rule 8f..................................................................... 11,12

Rule 54c................................................................... 11

IN THE

iatpnw (Hour! rrf tip BtuUs

October Term, 1955

No.

o

A lfred H olmes, Oliver W. H olmes and D r. H. M. H olmes,

vs.

Petitioners.

City of A tlanta, et al.,

Respondents.

--------------------- o----------------------

PETITION FOR WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE

UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS

FOR THE FIFTH CIRCUIT

To the Honorable, the Chief Justice of the

United States and the Associate Justices

of the Supreme Court of the United States:

Petitioners pray that a writ of certiorari issue to review

the judgment of the United States Court of Appeals for the

Fifth Circuit entered in the above-entitled cause on June 17,

1955.

Opinions Below

The opinion, findings of fact and conclusions of law of

the District Court (R. 56-62) are reported at 124 F. Supp.

290. The opinion of the Court of Appeals (R. 69-72) is

reported at 223 F. 2d 93.

2

Jurisdiction

The judgment of the Court of Appeals affirming the

judgment of the lower court was entered on June 17, 1955.

Jurisdiction of this Court is invoked pursuant to Title 28,

United States Code, Section 1251(1).

Question Presented

W h eth er a ju d g m en t w h ich en jo in s th e exc lu sio n o f

N egroes from p u b lic ly ow n ed and op era ted fa c ilit ie s , but

w h ich em p ow ers sta te officia ls to im p ose seg reg a tio n in th e

u se and en jo y m en t o f such fa c ilit ie s , accord s to p etition ers

th e red ress to w h ich th ey are e n titled u n d er th e F ou rteen th

A m en d m en t.

Statement Of The Case

The relevant facts in this case are not in dispute. On

July 19, 1951, petitioners sought to use a public golf course

maintained by the City of Atlanta for the use and enjoy

ment of the general public but were refused permission to

play thereon by the defendants solely because of their race

and color (R. 8). Petitioners sought permission of the Park

Commissioners to use these facilities, but such permission

was refused. This suit followed.

On June 26, 1953, petitioners filed a complaint in the

district court (R. 1-15) seeking a declaratory judgment and,

injunction enjoining respondents “ from making any dis

tinction on account of race or color in providing opportuni

ties, advantages and facilities for playing the game of golf

upon the public golf courses that are now provided, owned,

maintained and operated by the City of Atlanta, or that

may be established and constructed by the City of Atlanta

hereafter, for the benefit and use of the citizens of the City

3

of Atlanta, Georgia.” On August 12, 1953, a motion to

dismiss and a motion for a more definite statement was

filed by respondents (R. 17-25), and was denied on Sep

tember 5, 1953 (R. 25-28). The answer was filed on Sep

tember 15, 1953 (R. 28-31). On July 6, 1954, a hearing was

held in the court below (R. 36-55), and on July 8, 1954, the

district court entered its findings of fact, conclusions of law

and judgment (R. 56-62). The judgment (R. 61-62) was

as follows:

The refusing to allow plaintiffs and others simi

larly situated because they are negroes, to make use,

on a substantially equal basis with white citizens of

municipal facilities for playing golf is to practice a

forbidden discrimination. It is therefore,

Considered, Ordered and Adjudged that the de

fendants, and each of them, their agents, employees

and servants be, and they hereby are restrained and

enjoined from refusing to allow plaintiffs and other

negroes similarly situated, because they are negroes,

to make use, on a substantially equal basis with

white citizens of the municipal facilities for playing

golf. The effect of this judgment will for a reason

able time and until the further order of this Court,

be postponed in order that the defendants may be

afforded a reasonable opportunity to promptly pre

pare and put into effect regulations for the use of

the municipal golf facilities which, while preserving-

segregation, will be in full and fair accord with its

principles. This principle is that the admissibility

of laws separating the races in the enjoyment of

privileges afforded by the State rest wholly upon

the equality of the privileges which the laws give

to the separated groups within the State. In apply

ing this principle, that equality of treatment of white

and colored citizens must be afforded which will

secure to both, complete and full recognition, that,

4

under the Constitution and laws, there are not two

classes of citizens, a first and second, but one class,

with all of equal rank in respect of their rights and

privileges to use and enjoy facilities provided at

public expense for public use.

On August 6, 1954, petitioners filed notice of appeal and

urged in their brief and argument in the Court of Appeals

that the judgment below was in error in permitting the state

to admit Negroes to the golf course but operate such facili

ties on a segregated basis. It was urged that all racial

differentiations in the use and enjoyment of these facilities

were barred by the Fourteenth Amendment. The Court

of Appeals affirmed the judgment on the apparent ground

that the judgment entered was consistent with the relief

asked for in the complaint, and that the errors urged were

at variance with the judgment entered. That judgment is

here for review.

Specification Of Errors To Be Urged

T h e Court o f A p p e a ls e r r e d :

1. In holding that this case was properly decided on the

grounds that the district court had granted the petitioners

all the relief which they requested.

2. In sustaining the judgment of the court below in which

the Fourteenth Amendment is construed as permitting the

enforcement of regulations requiring racial distinctions in

the use and enjoyment of golf facilities owned and oper

ated by the City of Atlanta.

3. In sustaining the judgment of a district court which

applies the “ separate but equal” doctrine of Plessy v. Fer

guson to the instant case.

5

Reasons For Allowance Of The Writ

1. The decision of the Court of Appeals is in apparent

conflict with the decisions of this Court in the School Segre

gation Cases (Brown v. Board of Education, 347 U. S. 483;

Bolling v. Sharpe, 347 IT. S. 497) with respect to the scope

and reach of the Fourteenth Amendment. Under the in

stant decision, the Court of Appeals condones regulations

which require racial segregation in the use and enjoyment

of the public parks of the City of Atlanta. The necessary

premise upon which this decision rests is that the “ sepa

rate but equal” doctrine is an appropriate constitutional

yardstick in the field of public recreation, and that repudia

tion of that doctrine in the School Segregation Cases ap

plies only to the field of public education.

It is true, of course, that prior to decision by this Court

in the School Segregation Cases that lower federal courts

and state courts had regarded the “ separate but equal”

doctrine as the basic test to determine the constitutionality

of state imposed racial segregation in almost all areas of

state activity. The decisions of this Court, however, do not

support such all-inclusive application of “ separate but

equal”. The doctrine was approved by this Court in Plessy

v. Ferguson, 163 U. S. 537—a case involving transportation.

It was rejected in Buchanan v. Warley, 245 U. S. 68, as

inappropriate to the field of housing. It was repudiated

in the field of public education in the School Segregation

Cases. Indeed, a reading of that opinion indicates that this

Court, on reexamination of its own decisions in the field of

education, does not regard any of those decisions as con

stituting adoption or approval by this Court of the “ sepa

rate but equal” doctrine. In Brown v. Board of Education,

supra, the Court said at page 491:

In the first cases in this Court construing the

Fourteenth Amendment, decided shortly after its

adoption, the Court interpreted it as proscribing all

6

state-imposed discriminations against the Negro

race. The doctrine of “ separate but equal” did not

make its appearance in this Court until 1896 in the

case of Plessy v. Ferguson, supra, involving not

education but transportation. American courts have

since labored with the doctrine for over half a cen

tury. In this Court, there have been six cases in

volving the “ separate but equal” doctrine in the

field of public education. In Cumming v. County

Board of Education, 175 IT. S. 528 . . . and Gong

Lum v. Rice, 275 U. S. 78 . . . the validity of the

doctrine itself was not challenged. In more recent

cases, all on the graduate school level, inequality was

found in that specific benefits enjoyed by white stu

dents were denied to Negro students of the same

educational qualifications. Missouri ex rel. Gaines

v. Canada, 305 U. 8. 337 . . . ; Sipuel v. Oklahoma,

332 U. S. 631 . . . ; Sweatt v. Painter, 339 U. S. 629

. . . ; McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339

IT. S. 637 . . . . In none of these cases was it neces

sary to reexamine the doctrine to grant relief to the

Negro plaintiff. And in Sweatt v. Painter . . . the

Court expressly reserved decision on the question

whether Plessy v. Ferguson should be held inappli

cable to public education.

Thus, with the repudiation of the “ separate but equal” doc

trine in the field of public education in the School Segrega

tion Cases, there are no decisions of the Supreme Court

other than those involving transportation in which the doc

trine has been applied by this Court.

Moreover, the doctrine has never been approved by this

Court in the field of public recreation. There are only two

relevant decisions involving public recreation decided by

this Court and both of those decisions are indications that

this Court regards its decisions in public education with

7

respect to “ equal protection of the laws” and “ due process

of law” as applicable in the field of public recreation.

Rice v. Arnold, judg. vacated and remanded, 340 U. S.

848, judg. aff’d, 54 So. 2d 114 (1951), cert, denied, 342 U. S.

946, raised the question of the right of Negroes to use city

owned and operated golf links in Miami, Fla., without

being subjected to segregation. This Court, granted cer

tiorari, vacated the judgment below and remanded the cause

for reconsideration in the light of Sweatt v. Painter, 339

U. S. 629, and McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, 339

U. S. 637. On remand, the Florida Supreme Court re

affirmed its prior judgment and stated that in any event

petitioner had misconceived his remedy; that if he sought

to challenge the reasonableness of the court’s judgment,

the proper procedure would have been for him to file a

bill for declaratory judgment. It was on this state pro

cedural ground that this Court based its refusal to grant

the petition for writ of certiorari when the case again

reached the Supreme Court. Justices Black and Douglas

were of the opinion that the petition should be granted.

Sweeney v. Louisville, 102 F. Supp. 525 (W. D. Ky.

1951), aff’d sub nom. Muir v. Louisville Park Theatrical

Assn., 202 F. 2d 275 (CA 6th 1953), judg. vacated and re

manded, 347 U. S. 971. In the Muir case, a private

theatrical organization holding outdoor theatrical shows in

a public amphitheater in Louisville, Kentucky was held

both by the district court and the Court of Appeals to be

outside the reach of the Fourteenth Amendment when ques

tion was raised concerning its practice of racial discrimina

tion. This Court granted the petition for writ of certiorari,

vacated the judgment and remanded the cause for “ con

sideration in the light of the Segregation Cases . . . and

conditions that now prevail.”

8

These two cases clearly demonstrate that this Court

regards its decisions in the field of public education as

applicable to the field of public recreation.

Indeed, whatever the present status of the “ separate

but equal” doctrine, it seems blear that public recreation

is far closer to public education than it is to intrastate

transportation. Thus, logic would dictate that decisions

in public education govern dispositions of similar questions

in public recreation. Moreover, in Bolling v. Sharpe, supra,

this Court made clear the fact that racial classifications

would be scrutinized and tested with “ particular care” ,

and would not be sustained unless “ reasonably related to

a proper governmental objective.” There it said at page

499:

Classifications based solely upon race must be

scrutinized with particular care, since they are con

trary to our traditions and hence constitutionally

suspect. As long ago as 1896, this Court declared

the principle “ that the Constitution of the United

States, in its present form, forbids, so far as civil

and political rights are concerned, discrimination by

the General Government, or by the States, against

any citizen because of his race.” And in Buchanan

v. Warley, 245 U. S. . . . the Court held that a

statute which limited the right of a property owner

to 'convey his property to a person of another race

was, an unreasonable discrimination, a denial of

due process of law.

Although the Court has not assumed to define

“ liberty” with any great precision, that term is not

confined to mere freedom from bodily restraint.

Liberty under law extends to the full range of con

duct which the individual is free to pursue, and it

cannot be restricted except for a proper govern

mental objective . . .

9

Under this test it is manifest that regulations by the

City of Atlanta in the use and enjoyment of public golf

courses based upon race and color cannot be justified. For

if segregation is unreasonable as to public schools where

attendance is compulsory, certainly it is unreasonable as

to golf bourses, the use of which is entirely voluntary. The

doctrine of the School Segregation Cases, we submit, is

applicable here, and it was error for the court below not to

apply that doctrine in disposing of this case.

Further, the court below affirms the judgment of the

district court on the grounds that the petitioners obtained

all the relief they asked for. That this is a misreading of

petitioners’ pleadings, we point out infra, but more im

portantly, the issue here must be whether the state has the

power to subject the use of its parks to regulations which

require racial segregation in their use and enjoyment.

Under the decisions of this Court, we submit, it has no such

power. Since the decision of the Court of Appeals is at

variance with those decisions, it cannot be sustained. For

this reason, we submit, this petition for a writ of certiorari

should be granted.

2. There is conflict among the Courts of Appeals on

this question, and that conflict should be resolved by this

Court.

In Williams v. Kansas City, 205 F. 2d 47 (CA 8th 1952),

the Court of Appeals affirmed the judgment of the district

court which had struck down racial segregation in the use

of a city owned and operated swimming pool as violative

of the Fourteenth Amendment. The Court of Appeals

relied upon McLaurin v. Oklahoma State Regents, supra,

as the basis for its affirmation of the lower court’s judg

ment. While the court did not hold that the ‘ ‘ separate but

equal” doctrine was no longer of validity, it felt bound to

follow the same approach which this Court had followed in

1 0

the McLaurin case. This Court denied a petition for writ

of certiorari, 346 U. S. 826.

In Dawson v. Mayor, 220 F. 2d 386 (CA 4th 1955), the

Court of Appeals struck down segregation in public parks

and bathhouses owned and operated by the City of Balti

more and the State of Maryland as violative of the Four

teenth Amendment. The court there relied upon the

McLaurin case, supra; Brown v. Board of Education, supra;

Bolling v. Sharpe, supra, and Henderson v. United States,

339 IT. S. 816, as setting forth the applicable law which

should be applied in that case. There it said that it is

obvious “ that segregation cannot be justified as a means

to preserve the public peace merely because the tangible

facilities furnished to one race are equal to those furnished

to the other. ’ ’ There the court felt bound to apply to public

recreation the same rationale which this Court had used

in approaching the question of segregation in graduate

schools and dining cars and public elementary and sec

ondary schools. That case is now pending in this Court on

appeal.

Here a contrary position is taken. The Court of Ap

peals has sustained the authority of the state to impose

racial distinctions in the use of its public parks and has

held, by necessary implication that the “ separate but equal”

doctrine is a valid constitutional yardstick with respect to

the use and enjoyment of public recreational facilities.

The Fourth and Eighth Circuits are clearly of the view

that the “ separate but equal” doctrine had been weakened

or repudiated by more recent decisions of this Court and

have refused to apply that doctrine in the field of public

recreation. In fact, the Fourth Circuit is clearly of the

opinion, as stated supra, that the “ separate but equal” doc

trine is of no validity and cannot be applied with respect

to the regulation of public recreational facilities. On the

other hand, the Fifth Circuit, as evidenced by the opinion

in the instant case, necessarily takes the view that the

1 1

“ separate but equal” doctrine still has validity and can be

applied in the field of public recreation.

We submit that the rationale of this Court’s decisions

in the field of public education—McLaurin v. Oklahoma

State Regents, supra; Brown v. Board of Education, supra,

and Bolling v. Sharpe, supra,—are guides to decisions in

any area where question is raised concerning the constitu

tionality of state racial restrictions and distinctions. We

submit that the approach to decisions by the Fourth and

Eighth Circuits, on one hand, and by the Fifth Circuit, on

the other, cannot be reconciled. It is important and neces

sary in the public interest that this Court make clear

which approach is proper. It is respectfully submitted,

therefore, that this petition be granted to resolve this con

flict and clarify the question which these three cases raise.

3. The decision of the Court of Appeals in the instant

case is contrary to Eule 8f. and 54c. of the Federal Eules

of Civil Procedure.

Eule 8f. provides as follows:

All pleadings shall be so construed as to do sub

stantial justice.

Eule 54c. provides:

A judgment by default shall not be different in

kind from or exceed in amount that prayed for in

the demand for judgment. Except as to a party

against whom a judgment is entered by default, every

final judgment shall grant the relief to which the

party in whose favor it is rendered is entitled, even

if the party has not demanded such relief in his

pleadings.

The decision of the Court of Appeals is a narrow and

technical reading of the pleadings in this case. Indeed, it

is a misreading of the complaint because nowhere do peti

1 2

tioners request a judgment which would permit their use

of the golf facilities in Atlanta to he subject to rules and

regulations requiring racial segregation. In their com

plaint, petitioners prayed (see R. 14, par. 6) for an injunc

tion restraining and enjoining the respondents “ from

making any distinction on account of race or color in

providing opportunities, advantages and facilities for play

ing the game of golf upon the public golf courses that are

now provided, owned, maintained and operated by the City

of Atlanta. . . . ” This, we submit, is unquestionably a prayer

for relief which encompasses a judgment barring racial

segregation. Rule 8f. of the Federal Rules of Civil Pro

cedure, we submit, required the court to so read these

pleadings, providing they were entitled to relief which

barred imposition of any racial distinctons whatever.

When the instant action was begun, petitioners and all

other Negroes were completely excluded from public golf

courses in Atlanta. In their complaint, petitioners sought

the right to use the golf courses on the same basis as all

other citizens. The pleadings here are not, as the Court

of Appeals seeks to imply, subject to the construction that

petitioners are merely asking to use the golf courses sub

ject to racial segregation pursuant to the “ separate but

equal” doctrine. Rather, the complaint seeks to have the

state officials enjoined from making any distinctions what

soever in the use and enjoyment of the golf course. More

over, if the state is empowered to impose segregation in

the use of the golf courses, the fact that petitioners prayed

that it not be imposed would be of little moment insofar

as their entitlement to relief is concerned. On the other

hand, if the state is not empowered to impose segregation in

the use of these facilities (as we contend), then a decision

which requires that the public golf facilities in question

be opened to Negroes would necessarily require that these

facilities be made available, subject only to the same

rules and regulations applicable to all other persons.

1 3

We submit, therefore, that the court below was required

to grant to petitioners all the relief to which they were

entitled irrespective of whether such relief was prayed for

in the pleadings. This has been the construction of Rule

54c. Blazer v. Black, 196 F. 2d 139 (CA 10th 1952); Carter

Oil Co. v. McCasland, 190 F. 2d 887 (CA 10th 1951), cert

denied 342 U. S. 870, rehearing- denied 342 U. S. 899;

Gardner v. Mid-Continent Grain Co., 168 F. 2d 819 (CA

8th 1948); Roth v. Fahrikant Bros., Inc., 175 F. 2d 665 (CA

2d 1949); Cohen v. Randall, 137 F. 2d 441 (CA 2d 1943),

cert, denied 320 U. 8. 796; Del Balso v. Carosza, 136 F. 2d

280 (C. A. D. C. 1943); Hawkins v. Frick-Reid Supply

Corp., 154 F. 2d 88 (CA 5th 1946).

The decision here is at variance with both these univer

sally accepted and well-recognized rules of federal practice

and this Court should grant this petition for writ of

certiorari to bring this decision in line with applicable rules

governing the conduct of federal courts.

Conclusion

W herefore, for the reasons hereinabove stated, this

petition for writ of certiorari should be granted, and the

judgment of the court below should be reversed and re

manded without argument based on the decision of this

Court in the School Segregation Cases.

Respectfully submitted,

Of Counsel:

R. E, T homas, J r.,

S. S. R obinson.

R obert L. Carter,

T htjrgood Marshall,

E. E. Moore,

Counsel for Petitioners.